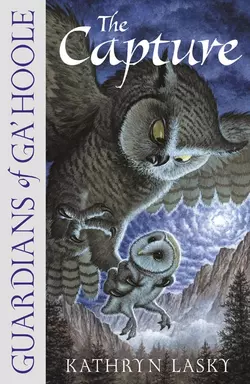

The Capture

Kathryn Lasky

Introducing the newest heroes to children's fiction; the owls of Ga'Hoole. Meet Soren and his friends, the owls charged with keeping owldom safe. Based on Katherine Lasky's work with owls, this adventures series is bound to be a hit with kids. Join the heroic owls in the first of a series of mythic adventures.Out of the darkness a hero will rise…Soren the enthusiastic and young owl is busy learning the rituals of being a barn owl– First Meat Ceremony, how to fly and of course, about the legendary Guardians of Ga'Hoole. However, his life is quickly transformed when he abruptly falls from his parent's cosy nest to the bare and dangerous forest floor.Helpless, he is captured by evil chick snatching owls that bring him to St. Aegolius Academy for Orphaned Owls, where his identify disappears as he receives a number instead of a name.Soren quickly befriends another young owl Gylfie, with whom he works to withstand "moon blinking" (brainwashing), and instead develops plans to escape.But before long, Soren realizes that he in fact has already embarked on an extraordinary adventure with much more excitement in the future.

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_46fcd9ce-e7d0-5953-b97d-bb33e58b123b)

HarperCollins Children’s Books An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

First published in the USA by Scholastic Inc 2003

First published in Great Britain as The Capture by HarperCollins Children’s Books 2006

Text copyright © Kathryn Lasky 2003

Kathryn Lasky asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007215171

Ebook Edition © OCTOBER 2016 ISBN: 9780007369782

Version: 2016-12-02

To Ann Reit, Wise Owl, Great Flight Instructor

… and then the forest of the Kingdom of Tyto seemed to grow smaller and smaller and dimmer and dimmer in the night …

CONTENTS

Cover (#ude917bf8-ab92-55fe-a5e0-4fdc9c92a93c)

Title Page (#u2be7bafb-71a5-574d-ac8b-b2ad4a6edc6c)

Copyright (#ulink_3e492778-2ba8-5650-b2ef-0632ec23dc1b)

Dedication (#u3d3ccf26-9218-53f7-b1f5-62369402e900)

Chapter One: A Nest Remembered (#ulink_8ce8df4f-3efe-58d4-bc72-1a979e35cd83)

Chapter Two: A Life Worth Two Pellets (#ulink_6af51a31-898d-5abd-bc11-5e89bc33b1a6)

Chapter Three: Snatched! (#ulink_df3ba3d6-cf4a-5ebe-a965-cda230d7d9fa)

Chapter Four: St Aegolius Academy for Orphaned Owls (#ulink_a0ff1004-974c-58d6-8a95-9edc6c8bf2bc)

Chapter Five: Moon Blinking (#ulink_f7ec1a1c-ef0e-5690-9665-a18ca2df06b1)

Chapter Six: Separate Pits, One Mind (#ulink_1605d19b-eba3-5d18-b663-2c8e6bf99329)

Chapter Seven: The Great Scheme (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight: The Pelletorium (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine: Good Nurse Finny (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten: Right Side Up in an Upside-down World (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven: Gylfie’s Discovery (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve: Moon Scalding (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen: Perfection! (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen: The Eggorium (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen: The Hatchery (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen: Hortense’s Story (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen: Save the Egg! (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen: One Bloody Night (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen: To Believe (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty: Grimble’s Story (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One: To Fly (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two: The Shape of the Wind (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three: Flying Free (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four: Empty Hollows (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five: Mrs P! (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six: Desert Battle (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven: Hortense’s Eagles (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Other Books By (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_133eb0b3-3be8-575f-a5b8-7a637df8436b)

A Nest Remembered (#ulink_133eb0b3-3be8-575f-a5b8-7a637df8436b)

“Noctus, can you spare a bit more down, darling? I think our third little one is about to arrive. That egg is beginning to crack.”

“Not again!” sighed Kludd.

“What do you mean, Kludd, not again? Don’t you want another little brother?” his father said. There was an edge to his voice.

“Or sister?” His mother sighed the low soft whistle Barn Owls sometimes used.

“I’d like a sister,” Soren peeped up.

“You just hatched out two weeks ago.” Kludd turned to Soren, his younger brother. “What do you know about sisters?”

Maybe, Soren thought to himself, they would be better than brothers. Kludd seemed to have resented him since the moment he had first hatched.

“You really wouldn’t want them arriving just when you’re about to begin branching,” Kludd said dully. Branching was the first step, literally, towards flight. The young owlets would begin by hopping from branch to branch and flapping their wings.

“Now, now, Kludd!” his father admonished. “Don’t be impatient. There’ll be time for branching. Remember, you won’t have your flight feathers for at least another month or more.”

Soren was just about to ask what a month was when he heard a crack. The owl family all seemed to freeze. To any other forest creature the sound would have been imperceptible. But Barn Owls were blessed with extraordinary hearing.

“It’s coming!” Soren’s mother gasped. “I’m so excited.” She sighed again and looked rapturously at the pure white egg as it rocked back and forth. A tiny hole appeared and from it protruded a small spur.

“The egg tooth, by Glaux!” Soren’s father exclaimed.

“Mine was bigger wasn’t it, Da?” Kludd shoved Soren aside for a better look, but Soren crept back up under his father’s wing.

“Oh, I don’t know, son. But isn’t it a pretty, glistening little point? Always gives me a thrill. Such a tiny little thing pecking its way into the big wide world. Ah! Bless my gizzard, the wonder of it all.”

It did indeed seem a wonder. Soren stared at the hole that now began to split into two or three cracks. The egg shuddered slightly and the cracks grew longer and wider. He had done this himself just two weeks ago. This was exciting.

“What happened to my egg tooth, Mum?”

“It dropped off, stupid,” Kludd said.

“Oh,” Soren said quietly. His parents were so absorbed in the hatching that they didn’t reprimand Kludd for his rudeness.

“Where’s Mrs P? Mrs P?” his mother said urgently.

“Right here, ma’am.” Mrs Plithiver, the old blind snake who had been with the owl family for years and years, slithered into the hollow. Blind snakes, born without eyes, served as nest-maids and were kept by many owls to make sure the nests were clean and free of maggots and various insects that found their way into the hollows.

“Mrs P, no maggots or vermin in that corner where Noctus put in fresh down.”

“’Course not, ma’am. Now, how many broods of owlets have I been through with you?”

“Oh, sorry, Mrs P. How could I have ever doubted you? I’m always nervous at the hatching. Each one is just like the first time. I never get used to it.”

“Don’t you apologise, ma’am. You think any other birds would care two whits if their nest was clean? The stories I’ve heard about seagulls! Oh, my goodness! Well, I won’t even go into it.”

