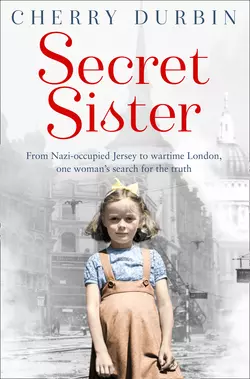

Secret Sister: From Nazi-occupied Jersey to wartime London, one woman’s search for the truth

Cherry Durbin

The true story of a woman who uncovered the dramatic stories of her mother and sisters with the help of the award-winning television programme, Long Lost Family.Adopted at a young age, Cherry Durbin had spent over twenty years searching for traces of her natural mother with no success. She had given up until one day, watching the drama unfold on the television programme, Long Lost Family, her daughter suggested that maybe this was the only way she would ever find her mother.What she didn’t expect to uncover was a story of a pregnant mother fleeing Nazi-invaded Jersey, a sister left behind to survive the deprivations of the German-controlled island and a family torn apart in a time when war left so many alone. Cherry’s story, pieced together by a team of researchers, would bring her unimaginable sadness and joy, and answers where she had given up.

(#u86f8dd10-bbde-5163-b86a-7bfaa87f2712)

Copyright (#u86f8dd10-bbde-5163-b86a-7bfaa87f2712)

Cherry’s story appeared on the TV Show Long Lost Family, produced in the UK by Wall to Wall Media Ltd. This book does not reflect the views or opinions of either the makers of Long Lost Family or the broadcaster.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperElement 2015

SECOND EDITION

© Cherry Durbin 2015

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Cover design by Micaela Alcaino © HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Cover photographs © Rosmari Wirz/Getty Images (girl, posed by model); © Shutterstock.com (background)

Cherry Durbin asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780008133078

Ebook Edition © July 2018 ISBN: 9780008133085

Version: 2018-07-05

Dedication (#u86f8dd10-bbde-5163-b86a-7bfaa87f2712)

For John, my Essex boy, my soulmate, who accepted me as I was and didn’t try to change me. I carry you in my heart into this new phase of my life.

For Mum and Pop, who gave me love and stability for the first eight years to build the rest of my life on.

And for my kids, Helen and Graham, who’ve had to put up with me since they were born. I love you and I’m so proud of you.

Contents

Cover (#ub5a91f92-f698-5830-9f88-44823989d1bd)

Title Page (#u3ba29676-db59-5b3a-b01d-b2cf60bf67c2)

Copyright (#ud09ed354-2ccf-54c6-a903-1eb8b848116f)

Dedication (#u1208cf9a-ae6b-5c12-927a-65c914414493)

Prologue (#u8ed40345-fdc8-5086-806c-a25f4b0fbe1c)

1 Mum Looks Like a Chinaman (#u188f7d31-f861-5283-8385-71e157cf86ed)

2 The New Woman in Our Lives (#u644e2785-cedd-5aaf-858e-80ff896e62ec)

3 My Closest Friend, Grizelda the Goat (#u0c0c0129-b460-5813-b112-7055dd831787)

4 A Hasty Marriage (#udab543af-4a1f-5ff7-9a92-b1f96fe27ae1)

5 Learning to Be a Mum (#u271dee2e-3256-5b14-afed-f79d11665e8a)

6 Breaking Out of Domesticity (#u295bee01-81d7-5fd1-9d9f-5fcc43350355)

7 Searching for My Birth Father (#ud6083686-571d-5c7e-8c1d-13a548e0297f)

8 Losing My Real Father (#litres_trial_promo)

9 My Half-sister Sue (#litres_trial_promo)

10 On the Trail in Jersey (#litres_trial_promo)

11 Tea with the Renoufs (#litres_trial_promo)

12 A Disintegrating Marriage (#litres_trial_promo)

13 Making a Move (#litres_trial_promo)

14 A Larger-than-life Character (#litres_trial_promo)

15 Getting in Touch with Daisy (#litres_trial_promo)

16 The Boxing Day Meeting (#litres_trial_promo)

17 Daisy’s Story (#litres_trial_promo)

18 Meeting the Bartons (#litres_trial_promo)

19 A Wedding and a Funeral (#litres_trial_promo)

20 Looking for Sheila (#litres_trial_promo)

21 Making Peace with Billie (#litres_trial_promo)

22 Going Bust and Climbing Back Up Again (#litres_trial_promo)

23 Shadows Blot Out the Sun (#litres_trial_promo)

24 The Email (#litres_trial_promo)

25 The Professionals Take Over (#litres_trial_promo)

26 The Visit (#litres_trial_promo)

27 The Meeting at High Wycombe (#litres_trial_promo)

28 The Families Get Together (#litres_trial_promo)

29 My Jersey Family’s Wartime History (#litres_trial_promo)

30 Learning more about My Birth Mother (#litres_trial_promo)

31 September in Spain (#litres_trial_promo)

32 Bonding by the Pool (#litres_trial_promo)

33 Learning to Be Sisters in Our Seventies (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#u86f8dd10-bbde-5163-b86a-7bfaa87f2712)

One evening in May 2011, I was slumped on the sofa with my collies, Bear and Max, beside me, half-reading a book and half-dozing. It had been a long, busy day. I’m a very early riser because I’ve got two horses, Kali and Raz, in a stable down the road and they need to be rubbed down, mucked out, fed and taken to their field at the crack of dawn. Horses don’t like to hang around waiting while humans have a lie-in, so that’s the first thing I do in the morning, come rain, snow, hail or sunshine. Next there are the dogs to walk, and they’re big, energetic dogs who like a good, long run around. I help out at the local kennels and in exchange they let me leave Bear and Max with them if I have to go away somewhere. And I also pop in to look after some elderly folks in the area, including one lady with dementia. So for a 68-year-old I had a pretty full life. It did mean I wasn’t fit for much come the evening (by which time I’d got the horses and dogs back indoors, rubbed down, fed and so forth).

I don’t really watch much telly, but it’s sometimes turned on as background noise, just as company really because I live alone now. My set is only a tiny, portable one that I got third-hand from my daughter Helen, so it’s easy to ignore, but that evening I suddenly remembered that Long Lost Family, a programme that reunited estranged families, was on. I found the show fascinating because I had been searching for my own family for almost thirty years and knew what a difficult emotional journey it could be. I’d missed the beginning of the programme but on the screen a pretty, dark-haired woman was talking about her search for the mother who’d given her up for adoption back in the sixties.

‘I had a really happy childhood with my adoptive family,’ she said. ‘It’s just that I’ve always felt different from them. They don’t look like me … I want there to be someone out there who looks a bit like me, who is a bit like me.’

Now, I knew that feeling of not entirely fitting in because I had been adopted by parents who didn’t particularly look like me, with whom I didn’t share any genetic features. Mum and Pop were a wonderful couple and I’d loved them to pieces, but both had passed away long ago.

On screen, the girl was saying she was anxious that if they tracked down her birth mother, the woman might not want to know her. I could identify with her anxiety because I’d been in that exact same situation. The more I’d probed into my own past, the more I’d hit brick walls and dead ends. I’d had some success – just enough to find out that I had a sister, Sheila, somewhere, but I had no idea where. I was determined to find her one day because I needed answers to all kinds of mysteries from my past, things that simply didn’t add up. I was a widow, with two wonderful children and four grandchildren of my own, but I had no family roots, no one of my generation or older to help me understand where I came from and to make me feel there was a family I belonged to. Basically, I was lonely, and I’d been lonely for much of my life since Mum had died. I’d been a lonely teenager, I’d had a lonely and difficult first marriage, and now at the age of sixty-eight I was on my own again.

On screen the presenter, Davina McCall, told the girl that they had finally found her birth mother, and I found my eyes filling with tears. It was odd, because I’m not the crying type. I’m so well practised at bottling up my emotions that they rarely see the light of day. I suppose this girl’s story touched a nerve for me because it was so close to my own.

The girl and her birth mother met in a park and gave each other a huge hug. The mum was murmuring, ‘Thank you, thank you,’ and I could tell they were both lovely, friendly people. They seemed very similar, and you could definitely see a family likeness. I hoped it would work out for them and that they’d find what they were looking for in each other.

