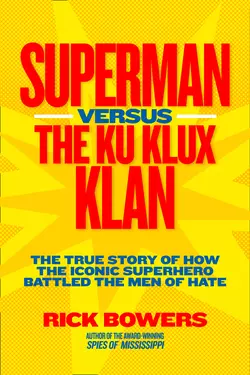

Superman versus the Ku Klux Klan: The True Story of How the Iconic Superhero Battled the Men of Hate

Superman versus the Ku Klux Klan: The True Story of How the Iconic Superhero Battled the Men of Hate

Richard Bowers

National Kids Geographic

With profound love: Wynn, Neva, Helen and Joy.

PUBLISHED BY THE NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SOCIETY

John M. Fahey, Jr., Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer; Tim T. Kelly, President; Declan Moore, Executive Vice President; President, Publishing; Melina Gerosa Bellows, Executive Vice President; Chief Creative Officer, Books, Kids, and Family

PREPARED BY THE BOOK DIVISION

Nancy Laties Feresten, Senior Vice President, Editor in Chief, Children’s Books; Jonathan Halling, Design Director, Books and Children’s Publishing; Jay Sumner, Director of Photography, Children’s Publishing; Jennifer Emmett, Editorial Director, Children’s Books; Carl Mehler, Director of Maps; R. Gary Colbert, Production Director; Jennifer A. Thornton, Managing Editor

STAFF FOR THIS BOOK

Nancy Laties Feresten, Editor; James Hiscott, Jr., Art Director/Designer; Lori Epstein, Senior Illustrations Editor; Kate Olesin, Editorial Assistant; Kathryn Robbins, Design Production Assistant; Hillary Moloney, Illustrations Assistant; Grace Hill, Associate Managing Editor; Lewis R. Bassford, Production Manager; Susan Borke, Legal and Business Affairs

MANUFACTURING AND QUALITY MANAGEMENT

Christopher A. Liedel, Chief Financial Officer; Phillip L. Schlosser, Senior Vice President; Chris Brown, Technical Director; Rachel Faulise, Nicole Elliot, and Robert L. Barr, Managers

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bowers, Rick, 1952-

Superman vs. the Ku Klux Klan : the true story of how the iconic superhero battled the men of hate / by Rick Bowers.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-1-4263-0917-5

1. Superman (Comic strip) 2. Superman (Fictitious character) 3. Ku Klux Klan (1915-) 4. Comic books, strips, etc.–Social aspects. I. Title.

PN6728.S9B69 2011

741.5′973–dc23

ILLUSTRATION CREDITS

8, Special Collections, Michael Schwartz Library at Cleveland State University; 16, Private collection; 22, American Stock/Getty Images; 30, Berenice Abbott/Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs/The New York Public Library; 36, Private collection; 46, Arthur Rothstein/FSA/State Archives of Florida/Library of Congress; 56, Library of Congress; 62, EPIC/The Kobal Collection; 68, Underwood & Underwood/Corbis; 78, Private collection; 86, Carl Iwasaki/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images; 92, Private collection; 98, Private collection; 106, Keystone Features/Getty Images; 114, The University of Maryland Broadcasting Archives; 124, Ed Clark/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images; 132, Leonard Detrick/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images; 140, Private collection; 150, Private collection.

All insert images courtesy of private collection unless otherwise noted below: insert 4, Lippert Pictures/Getty Images; insert 5, DC Comics/Warner Bros/The Kobal Collection

Text Copyright © 2012 Richard J. Bowers

Compilation copyright © 2012 National Geographic Society. All rights reserved. Reproduction without written permission from the publisher is prohibited.

For rights or permissions inquiries, please contact National Geographic Books Subsidiary Rights: ngbookrights@ngs.org (mailto:ngbookrights@ngs.org)

National Geographic’s net proceeds support vital exploration, conservation, research, and education programs.

Visit us online at www.nationalgeographic.com/books (http://www.nationalgeographic.com/books) For librarians and teachers: www.ngchildrensbooks.org (http://www.ngchildrensbooks.org) More for kids from National Geographic: kids.nationalgeographic.com (http://kids.nationalgeographic.com)

v3.1

Version: 2017-07-05

CONTENTS

Cover (#u5b96f0c0-71c4-5201-8330-f918f0cb1b05)

Title Page (#ua7d374a8-84f9-5256-bb19-2fe9e3351266)

Copyright (#u14e5dff8-e7b6-5848-9078-4ff8bbbe9943)

FROM THE AUTHOR (#uee88656d-07d4-5d68-8aaf-e430fd4c0b96)

PART ONE—THE BIRTH OF SUPERMAN

Chapter 1—Kosher Delis & Distant Galaxies (#u1eb5abe4-3a31-5316-a0df-afbcf87e49d0)

Chapter 2—Kindred Spirits & Creative Forces (#u57ef760b-70b9-5c4b-b76c-407ef9b43074)

Chapter 3—The Magic of the Mix (#uab1a127c-9e2b-5558-a860-842c6752ebd5)

Chapter 4—Bootleg Whiskey & Printer’s Ink (#u346f4d4e-ef21-5d2d-9ffc-565e3231514a)

Chapter 5—Champion of the Oppressed (#ucc6e643a-628f-56e8-a823-854d6fc5a16a)

PART TWO—EMERGING FROM THE SHADOWS

Chapter 6—Orange Groves & Hooded Horses (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7—The Original Klan (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8—Back From the Dead (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9—A Bold New Message (#litres_trial_promo)

PART THREE—JUGGERNAUT

Chapter 10—The Big Blue Money Machine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11—“Mayhem, Murder, Torture, & Abduction” (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12—On the Air (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13—The Secret Weapon (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14—Fighting Hate at Home (#litres_trial_promo)

PART FOUR—COLLISION

Chapter 15—Operation Intolerance (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16—Return to Stone Mountain (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17—“Clan of the Fiery Cross” (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18—Superman, We Applaud You (#litres_trial_promo)

AFTERWORD—WHAT HAPPENED TO THEM? (#litres_trial_promo)

BIBLIOGRAPHY (#litres_trial_promo)

SOURCES (#litres_trial_promo)

FROM THE AUTHOR

RESEARCHING AND WRITING Superman versus the Ku Klux Klan was like traveling back in time. To make the journey into the world of old superheroes, I pored through the vast archives of great libraries, universities, and the extensive personal compilations of dedicated comic book collectors and dealers. To track the birth and rebirths of the Ku Klux Klan, I studied the original writings of the first KKK supporters, the works of prominent historians, and the faded spy reports of anti-Klan infiltrators. I felt a great sense of excitement when these two powerful stories finally intersected at the Clan of the Fiery Cross—the 16-part Adventures of Superman radio show that pitted the Man of Steel against the men of hate. At that point the flow of history ran as strong and wild as the currents of two intersecting rivers. I’ll never forget the thrill of uncovering rare documents describing the extensive preparation the radio producers conducted to prepare for the controversial broadcasts. I’ll never forget the chills that ran through me while reading FBI-infiltrator reports of KKK meetings—reports capturing plans to attack and murder innocent people simply because of their skin color. Through all the historical files, infiltration documents, and interviews, I always sought to sort out myth from fact and capture the essence of truth. In the end I hope you enjoy reading the story as much as I enjoyed writing it. I hope you find Superman versus the Ku Klux Klan both informative and interesting and that you, too, will one day embark on your own journey back in time.

This book would not have been possible without the support of many talented and dedicated friends and colleagues. The first thank you goes to my editor at National Geographic, Nancy Feresten, who suggested the original idea and guided the process from start to finish. Special thanks also to her talented editorial ace Kate Olesin, whose organizational skills kept the process moving forward even when it wanted to pause. Also special thanks to the librarians and researchers at the Library of Congress, the University of Minnesota’s Elmer L. Andersen Library, and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York. These diligent protectors of our shared history opened up archives and tracked down documents, helping me locate valuable papers that had been collecting dust for decades. Extra special thanks to professor Steven Weisenburger of Southern Methodist University in Dallas for sharing his files on the Ku Klux Klan infiltration in Atlanta as well as the infiltration of the neo-Nazi Columbians. His work dissecting the underlying ideology of home-grown fascism continues to provide essential awareness of the continuing threat. Also, enormous gratitude to the private collector who allowed us to photograph and share her glimpses of some of the most precious and important comic books in the world. And finally to all the family members and friends who listened to my stories, read the early versions, and shared their ideas, your support is cherished.

