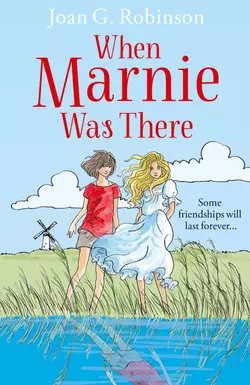

When Marnie Was There

When Marnie Was There

Joan G. Robinson

Anna hasn’t a friend in the world – until she meets Marnie among the sand dunes. But Marnie isn’t all she seems…A major motion picture adaptation by Studio Ghibli, creators of SPIRITED AWAY and ARRIETTY.Sent away from her foster home one long, hot summer to a sleepy Norfolk village by the sea, Anna dreams her days away among the sandhills and marshes.She never expected to meet a friend like Marnie, someone who doesn’t judge Anna for being ordinary and not-even-trying. But no sooner has Anna learned the loveliness of friendship than Marnie vanishes…

CONTENTS

Cover (#u77be5a21-7310-5590-a7c3-5bf6325fe643)

Title Page (#u8c983135-cde4-5a0c-bd2d-70f6ccb3b3ab)

1. Anna (#litres_trial_promo)

2. The Peggs (#litres_trial_promo)

3. On the Staithe (#litres_trial_promo)

4. The Old House (#litres_trial_promo)

5. Anna Follows Her Fancy (#litres_trial_promo)

6. “A Stiff, Plain Thing—” (#litres_trial_promo)

7. “—and a Fat Pig” (#litres_trial_promo)

8. Mrs Pegg’s Bingo Night (#litres_trial_promo)

9. A Girl and a Boat (#litres_trial_promo)

10. Pickled Samphire (#litres_trial_promo)

11. Three Questions Each (#litres_trial_promo)

12. Mrs Pegg Breaks Her Teapot (#litres_trial_promo)

13. The Beggar Girl (#litres_trial_promo)

14. After the Party (#litres_trial_promo)

15. “Look Out for Me Again!” (#litres_trial_promo)

16. Mushrooms and Secrets (#litres_trial_promo)

17. The Luckiest Girl in the World (#litres_trial_promo)

18. After Edward Came (#litres_trial_promo)

19. The Windmill (#litres_trial_promo)

20. Friends No More (#litres_trial_promo)

21. Marnie in the Window (#litres_trial_promo)

22. The Other Side of the House (#litres_trial_promo)

23. The Chase (#litres_trial_promo)

24. Caught! (#litres_trial_promo)

25. The Lindsays (#litres_trial_promo)

26. Scilla’s Secret (#litres_trial_promo)

27. How Scilla Knew (#litres_trial_promo)

28. The Book (#litres_trial_promo)

29. Talking About Boats (#litres_trial_promo)

30. A Letter from Mrs Preston (#litres_trial_promo)

31. Mrs Preston Goes Out to Tea (#litres_trial_promo)

32. A Confession (#litres_trial_promo)

33. Miss Penelope Gill (#litres_trial_promo)

34. Gillie Tells a Story (#litres_trial_promo)

35. Whose Fault Was It? (#litres_trial_promo)

36. The End of the Story (#litres_trial_promo)

37. Goodbye to Wuntermenny (#litres_trial_promo)

Postscript by Deborah Sheppard (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#ulink_80f6d107-2377-5a81-8c70-ed40e338134c)

ANNA (#ulink_80f6d107-2377-5a81-8c70-ed40e338134c)

MRS PRESTON, WITH her usual worried look, straightened Anna’s hat.

“Be a good girl,” she said. “Have a nice time and – and – well, come back nice and brown and happy.” She put an arm round her and kissed her goodbye, trying to make her feel warm and safe and wanted.

But Anna could feel she was trying and wished she would not. It made a barrier between them so that it was impossible for her to say goodbye naturally, with the spontaneous hug and kiss that other children managed so easily, and that Mrs Preston would so much have liked. Instead she could only stand there stiffly by the open door of the carriage, with her case in her hand, hoping she looked ordinary and wishing the train would go.

Mrs Preston, seeing Anna’s ‘ordinary’ look – which in her own mind she thought of as her ‘wooden face’ – sighed and turned her attention to more practical things.

“You’ve got your big case on the rack and your comic’s in your mac pocket.” She fumbled in her handbag. “Here you are, dear. Some chocolate for the journey and a packet of paper hankies to wipe your mouth after.”

A whistle blew and a porter began slamming the carriage doors. Mrs Preston poked Anna gently in the back. “Better get in, dear. You’re just off.” And then, as Anna scrambled up with a mumbled, “Don’t push!” and stood looking down, still unsmiling, from the carriage window – “Give my love to Mrs Pegg and Sam and tell them I’ll hope to get down before very long – if I can get a day excursion, that is—” The train began moving imperceptibly along the platform and Mrs Preston began gabbling – “Send me a card when you get there. Remember they’re meeting you at Heacham. Don’t forget to look out for them. And don’t forget to change at King’s Lynn, you can’t go wrong. There’s a stamped card already addressed in the inner pocket of your case. Just to say you’ve arrived safely – you know. Goodbye, dear, be a good girl.”

Then, as she began running and looking suddenly pathetic, almost beseeching, something softened inside Anna just in time. She leaned out of the window and shouted, “Goodbye, Auntie. Thank you for the chocolate. Goodbye!”

She just had time to see Mrs Preston’s worried look change to a smile at hearing the unaccustomed use of the name “Auntie”, then the train gathered speed and a bend in the line hid her from view.

Anna sat down without looking round, broke off four squares of chocolate, put the rest of the bar in her pocket with the packet of paper handkerchiefs, and opened her comic. Two hours – more than two hours – to King’s Lynn. With luck, if she just looked ‘ordinary’ no-one would speak to her in all that time. She could read her comic and then stare out of the window, thinking about nothing.

Anna spent a great deal of her time thinking about nothing these days. In fact it was partly because of her habit of thinking about nothing that she was travelling up to Norfolk now, to stay with Mr and Mrs Pegg. That – and other things. The other things were difficult to explain, they were so vague and indeterminate. There was the business of not having best friends at school like all the others, not particularly wanting to ask anyone home to tea, and not particularly caring that no-one asked her.

Mrs Preston just would not believe that Anna did not mind. She was always saying things like, “There now, what a shame! Do you mean to say they’ve all gone off to the ice rink and never asked you?” (Or the cinema, or the Zoo, or the nature ramble, or the treasure hunt.) – And, “Why don’t you ask next time? Let them know you’d like to go too. Say something like,’ If you’ve room for an extra one, how about me? I’d love to come.’ If you don’t look interested nobody’ll know you are.”

But Anna was not interested. Not any more. She knew perfectly well – though she could never have explained it to Mrs Preston – that things like parties and best friends and going to tea with people were fine for everyone else, because everyone else was ‘inside’ – inside some sort of invisible magic circle. But Anna herself was outside. And so these things had nothing to do with her. It was as simple as that.

Then there was not-even-trying. That was another thing. Anna always thought of not-even-trying as if it were one long word, she had heard it said so often during the last six months. Miss Davison, her form teacher, said it at school, “Anna, you’re not-even-trying.” It was written on her report at the end of term. And Mrs Preston said it at home.

“It isn’t as if there’s anything wrong with you,” she would say. “I mean you’re not handicapped in any way and I’m sure you’re just as clever as any of the others. But this not-even-trying is going to spoil your whole future.” And when anyone asked about Anna, which school she would be going to later on, and so on, she would say, “I really don’t know. I’m afraid she’s not-even-trying. It’s going to be difficult to know quite what to do with her.”

Anna herself did not mind. As with the other things, she was not worried at all. But everyone else seemed worried. First Mrs Preston, then Miss Davison, and then Dr Brown who was called in when she had asthma and couldn’t go to school for nearly two weeks.

“I hear you’ve been worried about school,” Dr Brown had remarked with a kindly twinkle in his eye.

“I’m not. She is,” Anna had mumbled.

“A-ah!” Dr Brown had walked about the bedroom, picking things up and examining them closely, then putting them down again. “And you feel sick before Arithmetic?”

“Sometimes.”

“A-ah!” Dr Brown placed a small china pig carefully back on the mantelpiece and stared earnestly into its painted black eyes. “I think you are worried, you know,” he murmured. Anna was silent. “Aren’t you?” He turned round to face her again.

“I thought you were talking to the pig,” she said.

Dr Brown had almost smiled then, but Anna had continued to look severe, so he went on seriously. “I think perhaps you are worried, and I’ll tell you why. I think you’re worried because your—” He broke off and came towards her again. “What do you call her?”

“Who?”

