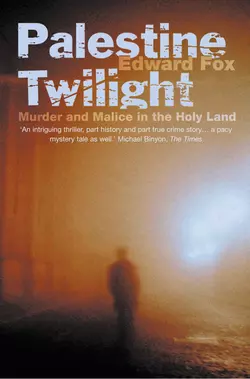

Palestine Twilight: The Murder of Dr Glock and the Archaeology of the Holy Land

Edward Fox

Please note that this edition does not include illustrations.Part travelogue, part true-thriller, Edward Fox’s brilliantly original book investigates the murder of a US archaeologist on the West Bank in 1992 and opens up the Palestinian world he served – a Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil of Palestine and the West Bank.On 19 January 1992, Dr Albert Glock – US citizen, archaeologist and Director of Archaeology at Bir Zeit University in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, was murdered by an assassin. Two bullets to the heart. The witness statements were confused, the autopsy inadequate. The police took three hours to arrive at the scene, from their HQ ten minutes away.Who killed Albert Glock? The Palestinians blamed the Israelis, the Israelis blamed an inter-departmental feud at the university, or extreme Palestinian groups. But those close to Bir Zeit, to the political situation on the West Bank, had a simple line of advice: 'Look to the archaeology,' they repeated. 'Look to the archaeology.'For Albert Glock had started to uncover truths about the distant Palestinian past which Israel found uncomfortable. For Israel, Palestine was a country without a people – for a people without a country. Now Glock, through his archaeological finds, was showing that their version was flawed. He was publishing papers about the ancient traditions and settlements throughout Palestine, and discovering hugely significant facts about the ancient Palestinian way of life. Glock had given up a glittering career to teach at Palestine's beleaguered, besieged and underfunded university which faced closure at worst, and curfew at best – daily.Edward Fox's extraordinary book weaves together the story of Glock's murder with the history of biblical archaeology and the brutal, Byzantine politics of the intifada. It is written as a true-life thriller which opens up the Palestine in which Glock lived and worked, the people he knew and the turbulent politics of the middle east. This is brilliantly original writing and compelling storytelling quite unlike any other work yet published on the Middle East.

PALESTINE TWILIGHT

The Murder of Dr Albert Glock and theArchaeology of the Holy Land

EDWARD FOX

To Emma

CONTENTS

Cover (#ubf79d85c-5f54-5cbd-8f75-435928d78bd3)

Title Page (#u06710361-d076-52e4-bb0a-28a68bdf9df1)

Dedication (#u8cd7b4ff-0535-51dc-b737-3e08e47eab14)

A Note on the Names of People and Places (#u3c8425a3-fb7e-5572-a685-adaf145fdcdc)

PART I That Day (#u00e1c362-d148-52b3-963e-672c9231a794)

One (#u5a49093e-cd6c-5c12-9029-92b75dc53161)

PART II The Archaeology of Archaeology (#uc03fc3c4-1589-57ae-80d1-2ee1eafd68ff)

Two (#uefc4ce67-3635-5d5c-b48f-eddac62e962e)

Three (#u08fa44c0-153f-5578-9e19-2f438c62e1eb)

Four (#ud225a35f-5b54-51e5-8fc0-8e2c5822dcbb)

Five (#u6aa3f052-347f-5c72-9607-099ee7cf4f23)

Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

PART III Destruction Level (#litres_trial_promo)

Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Glossary (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes on Sources (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

A NOTE ON THE NAMES OF PEOPLE AND PLACES (#ulink_a901b758-a21e-5f80-91ba-f2194423310a)

I have changed the names of some of the people involved in this story in an attempt to defend their privacy. I have not changed the names of political figures and of people serving in governments.

As for place names, I use the name Palestine in this book at first as a geographical term denoting the area of the Levant or southern Syria that includes what is now the State of Israel and the Occupied Territories, which extends from the Jordan river to the Mediterranean, and from Lebanon in the north to the Negev desert in the south. This is the sense intended when dealing with the history and archaeology of the country. Later, particularly where I follow Albert Glock’s life and work among the Palestinians, the name Palestine is often used as it would be understood in the Palestinian Arab context in which Albert Glock had immersed himself; that is, in a political sense, meaning the Palestinian nation in Palestine.

Bir Zeit – written as two words – is the name of the town in which Birzeit (written in English as one word) University is situated.

PART I That Day (#ulink_1245f448-8021-55c2-8e49-6d190fe80c2a)

ONE (#ulink_b343ae2e-5a65-58c6-98a1-0636f38f49a3)

ON THE MORNING of Sunday 19 January 1992, the day he was to be murdered, Dr Albert Glock went to church with his wife in the Old City of Jerusalem. Albert Glock was an archaeologist, and the Director of the Institute of Palestinian Archaeology at Birzeit University, the main Palestinian university in the Israeli-occupied West Bank. The church he attended, the Church of the Redeemer, was a sombre nineteenth-century Crusader pastiche, one of a number of religious institutions clustered tightly around the Holy Sepulchre, the lugubrious and claustrophobic Christian shrine that is traditionally believed to contain the tomb of Jesus Christ and the site of his crucifixion.

He left the service after the Eucharist; his wife Lois stayed to the end: he wanted to get back to his office at Bir Zeit to work on pottery. He walked through Damascus Gate, the monumental, grimy Ottoman construction at the corner of the Old City where the world of Palestinian Jerusalem rubs uncomfortably against the world of Israeli Jerusalem, where Palestinian women in embroidered dresses sell fruit and vegetables on the busy pavements, and where minibuses and shared taxis depart for the towns and villages and refugee camps of the West Bank. Grey winter clouds clogged the sky, but despite the weather Glock had on only his well-worn black leather jacket. At about 10.30 a.m., he climbed into his blue Volkswagen van and drove northwards out of Jerusalem in the direction of Ramallah, passing first through Bayt Hanina, the Palestinian village that had been absorbed into the northern suburbs of Jerusalem where he and Lois lived. He bought an Arabic newspaper, and then stopped at a local bakery and bought a ka’ak simsim, a ring of pastry filled with dates and sprinkled with sesame seeds.

The checkpoint separating Jerusalem from the West Bank – a roadblock made from slabs of painted concrete, with a small cabin beside it occupied by Israeli soldiers – was open, so Glock was able to cover the distance from Jerusalem to Ramallah in about half an hour. He drove northwards through Ramallah, past the British-built prison inherited by the Israelis, along the road called Radio Boulevard, named after the array of three radio transmission masts built alongside it, also relics of the period of British rule that ended in 1948.

Glock stopped again before he reached Bir Zeit, at a house on the outskirts of Ramallah, near the radio transmitters, where the road was muddy and gouged with ice-filled potholes. This was the house of Dr Gabi Baramki, the acting President of Birzeit, and his wife Dr Haifa Baramki, the university’s Registrar. Nearly thirty years after first coming to Palestine, Glock still thought that it was an Arab custom not to make appointments, and Palestinian courtesy had restrained anyone from telling him this was not the case. When Haifa Baramki answered the doorbell and saw Glock in the doorway, she was not expecting to see him, but she was not surprised either.

Haifa told him that Gabi was not at home, but invited him in for coffee. Glock declined, but said he would return after he had finished working at the Institute. He would come back at about four, he said. He wanted to discuss the allocation of teaching assignments at the Institute. Gabi Baramki and Glock were close friends, and allies in Birzeit’s overheated academic politics. The conversation would undoubtedly touch on the problem that had been simmering in the Institute since the summer: Glock had turned down for a teaching job one of his longest-serving graduate students, who had reacted by waging a noisy, bitter and very public campaign to overturn the decision.

