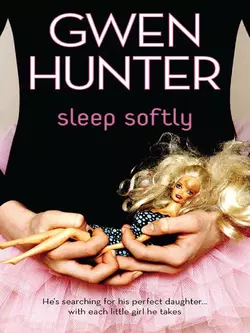

Sleep Softly

Gwen Hunter

Four little girls–each blond, each on the verge of adolescence–stolen from their families.Their bodies discovered months later in shallow graves, surrounded by trinkets they never owned, clutching a scrap of paper bearing a cryptic verse. As a forensic nurse in rural South Carolina, Ashlee Davenport Chadwick acts as both caregiver and cop, gathering evidence from anyone who arrives in the local E.R. as the result of a crime. It's a tough job, both physically and emotionally draining, but deeply satisfying.Then a child's red shoe is discovered on Davenport property. The evidence leads Ashlee to the body of a missing girl and her work suddenly invades every aspect of her life. As an expert and a witness, she must call upon all her resources. And when the killer's eye turns to her, she becomes intimately involved with a crime that tests her mind and her spirit…and the price of failure will be another child's life.

GWEN HUNTER

sleep softly

Contents

Acknowledgments

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

FOR HELP ON MUSES:

S. Joy Robinson, who did research and brought me wonderful books on the subject.

And Misty Massey, who gave me the idea in the first place.

FOR MEDICAL HELP:

I have tried to make the medical sections of Sleep Softly as realistic as possible. Where mistakes may exist, they are mine, not the able, competent and creative medical workers in the list below.

Susan Prater, O.R., Tech and sister-in-love, in South Carolina

Earl Jenkins, Jr., M.D., in South Carolina

James Maynard, M.D., in South Carolina

Eric Lavondas, M.D., in North Carolina

Randall Pruett, R.N., in South Carolina

As always, for making this a stronger book:

Miranda Stecyk, my editor, who had a massive editing job in this one! Kisses!

Jeff Gerecke, my agent.

Lynn Prater, esthetician and owner of Serenity Spa in Rock Hill, South Carolina, who gave me all the skin info (hope I got it right) and who keeps my skin glowing.

My husband, for answers to questions that pop up, for catching so much in the rewrites and for his endless patience.

My mother, Joyce Wright, for editing as I work.

To the love of my life who

Handles all the details

Is never boring, though is often hard to keep up with Writes wonderful songs

Didn’t laugh when I wanted to learn to whitewater kayak

Fixes the trucks and the RV and anything that breaks in the house.

Painted my dining room and didn’t balk at the dark garnet color

Learned to dance just for me

Rubs my feet when they hurt

Works 16 hours a day because he loves it

And who is a man of honor. There are so few in the world today.

Prologue

He spotted his landmark, a lightning-blasted tree, its bark peeled back to expose pale, dead wood, and turned left onto a little-used tertiary road. The pavement was pitted and cracked, and the old Volvo shuddered as the right front wheel slammed into a particularly deep pothole. The girl who hadn’t been his daughter shifted on the seat beside him, her head hitting the window with a thump and whipping toward him.

He caught her one-handed and eased her back to the seat. Her earrings tinkled softly beneath the music on the CD player. Violins harmonized the heartbreaking melody of a Mozart sonata.

Slowing, he pulled the black velvet throw over her again and patted her shoulder. She didn’t respond. He didn’t expect her to. She had been dead nearly an hour.

There were no streetlights here, the road disappearing into the darkness. A doe stood on the verge of dead grass, watching the car. She was unafraid, her jaw moving as she grazed on the coarse vegetation. “Did you see that deer?” he asked the girl. “You like deer.” She said nothing. He patted her shoulder again.

The old graveyard appeared just ahead, the damaged bronze horse beneath the Confederate soldier casting a bizarre shadow. The nose of the horse had broken off when vandals had thrown the statue to the ground in 1998. The cost of repairing the monument had been more than the local historical society had been able to acquire, and so the horse, while returned to its perch and secured to its base, remained a half-faced mount. He knew all this and much more; he’d done tedious, fatiguing research into the family tree and this graveyard. “Research is paramount, right, honey?”

The girl was still silent. When he braked in the graveyard, she slid down the seat, her body curling limply on the floor. “Sorry, sweetheart. But we’re here now.”

Leaving her in the car, the motor running, he took a flashlight and walked the perimeter of the graveyard from the monument clockwise, until he reached the horse again. The New York Philharmonic continued to play the Mozart piece as he paced an approximate ten feet to the family plot. Six generations of Shirleys were buried here, several with Confederate memorials on their headstones. Others were heroes of the First and Second World Wars. A husband and wife were buried side by side, though they had died two decades apart in the late 1800s. The husband, Caesar Olympus Shirley, the wife, Susan Chadwick Shirley. Five children had died and been buried within one week. Flu? Cholera? Strep? There had been no historical documentation.

The girl would like the Shirley children. He had seen an old daguerreotype of the family. They looked like nice people.

Back at the Volvo, he changed the CD to Vivaldi, opened the trunk and removed a shovel, a second flashlight and four small statues made of polished brass. They shone like gold in the light, each of them dressed in Grecian robes with arms lifted high, fingertips touching so their arms made a circle, as if they held the world. Each had devices at her hip, delicately molded brass instruments. He tucked a Bible under one arm and carried a small pink box by its plastic handle. A child’s lunch box he’d obtained on eBay. The girl had been delighted.

To the quickening pace of Vivaldi, he chose a place at the feet of the Shirley children, set down the funeral items, and shoved the shovel, blade first, into the ground. In the headlights, a long shadow created by the shovel was thrown across the graves, undulating as if seeking a place to secrete itself among the night-dark stones. Using his body weight, bruising his foot on the shovel, he dug the grave. Long minutes passed as the strains of the music soared and fell. The shovel acquired a rhythm that matched the music. A small blister rose on one palm. He worked up the sweat of a peasant, perspiration trickling down his sides in the un-seasonable warmth. He dug deep enough to keep out scavengers. Deep enough to keep her safe. She hadn’t been his daughter, but she had tried. She deserved a decent resting place and someone to mourn her passing.

When the grave was satisfactory, he threw the shovel to the side and went back to the car. Using the damp cloth he had brought in a Ziploc bag, he pulled off his shirt and washed himself. Then he removed a clean shirt from its hanger and forced his hands through the heavily starched arms, tied his tie and put on a suit coat. Funeral-black.

Properly attired, he pulled the velvet throw over her snugly. Lifting the precious bundle from the floor of the car, the black velvet tangled around her, he carried her to the narrow pit. He laid her gently on the grass and eased her down into the raw earth, the small grave illuminated by the headlights. Vivaldi played softly now, the strains drifting through the car windows into the night. A whip-poor-will sang in the distance.

One last time, he checked her pulse, two fingers on her wrist. Just to make sure. She wasn’t supposed to still be here, but there could always be unexpected problems. Nothing. Nothing at all. Leaning into the grave, he pressed his fingers against her cool throat and studied her in the earthen cavity. She was so beautiful. He had hoped she would be the one.

Using the utmost care, he bent over the grave and eased the velvet throw smoothly away from her, over her torso, down the hollows of her arms. Dragging it from her feet.

As he rose up, his body bent at an unnatural angle, his back wrenched, an excruciating tremor. Shock rippled through him. She had done this. This little girl. How could she hurt him? Angry, he held his breath against the pain, grunting when he tried to breathe, cursing her in his mind. Little piece of trash! Long minutes later, the spasm eased. He sat up, stretching his spine. The tremor worsened for an instant, then slid away.

He tested its return, bending and tensing. Satisfied, he bowed back over the grave and felt for a pulse a final time. Two minutes passed. There was nothing. No pulse. His anger of the moment before evaporated.

She was gone. A sob tore his throat. It wasn’t supposed to end like this. She was supposed to be the one.

Folding the velvet cloth, he tossed it to the side, opened the child’s lunch box and took out a blond ballerina doll. He placed the doll in the crook of the girl’s arm, smoothed the doll’s long hair with a tender hand, then tested once again the knot that decorated the doll’s waist over its pink ballerina outfit. Beside his daughter’s hip—No, not his daughter. The girl. What was her name? It didn’t matter. She had failed. Beside her hip he set her flute. She had forgotten how to play the flute in the last months of her life. Her loss of talent had saddened them both. But she was free now. On the other side of the grave, her gift was restored. And the girl would find his daughter, tell her that he was trying, that he loved her.