Blind snakes prided themselves on working for owls, whom they considered the noblest of birds. Meticulous, the blind snakes had great disdain for other birds, which they felt were less clean due to the unfortunate digestive processes that caused them to excrete only sloppy wet droppings instead of nice neat bundles – the pellets that owls yarped, or coughed up. Although owls did digest the soft parts of their food in a manner similar to other birds, and indeed passed it in a liquid form, for some reason they were never associated by blind snakes with these lesser digestive processes. All the fur and bones and tiny teeth of their prey, like mice, that could not be digested in the ordinary way were pressed into little pellets just the shape and size of the owl’s gizzard. Several hours after eating, the owls would yarp them up. ‘Wet poopers’ is how many nest-maid snakes referred to other birds. Of course, Mrs Plithiver was much too proper to use such coarse language.

“Mum!” Soren gasped. “Look at that.” The nest suddenly seemed to reverberate with a huge cracking sound. Again, only huge to the sensitive ear slits of Barn Owls. Now the egg split. A pale slimy blob flopped out.

“It’s a girl!” A long shree call streamed from his mother’s throat. It was the shree of pure happiness. “Adorable!” Soren’s mother sighed.

“Enchanting!” said Soren’s father.

Kludd yawned and Soren stared dumbfounded at the wet naked thing with its huge bulging eyes sealed tightly shut.

“What’s wrong with her head, Mum?” Soren asked.

“Nothing, dear. Chicks just have very large heads. It takes a while for their bodies to catch up.”

“Not to mention their brains,” Kludd muttered.

“So they can’t hold their heads up right away,” said his mother. “You were the same way.”

“What shall we call the little dear?” Soren’s father asked.

“Eglantine,” Soren’s mother replied immediately. “I have always wanted a little Eglantine.”

“Oooh! Mum, I love that name,” Soren said. He softly repeated the name. Then he tipped towards the little pulsing mass of white. “Eglantine,” he whispered softly, and he thought he saw one little sealed eye open just a slit and a tiny voice seemed to say “hi”. Soren loved his little sister immediately.

One second Eglantine had been this quivering little wet blob, and then, minutes later, it seemed as if she had turned into a fluffy white ball of down. She grew stronger quickly, or so it appeared to Soren. His parents assured him that he too had done exactly the same. That evening it was time for her First Insect ceremony. Her eyes were fully open and she was bawling with hunger. Eglantine could hardly make it through her father’s “Welcome to Tyto” speech.

“Little Eglantine, welcome to the Forest of Tyto, forest of the Barn Owls, or Tyto alba, as we are more formally known. Once upon a time, long long ago, we did indeed live in barns. But now, we and other Tyto cousins live in this forest kingdom known as Tyto. We are rare indeed and we are perhaps the smallest of all the owl kingdoms. Although, in truth, it has been a long long time since we had a king. Someday when you grow up, when you enter your second year, you too will fly out from this hollow and find one of your own in which to live with a mate.”

This was the part of the speech that amazed and disturbed Soren. He simply could not imagine growing up and having a nest of his own. How could he be separated from his parents? And yet there was this urge to fly, even now with his stubby little wings that lacked even the smallest sign of true flight feathers. “And now,” Soren’s father continued, “it is time for your First Insect ceremony.” He turned to Soren’s mother. “Marella, my dear, can you bring forward the cricket?”

Soren’s mother stepped up. In her beak she held one of the summer’s last crickets. “Eat up, young’un! Headfirst. Yes, down the beak. Yes, always headfirst – that’s the proper way, be it cricket, mouse or vole.”

“Mmmm,” sighed Soren’s father as he watched his daughter swallow the cricket. “Dizzy in the gizzy, ain’t it so?!”

Kludd blinked and yawned. Sometimes his parents really embarrassed him, especially his da with his stupid jokes. “Wit of the wood!” muttered Kludd.

That dawn, after the owls had settled down, Soren was still so excited by his little sister’s arrival that he could not sleep. His parents had retired to the ledge above him where they slept, but he could hear their voices threading through the dim morning light that filtered into the hollow.

“Oh, Noctus, it is very strange – another owlet disappeared?”

“Yes, my dear, I’m afraid so.”

“How many is that now in the last few days?”

“Fifteen missing, I believe.”

“That is many more than can be accounted for by raccoons.”

“Yes,” Noctus replied grimly. “And there is something else.”

“What?” his wife replied in a lower wavering hoot.

“Eggs.”

“Eggs?”

“Eggs have disappeared.”

“Eggs from a nest?”

“Yes, I’m afraid so.”

“No!” Marella Alba gasped. “I have never heard of such a thing. It’s unspeakable.”

“I thought I must tell you in case we are blessed with another brood.”

“Oh, great Glaux,” his mother gasped. Soren’s eyes blinked wide. He had never heard his mother swear before. “But we so seldom leave the nest during broody times. Whoever it is must watch us.” She paused. “Watch us constantly.”

“Whoever it is can fly or climb,” Noctus Alba said darkly.

Soren felt a sense of dread seep into the hollow. How thankful he was that Eglantine had not been snatched while just an egg. He vowed he would never leave her alone.

It seemed to Soren that as soon as Eglantine ate her first insect she never stopped eating. His mother and father assured him that he had been the same. “And you still are, Soren! And it’s almost time for your first Fur-on-Meat ceremony!”

That was what life was like those first weeks in the nest – one ceremony after another. Each, it seemed in some way or another, led to the truly biggest, perhaps the most solemn yet joyous moment in a young owl’s life: First Flight.

“Fur!” whispered Soren. He couldn’t quite imagine what it was like. What it would feel like slipping down his throat. His mother always stripped off all the fur from the meat and then tore out the bones before offering the little tidbits of fresh mouse or squirrel to Soren. Kludd was almost ready for his First Bones ceremony when he would be allowed to eat “the whole bit” as Soren’s father said. And it was just before First Bones that a young owl began branching. And just after that, it would begin its first real flight under the watchful eyes of its parents.

“Hop! Hop! That’s it, Kludd! Now, up with the wings just as you begin the hop to that next branch. And remember, you are just branching now. No flying. And even after your first flight lessons, no flying by yourself until Mum and I say so.”

“Yes, Da!” Kludd said in a bored voice. Then he muttered, “How many times have I heard this lecture!”

Soren had heard it many many times too, even though he was nowhere near branching. The worst thing a young owl could do was to try to fly before it was ready. And, of course, young owls usually did this when their parents were out hunting. It was so tempting to try one’s newly fledged wings, but it would most likely end in a disastrous crash, leaving the little owlet nestless, perhaps badly injured, and on the ground exposed to dangerous predators. The lecture was brief this time, and the branching lesson resumed.

“Crisply! Crisply, boy! Keep the noise down. Owls are silent fliers.”

“But I’m not flying yet, Da! As you keep reminding me constantly! What’s it matter if I’m noisy now when I’m just branching?”

“Bad habit! Bad habit! Leads to noisy flight. Hard to outgrow noise habits started in branching.”

“Oh, bother!”

