Marching to the Mountaintop: How Poverty, Labor Fights and Civil Rights Set the Stage for Martin Luther King Jr′s Final Hours

Ann Bausum

National Geographic Kids

Jim Lawson

In early 1968 the grisly on-the-job deaths of two African-American sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee, prompted an extended strike by that city's segregated force of trash collectors.Workers sought union protection, higher wages, improved safety, and the integration of their work force. Their work stoppage became a part of the larger civil rights movement and drew an impressive array of national movement leaders to Memphis, including, on more than one occasion, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.King added his voice to the struggle in what became the final speech of his life. His assassination in Memphis on April 4 not only sparked protests and violence throughout America; it helped force the acceptance of worker demands in Memphis. The sanitation strike ended eight days after King's death.The connection between the Memphis sanitation strike and King's death has not received the emphasis it deserves, especially for younger readers. Marching to the Mountaintop explores how the media, politics, the Civil Rights Movement, and labor protests all converged to set the scene for one of King's greatest speeches and for his tragic death.National Geographic supports K-12 educators with ELA Common Core Resources.Visit www.natgeoed.org/commoncore for more information.From the Hardcover edition.

The publisher and author gratefully acknowledge the review of proofs for this book by historian Michael K. Honey. For more information on the topic, consult Professor Honey’s definitive, award-winning account of the history, Going Down Jericho Road: The Memphis Strike, Martin Luther King’s Last Campaign (W. W. Norton & Company, 2007).

Published by the National Geographic Society John M. Fahey, Jr., CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Timothy T. Kelly, PRESIDENT Declan Moore, EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT; PRESIDENT, PUBLISHING Melina Gerosa Bellows, EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT; CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER, BOOKS, KIDS, AND FAMILY

Prepared by the Book Division Nancy Laties Feresten, SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, EDITOR IN CHIEF, CHILDREN’S BOOKS Jonathan Halling, DESIGN DIRECTOR, BOOKS AND CHILDREN’S PUBLISHING Jay Sumner, DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY, CHILDREN’S PUBLISHING Jennifer Emmett, EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, CHILDREN’S BOOKS Carl Mehler, DIRECTOR OF MAPS R. Gary Colbert, PRODUCTION DIRECTOR Jennifer A. Thornton, MANAGING EDITOR

Staff for This Book Jennifer Emmett, PROJECT EDITOR Eva Absher, ART DIRECTOR Lori Epstein, SENIOR ILLUSTRATIONS EDITOR Marty Ittner, DESIGNER Grace Hill, ASSOCIATE MANAGING EDITOR Joan Gossett, PRODUCTION EDITOR Lewis R. Bassford, PRODUCTION MANAGER Susan Borke, LEGAL AND BUSINESS AFFAIRS Kate Olesin, EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Kathryn Robbins, DESIGN PRODUCTION ASSISTANT Hillary Moloney, ILLUSTRATIONS ASSISTANT

Manufacturing and Quality Management Christopher A. Liedel, CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER Phillip L. Schlosser, SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT Chris Brown, TECHNICAL DIRECTOR Nicole Elliott, MANAGER Rachel Faulise, MANAGER Robert L. Barr, MANAGER

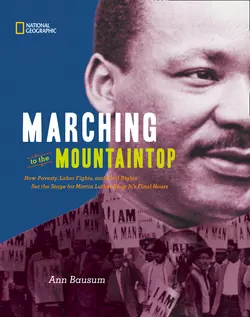

COVER: The cover illustration combines a view taken of Martin Luther King, Jr., on the day before his death with a scene of striking Memphis workers before the attempted protest of March 28, 1968. Endpapers replicate popular protest signs from Memphis civil rights events in 1968. Pickets march past armed troops on March 29, 1968 (title page). Garbage accumulates in the street of an African-American neighborhood in 1968 (table of contents).

The National Geographic Society is one of the world’s largest nonprofit scientific and educational organizations. Founded in 1888 to “increase and diffuse geographic knowledge,” the Society works to inspire people to care about the planet. National Geographic reflects the world through its magazines, television programs, films, music and radio, books, DVDs, maps, exhibitions, live events, school publishing programs, interactive media and merchandise. National Geographic magazine, the Society’s official journal, published in English and 33 local-language editions, is read by more than 38 million people each month. The National Geographic Channel reaches 320 million households in 34 languages in 166 countries. National Geographic Digital Media receives more than 15 million visitors a month. National Geographic has funded more than 9,400 scientific research, conservation and exploration projects and supports an education program promoting geography literacy. For more information, visit nationalgeographic.com (http://nationalgeographic.com).

For more information, please call 1-800-NGS LINE

(647-5463) or write to the following address:

National Geographic Society

1145 17th Street N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036-4688 U.S.A.

