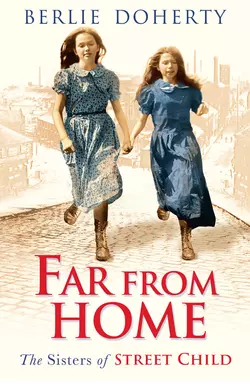

Far From Home: The sisters of Street Child

Berlie Doherty

The sisters of STREET CHILD tell their story…A companion novel to bestselling story of Victorian orphan Jim Jarvis based on the founding of Dr Barnardo’s homes for children.When Jim Jarvis is separated from his sisters, Lizzie and Emily, he thinks he will never see them again. Now for the first time, the bestselling author of STREET CHILD reveals what happened to his orphaned sisters.In Victorian London, Lizzie and Emily are left in the care of a cook but their story takes them to the mills of northern England. There, under the keen eyes of the mill owners, the girls are made to work in harsh conditions and any chance of escape is sorely tempting…An incredible new STREET CHILD story based on the true experiences of Victorian mill girls.

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2015

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Far From Home

Text copyright © Berlie Doherty, 2015

Cover design © HarperCollins Publishers 2015

Berlie Doherty asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007578825

Ebook Edition © 2014 ISBN: 9780007578696

Version: 2014-11-19

Praise for Street Child, the companion novel to Far From Home:

‘A terrific adventure story, heart-warmingly poignant and a tribute to the resilience of the human spirit. A magnificent story.’

Daily Mail

‘Berlie Doherty has magic in her’

Junior Bookshelf

For Tommy, Hannah, Kasia, Anna-Merryn, Eda, Leo and Tess

CONTENTS

Cover (#u0332de66-a93e-5c4f-9f28-c3f44b68eff4)

Title Page (#u7ad8ddf7-2cc1-550a-a94f-9e05393bf505)

Copyright (#u7ae6ccbd-7b86-578d-b341-55743a2a34b3)

Praise (#u96507235-db60-5b89-8e24-aba1de017b28)

Dedication (#u570015ee-efe5-58ae-a91d-3f857cf624fc)

Tell Me Your Story, Emily and Lizzie

1. Take Us With You, Ma

2. Safe Till Morning

3. The Two Dearies

4. Lame Betsy

5. Where You Go, I Go

6. Snatched in the Night

7. No Charity Children Here

8. Alone

9. Mrs Cleggins

10. We’re Going to a Mansion, Remember?

11. Bleakdale Mill

12. What Kind of Life?

13. A Pattern of Sundays

14. Winter

15. Miss Blackthorn

16. I Knew Your Ma

17. Cruel Crick

18. Sunshine

19. I Can Buy Our Freedom

20. Buxford Fair

21. Clog Dancing

22. Bess

23. The Lost Children

24. The Terrible Accident

25. No News for Emily

26. Where Am I?

27. Robin’s Plan

28. The Sheen

29. Revenge

30. I Can’t Remember

31. After the Fire

32. A letter from Dr Barnardo

33. Plans

34. One Last Thing

Acknowledgements

About the Author

By the same author

About the Publisher

(#u064a5d2e-1f89-5893-b407-677bd0972535)

We’re Emily and Lizzie Jarvis. We’re sitting by the window in our room. Outside, we can hear a soft kind of sighing, like the wind in the trees, though we know it isn’t that really. It’s a comforting sound, and it’s lulling us to sleep. But we can’t sleep yet. There’s so much to think about first, so much to talk about. So much remembering to do.

Would you like to know our story?

There used to be five of us in our family, and now there’s only two. After Pa died we had to move into a room in a big, crowded tenement house with Ma and our little brother, Jim, and we just managed to keep going because Ma got a job as cook in a Big House. But then she fell ill and she had to stop working. There was no money left to live on, no money for the rent. She gave her last coin to Jim and told him to buy a nice pie for us all, full of meat and gravy. He was so excited. He was too young to understand that Ma thought it was the last good meal we would ever have. But she couldn’t eat it, she was too ill.

And then the owner of the room came for the rent, and when he saw Ma’s empty purse, and her too sick to earn anything, he turned us out on the streets. Where was there to go? Ma took us to the Big House, down the steps to the kitchen, and she begged her friend Rosie to look after us. And then she told us we must stay there, without her. She must take Jim with her, and she must leave us behind. It broke her heart to tell us that, we knew. It breaks our hearts to think about it. But we must think about it. We must tell our story, every bit of it, so we never forget what it was like for us before we came here.

This is our story.

(#u064a5d2e-1f89-5893-b407-677bd0972535)

“Take us with you, Ma! Don’t leave us here!” Lizzie begged.

“I can’t,” her mother said. She didn’t turn round. “Bless you, I can’t. This is best for you. God bless you, both of you.”

Mrs Jarvis took Jim’s hand and bundled him quickly out of the door. It swung shut behind them with a loud thud.

Immediately Lizzie broke into howls of grief. “Ma! Ma! Don’t leave us behind!” she sobbed. “Don’t go without us!”

She tried to wrench open the door, but her sister put her arms round her, holding her tight. “It’s all right. It’s all right, Lizzie,” she whispered.

“We might never see them again!” Lizzie shook her away and covered her face with her hands. She didn’t want to see anything, didn’t want to hear anything.

“I know. It’s just as bad for me,” Emily said. “I didn’t want her to go. I didn’t want Jim to go.” Her voice was breaking up now; tiny rags of sound like brave little flags in the wind. “But Ma had no choice, did she? She wants to save us; that’s what she said. She brought us here so Rosie can take care of us.”

Rosie, their mother’s only friend in the world, came over to the two girls and drew them away from the door. “I’ll do my best,” she told them. She sat them down at the kitchen table where she had been making bread for the master of the house. She started smoothing flour away with the wedge of her hand, then tracing circles into it with her plump fingers. It was as if she was looking for words there to help her. All that could be heard were the shivering sobs that Lizzie made.

“Listen, girls,” Rosie said at last. “Your ma’s ill. You know that, don’t you? She ain’t going to get better.”

Lizzie stifled another sob. This time she let Emily creep her hand into her own, and squeezed and squeezed to keep the unimaginable pain of those words away.

“And you heard what Judd said? She’s the housekeeper, and what she says, goes. She’s the law round here, she is. She said she’d let you stay a bit, if you keep quiet and hidden, but not for ever. She can’t be feeding two grown girls on his lordship’s money, now, can she? She’d lose her job if he found out you were here, and so would I. I’ll do what I can for you, I promise, but I really don’t know what it is I can do. But at the very least I’ll save you from the streets, or even worse than that, from a life in the workhouse.” She shuddered, rubbing her stout upper arms vigorously as if the thought of the workhouse had chilled her bones. “Never, never. I’ll never let you go there, girls.”

She flapped her hands along her sleeves to try to dust away the flour.

“Busy, let’s be busy! Em’ly, you’ve got bread to make. See if it’s as good as your ma used to make. Lizzie, you’ve got a floor to sweep because I can’t touch flour without getting it everywhere I turn! And I’ve got a fire to mend. For pity’s sake, look at it! It’s crawling away like a rat down a hole.”

She lifted a pair of bellows from the side of the range and knelt in the hearth, working them into the dying embers to coax the flames back, then threw some knuckles of wood onto the glowing ashes. She sat back, watching the dance of the flames, and listened to the girls behind her. She could hear Emily standing up at last from the bench and starting to knead the dough on the table, popping the air out of it with a sure, firm touch, and at last settling into a rhythm, breathing with a slow kind of satisfaction as she did so. Rosie smiled to herself. She sounds just like her ma, she thought. And nothing ever calmed Annie Jarvis down as much as making bread. I’d enjoy working with Em’ly in the kitchen, if only Judd could find a way of letting her stay. Annie’s daughter, working alongside of me. What a pleasure that would be.

She lifted coals onto the fire, one by one, taking time over her task, not wanting to disturb the girls. At last, she heard Lizzie push the bench away and stand up; heard her gently sweeping the floor with the kitchen broom, scattering drops of water as she went so the dust didn’t fly. Rosie turned and saw that tears were still streaming down Lizzie’s face, burning her cheeks. “Ma, Ma,” she whispered as she worked. “I want you, Ma.”

As soon she had finished that task Rosie asked her to help with setting a tray to take upstairs, and with sorting out clean knives, forks and spoons to be locked away by Judd in the silver cabinet. The cutlery jittered in Lizzie’s hands, she was so scared of making a mistake, but at last the job was done and Rosie smiled her satisfaction.

“We get along very well in this job, don’t we, girls?” she said. “I think I can even sit down for a minute now.” She eased herself onto the bench, slipping her boots off, wriggling her toes.

