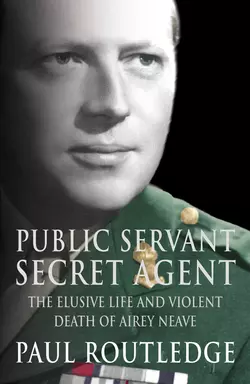

Public Servant, Secret Agent: The elusive life and violent death of Airey Neave

Paul Routledge

The first biography of Airey Neave, Colditz escapee, MI6 officer, mastermind of Margaret Thatcher’s leadership campaign and on the verge of being her first Secretary of State for Northern Ireland when he was brutally murdered in the palace of Westminster by the INLA.On 30 March 1979 for the first time in more than 100 years an MP was killed by a car bomb in the precincts of the House of Commons. Airey Neave was a loyal Tory backbencher who had last held ministerial office in 1959. What, then, had he done to deserve such a vicious and bloody attack?Public Servant, Secret Agent tells the thrilling tale of Neave's escape from Colditz, his involvement with the secret services and his shadowy role at the right of the Conservative party. With new information about the mysterious circumstances surrounding Neave's death, Paul Routledge has written a captivating and revealing life of a man who was the ghost in the establishment.

PUBLIC

SERVANT,

SECRET

AGENT

The Elusive Life and Violent Death of Airey Neave

Paul Routledge

Contents

Cover (#u5ab5c012-06ce-56bb-ae55-dc9208f498e1)

Title Page (#ubc60f8d1-3e0b-53dd-8026-76190a841d1c)

Preface (#u144c2e72-c323-517c-9226-e9e6de26fdd3)

1 The Price of Liberty (#ub609ad2c-4149-5e1b-a7ef-27aefbc526aa)

2 Origins (#uf2ba7269-2d8d-5cd2-951e-53b6b2ec066e)

3 King and Country (#u4a7d7307-37f1-5b85-85a9-5cc6ac81f2d2)

4 Capture (#u36409f6a-802b-56b8-91e4-96a1d5a51bf0)

5 Colditz (#u6c5812bd-2749-5cf5-90d6-051e546a24a6)

6 Escape (#u4c645960-a0cc-5ea5-aca7-9dc0a0f7c39e)

7 Operation Ratline (#litres_trial_promo)

8 Secret Service Beckons (#litres_trial_promo)

9 Enemy Territory (#litres_trial_promo)

10 Nuremberg (#litres_trial_promo)

11 Lawyer Candidate (#litres_trial_promo)

12 The Greasy Pole (#litres_trial_promo)

13 Locust Years (#litres_trial_promo)

14 A Very Spooky Coup (#litres_trial_promo)

15 In the Shadows (#litres_trial_promo)

16 Plotting the Kill (#litres_trial_promo)

17 Pursuit and Retribution (#litres_trial_promo)

18 The End of the Trail (#litres_trial_promo)

References (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Other Works (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Preface (#ulink_0aedb2b2-5296-5205-9f72-b4e86b51ac7b)

A gun lay unobtrusively on the settee beside my polite host, and the heavily-built man sitting on an armchair in the corner wore a tight-fitting black mask with tiny holes for his eyes and mouth. He was on edge and there was a tension in the room. I had come a long way, physically and in time, to see the killers of Airey Neave, and here I was, face to face. Not with the men who planted the bomb on 30 March 1979, almost twenty-two years ago to the day, but with ‘someone connected with the Neave operation’ who belonged to the small but highly dangerous Irish National Liberation Army.

The trail started five years earlier, when I was writing a biography of John Hume, leader of the SDLP, a shrewd nationalist and a rock for thirty years in the maelstrom of Irish – and British – politics. Hume crossed paths with Neave, the Conservatives’ Shadow Northern Ireland Secretary, many times during the late 1970s. It was not a profitable relationship. Hume found Neave’s traditional Tory attitudes towards Ulster Unionism and his militarist stance on the Troubles short-sighted and unsophisticated. Neave probably thought the former trainee priest slippery and threatening. He had, after all, engineered the short-lived exercise in political power-sharing that the Tory spokesman on Ulster utterly rejected.

Neave’s impact on policy towards Northern Ireland during the four years he held the Shadow portfolio was limited, but his death at the hands of terrorist assassins in the precincts of the House of Commons convulsed politics and prompted the question in my mind: ‘Who was this man?’ There was no biography of Airey Neave, yet he had lived an eventful life. Eton, Oxford and the Inns of Court were followed by capture in the siege of Calais, prison camps, escape from Colditz and service in military intelligence. He had served the indictments on Nazi war criminals in Nuremberg and entered Parliament at his third attempt in a by-election. A promising ministerial career was cut short by a heart attack, and he seemed destined to live out his political career in back-bench obscurity until the social upheavals of the 1970s propelled him into history as the man who gave us Margaret Thatcher.

It was a remarkable story, but no one had written it. I therefore resolved to do so and began collecting material. It was clear from the outset that Neave’s family (his daughter Marigold and two sons, Patrick and William) were apprehensive about the project. Neave had not wanted a biography, beyond the books he had written about his life, nor did his widow, Diana, who died in 1992. Other approaches, I knew, had been rebuffed and I was hardly the writer of choice. Yet I persisted and the family finally agreed to cooperate, though not on a lavish scale.

Much more difficult was ‘the other side’ – the perpetrators of the murder. Over the years reporting from Ulster, through a republican contact I will not name, I had learned something of the Irish Republican Socialist Party, the political wing of INLA. After an initial social meeting in a Belfast bar, at which I outlined my intentions, I let the seeds germinate. Then, in the autumn of 2000, I approached the IRSP directly, and arranged to visit the party’s headquarters in the Falls Road, the heart of republican Belfast. The taxi driver who took me there on 17 November advised against going into the pub opposite. ‘Not with your accent [Yorkshire],’ he grinned. Seamus Costello House, a large red-brick villa (allegedly bought with the proceeds of a bank robbery) is protected by steel mesh fortifications. A photographic tableau of the dead hunger strikers stands outside. Inside, the atmosphere is more homely, reminiscent of an old-fashioned trade union branch office, with people asking for advice and children playing about their mothers’ knees. Banners and framed slogans decorate the walls. The furniture is utilitarian. Everyone smokes.

Paul Lyttle, the IRSP’s spokesman, listened courteously to my pitch. It was clear from the first that my credentials had already been thoroughly checked. They knew who I was and where I was coming from before I opened my mouth. So, indeed, did the security services. This visit was known in London before I returned the following day. I told Lyttle that I wanted to write an account of Neave’s death that was as authentic as possible. To that end, I wished to meet the killers, if possible; and if that could not be arranged, then to talk to INLA ‘volunteers’ involved in the operation. There had been many accounts of the assassination, mostly conflicting. Was it not now time for the truth?

The door seemed to be ajar. The IRSP man dwelt on the dangers that Neave presented to militant republicanism, being one of the few British politicians who (as an ex-POW) knew just how critical was the morale and organisation of ‘the men behind the wire’. However, those men had virtually all been released under the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, and yes, the organisation might be willing to brief me. A decision would have to be taken by ‘the executive’, and this process would take some time. It was also plain that the IRSP/INLA felt that the assassinations of four of their top people in the aftermath of Neave’s death should receive the same kind of public scrutiny currently being given by the Savile Enquiry to the killings on Bloody Sunday in Londonderry in January 1972. I said I had no difficulty in understanding their desire to get to the bottom of these high-profile murders, which were widely laid at the feet of the security services working through loyalist proxies. And I would say as much, though I fear the party’s demands for a similar public enquiry will fall on deaf ears.

Weeks passed, and after Christmas I wrote again to the IRSP, pointing out my approaching deadline for completion of the book. I also telephoned regularly, not a simple procedure. Seamus Costello House is not Millbank or Central Office. Finally, I was given a number to contact in the Irish Republic. It was a mobile, not reachable from London. Further frustrating delays followed before I got through to a man I will refer to as Eoin. He told me to go to Belfast on the weekend of 24 March, and get in touch again on Friday 23rd. On Thursday, I received a message to call him again, and was redirected to Cork, hundreds of miles to the south in the Republic. It was too late to book a direct flight, so I continued via Belfast on the 23rd. Foot and mouth disease had just broken out in County Louth, slowing the train journey to Dublin, but I reached Cork in the early evening.