Visit us online at www.nationalgeographic.com/books (http://www.nationalgeographic.com/books)

For librarians and teachers: www.ngchildrensbooks.org (http://www.ngchildrensbooks.org) More for kids from National Geographic: kids.nationalgeographic.com (http://kids.nationalgeographic.com)

For rights or permissions inquiries, please contact National Geographic Books Subsidiary Rights: ngbookrights@ngs.org (mailto:ngbookrights@ngs.org)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bausum, Ann. Marching to the mountaintop : how poverty, labor fights, and civil rights set the stage for Martin Luther King, Jr.’s final hours / by Ann Bausum. — 1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. eISBN: 978-1-4263-0945-8 1. King, Martin Luther, Jr., 1929-1968—Juvenile literature. 2. King, Martin Luther, Jr., 1929-1968—Assassination—Juvenile literature. 3. Sanitation Workers Strike, Memphis, Tenn., 1968—Juvenile literature. 4. Labor movement—Tennessee—Memphis—History—20th century—Juvenile literature. 5. African Americans—Tennessee—Memphis—Social conditions—20th century—Juvenile literature. 6. Memphis (Tenn.)—Race relations—History—20th century—Juvenile literature. I. Title. E185.97.K5B38 2012 323.092–dc23 [B] 2011024661

Text copyright © 2012 Ann Bausum.

Compilation copyright © 2012 National Geographic Society.

All rights reserved. Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission from the publisher is prohibited.

v3.1

Version: 2017-07-05

For the people of Memphis, and for blacks and whites everywhere who have fought against racism, including my fourth-grade teacher—Christine Warren—who was on the front lines of school integration in 1966-67. All that, and you helped me love to read, too! Thank you, Mrs. Warren! —AB

CONTENTS

Cover (#ud6f8754a-3bb7-5392-b780-77ffbb947447)

Title Page (#ua5f29cb0-310c-592b-9146-8494953eb645)

Copyright (#u15bc6ee0-c48a-56bc-8aff-ba55dc705d10)

Dedication (#ue47ccc60-f7a6-590b-b79f-116e0ec83e8b)

Foreword by Reverend James Lawson (#ua7c6e20b-d31d-5acb-8c43-3b605b03193a)

Introduction (#u412c24e4-8c08-599f-aa2d-1d4222569bc8)

Cast of Characters (#uc794b79c-16cb-5005-ad8f-04082921156b)

CHAPTER 1 Death in Memphis (#ufec0ac29-4509-55eb-9062-078046f65bb3)

CHAPTER 2 Strike! (#ua480312b-f59f-5a5c-9908-b90da89d767f)

CHAPTER 3 Impasse (#ud3ae00bc-acfd-532e-9624-14798e897419)

CHAPTER 4 A War on Poverty (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 5 Marching in Memphis (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 6 Last Days (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 7 Death in Memphis, Reprise (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 8 Overcome (#litres_trial_promo)

Afterword (#litres_trial_promo)

Time Line (#litres_trial_promo)

King’s Campaigns (#litres_trial_promo)

Research Notes and Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

Resource Guide (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Illustrations Credits (#litres_trial_promo)

Citations (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

FOREWORD

By Reverend James Lawson

There are very rare, peculiar moments in history when we humans are allowed to catch a glimpse at the vision of a fairer world, and when we experience the nobility and joy of being fully alive as children of life. This book, Marching to the Mountaintop, describes such a moment in the emergence of a nonviolent direct action movement (the intensified years in the journey of Martin Luther King, Jr., 1953-1973, and the garbage workers strike of Memphis 1968).

Ann Bausum has given us a beautiful and inspiring account capturing much of the drama of our struggle in a comprehensive fashion and also pointing us towards the larger frame of what is called the civil rights movement. I hope that you will drink deeply from the portrait of Dr. King—my Moses and colleague from 1955 to 1968. I urge you to also hear and feel the character, courage, and compassion of the 1,300 workers who had the temerity to insist “I am a man.”

I like to call the civil rights movement the second American revolution. The first one in 1776 excluded the human rights of women, Native Americans, millions of slaves, black people, Mexican Americans, Chinese Americans, and others. The second one was largely nonviolent (a concept coined by Mohandas K. Gandhi, the father of the science of nonviolent social change) and effectively caused our Constitution to be declared as including all residents of our land.

All through this book, you will see the sheer human dignity of ordinary people, younger and older, provoked by the example of the 1,300 workers and their wives and families. These working families did not allow the nature of their daily hard labor and its ethos of racism to blot out their humanity or their insistence that one day their work would lift them out of abject poverty. This quest for human dignity—equality, liberty, and justice for all—is the soul of the sanitation strike and the civil rights movement. After all, we humans have been birthed to be human—in the likeness of God. Nothing less can even begin to satisfy our lives.

The Memphis strike was not the last mass direct action campaign of that era. It was the last campaign in which Dr. King participated. In 1969 we Memphians were again engaged in a massive direct action effort, which began the restructuring of our public schools. More than 200,000 people, including more than 70,000 students, participated. Because of that campaign, I, and others, spent Christmas 1969 in the county jail.