Vivaldi’s sonorous melody lifted on the night air, rising like a promise. She had loved Vivaldi. Or had that been the other one? For a moment, his confusion stirred and grew, but he pushed it away. All that mattered was that she hadn’t been his daughter. He had to remember that. It was all that mattered.

In the front of her leotard, the lavender and pink bleached gray in the moonlight, over her heart, he tucked the folded piece of heavy paper, paper they had made together so long ago. The poem this one had inspired would go with her to paradise, a gift she could pass along to his daughter when they met. He checked her tights, adjusted the pink tutu and retied one pointe shoe in the knot he preferred. Grief gathered as he tied the knot. It was always so hard.

He folded her hands, the flesh cold but still limber, maintaining the appearance of life. Her bound hands had slid out of place as he’d moved her to the earth. He pulled on both ends of the fine rope, tightening the complicated knot.

The engraved silver ring had slid backward. It was a bit too large for her slender finger and he straightened it. That was odd. The ring had fit when he’d bought it. He was sure of it.

A silver bracelet gleamed in the moonlight on the same wrist. He turned it just so. In her pierced ears were silver knots that jingled when she moved her head, the earrings hanging back onto her pale neck. Each piece of jewelry contained Celtic knots, not the kind he wanted, but he hadn’t been able to find the right style of knot. He was still searching. After this last failure, it was becoming imperative that he find the right earrings. He stroked the cool flesh of her neck, the skin so soft, so young and innocent. He wiped his face, found tears on his fingers.

“Sweetheart?” She didn’t answer. A second sob tore from him. He stooped over the small grave and wept softly. Why did she fail? She could have been the one.

When his grief abated, he opened the Bible to Psalm 88. It was a wise and insightful selection, one he had researched for hours. She would have liked the poetry of Psalms. He wished he could have read it in the original Hebrew, but he didn’t know the language. It looked like painted strokes. Perhaps he’d study that tongue. He brightened a moment. When his daughter came back to him, when her soul found its way back to her body, they could study it together.

Dropping to his knees in the damp earth so that one of the flashlights illuminated the page, he placed the brass statues around the small grave, one at the head, one at the foot and one to each side. He began to read. “O Lord, the God of my Salvation, I have cried to You for help by day; at night I am in Your presence….”

Warm night breezes caressed his skin. Vivaldi and the whip-poor-will called into the darkness as he spoke the holy words. The ceremony was exquisite. Grief fluttered in his chest like a dying bird. Tears gathered and trickled down his cheeks, causing the text to waver. By the tenth verse his voice was broken, his anguish so acute he feared his heart might burst and he might die before he finished the last rite. A heart attack would put an end to his pain. Perhaps he should welcome it. But death didn’t come.

The psalm finished, “Lover and friend have You put far from me; my familiar friends are darkness and the grave.” Putting the book aside, he bent over the grave and touched her face once more. She was as flawless as he could make her. She must remain so.

Tears still falling, using his hands so that no metal would bruise her, he scooped dirt over her feet. His knees pressing deeply into the damp earth, he was careful not to move too much soil with each scoop and disarrange her clothes or position. Scattering only a thin layer, he covered her legs, her thighs, her hips. Lastly he covered her face. She was gone from sight now. Regret scoured his soul. He wiped his face again with the damp rag. It showed traces of darkness in the dim light. He’d have to shower when he got home.

He set the statues aside where they were protected and wouldn’t accidentally fall in the grave, took the shovel, and finished filling the hole. Within a minute, sweat trickled down his back in the unexpectedly temperate air. It hadn’t been this warm when she’d left him. He’d have to remember that. Another variance he would have to work through. The last of his tears dried as he plied the shovel, the act of closing the grave bringing him back into control. It was always this way.

When the grave was full, he tramped on it, walking back and forth before walking a final time on the blade of the shovel to remove any shoe prints. With gentle hands, he smoothed the top of the grave. From the lunch box, he removed a rose bud. It was wilted, a bit bruised, but she had been pleased this morning when she’d woken to find it beside her face, on her pillow. She had smiled and sniffed the bud, had seemed for a moment less melancholy. Gently, he placed it atop the soil. Good memories.

Gathering all the tools he had brought with him, he tucked the statues, which he had purchased from a Grecian antiquities dealer, beneath an arm. He walked from the ancient family plot past the statue of the Confederate soldier mounted on his maimed horse, through the graveyard to the car. He drove into the night, the symphony leaving mournful notes on the air.

Back on the highway, he removed the Vivaldi CD and inserted a Beatles album. John Lennon singing about a flawless world.

It wasn’t too soon to start looking. Before long he would have it perfected. Perhaps he had worked out all the variables this time. Next time, the method of selection, enticement, abduction might be perfect. Then again, he might have to try, try again. He smiled at the whimsy but knew it contained an ultimate truth. There was no goal in life, in art, but perfection. The Greeks had understood that concept far better than any other people.

He sang into the night about an ideal world. He was prepared to spend an eternity to get it right. Eternity to bring his daughter back to him, perfected.

On the seat beside him was a Sunday edition of The State newspaper, open to the sports section. A girl’s face smiled at the photographer. She was beautiful. She was perfect.

1

Monday Morning

Parking behind the house, I crawled out of the battered SUV, slung my canvas bag of forensic nursing supplies over a shoulder and blinked into the early morning light. Jas ran from the house and jogged over to me. Bending, she kissed me once on the forehead. “Bye, little mama. I haven’t fed the dogs.”

“You never feed the dogs anymore,” I grumbled, feeling the age difference as she loped to her truck, looking lithe and nimble. And skinny in her size-five jeans. Waggling her fingers at me through the driver window, she gunned the motor of her new little GMC truck and spun out of the drive, heading to early class at the University of South Carolina. “And good morning to you, too. How was Sunday night at the hospital, Mama? It was lovely, Jasmine. Thank you for asking,” I said to the trail of dust in her wake.

Thinking I was talking to them, Big Dog, Cheeks and Cherry yapped at my hips, thighs and knees according to their height, demanding attention, which I absently gave while I yawned, a pat here, an ear-scratch there. Abandoned dogs needing a home made the best pets, and I took in as many dogs as I could, even adopting some from the county, when K-9 dogs became too old to work. The well-behaved animals romped and writhed in delight as I trudged to the house. They reeked of something they had rolled in, probably dead rabbit or squirrel, and wanted me to play a game of fetch but the shoe they brought was stinky.

“Bring me a stick. That thing is nasty.” I nudged it away with my white nurse’s shoe.

Big Dog, my half moose, half monster protector nudged it back, his floppy ears dangling, long tail wagging. Cheeks stopped my progress, a wriggling clot of hound-dog muscle in front of me. Cherry bounced up and down on her front feet, still yapping her high-pitched bark. “Hush. Okay. One toss,” I said, “then I bury this thing.”

I bent and lifted the shoe. A smell gusted out, sickly, almost sweet. I knew that scent. The scent of old death. The world seemed to slow as I held the small red sneaker. It was no longer than my hand, filthy, laces snarled with leaves and twigs. Reeking of the grave.

A child’s shoe.

Turning it over, I looked inside. Tissue. Something soft and rotten. A sycamore leaf twisted into the laces. A deep scuff along one rubber sole, some gummy substance ground into the uneven ridges. Decayed-meat smell. The early morning air shivered along my shoulders.

I returned to the SUV and opened the hatch, placing the shoe on the floor. This was dumb. This wasn’t…It couldn’t be. I was too tired and not thinking straight. I moved the photocopies of the family genealogy charts to the side so I wouldn’t dirty them or contaminate the evidence. If there was evidence.

I dumped out everything from the canvas tote I still carried and dropped the bag beside the spare tire attached to the sidewall. From the pile, I pulled a pair of blue non-latex gloves, tweezers, evidence bags, a tape measure and a sterile plastic sheet on which I set the shoe. I added a small handheld tape recorder and my new digital camera, part of the tools of the trade for a forensic nurse. I checked the time. Then I hesitated. I felt the chill air beneath my scrub shirt as I rested my hands on the rubberized ledge of the hatch. “This can’t be what I think it is.”

Big Dog huffed at my words and finally brought me a stick, sitting politely, with one paw raised. Though I called him part moose, he was part mongrel and part Great Pyrenees, and his head was higher than my waist. I tossed the stick once and the dogs ran, baying.

Should I call the cops? Stop right here and call the sheriff’s office? If I contaminated evidence after graduating with honors from the forensic nursing course, I’d feel like a failure as well as an idiot.