“Oh, I’ll bother you!” Noctus exploded, and gave his son a cuff on the head that nearly tipped him over. Soren had to admit that Kludd didn’t even whimper but just picked himself up and gave his da a glaring look and resumed hopping – slightly less noisily than before.

There was a series of soft short hisses from Mrs Plithiver. “Difficult one, that one! My! My! Glad your mum’s not here to see this. Eglantine!” Mrs Plithiver called out suddenly. Even though she was blind she seemed to know exactly what the young owlets were doing at any given moment. She now heard the crunch of a nest bug in Eglantine’s beak. “Put that nest bug down. Owls do not eat nest bugs. That’s what house snakes do. If you keep it up, you’ll just grow fat and squishy and won’t be prepared for your First Meat ceremony, and then no First Fur, and then no First Bones, and then no, well, you know what. Now your mum is just out looking for a nice chubby vole with soft fur for Soren’s First Fur ceremony. And she might even find a nice wriggly little centipede for you.”

“Ooh, they’re so much fun to eat!” Soren exclaimed. “All their little legs pittering down your gullet.”

“Oh, Soren, tell me that story about the first time you ate a centipede,” Eglantine begged.

Mrs Plithiver sighed softly. It was so sweet! Eglantine hung on every word of Soren’s. True sisterly love, and Soren loved her right back. She wasn’t sure what exactly had happened with their older brother, Kludd. There was always one difficult one in a brood, but Kludd was more than just difficult. There was something … something … Mrs Plithiver thought hard. Just something missing with Kludd. Something rather unnatural, un-owlish.

“Sing the centipede song, Soren! Sing it!”

Soren opened his beak wide and began to sing:

What gives a wriggle

And makes you giggle

When you eat ’em?

Whose weensy little feet

Make my heart really beat?

Why, it’s those little creepy crawlies

That make me feel so jolly.

For the darling centipede

My favourite buggy feed

I always want some more.

That’s the insect I adore

More than beetles, more than crickets,

Which at times give me the hiccups.

I crave only to feed

On a juicy centipede

And I shall be happy forevermore.

Just as Soren finished the song, his mother flew into the hollow and dropped a vole at her feet. “A nice fat one, my dear. Enough for your First Fur ceremony and Kludd’s First Bones.”

“I want my own!” Kludd said.

“Nonsense, dear, you could never eat a whole vole.”

“Whole vole!” squeaked Eglantine. “Oh, Mum, it rhymes. I love rhymes.”

“I want one all for myself,” Kludd persisted.

“Now, look here, Kludd.” Marella fixed her son in a dark steady gaze. “We do not waste food around here. This is a very large vole. There is enough for you to have your First Bones ceremony, Soren to have his First Fur ceremony, and Eglantine to have her First Meat.”

“Meat! I get to eat meat!” Eglantine gave a little hop of excitement. She seemed to have forgotten all about the joys of centipedes.

“And so, Kludd, when you want a vole all of your own, you can just go out and hunt it for yourself! I spent most of the night tracking down this one. Food is scarce in Tyto this time of year. I’m exhausted.” A huge orange moon sailed in the autumn sky. It seemed to hover just above the great fir tree where Soren and his family lived, and it cast a soft glow in through the opening of the hollow. It was indeed a perfect night for the ceremonies which these owls loved and that marked their growth and the passage of time.

And so that night, just before the dawn, the three little owlets had their First Meat, First Fur and First Bone ceremonies. And Kludd yarped his first real pellet. It was the exact shape of his gizzard, which had pressed it into the tight little bundle of bones and fur. “Oh, that’s a fine pellet, son,” Kludd’s father said.

“Yes, indeed,” his mother agreed. “Quite admirable.” And Kludd, for once, seemed satisfied. And Mrs Plithiver thought privately to herself how no bird could be really bad that had such a noble digestive system.

That night, from the time the big orange moon began to slip down in the sky until the first grey streaks of the new dawn, Noctus Alba told the stories that owls had loved to hear from the time of Glaux. Glaux was the most ancient order of owls from which all other owls descended.

So his father began:

“Once upon a very long time ago, in the time of Glaux, there was an order of knightly owls, from a kingdom called Ga’Hoole, who would rise each night into the blackness and perform noble deeds. They spoke no words but true ones, their purpose was to right all wrongs, to make strong the weak, mend the broken, vanquish the proud, and make powerless those who abused the frail. With hearts sublime they would take flight—”

Kludd yawned. “Is this a true story or what, Da?”

“It’s a legend, Kludd,” his father answered.

“But is it true?” Kludd whined. “I only like true stories.”

“A legend, Kludd, is a story that you begin to feel in your gizzard and then over time it becomes true in your heart. And perhaps makes you become a better owl.”

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_1418266a-254c-578d-bf60-b5c609a1272c)

A Life Worth Two Pellets (#ulink_1418266a-254c-578d-bf60-b5c609a1272c)

True in your heart! Those words in the deep throaty hoot of his father were perhaps the last thing Soren remembered before he landed with a soft thud on a pile of moss. Shaking himself and feeling a bit dazed, he tried to stand up. Nothing seemed broken. But how had this happened? He certainly had not tried flying while his parents were out hunting. Good Glaux. He hadn’t even tried branching yet. He was still far from “flight readiness” as his mum called it. So how had this happened? All he knew was, one moment he was near the edge of the hollow, peering out, looking for his mum and da to come home from hunting, and the next minute he was tumbling through the air.

Soren tipped his head up. The fir tree was so tall and he knew that their hollow was near the very top. What had his father said – ninety feet, one hundred feet? But numbers had no meaning for Soren. Not only could he not fly, he couldn’t count either. Didn’t really know his numbers. But there was one thing that he did know: he was in trouble – deep, frightening, horrifying trouble. The boring lectures that Kludd had complained about came back to him. The weight of the terrible truth now pressed upon him in the darkness of the forest – those grim words, “an owlet that is separated from its parents before it has learned to fly and hunt cannot survive”.

And Soren’s parents were gone, gone on a long hunting flight. There had not been many since Eglantine had hatched out. But they needed more food, for winter was coming. So right now Soren was completely alone. He could not imagine being more completely alone as he gazed up at the tree that seemed to vanish into the clouds. He sighed and muttered, “So alone, so alone.”

And yet, deep inside him something flickered like a tiny smouldering spark of hope. When he had fallen, he must have done something with his nearly bald wings that “had captured the air” as his father would say. He tried now to recall that feeling. For a brief instant, falling had actually felt wonderful. Could he perhaps recapture that air? He tried to lift his wings and flutter them slightly. Nothing. His wings felt cold and bare in the crisp autumn breeze. He looked at the tree again. Could he climb, using his talons and beak? He had to do something fast or he would become some creature’s next meal – a rat, a raccoon. Soren felt faint at the very thought of a raccoon. He had seen them from the nest – bushy, masked, horrible creatures with sharp teeth. He must listen carefully. He must turn and tip his head as his parents had taught him. His parents could listen so carefully that, from high above in their tree hollow, they could hear the heartbeat of a mouse on the forest floor below. Surely he should be able to hear a raccoon. He cocked his head and nearly jumped. He did hear a sound. It was a small, raspy, familiar voice from high up in the fir tree. “Soren! Soren!” it called from the hollow where his brother and sister still nestled in the fluffy pure white down that their parents had plucked from beneath their flight feathers. But it was neither Kludd nor Eglantine.