The team did two searches in each programme and they succeeded in reuniting the family members in the other story as well. They always did. I’d run out of ideas, having tried everything I could possibly think of to find my missing sister.

And then at the end of the programme there was an announcement: ‘If you have a long-lost family member and would like to take part in the next series, please email us at this address.’ I grabbed a piece of paper and a pen and scribbled it down. Fortunately, I always have paper and a pen lying around to write notes to remind myself of things I would otherwise forget.

I picked up the phone and rang my daughter Helen. ‘Were you just watching telly?’ I asked. She was, but a different programme, so I explained to her what I’d seen.

‘That’s funny!’ Helen said. ‘You were telling me just the other day that you must do something about finding Sheila. It’s as if this is a sign.’

I felt the same way myself. ‘Will you email them for me?’ I asked. I had a computer but it hadn’t been working for ages and I felt no pressing need to get it fixed. I was more of an outdoorsy person than a desk type. ‘You know all about my story.’

‘OK, Mum. I’ll do it tomorrow. Wouldn’t it be amazing if they could find Sheila? I’d have a new auntie!’

‘Oh, I don’t think they will,’ I said. ‘It’s all too late and too long ago. But it would be interesting to let them try. They might have methods I haven’t thought of …’

‘Yeah, like using the internet,’ Helen said with a sarcastic edge to her voice.

‘You never know. I’ll call you tomorrow, Nell.’

As I got into bed, I couldn’t help picturing myself on the programme at that moment when you meet your family member against a beautiful backdrop. It would be so wonderful if they found Sheila. I’d always wanted a sibling, and I’d been searching for her for almost thirty years now. It nagged away at me, something I couldn’t let go of, a piece of unfinished business.

But then I told myself sternly not to get my hopes up. The television company must get hundreds of requests and they can only take on a few; and I simply didn’t believe they’d be able to find Sheila. It was safer not to have any expectations so that I wasn’t disappointed later. And that’s all I had time to think before I fell into a sound sleep.

1

Mum Looks Like a Chinaman (#u86f8dd10-bbde-5163-b86a-7bfaa87f2712)

I was a war baby, who used to scream when woken by the wail of the air-raid sirens and the middle-of-the-night dash for cover. Dad told me that he and Mum normally huddled under the stairs until the all-clear sounded, but one night, for some reason, he decided that we should all go to the neighbourhood shelter – and it was just as well he did because that night our house took a direct hit and the stairwell was destroyed. The top of the shelter we were in collapsed and rubble showered down on us, but no one inside was hurt. If it hadn’t been for Dad’s last-minute decision my story, which began with my birth in March 1943, would have been a brief one.

We’d been living in Hayes, Middlesex, but after the bombing the Red Cross billeted us with a family in Uxbridge, next to the railway line. We had the back scullery and front bedroom, and my earliest memory is of standing up in a makeshift cot, looking out the window at the lights of the trains trundling past. It must have been tough for my parents; they’d salvaged any possessions they could from the wreck of our house, but like many other families at the time they’d lost most of their furniture, kitchenware, clothes and prized personal possessions. Dad retrieved all the scrap wood he could to make new furniture, but many things simply couldn’t be replaced. Meanwhile, Mum had me to take care of. She said I was a greedy baby and she struggled to get extra rations of national dried milk to feed me; I also scratched incessantly if there was wool next to my skin, but it didn’t prove easy to find substitute fabrics for vests in wartime.

The war influenced us all in another way as well: I was only being brought up by my mum and dad, Dorothy and Ernest Vousden, because the woman who had given birth to me was unable to look after me. Mum said that the first time they went to see me I was in a grubby little cot wearing a dirty nightie. She and Dad couldn’t have any children of their own and desperately wanted me, so they took me to live with them when I was just a few weeks old then adopted me in a court of law. This was explained right from the start, and it never bothered me in the slightest. On the contrary, I felt lucky because I had two wonderful loving parents who doted on me.

‘Where is my real mum, then?’ I asked Dad sometimes, and he always replied, ‘In the land where the tigers grow.’ That sounded reasonable to me.

We moved to Salisbury, Wiltshire, which is where I started school at Devizes Road Primary. Dad got a good job as the representative of a leading aviation company, Fairey Aviation, at RAF Boscombe Down, where top-secret experimental aircraft were tested, and Mum was a stay-at-home mother who cooked wonderful meals, baked cakes, knitted, sewed, crocheted and generally took the best of care of us. She made most of my clothes by hand and taught me how to knit and crochet myself. Once a week she washed my hair in rainwater to make it shine, and used a product called Curly Top in a futile attempt to give me curls. Her own hair was worn in what was known as a ‘victory roll’, sweeping off the forehead into two lavish loops on top. She was a statuesque lady who always dressed smartly, in hat and gloves, when we went out somewhere, and she made sure I looked spick and span as well.

Mum was very musical and she’d be singing as she sharpened the knives on our back doorstep, scrubbed the sheets on Monday wash day, or sewed new outfits for me on her Singer sewing machine. She taught me all the old wartime music-hall songs: ‘The White Cliffs of Dover’, ‘Roll Out the Barrel’, ‘My Old Man Said Follow the Van’ and ‘My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean’. She played the piano beautifully, and at bedtime, after Dad had read me a story, Mum would play a song on the piano to lull me to sleep. My favourite was one called ‘Rendezvous’. I loved to drift off with the sound of the piano floating up from downstairs.

From my earliest years, I simply loved animals. We had a Corgi called Bunty and a cat called Dinky, who stood in as my playmates since I didn’t have any brothers or sisters. Horses were always my favourite, though. I used to pretend that I was riding a horse in the porch at home, and I made a beeline for any horses and donkeys I spotted when we were out. Finally, when I was eight years old, Mum let me start riding lessons at the local stables and I was overwhelmed with excitement. It was the best thing that had ever happened to me in a life that was pretty good already, and I took to the saddle like a duck to water. I wasn’t spoiled, mind – I’d be swiped on the back of the legs with a hairbrush if I was misbehaving – but I was very, very loved.

Although I was christened Paulette, Dad called me his little ‘Cherryanna’ and the name stuck. Soon it was only teachers who called me Paulette and to everyone else I was ‘Cherry’. I called him ‘Pop’, and I was definitely a daddy’s girl, who cherished the time I spent with him. Each morning before breakfast we’d go out into the garden and walk round, inspecting the pond, deadheading the flowers and checking to see what had ripened in the vegetable patch. He’d pull up some carrots, wipe one on his hankie and hand it to me, saying, ‘Eat that, Cherryanna!’ In autumn he’d stretch up and pluck me a rosy apple from the tree, polishing it on his sleeve till it shone. When we went back indoors for breakfast, he’d sit on the stairs and carefully clean the mud from my shoes for me. Then on Sunday mornings, when he wasn’t in a rush to get to work, I’d climb into their bed and Pop would bring up tea and chocolate biscuits and play ‘camels’, with me sitting on his knees and riding up and down.

He was a talented carpenter, and one of my most prized possessions was an elaborate doll’s house he made me, a bungalow with a garden around it, and when you took the roof off you could see all the furniture inside. It was so detailed that there was even a little sundial in the garden, just as we had in our own garden.

I’m a visual person and all these memories are vivid pictures I carry around in my head, pictures that bring a sense of warmth and happiness and belonging. I also have a clear picture from the age of eight of a time when Mum and I were out sitting by the pond in the garden. I noticed her skin was all yellow and I said, ‘Mum, you look like a Chinaman.’* (#ulink_3ee19ba6-7315-50ba-9c67-056850c3a9fb) Later I overheard her repeating my comment to Pop and both of them laughing, but I couldn’t understand why it was funny. No one ever mentioned the words ‘liver cancer’ to me, not till I was much older, and I wouldn’t have known what they meant anyway.

A few weeks later, Mum had to go into hospital and I was taken to stay with some family friends, the Davidsons. I was quite happy there because I liked their son Donald, who was the same age as me; we did ballet at school together, co-starring in a production of Sleeping Beauty. I was going through a stage of feeling that I would rather be a boy than a girl, and Donald and I were great pals. As an only child, it was just nice to have another child in the house, someone I could play with. Mr Davidson had a film projector and we all sat and watched films in the evenings, which was great fun. I was so grateful to them for letting me stay that I tried to cook them breakfast one morning on their gas stove. In retrospect it must have been rather alarming for the family – but at least I didn’t set the kitchen on fire.

