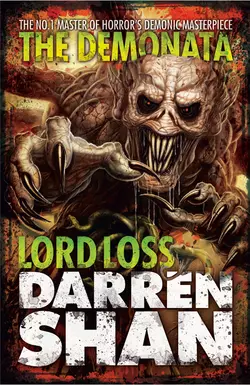

Lord Loss

Lord Loss

Darren Shan

The first book in the Demonata, the demonic symphony in ten parts by multi-million-copy bestselling horror writer Darren Shan…When Grubbs Grady first encounters Lord Loss and his evil minions, he learns three things:• the world is vicious,• magic is possible,• demons are real.He thinks that he will never again witness such a terrible night of death and darkness.…He is wrong.

Lord it up with Darren Shan in the shadows of the web at

www.darrenshan.com

For:

Bas — my demon lover

OBEs (Order of the Bloody Entrails) to:

Caroline “pie chart” Paul

D.O.M.I.N.I.C. Kingston

Nicola “schumacher” Blacoe

Editorial Evilness:

Stellasaurus Paskins

Agents of Chaos:

the Christopher Little crew

LORD LOSS

Lord Loss sows all the sorrows of the world

Lord Loss seeds the grief-starched trees

In the centre of the web, lowly Lord Loss bows his head

Mangled hands, naked eyes

Fanged snakes his soul line

Curled inside like textured sin

Bloody, curdled sheets for skin

In the centre of the web, vile Lord Loss torments the dead

Over strands of red, Lord Loss crawls

Dispensing pain, despising all

Shuns friends, nurtures foes

Ravages hope, breeds woe

Drinks moons, devours suns

Twirls his thumbs till the reaper comes

In the centre of the web, lush Lord Loss is all that’s left

Contents

Rat Guts

Demons

Dervish

The Grand Tour

Portraits

Spleen

Carnage in the Forest

A Theory

The Cellar

The Longest Day

Arooooo!

Family Ties

The Curse

The Challenge

The Choice

The Summoning

The Battle

A Change of Plan

Spiral to the Heart of Nowhere

The Change

Other Books by Darren Shan

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

RAT GUTS

→ Double history on a Wednesday afternoon — total nightmare! A few minutes ago, I would have said I couldn’t imagine anything worse. But when there’s a knock at the door, and it opens, and I spot my mum outside, I realise — life can always get worse.

When a parent turns up at school, unexpected, it means one of two things. Either somebody close to you has been seriously injured or died, or you’re in trouble.

My immediate reaction — please don’t let anybody be dead! I think of Dad, Gret, uncles, aunts, cousins. It could be any of them. Alive and kicking this morning. Now stiff and cold, tongue sticking out, a slab of dead meat just waiting to be buried. I remember Gran’s funeral. The open coffin. Her shining flesh, having to kiss her forehead, the pain, the tears. Please don’t let anyone be dead! Please! Please! Please! Ple–

Then I see Mum’s face, white with rage, and I know she’s here to punish, not comfort.

I groan, roll my eyes and mutter under my breath, “Bring on the corpses!”

→ The head’s office. Me, Mum and Mr Donnellan. Mum’s ranting and raving about cigarettes. I’ve been seen smoking behind the bike shed (the oldest cliché in the book!). She wants to know if the head’s aware of this, of what the pupils in his school are getting up to.

I feel a bit sorry for Mr Donnellan. He has to sit there, looking like a schoolboy himself, shuffling his feet and saying he didn’t know this was going on and he’ll launch an investigation and put a quick end to it. Liar! Of course he knew. Every school has a smoking area. That’s life. Teachers don’t approve, but they turn a blind eye most of the time. Certain kids smoke — fact. Safer to have them smoking at school than sneaking off the grounds during breaks and at lunch.

Mum knows that too. She must! She was young once, like she’s always reminding me. Kids were no different in Mum’s time. If she stopped for a minute and thought back, she’d see what a bloody embarrassment she’s being. I wouldn’t mind her having a go at me at home, but you don’t march into school and start laying down the law in the headmaster’s office. She’s out of order — big time.

But it’s not like I can tell her, is it? I can’t pipe up with, “Oi! Mother! You’re disgracing us both, so shut yer trap!”

I smirk at the thought, and of course that’s when Mum pauses for the briefest of moments and catches me. “What are you grinning at?” she roars, and then she’s off again — I’m smoking myself into an early grave, the school’s responsible, what sort of a freak show is Mr Donnellan running, la-di-la-di-la-di-bloody-la!

BAWring!

→ Her rant at school’s nothing compared to the one I get at home. Screaming at the top of her lungs, blue bloody murder. She’s going to send me off to boarding school — no, military school! See how I like that, having to get up at dawn each morning and do a hundred press-ups before breakfast. How does that sound?

“Is breakfast a fry-up or some cereally, yoghurty crap?” is my response, and I know the second it’s out of my mouth that it’s the wrong thing to say. This isn’t the time for the famed Grubbs Grady brand of cutting-edge humour.

Cue the enraged Mum fireworks. Who do I think I am? Do I know how much they spend on me? What if I get kicked out of school? Then the clincher, the one mums all over the world love pulling out of the hat — “Just wait till your father gets home!”

→ Dad’s not as freaked out as Mum, but he’s not happy. He tells me how disappointed he is. They’ve warned me so many times about the dangers of smoking, how it destroys people’s lungs and gives them cancer.

“Smoking’s dumb,” he says. We’re in the kitchen (I haven’t been out of it since Mum dragged me home from school early, except to go to the toilet). “It’s disgusting, antisocial and lethal. Why do it, Grubbs? I thought you had more sense.”

I shrug wordlessly. What’s there to say? They’re being unfair. Of course smoking’s dumb. Of course it gives you cancer. Of course I shouldn’t be doing it. But my friends smoke. It’s cool. You get to hang out with cool people at lunch and talk about cool things. But only if you smoke. You can’t be in if you’re out. And they know that. Yet here they stand, acting all Gestapo, asking me to account for my actions.

“How long has he been smoking? That’s what I want to know!” Mum’s started referring to me in the third person since Dad arrived. I’m beneath direct mention.

“Yes,” Dad says. “How long, Grubbs?”

“I dunno.”

“Weeks? Months? Longer?”

“A few months maybe. But only a couple a day.”

“If he says a couple, he means at least five or six,” Mum snorts.

“No, I don’t!” I shout. “I mean a couple!”

“Don’t raise your voice to me!” Mum roars back.

“Easy,” Dad begins, but Mum goes on as if he isn’t there.

“Do you think it’s clever? Filling your lungs with rubbish, killing yourself? We didn’t bring you up to watch you give yourself cancer! We don’t need this, certainly not at this time, not when–”

“Enough!” Dad shouts, and we both jump. Dad almost never shouts. He usually gets very quiet when he’s angry. Now his face is red and he’s glaring — but at both of us, not just me.

Mum coughs, as if she’s embarrassed. She sits, brushes her hair back off her face and looks at me with wounded eyes. I hate when she pulls a face like this. It’s impossible to look at her straight or argue.

“I want you to stop, Grubbs,” Dad says, back in control now. “We’re not going to punish you–” Mum starts to object, but Dad silences her with a curt wave of his hand “–but I want your word that you’ll stop. I know it won’t be easy. I know your friends will give you a hard time. But this is important. Some things matter more than looking cool. Will you promise, Grubbs?” He pauses. “Of course, that’s if you’re able to quit…”

“Of course I’m able,” I mutter. “I’m not addicted or anything.”

“Then will you? For your sake — not ours?”

I shrug, trying to act like it’s no big thing, like I was planning to stop anyway. “Sure, if you’re going to make that much of a fuss about it,” I yawn.

Dad smiles. Mum smiles. I smile.

Then Gret walks in the back door and she’s smiling too — but it’s an evil, big-sister-superior smile. “Have we sorted all our little problems out yet?” she asks, voice high and fake-innocent.

And I know instantly — Gret grassed me up to Mum! She found out I was smoking and she told. The cow!

As she swishes past, beaming like an angel, I burn fiery holes in the back of her head with my eyes, and a single word echoes through my head like the sound of ungodly thunder…

Revenge!

→ I love rubbish dumps. You can find all sorts of disgusting stuff there. The perfect place to go browsing if you want to get even with your annoying traitor of a sister.

I climb over mounds of garbage and root through black bags and soggy cardboard boxes. I’m not sure exactly what I’m going to use, or in what fashion, so I wait for inspiration to strike. Then, in a small plastic bag, I find six dead rats, necks broken, just starting to rot. Excellent!

Look out, Gret — here I come!

→ Eating breakfast at the kitchen table. Radio turned down low. Listening to the noises upstairs. Trying not to giggle. Waiting for the outburst.