“Mrs Preston. Do you call her Auntie?” Anna nodded. “I think perhaps you’re worried because Auntie’s worried, is that it?”

“No, I told you, I’m not worried.”

He had stopped walking about then and stood looking down at her consideringly as she lay there, wheezing, with her ‘ordinary’ face on. Then he had looked at his watch and said briskly, “Good. Well, that’s all right then, isn’t it?” and gone running downstairs to talk to Mrs Preston.

After that things changed quite quickly. Firstly Anna didn’t go back to school, though it was a good six weeks till the end of term. Instead she and Mrs Preston went shopping and bought shorts and sandshoes and a thick rolltop jersey for Anna. Then Mrs Preston had a reply to the letter she had written to her old friend, Susan Pegg, saying yes, the little lass could come and welcome. She and Sam would be glad to have her, though not so young as they was and Sam’s rheumatics something chronic last winter. But seeing she was a quiet little thing and not over fond of gadding about, they hoped she’d be happy. “As you may recall,” wrote Mrs Pegg, “we’re plain and homely up at ours, but comfortable beds and nothing wanting now we’ve got the telly.”

“Why does she says ‘up at ours’?” asked Anna.

“It means at home, at our place. That’s how they say it in Norfolk.”

“Oh.”

Anna had then, surprisingly, slammed the door and stamped noisily upstairs.

“Now whatever did I say to upset her?” thought Mrs Preston, as she put the letter in the sideboard drawer to show to Mr Preston later. She could never have guessed, but Anna had taken sudden and unreasonable exception to being called “a quiet little thing”. It was one thing not to want to talk to people, but quite another to be called names like that. The stamps on the stairs were to prove that she was nothing of the sort.

Remembering this now as she sat in the train pretending to read her comic (which she had long since finished), she suddenly wondered if anyone here might be having the same idea about her. Creasing her forehead into a forbidding frown, she lifted her head for the first time and glared round at the other occupants of the carriage. One, an old man, was fast asleep in a corner. A woman opposite him was making her face up carefully in a pocket mirror. Anna stared, fascinated, for a moment, realised her frown was slipping, and turned to glare at the woman opposite her. She, too, was asleep.

So the ‘ordinary’ face had worked. No-one had even noticed her. Relieved, she turned to the window and stared out at the long flat stretches of the fens, with their single farmhouses standing isolated from each other, fields apart, and thought about nothing at all.

Chapter Two (#ulink_b2594835-ae79-5d18-8017-c4da364a2e7e)

THE PEGGS (#ulink_b2594835-ae79-5d18-8017-c4da364a2e7e)

ANNA KNEW THAT the large, round-faced woman waving a shopping bag at her on the platform must be Mrs Pegg, and went up to her.

“There you are, my duck! Now ain’t that nice! And the bus just come in now. Here, give me your case and we’ll run!”

A single-decker bus, already nearly full, was waiting in the station yard. “There’s a seat down there,” panted Mrs Pegg. “Go you on down, my duck, and I’ll sit here by the driver. Morning, Mr Beales! Morning Mrs Wells! Lovely weather we’re having. And how’s Sharon?”

Anna pushed her way down the bus, glad she was not going to have to sit by Sharon, who was only about four and had fat, red-brown cheeks and almost white fair hair. She never knew what to say to children who were so much younger than she was.

Fields stretched on either side, sloping fields of yellow, green and brown. Ploughed fields that looked like brown corduroy, and cabbage fields that were pure blue. As the bus dashed along narrow lanes Anna saw splashes of scarlet poppies in the hedgerows, and then away to the left, she saw the long thin line of the sea. She felt her heart jump and looked around quickly to see whether anyone else had noticed, but no-one had. They were all talking. They must be so used to it that they didn’t even see it, she thought, staring and staring… and sank into a quiet dream of nothing, with her eyes wide open.

And then they were at Little Overton. The bus went down a long steep hill, Anna saw a great expanse of sky and sea and sunlit marsh all spread out before her, then the bus turned sharply and drew up with a jolt.

“Not far now,” said Mrs Pegg as they picked up the cases and the bus roared away down the coast road. “Sam’ll be expecting us now. He’ll have heard the bus go by.”

“Buses go by all the time at home,” said Anna.

“That must be noisy,” said Mrs Pegg, clicking her tongue.

“I don’t notice it,” said Anna. Then remembering the people on the bus, she asked abruptly, “Do you notice it when you see the sea?”

Mrs Pegg looked surprised. “Me see the sea? Oh no, I never do that! I ain’t been near-nor-by the sea, not since I were a wench.”

“But we saw it from the bus.”

“Oh, that! Yes, I suppose you would.”

They turned in at a little gate no higher than Anna’s hand. The tiny garden was full of flowers and there was a loud humming of bees. They walked up the short path to the open cottage door.

“Here we are, Sam, safe and sound!” said Mrs Pegg, shouting into the darkness, and Anna realised that the large patch of shadow in the corner must be an armchair with Mr Pegg in it. “But we’ll take these things up first,” said Mrs Pegg, and hustled her into what looked at first sight like a cupboard, but turned out to be a small, steep, winding staircase. At the top she pushed open a door, which opened with a latch instead of a handle. “Here we are. It ain’t grand but nice and clean, and a good feather mattress. Come you on down when you’re ready, my duck. I’ll go and put kettle on.”

Anna saw a little room with white walls, a low sloping ceiling, and one small window, so low down in the wall that she had to bend down to see out of it. It looked out on to a small whitewashed yard and an outhouse with a long tin bath hanging on its wall. Beyond that there were fields.

There was a picture over the bed, a framed sampler in red and blue cross-stitch, with the words Hold fast that which is Good embroidered over a blue anchor. Anna looked at this with mistrust. It was the word “good”. Not that she herself was particularly naughty, in fact her school reports quite often gave her a “Good” for Conduct, but in some odd way the word seemed to leave her outside. She didn’t feel good…

Still, it was a nice room, she decided cautiously. Plain but nice. Best of all it had the same smell as she had noticed downstairs. A warm, sweet, old smell – quite different from the smell of polish at home or the smell of disinfectant at school.

She hung up her mackintosh on the peg behind the door, then stood for a moment in the middle of the room, holding her breath and listening. She did not want to go down again but there was no excuse for not. She counted six, gave a little cough, and went.

“Ah, so there you are, my biddy!” said Mr Pegg, peering up at her. “My word, but you’ve growed! Quite a big little-old-girl you’re getting to be. Ain’t she, Susan?”

Anna looked into Mr Pegg’s wrinkled, weatherbeaten face. The small pale blue eyes were almost hidden under shaggy eyebrows.

“How do you do?” she said gravely, holding out her hand.

“A-ah, that’s my biddy,” said Mr Pegg, taking her hand and patting it absent-mindedly. “And how’s your foster-ma keeping, eh?”

Anna looked at Mrs Pegg.

“Your mum, my duck,” said Mrs Pegg quickly. “Sam’s asking if she’s well.”

“My mother’s dead,” said Anna stiffly. “She died ages ago. I thought you knew.”

“Yes, yes, my maid. We knowed all about that,” said Sam, gruffly kind. “And your gran too, more’s the pity.” – Anna’s face stiffened even more – “That’s why I said your foster-ma – Mrs Preston. Nancy Piggott as she used to be. She’s your foster-ma, ain’t she? A good woman, Nancy Preston. Always had a kind heart. She’s a good ma to you, I’ll be bound. Keeping nicely, is she?”

“She’s very well, thank you,” said Anna primly.

“But you don’t like me calling her ‘ma,’ eh? Is that it?” said Sam, his eyes crinkling up at the corners.

“No, of course she don’t!” said Mrs Pegg. “Ma’s old fashioned these days. I expect you call her ‘Mum’, don’t you, love?”

“I call her ‘Auntie’,” said Anna, then mumbled as an afterthought, “sometimes.” It was difficult to know how to explain that she seldom called Mrs Preston by any name at all. There was no need, it wasn’t as if there was a crowd of them at home. Only Mr Preston, who called his wife Nan, and occasionally Raymond, who worked in a bank now he was grown up and always called his mother “Mims”, or occasionally “Ma” to be funny. Anna thought “Mims” was a silly name to call your own mother… She stood there now in front of Mr Pegg’s chair, her eyes troubled, wondering what to say next.

Mrs Pegg came to the rescue. “Any road, I’m sure she’s as good as a mother to you, whatever you call her,” she said in her downright, comfortable way. “And I’m sure when all’s said and done you love her almost as much as if she was your own mother, don’t you?”

“Oh, yes!” said Anna. “More,” and felt a sudden pricking behind the eyelids as she remembered her last sight of Mrs Preston running to keep up with the train and reminding her about the postcard.

“That’s right, then,” said Mrs Pegg.