Martin Luther King, Jr., and James Lawson became allies in the fight for African-American rights from their first meeting in 1957. At King’s urging, Lawson used his keen understanding of the power of nonviolence to train many of the young people who went on to play significant roles in the civil rights movement. In 1968, Lawson (above, holding sign) collaborated with King, local youths, labor leaders, and other supporters to champion the need for workers to receive fair treatment from “King Henry,” Memphis mayor Henry Loeb.

I hope that you the readers will see yourselves in these pages. Our work for human dignity and truth is not over. Each generation must do its share. Racism, sexism, violence, greed, and materialism are still with us. You must continue the personal and community nonviolent march toward the promised land.

A Note From the Publisher: Reverend Lawson’s views on the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., differ from the account offered in this book, which is based on the official record of the investigation. Drawing on other information, some historians, including Reverend Lawson, believe there are errors in this record. History is not fixed, and controversy is useful. We challenge all budding historians to seek to uncover the truth of this investigation and other historical episodes that further our understanding of ourselves. To read the trial records and draw your own conclusions, please consult The 13th Juror (CreateSpace, 2009).

INTRODUCTION

“Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen, Nobody knows my sorrow. Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen. Glory, hallelujah!”

Chorus from a freedom song based on an African-American spiritual

As I remember it, the chore of taking out the trash fell to me every week of my childhood. My family might disagree, but if anything could trick my memory into believing this statistic it is my recollection of the garbage itself. Pungent. Disgusting. Foul. Unforgettable.

Back then, garbage was truly garbage. To take out the trash during the 1960s meant to get up close and personal with a week’s worth of refuse in the most intimate and repulsive of ways. No one had yet invented plastic garbage-can liners or the wheeled trash cans we have today. At that time our family’s garbage went into aluminum cans with clanging metal lids. And the garbage went in naked.

In 1968, when I was ten years old, people really cooked. Recipes started with raw ingredients, and the garbage can told the tales of the week’s menu. Onion skins, carrot peelings, and apple cores. The grease from the morning’s bacon. Half-eaten food scraped from plates in the evening. The wet, smelly, slippery bones of the chicken carcass that had been boiled for soup stock. Mold-fuzzy bread. Spoiled fruit. Slimy potato peels. Scum-coated eggshells. Then add yesterday’s newspapers. Used Kleenex. Cat-food cans lined with sticky juices. Everything went into the same metal can out the back door of our home in Virginia.

The story of our garbage multiplied itself to infinity at homes throughout the nation. In communities where temperatures soared, garbage baked in the summer heat like some witch’s stew until foul odors broadcast its location, flies bred on the vapors, and maggots hatched in the waste. Wet, raw, saturated with rancid smells that lingered long after the diesel-powered truck had lumbered away: That was the garbage of the 1960s. The people who collected the trash were always male, and we called them, simply, garbagemen.

It’s universal: Young people take out the trash everywhere, including in Memphis during the 1968 strike.

This book is about the story of garbage in one city—Memphis, Tennessee—and the lives of the men tasked with collecting it during 1968. These men, all of whom were African American, labored brutally hard for such meager wages that many of them qualified for welfare. Six days a week they followed their noses to garbage cans (curbside trash collection had yet to become the norm); then they manhandled the waste to the street using giant washtubs. The city-supplied tubs corroded with time, leaving their bottoms so peppered with holes that garbage slop dripped onto the bodies and clothes of the city’s garbagemen as they labored.

During the 1960s the sanitation workers of Memphis showed up for work every day knowing they would be treated like garbage. By the end of the day they smelled and felt like garbage, too. Unfairness guided their employment, and racism ruled their workdays. So passed the lives of the garbagemen of Memphis until something snapped, one day in February 1968, and the men collectively declared, “Enough is enough.” Accumulated injustices, compounded by an unexpected tragedy, fueled their determination. Just like that they went out on strike, setting in motion a series of events that would transform their lives, upend the city of Memphis, and lead to the death of the nation’s most notable — and perhaps most hated — advocate for civil rights.

Labor relations, human dignity, and a test of stubborn wills drove developments that spring in Memphis, Tennessee. Behind this union of worker rights and civil rights stood the men expected to handle one ever present substance: garbage.

CAST OF CHARACTERS

Southern ChristianLeadership Conference

In 1957, heartened by the successful outcome of the Montgomery bus boycott, key organizers team up with colleagues from other communities to form the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, or SCLC, and advocate for social change through the use of nonviolence. Key participants:

Martin Luther King, Jr., president from 1957 until his death in 1968.

Ralph D. Abernathy, treasurer, King’s closest colleague, and the man who succeeds him as organization president.

Lieutenants, such as Hosea Williams and Jesse Jackson (standing left and center with King and Abernathy at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, April 3, 1968), as well as Bernard Lee, James Orange, and Andrew Young.

Authorities

Lyndon B. Johnson, President of the United States (1963-1969).

J. Edgar Hoover, director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the chief force behind FBI campaigns to spy on and discredit Martin Luther King, Jr.