Before he left, Haifa Baramki asked him if he planned to stop at the house of the al-Farabi family in Bir Zeit. If he did, she asked, he might remind Maya al-Farabi, who was Glock’s teaching assistant at the Institute, to attend a meeting the next day of a professional women’s group at Birzeit to which they both belonged. The al-Farabis did not have a telephone, and Haifa knew that Glock was a regular visitor to the house. This was an errand that Glock would have been happy to undertake. Indeed, he was probably intending to stop there anyway. Maya al-Farabi was Glock’s closest colleague at the Institute of Archaeology, and his favoured successor as Director. He had guided and nurtured her academic career every step of the way, from undergraduate to PhD, and had done the same for her younger sister, Huda. If Glock trusted anyone to take over his position as Director of the Institute, it was Maya al-Farabi. On working days, Glock would often have lunch at the al-Farabi house. As a sign of affectionate familiarity, they gave him a traditional Arabic nickname, Abu Abed. This meant ‘father of Albert’, which was also the name of Glock’s eldest son.

By now it was between eleven o’clock and noon. Glock drove out of Ramallah and down into a valley where a bypass to an Israeli settlement crossed the road to Bir Zeit. Here there was usually an Israeli checkpoint, with a jeep, a strip of spiked chain across the road, and some surly young soldiers with machine guns slung over their shoulders stopping vehicles and checking identity cards. Glock was slyly proud of his skill at talking his way past these obstacles. Palestinian friends would marvel at how he managed to appear at their door on days when the tightest closures were in place, when no one was able to travel anywhere. He took full advantage of his appearance as a serious-looking, elderly foreigner. He was even careful to establish discreet but cordial relations with the few Israeli soldiers he saw more than once at the checkpoints, chatting with them, aware of their boredom. If this made it easier to go about his business he was willing to do it, though he was careful not to seem too friendly with the soldiers when he had a Palestinian passenger sitting beside him.

Covering the distance from Ramallah to Bir Zeit took about fifteen minutes. The road winds around rocky, rubbly hills, and through a few villages. Just outside Bir Zeit, he drove past the new campus, built in 1980, and now closed by military order, a limestone quarry at the side of the road, and the houses on the outskirts of the town, including the al-Farabi house. He knew that Maya had a dentist’s appointment in Ramallah that day, and he assumed that she would be back home by the time he finished work at the Institute. He drove through the compact town, whose position on a ridge gave it a grand view of the valley below, with tiers of crumbling olive terraces, some in use, some not, descending to a narrow plain where, according to local legend, the Roman general Titus encamped with his army in the year 70 before marching on Jerusalem to besiege it. From this road you could look down into the valley and across towards Ramallah, at the blinking lights of the radio masts, and on the top of a distant ridge, the Israeli settlement of Beit El, site of the region’s military headquarters, built on the traditional site of the biblical Bethel. On the slope below it one could see the Palestinian refugee camp of Jalazun. At night, these two enemy settlements, irreconcilable worlds of victor and vanquished, were visible only as streaks of light, the upper one brilliant white, the lower one yellow. When a power cut cast Bir Zeit and the surrounding area into darkness, Jalazun would seem to disappear, while Beit El, with its own source of power, blazed on.

This winter had been the coldest anyone could remember. There had been heavy snow, which stayed frozen on the ground for days. The snow brought down telephone lines and power cables, cutting off electricity and telephones, and the ice caused water pipes to burst. The people of Bir Zeit had endured long, bleak spells without electricity, telephone and water. In the narrow, layered terraces of rocky soil sculpted into the slopes, the cold froze and killed thousands of olive trees.

The olive tree is the emblem of Birzeit University, which is the main university in the Occupied Territories of Palestine. It is a good symbol for an institution that prides itself on being the hearth of Palestinian nationalism. The olive tree embodies the virtues that Palestinians like to see in themselves: it is ancient, it is tough, it is native, and it has deep roots. The name Bir Zeit means reservoir of oil. In the academic calendar of Birzeit University, a day is added to a weekend in the middle of October, and this three-day break is observed as Olive-picking Holiday. The idea is that, on this weekend, students return to their homes to help with the olive harvest. In reality, the Olive-picking Holiday is a political and nostalgic gesture rather than a matter of agricultural necessity. Few Palestinians any more have olive groves big enough to produce an economically viable crop.

In January 1992, Albert Glock was sixty-seven years old, and in his slow, perfectionist way was getting ready for retirement. He and Lois had been expatriates for so long, and were so deeply immersed in life among the Palestinians, that Glock felt he could never live in the United States again. For many years they had lived in a large, comfortable rented house in Bayt Hanina on the main Jerusalem road, with big airy rooms and a study full of the books and artefacts that Albert had accumulated over the years: everything they had was there, materially and spiritually. Now, on the verge of retirement, they were preparing to move to a smaller house in the same neighbourhood. The American way of life, a condition of comfortable ignorance of the rest of the world, as he saw it, had become foreign to Albert Glock. He called it ‘living in the bubble’. He had been visiting Cyprus now and then on the three-monthly trips out of the country he was compelled to make to renew his Israeli visa, and favoured settling there, but he had done nothing about it. This academic year he had relinquished most of his teaching responsibilities so that he could concentrate on completing the long-delayed publication of his life’s work, the excavation of an archaeologically complex site in the northern West Bank called Ti’innik.

The Institute of Archaeology was accommodated in an old-fashioned family house with two storeys, built around a central courtyard that was entered by an ornamental iron gate. It stood on the edge of Bir Zeit’s old town, a tight maze of dilapidated Ottoman buildings. To the right of the Institute, a car mechanic worked out of a dark cave of a workshop that had formerly been a blacksmith’s shop. Down a narrow lane, among the tiny houses, there was a bakery where traditional flat bread was baked in a dome-shaped oven, and a small Greek Orthodox church in a poor state of repair.

Glock worked alone that day. The shelves in his workroom were filled from floor to ceiling with the cardboard boxes, neatly marked, that contained the excavation material from his digs at Ti’innik and Jenin. The work tables in the room were covered with hundreds of blackened shards of burnt pottery, arranged in a state somewhere between order and chaos. The fragments were from Ti’innik, and Glock was working with Maya and a staff technician on the painstaking business of putting as many of the fragments as possible back together into their original forms as domestic pottery vessels. The pots bore a mysterious pattern of ridges that they could not identify. Several vessels had already been reassembled, among them a big two-handled water jar that dominated the room.

Ti’innik is a hamlet in the northernmost part of the West Bank, a few kilometres north of the town of Jenin in the flat, green Jezreel valley, near the biblical site of Megiddo, better known as Armageddon, where the Book of Revelation prophesies that the battle to end all earthly battles will be fought. The village stands at the foot of an ancient man-made mound called Tell Ti’innik, which is almost certainly the site mentioned in the Bible as the Canaanite stronghold of Taanach. In 1987, Glock and Maya al-Farabi took the radical step of excavating, not the parts of the site that relate to biblical history, which had been the dominant interest of the archaeology of Palestine since archaeology began in the Holy Land in the middle of the nineteenth century, but the more recent Ottoman remains which had been largely ignored by archaeologists.

Some time before three o’clock, he closed up the office and turned the key in the VW. He aimed to stop off briefly at the al-Farabi house to leave the message for Maya about her meeting. He would not stay long: his appointment with Gabi Baramki was more important. Before he left, he scribbled a note to Maya on the copy of the Arabic newspaper he had bought in Bayt Hanina, that day’s edition of al-Ittihad. He wrote across the top in block capitals, ‘I may be late tomorrow. Al,’ and left it where she would see it.

That day, a funeral was taking place at the Greek Orthodox church. The town of Bir Zeit is unusual among West Bank towns in that its population is mostly Christian, and unlike better-known Palestinian towns that have traditionally had Christian majorities, such as Bethlehem, the proportion of its population that is Christian has increased rather than shrunk in recent years. The thresholds of the doorways of houses tend to be decorated with a carved relief of St George slaying the Dragon (a motif thought to originate with the Crusades), indicating a Christian household, rather than a Qur’anic inscription. Most of the Christians in Bir Zeit, in common with most Palestinian Christians, belonged to the Greek Orthodox Church. As Glock was leaving the Institute, the funeral procession, with its train of cars, came along the narrow road toward the church in the opposite direction. People in Bir Zeit remember that Glock patiently pulled over to the side of the road to let it pass. His VW van was a familiar sight in the area, and everyone knew it belonged to the American archaeologist. They remember that moment as a characteristically modest, thoughtful act of courtesy. They also remember it as the last time many of them saw him alive.