“I’ve got a postcard to post,” said Anna, her voice coming out suddenly loud – she had been so afraid of it cracking – “will you show me where to post it when I’ve written it?”

Mrs Pegg said yes, of course she would. Anna could write it now in the front room while she got tea ready. “Come you here,” she said, “and I’ll show you.” She wiped her hands down the side of her dress and showed Anna to a room on the other side of the passage. “There’s a little table in here under the windie.”

The tiny room, over-full of furniture, was in half darkness. Mrs Pegg pulled back the curtains and moved a potted palm from the small bamboo table. Then she bent admiringly over a large white bowl full of pink and blue artificial flowers, which half filled the window.

“Wonderful, ain’t they?” she said, blowing the dust from the plastic petals. “Everlasting.”

She gazed at them for a moment, wiping the scalloped edges of the boat-shaped bowl with a corner of her dress, then smiled at Anna and went out, closing the door behind her.

This must be the best room, thought Anna, as she tiptoed carefully over the polished linoleum and slippery hearthrug; like the lounge at home, which was only used at weekends or when there were visitors. But very different.

She sat down at the bamboo table and brought out her postcard addressed to Mrs Stanley Preston, 25 Elmwood Terrace, London, and wrote on the other side, Arrived safely. It’s quite nice here. My room has a sloping ceiling and the window is on the floor. It smells different from home. I forgot to ask can I wear shorts every day unless I’m going somewhere special?

She paused, suddenly wanting to say something more affectionate than the conventional “love from Anna”, but not knowing how to say it.

From the kitchen came the low rumble of voices. Mrs Pegg was saying to Sam, “Poor little-old-thing, losing her mother when she was such a mite – and her granny. It’s a pity she’s so pale and scrawny, and a bit sober-sides as well, but I expect we’ll rub along together all right. She’s taking her time over that postcard, ain’t she? Had I better tell her tea’s ready?”

In the front room Anna was still sucking her pen. Outside, beyond the great boat-shaped bowl that nearly filled the window ledge, she could see glimpses of the tiny garden dreaming in the sunshine, bees still buzzing in and out of the bright flowers. Inside, as imprisoned as the bluebottles that crawled up and down inside the closed window, she sat staring at the plastic hydrangeas, wondering how to tell Mrs Preston that of course she loved her, without committing herself.

By the time Mrs Pegg had come to the front-room door and said, “Tea’s ready, lass!” she had decided on “tons of love” instead of just “love”, and added a P.S. The chocolate was lovely. I’ve saved some for tonight.

That, she knew, would please Mrs Preston without seeming to promise anything. After all, she still might not always feel loving when she got home again.

Chapter Three (#ulink_3cd99cfe-738a-5deb-8799-6d6e0331acc1)

ON THE STAITHE (#ulink_3cd99cfe-738a-5deb-8799-6d6e0331acc1)

“JUST UP THE lane and turn left at the crossroads,” said Mrs Pegg. “Post Office is only a little way up. And the road to the creek’s on the right. Go you and have a look round.” She nodded encouragingly and turned back indoors.

Anna found the Post Office – which to her surprise was a cobbled cottage like the Peggs’, with a flat letterbox in the wall – and posted her card. Then she walked back to the crossroads. She felt free now. Free and empty. No need to talk to anyone, or be polite, or bother about anything. There was hardly anyone about anyway. A farm worker passed her on a bicycle, said “Good afternoon,” and was gone before she even had time to show her surprise. She gave a little skip and turned down the short road to the staithe, and saw the creek lying ahead of her.

There was a salty smell in the air, and from the marsh on the far side of the water came the cries of seabirds. Several small boats were lying at anchor, bumping gently as the tide turned. In that short distance she seemed to have come on another world. A remote, quiet world where there were only boats and birds and water, and an enormous sky.

She jumped at the sudden sound of children’s voices. There was laughter, and shouts of, “Come on! They’re waiting!” and a group of children appeared round the corner of the staithe. Five or six boys and girls of different ages in navy blue jeans and jerseys. Immediately Anna drew herself up stiffly and put on her ‘ordinary’ face.

But it was all right, they were not coming her way. They ran, shouting and jostling each other to a car drawn up at the end of the road, and climbed in. Then the doors slammed, the car reversed, and as it drove past her up to the crossroads she had a glimpse of a man at the wheel, a woman beside him, and the children all bobbing about in the back, talking excitedly.

It was very quiet when they had gone.

“I’m glad,” she said to herself. “I’m glad they’ve gone.

I’ve met enough new people for one day.” But the feeling of freedom had changed imperceptibly to one of loneliness. She knew that even if she had met them they would never have been friends. They were children who were ‘inside’ – anyone could see that. Anyway, I don’t want to meet any more people today, she repeated to herself-hardly realising that Mr and Mrs Pegg were the only people she had spoken to since she left London.

And that had been only this morning! Already the turmoil of Liverpool Street Station, the hurry, the confusion, the nearness of parting – against which she had only been able to protect herself with her wooden face – seemed a hundred years ago, she thought.

She listened to the water lapping against the sides of the boats with a gentle slap-slapping sound, and wondered who the boats belonged to. Lucky people, she supposed. Families who came to Little Overton for their holidays year after year and weren’t just sent here to be got out of the way, or because of not-even-trying, or because people “didn’t quite know what they were going to do with them”… Boys and girls in navy blue jeans and jerseys, like that family…

She walked down to the water’s edge, took off her shoes and socks, and stood with her feet in the water, staring out across the marsh. On the horizon lay a line of sandhills, golden where the sun just caught them, and on either side the blue line of the sea. A small bird flew over the creek, quite close to her head, uttering a short plaintive cry four or five times running, all on one note. It sounded like “Pity me! Oh, pity me!”

She stood there looking and listening and thinking about nothing, drinking in the great quiet emptiness of marsh and water and sky, which now seemed to match her own small emptiness inside. Then she turned quickly and looked behind her. She had an odd feeling suddenly that she was being watched.

But there was no-one to be seen. There was no-one on the staithe, nor on the high grassy bank that ran along to the corner of the road. The one or two cottages appeared to be empty, and the door of the boathouse was shut. To the right the village straggled away into fields, and in the distance a windmill stood alone, silhouetted against the sky.

She turned and looked away to the left. Beyond the few cottages a long brick wall ran along the grassy bank, ending in a clump of dark trees.

And then she saw the house…

As soon as she saw it Anna knew that this was what she had been looking for. The house, which faced straight on to the creek, was large and old and square, its many small windows framed in faded blue woodwork. No wonder she had felt she was being watched with all those windows staring at her!

This was no ordinary house, in a long road, like the one she lived in at home. This house stood alone, and had a quiet, mellow, everlasting look, as if it had been there so long, watching the tide rise and fall, and rise and fall again, that it had forgotten the busyness of life going on ashore behind it, and had sunk into a quiet dream. A dream of summer holidays, and sandshoes littered about the ground-floor rooms, dried strips of seaweed still flapping from an upper window where some child had hung them as a weather indicator, and shrimping nets in the hall, and small buckets, a dried starfish swept into a corner, an old sun hat…

All these things Anna sensed as she stood staring at the house. And yet none of them had she ever known. Or had she…? Once, when she was in the Home, she had been to the seaside with all the other children, but she hardly remembered that. And twice she and the Prestons had been to Bournemouth and walked along the promenade and sat in the flower gardens. They had bathed too, and sat in deck chairs, and been to the concert party at nights.

But this was different. Here there was none of the gay life of Bournemouth. It was as if the old house had found itself one day on the staithe at Little Overton, looked across at the stretch of water with the marsh behind, and the sea beyond that, and had settled down on the bank, saying, “I like this place. I shall stay here for ever.” That was how it looked, Anna thought, gazing at it with a sort of longing. Safe and everlasting.

She paddled along in the water until she was directly opposite to it, and stood, looking and looking… The windows were dark and uncurtained. One of the upper ones was open but no-one was looking out. And yet it seemed to Anna almost as if the house had been expecting her, watching her, waiting for her to turn round and recognise it. And in some way she did.

As she stood there, half dreaming in the water a few feet from the shore, the strange feeling crept over her that this had all happened before. It would have been difficult to explain even what she meant by this, but it was almost as if she were now standing outside of herself, somewhere farther back, watching herself standing there in the water – a small figure in her best blue dress with her socks and shoes in her hand, looking across the staithe at the old house with many windows. She even noticed without concern that the water must have risen slightly, because she could see it lapping at the hem of her dress, making a dark stain round the very edge.

Then the little grey-brown bird flew overhead again, crying, “Pity me! Oh, pity me!” and Anna shook herself out of her dream… She looked down and saw that the water had come up to her knees while she had been standing there. It had even reached the hem of her dress…

“Who lives in the big house by the water?” she asked Mrs Pegg, as they sat drinking cocoa in the kitchen later.