There was the sudden pounding of feet down the stairs, the kitchen door was flung open, and there stood the housekeeper, lips pursed, grey eyes sharp and cold as points of ice. Rosie jumped to her feet, as though she’d sat on a cat.

“His lordship has come in early from his afternoon walk,” Judd announced. She jangled the keys that were hanging in a bunch from her belt. “I want you to get these girls out of my sight.”

“But he never comes down here, Judd,” Rosie said. “And the mistresses are away.”

“I said, out of my sight.” Judd took in the blazing fire, the clean floor, the dough rising plump as a chicken in the bread tins, and sniffed. “Now! I’ve never seen them in my life.” She turned her back, arms akimbo, so her elbows stuck out sharp and angled in her tight black sleeves.

Rosie took the girls by the hand and hustled them into the pantry. “He never comes down to the kitchen,” she muttered. “Judd’s behaving like a mother goose watching out for the fox. I’ll let you out when I can.”

She closed the pantry door quietly. The glow of the fire disappeared, and the sisters stood in complete darkness. Lizzie moved, and something thumped against her face. She stifled a shriek of shock, and nervously lifted up her hand to feel what it was, her other hand grasping Emily’s arm.

“Ducks!” she whispered, feeling a brace of the birds hanging above their heads. “Dead ducks!” and for some reason all the emotions of the day, the need to be quiet, the strangeness of everything, the knowledge that Emily was standing next to her breathing the same ducky air, and that Judd was watching out for his lordship, the fox; everything about the day welled up in her, until a pent-up explosion of sound burst out of her mouth.

“Are you crying?” Emily whispered.

“No,” Lizzie whispered back. Her voice was shaking. Her whole body was shaking. Tears of pain and laughter burnt her cheeks. “I am a bit. But I can’t stop giggling, Emily. Can’t stop.”

(#ulink_624d43f9-7a3a-598e-947d-426f1dfe6a59)

It seemed as if hours were passing while Emily and Lizzie stood in the dark pantry, listening to the to and fro of bustle in the kitchen: food being scraped off plates, pans being washed, the fire being raked. All this time they daren’t move, except to lower themselves away from the dangling ducks and squat down on the cold stone floor. Eventually the door opened a crack, the glow of a candle warmed the darkness, and Rosie’s face appeared.

“Me and Judd have finished down here,” she whispered. “I’ll put some cold meat out for you, and you must eat it before the mice do. There’s a water closet in the back yard for your necessaries, and a couple of rugs by the fire, so you can curl up there. Out you come.”

She helped them to stand and they stumbled out, stiff and cold, into the cosy firelight of the kitchen. Rosie rubbed their numb hands to warm them up. Her face was creased with concern. “His lordship’s eaten his supper, and he’s dozing in front of the fire like he always does when the ladies are away. He’ll totter off to bed any time now, so you’re quite safe till morning.”

“Is his lordship really a lord?” Lizzie asked.

“Heavens, no!” Rosie laughed. “We’d be in a much bigger house if he was, and there’d be servants all over the place. No, he’s a barrister or something like, and he can be as grumpy as I don’t know what if we get things wrong by mistake.” She led the girls over to the table and pushed the plates of meat and potatoes in front of them.

“He makes us feel like criminals sometimes because his coffee’s not hot enough or there’s too much salt in his potatoes. He hates it when the mistresses are away and there’s just him and the two Dearies. He can snap at you like a bear with a sore head sometimes.” She sat on the bench next to Lizzie and untied her house boots, letting her toes wriggle deliciously in the air. “Ooh, that’s better. Judd’s right, he’d put us out on the street, all of us, if he thought we was doing something behind his back, feeding waifs and strays.”

“We’re not waifs and strays!” Lizzie protested.

“We are now,” Emily reminded her. “Where’s home, now Mr Spink has kicked us out?”

Rosie undid the ties of her cap and loosened her long, dark hair. She patted Emily’s hand and stood up. “But he ate every bit of that bread you made, Em’ly, and then asked for more! That’s the first time since Annie left off working here. So we’ve high hopes for you. But then you might do me out of a job, and where would I be? You teach me, just like your ma taught you. It’ll take a bit of doing, so I’ll need you here a while!” She bent down to pick up her boots, and quickly kissed the tops of their heads. “Good night, girls. God bless.”

“I’m too tired to eat anything,” Lizzie said when Rosie had gone, locking the door behind her. “I just want to go to sleep, Emily.”

“You heard what Rosie said. Eat, before the mice get it. And suppose we get chucked out in the middle of the night? We’ll wish we had food in our bellies then, won’t we?”

Lizzie swallowed her cold meat dutifully, and Emily did the same. It was good meat, she could tell that, tender and tasty, but every mouthful seemed to clog up her throat and choke her. She cleared the plates away and then curled up next to Lizzie in front of the fire.

“You won’t stay here without me, Emily?” Lizzie murmured.

“Course I won’t. I’ll never leave you, Lizzie.” She stared into the pale flicker of the dying flames. “I wonder where Ma and Jim are now?” But Lizzie was already asleep. Images of Ma’s face swooned in and out of the darkness. It was as if, for a moment, she was still there with them, until the room grew into its night-time dark around her. “Please, God, let them both be safe,” Emily whispered. “Please let someone as kind as Rosie take care of them.”

A grey and drizzly dawn was seeping down through the basement window when Rosie shook the girls awake.

“I shall have to move you so’s I can get this fire lit,” she said. “Let’s hope that other nice loaf of yours was cooked proper before it went out, cos I forgot all about it in the excitement. That’s my trouble.”

“It’s all right, Rosie. I saw to it.” Emily yawned and opened the oven door to lift out the new loaf, freshly baked and barely cool. It smelled wonderful.

“Just how he likes it!” Rosie marvelled. “He’ll be a happy man this morning. He won’t be complaining that he’s breaking a tooth with every bite of my bread.”

Lizzie sat up and huddled the rug round her shoulders. She stared blankly round the strange kitchen, dazed by memories of yesterday: her mother, bent with pain and weakness; her brother, white-faced with shock and sorrow as he was bundled outside; the slam of the door; the sound of her own fists pummelling. Don’t leave us behind! Don’t go without us! Dimly she heard Rosie chattering away as if today was a day like any other.

“There’s a pump in the back yard to wash the sleep out of your faces,” she was saying. “And while you’re out there, you can pump up some water for me to boil for his breakfast tea, Em’ly. Lizzie, here’s a bowl of scraps; you can chuck these at the hens in the yard. I’ve got to fetch coal and get this fire going again. Then we can start the day proper.”

It was cold and damp in the yard, with a few sparks of snow in the air. Emily pumped up water to splash on her face, then nodded to Lizzie. Lizzie dipped her face down and then lifted up her head from the water; gasping with cold, her hair damp and clinging to her cheeks.

“Now you’ll feel a bit brighter,” Emily said. “And you like hens, so you’ve got a nice job to do next. And I reckon Jim would have liked my job, sprat though he is! He’d pretend he’s got muscles!” She paused, shocked with memory. I don’t know if we’ll ever see him again, she thought.

As if she had heard her, Lizzie burst out, “Why did Ma take him away with her, and leave us behind?”

“How could she leave him here? How could she expect Rosie to help all three of us?” Emily snapped. There came the tears again, sharp as needles behind her eyes. She smiled weakly at her sister. “Do your job, just do it. Let Rosie be pleased with us.”

The kitchen was warm again when they went back in. Rosie was trudging up from the cellar with a bucket of coal in each hand.

“I’m going up to light the house fires,” she told them. “Luckily, there’s only four to do today, as the mistresses are away.”

“What shall we do?” Emily asked.

“You could lay his tray for breakfast,” Rosie said. “He has tea, a boiled egg, bread and butter, and marmalade. I’ve put some aside for us, but we have it when he’s done. When you hear Judd coming down you’ll have to hide for ten minutes, while she has her breakfast. We have to pretend you’re not here, then she can say she knows nothing about you. Silly woman. I think she’ll relax a bit once his lordship leaves for work.”

Lizzie found the things that were needed for the tray. Emily put the kettle on the hob to boil, and sliced and buttered the bread neatly. When they heard footsteps on the stairs they scrambled into the pantry and waited, breathless, listening to Judd scraping porridge from the pan and slicing herself some bread. They heard Rosie return and Judd giving her orders for the day, and then their door was opened and they stumbled back into the light of the kitchen.

“Breakfast soon,” Rosie said. “I don’t know about you two, but I’m starving. It’s making the fires that does it, lugging ashes down the stairs and coals up. And when the mistresses are here there’s even more fires to do.”

