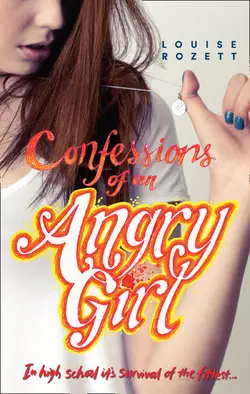

Confessions Of An Angry Girl

Louise Rozett

Rose Zarelli, self-proclaimed word geek and angry girl, has some CONFESSIONS to make…#1: I'm livid all the time. Why? My dad died. My mom barely talks. My brother abandoned us. I think I'm allowed to be irate, don't you?#2: I make people furious regularly. Want an example? I kissed Jamie Forta, a badass guy who might be dating a cheerleader. She is now enraged and out for blood. Mine.#3: High school might as well be Mars. My best friend has been replaced by an alien, and I see red all the time. (Mars is red and "seeing red" means being angry—get it?)Here are some other vocab words that describe my life: Inadequate. Insufferable. Intolerable. (Don't know what they mean? Look them up yourself.) (Sorry. That was rude.)

ROSE ZARELLI, self-proclaimed word geek and angry girl, has some confessions to make...

1 I’m livid all the time. Why? My dad died. My mom barely talks. My brother abandoned us. I think I’m allowed to be irate, don’t you?

2 I make people furious regularly. Want an example? I kissed Jamie Forta, a badass guy who might be dating a cheerleader. She is now enraged and out for blood. Mine.

3 High school might as well be Mars. My best friend has been replaced by an alien, and I see red all the time. (Mars is red and “seeing red” means being angry—get it?)

Here are some other vocab words that describe my life: Inadequate. Insufferable. Intolerable.

(Don’t know what they mean? Look them up yourself.)

(Sorry. That was rude.)

“Thanks for the carnation. It’s pretty.”

“You’re welcome,” Jamie says with that slight smile that makes the back of my neck tingle with warmth.

I don’t want to be just friends with Jamie Forta.

What would happen if I leaned over and kissed him? Do I have it in me to do that? Would he stop me?

I suddenly hear myself breathing too hard and too loud. I start to feel stupid, dumb, needy. Fifteen minutes ago, Jamie Forta said we were just friends, and so what do I do? Fantasize about kissing him. It’s crazy. This whole thing is crazy.

Confessions of an Angry Girl

Louise Rozett

www.miraink.co.uk (http://www.miraink.co.uk)

For Alex Bhattacharji,

who helps me—in so many ways—to do the work I love

Thanks to The Feedback Pack—Alex Bhattacharji, Jean & Ron Rozett, Michael Rozett, Lynn Festa, Spencer Kayden, Elisa Zuritsky, Tim Brien, Rachael Dorr, Monica Khanna, and Becky Sandler. You’re all so darn smart.

Special thanks to Barb & Sean Patrick, for arranging a phenomenal day for me at Fairfield Ludlowe High School. And of course, special thanks to Hamden High School, and to all the great teachers and wonderful friends I encountered there who helped make high school everything it should be. (Truly!)

Super special thanks to Natashya Wilson of Harlequin Teen, who challenged me to find out what was really making Rose Zarelli so mad, and to Emmanuelle Morgen of Stonesong. Thank you both for taking a chance on our angry girl—and on me.

Contents

Prologue (#ub332ccd2-40d0-565a-958f-14bdef7108ef)

Fall (#u9cb6bd00-6a19-5b37-9951-f1d2cb228390)

Chapter 1 (#u4b74817f-4096-5b58-ac89-9cbd79fa6cc8)

Chapter 2 (#ud78b6668-7ae3-5fad-b735-4bb5a6f80a65)

Chapter 3 (#ua35cb60e-585e-5db7-ab1d-1a67ea4f03fb)

Chapter 4 (#u47b2ddfd-742e-5637-b0ee-f55db6fc21ad)

Chapter 5 (#uece2f8b0-59ab-583e-beb7-c1f1a69e3e51)

Chapter 6 (#u8541a9f5-5ea2-5543-9662-b438950442ba)

Chapter 7 (#ucbdf2e68-f7ec-5744-87fb-756364542583)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Winter (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Spring (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Preview (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE

THIS, DEAR READER, is a tale of the hell of high school. Of being dropped into a world where it seems like everyone is speaking a foreign language. Where friends become enemies and enemies become nightmares. Where life suddenly seems like a string of worst-case scenarios from health-class movies.

This is a story about a girl with a stellar vocabulary who is four years away from college and a year and a half away from a driver’s license. About a girl trapped in a hostile universe where the virginity clock is ticking down—relentlessly—with zero consideration for her extenuating, traumatic, life-altering circumstances.

This is a story about death. About the occasional panic attack, the inability to shut up and high school in the suburbs without a cell phone.

Read it and weep.

FALL

plummet (verb): to fall suddenly, sharply, steeply

(see also: to start high school)

1

“JAMIE. YOU GONNA eat that? Jame. That bagel. You gonna eat it? ’Cause I’m really hungry, man. My mom threw me out before I could eat my cereal. And she didn’t give me a dime.”

Jamie slides the half bagel dripping with butter over to Angelo without looking up from drawing on the back of his notebook. Angelo is silent for thirty seconds, and then he’s on the make again, looking for someone else’s leftovers. The PA system screeches with feedback, and the din gets louder as everyone tries to talk over it.

“Good morning, Union High. Please rise for the Pledge of Allegiance.” The brightly colored riot-proof seats welded to the cafeteria tables left over from the 1970s creak as period-one study hall drags itself to its feet to say words that we haven’t thought about and don’t understand—or can’t make ourselves say. Jamie stays seated, his pencil slowly tracing the lines of his drawing.

“Forta, is that your assigned seat?” Jamie nods at Mr. Cella, the gym teacher who would probably rather be anywhere other than chaperoning first-period study hall. “Then get out of it and join the rest of us in pledging allegiance to this fine country of ours,” Mr. Cella says kind of sarcastically as he moves on to the next table.

Jamie looks around and sees that people are in the middle of the pledge. By the time he stands up, everyone is sitting down already.

“Jame, you got any money? I’m still starvin’, man. I just need another bagel or a piece of toast or something. I’ll pay you back tomorrow. I just need, like, a dollar. You got that? Could I have it?”

Jamie reaches into his pockets for change, coming up with a quarter. He hands it to Angelo, who looks majorly disappointed.

“This all you got, Jame?”

“Here. Here’s seventy-five cents.” The slightly sweaty freshman girl in the blue cotton sweater at the end of the table, also known as me, reaches out three quarters, glad to have made it through another pledge to the flag without throwing up. I don’t exactly feel like swearing my allegiance to America these days, and I probably won’t for a long time, if ever.

Angelo looks at the quarters suspiciously. Maybe he’s unsure why I’m suddenly talking to him after not speaking for the first three days of school. He probably thinks I’m a snob, but I’m really just afraid to look up from my books. I just survived the worst summer of my life, and I don’t remember how to talk to people. Plus, I just started high school—this guy has probably been here for more than his share of four years.

The PA system squawks, “Have a good day,” before shutting off. Angelo takes the quarters from me slowly.

“Thanks. Do I gotta pay you back?”

“Um, not if you…can’t.”

Angelo stares hard, keeping his eyes on me as he swaggers backward over to the pile of bagels on the counter. He picks one and then smiles at me. I quickly look back down at my books, thinking I might have made a mistake, being nice to one of the vocational-technical guys. Especially one of the older “vo-tech” guys. He pays and makes his way back to the half-empty table for six, sitting across from Jamie. His jacket is too small for him, and he wears a ratty Nirvana T-shirt that looks like it belonged to an older brother when Kurt Cobain was actually still alive.

“Good bagel,” Angelo says to me, while I pretend to be lost in my biology textbook. “What are you reading?”

“I’m studying for a biology test,” I say without looking up.

“You already got a test?” he asks. “We only been back a few days. You in those smart classes?”

I decide not to answer this time, but it doesn’t do any good.

“Didn’t you study at home? You look like a girl who woulda studied at home.”

“I did. But I don’t think it was enough.”

“Want me to quiz you? I could quiz you.”

“No, thanks.”

Angelo slides over so he’s sitting right next to me. He leans in. “I bet it would help,” he says. I shift back slightly. He’s got a ton of sharp black stubble, and he smells like cigarettes and Axe. He looks like he’s at least twenty.

“That’s okay.”

“You sure?” He reaches for my textbook. “I know a few things about biology.”