“The big house by the water?” said Mrs Pegg vaguely. “Now which one would that be?”

“The one with blue windows.”

Mrs Pegg turned to Sam, who was eating bread and cheese, spearing pickled onions on the end of his knife and putting them whole into his mouth. “Who lives in the big house with the blue windows, Sam?”

Mr Pegg looked equally vague. He thought for a moment, then said, “Oh, ah, you mean The Marsh House? I don’t know as anyone lives there, do they, Susan?”

Mrs Pegg shook her head. “Not as I know of, but I never go down by the staithe so I wouldn’t know. Didn’t I hear it was going to be bought by a London gentleman? I think Miss Manders at Post Office said so. ‘That’ll need a fair lot of doing up,’ she said. ‘It’s been empty quite a while.’ But maybe that’s not the one.”

“And who are the children in navy blue jeans and jerseys?” asked Anna. “The big family?”

Again Mrs Pegg looked puzzled. “I don’t know of none,” she said. “In the summer holidays there’s lots of children, of course, in their holiday clothes like that. But I don’t know of none now, do you, Sam?”

Mr Pegg shook his head. “Maybe they was just down for the day,” he suggested helpfully.

“Yes, perhaps,” said Anna, remembering the car. But she was secretly disappointed. In her own mind she had already decided that the house by the water was theirs. They had looked the right sort of family to live in a house like that.

“Anything else you’d like to know?” asked Mr Pegg, smiling.

“Yes,” said Anna. “Which is the bird that says, ‘Pity me! Oh, pity me!’”

Mrs Pegg gave her an odd look. “Time you was in bed, my lass,” she said briskly. “It’s been a long day, what with the journey and all. Come you on up and I’ll get you settled in.” She pulled herself out of her chair and carried the cups into the scullery to put them in the sink.

Anna got up and stood looking down at Mr Pegg still eating his bread and cheese. “Goodnight, then,” she said.

“Ah, goodnight, my biddy!” he said abstractedly. “I’m thinking – might that be a sandpiper, do you think? That makes a lonesome little cry, that does. Though I can’t say I ever heared the words afore!” he added with a chuckle.

Chapter Four (#ulink_b883a733-72f4-50e2-ae07-05410f83360b)

THE OLD HOUSE (#ulink_b883a733-72f4-50e2-ae07-05410f83360b)

ANNA THOUGHT OF the house as soon as she awoke next morning. In fact she must have been thinking about it even before she awoke, because by the time she opened her eyes and saw the white, sloping ceiling of her little room, and smelt the old, sweet, warm smell of the cottage, she was saying to herself – still half asleep – “I must hurry It’s waiting for me.” Then she realised where she was.

Thank goodness the journey to Norfolk was over! She must have been dreading it more than she had realised. It had been an unknown adventure looming up ahead, and all her life at home during the past few weeks had been a preparation for it. Now it was over. She was here. And as soon as she could she would go down to the creek again and see the house.

At breakfast Mrs Pegg said, “How about coming into Barnham with me on the bus? I usually goes once a week to the shops, and it would make something for you, wouldn’t it, lass?”

Anna looked doubtful.

“Or maybe you’d like to play with young Sandra-up-at-the-Corner?” Mrs Pegg suggested. “She’s a well behaved, nicely-spoken little lass. I know her mum and I could take you up there.”

Anna looked more doubtful still.

Had she noticed the windmill yesterday, Sam asked. It was a fair way off, and not much to look at when you got there, but that might make something too.

Mrs Pegg rounded on him. That would do nothing of the sort, she said. It was too far for the lass on her own and all along the main road into the bargain.

“Oh, ah, so it is!” said Sam. “Never mind, my biddy. Maybe I’ll take you there myself one day.”

Anna said she did not mind at all, she was quite all right doing nothing. “Really I like doing nothing better than anything else,” she explained earnestly. They both laughed at this, but Anna, determined to be taken seriously, stared hard at the tablecloth, looking as ordinary as she knew how.

“I don’t know that I can do with you sitting around in the kitchen all day, my duck,” Mrs Pegg said doubtfully. “What with the cleaning and the cooking and the washing and Sam being under my feet half the time as it is—”

Anna interrupted. “Oh, no! I meant outside. Can I go down to the creek?”

Mrs Pegg looked relieved. She had been afraid Anna might have wanted to spend the day in the front room, the door of which was always kept closed except on special occasions. Yes, of course Anna could go down to the creek. Or if the tide was out she could walk over the marsh to the beach, and if it was high she could always go down in Wuntermenny’s boat. “As long as you don’t mind not having no company,” she said. Anna assured her she did not mind.

“And just as well, if you go down in the boat with Wuntermenny West,” said Sam. “He can’t abide having to talk.” He stirred his tea ponderously with the handle of his fork and looked hopefully across the table at her. “No doubt you’re thinking that’s a queer name, eh?” he said, smiling.

Anna had not thought about it but said, “Yes,” politely.

“Ah! I’ll tell you how it was, then, since you’re asking,” said Sam. “Wuntermenny’s ma – old Mrs West, that was – she had ten already when he was born. ‘What’re you going to call him, mam?’ they all says, and she says, tired-like, ‘Lord knows! He’m one-too-many and that’s a fact.’ So that’s how it was!” he said, laughing and spluttering into his mug of tea. “And Wuntermenny West he’s been ever since.”

As soon as she could get away, Anna ran down to the staithe. The tide was out and the creek had dwindled to a mere stream. At first she was disappointed when she saw the old house again. It seemed to have lost some of its magic, now that it only looked out on to a littered foreshore instead of a wide stretch of water. But even as she looked, she saw that it was still the same quiet, friendly-faced house. She felt rather as if she had come to visit an old friend, and found that friend asleep.

She scrambled up the bank, clinging on to tufts of grass, and walked slowly along the footpath in front of the house, looking sideways into the windows. She was not sure if she was trespassing, and it was difficult to see clearly without stopping and pressing her face up close against the glass. Suppose someone should be watching, from inside! More than ever now she had the feeling she was spying on someone who was asleep. She moved nearer and saw only her own face staring back at her, pale and wide-eyed.

The Peggs were right, she thought. No-one was living in the house. Nevertheless, it still had a faintly lived-in look, more as if it were waiting for its people to return, than having been deserted. She grew bolder and looked through the narrow side windows on either side of the front door. There was a lamp on a windowsill, and a torn shrimping net was leaning up against the wall. She saw that a wide central staircase went up from the middle of the hall.

That was all there was to see. She slid down the bank again, waded across the creek, and sat for a long time with her chin in her hands, staring across at the house, and thinking about nothing. If Mrs Preston had known she would have been even more worried than she had been, but at the moment she was more than a hundred miles away, pushing a wire trolley round the supermarket. She had forgotten that in a place like Little Overton you can think about nothing all day long without anyone noticing.

Anna did go down to the beach in Wuntermenny’s boat. She found him as unsociable as the Peggs had promised. He was small and bent, with a thin, lined face, and eyes which seemed to be permanently screwed up against the light, looking into the far distance. After the first grunt of recognition he hardly noticed her, so she was able to sit up in the bow of the boat, looking ahead, and ignore him too. This suited her well, but it made her feel lonelier, and she was a little frightened that first afternoon. There seemed such a huge expanse of water and sky, and so little of herself.

Sitting alone on the shore, while Wuntermenny in the far distance was digging for bait, she looked back at the long, low line of the village and tried to pick out The Marsh House. But it was not there! She could see the boathouse, and the white cottage at the corner, and farther away still she could see the windmill. But along where The Marsh House should have been there was only a bluish-grey smudge of trees.

Alarmed, she stood up. It had to be there. If it was not, then nothing seemed safe any more… nothing made sense… She blinked, opened her eyes wider, and looked again. Still it was not there. She sat down then – with the most ordinary face in the world, to show she was quite independent and not frightened at all – and with her knees up to her chin, and her arms round her knees, made herself into as small and tight a parcel as she could, until Wuntermenny came trudging up the beach with his fork and his bucket of bait.

“Cold?” he grunted, when he saw her.

“No.”

She followed him down to the boat, and those were the only two words that passed between them all the afternoon. But as they rounded a bend in the creek and she saw the old house gradually emerge from its dark background of trees, she felt so hot and happy with relief that she nearly said, “There it is!” out loud. She realised now that it had been there all the time. In the distance the old brick and blue-painted woodwork had merely merged into the blue-green of the thick garden trees. She realised something else, too. As they passed close under the windows, on the high tide, she saw that the house was no longer asleep. Again it had a watching, waiting look, and again she had the feeling it had recognised her and was glad she was coming back.

