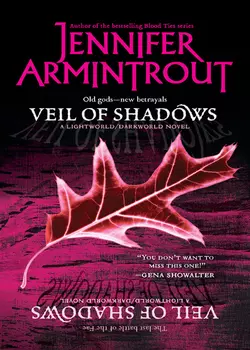

Veil Of Shadows

Jennifer Armintrout

With the immortal denizens of the subterranean Lightworld and Darkworld societies locked in battle, the heiress to the Faery throne is exiled to the Human realm above.Accompanied to the Upworld by her mother's trusted advisor, Cerridwen is bound for Eire—and the last Fae stronghold on Earth. But even this fabled colony is no true haven. In the absence of the true Fae monarch, the formidable Queene Danae established herself as ruler—and she does not wish to relinquish her power, especially over the devout Humans who live among the Fae as servants.Torn between her own beliefs and the ideals her mother died for, Cerridwen searches for clues to her destiny—is it on Earth among the Humans, or beyond an ethereal portal, in the immortals' ancestral home? Neither path can avert bloodshed—and the choice may not be hers to make.

Praise for the novels of Jennifer Armintrout

“Every character is drawn in vivid detail, driving the action from point to point in a way that never lets up.”

—The Eternal Night on The Turning

“[Armintrout’s] use of description varies between chilling, beautiful, and disturbing…[a] unique take on vampires.”

—The Romance Readers Connection

“Armintrout continues her Blood Ties series with style and verve, taking the reader to a completely convincing but alien world where anything can—and does—happen.”

—RT Book Reviews on Possession

“The relationships between the characters are complicated and layered in ways that many authors don’t bother with.”

—Vampire Genre on Possession

“[This book] will stun readers…. Not to be missed.”

—The Romance Readers Connection on Ashes to Ashes

“Entertaining and often steamy romances run parallel to the supernatural action without dominating the pages.”

—Darque Reviews on All Soul’s Night

“Armintrout pulls out all the stops…a bloody good read.”

—RT Book Reviews on All Souls’ Night

Books by Jennifer Armintrout

Blood Ties

BOOK ONE: THE TURNING

BOOK TWO: POSSESSION

BOOK THREE: ASHES TO ASHES

BOOK FOUR: ALL SOULS’ NIGHT

The Lightworld/Darkworld novels

QUEENE OF LIGHT

CHILD OF DARKNESS

VEIL OF SHADOWS

JENNIFER ARMINTROUT

VEIL OF SHADOWS

A LIGHTWORLD/DARKWORLD NOVEL

This book is dedicated to

all the family members who were angry

that I dedicated the last book to someone

who won the dedication in a Twitter contest.

Contents

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Acknowledgments

Prologue

When the first of them appeared, there were skeptics. Some simply did not believe that these “creatures” calling themselves Faeries or Angels or Vampires or whatever were not part of some elaborate hoax. Perhaps a conspiracy, their own country’s governments, or a shadowy world government, working to manipulate them. Into doing what, they did not know, but still they doubted what had come to pass.

There were others, though, who did not believe the event to be false. And though they were right, they were ridiculed. Their near-instant belief that their salvation had come—or, as some believe, their damnation, and they were, perhaps, closer to the truth—obscured how very serious and dangerous the situation was.

The initial shock of their appearance, whether it inspired pleasure or suspicion, did not last. For not all the creatures were kind, and some…some had to feed.

So, it was with fear and trepidation that the Humans began to move underground. Into shelters constructed for an imagined future war, into spaces that were undesirable before the creatures came.

And since they fled of their own accord, the visitors assumed the surface of the Earth with gratitude.

Years went by. Ten, twenty, a hundred. And in the vast cities that had formed beneath the surface, a rumbling of what had happened generations before twisted, became something sinister. The creatures had come, forced the Humans belowground, ruled them with hatred and cruelty. And though no immortal creature could remember this being so, it could not stop the rage of the Humans. It could not prevent the war.

Despite their numbers, their experience and their sheer power, the immortals lost the fight. Driven underground themselves, they eventually forgot their hatred of the Humans who had cast them out. One by one, they gave up striking back at the Humans, and began striking out at one another.

The wars that raged beneath the surface formed the Lightworld and the Darkworld, as they came to be known. Two separate factions with a common enemy, but different goals. And they hated each other.

The Lightworld longed for the Earth to be restored to the Fae races, as they had ruled parts of it long before Humans learned to interfere with the land. The Darkworld, those who did not believe in their right to rule over the Humans above, who only wished to return to the way they once were, found themselves outcasts, forced to the worst parts of the Underground.

In the cities of the Upworld, the Humans continued on, always aware of what lay beneath their feet, but never really knowing what the murky fear was doing. It was better for them, that way, for what you never know cannot truly hurt you.

One

“You were lucky beneath Boston,” the old ferry captain, Edward, said. “You know what happened to them down in New York? Flooded ’em out. Drowned ’em. Them creatures that didn’t drown, them were hunted by the Enforcers and killed.”

Cerridwen opened her eyes, reluctant to leave the sleep that had been her refuge from the terrible sickness she’d felt while awake. The vessel they had departed on that morning, a ramshackle boat the man had kept calling a ferry—not, Cedric had assured her, in mean-spirited jest toward their kind—still churned and tossed. How the Human could stand, so straight and balanced, as the craft pitched from the crest of one wave to another, Cerridwen did not know. But the motion made her stomach seize, her head go dizzy.

Cedric and the rest of the Fae they traveled with seemed unaffected by the motion, as well. Cedric, particularly, seemed to revel in their time on the sea, standing at the prow, listening to the bearded old man call out stories against the wind and the spray. Though the blinding sun had set, Cedric still stood in the place he’d inhabited when she’d fallen asleep. Face turned toward the horizon, an expression of serene pleasure—or as much of one as Cerridwen had ever seen on the ancient Court Advisor. Calmness gilding his features the way the morning sun had, it seemed as though he had completely forgotten the precarious position of their future, and the violence they had left behind.

Cedric had been alive long before the rending of the Veil had spilled all the creatures of the Astral onto Earth. To him, the sun, the wind, the water were all old friends. They greeted him with familiarity and Cerridwen realized how much he must have longed to escape the cramped and dank Underworld. To her, born after the Fall and in the cavernous Underground, the elements showed only hostility.

Cedric nodded, but did not face the old man. “I did not know there were other cities…I thought that most had died in the battles, and that whoever remained of us were underground in the same area. That it was just too large—”

“If you’d kept going, you’d hit the end.” Edward spoke with such authority, it was as though he’d been there.

It was not impossible to believe. Cerridwen had always wondered that the boundary between the Lightworld and the Darkworld was so well defined, and yet no one seemed to know if there were other boundaries, and if there were, where they lay.

“Everyplace where they didn’t just get rid of you. New York, that was one of them. Boston, well…you saw what that’s become. No one wanted to stay, once your kind were underground. Up and left. Most of the cities went that way. Decided it was easier to give up and leave than try to live with knowing what existed just beneath them.” The old captain seemed to be amused by this.

It was not amusing. The Humans had forced them underground, then abandoned the very spaces they’d coveted for themselves. Cerridwen wondered if she’d ever understand these strange beings.

She sat up, her stomach lurching. But before she could speak, Cedric turned, the serenity bleeding from his expression. “You are awake.”

She wished he would not look at her with such concern. Concern she did not merit. “As you can see.”

“You should rest. The mortal healing has only restored your body. The sickness you have felt—”

“Seasickness, the Human says.” She closed her eyes. It only made the sensation worse. “Is this because I am part Human? The element does not affect you.”

“It is not because of your Humanity. It is because you have never been outside the Underground.” He held out his hand for her, and when she did not move to take it, he stooped and lifted her, blanket and all.

“Put me down!” She had enough strength, despite her sickness, despite the wound in her ankle, to be outraged.

He did not listen, and she had not expected him to. He set her down gently in the place where he’d been standing before, let her lean on him for support. “Look out there, at the horizon. The place where the sky meets the water.”

“I know what a horizon is,” she snapped, pushing down the finger he used to point the way.

“That won’t help,” Edward called to them cheerfully. “Not a fixed object.”

