The Carrie Diaries

Candace Bushnell

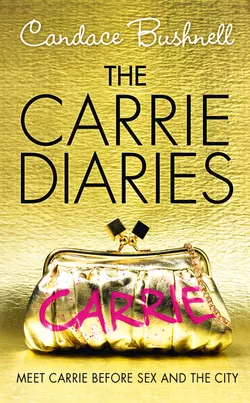

Meet Carrie Bradshaw before ‘Sex and the City!’The Carrie Diaries is the coming-of-age story of one of the most iconic characters of our generation.Before Sex and the City, Carrie Bradshaw was a small town girl who knew she wanted more. She's ready for real life to start, but first she must navigate her senior year of high school. Up until now, Carrie and her friends have been inseparable. Then Sebastian Kydd comes into the picture, and a friend's betrayal makes her question everything.With an unforgettable cast of characters, The Carrie Diaries is the story of how a regular girl learns to think for herself, and evolves into a sharp, insightful writer. Readers will learn about her family background, how she found her writing voice, and the indelible impression her early friendships and relationships left on her. Through adventures both audacious and poignant, we'll see what brings Carrie to her beloved New York City, where her new life begins.

The Carrie Diaries

Candace Bushnell

For Calvin Bushnell

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#uf6f38090-376c-5fed-8a24-0f9a066f2c75)

Title Page (#u2497194b-d8a7-57f1-ae16-6fb62f379b1d)

Dedication (#u95a36e30-2b89-507b-9c7c-10af009c5e7e)

CHAPTER ONE A Princess on Another Planet (#u3dd3c681-c227-5f05-8383-1260644189e6)

CHAPTER TWO The Integer Crowd (#u1c87ccf6-0262-580a-93a8-afab2e75638e)

CHAPTER THREE Double Jeopardy (#u2bed7afd-48dd-55c2-9b63-d8140e386c41)

CHAPTER FOUR The Big Love (#uceff14d2-2fc3-520c-8a7e-ea8b2c763437)

CHAPTER FIVE Rock Lobsters (#uf7a1a1b2-ba93-5f09-a172-146011403d60)

CHAPTER SIX Bad Chemistry (#u61201c44-26d9-59c1-8c8b-fc09a7f29d65)

CHAPTER SEVEN Paint the Town Red (#u88cb53e3-c4c8-515e-b0ee-d137c06ee5a0)

CHAPTER EIGHT The Mysteries of Romance (#u32c3c5d4-ceaf-584f-9be9-e265a8675da3)

CHAPTER NINE The Artful Dodger (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TEN Rescue Me (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ELEVEN Competition (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWELVE You Can’t Always Get What You Want (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTEEN Creatures of Love (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FOURTEEN Hang in There (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FIFTEEN Little Criminals (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SIXTEEN How Far Will You Go? (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN Bait and Switch (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN Cliques Are Made to Be Broken (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER NINETEEN Ch-ch-ch-changes (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY Slippery Slopes (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE The Wall (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO Dancing Fools (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE The Assumption of X (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR The Circus Comes to Town (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE Lockdown at Bralcatraz (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX The S-H-I-T Hits the Fan (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN The Girl Who… (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT Pretty Pictures (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE The Gorgon (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTY Accidents Will Happen (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE Pinky Takes Castlebury (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO The Nerd Prince (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE Hold On to Your Panties (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR Transformation (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE A Free Man in Paris (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE A Princess on Another Planet (#ulink_0e617c4a-b6e5-5f5a-a938-cdb36449e1d9)

They say a lot can happen in a summer.

Or not.

It’s the first day of senior year, and as far as I can tell, I’m exactly the same as I was last year.

And so is my best friend, Lali.

“Don’t forget, Bradley, we have to get boyfriends this year,” she says, starting the engine of the red pickup truck she inherited from one of her older brothers.

“Crap.” We were supposed to get boyfriends last year and we didn’t. I open the door and scoot in, sliding the letter into my biology book, where, I figure, it can do no more harm. “Can’t we give this whole boyfriend thing a rest? We already know all the boys in our school. And—”

“Actually, we don’t,” Lali says as she slides the gear stick into reverse, glancing over her shoulder. Of all my friends, Lali is the best driver. Her father is a cop and insisted she learn to drive when she was twelve, in case of an emergency.

“I hear there’s a new kid,” she says.

“So?” The last new kid who came to our school turned out to be a stoner who never changed his overalls.

“Jen P says he’s cute. Really cute.”

“Uh-huh.”Jen P was the head of Leif Garrett’s fan club in sixth grade. “If he actually is cute, Donna LaDonna will get him.”

“He has a weird name,” Lali says. “Sebastian something. Sebastian Little?”

“Sebastian Kydd?” I gasp.

“That’s it,” she says, pulling into the parking lot of the high school. She looks at me suspiciously. “Do you know him?”

I hesitate, my fingers grasping the door handle.

My heart pounds in my throat; if I open my mouth, I’m afraid it will jump out.

I shake my head.

We’re through the main door of the high school when Lali spots my boots. They’re white patent leather and there’s a crack on one of the toes, but they’re genuine go-go boots from the early seventies. I figure the boots have had a much more interesting life than I have. “Bradley,” she says, eyeing the boots with disdain. “As your best friend, I cannot allow you to wear those boots on the first day of senior year.”

“Too late,” I say gaily. “Besides, someone’s got to shake things up around here.”

“Don’t go changing.” Lali makes her hand into a gun shape, kisses the tip of her finger, and points it at me before heading for her locker.

“Good luck, [A-Z]ngel,” I say. Changing. Ha. Not much chance of that. Not after the letter.

Dear Ms. Bradshaw, it read.

Thank you for your application to the New School’s Advanced Summer Writing Seminar. While your stories show promise and imagination, we regret to inform you that we are unable to offer you a place in the program at this time.

I got the letter last Tuesday. I reread it about fifteen times, just to be sure, and then I had to lie down. Not that I think I’m so talented or anything, but for once in my life, I was hoping I was.

I didn’t tell anyone about it, though. I didn’t even tell anyone I’d applied, including my father. He went to Brown and expects me to go there, too. He thinks I’d make a good scientist. And if I can’t hack molecular structures, I can always go into biology and study bugs.

I’m halfway down the hall when I spot Cynthia Viande and Tommy Brewster, Castlebury’s golden Pod couple. Tommy isn’t too bright, but he is the center on the basketball team. Cynthia, on the other hand, is senior class president, head of the prom committee, an outstanding member of the National Honor Society, and got all the Girl Scout badges by the time she was ten. She and Tommy have been dating for three years. I try not to give them much thought, but alphabetically, my last name comes right before Tommy’s, so I’m stuck with the locker next to his and stuck sitting next to him in assembly, and therefore basically stuck seeing him—and Cynthia—every day.

“And don’t make those goofy faces during assembly,” Cynthia scolds. “This is a very important day for me. And don’t forget about Daddy’s dinner on Saturday.”

“What about my party?” Tommy protests.

“You can have the party on Friday night,” Cynthia snaps.

There could be an actual person inside Cynthia, but if there is, I’ve never seen it.

I swing open my locker. Cynthia suddenly looks up and spots me. Tommy gives me a blank stare, as if he has no idea who I am, but Cynthia is too well brought up for that. “Hello, Carrie,” she says, like she’s thirty years old instead of seventeen.

Changing. It’s hard to pull off in this little town.

“Welcome to hell school,” a voice behind me says.

It’s Walt. He’s the boyfriend of one of my other best friends, Maggie. Walt and Maggie have been dating for two years, and the three of us do practically everything together. Which sounds kind of weird, but Walt is like one of the girls.

“Walt,” Cynthia says. “You’re just the man I want to see.”

“If you want me to be on the prom committee, the answer is no.”

Cynthia ignores Walt’s little joke. “It’s about Sebastian Kydd. Is he really coming back to Castlebury?”

Not again. My nerve endings light up like a Christmas tree.

“That’s what Doreen says.” Walt shrugs as if he couldn’t care less. Doreen is Walt’s mother and a guidance counselor at Castlebury High. She claims to know everything, and passes all her information on to Walt—the good, the bad, and the completely untrue.

“I heard he was kicked out of private school for dealing drugs,” Cynthia says. “I need to know if we’re going to have a problem on our hands.”

“I have no idea,” Walt says, giving her an enormous fake smile. Walt finds Cynthia and Tommy nearly as annoying as I do.

“What kind of drugs?” I ask casually as we walk away.

“Painkillers?”

“Like in Valley of the Dolls?” It’s my favorite secret book, along with the DSM-III, which is this tiny manual about mental disorders. “Where the hell do you get painkillers these days?”

“Oh, Carrie, I don’t know,”Walt says, no longer interested. “His mother?”