Former FBI agent Frank Holloman, director of the Memphis fire and police departments, and the department’s 800 officers, including undercover staffers Marrell “Max” McCullough, Ed Redditt, and Willie Richmond.

The Memphis Movement

On February 24, 1968, local clergy establish a strike-support organization called Community on the Move for Equality, or COME.

James Lawson, an associate of King’s with deep experience in the use of nonviolence and a local Methodist minister, becomes the group’s leader.

Other key organizing ministers include Presbyterian Ezekiel Bell, Clayborn Temple’s white leader Malcom Blackburn, Baptist minister and local judge Benjamin Hooks, AME leader H. Ralph Jackson, Baptist minister James Jordan, Baptist minister Samuel “Billy” Kyles, Baptist minister and youth organizer Harold Middlebrook, and AME minister Henry Starks (president of the association of local African-American ministers).

Charles Cabbage (left) and CobySmith (right), who had founded the Black Organizing Project (BOP) in 1967, question the exclusive use of nonviolence as a force for change; they maintain an uneasy alliance with COME, especially after setting up a militant offshoot to BOP known as the Invaders with associates such as Calvin Taylor.

Other notable strike supporters include local activist Cornelia Crenshaw, Dick Moon (the university chaplain who mounts a hunger strike in April 1968), Maxine Smith (executive director of the local chapter of the NAACP), NAACP president Jesse Turner, and white Methodist minister Frank McRae (who tries to persuade the Memphis mayor to settle the strike).

Labor

Public workers organize the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, or AFSCME, during the 1930s. By 1968 the organization represents almost 400,000 members in nearly 2,000 local chapters, including Memphis Local 1733.

T. O. Jones, president of AFSCME Local 1733, who helped found the fledgling union in 1963, stands in the front lines throughout the 1968 strike.

Jerry Wurf, international president of the union since 1964, assumes personal responsibility as the advocate for members of Local 1733.

AFSCME field services director P. J. Ciampa serves as the union’s chief liaison with the striking workers.

Other key national players from AFSCME include union organizer Jesse Epps (above), Bill Lucy (the highest ranking African American at AFSCME in 1968), and Joe Paisley (the Tennessee representative for AFSCME).

Workers such as Robert Beasley, Clinton Burrows, Ed Gillis, J. L. McClain, James Robinson, Taylor Rogers, Joe Warren, and Haley Williams are among the 1,300 men who fight for recognition as human beings and as members of a union; the vast majority are sanitation workers (1,100), but another 230 hold jobs in the sewer and drainage division of the department of public works.

Other local labor supporters include members of the United Rubber Workers Union (Local 186), Taylor Blair (a white union agent who advocates settlement), Tommy Powell (president of the Memphis Labor Council and a local white), and Bill Ross (a white who leads the local council of AFL-CIO affiliates).

Management

Henry Loeb, mayor of Memphis, 1968-1972, former local business owner, former public works commissioner (1956-1960), and former mayor (1960-1963).

Memphis City Council, thirteen members elected for service beginning January 1968 to fill seven district seats and six at-large seats, including twelve men (three of whom are African American) and one woman.

Charles Blackburn, director of the Memphis department of public works, which employs sanitation and street workers.

Mediators

James Reynolds, U.S. Department of Labor undersecretary (wearing glasses, back to camera, seated with, counterclockwise, AFSCME representatives Bill Lucy, Jerry Wurf, and P. J. Ciampa).

Frank Miles (far left), Memphis labor advocate and local businessperson.

Chapter 1

DEATH

IN MEMPHIS

“It was horrible,” said the woman.

One minute she could see a sanitation worker struggling to climb out of the refuse barrel of a city garbage truck. The next minute mechanical forces pulled him back into the cavernous opening. It looked to her as though the man’s raincoat had snagged on the vehicle, foiling his escape attempt. “His body went in first and his legs were hanging out,” said the eyewitness, who had been sitting at her kitchen table in Memphis, Tennessee, when the truck paused in front of her home. Next, she watched the man’s legs vanish as the motion of the truck’s compacting unit swept the worker toward his death. “The big thing just swallowed him,” she reported.

“We shall overcome. We shall overcome.

We shall overcome some day-ay-ay-ay-ay.

Deep in my heart, I do believe,

We shall overcome some day.”

Freedom song adapted from a gospel hymn for a southern labor fight during the 1940s

In 1968 many Memphis residents stored their trash in uncovered 50-gallon drums. Frequent rains added to the soupy, unsavory nature of the garbage that workers transferred to waiting trucks. The exclusively African-American workforce took its orders from white supervisors (above).

Unbeknownst to Mrs. C. E. Hinson, another man was already trapped inside the vibrating truck body. Before vehicle driver Willie Crain could react, Echol Cole, age 36, and Robert Walker, age 30, would be crushed to death. Nobody ever identified which one came close to escaping.

