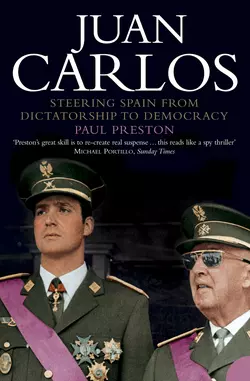

Juan Carlos: Steering Spain from Dictatorship to Democracy

Paul Preston

A powerful biography of Spain’s great king, Juan Carlos, by the pre-eminent writer on 20th-century Spanish history.There are two central mysteries in the life of Juan Carlos, one personal, the other political.The first is the apparent serenity with which he accepted that his father had surrendered him, to all intents and purposes, into the safekeeping of the Franco regime. In any normal family, this would have been considered a kind of cruelty or, at the very least, baleful negligence. But a royal family can never be normal, and the decision to send the young Juan Carlos away from Spain was governed by a certain ‘superior’ dynastic logic.The second mystery lies in how a prince raised in a family with the strictest authoritarian traditions, who was obliged to conform to the Francoist norms during his youth and educated to be a cornerstone of the plans for the reinforcement of the dictatorship, eventually sided so emphatically and courageously with democratic principles.Paul Preston – perhaps the greatest living commentator on modern Spain – has set out to address these mysteries, and in so doing has written the definitive biography of King Juan Carlos. He tackles the king’s turbulent relationship with his father, his cloistered education, his bravery in defending Spain’s infant democracy after Franco’s death and his immense hard work in consolidating parliamentary democracy in Spain. The resulting biography is both rigorous and riveting, its vibrant prose doing justice to its vibrant subject. It is a book fit for a king.

JUAN CARLOS

A People’s King

PAUL PRESTON

In Memory of José María Coll Comín

CONTENTS

Cover (#u89aeb982-7045-5ab7-ba38-7d7a0081f8da)

Title Page (#u2a68f1d3-0cf0-5536-a844-84fed95aa937)

CHAPTER ONE: (#uec37d760-fd80-52db-a4a0-1135a211e6ac)In Search of a Lost Crown 1931–1948

CHAPTER TWO: (#ud3f2009d-6c87-5d28-9259-cf7fb46cdb50)A Pawn Sacrificed 1949–1955

CHAPTER THREE: (#u27a2bb3a-5743-58ed-ace0-3039858ff7df)The Tribulations of a Young Soldier 1955–1960

CHAPTER FOUR: (#u6c560511-67b9-533b-8795-e025c1c974ef)A Life Under Surveillance 1960–1966

CHAPTER FIVE: (#litres_trial_promo)The Winning Post in Sight 1967–1969

CHAPTER SIX: (#litres_trial_promo)Under Suspicion 1969–1974

CHAPTER SEVEN: (#litres_trial_promo)Taking Over 1974–1976

CHAPTER EIGHT: (#litres_trial_promo)The Gamble 1976–1977

CHAPTER NINE: (#litres_trial_promo)More Responsibility, Less Power: the Crown and Golpismo 1977–1980

CHAPTER TEN: (#litres_trial_promo)Fighting for Democracy 1980–1981

CHAPTER ELEVEN: (#litres_trial_promo)Living in the Long Shadow of Success 1981–2002

BIBLIOGRAPHY (#litres_trial_promo)

NOTES (#litres_trial_promo)

INDEX (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE In Search of a Lost Crown 1931–1948 (#ulink_98d486ff-0456-5998-abc7-fd961d717d61)

There are two central mysteries in the life of Juan Carlos, one personal, the other political. The key to both lies in his own definition of his role: ‘For a politician, because he likes power, the job of King seems to be a vocation. For the son of a King, like me, it’s something altogether different. It’s not a question of whether I like it or not. I was born to it. Ever since I was a child, my teachers have taught me to do things that I didn’t like. In the house of the Borbóns, being King is a profession.’

(#litres_trial_promo) In those words lies the explanation for what is essentially a life of considerable sacrifice. How else is it possible to explain the apparent equanimity with which Juan Carlos accepted the fact that his father, Don Juan, to all intents and purposes sold him into slavery? In 1948, in order to keep the possibility of a Borbón restoration in Spain on Franco’s agenda, Don Juan permitted his son to be taken to Spain to be educated at the will of the Caudillo. In a normal family, this act would be considered to be one of cruelty, or at best, of callous irresponsibility. But the Borbón family was not ‘normal’ and the decision to send Juan Carlos away responded to a ‘higher’ dynastic logic. Nevertheless, the tension between the needs of the human being and the needs of the dynasty lies at the heart of the story of the distance between the fun-loving boy, Juanito de Borbón, and the rather stiff prince Juan Carlos with his perpetually sad look. The other, rather more difficult puzzle, is how a prince emanating from a family with considerable authoritarian traditions, obliged to function within ‘rules’ invented by General Franco, and brought up to be the keystone of a complex plan for the continuity of the dictatorship should have committed himself to democracy.

The mission to which Juan Carlos was born, and which would take precedence over any personal life, was to make good the disaster that had struck his family in 1931. On 12 April 1931, nationwide municipal elections had seen sweeping victories for the anti-monarchical coalition of Republicans and Socialists. King Alfonso XIII, an affable and irresponsible rake, had earned considerable unpopularity for his part in the great military disaster at Annual in Spain’s Moroccan colony in 1921. Even more, his collusion in the establishment of a military dictatorship in 1923 had sealed his fate. When he learned that his generals were not inclined to risk civil war in order to overturn the election results, he gave a note to his Prime Minister, Admiral Aznar. ‘The elections celebrated on Sunday show me clearly that today I do not have the love of my people. My conscience tells me that this wrong turn will not last forever, because I always tried to serve Spain, my every concern being the public interest even in the most difficult moments.’ He went on to say, ‘I do not renounce any of my rights.’ In that statement can be distantly discerned the process whereby Spain lost a monarchy, suffered a dictatorship and regained a monarchy. The hidden message to his supporters was that they should create a situation in which the Spanish people would beg him to return. This would be the seed from which the military uprising of 1936 would grow. However, its leader, General Franco, despite being a self-proclaimed monarchist and one-time favourite of Alfonso XIII, would not call him back to be King. One reason perhaps was that Alfonso XIII also said, ‘I am King of all Spaniards, and also a Spaniard.’ Those words would often be used by Alfonso’s son and heir, Don Juan, and would occasion the sarcastic mirth of the dictator. They would be used again on the day of the coronation of King Juan Carlos.

(#litres_trial_promo)

On 14 April 1931, on his painful journey from Madrid, via Cartagena, into exile in France, the King was accompanied by his cousin, Alfonso de Orleáns Borbón. The Queen, Victoria Eugenia of Battenburg, a granddaughter of Queen Victoria, was escorted into exile by her cousin, Princess Beatrice of Saxe-Coburg, the wife of Alfonso de Orleáns Borbón.

(#litres_trial_promo) The government of the Republic quickly published a decree depriving the exiled King of his Spanish citizenship and the royal family of its possessions in Spain. After a short sojourn in the Hôtel Meurice on the rue de Rivoli in Paris, the royal family moved to a house in Fontainebleau. There, Alfonso XIII received delegations of conspirators against the Second Republic and gave them his approval and encouragement.

(#litres_trial_promo)

In addition to the blow of exile, Alfonso XIII suffered considerable personal sadness. Without the scenery of the palace and the supporting cast of courtiers, the emptiness of his relationship with Victoria Eugenia was increasingly exposed. Not long after their arrival at Fontainebleau, the King remonstrated with the Queen about her closeness to the Duke and Duchess de Lécera who had accompanied her into exile. The marriage of the Duke, Jaime de Silva Mitjans, and the lesbian Duchess, Rosario Agrelo de Silva, was a sham but they stayed together because both were in love with the Queen. Despite persistent rumours, which niggled at Alfonso XIII, the Queen always vehemently denied that she and the Duke had been lovers. Nevertheless, when the bored Alfonso XIII took a new lover in Paris and the Queen in turn remonstrated with him, he tried to divert the onslaught by throwing in her face the alleged relationship with Lécera. She denied it but, as tempers rose, he demanded that she choose between himself and Lécera. Fearful of losing their support, on which she had come to rely, she replied, by her own account, with the fateful words, ‘I choose them and never want to see your ugly face again.’

(#litres_trial_promo) There would be no going back.