My instructions were to book into the Silver Springs Hotel, a modern establishment a few miles south of the city, and to await a call the following day. It was a bright, clear morning and the telephone rang at 9.30 a.m. I was to take a taxi to a country pub about five miles away, where I would be met. I waited in the lobby, self-consciously British in a dark suit and university tie. Just after 10.00 a.m., two men entered and motioned me into the bar. One was young, in his twenties, powerfully-built and dressed in waxed jacket and jeans. The other was much older, with white hair. Waxed-jacket said: ‘We will take you in the car. You will not look at the number plate. You will look down at the floor, not where we are going. Understand?’ I did. He then asked if I had a mobile phone, and I fished mine from a travel bag thinking he wished to use it. He confiscated the instrument.

Outside, he stood guard so I could not see the number plate. The older man drove, through various country lanes. It was difficult to obey the injunction to stare at the floor, but since I had no idea where we were it seemed superfluous anyway. We stopped outside an isolated house, quite high up, with hills around. I was escorted into the front room, where the thick curtains were drawn. Eoin, now that I saw him, looked like a schoolteacher in his late thirties: neat, spare and casually but well dressed. He introduced the man in the mask as ‘someone directly involved in the Neave operation’. I asked if I could take a shorthand note and he nodded. ‘You’re not wired?’ he interjected suddenly. ‘Open your shirt.’ I unbuttoned my shirt to the waist to show there was no hidden microphone. He frisked me, arms, back, front and legs. The tension eased somewhat, though I then spotted the handgun next to him. Had I done anything silly, I think it would have been used.

However, coffee and biscuits were served, as though we were discussing details of the Easter holidays rather than the brutal murder of a British politician two decades earlier. We spoke for two and a half hours, a mixture of questions and volunteered statements. The man in the mask, who displayed a very detailed knowledge of bomb-making and the modus operandi of the assassination, occasionally tugged at his uncomfortable camouflage. Eoin, the more intellectual of the two, ranged across the whole subject of INLA, the armed struggle and prospects for the future. It was a fascinating, if eerie, dialogue. What follows in Chapter 18 is a distillation of that briefing. I believe it to be the most authentic account yet of the circumstances of Airey Neave’s death. I expect that others may contest this assessment, but I am convinced that the IRSP/INLA deliberately gave this briefing to ensure that the truth is established, not least because they want the truth about the killing of their own.

At the close of the meeting, my mobile phone was returned, with the SIM card disabled so I could not be traced. The white-haired driver took me to a shopping centre, where I took a taxi back into Cork city to take the train to Dublin and Belfast. I drank a pint of Guinness at the station and pondered my experience. Instead of a reporter’s elation at finding my quarry, I felt a curious unease, as though I had discovered something I would rather not have known. Yet there was no going back, and I turned for home with a determination to get all this out. I hope the succeeding pages will demonstrate the virtue of seeking the truth, unpalatable though it may be. The Irish Question is never going to be solved by meek acceptance of the official line.

It should be added that this biography is not authorised, nor did I seek authorisation. Neave had written much about his own life, but his widow Diana rejected writers’ advances to sanction a biography of her husband. Patrick Cosgrave, a family friend, said she had asked him ‘to spread the word among the writing classes that she would, in no circumstances, countenance such a project’. Plainly, we do not move among the same writing classes because no such word reached these quarters.

However, I was able to speak to Neave’s children, Marigold, Patrick and William, for which I am grateful. I would also like to thank his cousin Julius Neave, of Mill Green House, Ingatestone. My gratitude also goes to Toni Luteyn, Neave’s co-escaper from Colditz, still alive and well in The Hague; to Frau Lipmann, curator of Colditz Museum; to the dedicated staff at the unrivalled political history collection at the Linen Hall Library for their help and advice; to the librarians at Eton College and Merton College, Oxford; to my colleagues in Westminster, especially Desmond McCartan, formerly of the Belfast Telegraph and David Healy of Bloomberg Agency; to Colin Wallace, Brian Crozier, Gerald James, Michael Elliott, Kevin Cahill, Roger Bolton, Richard Dumbreck, Sir Edward du Cann, Sir William Shelton, Tam Dalyell, Lord Lawton, Lord Campbell of Alloway, Ken Lockwood of the Colditz Association, Steven Norris, Kevin Macnamara MP, and those in London and Belfast who would be embarrassed (or worse) if identified; to Clive Priddle, Mitzi Angel and Kate Balmforth at Fourth Estate for their patience, and Richard Collins for his professional copy-editing; to my agent Jane Bradish-Ellames and finally to my wife Lynne for living with a political murder for too many years.

Walworth, south London

November 2001

1 The Price of Liberty (#ulink_2e40e016-3c90-5dcc-aec0-0a70f33ffa94)

At 2.58 p.m. on 30 March 1979 an enormous explosion shook New Palace Yard in the precincts of the Palace of Westminster. Seconds later, smoke was seen billowing from the wreckage of a saloon car on the ramp leading up from the MPs’ car park into the cobbled courtyard just below Big Ben.

The blast was heard in the Commons chamber, where parliament was about to be dissolved for a General Election that would sweep Margaret Thatcher into Downing Street. Policemen and parliamentary journalists rushed to the scene and found an unidentifiable man, dressed in the black coat and striped trousers of an old-fashioned style still worn by Conservative MPs. David Healy, political correspondent of the Press Association news agency, was in the third-floor Press Gallery bar, whose back windows look down on New Palace Yard. A veteran reporter of the Irish Troubles, Healy recognised the familiar noise. ‘I knew it was a bomb,’ he said. ‘I looked out of the window and saw smoke, and rushed downstairs. The car was burning, the windows all broken. And this guy was almost blown into a standing position behind the wheel. A cop shouted, “He’s still alive! Clear the area!” I didn’t think there was much life left in him. I couldn’t tell who it was, though I had been having a drink with him only two nights earlier.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Another Westminster lobby correspondent, Desmond McCartan of the Belfast Telegraph, who knew the victim well, wrote: ‘The blackened, bleeding features amid the tangled wreckage of his Vauxhall car concealed his identity, but the pain of his dying was clear.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Ambulancemen who arrived within minutes found the still unidentified figure slumped over the driving wheel, his face blackened, his hair and clothing charred from the blast. His right leg was blown off below the knee, and his left leg was almost completely severed. One ambulanceman, Brian Craggs, tried to give him oxygen: ‘He was still breathing, but was very badly injured. He never regained consciousness.’ A doctor and nurse also attended, before he was freed after half an hour of frantic effort by firefighters.

Others had also recognised the noise. In Margaret Thatcher’s office, Chris Patten, a future Northern Ireland minister, exclaimed ‘That was a bomb!’ Thatcher’s entourage witnessed the grim scene from an upstairs window and Guinevere Tilney, wife of a former Tory MP and adviser to the Conservative leader, was the first to discover the identity of the victim. In the car, dying, lay Airey Neave, Conservative MP for Abingdon, war hero and habitué of the murky world where the politics of democracy and the secret state intertwine, the man who had engineered Margaret Thatcher’s rise to power. Mrs Tilney immediately went to the Neave family flat in Marsham Street to tell his wife Diana, and took her to Westminster Hospital where Neave was undergoing emergency surgery. The surgeons could do little. His heart stopped on the operating table and he died eight minutes after arriving at the hospital. His devoted wife was too late to see him alive.

It was a bloody end to a long career in public life, one marked in turn by disappointment and triumph ultimately crowned by Neave’s brilliant campaign to secure the Conservative Party leadership for Margaret Thatcher, an event that would radically change British – and international – politics. For his key role in that crusade, Neave was rewarded with the Shadow Cabinet portfolio that he coveted: Northern Ireland. It was a strange post to covet. Ulster has traditionally been regarded by pundits as a graveyard for political ambition, and Neave was fifty-nine when he took on the job in February 1975, having hitherto shown no serious public interest in the issue.

Nor did Neave look the part. Usually described as a slightly-built, red-faced man, with thinning hair, sharp features and a broad smile that rarely gave way to laughter, he moved with an almost feline grace, seeming to drift along rather than walk. He listened much, said little and when he did speak, he did so quietly. At a party given by Alan Clark, Thatcherite minister and diarist, George Gardiner, a right-wing Tory MP of the 1974 intake, listened to Neave ‘gently sounding out opinions in a voice you had to strain to hear’. Ian Aitken, political editor of the Guardian, found him ‘slightly sinister’. He was not particularly clubbable at Westminster though he was a member of the Special Services Club, tucked away in a side street behind Harrods where former and serving ‘spooks’ debated the follies of the world over cocktails.