“Enjoy yourself?” asked Mrs Pegg, who was frying sausages and onions in the scullery when Anna returned.

Anna nodded.

“That’s right, my duck. You do what you like. Just suit yourself and follow your fancy.”

“And maybe I’ll take you along to the windmill one day if you’re a good lass,” said Sam.

Chapter Five (#ulink_1872dc5d-1b43-51c1-a4aa-699a16ec7456)

ANNA FOLLOWS HER FANCY (#ulink_1872dc5d-1b43-51c1-a4aa-699a16ec7456)

SO THAT WAS how it was. Anna suited herself and went where she liked. In a way, now, she had three different worlds in Little Overton. The world of the Peggs’ cottage, small and warm and cosy. The world of the staithe, where the boats swung at anchor in the creek and The Marsh House watched for her out of its many windows. And the world of the beach, where great gulls swooped overhead and she sometimes found rabbit burrows in the sand dunes, and the bones of porpoises lying in the fine, white sand. Three separate worlds… but in her own mind the important one was the staithe with the old house by the water.

Gradually, instead of thinking about nothing, she thought about The Marsh House nearly all the time; imagining the family who would live there, what it was like inside, and how it would look in the evenings, in autumn, with the curtains drawn and a big fire blazing in the hearth.

Trudging home across the marsh at sunset one evening she saw the windows all lit up and ran, thinking they must have arrived while she was down at the beach. Perhaps if she hurried she might catch sight of them – the family of children in navy blue jeans and jerseys – before the curtains were pulled. But as she drew nearer she saw that she was wrong. There were no lights in the house. It had only been the reflection of the sunset in the windows.

On another day she saw – or thought she saw – a face pressed close to the window; a girl’s face with long, fair hair hanging down on either side – watching. Then it disappeared. Even when there was clearly no-one there, she still had this curious feeling of being watched. She grew used to it.

The Peggs were glad she had settled down so well. It was good for the lass to be out of doors so much, and provided she came in to meals at reasonable hours, and ate heartily, they saw nothing to worry about. She was, in fact, “no trouble at all,” as Mrs Pegg assured Miss Manders at the Post Office.

A letter came from Mrs Preston in answer to Anna’s card. She was glad Anna was happy, and yes she could wear the shorts every day as long as Mrs Pegg didn’t mind. We’re looking forward so much to hearing all the interesting things you’re doing, she wrote, but if you haven’t time for a long letter, a card will do. Enclosed was a small folded note with “Burn this” written across the outside, and inside, Does the house really smell, dear? Tell me what sort of smell.

Anna, who had quite forgotten her remark about the cottage smelling different from home, wondered vaguely what it meant, burnt the note obediently, and forgot about it. She bought a postcard with a picture of a kitten in a flower pot on it, and wrote on the back, I’m sorry I didn’t write before but I forgot, and on Thursday the Post Office was shut so I couldn’t buy this card. I hope you like it. There was only room for one more line, so she put, I went to the beach. Love from Anna. She added two Xs for good measure, and posted it, well satisfied, never dreaming Mrs Preston might be disappointed at having so little news.

One day Sandra-up-at-the-Corner came to the cottage with her mother. Dinner was late that day, so Anna was caught before she had time to slip out of the scullery door.

Sandra was fair and solid. Her dress was too short and her knees were too fat, and she had nothing to say. Anna spent a wretched afternoon playing cards with her at the kitchen table, while Mrs Pegg and Sandra’s mother sat and talked in the front room. Sandra and Anna knew different versions of every game, Sandra cheated, and they had nothing to talk about.

In the end Anna pushed all her cards over to Sandra’s side and said, “Here you are. Keep them all, then you’ll be sure to win.”

Sandra said, “Ooh, that I never!” went bright pink and relapsed into sulks in the rocking chair. She spent the rest of the afternoon examining the lace edge of her nylon petticoat, and trying to twist her straight, straw-coloured hair into ringlets. Anna read Mrs Pegg’s Home Words in a corner and was thankful when they went.

After that she was less trouble than ever, and stayed out all day in case she might ever have to play with Sandra again.

One afternoon, coming back from the beach where Wuntermenny had been collecting driftwood, and she had been looking for shells, Wuntermenny astonished her by saying his first complete sentence. They were coming up towards the staithe when he suddenly jerked his head over his shoulder and said in a gruff, casual voice, “Reckon they’ll be down soon.”

Anna sat up in surprise. “Who will?”

Wuntermenny jerked his head again, over towards the shore. “Them as’ve took The Marsh House.”

“Will they? When? Who are they?”

Wuntermenny gave her a look of deep, pitying scorn and shut his mouth tightly. Too late she realised her mistake. She had been too eager, asked too many questions. If she had just looked sleepily uninterested he would probably have told her all she wanted to know. Never mind, she would soon find out. She might even ask the Peggs.

But on second thoughts she decided not. They might think she wanted to make friends with the people, and that was not what she wanted at all. She wanted to know about them, not to know them. She wanted to discover, gradually, what their names were, choose which one she thought she might like best, guess what sort of games they played, even what they had for supper and what time they went to bed.

If she really got to know them, and they her, all that would be spoiled. They would be like all the others then – only half friendly. They, from inside, looking curiously at her, outside – expecting her to like what they liked, have what they had, do what they did. And when they found she didn’t, hadn’t, couldn’t – or what ever it was that always cut her off from the rest – they would lose interest. If they then hated her it would have been better. But nobody did. They just lost interest, quite politely. So then she had to hate them. Not furiously, but coldly – looking ordinary all the time.

But this family would be different. For one thing they would be living in ‘her’ house. That in itself set them apart. They would be like her family, almost – so long as she was careful never to get to know them.

So she said nothing to the Peggs about what Wuntermenny had said, and hugged to herself the secret that they would soon be coming to The Marsh House. And as the days went by she followed her fancy in her imagination as well, until the unknown family became almost like a dream family in her own mind – so determined was she that they should not be real.

Chapter Six (#ulink_8f3ce2e4-52d7-5ec9-a1e0-d6df75f89c46)

“A STIFF, PLAIN THING—” (#ulink_8f3ce2e4-52d7-5ec9-a1e0-d6df75f89c46)

ONE EVENING ANNA and Wuntermenny were coming home in the boat on a particularly high tide.

The sky was the colour of peaches, and the water so calm that every reed and the mast of every boat was reflected with barely a quiver. The tide was flooding, covering quite a lot of the marsh, and as they drifted upstream Anna had been peering down into the water, watching the sea lavender and the green marsh weed, called samphire, waving under the surface. Then, as they rounded the last bend, she turned as she always did, to look towards The Marsh House.

Behind it the sky was turning a pale lime green, and a thin crescent moon hung just above the chimney pot. They drew nearer, and then she saw, quite distinctly, in one of the upper windows, a girl. She was standing patiently, having her hair brushed. Behind her the shadowy figure of a woman moved dimly in the unlighted room, but the girl stood out clearly against the dark, secret square of the window. Anna could even see the long pale strands of her hair lifted now and then as the brush passed over them.

She turned quickly and glanced at Wuntermenny, but he was looking along the staithe towards the landing place and had seen nothing.

Anna ran home, turned the corner of the lane, then stopped. Mrs Pegg and Sandra’s mother were standing talking at the cottage gate – their faces brick red in the orange light of the sunset. Mrs Stubbs was a big woman with bright black eyes and a rasping voice. Anna did not want to meet her again, so she stepped back into the dusky shadow of the hedge, and waited.

“You’ll be coming over to mine tonight, won’t you?” Mrs Stubbs was saying. “My sister’s over from Lynn and she’s brought them patterns.”

“Has she now!” Mrs Pegg sounded eager, then hesitated. “Well, there’s the child –” she added doubtfully.

“Oh, I forgot about her! She’s a bit of an awkward one, ain’t she? My Sandra said—” the voice was lowered and Anna missed the rest of the sentence.

“Yes, well – maybe…” said Mrs Pegg, “but I don’t hold with interfering between children. If they don’t want to make friends, then let ’em alone, I’d say.”

“My Sandra was quite willing,” said Mrs Stubbs. “Put on her best dress, she did, and her new petticoat, but she says to me after, ‘Mum,’ she says. ‘Never did I see such a stiff, plain thing—’”

“Yes, well,” Mrs Pegg interrupted mildly, turning towards the gate, “don’t tell me what she said, for as true as I’m standing here, I’d rather not know.” She closed the latch with a click. “Any road, she’s as good as gold with us,” she added – defiantly now she was inside the gate. “But perhaps we won’t come tonight and thank you all the same for asking.”

“Just as you please,” said Mrs Stubbs. “Shall you be at the Bingo tomorrow night?”