I was happy enough, but in the back of my head there was a niggling worry: if Mum was ill enough to have to spend so much time in hospital, how would she ever get well again? I didn’t ask anyone. I just tucked that worry inside me and carried on.

Children weren’t allowed on hospital wards in those days so I couldn’t visit, but once Pop drove me to the outside of the hospital and Mum came to a window near the top of the building and waved hard. She was just a tiny silhouette but it was reassuring to see her; she could still stand up and she could still wave. Hopefully that meant she wasn’t too sick after all.

And then, just after my ninth birthday, Mum was allowed home from hospital and I was taken over to our house to see her. She was lying on her side of the bed in her pink flannelette nightdress, so I clambered up onto Pop’s side to chat to her. There were tubes coming out of her stomach and she seemed all puffy and bloated, with pale, waxy skin. There were two bedside tables Pop had made from wood he had recovered from the bombed-out house in Hayes, and they were covered with medical paraphernalia: kidney dishes, syringes, pills and the like.

‘Are you better now, Mum?’ I asked, although I could tell by looking at her that she wasn’t.

‘No, darling,’ she said quietly, her voice all hoarse and breathy. She seemed very weak, as if talking was a big struggle.

‘Can I come back and stay at home with you?’

‘Not yet. You’re having fun at the Davidsons’, aren’t you?’ Pop was trying to sound cheerful without much success.

I looked at the Greek key pattern of the oak headboard and listened to the rasp of Mum’s breathing, trying to think of something good to say, something to make her feel better. Suddenly I had an idea. I jumped off the bed and ran round to her side of the bed, planning to give her a cuddle.

‘Careful!’ Pop said, putting out an arm to stop me, but not before I got round and saw that there was a white ceramic bucket full of dark red fluid on the floor, into which the tubes from Mum’s stomach were draining. It didn’t faze me as I’ve never been squeamish, but I had to watch not to kick it over.

‘Can I give you a hug, Mum?’ I asked. I couldn’t work out how I would get my arms around her with all those tubes in the way.

She glanced at Pop and he replied: ‘Not today, Cherryanna. Mum’s feeling a little bit sore.’

He drove me back to the Davidsons soon after and I remember feeling very subdued. Mum had looked so tired and ill, and it wasn’t like her not to give me a hug: she had always been a very tactile mum, someone who would let me climb onto her knee and snuggle up, breathing in her scent of 4711 Cologne and home baking. Now the smell around her was sharp and antiseptic and I didn’t like it at all. Nothing felt right. Even Pop seemed distracted and not his usual friendly self.

At the Davidsons, I shared a bed with Rosalind, the daughter, who was a bit younger than me. It was a big old bed with an eiderdown on top. A few days after seeing Mum at home, I woke suddenly in the middle of the night and I swear I saw Mum standing at the foot of the bed. I wasn’t afraid; I just looked at her, wondering what she was doing there.

‘Don’t worry,’ she said. ‘I’m an angel now but I’ll still watch out for you. I will always be with you.’

I’m not sure if the voice was out loud or in my head – Rosalind didn’t wake up – but I remember it very clearly, even today. Back then, in my nine-year-old’s head, I knew it meant that Mum was dead and had gone to Heaven. I wasn’t afraid of death because I went to Sunday school like all little children did in those days, and I believed in God and Jesus and angels in glowing white dresses with wings.

Mum’s angel didn’t have wings or a white dress. It was just her. It all seemed so normal that I just accepted it. She lingered at the foot of the bed for a while then faded away, and I lay awake, wondering when I would see her again and what would become of me now.

* (#ulink_55aa4867-a6d6-5b42-a60c-4a2a487c72a5) This term, which sounds racist nowadays, was in common use at the time.

2

The New Woman in Our Lives (#u86f8dd10-bbde-5163-b86a-7bfaa87f2712)

Next morning, Rosalind’s mum came into the bedroom and said, ‘You don’t need to put on your school uniform today, Cherry. Your dad’s coming to take you out for the day so wear your best clothes.’

Over breakfast, Rosalind and Donald kept staring at me in a funny way and there was none of their usual joshing. I think maybe their mum or their dad had had a word before I came downstairs, telling them to be quiet. I wondered if they knew about Mum being an angel but didn’t like to ask.

‘Would you like some jam, Cherry?’ Mr Davidson asked.

I shook my head. I didn’t feel like eating anything because my tummy was aching, but I nibbled at the edge of my toast, just the tiniest of little nibbles.

Rosalind and Donald left for school and Mrs Davidson brushed my hair for me really gently, making it all shiny and neat. When Pop arrived I put on my cherry-red Sunday-best coat instead of my school coat and followed him out to the car, his old Ford Prefect with the leather seats that I loved the smell of. We drove in silence to Gulliver’s, the florist opposite the hospital, and Pop pulled up outside, then hesitated, as if trying to work out what to say.

‘I’ve got something very sad to tell you, Cherry,’ he said at last, taking my hands in his, and I noticed that his eyes were red-rimmed. ‘Your mummy was too sick to get better and last night I’m afraid she died.’

‘Yes, I know,’ I said. ‘She came to see me and told me she’s an angel.’ I didn’t feel sad at that stage because I knew she was all right – I’d seen her with my own eyes.

He looked puzzled. ‘When was that?’

‘Last night in bed.’

He cleared his throat. ‘Anyway, we need to choose some flowers for her to hold in her coffin and I thought you might like to help me choose the prettiest ones. Will you do that?’

I nodded. We got out of the car and went into the florist, exploring the rows of big flowers and little flowers, brightly coloured and pale flowers, and in the end we decided on lily-of-the-valley because they had such a nice smell and I knew Mum had liked them.

Afterwards we went straight back to the Davidsons and Pop left me there with a hug, saying that he was very busy with all the arrangements but he would see me soon. I wasn’t allowed to go to the funeral – children didn’t go to funerals in the early fifties. I stayed at the Davidsons until the formalities were out of the way, and all that time I didn’t shed a single tear. I was quiet but just got on with my schoolwork and playing with Donald and helping Mrs Davidson in the kitchen. It was only when Pop picked me up and brought me back to our house that I realised Mum really wasn’t there – she wasn’t in the sitting room, or in her bedroom, or in the kitchen – and I began to cry. In my nine-year-old’s mind I’d somehow thought she would be, even though I knew she was an angel now. I was all muddled up.

Pop pulled me onto his lap for a hug and said, ‘You mustn’t cry, Cherryanna. You’ve got to be a very brave girl for Daddy.’

He sounded so sad that I sniffed back my snot and wiped my tears on my sleeve, swallowing the sobs in my throat. I couldn’t bear to make Pop any sadder than he already was, so I zipped the emotions inside of me and locked them away, determined not to cry any more. The words ‘you mustn’t cry’ stuck in my head, and I thought of them if I ever felt like I was going to break down, repeating them over and over to myself. ‘You mustn’t cry, you mustn’t cry.’ Pop needed me to be strong, and that’s what I would be. I wanted to look after him and help him to cope. We would stick together, he and I, the two of us together, and we’d manage just fine.

Pop had other ideas, though. He couldn’t manage to do his job at the aerodrome and look after a nine-year-old girl at the same time, so first of all he sent me off to stay with my auntie Florrie and uncle Sid, who lived near Margate. I don’t know how long I was there but it was long enough for Auntie Florrie and me to make a knitted rabbit and stuff it full of stockings. One night I couldn’t help starting to cry in bed, no matter how hard I tried not to. When Florrie came in I didn’t want her to see I was upset so I squashed that rabbit hard against my face and told her to ‘go away’. After that I went to stay with some friends of Pop’s in Ramsgate. There was a woman living with them who had been mentally disabled since falling out of a window as a child, and she spent her days winding and unwinding cotton reels, so I used to help her.

Finally, after I don’t know how long, Pop picked me up and drove me back to the house on Heath Road in Salisbury where we had lived with Mum, and it felt terribly empty without her. We took flowers to her grave and arranged them in a little crackle-glaze vase. When I looked at the mound of earth, I never believed she was in there because I knew she was an angel in Heaven. All the same, I was very upset when frost cracked the vase one week in winter and all the water spilled out and the flowers died. It seemed important to keep it looking nice for Mum.