Another reason for Alfonso’s long-deteriorating relationship with Victoria Eugenia was the fact that she had brought haemophilia into the family. The couple’s eldest son, Alfonso, was of dangerously delicate health. He was haemophilic and, according to his sister, the Infanta Doña Cristina, ‘the slightest knock caused him terrible pain and would paralyse part of his body.’ He often could not walk unaided and lived in constant fear of a fatal blow. When the recently appointed Director General of Security, Emilio Mola, made his courtesy visit to the palace in February 1930, he was shocked: ‘I also visited the Príncipe de Asturias [the Spanish equivalent of the Prince of Wales] and only then did I fully understand the intimate tragedy of the royal family and comprehend the pain in the Queen’s face. He received me standing up and had the kindness to ask me to sit. Then he tried to get up to see me out and it was impossible: a flash, of anguish and of resignation, passed across his face.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Alfonso formally renounced his right to the throne on n June 1933 in return for his father’s permission to contract a morganatic marriage with an attractive but frivolous girl he had met at the Lausanne clinic where he was receiving treatment. Edelmira Sampedro y Robato was the 26-year-old daughter of a rich Cuban landowner.

Immediately following his eldest son’s renunciation of his dynastic rights, Alfonso XIII arranged for a number of prominent monarchists to put pressure on his second son, Don Jaime, to follow his brother’s example. Don Jaime was deaf and dumb – the result of a botched operation when he was four. Cut off from the world, both by dint of his royal status and his deafness, he had grown into a singularly immature young man. The monarchist leader José Calvo Sotelo persuaded him that his inability to use the telephone would significantly diminish his capacity to take part in anti-Republican conspiracies.

(#litres_trial_promo) Alfonso married Edelmira in Lausanne, in the presence of his mother and two sisters. Neither his father nor three brothers deigned to attend. On the same day, in Fontainebleau, 21 June 1933, Don Jaime, who was single at the time, finally agreed to renounce his rights to the throne, as well as those of his future heirs. The renunciation was irrevocable and would be ratified on 23 July 1945. In spite of this, he would later contest its validity, thereby complicating Juan Carlos’s rise to power.

(#litres_trial_promo)

In his 1933 letter to his father, Don Jaime wrote: ‘Sire. The decision of my brother to renounce, for himself and his descendants, his rights to the succession of the crown has led me to weigh the obligations that thus fall on me … I have decided on a formal and explicit renunciation, for me and for any descendants that I might have, of my rights to the throne of our fatherland.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Don Jaime would, in any case, have lost his rights when, in 1935, he also made a morganatic marriage, to an Italian, Emmanuela Dampierre Ruspoli, who although a minor aristocrat was not of royal blood. It was not a love match and would end unhappily.

(#litres_trial_promo)

In the summer of 1933, during a royal skiing holiday in Istria, Alfonso’s fourth son, Don Gonzalo – who also suffered from haemophilia – was involved in a car crash and died as a result of an internal haemorrhage.

(#litres_trial_promo) His first son fared little better. After his allowance was slashed by the exiled King, Alfonso’s marriage to Edelmira did not survive. They divorced in May 1937. Two months later, he married another Cuban, Marta Rocafort y Altuzarra, a beautiful model. The marriage lasted barely six months and they were also divorced, in January 1938. Having fallen in love with Mildred Gaydon, a cigarette girl in a Miami nightclub, Alfonso was on the point of marrying for a third time when tragedy once more struck the Borbón family. On the night of 6 September 1938, after leaving the club where Mildred worked, he too was involved in a car crash and, like his brother Gonzalo, died of internal bleeding.

(#litres_trial_promo)

As a result of the successive renunciations of Alfonso and Jaime, the title of Príncipe de Asturias fell upon Alfonso XIII’s third son, the 20-year-old Don Juan. When he received his father’s telegram informing him of this, Don Juan was a serving officer in the Royal Navy on HMS Enterprise, anchored in Bombay. Because he realized that his new role would eventually involve him leaving his beloved naval career, he accepted only after some delay. In May 1934, he was promoted to sub-lieutenant and in September, he joined the battleship HMS Iron Duke. In March 1935, he passed the examinations in naval gunnery and navigation which opened the way to his becoming a lieutenant and being eligible to command a vessel. However, that would mean renouncing his Spanish nationality, something he was not prepared to do. His uncle, King George V, granted him the rank of honorary Lieutenant RN.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Don Juan did not emulate his elder brothers’ disastrous marriages. On 13 January 1935, at a party given by the King and Queen of Italy on the eve of the marriage of the Infanta Doña Beatriz to Prince Alessandro Torlonia, Prince di Civitella Cesi, Don Juan had met the 24-year-old María de las Mercedes Borbón Orléans. Having faced the problem of his eldest son’s unsuitable marriage, Alfonso XIII was delighted when Don Juan began to fall in love with a statuesque princess who was descended from the royal families of Spain, France, Italy and Austria. They were married on 12 October 1935 in Rome. Several thousand Spanish monarchists made the trip to the Italian capital and turned the ceremony into a demonstration against the Spanish Republic. By this time, Queen Victoria Eugenia had long since left Alfonso XIII and she refused to attend the wedding.

(#litres_trial_promo) The newly appointed Príncipe de Asturias and his new bride settled at the Villa Saint Blaise in Cannes in the south of France. There, he quickly made contact with the leading monarchist politicians who were involved in anti-Republican plots.

Unsurprisingly, when on the evening of 17 July 1936 units of the Spanish Army in Morocco rebelled against the Second Republic, the coup d’état was enthusiastically welcomed by both Don Juan and his father. They avidly followed the progress of the military rebels on the radio, particularly through the lurid broadcasts of General Queipo de Llano. A group of Don Juan’s followers, who had been avid conspirators against the Republic, including Eugenio Vegas Latapié, Jorge Vigón, the Conde de Ruiseñada and the Marqués de la Eliseda, felt that it would be politically prudent for him to be seen fighting on the Nationalist side. He had already discussed the matter with his aide-de-camp, Captain Juan Luis Roca de Togores, the Vizconde de Rocamora. Don Juan left his home for the front for the first time on 31 July 1936, despite the fact that only the previous day Doña María de las Mercedes had given birth to their first child, a daughter, Pilar. His mother, Queen Victoria Eugenia, was present, having come to Cannes for the birth. To the delight of Don Juan’s followers, she declared: ‘I think it is right that my son should go to war. In extreme situations, such as the present one, women must pray and men must fight.’ Pleasantly surprised by this, they were, nevertheless, worried about the possible reaction of Alfonso XIII who was holidaying in Czechoslovakia. However, when Don Juan telephoned him, he too agreed enthusiastically, saying, ‘I am delighted. Go, my son, and may God be with you!’

The following day, 1 August, the tall and good-natured Don Juan duly crossed the French border into Spain in a chauffeur-driven Bentley, ahead of a small convoy of cars carrying his followers. They arrived in Burgos determined to fight on the Nationalist side. However, the rebel commander in the north, the impulsive General Emilio Mola, was in fact an anti-monarchist. Without consulting his fellow generals, he abruptly ordered the Civil Guard to ensure that Don Juan left Spain immediately. This incident inclined many deeply monarchist officers to transfer their long-term political loyalty from Mola to Franco.

(#litres_trial_promo)

After his return to Cannes, the presence of important supporters of the Spanish military rebellion attracted the attention of local leftists. Groups of militants of the Front Populaire took to gathering outside the Villa Saint Blaise each evening and shouting pro-Republican slogans. Fearful for the security of his family – his wife was pregnant once more – Don Juan decided to move to Rome. His father was already resident there and the Fascist authorities would ensure that there would be no unpleasantness of the kind that had marred their stay in France. At first they lived in the Hotel Eden until, at the beginning of 1937, they moved into a flat on the top floor of the Palazzo Torlonia in Via Bocca di Leone. The palazzo was the home of Don Juan’s sister Doña Beatriz and Alessandro Torlonia.