“Mrs Plithiver!” Soren cried.

“Soren … are you … are you alive? Oh dear, of course you are if you can say my name. How stupid of me. Are you well? Did you break anything?”

“I don’t think so, but how will I ever get back up there?”

“Oh dear oh dear!” Mrs Plithiver moaned. She was not much good in a crisis. One could not expect such things of nest-maids, Soren supposed.

“How long until Mum and Da get home?” Soren called up.

“Oh, it could be a long while, dearie.”

Soren had hop-stepped to the roots of the tree that ran above the ground like gnarled talons. He could now see Mrs Plithiver, her small head with its glistening rosy scales hovering over the edge of the hollow. Where Mrs Plithiver’s eyes should have been there were two small indentations. “This is simply beyond me,” she sighed.

“Is Kludd awake? Maybe he could help me.”

There was a long pause before Mrs Plithiver answered weakly, “Well, perhaps.” She sounded hesitant. Soren could hear her now, nudging Kludd. “Don’t be grumpy, Kludd. Your brother has … has … taken a tumble, as it were.”

Soren heard his brother yawn. “Oh my,” Kludd sighed and didn’t sound especially upset, Soren thought. Soon the large head of his big brother peered over the edge of the hollow. His white heart-shaped face with the immense dark eyes peered down on Soren. “I say,” Kludd drawled. “You’ve got yourself in a terrible fix.”

“I know, Kludd. Can’t you help? You know more about flying than I do. Can’t you teach me?”

“Me teach you? I wouldn’t know where to begin. Have you gone yoicks?” He laughed. “Stark-raving yoicks. Me teach you?” He laughed again. There was a sneer embedded deep within the laugh.

“I’m not yoicks. But you’re always telling me how much you know, Kludd.” This was certainly the truth. Kludd had been bragging about his superiority ever since Soren had hatched out. He should get the favourite spot in the hollow because he was already losing his downy fluff in preparation for his flight feathers and therefore would be colder. He deserved the largest hunks of mouse meat because he, after all, was on the brink of flying. “You’ve already had your First Flight ceremony. Tell me how to fly, Kludd.”

“One cannot tell another how to fly. It’s a feeling, and besides, it is really a job for Mum and Da. It would be very impertinent of me to usurp their position.”

Soren had no idea what “usurp” meant. Kludd often used big words to impress him.

“What are you talking about? Usurp?” Sounded like “yarp” to Soren. But what would yarping have to do with teaching him to fly? Time was running out. The light was leaking out of the day’s end and the evening shadows were falling. The raccoons would soon be out.

“I can’t do it, Soren,” Kludd replied in a very serious voice. “It would be extremely improper for a young owlet like myself to assume this role in your life.”

“My life isn’t going to be worth two pellets if you don’t do something. Don’t you think it is improper for you to let me die? What will Mum and Da say to that?”

“I think they will understand completely.”

Great Glaux! Understand completely! He had to be yoicks. Soren was simply too dumbfounded. He could not say another word.

“I’m going to get help, Soren. I’ll go to Hilda’s,” he heard Mrs P rasp. Hilda was another nest-maid snake for an owl family in a tree near the banks of the river.

“I wouldn’t if I were you, P.” Kludd’s voice was ominous. It made Soren’s gizzard absolutely quiver.

“Don’t call me P. That’s so rude.”

“That’s the last thing you have to worry about P – me being rude.”

Soren blinked.

“I’m going, Kludd. You can’t stop me,” Mrs Plithiver said firmly.

“Can’t I?”

Soren heard a rustling sound above. Good Glaux, what was happening?

“Mrs Plithiver?” Only silence now. “Mrs Plithiver?” Soren called again. Maybe she had gone to Hilda’s. He could only hope, and wait.

It was nearly dark now and a chill wind rose up. There was no sign of Mrs Plithiver returning. “First teeth” – isn’t that what Da always called these early cold winds? – the first teeth of winter. The very words made poor Soren shudder. When his father had first used this expression, Soren had no idea what “teeth” even were. His father explained that they were something that owls didn’t have, but most other animals did. They were for tearing and chewing food.

“Does Mrs Plithiver have them?” asked Soren. Mrs Plithiver had gasped in disgust.

His mother said, “Of course not, dear.”

“Well, what are they exactly?” Soren had asked.

“Hmm,” said his mother as she thought a moment. “Just imagine a mouth full of beaks – yes, very sharp beaks.”

“That sounds very scary.”

“Yes, it can be,” his mother replied. “That is why you do not want to fall out of the hollow or try to fly before you’re ready, because raccoons have very sharp teeth.”

“You see,” his father broke in, “we have no need for such things as teeth. Our gizzards take care of all that chewing business. I find it rather revolting, the notion of actually chewing something in one’s mouth.”

“They say it adds flavour, darling,” his mother added.

“I get flavour, plenty of flavour, in my gizzard. Where do you think that old expression ‘I know it in my gizzard’ comes from? Or ‘I have a feeling in my gizzard’, Marella?”

“Noctus, I’m not sure if that is the same thing as flavour.”

“That mouse we had for dinner last night – I can tell you from my gizzard exactly where he had been of late. He had been feasting on the sweet grass of the meadow mixed with the nooties from that little Ga’Hoole tree that grows down by the stream. Great Glaux! I don’t need teeth to taste.”

Oh dear, thought Soren, he might never hear this gentle bickering between his parents again. A centipede pittered by and Soren did not even care. Darkness gathered. The black of the night grew deeper and from down on the ground he could barely see the stars. This perhaps was the worst. He could not see sky through the thickness of the trees. How much he missed the hollow. From their nest, there was always a little piece of the sky to watch. At night, it sparkled with stars or raced with clouds. In the daytime, there was often a lovely patch of blue, and sometimes towards evening, before twilight, the clouds turned bright orange or pink. There was an odd smell down here on the ground – damp and mouldy. The wind sighed through the branches above, through the leaves and the needles of the forest trees, but down on the ground … well, the wind didn’t seem to even touch the ground. There was a terrible stillness. It was the stillness of a windless place. This was no place for an owl to be. Everything was different.

If his feathers had been even half-fledged, he could have plumped them up and the downy fluff beneath the flight feathers would have kept him warm. He supposed he could try calling for Eglantine. But what use would she be? She was so young. Besides, if he called out, wouldn’t that alert other creatures in the forest that he was here? Creatures with teeth!

He guessed his life wasn’t worth two pellets. But even worthless, he still missed his parents. He missed them so much that the missing felt sharp. Yes, he did feel something in his gizzard as sharp as a tooth.