I blew out a breath of air. Okay. I knew how to preserve evidence.

I was too tired to think and my feet hurt and my lower back ached. All I wanted to do was drop the shoe and go to bed. The smell from the shoe permeated the SUV as I stood there, hesitant, staring at the red sneaker.

What if I called the cops and it was just a shoe from the illegal dump near the new development at the back of the farm? And the tissue was an old half-rotten hamburger that had gotten shoved inside, or a dead mouse? I’d feel even more like an idiot. I didn’t waste much effort on pride but I’d be embarrassed if I called law enforcement all the way out here to look at trash brought up by the dogs. The guys on the call would never let me live it down. I had worked as a volunteer for the Dawkins County Rescue Squad long enough to know I’d receive a new nickname and it wouldn’t be flattering.

It was probably nothing. A mouse. The remains of someone’s lunch. My chill subsided. I pulled on the gloves and dated, timed and initialed two evidence bags. I marked one bag FOLIAGE FROM LACES. Just in case. I snapped two shots with the digital camera and checked the viewer, making sure the sneaker would be visible, acceptable in a court of law. Not that I would need it. I was absolutely…I was almost sure.

Turning on the tape recorder, volume up high, I set it to the side, gave the time, date, my name, location and a short account of how I came into possession of the shoe. Extending the tape measure, I held it against the bottom of the shoe and took a photograph of the two together so the size could never be lost.

At the same time, I said the dimensions aloud for the recording and noted that it was a left shoe. Somehow that seemed important, though I was certain that was the mother in me reacting, not the forensic nurse.

With the tweezers, I pried apart the shoelaces, putting the leaves and twigs in the first paper bag. Using my fingers, I worked the snarled knot from the laces, gathering the material that fell out and adding it to the evidence bag, even small grains of dirt and grit and what looked like pale yellow sand. When the laces were unknotted, I pushed apart the stiff sides, exposing the tongue curled deep into the toe.

I snapped another photograph and labeled the second evidence bag CONTENTS: SHOE, TONGUE. Prying with the tweezers, I pulled on the cloth tongue, easing it out, gathering the scant granules and vegetable matter that escaped and put them into the second bag. The tongue twisted out, awkward and unyielding, wrapped around something, and I stepped back, letting the early morning sun touch the thing I had exposed.

Painted a bright, iridescent blue, the nail was separated from the surrounding tissue by decomposition. A lively shade, bright as the Mediterranean Sea. Blackened tissue. It was a child’s toe.

In the distance the dogs barked, a horse neighed, a door slammed. A crow called, the sound like mocking laughter, grating.

After a long moment, I found a breath, strident, harsh. The air ripping along my throat. My vision narrowed, darkening around the edges, focusing on the bright blue toenail. I leaned forward, catching my weight on the tailgate. I wanted to throw up. I sat down on the dirt at my feet, landing hard, jarring my spine.

The cool air now felt unexpectedly warm and I broke out in a hot sweat. My breath sped up, hyper-ventilating from shock. A mockingbird song I hadn’t heard until now sounded too loud, too coarse. In the distance, a horse tossed her head and snorted. Cherry, the small terrier, nudged my leg and romped around the SUV, yapping. I hadn’t been practicing forensic nursing a month yet, and here I had a toe in a shoe. Nothing I had studied told me what to do next.

Where had the dogs found the shoe?

There was no doubt. I had something important, something horrible, in my truck. A part of a little girl…I shuddered. A part of a little girl…

And I had tampered with evidence. “Well…” I said, wanting to say something stronger. I added another, softer, “Well,” not knowing any appropriate swear words that might cover this situation. What do you say when your dogs bring you part of a little girl? I fought rising nausea, swallowing down vile-tasting saliva. A shudder gripped me. Part of a little girl… I dropped my head and tried to slow my breathing.

When my vision cleared and the faintness passed, I stood again, pulling up on the tail of the truck, my knees popping as they had started to do in the last few months. Nausea rolled through me and faded. “Okay,” I said. “Okay. I can do this.” I wasn’t convinced, but I also knew it was far too late to stop.

With surprisingly steady hands, I rewound the tape in the recorder, found the place where I’d last spoken and took up my narrative. I turned to the shoe, describing what I had discovered. Forcing myself to breathe deeply and slowly, I took digital photos and checked to see that all the shots so far were in focus. That the shoe measurements were clear, that the toe was visible in the tongue of the shoe. I added the length and depth of the toe to my recording, doing the job I had learned in the forensics and evidence-collection class. I pulled a Chain of Custody form out of the pile of my forensic supplies and filled it out, comparing the times with the time on the photos.

Carefully, still narrating, I curled the tongue back into the shoe and placed the shoe into a third evidence bag I labeled SMALL RED SHOE/TOE. I gathered up the plastic sheet and placed it into another bag. I placed all the evidence bags into a large plastic bag labeled EVIDENCE in big red letters.

I pulled my gloves off, one at a time, gripping the wristband of the left, pulling it down and inside out, over my fingers. Holding the left glove in the right fist, I pulled that one down over my fingers and over the other glove, securing it inside the right, to keep the evidence I had touched in place. The scent in place. They went into a final evidence bag with a separate Chain of Custody form. I switched off the tape recorder and repacked my forensic supplies, setting the final bag on the top of the truck.

Closing the SUV hatch with the evidence inside, I took the bagged gloves and COC with me into the house, then washed my hands thoroughly at the kitchen sink, carrying the last bit of evidence with me as I moved.

With Jas already gone for the morning, the house was empty and quiet. Her bowl, smeared with yogurt and blueberry cereal, was in the sink, filled with water, next to her glass. I wasn’t interested in eating, though my daughter had left a box of Cheerios on the table with a clean bowl and spoon. My baby taking care of me, as she had since Jack had died, reminding me to eat.

The transition from child to caretaker had come early in Jas’s life, forced on her by her daddy’s death four years ago and my withdrawal into grief. I had spent the last two years letting her know I was fine now, but the habits learned in fear in the weeks after Jack’s funeral had proved impossible to break. I touched the bowl, almost smiling, took a deep breath and let it out slowly, letting my fingers fall away. I breathed again. Stress management. Sure. That would work. I took a third breath and forced it out hard.

There were a lot of things I had to do. The first one was to stop and think clearly. Not an easy task after a twelve-hour shift that had included two gunshot victims from a gang-related shoot-out, a three-car pileup and a near-drowning. But there wasn’t a hurry. No one was going to die if I paused and took the time to collect myself.

So I showered, slathered on sunscreen, dressed in jeans and tank top, then pulled one of my husband’s old flannel shirts over it, letting the tail hang out. Riding clothes. Things I could wear all day, if needed. I paused once to sniff the fabric. I had washed the few things of Jack’s I wanted before packing all the others off to friends and relatives. The shirt no longer smelled of him. I slipped on heavy socks and short-heeled western riding boots, found my hat, grabbed outdoor supplies and went back into the morning, feeling better now that I had decided what to do.

In the sunlight, still carrying the gloves, I made my way to the barn and checked on Johnny Ray to make sure he had done the chores. There were days when the stable hand was so far gone in the bottle that he never woke up, which had happened in a permanent way to his twin brother not so very long ago. Today Johnny Ray was sober, which could mean DTs tomorrow, but he was capable at the moment, and that was all that mattered. I had other constantly sober help, but Johnny had no place else to go. If I fired him, it would toss him down into total ruin faster. And when he was sober, he was an excellent stable hand. “Morning, Johnny Ray,” I said. “Saddle Mabel for me, will you?” I asked, choosing an old Friesian Jack had purchased years ago.

“You’re gonna ride?” he asked, surprised. “For fun?”

I hated to ride, so the question was legitimate. “Not for fun,” I said.

Though huge enough to pull a fully loaded wagon or carry a knight wearing a suit of plate armor and weapons, Mabel was a placid mount and took easily to saddle and bit. She was too old for much work, but I needed her calm nature this morning. When he was done, I told Johnny Ray to lock the other dogs in the tack room with water and food and put a long leash on Cheeks. If he thought my orders peculiar, he didn’t say, just moved from task to task with an unrelenting, steady pace. While he worked, I made the first call to law enforcement.

“Sheriff’s Department.”

“This is Ashlee Davenport and I’d—”

“Hi, Ash. How you doing?”

“Buzzy?”

“’At’s me. Miss you at the hospital. Ain’t been the same since you left and went to the big city to work. What can we do for you?”

“Thank you, Buzzy. I’m at the farm, and the dogs brought something to me this morning. A child’s red sneaker with a part of a human foot inside.”