“Not likely.” I try to squeeze the memory of my one-and-only encounter with Sebastian Kydd out of my head but it sneaks in anyway.

I was twelve and starting to go through an awkward stage. I had skinny legs and no chest, two pimples, and frizzy hair. I was also wearing cat’s-eye glasses and carrying a dog-eared copy of What About Me? by Mary Gordon Howard. I was obsessed with feminism. My mother was remodeling the Kydds’ kitchen, and we’d stopped by their house to check on the project. Suddenly, Sebastian appeared in the doorway. And for no reason, and completely out of the blue, I sputtered, “Mary Gordon Howard believes that most forms of sexual intercourse can be classified as rape.”

For a moment, there was silence. Mrs. Kydd smiled. It was the end of the summer, and her tan was set off by her pink and green shorts in a swirly design. She wore white eye shadow and pink lipstick. My mother always said Mrs. Kydd was considered a great beauty. “Hopefully you’ll feel differently about it once you’re married.”

“Oh, I don’t plan to get married. It’s a legalized form of prostitution.”

“Oh my.” Mrs. Kydd laughed, and Sebastian, who had paused on the patio on his way out, said, “I’m taking off.”

“Again, Sebastian?” Mrs. Kydd exclaimed with a hint of annoyance. “But the Bradshaws just got here.”

Sebastian shrugged.“Going over to Bobby’s to play drums.”

I stared after him in silence, my mouth agape. Clearly Mary Gordon Howard had never met a Sebastian Kydd.

It was love at first sight.

In assembly, I take my seat next to Tommy Brewster, who is hitting the kid in front of him with a notebook. A girl in the aisle is asking if anyone has a tampon, while two girls behind me are excitedly whispering about Sebastian Kydd, who seems to become more and more notorious each time his name is mentioned.

“I heard he went to jail—”

“His family lost all their money—”

“No girl has managed to hold on to him for more than three weeks—”

I force Sebastian Kydd out of my thoughts by pretending Cynthia Viande is not a fellow student but a strange species of bird. Habitat: any stage that will have her. Plumage: tweed skirt, white shirt with cashmere sweater, sensible shoes, and a string of pearls that is probably real. She keeps shifting her papers from one arm to the other and tugging down her skirt, so maybe she’s a little nervous after all. I know I would be. I wouldn’t want to be, but I would. My hands would be shaking and my voice would come out in a squeak, and afterward, I’d hate myself for not taking control of the situation.

The principal, Mr. Jordan, goes up to the mike and says a bunch of boring stuff about being on time for classes and something about a new system of demerits, and then Ms. Smidgens informs us that the school newspaper, The Nutmeg, is looking for reporters and how there’s some earthshaking story about cafeteria food in this week’s issue. And finally, Cynthia walks up to the mike. “This is the most important year of our lives. We are poised at the edge of a very great precipice. In nine months, our lives will be irreparably altered,” she says, like she thinks she’s Winston Churchill or something. I’m half expecting her to add that all we have to fear is fear itself, but instead, she continues: “So this year is all about senior moments. Moments we’ll remember forever.”

Suddenly Cynthia’s expression changes to one of annoyance as everyone’s head starts swiveling toward the center of the auditorium.

Donna LaDonna is coming down the aisle. She’s dressed like a bride, in a white dress with a deep V, her ample cleavage accentuated by a tiny diamond cross hanging from a delicate platinum chain. Her skin is like alabaster; on one wrist, a constellation of silver bracelets peal like bells when she moves her arm. The auditorium falls silent.

Cynthia Viande leans into the mike. “Hello, Donna. So glad you could make it.”

“Thanks,” Donna says, and sits down.

Everyone laughs.

Donna nods at Cynthia and gives her a little wave, as if signaling her to continue. Donna and Cynthia are friends in that weird way that girls are when they belong to the same clique but don’t really like each other.

“As I was saying,” Cynthia begins again, trying to recapture the crowd’s attention, “this year is all about senior moments. Moments we’ll remember forever.” She points to an AV guy, and the song “The Way We Were” comes over the loudspeaker.

I groan and bury my face in my notebook. I start to giggle along with everyone else, but then I remember the letter and get depressed again.

But every time I feel bad, I try to remind myself about what this little kid said to me once. She was loaded with personality—so ugly she was cute. And you knew she knew it too. “Carrie?” she asked. “What if I’m a princess on another planet? And no one on this planet knows it?”

That question still kind of blows me away. I mean, isn’t it the truth? Whoever we are here, we might be princesses somewhere else. Or writers. Or scientists. Or presidents. Or whatever the hell we want to be that everyone else says we can’t.

CHAPTER TWO The Integer Crowd (#ulink_b3ef8d01-6701-5516-94b4-0112222bb8c7)

“Who knows the difference between integral calculus and differential calculus?”

Andrew Zion raises his hand. “Doesn’t it have something to do with how you use the differentials?”

“That’s getting there,” Mr. Douglas, the teacher, says. “Anyone else have a theory?”

The Mouse raises her hand. “In differential calculus you take an infinitesimal small point and calculate the rate of change from one variable to another. In integral calculus you take a small differential element and you integrate it from one lower limit to another limit. So you sum up all those infinitesimal small points into one large amount.”

Jeez, I think. How the hell does The Mouse know that?

I’m never going to be able to get through this course. It will be the first time math has failed me. Ever since I was a kid, math was one of my easiest subjects. I’d do the homework and ace the tests, and hardly have to study. But I’ll have to study now, if I plan to survive.

I’m sitting there wondering how I can get out of this course, when there’s a knock on the door. Sebastian Kydd walks in, wearing an ancient navy blue polo shirt. His eyes are hazel with long lashes, and his hair is bleached dark blond from seawater and sun. His nose, slightly crooked, as if he was punched in a fight and never had it fixed, is the only thing that saves him from being too pretty.

“Ah, Mr. Kydd. I was wondering when you were planning to show up,” Mr. Douglas says.

Sebastian looks him straight in the eye, unfazed. “I had a few things I needed to take care of first.”

I sneak a glance at him from behind my hand. Here is someone who truly does come from another planet—a planet where all humans are perfectly formed and have amazing hair.

“Please. Sit down.”

Sebastian looks around the room, his glance pausing on me. He takes in my white go-go boots, slides his eyes up my light blue tartan skirt and sleeveless turtleneck, up to my face, which is now on fire. One corner of his mouth lifts in amusement, then pulls back in confusion before coming to rest on indifference. He takes a seat in the back of the room.

“Carrie,” Mr. Douglas says. “Can you give me the basic equation for movement?”

Thank God we learned that equation last year. I rattle it off like a robot: “X to the fifth degree times Y to the tenth degree minus a random integer usually known as N.”

“Right,” Mr. Douglas says. He scribbles another equation on the board, steps back, and looks directly at Sebastian.

I put my hand on my chest to keep it from thumping.

“Mr. Kydd?” he asks. “Can you tell me what this equation represents?”

I give up being coy. I turn around and stare.

Sebastian leans back in his chair and taps his pen on his calculus book. His smile is tense, as if he either doesn’t know the answer, or does know it and can’t believe anyone would be so stupid as to ask. “It represents infinity, sir. But not any old infinity. The kind of infinity you find in a black hole.”

He catches my eye and winks.

Wow. Black hole indeed.

“Sebastian Kydd is in my calculus class,” I hiss to Walt, cutting behind him in the cafeteria line.

“Christ, Carrie,”Walt says. “Not you, too. Every single girl in this school is talking about Sebastian Kydd. Including Maggie.”

The hot meal is pizza—the same pizza our school system has been serving for years, which tastes like barf and must be the result of some secret school-system recipe. I pick up a tray, then an apple and a piece of lemon meringue pie.

“But Maggie is dating you.”

“Try telling Maggie that.”

We carry our trays to our usual table. The Pod People sit at the opposite end of the cafeteria, near the vending machines. Being seniors, we should have claimed a table next to them. But Walt and I decided a long time ago that high school was disturbingly like India—a perfect example of a caste system—and we vowed not to participate by never changing our table. Unfortunately, like most protests against the overwhelming tide of human nature, ours goes largely unnoticed.

The Mouse joins us, and she and Walt start talking about Latin, a subject in which they’re both better than I am. Then Maggie comes over. Maggie and The Mouse are friendly, but The Mouse says she would never want to get too close to Maggie because she’s overly emotional. I say that excessive emotionality is interesting and distracts one from one’s own problems. Sure enough, Maggie is on the verge of tears.

“I just got called into the counselor’s office—again. She said my sweater was too revealing!”

“That’s outrageous,” I say.

“Tell me about it,” Maggie says, squeezing in between Walt and The Mouse. “She really has it out for me. I told her there was no dress code and she didn’t have the right to tell me what to wear.”