“What are the mistresses like?” Lizzie asked.

“Well, his wife is as sour as a crabapple and his sister is like a crocodile! Heard of crocodiles? They’re all teeth and snap. That’s what she’s like. They’re away visiting relatives in the country, so things are a bit easy just now. But when they get back, I’ll be hustled off my feet. And then there’s the two Dearies.”

“And is there just you and Judd looking after everyone?”

“Lor, do you never stop asking questions?” Rosie gasped. “The Crabapple and the Crocodile have taken their own maids with them. They wouldn’t have me or Judd touching their clothes or their hair. Those maids are a hoity-toity pair, and I’m always glad to see them gone. And there’s a girl who comes in weekdays to help Judd with the beds and the dusting and polishing upstairs. Judd’s training her, but she’ll never be much good. She’s as lazy as a cat.”

“I could do her job!” Lizzie said, but Rosie shook her head. “She’s Judd’s niece,” she mouthed, glancing at the door. “That’s how it works in service. Someone speaks for you, and if you get the job, they have to train you and be responsible for you. I was lucky. Your mother spoke for me. She used to buy salmon and shrimps off me for his lordship’s supper, and we got to be pals. Like sisters. Oh.” She covered her face with her apron and emerged, red-eyed. “How was she to know I couldn’t make decent bread for the life o’ me!”

One of the bells over the kitchen door jangled sharply, making Lizzie jump.

“That’s it,” Rosie said. “Time for his lordship’s breakfast. Let me see. Bread’s done. Tea’s done. Tea cosy, marmalade, bread, butter, cup, saucer, spoon, milk, plate, knife. Sugar. Well done, Em’ly love. Tra-la! Open the door for me, Lizzie.” She sailed out of the kitchen and up the stairs with the tray, humming to herself.

Emily hugged her sister. “It’s all right here,” she said. “We’re fine for a bit, aren’t we?”

“Maybe Ma will be able to come back and fetch us, when she’s better,” Lizzie whispered. “That’s what I want.”

But Emily just shook her head, too upset to answer. She looked away, forcing back the sharp sting of tears before she could speak again. “Just try to be happy here, Lizzie. That’s what Ma wants for us. I like this big warm kitchen, and all the shiny pots and pans. I like being where Ma used to be when she was well, and doing the sorts of things she used to do, and cooking lovely food. I hope Rosie speaks for me. If I can’t be with Ma, and I know I can’t, I hope I can stay here.”

(#ulink_eb220493-4994-5275-a2ea-8f3b2af5ff74)

Lizzie turned away from her sister and slumped herself down on the bench. She knew Ma had loved this place too. Sometimes she used to bring bits of pie and bowls of stew home, when Judd allowed her to, and told the girls exactly how she had cooked them before she doled out their share. “What’s lovely, is cooking with good quality food,” she told them. “I can only afford scrag-ends and entrails for us usually, and coarse flour for bread. I do my best to make it taste good – but ooh, it’s another world, the way they live at the Big House. I want that for you, girls. Working in a fine big house!”

“I’d prefer to live in one!” Lizzie had said, and they had all laughed because the very idea was so crazy.

But here they were in the Big House, and Emily was doing her best to be as useful and as good a cook as Ma had been. Rosie wanted her to stay – that was clear. Lizzie bit her lip. What about me? she wanted to ask, but daren’t. What if Rosie spoke up for Emily and got her a job there? What if Emily could stay, and Lizzie couldn’t? What if Rosie couldn’t find another job for her? She hardly dared to let herself think about it. What would happen to her, wandering the streets all on her own? She’d rather go to the workhouse. She watched miserably as Emily busied herself tidying away pans, washing Judd’s breakfast plates, putting fresh water to boil. She seemed to know exactly what to do here, where things went, how to keep the kitchen neat and clean. She was even humming to herself as she worked. It’s true, Lizzie thought. She loves it here. Even though she’s crying inside like I am, she’s found out how to be a little bit happy.

At last Rosie came back down carrying the tray. “Look at this! All gone!” she said. “Judd said he didn’t say nothing, but he couldn’t take his eyes off your bread! His nostrils were twitching as if he was sniffing roses!”

She put the tray down, and Emily took the plates over to the sink immediately to wash them. Why didn’t I think of doing that? Lizzie wondered.

“He’s out for the day soon, so we can breathe clear, but Judd tells me he’s bringing a business acquaintance back with him this evening. She’s got to show the Lazy Cat how to get a room ready for him, so I’m to do the shopping today. He wants steak and kidney pie for supper. I’ll do the meat, cos I love doing that, and Em’ly, you can have a go at the pastry because your ma’s was always a dream. Oh, good girl, you’ve put more water on. Let’s have breakfast, and then you and I can go together for the meat, Em’ly. Would you like that?”

“Oh, I would!” said Emily.

Lizzie forced herself to stand in front of Rosie. “What can I do?” she asked timidly.

“What can you do, my love? What can you do, that’s the trouble. Ah, I know. You can take the Dearies their breakfast. They’ll be awake soon. That’s a job I hate, and the Lazy Cat can’t stand them, but you might like it. It’ll cheer them up to see a pretty little girl like you. You can get the tray set now. Tea, bread and butter. Sometimes a bit of marmalade. That’s all they ever have.”

“How many Dearies are there?” Lizzie asked. She wiped his lordship’s tray carefully and reached up to the shelf for clean plates.

“Two of course. His mother and hers.”

“What if they tell his lordship about me?”

“They won’t,” Rosie chuckled. “They forget everything five minutes after it happens, bless them. And even if they did tell him, he’d think they’d made it up.”

I’ll do it so well, Lizzie told herself, that Rosie will decide she wants me to do it every day, and she’ll speak for me. She set the tray carefully with china cups and saucers, plates, teapot.

“Shall I do the bread and butter for you?” Emily asked.

“No. I want to do it myself,” Lizzie insisted, but Rosie watched anxiously as she sawed at the loaf, tearing off a huge wedge.

“They’ll never be able to chew a piece that big. Let me cut it nice and thin for them, and you can have that piece as an extra treat.”

Emily started to sweep Lizzie’s breadcrumbs up, and Lizzie snatched the broom away from her. “I know how to sweep the floor! I did it yesterday, remember?”

Emily shrugged and caught Rosie’s eye. “She’s always like this. Ma used to call her Little Miss Independent.”

“And there’s nothing wrong with that,” Rosie said. “Sisters are s’posed to help each other though, Lizzie. Let brothers do the fighting.” They heard the upstairs door closing and saw a pair of feet walking past the window. “That’s him gone. It’s a wet day, and the streets will be muddy, so his boots will need a jolly good clean when he gets back.”

“I’ll do them,” said Lizzie.

“And they’re huge. He’s got feet like barges. The Crocodile’s the same; always huge, muddy boots to clean, or dusty ones to shine, every single night. Why they can’t spend a day in the house and give their feet a rest, I don’t know. No, they must go out, whatever the weather.” She poured boiling water into the pot and left Lizzie to set milk and sugar next to it. “There you go, Lizzie. There’s their bell too, just on time! The Dearies are ready for their breakfast, and breakfast is ready for the Dearies. Up the stairs, turn right, up the next stairs, first door on your left. Don’t wash them, Lizzie. That’s the Lazy Cat’s job, not yours. Come on, Em’ly. We’ll catch the butcher nice and early for the best cuts if we hurry.”

“Not nervous, are you?” Emily paused as she was picking up her warm cloak, watching Lizzie. She knew how her sister was feeling, with her pale face set in that determined way and her mouth drawn into a thin, tight line. She also knew that Lizzie was determined to do the job as well as she possibly could, for Ma’s sake, and that nothing, not even fear of his lordship himself, would stop her. “Good luck, Lizzie,” she said. She swung her cloak round her shoulders and followed Rosie out of the door.

Lizzie waited till the sound of their footsteps had gone before she dared to lift up the tray. “Up the stairs, turn right, up the next stairs, first door on my left. No, right. No, left. I’m sure it’s left. And I’ll do it so well that Rosie will speak for me.” She took a deep breath and edged her way out of the kitchen door and up the dark stairs.

Lizzie was so nervous that the cups rattled in their saucers like old bones. The door at the top of the servants’ stairs was closed. She lowered the tray down onto the top step and everything tilted dangerously sideways; the cups slid, the cutlery rolled, the tea slurped out of the spout of the pot. She held the tray firm with her shoe pressed against it because the step was so narrow. She didn’t want it tipping down the stairs. She turned the knob and pushed open the door, but as soon as she bent down to pick up the tray, the door swung shut again. She tried again, and the same thing happened. She was close to tears. “I could try holding it with one hand, like Rosie does,” she thought. “But I might drop it, and then what?” She decided that the only thing she could do was to get herself through the door first. She opened the door, stepped over the tray onto the landing, nearly dislodging it as she did so, and then crouched down so she was wedging the door open with her body. She leaned down, carefully lifted up the tray, and almost overbalanced. She was panting with effort and triumph when at last she managed to stand up and turn round. And there was Judd, arms akimbo, staring at her in amazement.