Buzzy went dead quiet. As his silence lengthened, I walked from the barn, cell phone held close to my ear. Buzzy was a paramedic who worked part-time for 911 and in various dispatch jobs for law enforcement. One could call dispatch any time and stand a chance of having Buzzy answer the phone. “You hear me?” I asked.

“Yeah, I hear you. You joking? Something about this new forensic course you took?”

“No joke. I wish it was. I found it at 7:52. The shoe and evidence are in the back of my old SUV in evidence bags, timed and dated, with audio description and a Chain of Custody.”

“You got a shoe with part of a foot. No body?”

“Not with me, no,” I said, managing to sound wry and jaded instead of near tears. “But I have a couple ideas where it might be.”

“How…? Never mind.” I could almost see Buzzy scratching his head as he pondered how to investigate and interrogate a toe. “I’ll get an investigator out your way ASAP. And maybe a crime-scene crew?” He was still perplexed. I’d had longer than him to figure out what came next and understood that I didn’t have a crime scene. All I had was a toe.

“Dogs, Buzzy. The canine team. To find the body. I’ve got four hundred acres here. There are farms on the east and the south, and an illegal garbage dump nearby. Not to mention I-77 close by, where a body could be tossed.”

“K-9’s up near Ford County helping track a suspect of a bank CEO shooting and aborted robbery. But I can send a crime-scene team out.”

I sighed. “Buzzy, I’m going to look for the body. I’ve got one of the Ethridge boys’ old tracker hound dogs—it’s done work for the K-9 unit—and we’ll be heading west from the barn. Cheeks has worked with horses before, so I’ll be on horseback. I’ve got my cell phone with me.”

“Why west?”

“Sycamore leaf,” I said. “There was a sycamore leaf in the laces.” I hadn’t even thought about my reasons for heading west until he asked and I paused, surprised. “I don’t have many sycamore trees on the property, but there’s a small stand of about four…. Just head west from the barn, Buzzy. And have your crime-scene crew take the shoe in the evidence bag and the voice tape in the back of my truck. I’ll provide digital photos later.”

“Gotcha. Cavalry’s on the way.”

Snapping the phone shut, I stuffed it in a pocket. Clicking to Mabel and Cheeks, I took up reins and leash. Together, we ambled to my truck where I removed the tote of forensic supplies, added in bottled water, a compass, sunscreen and a box of Fig Newtons, and looped the bag over the saddle horn.

Satisfied that I had what I needed and that the old dog would stay out from underfoot properly, I looked up at the saddle—up and up. My stomach fluttered at the thought of sitting up there with all that power beneath me. I braced myself. I could wait here like a good little girl and let the cops handle it. I could never get up on that horse and never go scouting to find the rest of the little girl. I could be a coward. Or I could do what needed to be done.

Wrapping the long leash around the saddle horn, I accepted Johnny Ray’s hand to mount the huge horse. I threw my leg over the saddle and paused, waiting until my stomach settled. I had been raised on a farm and lived for years with horses, but I had only recently learned to ride. I still didn’t like the height from the ground, and Mabel stood over eighteen hands high at the shoulder. Maybe I should have taken a smaller, less tranquil horse. Too late now. Bending, I held the glove in its open evidence bag down to Cheeks. “Find!”

Cheeks stood up on his hind legs, balancing, and sniffed the gloves. The scent of vinyl was strong, a source of confusion to the dog and he looked up at me dolefully. “Find,” I said again, and again Cheeks dutifully sniffed before dropping back to all fours with a pained grunt. I led him to the back of the SUV and out a ways, moving west. Again, I held the gloves out to the hound and commanded him to find.

The dog had been retired for two years, accepting a home on the farm because he could no longer keep up with younger dogs working as trackers. He was as old as dirt; he had an arthritic hip and his nose wasn’t the best anymore. But in his prime, Cheeks, named after his long, drooping facial skin, had been one of the best, and he hadn’t forgotten how to find a scent. Jowls dragging the ground, he put his nose down and walked in a large circle, sniffing. I turned Mabel as Cheeks circled once, twice, in a widening pattern. After a moment, he paused, his tail held erect, the ruff on his shoulders standing slightly stiff. “Yeah. Good dog,” I said. “Find.”

With a satisfied woof, Cheeks headed west, toward the stand of trees I had unconsciously thought of as soon as I’d seen the sycamore leaf twisted in the laces of the small red sneaker.

2

I held on to the saddle horn as Cheeks walked west, the reins twisted in my right hand. The saddle was an old western cutting saddle Jas had found at a sale when she’d started badgering me to learn to ride. The high cantle held my hips securely, the horn keeping me upright and in place when I wanted to slide left or right. I had never really understood how riders managed to stay on a flat English saddle. I was graceless on my own two feet, and any sense of balance I had on the ground was lost when perched up high. If I could have convinced someone to tie me in place on horseback, I’d have done it.

Cheeks pulled hard against the leash in a straight line west until we were over the first low hill, and then he seemed to have a problem. He moved left and right and back again, ignoring the hooves of the huge horse, so intent on his task that Mabel snorted and stomped in warning. “Easy, girl.” I pulled back on the reins, bringing Mabel to a halt. With my other hand, I gave Cheeks more leash, the dog’s movements pulling the nylon cord from the reel with a whirring sound.

The old dog was excited, moving left and right, around and back. I could envision the other dogs playing with the shoe, tossing it high and catching it, a game of tag and fetch all at once. Cheeks stopped, his haunches quivering, his nose buried in the tall grass. I knew what I’d find. More parts of the little girl.

Unexpected tears filled my eyes. Some mother and father’s special little girl…Using Jack’s cuff on my wrist, I dashed the tears away and tried to figure out what to do next.

I hadn’t considered what might happen if I needed to dismount. Blowing out a breath, I said, “Well, this is peachy.” Having no choice, I shifted my weight to my left leg, swung my right over the mare’s back and dropped down—and down—to the ground, where I landed hard. Mabel looked back over her shoulder with placid eyes, her thick black lips moving as she chewed on her bit. “Now what?” I asked the horse. Mabel sighed, her huge barrel chest expanding and contracting. Mabel clearly had no suggestions.

Cheeks looked up from the grass, his woeful eyes on me, wanting me to come see what he had found. I couldn’t figure out how to get to him and still keep the horse with me, too. Bad planning. “Some forensic nurse I’ll be,” I muttered. “Two hundred yards from the barn and I’m already useless.” Mabel dropped her head and chomped at the long grass. “How about you staying here awhile? Okay?” The huge black horse ignored me, munching on. With no choice, I dropped the reins, lifted the forensic tote off the horn and moved to Cheeks.

In the eight-inch-high grass, liberally coated with Cheeks’s drool, was a second toe. The digit was blackened, the toenail half off, its iridescent blue polish shining in the morning sun. Fighting tears, I took photos and marked the site with the spray can of garish orange paint in my bag, making a two-foot ring on the grass. I should leave the toe in situ for the crime team, but I worried a scavenger might make off with it. I added the toe to an evidence bag, labeling this one TOE 2, WEST FORTY PASTURE, with the date and time, and dropped it into my tote. I didn’t have a GPS device, so crime scene would have to document the exact location by the orange spray paint.

I called Cheeks to me and flopped on the ground beside him, giving him a thorough scrub along the ears and neck. “Good dog,” I said, my voice thick with misery. “Yes, you are. Good, good dog.” I cleared my throat and forced my shoulders to relax, talking to the dog for the comfort it gave me. “Those stupid men didn’t know what they gave up when they put you out to pasture, did they, Cheeks? Yes, Cheeks is a good dog.” I was supposed to give a tracker a treat when he was successful, but I had forgotten to bring dog treats. Cheeks didn’t seem to mind, pleased with the praise I heaped on him until I felt able to stand again.

Mabel looked at me and seemed to smile when I hooked the tote back over the horn and tried to lift a foot to the stirrup. I was several inches from success. Mabel’s shoulder was a full six feet from the ground. I stood five feet four. In shoes. And I wasn’t as limber as I used to be.

Leading the mare to an old fence post, I hooked Cheeks’s leash to the post and pulled Mabel around. She kept going, around and around. “You think this is funny, don’t you?” I said as I tried to position her for mounting. Cheeks sat and watched, his canine grin only egging Mabel on, I was sure of it. I climbed down off the post and tried again to get her into position, then climbed back up the cedar post. Mabel moved again, stopping just out of reach, her eyes on me over her shoulder.