*PART ONE *

THE BIRTH OF SUPERMAN

In the early 1930s newspaper headlines told of the hardships of the Great Depression. Americans fortunate enough to have jobs fretted about losing them. Those who had lost their jobs often turned to breadlines and soup kitchens just to keep from starving. In Europe the desperate economic climate had given rise to fascist leaders who preached the superiority of a master race and advocated the elimination of all “inferior” races. In a tight-knit Jewish enclave in Cleveland, Ohio, a shy teenager was working on a solution. To his mind, the world needed a superhero.

* CHAPTER 1 *

KOSHER DELIS & DISTANT GALAXIES

WALKING DOWN THE HALLWAY of Glenville High, Jerry Siegel braced for another day of disappointment. It was only 8:30 in the morning, and the 17-year-old science fiction aficionado was already counting the hours to the final bell. The pretty girl with the long, brown hair and flashing eyes would no doubt turn away from his glances. The student editor of the award-winning school newspaper, the Torch, would probably reject his latest story idea. The swaggering guys on the football team and the cliquish cheerleaders on their arms would not even acknowledge his existence. At least after school Jerry could hustle to his house at 10622 Kimberly Avenue, bound up to his hideaway in the attic, pick up a science fiction magazine, and lose himself in a fantasy world of mad scientists and rampaging monsters, space explorers and alien invaders, time travelers and spectral beings.

Jerry loved science fiction. Ever since he was a kid he had buried himself in a new breed of magazines with titles like Weird Tales and Amazing Stories. Full of dense print and crude illustrations, these simple, low-budget publications were magic to him. The smudged type on that thin paper told stories of intergalactic warfare, futuristic civilizations, and brilliant new technologies that promised a brighter and better world.

These astounding tales were attracting a growing audience of teenage fans across the country. They referred to their magazines as zines and shared their reactions and ideas through the mail. For Jerry, zines were the ultimate escape from his humdrum existence at school and the tension at home with his mother, who constantly babied him and worried that he was too much of a dreamer to make it in a harsh world.

Jerry had to admit that his future did not look all that bright. Because he lacked the grades and the money to go to college, the world ahead often seemed as bleak as the coldest, darkest reaches of outer space.

Jerry Siegel was the youngest of six children born to Mitchell and Sarah Siegel. Like so many other Jewish immigrants, Mitchell and Sarah had fled persecution in Europe to build a new life in America. After arriving from Lithuania, the couple had changed their name from Segalovich to fit in more easily in their adopted homeland. At first Mitchell worked as a sign painter and dreamed of becoming an artist. But with a growing family to support, jobs scarce, and money tight, he gave up his dream of painting beautiful works of art. Instead he opened a haberdashery, or secondhand-clothing store, near the factories in the old Jewish ghetto of Cleveland. Mitchell worked long hours, saved his money, and eventually moved the family out of the ghetto and into a comfortable, three-story, wood-frame house in Glenville, a close-knit neighborhood of nice homes, spacious front porches, and big backyards. Set amid rambling green hills and gurgling streams that meandered to Lake Erie, Glenville was the American dream come true for its tens of thousands of Jewish residents.

Glenville was also a protective cocoon for those residents—a safe haven from the prejudice that lurked just outside its borders. Sure, there were plenty of good, hardworking Christian people out there, but some Christians called Jews insulting names like kike and hebe and instructed their children to stay away from those kinds of kids. The classifieds in the Cleveland Plain Dealer were filled with job ads bluntly stating “No Jews Need Apply.” Country clubs in exclusive neighborhoods refused to accept Jewish members. There were even hate groups that called for the kinds of mass-removal programs that the Siegels thought they had escaped when they left Europe. In fact, Jews could simply turn on their radios to hear the Radio Priest, Father Charles Coughlin, spew anti-Semitic tirades from the National Shrine of the Little Flower Parish in Royal Oak, Michigan, just 180 miles from Glenville. A frequent speaker at mass rallies in Cleveland, Coughlin organized his most loyal followers into Christian Front organizations to oppose equality for Jewish Americans.

As the Great Depression wreaked economic havoc on the nation, another frightening fringe organization was becoming more and more active. With unemployment at a record high and clashes between striking workers and employers turning into bloody melees, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) sought to exploit public fear. Preaching a gospel of racism and religious intolerance, the KKK called upon white protestant men to band together to fight the Jew’s demand for social acceptance, the Negro’s plea for just treatment, and the immigrant’s call for decent jobs and fair pay. To keep up with the times, this secret society of hooded vigilantes had expanded its traditional hate list from Negroes, Jews, and Catholics to include union organizers, liberal politicians, civil rights advocates, crusading journalists, and supporters of the New Deal—President Franklin Roosevelt’s program to restore the economy by putting people to work. As tensions rose, new recruits came forward to join the nation’s most militant defender of white protestant rule. Although the KKK recruited only members who were white and protestant, it boasted of standing for the principle of “100 percent Americanism.”

On summer days the streets of Glenville buzzed with kids riding bikes, skipping rope, and playing stickball or hide-and-seek. On summer evenings teenage boys and girls walked hand in hand down the sidewalks, and gaggles of kids hung out on spacious front porches, told jokes, flirted, and talked about the future. Throughout the week pedestrians flowed down lively East 105th Street, where Solomon’s Delicatessen piled corned beef and pastrami high on fresh rye bread and Old World restaurants served classic European fare like brisket, cheese blintzes, matzo ball soup, and lox and bagels. On Saturdays, worshippers flocked to more than 25 synagogues, the men wearing the traditional yarmulke to cover their heads and the women dressed in the fashions of the day. The jewel of Glenville was the grand Jewish Center of Anshe Emeth (a synagogue) at East 105th and Grantwood Avenue, a modern building with a sculpture of the Star of David crowning its roof. It was the central gathering place for the community—the place to go to shoot basketball, to swim laps, or to take classes on subjects ranging from Hebrew tradition to American culture. By the early 1930s more than half of Cleveland’s Jewish population lived in Glenville, and more than 80 percent of the 1,600 kids at Glenville High were Jewish.

JERRY SIEGEL WAS DIFFERENT from most of the other kids in Glenville. While they were playing ball in the street, shooting hoops at the community center, or shopping on 105th Street, Jerry was holed up in the attic with his precious zines. He also loved to take in the movies at the Crown Theater, just a couple blocks from his house, or at the red-carpeted and balconied Uptown Theatre farther up 105th. Scrunched in his seat with a sack of popcorn in his lap and his eyes fixed on the screen, he marveled as the dashing actor Douglas Fairbanks donned a black cape and mask to become the leaping, lunging, sword-wielding Zorro. Jerry admired Fairbanks and all the other leading men—those strong, fearless, valiant he-man characters who took care of the bad guys and took care of the gorgeous women too. Jerry worshipped Clark Gable and Kent Taylor, whose names he would later combine to form Clark Kent.

Jerry usually sat in darkened theaters alone as he absorbed stories, tracked dialogue, and marveled at the characters. After the movies he would walk to the newsstands on St. Claire Avenue to pick up a pulp-fiction novel or a zine. Soaking in every line of narrative and dialogue, he would read the books and magazines cover to cover—then read them again. Turning to his secondhand typewriter, he would dash off letters to the editors, critiquing the stories and suggesting themes for future editions. He would scour the classified sections for the names and addresses of other science fiction fans and send them letters in which he shared his ideas for stories, plots, and characters. For kids like Jerry, science fiction provided a community—a network of fans bound together by a common passion.

One of Jerry’s favorite books was Philip Wylie’s Gladiator. Initially published in 1930, it was the first science fiction novel to introduce a character with superhuman powers. Jerry moved through the swollen river of words like an Olympian swimmer, devouring the description of the protagonist, Hugo Danner, whose bones and skin were so dense that he was more like steel than flesh, with the strength to hurl giant boulders, the speed to outrun trains, and the leaping ability of a grasshopper. Danner’s life is a tortured pursuit of the question of whether to use his powers for good or evil. That made Jerry think about how hard it was to choose right over wrong.