(#litres_trial_promo)

At the beginning of January 1938, Doña María de las Mercedes was coming to the culmination of her second pregnancy. However, when Don Juan was invited to go hunting, her doctor assured him that it was safe to go as the baby would not appear for at least another three weeks. Doña María was at the cinema with her father-in-law, Alfonso XIII, when her labour pains began. Juan Carlos was born at 2.30 p.m. on 5 January 1938 at the Anglo-American hospital in Rome. He was one month premature. When Doña María was taken to hospital, her lady-in-waiting, Angelita Martínez Campos, the Vizcondesa de Rocamora, called Don Juan back to Rome by sending him a telegram which read ‘Bambolo natto’ (Baby born). On receiving the telegram, he set off, driving so furiously that he broke an axle spring on his Bentley. Arriving before his son, Alfonso XIII played a trick. As he welcomed Don Juan, he held in his arms a Chinese baby boy – who had been born in an adjoining room to the secretary at the Chinese Embassy. Don Juan knew at once that the child was not his, yet, on seeing his own son, he confessed later, for a moment, he would have almost preferred the Chinese baby. Doña María, unlike most mothers, did not think her baby was the most beautiful creature on earth. She later recalled that, ‘The poor thing was a month premature and had big bulging eyes. He was ugly, as ugly as sin! It was awful! Thank God he soon sorted himself out.’ The blond baby weighed three kilograms. The earliest photographs of Juan Carlos were taken, not at his birth, but when he was already five months old.

(#litres_trial_promo) Despite his mother’s initial alarm, Juan Carlos did not remain ‘ugly’ for long. His good looks would always be a major asset – they would, indeed, be a major factor in his eventually winning the approval of Queen Frederica of Greece, his future mother-in-law.

(#litres_trial_promo)

On 26 January 1938, the child was baptized at the chapel of the Order of Malta in the Via Condotti in Rome. The choice of the chapel was made because of its proximity to the Palazzo Torlonia, where the reception took place. The baptism ceremony was conducted by Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, then Secretary of State to the Vatican, and the future Pope Pius XII. At the christening, the baby Prince’s godmother was his paternal grandmother, Queen Victoria Eugenia. His godfather in absentia was the Infante Carlos de Borbón-Dos-Sicilias, his maternal grandfather. As a general in the Nationalist army, at the time engaged in the battle for Teruel, he was unable to travel to Rome. He was represented at the baptism by Don Juan’s elder brother, Don Jaime. Very few Spaniards were able to travel to Rome for the occasion and the birth of the Prince went virtually unnoticed even in the Nationalist zone of Spain.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The boy was christened with the names Juan, for his father; Alfonso, for his paternal grandfather, the exiled King Alfonso XIII; and Carlos, for his maternal grandfather, Carlos de Borbón-Dos-Sicilias. Juan Carlos’s family and friends would, however, usually call him Juanito, at first because of his youth and later in order to distinguish him from his father. It was only after his emergence as a public figure that he began to use the name of Juan Carlos. There were, of course, political reasons behind the choice of the Prince’s public name. Don Juan told his lifelong adviser, the monarchisi intellectual, Pedro Sainz Rodríguez, that the choice was Franco’s. The idea may also have emanated from the conservative monarchist Marqués de Casa Oriol, José María Oriol, although the future King himself could not remember this with any certainty.

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘Juan Carlos’ would distinguish the Prince from his father, Don Juan, and perhaps ingratiate him with the ultra-conservative Car lists whose pretender always carried the name Carlos. The elimination of his middle name, Alfonso, would certainly have been to Franco’s liking since it was central to the Caudillo’s rhetoric that it was the misguided liberalism of Alfonso XIII that had rendered the Spanish Civil War inevitable.

Don Juan de Borbón continued to harbour a desire to take part in the Nationalist war effort. He had written to the Generalísimo on 7 December 1936 and respectfully requested permission to join the crew of the battlecruiser Baleares which was then nearing completion: ‘… after my studies at the Royal Naval College, I served for two years on the Royal Navy battlecruiser HMS Enterprise, I completed a special artillery course on the battleship HMS Iron Duke and, finally, before leaving the Royal Navy with the rank of Lieutenant, I spent three months on the destroyer HMS Winchester.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Although the young Prince promised to remain inconspicuous, not to go ashore at any Spanish port and to abstain from any political contact, Franco was quick to perceive the dangers both immediate and distant. If Don Juan were to fight on the Nationalist side, intentionally or otherwise he would soon become a figurehead for the large numbers of monarchists, especially in the Army, who, for the moment, were content to leave Franco in charge while waiting for victory and an eventual restoration of Alfonso XIII. There was the danger that the Alfonsists would become a distinct group alongside the Falangists and the Carlists, adding their voice to the political diversity that was beginning to come to the surface in the Nationalist zone. The execution of José Antonio Primo de Rivera, founder of the Falange, in a Republican prison had solved one problem, and Franco was now in the process of cutting down the Carlist leader, Manuel Fal Conde. He did not need Don Juan de Borbón emerging as a monarchist figurehead.

Franco’s response was a masterpiece of duplicity. He delayed some weeks before replying to Don Juan. ‘It would have given me great pleasure to accede to your request, so Spanish and so legitimate, to serve in our Navy for the cause of Spain. However, the need to keep you safe would not permit you to live as a simple officer since the enthusiasm of some and the officiousness of others would stand in the way of such noble intentions. Moreover, we have to take into account the fact that the place which you occupy in the dynastic order and the consequent obligations impose upon us all, and demand of you the sacrifice of desires which are as patriotic as they are noble and deeply felt, in the interests of the Patria … It is not possible for me to follow the dictates of my soldier’s heart and to accept your offer.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Thus, with apparent grace, he deflected a dangerous offer.

Franco also managed to squeeze considerable political capital out of so doing. He arranged for word to be circulated in Falangist circles that he had prevented the heir to the throne from entering Spain because of his own commitment to the future Falangist revolution. He also publicized what he had done and gave reasons aimed at consolidating his own position among the monarchists. ‘My responsibilities are great and among them is the duty not to put his life in danger, since one day it may be precious to us … If one day a King returns to rule over the State, he will have to come as a peace maker and should not be found among the victors.’

(#litres_trial_promo) The cynicism of such sentiments would be fully appreciated only after nearly four decades had elapsed, during which Franco dedicated his efforts to institutionalizing the division of Spain into victors and vanquished and failing to restore the monarchy. When the Baleares was sunk on 6 March 1938, Franco is said to have commented with an ironic smile, ‘And to think that Don Juan de Borbón wanted to serve on board.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

In the meantime, in the autumn of 1936, believing that the military uprising would, if victorious, culminate in a restoration of the monarchy, Alfonso XIII had telegraphed Franco to congratulate him on his successes. In his suite in the Gran Hotel in Rome, the King kept a huge map of Spain marked with little flags with which he obsessively followed the progress of the rebel troops on various fronts.

(#litres_trial_promo) In his confidence that Franco would repay earlier favours by restoring the monarchy, he misjudged his man. Had he and his son been a little more suspicious, they might have been alarmed to note that the newly installed Head of State had already begun to comport himself as if he were the King rather than simply the praetorian guard responsible for bringing back the monarchy. With the support of the Catholic Church, which had blessed the Nationalist war effort as a religious crusade, Franco began to project himself as the saviour of Spain and the defender of the universal faith, both roles associated with the great kings of the past. Religious ritual was used to give legitimacy to his power as it had to those of the medieval kings of Spain. The liturgy and iconography of his regime presented him as a holy crusader; he had a personal chaplain and he usurped the royal prerogative of entering and leaving churches under a canopy.

The confidence in himself and his office generated by such ceremonial was revealed when Franco celebrated the first year of his Movimiento. His broadcast speech was, according to his cousin, entirely written by himself. He spoke in terms which suggested that he placed himself far higher than the Borbón family, as a providential figure, the very embodiment of the spirit of traditional Spain. He attributed to himself the honour of having saved ‘Imperial Spain which fathered nations and gave laws to the world’.

(#litres_trial_promo) On the same day, an interview with the Caudillo was published in the monarchist newspaper ABC. In it, he announced the imminent formation of his first government. Asked if his references to the historic greatness of Spain implied a monarchical restoration, he replied truthfully while managing to give the impression that this was his intention, ‘On this subject, my preferences are long since known, but now we can think only of winning the War, then it will be necessary to clean up after it, then construct the State on firm bases. While all this is happening, I cannot be an interim power.’

