Black Beech and Honeydew

Black Beech and Honeydew

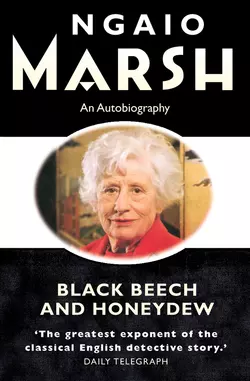

Ngaio Marsh

A series of Ngaio Marsh editions concludes with an edition of her autobiography.With all the insight and style her readers came to expect of her, Ngaio Marsh's autobiography captures all the joys, fears and hopes of a spirited young woman growing up in Christchurch, and charts her theatre and writing careers both in New Zealand and the UK. This sanguine, unpretentious and revealing book has been acclaimed for telling her most distinguished mystery - who was Ngaio Marsh?

The Ngaio Marsh Collection

Black Beech and Honeydew

Ngaio Marsh

In remembrance of my mother

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#uaa70476f-1a07-5d9a-a2f2-6521a2e3fd00)

Title Page (#u1111b694-bd1d-5348-a098-749f3cef7c1f)

Dedication (#u5b6d5804-eaab-55e7-a6d7-149fffef08e4)

CHAPTER 1 ‘All Kind Friends and Relations’ (#u16862342-1bde-5bf8-94b8-6c8d7e6d35ad)

CHAPTER 2 The Hills (#ue5b86749-c00c-571e-9f16-1be3fe5325ef)

CHAPTER 3 School (#u652a9056-8729-5902-b58b-e438415b643d)

CHAPTER 4 Mountains (#uc3ef97e5-dda5-55c1-bef2-6e3ea9c0aa29)

CHAPTER 5 The Coast (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 6 Winter of Content (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 7 Enter the Lampreys (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 8 Northwards (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 9 Turning Point (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 10 New Ways (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 11 Exercise Heartbreak and Recovery (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 12 Second Wind (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 13 A Last Look Back (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 1 ‘All Kind Friends and Relations’ (#ulink_ddef8fea-51a7-5f4b-bff5-2ffd4bb79923)

In 1912, on a midsummer morning in the foothills of the Southern Alps, I experienced a moment of absolute happiness: bliss, you might call it, only I don’t want to kill the recollection with high words.

Whenever I travel backwards, as of course one inclines to do as one grows older, it is at this point that I find an accent, a kind of halt, as emphatic as one of those little stations that interrupt the perspective of railway lines across the Canterbury Plains in New Zealand. I am almost afraid to stop there because, as everybody knows, one may return too often to past delights; to the smell of a book, of a crushed geranium leaf, of a box-tree hedge, hot with sunshine: or of honeydew in summertime.

This was a morning that would soon grow very warm. At that early hour – about half-past six – one could already smell the honeydew. It is exuded by a tiny insect and sweats in transparent globules through a black, mossy parasite that covers the trunks of native beech trees in New Zealand. Chip-dry twigs snapped under my feet. Bellbirds, exactly named, absent-mindedly prolonging their dawn-song, tinkled in the darker reaches of the bush. From our hidden tents, the smell of woodsmoke and frying bacon drifted through the trees. Someone climbed down to the river for water and a bucket clanked pleasantly. I came to a halt and there at once was the voice of the river filling the air in everlasting colloquy with its own wet stones.

It was then abruptly that I was flooded by happiness. In an agony of gratitude, I flung my arms round the nearest honeyed tree and hugged it. I was fourteen years old.

An impressionable age, of course, but, if this was a moment of typical adolescent rapture, I can only say that for me it was unique. One anticipates or remembers happiness; one feels but does not define, responds but does not pause to say, of the present delighted moment: ‘How astonishing! I am perfectly happy.’

I have recorded this sensation because I recognized it when it happened. For that reason it might be said to have been a moment of truth. With this trip to an isolated station I move down the parallel lines of my backward journey until they meet at the point where remembrance seems to begin.

In the first decade of this century, Fendalton was a small, genteel suburb on the outskirts of Christchurch in the South Island of New Zealand. Large Edwardian houses stood back in their own grounds masked by English trees. Small houses hid with refinement behind high evergreen fences. Ours was a small house. There was a lawn in front and an orchard behind. To me they were extensive but I don’t suppose they amounted to more than a quarter of an acre. I remember the trees: a pink-flowering, glossy, sticky-leafed shrub that overhung the garden gate, a monkey-puzzle which I disliked and a giant (or again so it seemed to me) wellingtonia that I was able to climb. From its branches I looked south across rooftops and gardens to a plantation of oaks with a river flowing through it where we kept our rowing-boat. Behind that was Hagley Park with a lake, sheep and playing fields, then the spire of Christchurch Cathedral and in the far distance, the Port Hills. I might have been an English child looking across a small provincial city except that when I turned to the north, there, on a clear day, forty miles across the plains, shone a great mountain range.

Outside my bedroom window stood a lilac bush, a snowball tree and a swing. In the orchard I remember only a golden pippin, currant bushes, a throbbing artesian well, hens and a rubbish heap. The rubbish heap is appallingly clear because in it one afternoon, when I was about six years old, I buried a comic song which I had previously stolen from the drawing room and torn to pieces. It was called ‘Villikins and His Dinah’ and the last line was ‘a cup of cold poison lay there by her side’. My father, who had an offhand, amused talent in such matters, used to sing this song in Dickensian cockney with mock heroics and whenever he did so struck terror to my heart. The paper-chase fragments of this composition must have been found, I think, that same evening. I remember my mother’s very beautiful troubled face and her saying rather despairingly, ‘But why? Why did you?’ I must have shown, or tried to express, my fear because I was not in deep disgrace and only had to say I was sorry to my father and promise to tell my mother about things that frightened me. In the end, but it seems to me it must have been a long time afterwards, I did manage to tell her of my terror of poison and how, without believing them, I constantly made up fantasies about it being spread like invisible butter on handtowels or inserted slyly into the porridge one was made to eat for breakfast.

‘But do you think I put it there?’ asked my gentle mother.

‘Not truly,’ I wept. ‘Not really and truly.’

With her arm sheltering me, she said profoundly, to herself, not to me: ‘It must have been The Fool’s Paradise.’

This, I should explain, was a play. Was it by Sutro or perhaps a translation from Sardou? My parents, who were gifted amateurs, had recently played in the piece and had, I imagine, rehearsed their scenes together in my hearing, never supposing that I understood a word of them. The theme was that of a femme fatale who slowly poisoned her husband and was suspected and finally accused of her crime by the family doctor. I have no idea whether it ended in her arrest or suicide but rather think the latter. I am sure my mother was right and that it was this highly coloured drama that engendered the terror which obsessed me, in the validity of which I did not believe and which took so long to evaporate. To this day, on the rare occasions that I use poison in a detective story, I am visited by a ludicrous aftertaste of my childish horrors.

It may be seen from this episode that I supported the theme, so indefatigably explored by psycho-novelists, of the anguish of the only child. I was, I am afraid, a morbid little creature.

For all this, there were raptures, delights and cosy satisfactions.

Here are my parents, standing before the range in an old-fashioned colonial kitchen. My father, an amateur carpenter, has been building a boat. He carries his pipe in his hand and wears a red tam-o’-shanter on his head. His arm is round my mother. They are smiling at me. I am in a sort of fenced baby swing that has been slung from the ceiling. I swoop towards them and my father says delightfully, ‘We don’t want you.’ He gives me a shove and I am swung away from them, shouting with laughter. He has me on his shoulders. The doors have been shut and we are in a dark passage but perfectly secure. He gives a leap and we are in the roof. He is talking to the friendly house-pixies who reply in falsetto voices. Do I know that it’s an act? I think I do, but am enchanted all the same. He tells me, for the hundredth time, his original story of Maria and John who bought a piglet called Grunter which, in trickery, was replaced by a terrier pup. If he changes a word I correct him. He tries Alice in Wonderland but is too dramatic with ‘Off With Her Head’ and frightens me. He reads Pickwick Papers and The Ingoldsby Legends. I am enraptured, particularly with Mr Winkle with whom, for some reason, I feel I have much in common: timidity perhaps. Even the discovery, when I look into the book myself, of the awful picture of a dying clown in a four-poster, although it appals me, doesn’t put me off Pickwick Papers. Worse than this is the cut of the Dead Drummer in Ingoldsby. The book is in our Edwardian drawing room, a tiny peacock-blue and white place. I sneak in there, and for the sheer compulsive horror of it, turn the pages until the ghastly lamps of the dead drummer’s eyes are turned up at me. Further on and still worse is the Nun of Netley Abbey being walled up by smug-faced monks. Yet neither of these diminishes my relish of the Witches Frolic, of the macabre, the really ghastly, but strangely enjoyable reiterations of ‘The Hand of Glory’ or the rollicking wholesale slaughters of Sir Ingoldsby Bray. I am enchanted by the legend of The Leech of Folkestone and gratified when my father points out that the description of Thomas Marsh’s Arms correspond with our own. These, with the Teutonic brutalities of the brothers Grimm, leave me engaged but unmoved – yet a story of Hans Andersen is so dreadful that even now I don’t enjoy recalling it. Who can tell what will frighten or delight a child, or why?