The Mouse catches my eye and snickers. She’s probably remembering the same thing I am—the time Maggie got sent home from Girl Scouts for wearing a uniform that was too short. Okay, that was about seven years ago, but when you’ve lived in the same small town forever, you remember these things.

“And what did she say?” I ask.

“She said she wouldn’t send me home this time, but if she sees me in this sweater again, she’s going to suspend me.”

Walt shrugs. “She’s a bitch.”

“How can she discriminate against a sweater?”

“Perhaps we should lodge a complaint with the school board. Have her fired,” The Mouse says.

I’m sure she doesn’t mean to sound sarcastic, but she does, a little. Maggie bursts into tears and runs in the direction of the girls’ room.

Walt looks around the table. “Which one of you bitches wants to go after her?”

“Was it something I said?” The Mouse asks innocently.

“No.” Walt sighs. “There’s a crisis every other day.”

“I’ll go.” I take a bite of my apple and hurry after her, pushing through the cafeteria doors with a bang.

I run smack into Sebastian Kydd.

“Whoa,” he exclaims. “Where’s the fire?”

“Sorry,” I mumble. I’m suddenly hurtled back in time, to when I was twelve.

“This is the cafeteria?” he asks, gesturing toward the swinging doors. He peeks in the little window. “Looks heinous. Is there any place to eat off campus?”

Off-campus? Since when did Castlebury High become a campus? And is he asking me to have lunch with him? No, not possible. Not me. But maybe he doesn’t remember that we’ve met before.

“There’s a hamburger place up the street. But you need a car to get there.”

“I’ve got a car,” he says.

And then we just stand there, staring at each other. I can feel the other kids walking by but I don’t see them.

“Okay. Thanks,” he says.

“Right.” I nod, remembering Maggie.

“See ya,” he says, and walks away.

Rule number one: Why is it that the one time a cute guy talks to you, you have a friend who’s in crisis?

I run into the girls’ room. “Maggie? You won’t believe what just happened.” I look under the stalls and spot Maggie’s shoes next to the wall. “Mags?”

“I am totally humiliated,” she wails.

Rule number two: Humiliated best friend always takes precedence over cute guy.

“Magwitch, you can’t let what other people say affect you so much.” I know this isn’t helpful, but my father says it all the time and it’s the only thing I can think of at the moment.

“How am I supposed to do that?”

“By looking at everyone like they’re a big joke. Come on, Mags. You know high school is absurd. In less than a year we’ll be out of here and we’ll never have to see any of these people ever again.”

“I need a cigarette,” Maggie groans.

The door opens and the two Jens come in.

Jen S and Jen P are cheerleaders and part of the Pod clique. Jen S has straight dark hair and looks like a beautiful little dumpling. Jen P used to be my best friend in third grade. She was kind of okay, until she got to high school and took up social climbing. She spent two years taking gymnastics so she could become a cheerleader, and even dated Tommy Brewster’s best friend, who has teeth the size of a horse. I waver between feeling sorry for her and admiring her desperate determination. Last year, her efforts paid off and she was finally admitted to the Pod pack, which means she now rarely talks to me.

For some reason, she does today, because when she sees me, she exclaims, “Hi!” as if we’re still really good friends.

“Hi!” I reply, with equally false enthusiasm.

Jen S nods at me as the two Jens begin taking lipsticks and eye shadows out of their bags. I once overheard Jen S telling another girl that if you want to get guys, you have to have “a trademark”—one thing you always wore to make you memorable. For Jen S, this, apparently, is a thick stripe of navy blue eyeliner on her upper lid. Go figure. She leans in to the mirror to make sure the eyeliner is still intact as Jen P turns to me.

“Guess who’s back at Castlebury High?” she asks.

“Who?”

“Sebastian Kydd.”

“Re-e-e-ally?” I look in the mirror and rub my eye, pretending I have something in it.

“I want to date him,” she says, with complete and utter confidence. “From what I’ve heard, he’d be a perfect boyfriend for me.”

“Why would you want to date someone you don’t know?”

“I just do, that’s all. I don’t need a reason.”

“Cutest boys in the history of Castlebury High,” Jen S says, as if leading a cheer.

“Jimmy Watkins.”

“Randy Sandler.”

“Bobby Martin.”

Jimmy Watkins, Randy Sandler, and Bobby Martin were on the football team when we were sophomores. They all graduated at least two years ago. Who cares? I want to shout.

“Sebastian Kydd,” Jen S exclaims.

“Hall of Famer for sure. Right, Carrie?”

“Who?” I ask, just to annoy her.

“Sebastian Kydd,”Jen P says in a huff as she and Jen S exit.

“Maggie?” I ask. She hates the two Jens and won’t come out until they’ve left the bathroom. “They’re gone.”

“Thank God.” The stall door opens and Maggie heads for the mirror. She runs a comb through her hair. “I can’t believe Jen P thinks she can get Sebastian Kydd. That girl has no sense of reality. Now, what were you going to tell me?”

“Nothing,” I say, suddenly sick of Sebastian. If I hear one more person mention his name, I’m going to shoot myself.

“What was that business with Sebastian Kydd?”The Mouse asks a little later. We’re in the library, attempting to study.

“What business?” I highlight an equation in yellow, thinking about how useless it is to highlight. It makes you think you’re learning, but all you’re really learning is how to use a highlighter.

“He winked at you. In calculus class.”

“He did?”

“Bradley,” The Mouse says, in disbelief. “Don’t even try to tell me you didn’t notice.”

“How do I know he was winking at me? Maybe he was winking at the wall.”

“How do we know infinity exists? It’s all a theory. And I think you should go out with him,” she insists. “He’s cute and he’s smart. He’d be a good boyfriend.”

“That’s what every girl in the school thinks. Including Jen P.”

“So what? You’re cute and you’re smart, too. Why shouldn’t you date him?”

Rule number three: Best friends always think you deserve the best guy even if the best guy barely knows you exist.

“Because he probably only likes cheerleaders?”

“Faulty reasoning, Bradley. You don’t know that for a fact.” And then she gets all dreamy and rests her chin in her hand. “Guys can be full of surprises.”

This dreaminess is not like The Mouse. She has plenty of guy friends, but she’s always been too practical to get romantically involved.

“What does that mean?” I ask, curious about this new Mouse. “Have you encountered some surprising guys recently?”

“Just one,” she says.

And rule number four: Best friends can also be full of surprises.

“Bradley.” She pauses. “I have a boyfriend.”

What? I’m so shocked, I can’t speak. The Mouse has never had a boyfriend. She’s never even had a proper date.

“He’s pretty nifty,” she says.

“Nifty? Nifty?” I croak, finding my voice. “Who is he? I need to know all about this nifty character.”

The Mouse giggles, which is also very un-Mouse-like. “I met him this summer. At the camp.”

“Aha.” I’m kind of stunned and a little bit hurt that I haven’t heard about this mysterious Mouse boyfriend before, but now it makes sense. I never see The Mouse during the summer because she always goes to some special government camp in Washington, D.C.

And suddenly, I’m really happy for her. I jump up and hug her, popping up and down like a little kid on Christmas morning. I don’t know why it’s such a big deal. It’s only a stupid boyfriend. But still. “What’s his name?”

“Danny.” Her eyes slide away and she smiles dazedly, as if she’s watching some secret movie inside her head. “He’s from Washington. We smoked pot together and—”

“Wait a minute.” I hold up my hands. “Pot?”

“My sister Carmen told me about it. She says it relaxes you before sex.”

Carmen is three years older than The Mouse and the most proper girl you’ve ever seen. She wears pantyhose in the summer. “What does Carmen have to do with you and Danny? Carmen smokes pot? Carmen has sex?”

“Listen, Bradley. Even smart people get to have sex.”

“Meaning we should be having sex.”

“Speak for yourself.”

Huh? I pull The Mouse’s calculus book away from her and bang it shut. “Listen, Mouse. What are you talking about? Did you have sex?”

“Yup,” she says, nodding, as if it’s no big deal.

“How can you have sex and I haven’t? You’re supposed to be a nerd. You’re supposed to be inventing the cure for cancer, not doing it in the backseat of some car filled with marijuana smoke.”

“We did it in his parents’ basement,” The Mouse says, taking her book back.

“You did?” I try to imagine The Mouse naked on some guy’s cot in a damp basement. I can’t picture it. “How was it?”

“The basement?”

“The sex,” I nearly scream, trying to bring The Mouse back down to earth.

“Oh, that. It was good. Really fun. But it’s the kind of thing you have to work at. You don’t just start doing it. You have to experiment.”

“Really?” I narrow my eyes in suspicion. I’m not sure how to take this news. All summer, while I was writing some stupid story to get into that stupid writing program, The Mouse was losing her virginity. “How did you even figure out how to do it in the first place?”