After the procession had passed, Dr Glock drove out of the town and along the road to the new campus. The al-Farabi house was on this road, about a kilometre outside the town. It was built on a steep slope, below the level of the road, from which one looks down on the roof of the house, with its solar panel array, hot water tank and television antenna. Glock parked the van on the gravel verge, under a fig tree. It was a dark day, so he left the van’s headlights on, not meaning to stay long. The time was just after three o’clock. Foreigners who knew Glock, that is people who were not Palestinians, were impressed by the fearlessness with which he drove around the West Bank during the intifada, the Palestinian uprising against Israeli rule that had erupted in 1987, going into areas where a vehicle with Israeli licence plates, like his, was almost certain to have stones thrown at it by children and teenagers. Glock had endured his share of stones, but he still went where he wanted to go, although lately he had begun to take precautions when he drove the van, aware that it was well known and that he was conspicuous driving it. He would vary his usual routes, and check underneath the van before he got into it. He was afraid of something, but whether it was a general fear for his safety at a dangerous time or whether he was afraid of something or someone in particular is unknowable, another blank in the narrative of history.

He walked around to the gate at the top of the driveway, pushed it open and walked down the concrete ramp. If you put all the accounts together, this is what happened next. A young man with his face wrapped in a kaffiyah, the black-and-white checked cotton scarf the Palestinians wear to identify themselves as Palestinian, dressed in a dark jacket, jeans and white sneakers, jumped down from the stone wall built against the edge of the road. He landed in the al-Farabis’ front garden, a strip of ploughed earth planted with olive trees. He could not be seen from the road. Glock probably didn’t see or hear him. Inside the house they heard the shots, two together, then one: like this, Lois said later, imitating the sound with her hands: clap clap … clap.

PART II The Archaeology of Archaeology (#ulink_38264268-c74e-5950-976a-fd7992f081a8)

TWO (#ulink_2791aedc-8a6d-5391-83db-52e9162b17d3)

TWO YEARS AFTER Albert Glock was murdered, I came across an article in the Journal of Palestine Studies (‘a quarterly on Palestinian affairs and the Arab – Israeli conflict’) entitled ‘Archaeology as Cultural Survival: The Future of the Palestinian Past’. Albert Glock was the author. I had never heard of him. At first glance, the article attracted my attention because it was unusual for this journal to publish an article on archaeology. Its usual concerns were political science and history, and detailed accounts of the latest diplomatic convolutions in the never-ending struggle for Palestine. The subject of the piece was intriguing, but then I read the biographical footnote that took up most of the first page: it stunned me.

Albert Glock, an American archaeologist and educator who was killed by an unidentified gunman in Bir Zeit, the West Bank, on 19 January 1992, wrote this essay in 1990 …

Dr. Glock spent seventeen years in Jerusalem and the West Bank, first as director of the Albright Institute for Archaeology and then as head of the archaeology department of Birzeit University, where he helped found the Archaeology Institute.

A brief review of the facts connected with his unsolved murder is in order. Dr. Glock was shot twice [sic] at close range (twice in the back of the head and neck and once in the heart from the front) by a masked man using an Israeli army gun who was driven away in a car with Israeli license plates. It took the Israeli authorities, who were nearby, three hours to get to the scene. Apart from giving a ten-minute statement, Dr. Glock’s widow was never asked about his activities, entries in his diary, possible enemies, and so on. The lack of Israeli investigation into the murder of an American citizen is perhaps the most unusual feature of the case …

Finally, the U.S. authorities, including the FBI, have not responded to repeated requests by the Glock family to look into the assassination or to ask the Israelis to do so. Prospects for solving the case thus appear remote.

I had never read a footnote like it. It contained volumes of subtext, all in sentences that ended with a question mark. The way it was written – in a tone of muted outrage – suggested that Glock was killed by some sort of Israeli hit squad (the gun, the licence plates, the lack of investigation). But why would an Israeli hit squad want to kill an archaeologist? Why would an Israeli hit squad want to kill an American archaeologist, even one with obvious Palestinian sympathies? Why would anyone want to kill an archaeologist?

What, moreover, did the writer of the footnote mean by ‘the lack of Israeli investigation’? Did that mean there was no Israeli investigation at all – or that there was no successful Israeli investigation? Above all, who was Albert Glock? Why was he teaching at Birzeit University, a chronically under-funded and embattled Palestinian university, especially since, as the footnote pointed out, he had formerly been Director of the Albright Institute, one of the most prestigious archaeological institutions in the Near East? Any addict of news about the Israel – Palestine conflict, as I was, knew that Birzeit was the site of countless unequal battles between students and the Israeli army, and frequently closed by order of the military authorities. A foreigner would only be teaching there if he had a serious commitment to the Palestinian cause: one would hardly consider it a prestigious academic post, a place one went to advance a career. What had brought Albert Glock to Birzeit? Why had he apparently chosen to devote himself to the perennially losing side in the Israel–Palestine conflict?

I entered the world of this footnote, and these questions became my life. The curiosity it aroused became a mission to investigate this obscure murder, buried away in a footnote in an academic journal, which surely no more than a few hundred people had read. There was a passion in there, in the story of the life and death of Albert Glock – something heroic and tragic that these sparse facts only hinted at.

Eventually, in September 1997, the footnote brought me to Bir Zeit, the weary little Palestinian town in the West Bank where Albert Glock’s life ended. I enrolled as a foreign student at Birzeit University, in the vague hope that I might penetrate the mystery of Glock’s death by being inside the institution where he taught. With the university’s help, I rented an apartment in the town from a Birzeit professor, Munir Nasir. A few weeks later, my partner Emma and our three-month-old son Theodore joined me. The three of us would bounce back and forth on the road between Bir Zeit, Ramallah and Jerusalem squeezed into shared taxis, with Theo strapped to my chest in a baby carrier. We carried him about the West Bank with a little black-and-white checked Palestinian kaffiyah that Munir Nasir had given us wrapped around his neck.

Our apartment overlooked the route that Glock took on his last day, from the Institute to the al-Farabi house. To my left, as I stood on the balcony, and just outside my field of vision, was the old town of Bir Zeit, the old campus, the Institute of Archaeology, and the Greek Orthodox church where the funeral took place on the day of the murder. Closer was the stretch of pavement onto which Glock pulled over and waited to allow the procession to pass by. Before me, and occupying most of the view, was a vista of rocky hills. In the distance, on the opposite hill, were the refugee camp of Jalazun, and above it the Israeli settlement Beit El, and to the right of them, on the horizon, the blinking radio masts of Ramallah. The panorama encompassed most of the area in which the events of the day of the murder took place. To the right were the rooftops of the centre of the town of Bir Zeit. Beyond the town stretched the road to Ramallah and, invisible where I stood, the al-Farabi house, in the driveway of which Glock was shot. Below, across the street, was a municipal trash dumpster which at night attracted feral cats, and by day jangled the nerves as people banged its metal doors open and shut; behind it lay a group of neglected olive trees standing in a clutter of soda bottles.

Lying open on the tiled floor in the hall was a partially unpacked suitcase containing a stack of papers: Glock’s correspondence, diaries, published and unpublished articles, the available documentation of his life, his work and his death. On a trip to the United States six months earlier, my first step in investigating the shooting, I had been to see Glock’s widow, Lois, and she had let me copy the papers and computer disks in her late husband’s enormous personal archive.

The documents conjured up the ghost of the murdered archaeologist. I read and re-read the material, and my virtual acquaintance with Albert Glock deepened. Sometimes I would forget that I never knew him, that five years separated our experience of this weary little town. I came to see him in my mind’s eye like the memory of an old friend. His life was an enigma, not least because his work as an archaeologist never reached completion. To me, he existed as a holographic image in a swarm of facts, but within this mass of data one pattern stood out clearly, like stars forming a constellation: a trajectory of purpose, vivid and irresistible. Glock’s life had been a mission. He had obeyed the severe demands of his conscience, and put the fulfilment of its imperatives before anything else in his life, and he had followed it unswervingly to the extreme and solitary point where a violent death closed in on him.