Pop hired a succession of housekeepers to look after us, but for some reason none of them worked out. There was a couple who came to live in for a while, and I think they did their best but they couldn’t compare with my mum. Nothing they did was right. For example, I liked to crunch on the raw stump in the middle of a cabbage – Mum had always given me that bit when she was making our tea. I told the housekeeper I liked it but she misunderstood and cooked the middle bit for me, boiling it till it was soft and mushy. I didn’t tell her what she had done wrong but I couldn’t bring myself to eat it like that. It was disgusting.

Then, on Coronation Day, 2 June 1953, there was a party in our street and everyone was getting dressed up. I had a blue-and-white-check gingham dress with a full circle skirt and red ric-rac braid round the hem that Mum had made for me before she died. I really felt the bee’s knees in that dress and decided that the patriotic colours were perfect for the party. I went to school that morning then when I got back I looked for the dress and found it had been washed but not ironed, so it was all crumpled. Our housekeeper wasn’t there; I was on my own in the house. I couldn’t face going to the party with it looking like that, so I pulled out the ironing board and climbed on a chair to plug the iron into the light socket, the way I’d seen Mum do it. When it had heated up enough, I began to iron my favourite dress, but the creases wouldn’t come out. I didn’t know that some fabrics have to be dampened before ironing. I tried for ages to make it smooth and neat but it wouldn’t work and I missed Mum more than ever. She would never have let me go out in a creased dress. With her looking after me, I was always impeccably turned out, but now there was no one to help. I went to the street party in my crumpled dress, but for me the day had a shadow cast over it and it was hard to join in the fun.

Housekeepers came and went and somehow Pop and I muddled through, but I knew he was sad. He used to get depressed when Mum was still alive, and I know they once went to the doctor to talk about it. He’d been through a lot, with our house being bombed and his having a very responsible job, but I once overheard Mum saying that he was a glass half-empty person. ‘All your family are like that,’ she told him. ‘You believe that if the worst can happen, then it will happen.’ I sort of knew what she meant, even back at that age. Now I could sense that his spirits were low again simply because he was very quiet. I was quiet too; it was a silent house.

And then one day Pop brought home a tall, scary-looking woman with carefully curled dark hair and a very posh accent, whom he introduced as Billie.

‘Billie’s been living in India,’ Pop told me. ‘And now she’s back here, she’s driving ambulances.’

I gazed at her.

‘Do you know anything about India?’ she asked.

‘Isn’t that where they have tigers?’ I blushed. That’s all I could think of.

‘What’s your dog’s name?’ she asked, and I told her it was Bunty. ‘I have a bitch called Floogie,’ she said. ‘She was a stray and we found her one day when we were out in the ambulance, so I snuck her back to base and kept her.’

‘Why did you call her Floogie?’

She smiled. ‘Don’t you know the song “Flat-footed Floogie with the Floy-floy”?’ She turned to Pop. ‘It was originally “Flat-footed Floozie”, but they had to change it so the radios would play it.’ They both chuckled.

I didn’t know what a floozie was, never mind a floogie or a floy-floy, and I felt a bit left out. She and Pop seemed very friendly with one another and I didn’t like it one bit. She was smiling at me and trying to appear kind, but there was something about her I didn’t trust right from the start. I think it was because her smile didn’t reach her eyes. Maybe I knew she was only pretending to be nice and didn’t really feel it.

Over tea I learned that Billie had been married to an officer in the Indian Army but they’d got divorced. And then Pop dropped the bombshell. ‘Billie and I have some very exciting news for you,’ he said. ‘We are planning to get married so that she will be like a new mummy for you. Isn’t that nice? What’s more, you can be the bridesmaid at our wedding.’

I grimaced. Billie was nothing like my mum and I made up my mind then and there that I would certainly never call her Mum. I didn’t mind being a bridesmaid because I’d never been one before, but I worried about what their being married might entail.

‘Does that mean you’ll come to live in our house?’ I asked, and I suppose my tone of voice didn’t sound very enthusiastic.

‘Don’t be rude,’ Pop said. ‘Of course she will. We’ll all be one happy family.’

It seemed to be no time at all after they broke the news that we were all trooping off to Salisbury Registry Office, me in a short flouncy dress that stuck out at the sides, and it became official: Pop and Billie were married. They took me with them for their honeymoon in Belgium, where we stayed with friends of theirs, and I felt utterly lost and alone in the world. Pop had been my only ally and now he was lavishing all his attention on this posh woman I hardly knew. We were in a strange country, with strange people speaking a different language, and I felt completely cut off. If only I had a brother or sister, I thought. At least we’d be in this together. We could have ganged up and played tricks on her, and kept each other company.

Billie was nice to me on the honeymoon, trying to play-act at being my new mum, but on the way home we stopped at a hotel in Dover, where she decided to cut my shoulder-length hair. ‘It’s far too much trouble to look after,’ she said by way of explanation. She had been a hairdresser herself before she got married the first time, and she wielded the scissors, giving me a short crop that made me look like a boy. I gazed at my reflection in the mirror, remembering all the care Mum had lavished on my hair, and I knew things were only going to get worse from here on in.

3

My Closest Friend, Grizelda the Goat (#ulink_e4c3d704-f8a2-53d8-a636-db93426ea355)

At first Billie’s influence was just felt in terms of strictness about the way she ran the household. She was constantly chiding me to speak ‘properly’ and adopt a posh accent like hers instead of the Wiltshire one of my schoolmates; I wasn’t allowed to mix with anyone she didn’t consider to be of ‘our class’; and at seven shillings a week she decided that my riding lessons were far too expensive and had to be stopped. I was distraught about this and begged her to reconsider, but she said things like ‘needs must’ and ‘don’t be a spoiled little girl’, which meant there was no room for discussion.

Before long I was constantly on edge, waiting to be told what I had done wrong, and Pop never intervened to support me; he was a gentle, go-with-the-flow person who was soon totally under Billie’s thumb. We hardly had any time alone together anymore because he was out at work during the day, and when he came home Billie was there. I remember once he took me to the airfield at Boscombe Down, and I was allowed to climb into the cockpit of Fairey Delta 2, a new plane that had just broken the world speed record. It had a long pointy nose and was very narrow. Inside, I sat in the pilot’s seat, holding onto the steering column and looking at the figures on all the dials; one of these dials had recorded the speed of 1,132 miles per hour that it had achieved to break the record. I tried to imagine what it must have felt like to be in the pilot’s seat then as the world whizzed past. That was a pretty special treat.

After I showed an interest in Fairey Delta 2, Dad told me about the rickety little planes he used to work on in the First World War. ‘Like string bags made out of balsa wood and cloth treated with dope,’ he said, which made them terrible fire hazards. He’d been a Flight Sergeant with 56 Squadron and had fitted out planes in France, then when the war ended he’d gone on a goodwill flight to South Africa with dozens of stops along the way – he showed me them on the map. After that he went out to work on planes in India for a couple of years. I was in awe of this. It seemed terribly glamorous to be an aeroplane fitter back in the days when aviation was in its infancy.

Sometimes Pop would sneak into my bedroom and wake me in the middle of the night if there was a nightingale singing outside, or if there was a particularly dramatic thunderstorm he thought I’d like to watch. We were both fans of thunder and lightning. But otherwise Billie was always around and always criticising both of us.

With Pop, her main complaint was that he didn’t earn enough money to keep her in the style to which she had become accustomed in India. Our Salisbury home was a perfectly nice semi-detached house with a beautiful garden, but Billie wanted something grander where she could be a lady of the manor. She persuaded Pop to buy Glebe House in West Lavington, a gorgeous old property which was actually three cottages knocked into one. It stood in three-quarters of an acre of garden with a trout stream running through it. I think this was a stretch for them to afford because Billie insisted that I paid for my own bedroom with the £200 Mum had left me in her will, which was in a building society account in my name.

I liked the West Lavington house, especially after Billie got a goat, which we kept in a shed in the garden. I became very close to that goat, who was named Grizelda. I never talked about my emotions to any human beings – I saw it as a sign of weakness now, something that could be used against me – but I always found solace in animals, and Grizelda was an exceptionally good listener. Every day, when I got home from school, I’d take out the vegetable peelings for her and sit telling her about my day: I’d talk about any girls who’d been mean to me, or teachers who were cross, or complain about the amount of homework we had. Grizelda would munch on her carrot tops, regarding me with a wise expression, then bend her head for me to scratch it. She genuinely was my best friend and confidante through those early teenage years.