“I read a book. My sister told me everyone should read an instructional manual before they do it so they know what to expect. Otherwise it might be a big disappointment.”

I squint, adding a sex book to my image of The Mouse and this Danny person getting it on in his parents’ basement. “Do you think you’re going to…continue?”

“Oh, yes,”The Mouse says. “He’s going to Yale, like me.” She smiles and goes back to her calculus book, as if it’s all settled.

“Hmph.” I fold my arms. But I suppose it makes sense. The Mouse is so organized, she would have her romantic life figured out by the time she’s eighteen.

While I have nothing figured out at all.

CHAPTER THREE Double Jeopardy (#ulink_c1bc2376-2290-5eae-a62e-4d6823bec1dd)

“I don’t know how I’m going to get through this year,” Maggie says. She takes out a pack of cigarettes, which she stole from her mother, and lights up.

“Uh-huh,” I say, distracted. I’m still shocked The Mouse is having sex. What if everyone is having sex?

Crap. I absentmindedly pick up a copy of The Nutmeg. The headline screams: yogurt served in cafeteria. I roll my eyes and shove it aside. With the exception of the handful of kids who actually work on The Nutmeg, no one reads it. But someone left it on the old picnic table inside the ancient dairy barn that sits just outside school property. The table’s been here forever, scratched with the initials of lovers, the years of graduating classes, and general sentiments toward Castlebury High, such as “Castlebury sucks.” The teachers never come out here, so it’s also the unofficial smoking area.

“At least we get yogurt this year,” I say, for no particular reason. What if I never have sex? What if I die in a car accident before I have the chance to do it?

“What’s that supposed to mean?” Maggie asks.

Uh-oh. Up next: the dreaded body discussion. Maggie will say she thinks she’s fat, and I’ll say I think I look like a boy. Maggie will say she wishes she looked like me and I’ll say I wish I looked like her. And it won’t make a bit of difference, because two minutes later, we’ll both be sitting here in our same bodies, except we’ll have managed to make ourselves feel bad over something we can’t change.

Like not getting into the damn New School.

What if some guy wants to have sex with me and I’m too scared to go through with it?

Sure enough, Maggie says, “Do I look fat? I do look fat, don’t I? I feel fat.”

“Maggie. You’re not fat.” Guys have been drooling over Maggie since she was thirteen, a fact that she seems determined to ignore.

I look away. Behind her, in the dark recesses at the far end of the barn, the glowing tip of a cigarette moves up and down. “Someone’s in here,” I hiss.

“Who?” She spins around as Peter Arnold comes out of the shadows.

Peter is the second-smartest boy in our class and kind of a jerk. He used to be a chubby-faced short kid with pasty skin, but it appears something happened to Peter over the summer. He grew.

And apparently took up smoking.

Peter is good friends with The Mouse, but I don’t really know him. When it comes to relationships, we’re all like little planets with our own solar system of friends. Unwritten law states that the solar systems rarely intersect—until now.

“Mind if I join you?” he asks.

“Actually, we do. We’re having girl talk here.” I don’t know why I’m like this with boys, especially boys like Peter. Bad habit, I guess. Worse than smoking. But I don’t want boring old Peter to ruin our conversation.

“No. We don’t mind.” Maggie kicks me under the table.

“By the way, I don’t think you’re fat,” Peter says.

I smirk, trying to catch Maggie’s eye, but she’s not looking at me. She’s looking at Peter. So I look at Peter too. His hair is longer and he’s shed most of his zits, but there’s something else about him.

Confidence.

Jeez. First The Mouse and now Peter. Is everyone going to be different this year?

Maggie and Peter keep ignoring me, so I pick up the paper and pretend to read. This gets Peter’s attention.

“What do you think of The Nutmeg?” he asks.

“Drivel,” I say.

“Thanks,” he says. “I’m the editor.”

Nice. Now I’ve done it again.

“If you’re so smart, why don’t you try writing for the paper?” Peter asks. “I mean, don’t you tell everyone you want to be a writer? What have you ever written?”

Maybe he doesn’t mean to sound aggressive, but the question catches me off guard. Does Peter somehow know about the rejection letter from The New School? But that would be impossible. Then I get angry. “What does it matter, what I’ve written or not?”

“If you say you’re a writer, it means you write,” Peter says smugly. “Otherwise you should go and be a cheerleader or something.”

“And you should stick your head in a barrel of boiling oil.”

“Maybe I will.” He laughs good-naturedly. Peter must be one of those obnoxious types who’s so used to being insulted he’s not even offended when he is.

But still, I’m shaken. I grab my swim bag.“I’ve got practice,” I say, as if I can hardly be bothered with this conversation.

“What’s the matter with her?” Peter asks as I storm out.

I head down the hill toward the gym, scuffing the heels of my boots in the grass. Why is it always like this? I tell people I want to be a writer, and they roll their eyes. It drives me crazy. Especially since I’ve been writing since I was six. I have a pretty big imagination, and for a while I wrote stories about a pencil family called “The Number 2’s,” who were always trying to get away from a bad guy called “The Sharpener.” Then I wrote about a little girl who had a mysterious disease that made her look like she was ninety. And this summer, in order to get into that stupid writing program, I wrote a whole book about a boy who turned into a TV, and no one in his family noticed until he used up all the electricity in the house.

If I’d told Peter the truth about what I’d written, he would have laughed. Just like those people at The New School.

“Carrie!” Maggie calls out. She hurries across the playing fields to catch up. “Sorry about Peter. He says he was joking about the writing thing. He has a weird sense of humor.”

“No kidding.”

“Do you want to go to the mall after swim practice?”

I look across the grounds to the high school and the enormous parking lot beyond. It’s all exactly the same as it always was.

“Why not?” I take the letter out of my biology book, crumple it up, and stick it in my pocket.

Who cares about Peter Arnold? Who cares about The New School? Someday I’ll be a writer. Someday, but maybe not today.

“I am so effing sick of this place,” Lali says, dropping her things onto a bench in the locker room.

“You and me both.” I unzip my boots. “First day of swim practice. I hate it.”

I pull one of my old Speedos out of my bag and hang it in the locker. I’ve been swimming since before I could walk. My favorite photo is of me at five months, sitting on a little yellow float in Long Island Sound. I’m wearing a cute white hat and a polka-dot suit, and I’m beaming.

“You’ll be fine,” Lali says. “I’m the one with the problems.”

“Like what?”

“Like Ed,” she says with a grimace, referring to her father.

I nod. Sometimes Ed is more like a kid than a dad, even though he’s a cop. Actually, he’s more than a cop, he’s a detective—the only one in town. Lali and I always laugh about it because we can’t figure out exactly what he detects, as there’s never been a serious crime in Castlebury.

“He stopped by the school,” Lali says, stripping off her clothes. “We had a fight.”

“What’s wrong now?” The Kandesies fight like Mongolians, but they always make up, cracking jokes and doing outrageous things, like waterskiing in their bare feet. For a while, they kind of took me in, and sometimes I’d wish I’d been born a Kandesie instead of a Bradshaw, because then I’d be laughing all the time and listening to rock ‘n’ roll music and playing family baseball on summer evenings. My father would die if he knew, but there it is.

“Ed won’t pay for college.” Lali faces me, naked, her hands on her hips.

“What?”

“He won’t pay,” she repeats. “He told me today. He never went to college and he’s just fine,” she says mockingly. “I have two choices. I can go to military school or I can get a job. He doesn’t give jack shit about what I want.”

“Oh, Lali.” I stare at her in shock. How can this be? There are five kids in Lali’s family, so money has always been tight. But Lali and I assumed she’d go to college—we’d both go, and then we’d do something big with our lives. In the dark, tucked into a sleeping bag on the floor next to Lali’s bunk bed, we’d share our secrets in excited whispers. I was going to be a writer and Lali was going to win the gold medal in freestyle. But now I’ve been rejected from The New School. And Lali can’t even go to college.

“I guess I’m going to be stuck in Castlebury forever,” Lali says furiously. “Maybe I can work at Ann Taylor and earn five dollars an hour. Or maybe I could get a job at the supermarket. Or”—she smacks her hand on her forehead—“I could work at the bank. But I think you need a college degree to be a teller.”

“It’s not going to be like that,” I insist. “Something will happen—”

“What?”

“You’ll get a swimming scholarship—”

“Swimming is not a profession.”

“You could still go to military school. Your brothers—”

“Are both in military school and they hate it,” Lali snaps.

“You can’t let Ed ruin your life,” I say with bravado. “Find something you want to do and just do it. If you really want something, Ed can’t stop you.”

“Right,” Lali says sarcastically. “Now all I need to do is figure out what that ‘something’ is.” She holds out her suit, sliding her legs through the openings. “I’m not like you, okay? I don’t know what I want to do for the rest of my life. I mean, why should I? I’m only seventeen. All I know is that I don’t want someone telling me what I can’t do.”