“Yes, that’s right. I’ll see you at the Bingo tomorrow,” said Mrs Pegg, and went indoors.

Anna waited until Mrs Stubbs had gone, then slipped in by the back door. Mrs Pegg was bustling about, fetching bread and butter from the pantry. She looked a little flushed and her hair was untidy but she greeted Anna as usual.

“Ah, there you are, lass! Sit you down now. Tea’s just ready.” She turned to Sam as he put down his paper and drew up a chair. “What’s on telly tonight?” she asked.

Sam looked surprised. “Weren’t you going up to the Corner tonight? I thought Mrs Stubbs said her sister was there?”

Mrs Pegg shook her head. “Not tonight. That can wait.” She glanced at Anna, then said, “Listen, love, next time you see Mrs Stubbs or Sandra, try and be a bit friendly-like, will you?”

Anna blurted out, “Is it because of me you’re not going?”

“Of course not, what an idea!” Mrs Pegg made a good pretence of looking surprised. “Only maybe they’ll ask you up to theirs one day, if you look friendly-like. That might make a bit of a change for you, eh?”

Anna mumbled, “I like it better here,” but Mrs Pegg might not have heard because she was again asking Sam what was on the telly.

“Boxing,” he said, looking slightly guilty, “but you won’t like that.”

“Oh, well,” said Mrs Pegg, “I’ll like it tonight and lump it. And that’ll make a bit of a change too.”

“It will and all!” said Sam, chuckling and turning to wink at Anna. “She’ll never look at boxing, no matter what I say—” But Anna had gone.

Upstairs in her room she sat on the edge of her bed, hating herself and hating everyone else. It was her fault that Mrs Pegg wasn’t going to the Stubbs’ tonight. Sandra, that fat pig of a girl, had called her a stiff, plain thing. Mrs Pegg – kind Mrs Pegg – hadn’t wanted to listen and she had said she was as good as gold. But she wasn’t going to the Stubbs’ because of Anna, and that was stupid. She was silly and stupid. So was Sam, with his silly boxing. And as for Mrs Stubbs—! Mrs Pegg should have gone anyway, then Anna wouldn’t have felt so guilty. She looked at the framed sampler on the wall and hated that too. Hold fast that which is Good – but nothing was good. Anyway what did it mean? Was the anchor supposed to be good? But you couldn’t walk about holding an anchor all day long, even if you had one. You’d look sillier than ever.

She turned the picture to the wall and went over to the window. Kneeling on the floor she looked out across the fields, pink in the glow of the sunset, and let hot, miserable tears run down her face. Nothing was any good – Anna least of all.

For a moment she almost wished she was at home, then she remembered all the misery of that last half term before she came away. No, it was better here.

She knelt there, listening to the now familiar country sounds; voices from the fields, the distant rattle of farm machinery, and the roar of the last bus from Barnham as it came tearing down the hill and disappeared along the coast road. Then there was silence – only the odd cry of a bird from the marsh, and little ticking sounds that she could never quite identify. At night the silence fell like a blanket. When a dog barked you could hear it from one end of the village to the other.

Gradually, as the tears dried on her cheeks and the fields darkened, and the quietness became even quieter, she forgot about Mrs Pegg not going to the Stubbs’, and thought instead about the girl she had seen in The Marsh House. Why had she been having her hair brushed? It had been too early for bedtime. She had been wearing something light, surely not a nightdress so early in the evening? She had not been a very little girl. She had looked about the same age as Anna…

The thought struck her that the girl would have been dressing for a party. Yes, that was it. She would have been standing there in her petticoat, having her hair brushed, with a white party dress laid out on the bed nearby, and a pair of slippers on the floor – silver slippers. And now, with dusk already falling, she would be coming down the central staircase into the hall. There would be bright lights and there would be dancing…

Kneeling quite still by the open window, Anna sank into a dream, seeing it all as if she herself were there – not inside, but watching from the footpath outside. Through the narrow side window she could see the bright dresses passing and repassing. The faces of the people were vague, but she could tell they were laughing. Then all at once she saw them turn one way, to watch the fair-haired girl as she came down the great staircase, stepping carefully in her silver slippers.

And now, it seemed to Anna, she was farther away. She was standing on the marsh on the far side of the water, and seeing the lights from the windows reflected in the creek, a wavering pattern of gold. The sound of music came over the water, only faintly and mingling with the soughing of the wind in the marram grasses…

So clearly did she see it all in her imagination that she felt it must be true – must be happening now. Getting to her feet she closed the window, then, stiff with kneeling so long, and trembling, partly with cold and partly with excitement, she limped softly across the room and downstairs. As she slipped out of the door she heard the shouts and roars of the television boxing match going on in the kitchen, and marvelled how grown-ups could spend an evening watching anything so dull.

She hurried down to the creek, running barefoot, her ears straining for the sounds of the music, her eyes straining to catch a glimpse of the lights which by now she felt sure would be spreading right across the creek. Then she turned the corner and stopped dead.

The creek was in darkness, the cottages and the boathouse were in darkness, and along where The Marsh House stood, only the black background of trees showed up against the sky. There was not a light anywhere, except for the distant revolving beam of a lightship which made an arc of light across the sky every half minute, then disappeared. There was no music either, only the soft lapping of water against the sides of the boats, and the sudden, feverish rattling of rigging slapping against masts…

She stood there for a moment, amazed. Then from far across the marsh came the mad, scary, scatter-brained cry of a peewit, and she turned and fled back to the cottage.

Chapter Seven (#ulink_7a5dfd66-aaa7-5d64-98e5-37c63d1123c0)

“—AND A FAT PIG” (#ulink_7a5dfd66-aaa7-5d64-98e5-37c63d1123c0)

THAT WAS SILLY, Anna thought next morning. Because she had been miserable about the way things really were, she had tried to make something imaginary come true instead. But that never worked.

She went down to breakfast thinking she would try and make it up to Mrs Pegg for missing her outing, by being helpful in some way.

“Shall I wash up?” she asked casually, standing beside her at the sink after breakfast.

“Lord no, my duck! That’s kind of you, but I’m used to it.” Mrs Pegg seemed touched, and a little surprised. “I’ll tell you what, though. You can do something for me. Pick me some sanfer when you’re down on the marsh, and on your way back pop in and ask Miss Manders if she’s any spare jam jars. If she has, get some vinegar as well. Sam’s a fancy to have some pickled sanfer again.”

The Peggs always called samphire “sanfer”, so Anna knew what she meant. She set off with the big, black plastic shopping bag and went down to the creek.

It was one of those still, grey, pearly days, with no wind, when sky and water seemed to merge into one, and everything was soft and sad and dreamy. Sam had said at breakfast that in weather like this his rheumatics were like Old Nick screwing the pincers on him, but Anna liked these days better than any. They seemed to match the way she was feeling.

The tide was out, and she paddled across to the other side without even turning to look at the old house. There was a purple haze over the marsh, which was the sea lavender coming out, and she thought she might pick some of that, too, when she had finished with the samphire.

For two hours she slithered about on the marsh, jumping over the streams, sometimes landing on springy turf and sometimes sinking into soft patches of black mud; hearing only the distant cry of the little grey-brown birds calling “Pity me! Oh, pity me!” from a long way off. The samphire was green and juicy, though it only tasted of sea salt, she thought. She picked until the bag was full, then, deciding to leave the sea lavender for another day, she set off towards the Post Office.

Miss Manders looked at Anna over her spectacles and gave her a thin, tight smile. Anna gave her Mrs Pegg’s message, hearing, at the same time, someone come in behind her. Out of the corner of her eye she saw that it was Sandra and another girl.

“—and Mrs Pegg says if you can spare the jam jars, please can she have some vinegar as well,” she finished, aware that the two girls were looking at her sideways and that Sandra was whispering. The younger girl burst into a peal of laughter, then there was some shushing and quiet scuffling behind her.

When Miss Manders had gone out at the back to find the jars, Anna turned round with every intention of looking friendly, if she could. But try as she would she could not catch Sandra’s eye. She was now standing with her back to Anna, pretending to look at some postcards in a rack, and talking to her friend in a low voice. Again the other girl laughed, half glancing over her shoulder at Anna. Then Sandra, looking into a crate of ginger beer bottles, said loudly in an affected voice, “Ho, and hif you ’ave any old bottles to spare, kindly fill them with ginger beer, will you?”

They both laughed immoderately at this, and Anna stood there feeling awkward, but she was determined to make Sandra look at her. She walked over towards her, intending to say “Hello,” but at that minute Miss Manders came back.

“Tell Mrs Pegg I have got some,” she said to Anna, “but I’ll have to look them out later. They’re away at the back.”