“It will help,” Cedric reassured her. “We see things differently than they do.”

She squinted against the sun. Its light did not assault her the way it had when they’d first emerged from the Underground, but she had to blink against it to make out the difference between the dark of the water and the blinding curtain of sky.

“You are resisting the elements, because you are unfamiliar with them. You fight against them,” Cedric told her, and again he pointed out to the horizon. “They do not fight against each other. See how when the waves rise, the sky relents? You must learn to do the same.”

It did make her feel a bit better. Though the craft still rocked against the waves, she did not struggle against the movement in an attempt to keep herself upright. Instead, she let the motion rock her, and she did not stumble or fall.

“Getting your sea legs,” the old Human said. “You’ll need ’em—you got a long way to go still.”

“I thought we would meet up with Bauchan by nightfall.” Cerridwen did not look away from the waves, or lean away from the comforting presence of Cedric standing behind her.

“We will,” Cedric began. “But we will meet up with the ship that the rest of the Court is already on, and then we will sail across the sea. The False Queene’s Court is on an island, what you might think of as the Land of the Gods, if your mother taught you about it.” His tone suggested that he did not believe Ayla had instructed her daughter correctly in this matter, and he continued. “It was less difficult for us to travel when we lived on the Astral Plane. We merely spoke the words, or imagined the scene, and we could be anywhere.”

“Not so much anymore, huh?” Edward called down. “Don’t you worry, though. The captain of the Holyrood will get you where you’re going, if not as quick as you’re used to.”

Cerridwen grew annoyed at the weathered Human’s constant interruptions, and limped back to her pallet in the shade. She crouched and flared her wings for balance, resting her weight on the front of her feet. Something about this posture made Cedric look away, but she did not know what could bother him so. Probably, he still hated her for her stupidity. It was his right. She had foolishly betrayed her mother, her entire race, and gotten so many killed in the process. Both her parents, though she had not known it at the time, and countless guards and Guild members. If Cedric wished to hate her for all time, well, she would not argue with him.

But he had saved her, had he not? Not just from the Elves, but from the Waterhorses in the Darkworld, and again in Sanctuary. When she’d been willing to stay and die beside her mother, he’d dragged her into the Upworld. When she’d been too weak to continue, still he’d carried her, despite his own fatigue. Perhaps he did not hate her. He was angry with her, that much was certain. He had made a promise to protect her, but if he truly hated her, would he keep that promise?

She was too weary to think of this now. There would be a confrontation with Bauchan when they reached the ship called the Holyrood, that was certain. At the very least, he’d question her right to kill her mother’s treacherous Councilmember, Flidais, who had been working with him. In the end, no matter her reasoning, he would be upset over Flidais’s death and would not accept her as Queene, being eager to steal away her inherited Court for his own False Queene.

A thought struck her, one she did not like. “Cedric, if there are others…other Undergrounds, like ours, could there not be other Queenes and Kings? Who believed that they deserve to rule over all the Fae?”

“I had thought of that.” Cedric sat down, his legs folded beneath him. His wings, papery thin and colored like those of a moth, shivered on his back, sending motes of blue powder through the beams of sunlight that reached beneath the ferry’s upper deck. “It is heartening to think that there are more of us. That might prove useful, especially if we can garner their sympathy in our plight. But there is no guarantee that we will be able to contact them, or that they will look kindly on rejoining Mabb’s Court.”

Cerridwen eased her weight onto her uninjured foot. “Mabb was the Queene. The true and rightful Queene of the Fae from before our fall to Earth. All other Fae fought behind her in the war against the Humans, did they not?”

“She was. They did.” There was sadness in his eyes as he talked about her. Cerridwen, born after Mabb’s death, had never seen the Faery Queene who’d preceded her mother. The rumors of Cedric’s involvement with Mabb had persisted, though, and Cerridwen wondered if lost love was what made him seem so very troubled now.

“Mabb was not a popular ruler. Not once the Veil was torn asunder. Some blamed her, for allowing Humans to glimpse us as we were trooping, or for not punishing those in her Court who intentionally sought out the company of Humans.” He fell silent, looked out toward the water. “Ah, well. It is not the past that will help us now. You will meet Lord Bauchan tonight. Are you ready?”

She snorted. “You make it sound as though I am going to war.”

“You are, in a way.” Though he shrugged, his expression held a seriousness that Cerridwen did not like. “You are fighting for control of your Kingdom.”

Another derisive sound crawled up her throat, and she swallowed it. “Some Kingdom. My inherited subjects ran and left my mother when she needed them most. If they cared so little for her, why should they care about me?”

“By your same thinking, why should they care about Queene Danae enough to bend their knees to her?” He was right, and infuriatingly reasonable. Cerridwen said nothing. “Your mother would not have wanted you to give up. She did not wish to see her Kingdom in the hands of this False Queene. Perhaps…” he continued, then stopped himself.

She had seen him do this very same thing with her mother. Though he might have an idea, he would withhold it until invited, and would not speak out above his station to the Queene. Whether he did it out of habit or he held Cerridwen in the same respect that he’d had toward Ayla, she did not know. But it pleased her, nonetheless, to be treated as though she were worthy of deference. “Perhaps what?”

“Perhaps, when we see Lord Bauchan, I should speak on your behalf.”

That destroyed the illusion. He thought she was incapable of speaking for herself without some disastrous outcome. A part of her agreed with him, was thankful, even, that she would not have to pretend at courtly manners and political thinking. She had no head for either of them, and even if she had, her hatred of Ambassador Bauchan, the fiend who had come to the Lightworld with the intent of causing civil war, would have broken her concentration.

“Yes, fine.” She nodded, a bit too enthusiastically. “It would help keep up the pretense that you are the Royal Consort.”

He nodded. “Yes, that is something that needs to be established early with Bauchan. I would not think that seducing the Royal Heir would be below him, if it would give him what he needed to succeed at his own Court.”

“No longer the Heir—the Queene,” she corrected, though even in her insistence the title was too new to be comfortable for her. “Perhaps we should do with Bauchan as we did with Flidais. After all, is he not guilty of the same offenses she is?”

“He is not,” Cedric stated firmly. “Bauchan came to your mother’s Court with no deception that we could not see, and in spite of the fact that your inheritance comes from Mabb’s succession, he was not considered your subject when he arrived, and this Queene Danae is unlikely to accept your killing him. Flidais hid her plans, and turned traitor to her own Queene, in contrast. Besides, we need Bauchan. He is our only guide to finding Danae’s Court and some measure of safety.”

Silence fell between them again, the only sound the mechanical chug of the ferry’s engine and the soft slap of the waves against the tiny craft. The sound had lulled her to sleep that morning, and, in hearing it again, woke the vestiges of those things she’d seen in her fitful slumber. Without knowing why she did so, she suddenly blurted, “I had a dream, earlier. While I slept from my sickness.”

Cedric made a noise of uncommitted interest. “Do you believe it means something?”

Did she? It was such a simple dream, and she had never truly believed in such nocturnal signs. “I do not know,” she answered honestly. “If it does mean anything at all, I would not know how to interpret it. And I have never given much credit to dreams.”

“If you tell me what it was about, I might be able to help you.” He looked out to the water again. “Or, if you prefer to keep it secret, I will understand.”

“There is no secret to keep. It was not disturbing, or terribly important.” That was not entirely true. When she thought of the images, a feeling of grave urgency taunted her. “I saw a forest, as though I were standing in it, and I was alone. I came upon a clearing to see a white bull.” She closed her eyes, and in her mind saw the shaggy, matted coat of the animal as it stood, almost ghostly white, in the darkness. “In the sky above the treetops, the stars made out the form of three triangles, locked together in such a way as to make one large copy of themselves.” She stopped herself. “Can they do that? Stars, I mean? Do they show pictures?”

“They show forms that Humans can navigate by, forms that tell a story. But they cannot twist themselves into something they have not shown before.” He seemed troubled, but in a flash that troubled expression was gone. “Ah, well. It was probably just a dream. Nothing worth worrying over.”