“Leave her alone,” says Jamie without looking up from his notebook. Angelo turns, raising his eyebrows. “She don’t wanna talk to you. She’s studying.”

“Fine, man. I’ll leave her alone.” Angelo gets up and moves toward another table. “See ya later,” he says to me. “What’s your name, anyway?”

I start to answer, but Jamie lifts his head from his drawing to stare at Angelo.

“What, man?” says Angelo. “What’s the deal? She your girlfriend or something?”

I can feel the blush start at my collarbones and work its hot way up to my cheeks. Jamie looks directly at me for the first time ever, as far as I know, and I have to look back down at my book. The words blur before my eyes as I try to focus on something, anything but what’s going on right next to me.

“I’m just tryin’ to be nice. She gave me some money.” Nobody says anything. Jamie studies the tip of his ground-down pencil. “All right. See ya in shop, Jame. Bye, Sweater,” Angelo says.

Jamie goes back to his work. I can barely breathe. Tracy, my best friend since the beginning of time, is suddenly in the seat across from me. I kind of can’t believe she’s here—upperclassmen get to go where they want in study hall, but the freshmen are supposed to stay glued to their seats.

“Did you study last night? It’s going to be so hard. Are you okay? You’re all red.” She brings a spoonful of yogurt to her mouth, studying my face in that weird, concerned way that I’ve seen a lot these past few months. Then she looks sideways at Jamie, at his construction boots and the ragged, dirty cuffs of his too-long jeans. “It’s too bad you got stuck at this table. We’re all studying together over there.” She points to a big twelve-seater full of freshmen who are probably talking about the keg party that they won’t get into at the nearby private school’s polo fields tonight. Why they even want to go is beyond me. But I’ve been trained by Tracy not to say that stuff out loud. It doesn’t do anything to increase my popularity, according to Miss Teen Vogue.

“I study better by myself.”

“Yeah, I know, you always say that. Maybe that’s why you always get A’s.”

“I don’t always get A’s.”

“Oh shut up. Have you thought about what we talked about?”

Tracy is referring to whether or not she should have sex with her boyfriend, Matt Hallis. We’ve been talking about this nonstop for the last few weeks, and it’s become my least favorite topic ever—for a lot of reasons. At first I thought she was bringing it up all the time to distract me and give me something to think about. But now I realize that she’s totally obsessed. It’s like she decided that the second she started high school, she had to lose her virginity or she’d never fit in. Or be cool. Or be…whatever.

Mr. Cella materializes out of thin air behind Tracy, who notices me looking past her and freezes.

He consults his seating chart. “Ms. Gerren, would you care to go back to your assigned seat?”

“We’re just talking about our biology test, Mr. Cella.”

“You had ample time to do that last night via text, or cell, or IM, I’m sure. Back to your seat.”

Tracy gets up. “You’re okay, right?” she asks. I nod. “Sorry you’re stuck over here,” she says again, before Mr. Cella escorts her back across the cafeteria without so much as a glance at me.

It took only two days for the teachers to stop looking at me like some sort of pathetic freak. Which is exactly what Peter said would happen, when I was complaining to him about starting high school barely three months after burying our dad.

What was left of him, anyway.

I try to concentrate on biology and ignore the flush in my cheeks that is taking its time receding.

I sneak a glance at Jamie.

Jamie Forta.

I know who Jamie is. I know because of Peter. Jamie and Peter were on the hockey team together when I was in seventh grade and Peter was a junior. Jamie was a freshman then. Dad and I used to come to the games to watch Peter, but after getting a good look at Jamie in the parking lot after a game once, I mostly watched Jamie. The next year, Jamie got thrown off the team during the first game of the season for high-sticking a West Union player named Anthony Parrina in the neck.

Although I hadn’t seen Jamie in a year, I recognized him the second I was assigned my seat at this table. Even without the hockey gear.

I can hear the scratch of Jamie’s pencil as he draws, grinding graphite down to wood. My gaze finds its way across the pages of my book, over the table and onto his notebook. It takes me a second to recognize the upside-down image as a house, a strange-looking house in the woods with a porch and a massive front door at the top of a wide staircase. I lean over the table to get a better view. And I realize he’s no longer drawing.

I’m afraid to lift my eyes from the page. When I do, Jamie is looking at me, his pencil in midair. Again, the flush rises from my chest, up over my neck and into my cheeks. Before I look away, I think I catch the slightest, tiniest, most minuscule glimpse of a smile in his eyes.

“That’s a really nice picture,” I whisper, unable to get any volume.

He looks at the pencil and shakes his head at its wrecked point, dropping it next to his notebook. He reaches into his pocket and draws out a dollar as he gets up from the table and starts toward the food. Apparently he’s learned to keep some of his money for himself, rather than give it all to Angelo.

“You should be studying,” he says with that hint of a smile in his eyes, and walks away. I feel the heat intensify at the sound of his voice, making the skin on my face tight with imaginary sunburn. He disappears in the rush of upperclassmen who have just come in from the cafeteria courtyard to get food before the bell rings.

I close my book and put it in my backpack, hoping to spy a piece of gum at the bottom somewhere to erase the dryness that goes along with humiliation. I rifle through my new makeup bag, which Tracy put together for me (“You can’t go to high school without a makeup bag”) and find an old piece of partly wrapped gum stuck to a busted eyeliner (apparently I got her hand-me-downs). I take the eyeliner out with the gum and separate the two, deciding the gum looks clean enough to chew. Weirdly, it tastes like lipstick. I rifle a little more, searching for something to help me find solid ground again. My fingers brush the eyeliner sharpener.

I take the sharpener out and look quickly over my shoulder for Jamie, who’s in line waiting to pay for a coffee. I grab his pencil and jam it into the sharpener, twisting and twisting and twisting, watching the yellow wood shreds peel off and fall to the table. I take his pencil out and look at its now-sharp point. The bits of eyeliner stuck in the sharpener have left a few electric-blue stains, but the point is truly perfect. I quickly put it back where I found it, looking again just in time to see Jamie turning away from the cashier to start back to the table. The bell rings. I grab my bag and run.

blunderbuss (noun): clumsy person who makes mistakes

(see also: me)

2

“MY GRANDMA SAYS it’s better not to be beautiful, because then you have nothing to lose. And you know that the guy who married you married you for the right reasons,” Stephanie says.

“Or you just know that he’s ugly, too,” Tracy responds.

“I assume the level of conversation in the room means that everyone has finished his or her exam?” Mr. Roma says from his position by the blackboard. “Ah, Robert still has his paper, girls, so no more talking until he’s done. You have ten minutes, Robert. Is Robert the only one?”

No one else says anything. Robert looks up, catches my eye and winks. I look away. Tracy and Stephanie laugh.

“Enough, girls. Let the man finish.”

“Genius takes time, Mr. Roma,” he says.

“You have nine minutes, Robert.”

I suddenly remember the answer that I needed for the fifth question, and I become convinced that I failed. But I’m always convinced I failed, and it has yet to happen. The class has been sitting in silence for two minutes when a note lands on my desk. I can tell by the way it’s folded that it’s from Tracy.

Students are not allowed to bring cell phones or smart phones or anything like that into classrooms. This drives a lot of people crazy, including Tracy, who is addicted to texting and IM-ing. But I couldn’t care less about the ban because a) I’d rather get a nicely folded note with words that have all their letters than a stupid text any day of the week; b) I hate people who cheat, and cell phones make it really easy to do that; and c) I don’t have a cell phone. Tracy thinks it’s really lame that I’m so far behind the curve.

I was going to get one before school started this year, but other things came up. Like death.

I try to open the note without making any noise, but Mr. Roma hears me. He raises his finger to his lips to silently shush me, but he doesn’t get up to claim the note and read it out loud, which is what he did yesterday to Stephanie. Instead, he gives me a frowny smile. Apparently, Mr. Roma still thinks I’m a pathetic freak in need of sympathy even if Mr. Cella does not. I look down at the note.

What did you do to that guy at your table in study hall? He asked me where your last class was.

My heart stops. Where’s your last class? can be code for several things: Where do you want to meet so we can walk to practice together? or Where should I meet you so I can sell you those drugs? or Where can I find you so I can beat you up? Since Jamie and I aren’t on a team together—I’m not on one yet and, in fact, I don’t think he’s allowed on any team anymore—and I have no interest in buying drugs from him—not that I know he actually sells drugs—that leaves one option. But that doesn’t make any sense, either. All I did was sharpen his pencil.

I turn to Tracy. Did you tell him? I mouth. What? she mouths back. I point to the note and mouth my question again, more slowly this time. She nods seriously and then shrugs at my panicked expression.