Gret’s in her shower. She showers at least twice a day, before she goes to school and when she gets back. Sometimes she has one before going to bed too. I don’t know why anybody would bother to keep themselves so clean. I reckon it’s a form of madness.

Because she’s so obsessed with showering, Mum and Dad gave her the en suite bedroom. They figured I wouldn’t mind. And I don’t. In fact, it’s perfect. I wouldn’t have been able to pull my trick if Gret didn’t have her own shower, with its very own towel rack.

The shower goes off. Splatters, then drips, then silence. I tense with excitement. I know Gret’s routines inside out. She always pulls her towel down off its rack after she’s showered, not before. I can’t hear her footsteps, but I imagine her taking the three or four steps to the towel rack. Reaching up. Pulling it down. Aaaaaaaaannnddd…

On cue — screams galore. A shocked single scream to start. Then a volley of them, one running into another. I push my bowl of soggy cornflakes aside and prepare myself for the biggest laugh of the year.

Mum and Dad are by the sink, discussing the day ahead. They go stiff when they hear the screams, then dash towards the stairs, which I can see from where I’m sitting.

Gret appears before they reach the stairs. Crashes out of her room, screaming, slapping bloody shreds from her arms, tearing them from her hair. She’s covered in red. Towel clutched with one hand over her front — even terrified out of her wits, there’s no way she’s going to come down naked!

“What’s wrong?” Mum shouts. “What’s happening?”

“Blood!” Gret screams. “I’m covered in blood! I pulled the towel down! I…”

She stops. She’s spotted me laughing. I’m doubled over. It’s the funniest thing I’ve ever seen.

Mum turns and looks at me. Dad does too. They’re speechless.

Gret picks a sticky pink chunk out of her hair, slowly this time, and studies it. “What did you put on my towel?” she asks quietly.

“Rat guts!” I howl, pounding the table, crying with laughter. “I got… rats at the rubbish dump… chopped them up… and…” I almost get sick, I’m laughing so much.

Mum stares at me. Dad stares at me. Gret stares at me.

Then —

“You lousy son of a–!”

I don’t catch the rest of the insult — Gret flies down the stairs ahead of it. She drops her towel on the way. I don’t have time to react to that before she’s on me, slapping and scratching at my face.

“What’s wrong, Gretelda?” I giggle, fending her off, calling her by the name she hates. She normally calls me Grubitsch in response, but she’s too mad to think of it now.

“Scum!” she shrieks. Then she lunges at me sharply, grabs my jaw, jerks my mouth open and tries her hardest to stuff a handful of rat guts down my throat.

I stop laughing instantly — a mouthful of rotten rat guts wasn’t part of the grand uber-joke! “Get off!” I roar, lashing out wildly. Mum and Dad suddenly recover and shout at exactly the same time.

“Stop that!”

“Don’t hit your sister!”

“She’s a lunatic!” I gasp, pushing myself away from the steaming Gret, falling off my chair.

“He’s an animal!” Gret sobs, picking more chunks of guts from her hair, wiping rat blood from her face. I realise she’s crying — serious waterworks — and her face is as red as her long, straight hair. Not red from the blood — red from anger, shame and…fear?

Mum picks up the dropped towel, takes it to Gret, wraps it around her. Dad’s just behind them, face as dark as death. Gret picks more strands and loops of rat guts from her hair, then howls with anguish.

“They’re all over me!” she yells, then throws some of the guts at me. “You bloody little monster!”

“You’re the one who’s bloody!” I cackle. Gret dives for my throat.

“No more!” Dad doesn’t raise his voice but his tone stops us dead.

Mum’s staring at me with open disgust. Dad’s shooting daggers. I sense that I’m the only one who sees the funny side of this.

“It was just a joke,” I mutter defensively before the accusations fly.

“I hate you!” Gret hisses, then bursts into fresh tears and flees dramatically.

“Cal,” Mum says to Dad, freezing me with an ice-cold glare. “Take Grubitsch in hand. I’m going up to try and comfort Gretelda.” Mum always calls us by our given names. She’s the one who picked them, and is the only person in the world who doesn’t see how shudderingly awful they are.

Mum heads upstairs. Dad sighs, walks to the counter, tears off several sheets of kitchen paper and mops up some of the guts and streaks of blood from the floor. After a couple of silent minutes of this, as I lie uncertainly by my upturned chair, he turns his steely gaze on me. Lots of sharp lines around his mouth and eyes — the sign that he’s really angry, even angrier than he was about me smoking.

“You shouldn’t have done that,” he says.

“It was funny,” I mutter.

“No,” he barks. “It wasn’t.”

“She deserved it!” I cry. “She’s done worse to me! She told Mum about me smoking — I know it was her! And remember the time she melted my lead soldiers? And cut up my comics? And–”

“There are some things you should never do,” Dad interrupts softly. “This was wrong. You invaded your sister’s privacy, humiliated her, terrified her senseless. And the timing! You…” He pauses and ends with a fairly weak “…upset her greatly.” He checks his watch. “Get ready for school. We’ll discuss your punishment later.”

I trudge upstairs miserably, unable to see what all the aggro is about. It was a great joke. I laughed for hours when I thought of it. And all that hard work — chopping the rats up, mixing in some water to keep them fresh and make them gooey, getting up early, sneaking into her bathroom while she was asleep, carefully putting the guts in place — wasted!

I pass Gret’s bedroom and hear her crying pitifully. Mum’s whispering softly to her. My stomach gets hard, the way it does when I know I’ve done something bad. I ignore it. “I don’t care what they say,” I grumble, kicking open the door to my room and tearing off my pyjamas. “It was a brilliant joke!”

→ Purgatory. Confined to my room after school for a month. A whole bloody MONTH! No TV, no computer, no comics, no books — except schoolbooks. Dad leaves my chess set in the room too — no fear my chess-mad parents would take that away from me! Chess is almost a religion in this house. Gret and I were reared on it. While other toddlers were being taught how to put jigsaws together, we were busy learning the ridiculous rules of chess.

I can come downstairs for meals, and bathroom visits are allowed, but otherwise I’m a prisoner. I can’t even go out at the weekends.

In solitude, I call Gret every name under the moon the first night. Mum and Dad bear the brunt of my curses the next. After that I’m too miserable to blame anyone, so I sulk in moody silence and play chess against myself to pass the time.

They don’t talk to me at meals. The three of them act like I’m not not there. Gret doesn’t even glance at me spitefully and sneer, the way she usually does when I’m getting the doghouse treatment.

But what have I done that’s so bad? OK, it was a crude joke and I knew I’d get into trouble — but their reactions are waaaaaaay over the top. If I’d done something to embarrass Gret in public, fair enough, I’d take what was coming. But this was a private joke, just between us. They shouldn’t be making such a song and dance about it.

Dad’s words echo back to me — “And the timing!” I think about them a lot. And Mum’s, when she was having a go at me about smoking, just before Dad cut her short — “We don’t need this, certainly not at this time, not when–”

What did they mean? What were they talking about? What does the timing have to do with anything?

Something stinks here — and it’s not just rat guts.

→ I spend a lot of time writing. Diary entries, stories, poems. I try drawing a comic – ‘Grubbs Grady, Superhero!’ – but I’m no good at art. I get great marks in my other subjects — way better than goat-faced Gret ever gets, as I often remind her — but I’ve all the artistic talent of a duck.

I play lots of games of chess. Mum and Dad are chess fanatics. There’s a board in every room and they play several games most nights, against each other or friends from their chess clubs. They make Gret and me play too. My earliest memory is of sucking on a white rook while Dad explained how a knight moves.

I can beat just about anyone my age – I’ve won regional competitions — but I’m not in the same class as Mum, Dad or Gret. Gret’s won at national level and can wipe the floor with me nine times out of ten. I’ve only ever beaten Mum twice in my life. Dad — never.

It’s been the biggest argument starter all my life. Mum and Dad don’t put pressure on me to do well in school or at other games, but they press me all the time at chess. They make me read chess books and watch videotaped tournaments. We have long debates over meals and in Dad’s study about legendary games and grandmasters, and how I can improve. They send me to tutors and keep entering me in competitions. I’ve argued with them about it – I’d rather spend my time watching and playing football — but they’ve always stood firm.

White rook takes black pawn, threatens black queen. Black queen moves to safety. I chase her with my bishop. Black queen moves again — still in danger. This is childish stuff – I could have cut off the threat five moves back, when it became apparent — but I don’t care. In a petty way, this is me striking back. “You take my TV and computer away? Stick me up here on my own? OK — I’m gonna learn to play the worst game of chess in the world. See how you like that, Corporal Dad and Commandant Mum!”

Not exactly Luke Skywalker striking back against the evil Empire by blowing up a Death Star, I know, but hey, we’ve all gotta start somewhere!