I laughed, the sound shaky. Cheeks woofed happily at my tone. And suddenly I was okay again, or okay as one got when carrying a child’s toe in a bag. “Let’s try this again,” I said to Mabel, making my voice more commanding and less imploring.

When I got the Friesian to pause long enough for me to throw a leg over her back, I slung my body up and landed half in the saddle. Mabel was moving again, around in circles. By the time I got both feet settled in the stirrups, she had circled away from Cheeks, who sat panting in the rising warmth, but I had done it. I had retrieved evidence that might have been destroyed by rodents or birds, and gotten back on the mare.

Taking control of the situation and the reins, I retrieved Cheeks’s leash and ordered him once again to find. An hour later, after a meandering traipse through the west forty and onto fallow land, the old hound stopped near a creek and lapped at the water, as did Mabel. In horse and dog years, they were both in their seventies, content to be working as long as they didn’t have to move fast and there was plenty of water and liniment at day’s end.

The sycamores were just ahead, pale green leaves and curling bark and spinning seeds just released from the stems. It was spring, and everything was sprouting out green. As if he sensed that the day’s work was nearly done, Cheeks pulled on the leash and headed directly to the trees. The earth beneath the stand was stripped of growth, windswept, the center tree ancient, bigger around than I could reach, its bark curled and hanging loose from the trunk like pages of a book.

There were no toes on the bare ground. There was no sign of a body under the copse of sycamores. But there was a strong, musky odor, skunk-like, rank and bitter. Cheeks lost the scent.

Enough time had passed that I thought the Crime Scene team had probably arrived at the farm, so I tied off dog and horse under the trees and checked the cell phone. There were four bars of reception this close to the I-77 corridor, and I called the barn number. The phone had a loud outside bell with a distinctive chime and Johnny Ray picked up on the fourth ring.

“Davenport Downs,” he said. I could tell he had started drinking and I wasn’t really surprised. Johnny Ray didn’t much like cops. The thought of law enforcement on the premises would drive him to the bottle.

“Johnny Ray, are the cops there yet?”

“They’re here,” he said sourly.

“Let me talk to the officer in charge.”

“It’s your boyfriend.”

“I’m sorry?”

“Your boyfriend. The FBI agent. He’s done took over. And let me tell you, the sheriff’s stomping around, cussing under his breath. He’s mad as a dead hen.”

“Wet hen.”

“Huh?”

I shook my head in frustration. “Let me talk to Jim.” A moment later I heard his voice in the background as Jim directed the unloading of some sort of equipment. Closer, directly into the old black receiver, he said, “Ramsey.”

I felt an unreasoning sense of relief at the single word, as if someone had given me a hug and told me he would take care of me and any problem I might have. That was a feeling that didn’t last. “Hi. I’m glad you’re—”

“Ash? What the hell do you mean, taking off and ruining a crime scene. Damn it, don’t you know how hard it’s going to be find this body?”

“You have dogs?”

“Do what?” Jim said.

“Dogs. Do—you—have—tracker dogs?” I said it sweetly, so sweetly my mama couldn’t have sounded more sugary. Jim Ramsey knew what I sounded like when I was ticked off. About like I did now. “You know, to find this body? Or does the FBI have another way to locate a body in the rough? Like, oh, I don’t know, psychics?” When Jim didn’t answer, I said, “No. You don’t have any dogs. Because the dogs are up near Ford County. But I have one of the best tracker dogs in the state on my farm and he’s managed to follow the trail to the edge of my property. And he found another toe while he was at it. The site is marked clearly with bright orange paint.”

Jim sighed. “I’m acting like an ass, aren’t I?”

“Yes, you are,” I said pleasantly.

He chuckled. “I’m sorry. I have a good reason.” His voice lowered. “Guess what local is running this gig, because the county investigators are up at the bank thing in Ford County. Sheriff C. C. Gaskins, himself.”

“Johnny Ray told me. Gaskins is a bona fide male chauvinist pig, but you didn’t hear it from me. It’s been years since the sheriff had to do fieldwork.”

“And it shows, but you didn’t hear it from me. Couple deaf folks talking on cell phones. Head west, huh?”

“Yes, and while you’re at it, I’ll try to get Cheeks to find the scent again. We ran into polecat scent and his sniffer shut down.”

“Polecat…”

“Oh, yeah,” I grinned into the morning light, knowing Jim would hear the laughter in my voice, “and it’s quite, ummm, potent. Hope you brought overalls and boots to put over your fancy FBI suit and tie. It’s aromatic and a mite damp out in the west forty.”

“Well, hell.”

“Yep. I reckon that says it all fairly well. Bring some Tylenol and Benadryl, will you? I’ve been up too long, the glare is giving me a headache, and the dog is going to be sore from the exercise.”

“Will do. On the way.”

It was only after I cut the connection that I wondered why Jim was on the farm. What was the FBI’s agent coordinator of the Violent Crime Squad, from the Columbia field office, doing answering a call about a red shoe and two toes? On first glance, I would have assumed that someone in local law enforcement, probably C.C. himself, had called him in. FBI worked only on cases at the behest of local law, unless there was a task force already in place. Yet Johnny Ray had said C.C. was unhappy at Ramsey’s presence. Interesting.

I drank bottled water and shared the Fig Newtons with Cheeks, munching as I thought about the implications of a task force that had something to do with the red sneaker. There had been nothing in the local Dawkins Herald or the Ford County paper about a special task force. I only read The State newspaper on weekends, but there had been nothing there either.

Placing the food and water back into the tote, I studied the surrounding countryside. The farm was a bucolic setting in a rural county, though only half an hour from Columbia, the state capital, a sprawling city with big-city problems and big-city prices. Long, low rolling hills stretched out before me, pasture for Davenport Downs’s horse stock and acres sown with hay, alfalfa, soy beans. A few strategic acres were planted with mold-resistant sweet basil, parsley and other herbs, tomatoes, summer squash and zucchini. Most were only half-sprouted this early in the year. The smell of fresh-turned earth, pollen, horse and polecat; the sounds of birdsong; the far-off roar of a tractor carried on the wind—all were part of Chadwick Farms, my family home.

I didn’t like the conclusions I was drawing about what a task force might mean when combined with this isolated location and a kid’s shoe. A hidden grave, perhaps tied in with other graves. But I couldn’t seem to stop putting two and three and maybe forty-six together and coming up with…This was bad. This was very, very bad.

“Cheeks. Come,” I said, reeling the old dog in. “We have work to do.” I bent and searched the hound’s rheumy eyes. “Have you had enough time to get that polecat scent out of your nose yet?”

Cheeks looked back at me with his usual mournful expression.

“Let’s give it a try.” Leaving Mabel tied by her halter in the cool beneath the sycamore trees, her saddle loosened, her bridle pulled from her mouth and draped across her neck, I shouldered the evidence bag and held the sneaker-scented gloves out to Cheeks. He sniffed, black nostrils fluttering slowly. He looked up at me, his lower lids drooping, showing red rims. He sniffed twice more, securing the scent in his memory. “Find.”

Cheeks meandered out into the pasture and circled back. Out and back. I let him sniff again, trying not to encourage him in any particular direction. Again he moved out, nose to the ground, lifted, back to the ground. Around and around in an ever-widening circle.

Some hounds are air dogs, meaning they are so sensitive they can pick up a scent left on the air, carried on the breeze. Cheeks was a ground hound. Not a cadaver dog, either, one trained to find only dead bodies. But he’d searched for a little of everything in his years in law enforcement and I hoped he’d be able to find the scent again. Ten minutes of wandering away from the sycamores, he succeeded. His ruff bristled, his tail went tall and stiff and he pulled hard on the leash, his nose puffing at the earth.

On foot, we crossed the pasture, a field of hay to my left, fenced pasture to the right, separated by the grassy verge between. Cheeks’s nose followed a convoluted path. On the other side of the field, we entered a darker, cooler place, earth-brown and loamy, mixed trees, oak, maple, scrub cedar, swamp hickory, tulip poplar with its yellow blooms still turned toward the April sun.

Cheeks pulled me left into a slight depression and the earth changed beneath my feet, turning pale and sandy, the remains of the ancient river that once had flowed through the state and now was no more. I remembered the grit that fell out of the laces and the curled toe of the shoe. There had been yellow-white sand in the mix. No red mud, no yellow tallow—a poorly draining clay-like soil, which would be typical of the area—but grit and pale sand. I had recognized it but not placed it, not consciously, yet I had known that Cheeks would head in this direction when he found the scent again. Because of the sand.