She turns and makes a grab for her swim cap, accidentally knocking my clothes to the floor. I bend over to pick them up, and as I do, I see that the letter from The New School has slid out of my pocket, coming to rest next to Lali’s foot. “I’ll get that,” I say, making a grab for it, but she’s too fast.

“What’s this?” she asks, holding up the crumpled piece of paper.

“Nothing,” I say helplessly.

“Nothing?” Her eyes widen as she looks at the return address. “Nothing?” she repeats as she smoothes out the letter.

“Lali, please.”

Her eyes move back and forth, scanning the brief missive.

Crap. I knew I should have left the letter at home. I should have torn it up into little pieces and thrown it away. Or burned it, although it’s not that easy to burn a letter, no matter how dramatic it sounds in books. Instead, I keep carrying it around, hoping it will act as some kind of perverse incentive to try harder.

Now I’m paralyzed by what must be my own stupidity.

“Lali, don’t,” I whisper.

“Just a minute,” she says, reading the text one more time. She looks up, shakes her head, and presses her lips together in sympathy. “Carrie. I’m sorry.”

“So am I.” I shrug, trying to make light of it. My insides feel like they’re filled with broken glass.

“I mean it.” She folds the letter and hands it back to me, busying herself with her swim goggles. “Here I am, complaining about Ed. And you’re being rejected by The New School. That’s got to suck.”

“Sort of.”

“Looks like we’re both going to be hanging around here for a while,” she says, putting her arm around my shoulder. “Even if you do go to Brown, it’s only forty-five minutes away. We’ll still see each other all the time.”

She pulls open the door to the pool, enveloping us in a chemical steam of chlorine and cleaning fluid. I consider asking her not to tell anyone about the rejection. But that will only make it worse. If I act like it’s not a big deal, Lali will forget about it.

Sure enough, she flings her towel into the bleachers and runs across the tiles. “Last one in is a rotten egg,” she shouts, doing a cannonball into the water.

CHAPTER FOUR The Big Love (#ulink_35550f00-7fef-5dd2-a0ed-415d6dac28b6)

I return home to bedlam.

A puny kid with a punk haircut is running across the yard, followed by my father, who is followed by my sister Dorrit, who is followed by my other sister Missy. “Don’t ever let me catch you on this property again!” my father shouts as the kid, Paulie Martin, manages to jump on his bike and pedal away.

“What the hell?” I ask Missy.

“Poor Dad.”

“Poor Dorrit,” I say, shifting my books. As if in mockery of my situation, the letter from The New School falls out of my notebook. Enough. I pick it up, march into the garage, and throw it away.

I immediately feel lost without it and fish it out of the trash.

“Did you see that?” my father says proudly. “I just ran that little thug off the property.” He points to Dorrit.“You—get back in the house. And don’t even think about calling him.”

“Paulie’s not that bad, Dad. He’s only a kid,” I say.

“He’s a little S-H-I-T,” says my father, who prides himself on rarely swearing. “He’s a hoodlum. Did you know he was arrested for buying beer?”

“Paulie Martin bought beer?”

“It was in the paper,” my father exclaims. “The Castlebury Citizen. And now he’s trying to corrupt Dorrit.”

Missy and I exchange a look. Knowing Dorrit, the opposite is true.

Dorrit used to be the sweetest little kid. She would go along with anything Missy and I told her to do, including crazy stuff like pretending she and our cat were twins. She was always making things for people—cards and little scrapbooks and crocheted pot holders—and last year, she decided she wanted to be a vet and spent practically all her time after school holding sick animals while they got their shots.

But now she’s nearly thirteen, and lately, she’s become a real problem child, crying and having temper tantrums and yelling at me and Missy. My father keeps insisting she’s in a stage and will grow out of it, but Missy and I aren’t so sure. My father is this very big scientist who came up with a formula for some new kind of metal used in the Apollo space rockets, and Missy and I always joke that if people were theories instead of actual human beings, Dad would know everything about us.

But Dorrit isn’t a theory. And lately, Missy and I have found little things missing from our rooms—an earring here or a tube of lip gloss there—the kinds of things you might easily lose or misplace on your own. Missy was going to confront her, but then we found most of our things stuffed behind the cushions in the couch. Nevertheless, Missy is still convinced that Dorrit is on the path to becoming a little criminal, while I’m worried about her anger. Missy and I were both brats at thirteen, but neither one of us can remember being so pissed off all the time.

True to form, in a couple of minutes Dorrit appears in the doorway of my room, aching for a fight.

“What was Paulie Martin doing here?” I ask. “You know Dad thinks you’re too young to date.”

“I’m in eighth grade,” Dorrit says stubbornly.

“That’s not even high school. You have years to have boyfriends.”

“Everyone else has a boyfriend.” She picks a flake of polish from her nail. “Why shouldn’t I?”

This is why I hope never to become a mother. “Just because everyone else is doing something, it doesn’t mean you should too. Remember,” I add, imitating my father, “we’re Bradshaws. We don’t have to be like everyone else.”

“Maybe I’m sick of being a stupid old Bradshaw. What is so great about being a Bradshaw anyway? If I want to have a boyfriend, I’ll have a boyfriend. You and Missy are just jealous because you don’t have boyfriends.” She glares at me, runs to her room, and slams the door.

I find my father in the den, sipping a gin and tonic and staring at the TV. “What am I supposed to do?” he asks helplessly.“Ground her? When I was a boy, girls didn’t act like this.”

“That was thirty years ago, Dad.”

“Doesn’t matter,” he says, pressing on his temples.“Love is a holy cause.” Once he goes off on one of these spiels, it’s hopeless. “Love is spiritual. It’s about self-sacrifice and commitment. And discipline. You cannot have true love without discipline. And respect. When you lose the respect of your spouse, you’ve lost everything.” He pauses. “Does this make any sense to you?”

“Sure, Dad,” I say, not wanting to hurt his feelings.

A couple of years ago, after my mother died, my sisters and I tried to encourage my father to find someone else, but he refused to entertain the idea. He wouldn’t even go on a date. He said he’d already had the one big love of his life, and anything less would feel like a sham. He felt blessed, he said, to have had that kind of love once in his life, even if it didn’t last forever.

You wouldn’t think a hard-boiled scientist like my father would be such a romantic, but he is.

It worries me sometimes. Not for my father’s sake, but for my own.

I head up to my room, sit down in front of my mother’s old Royale typewriter, and slide in a piece of paper. The Big Love, I write, then add a question mark.

Now what?

I open the drawer and take out a story I wrote a few years ago, when I was thirteen. It was a stupid story about a girl who rescues a sick boy by donating her kidney to him. Before he got sick, he never noticed her, even though she was pining away for him, but after she gives him her kidney, he falls madly in love with her.

It’s a story I would never show anyone, because it’s too sappy, but I’ve never been able to throw it away. It scares me. It makes me worry that I’m secretly a romantic too, just like my father.

And romantics get burned.

Whoa. Where’s the fire?

Jen P was right. You can fall in love with a guy you don’t know.

That summer when I was thirteen, Maggie and I used to hang out at Castlebury Falls. There was a rock cliff where the boys would dive into a deep pool, and sometimes Sebastian was there, showing off, while Maggie and I sat on the other side of the river.

“Go on,” Maggie would urge. “You’re a better diver than those boys.” I’d shake my head, my arms wrapped protectively around my knees. I was too shy. The thought of being seen was terrifying.

I didn’t mind watching, though. I couldn’t take my eyes off Sebastian as he scrambled up the side of the rock, sleek and sure-footed. At the top, there was horseplay between the boys, as they jostled one another and hooted dares, demanding increasing feats of skill. Sebastian was always the bravest, climbing higher than the other boys and launching himself into the water with a fearlessness that told me he had never thought about death.

He was free.

He’s the one. The Big Love.

And then I forgot about him.

Until now.

I find the soiled rejection letter from The New School and put it in the drawer with the story about the girl who gave away her kidney. I rest my chin in my hands and stare at the typewriter.

Something good has to happen to me this year. It just does.

CHAPTER FIVE Rock Lobsters (#ulink_ec3fc46b-2e23-50e1-93c0-298a12e7992e)

“Maggie, get out of the car.”

“I can’t.”

“Please—”

“What’s wrong now?”Walt asks.

“I need a cigarette.”

Maggie, Walt, and I are sitting in Maggie’s car, which is parked in the cul-de-sac at the end of Tommy’s street. We’ve been in the car for at least fifteen minutes, because Maggie is paranoid about crowds and refuses to get out of the car when we go to parties. On the other hand, she does have the best car. It’s a gigantic gas-guzzling Cadillac that fits about nine people and has a quadraphonic stereo and a glove compartment filled with her mother’s cigarettes.