For Franco, and indeed many of his supporters within the Nationalist zone, the monarchy of Alfonso XIII was irrevocably stigmatized by its association with the constitutional parliamentary system. In his interview, he declared that, ‘If the monarchy were to be one day restored in Spain, it would have to be very different from the monarchy abolished in 1931 both in its content and, though it may grieve many of us, even in the person who incarnates it.’ This was profoundly humiliating for Alfonso XIII, all the more so coming from a man whose career he had promoted so assiduously.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The Caudillo’s attitude to the exiled King, and by implication, to the Borbón family, was underlined in a harshly dismissive letter sent to Alfonso XIII on 4 December 1937. The King, having recently donated one million pesetas to the Nationalist cause, had written to Franco expressing his concern that the restoration of the monarchy seemed to be low on his list of priorities. The Generalísimo replied coldly, insinuating that the problems which caused the Civil War were of the King’s making and outlining both the achievements of the Nationalists and the tasks remaining to be carried out after the War. Expanding on his ABC interview, the Caudillo made it clear that Alfonso XIII could expect to play no part in that future: ‘the new Spain which we are forging has so little in common with the liberal and constitutional Spain over which you ruled that your training and old-fashioned political practices necessarily provoke the anxieties and resentments of Spaniards.’ The letter ended with a request that the King look to the preparation of his heir, ‘whose goal we can sense but which is so distant that we cannot make it out yet’.

(#litres_trial_promo) It was the clearest indication yet that Franco had no intention of ever relinquishing power, yet the epistolary relationship between Franco and the exiled King remained surprisingly smooth. (Indeed, in December 1938, Franco revoked the Republican edict that had deprived the King of his Spanish citizenship and the royal family of its properties.) Throughout the Civil War, after each victory, the Generalísimo had sent a telegram to Alfonso XIII and, in turn, received congratulatory messages from both the exiled King and his son. However, after the final victory, and the capture of Madrid, Franco had not done so. The outraged Alfonso XIII rightly took this to mean that Franco had no intention of restoring the monarchy.

(#litres_trial_promo)

If the future of Alfonso XIII’s heir was unclear to Franco, even less certain was that of his grandson, Juan Carlos. For the first four and a half years of his life, the boy lived with his parents in Rome. Soon after his birth the family moved from the modest flat on the top floor of the Palazzo Torlonia in Via Bocca di Leoni to the four-storey Villa Gloria, at 112 Viale dei Parioli in the elegant Roman suburb of Parioli.

(#litres_trial_promo) This was a happy time for the Borbóns – a period during which it was possible to live as a relatively normal, as opposed to a royal, family. Juan Carlos’s younger sister Margarita was born blind on 6 March 1939. Even so, the degree of family warmth was limited. All three children were looked after by two Swiss nannies, Mademoiselles Modou and Any, under the supervision, not of their mother but of the Vizcondesa de Rocamora. The young Prince was often taken out for walks by his parents or by his nannies, sometimes to the Palazzo Torlonia, sometimes to the private park of the Pamphili family or to the park of Villa Borghese. Don Juan showed some affection for his eldest son, often carrying him in his arms when they visited Alfonso XIII at the Gran Hotel.

However, such signs of warmth were rare. The young Prince was soon being schooled in the harsh lesson that his central purpose in life was to contribute in some way to the mission of seeing the Borbón family back on the throne in Spain. Don Juan had already started to make demands that the child found difficult to meet. Miguel Sánchez del Castillo (a film actor working in Rome at the time) recalls that, on one occasion, Juan Carlos was given a cavalry uniform as a present from several Spanish aristocratic ladies. ‘An Italian photographer spent over an hour taking pictures of him. Don Juan Carlos, who was only four years old at the time, endured having to stand to attention on a table. When they finally took him to the kitchen and one of his nannies took his boots off, his feet had been rubbed raw, because the boots were too small for him. That is when he shyly started to cry. I later learnt that his father had taught him from a very young age that a Borbón cries only in his bed.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Two events soon disturbed the royal family’s tranquillity: the first was Queen Victoria Eugenia’s departure from Rome; the second was Alfonso XIII’s death. Victoria Eugenia had been spending increasing amounts of time in Rome. When Italy entered the Second World War on 9 June 1940, her position as an English woman became difficult and thereafter she divided her time between Lausanne in neutral Switzerland and the outskirts of Rome. She and her husband had been effectively separated for more than a decade but, as his health deteriorated, they spent more time together. In 1941, she returned to Rome in order to care for him, moving into the nearby Hotel Excelsior, where she stayed until his death.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Alfonso XIII died on 28 February 1941. A few weeks earlier, on 15 January, he had abdicated in favour of his son and heir, Don Juan. Speaking with the American journalist, John T. Whitaker, shortly before his end, the exiled King said, ‘I picked Franco out when he was a nobody. He has double-crossed and deceived me at every turn.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Alfonso was right. During his final agony, he kept asking whether Franco had enquired about his health. Pained by his desperate insistence, his family lied and told him that the Generalísimo had indeed sent a telegram asking for news. In reality, Franco showed not the slightest concern. At Alfonso XIII’s bedside, Don Juan made a solemn promise to his father to ensure that he was buried in the Pantheon of Kings at El Escorial. His promise could not be fulfilled while Franco remained alive, and Alfonso XIII’s body would remain in Rome until its transfer to El Escorial in early 1981. Franco was reluctant even to announce a period of national mourning for the King. He grudgingly agreed to do so only when faced with the sudden appearance of black hangings draped from balconies in the streets of Madrid. He limited himself to sending a red and gold wreath. Amongst the many other floral tributes that adorned Alfonso XIII’s funeral on 3 March 1941 was one from Juan Carlos. It was a simple arrangement of white, yellow and red flowers tied together with a black ribbon on which someone had sewn with a yellow thread the dedication ‘para el abuelito’ (for granddad).

(#litres_trial_promo)

The death of Alfonso XIII seemed, in all kinds of ways, to free Franco to give rein his own monarchical pretensions. He insisted on the right to name bishops, on the royal march being played every time his wife arrived at any official ceremony and planned, until dissuaded by his brother-in-law, to establish his residence in the massive royal palace, the Palacio de Oriente in Madrid. By the Law of the Headship of State published on 8 August 1939, Franco had assumed ‘the supreme power to issue laws of a general nature’, and to issue specific decrees and laws without discussing them first with the cabinet ‘when reasons of urgency so advise’. According to the sycophants of his controlled press, the ‘supreme chief was simply assuming the powers necessary to allow him to fulfil his historic destiny of national reconstruction. It was power of a kind previously enjoyed only by the kings of medieval Spain.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The 27-year-old Don Juan – now, in the eyes of many Spanish monarchists, King Juan III – took the title of Conde de Barcelona, the prerogative of the King of Spain. He faced a lifelong power struggle with Franco, who held virtually all the cards. For the task of hastening a monarchical restoration, he could rely only on the support of a few senior Army officers. However, the Falange was fiercely opposed to the return of the monarchy and Franco himself had no intention of relinquishing absolute power. In the aftermath of the Civil War, many conservatives who might have been expected to support Don Juan were reluctant to face the risks involved in getting rid of Franco. Accordingly, Don Juan began to seek foreign support. With an English mother and service in the Royal Navy, his every inclination was to look to Britain. But he was resident in Fascist Italy and the Third Reich was striding effortlessly from triumph to triumph. Accordingly, his close adviser, the portly and foul-mouthed Pedro Sainz Rodríguez, pressed him to seek the support of Berlin or at least secure its benevolent neutrality towards a monarchical restoration in Spain.

(#litres_trial_promo) On 16 April 1941, Ribbentrop instructed the German Ambassador in Spain, Eberhard von Stohrer, to inform Franco – lest he hear of it through other channels – that Don Juan de Borbón had tried to contact the Germans through an intermediary in order to get their support for a monarchist restoration. The intermediary had approached a German journalist, Dr Karl Megerle, on 7 April and again on 11 April 1941. In the early summer of 1941, the Italian Ambassador in Spain, Francesco Lequio, recounted rumours circulating in Madrid that Don Juan was about to be invited to Berlin to discuss a restoration. Lequio reported that the intensification of efforts to accelerate the restoration were emanating from Don Juan’s mother – ‘an intriguer, eaten up with ambition’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

In response to the approaches made to the Germans by Don Juan’s supporters, Franco wrote an impenetrably convoluted letter to him at the end of September 1941. The tone was deeply patronizing: ‘I deeply regret that distance denies me the satisfaction of being able to enlighten you as to the real situation of our fatherland.’ The gist was a tendentious summary of Spain’s recent history which permitted Franco to combine the apparently conciliatory gesture of recognizing Don Juan’s claim to the throne with the threat that he would play no part in the future of the regime if he did not refrain from pushing that claim. What was quite clear was Franco’s total identification with the cause of the Third Reich – unmistakably referring to Britain and Russia when he spoke of ‘those who were our enemies during the Civil War … the nations who yesterday gambled against us and today fight against Europe’. Warning Don Juan against any action that might diminish Spanish unity (that is to say, threaten the stability of Franco’s position), he underlined the need ‘to uproot the causes that produced the progressive destabilization of Spain’ – a sly reference to the mistakes of the reign of Alfonso XIII. This task could be fulfilled only by his single party, the great amalgam known as the Movimiento, which was dominated by Falangists. Don Juan was warned that only by refraining from rocking Franco’s boat might he, ‘one day’, be called to crown Franco’s work with the installation – not restoration – of Spain’s traditional form of government.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Don Juan waited three weeks before replying. The delay may have been caused by the fact that, on 3 October 1941, his second son had been born. Christened Alfonso after his recently deceased grandfather, he would soon be the apple of his father’s eye. When he did write to the Caudillo, Don Juan seized on the recognition of his claim to the throne and suggested that Franco convert his regime into a regency as a stepping stone to the restoration of the monarchy.