My breath came harsh and fast as the old dog’s pace increased. “Good boy, Cheeks,” I muttered, stumbling along behind him. “Good old dog.”

He pulled me down a dip, past a lichen-covered grouping of boulders cluttered with rain-collected debris from a recent storm. Back up over a freshly downed tree, its bark ripped through by lightning, its spring leaves withered.

We were surely near the edge of Chadwick Farms property by now, over near the original Chadwick homestead, close to the old Hilldale place. I could see open land through the trees off to one side and the tractor I had heard earlier sounded louder. Cheeks sped up again, his gait uneven as his degenerating hips fought the pace, and I broke into a sweat.

And then I smelled it. The smell of old death.

I reeled the leash back short, keeping Cheeks just ahead. The hair on his shoulders lifted higher and his breathing sped up, making little huffs of sound. His nose skimmed along the sandy soil. The old dog put off a strong scent of his own in his excitement.

Rounding two old oaks, Cheeks quivered and stopped. He had found a scrap of cloth, his nose was planted in it. Just beyond was a patch of disturbed soil, the fresh sand bright all around, darkened in the center. More cloth protruded from the darkened space.

“Oh, Jesus,” I whispered, pulling back on Cheeks to keep him close. “Oh, Jesus.” It was a prayer, the kind one says when there aren’t any real words, just horror and fear. Cheeks lunged toward the darkened spot in the sand, jerking me hard.

“No!” I gripped the leash fiercely and pulled Cheeks away, back beyond the two oaks. With their protection between me and the grave, I stopped. Legs quivering, I dropped to the sand and clutched the old dog close. I was crying, tears scudding down my face. “Someone’s little girl. Someone’s little girl. Oh, Jesus.”

Cheeks thrust his muzzle into my face, a high-pitched sound coming from deep in his throat, hurt and confused. I’d said no when he’d done what I wanted. Shouted when he had found what he’d been told to find.

“I’m sorry, Cheeks.” I lay my head against his face and he licked my tears once, his huge tongue slathering my cheek into my hairline. My arms went around him, my body shaking with shock, fingers and feet numb. “Good Cheeks. Good old boy. You’re a hero, yes you are. Sweet dog. Sweet Cheeks.”

I laughed, the sound shuddering. “Sweet Cheeks. Jas would tease me all week if she heard me call you that. But you are. A sweet, sweet dog.”

The hound stopped whining and lay beside me, his front legs across my thigh. The pungent effluvium of tired dog and death wrapped around me. The quiet of the woods enveloped me. I breathed deeply, letting the calm of the place find me and take hold, not thinking about the death only feet away.

After long minutes, the tingling in my hands and feet that indicated hyperventilation eased and I stood. I checked my compass, dug out the spray can of orange paint and marked both trees with two big Xs.

“Okay, Cheeks. I hope you can get me back to Mabel. Home,” I commanded. “Let’s go home.” When Cheeks looked up at me with no comprehension at all, I held my jeans-clad leg to him so he could sniff the horse and said, “Find. Find.” He was a smart dog, and without a single false start led me back along the sandy riverbed. With the bright paint, I marked each turn and boulder and tree on the path, back into the sunlight and the pasture.

3

I shared more Fig Newtons with Cheeks—not the best food for a dog, but not the worst, either—took the animals to the creek for water, and used the quiet time to compose myself before moving horse and dog to the edge of the woods near the sandy depression. Once there, Cheeks and Mabel and I remained in the shade of the trees and waited for law enforcement.

Cheeks had developed a bad limp and wouldn’t make it back to the barn on his own four feet. His medication was in the kitchen, too far away to do him any good, and I could tell he was in pain. Not much of a reward for a job well done. “There’s a price to be paid for every good deed, sweet Cheeks,” I said, stroking the hound. “You find a body, you get aching joints. And I’ll bet you the cops are going to be mad at us for finding the body in the first place.”

Cheeks just panted in the rising warmth, his huge tongue hanging out one side of his mouth. In the distance, I heard the unmistakable sound of engines. Standing, I tied the dog off near Mabel and waited at the edge of sunlight.

Johnny Ray led the way along the fence that marked the pasture, driving his old truck, a seventies-something battered Ford pickup that he couldn’t seem to kill, though the motor sounded like a sewing machine that was missing a beat, and the paint was rusted and dulled out to a weary, piebald brown. Behind him came unfamiliar vehicles, a white county van, two four-wheeled all-terrain vehicles, a sport utility vehicle. For the most part, they stayed off the crops and on the verge of mown grass, but Nana would lose some hay. I figured she would have a few words to say to C.C. about that, words he wouldn’t like, and that would force him to apologize, at the very least.

The vehicles pulled up near the trees and killed the engines, pollen and dust swirling around us all. Special Agent Jim Ramsey unfolded himself from Johnny Ray’s pickup, wearing that distinct air of the FBI, suit pants and a heavily starched white dress shirt that glared in the sunlight. We were dating. Sort of. As much as I would let us. Jim was divorced, with a young daughter I hadn’t met yet. I liked Jim a lot, far more than I admitted, but he was nearly nine years younger than I. It was the age difference that I was having trouble with.

The sheriff, Johnny Ray and five cops, some in uniform, followed Ramsey from various vehicles. All were men except for one of the crime-scene techs, and I nodded to Skye McNeely, who waved back, holding up a box of Benadryl. She was my height, plump from motherhood, and newly married to the father of her child. I knew most the other cops from the rescue squad, where I volunteered. “Thanks,” I said, catching the box Skye tossed.

“Ashlee,” Sheriff Gaskins called, swiping an arm over his sweaty forehead. His pale skin gleamed in the bright sun, and sweat already stained the western-style suit coat he removed and tossed into the van. “The crime-scene guys say you did a good job with the shoe. Very thorough. Listen, thanks for getting us this far.”

“Welcome,” I said, watching the cops stack equipment and bags of fast-food breakfast. The smell of bacon and eggs made me salivate.

“That the tracker dog?” Ramsey asked.

I glanced at the animals and found Cheeks standing, straining at his leash, tail wagging. I realized he might know some of the cops, too.

“I know Cheeks,” Gaskins said. “Best tracker in the state at one time. Caught those bank robbers on motorcycles back in ninety-seven. Tracked them twenty miles to their homes.”

“That’s Cheeks. He’s still got a nose, but his hips are going,” I said.

I took two small pink and clear capsules back to my pack and buried them in the center of a Fig Newton. “Here you go, boy.” Cheeks took the treat instantly. Benadryl was an old veterinarian’s trick. It worked to combat all sorts of problems in older dogs and they could take it every day without upsetting their digestion. The dog rubbed his jowls up and down my leg in thanks and I gently smoothed the length of his ears. He sighed in ecstasy, a trail of drool landing on my boot. I’d reek by day’s end.

“Okay, people, we need to spread out, get as much work done as possible until the investigators get back from the bank scene,” Gaskins said behind me. I hid a smile at his officious tone. C. C. Gaskins was the highest elected law enforcement official in the county, but, while a trained investigator, he didn’t usually handle fieldwork. It was very likely that this was his first independent investigation in years. And he had an FBI guy watching.

“We’ll make a grid,” he continued, “and when the rest of the crew get here, we’ll go over it foot by foot until we find the body or rule out its presence.”

“It’s here.” I stood straight and walked back to the group of cops.

“Woman’s intuition is a wonderful thing, Ashlee,” C.C. said, his tone gently patronizing as he spread out a map of the county on the hood of Johnny Ray’s pickup, “but we need more to go on.”

I stood as tall as God had made me and put my hands on my hips. “Woman’s intuition?” I repeated. “I beg your pardon?”

“We need to go about this search in an approved manner until the dogs get here, Ash. That way we don’t mess up the crime scene. Not that we don’t appreciate all the help you’ve been to this point.” He turned his back to me in the sharp silence and concentrated on his map.

“So I can take myself home and knit awhile?” I asked softly. “Maybe bake cookies?”

Skye snickered before she caught herself and the back of C.C.’s neck burned a bright red. Johnny Ray’s eyes grew big and he hitched up his jeans, disappearing behind his truck. Ramsey glanced curiously at me.

I turned into my mother, God help us all. “I don’t think so. You see, C.C., I’ve had a course in the approved method of evidence collection and preservation, so I don’t think I’ll be messing up anyone’s crime scene.” I turned big, innocent eyes to the cops. “But if I were using woman’s intuition, I’d say the body is thatta way—” I pointed “—about a half mile into the woods, the path clearly marked with bright orange paint.”