II

It seems to me now that in those early days my father was a kind of a treat: that I enjoyed him enormously without being involved with him. It was my mother who had the common but appalling task of ‘bringing me up’ and who had to steer an uncharted course between the nervous illogic of a delicate child, prone to fear, and the cunning obstinacy of a little girl determined to give battle in matters of discipline. Here she is, suddenly, running in a preoccupied manner across the lawn from the garden gate where she has said goodbye to a caller. She runs with a graceful loping stride, unhampered by her long skirt: brown stuff with brown velvet endorsements. I watch her from the dining-room window and twiddle the acorn end of the blind cord. She looks up and sees me and a smile, immensely vulnerable, breaks over her face. How dreadfully easy it is to love and hurt her. I adored, defied and finally obeyed my mother and believed that she understood me better than anyone else in my small world.

It was a very small world indeed: a nurse called Alice, whom I don’t remember and who must have left me when I was still a baby, a maid called May who had a round red face and was considered a comic, my maternal grandparents, my parents and their circle of friends. A cat called Susie and a spaniel called Tip.

Quite early in the day I learned to laugh at my father: not unkindly but because it was impossible to know him well and not to think him funny. He thought himself funny when his oddities were pointed out to him. ‘I didn’t!’ he would say to my mother. ‘How you exaggerate! I did not, Betsy.’ And break out laughing. It was, in fact, impossible to exaggerate his absent-mindedness or the strange fantasies that accompanied this comic-opera trait in his character.

‘My saddle-tweed trousers have gone!’ he announced, making a dramatic entrance upon my mother and a luncheon guest.

‘They can’t have gone.’

‘Completely. You go and look. Gone! That’s all.’

‘How can they have gone?’

My father made mysterious movements of his head in the direction of the dining room and May.

‘Taken them to give that chap,’ he whispered. May had a follower.

‘Oh, no, Lally. Nonsense.’

‘All right! Where are they? Where are they?’

‘You haven’t looked properly.’

He stared darkly at her and retired. Doors and drawers could be heard angrily banging. Oaths were shouted.

‘Are they gone, do you suppose?’ asked our visitor who was a close friend.

‘No,’ said my mother composedly.

My father returned in furious triumph. ‘Well,’ he sneered, ‘that’s that. That’s the end of my saddle-tweed trousers.’ He laughed shortly. ‘You won’t get cloth like that in New Zealand.’

‘They must be somewhere.’

He stamped. His eyes flashed. ‘They are not somewhere,’ he shouted. ‘That damn’ girl’s stolen them.’

‘Ssh!’

My father’s nostrils flared. He opened his mouth.

‘What are those things on your legs, my dear chap?’ asked our guest.

My father looked at his legs. ‘Good Lord!’ he said mildly, ‘so they are.’

Early one morning he met Susie, our cat, walking in the garden. He carried her to my mother who was not yet up.

‘Look, Betsy,’ he said. ‘I found this cat walking in the garden. Isn’t she like Susie?’

‘She is Susie,’ said my mother.

‘I thought you’d say that,’ he rejoined, delightedly. Susie purred and rubbed her face against his. ‘She’s awfully tame. You’d think she knew me, wouldn’t you?’ asked my father.

‘It is Susie,’ said my mother on a hysterical note.

He smiled kindly at her and put Susie down. ‘Run along, old girl,’ he said. ‘Go home to your master.’

My mother was now laughing uncontrollably.

‘Don’t be an ass, Betsy,’ said my father gently and left her.

It must not be supposed that he was an unintelligent man. He was widely read, particularly in biology and the natural sciences, was an enthusiastic rationalist and a member of the Philosophical Society. He was also an avid reader of fiction. Of the Victorians, he most enjoyed Dickens and Scott. My mother disliked Scott because of his historical inaccuracies and bias. None of his novels was in the house. She deeply admired Hardy and once told me that after reading the end of Tess, she sat up all night, imprisoned in distress and unable to free herself. In later years we all three read and discussed the Georgian novelists. My mother’s favourites were Galsworthy (with reservations: she thought Irene a stuffed dummy) and Conrad. Almayer’s Folly she read over and over again. Somehow her copy of this novel has been lost. I would like to discover why it so held her. My father’s favourite was Aldous Huxley though he often remarked that the chap was revolting for the sake of being revolting and that Point Counter Point gained nothing by its elaborate form. He was more gregarious in his reading than my mother and would sometimes devour a ‘shilling shocker’. His hand trembled and his pipe jigged between his teeth as he approached the climax. ‘Frightful rot!’ he would say. ‘Good Lord! Regular Guy Boothby stuff,’ and greedily press on with it.

When I was about four years old, I was given a miniature armchair made of wicker and a children’s annual. I remember dragging the chair on to the lawn, seating myself, opening the book and thinking furiously, ‘I will read. I will read.’ After some boring, but I fancy, brief, struggles with The Dog Has Got a Bone and a beastly poem about reindeer, I went forward under my own steam and became an avid bookworm.

My parents never stopped me reading a book though I believe my mother was at pains to see that nothing grossly ‘unsuitable’ was left in my way. The criterion was style: ‘He could write well,’ my mother said of the forgotten William J. Locke, ‘but he pot-boils. Very second-rate.’ I became something of an infant snob about books, and, like my father, felt a bit below par when I read Chums and Buffalo Bill, but continued, at intervals, to do so.

My father was English and my mother a New Zealander. She was the one, however, who doggedly determined that I should not acquire the accent. ‘The cat,’ I was obliged interminably to repeat, ‘sat on the mat and the mouse ran across the barn.’ ‘The cart,’ my father would interrupt in a falsetto voice, ‘sart on the mart arnd the moose rarn across the bawn.’ I thought this excruciatingly witty and so did my mother but by these means the accent was held at bay.

In spite of his anti-religious views my father can have made no objection to my being taken to our parish church or taught to say my prayers. These I found enjoyable. ‘Jesustender. Shepherdhearme.’ ‘Our Fatherchart’ and a monotonous exercise beginning ‘God bless Mummy and Daddy and All Kind Friends and Relations. God bless Gram and Gramp and – ’ It was prolonged for as long as my mother could take it. ‘Susie – and Tip – ’ I would drone, desperate for more objects of beatitude to fend off the moment when I would be left to set out upon the strange journeys of the night. These were formidable and sometimes appalling. There was one uncouth and recurrent dream in which everything Became Too Big. It might start with one’s fingers rubbing gigantically together and with a sickening threepenny piece that swelled horrifically between forefinger and thumb. Then everything swelled to become stifling and I awoke sobbing in my mother’s embrace. With a strangely logical determination, I learned to recognize this nightmare while I was experiencing it and trained my sleeping self to force the strangulated dream-scream that would deliver me.

‘I know,’ my father said. ‘I used to have it. Beastly, isn’t it, but only a dream. One grows out of it.’

My cot with its wooden spindle sides was brought into my parents’ room. In it, on more propitious nights, I sailed and flew immense distances into slowly revolving lights, rainbow chasms and mountainous realms of incomprehensible significance, through which my father’s snores surged and receded. Asleep and yet not asleep, I made these nightly journeys: acquiescent, vulnerable, filled with a kind of wonder.