“What was I supposed to do? He creeped me out,” she whispers.

“Was he mad?”

“Kinda—”

“Tracy Gerren! Enough! Go sit by the window.”

Tracy rolls her eyes, gathers her things and heads toward the back of the room. “Thanks a lot,” she mutters in my direction. Robert places his paper down on Mr. Roma’s desk with a flourish.

“I am officially finished, ladies and gentlemen. You are free to talk.”

“Sit, Robert. And be quiet. In fact, everyone stay quiet until the bell rings. I’ve decided that I like this class best when it’s silent.”

Three minutes until the bell. I have no idea what’s going to be waiting for me out there. I feel sick to my stomach, which gives me a great idea. I slide out of my seat and head toward—Mr. Roma’s desk. Robert tries to grab my hand as I walk by. He smells like cigarettes. I ignore him. I’ve been ignoring him since sixth grade.

“Mr. Roma, I know the bell’s about to ring, but I need a lav pass.”

Mr. Roma hands me the pink pass after writing the time on it without so much as a raised eyebrow.

I guess there are some benefits to freak status after all.

* * *

I’m in the bathroom by the gym—the bathroom farthest from the school’s main front doors—when the final bell rings. Two girls are smoking in a stall at the end. It’s hard to breathe. I wait until they leave, and then I wait a few more minutes. It’s still hard to breathe. I wonder if I’m having one of those panic attacks my mom is convinced I get now. To distract myself I read the graffiti on the wall, which says Suck it, among other things, in hot-pink nail polish.

Such originality here at Union High. Such excellent use of vocabulary.

When I can breathe again, I leave.

The halls are basically empty. I go to my locker. I get my books. I grab my French horn out of the orchestra room so I can practice later, and I leave by the front doors because there’s no other way to leave at the end of the day; they funnel us out through the front to keep an eye on us. I’m waiting at the crosswalk when I see him on the other side of the street. He isn’t holding any books. The crosswalk light goes from the red hand to the silver guy, and I’m afraid to move, but I do anyway. I get closer and closer and closer, but he doesn’t say a word. In fact, I just walk past him as if I don’t see him, and a few seconds pass. My legs are still moving when he says, “Rose.”

I’ve never, ever heard anyone say my name like that in my entire life. I didn’t even know that was my name until he said it like that.

“Yeah?”

He holds out his pencil. “What did you do?”

“I…just…it was…” I falter.

“What’s this stuff on it?”

“Oh, um, sorry—it’s eyeliner.”

He takes a few steps closer and looks carefully at my eyes. “You don’t wear that stuff.”

The flush starts. It’s slow-moving, but it’s going to be a huge burn—it stretches from shoulder to shoulder and it’s going to spread above my collar in about three seconds. I notice that his eyes are hazel with gold specks and then I can’t look anymore.

“Sometimes I do.”

“Like when?”

“If I’m going out with my boyfriend or something.”

“Oh, yeah? Who’s that?” I have nothing to say. “You’re a freshman, right?” he asks.

“I’m fourteen,” comes out of my mouth. And then, like we’re playing in the sandbox, I ask, “How old are you?”

That glint of a smile shows up briefly again but disappears before I’m sure it was real.

“Come on, I’ll take you home.”

“You don’t know where I live.”

“Yeah, I do,” he says. I stare at him dumbly. “How’s your brother?” he asks.

The question surprises me. Even though Peter and Jamie played hockey together, I assumed they never talked off the ice. “Okay, I guess. He’s at Tufts. Are you guys friends?”

“I drove him home when Bobby Passeo skated over his fingers,” he says, not answering my question.

“I saw you, you know. Play hockey. When you were still on the team.” I become very interested in my shoes, realizing that I sound like exactly what I am—a babbling fourteen-year-old. He looks at me, waiting. When I don’t say anything else, he says, “So do you want a ride?”

“I can’t get in the car with you,” is my response. I’m no longer a babbling fourteen-year-old. I’m now ten. Or maybe eight.

He can’t help himself this time. He breaks into a huge smile. My heart skitters for a second.

“What do you think is gonna happen?” he asks, taking my French horn from me. I feel like an idiot. “Come on, freshman. I’ll drive you home.”

* * *

His car is old, and rusty and a strange, flat green. But the inside is clean, and black and smells like cold rain. I’m sitting far away from him, embarrassed that I was embarrassed when he opened my door for me in the school parking lot. The radio is playing Kanye, but Jamie changes it to a classic rock station. Pearl Jam. When I was in kindergarten Peter used to play Pearl Jam for me and make me recite the band members and the instruments they played. Eddie Vedder, singer. Mike McCready, guitarist. I can’t remember the bass player’s name. Jeff Something. Peter got me addicted to good music and real musicians at a very young age, which, to be honest, hasn’t done me any favors socially.

I can’t believe I’m in a car with Jamie Forta.

“Are you cold?”

“No.”

“You look cold.”

“Not really.” He’s right. I am cold. But not because of the weather—September in Connecticut still feels like summer. I always spend the first three weeks of school sweating through my new fall clothes because I couldn’t stand to wear my summer clothes for another minute. I’m probably the only person in my entire school of 2,500 who wore a sweater today, willing the weather to be cooler.

Well, I sort of got my wish. I’m cold now. Fear does that to me.

I look at him and he’s looking at the road. He stops at a yellow light. I’m surprised. I guess I expected someone like Jamie Forta to just blow through a yellow light without even thinking about it. He’s still looking at the road. Nobody seems to have anything to say. I’m embarrassed again. I’ve been embarrassed a lot today. Mostly because of him.

“Where’s your notebook?” I ask.

“Locker.”

“Don’t you have any homework?”

He looks at me like I’ve said something funny. The light turns green, and he turns left. I realize that he actually does know where I live.

Silence. Silence, silence, silence.

“I liked the house you were drawing.”

“Yeah?”

“You’re a good artist.”

He takes another left. We drive by Tracy’s brown house with the red trim, where I will spend the first part of tonight lying on her bedroom floor, continuing our endless conversation about sex. After she decides she’ll sleep with Matt “soon,” since they’ve been going out since the beginning of eighth grade, she’ll move on to whether I should go out with Robert or not. The answer is usually no, but sometimes she says he’d probably treat me really well. Then I remind her that I hate cigarettes. She suggests I convince him to quit. I reply that people only quit if they want to. She says he’d definitely quit for me.

Robert, according to Tracy, has been in love with me since the sixth grade. I tell her that that’s impossible, because how did we know what love was in elementary school? She tells me that just because we couldn’t identify love when we were eleven, that doesn’t mean we weren’t capable of feeling it. Maybe she’s right. I have no idea. But I do know that I’ve never been in love with Robert. And I have no intention of going out with him just because he’s “in love” with me. Which he’s probably not. Because why would he be? I’m not pretty, and I like to use words with a lot of letters in them—two big turn-offs for guys.

My dad always got mad at me when I said things like that in front of him. “First of all, Rose, you are pretty,” he’d tell me. “And second of all, never look twice at a man who doesn’t appreciate a smart woman. Never.” He was always full of good advice that was impossible to follow.

For a while after he died, I saw him almost every night. I’d dream that I was in an empty movie theater, sitting by myself in a sea of red seats, watching him on a huge screen like he was a star. He was twenty-feet tall, his brown hair sticking out every which way, his blue eyes burning like neon when he looked at me, pinning me to my seat with his stare like he was waiting for me to do something, to fix the situation, to get him out of the action flick or Western he was stuck in and back into the real world. Sometimes I’d see things that really happened, like when I was ten and he took Tracy and me to a Springsteen concert, and I was embarrassed by his weird dancing but also kind of proud that he was so into the concert. Or I’d see us looking at his twenty-volume Oxford English Dictionary, studying the history and derivation of some crazy word that had come out of his mouth, like erinaceous. One night at dinner he’d said, “Pete, you seem to have inherited the erinaceous hair Zarelli men are often cursed with—consider cutting back on the product.” Later, when Peter found out that Dad had basically said his hair looked like a hedgehog, he didn’t talk to my dad for almost a week.

I bet Peter regrets that now.

Other times when I was having the movie theater dream, I’d see things that I didn’t experience. Like when the convoy Dad was riding in blew up, killing everyone within fifty feet.

Dad never should have been in Iraq. He wasn’t a soldier. He only went because when the economy tanked, he lost his job as an aircraft engineer, and the military recruited him as a contractor, offering him a big salary for a short tour of duty. Mom was freaking out about money, and they had eight years of college tuition to look forward to, thanks to Peter and me, so he went.