The Troubles had been in full spate for several years by the time of his appointment, and showed no sign of abating. Shootings and bombings in the province were commonplace, and by taking Shadow Cabinet responsibility for British government policy he placed himself in the front line. It was almost as if the decorated war hero was inviting the bomb that prematurely ended his life. He told the journalist Patrick Cosgrave: ‘If they come for me, the one thing we can be sure of is that they will not face me. They’re not soldier enough for that.’

(#litres_trial_promo) His parliamentary agent Les Brown also claimed that Neave always knew he was on a death list, but realised it went with the territory. The writer Rebecca West had many years previously observed: ‘It is, I think, against his principles to care much about danger.’

Margaret Thatcher had no doubt that Neave was the right man for the job. ‘His intelligence contacts, proven physical courage and shrewdness amply qualified him for this testing and largely thankless task,’ she calculated.

(#litres_trial_promo) Her choice of priorities in this assessment is illuminating. She thought of him first as an expert in the field of military intelligence and only then as a man of nerve and astuteness. She did not immediately identify him as a politician with an agenda for bringing peace to the benighted province, where more than 247 people had died in the first year he was responsible for Opposition policy on Ulster. Her judgement was shared by Sir John Tilney, author of Neave’s entry in The Dictionary of National Biography. Working from ‘private information’, Tilney pointedly describes Neave as an ‘intelligence officer and politician’.

That Thatcher and Tilney should independently have come to the same conclusion should surprise no one, for Airey Neave was an intelligence officer who became a public servant. Like many who have trodden the same path, he did not slough off his first persona when he entered public life. The values of what has become known as ‘the secret state’, as well as the lessons of his wartime experiences, informed his outlook as a politician. He had many contacts among former security service officers and high-ranking army officers, and sympathised with the aims of the ultra-right groups that prepared for ‘civil breakdown’ in the 1970s. He was a public servant who never really stopped being a secret agent.

Neave’s background helped. His was a conformist, upper middle-class upbringing – prep school, Eton and Oxford, with a career at the Bar beckoning as the Second World War broke out. The son of a prominent entomologist and scion of an Essex county family whose lineage stretched back several hundred years (and included a Governor of the Bank of England), it was only to be expected that he would possess a relatively orthodox outlook on life. In Neave’s case, that sense of being British and right so endemic in his class was reinforced in his mid-teens when he was sent to Germany in 1933 to live with a local family and learn the language. He saw Fascism in practice, and formed a lifelong antipathy, amounting to an obsession, towards authoritarianism. Some of that feeling came from his pre-war and wartime adventures and filtered through a pessimistic fear of the spread of Communism that would harden during the Cold War and the civil unrest in Britain.

His initial links with the military were conventional enough, beginning when he enlisted in the Territorial Army as an undergraduate at Merton College. If Neave was swimming against the prevailing intellectual tide of leftism at university. His interest in the secretive world of Tory clubland politics also began at this period. He was a member of the Castlereagh Club, a political dining club that met in St James’s, Piccadilly, usually once a fortnight, to hear the views of a Tory dignitary. Donald Hamilton-Hill, later second in command of Special Operations Executive (SOE), the wartime resistance organisation, was also a member. In pre-war days he was chairman of public relations and head of recruiting for the Young Conservatives’ Union, and shared with Neave a predilection for the social contacts which ultimately led them into ‘politically informative circles’. Confidentiality, if not mystery, was the order of the day. Hamilton-Hill recorded that members of the Castlereagh Club held ‘off the record and interesting discussions – with no reporters present and members sworn to secrecy’. After a ‘splendid dinner’ they formed an easy and appreciative friendship over port, brandy and cigars.

(#litres_trial_promo) For the young Neave, it was heady and exciting stuff, and plainly a taste for secrecy and subterfuge was being acquired early. One of their mentors was Ronnie Cartland, a Tory MP who would be killed at Dunkirk; Peter Wilkinson, who went on to General de Wiart’s staff of the British Military Mission to Poland in 1939, was also a member. He later became Chief of Administration of the Diplomatic Service, and retired in 1976 as Coordinator of Intelligence and Security in the Cabinet Office. Val Duncan, subsequently knighted and chairman of the Rio Tinto Zinc Corporation, was also to be found at the Castlereagh table. In the late sixties, he would head an enquiry into the Foreign Office at Wilkinson’s behest.

Quite why the enthusiastic diners chose an Irish grandee as the club’s eponymous hero is unclear, but in Neave’s case it was prophetic. Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh, was born in Dublin in 1769 and became Tory MP for County Down at the end of the eighteenth century. He was appointed Irish Secretary in 1797 and his name became a byword for cruelty, although he was venerated as a great British statesman. In ‘The Mask of Anarchy’ of 1819, Shelley was prompted to write: ‘I met Murder on the Way / He had a mask like Castlereagh’. Almost two hundred years later, his name was remembered in the British government’s Castlereagh interrogation centre in Belfast, itself the subject of an enquiry into Royal Ulster Constabulary brutality during Neave’s time as Shadow Northern Ireland Secretary. Thus was Neave drawn early on into the demi-monde of clubland, where politics meets the secret state. Security and intelligence expert Stephen Dorril argues its relevance: ‘This is the key to the way these people operate. Their dining clubs go on for a long time. They are the networks of political power and advancement. They bring all the elements of the secret state together.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

When the war rudely interrupted this agreeable scene, Neave was among the first to volunteer for active service. His experiences at Calais in 1940, his subsequent capture and imprisonment by the Germans, followed by escape from Colditz in 1942, brought him to the attention of British military intelligence on his arrival in neutral Switzerland, whence he was fast-tracked back to Britain and immediately recruited to MI9, the escape and evasion organisation for Allied servicemen. Nominally an independent section of the war effort, MI9 was in fact – and much to Neave’s delight – a wholly-owned subsidiary of MI6, the Secret Intelligence Service.

Neave worked in this clandestine operation for three years, training agents to be sent into the escape ‘ratlines’ of Occupied Europe and debriefing escapers before following hard on the heels of the invading Allies in July 1944. His service also took him to forward engagement areas in France, Belgium and Holland, where he successfully spirited out remnants of Operation Market Garden, the abortive Arnhem raid. He ended the war a DSO and an MC. The closing stages of the war found Neave in Paris and Brussels in 1944 running British operations to grant awards and medals to MI9 agents who had helped Allied servicemen to escape or evade the enemy. Such operations had a further, undisclosed objective: that of identifying agents who would continue to be valuable after the war in the context of a Cold War (or worse) between Western nations and the Soviet Union. The bureaux drew up lists of ‘reliable’ contacts who would be useful in the event of a Soviet invasion of Western Europe. It was sensitive work, not least because so many of the Resistance were Communists and at this stage still sympathetic to the Soviet Union.

This covert enterprise, known as Operation Gladio, brought together a wide range of skills, from those involving psychological warfare and sabotage to escape and evasion. Gladio’s purpose was to set up ‘stay-behind’ units that would be active in a Europe threatened or even occupied by the USSR. Their existence has never been officially recognised, nor disclosed. Stephen Dorril argues: ‘It appears that sections of MI6 were already thinking in terms of the next war, and part of that was a fear that the Red Army would continue from Berlin and go straight to the Channel coast. They wanted stay-behind units against the Red Army in the same way that they wanted them against the Germans. Some of these units put in place in 1944 were almost immediately being resurrected as anti-Communist units – ratlines for escape and evasion.’

(#litres_trial_promo) SOE would take on the sabotage role, while Neave’s old firm would carry on as before.

But in post-war austere Britain the climate was against such initiatives: money for secret operations was getting tight and it was difficult to sustain a continuity between wartime and post-war groups. The Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee disapproved of such activities and the emphasis shifted from formal policy to the unofficial but well-connected world of former intelligence operatives. The thread continued in dining clubs, the Special Services Club and in the part-time Territorial Army. MI9 was reborn as Intelligence School 9 (TA) and Neave was commanding officer from 1949 to 1951, at a time when he was seeking to enter public life as a Conservative MP. IS9 later became 23 SAS Regiment, based in the Midlands, with a role to counter domestic subversion.