And though she might have agreed with him before, the vision had crept back into her mind, insisting upon a place there. It would not have done that, if it did not have something to tell them. She did not know how she was so certain of this, but she was, and his studied disinterest irritated her.

“I am going to go watch the sea,” Cedric announced, as though it were not a dismissal. “You could come, if you wished. The ferryman is good company.”

“Human company,” she said, waving a hand. “If that is your idea of good company, then you may indulge all you please.”

His smile was tight, pasted on. “Yes, it will do you good to rest before we meet with Bauchan.”

Only after he strode from beneath the deck, his tread heavier on the floor than any immortal creature’s should be, did she realize how very much she’d sounded like her old self, the immature child who’d hastened her parents’ deaths through impatience and petulance.

The ferry arrived at the place where Bauchan’s ship was harbored just after nightfall, almost to the exact minute, that the ferryman had promised. At least, that was what he told them, and Cedric had no reason to doubt the Human.

Though Cedric had been sad to see the sun set—having no idea when he would get another opportunity to view its radiance and after all the years spent underground having become greedy for it—he recognized that it was for the best that they make this meeting under cover of darkness.

The ship was not moored at the docks but anchored at the mouth of the harbor—the farther away from Humans, the better, in Cedric’s opinion—and the ferryman blew his horn as they approached. Lights appeared at the rail of the ship’s deck, high, impossibly high above them, and as the little boat drifted sideways to meet the wall of red-painted steel, the ferryman silenced the engines and called out a friendly “Halloo!” to figures that Cedric could not see from his vantage point.

“What if they will not let us board?” Cerridwen fretted beside him. She stood, a blanket clutched tight around her shoulders as if ready to run, though there was no place to go.

The six guards who had accompanied them from the Palace, and who had been the last witnesses to the carnage wrought in the Underground, stood in their regal finery, toting the bundles that held all the wealth they were able to recover from the sacked Faery Palace. Cedric looked them over with some dismay. Though their clothes were that of courtiers, they held themselves in the stiff manner of soldiers still. Cedric only hoped that Bauchan would be dazzled by the velvet and silk, and not give a thought to the way the men seemed ready to throw themselves over the Royal Heir at the slightest sign of, well, anything, soldiers being more loyal than courtiers.

Cedric looked at Cerridwen now. She was, for all intents, the Queene. But she was hardly fit for the post, and hardly looked it. No matter how she’d carefully bathed and dressed, she could not hide the hollow look that sorrow had imprinted on her, nor the fatigue from her injury. He should say something to her now, to reassure her, but he could not. He did not know what would happen to them, should Bauchan refuse to bring them to Queene Danae’s Court. He did not expect such a refusal, but for the past two days its possibility had been much on his mind.

Instead of comforting her, he concentrated harder on making out the conversation between the ferryman and the Humans on the ship. For their part, he could hear very little, but every word that Edward spoke was exactly as Cedric had coached, but cushioned in the gentle, rolling tones the Human preferred, as though no word should be hurried from his lips, and nothing of import should pass that way, either.

“Just another load of special cargo,” he called out to the Humans high above their heads. “You’ll be wanting to drop the gangplank, so I can unload it.”

There was a pause, mumbling that was not clear.

“Oh, he’s expecting this delivery, all right,” Edward said easily. “Brought special by his importer, you know.”

More of a pause, more mumbling. Cedric’s antennae buzzed against his forehead, and he smoothed them back against his hair, willed himself to be calm.

Whatever they had asked him, Edward managed to sound very put off by it. “Well, go on and check with him, if you gotta. But I know what I gotta do, and that’s get back to the missus before sunup, or she’ll have my hide and I don’t want to think what else…. Get goin’, then, and give me a rope to tie up by.”

The Human’s words were met with a loud slap against the deck, the rope falling, if Cedric guessed correctly. Then, nothing. Silence, broken by the sound of the water trapped between the two vessels as it knocked from one hull to the next. Edward did not come down from his little wheelhouse, nor did he call out any encouragement to them.

“What is happening?” Cerridwen hissed, as if afraid to interrupt the gentle sounds of the night sea.

Cedric did not raise his voice much above a whisper, either. “He will not call down to us now. Sounds carry across open water, and if any Enforcers patrol the harbor, you would not want them to overhear exactly what cargo is being traded, would you?”

She shivered, sank farther into her blanket.

Something screeched, and Edward appeared below the deck, waved to them to come to the back of the boat. He doused the lights on the craft, all but the small green and red ones that shone over their heads to indicate their presence.

“He wants to ‘inspect the cargo,’” Edward said, rubbing a hand across his grizzled jaw. “I thought you said you knew these ones?”

“We do.” Cedric looked to the source of the screeching noise, saw through the darkness to where a door had opened at the side of the ship. “I did not say that we were on the best terms.”

“Best terms,” the old Human spat. “I don’t like the sounds of that, and I won’t lie and be telling you otherwise. We run a respectable operation, my wife and I, and I hope you’re not preying on our good nature.”

“Sir, I assure you, if we are not welcome here, we will not trouble you further.” Cedric did not know how he would make good on that promise, but he did not wish to think on it now. Right now, the most important matter was to convince Bauchan.

Humans called out orders as quietly as they could from the large boat, and Edward answered them in hushed tones, as well. The result of their combined efforts was the placement of a long walkway between the two vessels, which, under cover of darkness, a few Fae shapes made their way across the expanse.

“Why do they not just fly between?” Cerridwen grumbled. Cedric did not reiterate the danger of their situation; if she did not realize by now how very close to Human discovery they were, she would never realize it.

Bauchan was the head of the three Faeries that joined them on the little boat. He looked them over with a bland expression. The two that followed him flanked the walkway, as if guarding it. Perhaps they were meant to stop them from rushing onto the ship without permission. Cedric smiled at that. Only someone like Bauchan would feel the need to make such a display of strength, someone who had so little to begin with.

“I was expecting Flidais,” Bauchan said finally, with a little shrug, as though he was not as put out as he had expected to be and was a bit relieved at that. “Where has she gone?”

“Dead.” Cedric answered, and prayed the ferryman would not know enough to correct him. “Along with Queene Ayla.”

“I am sorry to learn of her passing.” Bauchan bent his head in reverence. “She must have been prepared for the consequences, though. Anyone who chose to stay in the Underground must have realized it was suicide.”

From the corner of his eye, Cedric saw Cerridwen stiffen. He reached for her arm, took her hand at the wrist, hoped it would be enough to signal how crucial calm was at this moment. “Queene Ayla understood the danger, but thought it cowardly to abandon her subjects. It was her last wish for your good Queene to take the Royal Heir into her protection.”

“The Royal Heir?” Bauchan’s eyes, instantly alight with greed, fell on the unlikely shape huddled in the blanket. “We have met before, at your mother’s audience,” he said smoothly, bowing before her. “It is an honor to be in the presence of so great a beauty again.”

Cedric cleared his throat. “She is wounded, and will need healing. There is only so much that mortal medicine can accomplish, and I fear that limit has been reached. Also, she comes with this small entourage of advisors. I trust that this will not be an imposition, either.”

“Advisors? What need has the Royal Heir of advisors, if she is entrusted to my kind and attentive care?” Bauchan looked over the guards with a critical eye. He was looking for the trick, for some crack in the lie, but he was not intelligent enough to see it beyond the wealth on the Faeries’ backs.

“She will need help managing the meager fortune she brings to sustain her, of course. And one cannot expect the Royal Heir to personally handle the duties of setting up a new—if somewhat diminished—household in Queene Danae’s Colony.”

“Yes,” Bauchan agreed, smiling what must have been the single most insincere smile in the history of all the Fae. “I do think it will be quite a change for her, but a positive one, for all involved. Queene Danae will not see this as an imposition, but a blessing for her Court. And you, were you not one of Queene Ayla’s advisors? Do you wish to maintain that position within the Royal Heir’s household?”

Cedric remained stone-faced in contrast to the Ambassador’s oily graciousness. “Your kindness is appreciated. I travel with the Royal Heir not as an advisor, but as her betrothed. It was decided not long before your arrival at Queene Ayla’s Court that Cerridwen and I should be mates, and the Queene thought it would be in the interest of all involved if such an agreement was not thrown over just because of present dangers.”