C.C. shoved his cowboy hat back on his head and turned slowly from his map to me. He wasn’t happy. “I don’t think you’re—”

“Cheeks found the body,” I clarified sweetly. Skye glanced between us, then busied herself at the passenger seat and a big denim bag planted there. The other cops were promptly busy as well. Ramsey crossed his arms over his chest, cocked out a hip and watched me a little too closely for my comfort level, but I was mad. I hadn’t been anyone’s easy-to-dismiss little woman in four years and wasn’t about to start now.

“You took a dog to the body?” C.C. growled.

I smiled with all the force a Southern woman can offer such a simple act. “C.C., how is Erma Jean?” It was a polite way of telling a grown man that you know his mother and if he kept talking like a fool, she’d hear about it sooner than later. “She and my nana are on that county homeless-shelter committee together.”

C.C. cleared his throat and repositioned his cowboy hat yet again. Probably to keep the steam rising off his bald pate from curling the brim. My grandmother was a big contributor to local political campaigns. So was I. He wanted to shout at me, but there were witnesses. After a moment, C.C. said, “Well, I reckon we got ourselves a crime scene, boys and girls. Miz Davenport, would you please be so kind as to guide us in?”

There were a lot of other things I would rather have done than return to the wooded grave, but my hackles were up and I wasn’t about to head home now. “I’d be happy to, Sheriff.”

Raising my voice, I called, “Johnny Ray?” The stable hand lifted his head so only his cowboy hat and his eyes showed above the back of his pickup bed. “I want you to ride Mabel to the barn, see that Elwyn rubs her down with that liniment Nana made up, wraps her legs, and gives her some TLC. You can leave your truck here and when the other cops get to the farm, ride back with them to show them the way. Then drive your truck to the barn and take Cheeks with you.”

“Yes, ma’am, Miz Ash.”

I wasn’t sure Johnny Ray’d remember all that, so just in case he was a long time returning, I took the Tylenol and gave Cheeks the last of the water from my bottle. “Me and my big mouth,” I muttered to the hound. Cheeks rolled his eyes up to me in sympathy. Johnny Ray set the bit back in Mabel’s huge mouth, adjusted bit and bridle, gathered the reins and climbed into the saddle, sending Mabel’s huge hooves into a slow, stationary patter. Mabel didn’t like men, but she tolerated Johnny Ray well enough.

“Effective technique. Exactly who were you channeling just now?”

I closed my eyes hard for a moment and took a deep breath before turning to face Jim. “My mother. Josephine Hamilton Caldwell. She’s a debutante socialite in Charlotte.”

“A what?”

“Well, she’s a socialite who thinks she’s still a deb. Josephine is sixty-something going on sixteen, with a mouth so sweet, candy won’t melt in it.”

“And she’s why you get sugary as rock candy when you’re pissed off?” He was laughing at me, staring down from his nearly six feet in height, brown eyes glinting.

“As a technique for getting my way, it seemed just as effective as grabbing the sheriff by his privates and has fewer side effects than violence. Being Mama has never resulted in a lawsuit or my being arrested. At least, not so far.”

Jim barked with laughter, the sound startling Mabel, who jerked up her head and blew hard. She wasn’t happy about the stable hand being on her back and was looking for a reason to startle or kick. “Be good, Mabel,” I said. The mare flattened her ears and looked around at the human planted on her back, as if pondering how much effort it might take to dislodge him.

“I said, be good.” She rolled her eyes at me and seemed to consider my command. With a grunt, the mare lifted her tail and dropped an aromatic load, seven distinct plops before she moved away, into the sunlight, and headed toward the barn. The cops found it funny, but I knew when I’d been dissed. “Thank you, Mabel,” I muttered. But at least she did as she was told.

“You want to tell me about the land around here?” Jim asked, controlling his laughter admirably as we walked deeper into the shaded wood.

“The better part of valor?” I asked.

“Retreat isn’t a cowardly action. Not when dealing with a woman who can channel her mother.”

I decided I should let that one go and moved with Jim to the first orange paint mark, set waist-high on a poplar. Behind us, the cops shouldered equipment and followed. One cop complained about having to walk when there was a perfectly good four-by-four right there. C.C. handled that one, growling that the deputy needed some exercise and if he didn’t take off a pound or two, he’d be out of a job.

I didn’t know what Jim was asking about, so I decided on a tutorial. “We’re at the edge of Chadwick Farms, heading toward the eighty acres, give or take a few, of Hilldale Hills. The property between the farms is partial wetland, marked by a sandy riverbed left over from the Pleistocene Age, I think. Anyway, the Chadwicks haven’t farmed this area in decades and the Hills acres were left to go fallow for ten years.”

“Why?”

I told Jim that Hoddermier Hilldale had lain fallow himself in a nursing home, the victim of a stroke that had left him in a vegetative state. His son lived in New York and was less than interested in being a farmer. “Hoddy died in early winter,” I said, “about sixteen months ago. The son, Hoddy Jr., came home and leased out most of the acreage to my nana, who bush-hogged it and put it into half a dozen crops. Hoddy Jr.’s in the middle of investing heavily in the house, outbuildings and grounds as part of a bed-and-breakfast-slash-spa he and his gentleman friend think they can make a go of. Why do you want to know?”

Instead of answering, Jim asked, “Any graveyards nearby?”

It wasn’t an idle question. The man who walked beside me had morphed into a cop as I spoke, his face unyielding, warm eyes gone flat.

“Graveyards? I’m not…Wait a minute.” I stopped and turned slowly, looking up the old riverbed and back down, orienting myself. “I wasn’t thinking about where I am, but yes. This land’s been a family farm since the 1700s. The first Chadwick settled here because of the access to creeks and several spring-heads. When the original cabin burned down, the family moved closer to where Nana’s house is now. Somewhere near here are the old foundations and a small family plot. Why?”

Jim glanced back at C.C. and the men nodded fractionally. The cops seemed abruptly tense, as if I had said something important, but I had no idea what part of my soliloquy it might have been. Why would my family plot make them react? I pointed off to the left and jumped over a ditch, leading the crew to the next mark, this one on a low boulder buried in the earth. “What’s up, Jim? Why are you here?” I asked softly.

“The sheriff asked me in on this.”

“And?”

He seemed to consider what he wanted to say. “The red sneaker.”

“You’ve got a missing child, one who was wearing red sneakers?”

“Something like that.”

I figured that was all I was going to get from him so I just pointed to the next marker, but Jim surprised me. “You might remember that Amber Alert in Columbia last September?” When I shook my head no, he went on. “We’ve had four preteen blond girls go missing in Columbia in the last twenty-four months. The girl in September was one of them. Blond. Wearing red sneakers.”

Which explained why the coordinator of the Violent Crime Squad was traipsing through the countryside with mud on his polished black shoes. The air in the shadowed woods grew colder as I again considered what a body buried here might mean. “Why are you looking for a graveyard?”

“We found one of the missing girls in December, buried in a Civil War-era graveyard. So I was just curious,” he said as we rounded the pile of lichen-covered boulders.

“Putting together a profile,” I guessed.

“We’re working on it.” His voice lost inflection. Cop voice, giving away nothing.

“But keeping it out of the media,” I suggested.

“Not so much keeping it out as not sure whether we have a serial thing going here. Other than the general hair coloration and age, the missing girls have nothing in common.”

“I was trying to stay away from the evidence. I didn’t get up close to the burial site so I’m not sure if it’s near the old homestead. I looked one time and backed away. But it may be. And if so, we’ll see a family burial plot, gravestones lying on the ground where they were washed by a big storm before I was born.”

We moved the rest of the way in silence, the birds flitting through the trees as we walked, chasing one another in spring courtship, preparing for nesting time, an occasional squirrel making a leap from tree to tree. A hawk circled overhead in lazy spirals, searching for prey.

Not far beyond the fallen tree, its bark ripped away by lightning, we caught the smell of old death carried on the breeze. It had been bad before, but with the rising heat, the putrid scent had grown fetid and pungent. One of the cops swore, and I had to agree.

4

I stayed behind the two old oaks when we arrived; Jim stood at the edge of the grave site only a few feet away, hands on his hips while cops ran crime-scene tape from tree to tree at the sheriff’s direction. Though the scene was far from pristine, Jim obviously wasn’t going to add tracks or evidence to it until the photos were finished. Skye and Steven, another deputy, set up cameras and began to take digital and 35mm shots. Steven was giant, an African American with a shaved head and biceps as big as my thighs. Well, almost as big as my thighs.