Anna said, “Thank you,” and moved towards the door. Then she remembered the vinegar. She went back and stood uncertainly behind the two girls, waiting while Miss Manders served them with two ice-cream wafers. Then the telephone rang, and Miss Manders, thinking Anna was only waiting for the others, shut the till and went to answer it. Sandra turned round and faced Anna.

“Why are you following me about?” she demanded.

“I’m not.”

“Yes, you are. Wasn’t she?”

The other girl nodded, licking delicately round the edges of her ice-cream. Sandra put out her tongue and kept it out, staring hard at Anna, then, very slowly and deliberately, without shifting her gaze, she lifted her ice-cream and ran it down the sides of her tongue.

Anna stared back, noting with pleasure that the ice-cream from the lower end of the wafers was about to dribble down the front of Sandra’s dress. But she showed no sign.

“I was only going to say hello—” she began coldly, but Sandra interrupted before she could finish her sentence.

“Go on, then, call me, call me!”

“What do you mean, call you?”

“Call me what you like. I don’t care! I know what you look like, any road.” She turned and whispered to her companion, giggling, and the blob of ice-cream fell trickling down her dress.

Anna looked at her scornfully. “Fat pig,” she said, and turned to go out.

But Sandra barred her way. She had just seen the ice-cream on her dress and was scrubbing at it furiously. “Now I’ll tell you!” she said, spluttering. “Now I’ll tell you what you look like! You look like – like just what you are. There!”

This startled Anna. She walked out of the Post Office – quite forgetting the vinegar – with all the appearance of not having heard, but knowing that Sandra had dealt her an underhand blow. Like “just what you are” she had said. But what was she?

Angrily she walked down the lane, tearing at the poppies in the hedgerow, and crumpling them in her hot hand until they became slimy. She knew what she was only too well. She was ugly, silly, bad tempered, stupid, ungrateful, rude… and that was why nobody liked her. But to be told so by Sandra! She would never forgive her for that.

She left the bag of samphire behind the outhouse, and went in to dinner looking sulky.

Mrs Pegg did not know yet about her meeting Sandra, but she would hear soon enough. Mrs Stubbs would make sure of that. She would tell her that Anna had called Sandra a fat pig – and this after Mrs Pegg had specially said “try and look friendly”! Anna prepared herself in advance for the moment when Mrs Pegg should hear about it, by looking surly and answering all her kindly questions in monosyllables.

“Ready for your dinner, love?”

“Yes.”

“Liver today. Do you like that?”

“Quite.”

“What’s up, my duck. Got out of bed the wrong side after all, did you?”

“No.”

“Never mind, then. You like bacon too – and onions?”

“Yes.”

Mrs Pegg hovered beside her with the frying pan. “A please don’t hurt no-one neither,” she said a little tartly.

“Please,” said Anna.

“That’s a maid! Now sit you down and enjoy that. Maybe you’ll feel better after.”

Anna ate her meal in silence, then got up to go. Sam reached out a hand as she passed his chair. “What ails you, my biddy?”

“Nothing.”

She ignored the hand, pretending not to see it, but in that instant she longed to flop down on the floor beside him and tell him everything. But she could not have done that without crying, and the very idea of such a thing appalled her. Anyway they would miss the point somehow. Mrs Preston always did. She was always kind, but also she was always so terribly concerned. If only there was someone who would let you cry occasionally for no reason, or hardly any reason at all! But there seemed to be some conspiracy against that. Long ago in the Home, she remembered, it had been the same. She could not remember the details, only a picture of herself running, sobbing across an enormous asphalt playground, and a woman as big as a mountain – as it had seemed to her then – swooping down on her in amazement, crying, “Anna! Anna! What ever are you crying for?” As if it had been a quite outrageous thing to do in that happy, happy place.

All this passed through Anna’s mind as she passed Sam’s chair and went through into the scullery to put her empty plate into the sink. On no account must she cry. It would be too silly to say she was upset because she had called Sandra a fat pig. Or because Sandra had said she looked like just what she was. It was not just that, anyway. Mrs Pegg was going to hate her as soon as she heard about it, so it would be unfair to let her go on being kind now, not knowing.

She hardened her heart and went out by the back door, slamming it behind her.

The tide was far out and the creek a mere trickle. She glanced along the staithe towards The Marsh House, wondering if she might catch a glimpse of the girl she had seen last night, but there was no-one there. The house seemed asleep. She crossed the creek and walked over the marsh, paddling across the creek again on the far side, and came to the beach. There, with only the birds for company, she lay in a hollow in the sandhills all the long, hot afternoon, and thought about nothing.

Chapter Eight (#ulink_aef3f7a3-e089-5c26-8ac4-cf3e37c9bd42)

MRS PEGG’S BINGO NIGHT (#ulink_aef3f7a3-e089-5c26-8ac4-cf3e37c9bd42)

IT WAS MRS Pegg’s Bingo night. Anna had forgotten until she came back several hours later to find Mrs Pegg already changed into her best blouse, and rummaging in the dresser drawer for a small pot of vanishing cream which she kept there for special occasions.

“Your tea’s keeping hot over the saucepan,” she said to Anna. “Turn off the gas when you’ve finished, there’s a good lass. Sam’s up to the Queen’s Head for a game of dominoes, so he had his early with me. Now where’s that pot of cream gone? It really do seem like vanishing cream sometimes. Ah, there it is!” She pulled it out from among an assortment of kettle holders, paper bags and tea cloths, and began dabbing her face haphazardly. “Now where are me shoes? I could have swore I brought them down. You won’t forget to turn the gas off, will you, love? I’d better go and find me shoes.” She lumbered off to find another pair.

Anna was glad. No-one had been bothering about her. No-one had been wasting their time worrying whether she was happy or not. Her bad temper of dinner-time had been forgotten. Now Bingo and dominoes were in the ascendant. The Peggs were like that; they really did forget, not just pretend to. So she, too, was free – free to cut herself right off from them. From the Peggs, the Stubbs, and everyone else. It was a relief not to feel she was being watched and worried over all the time… In any case, by tomorrow Mrs Pegg would probably have heard all about her meeting with Sandra… When Mrs Pegg came hobbling back in her best shoes (which were exactly the same as her ordinary ones, only tighter), Anna was looking out of the window. And when Mrs Pegg finally went to the door, saying, “Well, I’m off at last, my duck. Make yourself some tea if you’ve a mind,” she only glanced round and said, “Goodbye” in a polite, formal voice.

And now Anna was alone. The clock ticked on the dresser, and the saucepan on the stove bubbled gently. She discovered her “tea” – a mountain of baked beans alongside a kipper, and a sticky iced bun – and ate through it solemnly, still wrapped around in this quiet, untouchable state of not-caring. Then she turned off the gas, put the dishes on the draining board, and went out again.

It was dusk and the tide had come in. It must have come in very quickly while she was having her tea, for the staithe was now covered with a smooth sheet of silvery water, which came up to within a few feet of the bank. A small boat was tied to a post, floating in shallow water barely a foot from the shore. It had not been there before, she was sure. She could not have failed to notice it lying on its side as it would have been then, and so far up on the beach. It was a beautiful little boat, almost new and the colour of a polished walnut.

She went closer and looked inside.

A silver anchor lay in the bow, its white rope neatly coiled, and a pair of oars were lying ready in the rowlocks. It looked as if someone had just stepped ashore and would be back any minute. She looked round quickly but there was no-one to be seen. Nor had anyone come up the road for at least the last ten minutes. If they had, Anna would have seen them. And yet, more and more, she had the feeling that the boat was waiting for someone; not just lying idle like the others. After all, it was not moored, the anchor was still in the bow, and the rope was only twisted twice round the post. It almost seemed as if it might be waiting for her.

She glanced round again, took off her plimsolls and then, without pausing to think, pulled the boat towards her and stepped inside. The sudden movement tugged at the rope and loosened it. Anna sat down, pulled it in, and took hold of the oars. She had never rowed a boat before in her life – though she did remember once taking an oar with Mr Preston when they had been in Bournemouth, and she remembered, too, the golden rule he had impressed upon her about never standing up in a boat – but beyond that she had no experience at all. And yet now she felt perfectly confident.

Carefully she dipped one oar, then the other, then both together in small quiet strokes, and found herself moving steadily away from the post and along the shore. She was moving along towards The Marsh House. Almost without realising it she had turned the boat in that direction.

It was utterly calm and dreamlike on the water. She forgot to row and leaned forward on the oars, looking at the afterglow of the sunset, which lay in streaks along the horizon. A sandpiper – was it a sandpiper? – called, “Pity me!” from across the marsh, and another answered, “Pity me! Oh, pity me!”