In the evenings I would sit on the balcony, eating grilled chicken from the restaurant across the road, looking out over the activity in the street below, and think that I was attempting the impossible, to know the unknowable, to capture the atoms of a moment that had passed five years ago. All societies have secrets that an outsider will never penetrate, and this was one held by no more than a handful of people, who would not tell me even if I could find them. The headlights of passing cars – the Mercedes taxis and battered pickup trucks – would illuminate me for a moment where I sat. The town looked peaceful enough, yet just down the road, outside the post office where I bought my first Yasir Arafat postage stamps, there were terrible scenes during the intifada, of people of all ages confronting the military force of the dominant Israelis, getting beaten and shot and tear-gassed. Now in the same place, four years after the Oslo Agreement had introduced limited Palestinian self-rule in the Occupied Territories, the precarious truce between Israel and Palestine was symbolized by groups of young Palestinian Authority policemen, strolling about with nothing better to do than check the licences of the taxis that plied the two kilometres to the Birzeit campus. The moment of the murder was lost and buried; it was now ancient history.

I had a copy of the autopsy in my suitcase. After Glock was shot, his body was taken to the Greenberg Institute of Forensic Medicine at Abu Kabir, outside Tel Aviv, and kept on ice overnight. The pathologist noted that the body was dressed in grey trousers, blue underwear, brown shoes and dark blue socks. One lens of his glasses was missing, and his stomach contained a porridgy material: the ka’ak simsim Glock had partly eaten earlier that day. The body showed the wear and tear that would be expected of a man of Glock’s age. His heart was in good condition. His lungs were a bit grey from smoking.

One bullet entered the back through the right shoulder, passed through the right lung, the heart and the liver, and exited through the lower ribs on the left-hand side. Another bullet entered under the right cheekbone (‘zygomatic bone’), passed through the skull and the brain and came out on the left-hand side of the neck. The paths of both bullets sloped downwards, which indicated that the gunman had fired from a position higher than his victim. This made sense: Glock was walking down a slope at the time, and the gunman fired from the top of the slope. A third bullet entered his right shoulder from the front and emerged at the back of the body. This third bullet was fired from below to above, indicating it was shot at a different angle, that the body was in a different position when this bullet entered. The entry and exit wounds were clean – ‘no marks of powder burn, soot and/or fire effect’ – which shows that the gunman was not using hollow-pointed bullets. Hollow-pointed bullets expand on impact and leave messy wounds as they pass through. They tend to be used by police officers because they bring the victim down quickly. The absence of these markings suggests that a military-type weapon was used: military weapons fire solid bullets, which leave clean exit and entry wounds.

It is hard to tell for sure which bullet was fired first, but the gunman may have fired first at Glock’s back, as he was walking down the concrete slope. This shot – which entered the right shoulder – then turned him around slightly, so that the bullet fired the next instant hit his right cheek. Glock fell forwards, onto his face, onto the concrete, wounding his nose and forehead. Then – and this depends on how much time elapsed between the first two shots and the last – Glock turned over where he lay, with his feet towards the gunman, and his head away from him, and the killer fired a final bullet into Glock’s right shoulder before he made his escape in the waiting car. Either he turned over in a spasm, or the gunman got close enough to turn him over, and then fired a last shot. The first alternative seems more likely. Glock was found lying on his back, with grazes on his face.

The pathologist estimated that the bullets were fired from a distance of about one metre.

THREE (#ulink_4e223f87-07bb-5479-aefe-86a0e9720a5c)

NOT MANY PEOPLE at Birzeit knew it, but besides being an archaeologist Albert Glock was also a Lutheran minister and a missionary. It was a fact that he preferred not to draw attention to. Being a minister was an aspect of himself that he had been gradually shedding in the last years of his life. He didn’t like people to know that while he was teaching archaeology at Birzeit his salary was being paid by his church back in the United States, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America. The word missionary oppressed him like a nightmare.

He could no longer believe what he used to believe. In his dedication to Birzeit, where he had taught for sixteen years and established the university’s archaeology programme, the first at a Palestinian university, he had developed a heretical personal theology from which faith and hope had been eliminated, and all that remained was an austere, angry and self-sacrificing Christian love. His decades of living in the land of the Bible had turned him into a dissident against the biblical God his Lutheran education had given him, whose interventions in human affairs the Bible traditionally described: for he had discovered that what he had thought of in his younger days as the land of the Bible was in reality the land of the Arab–Israeli conflict, the scene of a century of hatred, injustice and bloodshed. Over the years, he had turned his back on the discipline he had first come to Palestine to practise – biblical archaeology – and undergone a profound personal transformation into a totally different kind of scholar: still an archaeologist, but one who applied his skill to uncovering an alternative history of Palestine, a history derived from archaeological facts, rather than from the biblical narrative. This meant, in effect, a history not of ancient Israel but of the Palestinians. It was a view that set him against many of his former professional colleagues in archaeology, and against his own background.

It was a lonely position, and one in which in order to function from one day to the next, he was forced to rely, with little respite, on his own inner reserves of moral fortitude. He seemed to draw strength from the sheer difficulty of living in the midst of conflict, under military occupation, like the salamander of ancient belief, the creature that lives in fire. Yet the effort of will taxed him severely. In his last years, a dark current of emotional turmoil and depression flowed beneath the mental activity of his professional life.

This made him appear, to casual acquaintances, a formidable figure. He had little time for small talk, and little patience for anyone who did not appear to be living at a comparable pitch of intensity. For those he knew well, there was a dry sense of humour. The rest saw a man who looked sternly at the world through large square-rimmed glasses, and rarely smiled.

At sixty-seven, he looked younger than his years. His hair was grey, but still thick, with a fringe that swept off his forehead. His prominent, slightly cloven chin gave his features an air of fixity of purpose. It was the craggy face of a Midwestern farmer, one that had seen hard winters and stony ground. A preference for dressing in Bible black added to the severity of his appearance.

There was much in the way human beings relate to each other that he was simply too preoccupied to notice. In the delicate daily negotiations of academic life, he was gruff and undiplomatic: he often trod on toes, especially in an Arab society where a circumspect courtesy is an indispensable element of any transaction. He had a reputation as a poor listener: a conversation with Albert Glock tended to be a monologue in which Albert Glock spoke, compulsively and at length about whatever he was interested in, and the person to whom he was delivering it listened.

He didn’t seek popularity, or the role of the charismatic campus guru. He was little noticed on the Birzeit site, and preferred to keep as low a profile as possible, a tactic that enabled him to go about his work with the minimum of disturbance. It was the archaeology that mattered above all: everything else was secondary. Lois would often be disturbed by her husband waking up at two o’clock in the morning, his sleep cut into by a nagging need to look something up in a book. He would dash into his study and work until sunrise.

For his family, there was a heavy cost to bear in this exclusive concentration on archaeology. Albert Glock was an absentee father to his children – three sons and a daughter – for long periods of time, busy at Birzeit while the rest of the family was in America. As children, they had grown up with Middle Bronze Age potsherds strewn over the dining-room floor. In later years, they lost him entirely to archaeology, when it became clear that he would never return to America. All of this was quietly, loyally and patiently borne by Lois, who assumed the role of her husband’s archaeological assistant and grew to share her husband’s fervent belief in Palestinian archaeology and the larger Palestinian struggle.

Despite his position on the other side of the cultural divide that separates Israel and Palestine, he had a few friends among Israeli archaeologists, relations with whom had to be conducted virtually in secret, since Birzeit had and still has a policy forbidding co-operation with Israeli academic institutions, but the view of him among Israeli archaeologists who didn’t know him was that he was a misfit who had burned his bridges with the respectable mainstream and thrown in his lot with the enemy. ‘Why do you want to write about failure?’ a prominent Israeli archaeologist said to me in dismay, when I told him I was researching Glock’s life. ‘What books did he write? What did he publish? Where are the articles? Where are the students he trained? Where is the legacy? Where is the institution? Where is the lab?’