There were day dreams, too, some of them of comparable terror and wonder, others cosy and familiar. I cannot remember a time when I was not visited occasionally, and always when I least expected it, by an experience which still recurs with, if anything, increasing poignancy. It is a common experience and for all I know there may be a common scientific explanation of it. It comes suddenly with an air of truth so absolute that one feels all other times must be illusion. It is not a sensation but a confrontation with duality. One moves outside oneself and sees oneself as a complete stranger and this is always a shock and an astonishment although one recognizes the moment and can think: ‘Here we go again. This is it.’ It is not self-hypnotism, because there is no loss of awareness as far as everyday surroundings are concerned: only the removal of oneself from the self who observes them and the overwhelming sensation of strangeness. It seems that if one held on to this moment and extended it one would make an enormous discovery but, for me, at least, this is impossible and I always return. Is this, I wonder, what was meant originally by being ‘beside oneself’. It is an odd phenomenon and as a child I grew quite familiar with it.

My grandmother considered that my religious observances were inadequate. When she came to stay with us she brought a Victorian manual which had been the basis of my mother’s and aunts’ and uncles’ dogmatic instruction. It was called Line Upon Line and was in the form of dialogue, like the catechism: Q. and A.

‘“Who,”’ asked my grandmother, beginning at the beginning, ‘“is God?”’

I shook my head.

‘“God,”’ said my grandmother, taking both parts, ‘“is a Spirit.”’

Reminded of the little blue methylated flame on the tea tray I asked: ‘Can you boil a kekkle on Him, Gram?’

She turned without loss of poise to Bible Stories: to Balaam and his ass. I suggested cooperatively that this was probably a circus donkey. My father was enchanted.

My grandmother told my mother that it was perhaps rather too soon to begin religious instruction and, instead, read me the Peter Pan bits out of The Little White Bird.

When I was about twelve my father brought home the collected works of Henry Fielding. ‘Jolly good stuff,’ he said. ‘You’d better read it.’

I began with the plays and was at once nonplussed by many words. ‘What is a “wor"?’ I asked my father who said I knew very well what a war was and mentioned South Africa. ‘This is spelt differently,’ I said, nettled. ‘It seems to be some sort of girl.’ My father quickly said it was a ‘fast’ sort of girl. This was good enough. I had heard girls stigmatized as being ‘fast’ and certainly these ladies of Fielding’s seemed to behave with a certain incomprehensible alacrity. My father suggested that I try Tom Jones. I did so: I read it all and also, since Smollett turned up at this juncture, Roderick Random. It bothered me that I could not greatly enjoy these works since David Copperfield, whom I adored, had at my age or earlier, relished them extremely. I, on the contrary, still doted upon Little Lord Fauntleroy.

We were, as I now realize, hard up. On both sides I came from what Rose Macaulay called ‘have-not’ families. My father was the eldest of ten. When he was still a schoolboy his own father (the youngest of three) died, leaving his widow in what were called reduced circumstances. He was a tea broker in the days of the clippers. This was considered OK socially for a younger son but then ‘an upstart called Thomas Lipton’ came along with his common retail packets and instead of following suit like a sensible man and going into ‘trade’ my grandfather remained genteelly aloof and his affairs went into a decline. His elder brother, William, was in the Colonial Service and became a Vice Admiral and Administrator of Hong Kong. Upon him, a childless man, the hopes of my grandmother depended.

Having begun in a prep school at Harrow and been destined, I suppose, for the public school, my father declined, with the family fortune, upon a number of private establishments but finally was sent to Dulwich College. He used to tell me how it was founded in Elizabethan times by a wonderful actor called Alleyn. The name stuck in my memory. My grandmother had inherited a small Georgian house near Epping and there she coped vaguely with her turbulent sons and three docile daughters with whose French governess one of my great-uncles soon eloped. This was Uncle Julius, a ‘wag’ as his contemporaries would have said and an original: much admired by his nephews, especially by my father. His wife had a markedly Gallic disposition, according to her legend, and unfortunately went mad in later life and used to send flamboyant Christmas cards to my father addressed to H. E. Marsh Esq., General Manager, The Bank of New Zealand, New Zealand. This, as will appear, was a gross overstatement. My father, who had a deep and passionate love of field sports, used to poach with his Uncle Julius on the game preserves of his more richly possessed second cousin. I still have the airgun he bought for this purpose. It is made to resemble a walking-stick. Perhaps his propensity for firearms led him into joining the Volunteers who preceded the New Zealand Army. Before he married he had already received a commission from Queen Victoria in which he was referred to as her ‘trusty and well-beloved Henry Edmund’. He continued with his martial activities until the Volunteers dissolved into a less picturesque organization. I used to think he looked perfectly splendid in his uniform.

The family is supposed to derive from the reprobate de Mariscos of Lundy. Whether this is really so or not, the legend is firmly implanted in all our bosoms. When, as a girl, I read of Geoffrey de Marisco who had the effrontery to stab a priest in the presence of the King, I asked myself if my father’s anticlerical bias was perhaps hereditary. By the reign of Charles II we are on firm historical ground for there is Richard Stephen Marsh, an Esquire of the Bedchamber, a direct forebear and almost the only really interesting character, apart from the de Mariscos, that the family has thrown up. He concerned himself with the trials and misfortunes of Fox, the Quaker, and actually persuaded the King so far out of his chronic lethargy as to intercede very mercifully between Fox and his savage persecutors. It is a curious and all too scantily documented affair. Apparently not only Esquire Marsh, as he is invariably called, but Charles himself responded to the extraordinary personality of this intractable Quaker. Although Marsh died an Anglican and an incumbent of the Tower (or should it be ‘Constable’) there seems to have been some sort of Foxian hangover because his descendants became Quakers and remained so until my great-great-grandfather married out of the Society of Friends and returned to the Church of England. My father was never rude about the Society of Friends.

In Uncle William’s day, the Governor of Hong Kong – a Pope-Hennessey – was often absent and twice, for long stretches, Uncle William was called upon to administer the government of the Colony. Yellowing photographs portray him in knickerbockers and sola topee, seated rather balefully under a marquee among ADCs in teapot attitudes and ladies with croquet mallets. One of his nieces (’Imported,’ my father used to say, ‘for the purpose.’) was married to Thomas Jackson, the founder of the Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank. (’Good Lord! They’ve stuck up a statue to Tom Jackson!’)

These connections were supposed to settle my father’s future. On leaving school he was sent to learn Chinese at London University and banking at the London office of the Hong Kong-Shanghai. From here, aided perhaps by nepotic shoves, he was to mount rapidly into the upper reaches of Head Office. Instead, he went, as the saying then was, into a consumption and was sent to South Africa where, after a stay on the bracing veldt, he came out of it again. What was to be done with him?

Uncle William, now in retirement, visited New Zealand where his brother-in-law had founded the Colonial Bank. Indefatigable in good works, he sent for my father. The pattern was to be repeated in a more favourable climate. No sooner were my father’s feet planted on the ladder than, owing to political machinations, the Colonial Bank broke. Uncle William returned to England. My father got a clerkship in the Bank of New Zealand and there remained until he retired. I can imagine nobody less naturally suited to his employment. He might have been a good man of science where absence-of-mind is tolerantly regarded: in a bank clerk it is a grave handicap. When I was about ten years old, very large sums of money were stolen from my father’s desk and from that of his next-door associate. I can remember all too vividly the night he came home with this frightful news. Sensible of my parents’ utter misery I tried to cheer them up by playing ‘Nights of Gladness’ very slowly with the soft pedal down. I was not musical and in any case it is a rollicking waltz.

It was an inside job and the thief was generally known but there was not enough evidence to bring him to book and the responsibility was my father’s. Uncle William, always helpful, died at this juncture and left him a legacy from which he was able to replace the loss. The amount that remained was frivolously invested for him in England and also lost. He was a have-not.

His rectitude was enormous: I have never known a man with higher principles. He was thrifty. He was devastatingly truthful. In many ways he was wise and he had a kind heart, and a nice sense of humour. He was never unhappy for long: perhaps, in his absent-mindedness, he forgot to be so. I liked him very much.