Bauchan’s smile faded a little at that, and it pleased Cedric. No doubt that upon setting eyes on the Royal Heir, Bauchan’s mind had spun with all the possibilities for advancement that such a prize could bring him. He’d likely already imagined the reward he would get from Danae for delivering the direct Heir to Mabb’s throne. From there, it was a simple seduction and a carefully constructed revolt to overthrow Danae and make Cerridwen Queene, and him to rule as King beside her. It did not surprise Cedric that Bauchan would be among the many who would seek to gain from the tragedy of Queene Ayla’s death.

Perhaps that ambition would cool a bit in the face of competition, though Cedric doubted it was so.

“I congratulate you both on your good fortune. Rarely have I ever seen so splendid a match.” Bauchan bowed again, and Cedric was certain that the Faery vowed it would be the last time. There was such an air of finality in the gesture that the Ambassador might as well have stamped his feet out of disappointment.

“Then, we are welcome at Queene Danae’s Court?” Cedric motioned to their meager group as a whole.

Bauchan waved a hand. “Of course, you are welcome to join our trooping party. We have very little space, so accommodations will be quite…cramped. And we will be long at sea. Five days, perhaps more, they tell me. But you are lucky, to come to us so close to our departure. The rest of us have been languishing here in the harbor, ready to fly into the hands of the Enforcers by choice.”

Bauchan nodded to the ferryman and pressed something into his hand, but Cedric did not see if it was adequate payment. Guiltily, he did not pursue the issue. They had so little, themselves, that paying the Human seemed a burden. At least he’d gotten something of value for his troubles. Cedric nodded to him as they filed up the walkway.

Bauchan walked ahead of them, and Cerridwen behind him. Cedric noted the way her shoulders hitched as she breathed, the way her feet shuffled, uncertain, on the narrow plank. Two rails fell easily at waist level, and she clung to these as though they alone kept her from plunging into the waters below.

“Easy, now,” Cedric murmured close to her ear. “Stay steady, and you will soon be back on surer footing.”

She blew out a shaking breath and nodded, increasing her pace incrementally.

“You have already had a run-in with Enforcers, then?” Cedric asked Bauchan, tightening his grip on the railings himself as the plank shook from the weight of the guards behind him.

Ahead, Bauchan had nearly reached the opening in the other ship. It was as if the unstable Human contraption did not worry him in the slightest—he had lighted across it as though it were a fallen log on the forest floor.

“No run-ins yet, thank the Gods,” he answered, waiting for them in the muted light from the doorway. “They have been aboard the ship, but we are well concealed, should they raid. A few of the earlier refugees from your Court have not made it, or so we hear, because Enforcers were out on patrol.”

Cerridwen made it to the end of the walkway, and eagerly accepted the arm that Bauchan offered her. Too eagerly, Cedric judged. It was out of fear, he knew, but he wished she would not provide any further fuel for whatever twisted schemes the Ambassador no doubt entertained in his fevered brain.

Once Cedric joined them on the ship, Bauchan relinquished his hold on Cerridwen’s elbow, and smiled at her warmly. “There, no need to fear. Our hosts aboard this vessel care very much about their cargo. They do not undertake a mission from my Queene lightly.”

Cerridwen did not answer him.

“The Royal Heir is very tired,” Cedric said, pulling her close to his side. “Are you not, my…flower?”

She looked up sharply, confusion and anger on her features. Then, as if in defeat, she nodded. “I am. Very tired. Ambassador Bauchan, if you would please show us to our quarters for sleeping—”

“Quarters.” He laughed. “Oh, I wish I could offer you such luxury. We are all bunked in the lowest hold. Though I am certain some arrangement can be made for your privacy and comfort, given your station. I do hope you do not come to us with high expectations for this voyage. It is a meager freight ship, after all.”

“I am sure that she wishes for nothing more than a flat place to lie and a blanket to keep warm.” Cedric chuckled as heartily as he could manage and plucked at the coarse material that covered her shoulders. “And we have half of that already.”

She jerked away and pulled her blanket tighter, as if it were armor. He’d made her angry, that much was obvious, but he did not have the energy, nor the inclination, to soothe her now. Nor was this the proper place, as soothing her would only bring to light a weakness of character in her.

Bauchan led them through a round door a Human would have to stoop to pass, and bade them watch their steps. “These Human vessels are built so strangely. The stairs are steep, and there are constantly barriers underfoot.”

“Give me an old wooden craft any day,” Cedric agreed as they followed him down the narrow ladder, just glad that he wasn’t returning to the depressing concrete surroundings of the Underground.

The lower hold was vast and open, brightly lit, and cluttered here and there with huge steel containers anchored to the ship with heavy straps that bolted to the floor. It was by no means crowded with cargo, but it was crowded with Faeries. Many of them, Cedric recognized from Court, but by their faces only. They no longer looked as fine and self-important as they had when Queene Mabb or Ayla ruled. They wore rugged traveling clothes and crouched protectively over bundles, saying little to anyone but the three or four Faeries who might share the small spaces they had staked out as their own.

He had not seen Faeries behaving so distressingly since he’d stayed on with the Winter Court, long before the Veil had torn. The summertime had always been a time of celebration and plenty, and he’d continued to travel with Mabb’s trooping parade long after the fires of Samhain had extinguished. But with the turning of the year had come a stark, depressing change over most of that Court. They’d become greedy, distrustful hoarders.

As if sensing his thoughts, Bauchan nodded, but he did not comment on the scene. “I know exactly where you will be comfortable,” he declared, striding across the metal floor, his footsteps ringing out as he went. “Back here, this little corner is perfect.”

The space was small, barely long enough to lie down in, but it was protected from prying eyes—and prying ears, hopefully—by two of the large cargo containers and the side of the ship. The guards would have to find another place to rest, ideally not too far from them, but at least it would offer some hope of keeping the Royal Heir safe and away from the betrayers of the Court.

“Here?” Cerridwen sniffed the air and made a face. “It is so dark back here. And close. I do not like close spaces.”

“You skulked about sewage tunnels with your Elf,” Cedric said quietly, near her ear so that only she would hear. “You can deign to sleep here.”

“I will bring you some extra blankets,” Bauchan went on, as though she had never argued. “The crew has been exceedingly generous with their things. They are…sympathetic to our plight.”

“Our plight.” Cedric could not help but scoff at the words. Then, he waved an apologetic hand. “Forgive me, I am tired.”

“Of course.” Bauchan bowed, like a Human fop. “If that will be all, then, I can have your companions settled, as well.”

He would not give them a moment alone to confer. Already, he suspected some plot, saw that the guards were not truly the nobility he had dressed them up as.

One of the guards puffed up his chest and clutched the satchel he’d carried tighter. “I do not wish to seem ungrateful,” he began, in tones that sounded comically similar to Bauchan’s, “but it does not appear as though our—we courtiers—our possessions will be safe among the rabble.”

Cedric spared a glance toward Cerridwen. She stared, mouth agape, at the guard, broken out of her sullen reverie for a moment. It was almost enough to make Cedric laugh.

“You could leave your things with us, then,” he offered, quickly stifling the amusement that he was certain had shown on his face. “We seem to have a most isolated spot, and of course you can trust the Royal Heir.”

The guard played it hesitant; time at Court had afforded him an uncanny ability to imitate the behavior of his “betters.” Finally, with a heavy sigh, he handed over the satchel. “From the looks of things, I would advise you all to do the same,” he said with a courtly flourish as he stepped aside. The others entrusted “their” belongings to Cedric a bit too easily, but Bauchan would not argue. It would not have been Court manners.

“What a generous offer,” the Ambassador said with a smile as sickeningly sweet as spun sugar. “You are truly fit for your role as Royal Consort.”

“Let us hope it should never come to that,” Cedric said with a humble bow.

Bauchan, the rage practically radiating from him, returned the gesture and quickly ushered the guards away.

When Cedric turned to Cerridwen, she had already lain down, the blanket pulled sullenly over her face.