Cole and Walker wore raincoats for good reason on February 1, 1968. At the end of a wet workday, Willie Crain’s four-man crew had divvied up the truck’s available shelter for the trip to the garbage dump. Elester Gregory and Eddie Ross, Jr., squeezed into the driver’s cab with Crain and left the younger members of the crew with two choices. They could hold on tight to exterior perches while the truck passed through torrential rains. Or they could climb inside the truck’s garbage barrel, wedged between the front wall of the vessel and the packing arm that pressed a load of refuse against the rear of the truck. Walker and Cole opted for the dryer and seemingly more secure interior space.

Rain or shine, the 1,100 sanitation workers of Memphis collected what amounted to 2,500 tons of garbage a day. This all-male, exclusively African-American staff worked six days a week with one 15-minute break for lunch and no routine access to bathroom facilities. Their pay was based on their garbage routes, not their hours worked, so there was no overtime compensation when the days ran long. Workers supplied their own clothing and gloves, toted rain-saturated garbage in leaky tubs supplied by the city, and had no place to shower or to change out of soiled clothes before returning home. Even though the men worked full-time, their earnings failed to lift their families from poverty. To make ends meet, many found extra jobs, paid for groceries with government-sponsored food stamps, lived in low-income housing projects, and made use of items scavenged during their garbage runs.

The men toiled under a system with eerie echoes of the pre–Civil War South, what some called the plantation mentality. Whites worked as supervisors. Blacks, who made up almost 40 percent of the city’s population, performed the backbreaking labor. Bosses expected to be addressed as “sir.” Workers endured being called “boy,” regardless of their ages. Whites presumed to know what was best for “our Negroes,” and blacks tolerated poor treatment for fear of losing their jobs, or worse. City officials had no motivation to recognize the fledgling labor union that sought to protect the workers and to advocate for their rights. As a result, employees “acted like they were working on a plantation, doing what the master said,” recalled sanitation worker Clinton Burrows.

Memphis residents, or Memphians, called their sanitation workers garbagemen, walking buzzards, and tub toters, a name that reflected the washtubs they used for ferrying garbage from backyard storage barrels to city trucks. Workers (above, R. J. Sanders) balanced the large tubs on their heads or pushed them in three-wheeled carts.

Garbage collectors faced back injuries and other strains because of the physical demands of the work, and they fretted about the use of unsafe equipment. Willie Crain’s truck had been purchased on the cheap in 1957 at a time when Henry Loeb ran the department of public works. By 1968, when Loeb returned to public office as the newly elected Memphis mayor, the city had begun replacing the old trucks. Two of the vehicles, including Crain’s truck, had been retrofitted with a makeshift motor after the unit’s trash-compacting engine had worn out. As best as anyone could figure after the deaths of Echol Cole and Robert Walker, a loose shovel had fallen into the wiring for the replacement motor and had accidentally triggered the reversal of the trash compactor.

Like those of other sanitation workers, the families of Cole and Walker managed paycheck to paycheck, leaving no reserves for emergencies. Their jobs came without the benefits of life insurance or a guarantee of support in the case of work-related injury or death. Mayor Loeb honored the victims by lowering public flags to half-mast, but he offered scant assistance to their survivors. The city contributed $500 toward the men’s $900 funerals and paid out an extra month’s wages to Cole’s widow and the widow of Walker (who was pregnant).

The deaths of Cole and Walker wrapped up a particularly bad week for African Americans employed at the department of public works. This unit handled garbage collection, street repairs, and other city maintenance. On January 30, two days before the sanitation-worker fatalities, 21 members of the sewer and drainage division had been sent home with only two hours of “show-up pay” because of bad weather. The previous public works director had kept staff employed regardless of the weather, but Mayor Loeb had ordered Charles Blackburn, his new director, to return to Loeb’s old rainy-day policy from the 1950s. In a climate where rain fell frequently, workers lost their ability to predict their income. “That’s when we commenced starving,” explained road worker Ed Gillis.

Street workers turned to Thomas Oliver Jones for help. T. O. Jones was among 33 sanitation workers who had started a strike in 1963 and lost their jobs. When officials were pressured to rehire the workers, Jones refused to rejoin the force. Over time he established a fledgling union for public works employees and gained recognition for his small group by the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, better known as AFSCME. Jones’s group called itself Local 1733 in honor of the 33 men fired during the 1963 strike. Jones tried to lead another walkout in 1966. This time 500 workers agreed to strike, but the work stoppage collapsed after a local judge declared the strike illegal. “All city employees may not strike for any purpose whatsoever,” the judge declared. This injunction, or prohibition against striking, had never been challenged in court, so it remained in force and discouraged further strikes. Nonetheless, Jones continued to quietly recruit members for Local 1733 and became its unofficial spokesperson.

“THERE wasn’t too much opportunity for a black man at that time. Really wasn’t no other jobs hardly to be found. I was at a point I had to take what I could get.”