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_93293d00-a739-5c17-ae41-dc6f6660c83f)

Snatched! (#ulink_93293d00-a739-5c17-ae41-dc6f6660c83f)

Soren was dreaming of teeth and of the heartbeats of mice when he heard the first soft rustlings overhead. “Mum! Da!” he cried out in his half sleep. He would forever regret calling out those two words, for suddenly, the night was ripped with a shrill screech and Soren felt talons wrap around him. Now he was being lifted. And they were flying fast, faster than he could think, faster than he could ever imagine. His parents never flew this fast. He had watched them when they took off or came back from the hollow. They glided slowly and rose in beautiful lazy spirals into the night. But now, underneath, the earth raced by. Slivers of air blistered his skin. The moon rolled out from behind thick clouds and bleached the world with an eerie whiteness. He scoured the landscape below for the tree that had been his home. But the trees blurred into clumps, and then the forest of the Kingdom of Tyto seemed to grow smaller and smaller and dimmer and dimmer in the night, until Soren could not stand to look down any more. So he dared to look up.

There was a great bushiness of feathers on the owl’s legs. His eyes continued upward. This was a huge owl – or was it even an owl? Atop this creature’s head, over each eye, were two tufts of feathers that looked like an extra set of wings. Just as Soren was thinking this was the strangest owl he had ever seen, the owl blinked and looked down. Yellow eyes! He had never seen such eyes. His own parents and his brother and sister all had dark, almost black eyes. His parents’ friends who occasionally flew by had brownish eyes, perhaps some with a tinge of tawny gold. But yellow eyes? This was wrong. Very wrong!

“Surprised?”

The owl blinked, but Soren could not reply. So the owl continued. “Yes, you see, that’s the problem with the Kingdom of Tyto – you never see any other kind of owl but your own kind – lowly, undistinguished Barn Owls.”

“That’s not true,” said Soren.

“You dare contradict me!” screeched the owl.

“I’ve seen Grass Owls and Masked Owls. I’ve seen Bay Owls and Sooty Owls. Some of my parents’ very best friends are Grass Owls.”

“Stupid! They’re all Tytos,” the owl barked at him.

Stupid? Grown-ups weren’t supposed to speak this way – not to young owls, not to chicks. It was mean. Soren decided he should be quiet. He would stop looking up.

“We might have a haggard here,” he heard the owl say. Soren turned his head slightly to see who the owl was speaking to.

“Oh, great Glaux! One wonders if it is worth the effort.” This owl’s eyes seemed more brown than yellow and his feathers were spattered with splotches of white and grey and brown.

“Oh, I think it is always worth the effort, Grimble. And don’t let Spoorn hear you talking that way. You’ll get a demerit and then we’ll all be forced to attend another one of her interminable lectures on attitude.”

This owl looked different as well. Not nearly as big as the other owl and his voice made a soft tingg-tingg sound. It was at least a minute before Soren noticed that this owl was also carrying something in his talons. It was a creature of some sort and it looked rather owlish, but it was so small, hardly larger than a mouse. Then it blinked its eyes. Yellow! Soren resisted the urge to yarp. “Don’t say a word!” the small owl said in a squeaky whisper. “Wait.”

Wait for what? Soren wondered. But soon he felt the night stir with the beating of other wings. More owls fell in beside them. Each one carried an owlet in its talons. Then there was a low hum from the owl that gripped Soren. Gradually, the other owls flanking them joined in. Soon the air thrummed with a strange music. “It’s their hymn,” whispered the tiny owl. “It gets louder. That’s when we can talk.”

Soren listened to the words of the hymn.

Hail to St Aegolius

Our Alma Mater.

Hail, our song we raise in praise of thee

Long in the memory of every loyal owl

Thy splendid banner emblazoned be.

Now to thy golden talons

Homage we’re bringing.

Guiding symbol of our hopes and fears

Hark to the cries of eternal praises ringing

Long may we triumph in the coming years.

The tiny owl began to speak as the voices swelled in the black of the night. “My first words of advice are to listen rather than speak. You’ve already got yourself marked as a wild owl, a haggard.”

“Who are you? What are you? Why do you have yellow eyes?”

“You see what I mean! That is the last thing that you should worry about.” The tiny owl sighed softly. “But I’ll tell you. I am an Elf Owl. My name is Gylfie.”

“I’ve never seen one in Tyto.”

“We live in the high desert kingdom of Kuneer.”

“Do you ever grow any bigger?”

“No. This is it.”

“But you’re so small and you’ve got all of your feathers, or almost.”

“Yes, this is the worst part. I was within a week or so of flying when I got snatched.”

“But how old are you?”

“Twenty nights.”

“Twenty nights!” Soren exclaimed. “How can you fly that young?”

“Elf Owls are able to fly by twenty-seven or thirty nights.”

“How much is sixty-six nights?” Soren asked.

“A lot.”

“I’m a Barn Owl and we can’t fly for sixty-six nights. But what happened to you? How did you get snatched?”

Gylfie did not answer right away. Then slowly, “What is the ONE thing that your parents always tell you not to do?”

“Fly before you’re ready?” Soren said.

“I tried and I fell.”

“But I don’t understand. It would have been only a week, you said.” Soren, of course, wasn’t sure how long a week was or how long twenty-seven nights were, but it all sounded shorter than sixty-six.

“I was impatient. I was well on my way to growing feathers but had grown no patience.” Gylfie paused again. “But what about yourself? You must have tried it too.”

“No. I don’t really know what happened. I just fell out of the nest.” But the second Soren said those words he felt a weird queasiness. He almost knew. He just couldn’t quite remember, but he almost knew how it had happened, and he felt a mixture of dread and shame creep through him. He felt something terrible deep in his gizzard.

CHAPTER FOUR (#ulink_909764e8-c5a4-514c-a3ea-c0395798d05f)

St Aegolius Academy for Orphaned Owls (#ulink_909764e8-c5a4-514c-a3ea-c0395798d05f)

The owls began to bank in steep turns as they circled downwards. Soren blinked and looked down. There was not a tree, not a stream, not a meadow. Instead, immense rock needles bristled up, and cutting through them were deep stone ravines and jagged canyons. This could not be Tyto. That was all that Soren could think.

Down, down, down they plunged in tighter and tighter circles, until they alighted on the stony floor of a deep, narrow canyon. And although Soren could indeed see the sky from which they had just plunged, it seemed farther away than ever. Above, there was the sound of wind, distant yet shrill as it whistled across the upper reaches of this harsh stone world. Then, piercing through the shriek of the wind, came a voice even louder and sharper.

“Welcome, owlets. Welcome to St Aegolius. This is your new home. It is here that you will find truth and purpose. Yes, that is our motto. When Truth Is Found, Purpose Is Revealed.”

The immense, ragged Great Horned Owl fixed them in her yellow gaze. The tufts above her eyes swooped up. The shoulder feathers on her left wing had separated, revealing an unsightly patch of skin with a jagged white scar. She was perched on a rock outcropping in the granite ravine where they had been brought. “I am Skench, Ablah General of St Aegolius. My job is to teach you the Truth. We discourage questions here as we feel they often distract from the Truth.” Soren found this very confusing. He had always asked questions, ever since he had hatched out.