III

My mother’s maiden name was Rose Elizabeth Seager. Her paternal grandfather was completely ruined by the economic disturbances that followed the emancipation of slaves in the West Indies. As the Society of Friends was in a considerable measure responsible for this admirable reform, it is not too fanciful, perhaps, to suggest that one great-grandfather may have had a share in the other’s undoing. There is a parallel in the later history of the two families. Among the Seagers also, there appears briefly an affluent and unencumbered uncle to whom my great-grandfather was heir. The story was that this uncle took his now impoverished nephew to Scotland to see the estates he would inherit and on the return journey died intestate in the family chaise. His fortune was thrown into Chancery and my great-grandfather upon the world. He got some extremely humble job in the Middle Temple and my grandfather went to the choir school of the Temple Church. None of the family fortunes was ever recovered.

These misadventures sound like the routine opening of a dated and unconvincing romance and I think were so regarded by my mother and her brothers and sisters. Perhaps they grew tired of hearing their father talk about the fortune lost in Chancery and more than a little sceptical of its existence. Indeed stories of ‘riches held in Chancery’ have a suspect glint over them, as if the narrator had looked once too often into Bleak House. Moreover, my grandfather – Gramp – had a reputation for embroidery. He was of a romantic turn, and extremely inventive and he had a robust taste in dramatic narrative. The story of the lost fortune was held to be one of Gramp’s less successful excursions into fantasy and his virtuoso performance of running back at speed through his high-sounding ancestry to the Conquest was tolerated rather than revered.

He died when I was about eighteen. My mother and aunts went through his few possessions and discovered a trunkful of letters which turned out to be a correspondence between his own father and a firm of London solicitors. They were chronologically assembled. The earlier ones began with references to ancient lineage and ended with elaborate compliments. The tone grew progressively colder and the last letter was short.

‘Dear Sir: We are in receipt of your latest communication which we find impertinent and hostile. We have the honour to be your obedient servants…’

They were all about estates in Scotland, a death in a family chaise and monies in Chancery. The sums mentioned were shatteringly large.

Even then my mother was incredulous and I think would have remained so had not she and I, sometime afterwards, gone to stay with friends in Dunedin. Our host was another victim of the courts of Chancery and, like my great-grandfather, had written to his family solicitors in England to know if there was the smallest chance of recovery. They had replied extremely firmly that there was none but, for his information, had enclosed a list of the principal – is the word heirs? – to monies in Chancery. There, almost at the top of the list, which was a little out of date, was Gramp. For once, he had not exaggerated.

He had come as a youth to the province of Canterbury in New Zealand in the early days of its settlement. He too was a ‘have-not’ and also a spendthrift but he enjoyed life immensely. He met my grandmother – Gram – in Christchurch. They went for their honeymoon in a bullock wagon. Canterbury in the 1850s was still a swamp.

One of my grandfather’s acquaintances of the early days was Samuel Butler who had taken up sheep-country in a mountainous region which is now sometimes called after his Utopian romance – Erewhon. ‘Odd chap, Sam Butler,’ Gramp used to say and then he would tell us of the occasion when he went to stay with Butler who met him at the railhead somewhere out on the Canterbury Plains and drove him over many miles of very rough country, through water-races and a dangerous river up into Mesopotamia which is the true name of this part of the Alps.

While Gramp was staying there, Butler received a letter from an acquaintance, inviting himself as a guest. Butler took this in very bad part and did nothing but grumble. He would not allow Gramp to relieve him of the long and tedious journey to the rendezvous but settled angrily on their both going. Hour after hour their gig bumped and jolted over pleistocene inequalities. When they achieved the railhead and the train arrived with the self-invited guest, Gramp proposed to transfer to the backward-looking rear seat of the gig.

‘No you don’t, Seager!’ Butler shouted, irritably slamming his guest’s valise under the seat. ‘Stay where you are, God damn it.’ His wretched guest climbed up behind.

They set off for Mesopotamia. Butler became excited by some topic and talked and drove vigorously. He touched up the mare and they staggered through a watercourse at an inappropriate pace and drove rapidly on over Turk’s heads and boulders. My grandfather felt sorry for the guest. He turned to include him in the conversation and found that he was no longer there.

‘Butler – your visitor! He has fallen off. That last water-race-’

Butler broke out in a stream of vituperation, and could scarcely be persuaded to turn back. He did so, however, and presently they met the guest, wet and bruised and plodding desperately towards the Southern Alps. Butler abused him like a pickpocket and could scarcely wait for him to climb back on his perch.

Like all Gramp’s stories this should, I suppose, be taken with a pinch of salt but he used to laugh so heartily when he told it and stick so closely to the one version that I feel it must have been, like the blue blood and monies in Chancery, substantially true.

Of Gram’s family I know next to nothing except that they lived in Gloucestershire and that her great-grandparents were friends of Dr Edward Jenner. Gram’s great-grandmother kept a journal which a century after it was written Gram showed to my mother. It set out how Dr Jenner became interested in the West Country belief that persons who had had cowpox never developed smallpox and he asked my great-to-the-fourth-power grandmother if she would have a record kept of her own dairymaid’s health. She became as interested as he and the journal was full of his theories. Finally, between them, they persuaded a dairymaid called Sarah Nelmes to let Dr Jenner take lymph from a cow poxvesicle on her finger. With this, on 14th May, 1775, he vaccinated a boy called Phipps and from then onwards his advances were excitedly recorded by his friends. My mother did not know what became of her great-great-grandmother’s journal and indeed the only other piece of information she had about Gram’s people was that some of them are buried in Gloucester Cathedral where she looked them up when she was in England. Gram was rather austere and extremely conventional but she had a twinkle.

On Gramp’s immigration papers he appeared as a ‘schoolmaster’ but never practised as one. Instead, he gave his romantic streak full play. He joined the newly formed police force, took a hand in designing a dashing uniform which he wore when he made a number of exciting arrests including those of a famous sheep-stealer and a gigantic Negro murderer. He was put in charge of the first gaol built in the Province but left this job to become superintendent of the new mental asylum: Sunnyside. He was not, of course, a doctor (I imagine there were not enough to go round), but he was strangely advanced in his methods, playing the organ to his ‘children’ as he called the patients, whom he loved, and using a form of mesmerism on some of the more violent ones. If any of his own family had a headache my grandmother would say crisply: ‘Go to your father and be mesmerized.’ Gramp would flutter his delicate hands across and across their foreheads until the headache had gone. He did this with the full approval of the visiting medical superintendent, Dr Coward, who was very interested in Gramp’s therapeutic methods.

He had a good stage built in the hall at Sunnyside, no doubt as part of the treatment but also, I suspect, because theatre was his ruling passion. Here he produced plays, using his children, his friends and some of the more manageable patients as actors. He also performed conjuring tricks, spending far too much of his own money on elaborate and costly equipment. His patter was magnificent. One by one as each of my aunts grew to the desirable size, she was crammed into a tortuous under-suit of paper-thin jointed steel, and, so attired, walked on the stage, seated herself on a high stool at an expensive trick-table, adopted a pensive attitude, her elbow on the table, her finger on her brow and, like Miss Bravassa, contemplated the audience. A spike in the elbow of her armour engaged with a slot in the table. ‘Hey presto!’ Gramp would say, waving his wand and turning a secret key in his daughter’s back. The armour locked. Puck-like, Gramp snatched the stool from under her and there she was: suspended. My Aunt Madeleine, at the appropriate age, was plump. The armour nipped her and she often wept but as the next-in-order was still too small, she was squeezed into service until Gram forbade it. Gramp busily sawed his daughters in half, shut them up in magic cabinets and caused them to disappear. The patients adored it.

I can just remember him doing some of his sleight-of-hand tricks at his grandchildren’s birthday parties and playing ‘See Me Dance the Polka’ while we held out our skirts and bounced.