Yet the same person who was regarded as an alien in Israel was also regarded with suspicion by many Palestinians. ‘He was a difficult man, a controversial figure,’ a Palestinian archaeologist told me, one who saw Glock’s ghost casting a long dark shadow over Palestinian archaeology. And then, to prove his point, he said with a deliberate air of grave confidentiality, ‘I happen to know that he was trading illegally in antiquities.’

Determining who Albert Glock was, and why someone would want to kill him, was like archaeology itself. An archaeologist digs at a chosen spot, and in the course of excavation finds the rim and the handle of a pottery jug, a cooking utensil and a coin, and from those scant tokens of evidence creates a picture of who lived at the site and when. Another archaeologist finding the same objects might construct an entirely different picture. There is no final authority to appeal to. The archaeologist’s hypothesis is the best account there is until it is disproved, and he must change it if new evidence emerges.

The other unsettling fact about archaeology is that however convincing the picture one has formed may be, it will always be 99 per cent incomplete, because the breath of life is missing from it. However much we know of the world that produced that jug handle, rim, cooking utensil and coin, we will never feel the texture of everyday life that was felt when those objects were in use. In the same way, most of what could be known about the killing of Albert Glock is lost. Only a tiny fraction of the available data is retrievable, and what is retrievable is ambiguous. Yet to understand his murder would be to understand a whole society, and the conjunction of massive cultural forces. This was what I was hoping to do.

The Glock papers were my primary trove of artefacts. Among them was an illuminating autobiographical essay (twenty-nine pages, duplicated) written by Albert Glock’s father, Ernest Glock, in 1968. Ernest Glock was also a Lutheran minister, as were Albert Glock’s two brothers, Delmer and Richard, and his second son, Peter. The essay describes the austere environment into which Albert Glock was born, and tells of the formation of the determined, solitary, earnest adventurer that Albert Glock was to become.

Ernest Glock was born in Nevada in 1894, literally in a log cabin. His father (Albert Glock’s grandfather) came from the Franco-German province of Alsace-Lorraine, his mother from Switzerland. Ernest Glock’s parents were German-speaking Catholics who had emigrated to America, where they met in Carson City, Nevada, and married in 1892. Seven children were born and then the father disappeared, sending the family into penury. The youngest children were sent to an orphanage.

As a teenager, Ernest worked as a farm hand for room and board. He records the hardships he endured as a youth, sleeping in a freezing barn, milking cows, feeding hogs, and later herding sheep, which required camping alone for a week at a time. He would cook his supper on a sagebrush fire, sleeping with one ear cocked for the sound of a predatory bobcat or wolf. After a few years of herding sheep he got a job hauling cordwood. In this job he had to rise at 4 a.m. to drive a team of horses and mules.

Later he was taken in by an aunt and her husband. She was a convert to the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod, a St Louis-based organization that had been established to care for the millions of Germans migrating to the United States in the nineteenth century. When Ernest Glock expressed a need to improve himself by getting an education, his aunt suggested a Lutheran seminary in California. He took the advice. Before his graduation from the seminary he was sent as a Missouri Synod vicar and schoolmaster to Lebeau, Texas, a small town so steeped in German culture that even the blacks spoke German.

After graduating, Ernest Glock married a grocer’s daughter, Meta Matulle. Then he and his wife were sent to Gifford, Idaho, a rural, roadless place, surrounded by forest, where the congregation was again entirely German-speaking, and which is now within the borders of an Indian reservation (the Nez Percé tribe). ‘During my four and one half years as pastor I did not preach one English sermon,’ he wrote. Their house in Gifford had no indoor plumbing; their water supply was rainwater and snowmelt from the roof which drained into a brick cistern, and in the winter the thermometer could reach forty below zero. This is the house in which, in 1925, Albert Ernest Glock was born. A few months later, the family moved to Grangeville, a larger town not far away. They spent another three years in Idaho, before Ernest accepted a ‘call’ to a church in Washburn, Illinois, a small dot on the map north-east of Peoria, with a population of 900. This was where Albert and his two brothers grew up.

It was a claustrophobic, confining upbringing for the three boys, who were each a little more than a year apart in age. As the preacher’s children, they were always on show, expected to be models of good behaviour. Their father maintained discipline with a rod. Like most clerical families, their social status was proportionately higher than their income, and the rigour of their upbringing was mirrored in the plainness of their material circumstances. The house was heated with wood in the winter, and they bought their groceries on credit. Every day, their mother served supper at five o’clock. The meal was preceded and concluded with prayers. Until they went to grade school at the age of six or seven they spoke only High German at home. Their mother effaced herself in the duties of a minister’s wife and said little. ‘But she was the really intelligent one,’ Albert Glock’s younger brother Delmer remembered.

There was little in this upbringing to stimulate the minds of the three intelligent boys. The town itself – inhabited mostly by retired farmers, and surrounded by expanses of flat farmland – offered nothing. Their father, Ernest, was a practical man with few intellectual interests outside his vocation, and he disapproved of popular amusements like movies and dancing. His library was dominated by dry volumes of Lutheran theology.

Temperamentally, the boys were not rebellious. They were hewn from the same rock as their parents. They were obedient sons because it was in their nature to be obedient. They knew that they would upset their father deeply if they told him that they didn’t believe the Pope was the Antichrist, as Missouri Synod doctrine held, so they didn’t. When Albert sought a means of escape from this restricted world he quietly found one for himself in the voracious reading of books.

Delmer Glock was convinced that Albert’s interest in the archaeology of Palestine originated not in the text of the Bible but in the swashbuckling children’s adventure stories of Richard Halliburton, which were published in America in the 1920s and 1930s. In one of these books, Richard Halliburton’s Second Book of Marvels: The Orient, first published in 1938 when Albert was thirteen, one finds, after descriptions of the ancient Seven Wonders of the World, ‘Timbuctoo’, the discovery of Victoria Falls by Livingstone, a meeting with ‘Ibn Saud’ (King ‘Abd al-‘Aziz al-Sa’ud, the ruler of Saudi Arabia) in a tent outside Mecca, and visits to Petra and the Dead Sea, a swaggering account of an attempt to explore a ‘secret tunnel’ in the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. This may have been the spark that ignited Albert’s curiosity, kindled on the dry wood of an already abundant knowledge of the Bible. Exploration of the Temple Mount, the seat of the biblical Temple, also known as the Haram al-Sharif in Arabic, was and remains the holy grail of biblical archaeology, its central mystery, its ultimate prize, and a subject so thickly encrusted with myth and legend that the facts about it are easily lost. The cult of exploration of the Temple Mount, of which Halliburton was giving a simplified children’s version, could turn the homely familiarity with the Bible that Albert Glock already had into a genuine adventure. Halliburton wrote:

The more I heard about the caverns and tunnels and shaft, the more curious I became about them. How exciting it would be if someone could explore the entire passage, the passage lost all these centuries. If someone found the tunnel, it would lead – if the legend turned out to be true – right into the treasure-caverns from underneath. The reward of such an adventure might be the long-lost Ark of the Covenant, or the mummy of Israel’s greatest king.

I resolved to be that someone myself … Was I about to make one of the greatest discoveries in Bible history?

It may be a long shot to conclude that Albert Glock found the inspiration for his career as an archaeologist in the pages of the famous American adventure writer. But when he was still a teenager, he travelled on a freighter to Europe, just as Richard Halliburton had done, and years later he was excavating an ancient mound in Palestine, seeking to make discoveries in Bible history himself.

Albert showed a determined independence of mind that was unusual in a place where few aspired to individualism. ‘He was always off doing something,’ his brother Richard recalled; ‘we were never sure what it was.’ He remembers being mystified by the sight of his older brother writing Sanskrit and cuneiform characters on a piece of paper. ‘I don’t know where he got it from.’