(#litres_trial_promo) Subsequently, knowing that Franco was in no hurry to bring back the monarchy, and as part of their ongoing power struggle with the Falange, a group of senior Spanish generals sent a message to Field-Marshal Göring in the first weeks of 1942. They requested his help in placing Don Juan upon the throne in Madrid in exchange for an undertaking that Spain would maintain its pro-Axis policy. Pressure on Franco was stepped up in the early spring, when, at the invitation of the Italian Foreign Minister, Count Galeazzo Ciano, Don Juan attended a hunting party in Albania where he was received with sumptuous hospitality and full honours by the Italian authorities. In May, it was rumoured in Madrid that Göring himself had met with Don Juan in Lausanne (where he and his family were now resident) to express his support for his ambitions. Johannes Bernhardt, Göring’s unofficial representative in Spain, arranged at the end of May for General Juan Vigón to be invited to Berlin to discuss the matter. Vigón was both Minister of Aviation and one of Don Juan’s representatives in Spain. At the same time, Franco’s Foreign Minister, Ramón Serrano Suñer, had come to favour a monarchical restoration in the person of Don Juan. In June 1942, Serrano Suñer told Ciano in Rome that he believed that the Axis powers should come out in favour of Don Juan in order to neutralize British support for him. Serrano Suñer was planning to visit Don Juan in Lausanne. A somewhat alarmed Franco prohibited the trips of Vigón and of Serrano Suñer.

(#litres_trial_promo)

In fact, the brief flirtation between some monarchists and the Axis soon came to an end. It was clear that the fate of the monarchy would be better served by alignment with the British. Soon after her husband’s death, Victoria Eugenia had returned to her home in Lausanne, La Vieille Fontaine. In the summer of 1942, Don Juan moved his family there too and, shortly afterwards, appointed the four-year-old Juan Carlos’s first tutor. His strange choice was the gaunt and austere Eugenio Vegas Latapié, an ultra-conservative intellectual. In 1931, appalled by the establishment of the Second Republic, Vegas Latapié, for whom democracy was tantamount to Bolshevism, had been the leading light of a group which set out to found a ‘school of modern counter-revolutionary thought’. This took the form of the extreme rightist group, Acción Española, whose journal provided the theoretical justification for violence against the Republic, while its well-appointed headquarters in Madrid served as a conspiratorial centre.

(#litres_trial_promo) Shortly after the creation of Acción Española, Eugenio Vegas Latapié had written to Don Juan and a friendship had been forged. Ironically, Vegas Latapié had helped elaborate the idea that the old constitutional monarchy was corrupt and had to be replaced by a new kind of dynamic military kingship, a notion used by Franco to justify his endless delays in restoring the Borbón monarchy. Now, as a faithful servant of Don Juan, his outrage at this was such that, despite having served in the Nationalist forces during the Civil War, he turned against Franco. In April 1942, Don Juan asked Vegas Latapié to join a secret committee with the task of preparing for the restoration of the monarchy. When Franco found out, he ordered both Vegas Latapié and Sainz Rodríguez exiled to the Canary Islands. Sainz Rodríguez took up residence in Portugal and Vegas Latapié fled to Switzerland where he became Don Juan’s political secretary.

Deeply reactionary and authoritarian, Vegas Latapié had a powerfully sharp intelligence but seemed hardly suitable to be mentor to a four-year-old child, particularly one who was far from intellectually precocious. Inevitably, Vegas Latapié’s nomination as the boy’s tutor did little for the rather introverted Juan Carlos. Neither his tutor nor his father took much notice of him, their attention being absorbed by the progress of the War and plans for the return of Don Juan to the throne. Initially, Vegas Latapié’s role was, at Don Juan’s request, to give Spanish classes to Juan Carlos because the boy spoke the language with some difficulty, having a French accent and using many Gallicisms. When Juan Carlos reached the age of five, he began to attend classes at the Rolle School, in Lausanne. Vegas Latapié would accompany him to school in the morning and pick him up in the afternoon, using the trip to give the boy his extremely partisan and reactionary view of Spain’s past.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The relationship between Don Juan and Franco was developing in such a way as to dictate the direction of the young Prince’s later childhood, his adolescence and his adulthood. Fearful that the approaches made to the Germans by Don Juan’s supporters might bear fruit, on 12 May 1942, Franco had written him another patronizing letter based on his bizarre interpretation of Spanish history. In it, he rejected the notion that there was support in Spain for a restoration and reiterated his rejection of everything associated with the constitutional monarchy that fell in 1931. Linking the greatness of imperial Spain with modern Fascism, he stated that the only monarchy that could be permitted was a totalitarian one such as he associated with Queen Isabella I of Castile. He made it clear that there would be no restoration in the near future, and none at all unless the Pretender were to express his commitment to the Spanish single party, FET y de las JONS (Falange Española Traditionalist a y de las juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista), created in 1937 by the forced unification of all right-wing parties.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Don Juan did not reply to Franco’s letter of May 1942 for ten months. The outbreak of violent clashes between monarchists and Falangists – and the consequent removal of Ramón Serrano Suñer – in mid-August 1942 boosted his confidence. The Allied landings in North Africa on 8 November 1942 convinced him that the best chance of a restoration was to distance himself from Franco and persuade the Allies that, after the War, the monarchy could provide both stability and national reconciliation. On 11 November 1942, barely three days after the landings, Don Juan’s most powerful supporter, General Alfredo Kindelán, the most senior general on active service and Captain-General of Catalonia, travelled to Madrid. After discussing recent events with the rest of the high command, Kindelán informed the Caudillo in unequivocal terms that if he had committed Spain formally to the Axis then he would have to be replaced as Head of State. In any case, he advised Franco to proclaim Spain a monarchy and declare himself regent. Franco swallowed his fury and responded in a conciliatory – and deceitful – way. He denied any formal commitment to the Axis, implied that he was anxious to relinquish power and confided that he wanted Don Juan to be his ultimate successor. Franco was seething. After a cautious interval of three months, he replaced Kindelán as Captain-General of Catalonia.

(#litres_trial_promo)

When Don Juan did finally reply to Franco’s letter, in March 1943, his tone was altogether more confrontational than before. He questioned Franco’s exercise of absolute power without institutional or juridical basis and expressed alarm at both the continued divisions within Spain and the international situation. He firmly informed Franco that it was his patriotic duty to: ‘abandon the current transitory and one-man regime in order to establish once and for all the system which, according to Your Excellency’s oft-repeated phrase, forged the greatness of our fatherland’. He bluntly stated that he found entirely unacceptable Franco’s vague formula of delaying the return of the monarchy until his work was done. Then, in terms that can only have horrified Franco, Don Juan roundly rejected the Caudillo’s call for him to identify with the Falange, asserting that any link with a specific ideology ‘would mean the outright denial of the very essence of the value of monarchy which is radically opposed to the provocation of partisan divisions and domination by political cliques and is rather the highest expression of the interests of the entire nation and the supreme arbiter of the antagonistic tensions inevitable in any society’.