While his political career blossomed in the late 1950s, Neave’s links with the secret state necessarily became more obscure. It is known that sometime in 1955, he approved the appointment of British spy Greville Wynne as the representative in Eastern Europe of the pressure-vessel manufacturers John Thompson, of which Neave was a director. Like Neave, Wynne had worked for MI6 during the war. He returned to spying in the mid fifties and used his business trips behind the Iron Curtain to recruit the Soviet spymaster Oleg Penkovsky, before being unmasked and jailed. He was freed in exchange for Russian agent Gordon Lonsdale. Wynne confessed that ‘after a time, espionage is like a drug, you become to a greater or lesser extent addicted.’ It is inconceivable that Neave was unaware of Wynne’s MI6 role. Neave continued to meet with his old comrades, and to harbour fears of Communist subversion, but to the world at large he was a quiet, thoughtful man, assumed by commentators to be on the centre-left of his party. After his relatively brief, and not very glorious, ministerial career at the Transport and Air departments, he returned to the back benches in 1959. From there he campaigned successfully for compensation for British survivors of Sachsenhausen concentration camp, but unsuccessfully for the release from Spandau prison of Nazi war criminal Rudolf Hess, whose flight to Scotland in May 1941 had delivered him into British hands. He sought to assuage the suffering of refugees through his voluntary work for the UN High Commission for Refugees. In addition, he became a governor of Imperial College, London, and chairman of the Commons Select Committee on Science and Technology.

But behind the façade there still burned a sense of mission. He watched with apprehension the collectivist drift of Britain and the growing power of the trade unions. He believed the danger of expansionist Communism was both real and present and he believed fiercely in freedom. In the record of his wartime exploits, They Have Their Exits, he laid down his credo, ‘No one who has not known the pain of imprisonment understands the meaning of liberty’, a line that is engraved on the walls of the museum in Colditz castle as a testament to his dedication. The title of Neave’s book was taken from As You Like It: ‘All the world’s a stage/And all the men and women merely players; / They have their exits and their entrances; / And one man in his time plays many parts.’ No quotation more satisfyingly expresses the different sides of Airey Neave. He was a man who played many parts but the drama was discreet and informal. He played many roles behind the scene. Given the nature and scale of his involvement with the security services, it may also be argued that Neave valued his own freedom and that of those around him so much that he was prepared to countenance extreme measures to safeguard his concept of liberty. Roger Bolton, a television producer who knew him and put together a documentary on his assassination, argues the paradox that Neave was a moral man willing to do things that immoral people were not: ‘If necessary, he took the gun out and there were difficult things to be done but for the most honourable of reasons.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Why did he imagine that he knew better than the rest? Neave was not a particularly gifted politician, and it seems unlikely that he would have risen to the ranks of a Conservative Cabinet in the ordinary way. And yet, of the Tory MPs of his generation, Neave left the most indelible mark on political history by riding an inner conviction that his grasp was somehow superior. He felt he should turn that comprehension to common advantage; he was a spook who believed he knew, and who acted on his beliefs and loyalties. He was not alone in such self-assurance, which is the stock in trade of the spy. Although he was not an orthodox MI6 officer, Neave shared the outlook of the security services and remained close to them. He may have been an elected politician in a democracy, but he shared the misgivings about the world around him expressed most cogently by George Kennedy Young, with whom Neave was actively acquainted.

While still deputy director of MI6, some time in the late 1950s, Young issued a circular to his staff on the role of the spy in the modern world. He noted scathingly the ‘ceaseless talk’ about the rule of law, civilised relations between nations, the spread of the democratic process, self-determination and national sovereignty, respect for the rights of man and human dignity to be found in the press, in Parliament, the United Nations and from the pulpit: ‘The reality, we all know perfectly well, is quite the opposite, and consists of an ever-increasing spread of lawlessness, disregard of international contract, cruelty and corruption. The nuclear stalemate is matched by a moral stalemate.’ Young further stated that ultimately it was the spy who was called upon to remedy situations created by the deficiencies of ministers, diplomats, generals and priests, and that the spy found himself ‘the main guardian of intellectual integrity.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Neave’s nature is readily discernible here: the man who keeps himself to himself, but knows. The man who hates ostentation but goes about his dedicated business with a discreet energy, working for his Queen, country and traditions.

The Britain of the early 1970s, with its crippling strikes, inflation and civil war in all but name in Ulster, called forth men like him on a mission to save the country they loved. At least, that was the way they saw it. From the recesses of the security services, from the upper reaches of the City, from London’s clubland, and from the right of the Conservative Party, came volunteers eager to fight the good fight, Neave among them. But if his greatest contribution to politics was to mastermind the coup that dethroned Edward Heath (employing the ‘psy-ops’ skills he had acquired in his intelligence years) and brought the leadership of the Tory Party to Margaret Thatcher, it did not rob him of a taste for the covert. Soon after Thatcher took over, amid nervousness in the City as inflation soared to 25 per cent and with the pound at little more than 70 per cent of its 1971 value, Neave attended a reception of Tory MPs given by George Kennedy Young, by now the ex-deputy director of MI6. General Walter Walker, former Commander-in-Chief of NATO’s Northern Command, was also there. In 1973, at the height of industrial unrest, he had set up Civil Assistance, a quasi-private army of ‘apprehensive patriots’ to give aid to the authorities.

It was never called upon to carry out this function but the theme did not lose its attractions. Neave became involved in Tory Action, a right-wing pressure group within the party, and the National Association for Freedom (NAFF), set up in late 1975 to counter ‘Marxist subversion’. This organisation had more success than Civil Assistance, notably in the legal harrying of strikers. However, the most intriguing – and sinister – of Neave’s operations came in 1976 when he became involved with Colin Wallace, an army intelligence officer working for Army Information Policy in Northern Ireland. Operation Clockwork Orange, initially created to undermine republican terrorists through a disinformation machine to the media, would spread its tentacles into the higher echelons of British politics to probe and exploit the weaknesses of key figures. Aware of Wallace’s MI5 background and his disinformation programme, Neave would maintain his contacts with him when he was appointed Shadow Northern Ireland Secretary.

Neave’s connections with the secret state, past and present, gave rise to speculation that he could also be given the task of liaising between the government and the intelligence services – a job similar to that undertaken by Colonel George Wigg, Paymaster-General in Harold Wilson’s government.

(#litres_trial_promo) Wigg, known in Parliament as ‘the Bloodhound’, certainly admired Neave, describing him as ‘a smart operator who learned from me’. Plainly, the spooks’ mutual admiration society crossed boundaries. It also influenced intelligence policy. Neave’s high opinion of Maurice Oldfield was almost certainly instrumental in Thatcher’s decision to appoint the former head of MI6 as Coordinator of Security and Intelligence in Northern Ireland in October 1979. Oldfield, in charge of MI6 from 1965 to 1977, had survived a bomb attack on his London flat in 1975.

In parliament, Neave gave full support to Roy Mason, the hard-line Labour Ulster Secretary, urging him to go further and ‘pick off the gangsters’ of the IRA. Neave’s policy for Ireland, insofar as it was understood in London and Dublin, was a twin-track strategy of devolving some powers to local councils in Ulster, coupled with the toughest possible military crackdown on republican terrorism. He had no time for power-sharing between nationalists and Unionists, arguing that it had failed and should not be tried again. It was the agenda of a soldier rather than a politician who understood Ireland and the Irish. Nonetheless, his blood-curdling warnings of the wrath that was to come when the Conservatives took office made republicans sit up and take notice of him. They feared him. He believed he had a special insight into the guerrilla mind. ‘I know how the IRA should be dealt with because I was a terrorist myself once,’ he told an Irish journalist.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Neave would have had the British army at his disposal. Indeed, he still thought of himself as ‘one of them’. He believed that specially trained soldiers should be used to ‘get the godfathers of the IRA’ and rejected any suggestion of amnesty for convicted terrorists as part of a peace deal. It was quite clear that the price of liberty in Ulster could involve the annihilation of those engaged in violence for political ends. This Cromwellian solution was what Neave meant by liberty. The policy was to bring about his own death before it could be implemented.