I did try to make other friends. Someone told me about a youth club in West Lavington, something to do with the Methodist church, where you could play games and hang out with other kids the same age. Surely Billie would let me join that? It was local so I could walk there myself.

‘We will both go along together,’ she ruled when I told her about it. ‘I will judge whether or not it is suitable.’

I imagined her charging in, wearing her fur coat and full make-up, turning up her nose at the club, announcing that they were the ‘wrong sort of people’, while I tried to hide behind her in my embarrassment. Cringing, I said, ‘No, I’ve changed my mind. I don’t think I’ll bother after all.’

I hadn’t forgotten my love of horses, and I found that if I turned up at the local stables every weekend to muck out, they let me have a ride every now and then. There was a field of horses very near our house and sometimes I would sneak out with a halter I’d made out of string and ride around on one of them. I was never happier than when I was out on horseback with the wind in my hair. When you’re out there on a horse, you have to be able to deal with whatever happens, and I was learning a lot about being self-sufficient. I was getting good at it.

After leaving Devizes Road Primary I attended Devizes Grammar School, a co-ed some distance away from home. Every morning I had to catch a bus then walk a mile and a half, which inevitably got me there late, doing the same on the way home. It was difficult to make friends since I lived so far from school and wasn’t allowed to invite anyone home, or to take part in after-school activities. Billie had other plans for me: unpaid housework. I did the washing, the ironing, the cleaning, fed the dogs, prepared the vegetables for dinner every evening and washed up afterwards. I guess she’d had servants to do all these things in India, and in West Lavington I became the substitute punkah-wallah.

Soon I began to rebel, and we clashed bitterly. I was distraught when I came home from school one day to find that Billie had retrieved my old doll’s house from the attic, driven a stake through it and turned it into a bird table in the garden.

‘What are you so upset about?’ she asked. ‘You didn’t play with it anymore.’

‘I wanted to keep it. It was my special thing that Pop made me. How could you destroy it?’

‘At least it’s doing some good now instead of just taking up space.’ She failed to understand its emotional significance, and when I told Pop that evening he just shrugged and sighed and opened his paper. He’d do anything to avoid a fight.

Billie didn’t ever beat me but she locked me in my bedroom as punishment for misdemeanours, not realising that I could slither through the bars at the window and jump down onto the roof of the goat shed below. I suppose in retrospect I was a bit of a rebel.

One flashpoint was clothes: whereas my mum had bought me a new coat and new shoes every year because I was a ‘growing girl’, Billie complained about the cost of things. She would never buy me the correct school uniform, instead sending me to school in a hotch-potch of garments, for which the teachers told me off. My out-of-school clothes were all frumpy hand-me-downs from Billie’s sister, which Billie insisted that I ‘make do with and mend’. When I complained, she retorted, ‘What do you want nice clothes for? You’ve got a face like a spade.’

One of our worst fights came after I got home from school one day to find that Grizelda was gone.

‘Where is she?’ I screamed. ‘What have you done with Grizelda?’

‘She got on my nerves, eating everything in the garden,’ Billie said, ‘so I gave her away to a farmer.’

‘Which farmer? Where is she?’ I wouldn’t stop my persistent questioning until Billie gave in and told me where Grizelda had been rehomed, then I charged out of the house and walked all the way there. When Grizelda saw me she got so excited she tried to leap over the fence. I hugged her and cried, but had no choice but to leave her there when it was time to go home again. I missed her terribly after that.

When I asked, in typical teenage fashion, ‘What about me? Don’t my feelings come into it?’ Billie replied, crushingly: ‘You? You’re less than a grain of sand in the universe.’

Only once did Pop stand up for me in a fight with Billie. We were in the car and I was begging her to buy me some summer stockings rather than the awful 60-denier nylon pair I was supposed to make last for an entire school year. ‘Who do you think you are? Lady Muck?’ Billie rebuked. ‘We’re not made of money, you know.’ Suddenly, Pop screeched the car to a halt and yelled, ‘You will not treat her like that. Get out of the car!’ There was a blazing row, but for once he stood his ground and made Billie walk the three miles home.

When I was around fourteen, Pop was made redundant from his job as representative of Fairey Aviation when they closed down that branch of the aircraft testing site at Boscombe Down. He could have retired at that stage, but Billie persuaded him that they wouldn’t have enough money to live on from his pension. She had very expensive tastes, particularly in home décor, constantly changing our carpets, curtains and upholstery for the latest shades and styles. She insisted that Pop went back to work in the aerodrome storeroom, which was a huge climb-down for someone who had been in charge, and I could tell he hated it. We downsized to a house in Amesbury, Wiltshire, and I moved to the South Wilts Grammar School for Girls for my third year onwards.

The overwhelming feeling in my teens was loneliness and isolation. My contemporaries in the late fifties and early sixties were listening to pop music, wearing the latest fashions and going to dances where live bands played, but I had no social life except accompanying Pop and Billie to evenings spent playing cards with their friends. Every day after school my classmates hung out in the Red Cockerel coffee shop, chatting to boys and having a laugh. I yearned to join them but my pocket money was all taken up paying for school lunches, and besides, I’d have been in big trouble if I missed the bus home. I sat in the window seat of the bus watching them all clustered round a table in the Red Cockerel and felt like an alien species. It was such a lonely feeling.

In the early years of their marriage they had talked, tantalisingly, about adopting a child because Billie couldn’t have any of her own, and she said she’d always wanted to have a son. They made enquiries but Billie found the adoption agency’s assessment procedures rude and intrusive.

‘These flipping people, they want to come and inspect our house and ask all sorts of personal questions about us, and they haven’t even let me see what kind of child they might have available. I’m not putting up with this!’ she exclaimed.

My chance of gaining an ally, someone I could be close to, were dashed. After that my only hope was escape, to start a life of my own somewhere I could make my own choices and determine my own fate.

4

A Hasty Marriage (#ulink_941ed2d0-b7bc-5719-8bdf-523a722e0132)

I passed two A Levels in sixth form and hoped to study agriculture at college, to pursue my love of animals. Billie objected to this plan, though – ‘It’s no career for a young lady’ – and instead I was signed up to study horticulture at Nottingham, which she deemed more fitting. That summer Dad and Billie moved to Deal in Kent (he had finally retired completely from the aerodrome), and it was while we were living there that Billie decided to become a Jehovah’s Witness.

She had always had her religious fads: there was a spiritualism phase, then a faith-healing phase to help ease the arthritis she suffered from, but the Jehovah’s Witness phase was the worst of all. She was obsessive about reading The Watchtower and going out to try to convert our neighbours, which was a total embarrassment. She banged on about modesty and virtue, railing against drunkenness and promiscuity, gambling and tobacco, and it was like listening to a record with the needle stuck in a groove. I don’t know how Pop put up with it; all I could do was leave home.

It was a requirement of my horticulture course that I completed a year’s practical work, so I managed to get a job at Mount Nurseries in Canterbury where my life became fun for the first time since Mum died. I moved into digs, and soon I’d made loads of friends among the other staff at the nursery. We all went to the pub together in the evenings after work. There were a few boyfriends, nothing serious, and fun social events almost every night of the week. I felt as though I’d been let out of jail! I was skint most of the time because there was hardly anything left of my wages after the fifteen shillings a week I paid for board and lodgings, but I was having the time of my life.

At first I got the bus home every weekend to visit Billie and Pop, but the final straw in my relationship with my stepmother came over a cucumber sandwich, of all things. I’d travelled home and was hungry when I arrived, so I went into the kitchen to make said sandwich.

‘What do you think you are doing? You eat far too much!’ Billie snapped.

I looked at her, buttery knife poised in my hand in mid-air, and simply thought, ‘I don’t want this anymore.’ I’d been shoved down by her all through my teens, and now that I was starting to pull myself up I refused to be squashed any more.