In his letter, Don Juan outlined the formula for the eventual restoration of a democratic monarchy in Spain on the basis of national reconciliation – although he cannot have imagined that it would take a further 32 years. Recalling Alfonso XIII’s declaration in 1931 that he was ‘Rey de todos los españoles’ (King of all Spaniards), Don Juan presented Franco with a slap in the face for which he would never be forgiven: ‘In fact, my arrival on the throne after a cruel civil war should, in contrast, appear to all Spaniards – and this is precisely the transcendental service that the monarchy, and only the monarchy, can offer them – not as an opportunist government of a particular historical moment or of exclusive and changing ideologies, but rather as the sublime symbol of a permanent national reality and the guarantee of the reconstruction, on the basis of harmony, of Spain, complete and eternal.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Franco’s outrage can be discerned both in the unaccustomed (for him) rapidity (19 days) in which he replied and in the unconcealed contempt of his tone. ‘Others might speak to you in the submissive tone imposed by their dynastic fervour or their ambitions as courtiers; but I, when I write to you, can do so only as the Head of State of the Spanish nation addressing the Pretender to the throne.’ He went on, condescendingly, to attribute Don Juan’s position to his ignorance and to lay before him a petulant list of what he regarded as his own achievements.

(#litres_trial_promo)

In the wake of Allied success in expelling Axis forces from North Africa in June 1943, Don Juan remained on the offensive. He could draw confidence from the fact that monarchists within the regime were beginning to fear for their own futures. At the end of the month, a group of 27 senior Procuradores (parliamentary deputies) from Franco’s pseudo-parliament, the Cortes, appealed to the Caudillo to settle the constitutional question by re-establishing the traditional Spanish Catholic monarchy before the War ended in an inevitable Allied victory. They believed that only the monarchy could avoid Allied retribution for Franco’s pro-Axis stance throughout the War. The signatories came from right across the Francoist spectrum, with representatives from the banks, the Armed Forces, monarchists and even Falangists. The Caudillo reacted swiftly. Even before the manifesto was published, he had ordered the arrest of the Marqués de la Eliseda who was collecting the signatures. As soon as it was published, showing how very little he was interested in his much-vaunted contraste de pareceres (contrast of opinions – his substitute for democratic politics), he dismissed all the signatories from their seats in the Cortes immediately and sacked the five of them who were also members of the Movimiento’s supreme consultative body, the Consejo Nacional.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The Caudillo’s sense of being under siege by Don Juan was intensified by the fall of Mussolini on 25 July 1943. Don Juan sent Franco a telegram recommending the restoration of the monarchy as his only chance to avoid the fate of the Duce. It embittered even further the tension between the two. Thereafter, Don Juan believed that Franco never forgave him: ‘he always had it in for me after that telegram.’ It was a bizarre measure of Franco’s self-regard that he regarded Don Juan’s action as high treason.

(#litres_trial_promo) Mortified, but aware of his own vulnerability, he shelved his resentment for a better moment. Instead, Franco replied with an appeal to Don Juan’s patriotism, begging him not to make any public statement that might weaken the regime.

(#litres_trial_promo) The Caudillo had every reason to be worried – his senior generals were swinging more openly behind the cause of Don Juan. Pedro Sainz Rodríguez was informed that a number of them were ready to rise to restore the monarchy, provided that immediate Allied recognition could be arranged by Don Juan. The Caudillo’s anxiety – and his resentment of Don Juan – was exacerbated when he discovered in the late summer that the generals were conspiring. Prompted by Don Juan’s senior representative in Spain, his cousin Prince Alfonso de Orleans Borbón, they met in Seville on 8 September 1943 to discuss the situation and composed a document calling upon Franco to take action to bring back the monarchy.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Signed by eight Lieutenant-Generals, Kindelán, Varela, Orgaz, Ponte, Dávila, Solchaga, Saliquet and Monasterio, the letter was handed to the Caudillo by General Varela at El Pardo (Franco’s official residence just outside of Madrid) on 15 September. In fact, the Caudillo had already been alerted to its contents by a member of Don Juan’s Privy Council, Rafael Calvo Serer. Calvo Serer was a talented, if somewhat erratic, young intellectual, and a convinced monarchist, but he was also a high-ranking member of the Opus Dei. He had insinuated himself into the inner circle of Alfonso de Orleáns Borbón and when he got hold of the draft, hastened to Franco’s summer residence, the Pazo de Meirás in Galicia. In fact, respectfully couched – ‘written in terms of vile adulation’ according to one of Don Juan’s principal advisers, the exiled José María Gil Robles – the letter was more annoying than threatening to Franco. However, it did nothing to improve his attitude to Don Juan.

(#litres_trial_promo)

At the end of 1943, Don Juan wrote a letter to one of his most prominent followers, the Conde de Fontanar. The inflammatory text referred to Franco as an ‘illegitimate usurper’ and called upon Fontanar to break publicly with the regime. The letter fell into Franco’s hands. Don Juan had chosen as his intermediary the sleekly ambitious Rafael Calvo Serer. Later Don Juan came to believe erroneously that the letter had been given by Calvo Serer to his spiritual adviser, Padre Josemaría Escrivá de Balaguer, the Aragonese priest and founder of the Opus Dei, who had then handed it to Franco. It has also been alleged that the letter was actually given by Calvo Serer to Franco’s cabinet secretary and a key adviser, Captain Luis Carrero Blanco, with the request that its ‘interception’ be attributed to the dictatorship’s intelligence services. However, the allegation remains unproved.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The Caudillo responded to Don Juan with disdain. After a feeble lie about the letter falling into the hands of an enemy agent ‘from whom we were able to retrieve it’, he went on to patronize the Conde de Barcelona in imperious terms. He asserted that his own right to rule Spain was infinitely superior to that of Juan III: ‘among the rights that underlie sovereign authority are the rights of occupation and conquest, not to mention that which is engendered by saving an entire society.’ To devalue Don Juan’s claims, Franco stated that the military uprising of 1936 was not specifically monarchist, but more generally ‘Spanish and Catholic’ and that his regime therefore had no obligation to restore the monarchy. This sat ill with his own published justification for preventing Don Juan serving on the Nationalist side in 1937. In further defence of his legitimacy, he cited his own merits, accumulated during a life of sacrifice, his prestige among all sectors of society and public acceptance of his authority. He went on to state that Don Juan’s actions constituted the real illegitimacy because they were impeding the monarchical restoration to which the Caudillo ostensibly aspired. Franco ended by recommending that Don Juan leave him, without any time limit, to his self-appointed task of preparing the ground for an eventual restoration.

Don Juan’s reply was not without its ironic undertones. In response to Franco’s insinuation that he was out of touch with the situation in Spain, he pointed out that in 13 years of exile, he had learned more than he might living in a palace, where, he said in a pointed reference to life at El Pardo, the atmosphere of adulation so often clouded the vision of the powerful. Regarding their conflicting visions of the international situation, Don Juan pointed out that Franco was one of the very few people in 1943 to believe in the long-term stability of the National-Syndicalist State. He suggested that Franco and his regime would not survive the end of the War. To avoid a stark choice between Francoist totalitarianism and a return to the Republic, Don Juan appealed to the Caudillo’s patriotism to restore the monarchy. Once more, he repeated his argument – an anathema to Franco – that the monarchy was a regime for all Spaniards and how, for that reason, he had always refused Franco’s invitations to express solidarity with the Falange.

(#litres_trial_promo) Don Juan’s crystalline letter had all the logic, common sense and patriotism that was lacking in Franco’s convoluted effort. However, the Caudillo was the sitting tenant and he was determined to brazen out the situation, confident that the Allies had too many other things to worry about. His optimism was in part fed by the conviction that the Americans regarded him as a better bet for anti-Communist stability in Spain than either the Republican opposition or Don Juan.

Despite his virtually limitless confidence in his own superiority over the House of Borbón, and his belief in the legitimacy of his power by dint of the right of conquest, Franco did feel seriously threatened by Don Juan’s so-called Manifesto of Lausanne. This momentous document was issued just as the Caudillo’s faith in Axis victory was finally beginning to ebb. With Pedro Sainz Rodríguez and José María Gil Robles in Portugal, and communication with Switzerland extremely difficult, the Manifesto was drawn up largely by Don Juan himself with the assistance of Eugenio Vegas Latapié. It was a denunciation of the Fascist origins and the totalitarian nature of the regime. Broadcast by the BBC on 19 March 1945, it called upon Franco to withdraw and make way for a moderate, democratic, constitutional monarchy. It infuriated Franco and set in stone his prior determination that Don Juan would never be King of Spain. Only the tiniest handful of monarchists responded to the Manifesto’s call for them to resign their posts in the regime.