“You’ve smoked three cigarettes already.”

“I don’t feel good,” Maggie moans.

“Maybe you’d feel better if you hadn’t smoked all those cigarettes at once,” I say, wondering if Maggie’s mother notices that every time Maggie gives the car back, about a hundred cigarettes are missing. I did ask Maggie about it once, but she only rolled her eyes and said her mother was so clueless, she wouldn’t notice if a bomb blew up in their house. “Come on,” I coax her. “You know you’re just scared.”

She frowns. “We’re not even invited to this party.”

“We’re not not invited. So that means we’re invited.”

“I can’t stand Tommy Brewster,” she mutters, and crosses her arms.

“Since when do you have to like someone to go to their party?”Walt points out.

Maggie glares and Walt throws up his hands. “I’ve had enough,” he says. “I’m going in.”

“Me too,” I say suddenly. We slide out of the car. Maggie looks at us through the windshield and lights up another cigarette. Then she pointedly locks all four doors.

I make a face. “Do you want me to stay with her?”

“Do you want to sit in the car all night?”

“Not really.”

“Me neither,” Walt says. “And I don’t plan to indulge in this ridiculousness for the rest of senior year.”

I’m surprised by Walt’s vehemence. He usually tolerates Maggie’s neuroses without complaint.

“I mean, what’s going to happen to her?” he adds. “She’s going to back into a tree?”

“You’re right.” I look around. “There aren’t any trees.”

We start walking up the street to Tommy’s house. The one good thing about Castlebury is that even if it’s boring, it’s beautiful in its own way. Even here, in this brand-new development with hardly any trees, the grass on the lawns is bright green and the street is like a crisp black ribbon. The air is warm and there’s a full moon. The light illuminates the houses and the fields beyond; in October, they’ll be full of pumpkins.

“Are you and Maggie having problems?”

“I don’t know,” Walt says. “She’s being a huge pain in the ass. I can’t figure out what’s wrong with her. We used to be fun.”

“Maybe she’s going through a phase.”

“She’s been going through a phase all summer. And it’s not like I don’t have my own problems to worry about.”

“Like what?”

“Like everything?” he says.

“Are you guys having sex too?” I ask suddenly. If you want to get information out of someone, ask them unexpectedly. They’re usually so shocked by the question, they’ll tell you the truth.

“Third base,”Walt admits.

“That’s it?”

“I’m not sure I want to go any further.”

I hoot, not believing him. “Isn’t that all guys think about? Going further?”

“Depends on what kind of guy you are,” he says.

Loud music—Jethro Tull—is threatening to shake Tommy’s house down. We’re about to go in, when a fast yellow car roars up the street, spins around in the cul-de-sac, and comes to rest at the curb behind us.

“Who the hell is that?” Walt asks, annoyed.

“I have no idea. But yellow is a much cooler color than red.”

“Do we know anyone who drives a yellow Corvette?”

“Nope,” I say in wonder.

I love Corvettes. Partly because my father thinks they’re trashy, but mostly because in my conservative town, they’re glamorous and a sign that the person who drives one just doesn’t care what other people think. There’s a Corvette body shop in my town, and every time I pass it, I pick out which Corvette I’d drive if I had the choice. But then one day my father sort of ruined the whole thing by pointing out that the body of a Corvette is made of plastic composition instead of metal, and if you get into an accident, the whole car shatters. So every time I see a Corvette now, I picture plastic breaking into a million pieces.

The driver takes his time getting out, flashing his lights and rolling his windows up, down, and back up again as if he can’t decide if he wants to go to this party either. Finally, the door opens and Sebastian Kydd rises from behind the car like the Great Pumpkin himself, if the Great Pumpkin were eighteen years old, six-foot-one, and smoked Marlboro cigarettes. He looks up at the house, smirks, and starts up the walk.

“Good evening,” he says, nodding at me and Walt. “At least I hope it’s a good one. Are we going inside?”

“After you,”Walt says, rolling his eyes.

We. My legs turn to jelly.

Sebastian immediately disappears into a throng of kids as Walt and I weave our way through the crowd to the bar. We snag a couple of beers, and then I go back to the front door to make sure Maggie’s car is still at the end of the street. It is. Then I run into The Mouse and Peter, who are backed up against a speaker. “I hope you don’t have to go to the bathroom,”The Mouse shouts, by way of greeting. “Jen P saw Sebastian Kydd and freaked out because he’s so cute she couldn’t handle it and started hyperventilating, and now she and Jen S have locked themselves in the toilet.”

“Ha,” I say, staring carefully at The Mouse. I’m trying to see if she looks any different since she’s had sex, but she seems pretty much the same.

“If you ask me, I think Jen P has too many hormones,”The Mouse adds, to no one in particular. “There ought to be a law.”

“What’s that?” Peter asks loudly.

“Nothing,”The Mouse says. She looks around. “Where’s Maggie?”

“Hiding in her car.”

“Of course.”The Mouse nods and takes a swig of her beer.

“Maggie’s here?” Peter says, perking up.

“She’s still in her car,” I explain. “Maybe you can get her out. I’ve given up.”

“No problem,” Peter shouts. He hurries away like a man on a mission.

The bathroom scene sounds too interesting to miss, so I head upstairs. The toilet is at the end of a long hall and a line of kids are snaked behind it, trying to get in. Donna LaDonna is knocking on the door. “Jen, it’s me. Let me in,” she commands. The door opens a crack and Donna slips inside. The line goes crazy.

“Hey! What about us?” someone shouts.

“I hear there’s a half-bath downstairs.”

Several annoyed kids push past as Lali comes bounding up the stairs. “What the hell is going on?”

“Jen P freaked out over Sebastian Kydd and locked herself in the bathroom with Jen S and now Donna LaDonna went in to try to get her out.”

“This is ridiculous,” Lali declares. She goes up to the door, pounds on it, and yells, “Get the hell out of there, you twits. People have to pee!” When several minutes pass in which Lali does more knocking and yelling to no avail, she gives me an exaggerated shrug and says loudly, “Let’s go to The Emerald.”

“Sure,” I say, full of bluster, like we go there all the time.

The Emerald is one of the few bars in town with—according to my father—a reputation for being full of shady characters: i.e. alcoholics, divorcées, and drug addicts. I’ve only been three times, and each time I looked around desperately for these so-called degenerates but was never able to spot any patrons that fit the bill. In fact, I was the one who looked suspicious—I was shaking like a Slinky, terrified that someone was going to ask for my ID and, when I couldn’t produce it, call the police.

But that was last year. This year I’ll be seventeen. Maggie and The Mouse are nearly eighteen, and Walt is already legal, so they can’t kick him out.

Lali and I find Walt and The Mouse and they want to go too. We troop out to Maggie’s car, where she and Peter are deep in conversation. I find this slightly irritating, although I don’t know why. We decide that Maggie will drive Walt to The Emerald, while The Mouse will take Peter, and I’ll go with Lali.

Thanks to Lali’s speedy driving, we’re the first to arrive. We park the truck as far away from the building as possible in order to avoid detection. “Okay, this is weird,” I say, while we wait. “Did you notice how Maggie and Peter were having some big discussion? It’s very strange, especially since Walt says he and Maggie are having problems.”

“Like that’s a surprise.” Lali snorts.“My father thinks Walt is gay.”

“Your father thinks everyone is gay. Including Jimmy Carter. Anyway, [A-Z]alt can’t be gay. He’s been with Maggie for two years. And I know they definitely do more than make out because he told me.”

“A guy can have sex with a woman and still be gay,” Lali insists. “Remember Ms. Crutchins?”

“Poor Ms. Crutchins,” I sigh, conceding the argument. She was our English teacher last year. She was about forty years old and she’d never been married and then she met “a wonderful man” and couldn’t stop talking about him, and after three months they got married. But then, one month later, she announced to the class that she’d annulled her marriage. The rumor was that her husband turned out to be gay. Ms. Crutchins never came right out and admitted it, but she would let revealing tidbits drop, like, “There are just some things a woman can’t live with.” And after that, Ms. Crutchins, who was always full of life and passionate about English literature, seemed to shrink right into herself like a deflated balloon.

The Mouse pulls up next to us in a green Gremlin, followed by the Cadillac. It’s terrible what they say about women drivers, but Maggie really is bad. As she’s trying to park the car, she runs the front tires over the curb. She gets out of the car, looks at the tires, and shrugs.

Then we all do our best to stroll casually into The Emerald, which isn’t really seedy at all—at least not to look at. It has red leather banquettes and a small dance floor with a disco ball, and a hostess with bleached blond hair who appears to be the definition of the word “blousy.”

“Table for six?” she asks, like we’re all absolutely old enough to drink.