Then there was that unforgettable image of the flying man—the one he had seen on the cover of Amazing Stories. Jerry would hang on to that image for the rest of his life. The flying man, clad in a tight red outfit and wearing a leather pilot’s helmet, soared through the sunny sky and smiled down on a futuristic village filled with technological marvels. From the ground, a pretty, smiling girl waved a handkerchief at the airborne man and marveled at his fantastic abilities. In this edition of Amazing Stories Jerry saw a thrilling new world of scientific advances and social harmony—a perfect green and sunny utopia to be ushered in by creative geniuses with more brains than brawn, more natural imagination than school-injected facts, more good ideas than good looks. Jerry wanted to help create that utopia. Luckily, he had a partner in his quest.

* CHAPTER 2 *

KINDRED SPIRITS & CREATIVE FORCES

JOE SHUSTER WAS A fellow science fiction fanatic, a talented illustrator, and another skinny, bashful kid with thick glasses and no girlfriends. Jerry and Joe were kindred spirits and tireless collaborators. Sequestered in an attic work space after school and on weekends, the boys spent hours talking about science fiction, conjuring up story ideas, and drawing illustrations. Over time they would create a world of mad scientists and futuristic space travelers, smooth-talking detectives and supernatural beings. Although he could draw a bit, Jerry generally took the role of writer, his more assertive personality driving the action. Writing in pithy sentences that could be squeezed into small narrative boxes and thought bubbles, he would conjure the concept, plot the story line, and develop the narrative. As the illustrator, Joe would envision the characters and scenes and then put pencil to paper as he brought the characters to life on cheap, brown butcher paper laid across his mother’s favorite cutting board.

Early in 1932 Jerry and Joe went to work on their own typewritten magazine titled Science Fiction: The Advanced Guard of Future Civilization. Once they had their densely typed, roughly illustrated master copy in hand, they dashed off to the library to mimeograph copies and began mailing them to fellow fans within the free-ranging science fiction network. Science Fiction would also be sent to the publishers of the best zines, in hopes that one of them would purchase a piece of content, or, at least, recognize the talent of the young creators.

The third edition of Science Fiction featured a story entitled “The Reign of the Super-Man,” in which a bald, diabolical chemist sets out to use a substance derived from a meteor to turn himself into an evil genius with the power to dominate the world. Although most of the stories in Science Fiction were written by Jerry and illustrated by Joe, “The Reign of the Super-Man” was signed with the byline Herbert Fine. The two amateurs probably thought the pen name was a professional touch that would create the illusion that there was another writer in their limited stable of contributors. Plus, it added a bit of protection against any prejudiced publishers who might like the story but suspect that the writers were Jewish based on their real names.

Jerry and Joe’s “The Reign of the Super-Man” played off the grim realities of the Great Depression. In the story, treacherous Professor Smalley lures destitute, homeless men from soup kitchens to serve as guinea pigs for his hideous experiments: “With a contemptuous sneer on his face, Professor Smalley watched the wretched unfortunates file past him. To him, who had come of rich parents and had never been forced to face the rigors of life, the miserableness of these men seemed deserved.”

It was a good tale, but it was not the page-turner the duo had hoped for. What was it? Jerry and Joe would tackle that question later. The pair were in what should have been their last year at Glenville High, and the world of work was looming ahead—although they would both end up repeating that year because they lacked the grades to graduate.

In addition to hanging out with Joe, Jerry loved to spend time with his dad, Mitchell, who supported his youngest son’s creative endeavors. Maybe this support stemmed from Mitchell’s own abandoned dream of being a painter. Or perhaps he was just going easier on his youngest child than he had on the others, who had been expected to work part-time at the haberdashery, to do well in school, and to prepare to find good jobs (the boys) or good husbands (the girls). Then, in an instant, the family’s life changed forever.

On June 2, 1932, just after closing time, a neighboring merchant noticed that the haberdashery’s door was ajar. The interior lights were on, but Mitchell Siegel was nowhere in sight. The concerned shopkeeper pushed open the door and found Mitchell sprawled on the floor behind the counter—dead. The money in the cash register was gone, as were the three thugs who had robbed him. Initial police reports suggested that Siegel had been shot in the chest and found in a pool of blood behind the cash register. The coroner’s report later amended the scenario: Mitchell had suffered a fatal heart attack during the robbery. Either way, the Siegel family would never be the same.

Jerry’s mother fell into a deep depression. Her message to the children was cold and absolute: Never mention the robbery to anyone. All that the neighbors needed to know was that their father had died of a heart attack. Period. Relatives flocked to Sarah’s side, tried to console the kids, made sure that the bills were paid, and shook their heads over the tragedy. With the Great Depression bearing down, Mitchell’s income gone, and money tighter than ever, the family did the best they could. Devastated by the loss of his dad, Jerry withdrew even more into his science fiction world.

But a fire burned within him. He was more determined than ever to make it in the publishing business. He would work tirelessly to honor the memory of his hardworking father. He had no way of knowing that success was not far beyond the horizon. The shy, grieving, self-conscious, seemingly powerless teen could not foresee that his imagination would conjure up a muscular, all-powerful, super human who could deflect bullets, bend steel in his bare hands, soar into the sky, and protect the little guy from thugs and hoodlums like those who had caused his father’s death.

* CHAPTER 3 *

THE MAGIC OF THE MIX

BY 1934 NEWLY MINTED high school graduates Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster were operating their own comic art business. While their fellow Glenville graduates were taking introductory philosophy classes on college campuses, operating drill presses in factories, or searching for any work they could find, these offbeat science fiction devotees were pitching their ideas to professional editors and publishers. Fancying himself the business brains of the two-man outfit, Jerry took the lead in managing the enterprise. Concepts for new characters had to be put down on paper and sent out. Push. Letters had to be written to editors and publishers looking for content. Push. Push. Their primary targets were the syndicates that distributed comic strips to newspapers and the companies that were introducing a new kind of publication: comic books.

Jerry and Joe’s story of the Super-Man—that diabolical scientist who conducted gruesome experiments on unsuspecting homeless men—was still incubating in their minds. Then, according to Superman lore, late one night in the summer of 1934, the answer hit Jerry like a lightning bolt. They had it backward. The world had no need for an evil superman. The world needed a good superman—a trustworthy and powerful ally who would come to the rescue of regular people by protecting them from ruthless criminals, cheating businessmen, and corrupt politicians. With millions of people out of work, the streets full of crime, the stock market in ruins, and a war brewing in Europe, readers were starved for hope, inspiration, and a sense of power. A good superman could provide all that.

ACCORDING TO THE LORE, the essence of the character—the one the world would come to know—flashed into Jerry’s mind that restless night with the force of one of those sci-fi meteors crashing to Earth. In point of fact, the epiphany of the good superman sparked a long collaboration that would lead to the iteration of the character known today. The day after the epiphany, Jerry ran to Joe’s house, and the two began evolving the basic story line of the good superman. The next full-fledged version came several months later with the creation of an all-too-human hero the collaborators modestly dubbed “The Most Astounding Fiction Character of All Time!” This superman was strong, agile, and heroic but lacked extraordinary superpowers that would differentiate him from other heroes.

The few publishers who considered the proposal rejected it. Frustrated with the failure, Joe went into a rage and began destroying the manuscript. Jerry intervened but managed to save only the cover. The cover, showing the Superman leaping at a gun-wielding thug, was eerily reminiscent of Mitchell Siegel’s death. Still not quite right. The work continued.

As the writer, Jerry took the lead in developing the now-classic story line that finally emerged. Superman is born on the planet Krypton. His scientist father places him in a small rocket ship and launches him toward Earth just moments before Krypton erupts in devastating earthquakes and explosions that kill all the inhabitants. The spacecraft lands on Earth, where people discover the baby and take him to an orphanage in a small midwestern town. A family named Kent adopts him, gives him the name Clark, and raises him on a farm. After realizing the possibilities of his superhuman powers, Clark moves to the big city of Metropolis and becomes a reporter for a great metropolitan newspaper.

In times of trouble Clark sheds his street clothes and peels off his glasses to become Superman. He uses his powers to leap great heights, to hoist huge weights, to deflect bullets, to soar into the sky, and to subdue criminals. His only motives are to protect the innocent, to bring the guilty to justice, and to crusade for a better world. After saving the day, Superman returns to his guise as the mild-mannered Clark, who works at the newspaper with a gutsy “girl reporter” named Lois Lane. But Lois has little time for bespectacled, nerdy Clark. She only has eyes for Superman.