Two

The hold of the ship was cold, and dark, and noisy. Though the lights had been put out an hour before—or so Cerridwen was guessing; time passed so slowly with nothing to occupy it—the rustling and whispering of hundreds of Faery bodies echoed off the steel walls.

Though Bauchan had an underling drop off more blankets, enough to build a respectable nest for themselves on the hard floor, Cerridwen still shivered. The temperature of the sea seeped through the ship’s metal body, up through the layers of blankets that Cedric had arranged for her.

She searched through the darkness, her eyes grateful for the reprieve from the harsh lights of the past few days, to find him. He sat with his back against the huge cargo container that blocked their corner from view, his legs stretched across the slight opening that made an entrance to their makeshift dwelling. He did not sleep, but stared into the darkness, no expression on his face.

She turned her head back to the wall of the ship, examined the crude drips in the white paint that covered every rivet and seam. This place smelled like Humans. Human bodies, Human goods, Human chemicals. It was almost too much to bear, even for one with Human blood in her veins.

She thought of her mother, whom Cedric spoke of as though she could have lived. Had Ayla felt so uncomfortable around mortals? Obviously not, as she had kept one at her side for all those years of Cerridwen’s life.

As if to remind her, the wings at Cerridwen’s back stirred of their own accord. She shifted restlessly on her pallet. Her mother had kept Cerridwen’s parentage a secret, even from her, for most of Cerridwen’s life. When Cerridwen had discovered the truth—that she was not the daughter of the late King Garret, that instead her father was a strange mortal creature from the Darkworld—it had been too late to confront her mother about it. And where was Queene Ayla now? She had believed that the Veil had begun to mend, that the dead moved on to a Summerland kept hidden from the Faeries who had once inhabited the Astral in life. If that were so, where was her guiding hand now? Could she not spare her daughter a sign, something to explain why she had kept such a secret for all of those years? Did she not realize, wherever she had gone, what the revelations of the past days had done to her?

“Are you well, Cerridwen?”

Concern, but from the wrong source. She squeezed her eyes shut against the angry tears that welled there. Cedric had thought it so comical, to keep up the charade of their betrothal. Well, it was a farce, and had been since the moment her mother had sprung it upon both unwilling parties. But he’d also had great fun in pretending that they would bow to this False Queene Danae once they stepped on the shore.

“I am fine,” she said through clenched teeth. Let him leave her alone, then, if he wanted a ball of clay to mold to his liking. She was not so stupid that she would endanger herself, or him. She knew what was at stake. A pretender was about to absorb her mother’s Court, would likely force Cerridwen into some position of servitude to suit her ego. Let her. There was nothing left for her now. Her mother was dead, her father was a mere Darkling, and she had no claim to the crown. No desire for it, either.

“Why did you not introduce me as Queene?” She did not whisper; whispers attracted attention. It was something she learned long ago, a part of daily life in the Palace.

Cedric crossed one leg over the other, shifted as though he could possibly get more comfortable in the position he was in. “I did not, because we do not need to declare our intention for you to rule in Danae’s stead. You will not be safe if we do.”

“You do not trust me to say the right thing, or act the way you wish me to act. You do not trust me to make the right decisions.” Not unfairly, she reminded herself quietly. She had betrayed her mother, and that betrayal had ultimately caused her death. But if Cedric judged her as she judged herself, he would see that she was a selfish creature, and that she would not harm her own interests.

The thought gave her little comfort.

“It is not a matter of trust.” He moved toward her now, settled himself on the pallet beside her, but he did not look her in the eye. “If it were, that would mean that I thought you capable of avoiding the traps certain others might set for you, but you are not.”

“Certain others?” She scoffed. “Bauchan, you mean. You think he is too clever, that I cannot see beyond what he really is?”

“I think that he has much more practice at deceit than you, and is a master of it. Besides, it’s not just a matter of seeing his deceit, but knowing how to react to it, and how to prevent it, too.” The disgust in Cedric’s voice was as chill as the air around them.

Cerridwen burrowed deeper beneath her blankets. “If you had simply told him that I am Queene now, perhaps he would not think to trick me.”

Now, Cedric looked at her, his eyes blazing with anger. “If you believe that, you are far more naive than I could have ever imagined.”

“I would not be so naive if the people around me did not treat me as though I were a child, incapable of understanding!” She lowered her voice. “You do not wish for him to know I plan to be Queene, because you believe that will make me a sweeter plum for Queene Danae. Is that right?”

“It is.” Cedric rolled to his side, propped his head on his hand. “If this Danae gains the support of the Court members that Bauchan brings her from the Underground, we will be on our own. And it looks as though there is enough desperation here for exactly that to happen. We do not know Danae’s temperament. She might be merciful, and allow you to stay on at her Court as a lesser noble, if you pledge your loyalty to her. Or she might chose to view you as a threat, and have you executed.”

It seemed almost absurd to suggest such a thing. “How could I be seen as a threat? I have nothing. I’ve never actually ruled. I have no real power.”

“And that is even more true if you are not the Queene,” Cedric interrupted. “The only Faery you have known well was your mother, and perhaps your governess. But your mother was part mortal, and born in the Underground. The way most Faeries are—the way they were before the Veil was torn—they behave in ugly ways. These Faeries we travel with now will no doubt turn back to their old ways. Danae is probably very much like one of them. We must be certain that she will cause you no harm if you choose to pursue your throne.”

Cerridwen lay on her back, stared up at the ugly ceiling above them. “You were not born in the Underground. You fought beside Queene Mabb during both wars with the Humans. And you are not vain and petty, as you assume this new Queene will be.”

“I am…glad that you do not find me vain and petty.” He stumbled over the words, as though he knew he must acknowledge them, but had no idea why she’d said them. “But we must not trust that Danae will be the same. She keeps company with Bauchan. That does not recommend her character over much.”

It struck Cerridwen then that Cedric spoke to her now not as though he were scolding her, not as though he believed he knew better, but as though she were of equal intelligence and capable of rational thought. As though she were not a child. So rarely did that happen, the feeling was still a novelty. She was but twenty, while Cedric—and most Faeries—were untold hundreds or thousands of years old.

Unbidden, her mind returned her to the night she’d left the Palace, intending to betray her mother’s plans to the Elves. She’d been so besotted with the Elf she’d met on the Strip, she’d followed him into the Darkworld, had pretended to be fully Human just so he would not be repulsed by her. Now, she understood what Faeries meant when they said someone was elf-struck. Sickening.

But that night, before she’d stupidly taken flight from the safety of the Palace walls, Cedric had made good on his promise to tell her all that was discussed in her mother’s private Council. Of course, he had made that promise only to keep her from causing a further scene in the Throne Room, in front of the entire Court. But he had come to her and told her the dire news—that her mother intended to attack the Elves rather than wait for them to unleash the Waterhorses, horrors of the deep that had been summoned to destroy the Faery Kingdom of the Lightworld—and he’d done so without warning her that she did not wish to hear, or that she would not understand.

A pang of homesickness gripped her stomach and stole the breath from her lungs. How she longed to be back in the Palace, in her chambers, in her own, comfortable bed. To feel Governess’s cool hands on her forehead, soothing her to sleep after a bad dream. To know that her mother slept safely down the hall.

That, she missed more than anything, because she had not appreciated it then. She’d hated her mother, had raged at being treated like a child. And though she enjoyed being spoken to as a capable Faery who was full grown, she would have gladly remained a child-princess forever if she could have her mother back.

Only when Cedric asked quietly, “Are you crying?” did Cerridwen realize that she was. She wiped her eyes and shook her head, rolled to face away from him.

This was not a nightmare that she could wake from to find Governess at her bedside, ready to soothe away her fears. “Cerridwen,” Cedric began, but he said no more. He laid a hand on her arm, patted her uncertainly.

She wanted to shrug it away, to isolate herself once again with her misery, for it had always helped in the past. Now, though, she could not stand the thought of being alone with such grief, though it could not be truly shared.

So, she let him keep his hand there but did not acknowledge him, and she cried herself quietly to sleep.

The ship sailed in the early dawn. Exhausted, Cedric had not noticed the sudden churning of the water beneath them, or the subtle feeling of movement. Perhaps it had even soothed him into deeper sleep. He would not complain. Only rest would ease the trials of their flight from the Underground, and all that preceded it.