Skench, the Ablah General, was continuing her speech. “You are orphans now.” The words shocked Soren. He was not an orphan! He had a mum and da, perhaps not here, but out there somewhere. Orphan meant your parents were dead. How dare this Skench, the Ablah blah blah blah or whatever she called herself, say he was an orphan!

“We have rescued you. It is here at St Aggie’s that you shall find everything that you need to become humble, plain servants of a higher good.”

This was the most outrageous thing Soren had ever heard. He hadn’t been rescued, he had been snatched away. If he had been rescued, these owls would have flown up and dropped him back in his family’s nest. And what exactly was a higher good?

“There are many ways in which one can serve the higher good, and it is our job to find out which best suits you and to discover what your special talents are.” Skench narrowed her eyes until they were gleaming amber slits in her feathery face. “I am sure that each and every one of you has something special.”

At that very moment, there was a chorus of hoots and many owl voices were raised in song.

To find one’s special quality

One must lead a life of deep humility.

To serve in this way

Never question but obey

Is the blessing of St Aggie’s charity.

At the conclusion of the short song Skench, the Ablah General, swooped down from her stone perch. She fixed them all in the glare of her eyes. “You are embarking on an exciting adventure, little orphans. After I have dismissed you, you shall be led to one of four glaucidiums, where two things shall occur. You shall receive your number designation. And you shall also receive your first lesson in the proper manner in which to sleep and shall be inducted into the march of sleep. These are the first steps towards the Specialness ceremony.”

What in the world was this owl talking about? Soren wondered. Number designation? What was a glaucidium, and since when did an owl have to be taught to sleep? And a sleep march? What was that? And it was still night. What owl slept at night? But before he could really ponder these questions, he felt himself being gently shoved into a line, a separate line from the little Elf Owl called Gylfie. He turned his head nearly completely around to search for Gylfie and caught sight of her. He raised a stubby wing to wave but Gylfie did not see him. He saw her marching ahead with her eyes looking straight ahead.

The line Soren was in wound its way through a series of deep gorges. It was like a stone maze of tangled trails through the gaps and canyons and notches of this place called St Aegolius Academy for Orphaned Owls. Soren had the unsettling feeling that he might never see the little Elf Owl again and, even worse, it would be impossible to ever find one’s way out of these stone boxes into the forest world of Tyto, with its immense trees and sparkling streams.

They finally came to stop in a circular stone pit. A white owl with very thick feathers waddled towards them and blinked. Her eyes had a soft yellow glow.

“I am Finny, your pit guardian.” And then she giggled softly. “Some have been known to call me their pit angel.” She gazed sweetly at them. “I would love it if you would all call me Auntie.”

Auntie? Soren wondered. Why would I ever call her Auntie? But he remembered not to ask.

“I must, of course, call you by your number designation, which you shall shortly be told,” said Finny.

“Oh, goody!” A little Spotted Owl standing next to Soren hopped up and down.

This time, Soren remembered too late that questions were discouraged. “Why do you want a number instead of your name?”

“Hortense! You wouldn’t like that name, either,” the Spotted Owl whispered. “Now, shush. Remember, no questions.”

“You shall, of course,” Finny continued, “if you are good humble owlets and learn the lessons of humility and obedience, earn your Specialness rank and then receive your true name.”

But my true name is Soren. It is the name my parents gave me. The words pounded in Soren’s head and even his gizzard seemed to tremble in protest.

“Now, let’s line up for our Number ceremony, and I have a tempting little snack here for you.”

There were perhaps twenty owls in Soren’s group and Soren was towards the middle of the line. He watched as the white owl, Auntie or Finny, whom Hortense had informed him was a Snowy Owl, dropped a piece of fur-stripped mouse meat on the stone before each owl in turn and then said, “Why, you’re number 12-6. What a nice number that is, dearie.”

Every number was either “nice” or “dear” or “darling”. Finny bent her head solicitously and often gave a friendly little pat to the owlet just “numbered”. She was full of quips and little jokes. Soren was just beginning to feel that things perhaps could be worse, and he hoped that Gylfie had such a nice owl for a pit guardian, when the huge fierce owl with the tufts over each eye, the very one who had snatched him and called him stupid, alighted down next to Finny. Soren felt a cold dread steal over his gizzard as he saw the owl look directly at him and then dip his head and whisper something into Finny’s ear. Finny nodded and looked at him blandly. They were talking about him. Soren was sure. He could barely move his talons forwards on the hard stone towards Finny. His turn was coming up soon. Only four more owls before he would be “numbered”.

“Hello, sweetness,” Finny cooed as Soren stepped forwards. “I have a very special number for you!” Soren was silent. Finny continued, “Don’t you want to know what it is?” This is a trick. Questions are discouraged. I’m not supposed to ask. And that was exactly what Soren said.

“I’m not supposed to ask.” The soft yellow glow streamed from Finny’s eyes. Soren felt a moment’s confusion. Then Finny leaned forwards and whispered to him. “You know, dear, I’m not as strict as some. So please, if you really really need to ask a question, just go ahead. But remember to keep your voice down. And here, dear, is a little extra piece of mouse. And your number …” She sighed and her entire white face seemed to glow with the yellow light. “My favourite – 12-1. Isn’t it sublime! It’s a very special number, and I am sure that you will discover your very own specialness as an owl.”

“Thank you,” Soren said, still slightly mystified but relieved that the fierce owl had apparently not told Finny anything bad about him.

“Thank you, what?” Finny giggled. “See? I get to ask questions too, sometimes.”

“Thank you, Finny?”

Finny inclined her head towards him again. There was a slight glare in the yellow glow. “Again,” she whispered softly. “Again … now, look me in the eyes.” Soren looked into the yellow light.

“Thank you, Auntie.”

“Yes, dear. I’m just an old broody. Love being called Auntie.”

Soren did not know what a broody was, but he took the mouse meat and followed the owl who had been in front of him into the glaucidium. Two large, ragged brown owls escorted the entire group. The glaucidium was a deep box canyon, the floor of which was covered with sleeping owlets. Moonlight streamed down directly on them, silvering their feathers.

“Fall in, you two!” barked a voice from high up in a rocky crevice.

“You!” A plump owl stepped up to Soren. Indeed, Soren’s heart quickened at first for it was another Barn Owl just like his own family. There was the white heart-shaped face and the familiar dark eyes. And yet, although the colour of these eyes was identical to his own and those of his family, he found the owl’s gaze frightening.

“Back row, and prepare to assume the sleeping position.” These instructions were delivered in the throaty rasp common to Barn Owls, but Soren found nothing comforting in the familiar.

The two owls who had escorted the newly arrived orphans spoke to them next. They were Long Eared Owls and had tufts that poked straight up over their eyes and twitched. Soren found this especially unnerving. They each alternated speaking in short deep whoos. The whoos were even more disturbing than the barks of Skench earlier, for the sound seemed to coil into Soren’s very breast and thrum with a terrible clang.