Sensing that the character was special, the two creators worked feverishly to fill in the details of his persona. Before long the full picture was on the page. Superman had his rugged good looks, his shock of blue-black hair, his muscular physique, his flowing red cape, and the bold S insignia on his chest. Joe designed his uniform as a cross between a spaceman suit and a classic circus performer outfit—down to the blue tights, red shorts, and cape. He skillfully captured each of Superman’s actions in single comic panels: the caped crusader raising his arms toward the heavens, leaping off the ground with incredible strength, soaring upward at supersonic speed, and landing with both feet firmly planted on the ground. The Man of Steel—also called the Man of Tomorrow in those early days—stands tall, hands on his hips, bullets bouncing off his chest, as befuddled, gun-packing gangsters fire shot after harmless shot. In time the classic image would evolve: The handsome, smiling superhero would save Lois Lane from all kinds of danger, hoist her in his arms, soar over the flickering lights of Metropolis, and deliver her safely home.

To breathe life into the Superman character, Jerry and Joe drew upon their love of science fiction, their passion for movies, their fascination for books, and their experiences growing up Jewish during the Great Depression. The Greek and Roman myths they learned at school featured heroes with superhuman strength. Strange visitors from distant planets were common in the science fiction stories they devoured night and day. Daredevil heroes clad in masks and capes were all the rage in the movies they watched at the Crown and the Uptown. Even heroes with dual identities were commonplace on the screen and in print. The silent screen character Zorro was the alter ego of Don Diego de la Vega, a sissified aristocrat who ate, drank, and dressed the dandy to throw off suspicion of his role as the night-riding avenger. The Shadow, a pulp magazine character, was the alter ego of Kent Allard, a famed pilot who fought for the French during World War I. Just as the name Clark Kent was a cross between actors Clark Gable and Kent Taylor, the name of the mythical city of Metropolis came from the 1927 silent film of the same name. For Superman, the magic was in the mix.

Jerry and Joe’s Jewish heritage deeply influenced the makeup of Superman too. The all-American superhero reflected many of the beliefs and values of Jewish immigrants of the day. Like them, Superman had come to America from a foreign world. Like them, he longed to fit in to his strange new surroundings. Superman also seemed to embody the Jewish principle of tzedakah—a command to serve the less fortunate and to stand up for the weak and exploited—and the concept of tikkun olam, the mandate to do good works (literally, to “repair a broken world”). Even the language of Superman had Jewish origins. Before Superman is blasted off the dying planet of Krypton, Superman’s father, Jor-El, names his son Kal-El. In ancient Hebrew the suffix El means “all that is God.”

Then there is the Moses connection. Just before Krypton explodes, Superman’s parents place him in a crib-size rocket and launch him toward Earth to be raised by loving strangers. In the Old Testament, after Pharaoh decrees that all newborn Jewish males be killed, Moses’s mother places him in a crib-size basket and launches him down the Nile River to be raised by others. Just as Pharaoh’s daughter rescues the infant Moses from the bulrushes and nurtures him as her own, the Kents find and raise Superman on Earth. The Superman story also resembles the tale of Rabbi Maharal of Prague, who created his own superman, called the Golem, to protect the people of the Jewish ghetto from hostile Christians.

While Superman was a complex conglomeration of influences, Jerry and Joe left plenty to readers’ imaginations. What Superman wasn’t was just as important as what he was. The character had no clear ethnic background, no hint of an accent or dialect, no stated religious preference, and no political affiliation. The Superman character offered a little bit to everyone. Coming from a distant planet, he was the ultimate foreigner. Raised in the midwestern heartland, he was the quintessential American. Growing up in a small town, he was rural at heart. Moving to a big city, he became more sophisticated and worldly. He was both weak and strong. His meek, mild alter ego, Clark Kent, was a sheepish bumbler, but he was always ready to transform himself into the all-powerful superhero. So Superman was relevant to the prairie farmer, the urban factory worker, the white-collar insurance salesman, the hardworking waitress, and the struggling immigrant. Millions of ordinary people struggling through the Depression could imagine themselves shedding their plain, run-of-the-mill exteriors to reveal their real power within. True, Superman had descended from the heavens with the power of a god. His intention was godly too—to protect humanity from its own worst instincts. But Superman had characteristics the masses could relate to. He could beam with a smile, burst into anger, and form lasting friendships. Beneath it all Superman seemed like a regular guy.

Superman was also a creation of his times. To keep up with those times, Jerry and Joe often spent Saturdays flipping through out-of-town newspapers and national newsmagazines for ideas at the Cleveland Public Library. The headlines described crisis after crisis. The New York Stock Exchange had lost 90 percent of its value. Millions of Americans were out of work. A midwestern drought had engulfed prairie farms in the Dust Bowl, and desperate farmers had to pack up their starving families and head to California to start anew. The international news was no more comforting. Headlines warned of economic collapse in global markets, the rise of fascist regimes in Europe, and the new communist experiment in the Soviet Union. The whole world seemed to be heading toward an explosion.

Despite the challenges, Jerry and Joe found hope in President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had declared in his 1932 inaugural address that “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” The two teenagers liked the sound of Roosevelt’s promise of “a new deal for America.” FDR proposed a series of government programs designed to create jobs, to restore the economy, and to address a range of social ills. In his popular fireside chats, broadcast on all the major radio networks in an era before the invention of television, Roosevelt spoke in plain language that resonated with common men and women. As children of the Depression, Jerry and Joe saw hope in FDR’s pledge to help the average person cope with the “hazards and vicissitudes of life,” to provide some measure of protection “to the average citizen and to his family against the loss of a job and against poverty-ridden old age.” Superman could get behind goals like that.

While FDR had broad public support, fierce critics charged him with either ignoring the national crisis or overreacting to it. Conservative opponents called him a socialist and formed the American Liberty League to derail his welfare programs. Radical opponents wrote off FDR’s relief initiatives as “mere crumbs” and demanded sweeping “share the wealth” programs that involved confiscating the money and property of the rich and redistributing it to the poor. Answering the critics, Roosevelt declared:

A few timid people, who fear progress, will try to give you new and strange names for what we are doing. Sometimes they will call it “fascism,” sometimes “communism,” sometimes “regimentation,” sometimes “socialism …” I believe that what we are doing today is a necessary fulfillment of what Americans have always been doing—a fulfillment of old and tested American ideals.

So Jerry and Joe plucked elements from the world around them to stir into their Superman stew. For the most part, however, Superman’s millions of fans would ignore his origins. For them the Man of Steel would simply be the defender of the little man and woman—and a big problem for the forces of evil in the world.

* CHAPTER 4 *

BOOTLEG WHISKEY & PRINTER’S INK

SUPERMAN WAS FASTER than a speeding bullet. His rise to fame was not. The right people would have to come along, and the right circumstances would have to present themselves, before the world could meet Jerry and Joe’s new character. Some 500 miles from Glenville was a place where the optimal conditions for the launch of this new kind of superhero had been brewing—the high-energy world of New York City publishing.

In the early 20th century the Big Apple had changed rapidly from a crass and overpopulated commercial center to the self-proclaimed “greatest city in the world,” and the printed word, photo, and hand-drawn illustration were among its most important commodities. Amid the grit and glamour, clamor and chaos of the bustling sidewalks stood a loosely organized network of newsstands—thousands of gathering places where customers looked through rack after rack of magazines and pulp books covering an ever-expanding range of passions and pursuits. From the offices of the great skyscrapers, visionary publishers launched entire companies dedicated to serving specific slices of readers’ expanding interests and hobbies. From the bowels of the city’s grimy manufacturing hubs, printing presses rolled out a steady stream of books, magazines, and newspapers in currents as strong as those of the nearby Hudson River. For the professional types among the waves of immigrants entering the United States through the halls of Ellis Island, and for their children, the publishing industry represented a chance at getting a thinking man’s job.

The advent of cheap and efficient color printing technology, coupled with car and truck delivery to newsstands and stores, pushed the growth of the publishing business. By the freewheeling 1920s printing presses rolled out vast quantities of titles such as Indolent Kisses and Heart Throbs to True Detective and Time. Ambitious publishers, persnickety editors, creative writers, talented illustrators, and hardworking pressmen served a market of seemingly insatiable readers.