At the age of thirteen, Albert told his father that he wanted to enrol at a residential pre-seminary high school for boys in Milwaukee, 200 miles away. The school was a German-style gymnasium where students learned Latin, Greek and Hebrew. Its purpose was to prepare boys for the Lutheran ministry. Albert’s parents could afford the fees, which were $200 per year, but not the cost of transportation, so from the age of thirteen, and for the next five years, Albert would hitchhike the 200 miles between Washburn and Milwaukee. Later, he announced that he wanted to specialize in the Old Testament, source of the legends of Solomon and the Temple and the ancient civilizations of the Near East.

Albert Glock’s motive in going to school in Milwaukee was as much a dedication to the Lutheran ministry as a desire to get out of Washburn. Later, his younger brothers Delmer and Richard followed Albert along this path, to the Missouri Synod ministry via the gymnasium in Milwaukee. By the time they had reached their late teens, the three boys had hitchhiked to every state in the Union. By the time they had reached their mid-twenties, they were Lutheran ministers.

Lutherans of the Missouri Synod subscribed unconditionally to the version of Christianity embodied in the classic works of Martin Luther, and were unimpressed with anything written later. Drinking from this pristine well of pure doctrine, based on a belief in the Bible as ‘the inspired, inerrant and infallible word of God’, Missourians saw themselves as forming ‘the only true visible church on earth’. Although it was the plan of the Missouri Synod leadership gradually to adopt English in church rites as soon as most of its members had acquired the language, and the work of translating the Lutheran classics could be completed (a process that began around the time of the First World War), the cultural and doctrinal conservatism of most members of the church were inseparable: to them, their native German tongue was the divine language of the Bible, as translated by the blessed Luther himself, and they only reluctantly gave it up completely in church services as late as the Second World War, spurred on by popular anti-German feeling in the United States.

The Missourians remained apart and solitary in their righteousness: it was not until the 1960s that they would agree to join Christian organizations that included other denominations. This attitude was reinforced by their social and cultural homogeneity: they were almost all German-Americans (there was also a Scandinavian element), and they were in and of the agricultural Midwest: two-thirds of them lived within a 300-mile radius of Chicago. Their separateness and common identity were not just ethnic. Members of the church did not need to look outside for education: the Missouri Synod had institutions that provided both. LCMS pastors were trained at an LCMS seminary – Concordia Theological Seminary, St Louis – and the children of LCMS members attended LCMS elementary schools, whose teachers were trained at an LCMS teachers’ college. As late as the 1930s, lectures in theology at Concordia Seminary were in Latin.

In 1932, they published a synopsis of their beliefs, bearing the plain title A Brief Statement of the Doctrinal Position of the Missouri Synod, which articulates everything a Missouri Lutheran believes or ought to believe. It completes the edifice of the all-encompassing Missouri world view with a Lutheran cosmology. This proposes a universe that came into being in exactly six twenty-four-hour days. ‘Since no man was present when it pleased God to create the world,’ it argues, ‘we must look for a reliable account of creation to God’s own record, found in God’s own book, the Bible.’ They reject any scientific explanation of the origins of man and the universe that contradicts the biblical account, whatever intellectual difficulties this may cause.

Salvation is achieved exclusively by divine grace: this is their primary doctrine. The Gospels and the Sacraments are the divine tools given man to promote access to this divine grace. Good works alone are insufficient for salvation: the idea is anathema. They also believe that the Pope is the fulfilment of biblical prophecies of the Antichrist. Anabaptists, Unitarians, Masons, ‘crypto-Calvinists’, ‘synergists’, and above all papists are held to be in dangerous error. They repudiate ‘unionism’, ‘that is, church-fellowship with the adherents of false doctrine’. These tenets were the result of decades of collegial deliberation by these pious, solitary, scholarly Lutherans, conducted in earnest conferences in small towns on the Midwestern plains, based on faith in the Bible as the infallible word of God. It is a Protestantism of the American farmer: pure, primitive, austere, unworldly, defensive. When it speaks at all, it speaks plainly.

So sincere and original is their study of the Scriptures that they declare in the Brief Statement, with poignant honesty, that there are matters on which they have not been able to reach a firm position. They acknowledge themselves stumped by the dilemma of why if ‘God’s grace is universal’, ‘all men are not converted and saved?’ ‘We confess that we cannot answer it.’ This is the doctrine – transmitted via the golden chain of Christ, the Bible, Luther and the Missouri divines – that Ernest Glock taught his sons at their family devotions. Albert later admitted that he had privately scorned his father’s world view, seeing it as narrow and exclusive of all but the concerns of his Missouri Synod flock.

Ernest Glock was unenthusiastic about his son’s scholarship: he thought basic seminary training was enough. But Albert, young and intellectually hungry, continued to enlarge his field of study. In 1949 he spent a year in Europe studying theology, and took classes in biblical criticism at the University of Heidelberg, and then returned to America to study Near Eastern Languages at the University of Chicago.

His study of biblical Hebrew would set Glock in opposition to one of the most intellectually constraining articles of the Brief Statement: ‘Since the Holy Scriptures are the Word of God, it goes without saying that they contain no errors or contradictions, but that they are in all their parts and words the infallible truth, also in those parts whichtreat of historical, geographical, and other secular matters.’ Historical and geographical matters were precisely what interested Albert Glock. His scholarly intellect was too keen, and his nature too individualistic to accept this traditional dogma unquestioningly. Nevertheless, he graduated from Concordia Theological Seminary in St Louis in 1950.

The following year, he married Lois Sohn, also a German-American, the daughter of a professor of Lutheran theology, and his life seemed set for the quiet and stable life of a Lutheran clergyman. He spent the next seven years as a pastor in Normal, Illinois, not far from where he had grown up, and seemed happy enough in his vocation. In the earnest, collegial spirit of Lutheran pastors, he closed his letters ‘yours in Christ’, ‘agape’ and ‘peace’.

But his more secular studies in ancient Hebrew continued. While still serving as a pastor in Normal, he enrolled at the University of Michigan, where his thesis advisor was George Mendenhall, a biblical scholar who introduced the Marxist-oriented ‘peasants’ revolt’ model of the origin of ancient Israel. Mendenhall’s theory was opposed to the traditional biblical view which held that Israelite tribes invaded Canaan and defeated the indigenous Canaanites. Mendenhall believed that a kind of theocratic liberation movement emerged within Canaanite society, gradually transforming it into what would ultimately be called ‘Israel’. His theory, revolutionary in its day, was an early instance of a history of ancient Israel that was distinct from the biblical account. Mendenhall’s approach was an important formative influence on Albert Glock, who received his doctorate in 1968. Thirty years later, Albert wrote in his diary that he ‘had wasted seven years in Normal, Illinois’. He didn’t have the patient personality a clergyman must have, who as part of his daily business must suffer gladly the lonely, the pedantic and the boring. In 1956, he was offered a job – or ‘answered a call’, to use the Missouri idiom – to teach, the following year, Old Testament history and literature at Concordia College, River Forest, Illinois, the teachers’ college for the Missouri Synod elementary school system.

The Missouri Synod’s insistence on the infallibility of the Bible created a tension among its scholars that developed in the late fifties and early sixties into a controversy and finally into a split in the church, a trauma from which it has only recently recovered. A liberal wing, acknowledging the ‘higher criticism’ of German biblical scholars like Julius Wellhausen, believed their faith in scripture was not undermined by analysing the Old Testament historically, and seeing it as the work not of Moses, but of later authors, writing from the eighth century BCE and afterwards. The Brief Statement breathes fire on this approach: ‘We reject this erroneous doctrine as horrible and blasphemous.’ The leadership of the Missouri Synod, representing the conservative mainstream, sought to stamp out this heresy, which was threatening to engulf the entire church. To put reason before faith in studying the Bible was the beginning of the end of religion, they argued. Worst of all, this heretical fire had broken out in the church’s theological engine room, the Concordia Theological Seminary. One of the means the leadership used to extinguish it was to demand allegiance to the Brief Statement by the forty or so dissident professors at Concordia, which the professors were unwilling to do, arguing it infringed their right to academic freedom.