→ Studying my hair in the mirror. Stiff, tight, ginger. Dad used to be ginger when he was younger, before the grey set in. Says he was fifteen or sixteen when he noticed the change. So, if I follow in his footsteps, I’ve only got a handful or so years of unbroken ginger to look forward to.

I like the idea of a few grey hairs, not a whole head of them like Dad, just a few. And spread out — I don’t want a skunk patch! I’m big for my age — taller than most of my friends — and burly. I don’t look old, but if I had a few grey hairs, I might be able to pass for an adult in poor light — bluff my way into 18-rated movies!

The door opens. Gret — smiling shyly. I’m nineteen days into my sentence. Full of hate for Gretelda Grotesque. She’s the last person I want to see.

“Get out!”

“I came to make up,” she says.

“Too late,” I snarl nastily. “I’ve only got eleven days to go. I’d rather see them out than kiss your…” I stop. She’s holding out a plastic bag. Something white inside. “What’s that?” I ask suspiciously.

“A present to make up for getting you grounded,” she says, and lays it on my bed. She glances out of the window. The curtains are open. A three-quarters moon lights up the sill. There are some chess pieces on it, from when I was playing earlier. Gret shivers, then turns away.

“Mum and Dad said you can come out — the punishment’s over. They’ve ended it early.”

She leaves.

Bewildered, I tear open the plastic. Inside — a Tottenham Hotspur shirt, shorts and socks. I’m stunned. The Super Spurs are my team, my football champions. Mum used to buy me their latest kit at the start of every season, until I hit puberty and sprouted. She won’t buy me any new kits until I stop growing — I out-grew the last one in just a month.

This must have cost Gret a fortune — it’s the brand new kit, not last season’s. This is the first time she’s ever given me a present, except at Christmas and birthdays. And Mum and Dad have never cut short a grounding before — they’re very strict about making us stick to any punishment they set.

What the hell is going on?

→ Three days after my early release. To say things are strange is the understatement of the decade. The atmosphere’s just like it was when Gran died. Mum and Dad wander around like robots, not saying much. Gret mopes in her room or in the kitchen, stuffing herself with sweets and playing chess nonstop. She’s like an addict. It’s bizarre.

I want to ask them about it, but how? “Mum, Dad — have aliens taken over your bodies? Is somebody dead and you’re too afraid to tell me? Have you all converted to Miseryism?”

Seriously, jokes aside, I’m frightened. They’re sharing a secret, something bad, and keeping me out of it. Why? Is it to do with me? Do they know something that I don’t? Like maybe… maybe…

(Go on — have the guts! Say it!)

Like maybe I’m going to die?

Stupid? An overreaction? Reading too much into it? Perhaps. But they cut short my punishment. Gret gave me a present. They look like they’re about to burst into tears at any given minute.

Grubbs Grady — on his way out? A deadly disease I caught on holiday? A brain defect I’ve had since birth? The big, bad cancer bug?

What other explanation is there?

→ “Regale me with your thoughts on ballet.”

I’m watching football highlights. Alone in the TV room with Dad. I cock my ear at the weird, out-of-nowhere question and shrug. “Rubbish,” I snort.

“You don’t think it’s an incredibly beautiful art form? You’ve never wished to experience it first-hand? You don’t want to glide across Swan Lake or get sweet with a Nutcracker?”

I choke on a laugh. “Is this a wind-up?”

Dad smiles. “Just wanted to check. I got a great offer on tickets to a performance tomorrow. I bought three — anticipating your less than enthusiastic reaction — but I could probably get an extra one if you want to tag along.”

“No way!”

“Your loss.” Dad clears his throat. “The ballet’s out of town and finishes quite late. It will be easier for us to stay in a hotel overnight.”

“Does that mean I’ll have the house to myself?” I ask excitedly.

“No such luck,” he chuckles. “I think you’re old enough to guard the fort, but Sharon…” Mum “…has a different view, and she’s the boss. You’ll have to stay with Aunt Kate.”

“Not no-date Kate,” I groan. Aunt Kate’s only a couple of years older than Mum, but lives like a ninety-year-old. Has a black-and-white TV but only turns it on for the news. Listens to radio the rest of the time. “Couldn’t I kill myself instead?” I quip.

“Don’t make jokes like that!” Dad snaps with unexpected venom. I stare at him, hurt, and he forces a thin smile. “Sorry. Hard day at the office. I’ll arrange it with Kate, then.”

He stumbles as he exits — as if he’s nervous. For a minute there it was like normal, me and Dad messing about, and I forgot all my recent worries. Now they come flooding back. If I’m not for the chop, why was he so upset at my throwaway gag?

Curious and afraid, I slink to the door and eavesdrop as he phones Aunt Kate and clears my stay with her. Nothing suspicious in their conversation. He doesn’t talk about me as if these are my final days. Even hangs up with a cheery “Toodle-pip”, a corny phrase he often uses on the phone. I’m about to withdraw and catch up with the football action when I hear Gret speaking softly from the stairs.

“He didn’t want to come?”

“No,” Dad whispers back.

“It’s all set?”

“Yes. He’ll stay with Kate. It’ll just be the three of us.”

“Couldn’t we wait until next month?”

“Best to do it now — it’s too dangerous to put off.”

“I’m scared, Dad.”

“I know, love. So am I.”

Silence.

→ Mum drops me off at Aunt Kate’s. They exchange some small talk on the doorstep, but Mum’s in a rush and cuts the chat short. Says she has to hurry or they’ll be late for the ballet. Aunt Kate buys that, but I’ve cracked their cover story. I don’t know what Mum and co are up to tonight, but they’re not going to watch a load of poseurs in tights jumping around like puppets.

“Be good for your aunt,” Mum says, tweaking the hairs of my fringe.

“Enjoy the ballet,” I reply, smiling hollowly.

Mum hugs me, then kisses me. I can’t remember the last time she kissed me. There’s something desperate about it.

“I love you, Grubitsch!” she croaks, almost sobbing.

If I hadn’t already known something was very, very wrong, the dread in her voice would have tipped me off. Prepared for it, I’m able to grin and flip back at her, Humphrey Bogart style, “Love you too, shweetheart.”

Mum drives away. I think she’s crying.

“Make yourself comfy in the living room,” Aunt Kate simpers. “I’ll fix a nice pot of tea for us. It’s almost time for the news.”

→ I make an excuse after the news. Sore stomach — need to rest. Aunt Kate makes me gulp down two large spoons of cod-liver oil, then sends me up to bed.

I wait five minutes, until I hear Frank Sinatra crooning — no-date Kate loves Ol’ Blue Eyes and always manages to find him on the radio. When I hear her singing along to some corny ballad, I slip downstairs and out the front door.

I don’t know what’s going on, but now that I know I’m not set to go toes-up, I’m determined to see it through with them. I don’t care what sort of a mess they’re in. I won’t let Mum, Dad and Gret freeze me out, no matter how bad it is. We’re a family. We should face things together. That’s what Mum and Dad always taught me.

Padding through the streets, covering the six kilometres home as quickly as I can. They could be anywhere, but I’ll start with the house. If I don’t find them there, I’ll look for clues to where they might be.

I think of Dad saying he’s scared. Mum trembling as she kissed me. Gret’s voice when she was on the stairs. My stomach tightens with fear. I ignore it, jog at a steady pace, and try spitting the taste of cod-liver oil out of my mouth.

→ Home. I spot a chink of light in Mum and Dad’s bedroom, where the curtains just fail to meet. It doesn’t mean they’re in — Mum always leaves a light on to deter burglars. I slip around the back and peer through the garage window. The car’s parked inside. So they’re here. This is where it all kicks off. Whatever ‘it’ is.

I creep up to the back door. Crouch, poke the dog flap open, listen for sounds. None. I was eight when our last dog died. Mum said she was never allowing another one inside the house — they always got killed on the roads and she was sick of burying them. Every few months, Dad says he must board over the dog flap or get a new door, but he never has. I think he’s still secretly hoping she’ll change her mind. Dad loves dogs.

When I was a baby, I could crawl through the flap. Mum had to keep me tied to the kitchen table to stop me sneaking out of the house when she wasn’t looking. Much too big for it now, so I fish under the pyramid-shaped stone to the left of the door and locate the spare key.

The kitchen’s cold. It shouldn’t be — the sun’s been shining all day and it’s a nice warm night — but it’s like standing in a refrigerator aisle in a supermarket.

I creep to the hall door and stop, again listening for sounds. None.

Leaving the kitchen, I check the TV room, Mum’s fancily decorated living room — off-limits to Gret and me except on special occasions — and Dad’s study. Empty. All as cold as the kitchen.

Coming out of the study, I notice something strange and do a double-take. There’s a chess board in one corner. Dad’s prize chess set. The pieces are based on characters from the King Arthur legends. Hand-carved by some famous craftsman in the nineteenth century. Cost a fortune. Dad never told Mum the exact price — never dared.