While the disheartening effect of the Great Depression put a damper on the New York publishing trade, the great newspapers, newsmagazines, and popular magazines survived even as their weaker competitors vanished. And even as the quest for profits grew more brutal and the scramble for jobs intensified, New York remained the center of the publishing industry in America. It offered the enterprising entrepreneur an opportunity to run with an idea, to forge a market, and to make a living. The keys to success were twofold: a good idea and a fighting spirit.

In 1933 an out-of-work, would-be publisher and newspaper comic strip aficionado named Max Gaines (he had changed his name from Maxwell Ginzburg to sound less Jewish) came up with one of those good ideas: to take daily and weekly comic strips from newspapers; to arrange them on pages of cheap newsprint; to staple the pages between glossy, four-color cardboard covers; and to market the books to kids. The Eastern Color Printing Company agreed to test Gaines’s concept and produced 35,000 copies of Famous Funnies, Series 1, for distribution as a free promotion to department stores. The entire print run vanished almost overnight, and Eastern rushed Famous Funnies, Series 2, to newsstands. This time the company sold copies for a dime apiece.

Eastern then launched an entire series of comic compilation books without the services of the disappointed Gaines. But the enterprising businessman—showing that fighting spirit—struck a profit-sharing deal with the McClure Newspaper Syndicate and set out to launch a competing line. As Gaines’s new titles became profitable, more publishers began bundling books of comic strip reprints and selling them at newsstands and dime stores. Before long the backlog of available newspaper strips had been exhausted, and existing content for new compilations was scarce.

That’s when the trailblazing publisher of National Allied Publications began hiring new writers and illustrators to create original strips and new characters. Other publishers followed suit. In this wild swirl of competition, the comic book industry began to take shape. Since almost all the major players were Jewish, Jewish writers and illustrators were free to apply for work. This was their chance to start a career in the broader publishing trade. As Jerry and Joe worked on new characters far away in Cleveland, the delivery system for their creations was being built.

By the mid-1930s a short, dapper, well-connected, and highly successful publisher named Harry Donenfeld was contemplating entry into the emerging field. Donenfeld had an appetite for success and the track record to prove it. He knew how to pick titles that sold, hire writers with sizzle, print on the cheap, and, if necessary, muscle his magazines into newsstands, drugstores, cigar stores, barbershops, and beauty salons. Wining and dining wealthy businessmen and powerful politicians at the best restaurants in Manhattan, he spared no expense for his potential clients, influential colleagues, and fun-loving friends.

Donenfeld had made a fortune back in the Roaring Twenties by publishing girlie magazines and racy pulp titles, which had sold as fast as his rackety printing presses could roll them out. With Prohibition in force, Donenfeld had supplemented his publishing profits by transporting stockpiles of bootleg whiskey into New York. He had hid the illegal booze in train cars carrying paper shipments from Canada and sold the hooch to speakeasies across the city, while marketing his magazines and books nationwide. Harry Donenfeld was living the high life—on his terms. His wife Gussie kept their home in the Bronx like a showplace as Donenfeld paraded his girlfriends through the glitziest clubs in town.

But those Roaring Twenties gave way to the Depression, Prohibition was repealed, and the world was far less forgiving of questionable business dealings. Political reformers were looking askance at big shots who cashed in on borderline pornography while millions of decent, out-of-work Americans scrambled to keep from starving. By 1937 New York mayor Fiorello LaGuardia was running for reelection on the promise of shutting down indecent books and magazines, and prosecutors were bringing indictments against risqué publishers. So Donenfeld set out to establish a more legitimate product line. He thought bigger and played harder than anyone else in the fledgling comic book field and figured he could get in on the ground floor and gobble up the profits. The comic book trade was still limited, but the potential for growth was promising. He needed a breakthrough title. He had no way of knowing that two young men in Cleveland had created a character who could provide that kind of breakthrough.

TO MOVE INTO THE COMIC FIELD, Donenfeld turned to his friend, business partner, and spiritual opposite Jack Liebowitz, a no-nonsense, detail-savvy accountant who had grown up in the same Lower East Side, New York, neighborhood as the flamboyant Donenfeld. In contrast to Donenfeld, during those same Roaring Twenties, Liebowitz had studied accounting at night at New York University and had gone to work as a financial manager for the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. He got by on a modest salary while working to win higher wages and better working conditions for immigrants who toiled in crowded sweatshops for 12 to 14 hours a day.

Liebowitz, whose parents had left Ukraine and settled in New York City when he was three, could relate to the hardworking garment makers and believe in their cause. But by the early 1930s, with the Depression bearing down, the striking union out of money, and radical communists attempting a takeover, Liebowitz was more than ready to go into business with a smooth operator from the old neighborhood.

So, the mild-mannered accountant and the back-slapping business tycoon cast their gaze on the emerging comic book business. As the first commercial comic books rolled off the same presses that printed cheap pulp magazines like Ghost Stories, Strange Suicides, and Medical Horrors, Donenfeld and Liebowitz maneuvered for an opening. By 1938 the pair had taken over National Allied Publications and DC Comics (publisher of Detective Comics), thus setting themselves up as major players in the emerging comic book industry.

* CHAPTER 5 *

CHAMPION OF THE OPPRESSED

AS THE COMIC BOOK INDUSTRY took shape in New York, Jerry and Joe were eking out a living by operating their own two-man comic business in Cleveland. The aspiring writer and illustrator were living with their parents to save on expenses, working from a makeshift studio in Joe’s attic, and working menial part-time jobs to make ends meet. Having managed to get a couple of contracts with new comic book publishers in New York, the pair developed a few interesting characters. Their title Federal Men featured a wisecracking Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agent named Steve Carson who worked undercover to find kidnapped babies and shut down criminal gangs. Spooky Dr. Occult was a brash, supernatural ghost detective who tracked down zombies, vampires, and other spectral figures. In some episodes the evil Dr. Occult even donned a red cape and took flight as the creators tried out a bit of their Superman material. As the work ebbed and flowed, Jerry and Joe waited for their big break. That’s where Superman was supposed to come in.

At first Jerry insisted on holding back the Superman character from the low-paying comic book publishers in hopes of selling it to an established newspaper syndicate. A major syndicate like King Features or United Features could place a Superman strip in hundreds of newspapers nationwide and generate thousands of dollars in royalties in the process. A portion of the royalties would go to the creators week after week, month after month, year after year, for the life of the strip. Strips like Little Orphan Annie and Popeye had been popular in newspapers for years, and their creators were dining at the top of the comic-art food chain. But the strategy of saving Superman for syndication had produced only a drawer full of rejection letters from syndicate executives, who claimed that an all-powerful being from another planet, dressed in tights and serving the public good, was too far-fetched for a broad newspaper audience comprised mostly of adults. One editor from United Features indelicately summed up Superman as “a rather immature piece of work.”

Losing patience with rejections, Jerry and Joe finally sent off Superman samples to comic book publishers, only to receive more negative feedback. With no one in the publishing business showing interest in the Superman character, the Man of Steel sat on the shelf. Then, one day in the spring of 1938, Jerry and Joe opened the mail to find an intriguing proposal from DC Comics—Harry Donenfeld’s promising new venture. The letter came from editor Vin Sullivan, who had been assigned to launch a new title, Action Comics (AC), to build on the success of DC Comics. Jerry and Joe had created a couple of the lesser characters for Donenfeld’s publications, but this new one sounded bigger. Sullivan wanted a 13-page Superman adventure as the lead story for the debut issue of AC. Sullivan was desperate for a good character and didn’t have time to start from scratch with a new concept. He had come across an old, rejected Superman proposal, and he was willing to pay Siegel and Shuster to recraft it for AC—pronto. Jerry and Joe’s company would have to produce the four-color cover and 13 pages of illustrated text in a couple of weeks to meet a fast-approaching deadline.

Tired of watching their best character sit on the shelf as new comic books rolled out new superheroes every week (even the word “super” was turning up regularly), Siegel and Shuster accepted the offer and began scrambling to fill the order. After a series of back-and-forth rewrites, remakes, and spats between the Cleveland collaborators and the New York publishers, 200,000 copies of the comic went to press in the summer of 1938. Action Comics No. 1 hit the newsstands with Superman on the cover. The hero is effortlessly lifting a car as men scramble in stupefied horror.