(#litres_trial_promo) For many monarchists, Francoist stability had come to be worth much more than the uncertainties of a restoration. Fearful that Don Juan’s confidence in Allied support threatened the overthrow of the dictatorship and the possible return of the exiled left, they were not inclined to rally actively to his cause.

Franco’s éminence grise, the naval captain Luis Carrero Blanco, short, stocky, his face overshadowed by his thick bushy eyebrows, advised him how best to exploit this sentiment. The dourly loyal Carrero Blanco recommended that he refrain from lashing out immediately against Don Juan. Instead, he counselled a process whereby the Pretender would be weaned away from his more radical advisers and coaxed into the Movimiento fold. His memorandum to Franco was astonishingly prophetic and it did not bode well for Don Juan’s future or for Juan Carlos’s happiness: ‘It is crucial to get Don Juan on the road to radical change so that, in some years, he might be able to reign, otherwise he must resign himself to his son coming to the throne. Moreover, it is necessary to start thinking about preparing the child-prince for Kingship. He is now six or seven and seems to have good health and physical constitution; if properly brought up, principally in terms of Christian morality and patriotic sentiments, he could be a good King with the help of God, but only if this problem is faced up to now. For the moment, it would be prudent, 1) given that new clashes are not in our interests and nothing good can come of them, not to react violently against Don Juan nor give up on him altogether even though we believe that he cannot now be King; 2) to send some trustworthy monarchists to Lausanne; 3 ) to put the greatest care into selecting a perfectly prepared tutor for the young Prince; 4) to face up determinedly to the problem of the fundamental laws that we need, and define the Spanish regime. With regard to choosing our definitive form of government, since nations can be only republics or monarchies, and in Spain the republic is out of the question since it is a symbol of disaster, the form of government has to be a monarchy.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Without the military support of the Allies or the prior agreement of the military high command and the ecclesiastical hierarchy, Don Juan was naïvely depending on Franco withdrawing in a spirit of decency and good sense. The Caudillo’s determination never to do so was revealed in his comment to General Alfredo Kindelán: ‘As long as I live, I will never be a queen mother.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Despite Carrero’s counsel of moderation, Franco was deeply stung by the Lausanne Manifesto. He began to take practical steps to give substance to his claims to be the best hope for the monarchy. Two prominent regime Catholics, Alberto Martín Artajo, President of Catholic Action, and Joaquín Ruiz Giménez were despatched to tell Don Juan that the Church, the Army and the bulk of the monarchist camp remained loyal to Franco. They had no need to tell him that the Falange was deeply opposed to a restoration.

(#litres_trial_promo) To neutralize any resurgence of monarchist sentiment in the high command, Franco summoned his senior generals to a meeting which remained in session for three days, from 20 to 22 March. He brazenly informed his generals that Spain was so orderly and contented that other countries including the United States were jealous and planned to adopt his Falangist system. He tried to frighten his generals off any monarchist conspiracy by brandishing the danger of Communism for which he blamed Britain, Don Juan’s best chance of international support. It did not bode well for the Borbón family that, Kindelán aside, the generals seemed happy to swallow the Caudillo’s absurd claims.

(#litres_trial_promo)The controlled press praised Franco for having saved the Spanish people from ‘martyrdom and persecution’, the fate, it was implied, to which the failures of the monarchy had exposed them.

(#litres_trial_promo) Even more space than usual was devoted to the annual Civil War victory parade. Slavish tribute was paid to Franco’s victory over the ‘thieves’, ‘assassins’ and Communists of the Second Republic – the barely veiled message being that these same criminals – and with them, Don Juan – were even now plotting their return with the help of the Allies.

(#litres_trial_promo)

All this time, the young Juan Carlos had been brought up by nannies and tutors, seeing more of his mother than his father, who was absorbed by the struggle to restore the throne. Now he was seven and oblivious, as were his parents, to the momentous implications of Carrero Blanco’s report on the Lausanne Manifesto. Thirty years before the death of Franco, Carrero Blanco was proposing that his master’s eventual successor be Juan Carlos. For that to be a feasible option, it would be crucial, from the dictator’s point of view, that Juan Carlos received the ‘right’ kind of political formation, or indoctrination. Don Juan’s acquiescence was crucial, yet Franco made little effort to avoid unduly antagonizing him. When the chubby Martín Artajo returned from his mission to Lausanne, Franco grilled him on 1 May for two and a half hours about his conversations with Don Juan. Still furious about the Manifesto, Franco snapped, ‘Don Juan is just a Pretender. I’m the one who makes the decision.’ The Caudillo made it patently clear that he did not believe in one of the basic tenets of monarchism – the continuity of the dynastic line. In coarse language that must have shocked the prim Martín Artajo, he dismissed what he considered to be the decadent constitutional monarchy by reference to the notorious immorality of the nineteenth-century Queen Isabel II. He said, ‘the last man to sleep with Doña Isabel cannot be the father of the King and what comes out of the belly of the Queen must be examined to see if it is suitable.’ Clearly, Franco did not regard Don Juan de Borbón as fit to be King. He made critical comments about his personal life and dismissed Martín Artajo’s efforts to defend him – ‘There’s nothing to be done … He has neither will nor character.’ Franco would produce a law which turned Spain into a kingdom but that would not necessarily mean bringing back the Borbón family. A monarchical restoration would take place, declared Franco, ‘only when the Caudillo decided and the Pretender had sworn an oath to uphold the fundamental laws of the regime’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Nevertheless, the imminent final defeat of the Third Reich, together with Don Juan’s pressure, impelled Franco to make a crudely cynical gesture aimed at undermining the Pretender’s position among monarchists inside Spain. Over several days in the first half of April 1945, he discussed the idea of adopting a ‘monarchical form of government’. Monarchists within the Francoist camp were thus offered a sop to their consciences, together with an assurance that they need not face the risks of an immediate change of regime. At the same time, the cosmetic change would help the Allies forget that Franco’s regime had been created with lavish Axis help. A new Consejo del Reino (Council of the King) would be created to determine the succession. Grandiosely billed as the supreme consultative body of the regime, its function was simply to advise Franco, who would have no obligation to heed its advice. Moreover, the emptiness of the gesture was exposed by the announcement that Franco would remain Head of State and that the King designated by the Consejo would not assume the throne until Franco either died or abandoned power himself. A pseudo-constitution known as the Fuero de los Españoles (Spaniards’ Charter of Rights) was also announced.

Given his messianic conviction in his own God-given right to rule over Spain, Franco could never forgive Don Juan for trying to use the international situation to hasten a Borbón restoration. He believed that, if he could buy time from his foreign enemies and his monarchist rivals with cosmetic changes to his regime, the end of the War would expose, to his benefit, the underlying conflict between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union. His confidence was well-founded. On 19 June, at the first conference of the United Nations, which had been in session in San Francisco since 25 April, the Mexican delegation proposed the exclusion of any country whose regime had been installed with the help of the Armed Forces of the States that had fought against the United Nations. The Mexican resolution, drafted with the help of exiled Spanish Republicans, could apply only to Franco’s Spain and it was approved by acclamation.

(#litres_trial_promo) Within the Spanish political class, it was assumed that there would now be negotiations for the restoration of the monarchy.

(#litres_trial_promo) However, aware that, in Washington and London, there were those fearful that a hard line might encourage Communism in Spain, Franco and his spokesmen simply refused to accept that the San Francisco resolution had any relevance to Spain, making the most bare-faced denials that his regime was created with Axis help.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Shortly afterwards, Franco would adopt a strategy aimed at reversing Don Juan’s advantage in the international arena. The Fuero de los Españoles was introduced with a speech that implied to Spaniards and Western diplomats alike that any attempt to remove or modify the regime would open the gates to Communism.

(#litres_trial_promo) Within one month, he reshuffled his cabinet in order to eliminate the ministers most tainted by the Axis stigma and brought in a number of deeply conservative Christian Democrats. They, and particularly the most prominent of them – Alberto Martín Artajo as Foreign Minister – permitted Franco to project a new image as an authoritarian Catholic ruler rather than as a lackey of the Axis.

(#litres_trial_promo)

A fervent Catholic, Martín Artajo owed his appointment to the recommendation of Captain Carrero Blanco, with whom he had spent nearly six months between October 1936 and March 1937 in hiding in the Mexican Embassy in Madrid. He accepted the post after consultation with the Primate, Cardinal Plá y Deniel, and both were naïvely convinced that he could play a role in smoothing the transition from Franco to the monarchy of Don Juan.