Peter and I never said it to them, but we both thought they had gone completely insane. And we were right. Dad got to Iraq in February and was dead by June, when the truck he was in hit a homemade roadside bomb. He died instantly they told us, to make us feel better. But it didn’t make us feel better—well, not me, anyway. It just got my imagination going, wondering exactly what that meant.

Dreaming about exactly what that meant.

The dreams about the convoy didn’t have sound. I never heard the explosion, or the dying, or anything. And there was no blood. I just saw Dad, sailing through the air with his eyes wide open, twisting and turning, and then landing on his back on the ground and cracking into sections like a piece of glass that had been dropped from just a few inches up, shattering but still keeping its shape.

The dreams stopped after a while, and I was relieved—until I started to miss them. Now that I don’t see my dad at all anymore, I worry that I’m forgetting everything about him.

Jamie takes a right and then a quick left, and ten seconds later we’re at my house.

“This is it, right?”

“Yes.” Silence. “So, when did Bobby Passeo skate over Peter’s fingers?”

“I don’t know. Two years ago, I guess.”

I can’t believe he still remembers where we live.

“Wait, you had your license two years ago?”

He shakes his head and leans back against his door, looking at me with those perfectly hazel eyes that make me nervous.

“You okay?” he asks, a cloud passing across his face. His question and dark expression catch me off guard, as I’m still thinking about him driving without a license. A thousand people have pissed me off by asking that question in the past few months. But I don’t seem to mind it when it comes from Jamie. “I’m sorry. About your dad,” he says.

I nod, but that’s all I can do. I’m not going to risk crying in front of Jamie. I can’t really predict when I’m going to cry, but when I do, it involves a lot of snot. “Well, thanks for the ride,” I say, reaching for the door handle.

“Rose,” he says. “You know my name, don’t you?”

His name? He thinks I don’t know his name? The idea that I’m so in my own universe that I haven’t heard Angelo call him “Jamie” and “Jame” every two minutes in study hall—that I wouldn’t know his name, that I wouldn’t know who he was after watching him play hockey all those times—is crazy. But should I admit that I know his name? If I know his name, will he think I…like him?

“Um…” I say.

His expression quickly goes blank. He turns back toward the steering wheel and puts the car from Park into Drive as if he were planning to gun it the second my feet hit the pavement.

“Jamie,” he tells me as he stares straight ahead, waiting for me to leave.

I’m an idiot. But if I now say, Of course I know your name, I’ve always known your name, he won’t believe me. “Thanks again for the ride,” is all I can manage.

I get out as fast as I can, and he takes off, leaving me standing in the street, feeling like a complete loser for pretending not to know the name of someone who just went out of his way to be nice to me, who seemed genuinely sorry about what happened.

Nice going, Rose. Way to make friends. Keep up the good work.

belligerent (adjective): inclined to hostility or war

(once again, see also: me)

3

A FEW HOURS later, I’m in my usual Friday-night spot, sprawled on Tracy’s bright orange shag carpet that we got at Target, waiting for Robert and Matt to show up so we can go to Cavallo’s for pizza. I am very carefully not talking about Jamie, although I feel like I’m going to explode if I don’t. He was being so nice, and I messed everything up. I want to ask Tracy if she thinks he actually likes me or just feels sorry for me, but I can tell she doesn’t like him by the way she looked at him in study hall today. It’s easier just to say nothing.

Tonight, predictably, Tracy and I are covering three topics during our session in her room: her virginity, Robert and her cheerleading tryout. To be honest, I can’t believe Tracy is going out for cheerleading at Union High. First of all, our cheerleading team is not one of those amazing, superathletic competitive teams—there are no backflips off crazy-high human pyramids at halftime. The most acrobatic thing that goes on here is a synchronized hair flip. And being on the cheerleading team at our school isn’t like being a cheerleader at the private school in Union— Here, it doesn’t mean you’re at the top of the food chain. Yes, some of the cheerleaders are beautiful and go out with hot jocks, but some are average-looking girls who just happen to know how to dance. Some are smart, some not. Some have money, some don’t. In other words, not all of them are popular. And to top it all off, Union High cheerleaders have kind of a slutty reputation on the whole. At least, that’s what I heard Peter say once.

So even if Tracy does make the team—and I kind of don’t think she will—she’s not automatically granted access to the top tier of Union High popularity. But I’m not about to tell her that. She’ll just accuse me of being a snob. And in some ways she’s right—after all, I think Union High’s brand of cheerleading is a waste of time and teenage girls.

But I’d still rather talk about cheerleading than virginity.

“I don’t think fifteen is too young to lose it, do you?”

I hate this part of the conversation. “I don’t know,” I mumble.

“You always say that.”

Well, what do I know? I can’t really imagine letting a guy see me naked, never mind letting him do that to me while I’m naked. So I don’t really know what to think. I don’t want to think about it at all, most of the time. Which makes me think that fourteen is probably too young. And is fifteen really that different from fourteen?

“Maybe I should go on the pill,” she says.

I nearly fall through the floor. I suddenly feel like she’s thirty and I’m still in nursery school.

“Tracy, you can’t go on the pill.”

“Why not?”

“You know why not. You have to use condoms. It’s too dangerous not to,” I say.

“You’re so paranoid about sex, Rosie. You always have been. You better relax.”

She’s right about this, too. I am paranoid about sex. Maybe it’s because I have an older brother who decided to tell me all about the dangers of sex the night before he left for college. I’m not sure why Peter was so worked up about the whole thing, but if I had to guess, I’d say it was because he felt he had to fill the parental void. Since Dad died, Mom hasn’t exactly been “available” or “present” or whatever you say, which is kind of ironic, since she’s a shrink. Who specializes in adolescent psychology. When she does talk to me these days, she uses her therapy voice, which makes me go deaf almost instantly.

Thanks to her job, we have enough books on teenagers in the house that I could find the answer to pretty much any question I might have, if I felt like looking. Which I don’t. Maybe that’s why Peter called me into his room to talk about sex while he was packing.

He was listening to Coldplay and I assumed he just wanted to dissect the album and explain why he thought Chris Martin was such a hack. But, no. “Never, ever let some guy talk you into sex without a condom,” Peter had said without any sort of warning. I froze in the middle of his room. “He’ll try to tell you that he can’t feel anything, and that it will be better for both of you if you don’t use one, but he’s just being a selfish asshole. You can get all sorts of diseases from sex. Girls can even get cervical cancer from sex. So don’t listen to some loser who claims he can’t get it up with a condom on. That doesn’t happen to guys until they’re, like, old. And don’t go on the pill for anyone. But you’ll learn all about this stuff in Ms. Maso’s class—she’s the bomb.”

Peter scared the crap out of me, even though I didn’t understand half of what he said. Or maybe that’s why he scared me so much. I barely know what a cervix is. For someone with the aforementioned abnormally large vocabulary, I can be intentionally dumb sometimes.

Tracy hops off the bed and goes to her full-length mirror to check out how her butt looks in her new Rock & Republic jeans—again. You’d think we were going to a fashion show, not out for pizza. I suddenly notice that all of her boy-band posters are gone. Her walls are blank. I can’t believe it, given the amount of time we spent decorating and redecorating our walls last year. I open my mouth to ask about the posters when she says, “Matt wants me to go on the pill.”

Peter’s words about guys who don’t want to use condoms replay in my mind, and I instantly want to punch Matt. “That’s insane, Tracy. Why?”

“How about not getting pregnant? The pill protects better than condoms, you know.”

“Not against STDs.”

“Rosie, Matt and I are both virgins. He’s not going to give me anything.”

Apparently I’m not the only one who is intentionally dumb sometimes.

The words form in my mind, and I know I shouldn’t say them out loud. But I kind of can’t help myself these days. If I want to say something, I say it, for better or worse.

“Do you really know he’s never done it before, Tracy?”

She turns from the mirror and looks at me suspiciously.

“Do you know something I don’t know?”

“No!”

“Because if you do, Rosie, you’d better tell me now—”

“I don’t! But I’m just saying, Trace, how do you know Matt is a virgin?”

“Because he told me so. And I trust him,” she says slowly, as if speaking to someone who doesn’t understand English.

I can already tell it’s going to take her days to forgive me for this one. “Okay, okay, sorry.”

She stares at me for another second and then turns back to the mirror, brushing her straightened brown hair so hard I’m amazed it stays in her head.

“And he’s not going to cheat on me, either.”

At least she’s thought about that possibility. That’s a positive sign, even if she is in denial.