I walk to the board. Carved out of marble, ten centimetres thick. I played a game with Dad on its smooth surface just a few weeks ago. Now it’s scarred by deep, ugly gouges. Almost like fingernail scratches — except no human could drag their nails through solid marble. And all the carefully crafted pieces are missing. The board’s bare.

Up the stairs. Sweating nervously. Fingers clenched tight. My breath comes out as mist before my eyes. Part of me wants to turn tail and run. I shouldn’t be here. I don’t need to be here. Nobody would know if I backed up and…

I flash back to Gret’s face after the rat guts prank. Her tears. Her pain. Her smile when she gave me the Tottenham kit. We fight all the time, but I love her deep down. And not that deep either.

I’m not going to leave her alone with Mum and Dad to face whatever trouble they’re in. Like I told myself earlier — we’re a family. Dad’s always said families should pull together and fight as a team. I want to be part of this — even though I don’t know what ‘this’ is, even though Mum and Dad did all they could to keep me out of ‘this’, even though ‘this’ terrifies me senseless.

The landing. Not as cold as downstairs. I try my bedroom, then Gret’s. Empty. Very warm. The chess pieces on Gret’s board are also missing. Mine haven’t been taken, but they lie scattered on the floor and my board has been smashed to splinters.

I edge closer to Mum and Dad’s room. I’ve known all along that this is where they must be. Delaying the moment of truth. Gret likes to call me a coward when she wants to hurt me. Big as I am, I’ve always gone out of my way to avoid fights. I used to think (fear) she might be right. Each step I take towards my parents’ bedroom proves to my surprise that she was wrong.

The door feels red hot, as though a fire is burning behind it. I press an ear to the wood — if I hear the crackle of flames, I’ll race straight to the phone and dial 999. But there’s no crackle. No smoke. Just deep, heavy breathing… and a curious dripping sound.

My hand’s on the door knob. My fingers won’t move. I keep my ear pressed to the wood, waiting… praying. A tear trickles from my left eye. It dries on my cheek from the heat.

Inside the room, somebody giggles — low, throaty, sadistic. Not Mum, Dad or Gret. There’s a ripping sound, followed by snaps and crunches.

My hand turns.

The door opens.

Hell is revealed.

DEMONS

→ Blood everywhere. Nightmarish splashes and gory pools. Wild streaks across the floor and walls.

Except the walls aren’t walls. I’m surrounded on all four sides by webs. Millions of strands, thicker than my arm, some connecting in orderly designs, others running chaotically apart. Many of the strands are stained with blood. Behind the layer of webs, more layers — banks of them stretching back as far as I can see. Infinite.

My eyes snap from the walls. I make quick, mental thumbnails of other details. Numb. Functioning like a machine.

The dripping sound — a body hanging upside down from the webby ceiling in the centre of the room. No head. Blood drops to the floor from the gaping red O of the neck. Even without the head, I recognise him.

“DAD!” I scream, and the cry almost rips my vocal chords apart.

To my left, an obscene creature spins round and snarls. It has the body of a very large dog, the head of a crocodile. Beneath it, motionless — Mum. Or what’s left of her.

A dreadful howl to my right. Gret! Sitting on the floor, staring at me, weaving sideways, her face white, except where it’s smeared with blood. I start to call to her. She half-turns and I realise that she’s been split in two. Something’s behind her, in the cavity at the back, moving her like a hand-puppet.

The ‘something’ pushes Gret away. It’s a child, but no child of this world. It has the body of a three-year-old, with a head much larger than any normal person’s. Pale green skin. No eyes — a small ball of fire flickers in each of its empty sockets. No hair — yet its head is alive with movement. As the hell-child advances, I see that the objects are cockroaches. Living. Feeding on its rotten flesh.

The crocodile-dog moves away from Mum and also closes in on me, exchanging glances with the monstrous child, who’s narrowing the gap.

I can’t move. Fear has seized me completely. I look from Mum to Dad to Gret. All red. All dead.

Impossible! This isn’t happening! A bad dream — it must be!

But even in my very worst nightmare, I never imagined anything like this. I know that it’s real, simply because it’s too awful not to be.

The creatures are almost upon me. The croc-dog growls hungrily. The hell-child grins ghoulishly and raises its hands — there are mouths in both its palms, small, full of sharp teeth. No tongues.

“Oh dear,” someone says, and the creatures stop within spitting distance. “What have we here?”

A man slides out from behind a clump of webby strands. Thin. Pale red skin, misshapen, lumpy, as though made out of coloured dough. His hands are mangled, bones sticking out of the skin, one finger melting into another. Bald. Strange eyes — no white, just a dark red iris and an even darker pupil. There’s a gaping, jagged hole in the left side of his chest. I can look clean through it. Inside the hole — snakes. Dozens of tiny, hissing, coiled serpents, with long curved fangs.

The hell-child shrieks and reaches towards me. The teeth in its small mouths are eagerly snapping open and shut.

“Stop, Artery,” the man — the monster – says commandingly, and steps towards me. No… he doesn’t step… he glides. He has no feet. The lumpy flesh of his lower legs ends in sharp strips which don’t touch the floor. He’s hovering in the air.

The croc-dog barks savagely, its reptilian eyes alive with hunger and hate.

“Hold, Vein,” the monster orders. He advances to within touching distance of me. Stops and studies me with his unnatural red eyes. He has a small mouth. White lips. He looks sad — the saddest creature I’ve ever seen.

“You are Grubitsch,” he says morosely. “The last of the Gradys. You should not be here. Your parents wished to spare you this heartache. Why did you come?”

I can’t answer. My body isn’t my own, except my eyes, which don’t stop roaming and analysing, even though I want them to — easier to shut off completely and black everything out.

The hell-child makes a guttural sound and reaches for me again.

“Disobey me at your peril, Artery,” the monster says softly. The barbaric baby drops its hands and shuffles backwards, the fire in its eyes dimming. The croc-dog retreats too. Both keep their sights on me.

“Such sadness,” the monster sighs, and there’s genuine pity in his tone. “Parents — dead. Sister — dead. All alone in the world. Face to face with demons. No idea who we are or why we’re here.” He pauses and doubt crosses his expression. “You don’t know, do you, Grubitsch? Nobody ever explained, or told you the story of lonely Lord Loss?”

I still can’t answer, but he reads the ignorance in my eyes and smiles thinly, painfully. “I thought not,” he says. “They sought to protect you from the cruelties of the world. Good, loving parents. You’ll miss them, Grubitsch — but not for long.” The creatures to my left and right make sick, chuckling sounds. “Your sorrow shall be short-lived. Within minutes I’ll set my familiars upon you and all will soon finish. There will be pain — great pain — but then the total peace of the beyond. Death will come as a blessing, Grubitsch. You will welcome it in the end — as your parents and sister did.”

The monster drifts around me. I realise he has no nose, just two large holes above his upper lip. He sniffs as he passes, and I somehow understand that he’s smelling my fear.

“Poor Grubitsch,” he murmurs, stopping in front of me again. This close, I can see that his red skin is broken by tiny cracks, seeping with drops of blood. I also notice several appendages beneath his arms — three on either side, folded around his stomach. They look like thin, extra arms, though they might just be oddly moulded layers of flesh.

“Wh-wh… what… are… you?” I moan, forcing the words out between my chattering teeth.

“The beginning and end of your greatest sorrows,” the monster replies. He says it plainly — not a boast.

“Mu-Mum?” I gasp. “Dad? Gr-Gr… Gr…”

“Gone,” he whispers, shaking his head, blood oozing from the cracks in his neck. “Remember them, Grubitsch. Recall the golden memories. Cherish them in these, your final moments. Cry for them, Grubitsch. Give me your tears.”

He smiles eagerly and his right hand reaches for my face. He brushes his mashed-together fingers across my left cheek, just beneath my eye, as though trying to charm tears from me.

The touch of his skin — moist, rough, sticky — repels me. Without thinking, I turn my back on the hell of my parents’ bedroom and run. Behind me, the monster chuckles darkly, clears his throat and says, “Vein. Artery. He is yours.”

With vile, vicious howls of delight, the creatures give chase.

→ The landing. Growls and grinding teeth getting closer every second. Almost upon me. My legs slip. I sprawl to the floor. Something flies overhead and collides with the wall at the top of the stairs — the croc-dog, Vein.

A tiny hand snags on my left ankle. Artery’s teeth close on the turn-ups of my jeans. I pull away instinctively. Ripping — a long strip of material torn clean away. No damage to my leg. Artery rolls backwards, choking on the denim.

Vein scrambles to its feet, shaking its elongated crocodile’s head. My eyes fix on its legs. They don’t end in dog’s paws, but in tiny human hands, with long, blood-stained, splintered nails — a woman’s.