“What on earth is going on?” she demanded.

The contents of the tray chattered like loose teeth. “I’m taking the Dearies their breakfast.”

“Don’t you dare refer to them as the Dearies! They’re Mistress Rickett and Mistress Whittle. And you’re late. Get on with it, keep quiet, and don’t go into any room but theirs. Quick!”

A round pasty face appeared from another doorway behind Judd. The Lazy Cat! Lizzie thought. Well, I’ll show her how well I can do my job. Better than she can, any day. Judd stepped away, and Lizzie saw now that the hallway was glowing with colour: flowery wallpaper and carpet, red velvet chairs and curtains, a crystal chandelier gleaming with teardrops like a rainbow. It was not at all like the dingy kitchen down below stairs.

“What are you waiting for?” said Judd. “They won’t want cold tea, you know.”

The carpet was as soft as grass under Lizzie’s feet. At the top of the stairs she paused again. She had completely forgotten which way to go. The first door, but was it on the left or the right? There were six doors on the landing, and all of them were closed. She daren’t go back down again, daren’t face Judd’s wrath and the Lazy Cat’s scornful smile. Something told her it would be bad manners to call out. She put the tray down on a polished table and stood outside the first door on the right. I’m sure it was this one, she thought. She could hear nothing from inside. She knocked timidly, then more bravely. Still nothing. She turned the knob slowly and peeped inside. In front of her was a bed with a beautiful fringed quilt over it. Standing round the walls were huge pieces of dark wood furniture. There was a standard lamp with a fringed shade, and long, thick green curtains at the windows. But no Dearies. She closed the door softly. Her heart was thumping.

She crept to the door on the other side of the staircase, listened again, and now she could hear the mumble of voices. She knocked softly.

“Knock, knock!” called a voice from inside. “Tea, lovely tea!”

Lizzie opened the door, went back for the tray, and crept into the room. Facing her was a big iron bed with two old ladies sitting bolt upright in it. One had lost her nightcap, and her thin grey hair hung in long strand like cobwebs round her face. She clapped her hands together with delight. “Tea, Mistress Rickett! Tea!”

Mistress Rickett glared at Lizzie with round, pebbly eyes. “Who is it, Mistress Whittle?”

“Please, miss. Please, miss,” said Lizzie, glancing from one to the other and trying to bob a curtsy without dropping anything, “I’ve brought your breakfast.”

“Move over, Mistress Rickett,” the cobwebby one said. She patted a space clear on the counterpane that covered the bed. “Put the tray down. My mouth’s as dry as a desert. Look!” She poked out a yellow tongue.

“Who is it?” Mistress Rickett asked again.

“The tea girl. Pour it out, now! I’m parched.”

With shaking hands Lizzie did as she was told. She held out a rattling cup and saucer to each of the Dearies, then stood back, watching them sip their tea. She didn’t know whether she was supposed to go or stay. At last Mistress Whittle slurped her way to the bottom of her cup and handed it back to Lizzie.

“Pour me another. Plenty of sugar this time. Put some marmalade on my bread. Poke the fire. Open the curtains. Pour me some more tea.” Every so often the orders came, while the two Dearies worked their way through the tea and the bread and marmalade. But worst of all, definitely worst of all, was when the cobwebby one lifted up the counterpane and thrust out her skinny legs.

“Wash us.”

“Brush our hair,” giggled Mistress Rickett.

“Put us on the commode.”

I’ll do it, Lizzie thought grimly. Even though she knew it was not her job. I’ll do it so well that Judd will think I’m better than the Lazy Cat.

At last the Dearies were put back into bed, hair brushed and plaited (which Lizzie quite enjoyed doing), pillows plumped, fire blazing, teapot completely empty, all the bread and marmalade gone. Lizzie had spent all morning with them, and there’d been no sign at all of the Lazy Cat. She could hear her stomach rumbling and realised that she hadn’t eaten anything herself yet.

“Is there anything else?” she asked.

“Have you brought tea?” Mistress Whittle asked brightly.

“Who is it?” Mistress Rickett asked. But her eyes were closing, her head sinking back against the pillow. Mistress Whittle looked round at her, tried to nudge her awake, and yawned. She smiled sleepily at Lizzie.

Lizzie tucked the counterpane round them, picked up the tray, and tiptoed out of the room. “Please don’t wake up,” she whispered. “I’m famished!”

She went quickly down the stairs. No Judd. No Lazy Cat. She opened the door to the servants’ quarters and stepped down with a sigh of weary relief. The door swung shut behind her, knocking her so hard that she dropped the tray, sending it and everything on it clattering down the stone steps. Every piece of crockery was broken.

(#ulink_c8670b06-9e39-545b-a814-c040f9d99c57)

Emily enjoyed her visit to the butcher’s with Rosie. The early drizzle had lifted; the day was blue and sharp. Already the street sellers were singing out their wares: “Fresh watercress!” “Nutmeg graters!” “Pies, all ’ot!” “Muffins and coffee!” Street boys held out their hands: “Spend a penny on a poor boy! No Ma, no Pa! No nuffin’!” Rosie hurried past them all, intent on reaching her favourite butcher’s shop before the best cuts of meat had gone. As they drew near the shops, the streets became muddier, churned up by the wheels of carriages and donkey carts. Little sweepers ran in front of the wealthier looking shoppers to clear a path for them through the muck. They didn’t bother with Rosie and Emily; they knew they wouldn’t be getting any coins from them. Now Emily could see that the gutters were running red with blood. A woman walked past them, bent almost double with a whole sheep slung across her shoulders, heading for the row of butchers’ shops. Carcasses of meat hung from the rafters of the shop awnings. The owners, all dressed in butcher’s blue, stood outside, shouting out to people to come and buy from “Me, the best butcher in the whole of London town!”

Rosie led the way to the last shop in the row, where the walls were covered in shiny white and blue tiles. Inside, a whistling boy swept the floor clean of blood drips and slopped pieces of fat and bone. Hungry dogs scavenged under the trestles that had been pulled out in front of the shop, and were kicked away by the butcher’s hefty boot.

The butcher knew Rosie well, and joked and bartered with her as she talked Emily through the best cuts to buy. He parcelled her purchases up with paper and put them into her basket. “It’s people like you who make me a poor man!” he grumbled, as she handed over the coins. “Don’t let anyone know I’m selling you meat at this price!”

She turned away, pink-faced and smiling. “He knows I was in the trade myself once,” she said to Emily. “Selling whelks and stuff for my granddad. He was so pleased when he heard I’d got a job for his lordship that he gave me a bag of stewing meat for nothing! We’ll just get some nice fresh veg now, and we’ll have just about done. Back to our baking, Em’ly!”

They hurried on to another stall and chose the vegetables to go with his lordship’s dinner. Emily looked longingly at a nearby pedlar’s tray of dangling coloured ribbons. I wish I could buy a lovely red one for Lizzie, she thought. One day, when I get some wages, I’ll buy her one. She lifted a strand between her fingers, loving its silkiness and its intense colour of summer poppies.

“Don’t daydream, Em’ly,” Rosie said. “There’s never time for that. Judd will be waiting for me to hand back her purse so she can count out her change. I have to account for every farthing spent, so don’t go mooning over bits of ribbon.”

“It wasn’t for me,” Emily said. “For Lizzie. Or Ma.” Her voice trembled. She ached when she thought about Ma, all her prettiness gone, thin as a helpless bird that had forgotten how to fly. Be safe, Ma!

As soon as they arrived back at the Big House and hung up their cloaks behind the door, Judd flounced downstairs with the Lazy Cat to inspect the meat. She nodded to show she was satisfied, then tipped out the contents of the purse and counted the coins. “You got a bargain,” she muttered. “You shop better than you cook, I’ll say that for you. Now, before you start the meal, I want logs chopping and more coal fetching to the upstairs fires. The chimney’s drawing fast today. We don’t need a kitchen girl, Rosie Trilling, we need a fine strong boy. I keep telling Mr Whittle that, but he doesn’t want to be told how to spend his money.”

Emily’s hopes fell. “I can chop wood,” she offered, but Judd just snorted. “You’re little more than a twig yourself. Rosie’s the strong one. She can chop, you can carry, and I want it done now. What happened to the other child?”