Taylor Rogers, who became a Memphis sanitation worker about 1959

Jones raised the men’s rainy-day concerns with Charles Blackburn and left the meeting thinking the public works director had agreed to pay the 21 men their missing wages. Blackburn said he would reconsider the rainy-day policy, too, and, within a few days, he instructed supervisors to try to keep everyone fully employed regardless of the weather. During that same period, Panfilo Julius Ciampa, field director for Washington, D.C.-based AFSCME, visited Memphis. Jones arranged for his union contact to meet the new public works director on February 1. P. J. Ciampa learned that Blackburn was a personal friend of the newly elected mayor and had gained appointment to the job after an unrelated career in insurance work. He would later describe Blackburn as “a guy who didn’t know a sanitation truck from a wheelbarrow.”

By 1968 the city of Memphis had replaced most of its garbage trucks with a rear-loading model (above, carrying unidentified workers). Echol Cole and Robert Walker died in an older side-loading vehicle nicknamed the wiener barrel because of its rounded shape. Their fatalities followed the deaths of two other sanitation workers during a 1964 truck rollover accident.

The men toiled under a system with eerie echoes of the pre–Civil War South, what some called the plantation mentality. Whites worked as supervisors. Blacks performed the backbreaking labor.

Their afternoon meeting took place shortly before

Willie Crain’s truck began crushing two sanitation workers to death. Jones learned of the accident almost immediately. As he drove back from taking Ciampa to the Memphis airport, Jones followed a hunch that trouble was brewing and pursued an emergency public works vehicle that turned out to be racing toward the reported accident. Events snowballed as the news spread. Surviving workers knew they could just as easily have lost their own lives. They grew offended when the city didn’t cover the full costs of burying the victims. They fretted over the potential for lost wages during bad weather. They worried about how to survive on the money they earned even at full employment. And they fumed when the 21 workers opened their pay envelopes the following week and discovered no boost in pay for the rainy day of January 30.

Something snapped—or perhaps ignited—under the weight of these pressures in a system run with that plantation-style mind-set. In theory, slavery had ended 100 years earlier, but blacks in Memphis during 1968 had more in common with African-American slaves who had worked the region’s cotton fields than with the whites who ran Memphis businesses, served in city government, and covered the local news. Even poor whites, thanks to decades of segregated southern living, focused more attention on their racial superiority over blacks than the common interests they and blacks could have pursued through unions for higher wages and better working conditions. Poverty, racial isolation, and a history of voter intimidation left blacks underrepresented and their needs ignored.

“Nobody listens” to black people, observed Maxine Smith, executive director of the Memphis branch of the NAACP. “Nobody listened to us and the garbage men through the years. For some reason, our city government demands a crisis” before noticing African-American concerns.

Whites may not have seen it coming, but a crisis of epic proportions loomed on the horizon for Memphis, Tennessee.

Chapter 2

STRIKE!

“I’m ready to go to jail,” announced union organizer T. O. Jones.

“Why are you going to jail?” asked Charles Blackburn.

Jones, having excused himself to change into khaki pants—jail clothes—reminded the new public works director of the court injunction that prohibited strikes by Memphis public workers. Blackburn had offered no resolution of the list of demands Jones had just shared with him, demands that he had developed earlier that evening during a meeting with more than 700 department workers. Key principles included union recognition, pay increases, overtime compensation, full employment regardless of weather, and improved worker safety. Now Jones knew the men would strike.

“Oh, workers can you stand it? Oh, tell me how you can.

Will you be a lousy scab, or will you be a man?

Which side are you on, oh, which side are you on?

Which side are you on, oh, which side are you on?”

Verse from a labor song written in 1932 by Florence Patton Reece, a coal miner’s wife

Among the ways mayor Henry Loeb (above, walking with striking workers to their February 13 meeting) offended blacks was to mispronounce Negro, the era’s term for African Americans, as the racism-laced Nigra. In 1968 blacks refused to contribute their garbage for collection by strike-breaking workers. Uncollected, the waste accumulated by the week (above).

“He gives us nothing, we’ll give him nothing,” yelled one of the men when waiting workers learned of Blackburn’s stance. Those gathered held no official vote on whether or not to strike; they just reached a collective agreement to quit working. Maybe city officials would take notice if the garbage stopped being picked up and road repairs ceased.

The next morning, empty work barns must have erased whatever illusions Blackburn held about the submissiveness of his workforce. Only 170 of the city’s 1,100 garbage workers reported for duty on Monday, February 12. Just 16 members of the 230-man street crew appeared. Almost without warning, more than 85 percent of the workforce had failed to show up for work. The numbers were even worse the next day. Some workers had reported on Monday because they hadn’t heard about the strike. Now they joined the walkout, too. Peer pressure kept others off the job. If employees kept working, they knew they’d hear about it back in the neighborhoods and churches they shared with the strikers. Better to stay home. Hundreds of enthusiastic men rushed to join the union.

Public Works Director Blackburn struggled to organize his skeletal workforce into the five-man crews required to run a garbage truck. On Monday he managed to staff 38 garbage trucks, leaving as many as 150 vehicles idle for the day. By Wednesday he could fill only four. Every truck required a police escort in order to ensure that striking workers wouldn’t harass those few men who had stayed on the job.