I wriggle past Vein on my stomach and drag myself down the stairs, gasping with terror. Out of the corner of my eye I spy Artery spitting out the denim, jumping to his feet, rushing after me.

Vein crouches at the top of the stairs, reptilian eyes furious, readying itself – herself – to pounce. Just as she leaps, Artery crashes into her. Vein yelps as her companion accidentally crushes her against the wall. Artery wails like a baby, kicks Vein out of the way, and totters down the stairs in pursuit of me.

My hands hit the floor. I lurch to my feet and start for the front door. I’ve a good lead on Artery, who’s still on the stairs. I’m going to make it! A few more strides and…

Something brushes between my legs at an incredible speed. There’s a sharp clattering sound. The door shakes. At its base, Artery rights himself and grins at me. The grotesque hell-child is rubbing his right shoulder, where he collided with the door. The fire in his eyes burns brighter than ever. His mouth is wide and twisted. No tongue — just a gaping, blood-red maw.

I scream incoherently at Artery, then grab the telephone from its stand — the closest object to hand — and lob it with all my strength at the demon. Artery ducks sharply. Unbelievably, the telephone smashes through the door, ending up in the street outside.

I’ve no time to ponder this impossible feat of strength. Artery’s momentarily disorientated. Vein’s only halfway down the stairs. I can escape — if I act quickly.

Making a sharp turn, I dive for the kitchen and the back door. Artery reads my intentions and bellows at Vein. The croc-dog leaps from the stairs and sails for my face and throat. I bring up an arm and swat her away. Vein’s nails catch on my arm, rip through the material of my shirt and make three deep gouges in the flesh of my forearm.

Yelling with pain, I kick out at the demon’s crocodile head. My foot hits it just beneath the tip of its snout. Vein’s head snaps back and she tumbles away with a grunt.

I don’t stop to check on Artery. I burst through to the kitchen and throw myself at the door. My fingers tighten on the handle. I twist — the wrong way! Reverse the movement. A click. The door opens…

…and slams shut again as Artery rams it. The force of the demon banging into the door knocks me aside. I roll out of harm’s immediate way. When I sit up, Artery has recovered and is standing in front of the door, legs and arms spread, three sets of teeth glinting in the glow of the red light cast by the fire of his eyeless sockets.

I back away on my knees from the green-skinned hell-child. Stop — growling to my rear. A panicked glance. Vein closing in, blocking my retreat.

I’m caught between them.

Artery’s smiling. He knows I’m finished. A cockroach topples from his head, lands on its back, rights itself. It starts to scuttle away. Artery steps on the roach and crushes it. Holds his foot up to me, so that I can see the insect’s smeared remains. Laughs evilly.

A snapping sound behind me. The stench of blood and decay. Vein almost upon me. Artery hisses — he wants to join in the bloodshed, but he’s wary. Won’t desert his post. Better to stay and watch Vein kill me than go for the kill himself and leave the door unguarded. I sense the demon’s fear of the one upstairs. He called these two his familiars — that means he’s their master.

Vein butts me in the back with her leathery snout. Growls throatily. It’s over. I’m finished. Dead, like Mum and Dad and…

“No!” I roar, startling the demons. My thoughts flash on the telephone smashing through the sturdy wood of the front door, and Artery and the speed with which he moved. My eyes fix on the dog flap. Much too small to fit through, but I don’t think of that. I focus only on escape.

I bring my legs up. Come to a half-crouch. Propel myself at the dog flap as Vein snaps for me with her teeth. I fly through the air, faster than any human should or could. The fire in Artery’s sockets flares with alarm. The demon snaps his tiny legs together. Too late! Before they close, I’m through, fingers pushing the dog flap up out of the way, arms, body and legs following. Shrieks and howls behind. But they can’t harm me now. I’m flying… outside…free!

→ Soaring. Arms spread like wings. Exhilaration. Magic. Momentary delight. I feel invincible, like a–

Smash!

The backyard fence cuts short my flight. I hit the ground hard. Come up groaning and wheezing. Right elbow cut where I rocketed off the rough wood of the fence. Woozy. I stagger to my feet. Feel sick.

I remember the demons. My eyes snap to the dog flap. I turn to run…

…then stop. No sign of them. Ordinary night silence.

They aren’t following.

I stare at the dog flap — tiny – then at my arms and legs. The three red ravines gouged out by Vein. My shirt and jeans ripped from where the demons snagged me. My left shoe missing — it must have come off mid-flight. But otherwise I’m unharmed.

No way! Even if the dog flap had been bigger, I couldn’t have dived through it at that speed without scraping myself raw. How did…?

All questions die unvoiced as I recall the horror show of the bedroom.

“Mum,” I sob, staggering towards the back door. I pause with my hand on the handle. Almost turn it. Can’t.

I get down on my knees. Cautiously poke open the dog flap. Peer into the kitchen. No demons — but the many bloody prints on the tiles are proof I didn’t imagine the chase.

On my feet. Again I try to enter. Again I can’t bring myself to do it. Memories too terrifying. The demons too threatening. If I could help my family, perhaps it would be different. But they’re dead, all of them, and I have too much sense (or not enough courage) to risk my life for a trio of corpses.

Stepping back from the door, I stare up at the house. It looks like all the others from the outside. No webs. No blood. Normal walls and windows.

“Gret,” I mutter mindlessly. “I never said sorry for the rat guts.”

I think about that for a moment, stunned, sluggish. Then I raise my face, open my mouth and scream.

It’s a wordless scream. Pure hatred. Pure sorrow. It builds from somewhere deep within me and bursts forth with the same impossible force I summoned when lobbing the telephone at Artery and diving through the dog flap.

The glass in the windows shatters and explodes inwards, ripping curtains to shreds, littering floors with jagged, transparent shards. The glass in the houses to either side also explodes. And in the nearby cars and street lamps.

I scream as long as I can — perhaps a full minute without pause — then lapse into a silence as all-encompassing as the scream. It’s an isolated silence. Almost solid. No sounds trickle out and none penetrate.

After a while people emerge from the neighbouring houses, shaken, making their cautious way to the source of the insane howl. I see their mouths moving, but I don’t hear their questions, or their cries when they enter my house and come racing out shortly after, faces white, eyes filled with terror.

I’m in a world of my own. A world of webs and blood. Demons and corpses. Nightmares and terror. The name of the world from this night on — home.

DERVISH

→ Lost, spiralling time. Muddled happenings. Flitting in and out of reality. Momentarily here, then gone, reclaimed by madness and demons.

→ Clarity. A warm room. Police officers. I’m wrapped in blankets. A man with a kind face offers me a mug of hot chocolate. I take it. He’s asking questions. His words sail over and through me. Staring into the dark liquid of the mug, I begin to fade out of reality. To avoid the return to nightmares, I lift my head and focus on his moving lips.

For a long time — nothing. Then whispers. They grow. Like turning up the volume on the TV. Not all his words make sense — there’s a roaring sound inside my head — but I get his general drift. He’s asking about the murders.

“Demons,” I mutter, my first utterance since my soul-wrenching cry.

His face lights up and he snaps forward. More questions. Quicker than before. Louder. More urgent. Amidst the babble, I hear him ask, “Did you see them?”

“Yes,” I croak. “Demons.”

He frowns. Asks something else. I tune out. The world flames at the edges. A ball of madness condenses around me, trapping me, devouring me, cutting off all but the nightmares.

→ A different room. Different officers. More demanding than the last one. Not as gentle. Asking questions loudly, facing me directly, holding my head up until our eyes meet and they have my attention. One holds up a photograph — red, a body torn down the middle.

“Gret,” I moan.

“I know it’s hard,” an officer says, sympathy mixed with impatience, “but did you see who killed her?”

“Demons,” I sigh.

“Demons don’t exist, Grubbs,” the officer growls. “You’re old enough to know that. Look, I know it’s hard,” he repeats himself, “but you have to focus. You have to help us find the people who did this.”

“You’re our only witness, Grubbs,” his colleague murmurs. “You saw them. Nobody else did. We know you don’t want to think about it right now, but you have to. For your parents. For Gret.”

The other cop waves the photo in my face again. “Give us something — anything!” he pleads. “How many were there? Did you see their faces or were they wearing masks? How much of it did you witness? Can you…”

Fading. Bye-bye officers. Hello horror.

→ Screaming. Deafening cries. Looking around, wondering who’s making such a racket and why they aren’t being silenced. Then I realise it’s me screaming.

In a white room. Hands bound by a tight white jacket. I’ve never seen a real one before, but I know what it is — a straitjacket.

I focus on making the screams stop and they slowly die away to a whimper. I don’t know how long I’ve been roaring, but my throat’s dry and painful, as though I’ve been testing its limits for weeks without pause.