“I am Jatt,” said the first owl. “I was once a number. But now I have earned my new name.”

“Whhh—” Soren snapped off the word.

“I see a question forming on your disgusting beak, number 12-1!” The whoo thrummed so deep within Soren’s breast that he thought his heart might burst.

“Let me make this perrr-fectly clear.” The thrumming of the owl’s sound was almost unbearable. “At St Aggie’s words beginning with the whh sound are not to be spoken. Such words are question words, a habit of mental luxury and indulgence. Questions might fatten the imagination, but they starve the owlish instincts of hardiness, patience, humility and self-denial. We are not here to pamper you by allowing an orgy of wwwhh words, question words. They are dirty words, swear words punishable by the most severe means at our disposal.” Jatt blinked and cast his gaze on Soren’s wings. “We are here to make true owls out of you. And someday you will thank us for it.”

Soren thought he was going to faint with fear. These owls were so different from Finny. Auntie! He silently corrected himself. Jatt had resumed speaking in his normal whoo. “Now my brother shall address you.”

It was an identical voice. “I am Jutt. I too was once a number but have earned my new name. You are now in the sleeping position. Standing tall, head up, beak tipped to the moon. You see in this glaucidium hundreds of owlets. They have all learned to sleep in this manner. You too shall learn.”

Soren looked around, desperately searching for Gylfie, but all he saw was Hortense, or number 12-8. She had assumed the perfect sleeping position. He could tell by the stillness of her head that she was sound asleep under the glare of a full moon. Soren spotted a stone arch that connected to what he thought was another glaucidium. A mass of owls seemed to be marching. Their beaks were bobbing open and shut but Soren could not hear what they were saying.

Jatt now spoke again. “It is strictly forbidden to sleep with the head tucked under the wings, dipped towards the breast, or in the manner that many of you young owls are accustomed, which is the semi-twist position in which the head rests on the back.” Soren felt at least seven wh sounds die mutely in his throat. “Incorrect sleeping posture is also punishable, using our most severe methods.”

“Sleep correction monitors patrol the glaucidium, making their rounds at regular intervals,” Jutt continued.

Now it was Jatt’s turn again. Their timing seemed perfect. Soren felt they had given this speech many times. “Also, at regular intervals, you shall hear the alarm. At the sound, all owlets in the glaucidium are required to begin the sleep march.”

“During the sleep march,” Jutt resumed, “you march, repeating your old name over and over and over again. When the second alarm sounds, you halt where you are. Repeat your number designation one time, and one time only, and assume the sleep position once more.”

Both owls next spoke at once in an awesome thrum. “Now, sleep!”

Soren tried to sleep. He really did try. Maybe Finny, he meant Auntie, would believe him. But there was just something in his gizzard, a little twinge, that seemed to make sleep impossible. It was almost as if the shine of the full moon that sprayed its light over half the glaucidium became a sharp silver needle stabbing through his skull and going straight to his gizzard. Perhaps he had a very sensitive gizzard like his da. But in this case he wasn’t “tasting” the sweet grass the meadow mouse had feasted on. He was tasting dread.

Soren was not sure how long it was before the alarm sounded but it was soon time for his first sleep march. Repeating his name over and over, he followed the owls in his group and now moved into the shadow under the overhang of the arch. “Ah,” Soren sighed. The stabbing feeling in his skull ceased. His gizzard grew still. And Soren became more alert, the proper state for an owl who lived in the night. He looked about him. The little Spotted Owl named Hortense stood next to him. “Hortense?” Soren said. She stared at him blankly and began tapping her feet as if to move.

A sleep monitor swooped down. “Whatcha marching in place for, 12-8? Assume the sleeping position.”

Hortense immediately tipped her beak up, her head slightly back, but there was no moon to shine down upon it in the shadow of the rock. Soren, also in the sleep position, slid his eyes towards her. Curious, he thought. She responded to her number name but not her old name, except to move her feet. Still unable to sleep in this newfangled position, Soren twisted his head about to survey the stone arch. Through the other side of the arch, he caught sight of Gylfie, but too late. The alarm sounded, a high, piercing shriek. Before he knew it, he was being pushed along as thousands of owls began to move. Within seconds, there was an indescribable babble as each owl repeated its old name over and over again.

It became clear to Soren that they were following the path of the moon around the glaucidium. There were, however, so many owls that they could not all be herded under the full shine of the moon at the same time. Therefore, some were allowed an interval under the overhang of the rock arch. Perhaps he and Gylfie, since they had ended up before at the arch at the same time, could meet there again. He was determined to get close to Gylfie the next time.

But that would take three more times. Three more times of blathering his name into the moonlit night. Three more times of feeling the terrible twinge in his gizzard. “12-1, tip that beak up!” It was a sleep monitor. He felt a thwack to the side of his head. Hortense was still next to him. She mumbled, “12-8, what a lovely name that is. 12-8, perfect name. I love twos and fours and eights. So smooth.”

“Hortense,” Soren whispered softly. Her talons might have just vaguely begun to stir on the floor, but other than that, nothing. “Hort! Horty!” He tried, but the little Spotted Owl was lost in some dreamless sleep.

Finally, Soren was back under the arch and quickly moved over to the other side, which connected to the neighbouring glaucidium. The sleep monitors had just barked out the command, “Now, sleep!”

Suddenly, Gylfie was there. The tiny Elf Owl swung her head towards Soren. “They’re moon blinking us,” she whispered.

CHAPTER FIVE (#ulink_bdd1e9f2-18ab-53ef-9657-5afb721f8e25)

Moon Blinking (#ulink_bdd1e9f2-18ab-53ef-9657-5afb721f8e25)

“What?” It felt so good to say a whh sound that Soren almost missed the answer.

“Didn’t your parents tell you about the dangers of sleeping under the full shine?”

“What is ‘full shine’?” Soren asked.

“When did you hatch out?”

“Three weeks ago, I think. Or so my parents told me.” But again, Soren was not really sure what a week was.

“Ah, that explains it. And in Tyto there are great trees, right?” Gylfie asked.

“Oh, yes. Many, and thick with beautiful fir needles and spruce cones and leaves that turn golden and red.” Again, Soren wasn’t sure about leaves turning for he had never seen them anything but golden and red. But his parents had told him that once they were green in a time called summer. Kludd had hatched out near the end of the green time.

“Well, you see, I hatched out more than three weeks ago.” They spoke softly, so softly, and managed to maintain the sleep position, but neither one of them was the least bit sleepy. “I was hatched after the time of newing.”

“The newing? When is that?” asked Soren.

“You see, the moon comes and the moon goes and at the time of the newing, when the moon is no thicker than one single thin, downy feather, well, that is the first glint of the new moon. Then, every day it grows thicker and fatter until there is full shine, like now. And it might stay that way for three or four days. Then comes the time of the dwenking. Instead of growing thicker and fatter, the moon dwenks and becomes thinner, until once more it is no thicker than the thinnest strand of down. And then it disappears for a while.”

“I never saw this. At least, I don’t think I have.”