Although the story would be embellished and refined in future editions, the first page of panels in Action Comics No. 1 lays out the superhero’s basic origins and core identity. It also reveals his decidedly liberal leanings. Superman bursts onto the scene as the New Deal blend of optimism and social responsibility, a muscular do-gooder with a boundless passion for justice. Or as Action Comics

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/national-geographic-/superman-versus-the-ku-klux-klan-the-true-story-of-ho/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Richard Bowers

National Kids Geographic

With profound love: Wynn, Neva, Helen and Joy.

PUBLISHED BY THE NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SOCIETY

John M. Fahey, Jr., Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer; Tim T. Kelly, President; Declan Moore, Executive Vice President; President, Publishing; Melina Gerosa Bellows, Executive Vice President; Chief Creative Officer, Books, Kids, and Family

PREPARED BY THE BOOK DIVISION

Nancy Laties Feresten, Senior Vice President, Editor in Chief, Children’s Books; Jonathan Halling, Design Director, Books and Children’s Publishing; Jay Sumner, Director of Photography, Children’s Publishing; Jennifer Emmett, Editorial Director, Children’s Books; Carl Mehler, Director of Maps; R. Gary Colbert, Production Director; Jennifer A. Thornton, Managing Editor

STAFF FOR THIS BOOK

Nancy Laties Feresten, Editor; James Hiscott, Jr., Art Director/Designer; Lori Epstein, Senior Illustrations Editor; Kate Olesin, Editorial Assistant; Kathryn Robbins, Design Production Assistant; Hillary Moloney, Illustrations Assistant; Grace Hill, Associate Managing Editor; Lewis R. Bassford, Production Manager; Susan Borke, Legal and Business Affairs

MANUFACTURING AND QUALITY MANAGEMENT

Christopher A. Liedel, Chief Financial Officer; Phillip L. Schlosser, Senior Vice President; Chris Brown, Technical Director; Rachel Faulise, Nicole Elliot, and Robert L. Barr, Managers

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bowers, Rick, 1952-

Superman vs. the Ku Klux Klan : the true story of how the iconic superhero battled the men of hate / by Rick Bowers.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-1-4263-0917-5

1. Superman (Comic strip) 2. Superman (Fictitious character) 3. Ku Klux Klan (1915-) 4. Comic books, strips, etc.–Social aspects. I. Title.

PN6728.S9B69 2011

741.5′973–dc23

ILLUSTRATION CREDITS

8, Special Collections, Michael Schwartz Library at Cleveland State University; 16, Private collection; 22, American Stock/Getty Images; 30, Berenice Abbott/Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs/The New York Public Library; 36, Private collection; 46, Arthur Rothstein/FSA/State Archives of Florida/Library of Congress; 56, Library of Congress; 62, EPIC/The Kobal Collection; 68, Underwood & Underwood/Corbis; 78, Private collection; 86, Carl Iwasaki/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images; 92, Private collection; 98, Private collection; 106, Keystone Features/Getty Images; 114, The University of Maryland Broadcasting Archives; 124, Ed Clark/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images; 132, Leonard Detrick/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images; 140, Private collection; 150, Private collection.

All insert images courtesy of private collection unless otherwise noted below: insert 4, Lippert Pictures/Getty Images; insert 5, DC Comics/Warner Bros/The Kobal Collection

Text Copyright © 2012 Richard J. Bowers

Compilation copyright © 2012 National Geographic Society. All rights reserved. Reproduction without written permission from the publisher is prohibited.

For rights or permissions inquiries, please contact National Geographic Books Subsidiary Rights: ngbookrights@ngs.org (mailto:ngbookrights@ngs.org)

National Geographic’s net proceeds support vital exploration, conservation, research, and education programs.

Visit us online at www.nationalgeographic.com/books (http://www.nationalgeographic.com/books) For librarians and teachers: www.ngchildrensbooks.org (http://www.ngchildrensbooks.org) More for kids from National Geographic: kids.nationalgeographic.com (http://kids.nationalgeographic.com)

v3.1

Version: 2017-07-05

CONTENTS

Cover (#u5b96f0c0-71c4-5201-8330-f918f0cb1b05)

Title Page (#ua7d374a8-84f9-5256-bb19-2fe9e3351266)

Copyright (#u14e5dff8-e7b6-5848-9078-4ff8bbbe9943)

FROM THE AUTHOR (#uee88656d-07d4-5d68-8aaf-e430fd4c0b96)

PART ONE—THE BIRTH OF SUPERMAN

Chapter 1—Kosher Delis & Distant Galaxies (#u1eb5abe4-3a31-5316-a0df-afbcf87e49d0)

Chapter 2—Kindred Spirits & Creative Forces (#u57ef760b-70b9-5c4b-b76c-407ef9b43074)

Chapter 3—The Magic of the Mix (#uab1a127c-9e2b-5558-a860-842c6752ebd5)

Chapter 4—Bootleg Whiskey & Printer’s Ink (#u346f4d4e-ef21-5d2d-9ffc-565e3231514a)

Chapter 5—Champion of the Oppressed (#ucc6e643a-628f-56e8-a823-854d6fc5a16a)

PART TWO—EMERGING FROM THE SHADOWS

Chapter 6—Orange Groves & Hooded Horses (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7—The Original Klan (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8—Back From the Dead (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9—A Bold New Message (#litres_trial_promo)

PART THREE—JUGGERNAUT

Chapter 10—The Big Blue Money Machine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11—“Mayhem, Murder, Torture, & Abduction” (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12—On the Air (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13—The Secret Weapon (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14—Fighting Hate at Home (#litres_trial_promo)

PART FOUR—COLLISION

Chapter 15—Operation Intolerance (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16—Return to Stone Mountain (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17—“Clan of the Fiery Cross” (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18—Superman, We Applaud You (#litres_trial_promo)

AFTERWORD—WHAT HAPPENED TO THEM? (#litres_trial_promo)

BIBLIOGRAPHY (#litres_trial_promo)

SOURCES (#litres_trial_promo)

FROM THE AUTHOR

RESEARCHING AND WRITING Superman versus the Ku Klux Klan was like traveling back in time. To make the journey into the world of old superheroes, I pored through the vast archives of great libraries, universities, and the extensive personal compilations of dedicated comic book collectors and dealers. To track the birth and rebirths of the Ku Klux Klan, I studied the original writings of the first KKK supporters, the works of prominent historians, and the faded spy reports of anti-Klan infiltrators. I felt a great sense of excitement when these two powerful stories finally intersected at the Clan of the Fiery Cross—the 16-part Adventures of Superman radio show that pitted the Man of Steel against the men of hate. At that point the flow of history ran as strong and wild as the currents of two intersecting rivers. I’ll never forget the thrill of uncovering rare documents describing the extensive preparation the radio producers conducted to prepare for the controversial broadcasts. I’ll never forget the chills that ran through me while reading FBI-infiltrator reports of KKK meetings—reports capturing plans to attack and murder innocent people simply because of their skin color. Through all the historical files, infiltration documents, and interviews, I always sought to sort out myth from fact and capture the essence of truth. In the end I hope you enjoy reading the story as much as I enjoyed writing it. I hope you find Superman versus the Ku Klux Klan both informative and interesting and that you, too, will one day embark on your own journey back in time.

This book would not have been possible without the support of many talented and dedicated friends and colleagues. The first thank you goes to my editor at National Geographic, Nancy Feresten, who suggested the original idea and guided the process from start to finish. Special thanks also to her talented editorial ace Kate Olesin, whose organizational skills kept the process moving forward even when it wanted to pause. Also special thanks to the librarians and researchers at the Library of Congress, the University of Minnesota’s Elmer L. Andersen Library, and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York. These diligent protectors of our shared history opened up archives and tracked down documents, helping me locate valuable papers that had been collecting dust for decades. Extra special thanks to professor Steven Weisenburger of Southern Methodist University in Dallas for sharing his files on the Ku Klux Klan infiltration in Atlanta as well as the infiltration of the neo-Nazi Columbians. His work dissecting the underlying ideology of home-grown fascism continues to provide essential awareness of the continuing threat. Also, enormous gratitude to the private collector who allowed us to photograph and share her glimpses of some of the most precious and important comic books in the world. And finally to all the family members and friends who listened to my stories, read the early versions, and shared their ideas, your support is cherished.