There’s a hard plastic mug set in a holder on a small table to my left. A straw sticks out of it. I ease my lips around the head of the straw and swallow. Flat Coke. It hurts going down, but after a couple of mouthfuls it’s wonderful.

Refreshed, I study my cell. Padded walls. Dim lights. A steel door with a strong plastic panel in the upper half, instead of glass.

I stumble to the panel and stare out. Can’t see much — the area beyond is dark, so the plastic’s mostly reflective. I study my face in the makeshift mirror. My eyes aren’t my own — bloodshot, wild, rimmed with black circles. Lips bitten to tatters. Scratches on my face — self-inflicted. Hair cut short, tighter than I’d like. A large purple bruise on my forehead.

A face pops up close on the other side of the glass. I fall backwards with fright. The door opens and a large, smiling woman enters. “It’s OK,” she says softly. “My name’s Leah. I’ve been looking after you.”

“Wh-wh… where am I?” I gasp.

“Some place safe,” she replies. She bends and touches the bruise on my forehead with two soft, gentle fingers. “You’ve been through hell, but you’re OK now. It’s all uphill from here. Now that you’ve snapped out of your delirium, we can work on…”

I lose track of what Leah’s saying. Behind her, in the doorway, I imagine a pair of demons — Vein and Artery. The sane part of me knows they aren’t real, just visions, but that part of me has no control over my senses any more. Backing up against one of the padded walls, I stare blankly at the make-believe demons as they dance around my cell, making crude gestures and mimed threats.

Leah goes on talking. The imaginary Vein and Artery go on dancing. I slip back into the shell of my nightmares — almost gratefully.

→ In and out. Quiet moments of reality. Sudden flashes of insanity and terror.

I’m being held in an institute for people with problems — that’s all any of my nurses will tell me. No names. No mingling with the other patients. White rooms. Nurses — Leah, Kelly, Tim, Aleta, Emilia and others, all nice, all concerned, all unable to coax me back from my nightmares when they strike. Doctors with names which I don’t bother memorising. They examine me at regular intervals. Make notes. Ask questions.

→ What did you see?

→ What did the killers look like?

→ Why do you insist on calling them demons?

→ You know demons aren’t real. Who are the real killers?

One of them asks if I committed the murders. She’s a grey-haired, sharp-eyed woman. Not as kindly as the rest. The ‘bad doctor’ to their ‘good doctors’. She presses me harder as the days slip by. Challenges me. Shows me photos which make me cry.

I start calling her Doctor Slaughter, but only to myself, not out loud. When she comes with her questions and cold eyes, I open myself to the nightmares — always hovering on the edges, eager to embrace me — and lose myself to the real world. After a few of these intentional fade-outs, they obviously decide to abandon the shock tactics and that’s the last I see of Doctor Slaughter.

→ Time dragging or disappearing into nightmares. No ordinary time. No lazy afternoons or quiet mornings. The murders impossible to forget. Grief and fear tainting my every waking and sleeping moment.

Routines are important, according to my doctors and nurses, who wish to put a stop to my nightmarish withdrawals. They’re trying to get me back to real time. They surround me with clocks. Make me wear two watches. Stress the times at which I’m to eat and bathe, exercise and sleep.

Lots of pills and injections. Leah says it’s only temporary, to calm me down. Says they don’t like dosing patients here. They prefer to talk us through our problems, not make us forget them.

The drugs numb me to the nightmares, but also to everything else. Impossible to feel interest or boredom, excitement or despair. I wander around the hospital – I have a free run now that I’m no longer violent — in a daze, zombiefied, staring at clock faces, counting the seconds until my next pill.

→ Off the pills. Coming down hard. Screaming fits. Fighting the nurses. Craving numbness. Needing pills!

They ignore my screams and pleas. Leah explains what’s happening. I’m on a long-term treatment plan. The drugs put a stop to the nightmares and anchored me in the real world — step one. Now I have to learn to function in it as a normal person, free of medicinal depressants — step two.

I try explaining my situation to her — my nightmares won’t ever go away, because the demons I saw were real – but she refuses to listen. Nobody believes me when I talk about the demons. They accept that I was in the house at the time of the murders, and that I witnessed something dreadful, but they can’t see beyond human horrors. They think I imagined the demons to mask the truth. One doctor says it’s easier to believe in demons than evil humans. Says a wicked person is far scarier than a fanciful demon.

Moron! He wouldn’t say that if he’d seen the crocodile-headed Vein or the cockroach-crowned Artery!

→ Gradual improvement. I lose my craving for drugs and no longer throw fits. But I don’t progress as quickly as my doctors anticipated. I keep slipping back into the world of nightmares, losing my grip on reality. I don’t talk openly with my nurses and doctors. I don’t discuss my fears and pains. Sometimes I babble incoherently and can’t interpret the words of those around me. Or I’ll stand staring at a tree or bush through one of the institute windows all day long, or not get up in the morning, despite the best rousing efforts of my nurses. I’m fighting them. They don’t believe my story, so they can’t truly understand me, so they can’t really help me. So I fight them. Out of fear and spite.

→ Somewhere in the middle of the confusion, relatives arrive. The doctors want me to focus on the world outside this institute. They think the way to do that is to reintroduce me to my family, break down my sense of overwhelming isolation. I think the plan is for the visitors to fuss over me, so that I want to be with them, so I’ll then play ball with the doctors when they start in with the questions.

Aunt Kate’s the first. She clutches me tight and weeps. Talks about Mum, Dad and Gret non-stop, recalling all the good times that she can remember. Begs me to let the doctors help me, to talk with them, so I can get better and go home and live with her. I say nothing, just stare off into space and think about Dad hanging upside-down. Aunt Kate leaves less than an hour later, still sobbing.

More relatives drop in during the following days and weeks, rounded up by the doctors. Aunts, uncles, cousins — both sides of the family tree. Some are old acquaintances. Some I’ve never seen before. I don’t respond to any of them. I can tell they’re just like the doctors. They don’t believe me.

Lots of questions from my carers. Why don’t I talk to my relatives? Do I like them? Are there others I prefer? Am I afraid of people? How would I feel about leaving here and staying with one of the well-wishers for a while?

They’re trying to ship me out. It’s not that they’re sick of me — just step three on my path to recovery. Since I won’t rally to their calls in here, they hope that a taste of the real world will make me more receptive. (I haven’t developed any great insights into the human way of thinking — I know all this because Leah and the other nurses tell me. They say it’s good for me to know what they’re thinking, what their plans are.)

I do my best to give them what they want – I’d love if they could cure me — but it’s difficult. The relatives remind me of what happened. They can’t act naturally around me. They look at me with pitying — sometimes fearful — expressions. But I try. I listen. I respond.

→ After much preparation and discussion, I spend a weekend with Uncle Mike and his family. Mike is Mum’s younger brother. He has a pretty wife – Rosetta — and three children, two girls and a boy. Gret and I stayed with them a few times in the past, when Mum and Dad were away on holidays.

They try hard to make me feel welcome. Conor – Mike’s son — is ten years old. He shows me his toys and plays computer games with me. He’s bright and friendly. Talks me through his comics collection and tells me I can pick out any three issues I like and keep them.

The girls – Lisa and Laura — are seven and six. Gigglish. Not sure why I’m here or aware of what happened to me. But they’re nice. They tell me about school and their friends. They want to know if I have a girlfriend.

Saturday goes well. I feel Mike’s optimism — he thinks this will work, that I’ll return to my senses and pick up my life as normal. I try to believe salvation can come that simply, but inside I know I’m deluding myself.

→ Sunday. A stroll in the park. Playing with Lisa and Laura on the swings. Pushing them high. Rosetta close by, keeping a watchful eye on me. Mike on the roundabout with Conor.

“Want off!” Laura shouts. I stop her and she hops to the ground. “Look what I saw!” she yells gleefully, and rushes over to a bush at the side of the swings. I follow. She points to a dead bird — small, young, its body ripped apart, probably by a cat.

“Cool!” Lisa gasps, coming up behind.

“No it’s not,” Rosetta says, wandering over. “It’s sad.”

“Can we take it home and bury it?” Lisa asks.

“I don’t know,” Rosetta frowns. “It looks like it’s been–”

“Demons killed my parents and sister,” I interrupt calmly. The girls stare at me with round, wide eyes. “One of them ripped my dad’s head clean off. Blood was pouring out. Like from a tap.”

“Grubitsch, I don’t think–” Rosetta says.

“One of the demons had the body of a child,” I continue, unable to stop. “It had green skin and no eyes. Instead of hair, its head was covered with cockroaches.”

“That’s enough!” Rosetta snaps. “You’re terrifying the girls. I won’t–”

“The cockroaches were alive. They were eating the demon’s flesh. If I’d looked closely enough, I’m sure I’d have seen its brains.”

Rosetta storms off, Lisa and Laura in tow. Laura’s crying.