“Oh, it was there but you probably didn’t really see because your family’s nest was in the hollow of a great tree in a thick forest. But Elf Owls like myself live in deserts. Not so many trees. And many of them are not very leafy. We can see the whole sky nearly all the time.”

“My!” Soren sighed softly.

“And that is why they teach all of us Elf Owls about full shine. Although most owls sleep during the day, sometimes, especially after a hunting expedition, one might be tired and sleep at night. This can be very dangerous if one sleeps out bald in the light of a full moon. It confuses one’s head.”

“How?” Soren asked.

“I’m not sure. My parents never really explained it but they did say that the old owl Rocmore had gone crazy from too much full shine.” Gylfie paused, then hesitating, went on. “They even said that he often did not know which was up and which was down and that finally he died of a broken neck when he thought he was lifting off from the top of a cactus.” Gylfie’s voice almost broke here. “He thought he was flying towards the stars and he slammed into the earth. That’s what moon blinking is all about. You no longer know what is for sure and what is not. What is truth and what are lies. What is real and what is false. That is being moon blinked.”

Soren gasped. “This is awful! Is this what is going to happen to us?”

“Not if we can help it, Soren.”

“What can we do?”

“I’m not sure. Let me think a while. Meanwhile, try to cock your head just a bit, so the moon does not shine straight down on it. And remember, when flying in full shine there is no problem. But sleeping in it is disastrous.”

“I can’t fly yet,” Soren said softly.

“Well, just be sure you don’t sleep.”

Soren cocked his head and while doing so tipped his beak down to look upon the little Elf Owl. How, he wondered, was such a tiny creature so smart? He hoped with all his might that Gylfie would come up with something. Some idea. Just as he was thinking this, there was a sharp bark. “12-1, head straight, beak up!” It was another sleep monitor. He felt a thwack to the side of his head. They did not fall asleep, and as soon as the patrolling owl left, they began whispering again. But then, all too soon, came the inevitable alarm for a sleep march to begin. It would be three more circuits before they could meet again under the arch.

“Remember what I told you. Don’t sleep.”

“I’m so tired. How can I help it?”

“Think of anything.”

“What?”

“Anything—” Gylfie hesitated before a sleep monitor shoved her along. “Think of flying!”

Flying, yes, thinking of flying would keep Soren awake. There was nothing more exciting. But in the meantime, all thoughts of flight were drowned out by the sound of his own voice repeating his own name.

“Soren … Soren … Soren … Soren …” There was also the sound of thousands of talons clicking on the hard stone surface as they marched in lines. Soren was between Hortense and a Horned Owl whose name blended into the drone of other names. Three Snowy Owls were directly in front of him. There were perhaps twenty or more owls to each group, all arranged in loose lines, but they moved in unison as one block of owls, each owl endlessly repeating his or her name. It was impossible to sort out an individual name from the babble and it was not long before, on the fourth sleep march, his own name began to sound odd to Soren. Within another one hundred or so times of repeating it, it seemed almost as if it was not a name at all. It was merely a noise. And he too was becoming a meaningless creature with no real name, no family, but … but … but maybe a friend?

Finally, they stopped again. And it was in the silence of that moment when they stopped that Soren suddenly realised what was happening. It all made sense, particularly when he thought of what Gylfie had explained to him about moon blinking. This alone would keep him awake until he met up with her again.

“They are moon blinking us with our names, Gylfie,” Soren gasped as he edged in close to the little owl under the stone arch. Only the stars twinkled above. Gylfie understood immediately. A name endlessly repeated became a meaningless sound. It completely lost its individuality, its significance. It would dissolve into nothingness. Soren continued, “Just move your beak or say your number, but don’t say your name. That way it will stay your name.” There would, however, be at least three more nights of full shine and then the fullness would begin to lessen until the moon was completely dwenked.

Gylfie looked at Soren in amazement. This ordinary Barn Owl was in his own way quite extraordinary. This was absolutely brilliant. Gylfie felt more than ever compelled to figure out a solution to sleeping exposed to full shine.

CHAPTER SIX (#ulink_607affe4-a83c-54d7-87d2-1bbc92e412e4)

Separate Pits, One Mind (#ulink_607affe4-a83c-54d7-87d2-1bbc92e412e4)

When Soren and Gylfie parted at the end of that long night, they looked at each other and blinked, trembling with fear. If only they could be together in the same pit, then they could think together, talk and plan. Gylfie had told Soren a little about her pit. She too had a pit guardian who seemed very nice, at least compared to Jatt and Jutt or Skench. Gylfie’s pit guardian was called Unk, short for Uncle and, like Auntie, he tried to arrange special treats for Gylfie – a bit of snake sometimes, often even calling Gylfie by her real name and not her number, 25-2. Indeed, when Gylfie had told Soren how her pit guardian had asked her to call him “Unk” it was almost identical to the way in which Aunt Finny had insisted on Soren calling her “Auntie”.

“It was all so weird,” Gylfie had said. “I called him sir at first, and then he said, ‘Sir! All this formality. Really, now! Remember what I asked you to call me? ‘Uncle,’ I answered. ‘Now … now … I gave you my special name’.”

The special name was Unk and the way in which Gylfie described Unk drawing that term of endearment from her, well, Soren could just imagine the Great Horned Owl dipping low to be on eye level with the little Elf Owl, the huge tufts above his ears nearly scraping the ground.

“The pit guardians go out of their way to be nice to us,” Soren had said. “But it’s still kind of scary, isn’t it?”

“Very!” Gylfie had replied. “It was after I called him Unk that he gave me the bits of snake.” She had then sighed. “I remember so well, as if it was yesterday, my First Snake ceremony. Dad had saved the rattles for me and my sisters to play with. And you know what, Soren? It was as if Unk had read my mind because I was thinking about my ceremony and just then he says, ‘I might even have some rattles for you to play with.’ And then I thanked him. I over-thanked him. It was disgusting, Soren.”

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/kathryn-lasky-2/the-capture/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Кэтрин Ласки

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Природа и животные

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Introducing the newest heroes to children′s fiction; the owls of Ga′Hoole. Meet Soren and his friends, the owls charged with keeping owldom safe. Based on Katherine Lasky′s work with owls, this adventures series is bound to be a hit with kids. Join the heroic owls in the first of a series of mythic adventures.Out of the darkness a hero will rise…Soren the enthusiastic and young owl is busy learning the rituals of being a barn owl– First Meat Ceremony, how to fly and of course, about the legendary Guardians of Ga′Hoole. However, his life is quickly transformed when he abruptly falls from his parent′s cosy nest to the bare and dangerous forest floor.Helpless, he is captured by evil chick snatching owls that bring him to St. Aegolius Academy for Orphaned Owls, where his identify disappears as he receives a number instead of a name.Soren quickly befriends another young owl Gylfie, with whom he works to withstand «moon blinking» (brainwashing), and instead develops plans to escape.But before long, Soren realizes that he in fact has already embarked on an extraordinary adventure with much more excitement in the future.