“Ramsey?” Skye said almost instantly. “Headstones. I count three, lying flat.”

“Where?” he demanded.

“With this marker as six, we got one at two o’clock, one between ten and eleven, and a broken stone that looks as if it’s been moved recently at five and eight.”

I looked where she pointed, my gut tightening.

“Got it. Keep your eyes open for any other signs of grave markers,” Jim said. “Ash says this is nearly three hundred years old. A plot like this might have some uncarved markers, too, or some carved stone that’s so old it’s not easily recognizable as a grave marker.”

She nodded and began removing equipment from the cases they had toted in.

After the shots, Skye passed out protective clothing, paper shoes and coats that shed no fibers. Then she handed out gloves, evidence bags, small cans of orange paint, a one-hundred-foot tape measure for marking a grid and string to run from one spot to another, indicating straight lines. Together, working like a precision team, she and Steven measured the circumference and diameter of the space between the trees, marking off specific intervals around the vaguely circular area. They mapped it out on a pad, creating a visual grid to prevent the crime-scene guys from tripping, adding measurements and other indicators. Skye took more photographs while Steven recorded the dimensions into a tape recorder and on a separate spiral pad.

I had seen cops mark a grid on television using spray paint, and in class we had been lectured extensively on the proper way to handle a scene, but I had never seen one detailed in person. It was very clean and geometrical. I noticed that Skye and Steven walked carefully, studying the ground before putting down a bootie-clad foot. They avoided the center of the area, where clothing peeked from the makeshift grave. The alleged makeshift grave.

I knew that, until they saw human remains, it would be only a suspected grave. All this effort and we didn’t even know for certain if there was a body or if it was human. The toe could have come from somewhere else. This grave could be a dog, buried in a pile of rags. Not a child. It could be anything. I wanted it to be anything, anything but a little girl.

All the cops seemed to have a job except the sheriff. Gaskins stood back and looked important. Jim was out in the trees, walking a course around the site in a spiral, marking things on the ground with painted circles. A quiet hour passed during which I found I could disassociate myself from the meaning of the scene and watch. Perhaps that was part of my nursing training, being able to put away normal human feelings and simply do a job. The cops moved in slow, studied precision, touching nothing, recording everything on the detailed evidence map that would be one result of today.

Into the silence that followed I said, “Cheeks buried his face in that strip of cloth right there. There’ll be drool and hair on it. And I think my other two dogs—” I paused, breathless as the meaning of my words slammed into me. I licked lips that felt dry and cracked. “I think they actually dug up the body and rolled in it. You’ll want to take samples from each dog, I’m sure.” The cops were looking at me. I thought I might throw up. I pressed my hand to my stomach. “Johnny Ray has Big Dog and Cherry both locked up in the barn.”

The cops went back to work without a word. Gaskins called in my information to one of the investigators driving in from Ford County and told him to take care of the dog samples before coming out to the site. No one said anything much after that.

The preliminaries over, Jim donned fresh gloves and booties and tossed several evidence bags into a larger bag he marked with black ink. With the digital camera slung over his shoulder on its long back cord, he followed a straight line he referred to as CLEAR. Walking slowly from the two oaks into the center of the small clearing, back hunched, eyes on the ground, he marked evidence as he moved but left each item in place, a paper bag beside it. When he reached the scrap of cloth that Cheeks had drooled on, Jim looked up at me with a question on his face and I nodded. “That’s the one.”

He photographed the scrap of cloth where it lay and took another shot in relation to the total scene. “Document contaminant information,” he said to Steven, “with the year, case number and item.”

“Got it,” Steven said.

Jim marked the photo with the same numbers and continued his slow methodical pace to the center of the circle. Taking several shots, he backed out the same way he’d gone in, and handed the photos and camera off to Skye. “You the acting coroner today, too?”

“I have that pleasure,” she said, her tone belying the words. It was common in poor counties for law-enforcement officers to be trained in several different fields. Skye was a trained crime-scene investigator and also worked as part-time county coroner. She moved closer to the edge of the clearing. “What do we have?”

“Protruding from sandy-type soil, I see part of a small skull,” Jim said, “presumptive human, part of what looks like a femur and lower leg bones, and clothing.”

“Ah, hell,” Steven said.

Skye’s expression didn’t change. Stone-faced, she stepped to the denim bag I had noticed earlier on the passenger seat of the county van and removed a folder marked Blank Coroner Forms. “Could it be from the 1700s?” she asked.

“No,” Jim said. “Connective tissue is still in place. In this kind of soil, well draining but under a canopy of trees, I’d guess it’s not more than a year old.”

Something turned over in my belly, a slow, sickening somersault of horror. Silently, I walked away, along the length of the old riverbed, back out of the shadows. When I reached the pile of boulders, a single shaft of noontime sunlight found a way past the foliage, falling on the topmost stone. Without thinking, I climbed up the pile, pushing off with booted feet against the slick rock until I was perched on top, my arms wrapped around my knees.

There was a body buried in the woods near my house. The body of a child, taken by someone intent on evil and buried in the shadows, alone and isolated. I had discovered it…. Most likely a little girl. I had discovered her.

My family would be questioned by the police, possibly by the FBI. My house and grounds would be overrun by cops. And I had nothing to tell them that would explain how the body had ended up on Chadwick Farms property. Nothing to tell the parents, if I ever met them. Nothing to tell her family or mine.

I was trained to gather forensic evidence but my forte was nursing, gathering evidence on living human bodies, evidence that police would need in later investigations and trials. Such evidence was often lost during medical procedures, especially during emergency medical treatment where dousing the victim with warmed saline or Betadine scrub washed away vital clues to the perpetrator, and cleaning skin for IV sites, bandages, or application of fingertip epidermal monitors hid defensive wounds and damage—evidence that should have been preserved for standard and genetic testing.

I wasn’t trained to work a crime scene where the victim was dead.

A child. Dead in my ancestors’ family plot. And my dogs had surely rolled in her grave. I put my head on my knees and cried, trying to keep my sobs silent. An early mosquito was attracted to my position and I killed it as it punctured the back of my hand for a blood meal. A squirrel chittered at me from a low branch. Long, painful minutes passed. Finally, I took a deep breath.

I heard the sound of vehicles and voices in the distance and knew that the other investigators had arrived. Sheriff Gaskins had been keeping in touch with the men and they would know already that there was a body. They didn’t need help to follow the trail, and I didn’t especially want to be caught sitting on top of a pile of big rocks crying my eyes out, so I wiped my face, slid back to the ground and returned to the site.

Jim met me partway, his eyes tired, face drawn, his paper clothing left at the site to reveal the dress shirt, tie and slacks, his entire lanky frame speaking of exhaustion. “You okay?” he asked.

“I’m lovely. Just hunky-dory. You?”

His smile was crooked. “I’ve had better days. But I need your help.”

“What for?”

“I need you to tell me about that homestead and grave plot.”

“Yeah, that’s what I figured would happen.” I turned my back, shoulders stiff and angry. “You’re going to have to question all my family, aren’t you? My nana, my daughter. All the help.”

“Like I said. Better days.” I could hear the strain in his voice, but I still didn’t turn around, even when he put a hand on my shoulder, the first comfort he’d offered. “But not me. I’m too close to you.” His tone softened, as if to both warn and console me at once. “It’ll be one of the other agents. It needs to be thorough to rule out your family, so it won’t be pleasant.”

I wiped my eyes again, fighting tears that were half selfish, half for the child buried in the sand just ahead. “That’s just great. Do you have any idea how many Chadwicks know about this site, either by family history or by actually coming out here to see it? Do you know how big an investigation you’re talking about?”

“Tell me.”

I looked up at him. He wavered in a watery pattern of tears. “At the last family reunion back in 2005, over 225 people attended. Lots more couldn’t make it. My family is scattered all over the nation. We’re two races and all ages, from the late nineties to not yet born. We started on a family genealogy chart last year, and it points to dozens of other family members—dozens, Jim—that are lost or missing. Hundreds of us live in this state alone.”

“You’re kidding.”

“Do I look like I’m kidding? You’re going to have to talk to all of them, aren’t you? And before you ask, yes, we’ve had our share of spotted sheep.”

“Don’t you mean black sheep?” he said, amused.

“Not with my family’s ethnic mix. And some of our spotted sheep have done jail time.”

Jim swore, his amusement gone.