And it was at that very moment that Lizzie had dropped the breakfast tray down the stairs. The clatter of china splintering from step to step made all three of them jump like rabbits. Judd pulled open the kitchen door to find a heap of broken china, gobs of butter and cutlery on the bottom step and a heap of crying child on the top one. The Lazy Cat stood behind her, smirking with delight.

“Rosie Trilling, you will pay for the breakages out of your wages,” Judd said, very quietly. “And make no mistake about it, these Jarvis girls will have to go.”

She lifted her black skirt clear of the mess of broken breakfast remains and swept on up the stairs, followed by her grinning niece. They stepped over Lizzie without even looking at her.

“Come on down,” Emily called up to her sister. “I’ll sweep up the bits. Come on down, Lizzie.”

Lizzie crept down the stairs, hiccupping. She wouldn’t look at Rosie. She wouldn’t look at Emily, who was still flushed and bright from her visit to the butcher’s. She had let them both down. She had let Ma down. She ran past them both and opened the kitchen door into the fluster of the hen yard. The back gate was open ready for a delivery of milk. She ran up the steps and into the road and, blind with tears, straight across the path of the milk cart. The horse reared up in fright, and the woman driving the cart was nearly tipped sideways onto the muddy street.

“Stupid girl! Stupid child!” the woman shouted. “You nearly killed Lame Betsy! And my horse! You nearly lost me all my milk!”

Lizzie ran on till she came to a row of black railings and clung to it, exhausted and frightened. Behind her, she heard a bird singing in a cage. She remembered now pausing in that very place with Emily and Ma and Jim on their way to the Big House. Was that only yesterday? Ma had told them she was taking them to the only friend she had in the world, to ask for help. She had asked them to be good and they had promised her they would. And what had Lizzie done? She had broken china that Rosie would have to pay for, and she had nearly killed the milk woman.

She sank down and curled herself up with her arms round her knees, not knowing what on earth to do next. Maybe she should find her way to the workhouse, and ask to be taken in. Everybody said it was a terrible place, and that there was no hope left for anyone who went there. But what if Ma had been taken there with Jim? She might find them there, be able to stay with them. Surely that would make it bearable, if they were there. And if she wasn’t at the Big House being a nuisance, Judd might take pity on Emily and let her stay on and help Rosie, and everybody would be happy. How would she get there, and was there more than one? She had no idea. If she stayed here long enough, someone might scoop her up and take her to the workhouse anyway. Or if they didn’t, she could beg. She watched a filthy, ragged boy approach a woman, hold out his hand to her, then touch his mouth to show her he was starving. The woman walked past him as if she couldn’t see him.

I still haven’t had my breakfast yet, Lizzie thought. But I’m not starving, not like him. Not yet. What must it be like to be like him, to have nobody to look after you, no mother or father, nobody? Nowhere to live? And the streets are full of starving children, that’s what people say. Like vermin, they are. Rats.

She sank her head into her arms. She could hear the whinnying of passing horses, the clop and clap of their hooves. London was busy around her, everyone was going somewhere, but she had nowhere to go. Then she heard a woman’s voice, shouting, “Girl! Girl! You!” She looked up, and there was Lame Betsy the milk woman limping across the road, waving her arms to force the carriages to make way for her. She wore a large black boot on one foot, and a much smaller one on the other, and as she walked she dragged the muck of the road behind her with her lame foot. Lizzie scrambled up to dart away, but Lame Betsy grabbed her by the shoulders and forced her to sit down again on the low wall in front of the railings. Then, with a huge harrumphing effort, she sat herself down next to her.

She let her wheezing breath steady a bit, still holding tight to Lizzie’s arm to stop her from running off. “I want to know,” she said, “why a young girl like you was dashing across the road like that as if she had no eyes to see with and no ears to hear with.” She glared at Lizzie. “Seems to me like you’re in trouble. Is that right? Really big trouble.”

“I am. I broke two cups and saucers, and two tea plates and a teapot.”

The milk woman let out a sigh like the blurt a horse makes through its nostrils. “And that’s enough to make you nearly kill Lame Betsy, is it? And her horse, and yourself? Is it?”

Lizzie shrugged. She thought it probably wasn’t.

“So is you running away because you’s frightened?”

Lizzie bit her lip. Yes, she had been frightened of the two Dearies. She was frightened of Judd. She had been terribly frightened when she had dropped the tray down the stairs; she could still hear the echoing shriek and clatter it had made, the terrifying din of shame. But that wasn’t everything she was frightened of, and she couldn’t find the words to tell Lame Betsy any of it, so she shook her head.

“Let me tell you something. You only run away when things are so bad that you can’t go on living in that place no more. I should know. When I was your age I ran away from a dad what beat me, and a ma what drank herself senseless. Is it that bad for you?”

Lizzie shook her head.

“And if you go back to that place, is there no one there what’d be glad to see you? Cos if you just glance over the road, you’ll see two people coming along what seems to be looking for someone. There’s a cook from a big house who I just happens to know is the kindest person on God’s earth, and she’s got a person with her who’s pretty enough to be your own sister.” Lame Betsy let go of Lizzie’s arm. “You’ve got a choice, girl. You can carry on running, or you can go and tell them you’re sorry for what you did.” She grabbed a railing and hoisted herself up. “Me, I’ve got to go and find Albert before he trots home all by himself with no milk delivered.”

(#ulink_234cc892-7c7d-58f3-b884-56c79d4fc162)

As soon as Lizzie stood up, Emily spotted her across the traffic of wagons and horses. “She’s there, Rosie! She’s safe!”

They threaded their way across the road and Emily hugged her sister as if she hadn’t seen her for a week; tight, tight, just as Ma used to do. “Never do that again,” she whispered. “Never run off without me, Lizzie.”

“My word, you gave us a fright. We thought you was lost for good. London is like a maze, girl. We could have been looking for hours,” Rosie said. “And, if Judd knows I’ve left the kitchen without her permission she’ll have me hung, drawn and quartered. It’s all my fault too. I should never have sent you up to the Dearies. They got you all jittery, I’ll be bound. And I should have warned you about that door. I’ve got the trick of it now, and so has Judd, but it comes shut on you like a charging bull if you don’t step out of the way quick enough.”

“But I broke all that china, and Judd said you’ve got to pay for it.”

“Poof! They never get given the best china, as Judd well knows, because they’ve got a habit of chucking it at the wall if the tea’s too hot or too cold or too weak or too strong. They must have it just right, or they just hurl it across the room! We keep a good stock in for them and we pick it up cheap in the market when we see it. Come on, girls, let’s get back, shall we?”

She hurried away, leaving Emily and Lizzie to try to keep up with her.

“What are the Dearies like, really?” Emily asked. “The dreary Dearies!”

“Ghosts and skeletons!” Lizzie giggled, making her voice wobble. “Who is it? Give me more tea. Who is it?” She skipped along, happy now. She was with Emily again, and nobody had told her off for anything. “More tea!”

Rosie turned round on her suddenly, her face snapped shut with anger. “Don’t you go making fun of the Dearies. They’re old, is all, a pair of old dears, and they can’t help that. And we’ll all be like that one day, even you, if you don’t keep barging into cart horses.”

Emily clasped Lizzie’s hand. “Don’t worry about Rosie. She’s upset,” she mouthed. “She should be busy in the kitchen by now.”

They had almost reached the Big House when a smart black and gold carriage drew up close to the main door. A liveried driver jumped down to open the carriage door, and two very tall women climbed out, dusting themselves down and complaining loudly that he had jolted them about like sacks of turnips. Two other women climbed out after them, clutching carpetbags as the driver handed them down from the back.

Rosie turned abruptly and put out her hands to stop the girls from going any further. She lowered her head. “Lor, oh lor, it’s the two mistresses. They weren’t due back till next week. Don’t look at them, whatever you do don’t let them notice you,” she hissed. “Turn round and go back. Have they gone inside yet?”

Emily risked a quick look over her shoulder. “They’re looking at us,” she whispered.

“Oh my, I could faint. I could pass out stone cold. They’ve seen me now, so I must go on as if I’ve been on an errand for Judd. That’s it. What you must do, you must carry on walking as if you don’t know me, and when the mistresses have gone in and the door’s shut behind them, run round quick and come in our door. Now scarper.”

Emily and Lizzie walked sharply away from her without looking back until they reached the corner. They paused as if they were waiting for someone, and Emily turned her head quickly towards the house. She saw Rosie walk steadily towards the women, bobbing to them as she passed, and then going down the steps to the servants’ quarters.

“Why was she so frightened?” Lizzie asked.