(#litres_trial_promo) Franco was happy to let them believe so, but intended to maintain an iron control over foreign policy. The subservient Artajo would simply be used as the acceptable face of the regime for international consumption. Artajo told the influential right-wing poet and essayist, José María Pemán, a member of Don Juan’s Privy Council, that he spoke on the telephone for at least one hour every day with Franco and used special earphones to leave his hands free to take notes. Pemán cruelly wrote in his diary: ‘Franco makes international policy and Artajo is the minister-stenographer.’ In the first meeting of the new cabinet team, on 21 July, Franco told his ministers that concessions would be made to the outside world only on non-essential matters and when it suited the regime.

(#litres_trial_promo)

While nonplussed by the clear evidence that Franco had no immediate intentions of restoring the monarchy, Don Juan was encouraged by the appointment of Martín Artajo, whom he trustingly regarded as one of his supporters. It was the beginning of a process in which Don Juan was to be cunningly neutralized by Franco. As part of a plan to drive a wedge between Don Juan and his more outspoken advisers, Gil Robles, Sainz Rodríguez and Vegas Latapié, Franco encouraged conservative monarchists of proven loyalty to his regime to get close to the royal camp. One of the most opportunistic of these was the sleekly handsome José María de Areilza, a Basque monarchist who had been closely linked to the Falange in the 1930s. Areilza had acquired the aristocratic title of Conde de Motrico through marriage and his impeccable Francoist credentials had been rewarded when he was named Mayor of Bilbao after its capture in June 1937. In 1941, he wrote with Fernando María Castiella, the ferociously imperialist text Reivindicaciones de España (Spain’s Claims) and had aspired to be Ambassador to Fascist Italy. After the War, he moved back to the pro-Francoist monarchist camp, and would be named Ambassador to Buenos Aires in May 1947. His visits to see Don Juan were dutifully reported to the British Embassy to give the impression that Franco was negotiating the terms of a restoration and so buy him more time.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The wisdom of Franco’s policy, and the waning prospects of Don Juan, were both illustrated by the relatively toothless Potsdam declaration which reiterated Spain’s exclusion from the United Nations but made no suggestion of intervention against the Caudillo. Statements from the British Labour government that nothing would be done that might encourage civil war in Spain heartened the Caudillo further.

(#litres_trial_promo) Don Juan would have been even gloomier had he known of a report on the regime’s survival drafted at this time by Franco’s ever more influential assistant, Captain Carrero Blanco. It was a brutally realistic document which rested on the confidence that, after Potsdam, Britain and France would never risk opening the door to Communism in Spain by supporting the exiled Republicans. Accordingly, ‘the only formula possible for us is order, unity and hang on for dear life. Good police action to anticipate subversion; energetic repression if it materializes, without fear of foreign criticism, since it is better to punish harshly once and for all than leave the evil uncorrected.’ There was no place for Don Juan in that future.

(#litres_trial_promo) On 25 August 1945, Franco sacked Kindelán as Director of the Escuela Superior del Ejército (Higher Army College) for making a fervently royalist speech predicting that the Pretender would soon be on the throne with the full support of the Army.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Anxious to establish control over Don Juan, in the autumn of 1945, Franco through intermediaries suggested that if the heir to the throne took up residence in Spain, he would be provided with a royal household fit for a future King. The message, passed on by Miguel Mateu Pia, the Spanish Ambassador in Paris, made it clear that Franco had no intention of any sudden change. He was merely looking for a way of placating both the Great Powers and the monarchist conspirators in the Army. Don Juan had no desire to become the Caudillo’s puppet and was still hopeful of military action to overthrow the regime. Accordingly, he rejected the offer out of hand – commenting ‘I am the King. I do not enter Spain by the back door.’ The refusal was underlined when Don Juan told La Gazette of Lausanne that the need to ‘repair the damage done to Spain by Franco’ made the restoration of the monarchy an urgent necessity. He denounced Franco’s regime as ‘inspired by the totalitarian powers of the Axis’ and spoke of his intention to re-establish the monarchy within a democratic system similar to those of Britain, the United States, Scandinavia and Holland.

(#litres_trial_promo)

On 2 February 1946, Don Juan and his wife moved to the fashionable but sleepy seaside resort of Estoril, west of Lisbon. An area of splendid mansions built for the millionaire bankers and shipbuilders of the nearby capital, its silent isolation was disturbed only by the click of chips falling in the casinos. The eight-year-old Juan Carlos, to his considerable distress, was left behind in Switzerland, where he was by now being educated by the Marian fathers in Fribourg. For the first two months in Portugal, his family lived in Villa Papoila, loaned by the Marqués de Pelayo, later moving in March 1946 to the larger Villa Bel Ver. They stayed there until the autumn of 1947 when they moved to Casa da Rocha, until finally in February 1949, they established their residence at Villa Giralda. In 1946, for many of Don Juan’s supporters, his proximity to Spain seemed to shorten the distance that separated him from the throne. His mere presence in the Iberian Peninsula set off a wave of monarchist enthusiasm. The Spanish Foreign Ministry was inundated with requests for visas as senior monarchists set off to pay their respects.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Franco’s Ambassador to Portugal, his brother Nicolás, quickly established a superficially cordial relationship with Don Juan. However, when Nicolás suggested he drive him to Madrid for a secret meeting with the Caudillo, Gil Robles, Don Juan’s senior adviser, was adamant: ‘Your Majesty cannot go and see Generalísimo Franco on Spanish soil since he would be going there as a subject.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Indeed, it had been the expectation of tension with Franco that had led Don Juan to decide that it was better for Juan Carlos to remain in Switzerland. The wisdom of his decision was underlined when the Caudillo lashed out in response to the publication on 13 February 1946 of a letter welcoming Don Juan to the Peninsula, signed by 458 prominent establishment figures. Franco reacted as if he was faced with a mutiny by subordinates rather than an attempt to accelerate a process to which he had publicly committed himself. He told a cabinet meeting on 15 February, ‘This is a declaration of war, they must be crushed like worms.’ In an astonishing phrase, he declared, ‘the regime must defend itself and bite back deeply.’ He relented only after Martín Artajo, General Dávila and others had pointed out the damaging international repercussions of such a move. He then went through the list of signatories, specifying the best ways of punishing each of them, by the withdrawal of passports, tax inspections or dismissal from their posts.

(#litres_trial_promo)

While these high political dirty tricks were going on, the eight-year-old Prince was sent to a grim boarding school at Ville Saint-Jean in Fribourg, run by the stern Marian fathers. Juan Carlos would later recall his distress at being separated from his family and from his tutor Eugenio Vegas Latapié, of whom he had become fond. ‘At first, I was really very miserable, because I felt that my family had abandoned me, that my mother and father had just forgotten all about me.’ Every day he waited for a telephone call from his mother that never came. It must have been the harder to bear because of the gnawing suspicion that his parents’ favourite was his younger brother Alfonso, who remained at home with them. Only later did he discover that his father had forbidden his mother to phone him, saying, ‘María, you’ve got to help him become tougher.’ Later on, Juan Carlos tried to explain away his father’s actions – ‘It was not cruelty on his part and certainly not a lack of feeling. But my father knew, as I would later know myself, that princes need to be brought up the hard way.’ Juan Carlos had to pay a terrible price in loneliness – ‘in Fribourg, far from my father and my mother, I learned that solitude is a heavy burden to bear.’ The most visible consequences of the apparent harshness of his parents’ treatment would be his perpetually melancholy expression and a silent reserve.

In later endeavouring to explain away his father’s motivation, Juan Carlos inadvertently shed light on his own life as an eight-year-old, far from his parents: ‘My father had a deep sense of what being royal involved. He saw in me not only his son but also the heir to a dynasty, and as such, I had to start preparing myself to face up to my responsibilities.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Despite such rationalizations, it is clear that it was difficult for Juan Carlos ever to reconcile himself to this early separation. (His own son, Felipe, would not be sent to boarding school at such a young age and did not leave home for the first time until he was 16, in order to spend his last year at school at the Lockfield College School in Toronto, Canada.) Indeed, in a 1978 interview for the German conservative paper Welt am Sonntag, Juan Carlos would describe his departure for Ville Saint-Jean in more heartfelt terms: ‘going to boarding school meant saying goodbye to my childhood, to a worry-free world full of family warmth. I had to face that initial difficult period of separation from my family all alone.’

(#litres_trial_promo)