I gaze sadly at the dead bird. Nightmares gather around me. Imagined demonic chuckles. The last thing I see in the real world — Mike marching towards me, torn between concern and fury.

→ The institute. Days — weeks? months? – later. Lots of questions.

→ Why did you say that to the girls?

→ Do you want to hurt other people?

→ Are you angry? Sad? Scared?

→ Would you like to visit somebody else?

I don’t answer, or else I grunt in response. They don’t understand. They can’t. I didn’t want to scare Lisa or Laura, or upset Mike and Rosetta. The words came out by themselves. The doctors can’t help. If I had an ordinary illness, I’m sure they could fix me. But I’ve seen demons rip my world to pieces. Nobody believes that, so nobody knows what I’m going through. I’m alone. I always will be. That’s my life now. That’s just the way it is.

→ The relatives stop coming. The doctors stop trying. They say they’re giving me time to recover, but I think they just don’t know how to handle me. Long periods by myself, walking, reading, thinking. Tired most of the time. Headaches. Imaginary demons everywhere I look. Hard to keep food down. Growing thin. Sickly.

The nurses try to rally my spirits. Days out — a circus, theme park, cinemas — and parties in my cell. No good. Their efforts are wasted on me. I draw into myself more and more. Hardly ever speak. Avoid eye contact. Fingers twitch and head twists with fear at the slightest alien sound.

Getting worse. Going downhill.

There’s talk of new pills.

→ A visitor. It’s been a long time since the last. I thought they’d given up.

It’s Uncle Dervish. Dad’s younger brother. I don’t know much about him. A man of mystery. He visited us a few times when I was smaller. Mum never liked him. I recall her and Dad arguing about him once. “We’re not taking the kids there!” she snapped. “I don’t trust him.”

Leah admits Uncle Dervish. Asks if he’d like anything to drink or eat. “No thanks.” Would I like anything? I shake my head. Leah leaves.

Dervish Grady is a thin, lanky man. Bald on top, grey hair at the sides, a tight grey beard. Pale blue eyes. I remember his eyes from when I was a kid. I thought they looked like my toy soldier’s eyes. I asked him if he was in the army. He laughed.

He’s dressed completely in denim — jeans, shirt, jacket. He looks ridiculous — Gret used to say denim looks naff on anyone over the age of thirty. She was right.

Dervish sits in the visitor’s chair and studies me with cool, serious eyes. He’s immediately different to all who’ve come before. Whereas the other relatives were quick to start a false, cheerful conversation, or cry, or say how sorry they were, Dervish just sits and stares. That interests me, so I stare back, more alert than I’ve been in weeks.

“Hello,” I say after a full minute of silence.

Dervish nods in reply.

I try thinking of a follow-up line. Nothing comes to mind.

Dervish looks slowly around the room. Stands, walks to the window, gazes out at the rear yard of the institute, then swings back to the door, which Leah left ajar. He pokes his head out, looks left and right. Closes the door. Returns to the chair and sits. Unbuttons the top of his denim jacket. Slides out three sheets of paper. Holds them face down.

I sit upright, intrigued but suspicious. Is this some new ploy of the doctors? Have they fed Dervish a fresh set of lines and actions, in an attempt to spark my revival?

“I hope this isn’t a Rorschach test,” I grin weakly. “I’ve had enough inkblots to last me a–”

Dervish turns a sheet over and I stop dead. It’s a black-and-white drawing of a large dog with a crocodile’s head and human hands.

“Vein,” Dervish says. He has a soft, lyrical voice.

I tremble and say nothing in reply.

He turns over the second sheet. Colour this time. A child with green skin. Mouths in its palms. Fire in its eyes. Lice for hair.

“Artery,” Dervish says.

“You got the hair wrong,” I mumble. “It should be cockroaches.”

“Lice, cockroaches, leeches — it changes,” he says, and lays the two sheets down on the floor. He turns over the third. This one’s colour too. A thin man, lumpy red skin, large red eyes, mangled hands, no feet, a snake-filled hole where his heart should be.

“The doctors put you up to this,” I moan, averting my eyes. “I told them about the demons. They must have got artists to draw them. Why are you–”

“You didn’t tell them his name,” Dervish cuts me short. He taps the picture. “You said the other two were familiars, and this one was their master — but you never mentioned his name. Do you know it?”

I think back to those few minutes of insanity in my parents’ bedroom. The demon lord didn’t say much. Never told me who he was. I open my mouth to answer negatively…

…then slowly let it close. No — he did reveal his identity. I can’t remember when exactly, but somewhere in amongst the madness there was mention of it. I cast my thoughts back. Zone in on the moment. It was when he asked if I knew why this was happening, if my parents had ever told me the story of–

“Lord Loss,” Dervish says, a split second before I blurt it out.

I stare at him… uncertain… terrified… yet somehow excited.

“I know the demons were real,” Dervish murmurs, picking up the pictures and placing them back inside his jacket, doing up his buttons. He stands. “If you want to come live with me, you can. But you’ll have to sort out the mess you’re in first. The doctors say you won’t respond to their questions. They say they know how to help you, but that you won’t let them.”

“They don’t believe me!” I cry. “How can they cure me when they think I’m lying about the demons?”

“The world’s a confusing place,” Dervish says. “I’m sure your parents told you to always tell the truth, and most of the time that’s good advice. But sometimes you have to lie.” He comes over and bends, so his face is in mine. “These people want to help you, Grubitsch. And I believe they can. But you’re going to have to help them. You’ll have to lie, pretend demons don’t exist, tell them what they want to hear. You have to give a little to get a little. Once you remove that barrier, they can go to work on fixing your brain, on helping you deal with the grief. Then, when they’ve done all they can, you can come to me — if that’s what you want — and I’ll help you with the rest. I can explain about demons. And tell you why your parents and sister died.”

He leaves.

→ Stunned silence. Long days and nights of heavy thinking. Repeating the name of the thin red demon. Lord Loss, Lord Loss, Lord Loss, Lord…

Torn between hope and fear. Could Dervish be in league with the demons? Mum saying, “I don’t trust him.” I’m safe here. Leaving might be an invitation to danger and further sorrow. I won’t improve in this place, holding true to my story, defying the doctors and nurses — but I can’t be harmed either. Out in the real world, I might have to face demons again. Simpler to stay here and hide.

→ One morning I wake from a nightmare. In it, I was at a party, wearing a mask. When I took the mask off, I realised I’d been wearing Gret’s face.

Sitting up in bed. Shaking. Crying. I stare out the window at the world beyond.

I decide.

→ Exercising. Eating sensibly. Putting on weight. Talking directly with my doctors and nurses, answering their questions, letting them into my head, “baring my soul”. I allow them to help me. I work with them. Lie when I have to. Say I saw humans in the room that night. Police come and take my statement. An artist captures my new, realistic, invented impressions of the murderers. My doctors beam proudly and pat my back.

Weeks pass. With help and lots of hard work, I get better. Dervish was right. Now that I’m working with them, they are able to help me, even if we’re progressing on the basis of a lie — that demons aren’t real. I weep a lot and learn a lot — how to face my grief, how to confront my fear and control it — and let them guide me out of the darkness, slowly, painfully, but surely.

In one afternoon session with a therapist, when I judge the time to be right, I make a request. Lots of discussions afterwards. Long debates. Staff meetings. Phone calls. Humming and hawing. Finally they agree. There’s a big build-up. Lots of in-depth therapy sessions and heart-to-hearts. Tests galore, to make sure I’m ready, to reassure themselves that they’re doing the right thing. They have doubts. They voice them. We talk them through. They decide in my favour.

The last day. Handshakes and emergency contact numbers from the doctors in case anything goes wrong. Kisses and hugs from my favourite nurses. A card from Leah. Facing the door, a bag on my shoulder with all I have left in the world. Scared sick but determined to see it through.

I leave the institute on the back of a motorbike. Driving — my rescuer, my lifeline, my hope — Uncle Dervish.

“Hold on tight,” he says. “Speed limits were made to be broken.”

Vroom!

THE GRAND TOUR

→ Dervish drives like a madman, a hundred miles an hour. Howling wind. Blurred countryside. No chance to talk or study the scenery. I spend the journey with my face pressed between my uncle’s shoulder blades, clinging on for dear life.

Finally, coming to a small village, he slows. I peek and catch the name on a sign as we exit — Carcery Vale.

“Carkerry Vale,” I murmur.

“It’s pronounced Car-sherry,” Dervish grunts.

“This is where you live,” I note, recalling the address from cards I wrote and sent with Mum and Gret. (Mum didn’t like Uncle Dervish but she always sent him a Christmas and birthday card.)

“Actually, I live about two miles beyond,” Dervish says, carefully overtaking a tractor and waving to the driver. “It’s pretty lonely out where I am, but there are lots of kids in the village. You can walk in any time you like.”