“I think she’s scared she might lose her job.”

“Because of us?”

Emily said nothing, just watched the trundling carts, the bustle of passers-by. The main house door closed, the driver climbed back into his seat and urged his pair of horses to walk on, and still they waited.

“I haven’t eaten anything yet,” Lizzie said.

Emily nodded. “All right. We’ll go in. It should be quite safe now.” She began to walk towards the house. “Poor Rosie. Poor Rosie. What have we done to her? If only you hadn’t run off like that, Lizzie! What were you thinking of?”

“It was because of yesterday. When Ma left us behind …”

“She had to. You know that. She had no choice.”

“Rosie said she’d speak up for you.”

“I know.”

“But she said she’d take me to her sister’s in Sunbury.”

“I know.”

They had reached the railings of the house. Six steps down, and they would reach the servants’ basement. Through the door, and they’d be in the kitchen, and Rosie would be there, and there’d be work to do. There would be no chance of a private talk.

Lizzie grabbed Emily’s arm. “You won’t let her, will you?” she blurted out. “You won’t let her take me away from you?”

“Of course I won’t.”

“Even if she gets you a job here, and you love it, and it’s Ma’s kitchen and everything? Even if Judd says you’re the very girl she wants?”

“Never,” said Emily firmly. She took both Lizzie’s hands in her own. “We’re sisters, aren’t we? Where you go, I go. I promise.”

(#ulink_37526d3d-fbf2-5436-8daf-cbeab7d13607)

The kitchen was grim with worry. The fire sulked in the grate, there was no sunlight coming through the window; even the pans had lost their sparkle. Rosie was on her hands and knees picking up the last of the shards of broken china. She hoisted herself up and handed Lizzie a small brush.

“Here, you can finish the job. And then you can soap the stairs down.”

“I haven’t eaten anything yet,” Lizzie reminded her timidly.

“Neither have I, neither has your sister. Get that job done first. Em’ly, you can be slicing up some bread and ham for us all. Forget breakfast, as we’re long past it now. I couldn’t stomach it anyway. Then we’ve got to get on with cooking that meal for supper. And there’s four more to cook for now: the Crabapple and the Crocodile and their two hoity-toities. Good job we bought plenty of meat this morning, Em’ly. And, Lizzie, when you’ve done the stairs you can take your bread and ham into the pantry. I’m sorry, but you’ll have to eat your meal in the dark. I daresay your hand can find its way to your mouth? If the mistresses come down, as well they might, I’ve got a story for them in my head. But it doesn’t include you just at the moment.”

An hour later the kitchen was oozing with the smell of juicy meat simmering in a pot over the fire. Emily was rolling pastry, in her quick, light way. She was using the wooden rolling pin that her ma would have worked with. Rosie was chopping carrots and onions. Neither of them spoke a word. Their ears were straining for the sound of Judd’s tread on the servants’ stairs; and at last it came. The door was flung open, and in she swept, with her black skirts brushing the floury tiles like a duster.

“Rosie, you are to go upstairs – now. Master and Mistress Whittle want to speak to you.”

“Yes, Judd.” Rosie put down her chopping knife and smoothed her hands clean on the apron. “Have I to take Em’ly with me?” Her breath came out like a trembling shudder.

“Certainly not. They want you on your own. They want you to explain why you have brought street children into the house.”

“Not street children, Judd. Didn’t you tell them they’re Annie’s daughters?”

“They didn’t ask me. It’s you they want to speak to.” Judd swept out of the kitchen, and the flour settled back into the cracks between the stones. Rosie said nothing. She tucked her hair under her cap, removed her working apron and slipped on a newly starched clean one and, without saying a word to Emily, followed Judd up to the main part of the house.

Emily didn’t dare to open the door to the larder to see how Lizzie was. She finished rolling the pastry, trying to keep her hands steady, trying to keep the scorch of tears from blurring her eyes. She lined a pie dish with half of the pastry and put it on the windowsill to keep cool, stirred the meat with a wooden spoon, then carried on from where Rosie had left off, chopping vegetables and herbs. Now tears coursed freely down her face, no matter how often she wiped them away.

Rosie came down at last. Her eyes were red. She put her work apron on without saying anything at all. In silence she transferred the cooked meat from the pot to the pie dish, where it bubbled in its hot gravy. She added the vegetables and herbs and nodded to Emily to roll out the rest of the pastry. She fitted it snugly over the meat, then placed it in the side oven. She raked up the fire. When she spoke at last her voice was flat and dull, and it was only to say that the mistresses would like apple dumplings for dessert, and would Emily be kind enough to show her how to make them as good as her ma did.

All this time, Lizzie was shivering in the dark and cold of the larder, but she wasn’t let out until Rosie had made several journeys upstairs with the cooked food and was quite sure that the master and his business acquaintance, and his wife and her sister, the hoity-toities in their attic room and the Dearies in their creaky bed were all tucking into the best meal they’d had for months. A cauldron of water was set above the fire to wash the dishes, and Judd and the Lazy Cat, Rosie, Lizzie and Emily sat down at the kitchen table to eat what was left. Neither Judd nor Rosie said a word.

“Oh la!” the Lazy Cat said. “Trouble!” And was shushed to silence by her aunt’s fierce look. Rosie hardly ate a thing, but kept sighing and sniffing and blowing her nose. Emily glanced at Lizzie and shrugged slightly to show her that she hadn’t a clue what was going on. She knew Rosie was in trouble, and they thought Judd was probably in trouble too. They also knew that it was all because of them.

Later, when Rosie brought all the dishes down from the various rooms of the main house, she said, simply and flatly, “They ate the lot.”

Judd and her niece went upstairs to see to the fires and warm the beds. Rosie looked at the two girls where they sat on the kitchen bench, then briefly put her arms round each of them in turn.

“What’s going to happen, Rosie?” Emily asked.

“I want you to get some sleep now. That’s what’s going to happen next.” She gave a long, deep sigh that was full of inner worry. “Like your ma asked, I’m trying to do my best for you. I’m going up to my room. Good night, girls.”

Emily and Lizzie lay wrapped in their rugs in front of the fire, watching the flicker of flames as they licked through the damped coals.

“Something bad’s going to happen, isn’t it?” Lizzie asked.

“I don’t know. Ssh now, go to sleep, like Rosie told you. Everything will be all right.”

Very soon, in spite of all their worries, the girls fell asleep.

And then, in the middle of the night, Lizzie felt herself being lifted up and carried across the room. She thought at first that it was part of a dream, until the street door was opened and a shock of cold air startled her into wakefulness. She was set down, her cloak put round her shoulders, her boots laced onto her feet and a small bundle thrust into her hands. All this was in the pitch-dark, with no words spoken. Then a hand grasped her own.

“Emily?” But she knew it wasn’t Emily’s hand; it was too large, too cold, too tight.

“Emily!”

She reached back to the door of the house just as it was closed firmly against her. She heard the key turn in the lock.

“Emily! Emily!” she screamed, and then a hand was clamped across her mouth and she was pulled away, up the steps, and out onto the street.

(#ulink_9865a368-aad2-5be0-adb9-ea1f0223fa4e)

Emily opened her eyes, startled awake. Surely she’d heard Lizzie’s voice? She felt across the hearthrug for her, then scrambled to her feet. Lizzie wasn’t there! She heard her voice again, footsteps outside, someone running, someone dragging her feet as if she was being pulled along. She groped for the door, helplessly pressing the latch, but it had been firmly locked.

“Lizzie! Lizzie!” She banged on the door with her fists. “Wait for me!”

A light flared behind her, and she turned to see a woman holding up a candle, her nightdress white as a spectre’s, her eyes deep and dark in her pale face, her cheeks high and gaunt with deep hollows. Her grey hair hung in long strands round her shoulders.

Emily screamed, and the spectre stepped forward and put a bony hand on her arm. “Hush, girl! Do you want to bring the whole household down here?”

It was Judd’s voice. Emily shuddered with relief.

“Please let me out, Judd. Something’s happened to Lizzie. I think someone’s taken her away.”

“Nothing’s happened to Lizzie,” Judd hissed. “She’s with Rosie Trilling.”

“She can’t be! Not without me!”

“Be quiet! If you must know, Rosie has given up her job. For your sake! You must stop this noise. Upstairs won’t take kindly to being woken up in the night by your ranting.”

“I don’t understand! Rosie wouldn’t leave me here. I’m not staying without Lizzie. Let me out!” But Emily could see that Judd had no keys dangling from the waist of her nightgown. Where had she hidden them? She rattled the latch again, helplessly, uselessly.