I put down the knife, left the sandwich behind on the countertop, walked out the door and never went back to that house again. From then on, Pop had to travel to Canterbury to see me – and, bless him, he did come regularly, although he admitted that it made things ‘a bit tricky’ with Billie. (She later accused him of having an affair with my landlady simply because he put up a kitchen cupboard for her!)

Now that I was my own boss I decided not to study horticulture after all because going to university would have meant I’d still be partly financially dependent on Pop and Billie, and I didn’t want any further involvement with that woman. Instead, I looked for jobs in the newspaper and finally decided to apply to study radiography at Canterbury Hospital, where you could train in-house. I was lucky to be accepted by the lugubrious consultant radiologist Dr Johnson, even though I didn’t have A Level Maths, and I enjoyed hospital life straight away.

It was around this time that I was introduced by a mutual friend to a man named Eric. He was quite a bit older than me, had been a professional footballer and was now practising as a chiropodist in a surgery near my digs. I thought nothing of it when my friend introduced us, but soon I noticed that Eric always seemed to be standing outside when I walked past and would call me over for a chat. One day he invited me to accompany him to a cricket match in which he was playing, so I went along and somehow we just fell into being boyfriend and girlfriend.

There was no great romance. I felt a sense of security with him because he knew more than me about the way the world worked, he was qualified and had a good career, and he seemed to have his whole life planned out. I was still only nineteen years old and, although I didn’t regret the decision to stop having any contact with Billie, I felt very alone in the world, with no one to fall back on should things go wrong. That’s where Eric came in. I thought he would look after me, so two years later when he asked me if I wanted to get engaged, I just said yes. He bought me a diamond ring from an antique shop – quite a decent diamond, it was – which cost £21 (a substantial amount in those days).

In the mid-sixties, late teens to early twenties was the normal age for girls to get married – leave it too late and people described you as being ‘on the shelf’ – and I thought I’d better not miss my chance. The landlady at my digs tried to talk me out of it. ‘Are you sure you’re doing the right thing?’ she asked. ‘He’s quite a lot older than you.’ But my mind was made up simply because, to me, marriage to Eric would mean security. It’s what girls my age did.

Pop came alone to the registry office ceremony in September 1964. I’d bought myself a blue dress, jacket, hat and a pair of shoes in a charity shop, all for three pounds, and my landlady took some photographs in which I look about fifty years old! Standing in front of the registrar, I got my first shock of married life when Eric was asked for his date of birth. As he gave it, I did the arithmetic in my head and realised that he was five years older than I’d thought: thirty-three rather than twenty-eight, making him twelve years my senior. I didn’t say anything, though. I looked at him open-mouthed but didn’t like to make a fuss.

We went for lunch in the Falstaff Hotel in Canterbury – Pop, his sister Blanche, Eric and me. Eric’s family lived in Doncaster and couldn’t travel down for the wedding. Immediately after lunch, Eric and I walked back up the road to strip wallpaper in a house we’d just bought and were doing up. There was no honeymoon; it was straight down to the business of being ‘a married couple’.

Ours was a typical 1950s marriage, a decade too late; although women across the nation were starting to burn their bras, there was certainly none of your Women’s Lib in our household! I did all the shopping, cooking and cleaning while carrying on with my radiography studies, and Eric worked in his chiropody practice during the day then played golf and cricket with his mates in the evening and at weekends.

My weak spot was that I desperately wanted a family, to find somewhere I belonged. When I visited friends’ families I used to analyse the dynamics, trying to figure out how they worked, because family life was something I hadn’t experienced since Mum died. I yearned for lots of children to make a big happy gang in which I was a core member, so I mucked in and cooked and cleaned and did my absolute best to make my marriage a success.

All the same, I remember one moment, a few weeks after the wedding, when I was in a little room at the hospital where I was training. There was a brown rug on the floor, and I stared at it and thought, ‘What have I done?’ Although I’d been dating Eric for two years, agreeing to marry him had been impulsive; it had seemed like something I should do rather than something I wanted to do, and now the reality of the decades stretching in front of me seemed daunting. There was nothing to be done about it, though, so I just snapped myself out of that introspective mood and got on with things.

Soon after the wedding, Pop came to visit, bringing with him a folder of papers. He handed them over, saying, ‘I thought it’s about time you should have these.’

I opened the folder and flicked through. There was a lengthy correspondence with Reginald Johnson & Co Solicitors in Hayes, Middlesex, regarding ‘The Adoption of Paulette’ – and I realised with a start that it was all about me. For some reason my heart started to pound.

It seemed that although I had been born in March 1943 and had gone to live with Mum and Pop (Dorothy and Ernest Vousden) six weeks later, I had not been officially adopted by them until March 1944 because my birth father had been in the army and they hadn’t been able to track him down to get his signature on the paperwork. There was a copy of a sad little letter on blue writing paper from my mum to my birth father, sent care of his unit: ‘We are anxious to adopt her but cannot do so without your written consent, would you kindly do this without further delay & so enable us to get the matters settled.’

It struck me immediately how heart-rending it must have been for Mum and Pop to bring me up for a whole year – doing the nappies and the night feeds, bathing and dressing me – while, at any time, my birth parents could have come to claim me back because the adoption was not formalised. That must have been very stressful for them. How could you let yourself love a baby you might not be able to keep? Yet there was no doubt that Mum and Pop had loved me without reservation from the minute they took me home with them.

‘We were pretty sure they wouldn’t come back for you,’ Pop agreed, ‘but it was certainly a relief when it was all finalised. Your mother and I had been trying for a long time for a baby – since our marriage in 1922 – so as you can imagine we couldn’t wait to have it all confirmed legally.’

‘Twenty-one years!’ I exclaimed. ‘That must have been so hard for you.’

‘It was a particular sorrow for your mother. I had my work but she just had her home to run, and I think she felt it very keenly when friends were talking about their children’s achievements. Thank God she had the nine years of looking after you. It made her so happy.’

I smiled, remembering what a wonderful mother she had been. I was very lucky in that sense … not so much in others.

Next I looked at the four-page certificate that legally made me the child of Dorothy and Ernest Vousden under the 1926 Adoption of Children Act. On the third page, in black and white, there were the names of my birth mother and father: Daisy Louise Noël of Shelburne Road, High Wycombe, and Henri Le Gresley Noël of Saighton Camp, near Chester. I got goosebumps on my arms looking at them.

‘Why do their names sound so foreign?’ I asked.

‘They were from Jersey,’ Pop explained. ‘Daisy was evacuated in 1940 when the Germans were about to invade the Channel Islands. Henri was in the army. I believe their marriage failed and she didn’t feel capable of raising a child on her own, especially during wartime.’

‘Poor Daisy,’ I said, trying to imagine what it must be like to give up your baby. I pictured her in floods of tears as she handed over the bundle swathed in a pristine white blanket.

The last page of the certificate was about wills; it explained that adopted children bore all the same rights as children born naturally to a couple, except that they would not automatically inherit any estate unless there was a will naming them as heirs.

‘Don’t worry; you are named as my heir,’ Pop said. ‘Not that there’s much to inherit.’

He looked tired, and I’d noticed he was getting forgetful. When I was younger I’d never minded having older parents, but now I was in my twenties, Dad was in his sixties and starting to succumb to the niggling ailments of old age.

‘Thanks for bringing these, Pop,’ I said. I couldn’t stop looking at those names – Daisy and Henri Le Gresley Noël. What ages would they be now and what were they doing with their lives?

And then a thought struck me: perhaps they had gone on to remarry and have more children. I might have half-brothers and sisters somewhere. Wouldn’t that be lovely! I daydreamed about discovering a big extended family of cousins and aunties, grandparents, nephews and nieces, who all met up for Christmases and birthdays and weddings. Then I snapped myself out of it. I still had a wonderful dad, and I’d once had the best mum in the world; lots of people couldn’t say as much. I should count myself lucky and not hanker after anything more.

5

Learning to Be a Mum (#ulink_658058f8-3524-5ddd-b158-729ed440bdbd)

It was fascinating to learn that my birth parents came from Jersey, meaning that I had a connection with the Channel Islands. I knew very little about the wartime occupation there, but I went to the library and did some reading to try to understand what the people had been through. I read that after the Fall of France in June 1940 and its occupation by German troops, the British government decided they couldn’t spare the manpower to defend the islands, which were much closer to France than they were to Britain. Everyone was aware that it would give the Germans a propaganda coup to say they had conquered part of the British Isles, but there would be no particular strategic advantages for them in having a base there and the islands would simply be too tricky for the British Army to defend.