Although Glock was teaching elsewhere, he took the side of the dissidents, since this was the direction he too was following in his biblical studies. His eldest son, Albert Glock Jr, recalled later that in the family devotions he led with his own children, he would teach them about the ‘Yahwist’ and the ‘Deuteronomist’, as two of the biblical authors were named in Wellhausen’s analysis: an approach that defied his own father’s stern literalism.

In 1960 (aged thirty-five), he wrote an article in defence of the dissidents entitled ‘A critical evaluation of the article on Scripture in A Brief Statement of the Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod’. The tone of the article was conventionally and respectfully pious, but the criticism it contained attacked the Missouri Synod’s uncompromising doctrine at its heart. The church’s theology is locked in the seventeenth century, he wrote, resulting in ‘a serious breakdown of communication when speaking to our age’. He then went on to propose a tectonic shift in the church’s doctrine, away from its most distinctive feature, its stubborn belief in the literalism of the Bible, towards an emphasis on its meaning and spirit, aware that it was a product of human authorship.

After Glock read the article at a meeting of his department at Concordia Teachers College, they insisted that it be locked in a safe and not allowed to circulate. For Albert, the episode was his first public act of opposition. He saw it as the symbolic sealing of his fate. Henceforth, he would always be a dissident.

The rebels of Concordia Seminary eventually accepted defeat. They left the church, and founded Seminex, a ‘seminary in exile’. Their departure strengthened the conservatives’ grip on Missouri Synod doctrine. Seminex survived in the wilderness, training Lutheran pastors who were not recognized by the Missouri Synod until 1988, when it voted itself out of existence and joined the more liberal Evangelical Lutheran Church of America.

In an essay unpublished during his lifetime, written when he was at Birzeit, Albert Glock described himself as ‘a skeptical white American tending to minority views’. Taking the side of the liberals in the Missouri Synod split was like rebelling against his father. Taking the minority view was an instinct that he was to follow at every crossroads in his life.

‘It has occurred to me more than once,’ he wrote, ‘that I have chosen usually the losing side, the down side, in whatever I have done. I suppose the two most notable examples are the left side of the church and the Palestinian side of politics.’ This is the motive that drove him through an intellectual, political, spiritual and personal evolution that he began as a Lutheran pastor, becoming, in succession, biblical scholar, biblical archaeologist, Palestinian archaeologist, and, finally and improbably, intellectual commissar for Palestinian cultural nationalism, which ended in his assassination. All of this was done in a robustly Lutheran spirit of earnestly working things out in the tribunal of his own conscience. In this he was following the example of Luther himself. Glock was always nailing his theses to the door, and taking the consequences.

Glock’s journey from the plains of the Midwest to the concrete slope of his assassination was an odyssey of gradual, determined metamorphosis. As soon as he completed one stage of personal transformation, he would renounce it, seeing on the horizon a clearer and sharper image of truth; and once a new image of truth appeared to him, he would head towards that, regardless of the consequences. Glock’s goal was to throw off the burden of his own past, his own background. At sixty-seven, he was on the verge of reaching it. And then he was shot.

His life was an odyssey, but when he died it was unfinished. An odyssey is a process of the maturation of the self, a narrative whose meaning and purpose become clear once it is at an end, once it has come full circle. Ulysses, the hero of the original Odyssey of Homer, goes on a long journey, undergoes trials, and returns home fulfilled. The homecoming completes and resolves the process. Without it, the odyssey is not complete, and its meaning and purpose are not realized. Glock’s long odyssey was violently ended before it reached that point of fulfilment.

FOUR (#ulink_f5212c07-5d97-5244-993b-b7f81e431297)

THEORIES ABOUT WHO might have been responsible for the shooting circulated in the first news reports broadcast within hours of the firing of the bullets. The Birzeit University public relations department had to act quickly to manage the almost immediate descent of reporters. The department’s two senior staff members, who were well accustomed to the task of megaphoning to the international media the university’s outrage at the regular shooting, killing and arrest of its students by the Israeli military, were both out of the country, and the job of announcing the university’s official reaction fell to a young Canadian aid worker, Mark Taylor, who had been seconded to Birzeit from what is now Oxfam Quebec in Jerusalem. He was at a friend’s house in Ramallah when the acting president of the university, Gabi Baramki, called him. They discussed the reports that had already been broadcast on the Israeli radio station, Qol Yisrael, which stated, as if it were a known fact, that Glock had been killed by a Palestinian, either in a family conflict or as a result of the dispute at the university. Gabi Baramki wanted to get across that there was no certainty at that point about who killed Albert Glock. It was inconceivable to Baramki that a Palestinian could have done it. He dictated to Mark Taylor the approximate wording, and let Taylor do the rest.

The press release that was circulated that day read, after announcing the fact of the murder and giving a short biography of Glock:

According to Israeli news reports, Dr. Glock was shot to death late this afternoon near the village of Bir Zeit. To the University’s knowledge, there were no witnesses to the attack on Dr. Glock. The University condemns this act in the strongest possible terms. It further holds that such acts are totally uncharacteristic of the spirit of the Palestinian community, and could only have been perpetrated by enemies of the Palestinian people.

The last sentence, carefully vague, directed suspicion towards the Israelis, while allowing in its sense that a Palestinian could have been responsible.

The killing made it into the following day’s Jerusalem Post. This story included speculation about who might have been responsible. ‘Palestinian sources’, the paper reported, ‘said last night they suspected Glock was slain by Hamas terrorists trying to stop the peace process.’ The Israel–Arab peace talks, which would end in the Oslo Agreement in September 1993, were under way, and the Islamic party Hamas had declared their total opposition to the negotiations, which they considered capitulation to the Israeli enemy.

The theories followed a predictable pattern: each side blamed the other. In response to the suggestion that Hamas was responsible, Gabi Baramki was quoted saying, ‘This man has been with us for sixteen years and has been working with all his strength to serve our people. A nationalist murder [that is, a murder by Hamas, a nationalist group]? That’s impossible.’

The Jerusalem Post went into greater detail in the story it published the following day. This widened the field of suspicion, but again set it squarely on the Palestinian side:

Two motives for the crime are being discussed around campus [figuratively speaking: the campus had been closed for four years]. The first, say Arab sources, is that Glock was killed either by Hamas or Popular Front activists in order to disrupt the peace process. They also link the timing of this killing to the fact that he was an American citizen and this is the anniversary of the Gulf War.

It was not quite perfect timing: the Gulf War started on 16 January 1991, and Glock was killed three days after the anniversary.

‘The second version is that the murder was part of a power struggle among the archaeology faculty, one of whom was fired recently. Birzeit president Gabi Baramki denies this emphatically.’ The Israeli police spokesman persistently lobbed the tear-gas canister of suspicion into the Palestinian yard in her comments to journalists. ‘We’re looking at the power games at Birzeit theory,’ she said.

In turn, Birzeit lobbed the canister back. ‘We are all in shock about this. He had been with us for many years and was well respected,’ Mark Taylor said. ‘I have no doubt that this does not come from the Palestinians.’ This meant it must therefore have come from the Israelis.

Three days after the killing, the PLO broadcast a statement on their Algiers radio station, Voice of Palestine. The statement set the murder squarely in the front line of the Israel – Palestine conflict, making the simple, obvious equation that Glock was the victim of a political assassination because of the political potency of his archaeological work, and that Israel was responsible for it.

The PLO denounces most strongly the ugly crime of the assassination of the US professor Dr Albert Glock, head of the Palestinian antiquities department at Birzeit University, where he contributed with his technical research to the refutation of the Zionist claims over Palestine. Zionist hands were not far away from this ugly crime, in view of the pioneering role which this professor played in standing up to the Zionist arguments. This crime provides new proof of Israel’s attempts to tarnish the reputation and position of the Palestinian people in American and international public opinion. The PLO extends its most heartfelt condolences to the family and sons of the deceased [not entirely accurate, since the Glocks also had a daughter], who are residents in Palestine, and to the Birzeit university family.