We pile into a banquette. When the waitress comes over, I order a Singapore Sling. Whenever I’m in a bar I always try to order the most exotic drink on the menu. A Singapore Sling has several different kinds of alcohol in it, including something called “Galliano,” and it comes with a maraschino cherry and an umbrella. Then Peter, who’s ordered a whiskey on the rocks, looks at my drink and laughs. “Not too obvious,” he says.

“What are you talking about?” I ask innocently, sipping my cocktail through a straw.

“That you’re underage. Only someone who’s underage orders a drink with an umbrella and fruit. And a straw,” he adds.

“Yeah, but then I get to take the umbrella home. And what do you get to take home besides a hangover?”

The Mouse and Walt think this is pretty funny, and decide to only order umbrella drinks for the rest of the night.

Maggie, who usually drinks White Russians, orders a whiskey on the rocks, instead. This confirms that something is definitely going on between Maggie and Peter. If Maggie likes a guy, she does the same thing he does. Drinks the same drink, wears the same clothes, suddenly becomes interested in the same sports he likes, even if they’re totally wacky, like whitewater rafting. All through sophomore year, before Maggie and Walt started going out, Maggie liked this weird boy who went whitewater rafting every weekend in the fall. I can’t tell you how many hours I had to spend freezing on top of a rock, waiting for him to pass by in his canoe. Okay—I knew it wasn’t really a canoe, it was a kayak, but I insisted on calling it a canoe just to annoy Maggie for making me freeze my butt off.

And then the door of The Emerald swings open and for a moment, everyone forgets about who’s drinking what.

Standing by the hostess are Donna LaDonna and Sebastian Kydd. Donna has her hand on his neck, and after he holds up two fingers, she puts her other hand on his face, turns his head, and starts kissing him.

After about ten seconds of this excessive display of affection, Maggie can’t take it anymore. “Gross,” she exclaims. “Donna is such a slut. I can’t believe it.”

“She’s not so bad,” Peter counters.

“How do you know?” Maggie demands.

“I helped tutor her a couple of years ago. She’s actually kind of funny. And smart.”

“That still doesn’t mean she should be making out with some guy in The Emerald.”

“He doesn’t look like he’s resisting much,” I murmur, stirring my drink.

“Who is that guy?” Lali asks.

“Sebastian Kydd,”The Mouse volunteers.

“I know his name,” Lali sniffs. “But who is he? Really?”

“No one knows,” I say. “He used to go to private school.”

Lali can’t take her eyes off him. Indeed, no one in the bar seems to be able to tear themselves away from the spectacle. But now I’m bored with Sebastian Kydd and his attention-getting antics.

I snap my fingers in Lali’s face to distract her.“Let’s dance.”

Lali and I go to the jukebox and pick out some songs. We’re not regular boozers, so we’re both feeling the giddy effects of being a little bit drunk, when everything seems funny. I pick out my favorite song, “We Are Family” by Sister Sledge, and Lali picks “Legs” by ZZ Top. We take to the dance floor. I do a bunch of different dances—the pony, the electric slide, the bump, and the hustle, along with a lot of steps I’ve made up on my own. The music changes and Lali and I start doing this crazy line dance we invented a couple of years ago during a swim meet where you wave your arms in the air and then bend your knees and shake your butt. When we straighten up, Sebastian Kydd is on the dance floor.

He’s a pretty cool dancer, but then, I expected he would be. He dances a little with Lali, and then he turns to me and takes my hand and starts doing the hustle. It’s a dance I’m good at, and at a certain point one of his legs is in-between mine, and I’m kind of grinding my hips, because this, after all, is a legitimate part of the dance.

He says, “Don’t I know you?”

And I say, “Yes, actually you do.”

Then he says, “That’s right. Our mothers are friends.”

“Were friends,” I say. “They both went to Smith.” And then the music ends and we go back to our respective tables.

“That was hilarious.”The Mouse nods approvingly. “You should have seen the look on Donna LaDonna’s face when he was dancing with you.”

“He was dancing with both of us,” Lali corrects her.

“But he was mostly dancing with Carrie.”

“That’s only because Carrie is shorter than I am,” Lali remarks.

“Whatever.”

“Exactly,” I say, and get up to go to the bathroom.

The restroom is at the end of a narrow hall on the other side of the bar. When I come out, Sebastian Kydd is standing next to the door as if he’s waiting to go in. “Hello,” he says. He delivers this in a sort of fakey way, like he’s an actor in a movie, but he’s so good-looking, I decide I don’t mind.

“Hi,” I say cautiously.

He smiles. And then he says something astoundingly ridiculous. “Where have you been my whole life?”

I almost laugh, but he appears to be serious. Several responses run through my head, and finally I settle on: “Excuse me, but aren’t you on a date with someone else?”

“Who says it’s a date? She’s a girl I met at a party.”

“Sure looks like a date to me.”

“We’re having fun,” he says. “For the moment. You still live in the same house?”

“I guess so—”

“Good. I’ll come by and see you sometime.”And he walks away.

This is one of the oddest and most intriguing things that has ever happened to me. And despite the bad-movie-ish quality to the scene, I’m actually hoping he meant what he said.

I go back to the table, full of excitement, but the atmosphere has changed. The Mouse looks bored talking to Lali, and Walt appears glum, while Peter impatiently shakes the ice cubes in his glass. Maggie suddenly decides she wants to leave. “I guess that means I’m going,” Walt says with a sigh.

“I’ll drop you first,” Maggie says. “I’m going to drive Peter home, too. He lives near me.”

We get into our respective vehicles. I’m dying to tell Lali about my encounter with the notorious Sebastian Kydd, but before I can say a word, Lali announces that she’s “kind of mad at The Mouse.”

“Why?”

“Because of what she said. About that guy, Sebastian Kydd. Dancing with you and not me. Couldn’t she see he was dancing with both of us?”

Rule number five: Always agree with your friends, even if it’s at your own expense, so they won’t be upset. “I know,” I say, hating myself. “He was dancing with both of us.”

“And why would he dance with you, anyway?” Lali asks. “Especially when he was with Donna LaDonna?”

“I have no idea.” But then I remember what The Mouse said. Why shouldn’t Sebastian dance with me? Am I so bad? I don’t think so. Maybe he thinks I’m kind of smart and interesting and quirky. Like Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice.

I dig around in my bag and find one of Maggie’s cigarettes. I light up, inhale briefly, and whoosh the smoke out the window.

“Ha,” I say aloud, for no particular reason.

CHAPTER SIX Bad Chemistry (#ulink_a08cbdcb-c6de-5445-b974-46f64de91f45)

I’ve had boyfriends before, and frankly, each one was a disappointment.

There was nothing horribly wrong with these boys. It was my fault. I’m kind of a snob when it comes to guys.

So far, the biggest problem with the boys I’ve dated is that they weren’t too smart. And eventually I ended up hating myself for being with them. It scared me, trying to pretend I was something I wasn’t. I could see how easily it could be done, and it made me realize that was what most of the other girls were doing as well—pretending. If you were a girl, you could start pretending in high school and go on pretending your whole life, until, I suppose, you imploded and had a nervous breakdown, which is something that’s happened to a few of the mothers around here. All of a sudden, one day something snaps and they don’t get out of bed for three years.

But I digress. Boyfriends. I’ve had two major ones: Sam, who was a stoner, and Doug, who was on the basketball team. Of the two I liked Sam better. I might have even loved him, but I knew it couldn’t last. Sam was beautiful but dumb. He took woodworking classes, which I had no idea existed until he gave me a wooden box he’d made for Valentine’s Day. Despite his lack of intelligence—or perhaps, more disturbingly, because of it—when I was around him I found him so attractive I thought my head would explode. I’d go by his house after school and we’d hang in the basement with his older brothers, listening to Dark Side of the Moon while they passed around a bong. Then Sam and I would go up to his room and make out for hours. Half the time, I worried I shouldn’t be there, that I was wasting precious time engaging in an activity that wouldn’t lead to anything (in other words, I wasn’t using my time “constructively,” as my father would say). But on the other hand, it felt so good I couldn’t leave. My mind would be telling me to get up, go home, study, write stories, advance my life, but my body was like a boneless sea creature incapable of movement on land. I can’t remember ever having a conversation with Sam. It was only endless kissing and touching in a bubble of time that seemed to have no connection with real life.

Then my father took me and my sisters away for two weeks on an educational cruise to Alaska and I met Ryan, who was tall and smooth like polished wood and was going to Duke, and I fell in love with him. When I got back to Castlebury, I could barely look at Sam. He kept asking if I’d met someone else. I was a coward and said no, which was partly true because Ryan lived in Colorado and I knew I’d never see him again. Still, the Sam bubble had been punctured by Ryan, and then Sam was like a little smear of wet soap. That’s all bubbles are anyway—a bit of air and soap. So much for the wonders of good chemistry.