Each island had its own governing body, and in those rushed, chaotic days of mid-June 1940 they all adopted different policies towards evacuation. Alderney officials recommended that everyone be evacuated; Sark urged everyone to stay; on Guernsey they decided to evacuate all school-age children; on Jersey the advice was to stay, and most followed it, with only around a tenth of the population deciding to leave – including, I supposed, my birth mother. Boats left the islands for the UK mainland between 20 and 23 June 1940, and the Germans took possession on 1 July, so it was all a big rush. I looked at photographs of old women sobbing as they waved at departing boats, of little children perched on their fathers’ shoulders looking bewildered, of decks crammed with people looking fearful, unsure of what awaited them on the mainland. It must have been a terrifying choice: wait for the Germans or leap into the unknown and start a new life.

By the time I was born, my mother, Daisy, was in England and my father was off fighting somewhere. According to the adoption certificate her address was in Shelburne Road, High Wycombe. I knew High Wycombe because my Auntie Wyn (Mum’s sister) and Uncle Frank used to live there. I remembered their next-door neighbours kept chickens and goats in a big uncultivated garden, and I liked to climb over and play with them even though Aunt Wyn kept telling me not to.

‘Stay out, Cherry. You’ll annoy them,’ she chided. But I had always loved goats and I was straight over that fence whenever she wasn’t looking, even after one of the goats butted me and knocked me to the ground.

I wondered if an adoption agency had given me to my mum and dad – the adoption papers didn’t name one. Alternatively, perhaps Auntie Wyn had known Daisy and told her about this couple who couldn’t have children of their own and were desperate to adopt. Was that how it all happened?

For a brief moment I considered writing to the Shelburne Road address to ask if the current occupants had a forwarding address for Daisy, but then I changed my mind. I felt sure Pop would be upset if I tried to contact my birth parents. It was almost like saying that he wasn’t a good enough dad. I couldn’t do that to him, and I certainly didn’t want to do it behind his back, so I put the adoption papers away in a drawer.

Meanwhile, Eric and I were keen to start a family of our own. In the spring of 1965 I had a miscarriage, which was very distressing, but luckily by the end of the year I was pregnant again. I gave birth to my daughter Helen in April 1966, and it was then that I realised I knew absolutely nothing about babies! I’d had no contact with them, and while most girls could ask their mothers for help and advice, I had no one to ask and simply had to muddle through. For example, I didn’t know that your milk doesn’t come in for three days; I had no idea what to do when Helen was obviously hungry and I had hardly anything in my breasts to feed her. (I’d decided from the start that I wanted to breastfeed, even though it wasn’t the fashion at the time, because to me it felt more natural. That’s what we have breasts for, isn’t it?)

There was no one you could ask in those days. I’d met a few women at antenatal classes and we exchanged notes, but they were mostly young and clueless like me. I felt a complete amateur but somehow I managed to master breast-feeding, then weaning her on mashed bananas and stewed apples. There was endless hand-washing of terry towelling nappies in a sink down in the basement then struggling to get them dry because there was no heating in the house. When my son Graham came along in December 1967, I was an old hand at rearing babies and it all went more smoothly, although there were double the number of nappies to wash.

Our house in Canterbury was a Victorian building, four storeys tall. On the ground floor was the surgery and waiting room for Eric’s chiropody practice. I had to share the only bathroom, on the first floor, with all the old ladies who’d come in to have their feet done, and I hated that. The kitchen was on the same level as the surgery, and our sitting/dining room was on the top floor so if we sat down to dinner and I realised I’d forgotten the salt, it was a trek down four flights of stairs to retrieve it then another four flights back up again. It obviously wasn’t an ideal house in which to live with two babies; when I arrived home with a pram, several bags of shopping and the two of them wailing for a feed, there was many a time I could have done with an extra pair of arms.

I had loads of memories of my own mum – how warm and cuddly she had been, the feeling of safety when I was snuggling on her lap and the peacefulness of lying in bed, tucked under the covers, while she played the piano to lull me to sleep. I wasn’t very good at doing these things for my own children, though. I did all the physical, practical things – feeding, washing, clothing, nursing them when they were sick, taking them for dental check-ups and registering them for schools – but emotionally I felt shut off. I think it went back to the first time I returned to the house after Mum’s death, when I was sitting on Pop’s knee and he told me not to cry but to be a brave girl. In everything that had happened to me since then, I’d suppressed my emotions and simply coped, so when it came to my own children I found I was unable to be demonstrative and loving. We weren’t a cuddly family, although I loved them to pieces.

Apart from anything else, I was always short of time. Eric liked his routines: breakfast on the table at eight, lunch at twelve, supper at six, so looking after the kids had to fit around that. I had finished my radiography course before getting pregnant, but there was no part-time radiography work in our area, so instead I took odd jobs to make money. In summer I’d be out fruit-picking while the kids snoozed in their prams or toddled around trying to help; in winter I made teddy bears for a market stall, stuffing them, sewing them up and sticking in those eerie glass eyes.

Eric gave me housekeeping money (when we first married it was four shillings a week) but it was a struggle to feed and clothe all of us. I economised where I could, only buying my own clothes from charity shops. Once, Eric and I were invited to a posh do at the golf club and I bought a second-hand gold brocade dress, full-length and fitted, from Oxfam; I was quite pleased with it but he complained: ‘What if we get there and someone else recognises it as theirs?’ Fortunately they didn’t – or at least if they did, they were too polite to say.

Life was one big juggling act of housework, childcare, trying to earn money, and marriage to a man who had old-fashioned ideas about a woman’s role. Mostly I was too submissive to kick up a fuss.

6

Breaking Out of Domesticity (#ulink_a88276a7-dc26-55ce-a650-a13e82509d67)

Little by little, bit by bit, I began to lift myself out of the role of domestic skivvy and stay-at-home mum. Once the children started school, I signed myself up for a correspondence course in chiropody. Eric approved, because it would mean I could help with some of the home visits needed in his practice, travelling out on my bicycle to see clients who were unable to attend the surgery.

When I’d qualified as a chiropodist and was earning some decent sums of money on my own account, I could supplement the housekeeping. Helen was doing dance classes, which she loved, and there were always extras she needed for the regular shows. Now I could buy these and I could pay for Graham to take riding lessons at the local stables. I began to put my foot down about certain things around the house as well. In particular, I’d always wanted a washing machine but Eric didn’t see the need: ‘My mother managed perfectly well without a washing machine so why can’t you?’

Instead of arguing I saved the money from my wages then slipped into the Co-op in town and chose a modest Indesit automatic, giving strict instructions that it was not to be delivered until the following day, which would give me enough time to prepare Eric for the arrival.

Imagine my horror when I arrived home to find some men already unloading the machine from the back of a van and trundling it noisily towards our front steps!

‘No, not that way!’ I cried. ‘Quick – come round the back.’

They installed the washing machine in the basement and, after a spot of grumbling, Eric accepted it once it was there. This gave me the idea of having a fitted kitchen installed while he was off on a golfing holiday. He could hardly rip it out again once it was in place, I reckoned (although he did complain that it was a shocking waste of money!).

These little bits of progress gave me confidence. With each tiny step forwards, my life was becoming a bit easier. With the children both at school, I had some hours free and my day wasn’t complete drudgery from morning to night. My next purchase was a huge secret, one I knew that Eric would never have consented to in a million years: I bought myself a horse.

It had been one of my childhood dreams to own a horse, and there was a field down by the river in Canterbury where I used to stop and pet the horses. I got talking to the old chap there and he told me he was looking to loan one of his horses, a thoroughbred named Ferica, for four pounds a week. Straight away I agreed to take it on, then a while later I bought a sorry-looking four-year-old called Copper at a horse fair in Ashford, only to find out later that it was a par-bred American quarter horse. I still don’t know how I got away with rushing out to groom, feed and ride the horses every day; I just got on my bike and went, and Eric never asked questions. It was a huge deception but I loved my horses to pieces and they brought me a lot of happy times. I finally had to confess to Eric a couple of years later, after I arrived home splattered from head to foot in mud, and he was utterly speechless, too gobsmacked even to protest.