“Do they know about me?” I ask.

“Only that you’re an orphan and you’re coming to live with me.”

A winding road. Lots of potholes which Dervish swerves expertly to avoid. The sides of the road are lined with trees. They grow close together, blocking out all but the thinnest slivers of sunlight. Dark and cold. I press closer to Dervish, hugging warmth from him.

“The trees don’t stretch back very far,” he says. “You can skirt around them when you’re going to the village.”

“I’m not afraid,” I mutter.

“Of course you are,” he chuckles, then looks back quickly. “But you have my word — you’ve no need to be.”

→ Chez Dervish. A huge house. Three storeys. Built from rough white blocks, almost as big as those I’ve seen in photos of the pyramids. Shaped like an L. The bit sticking out at the end is made from ordinary red bricks and doesn’t look like the rest of the house. Lots of timber decorations around the top and down the sides. A slate roof with three enormous chimneys. The roof on the brick section is flat and the chimney’s tiny in comparison with the others. The windows on the lower floor run from the ground to the ceiling. The windows on the upper floors are smaller, round, and feature stained glass designs. On the brick section they’re very ordinary.

“It’s not much,” Dervish says wryly, “but it’s home.”

“This place must have cost a fortune!” I gasp, standing close to the motorbike, staring at the house, almost afraid to venture any nearer.

“Not really,” Dervish says. “It was a wreck when I bought it. No roof or windows, the interior destroyed by exposure to the elements. The lower floor was used by a local farmer to house pigs. I lived in the brick extension for years while I restored the main building. I keep meaning to tear the extension down – I don’t use it any more, and it takes away from the the main structure — but I never seem to get round to it.”

Dervish removes his helmet, helps me out of mine, then walks me around the outside of the house. He explains about the original architect and how much work he had to do to make the house habitable again, but I don’t listen very closely. I’m too busy assessing the mansion and the surrounding terrain — lots of open fields, sheep and cattle in some of them, a small forest to the west which runs all the way to Carcery Vale, no neighbouring houses that I can see.

“Do you live here alone?” I ask as we return to the front of the house.

“Pretty much,” Dervish says. “One farmer owns most of this land, and he’s opposed to over-development. He’s old. I guess his children will sell plots off when he dies. But for the last twenty years I’ve had all the peace and seclusion a man could wish for.”

“Doesn’t it get lonely?” I ask.

“No,” Dervish says. “I’m fairly solitary by nature. When I’m in need of company, it’s only a short stroll to the village. And I travel a lot — I’ve many friends around the globe.”

We stop at the giant front doors, a pair of them, like the entrance to a castle. No doorbell — just two chunky gargoyle-shaped knockers, which I eye apprehensively.

Dervish doesn’t open the doors. He’s studying me quietly.

“Have you lost the key?” I ask.

“We don’t have to enter,” he says. “I think you’ll grow to love this place after a while, but it’s a lot to take in at the start. If you’d prefer, you could stay in the brick extension — it’s an eyesore, but cosy inside. Or we can drive to the Vale and you can spend a few nights in a B&B until you get your bearings.”

It’s tempting. If the house is even half as spooky on the inside as it looks from out here, it’s going to be hard to adapt to. But if I don’t move in now, I’m sure the house will grow far creepier in my imagination than it can ever be in real life.

“Come on,” I grin weakly, lifting one of the gargoyle knockers and rapping loudly. “We look like a pair of idiots, standing out here. Let’s go in.”

→ Cold inside but brightly lit. No carpets — all tiles or stone floors — but many rugs and mats. No wallpaper — some of the walls are painted, others just natural stone. Chandeliers in the main hall and dining room. Wall-set lamps in the other rooms.

Bookcases everywhere, most of them filled. Chess boards too, in every room — Dervish must be as keen on chess as Mum and Dad. Ancient weapons hang from many of the walls — swords, axes, maces.

“For when the tax collector calls,” Dervish says solemnly, lifting down one of the larger swords. He swings it over his head and laughs.

“Can I try it?” I ask. He hands it to me. “Bloody hell!” It’s H-E-A-V-Y. I can lift it to thigh level but no higher. A quick reappraisal of Uncle Dervish — he looks wiry as a rat, but he must have hidden muscles under all the denim.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/darren-shan/lord-loss/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Darren Shan

The first book in the Demonata, the demonic symphony in ten parts by multi-million-copy bestselling horror writer Darren Shan…When Grubbs Grady first encounters Lord Loss and his evil minions, he learns three things:• the world is vicious,• magic is possible,• demons are real.He thinks that he will never again witness such a terrible night of death and darkness.…He is wrong.

Lord it up with Darren Shan in the shadows of the web at

www.darrenshan.com

For:

Bas — my demon lover

OBEs (Order of the Bloody Entrails) to:

Caroline “pie chart” Paul

D.O.M.I.N.I.C. Kingston

Nicola “schumacher” Blacoe

Editorial Evilness:

Stellasaurus Paskins

Agents of Chaos:

the Christopher Little crew

LORD LOSS

Lord Loss sows all the sorrows of the world

Lord Loss seeds the grief-starched trees

In the centre of the web, lowly Lord Loss bows his head

Mangled hands, naked eyes

Fanged snakes his soul line

Curled inside like textured sin

Bloody, curdled sheets for skin

In the centre of the web, vile Lord Loss torments the dead

Over strands of red, Lord Loss crawls

Dispensing pain, despising all

Shuns friends, nurtures foes

Ravages hope, breeds woe

Drinks moons, devours suns

Twirls his thumbs till the reaper comes

In the centre of the web, lush Lord Loss is all that’s left

Contents

Rat Guts

Demons

Dervish

The Grand Tour

Portraits

Spleen

Carnage in the Forest

A Theory

The Cellar

The Longest Day

Arooooo!

Family Ties

The Curse

The Challenge

The Choice

The Summoning

The Battle

A Change of Plan

Spiral to the Heart of Nowhere

The Change

Other Books by Darren Shan

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

RAT GUTS

→ Double history on a Wednesday afternoon — total nightmare! A few minutes ago, I would have said I couldn’t imagine anything worse. But when there’s a knock at the door, and it opens, and I spot my mum outside, I realise — life can always get worse.

When a parent turns up at school, unexpected, it means one of two things. Either somebody close to you has been seriously injured or died, or you’re in trouble.

My immediate reaction — please don’t let anybody be dead! I think of Dad, Gret, uncles, aunts, cousins. It could be any of them. Alive and kicking this morning. Now stiff and cold, tongue sticking out, a slab of dead meat just waiting to be buried. I remember Gran’s funeral. The open coffin. Her shining flesh, having to kiss her forehead, the pain, the tears. Please don’t let anyone be dead! Please! Please! Please! Ple–

Then I see Mum’s face, white with rage, and I know she’s here to punish, not comfort.

I groan, roll my eyes and mutter under my breath, “Bring on the corpses!”

→ The head’s office. Me, Mum and Mr Donnellan. Mum’s ranting and raving about cigarettes. I’ve been seen smoking behind the bike shed (the oldest cliché in the book!). She wants to know if the head’s aware of this, of what the pupils in his school are getting up to.

I feel a bit sorry for Mr Donnellan. He has to sit there, looking like a schoolboy himself, shuffling his feet and saying he didn’t know this was going on and he’ll launch an investigation and put a quick end to it. Liar! Of course he knew. Every school has a smoking area. That’s life. Teachers don’t approve, but they turn a blind eye most of the time. Certain kids smoke — fact. Safer to have them smoking at school than sneaking off the grounds during breaks and at lunch.

Mum knows that too. She must! She was young once, like she’s always reminding me. Kids were no different in Mum’s time. If she stopped for a minute and thought back, she’d see what a bloody embarrassment she’s being. I wouldn’t mind her having a go at me at home, but you don’t march into school and start laying down the law in the headmaster’s office. She’s out of order — big time.

But it’s not like I can tell her, is it? I can’t pipe up with, “Oi! Mother! You’re disgracing us both, so shut yer trap!”

I smirk at the thought, and of course that’s when Mum pauses for the briefest of moments and catches me. “What are you grinning at?” she roars, and then she’s off again — I’m smoking myself into an early grave, the school’s responsible, what sort of a freak show is Mr Donnellan running, la-di-la-di-la-di-bloody-la!

BAWring!

→ Her rant at school’s nothing compared to the one I get at home. Screaming at the top of her lungs, blue bloody murder. She’s going to send me off to boarding school — no, military school! See how I like that, having to get up at dawn each morning and do a hundred press-ups before breakfast. How does that sound?

“Is breakfast a fry-up or some cereally, yoghurty crap?” is my response, and I know the second it’s out of my mouth that it’s the wrong thing to say. This isn’t the time for the famed Grubbs Grady brand of cutting-edge humour.