Of all his children, only my mother inherited his love of theatre and she did so in a marked degree. I know I am not showing partiality when I say that she was quite extraordinarily talented. From the time I first remember her acting it was never in the least like that of an amateur: her approach to a role, her manner of rehearsing, her command of timing and her personal impact were all entirely professional. My grandfather used to organize productions in aid of charities and his daughter became so well known that when an American Shakespearean actor, George Milne, brought his company to New Zealand he asked my mother, then nineteen years old, to play Lady Macbeth with him in Christchurch. She did so with such success that he urged her to become an actress. I cannot imagine what Gram thought of all this. One would suppose her to have been horrified but perhaps her built-in Victorianism worked it out that her husband knew best. There can be little doubt that Gramp was all for the suggestion. The real objections appear to have come from my mother. Strangely, as it seems to me, she had no desire to become a professional actress. The situation was repeated when the English actor Charles Warner, famous for his role in Drink, visited New Zealand. He was a personal friend of my grandfather who, I supposed, caused my mother to perform before him. Warner offered to take her into his company and launch her in England. She declined. He and his wife suggested that she should come as their guest to Australia and get the taste of a professional company on tour. In the event, she did cross the Tasman Sea under Mrs Warner’s wing. She stayed with family friends in Melbourne, and saw a good deal of the company while she was there. This adventure, though she seemed to have enjoyed it, confirmed her in her resolve. The life, she once said to me, ‘was too messy’. I have an idea that the easy emotionalism and ‘bohemian’ habits of theatre people, while they appealed to her highly developed sense of irony, offended her natural fastidiousness. In many ways a pity, and yet, such is one’s egoism, I get a peculiar feeling when I reflect that if she had been otherwise inclined I would have been – simply, not. She returned to New Zealand and after an interval of a year or two met and married my father.

It seems to me that almost always a play was toward in our small family and that my nightmare, The Fool’s Paradise, was only one of a procession. As a child I did not really enjoy hearing my mother rehearse. She became a stranger to me. If the role was a dramatic or tragic one, I was frightened and curiously embarrassed. When as a very small girl, she asked me if I would like to walk on for a child’s part in – I think – a Pinero play, I was appalled. Yet I loved to hear all the theatre-talk, the long discussions on visiting actors, on plays and on the great ones of the past. When I was big enough to be taken occasionally to the play my joy was almost unendurable.

One was made to rest in the afternoon. Blinds were drawn and one lay in a state of tumult for the prescribed term, becoming quite sick with anticipation. When confronted with food at an unusual hour, one could eat nothing.

‘Good Lord!’ said my father. ‘Look at the child. She’d better not go if she gets herself into such a stink over it.’

Frightful anxieties arose. Suppose the tickets were lost, suppose we were late? Suppose, from sheer excitement, I were to be sick? In the earliest times, I seem to remember hansom-cabs, evening dress, long gloves and a kind of richness about the arrival but later on, when economy ruled, we waited in queues for the early doors. It was all one to me. There I was, sitting between my parents, in an expectant house. It was no matter how long we waited: the time came when the lights were dimmed and a band of radiance flooded the curtain fringe, when the air was plangent with the illogic of tuning strings, when my heart was either in my stomach or my throat, when a bell rang in the prompt corner and the play was on.

Which came first: Sweet Nell of Old Drury or Bluebell in Fairyland? Perhaps Bluebell. To this piece I was escorted by my great friend, Ned Bristed: a freckled child, perhaps a year my senior. We were taken to the theatre by his mother who saw us into our seats in the dress circle and then left us there, immensely important, and collected us at the end when we returned in a rapturous trance to Ned’s house where I spent the night. Ned and I were in perfect accord. Some twenty years later, long after he had been killed in action, it fell to my lot to produce Bluebell in Fairyland. I stood in the circle and watched a dress rehearsal and was able for a moment to put into the front row the shadows of a freckled boy and a small girl: ecstatic and feverishly wolfing chocolates.

My mother took me to a matinée of Sweet Nell of Old Drury. I saw the whole thing in terms of a fairy tale and fell madly in love with Charles II in the person of Mr Harcourt Beatty. How kindly he shone upon the poor orange girl (Miss Nellie Stewart), how beastly was the behaviour of the two witches, Castlemaine and Portsmouth, how menacing and how superbly outsmarted was the evil Jeffreys. The company returned, we went again and I became even more deeply committed. Later on, when I began to do history, it was irritating to find so marked a note of disapproval in the section on Charles II: Mr Harcourt Beatty, I felt, and not the pedagogue Oman, had the correct approach.

Our visits to the play were not always so successful. When Janet Achurch came, with Ibsen, I was not taken to see her and wish that I had been but, unless I have confused the occasions, her company, or one that came soon after it, also played Romeo and Juliet. To this my mother and I went one afternoon. She was immensely stimulated: too much so, for once, to notice my growing alarm. When the Montagues and Capulets began to set about each other in the streets of Verona I asked nervously: ‘They aren’t really fighting, are they?’

‘Yes, yes!’ she replied excitedly. I dived into her lap, surfaced at long intervals and upon finding that people seemed to be dreadfully unhappy, hurriedly submerged again. Worst of all, of course, there was Poison and a girl was Taking It. I vividly remember one final appalled glance at the Tomb of the Capulets and what was going on there and then a shaken return to Fendalton.

‘I expect I should have brought you away,’ my mother used to say long afterwards, ‘but it was a good company. The Mercutio was wonderful.’ I know exactly how she felt: it couldn’t have been expected of her. She was always very loving and patient over my fears and a constant refuge from them.

She read aloud quite perfectly: not with the offhand brio of my father but with a quiet relish that was immensely satisfying. One was gathered into the book as if into a lap and completely absorbed by it. Her voice was unforced and beautiful.

Whatever I may write about my mother will be full of contradictions. I think that as I grew older I grew, better perhaps than anyone else, to understand her. And yet how much there was about her that still remains unaccounted for, like odd pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Of one thing I am sure: she had in her an element of creative art never fully realized. I think the intensity of devotion which might have been spent upon its development was poured out upon her only child, who, though she returned this love, inevitably and however unwisely, began at last to make decisions from which she would not be deflected.

IV

It so happened that my two constant companions when I was very small and before I met Ned, were also boys: another only child called Vernon, and my cousin Harvey. They were both older than I and good-naturedly bossed me: always I was the driven horse, obediently curvetting and prancing, always the seeker and never the hider. I accepted their attitude and listened with the deepest respect to their stories of other little boys to whom they ‘owed a hiding’. On a seaside holiday with our parents, Harvey and I discovered a religious affinity. We built a sand-castle and on the top moulded a cross. This gave us an extremely complacent and holy feeling.

Of all my parents’ circle I loved best the friend who was present on the occasion of the saddle-tweed trousers. His name was Dundas Walker. He acted in most of their plays and made a great success of ‘Cis’, the precocious youth in Pinero’s farce The Magistrate. Finding Dundas rather difficult to say I called him by this Victorian nickname but afterwards changed it to ‘James’. Destined by his people for the church, he became instead a professional actor. In this choice he was egged on by my mother: was this one of her contradictions or did she realize, quite correctly, that he would be happy in no other sphere?

He invented the most entrancing games: ‘Visiting’, for instance, when he was always Mrs Finch-Brassy and I, Mrs Boolsum-Porter. ‘Forgive me, my dear,’ he would say, ‘if I borrow your poker. A morsel of your delicious cake has lodged in a back tooth and I must positively rid myself of it.’ I always handed him the poker and he then engaged in an elaborate pantomime. ‘Ah!’ he would say, ‘there’s nothing like a poker for picking one’s teeth. Do you agree?’

I agreed so heartily that on observing an elderly uncle engaged in a furtive manoeuvre behind his napkin I said loudly and confidently: ‘Uncle Ellis, Cis says there’s nothing like a poker for picking one’s teeth.’

‘I think, Rose,’ my grandmother said to my mother, ‘that Mr Walker goes too far with the child.’

He gave me my nicest books, made me laugh more often than anybody except my father and never spoiled me. When he found me trying to dragoon one of Susie’s kittens into being harnessed to a shoe box he was so severe that I was stricken with misery and while being bathed that evening burst into tears, tore myself from my mother’s hands and fled, roaring my remorse, to the drawing room where I flung myself, dripping wet, into his astonished embrace.

Nothing could exceed the admiration he inspired.

‘When I am grown up,’ I said warmly, ‘I shall marry you.’

‘Very well, my dear, and you shall have the family pearls.’ He went on the stage and to England. My mother and I met him in London twenty years later and the friendship was taken up as if it had never been interrupted. I don’t think he was ever a very wonderful actor – he always had great difficulty in remembering his lines – but he was fortunate in that he played the leading role in a farce called A Little Bit of Fluff that broke all records by running for about eight years up and down the English, Scottish and Irish provinces, so that he had plenty of time to make sure of the lines. He was entirely a man of the theatre and was, I believe, the happiest human being I have ever known and one of the best loved. When he retired in the 1930s he came out to New Zealand and lived with his unmarried sister and brother in a rambling house full of family treasures. The pearls, he once told me, were kept in a newspaper parcel, on the top of his wardrobe.