She sat up suddenly, realising that although she had stopped rowing she was still moving. The bank to her left was slipping away fast, and already she was drifting past the front of The Marsh House. She saw lights in the first-floor windows, then she made a sudden grab for the oars. Over her shoulder she had just seen that she was heading straight for the corner where the wall jutted out into the water. If she was not quick she would bump into it. She plunged the left oar into the water, hoping to turn the boat, but the oar went in flat and she nearly fell over backwards. At the same moment a voice sounded almost in her ear – a high, childish voice with a tremble of laughter in it.

“Quick! Throw me the rope!”

Chapter Nine (#ulink_eb7c08c6-0ab5-5b50-9380-96e3da3420ca)

A GIRL AND A BOAT (#ulink_eb7c08c6-0ab5-5b50-9380-96e3da3420ca)

ANNA THREW THE rope, felt the jerk as it tightened, and the boat was drawn in until it bumped gently against the wall.

She looked up. Standing above her, at the top of what she now saw was a flight of steps cut into the wall, was a girl. The same girl as she had seen before. She was wearing a long, flimsy dress, and her fair hair fell in strands over her shoulders as she bent forward, peering down into the boat.

“Are you all right?” she whispered.

“Yes,” said Anna, in her ordinary voice.

“Ssh!” The girl lifted a finger to her lips. “Don’t let anyone hear. Can you climb out?”

Anna climbed out, the girl tied the rope to an iron ring in the wall, and they stood together at the top of the steps, eyeing each other in the half light. This is a dream, thought Anna. I’m imagining her, so it doesn’t matter if I don’t say anything. And she went on staring and staring as if she were looking at a ghost. But the strange girl was looking at her in the same way.

“Are you real?” Anna whispered at last.

“Yes, are you?”

They laughed and touched each other to make sure. Yes, the girl was real, her dress was made of a light, silky stuff, and her arm, where Anna touched it, was warm and firm.

Apparently the girl, too, had accepted Anna’s reality. “Your hand’s sticky,” she said, rubbing her own down the side of her dress. “It doesn’t matter, but it is.” Then she added, wonderingly, “Are you a beggar girl?”

“No,” said Anna. “Why should I be?”

“You’ve got no shoes on. And your hair’s dark and straggly, like a gipsy’s. What’s your name?”

“Anna.”

“Are you staying in the village?”

“Yes, with Mr and Mrs Pegg.”

The girl looked at her thoughtfully. In the fading light Anna could barely see her features, but she thought that her eyes were blue with straight dark lashes.

“I’m not allowed to play with the village children,” the girl said slowly, “but you’re a visitor, aren’t you? Anyway, it makes no difference. They’ll never know.”

Anna turned away abruptly. “You needn’t bother,” she said.

But the girl held her back. “No, don’t go! Don’t be such a goose. I want to know you! Don’t you want to know me?”

Anna hesitated. Did she want to know this strange girl? She hardly knew the answer herself. But to get things straight first, she said, “My hands are sticky because I had a bun for tea, and my hair’s untidy because I haven’t brushed it since this morning. I have got some shoes, but I left them on the beach. So now you know.”

The girl laughed and pulled her down beside her on to the top step. “Let’s sit here, then they won’t see us if they look out. But we must talk quietly.” She glanced over her shoulder, up towards the house. Anna followed her look. “They’re all up there,” she whispered. “That’s the drawing-room where the lights are.”

There was a sudden sound of a window opening just above their heads. The girl ducked down and put her hand on Anna’s shoulder, making her duck down too. Silently they eased their way down a step, and sat huddled together, heads bent, the girl holding Anna’s arm in a tight grip. Above them a woman’s voice said, “How beautiful the marsh is at night! I could sit here for ever.” The girl gave a shiver of excitement and ducked lower. They held hands, laughing silently, seeing only each other’s white teeth shining in the darkness.

“Shut the window,” said a man’s voice from above. There was a sound of music from inside the room, then a burst of laughter and other voices. Someone called, “Marianna, come and dance!” Then the woman’s voice, right overhead, said, “Yes, in a minute. By the way, where’s the child?”

The girl flung her arm round Anna’s waist and they held their breath. Anna did not remember ever being so close to anyone before. Then the man’s voice said, “In bed, I should hope. Come on, do shut the window.” There was a click as the window closed again, then silence. From the marsh came again the sound of the little grey-brown bird calling, “Pity me! Oh, pity me!” A slight breeze ruffled the water and the boat rocked gently below them. The girl let go of Anna’s hand.

“Was it you they were talking about?” Anna whispered. She nodded, laughing quietly. “Then why are you in that dress? Weren’t you meant to be at the party?”

“That was earlier. It’s late now. I’m supposed to be in bed. You heard. Are you allowed to stay up all night?”

Anna shook her head. “No, I’ll have to go soon anyway—” she paused, remembering the way she had come. “Is it your boat?” she whispered.

“Yes, of course. I left it on purpose for you. But I didn’t know you couldn’t row!” They chuckled together in the darkness, and Anna felt suddenly tremendously happy.

“How did you know I was here?” she asked. “Have you seen me?”

“Yes, often.”

“But I thought you’d only just come!”

The girl laughed again, then clapped her hand over her mouth. She leaned towards Anna and whispered in her ear, so that it tickled. “Silly, of course not! I’ve been here ages.”

“How long?” Anna whispered back.

“A week at least,” there was a teasing note in her voice. “Ssh! Come down now and I’ll row you back.”

In the boat Anna said, “Have you been watching me?”

The girl nodded. “Hush! Voices carry over the water.”

Anna lowered her voice. “I had a feeling you were. Sometimes I even looked round to see who it was, looking and looking like that – but you were never there.”

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/joan-robinson-g/when-marnie-was-there/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Joan G. Robinson

Anna hasn’t a friend in the world – until she meets Marnie among the sand dunes. But Marnie isn’t all she seems…A major motion picture adaptation by Studio Ghibli, creators of SPIRITED AWAY and ARRIETTY.Sent away from her foster home one long, hot summer to a sleepy Norfolk village by the sea, Anna dreams her days away among the sandhills and marshes.She never expected to meet a friend like Marnie, someone who doesn’t judge Anna for being ordinary and not-even-trying. But no sooner has Anna learned the loveliness of friendship than Marnie vanishes…

CONTENTS

Cover (#u77be5a21-7310-5590-a7c3-5bf6325fe643)

Title Page (#u8c983135-cde4-5a0c-bd2d-70f6ccb3b3ab)

1. Anna (#litres_trial_promo)

2. The Peggs (#litres_trial_promo)

3. On the Staithe (#litres_trial_promo)

4. The Old House (#litres_trial_promo)

5. Anna Follows Her Fancy (#litres_trial_promo)

6. “A Stiff, Plain Thing—” (#litres_trial_promo)

7. “—and a Fat Pig” (#litres_trial_promo)

8. Mrs Pegg’s Bingo Night (#litres_trial_promo)

9. A Girl and a Boat (#litres_trial_promo)

10. Pickled Samphire (#litres_trial_promo)

11. Three Questions Each (#litres_trial_promo)

12. Mrs Pegg Breaks Her Teapot (#litres_trial_promo)

13. The Beggar Girl (#litres_trial_promo)

14. After the Party (#litres_trial_promo)

15. “Look Out for Me Again!” (#litres_trial_promo)

16. Mushrooms and Secrets (#litres_trial_promo)

17. The Luckiest Girl in the World (#litres_trial_promo)

18. After Edward Came (#litres_trial_promo)

19. The Windmill (#litres_trial_promo)

20. Friends No More (#litres_trial_promo)

21. Marnie in the Window (#litres_trial_promo)

22. The Other Side of the House (#litres_trial_promo)

23. The Chase (#litres_trial_promo)

24. Caught! (#litres_trial_promo)

25. The Lindsays (#litres_trial_promo)

26. Scilla’s Secret (#litres_trial_promo)

27. How Scilla Knew (#litres_trial_promo)

28. The Book (#litres_trial_promo)

29. Talking About Boats (#litres_trial_promo)

30. A Letter from Mrs Preston (#litres_trial_promo)

31. Mrs Preston Goes Out to Tea (#litres_trial_promo)

32. A Confession (#litres_trial_promo)

33. Miss Penelope Gill (#litres_trial_promo)

34. Gillie Tells a Story (#litres_trial_promo)

35. Whose Fault Was It? (#litres_trial_promo)

36. The End of the Story (#litres_trial_promo)

37. Goodbye to Wuntermenny (#litres_trial_promo)

Postscript by Deborah Sheppard (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#ulink_80f6d107-2377-5a81-8c70-ed40e338134c)

ANNA (#ulink_80f6d107-2377-5a81-8c70-ed40e338134c)