*PART ONE *

THE BIRTH OF SUPERMAN

In the early 1930s newspaper headlines told of the hardships of the Great Depression. Americans fortunate enough to have jobs fretted about losing them. Those who had lost their jobs often turned to breadlines and soup kitchens just to keep from starving. In Europe the desperate economic climate had given rise to fascist leaders who preached the superiority of a master race and advocated the elimination of all “inferior” races. In a tight-knit Jewish enclave in Cleveland, Ohio, a shy teenager was working on a solution. To his mind, the world needed a superhero.

* CHAPTER 1 *

KOSHER DELIS & DISTANT GALAXIES

WALKING DOWN THE HALLWAY of Glenville High, Jerry Siegel braced for another day of disappointment. It was only 8:30 in the morning, and the 17-year-old science fiction aficionado was already counting the hours to the final bell. The pretty girl with the long, brown hair and flashing eyes would no doubt turn away from his glances. The student editor of the award-winning school newspaper, the Torch, would probably reject his latest story idea. The swaggering guys on the football team and the cliquish cheerleaders on their arms would not even acknowledge his existence. At least after school Jerry could hustle to his house at 10622 Kimberly Avenue, bound up to his hideaway in the attic, pick up a science fiction magazine, and lose himself in a fantasy world of mad scientists and rampaging monsters, space explorers and alien invaders, time travelers and spectral beings.

Jerry loved science fiction. Ever since he was a kid he had buried himself in a new breed of magazines with titles like Weird Tales and Amazing Stories. Full of dense print and crude illustrations, these simple, low-budget publications were magic to him. The smudged type on that thin paper told stories of intergalactic warfare, futuristic civilizations, and brilliant new technologies that promised a brighter and better world.

These astounding tales were attracting a growing audience of teenage fans across the country. They referred to their magazines as zines and shared their reactions and ideas through the mail. For Jerry, zines were the ultimate escape from his humdrum existence at school and the tension at home with his mother, who constantly babied him and worried that he was too much of a dreamer to make it in a harsh world.

Jerry had to admit that his future did not look all that bright. Because he lacked the grades and the money to go to college, the world ahead often seemed as bleak as the coldest, darkest reaches of outer space.

Jerry Siegel was the youngest of six children born to Mitchell and Sarah Siegel. Like so many other Jewish immigrants, Mitchell and Sarah had fled persecution in Europe to build a new life in America. After arriving from Lithuania, the couple had changed their name from Segalovich to fit in more easily in their adopted homeland. At first Mitchell worked as a sign painter and dreamed of becoming an artist. But with a growing family to support, jobs scarce, and money tight, he gave up his dream of painting beautiful works of art. Instead he opened a haberdashery, or secondhand-clothing store, near the factories in the old Jewish ghetto of Cleveland. Mitchell worked long hours, saved his money, and eventually moved the family out of the ghetto and into a comfortable, three-story, wood-frame house in Glenville, a close-knit neighborhood of nice homes, spacious front porches, and big backyards. Set amid rambling green hills and gurgling streams that meandered to Lake Erie, Glenville was the American dream come true for its tens of thousands of Jewish residents.

Glenville was also a protective cocoon for those residents—a safe haven from the prejudice that lurked just outside its borders. Sure, there were plenty of good, hardworking Christian people out there, but some Christians called Jews insulting names like kike and hebe and instructed their children to stay away from those kinds of kids. The classifieds in the Cleveland Plain Dealer were filled with job ads bluntly stating “No Jews Need Apply.” Country clubs in exclusive neighborhoods refused to accept Jewish members. There were even hate groups that called for the kinds of mass-removal programs that the Siegels thought they had escaped when they left Europe. In fact, Jews could simply turn on their radios to hear the Radio Priest, Father Charles Coughlin, spew anti-Semitic tirades from the National Shrine of the Little Flower Parish in Royal Oak, Michigan, just 180 miles from Glenville. A frequent speaker at mass rallies in Cleveland, Coughlin organized his most loyal followers into Christian Front organizations to oppose equality for Jewish Americans.

As the Great Depression wreaked economic havoc on the nation, another frightening fringe organization was becoming more and more active. With unemployment at a record high and clashes between striking workers and employers turning into bloody melees, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) sought to exploit public fear. Preaching a gospel of racism and religious intolerance, the KKK called upon white protestant men to band together to fight the Jew’s demand for social acceptance, the Negro’s plea for just treatment, and the immigrant’s call for decent jobs and fair pay. To keep up with the times, this secret society of hooded vigilantes had expanded its traditional hate list from Negroes, Jews, and Catholics to include union organizers, liberal politicians, civil rights advocates, crusading journalists, and supporters of the New Deal—President Franklin Roosevelt’s program to restore the economy by putting people to work. As tensions rose, new recruits came forward to join the nation’s most militant defender of white protestant rule. Although the KKK recruited only members who were white and protestant, it boasted of standing for the principle of “100 percent Americanism.”

On summer days the streets of Glenville buzzed with kids riding bikes, skipping rope, and playing stickball or hide-and-seek. On summer evenings teenage boys and girls walked hand in hand down the sidewalks, and gaggles of kids hung out on spacious front porches, told jokes, flirted, and talked about the future. Throughout the week pedestrians flowed down lively East 105th Street, where Solomon’s Delicatessen piled corned beef and pastrami high on fresh rye bread and Old World restaurants served classic European fare like brisket, cheese blintzes, matzo ball soup, and lox and bagels. On Saturdays, worshippers flocked to more than 25 synagogues, the men wearing the traditional yarmulke to cover their heads and the women dressed in the fashions of the day. The jewel of Glenville was the grand Jewish Center of Anshe Emeth (a synagogue) at East 105th and Grantwood Avenue, a modern building with a sculpture of the Star of David crowning its roof. It was the central gathering place for the community—the place to go to shoot basketball, to swim laps, or to take classes on subjects ranging from Hebrew tradition to American culture. By the early 1930s more than half of Cleveland’s Jewish population lived in Glenville, and more than 80 percent of the 1,600 kids at Glenville High were Jewish.

JERRY SIEGEL WAS DIFFERENT from most of the other kids in Glenville. While they were playing ball in the street, shooting hoops at the community center, or shopping on 105th Street, Jerry was holed up in the attic with his precious zines. He also loved to take in the movies at the Crown Theater, just a couple blocks from his house, or at the red-carpeted and balconied Uptown Theatre farther up 105th. Scrunched in his seat with a sack of popcorn in his lap and his eyes fixed on the screen, he marveled as the dashing actor Douglas Fairbanks donned a black cape and mask to become the leaping, lunging, sword-wielding Zorro. Jerry admired Fairbanks and all the other leading men—those strong, fearless, valiant he-man characters who took care of the bad guys and took care of the gorgeous women too. Jerry worshipped Clark Gable and Kent Taylor, whose names he would later combine to form Clark Kent.

Jerry usually sat in darkened theaters alone as he absorbed stories, tracked dialogue, and marveled at the characters. After the movies he would walk to the newsstands on St. Claire Avenue to pick up a pulp-fiction novel or a zine. Soaking in every line of narrative and dialogue, he would read the books and magazines cover to cover—then read them again. Turning to his secondhand typewriter, he would dash off letters to the editors, critiquing the stories and suggesting themes for future editions. He would scour the classified sections for the names and addresses of other science fiction fans and send them letters in which he shared his ideas for stories, plots, and characters. For kids like Jerry, science fiction provided a community—a network of fans bound together by a common passion.

One of Jerry’s favorite books was Philip Wylie’s Gladiator. Initially published in 1930, it was the first science fiction novel to introduce a character with superhuman powers. Jerry moved through the swollen river of words like an Olympian swimmer, devouring the description of the protagonist, Hugo Danner, whose bones and skin were so dense that he was more like steel than flesh, with the strength to hurl giant boulders, the speed to outrun trains, and the leaping ability of a grasshopper. Danner’s life is a tortured pursuit of the question of whether to use his powers for good or evil. That made Jerry think about how hard it was to choose right over wrong.