In 1943, when I began to produce Shakespeare’s plays for the University of Canterbury, James helped in all of them, sometimes playing small parts. As he grew older and memorizing became more and more of a difficulty, he concentrated upon make-up for which he had a wonderful gift. He was like a gentle spirit of good luck and was much loved by my student-players. When he died, which he did at an advanced age, and with exquisite tact and the least possible amount of fuss, a group of undergraduates asked to carry him and that must have pleased him very much if he was aware of it.

Our other close friend was Mivvy, daughter of that family with monies in Chancery who lived in Dunedin. In age she was almost midway between my parents and me: old enough to be slightly deferred to and young enough to confide in and to cheek. She has told how I burst in upon her privacy with a howl, having committed some misdemeanour. Tears poured from my eyes into my open mouth.

‘Mummy’s cross of me!’ I bawled. ‘But I don’t care, Mivvy, do I?’

Mivvy was the kind of friend whose visits can never be long enough and to whom everyone turns at moments of distress without feeling that they ask too much of her. I hope we didn’t ask too much: I don’t think we did. She was very easy to tease and she was also extremely and comically obstinate. During one of her visits, which we all so much liked, my mother sprained her ankle. Mivvy was determined to administer fomentations, my mother, equally formidable on such issues, was adamant that she should do no such thing. Mivvy set her jaw. The siege of the fat ankle, to my infinite enjoyment, lasted all through one day. Suddenly, at nightfall, my mother yielded. Mivvy, triumphant, became businesslike. Saucepans were set to boil. Linen was torn into strips. Lint and aromatic unguents were displayed. A footbath was prepared. For about an hour my mother suffered her extremity to be alternately seethed and chilled while Mivvy, neatly aproned, bustled vaingloriously. Finally, the ankle was anointed and elaborately bound.

‘There!’ she cried. ‘Now! Doesn’t it feel better?’

‘It feels perfectly all right, thank you, Mivvy dear,’ said my mother and from beneath the hem of her Edwardian skirt displayed the other ankle: still swollen.

‘If there had been any scalding water left,’ Mivvy said, ‘I would have hurled it at you.’

Of all the other grown-up friends and relations who came and went during my earliest childhood the outlines are blurred. There were facetious gentlemen who pretended to be staggered by my voice which was rather deep, and an offensive musical gentleman who insisted, like Svengali, on looking at my vocal cords. Luckily he was not possessed of Svengali’s expertise. Nothing short of deep and remorseless hypnosis would ever have induced me to sing in tune. There was Captain Sykes who became famous, and Mr Parkinson who collected china and committed suicide, there were numbers of ladies who came to my mother’s ‘day’ and to whose ‘days’ I was boringly taken, since I could not be left at home. One of them kept swans on an ornamental pond and these arrogant birds rushed, hissing, at me, when I was sent to play in the garden.

Across the lane in a very big house with a long drive, a lodge at the gates, a horse-paddock, carriages and gigs, a motor, grooms, servants and a nanny, lived a boy and girl with whom I loved to play when my mother visited there. It seemed to me to be a magical place filled with the scent of flowers. The boy, who was asthmatic and often confined to a wheeled chair, was some three or four years my senior: his sister about my own age. This was the beginning of an established friendship. Into the dawn of it, floatingly recollected, come the Duke and Duchess of York (afterwards King George V and Queen Mary) to stay at this house. I remember being lifted on a high evergreen fence to watch my friend’s uncle wire-jumping his horse for the Duke’s entertainment and I remember my parents making ready for a royal reception. Was it on that occasion or a later one that I so laboriously picked violets, bound them, limp and intractable, with a piece of fencing wire out of the gardening shed and presented them to my mother? I see them, wilted, slithering from their confine and weighty to a degree and I see my mother anchoring them in the black lace of her corsage. They must have all disappeared, this way and that, long before the ducal assemblage and I suppose that by some means or other, she rid herself of an embarrassment of stout wire.

I am convinced that recollections of childhood go much further back than we are accustomed to suppose. I realise that mine are based in some measure upon what my parents and friends afterwards told me but for all this I know that many of them have stayed in my conscious memory and that these are the most vivid. The smell, for instance, of newly shot game birds and the glossy slide of their feathers: with this, a shooting hut near the shores of a lake, the song of larks, dry cowpats that were burned in the open fire and, especially, some domestic pigs whose personal hygiene, for some reason, I determined to improve. I remember perfectly well the indignant screams of one of these creatures and the difficulty of retaining my hold on its ear, the depths of which I explored with my own soapy bath-flannel. I have a snapshot taken at the time: it displays my mother graceful and long-skirted, Mivvy and my father in oilskins and sou’westers with shotguns under their arms, the spaniel, Tip, and a stout truculent child of four who is myself.

I have grown, in theory at least, to dislike blood sports but how superb were those sunny mornings when I was allowed to walk behind my father and Tip through the plantation where he and his friends went quail-shooting. On these occasions he was completely and explicitly himself. He would imitate the cry of a Californian cock-quail, make little clucking noises to Tip and even quiver very slightly as Tip did. One had to keep perfectly silent and walk lightly behind the guns. The click of the hammer when he cocked his gun, the sudden whirr of wings, the deafening report and the heady cordite reek of the ejected cartridge-case: these were the ingredients of pure happiness.

When we had followed the guns as far as our picnic place my mother and I would stay there, make a fire of heaven-smelling dry bluegum, and await their return for luncheon. Every now and then we would hear the guns. Shockingly, as one may now feel, my father loved the creatures he shot. Once he described to me very vividly the flight of an English pheasant and the heavy, dark abruptness of its fall. He thought for a moment. ‘Awful, really,’ he said in a surprised voice, ‘isn’t it? Awful, I suppose.’ As a boy, he saw Ellen Terry play Beatrice and of course fell in love with her. ‘When she had to run “like a lapwing, close to the ground” she did it like a henpartridge, trailing her wing to draw attention away from her nest. Beautiful!’ It was the highest praise he could have given Miss Terry.

He was a purist in the management of field sports. When I stumped behind him with a heeled stock in the crook of my arm I had to behave exactly as if it was a real gun: ‘uncocking’ it at fences or gates, ‘unloading’ it before I put it down and never pointing it at anybody. To do otherwise was ‘loutish’. He was dealt one of those strokes of malevolent ill-fortune that so punctually overtook him when he loaded his walking-stick air gun to shoot a fruit-robbing blackbird, was called away and put it in a corner unfired and, for once, forgotten. Weeks later, my mother, who was alone in the house, knocked the gun sideways and it discharged into her middle finger. We had no telephone then and no near neighbours. She bound it up as best she could and waited all day for us to come home. A dreadful episode.

When I was still a small girl I was given a Frankfurt single-bore rifle. I practised, under stern supervision, on suspended tins and cardboard targets until I was a good shot and allowed to go out with the guns. This was wonderful. To kill rabbits was an honourable procedure. And then, on an autumn morning, I wounded a hare. The landscape blackened and cried out against me and that was the end of my active part in field sports.

These expeditions alternated with boating on the quiet river where one glided through unknown people’s gardens, under willows and between the spring-flowering banks of our curiously English antipodean suburbs. The oars clunked rhythmically in their rowlocks, weeping willows dipped and brushed across our faces. If you nibbled the pale young leaves they were surprisingly bitter. Sometimes our keel grated on shingle or sent up a drift of cloudy mud. One trailed one’s fingers and felt grand and opulent. It seems to me that it was always late afternoon on the river.

Until my schooldays came and, with them, camping holidays in the mountains, the great adventure, undertaken on several occasions by my mother and me, was a journey to Dunedin. It lasted all day. Up before dawn, we dressed by lamplight while cocks crew in the darkness beyond the window-pane. We seemed to have taken our house by surprise while it was still leading a night life of its own. In the hall stood our corded boxes and the coats we would wear. Breakfast was a strange hurried business eaten by the light of an oil lamp with a clock on the table. Presently the front door had banged behind us.