No, not all. Some wounds would never heal, only seal off with time, waiting to split open and spew forth their pestilence again. He carried several of that kind. The freshest had not yet begun to close, and the pain was constant, even when he thought of other things.

When he’d first boarded the ferry and looked over the side rail into the ocean, he’d imagined the bodies of the Gypsies floating in their watery graves. He’d seen Dika’s face, too, unscarred but ashen blue, her hair floating around her submerged head.

When he’d come aboard the ship and watched the Faeries with their packs, for a moment he’d seen the panicked faces of the Gypsies as they had fled to the center of their camp, ready to leave the Underground entirely. A trip none of them would take.

He wondered if he was as doomed now as they were then, but unable to see it. The entire Kingdom of Queene Ayla was destroyed by Waterhorses from the deep, from beneath the sort of ocean they now traveled upon. And the ship’s hold reminded him of the Underground and the Darkworld…as if an echo that would not end.

He’d woken to find Cerridwen sitting beside him, her knees pulled to her chest, rocking as she stared blankly ahead. She’d looked frightened, but when he’d asked, she’d denied it.

“Sick again, from the motion of the ship,” she’d insisted, though why she would continue to rock, he could not fathom, as it seemed it would only make it worse. But he did not wish to have an argument.

“If you are staying here, I will go and see what other facilities are available for our use.” At first, he’d been uncertain whether or not to leave her, whether or not she was able to defend herself and her possessions, but after only a moment’s consideration, he’d realized that he could not spend the entire voyage in their hiding place. There was no time for her frailty, and perhaps leaving her to fend for herself would shock her out of her incapacitation.

Had Ayla been there, or Malachi, Cedric would have discussed his worries with them. But they were gone now, and he had never truly shared his fears with anyone, not completely. He was not sure which realization hurt him more.

The morning brought more of the same in the lower hold. Faeries, reduced to their primitive, trooping states, regarded Cedric with suspicion and hostility as he walked among them. It took incredible strength not to respond in kind; he did not wish to become like them, but the fear, and the pull to his old nature, were almost too strong. That was what had happened to them, and he did not wish to follow them down that way.

He found the door they had entered through the night before. Now, it was closed, and when he tried the handle, it did not open. A momentary panic gripped him. What if the Humans had lied to Bauchan? What if the ship sailed to some port where Human Enforcers would await them? It took all of his will not to claw at the steel, to calm his mind.

“It is an unsettling thing, is it not?” Bauchan’s voice behind him did nothing to soothe Cedric’s nerves, and he closed his eyes a moment to force away his panic.

“It is.” His voice scraped out, betrayed the turmoil inside him. He took a deep breath. “I had forgotten how very stifling the Underground was, until I stood under the sky again. Now that I am enclosed once more…it is unpleasant.”

He turned to face Bauchan, found the Faery as clean and unrumpled as he had been the night before. He smoothed back a matted rope of hair with one ring-encumbered hand and nodded lazily. “Unpleasant, yes. I fear this entire journey will be one of unpleasantness. But we have endured hardships far greater in our time, have we not?”

“Have we?” Cedric narrowed his eyes as he surveyed the other Faery. Bauchan had never lived in the Underground. His skin was not translucent white from a lack of sunlight, his eyes not dull for want of starlight. He outfitted himself with the trappings of Human luxury, and dared stand before one who had remained faithful to the Fae race and claim hardship.

Almost faithful, Cedric reminded himself, and felt another pang of sorrow at the remembrance of Dika.

Bauchan disregarded his comment—though he reserved his offense for a later time, Cedric was certain—and motioned for the other Faery to walk with him. “The captain of this vessel came to speak with me this morning. He believes that once we have put the harbor behind us, it will be safe for us to leave the hold and go to the upper deck. I have asked him, on your behalf, to provide extra rations at mealtime for the Royal Heir. She did not look well.”

“She is well enough.” The last thing Cedric needed now was to have to protect Cerridwen from Bauchan’s scheming in the guise of kindness. “What can we expect, in terms of rations, though? I do not worry for myself, but for some of these Faeries, who are near feral already. I have been out trooping, and I have seen how it can affect the weaker of our race.”

“You assume they are weak?” Bauchan’s eyes glittered with humor or malice, Cedric was not certain which.

He fixed the Ambassador with a gaze that was not threatening, but could not be misconstrued. “I believe that if they had been stronger of will, they would not have left with you.”

Bauchan took umbrage with this, true feeling finally visible in his expression. But only for a moment. A tight smile that grew a bit more relaxed, a bit more natural with each passing heartbeat, until it was nearly impossible to tell that he’d been angered in the first place, spread across his lips. “You will forgive them their weakness, I hope, now that you have joined them.”

“I have joined them out of duty to my Queene.” He did not wish to argue, but the man drew him into it so easily. The journey would be most interesting, as would its culmination. “I still have my own reservations.”

“Reservations,” Bauchan repeated with a soft laugh. “Yes, I understand. You fear that your mate will be in some danger from my Queene. And I do not begrudge you those fears. If I did not know Danae the way I know her—and that is to say, very well—and I were in your position, I might have the same fears.”

It was a well-rehearsed speech, Cedric credited Bauchan for that. “You can assure me, then, that she will not be a trophy for your Queene? That she will not be viewed as a threat, or that she will not be pressed into slavery in order to appease Danae’s ego?”

“My, but you Underground Fae are a ruthless kind, are you not?” Bauchan laughed through his expression of mock horror. “To have thought of such a thing!”

Cedric smiled with him, but his patience wore thin. “We are not newborn Humans, Bauchan. We are Fae. Born with a capacity for deceit far greater than any other species on Earth or in the Astral. It would be very unwise to forget that.”

“So true,” Bauchan agreed easily. “But then, why should Danae be threatened by the Royal Heir? She does not seek to make an issue of her…title, does she?”

Careful now, Cedric cautioned himself. He’d already given away enough to make Bauchan doubt their intentions, if not suspect the truth outright.

They came to the end of the aisleway, on the opposite side of the ship from where Cedric had left Cerridwen, to another row of shipping containers. A blanket stretched over a gap between two of them, and Bauchan gestured to it. “Come inside. I have nothing to offer to you, but then, you would not take it anyway.”

At least the Ambassador did not think him so thick as to fall for being gifted into service by a few crumbs or a cup of water. He followed Bauchan through the gap. Past the huge cargo containers, a space that spanned the width of the ship opened. Though it was large, it was crowded with all manner of objects so that it was nearly impossible to walk. Cushions, chests, even Human furniture of sofas and chairs, covered all of the floor space, and atop all of these perched Bauchan’s retinue.

“I had wondered where you had hidden them away,” Cedric said, picking his way carefully through the space between an ornamental table and a chest overflowing with silks and jewelry.

“We had much more room on the journey over.” Bauchan waved a hand apologetically. “We like to travel in comfort. You cannot blame us, can you?”

He could blame them for any number of things, but kept silent.

“It is a pity your Queene would not leave the Underground and join us,” Bauchan continued. “She would have had this whole chamber to herself.”

“And her life. But Queene Ayla did not require luxuries. She was a commoner before she took the throne, after the death of her mate, King Garret.” Cedric took care to speak of Cerridwen’s lineage. Though he did not wish to give the impression that Cerridwen would press her claim, there was no reason to let Bauchan forget that Cerridwen was—as far as the Court believed—a descendant of Queene Mabb.

Bauchan nodded. “Yes, Flidais told us the tale of how, exactly, Ayla came to the throne. We were quite enraptured by it, were we not, friends?”

A few murmurs of approval came from the Faeries draped languidly over the furnishings. They appreciated the blood and horror of the tale, nothing more. It sullied what had happened in the Underground, sullied Ayla, if they believed she were anything like them.

“She did what she had to do, in order to save the Kingdom.” A bit dramatic, but the truth. Garret would have turned the Faeries of the Underground into what Bauchan and his fellows—indeed, what Cedric expected all of Danae’s Court to be—had become. They had already been as weak-willed and self-indulgent. The Fae grumbling and desperate in the stronghold were lacking from this retinue in only one regard: access to material wealth. The selfishness was the same.