Later still I took driving lessons. Eric didn’t drive and wasn’t keen on me learning, but I persevered and, after I passed the test, managed to buy myself a beat-up old car, a pale blue Singer Chamois, which cost £120. It was a lovely car with a walnut dashboard, but sadly it got written off a few years later when an uninsured student drove into me on a country road. I liked the independence driving brought, but for local journeys I’d always use my trusty old bike.

Still I found it difficult to show affection for my children. I’d have fought to the death to protect either of them, and I worked my socks off to buy whatever material things they needed, but I was such a squashed, bruised apple of a person that I was incapable of hugging them or telling them that I loved them. I’d do the chores instead of taking them to the park, accept extra bookings at work instead of having a day out at a fun fair, and I bitterly regret that now. You’d think losing my mum would have made me extra loving towards my own children, but with me it worked in quite the opposite way, making me cautious and reserved. It was a loss for them, and a loss for me too because I missed the chance to enjoy being a mum.

In 1975, I read a story in the newspapers that made me prick up my ears. Under a new law, adopted people had the right to apply for their birth certificates and seek information about the agency involved in their adoption, with a view to tracking down their birth parents. I still didn’t plan to track down Daisy and Henri Noël because I didn’t want to hurt Pop’s feelings, but I thought I should apply for a copy of my birth certificate. Apart from anything else, I thought I’d need it if I ever wanted to get a passport. You had to have counselling first, so I made an appointment and went along on the day to find a young, wet-behind-the-ears lad sitting behind a big desk, looking rather embarrassed by the role in which he found himself.

‘Do you think you are prepared for this?’ he asked, peering at a form in front of him.

‘Yes,’ I replied. My heart was pounding, but I didn’t want to tell this lad I was nervous and have to listen to him spouting counselling clichés he’d memorised from a textbook.

‘Are you sure?’

‘Yeah.’

He opened a file, pulled out the certificate and passed it over, saying, ‘Here you are, then.’ So much for counselling!

I don’t know why I’d been nervous. The long, horizontal sheet didn’t give me much information that I hadn’t already gleaned from my adoption certificate, but I did learn that my birth mother’s maiden name was Daisy Louise Banks and that she came from Bellozanne Valley in Jersey, that my father’s occupation was itinerant farm worker and that he’d grown up in Ville à l’Evêque, Jersey. I now had addresses where they had lived at some stage, and once again I vaguely considered sending out tentative letters to make contact. I did try writing to the army authorities, trying to find out about my birth father’s military career, but my letters got passed from one department to the next without bringing any solid information. I wanted to know about Daisy and Henri, but I decided it wasn’t fair on Pop to try to get in contact with them directly.

Pop and Billie had just moved up to Scarborough, her home town, and he was becoming increasingly forgetful. We wrote to each other but often his letters contained non sequiturs or things that simply didn’t make sense. When I phoned, it was always Billie who answered, and if she passed the phone to him he frequently seemed confused. Even if I’d felt I could ask him questions about my birth parents, he probably wouldn’t have been able to answer them now. I’d missed my chance to ask whether he ever met Daisy Banks Noël, and whether she had been introduced to them by Auntie Wyn and Uncle Frank.

One day, I remembered that Pop had once given me a Jersey half-sovereign and told me he had dug it up in the garden. It was gold and glittery, like buried pirate treasure, and I’d kept it in his collar stud box. Suddenly, I began to wonder if that had been a parting gift from either Daisy or Henri as they said goodbye to their baby daughter. (Actually, I wasn’t sure whether Henri had ever set eyes on me or if he was away at the front when I was born. That seems more likely, because had he been around he could have signed those adoption papers straight away and saved Mum and Pop a year of heartache and worry.)

I tried asking Pop about the half-sovereign but he just looked blank, his memory being stolen bit by bit by the ravages of what was later diagnosed as dementia.

7

Searching for My Birth Father (#ulink_cd1e30f1-71a6-5bf5-bc04-9c864f6c974a)

One morning in the early 1980s, I was browsing through the local paper at the kitchen table when my eye was caught by an article about how to trace your family. They had interviewed an amateur genealogist called John Stroud about methods he used to find missing relatives and draw up family trees. He used local history libraries, newspaper archives, church records and the official registers of births, marriages and deaths, and had achieved some notable successes in reuniting family members who hadn’t seen each other for years.

I tore the page out of the paper and slipped it in my pocket because I was rushing out to the horses and didn’t want to risk Eric throwing the paper away before I got back. Later on, I reread the article. Mr Stroud sounded very approachable and I decided to write to him, care of the paper, to see if he could find out anything about my birth family. Still, I just wanted information. In particular, I wondered if Daisy and Henri Noël had remarried and I might have half-brothers or sisters somewhere.

A week later I got a reply from Mr Stroud saying he would be happy to help me trace my birth parents. He asked for copies of my adoption documents and my birth certificate. I’d asked what fee he would charge for helping me, but he replied that he wouldn’t charge me anything. Genealogy was a hobby for him. I made the copies and sent them to him in the very next post, feeling both excited and nervous at the same time. I hadn’t thought through what I would do if he did find them, but I desperately hoped we would be able to form some kind of relationship. Pop’s health was declining and there was no need for him to find out what I was doing, so it couldn’t hurt him.

John Stroud did his best, He wrote that his daughter had personally gone in to the Register Office in London to do a search for them but hadn’t been able to find anything. Since we didn’t know their dates of birth, it was like looking for a needle in a haystack. None of his other searches had turned up any leads and he wrote: ‘The trouble is that all the information you’ve given me about Daisy and Henri is almost forty years out of date. After that length of time it’s not surprising if you can’t find any neighbours who remember them, and I wouldn’t expect anyone to have forwarding addresses for them. We’ll keep trying though, Cherry.’

He was a lovely man who always broke bad news to me in the most sensitive ways, remaining cheerful and positive throughout. However, after several weeks of dead ends, we agreed there was nowhere else to go at the UK end.

Meanwhile, I’d had another idea. Both Daisy and Henri had been born in Jersey, as far as I knew, so perhaps I would have more luck if I wrote to the Register Office in St Helier. I sent a request for their birth certificates, along with a cheque, and it was such a long time before I heard anything more that I had all but given up hope by the time a long, official-looking envelope plopped through the letterbox. I opened it and found a birth certificate inside. With great excitement I realised it was for my father, Henri Le Gresley Noël. According to this piece of paper, he was the son of Philippe Noël, a labourer, and Louisa Mary Ann Le Breton in the parish of Trinity in Jersey. His birthday was 4 January 1913. It was now 1982, which meant he was sixty-nine years old and there was a good chance he was still alive. I crossed my fingers that he would be.

Now that I had my biological father’s date of birth, I was able to apply to the British Register Office again to see if they had any marriage certificates in his name. At least he had an unusual name, and the chances of getting the wrong person were slight. He and my mother had separated by the time I was born in 1943, when he was thirty years old. Surely he would have remarried in the last thirty-nine years? And surely there was a good chance he had had more children?

It seemed to take ages before another certificate arrived, telling me that he had married a woman called Dora in 1964 and that they had lived in Cardiff. There was an address in St Mellons, a district in the northeast of the city.

Now for the moment of truth. I had a chance to get in touch with my birth father, but what on earth would I say? Who was he, anyway? Why had he split up with my birth mother? Why hadn’t he wanted me? There were so many questions I needed answers to and the only thing for it was to write.

I kept my letter very short and factual, just asking if he had been married to Daisy Banks from Jersey and saying that, if so, I thought I might be his daughter. I told him I had been adopted in April 1943 by a lovely couple, Dorothy and Ernest Vousden and that I was now married with two children of my own, but that I was curious to find out about his side of the family and would be very grateful if he was willing to enter into a correspondence with me. I addressed the envelope, licked the stamp and went out to the postbox. I hesitated for a minute, holding the envelope in the slot but not letting it go. And then I relaxed my fingers and heard the plop as it hit the other mail piled at the bottom. Now for the waiting.

In fact, it didn’t take very long before I heard back. Somehow I knew from the unfamiliar handwriting on the envelope that it was a reply to my letter, and I ripped it open to find a small sheet of beige paper covered on both sides in curly writing in blue Biro.

‘Dear Paulette

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».