P. J. Ciampa groaned at his AFSCME office on Monday when he learned of the Memphis walkout. This veteran organizer of countless labor strikes knew the Memphis timing was all wrong. Garbage strikes worked best in hot weather when garbage smelled its worst. Plus, city leaders would find it easy in February to hire unemployed agricultural workers to break the strike. And how were workers going to feed their families when their paychecks stopped coming? Usually union dues supported a strike fund, but Local 1733’s small membership base had created few assets. Furthermore, because southern business leaders and politicians disliked unions, the South was the hardest place to win a strike. On top of it all, in the face of an unexpected strike, public support would probably favor the newly elected leaders of Memphis. Never strike in anger, AFSCME officials always advised, and strike only when victory is certain. The Memphis strike looked like a disaster.

Holes peppered the corroded bottoms of many city-supplied washtubs, so garbage slop dripped onto the bodies and clothes of sanitation workers as they toiled. Tubs rested unused (above) during the 1968 strike. The Memphis action began just as a nine-day garbage strike ended in New York City (above, sweeping up some accumulated trash).

Tell the men to go back to work, Ciampa told Memphis labor leader Bill Ross by telephone. Ross refused, explaining that he had never seen such a determined group of men. “I said, buddy, I’m the only one white man in this building with 1,300 black souls out there. I’m not about to go out there and tell those people to go back to work. Now if you want to tell them to go back to work, you come down here and you do it yourself.”

Almost immediately the AFSCME field director flew to Memphis. By Monday night, three other AFSCME staffers had arrived, including Bill Lucy, a black Memphis native pulled from an assignment in Michigan. After meeting on Tuesday with Mayor Henry Loeb and with a room full of striking workers, Ciampa realized that nobody, not even T. O. Jones, could have stopped the strike. Jones “had to run to stay out front,” Ciampa would later say.

Ciampa could find no common ground with the mayor. Loeb insisted that negotiations take place in front of news reporters, a tough environment for reaching the compromises necessary for strike settlements. Ciampa sized up Loeb as insincere, close-minded, and happy to make comments that played well to his white citizen base while avoiding serious negotiation. Meanwhile, Ciampa, a tough-talking negotiator with an Italian-American accent, struck Loeb as rude and intrusive, and Ciampa’s assertive northeastern style grated against other whites, too. After Ciampa directed a few choice comments at the mayor—“Oh, put your halo in your pocket and let’s get realistic”; “Because you are mayor of Memphis it doesn’t make you God”; and “Keep your big mouth shut!”—orange bumper stickers reading “Ciampa Go Home” appeared all over Memphis. Within days AFSCME international director Jerry Wurf would decide to take personal charge of the negotiations, leaving Ciampa to coordinate strategy regarding the workers.

Traditionally, striking workers would set up picket lines and march with protest signs at their places of work. Replacement laborers, known as scab workers, would have to “cross the picket lines” and face verbal harassment by strikers in order to get to work. But Ciampa’s team and local union leaders worried that this aggressive approach might backfire in the racially charged South. They didn’t want to give members of the city’s almost entirely white police force an excuse to attack black strikers. Instead, strike organizers turned to tried-and-true forms of nonviolent civil disobedience: mass meetings, peaceful marches, boycotts, and so on. Such strategies had worked in past labor fights and were central to the ongoing civil rights movement led by Martin Luther King, Jr.

“WE’VE got to stay together in the union to win the victory. Strength is in numbers. We must stay together for however long is necessary—a day, a week, a month.”

P. J. Ciampa, AFSCME field director, addressing workers on February 13, 1968

The first mass march occurred the afternoon of Tuesday, February 13, day two of the strike. T. O. Jones and Bill Lucy led a formation of more than 800 workers, walking in rows of four or five men, from their union meeting place in north Memphis to downtown. They clapped, cheered, and sang freedom songs as they marched a distance of about five miles to city hall. “The men are here,” Lucy told the mayor. “You said, ‘Any men you want to bring down to talk to me, I’ll talk to them.’ Here they are.” At first Loeb misunderstood the size of Lucy’s group and asked him to escort the men into the mayor’s office. Soon he corrected himself and met workers in a large assembly hall.

Loeb’s so-called plantation-mentality approach backfired when he spoke to the workers as if they were children—humoring, scolding, and pressuring them to return to work. To the mayor’s shock, the men laughed at him.

Strike organizers credited Henry Loeb (above, at desk, during early negotiations) with becoming their best ally because his attitudes and behavior united blacks (below, marching on February 23) in their opposition to the city.

They clapped, cheered, and sang freedom songs as they marched a distance of about five miles to city hall. “The men are here,” Lucy told the mayor. “You said, ‘Any men you want to bring down to talk to me, I’ll talk to them.’ Here they are.”

When Loeb expressed his empathy for them by using the expression, “I’d give you the shirt off my back,” one of the men called in reply, “Just give me a decent salary, and I’ll buy my own.” The workers’ cheekiness and disrespect infuriated the mayor. Loeb vowed to get the garbage collected with or without the men’s help. “Bet on it!” he declared as he stormed out of the meeting.