With bad chemistry, though, you don’t even get a bubble. Me and Doug? Bad chemistry.

Doug was a year older, a senior when I was a junior. He was one of the jocks, a basketball player, friends with Tommy Brewster and Donna LaDonna and the rest of the Pod crowd. Doug wasn’t too bright, either. On the other hand, he wasn’t so good-looking that a lot of other girls wanted him, but he was good-looking enough. The only thing that was really bad about him was the zits. He didn’t have a lot of them, just one or two that always seemed to be in the middle of their life cycle. But I knew I wasn’t perfect either. If I wanted a boyfriend, I figured I would have to overlook a blemish or two.

Jen P introduced us. And sure enough, at the end of the week, he came shuffling around my locker and asked if I wanted to go to the dance.

That was all right. Doug picked me up in a small white car that belonged to his mother. I could picture his mother from the car: a nervous woman with pale skin and tight curls who was an embarrassment to her son. It made me kind of depressed, but I told myself I had to complete this experiment. At the dance, I hung around with the Jens and Donna LaDonna and some older girls, who all stood with one leg out to the side, and I stood the same way and pretended I wasn’t intimidated.

“There’s a great view at the top of Mott Street,” Doug said, after the dance.

“Isn’t that the place next to the haunted house?”

“You believe in ghosts?”

“Sure. Don’t you?”

“Naw,” he said.“I don’t even believe in God. That’s girl stuff.”

I vowed to be less like a girl.

It was a good view at the top of Mott Street. You could see clear across the apple orchards to the lights of Hartford. Doug kept the radio on; then he put his hand under my chin, turned my head, and kissed me.

It wasn’t horrible, but there was no passion behind it. When he said, “You’re a good kisser,” I was surprised. “I guess you do this a lot,” he said.

“No. I hardly do it at all.”

“Really?” he said.

“Really,” I said.

“Because I don’t want to go out with a girl who every other guy has been with.”

“I haven’t been with anyone.” I thought he must be crazy. Didn’t he know a thing about me?

More cars pulled in around us, and we kept making out. The evening began to depress me. This was it, huh? This was dating, Pod-style. Sitting in a car surrounded by a bunch of other cars where everyone was making out, seeing how far they could go, like it was some kind of requirement. I started wondering if anyone else was enjoying it as little as I was.

Still, I went to Doug’s basketball games and I went by his house after school, even though there were other things I wanted to do more, like read romance novels. His house was as dreary as I’d imagined—a tiny house on a tiny street (Maple Lane) that could have been in Any Town, U.S.A. I guess if I were in love with Doug it wouldn’t have mattered. But if I had been in love with Doug it would have been worse, because I would have looked around and realized that this would be my life, and that would have been the end of my dream.

But instead of saying, “Doug, I don’t want to see you anymore,” I rebelled.

It happened after another dance. I’d barely let Doug get to third base, so maybe he figured it was time to straighten me out. The plan was to go parking with another couple: Donna LaDonna and a guy named Roy, who was the captain of the basketball team. They were in the front seat. We were in the back. We were going someplace we’d never get caught, a place where no one would find us: a cemetery.

“Hope you don’t still believe in ghosts,” Doug said, squeezing my leg.“If you do, you know they’ll be watching.”

I didn’t answer. I was studying Donna LaDonna’s profile. Her hair was a swirl of white cotton candy. I thought she looked like Marilyn Monroe. I wished I looked like Marilyn Monroe. Marilyn Monroe, I figured, would know what to do.

When Doug unzipped his pants and tried to push my head down, I’d had enough. I got out of the car. “Charade” was the word I was thinking over and over again. It was all a charade. It summed up everything that was wrong between the sexes.

Then I was too angry to be frightened. I started walking along the little road that wound through the headstones. I might have believed in ghosts, but I wasn’t scared of them per se. It was people who were troubling. Why couldn’t I just be like every other girl and give Doug what he wanted? I pictured myself as a Play-Doh figure; then a hand came down, squeezing and squeezing until the Play-Doh oozed through the fingers into ragged clumps.

To distract myself, I started looking at the headstones. The graves were pretty old, some more than a hundred years. I started looking for one type in particular. It was macabre but that’s the kind of mood I was in. Sure enough, I found one: Jebediah Wilton. 4 mos. 1888. I started thinking about Jebediah’s mother and the pain she would have felt putting that little baby into the ground. I bet it felt worse than childbirth. I got down on my knees and screamed into my hands.

I guess Doug figured I would come right back, because he didn’t bother looking for me for a while. Then the car pulled up and a door opened. “Get in,” Doug said.

“No.”

“Bitch,” Roy said.

“Get in the car,” Donna LaDonna ordered. “Stop making a scene. Do you want the cops to come?”

I got into the car.

“See?” Donna LaDonna said to Doug. “I told you it was useless.”

“I’m not going to have sex with some guy just to impress you,” I said.

“Whoa,” Roy said. “She really is a bitch.”

“Not a bitch,” I said.“Just a woman who knows her own mind.”

“You’re a woman now?” Doug said, sneering. “That’s a laugh.”

I knew I should have been embarrassed, but I was so relieved it was over, I couldn’t be bothered. Surely, Doug wouldn’t dare ask me out again.

He did though. First thing Monday morning, I found him standing by my locker. “I need to talk to you,” he said.

“So talk.”

“Not now. Later.”

“I’m busy.”

“You’re a prude,” he hissed. “You’re frigid.”When I didn’t reply, he added, “It’s okay,” in a creepy tone. “I know what’s wrong with you. I understand.”

“Good,” I said.

“I’m coming by your house after school.”

“Don’t.”

“You don’t need to tell me what to do,” he said, spinning an imaginary basketball on his finger. “You’re not my mother.” He shot the imaginary basketball into an imaginary hoop and walked away.

Doug did come by my house that afternoon. I looked up from my typewriter and saw the pathetic white car pull hesitantly into the driveway, like a mouse cautiously approaching a piece of cheese.

A discordant phrase of Stravinsky came from the piano followed by the soft taps of Missy running down the stairs. “Carrie,” Missy called from below. “Someone’s here.”

“Tell him I’m not.”

“It’s Doug.”

“Let’s go for a drive,” Doug said.

“I can’t,” I begged. “I’m busy.”

“Listen,” he said. “You can’t do this to me.” He was pleading, and I started to feel sorry for him. “You owe me,” he whispered. “It’s only a drive in the car.”

“Okay,” I relented. I figured maybe I did owe him for embarrassing him in front of his friends.

“Look,” I said when we were in the car and driving toward his house. “I’m sorry about the other night. It’s just that—”

“Oh, I know. You’re not ready,” Doug said. “I understand. With everything you’ve been through.”

“No. It isn’t that.” I knew it had nothing to do with my mother’s death. But I couldn’t bring myself to tell Doug the truth—that my reluctance was due to the fact that I didn’t find him the least bit attractive.

“It’s okay,” he said. “I forgive you. I’m going to give you a chance to make it up to me.”

“Ha,” I said, hoping he was making a joke.

Doug drove past his house and kept going, down the dirt track that led to the river. Between his sad little street and the river were miles and miles of mud-flat farmland, deserted in November. I began to get scared.

“Doug, stop.”

“Why?” he asked. “We have to talk.”

I knew then why boys hated that phrase, “We have to talk.” It gave me a tired, sick feeling. “Where are we going? There’s nothing out here.”

“There’s the Gun Tree,” he said.

The Gun Tree was all the way down by the river, so named because a lightning strike had split the branches into the shape of a pistol. I began calculating my chances for escape. If we got all the way to the river, I could jump out of the car and run along the narrow path that led through the trees. Doug couldn’t follow in his car, but he could certainly outrun me. And then what would he do? Rape me? He might rape me and kill me afterward. I didn’t want to lose my virginity to Doug Haskell, for Christ’s sake, and definitely not like that. I decided he’d have to kill me first.

But maybe he did only want to talk.

“Listen, Doug, I’m sorry about the other night.”

“You are?”

“Of course. I just didn’t want to have sex in a car with other people. It’s kind of gross.”

We were about half a mile from civilization.

“Yeah. Well, I guess I can understand that. But Roy is the captain of the basketball team and—”

“Roy is disgusting. Really, Doug. You’re much better than he is. He’s an asshole.”

“He’s one of my best buds.”

“You should be captain of the basketball team. I mean, you’re taller and better looking. And smarter. If you ask me, Roy’s taking advantage of you.”

“You think?” He took his eyes off the road and looked at me. The road was becoming increasingly bumpy, made for tractors not cars, and Doug had to slow down.

“Well, of course,” I said smoothly. “Everyone knows that. Everyone says you’re a better player than Roy—”

“I am.”