“I’m just saying that things happen. And it’s never a bad idea to protect yourself.” I impress myself for a minute—I actually sound like I know what I’m talking about, which is ironic because Tracy is way more experienced than me, as she often likes to point out. Even if she did get all her “experience” this summer. Which was basically last month.

The doorbell rings downstairs, and Tracy’s mom calls up to let us know that the boys are here. Tracy finishes putting on more eyeliner and leaves the room without another word to me. I grab the bag she lent me when she insisted I’d look like an idiot if I brought my backpack, and I follow her. It’s definitely going to be one of those nights.

* * *

Cavallo’s is packed. Matt stops to talk to some of his friends from the swim team—they’re seniors and they’re huge. If I didn’t know any better, I’d think they were on steroids. But as I’ve noticed these last four days, there is a pretty big physical difference between a fourteen-year-old and an eighteen-year-old. It almost makes competitive sports in high school seem like a joke. The senior who held the cross-country team’s informational meeting the other day had legs that were at least twice the length of mine.

My dad would have told me not to worry. “It’s not the length of the leg, it’s the length of the stride,” he used to say. He was always telling me to take bigger steps when we ran together. Dad made the mistake of taking me to see a half marathon when I was nine, and right then and there I decided that I was going to run the race the next September. He said he’d train me, which basically meant he spent the summer being really late for work and running twice as much as I ever did. We’d go on runs early in the morning, before it got too hot, and of course it took him a while to get me out of bed, so we never started as early as he wanted to. And then, when we were running, I’d get slower and slower as the longer runs went on, and he’d have to double back for me. I don’t think it was much fun for him, but he was pretty proud of me when I finally ran the race at the end of all that. It took me forever, but I finished. I was the youngest girl running that year.

I haven’t run since he died. Peter pulled me aside this summer after Mom had asked me for the millionth time when I was going to go for a run, and he told me that I never had to run again if I didn’t want to. But I do. I will… I think.

Robert and I grab a booth, but Tracy hovers near Matt until she realizes that he’s not going to introduce her to the swim thugs. Then she comes over, trying to look fine but mostly looking mad. And sad, too.

“So, Rose,” she says. I know I’m in trouble when she calls me Rose and not Rosie. Well, that, and also the fact that until now she hadn’t spoken to me since we left her room. “I saw you with that guy today in the parking lot after school.”

Robert looks at me. The waitress with the crazy beehive hairdo arrives to take our order. She’s famous for demanding that kids pay before she puts their orders in—including tip. We must look trustworthy, because after we order our pizza and sodas, she just leaves.

“What guy?” Robert asks.

I’m staring at Tracy. So this is how she’s going to get revenge for me saying that Matt might not be her knight in shining armor. I realize that she has had this information about me since the afternoon and she’s been saving it. Clearly Tracy has been studying Gossip Girl, absorbing lessons in how to treat your friends like crap.

“Jamie Forta. You got in a car with Jamie Forta,” she says. How interesting that, when it’s convenient for her, she knows his actual name. Her eyes are glued to Robert’s face, searching for a reaction. He must look appropriately shocked or hurt because she appears to be very satisfied. I decide to focus on the blackboard menu above the counter, even though we’ve already ordered and I know the menu by heart.

“What the hell were you doing with Jamie Forta?” Matt asks as he finally sits down at our booth. “That guy’s such a loser. I hear he’s been trying to graduate from high school for, like, three years or something.”

I used to like Matt, way back in eighth grade. But something changed over the summer when he started preseason training with the swim team. He partied with them and now he thinks he’s such a big deal, it’s annoying. I started hating him the second I realized he was pressuring Tracy to have sex. But tonight, right now, I hate him for an entirely new reason.

“He’s a junior, Matt. And you don’t know anything about him.”

“There’s definitely something wrong with that guy,” Matt says. “He’s a moron.”

“Do you know him, Rose?” Robert asks.

The waitress drops off four sodas. Matt reaches for his wallet, but she still doesn’t ask for money. He looks puzzled. I sip my root beer and try to buy myself some time.

“Rosie?” Robert says.

“Yes,” I finally say, hiccupping because of the carbonation. “He was on the hockey team with Peter.”

“Peter knew him?” Tracy asks, blushing a little bit. Matt gives Tracy a sharp look. She’s had a crush on Peter since the day she became my best friend. Coincidence? Doubtful. But maybe that’s just my cynical side coming out.

“Jamie drove Peter home once, when Bobby Passeo skated over his hand.” I know that no one here could possibly know who Bobby Passeo is, but I figure he could work as a diversion from the current topic.

“Jamie’s weird,” Tracy says, ignoring Matt. “What did he want with you?”

So much for a diversion. “Nothing. He has a right to talk to me, Trace. He even has a right to offer me a ride home.”

“He’s a junior,” Robert says, sounding alarmed.

“So what? We’re not supposed to talk to people who aren’t in our class?”

“He must have wanted something from you,” Tracy says again.

“Nope.” I am determined not to give her anything. Two can play at this game.

“Fine. Don’t tell me if you don’t want to,” she snaps.

“There’s nothing to tell,” I snap back.

The guys are now watching our conversation like it’s a tennis match. Matt looks amused, Robert looks confused. Tracy is staring at me, hard, and then she plays her trump card. I don’t actually know if she knows it’s a trump card, but it is.

“He goes out with Regina Deladdo, who’s friends with Michelle Vicenza. They’re both on the squad,” Tracy says, using her favorite, extremely annoying nickname for the cheerleading team. “Michelle’s the captain. Regina’s her lieutenant.”

You’d have to live under a rock three towns over to not know who Michelle Vicenza is. She’s Union High’s prom and homecoming queen. It’s been that way for four years. She might have been born with those titles. Every girl in Union secretly—or not so secretly—wants to be Michelle. She goes out with Frankie Cavallo, who graduated two years ago and now runs Cavallo’s, which is his family’s place. Peter introduced me to Michelle last year at his graduation party—I thought she was the prettiest girl I’d ever seen.

But I have no idea who Regina Deladdo is.

Or why Tracy suddenly seems to know everything about Jamie Forta when she was calling him “that guy” just two minutes ago.

The waitress brings our pizza over and takes a moment to rearrange everything on the table so it fits. I’m glad, because I need a second to get over the fact that Tracy knows more about Jamie than I do. The way she’s doling out information tonight makes me want to kill her. How does Tracy already know that Regina Deladdo is dating Jamie? She must have been studying up from the moment we started school on Tuesday.

Jamie goes out with a cheerleader? My brain hurts.

I try very, very hard not to let anything show on my face.

“Wow,” Robert says. “I know who she is. She seems a little…” He takes a sip of his drink as he searches for the right word.

“Insane?” Matt says, shaking his head as he takes a bite of pizza. “Imagine screwing that harpy,” he adds. Robert nearly spits out his soda. Tracy stares at the table.

Matt, a virgin? Uh-huh. Sure.

“They’re perfect for each other,” he continues. “They’re both idiots.”

For the second time in one night, I know I’m about to say something I shouldn’t, but I can’t stop the words from coming out.

“Just because you got drunk with a few seniors over the summer, does that make you better than everyone now?”

Matt slowly puts his pizza down. “What’s your problem?”

“My problem, Matt, is that you’re being a jerk! And you’ve been a jerk for, like, two months now.”

“Anything else?” he asks.

I’m on a roll, and when this new me is on a roll, nothing can stop me. It feels so good to say exactly what I’m thinking.

“Yeah, actually, there is something else. Stop treating my best friend like dirt. Introduce her to your friends when you’re talking to them and she’s standing right next to you. And you might want to—”

“Stop!” yells Tracy, kicking me hard under the table. Matt looks from me to Tracy and back, and then gets up and goes to sit with his swim thugs. Tears pool in Tracy’s eyes.

“You don’t get to just say whatever you want, no matter what happened to you this summer,” she hisses as she grabs her bag and marches out the door. Matt watches her leave but doesn’t go after her. I’m suddenly really, really embarrassed.

“Nice work,” Robert says.

I’m trying to backtrack in my head and figure out what set me off and made me act like a lunatic. The waitress comes over.

“You’re Peter’s little sister, right?” she asks. I nod. “Sorry about your dad, hon. Soda’s on the house.” She slaps the bill down on the table and walks away. If I were in a better mood, I might laugh at how one dead dad equals four free sodas here at Cavallo’s.

“Rosie, I think you should go after her,” Robert suggests, reaching for the bill, an unlit cigarette already in his mouth. “And you should probably say you’re sorry.”