“Stop that! I think you know very well what I mean. Rosie has been dismissed, to put it plainly. Gone, gone, and taken the girl with her.”

“But where’ve they gone?”

“She’s taken Lizzie to try to get her a job in Sunbury with her own sister, and let me tell you that’s a long long walk from here, and then it’s back home for Rosie, back to an evil grandfather and a wretched life as a coster-girl.”

Judd turned to go back to bed, lifting her candle to light her way to the other door, and Emily just caught the glint of something bright in her hand. She knew it was the door key. She ran in front of the housekeeper and tried to snap the key out of her hand. Judd shouted in anger and tried to force her away, and in the tussle she dropped the candle. There came the sound of hurried footsteps on the stairs, the glow of another candle, and a tall woman came into the kitchen. Her hair hung in a long plait over her shoulder, and with one hand she clutched to her throat the ends of a black velvet shawl flung over her nightdress. With the other she held the candle high.

“What in the name of the Lord is going on here?”

Her voice made the pans vibrate on the shelves, the glasses tremble in their locked cupboard, the cutlery jitter in the drawers. Emily recognised her as the older of the two women who had stepped out of the carriage that morning: the Crabapple, mistress of the house. Dithering behind her now were two old ladies, cackling and whooping with excitement, and the Lazy Cat. Her eyes were alight with scorn. “Gone!!” she sighed.

The Crabapple turned to her. “Is this anything to do with you?”

“Not me, no, ma’am. I know nothing about it. Something about two girls who were dragged in from the streets. Friends of that Rosie Trilling. I don’t know what they were doing here in your house, ma’am.”

The Crabapple advanced towards Emily, thrusting the candle under her face. “Who are you?”

“She’s Emily Jarvis. She’s the new cook,” Judd said, bending to scoop up her candle.

“The new cook?”

“I can cook,” the Lazy Cat muttered.

Her Aunt Judd shot her a knowing glance and signalled to her to go back to her room. “Rosie Trilling has gone, like you told her to, ma’am.”

“Please don’t blame Rosie,” Emily begged. “She was trying to help me.”

“So we need a new cook,” Judd went on. “And this is her.”

“The new cook?” the Crabapple said again. “This child?”

“Please, miss, I want to go,” said Emily bravely.

“You want to go?”

“She wants to follow her sister,” Judd said with a snort, as if it was the most ridiculous idea in the world.

“Then go!” said the Crabapple. “I don’t want street girls in my house. Go.”

The two Dearies whooped gleefully. The Lazy Cat, lingering in the doorway, smiled to herself.

“Unlock the door, and let her go,” the Crabapple said to Judd. “Out, girl. Out. I’ll have no charity children here.”

Without a word, Judd stalked over to the back door and unlocked it. Emily bundled up the rug she had been sleeping on, snatched her boots, and scampered through the door, across the yard, and up the outside steps to the street.

Below her, the servants’ door was slammed shut and locked.

(#ulink_668545a2-e3bf-51ec-9cc5-47da0686a355)

Dawn was beginning to break with a grey, steely light. The street was deserted, except for the lamplighter tramping towards the main road, stretching up his long pole to extinguish the street lamps. Emily ran to him, her bare feet slapping the cold stones.

“Wait, oh wait! Please, mister, have you seen a woman and a girl coming this way?” she panted.

Saying nothing, the lamplighter just pointed to where an early mist was coiling up in smoky wreaths from the direction of the river. Emily ran on to the Thames and along the bank, calling, “Lizzie! Lizzie! Lizzie!” She had to find her. Would they have gone this way, or that? “Lizzie! Rosie!” Her voice echoed off the old boat sheds. People were beginning to move, horses were being fastened to their carts, beggars uncurling from their sleeping-holes. Costermongers trudging out of their cottages, their trays loaded with breakfast shrimps to sell to the early-morning workers; street children crept like rats out of the shadowy arches of bridges to scavenge what they could. But there was no sign of Lizzie and Rosie.

“Which way? Oh, which way?” Emily gazed round in despair.

“’Ere. You’re lost, ain’tcha?”

A boy was sitting in the gutters, with a string of shoelaces in his hand. He was dressed in the tattered clothes of a street child, barefoot and dirty, with tangled hair.

“Don’t know yer way back home? Cos like, I know these streets inside out and upside down, I do, and I can take you anywhere you wants to go, and maybe your ma and pa would give me a penny or a farving for finding you, or maybe not, I don’t care.” He grinned up at her. “Why don’t you sit down for half a minute and catch your breff, and have a little fink?”

She shook her head, though she was exhausted with running so far. She didn’t have time to take a rest. Rosie was a quick walker. They could be anywhere by now. “I’m looking for my sister,” she said. “And my friend Rosie. You haven’t seen them, have you?”

The boy frowned. “Not seen no one this morning of the female kind, ’cept for Raggedy Annie and the like. Seen a lot of dogs. There was an old man as wouldn’t buy me laces, even though his own was frayed like pieces of old straw. Too mean, he was, and when he trips over he’ll remember me and fink, I wish I’d helped that boy out. But I ain’t noticed anyone else this morning. Why don’t yer go back home? Maybe they’ll be there, waiting for you.”

Emily shook her head, too upset to speak now. She turned away from him and began to trudge back the way she had just come. She hadn’t got a home, not any more. Even if she found her way back to the Big House, she couldn’t go inside. She didn’t belong there now. She didn’t belong anywhere. She felt a surge of panic. What if she didn’t find them? What on earth would she do?

“Any idea where they was heading?” the boy called after her.

She stopped. “Yes!” Why hadn’t she thought of that? She tried to force the word out of the back of her memory. Somewhere that made her think of sunshine. “Sunbury! They were going to Sunbury!”

He whistled softly. “That’s out of my patch, that is. Cor, it’s miles and miles away! Tell you what. You’ll have to get onto one of the main roads and ask the coachmen there. Go along there to that big church and then you’ll find some coaches. Maybe they’ve took one, cos they won’t be walking that far I don’t fink.”

“They won’t be on a coach,” Emily said sadly.

The boy whistled again. “No money, eh? There’s only two choices for people wiv no money. The streets, or the workhouse up that lane, and I know which one I choose. I’ve been there, I have, and I got out again as quick as a cat. Never go there again, I won’t.”

Emily started running again. Her head was thudding. She’d wasted too much time; she shouldn’t have stopped. She must have really lost them by now. Ahead of her she saw the church. She could just make out a line of coaches where someone might tell her the way to Sunbury. Sunbury – the long, long walk. Could Lizzie manage it? But what were the other choices? The streets, and a life of begging and stealing and sleeping under bridges. Would Rosie let that happen? The workhouse. No, no, not the workhouse. Surely they wouldn’t go to the workhouse. But Ma might be there. Jim might be there. She stood at the end of the lane that the boy had pointed to. At the far end, she could see a tall building with black gates. No. They wouldn’t go there. Never.

(#ulink_0ffda597-3876-54a4-932d-405256524a28)

Rosie and Lizzie had stopped running by now. They were well away from the Big House, and Rosie knew that Lizzie would never find her way back there on her own. She drew her under a bridge to rest a little, and let go of her grasp. Gulls screeched mournfully, the tide was out, the riverbanks were a stinking mess of mud and fish bones and rubbish. Further down the river they could see a huddle of fishermen’s cottages, clustered together like a mouthful of rotting teeth.

“That’s where I come from,” said Rosie. “That’s where I was born. Went up in the world, I did, thanks to your ma.” And now it looks as if I’m sunk back down, just like that, she thought to herself.

Lizzie thought the cottages looked even worse than Mr Spink’s tenement house where she used to live with Ma and Emily and Jim. How long ago was that? Only three days? And where was Ma now? Where was Jim?

“Is that where you’re taking me?”

“Oh no. My granddad would eat you up. Like a snappy dog, he is. He’s wicked. I wouldn’t take you there. No, Lizzie, we’re going to Sunbury.”

“I want to go back to Emily. Back to the Big House.”

“Well, you can’t,” Rosie said firmly. “We’ve been kicked out. There, now you know, and I wasn’t going to tell you that. We’ve got to go to Sunbury, or starve, and that’s the truth. It’s our only hope now. My sister might speak for us. We’ll be all right there, maybe. But we’re going to be walking till our legs drop off, so best get a move on. Up that lane now.”

It was beginning to drizzle with a sharp, frosty sleet. Rosie stopped to pull her shawl up over her head. I wish I was back in that big warm kitchen, she thought. The job of my dreams, that was, working there. Never again, Rosie. Not for you.

“What’s that big building up there, with the black railings?” Lizzie asked. She had a feeling that she knew very well what it was, that it had been pointed out to her in the past as a house to be afraid of, a last-place-in-the-world sort of house, more frightening even than a graveyard.