Bauchan’s eyes widened, as though he had meant no offense, had not meant to trivialize Ayla’s reign as he had. “Oh, and we greatly admire her for it,” he insisted. “Do we not?”

“Do not do that,” Cedric snapped as Bauchan’s companions began to mumble their agreement. “I am not impressed by such displays.”

“Nor would I expect you to be,” Bauchan agreed smoothly. “Not with the experience you have behind you. After all, if Queene Ayla saw fit to entrust you with her daughter, not only as a mate, but to be kept safe in her absence, you must be not only loyal, but highly intelligent.”

Cedric did not know how to respond, so he stayed silent while Bauchan made a show of pacing the small bit of cleared floor he occupied.

“But I wonder at how loyal you are to her,” Bauchan continued. “Was there no command from her that you should…Excuse me, I do not wish to pry into affairs that do not concern me.”

Cedric could not help his laughter at that. “Why would that concern you now, after you have meddled so thoroughly?”

Bauchan ignored him. “Ah, but I must know. Why did the Queene not charge you with returning some of her subjects? Surely, she wanted to see the Lightworld Court flourish even after her death?”

“My Queene had but one mission, the one entrusted to her by the Gods.” Cedric chose his words carefully, wanted no misunderstanding.

“But it would be so easy,” Bauchan pressed on. “Our journey had not even begun and they were discontent. It would have been no trick to lure them back to the Underground.”

“I did not come here to upset your plans, nor the plans of your Queene,” Cedric stated firmly. “Nor do I care what her plans might be, so long as Cerridwen will not be harmed by them. With all the troubles that plagued my Queene and the Faeries of the Underground, I do not believe the destruction of the Lightworld to be any great loss. I only wish it could have come without the expense of ones I cared for deeply.”

Bauchan nodded. “To hear you say such a thing brings me great relief. I must admit, I feared some trickery on your part, especially when Flidais did not return. But knowing that you speak earnestly, I no longer fear your presence, or what actions I might have had to take to prevent you from harming my Queene.”

Cedric hoped that this would be the end of the conversation, even turned to go, but Bauchan’s voice stopped him. “And please, be sure to impress upon the Royal Heir that I am her servant on this journey, and upon our arrival at Queene Danae’s Court. I do not wish her to feel…friendless there.”

“She will not be friendless,” Cedric assured him, hoping that the icy weight of threat he pressed into his words would not be lost on the Ambassador. “I will be at her side every moment. I am, perhaps, the greatest ally and protector she has at this time.”

Three

In most ways, the days on the ship were long and more dull than any Palace banquet had ever been. Still, the first day at sea had lifted some of the fog of sorrow from Cerridwen’s mind. It had helped, strangely enough, that the other Faeries had eagerly abandoned the hold and went above when given the signal that it was safe to do so. Many of them had taken their possessions and set up camp under the sky, leaving the hold less crowded. It had been a strange feeling, after so many years at Court, to be left alone, and it was a good feeling, as well.

Cedric had asked her to accompany him up to the deck a few times. He spent his days at the edge of the upper deck, staring down into the water, the same grim expression on his face. A few times, something had broken the spell the waves seemed to have over him, and he’d asked Cerridwen to walk with him, to keep up appearances, she supposed.

But he’d sworn only to protect her, not to keep her entertained, so she did not approach him during his times of deep melancholy. On those rare moments when he’d sought out her company, they’d found little to talk about, anyway. She did not wish to discuss what had happened, and it would not have been wise to, but they did not know much of each other beyond the horrible times of the past weeks. She was most glad for the nights, when they would sleep, or at least pretend to, so that she did not have to think of things to say to him.

There was no doubt in her mind that Cedric would keep her best interests in mind as they embarked on this strange journey. But whether out of concern for her, or out of obligation to the promise he had made her mother was a mystery in itself.

She wondered why it mattered. It should not. But he had kept her safe when Malachi had fallen in the Elven fortress, and during their flight from the Darkworld. He had not coddled her—in fact, he’d been angry—but he had truly seemed to care whether she lived or died.

More than that, he had treated her with respect when the rest of the Court had discounted her as pretty decoration.

Perhaps he had not lost that respect for her, if he did blame her for her mother’s death. He had loved her mother as a close friend, and Malachi, as well. That was more than Cerridwen could ever hope anyone would feel toward her, now that she knew herself to be a selfish, reckless creature. But she hoped that Cedric cared enough that he did not view her as a burden, and that he would not continue to feel obligated to her when they arrived at the Upworld settlement. If he returned to the Underground, if that were even a possibility, perhaps she would not have disrupted his life irreparably. If he stayed in the Upworld settlement, he might find a mate there and be happy. But he should not feel indebted to her, and to her mother, forever.

It had occurred to her that morning, when the movement of the ship had woken her, that she could be embarking not only on a journey to a new home, but to a new life altogether. If the events of the past few days had not unfolded as they had, she would still be in the Underground, living out her days there. Mated to Cedric, if she’d bent to her mother’s wishes, or living in the Darkworld with her Elf, Fenrick, had he not turned out to be a spy against the Fae.

Now, though, the future was not so sacrosanct. It frightened her, but it was not nearly so frightening as knowing that her life had been decided for her. Though her heart was still wounded from Fenrick’s betrayal, she wondered at the type of Faeries who made up Danae’s Court. If they were as handsome as Bauchan, surely she would find someone she did not find objectionable.

She wondered, too, what role she would have in this other Queene’s Court. Whereas before she had been hidden away and taken out only for special occasions during which she was meant to be seen and not heard, she was a Queene now. Or, she would be, if she had her way. If they failed, though, and this Danae let her live, she might be just like any normal Faery. That promised a sort of freedom, and freedom held for her giddy fascination and terrible fear.

No matter what might happen, she knew that she would always be haunted by what she had seen in the Underground. Not just the horrible violence of her last few days there. She would never forget the sickening rush of exhilaration she’d felt at the sight of battle, or her sorrow at watching her parents cut down before her; those images would force themselves into her mind every time she closed her eyes, and chase away any happy thought she might begin to feel, she was certain. But she would always remember the awfulness of the lives lived by the creatures there, the scrabbling for sustenance, the very real possibility that something could come out of any one of the shadows and end the life they struggled to lead.

She would not live in such a way, nor would she allow anyone she cared about to, if she could help it.

If the days were interminable, the nights were only slightly less so. But the evenings, they were nearly pleasant. Once the sun set, a change would come over the Fae. Probably relief. Cerridwen felt this every day that passed. The setting sun showed them that they were one day closer to their destination, that soon they would be quit of the ship and one another, free to seek out new companionship in the Upworld settlement. Free to set up new lives not encircled by walls.

A few of the Faeries had brought instruments in their flight from the Underground, drums and whistles and pipes, and a harp. They assembled on the deck, under the night sky dazzled with stars, and played until the dawn lit the sky. Sometimes, the Human sailors would come and watch them, but always from a safe distance, always wary.

Cerridwen watched, as well, because she was not fool enough to think that she could truly be a part of it. But being near the others was enough to make her feel less lonely, and so she watched them celebrate their journey’s progress.

On the fifth night, Bauchan approached her, practiced smile in place. “And where is your mate? I have not seen him any night yet, when everyone else is here.”

She would not let him goad her into giving anything away, not even her unhappiness. “He is tired,” she said with a shrug. “And he does not care for parties.”

“Too tired to dance with his lovely betrothed?”

Bauchan clucked in disapproval.

“Too tired for disrespectful celebration in the wake of terrible tragedy,” she replied coolly.

The humor fled Bauchan’s face, and his eyes glittered like those of the great, sleek sea creatures that bumped and brushed against the hull of the boat as they slept at night. “Tragedy, yes. The death of your mother, the Queene.”

“And countless others, and the destruction of our way of life.” She held his gaze, hoped he would see something of her mother in her.

“But no such a tragedy for yourself? You will be Queene, after all.”

Be cautious, she warned herself, but her anger was far stronger than her restraint. “Not all of the Fae in the Underground have survived,” she snapped. “Many of them died at the hands of the Elves and Waterhorses because they would not turn their back on their true Queene.”