He’s right. I should. And I do.

lachrymose (adjective): sad; tearful

(see also: being a crybaby)

4

JAMIE HASN'T BEEN in study hall since Friday. It’s now Wednesday. Since Monday, I’ve spent the period pretending to read A Separate Peace while trying to come up with something to say to him, something that will right the wrong I committed on Friday by stupidly pretending I didn’t know his name. As lame as it sounds, I’m not used to having to come up with answers to these kinds of dilemmas by myself. I usually talk to Tracy, but I can’t do that this time.

I ran after her on Friday night, catching her just a few blocks from her house. I told her I was sorry for what I did but that I meant what I said—Matt was acting like a jerk. She didn’t agree, but she didn’t disagree, either, and we’ve had a truce since then. She hasn’t asked me any more questions about Jamie, and I’m not about to bring him up. She’ll want answers, and I don’t have any.

I look across the cafeteria and see her sitting next to Matt, looking up at him adoringly while he barely acknowledges her existence, as usual. She waves at me, and if I had to guess, I’d say that she kind of likes the sight of me sitting by myself. Freshmen at the end of the alphabet always get screwed when it comes to assigned seats in study hall. You get stuck anywhere there are leftover seats, which is at the juniors’ and seniors’ tables. They get to pick their tables first, which is considered a privilege, and then tables are assigned to the sophomores and then the freshmen. The freshmen at the top of the alphabet end up at the few remaining empty tables together, but the freshmen at the end of the alphabet—like someone named, say, Rose Zarelli—get assigned wherever there are leftover seats. Jamie and Angelo and I have a whole table for six to ourselves.

I wave back at Tracy, and she frowns, pointing behind me. I turn.

“Hey, Sweater. I got those quarters for ya.”

Angelo shaved this morning, and it didn’t work out so well. He has little dots of dried blood all over his face, and his stubble is already growing back.

“Oh. Um, that’s okay. You don’t have to pay me back.”

“Really?”

“Keep them. I don’t need them.”

“I don’t need them, either, Sweater.”

“No, I mean, I have money today.”

“So do I. Whaddya think, I’m poor or something? I got paid yesterday.”

“I mean, my mom never kicks me out of the house without letting me finish breakfast, and she always gives me lunch money,” I say, instantly cringing at the fact that I just said lunch money—couldn’t I have just said money, without the lunch qualifier? No, of course not. “Um, so you should keep it in case your mom does that again.”

He says nothing.

“I’m…I didn’t mean… Sorry.”

“How’d you know that?”

“Well, um, I mean, that was Friday.”

“I told you about that?”

“Not exactly.”

“I was talkin’ to Jamie,” he says suspiciously.

“Yeah, but I sit here, too.”

“I guess you do, dontcha.” He leans over me, and I notice that he opted not to wear Axe today. “You’re listenin’ even when you pretend you’re not, ain’t ya?” He takes his jacket off and hurls it on the table, revealing a Metallica T-shirt as ratty as his Nirvana shirt, and a lighter falls out of the pocket. He grins at me. “Want anything? I’m buying today.”

“No, thanks.”

“You sure? I’m gettin’ a coffee for Jame.”

My stomach drops like I’m on the first plunge of a roller-coaster ride. “He’s here today?”

“Yeah. Even vo-tech guys can only cut so many times before someone catches on.”

“Where is he?” I say too quickly. Angelo, who was walking backward toward the food line, now stops.

“Outside,” he says, looking at me very carefully. “Why? You miss him?”

I’m blushing, but I’m too busy backtracking to pay much attention.

“I just didn’t think he was here, that’s all.”

“You been looking for him.”

“No, I haven’t—”

“What’s the deal with you two? You doin’ it?” He sits down and whacks me too hard on the shoulder. “Come on, you can tell me. I know everything about him. He won’t care.”

“Why are you asking me if you know everything about him?” I say, sort of proud of myself for a second.

He’s a little puzzled until his brain catches up with his ears. “All right, I don’t know everything about him. But he tells me about all the girls he bangs, so you can tell me if you’re doin’ it.”

I’m unprepared for the jealousy. It dries out my mouth. A slow smile crosses his face.

“Look at you. You’re all pissed off that he’s with other girls.”

“I’m not pissed off. I don’t care. He can do whatever the fuck he wants.” I figure if I throw in the F-word, it’ll sound better, but of course, since I’m not really practiced at throwing in the F-word, it just sounds stupid.

“You two are doin’ it! Did he ‘pop your cherry’?” he asks with air quotes. “How old are you, anyway?”

I amaze myself by starting to cry. It comes out of nowhere. Tears pool in my eyes, and I know that if I move my eyeballs at all, or if I blink, those tears will spill on the table. So I look down, trying to be still, concentrating on keeping my last little shred of pride intact.

He whacks me again, a little more gently this time. “Sweater, gimme the details,” he says, conspiratorially. “Jamie’s gonna tell me anyway.”

“Tell you what?”

I’ve wanted to see Jamie for five long days now so that I could apologize and set the record straight about the name thing. And any other time, I’d be thanking god that he showed up to get Angelo away from me and off the topic of my “cherry.” But right now, I’d rather be taking a test I didn’t study for than have to see his face. I make the fatal mistake of turning my head slightly, and a fat tear splats on the table. I glance up. Then two more fall. Angelo, to his credit, looks a little mortified by the waterworks.

“I’m just trying to get Sweater here to tell me what’s goin’ on, that’s all. I didn’t do anything. I swear, Jame. I didn’t touch her or nothin’. Well, I hit her on the shoulder but not hard. I didn’t hit you hard, did I?”

I can’t answer, even though I feel bad that he feels bad. We all just sit there. Teenage boys don’t know what to do with a crying girl. Even the crying girl doesn’t know what to do with the crying girl.

“I’m gonna go get that coffee now, Jame.”

“Yeah, you do that.”

“I hate when I make girls cry. Fuck,” he says. He wanders off, looking over his shoulder, completely bewildered.

The cafeteria seems to go silent as Jamie sits down across from me. “What did he say?”

I’m memorizing the initials scratched into the top of the table. JH, JG, SW, SR, TR. My throat is so constricted from trying not to cry that it aches like the worst strep ever, and I’m afraid of what my voice will sound like if I talk. Mostly, I just want to keep my nose from running in front of him.

“Rose.” I love the way he says my name. It starts somewhere in his chest and it has a Z instead of an S. My eyes rise to meet his, and he looks so concerned that I almost start to cry again. “What did he say to you? Was it about your dad?”

It would be a lot easier to explain my reaction if I were crying about my dad. And maybe I am for all I know. My mom warned me in her annoying therapy voice that I might cry about him without even realizing that that’s why I was crying. Maybe that’s what’s happening now.

Jamie reaches out his hand, but it stops just short of mine on the table and rests there. He’s got ink on his thumb, but other than that, his hands are immaculate. Beautiful. Strong. I can see the blood in his thick veins. I want to run my finger along them. I bet the insides of his forearms look the same way. I imagine pushing up his sleeve to look.

I shake my head and wipe my face. “Angelo was just teasing me,” I say.

“About what?”

I take a deep breath. “You.”

“Me?”

“He wanted to know if you and I were having sex. And whether I was a virgin.” The word sets my blushing mechanism off at full force. I can’t believe I put the issue of my virginity on the table, but I want him to hear my version of the story— Who knows what the heck Angelo will tell him.

Jamie smiles a little. “He just can’t get any, so he always wants to hear what everybody else is doing.” He pulls his hand back. “Not that we’re doing anything.”

Another tear, hopefully the last one, begins its descent, and I wipe it away before it hits my cheekbone.

“That’s why you’re upset?” he asks.

I nod my head. And it could end right there. I could just call it a day. But my mouth won’t stop running. “He said you tell him everything, about all the girls you…” My throat closes up again, and I can’t finish the sentence, never mind ask him about Regina.

“‘All the girls’? What girls? Do you see any girls around here?”

“He said that you…that you’re with a lot of girls.”

“Forget him.”

“You’re not with a lot of girls?”

He looks at me with mild curiosity and he’s about to say something when it occurs to me that I’ve been waiting for five days for the opportunity to apologize to him. “I’m sorry, Jamie,” I blurt out.

“For what?”

“For the other day. In your car. I knew your name. I’ve known your name since I was in seventh grade. But I was too—”

Angelo puts Jamie’s coffee and a doughnut between us.

“The doughnut’s for you, Sweater,” he says, and he sits at the end of the table, purposely looking the other way. Jamie takes his coffee and stands.

“I’m goin’ outside.” I’m not sure who he’s talking to. “Angelo,” he says sharply. Angelo gets up fast, without saying a word or looking at either of us.