My father took us to the station and put us into our carriage (second-class after the financial setbacks). It had wooden benches running lengthways and spittoons along the floor. Now began a period of frightful anxieties. Suppose we stayed too long on the platform and the train suddenly went away without us? Suppose, as I was getting in, my mother should be left behind, mouthing after me on the platform while I was carried rapidly south? Suppose we were in the wrong train and would be swept up through the mountains to Westland or that my father, having established us in our seats, foolishly dallied and was borne away in the train with us and financially ruined.

When we were on our way these apprehensions faded, most of them recurring when my mother decided that we should stretch our legs at the longer stops. The journey became fascinating. We racketed across the Canterbury Plains while in the world outside the Southern Alps advanced, retired and slowly looked over each other’s snowy shoulders, and mad loops of telephone wires dipped and leapt in front of them. ‘Dun-e-DIN. Dun-e-DIN’ said the hurrying train and ‘No-you-DON’T. No-you-DON’T,’ sometimes breaking out into a violent excitable clatter as we roared through a cutting: ‘Rackety-plan. Rackety-plan.’ We crossed great rivers and saw men and vast mobs of sheep on lonely roads. A long day.

There were three little parcels to be opened at appropriately spaced stations. They were always books. There were the lurching hazards of an endless stagger through other carriages and over-shifting footplates in a roaring wind, to the dining car. There were Other People to speculate upon and at evening when one was very tired indeed there was a final treat: my mother’s dressing case to be explored. It was lined with deliciously-smelling leather and fitted with crystal, silver-topped bottles. Soap, eau-de-Cologne with which one’s face was cleaned and freshened. A tiny phial of real attar-of-roses sent out by my grandmother from England. Papier-poudré, which was a little book of leaflets that my mother rubbed over her eau-de-Cologned nose and chin. An ivory-backed brush and comb. A looking glass from which one’s face stared back like a ghost in the murky lamplight. Now we were hurtling round the high cliffs of the Otago coast. If there was a moon outside it shone on the Pacific, far below. Lonely patches of bushland and ranges of hills moved against the sky behind cadaverous nodding reflections of Other People’s faces.

At last, at the end of a lifetime and late at night: Dunedin, the smell of Mivvy’s fur coat and the familiar sound of her voice. The platform heaved under one’s legs. I cannot remember, on any occasion, the drive out to St Clair and suppose I must always have fallen asleep. One entered the house through a conservatory smelling of wet fern. We were near the sea and the last thing one heard was the roar of surf on a lonely coast.

One day, at St Clair, it rained so heavily that I was not allowed to put my nose out-of-doors. Under the dining-room bay-window seat was a system of lockers. Mivvy said they were full of old magazines and suggested that I might like to explore them. They were of two kinds. The Windsor, which was lettuce green with the Castle, I think, in brown, and The Strand with a picture of that thoroughfare on the cover. All day I hunted and devoured, tracing the enchanting series from one edition to the next. The rain beat down, not on the windows of a New Zealand house but across those of a gas-lit upstairs room in a London street. It glistened on the roofs of hansom-cabs and bounced off cobblestones. It mingled with the cries of newsboys and eccentric improvisations upon the fiddle. A solitary visitor was approaching: there was a peremptory double-knock at the street door. Someone came up the stairs and entered.

‘Hullo,’ said Mivvy, looking over my shoulder, ‘you’ve discovered Sherlock Holmes.’

CHAPTER 2 The Hills (#ulink_e6504927-101c-5463-a9cc-7401437a148e)

Miss Sibella E. Ross was a gentlewoman of Highland descent. She was also a cousin of my adored Dundas. Her shape was firm, her bust formidable, her eyes blue and, like her face, surprisingly round. Her teeth were slightly prominent. She lived with her highly respected family in a large house generally known, though not I think to the Rosses, as ‘The Tin Palace’, since it had been constructed in pioneering days from galvanized iron and had a tower. In premises conveniently adjacent, Miss Ross kept school: a select dame school for about twenty children between the ages of six and ten years. Miss Ross’s family and immediate friends called her Tibby and her ex-pupils referred to her school as Tib’s.

To this establishment I was sent when I was, I suppose, six years old. I have no doubt whatever that it was a wise decision but the experience in its initial stages was hellish.

In the morning I was put into a horse-drawn bus where there were already three fellow pupils. We were met at the other end by Miss Irving, the governess at Miss Ross’s, and escorted to school.

‘Good morning, children.’

‘Good morning, Miss Ross. Good morning, Miss Irving.’

For the first time I found myself one of a group of children and, for the first time, I was conscious of being tall for my age. This made the simple business of standing up to answer questions an embarrassing ordeal. Miss Ross had invented an ‘honour’ system which decreed that at the end of the morning each child must stand up and proclaim how many times he or she had spoken unlawfully in class. When my immediate neighbours discovered, with the terrible prescience of children, that this observance frightened me, they determined, gleefully, to enhance its terrors by forcing me to talk. They would hiss questions. If I didn’t answer, they would make jabs at me, for all the world as hens peck at a sick bird. They would peck and jab until I made some kind of response and then stare accusingly at me when the moment for public confession arrived. One could not always ask to ‘leave the room’ at the crucial moment. I cannot think that this was a good practice: it engendered, in a single operation, elements of guilt, fear, loneliness and inferiority, and, indeed, provoked a sort of Freudian extravaganza in the reactions of a little girl who was unprepared for it. The follow-up treatment took place in playtime and was set in hand by the nine-year-olds. They organized themselves and their juniors into something that was called a ‘secret army’ and from it excluded two stalwart little boys and myself. The boys were called Charles and Roderick and were kind. Roderick became a soldier and Charles a man of letters. Both of them left New Zealand. When, on separate occasions and about thirty years afterwards, I met them again, something of the intense gratitude I had felt for them returned. We talked about our first term at Tib’s.

I did not say anything at all about these miseries to my parents but I think my mother must have known that all was not well and decided that I should stick it out. Very properly so, I expect. After all, she was up against the problem of the only child. It is true that by some process of adaptation the picture gradually changed. I was no longer bullied. I formed heartening friendships with other small girls. I toughened.

As time went on I was even given certain responsibilities at Tib’s. When Ian, a fighting boy in a kilt, was brought at eleven o’clock every morning by his nanny, I was one of two sent to take delivery of him in the porch. He yelled, bit and kicked, while his nurse recommended that he should go with the nice young ladies to his lesson. We led him, roaring, to his desk, rather impressed than otherwise by the extremity of his passion. Dick, a fat boy, was more vulnerable and wept sometimes. He was jeered at by my former tormentors and I’m glad to remember that I was sorry for him and didn’t join in. I was out of the wood by that time. Rightly or wrongly, however, I still think that my first term at Tib’s was far from being all to the good. It does not improve the character to be bullied. Children are microcosms of people. Treat them badly for long enough and then give them a little power and they will punctually repeat with greater emphasis the behaviour to which they have been subjected. Fear is the most damaging emotion that can be inflicted on the character of any child and on one already as morbidly prone to inexplicable terrors as I was, the early torments I underwent at Tib’s were pretty deadly. When they moderated and I was no longer in thrall, I reacted predictably. I don’t think that on the whole I was all that much more obnoxious than any other little girl of my age but for a time I became so: bossy, bullying, and secretive, paying back however unconsciously, I am sure, for what had been dealt out to me. I don’t think it lasted very long but it happened and in my old age I still remember and am sorry about it.

Fear can be perhaps the most corrupting of our basic emotions and fear without the possibility of release, the worst of all. The child who has been overtaken by it is a microcosm of the mob. If you rule a people by fear and treat them as an inferior race and then give them power, don’t expect them to use it like angels. You have corrupted them and many of them will abuse it.

One day, while I and other Fendaltonians waited for Miss Irving to put us on the bus, we heard a clatter of hooves in the quiet street and mounted policemen rode splendidly by, followed by a carriage with a crown on the door.

‘The Governor,’ gabbled Miss Irving in a fluster. ‘Girls curtsey and boys bow. Off with your caps. Quick.’

We bobbed and nodded, eyeing each other sideways and then looked up to see the Governor smiling and bowing very pointedly to us. With him was his wife and unless I am at fault, a little girl of about my own age of whom there will be much more to say.