She had said too much, but she did not care. Her hands trembled, her chest jerked with her angry pulse.

“I have upset you.” He tried another harmless smile. “It seems I cannot say the right thing when I am near you.”

“I am sure it is not just me.” She would give him no foothold. “Why does anyone fall for your obvious manipulations?”

Hatred, she had learned long ago, looked especially ugly on a beautiful face. Bauchan was more beautiful than most, so on him the effect was terrifying. “You should watch your step, little one. I may have underestimated you, but I know exactly the kind of creature your Cedric is. I can turn him from you in a moment.”

She laughed at the absurdity of his arrogance. No power on Earth, the Upworld or the Underground, could make Cedric betray the last promise he’d made to her mother.

“You do not believe me?” Bauchan’s voice was as cold and deadly as a blade. “I turned Flidais, ever faithful Flidais, from your mother.”

“I would be careful if I were you,” she warned.

“What will you do to me?” Bauchan had the nerve to laugh at her. The fool. “You have no allies. No real power. If you do intend to overthrow my Queene, and I suspect you do, you have no army and no Court.”

“I do not need an army! I can easily do what I did to Flidais, to you and anyone else who stands in my way!”

The music stopped; the dancing followed.

They could not have all heard. Soon, she knew, a ripple of whisper would begin, growing and spreading until their outraged voices would be louder than the instrument had been.

Bauchan looked so pleased with himself, she wished she really could do to him what she’d done to Flidais. The red haze of her anger was so similar to what she’d felt in the battle in the Elven Great Hall. A family trait, she thought with pride. Her mother had been a skilled assassin. Her father—her true father—a great warrior. She did not falter under the accusing stares.

Bauchan called for quiet, and the crowd fell silent. He stalked forward, so close that if she’d had a knife, she could have easily sent him the way of that treacherous Fae.

“And what did you do to Flidais?”

It was too late now to keep from telling everything. And that must have been his plan all along. To push her to this. He was, indeed, very good at this sort of trickery.

Still, she would not let him see that he had beaten her. “I killed the traitor Flidais. Before we boarded the ferry, I killed her with a dagger in her throat, and I have not thought twice about it since!”

A gasp went up, and she turned to address the Faeries that had formed a circle around them. “I dealt with Flidais the way we should deal with all cowards and traitors. She lied to you, working with Bauchan to deliver you as playthings to his Queene. You would not be here, on this boat, bound for an unknown future, if she had not promised this man something in exchange for your presence!”

Bauchan smirked at Cerridwen and looked around. “You would not be free of the oppression of your Queene, who would not let you decide for yourself whether or not you wished to stay buried underground,” Bauchan countered. “Give up this foolish argument, little one. I have won, my Queene has won. You no longer have a Court to support you, Your Majesty.”

“Bauchan! What is the meaning of this?”

Cedric appeared out of the air, it seemed, and stalked through the crowd of Faeries around them. He did not look at her, did not divert his focus from Bauchan.

She’d seen him look this way before, when he’d stood, blood-drenched in the thick of battle. He was no less terrifying now. He stood between Bauchan and Cerridwen, so that she could not see his face, but the tone of his voice told her that she would not want to see it, anyway.

“Step away from my mate,” he growled.

Four

Cedric had been nearly asleep when the guard had burst through the blanket that partitioned off their sleeping quarters. It was difficult, he found, to sleep with another body beside his. Twice now, he’d woken to find that he’d put his arm around Cerridwen as she slept, had dreamed she was Dika lying asleep in his arms.

He was not sure which was more acute, his embarrassment with himself at touching her so intimately, or his pain when he woke and remembered that it was not, could never be, Dika. He was relieved when Cerridwen had begun to linger with the Faeries on the deck, so that he could steal a few hours of rest without fear of frightening her.

Or worse, leading her to believe something that would never be.

He squinted at the intruder through sleep-bleary eyes. “What is it? What’s happened?”

“You should come above. Immediately.” The guard’s tone and expression were enough to jolt Cedric fully awake. In an instant, he was on his feet, pushing past the guard.

He did not ask what he would find above deck. Bauchan would be involved, he had no doubt. They passed no one on their way, so there was nothing to flee from. It gave him no clue to what he might find. Had Cerridwen fallen overboard? Had she made some pact with Bauchan? He did not wish to know; at least, not before he had to. So, he did not ask.

But he had not expected to see the scene on the deck of the ship, a ring of Faeries crowded around the two that he had already known would be involved.

“Bauchan!” he shouted, and it was enough to draw the attention of the Faeries away from Cerridwen’s words. He shoved one last Faery from his path and strode into the center of the circle. “What is the meaning of this?”

At the sight of him, Cerridwen began to tremble. If it was from her anger, then he could top it. If it was out of fear of him, then she was wise. She’d revealed too much, and come far too close to disaster, even after his warnings. The very sight of her sparked an intense desire to wrap his hands around her throat and choke the life from her. He turned his back to her as he stepped between her and Bauchan, and directed all of that rage toward his real enemy. “Step away from my mate.”

Bauchan smirked and made a mocking bow. “Of course, Your Majesty.”

A twitter of nervous laughter rippled through the crowd. Cedric turned to address them directly. “You laugh, yet you do not accept that you have been led to this place by a trickster, a jester? You abandoned your Queene, who fought to protect you, in order to follow this wretch?”

“What Queene did they abandon?” Bauchan laughed. “Your Ayla was a half-breed, a half-Human, with no more right to the throne than you, or any of these Fae.”

“Queene Ayla carried the Royal Heir, who stands before you now as Queene, descended from the line of Mabb. What right does your Danae have to call herself Queene?”

“Her Majesty Queene Danae has never lost a battle against the Humans. She has never allowed herself to be forced underground. What good is a bloodline if it stems from a source as powerless as your Mabb?” Bauchan smirked and turned toward the crowd. “You were not coerced. You made a choice. And Queene Danae will reward you for it!”

As the Faeries mindlessly clapped and cheered, Cedric spared a glance at Cerridwen. She did not look queenly. She looked like a terrified child, with her head bowed and shoulders sagging as she hugged herself and trembled.

The desire to throttle her faded somewhat, replaced by the instinct to comfort her. But that would not help her. Silently, he willed her to look more dignified, to revive her anger, if that was what she must do in order to appear less weak.

If she would not fight back, he would have to. “How will they be rewarded, Bauchan? With the privilege of bowing to your Queene’s vanity? You promised you would deliver them from the threat of the Waterhorses, and you’ve done that. But you’ve not made any of your other intentions clear to them.”

“They will be rewarded by living at a Court where the Queene does not permit lawlessness, and does not indulge in it herself.” Bauchan leveled a finger at Cerridwen. “And she will not excuse traitors like this one. She will pay for the death of Flidais, who only sought to protect innocent Faery lives.”

This brought Cerridwen to life, animated her with pure hate. “Your Queene has no authority over me! I name you traitor, and if you turn your back on me, even for a moment, I will carry out my own sentence upon you!”

“Cerridwen!” Their position was too precarious here. He wanted her to display some courage, but not foolish bravery. They were surrounded by an easily swayed crowd, who would think nothing of tossing them overboard—and who knew how long their wings would hold them above the endless ocean, if Bauchan let them? Bauchan wanted to see them humbled at his Queene’s feet, and a reward for himself—but Cedric could not let this continue.

She snapped her head to face him, the rage in her eyes flaring to new intensity. Her mouth opened, to issue a challenge, no doubt, but she thought better of it.

Good. She had no one else, and she should tread cautiously with him, as well. Especially now, after what she had done. She may have ended the royal lineage of Mabb—and her own life—with her actions. One an ancient dynasty, the other barely beginning to sprout.

He took her by the arm, aware that by humbling her in this way, he contested her authority and damaged her in the opinion of the Court. But the Court was a shambles now, and any real chance of ruling had died with her mother. Now, he merely sought to save her life.

“She has threatened me. They all heard it,” Bauchan shouted, finally losing his infuriating calm as Cedric pulled Cerridwen through the throng. “You cannot simply leave!”