I watch them walk toward the courtyard door. Angelo pushes the door hard, a cigarette already in his mouth, and disappears. Jamie turns, and I think, but I’m not sure, that he winks at me. He’s gone before I can manage a smile. I’m so exhausted and confused that I can’t even eat my doughnut.

prevaricate (verb): to stray from the truth

(see also: to lie like a jerk)

5

“HEY, WAIT UP!” Robert yells as I’m walking to school. It’s the middle of October. It’s cold, I’m miserable and Robert is the last person I want to talk to. I crank up the volume on my iPod and pick up my pace as some old-school Public Enemy blares in my ears—Peter would be proud.

If anyone ever tried to figure out who I am based purely on my iPod, they’d never be able to do it. Public Enemy is followed by the Pussycat Dolls and preceded by Patty Griffin. I love my Florence + The Machine as much as my Rihanna, my White Stripes as much as my Black Keys. I pride myself on my eclectic musical taste, which has everything to do with Peter and probably not that much to do with me.

“Hey!” Robert yells again. I look over my shoulder. He’s trying to catch up with me. I start running, my backpack smashing against my shoulder blades.

“Rosie! Come on!”

Nothing is the way it was supposed to be this year, and it’s really pissing me off. Tracy was one of two freshmen who made the cheerleading team, and she has totally abandoned our Friday nights at Cavallo’s to hang out with her “squad” friends. Jamie was pulled out of study hall and put in remedial English, and now I only see him in the halls between classes, if at all. Angelo drives me crazy in the mornings, talking my ear off. And yesterday, I went out for the cross-country team.

The tryout was a disaster, a runner’s nightmare come to life. My legs wouldn’t work. My timing was off—I had to tell my brain to tell my legs to move. And when they did move, I couldn’t lift them high enough to take a real step, like I was wearing metal running shoes and there was a giant magnet underneath the ground. It wasn’t even that I ran badly—it was like I didn’t know how to run at all. Before I tried out, I was pretty sure I wouldn’t make the official team, but I was confident I’d make alternate. I mean, I’ve been running long distance since I was nine—how could I not make alternate? But I’m guessing the coach prefers that his alternates actually know how to put one foot in front of the other, which I clearly do not.

On top of all that, I now know exactly who Regina Deladdo is because I’ve had to sit through a million football games to watch Tracy cheer—or try to watch Tracy cheer. Since she’s new on the team, she’s always in the back row. Not that I care. Tracy introduced me to Regina after one of the games, probably to make a point. I could practically see the thought bubble above Regina’s head that said, Tracy, why the hell are you wasting my time introducing me to a nobody freshman?

And last but not least on my Things That Suck This Year list: yesterday my mother told me she wants me to see a shrink to talk about the panic attack I had over the summer. But I’m not even sure that what happened to me at the movie theater was a panic attack. Maybe I just couldn’t breathe because the theater was crawling with mold or mildew or something. Anyway, I’ve been fine ever since. Except for that day in the bathroom when I was hiding from Jamie after school. But that was probably just from the smoke.

Whatever.

I hate my life. And this morning, I feel like taking it out on Robert.

“If you didn’t smoke cigarettes,” I yell back at him as I run faster, “you could probably catch up with me!”

“Come on, Rosie! Rosie the Rose! Just wait up for a second!”

I stop running. He drops his cigarette and keeps walking toward me. I point at it. He stops, turns, steps on it and starts toward me again.

“You’re such a Goody Two-shoe.”

“Two-shoes. Two. Shoes. Plural.”

“Want me to carry your books for you?”

“What is this, the 1950s?” I ask.

“Going to homecoming?”

I bust out laughing. “You’re chasing me down the street at 7:00 a.m. to find out if I’m going to a dumb dance that’s, like, two months away?” I say, walking faster toward school. I’m well aware that I am being unnecessarily mean, but I can’t help it. “It’s only October, Robert. Homecoming is before Christmas.”

“Yeah? So?”

I sigh. “Just ask me if you want to ask me,” I say bitchily. Robert has the ability to bring out the absolute worst in me. Lucky him.

The fact of the matter is, all the freshmen are talking about homecoming already. We started talking about it in elementary school because of the big fight that happened during Peter’s freshman year. Well, not just because of that—also because it’s the first big dance in high school, and it’s cooler than prom because all the alums come back. But the fight was a big deal.

Most normal schools have homecoming at Thanksgiving, but Union High had to change its homecoming after a bunch of alums from rival high schools practically started a riot. Now all the neighboring towns stagger their dances so that no two homecomings are on the same night. This year, ours is right before Christmas break. There are still fights, but at least the fights don’t involve morons from multiple schools. Only morons from one school.

“I don’t want to ask you,” Robert says. “Jamie Forta asked me to find out.” My teeth suddenly hurt from the cold air, and I realize my mouth must be hanging open. “Huh. So it’s true.”

If I’d thought about it, I would have guessed that a) Jamie would rather die than go to homecoming, and b) he would never ask Robert to do anything for him. He probably has no idea who Robert even is. If I’d thought about those things, my mouth would have stayed closed. “You’re a jerk, Robert.”

“But it’s true, isn’t it?”

“No, it’s not.”

“You don’t even know what I’m talking about.”

“All right, what, then?” I say, so annoyed with him that I want to shove him like I did in sixth grade when we had a fight over a game of four-square on the playground. He wanted to shove me right back—I could tell—but instead he lectured me about how a gentleman does not shove a lady. And he did it in the bad British accent that he used for the school’s abridged production of My Fair Lady that year. Girls from that year still call him Henry occasionally, and he loves it—“Good day, Ladies,” he replies, sounding like Prince Charles. In junior high, girls giggled when he did that—now they roll their eyes and make fun of him. But he keeps doing it.

“I’m talking about you and Forta,” Robert answers, reaching into his pocket for another cigarette.

“Don’t smoke those things around me. It’s too early in the morning.”

“I can do whatever I want.”

“Fine. Start killing yourself at fourteen—”

“Fifteen. Soon to be sixteen.”

“Whatever. See if I care.”

“Are you going to homecoming with him?” Robert asks.

“Why would you think that?”

“I don’t know. I just get the feeling that he likes you.”

“He doesn’t like me, Robert. He doesn’t even know me.” My face is getting hot.

“I saw him watching you at track tryouts yesterday.”

I’m kind of astounded, but not so astounded that I can’t correct Robert. “Cross-country. Track is in the spring.”

“Well, yeah, but you were running around the track.”

“Where did you see him? And what were you doing there?”

“I was just hanging around,” he says a little sheepishly. “I saw him going to his car in the parking lot, and he just stood there for a minute, watching you run.”

My brain is so scrambled that I don’t know what to say. The thought of Jamie watching me run is too much to process. I try to remember what I was wearing yesterday. My favorite gross sweatpants; a Devendra Banhart T-shirt; my old Union Middle School sweatshirt. Hopefully, by the time he was watching, I’d taken off the middle school sweatshirt. Although that would mean that I’d been feeling pretty hot and sweaty at that point, which is not when I’m at my most attractive. Not that I have any idea when I’m at my most attractive. Or if I even have a most attractive.

“Do you know how old that guy really is, Rosie?”

Not this again. “Why are people obsessed with how old Jamie is? He’s a junior.”

“He’s an old junior.”

“Aren’t you the oldest person in the freshman class, and about to become the first person in our class who can drive? Isn’t that a little unusual?”

He looks at the sky, squinting into the morning sun. “My credits didn’t transfer,” he mumbles.

“That’s why you had to do sixth grade again when you moved here? It wasn’t because you were held back?” I ask. He doesn’t respond. “Stop talking about Jamie like you’re automatically better than him, okay?”

He lights his cigarette and turns his head to the side to exhale while keeping his eyes on me. I am sure he saw Chuck do this on Gossip Girl, and I bet he’s been practicing in the mirror ever since. I suddenly hate that stupid show.

Apparently I hate everything these days.

“I don’t know what you see in that guy. Especially since you could have me.”

Robert has crystal-blue eyes and jet-black hair. There’s no doubt that he’s cute. Last year, he had gaggles of little drama-department geeks trailing him like a Greek chorus. Actually, after he played Jason in Medea, he literally did have the Greek chorus following him around, giggling over everything he said or did. Of course, the irony is that Jason is not exactly the most honorable character in Greek tragedy. He left his wife Medea for another woman, and she went mad and killed their children to piss him off—or, more accurately, to destroy him.

You would think that the actor playing Jason would become less attractive due to his character’s misdeeds rather than more attractive, but the Greek chorus could not get enough of Robert. Maybe the anachronistic biker jacket and leather boots he wore on stage canceled out the fact that he played a two-timing jerk.