Then there was that unforgettable image of the flying man—the one he had seen on the cover of Amazing Stories. Jerry would hang on to that image for the rest of his life. The flying man, clad in a tight red outfit and wearing a leather pilot’s helmet, soared through the sunny sky and smiled down on a futuristic village filled with technological marvels. From the ground, a pretty, smiling girl waved a handkerchief at the airborne man and marveled at his fantastic abilities. In this edition of Amazing Stories Jerry saw a thrilling new world of scientific advances and social harmony—a perfect green and sunny utopia to be ushered in by creative geniuses with more brains than brawn, more natural imagination than school-injected facts, more good ideas than good looks. Jerry wanted to help create that utopia. Luckily, he had a partner in his quest.

* CHAPTER 2 *

KINDRED SPIRITS & CREATIVE FORCES

JOE SHUSTER WAS A fellow science fiction fanatic, a talented illustrator, and another skinny, bashful kid with thick glasses and no girlfriends. Jerry and Joe were kindred spirits and tireless collaborators. Sequestered in an attic work space after school and on weekends, the boys spent hours talking about science fiction, conjuring up story ideas, and drawing illustrations. Over time they would create a world of mad scientists and futuristic space travelers, smooth-talking detectives and supernatural beings. Although he could draw a bit, Jerry generally took the role of writer, his more assertive personality driving the action. Writing in pithy sentences that could be squeezed into small narrative boxes and thought bubbles, he would conjure the concept, plot the story line, and develop the narrative. As the illustrator, Joe would envision the characters and scenes and then put pencil to paper as he brought the characters to life on cheap, brown butcher paper laid across his mother’s favorite cutting board.

Early in 1932 Jerry and Joe went to work on their own typewritten magazine titled Science Fiction: The Advanced Guard of Future Civilization. Once they had their densely typed, roughly illustrated master copy in hand, they dashed off to the library to mimeograph copies and began mailing them to fellow fans within the free-ranging science fiction network. Science Fiction would also be sent to the publishers of the best zines, in hopes that one of them would purchase a piece of content, or, at least, recognize the talent of the young creators.

The third edition of Science Fiction featured a story entitled “The Reign of the Super-Man,” in which a bald, diabolical chemist sets out to use a substance derived from a meteor to turn himself into an evil genius with the power to dominate the world. Although most of the stories in Science Fiction were written by Jerry and illustrated by Joe, “The Reign of the Super-Man” was signed with the byline Herbert Fine. The two amateurs probably thought the pen name was a professional touch that would create the illusion that there was another writer in their limited stable of contributors. Plus, it added a bit of protection against any prejudiced publishers who might like the story but suspect that the writers were Jewish based on their real names.

Jerry and Joe’s “The Reign of the Super-Man” played off the grim realities of the Great Depression. In the story, treacherous Professor Smalley lures destitute, homeless men from soup kitchens to serve as guinea pigs for his hideous experiments: “With a contemptuous sneer on his face, Professor Smalley watched the wretched unfortunates file past him. To him, who had come of rich parents and had never been forced to face the rigors of life, the miserableness of these men seemed deserved.”

It was a good tale, but it was not the page-turner the duo had hoped for. What was it? Jerry and Joe would tackle that question later. The pair were in what should have been their last year at Glenville High, and the world of work was looming ahead—although they would both end up repeating that year because they lacked the grades to graduate.

In addition to hanging out with Joe, Jerry loved to spend time with his dad, Mitchell, who supported his youngest son’s creative endeavors. Maybe this support stemmed from Mitchell’s own abandoned dream of being a painter. Or perhaps he was just going easier on his youngest child than he had on the others, who had been expected to work part-time at the haberdashery, to do well in school, and to prepare to find good jobs (the boys) or good husbands (the girls). Then, in an instant, the family’s life changed forever.

On June 2, 1932, just after closing time, a neighboring merchant noticed that the haberdashery’s door was ajar. The interior lights were on, but Mitchell Siegel was nowhere in sight. The concerned shopkeeper pushed open the door and found Mitchell sprawled on the floor behind the counter—dead. The money in the cash register was gone, as were the three thugs who had robbed him. Initial police reports suggested that Siegel had been shot in the chest and found in a pool of blood behind the cash register. The coroner’s report later amended the scenario: Mitchell had suffered a fatal heart attack during the robbery. Either way, the Siegel family would never be the same.

Jerry’s mother fell into a deep depression. Her message to the children was cold and absolute: Never mention the robbery to anyone. All that the neighbors needed to know was that their father had died of a heart attack. Period. Relatives flocked to Sarah’s side, tried to console the kids, made sure that the bills were paid, and shook their heads over the tragedy. With the Great Depression bearing down, Mitchell’s income gone, and money tighter than ever, the family did the best they could. Devastated by the loss of his dad, Jerry withdrew even more into his science fiction world.

But a fire burned within him. He was more determined than ever to make it in the publishing business. He would work tirelessly to honor the memory of his hardworking father. He had no way of knowing that success was not far beyond the horizon. The shy, grieving, self-conscious, seemingly powerless teen could not foresee that his imagination would conjure up a muscular, all-powerful, super human who could deflect bullets, bend steel in his bare hands, soar into the sky, and protect the little guy from thugs and hoodlums like those who had caused his father’s death.

* CHAPTER 3 *

THE MAGIC OF THE MIX

BY 1934 NEWLY MINTED high school graduates Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster were operating their own comic art business. While their fellow Glenville graduates were taking introductory philosophy classes on college campuses, operating drill presses in factories, or searching for any work they could find, these offbeat science fiction devotees were pitching their ideas to professional editors and publishers. Fancying himself the business brains of the two-man outfit, Jerry took the lead in managing the enterprise. Concepts for new characters had to be put down on paper and sent out. Push. Letters had to be written to editors and publishers looking for content. Push. Push. Their primary targets were the syndicates that distributed comic strips to newspapers and the companies that were introducing a new kind of publication: comic books.

Jerry and Joe’s story of the Super-Man—that diabolical scientist who conducted gruesome experiments on unsuspecting homeless men—was still incubating in their minds. Then, according to Superman lore, late one night in the summer of 1934, the answer hit Jerry like a lightning bolt. They had it backward. The world had no need for an evil superman. The world needed a good superman—a trustworthy and powerful ally who would come to the rescue of regular people by protecting them from ruthless criminals, cheating businessmen, and corrupt politicians. With millions of people out of work, the streets full of crime, the stock market in ruins, and a war brewing in Europe, readers were starved for hope, inspiration, and a sense of power. A good superman could provide all that.

ACCORDING TO THE LORE, the essence of the character—the one the world would come to know—flashed into Jerry’s mind that restless night with the force of one of those sci-fi meteors crashing to Earth. In point of fact, the epiphany of the good superman sparked a long collaboration that would lead to the iteration of the character known today. The day after the epiphany, Jerry ran to Joe’s house, and the two began evolving the basic story line of the good superman. The next full-fledged version came several months later with the creation of an all-too-human hero the collaborators modestly dubbed “The Most Astounding Fiction Character of All Time!” This superman was strong, agile, and heroic but lacked extraordinary superpowers that would differentiate him from other heroes.

The few publishers who considered the proposal rejected it. Frustrated with the failure, Joe went into a rage and began destroying the manuscript. Jerry intervened but managed to save only the cover. The cover, showing the Superman leaping at a gun-wielding thug, was eerily reminiscent of Mitchell Siegel’s death. Still not quite right. The work continued.

As the writer, Jerry took the lead in developing the now-classic story line that finally emerged. Superman is born on the planet Krypton. His scientist father places him in a small rocket ship and launches him toward Earth just moments before Krypton erupts in devastating earthquakes and explosions that kill all the inhabitants. The spacecraft lands on Earth, where people discover the baby and take him to an orphanage in a small midwestern town. A family named Kent adopts him, gives him the name Clark, and raises him on a farm. After realizing the possibilities of his superhuman powers, Clark moves to the big city of Metropolis and becomes a reporter for a great metropolitan newspaper.

In times of trouble Clark sheds his street clothes and peels off his glasses to become Superman. He uses his powers to leap great heights, to hoist huge weights, to deflect bullets, to soar into the sky, and to subdue criminals. His only motives are to protect the innocent, to bring the guilty to justice, and to crusade for a better world. After saving the day, Superman returns to his guise as the mild-mannered Clark, who works at the newspaper with a gutsy “girl reporter” named Lois Lane. But Lois has little time for bespectacled, nerdy Clark. She only has eyes for Superman.