The PLO statement was one of a flurry of denunciations of the murder that were published in the days immediately after the shooting. The clandestine leadership of the intifada, the Unified National Leadership, included one in their first bulletin after the incident. The UNL were as quick and as certain as the PLO in their attribution of blame.

The Unified Leadership denounces strongly the assassination of Dr Albert Glock, the head of the archaeology department at Birzeit university, who was attacked and killed unjustly and holds the secret agencies of the Zionist enemy responsible for the killing of Dr Glock who gave invaluable services to the Palestinian community and gives its deepest sympathies to the family of the deceased.

Even Hamas issued a denial, eight days after the killing, in a statement whose main point was to contradict a report in the Jerusalem Post that said it was responsible.

These announcements do not represent what one might call a considered view. They were verbal gunfire against the enemy in a war in which both sides naturally and with total conviction expected the worst from each other.

Gabi Baramki (who bore the title of acting President of Birzeit because the appointed President, Hanna Nasir, was in Israeli-imposed exile in Amman), shared the almost universal Palestinian view that the hand behind the killing was Israeli. He based his suspicion on the length of time the army took to arrive at the scene.

‘Can you just give me an explanation for it?’ he said to me, when I met him in his house outside Ramallah, the one Glock had intended to visit on his last afternoon. Gabi Baramki was a tall, courteous Palestinian patrician, with a thoughtful, diffident, donnish manner, about the same age as Glock. ‘Israel has a very efficient and effective system of policing. But to come three hours late!’ he said.

The killing happened at about 3.15 p.m. The army didn’t arrive until some time after six. Yet when the Israel National Police gave a terse list of official answers about the incident to the American Consulate a year later, at the request of the Glock family, they claimed that the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) patrol arrived at five minutes past four, a discrepancy of two hours. Trying, with difficulty, to understand his thinking, I asked Baramki, ‘Why would they want to kill Albert Glock?’

He answered cryptically, ‘The Israelis always like to kill a hundred birds with one stone.’

He meant, I think, that the killing was intended to create fear among the Palestinian population, to damage Birzeit’s reputation, to create an excuse to close the university permanently if they wanted to, to frighten the remaining foreign teaching staff at Birzeit into leaving, to spread discord and suspicion, to weaken Palestinian morale, above all to rid the country of a troublesome intellectual who was literally digging up embarrassing facts. These were the motives that people discussed.

On the last point, digging up the past, an educated Palestinian like Gabi Baramki would have some knowledge to back up his suspicion. Since the occupation of the West Bank began in 1967, the Israeli censors had maintained a hawk-eyed vigil for anything that contained a Palestinian version of the history of the country, banning hundreds of books. Baramki himself published an article in the Journal of Palestine Studies in 1988 on Palestinian education under occupation. In 1976 (he wrote) Birzeit tried to establish standardized literacy and adult education programmes in the West Bank. ‘The university … began preparing instructional materials that included information on Palestine. Unfortunately, some of the books were confiscated by the Israelis because they contained the history and geography of a particular village or town demolished in 1948,’ he wrote. Recording the Palestinian past was considered an act of sedition.

‘But what was the purpose of the delay?’ I asked Baramki.

‘They wanted to give the person who did the shooting time to run away!’

Looking at the matter from his point of view, I could see a wicked logic. The way he told it, his account made sense – not perfect sense, but it was the best explanation available.

The other strange thing was that the army did not impose a curfew. In the past two months, two severe curfews had been imposed on the Ramallah area in response to incidents where guns had been used by Palestinians against Israelis. The first incident was on 1 December, when Israeli settlers from the settlement of Ofrah, near Ramallah, were shot through the windshield of their car as they drove through the adjoining town of al-Bireh. One of the settlers was shot in the head and later died in hospital, and his woman passenger was also hit by a bullet, but not fatally. Responsibility for the attack, in the language of these things, was claimed by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), a Marxist faction of the PLO. The response of the army was immediate and harsh. The entire district, which included Bir Zeit, was closed off. Roadblocks were deployed, and the army carried out thorough house-to-house searches, detained 150 people and interrogated many more than that. A curfew was imposed which lasted six weeks.

Glock himself referred to it in one of his last letters: ‘The curfew on Ramallah was very tight for two weeks and effectively shut down the University. The night-time curfew that has since been imposed, from 5 p.m. to 4 a.m., was lifted for 3 nights, 24–26 December. Then came the order not to use the roof of your house unless to hang washing and then use it for only 2 hours in a day.’

The other incident took place five days before the assassination of Dr Glock, outside ‘Ain Siniya, a village about five kilometres north of Bir Zeit. A bus carrying Israeli settlers was attacked with stones and gunfire as it drove along the main road between Ramallah and Nablus at about six o’clock in the evening. In the words of the news report broadcast that night on IDF radio, ‘Troops have closed off the area and are combing it for perpetrators.’ No one was hurt, let alone killed. But the attack provoked a massive military response, with helicopters and house-to-house searches.

But when, five days later, a shooting took place in a Palestinian village, and the victim died, there was no curfew at all. The army weren’t interested.

Baramki told me that soon after the murder, ‘we got in touch with the PLO outside’.

‘Why?’ I said.

‘Just to check if they knew anything, to see if it had anything to do with any of the [Palestinian political] factions. Because we wanted to know.’

Gabi Baramki was a regular visitor to PLO headquarters in Tunis. He would go there to plead for funds for the university. Until the PLO’s treasury was depleted by the loss of gifts from the oil-rich Arab states of the Gulf, in retaliation for the Palestinians’ support for Iraq in the Gulf War, Birzeit had been funded almost entirely by the PLO. Gabi Baramki himself was a mainstream PLO man, aligned with no particular faction within it, but supporting it like most Palestinians did, as their obvious representatives in world politics, for better or for worse.

PLO headquarters in Tunis told Baramki they knew nothing about the murder. But they did not let the matter rest. They told Baramki to arrange for a Palestinian investigation into the murder, and asked that a report be written. So Baramki organized a committee of enquiry. At the head of it was a local Fatah politician, businessman and Arafat loyalist named Jamil al-Tarifi, now a member of the Palestinian Legislative Council and Minister of Civil Affairs in the Palestinian Authority. The other members were Mursi al-Hajjir, a lawyer and an associate of Tarifi, and two journalists, Izzat al-Bidwan and Nabhan Khreisheh. Most of the work was done by the journalists, and the report itself was written by Nabhan Khreisheh.

Khreisheh’s report can best be described as a work of crepuscular forensics. Unable to establish any substantial facts, because the conventions of the conflict prevented them from seeking information from the Israel National Police, he deduced a suspect – Israel – from the pattern of meaning he discerned in the common knowledge about the case. It is mainly of interest as a record of the prevailing currents of gossip and rivalry inside Birzeit University. Otherwise, the report was such a whitewash (and in its English translation, such a muddle to read), that I wondered if Khreisheh knew more than he dared to put in it.

He had a mobile phone, like a lot of Palestinians. You can wait years for a land line in the Occupied Territories. I called him and arranged to meet him one evening in Ramallah. We met across the street from the main taxi park and we went to a café. As both a journalist and a Palestinian, he was a rich source of the political intrigue which is the Palestinian national pastime. His English was comparatively lucid, and his style salesmanlike and shrewd, but he liked to talk, and was particularly interested in this case.

‘Abu Ammar [the name by which PLO leader Yasir Arafat is familiarly known among Palestinians] called me personally and said, “I want that report on my desk in twenty-five days.”’ Khreisheh said. I speculated that he was chosen to write the report because of a feel for politics, rather than for his research skills. He told me that he had a degree in media studies from a university in Syracuse, New York, and was a stringer for the Washington Post. I had heard that he had done work of some kind for the PLO before, though I didn’t know what.

‘I accept the weakness of this report,’ he said. ‘The purpose of it was so that Arafat could have something in his briefcase, that he could show people on his plane, especially Americans, that cleared the Palestinians, so he could say, “Look, here is this matter of an American citizen who was killed in the West Bank and we are taking it seriously while the Israelis are not.” It was a political report. The object of it was to clear the Palestinians.’ It was kept confidential for about two months.