Sometimes Robert used the Greek-ettes to try to make me jealous. It never worked.

In June, Robert came to my father’s memorial service. He sat right behind me and handed me a clean tissue every few minutes. My mother will always love him for that. I try to remind myself of that kindness every time I want to tell him to get lost. I usually end up telling him to get lost anyway.

“You could have me, you know,” Robert repeats.

“You’re just what I need, Robert. A convicted felon.”

“Stealing from H&M is not a felony.”

“You mean stealing from H&M twice is not a felony.”

“Sure, that, too.”

Robert has a crappy life, and sometimes he does bad things, like steal and lie. He lives with not one but two stepparents. His mother bailed and his father got remarried. Then his father bailed, and his stepmother remarried, and Robert ended up with her and her new husband. Is that even legal? I have no idea. But it definitely seems crappy to me. As annoying as Robert can be, even he doesn’t deserve that.

He makes another big show of inhaling and exhaling, blowing the smoke through his nose. “Forta likes you.”

“I am not the kind of girl he likes. He likes the Regina Deladdos of the world.”

“Tracy said he carried your horn and opened the car door for you that time.”

“Maybe he was raised well.”

“He doesn’t look like it. He wears the same clothes to school every day.”

“That’s the kind of thing a girl would say.”

“Tracy said it,” he admitted.

“She would notice.”

“Robert and Rosie sounds better than Jamie and Rosie.”

I look at him for a second, this guy I’ve known since I was eleven, and he looks hurt. To be honest, I like the sound of Jamie and Rosie. Robert and Rosie is too much alliteration for me. But I’m not going to say that. I’ve already been mean enough for one day, and it’s only seven-fifteen. Besides, I don’t feel like reminding him what alliteration is.

“I’ve always aspired to select my relationships based on how they’ll sound inscribed on the wall in the lavatory,” I say.

“Stop talking like that, AP English.” He grabs my coat to make me stop walking. “Will you go to homecoming with me?”

I knew this was coming. And even though homecoming is two months away, I’m kind of surprised it took him this long, considering he’s been suspicious of Jamie since the first week of school, and also considering that everyone we know has already decided who they’re going with. Tracy’s going with Matt, who still isn’t speaking to me, which is fine, because I’m not speaking to him, either. Stephanie is going with the swim-team thug that Tracy and Matt set her up with this summer, Mike Darren. Everyone knows who they’re going with except me. And Robert.

To be honest, I don’t want to go. I’m not in the mood for dancing these days—go figure. But I have to, or I’ll never hear the end of it from Tracy. Or my mother, for that matter. My mother expects me to go on living as if everything were still completely normal. She seems incapable of understanding why I might not feel like going to a dance right now. She seems incapable of understanding me in general.

I look at Robert. “Do you promise not to lie to me ever again?” I ask, knowing full well that this is not a promise he’ll be able to keep.

“I didn’t lie about anything!”

“You told me Jamie Forta asked you to find out if I was going.”

“That wasn’t a lie, that was a tactic.”

“It was a lie.”

He drops his cigarette and concentrates hard on putting it out with his thrift-store Doc Martens. I wonder if he paid for those boots or if he acquired them on one of his “excursions.”

“Sorry,” he mumbles. “But I was only using it as a tactic. It wasn’t going to stay a lie.”

I’m not entirely sure what that means, but I get the gist. I start walking again. He follows me.

“Do I have to wear a dress?” I say.

“It would be nice.”

“Do I have to wear makeup?”

“I don’t care.”

“High heels?”

“Rosie!”

“Okay, I’ll go.”

“Don’t sound so excited,” he says.

“I don’t like dances.”

“What are you talking about? You love dancing!”

“Dances and dancing are two separate things.”

He rolls his eyes. “But you’ll go?”

“Yes, Robert. I’ll go.”

“Okay,” he says, looking so happy it makes me regret saying yes.

envenom (verb): to make bitter, to fill with bad feeling

(see also: Regina’s specialty)

6

TRACY'S HALLOWEEN PARTY already sucks and it hasn’t even started. She decided to throw the thing as soon as she made cheerleading last month because apparently it’s important for the new girls to kiss up to the older girls. She doesn’t put it that way, though—she says the younger girls have to pay their dues by hosting parties and things like that.

She keeps talking about how pretty the cheerleaders on “the squad” are, like being pretty is the most important thing in the world. When I roll my eyes, she just shakes her head like I couldn’t possibly understand how important all this stuff is. And she’s right—I don’t. I don’t think we should still have cheerleaders that prance around in short skirts repeating stupid rhymes, flashing their underwear to cheer on boys without doing so much as a cartwheel. It’s the twenty-first century—shouldn’t we be more evolved than this?

If Tracy weren’t my best friend, I wouldn’t be here hanging decorations for a “cheer party” while she and Stephanie finish putting on their costumes and looking for the key to Tracy’s parents’ liquor cabinet. I’d be home, probably, secretly wishing I were still allowed to go trick-or-treating and watching something on HBO without permission while my mom was locked away in her office writing up her notes on all the crazy kids she listened to that week. Or I’d be… I don’t know where else I’d be. I spend all my time with Tracy, so it’s kind of hard to know what I’d be doing if she weren’t my best friend.

This is the first time Tracy’s parents have ever left her home alone, and I know it will be the last. I tried to tell her that this party is a bad idea and could get her into serious trouble, but I don’t think she actually hears me when words come out of my mouth anymore. Her house is beautiful and her parents collect antiques. Like, real antiques, shipped over from England and Portugal. When I mention this to Trace, she just says, “That’s why we’re having the party in the basement! There’s nothing valuable down there.”

I refrain from asking her if she’s going to lock everyone in, making them come and go through the little windows that are high up near the ceiling.

Something tells me that the two of us are not going to have an easy year.

We had a big fight earlier, when we were making chocolate-chip freezer cookies for the party. She told me that she and Matt were going to do it tonight. I told her that I had finally decided that fifteen is too young. She didn’t like that at all. She changed the subject, saying that I need to find an activity, or a group, or something so that people will know who I am. “Like, you know, I’m known as a cheerleader now,” she said. “What are they going to say about you? And don’t say, ‘She plays French horn in the orchestra’ because, I’m sorry, but that’s just lame.” I shoved some candy in my mouth to stop myself from saying, At least playing French horn takes some talent. Instead I said, “I’m a runner” to which she replied, “Not on a team, you’re not,” to which I replied, “Well at least running is a real sport, not like cheerleading,” to which she replied, “It’s good enough for Regina and she’s Jamie’s girlfriend.”

I almost punched her.

She hasn’t mentioned Jamie in a long time, probably because the last time she brought him up, I still wouldn’t tell her anything. That made her so mad that she started texting someone on her stupid phone right in the middle of our conversation, which she totally knows makes me crazy.

Of course, what she doesn’t know is that there’s nothing to tell about Jamie. Except maybe that a few weeks ago he watched me run laps around the track during tryouts, according to Robert. But now that Jamie and I don’t have study hall together anymore, we never talk. If he makes eye contact with me in the hall, maybe he’ll give me a little nod, but that’s it. I wonder if he’s freaked out by our last conversation. I guess I can understand that—I mean, we don’t even know each other, and I basically asked him how many people he’s had sex with. Dumb.

“Rosie, where’s your costume? It’s almost time,” Stephanie says, coming downstairs to the basement where I’m about to fall off a ladder, hanging fake spiders from the ceiling. She’s dressed as Lady Gaga. Or maybe Katy Perry. I’m not really sure which, since they both like crazy wigs, corsets and stupidly high heels.

“Um, I don’t… I’m not dressing up this year.” As I hang the last spider, I notice the blue nail polish I put on in honor of Halloween is already chipped.

“You have to! Oh, my god! Tracy will kill you if you don’t!”

“I’m not staying, Steph. I’m not in the mood for a party.”

Stephanie sort of shuffles her patent leather platforms around on the floor and then squints up at the orange-and-black streamers that run the length of the ceiling, twisting around each other with the spiders poking through. She takes a single blue M&M out of a bowl on the food table and pops it in her mouth.

Stephanie is truly one of the nicest people I know, which means that she gets caught in the middle a lot. Tracy and I met her in middle school last year, when she moved from southern Illinois with her mom after her parents got divorced. She’s more Tracy’s friend than mine, especially since she started dating Mike over the summer. I’ve wanted to ask Tracy for a while now why she and Matt didn’t set me up with anyone this summer, but I’m not sure I want to hear the answer.

“Are you leaving because Tracy’s mad at you?” she asks.