Loeb was a well-educated business-owner-turned-politician. Three generations of his family had exploited black workers and amassed a fortune in the family laundry business. His father had prevented black washerwomen from organizing a union or striking for better pay by filling their jobs from the ranks of the unemployed. Employees put up with miserable wages because some job was better than no job. When Henry Loeb became public works director in the 1950s, he brought along his family business mind-set. As director he bought the cheapest of equipment, instituted the program of staff cuts on rainy days, justified unpaid overtime by offering paid vacation, and beat back every attempt to form unions. For Henry Loeb, the 1968 strike became a battle of wills—mayor against rebellious blacks. If he just held out long enough, he believed, the workers would give up. Early in the strike, Loeb told a white acquaintance and union advocate that his father “would turn over in his grave if he knew he had ever recognized a damn union,” Taylor Blair recalled. “I knew there wasn’t much point in arguing with a fellow like that because he was trying to uphold what his daddy had said.”

“THIS IS just a warning. Please don’t bring another damn truck out of that gate. Do you love your family? Please, please.”

Anonymous note sent by a strike supporter to a worker who continued to collect garbage

Loeb suspended settlement negotiations soon after his first meeting with the workers, and he announced that the city would begin replacing workers two days later. To poll the striking workers, union officials asked them to stand if they wanted to keep fighting. “They stood in unison—1,000 plus. They’re not going back,” an AFSCME official reported. By Friday Loeb had recruited replacements for only a fraction of the missing workers. Most whites dismissed garbage collection as beneath them, and only the most desperate of African Americans agreed to work against the cause of fellow blacks.

The city developed emergency rules to cope with the labor shortage. Trash collection dropped from twice to once a week. City officials instructed citizens to haul their trash to the curb. They encouraged families to include food waste in their trash—left uncollected it would encourage breeding of the city’s persistent population of rats—but to store other trash until the strike ended. Burning garbage remained illegal. Boy Scout groups volunteered to carry garbage barrels to curbs for the elderly, or even to haul trash to emergency dump sites. Others earned cash from such chores.

Members of the city council struggled to find their roles in the growing crisis. Like the mayor, they were new to their jobs and to a weeks-old governance system. The mayor insisted that he alone could negotiate on behalf of the city, and he became angry whenever council members tried to settle the strike. The ten whites on the council (including the council’s sole female member) saw little reason to challenge his authority, and the three blacks on the council lacked the political power to argue otherwise.

After the strike carried on into a second week, though, black councillor Fred Davis, chair of the city’s public works committee, offered to meet with workers to discuss their grievances. The February 22 session deteriorated after union reps recruited hundreds of workers to march on city hall and crowd the council chamber. Volunteers arrived with more than 100 loaves of bread, and wives of striking workers made bologna sandwiches for the group. Workers applauded as union reps and supportive ministers spoke forcefully on their behalf, and they refused to leave without having their demands met. Committee members struggled to construct a settlement resolution that could be presented to the full council for approval the next day. It took more than an hour to persuade T. O. Jones and the men to accept the one-day delay.

Workers stood and cheered before leaving the hall. They vowed to return on February 23 for the council vote. If all went as promised, the strike would be over the next day.

Chapter 3

IMPASSE

“Let’s keep marching,” urged James Lawson. “They’re trying to provoke us. Keep going,” he said.

The Methodist minister watched as a string of police cars edged closer to retreating workers. Bumper touching bumper, the cars crowded against the rows of marchers, herding them into a tighter formation. Lawson recognized the potential for conflict from his years of experience with the civil rights movement. Workers and accompanying family members needed to walk off some of their anger and disappointment over the latest city council meetings. Strikers had left city hall on February 22 anticipating a settlement of their grievances.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/ann-bausum/marching-to-the-mountaintop-how-poverty-labor-fights-and-civil/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Ann Bausum и National Kids

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Детская проза

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: In early 1968 the grisly on-the-job deaths of two African-American sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee, prompted an extended strike by that city′s segregated force of trash collectors.Workers sought union protection, higher wages, improved safety, and the integration of their work force. Their work stoppage became a part of the larger civil rights movement and drew an impressive array of national movement leaders to Memphis, including, on more than one occasion, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.King added his voice to the struggle in what became the final speech of his life. His assassination in Memphis on April 4 not only sparked protests and violence throughout America; it helped force the acceptance of worker demands in Memphis. The sanitation strike ended eight days after King′s death.The connection between the Memphis sanitation strike and King′s death has not received the emphasis it deserves, especially for younger readers. Marching to the Mountaintop explores how the media, politics, the Civil Rights Movement, and labor protests all converged to set the scene for one of King′s greatest speeches and for his tragic death.National Geographic supports K-12 educators with ELA Common Core Resources.Visit www.natgeoed.org/commoncore for more information.From the Hardcover edition.