Yet, for all the convulsions created by Neave’s death, the secret state has left his assassination in a limbo of oblivion. Apart from an (officially) abortive police enquiry, which also involved the security services, there has been no attempt to investigate Neave’s life and death. Sources as diverse as Enoch Powell and ex-collaborators with Neave believe that the authorities themselves may have had a hand in the bloody affair. Even his own daughter Marigold believes the facts have been suppressed. ‘I think there was a cover-up,’ she said across her kitchen table in deepest Worcestershire one cold January morning. ‘They only say “he died a soldier’s death”.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

2 Origins (#ulink_78f08462-a70d-590d-a476-17c2b7e18ddd)

Airey Neave was born at 24 De Vere Gardens, Knightsbridge, a stone’s throw from Kensington Palace and just down the road from the Royal Albert Hall, on 23 January 1916. His father, Sheffield Airey Neave, continued an eccentric family tradition and burdened his son with family surnames, adding to his own that of his wife Dorothy Middleton. Thus, Neave was christened Airey Middleton Sheffield. As he grew up, Airey began to hate his whimsical collection of names, so much so that he rechristened himself Anthony during the war years and only reverted to Airey when he entered public life.

Airey must have quickly appreciated that his family was steeped in history. Of Flemish – Norman origin, the Neaves came to England in the wake of William the Conqueror and settled in Norfolk about 200 years before the earliest recorded member of the family, Robert le Neve, who lived in Tivetshall, Norfolk, in 1399. His forebears lived in villages around Norwich where they became landowners and sheep farmers. As they prospered in the wool trade, some le Neves struck out further afield, to Kent and Scotland, but they stayed chiefly in East Anglia, gaining social distinction. Sir William le Neve, a native of Norfolk, was Clarenceux King-of-Arms at the College of Heralds in London in 1660.

The failure of the wool trade in the mid-seventeenth century drove some enterprising members of the family to seek their fortunes in London, with mixed results. One generation was wiped out by the Black Death in the 1660s (the victims are reputedly buried under a church in Threadneedle Street) but Richard Neave, who lived from 1666 to 1741, fared better, establishing a prosperous business in London, with offices in the Minories. He made most of his wealth from the manufacture of soap, a new and very fashionable product for the period. He bought land east of London outside the city limits, where his sons began to establish what would become London docks. His business also expanded overseas, with estates in the West Indies, and he put his accumulated resources into his own bank in the City.

The business further prospered through judicious marriages and Richard’s grandson, bearing the same name, bought the Dagnam estate in Essex, so beginning the family’s long connection with the county which remains to this day. His grandson became Governor of the Bank of England in 1780 and a baronet in 1795. The family crest, a French fleur-de-lis, with a single lily growing out of a crown, long predates the adoption of the Neave motto, Sola Proba Quae Honesta, which translates literally as ‘Right Things Only Are Honourable’. Speculation about possible royal connections linked to the appearance of a crown on the crest, admits Airey’s cousin Julius Neave, has given rise to ‘some fanciful but quite unsubstantiated theories’ as to the family’s origins.

However, the family’s upward mobility was undeniable. Sheffield Neave, another Governor of the Bank of England (1857–9), gave his Christian name to succeeding generations (some noted for their longevity), one of whom was Airey’s grandfather, Sheffield Henry Morier Neave (1853–1936), well-known in Essex for his eccentricity. He inherited a fortune while still at Eton, and went up to Balliol College, Oxford, where he acquired a degree but showed no inclination to pursue a profession thereafter. With plenty of money and no need to work, he indulged his passion for big game hunting, spending long periods in Africa, where he became convinced that control of the malarial tsetse fly was the only bar to great agricultural prosperity in sub-Saharan Africa. He returned to England and studied to become a doctor in middle age, eventually rising to become Physician of The Queen’s Hospital.

At the age of twenty-five, Sheffield Neave married Gertrude Charlotte, daughter of Julius Talbot Airey. They lived at Mill Green Park, Ingatestone, which was to become the family seat, and it was to Mill Green that Neave would return after his incarceration in Colditz. He dreamed vividly of the house during his captivity, and lyrically described its chestnut trees, its May blossom and the white entrance gates in his first book, They Have Their Exits.

Sheffield Neave had his own Essex stag hounds and was a legend in the field. Ever the eccentric, the stags he hunted were not wild but carted to the meet in the same vehicle as the hounds: ‘There was never any question of the hounds killing the stag, who was much too valuable to be lost in this way,’ Julius Neave has explained.

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘They all came home to Mill Green at the end of the day and were stabled together.’ Sheffield gave up stag-hunting at the turn of the nineteenth century, complaining that ‘Essex is getting too built over’, but he rode to hounds until nearly eighty, when he took up golf instead. Long after his death a particularly vicious jump over a ditch and stream was still known as ‘Neave’s leap’.

Gertrude Neave, the epitome of a Victorian lady, was an accomplished pianist and also composed music. She came from a distinguished family, one of her relations being General Lord Airey, chief of staff to Lord Raglan, Commander-in-Chief of the British army in the Crimean War. He was, reputedly, the ‘someone who blundered’ over confused orders which led to the Charge of the Light Brigade. Gertrude and Sheffield had two sons and two daughters. The elder son, Sheffield Airey, born in 1879, was Airey Neave’s father; the younger, Richard, became a professional soldier and saw service in the Boer War, India and in Gallipoli in 1916. He also served in Ireland during the Troubles of 1920–22, and Airey may well have heard stories of ‘the Fenians’ from his uncle.

Airey’s father went to prep school in Churchstoke, in the Welsh Marches, and then (as befits the grandson of a Governor of the Bank of England) on to Eton and Magdalen College, Oxford, to read natural sciences. He inherited his father’s fascination with Africa and the diseases spread by insects. In the years before the Great War, he travelled in 1904–5 on the Naturalist Geodetic Survey of Northern Rhodesia, and to Katanga as entomologist to the Sleeping Sickness Commission of 1906–8. On his return from Africa, he served in a similar capacity on the Entomological Research Committee for four years before being appointed Assistant Director of the Imperial Institute of Entomology at the age of only thirty-four. He was to hold the post for thirty-three more years and then took over as director in 1942, the year Airey escaped from Colditz, before retiring in 1946.

A big, dominant man with a moustache, Sheffield Neave was a distant figure, immersed in his scientific work and given to a Victorian aloofness from his children. After Airey’s birth, the family moved to a house in High Street, Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, where four more children were born: Averil, Rosamund and Viola, and then a second son, Digby. Dorothy Neave, descended from an Anglo-Irish family, played a traditional role in the family: she ran a comfortable if unostentatious household. There were servants and appearances to keep up but Dorothy was often unwell and died of cancer in 1943 when Airey was working for MI9. Airey’s daughter Marigold says that he did not have a good relationship with his father. ‘He was very much a scientist. Perhaps that is what made him not very easy to get on with. He was very remote, a very Victorian figure.’

(#litres_trial_promo) If not physically robust, Airey’s mother possessed a mental determination unusual in her position. ‘Grandmother was quite forward-looking, quite progressive for those days. She was a liberal with a small “l”,’ recorded Marigold. ‘His childhood was not very easy. His mother was very often ill. Officially, he looks very much like her, but he never talked about her. He talked about his father, but not in very glowing terms. He was a very strict character, powerful and good-looking: a strong face, very dark eyes. And physically he was very tough. It was a clash of personalities.’ Group Captain Leonard Cheshire, the Dam Busters war hero, friend and contemporary at Merton, would come to a similar conclusion. Neave, he wrote, was highly independent and always ready to follow his inner convictions. ‘No matter what the opposition, he would often do things that were a little wild, though always in rather a nice way and never unkindly.’ This trait endeared him to school and university friends, ‘but possibly had a different effect upon his father who one has the impression did not always give him the encouragement which inwardly he needed. Thus, at a very early age he learned to conceal his inner disappointments.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Airey Neave attended the Montessori School in Beaconsfield, a progressive school where his individuality was respected. In 1925, at the age of nine, he was sent to St Ronan’s Preparatory School in Worthing, Sussex. The headmaster, Stanley Harris, was a remarkable man who had played football for England, and captained the Corinthians, the famous amateur team. The essence of his educational philosophy was captured in the school prayer, known as Harry’s Prayer, which ran:

If perchance this school may be A happier place because of me Stronger for the strength I bring Brighter for the songs I sing Purer for the path I tread Wiser for the light I shed Then I can leave without a sigh For in any event have I been I.