“It’s the workhouse,” Rosie said. She tugged Lizzie’s arm, anxious to hurry past the place, but Lizzie pulled herself away from her.

“I want to go there. If I can’t go back to the Big House, I want to go there.”

“Not there! I won’t let you.”

“But Ma might be there. And Jim. I want to be with them.” Lizzie was already running up the middle of the slippery road, and all Rosie could do was to lift her skirts out of the muck and run after her. Maybe, she thought fleetingly, it would be for the best. In her heart of hearts she knew that her sister would never be able to find work for both of them, probably not even for one of them. At least if Lizzie was in the workhouse she would have food of sorts, and a roof over her head. She wouldn’t be sleeping on the streets like the other homeless children. But the nearer she drew to the huge iron gates that kept the inmates of the workhouse away from the rest of the world, the more her dread and fear of the place grew.

Never, she thought. I’ll never let Annie’s child go there.

Lizzie had nearly reached the railings when she saw a group of children being herded out of the door into the workhouse yard. A boy ran ahead of the others and stood clutching the railings with both hands, his white face peering out through the bars.

“Jim! It’s Jim!” Lizzie yelled, slipping down on the greasy cobbles in her eagerness to get to him. But when the boy turned his head to look at her she could see that it wasn’t her brother at all. He stuck his hand through the bars.

“Got any bread, miss? Got some cheese?”

“Do you know Jim Jarvis?” Lizzie asked him. “Did a boy come here with his mother, and she was sick and weak and he probably had to help her to walk – did you see them?”

The boy looked puzzled. “A boy and his ma?”

“Did you see them? She’s Mrs Jarvis. Annie.” Lizzie looked over her shoulder anxiously. Rosie had nearly reached her. “He’s called Jim. He’s my brother.”

“Jim Jarvis?” the boy repeated. “Jim Jarvis and his ma?” As if it was part of a nursery rhyme that he was trying to remember.

As soon as Rosie reached them she fumbled in her bag and brought out a hunk of cold pastry that she had saved from last night’s supper. It was meant to keep them going on their long walk to Sunbury. She held it out towards the boy and as she did so, she shook her head very slightly, and narrowed her eyes, and made her mouth into the silent shape of “no”.

“No,” said the boy quickly. “No Jim Jarvis here.” He snatched the crust and ran to join the other children who were being hustled towards the gates by the ancient workhouse porter.

“Stand ’ere and wait till the coach comes,” the old man was saying to them. “And thank the Lord you’re going to a better life. Is that Tip?” he shouted to the boy. “What you eating? Been beggin’, ’ave yer?” He grabbed the boy and dragged him away. “You ’eard what Mr Sissons said! Wait nice and quiet till Mrs Cleggins comes. No begging, no annoying, be’ave like a gentleman! Lost yer chance now, you fool.” And he dragged Tip back inside the workhouse building. The other children clustered together, giggling nervously. A tall, handsome boy grinned and raised his hand as if he was saluting as a smart carriage drew up to the gates. The waiting children cheered and surged forward.

“There you are,” said Rosie. “They’re not there, and nor will you be. It’s no place to live or die, I can tell you that.”

“No, it’s not,” Lizzie agreed. She looked at the grim, soot-blackened building and shuddered, and then turned her back on it. “I don’t want to go there. Not if Jim and Ma aren’t there. Not ever.”

“Lizzie!” a familiar voice shouted. “I’m here! I’m here!”

But it wasn’t Jim’s voice, or Ma’s. It was Emily, running up the lane from the river. “Don’t go without me!”

“Oh lor!” sighed Rosie. “Two of them now!”

“I told you I wouldn’t let you go,” Emily gasped, panting up to them. “I ran and ran, and I didn’t know where to look for you, and then I thought, the workhouse, that’s where they’ll be, and I was right.”

“Don’t tell me you’ve quit that good job,” Rosie said. “Now what?”

“I don’t care what happens now,” Emily said. “As long as I’m with Lizzie.”

“Are these girls for me?” a sharp voice called. Rosie looked round to see that a hefty, ruddy-faced woman was leaning out of the carriage window. “Homeless girls?”

“I suppose they are,” Rosie sighed. “Why do you want to know?”

“Because I’m looking for a pair of strong, healthy girls just like these two.” The woman had a strange, flat accent that was a bit difficult to understand. Lizzie watched her, fascinated, and the woman caught her eye. Her mouth twitched into a grim sort of smile that showed her brown teeth. “Got their papers? Indentures?”

A wagon drew up behind the carriage. “Get in, children,” the woman shouted to the waiting huddle, and with great excitement the children from the workhouse all climbed in.

“And you two.” The woman nodded to Emily and Lizzie. “You can send their papers on. I’m in a hurry.”

“Wait a minute,” Rosie said. “Who are you? Where are you taking these children?”

“I’m Mrs Cleggins,” the teeth clacked. “Of Bleakdale Mill. I’m here to collect homeless children, good homeless children, from workhouses and streets. I look after them, poor little mites. I give them a future! I have plenty of work for them.”

“What kind of work?” Rosie asked suspiciously. But her heart was beginning to lift.

“They’ll be apprentices. Out of kindness of his heart, Mr Blackthorn gives apprenticeships to poor and needy children They’re all going to learn to be textile workers. He gives them a new life! You’re very lucky, I’ve got room for these two today. I think in the circumstances and out of charity Mr Blackthorn will overlook the lack of proper documents. I were promised ten lads and ten lasses from this workhouse, but looks like there’s only eight lasses here.” She clacked her teeth together impatiently, then added as an afterthought, “Probably too sick or died, poor creatures. A life in country might have saved them. Don’t tell me you don’t want these lasses to come!”

“I don’t know,” Rosie said doubtfully. “I promised their mother I’d look after them.”

“Well, they’d have a lovely life with me. Fresh country air, good country food, and a job for life. Make your mind up, I can’t dally all day.”

“They’d get a wage, would they?”

“Naturally. And clean clothes. Oh, put them inside wagon. They’re hardly dressed for this rain. I cannot bear to see them shivering like that.”

“I don’t know what to say.” Rosie turned away. “What do you think, girls?”

Emily sensed the despair in Rosie’s voice. “Maybe we could go there just for a bit, Lizzie, till Rosie finds somewhere for us all to live.”

“Would it be like when we used to live in the cottage, before Pa died?” Lizzie asked. “Would we have a cow and a pig?”

“I think your lasses want to come,” Mrs Cleggins said.

“Do you really?” Rosie asked them. Her heart was fluttering. I’ve no job, I’ve no home, I’ve nothing to give them, she thought. What right do I have to deny them a promising future like this?

“It’s not fair to expect Rosie to look after us both,” Emily whispered to Lizzie. She squeezed her sister’s hand. “We’ll try it,” she said.

Rosie made a choking sound like a strangled cough in her throat. She fumbled inside the bundle she was carrying and thrust something towards Lizzie. “Here, I made this rag doll for my sister’s child. Have it, to remember me. God bless you both.”

She hugged them quickly and then hurried away so she didn’t have to watch them clambering into the wagon. She heard the doors being slammed shut behind them, heard the driver yelling coarsely to the horses to “Gerra move on, will yer!” and the snort and rumble as the carriage and wagon moved away. She turned then, one hand lifted in a wave of farewell, the other clasped to her mouth.

“There you are, Annie. I’ve done my best for your girls. Just like I promised.”

(#ulink_a6a05736-eaf4-5501-848b-c51b0988e5f4)

It was dark in the wagon now the doors were closed, with just a piercing of daylight where ropes had been slashed into the canvas to make a roof. The floor was covered with straw, which the workhouse children were flinging about excitedly.

“We’ll have our own horses to ride!” A girl about Lizzie’s age draped a mane of straw across her bubbly curls. “Neigh! Neigh!”

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/berlie-doherty/far-from-home-the-sisters-of-street-child/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Berlie Doherty

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Книги для детей

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 25.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The sisters of STREET CHILD tell their story…A companion novel to bestselling story of Victorian orphan Jim Jarvis based on the founding of Dr Barnardo’s homes for children.When Jim Jarvis is separated from his sisters, Lizzie and Emily, he thinks he will never see them again. Now for the first time, the bestselling author of STREET CHILD reveals what happened to his orphaned sisters.In Victorian London, Lizzie and Emily are left in the care of a cook but their story takes them to the mills of northern England. There, under the keen eyes of the mill owners, the girls are made to work in harsh conditions and any chance of escape is sorely tempting…An incredible new STREET CHILD story based on the true experiences of Victorian mill girls.