Away rolled the carriage and up came the bus.

One other incident sticks in my memory. Miss Ross, rather ominously smiling, asks her pupils what they wish to be when they grow up. She concentrates upon the boys since the girls are destined for matrimony: an employment not to be examined in detail with propriety. I, however, hold up my hand. ‘I want,’ I venture, ‘to be an artist.’ ‘Ho!’ Miss Ross atrociously says, ‘you’ll never do that, my dear. Your hand shakes.’

I suppose I had attended Miss Ross’s school for about a year when the great change came. We went to live on the hills.

II

When I looked south from the higher branches of my wellingtonia tree in suburbia, I saw, above park, roofs and Cathedral spire, the Port Hills. They were only four miles away but to me they seemed as romantically distant as those snowy Alps that stood to the north beyond the Canterbury Plains. The hills were rounded and suave in outline with occasional craggy accidents. They would be called mountains in England. The tussock that covered them gave them a bloomy appearance as blonde hair does to a living body. I was told that a long time ago they had moved gigantically and heaved themselves into their present form and then grown hard, being the overflow of a volcano.

The crater of this volcano is now a deep harbour into which a hundred and fifteen years ago, sailed the First Four Ships: Sir George Seymour, Randolph, Cressy and Charlotte Jane, bringing the founders of the Canterbury Settlement. These intrepid emigrants landed at the port of Lyttelton, wearing stovepipe hats, heavy suits, crinolines and bonnets. They climbed the Port Hills and reached the summit where, with a munificent gesture, their inheritance was suddenly laid out before them. Whenever I return to New Zealand I like to come home by the hills and still think that an arrival at the pass on a clear dawn is the most astonishing entry one could make into any country. There, as abruptly as if one had looked over a wall, are the Plains, spread out beyond the limit of vision, laced with early mist, and a great river, bounded on the east by the Pacific, on the west by mere distance, and from east to west by a lordly sequence of mountains, rose-coloured where they receive the rising sun.

Gramp came this way in, I think, 1853 and looked down at swamps and a little group of huts and wooden buildings. When he was eighty he still used to go for a Sunday walk on the Port Hills and glare sardonically at the city of Christchurch.

In our Fendalton days there was only a scatter of about twenty houses on the hills. We were lent one of these for a summer holiday – a house amidst tussock with nothing but clear air between it and the foothills of the Alps, forty miles away on the other side of the Plains. It was this visit, I think, that decided our move. My father bought the nose of the same hill; some three-quarters of an acre of ground, already fenced, partly cultivated and set about with baby trees – pinus radiata and limes, not much higher than the surrounding tussock. A sou’-wester is blowing this morning and I look anxiously at the tops of my pines, a hundred feet tall, and hope they have enough sap in their old bodies to withstand the gale.

As soon as the momentous decision was taken, it was communicated to an architect cousin of my mother’s. He at once caused to be set aside a stack of seasoned timber and exposed it to further weathering. It had come out of the mountains, horse-drawn through virgin forest to a bush tramway, or had been floated across a lake and broken down in Westland timber mills. When I made some alterations in this house, the carpenters were unable to drive a nail into the old joists; the wood, they said, was like iron rather than timber.

Perhaps the lease of our house in Fendalton expired before the new one could be built or perhaps there was a delay in the building. For whatever the reason, it was decided that we should camp in tents near the site of our future home and stay there until it was completed. I fancy that we adopted this hardy adventuresome procedure partly because my father considered it would be an advantage if he were at hand to keep an eye on the workmen.

‘You never know,’ he said darkly, ‘with those chaps.’

It was on an early summer’s day that we left Fendalton, seated on top of our tents and boxes in a spring-wagon. My father’s closest friend of those times had a motor-car, one of the first in Christchurch, and had offered to drive us to the hills, but I think the recollection of innumerable breakdowns and hour-long unproductive explorations of its less accessible mysteries decided my mother against this vehicle. She felt that the important thing was to arrive.

So, on what seems to me to have been an interminable journey, we plodded through the borders of Fendalton, round the parks, past a region of drafting-yards and sheep pens where, once a week, livestock was sold, down a long highway and into Wilderness Road, an endless stretch between gorse hedges. It is now a main suburban street. This brought us at last to the hills; to a winding lane, a rough track and our destination. I remember that a hot nor’ wester raged across the plains and when we tried to pitch our bell tents, got inside them and threatened to blow them away like umbrellas. We settled at last upon the sheltered end of a valley, below our section and within sight of the scaffolding that had already been set up.

There we lived throughout the summer. It was the beginning of a new life for all of us.

I continued at Tib’s. Every morning, with my father, I left our tents, climbed up and over a steep hill, or as an alternative, walked a mile round the foot of it to the terminus of a steam-tramway and was carried into Christchurch. In winter I was dressed in a blue serge sailor suit with braid on the collar and skirt and an anchor on the dicky. I also wore a sailor’s cap with HMS Something on it. In summer this nautical motif was carried out in cotton or piqué and the hat was of straw. We had friends living near us in a large house with plantations and a rambling garden – the Walkers: mother, sister and four enormously tall brothers of Dundas, who was now on the stage in Australia. Three of the brothers were bearded, which in those days was unusual, and they were all extremely handsome: Graham, Colin, Alexander, Cecil. I transferred much of my devotion to them, particularly to Colin. Although they were cousins of Miss Ross, they held her so little in awe that on one occasion, finding me alone on the top of the double-decker steam-tram, they rifled my satchel and extracted an exercise book. Alexander gripped my arms while Colin wrote on a virgin page:

Kids may come and kids may go

But Tib goes on forever.

We were not permitted to tear leaves out of our books.

‘You can say we did it,’ they told me. ‘It won’t be splitting. We’d like you to.’

We had to lay our exercises on Miss Ross’s desk. I watched her work her way down the pile until she came to mine. For the first time in my life I saw a woman turn red with anger.

‘Who,’ she asked with classic economy, ‘has done this? Ngaio?’

‘The Boys,’ I faltered, for so I called these bearded giants, and she knew who I meant. With a magnificent gesture she ripped out the page. She then strode to the fire, committed the couplet to the flames and returned to her desk.

‘The hymn,’ she said in a controlled but unnatural voice, ‘We are but little children weak. Open your books.’

Soon after this incident I became ten and had grown out of Tib’s.

By that time our house was almost built. We struck camp, climbed our hill and moved into it.

‘This,’ said my father, referring to the workmen, ‘will hurry them up,’ and indeed I think it must have done so, for they disappeared quite soon.

The new house smelt of the linseed oil with which the panelled walls had been treated and of the timber itself. It was a four-roomed bungalow with a large semi-circular verandah. The living room was biggish. There were recesses in its bronze wooden walls and there was a pleasant balance between them and the windows. My mother had a talent for making, out of undistinguished elements, a kind of harmony in a room. At once it became an expression of herself and the warmth she always lent to human relationships: newcomers used to exclaim on this and often said that they felt as if they had been there before.

At a little distance below the house was a big bicycle shed which, by a heroic concerted effort made by my father and his friends, had been actually hauled up the hill on sleds and then turned over and over until it was brought into position. It was then floored and lined and fitted with bunks like a cabin and became a guest room. From the beginning we loved our house. It was the fourth member of our family and for me, who still lives in it, has retained that character: it has been much added to but I think its personality has not changed. A city has spread across the open country where sheep and cows were grazed: the surrounding hills where I and my friends tobogganed and rode our ponies, are richly encrusted with bungaloid or functional dwellings. An enormous hospital covers the old mushroom-paddock: Cashmere, which is our part of the Port Hills, is now a ‘desirable suburb’. But no skyscraper out on the plains can ever be tall enough to hide the mountains and, strangely enough, the little river Heathcote, where we used to sail on rafts that we built ourselves, has scarcely changed. Children still paddle about on it in home-made craft.

A few miles away from us, round the hills, there lived a horse-coper called Mr McGuinnes. For him my father conceived an admiration (’Decent fellow, McGuinnes’) and with him, soon after we arrived, a bargain was struck. Mr McGuinnes would keep me supplied with a pony which would be grazed in the Top Paddock to which we had access. The pony would be changed from time to time and the outgoing mount sold, I now realize, as having been used by a child. I, who had never bestridden anything but my rocking horse, was madly excited.