Set in several acres on the outskirts of Worthing, St Ronan’s placed great emphasis on academic excellence, sport and self-development. In many ways an archetypal English prep school – numbering future air vice-marshals and an Asquith among its pupils – it was built in red brick and sat against the backdrop of the South Downs. Despite the usual rigours of such places, the school had a patriotic rather than militaristic air about it. There was no cadet corps but boys were taught shooting, and from time to time a former army sergeant – so old that he had been with Kitchener at Khartoum – came to the school to teach gymnastics and boxing. With their days filled, in the evenings boys were allowed to pursue their own interests. In Neave’s time, some of them built a primitive radio – a crystal set with ‘cat’s whiskers’ tuning. Others drew maps of imaginary countries, bestowing such nations with complex railway timetables. Essentially, they had to learn to make their own amusement, and learn to fend for themselves, all of which helped develop a form of independence.

In 1926 Stanley Harris died of cancer and his place was taken by his brother, Walter Bruce (Dick) Harris, then a housemaster at nearby Lancing College. If Airey was a better than average pupil he was not spectacularly so, and seems to have been suited to his first form which was ‘composed mostly of boys with plenty of ability, one or two of whom however have no great idea of work’. In 1925, he won a combined subjects prize, but in class 1A in 1927 he was fourteenth. By the following year he had crept up to eleventh, then ninth and finally sixth, with 1, 205 points. That autumn, he also won the Latin prize. The highest placing he received was third, but mostly he fluctuated around the lower end of the top ten. The boys were expected to take a full part in the life of the school. Airey played a waiter in the school play in 1928, and the St Ronan’s magazine observed: ‘A word must be given to Neave who by progressive stages became the perfect waiter.’ Praise indeed.

One contemporary at St Ronan’s recalls that Neave was a rather undistinguished small boy, neither games player nor leader nor scholar. He was teased mercilessly about his name. Others spoke warmly of him. Dick Harris described him as having been ‘a gentle child’; echoing that sentiment, Lord Thorneycroft, a contemporary in parliament, would much later describe him as ‘a very brave and yet gentle man’. His daughter Marigold insists that he hated prep school.

At the age of twelve, Airey went to his father’s old school, Eton, one of three boys to go from St Ronan’s in the Lent term of 1929. Eton’s long-serving head, the Reverend Cyril Alington, retired later the same year and his place was taken by Claude Aurelius Elliott, a Fellow and Senior Tutor of Jesus College, Cambridge. Unlike at St Ronan’s, at Eton the house system was everything. Neave’s house tutor was John Foster Crace, a classics teacher who had been there since 1901 but had only become a housemaster in 1923. He was ‘a reticent, reserved and inhibited bachelor with a reputation of being overfond of some of the boys’.

(#litres_trial_promo) However, he was a good teacher and ventured out of his reserve to produce Shakespeare on the school stage.

At Eton the emphasis was not just on academic brilliance but on sport and other ‘gentleman’s pursuits’ such as fencing and shooting. Scouting was also encouraged, including quasi-military activities such as signalling. As they grew older, boys joined the Officers’ Training Corps. Eton boys shot at Bisley, beating teams from the Scots Guards and the Grenadier Guards. The school was also a forcing house for politicians. In June 1929, a month after the General Election that brought Ramsay MacDonald into power at the head of an all-Labour Cabinet, the Eton College Chronicle recorded that seventy-six Old Etonians sat at Westminster, more than sixty of them as MPs. Predictably enough, only four of the MPs were Labour, while two were Liberal. Three Old Etonians were ministers in the MacDonald administration, including a young Hugh Dalton making his mark as Parliamentary Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office.

Public figures of the highest rank, including the King and international figures such as Mahatma Gandhi, paid regular visits to Eton. The atmosphere was unashamedly elitist. In Neave’s first year a particularly aggressive Etonian defined the expressive word ‘oick’ as ‘anybody who hasn’t been to Eton’. But when the school debating society considered whether ‘This House would welcome the resignation of the Government’, it was roundly defeated by forty-two votes to twenty, suggesting, perhaps, that the boys were more radical than their forebears.

The St Ronan’s magazine recorded that Airey ‘took remove at Eton, which is the highest form that a new boy who is not a scholar can go into’, and throughout his five years at the school he was competent rather than brilliant. He usually finished among the top half-dozen in his class and on one occasion won a book prize for academic effort, having, as Eton had it, been ‘sent up for good’ three times in a single term. Although the records suggest that he was a good runner, he did not shine at the school’s other traditional sports: cricket, racquets, fencing, soccer, rugby and rowing.

It might be thought that the momentous events away from the playing fields of Eton – the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression of the 1930s – would have passed him by. Indeed, the Eton College Chronicle of October 1930 suggested that the school was ‘terrifyingly remote from the ordinary concerns of life’, yet the same edition carried a spoof on a Communist takeover of the school, with references to ‘Herr Hitler’, and Old Etonians active in the higher reaches of politics would often return to talk to the school. In 1931, the fall of the Labour government amid economic collapse and the return of a national government under MacDonald greatly increased the number of Old Etonians at Westminster to 102, five of them in the Cabinet and nine more scattered in more junior ministerial jobs. It really did seem that being able to say one was an OE was a passport to power. Much has been said about the characteristics of an Old Etonian. A young OE might be considered arrogant, self-conscious, conceited, overconfident; the more mature species had become sober, active and intelligent, a leader of men; while in his dotage an OE might revert to arrogance and jingoism, but of a gentler kind. Neave was too reserved to fit the classic OE profile, but there was something of all those descriptions in him.

Before Neave left Eton he had an experience that few seventeen-year-old English boys of the period could expect to undergo. In September 1933 his parents sent him to Germany to brush up on the language. He was billeted with a family living in Nikolassee, west of Berlin, where he attended school with a boy of similar age who was a member of the Hitler Jugend. Adolf Hitler had become Chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933, when President von Hindenburg asked him to form a government as the leader of the largest single party, the National Socialists. Public and political opinion in Britain was slow to catch up with the terrifying prospect opening up in Continental Europe. Winston Churchill expressed admiration for ‘men who stood up for their country after defeat’. The Times asked sympathetically whether the street-orator would be an efficient ruler and the demagogue a statesman. They had their answer within weeks, when the Reichstag, the parliamentary building, was destroyed by fire. New decrees gave Hitler’s private army, the SA (Stürmabteilung), the power to gaol Jews and dissidents without trial. The first concentration camp opened at Dachau and by July of that year German citizenship was allowed only to members of the Nazi Party. Forced sterilisation of ‘inferior’ Germans was ordered. The terror had begun, but many in Britain believed that war could be averted through the League of Nations. Hitler withdrew from the League, yet still Germany remained a favourite holiday destination and Nazism even found admirers at home, particularly in the upper reaches of British society.

As a foreigner, Airey was excused from giving the Nazi salute when the teacher came into his class, but he was made to sit at the back, where he cut a bizarre figure in a ‘decadent’ yellow (Eton) tie with black spots and longer hair than his classmates. He felt something approaching contempt for the growing nazification of the school. Dietrich, the elder brother of the boy with whom he attended school, was impressed by Airey’s air of independence but warned that it was dangerous. On a railway platform at Nikolassee, Airey sniggered at a fat, brown-booted Nazi SA man. Years later, he recollected ‘the bloodshot pig-eyes of the stormtrooper glaring towards us’. Dietrich hastily manoeuvred him out of sight.

Dietrich was not a party member but he did belong to a sports club in nearby Charlottenburg. Airey joined as an honorary member. With his indifferent performances at school in mind, he volunteered for the relay race. A Festival of Sport was declared in September and his club was ‘advised’ by the authorities to field a team. At this relatively early stage of the Nazi takeover, Hitler had not stolen all sporting events as his own and marching in the torchlight procession was regarded as light-hearted and theatrical. Airey’s friend took him on the march in the face of official disapproval. He was dressed in ‘civvies’ and treated the occasion as something of a joke. His fellow marchers, however, did not: ‘As we joined the uniformed Nazis with their band, our mood changed,’ he recorded.

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘I felt as if I was being drawn into a vortex.’ The march began at ten in the evening. Neave was in the centre, alongside Dietrich and directly behind a contingent of SA troopers in brown shirts and swastika armbands. Down each side of the procession, burning torches blazed. Initially, Neave admitted, he found the grandiose event thrilling. Crowds watched, their faces shining with excitement and pride.

Sportsmen who had been joking began singing; the mood became religious and the marchers expectant. On their parade from Lustgarten down Berlin’s Unter den Linden, they passed the Royal Palace of Kaiser Wilhelm I and the Ministry of the Interior, home of Hermann Goering’s newly established Gestapo. When Neave broke step with his fellow marchers, Dietrich rounded on him, but it happened again before they reached their festival site, the Brandenburg Gate. ‘I found it difficult to keep in step,’ he admitted. ‘Something subconscious was drawing me away.’

(#litres_trial_promo) The gate was floodlit and festooned with Nazi flags, resembling, he recalled, some gateway to Valhalla. As they marched towards the burned out ruins of the Reichstag, bands played the Horst Wessel song (the Nazi anthem) and Neave was caught up in the emotional turmoil that prompted cynical and doubting fellow marchers alike to give the Nazi salute. ‘Some were on the verge of tears,’ he said. ‘Afterwards, I realised that they were lost forever to the Revolution of Destruction, whereas I would escape.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Massed bands prepared them for a half-hour speech by Reichssportkommissar von Tschammer und Osten. Airey, the product of a civilisation at odds with the hysteria of Fascism, was bored. The speech was tedious and hackneyed, ‘a maddening anticlimax’. While he fretted, all around him the young intelligentsia listened to the brown-shirted thug with rapt attention, breaking into ‘Deutschland über Alles’ when the speech was over. Neave’s reportage of these events has something of ex post facto reasoning about it. A British teenager, even one educated at Eton, pitchforked for the first time into a foreign country undergoing such convulsions, is unlikely to have come to such sophisticated conclusions. Recollecting these events twenty years later, Neave invested himself with a remarkably mature social and political intelligence, all of which certainly made for a better story. Had his liberal-minded mother known about the reality of Nazism, Airey mused, she would have recalled him instantly. Looking back, he realised that Hitler was preparing the young people of Germany for a war that he had always intended. His youthful eyes had been opened to the dangerous neurosis sweeping Germany but it would be seven more years before he was swept into the net of depravity. He returned to school for the remainder of his final year, to a Britain more perturbed about the controversial MCC bodyline tour of Australia than events in Berlin.

Eton in late 1933 must have seemed an anticlimax after the convulsions he had witnessed in Berlin. His school record shows flashes of distinction rather than consistency. After Eton, an orthodox journey through Oxford – he had chosen to go to Merton rather than follow his father to Magdalen – into the law seemed to beckon. Of good academic repute built initially on the classics, the Merton to which Neave went in the autumn of 1934 was still steeped in Victorian tradition. As the age of adulthood remained at twenty-one, the college stood in loco parentis to its undergraduates and took its responsibilities seriously. Discipline was officially strict, though the authorities turned a blind eye to certain misdemeanours. For the first year students lived in. They had agreeable but austere rooms. There were very few bathrooms: each set had a chamberpot, emptied by the college scout who acted as valet and housekeeper. A normal academic day began at 7.30 a.m. when the scout brought hot water for washing and shaving, and undergraduates then had to attend a roll-call at 8.00, ‘properly dressed’ in socks as well as gowns over their normal clothing. They signed their names in a register in a lecture room in Fellows’ Quad, under the watchful gaze of the day’s duty don. Attendance at matins in the college chapel was an acceptable alternative to roll-call.

After a day of lectures and tutorials, they were free for the evening. Drinking in Oxford’s pubs was forbidden and the rules were enforced by bowler-hatted ‘bulldogs’ (university proctors’ assistants) who toured the watering holes accosting suspects. College gates were closed at 9.00 p.m., and after that students had to ‘knock up’ the porter in his turreted fifteenth-century gatehouse to gain admission. They were fined sixpence after 10.30, and a shilling after ii .00. If an undergraduate had permission to stay out after midnight – rarely granted – he paid a fine of half a crown.

This was all quite expensive for the mid-thirties, when a young man at Oxford could live comfortably on £250 a year, so the curfew was regularly breached by climbing over the perimeter wall back into college. Indeed, it was one of Merton’s traditional sports. Reputedly, twenty-eight break-in routes existed, the most popular being over the wall in Merton Street into the college gardens and then through the loosened bars of a ground-floor set of rooms, where it was customary to leave small change on the table of the hapless undergraduate who occupied the rooms. Dons discreetly allowed the bars to remain loose.

Neave was undoubtedly one of the climbers, an unconscious rehearsal of his exploits at Colditz a few years later, and in captivity he must have mused on the irony of his position, where, for three years, he had perfected the art of breaking in rather than out. Once at Oxford, Neave quickly made his way to the worst company that Merton offered. He was elected to the exclusive Myrmidon Club, a group of undergraduates, never more than a dozen in number, who dedicated themselves to the good things of life. The club was founded in 1865, fancifully in emulation of George Bathmiteff, a Russian nobleman and Merton undergraduate who had dallied with a danseuse who wore a garter of purple and gold. Originally, its aims were to explore the Cherwell and other river systems, but with the advent of undergraduates like Lord Randolph Churchill in the 1870s the club soon became the haunt of young bloods. To perpetuate the memory of the danseuse, Myrmidons, named after the faithful followers of Achilles, wore purple dinner jackets faced with silver and white waistcoats edged with purple and gold. Their chief activities were eating and drinking, generally in each other’s rooms but also formally every term in their own dining rooms above a tailor’s shop in the High Street.

Within months of going up to Merton, Neave was inducted into the Myrmidons, at a meeting in the rooms of K.A. Merritt, a keen tennis player. Colin Sleeman, who was to become Captain of Boats and subsequently a distinguished lawyer and defence counsel at the Far East War Crimes Tribunal, was elected the same day. At that point the club numbered seven. They met regularly in Neave’s rooms for the following year, and in June 1936 he was elected secretary. The minutes show him to have been a conscientious but terse recorder of events. On 20 October 1936, the Myrmidons met in Mr Logie’s rooms, he wrote in a flowing (indeed, overflowing) Roman hand, and fixed the dates for lunch and dinner that term. It must have been a good meeting. Neave’s account, in a trembling hand, is full of crossings-out and emendations. He signed himself with a flourish and then underneath wrote ‘trouble’, without further explanation. On 5 February 1937, he recorded that the Myrmidons met in Mr Wells’s rooms and elected two new members. They organised lunch ‘for a date now lost in the mists of obscurity’, or perhaps the mists of Dom Perignon. The club now had nine members, and was ‘full’. The minute books are the only formal history of the Myrmidons’ activities, though they are still a legend for drinking and bad behaviour at Merton. Some idea of their academic application may be gained from the degrees posted in the college register. One got a fourth in geography, another a pass degree in mathematics; Merritt gained a third in history while Sleeman managed only a fourth in jurisprudence. The Myrmidons were capable of sottishness but were no more than undergraduate drunks. They invited Old Boys to their dinner, invariably held in London, where Neave had become a member of the Junior Carlton Club. They also aimed high in their guest invitations. As late as 1951, Winston Churchill, recently reinstalled as Prime Minister, wrote regretting that he could not attend their dinner because the pressure of affairs was ‘considerable’.

The Myrmidons also gained an eccentric reputation for literary interests, chiefly through Max Beerbohm and his friends who had been members in the 1890s. The Myrmidons are assumed to be the model for the Junta in Beerbohm’s gentle, witty Oxford novel Zuleika Dobson. In spite of being known as the ‘most virile’ of Merton’s clubs, they also had a cultured side, which showed itself most strongly in amateur dramatics. The Myrmidons scorned OUDS – the self-esteeming Oxford University Dramatic Society – in favour of Merton Floats, the college’s own theatre group, founded in 1929 by two undergraduates, Giles Playfair and E.K. Willing-Denton, the latter a ‘prodigiously extravagant and generous’ young man. This was, Playfair later recollected, a time of festive teas, luncheons, dinners, suppers and moonlight trips on the river followed by climbing over the wall into college. Willing-Denton, who spent his entire allowance in the first month, was noted for his ten-course luncheons. He and Playfair persuaded actors of the calibre of Hermione Baddeley to come down to Oxford, and Merton Floats enjoyed a succès d’estime in the mid-war years when the social scene was at its height. In 1936, Neave was secretary of Floats and his friend Merritt was president. Sleeman was the grandly titled front-of-house manager. They put on two plays: In The Zone, a one-act play by Eugene O’Neill set on the fo’c’sle of a British tramp steamer in 1915, in which Neave played the role of Smitty; and Savonarola, a play of the 1890s attributed to Ladbroke Brown, in which Neave appeared as Pope Julius II. Neave also found time to make three speeches at the Oxford Union, of which no record remains. On one of these occasions he found himself debating the merits of the previous week’s motion.

It was an altogether engaging life. Neave later admitted that he did little academic work at Oxford and was obliged to work feverishly at the law before his finals in order to get a degree. He graduated in 1938 with a third in jurisprudence and a BA. ‘The climax of my “Oxford” education was a champagne party on top of my college tower when empty bottles came raining down to the grave peril of those below,’ he wrote.

(#litres_trial_promo) He remained thankful in adult life for the kindness and forbearance shown by his college during those profligate years. Life was never to be so insouciant again.

3 King and Country (#ulink_04c1e838-a60b-525f-8892-e4f1f30501a1)

In the febrile pre-war atmosphere of the 1930s, Oxford shared in the political polarisation that shook society at large. As early as February 1933, months before Neave went up from Eton, the Oxford Union carried a motion ‘This House will under no circumstances fight for King and Country’. The vote was unambiguous: 275 to 153. Most undergraduates thought no more about their casual pacifism, but Winston Churchill expressed nausea at this ‘abject, squalid, shameless avowal’. ‘One can almost feel the contempt upon the lips of the manhood of Germany,’ he added disdainfully.

Neave was not among the fainthearts. Unlike most of his university contemporaries he had seen the Nazis at first hand and did not like what he saw. However, unlike some of his contemporaries – including Denis Healey, a future Defence and Foreign Secretary – he did not embrace the fashionable left. He was emphatically a patriot and willing to fight for King and Country. Furthermore, he believed that a war with Germany was inevitable. In 1933, while still at Eton, Neave had written a prize-winning political essay analysing the probable consequences of Hitler’s rise to power and predicting the likelihood of war. Leonard Cheshire recalled: ‘On arriving at Oxford he bought and read the full works of Clausewitz, and when being asked why, answered that since war was coming, it was only sensible to learn as much as possible about the art of waging it.’

(#litres_trial_promo) To this alarming intellectual precocity, Neave, still in his teens, added military intent. While those about him flirted with the Young Communist League, he joined the Territorial Army at the tender age of nineteen. ‘It was fashionable in some quarters to declare that no one but a very stupid undergraduate would fight for his King and Country,’ he remembered later. ‘To be a Territorial was distinctly eccentric. Military service was a sort of archaic sport as ineffective as a game of croquet on a vicarage lawn and more tiresome.’

(#litres_trial_promo) He despised the phrase ‘playing at soldiers’, and took some comfort in the fact that those he contemptuously referred to as ‘decadents, fantastics and intellectuals’ were fighting for their very lives within a few short years.

In the meantime, his reading of Clausewitz was of little help on manoeuvres with an infantry battalion in the TA summer camp on the Wiltshire Downs. Neave remembered how he lay blissfully in the grass, a wooden Lewis gun by his side, listening for the sound of blank cartridges but concentrating more on the butterflies, identifying a small copper, a fritillary and a clouded yellow as his platoon clowned around on the edge of a chalk pit. ‘We were not prepared for war. We never are,’ he reflected. His daydreaming was rudely interrupted by a full brigadier kitted out for the First World War who shouted ‘Lie down there!’ as Neave began to stand up, feeling ridiculous in plus fours and puttees covered in chalk and grass. The imaginary conflict continued under a blazing sun. In the post-mortem on this ‘battle’, the brigadier raged at Neave, accusing him of choosing an exposed position for his men. Why had he allowed his left flank to go unprotected? Neave answered, with more nerve than diplomacy: ‘There was an imaginary platoon on his left flank, sir, I posted it there.’ The brigadier was deflated and Neave was a popular subaltern in the mess that night. If he was aware that such manoeuvres were poor preparation for the gathering storm he was nonetheless proud to receive in 1935 a registered envelope from the War Office informing him that His Majesty King George V sent greeting to his trusted and well-beloved Airey Neave and appointed him to a commission as second lieutenant in his Territorial Army.

After graduating, Neave went up to London to read for the Bar. His first placement was in 1938 in the office of an old-fashioned solicitor’s in the City. Here he learned the basics of law in action. It had its entertaining moments. One summer evening found him, kitted out in bowler hat and umbrella, accompanied by a junior clerk, serving an injunction on a group of thespians in a church hall in Cricklewood, north London. The play, by a local author, libelled Neave’s client and the High Court injunction he served on the producer forbade its performance. The producer read the long legal document tied with green string, a familiar sight to journalists but evidently a great shock to amateur performers. ‘You can’t do this to us,’ he expostulated. ‘It’s against the law!’ Echoes of this farcical scene resounded in Neave’s memory years later, when he was called on to serve the indictment to Nazi war criminals at Nuremberg.

Neave moved on to become a pupil in a barrister’s chambers in Farrar’s Building in the Temple, close to Temple Church, but beneath the superficial gaiety of the capital and the debutante season, war was rapidly approaching. In the late summer of 1939, a matter of days before war was declared, Anthony Eden, Minister for War, announced on the radio a doubling of the size of the Territorial Army. Airey and his cousin Julius were listening to the broadcast at Mill Green Park. Airey immediately proposed that they go and join up and the pair cycled off to the local Drill Hall in nearby Fryerning Lane. Julius Neave remembers that the recruiting officer said ‘That’s very nice of you. So, would you like to be soldiers, or officers?’ They replied: ‘Given the choice – officers!’ Both had what was known as a ‘Certificate A’, meaning that they had passed a proficiency test with the Officer Training Corps at school. As a second lieutenant in the TA, Neave would quickly have been called up in any event.

He was posted to an anti-aircraft Searchlight Regiment and spent an unromantic six months in a muddy field in Essex learning his trade, before being dispatched to a searchlight training regiment in Hereford. It was hardly Clausewitz. An impatient Neave preferred to be in the field, like Rupert Brooke and his other war heroes of history. He was soon to have all the action he wanted, and more. In February 1940 he was sent as a troop commander to Boulogne, where the uneasy peace of the ‘phoney war’ reigned. Lieutenant Neave was placed in charge of an advance party of ‘rugged old veterans’ from the First World War, mostly industrial workers with some clerks and professional men, a ‘vocal and democratic lot’ who did not consider themselves crack soldiers but made up for lack of infantry training with a willingness to fight. They were equipped with rifles (though many had never fired one), old Lewis guns, a few Bren guns and the new Boys anti-tank rifle which none of them knew how to use. Neave’s troop, part of the Second Battery of the 1st Searchlight Regiment, was tasked mainly with operating searchlights in fields around large towns, dazzling bombers and aiding anti-aircraft gunners. The searchlight soldiers were held in little esteem, one Guards officer describing their contribution as ‘quite Christmassy’. An indignant Neave kept his counsel and waited for the underdogs to show their mettle.

He did not have long to wait. Military folklore says that Hitler’s decision to invade the Low Countries and France was made over lunch with von Manstein, Field Marshal of the Wermacht Gerd von Rundstedt’s chief of staff, over lunch on 17 February 1940. On 2 April, the Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain confidently told the Commons: ‘Hitler has missed the bus.’ Early in the morning of 10 May, the Nazi Blitzkrieg on the Low Countries and France began. Under the brilliant direction of General Heinz Guderian, German panzer divisions smashed their way through the Ardennes, overrunning Belgium and striking deep into France. Within five days, Paul Reynaud, the French Prime Minister, was telephoning Churchill to say: ‘We have been defeated.’ It was an appalling prospect. The British Expeditionary Force numbering hundreds and thousands of men, sent to oppose any German invasion, was in danger of being surrounded and cut off in northwestern France. The war for Europe was in danger of being lost before it had begun. Still, service chiefs in London judged that Hitler’s lines of communication had become so extended that a frontal attack on the Channel ports was unlikely. ‘It was not to be believed,’ wrote war historian Michael Glover, ‘that, within two or three days, they could threaten, far less capture, Boulogne and Calais. A week earlier the idea would have appeared equally fantastic to the German High Command.’

(#litres_trial_promo)