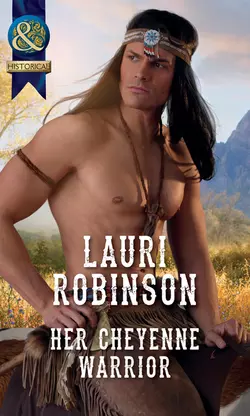

Her Cheyenne Warrior

Her Cheyenne Warrior

Lauri Robinson

The Cheyenne’s captive!Runaway heiress Lorna Bradford must reach California to claim her fortune—but when she’s rescued from robbers by fierce native warrior Black Horse, she’s forced to remain under his protection.Immersed in a world so different from her own, wildcat Lorna learns how to be the kind of strong woman Black Horse needs. But to stay by his side she must first let go of everything she knows…and decide to seize this chance for happiness with her Cheyenne warrior!

“Where is it?” she shouted. “I need it so no man can get within three feet of me. No man. Including you!”

He took a step closer.

“Don’t!” she shouted, backing up. “Don’t come any nearer.”

Being filled with fear was more dangerous than being filled with anger. That went for people as well as animals. Black Horse held his arms out to his sides as he would while approaching a cornered horse. “No one will hurt you, Poeso,” he said quietly.

“I know they won’t,” she shouted. “I won’t let them! I won’t let anyone hurt me ever again!”

The way she shook entered his heart, made it pound with an unknown anger. She had been mistreated, badly, at some time, someplace. “I won’t let them either,” he whispered.

“I won’t let you hurt me.”

“I will not hurt you,” he said. “I will protect you. I will stop all others.”

Author Note (#u93838129-679b-5093-a0af-7fbd0f891812)

Black Horse and Lorna’s story came to me as an image of a young woman stripped down to her underclothes, standing in the middle of a river surrounded by Cheyenne warriors. At the time I was in the midst of writing Saving Marina, and didn’t have the time to fully embrace a new story. But I found a few novels about the Cheyenne.

Most writers—I’m assuming—are also avid readers, and years ago I formed the habit of reading every night. Sometimes it’s just a chapter or two—other times I’ll stay up half the night to finish a book that I just can’t put down. Therefore, even after spending hours writing about the Salem Witch Trials, when I went to bed I’d read about the peaceful Northern Cheyenne.

I must say those two cultures merging as I fell into sleep produced some peculiar dreams!

Such is the inner world of a writer. Our imaginations just don’t know how to rest!

I sincerely hope you enjoy spending some time in Wyoming as Lorna discovers Black Horse is, indeed, Her Cheyenne Warrior.

Her Cheyenne Warrior

Lauri Robinson

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

A lover of fairytales and cowboy boots, LAURI ROBINSON can’t imagine a better profession than penning happily-ever-after stories about men—and women—who pull on a pair of boots before riding off into the sunset … or kick them off for other reasons. Lauri and her husband raised three sons in their rural Minnesota home, and are now getting their just rewards by spoiling their grandchildren. Visit: laurirobinson.blogspot.com (http://laurirobinson.blogspot.com), Facebook.com/lauri.robinson1 (http://Facebook.com/lauri.robinson1), or Twitter.com/LauriR (http://Twitter.com/LauriR).

To my brother Jeff.

Finally.

Love you.

Contents

Cover (#u9e332bab-0310-544c-92f4-16a9fe8584c9)

Introduction (#u936df90c-2792-5216-b21f-2fca8d492b1a)

Author Note

Title Page (#udf7e2914-f54e-5817-9cec-114fc0134828)

About the Author (#ube1d0dc3-922d-5008-82a8-eb8f49f3f858)

Dedication (#u83e68b86-06ec-5ffa-a2db-be8ca62b37d3)

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Epilogue

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#u93838129-679b-5093-a0af-7fbd0f891812)

January 1864, Land of the Northern Cheyenne

The gathering brought leaders from bands near and far, despite the snow-covered grounds and days of short light. For some the journey had been long and difficult, but the attacks against many tribes on land to the south and east had required the tribal council to join together. The harmony and peace that the Tsitsistas—The People—sought and held in high regard was once again being challenged. Not just by the white men, but by younger members of the bands.

Black Horse listened with intent as both the elder and the younger chiefs spoke of conflicts with the white men, of sweeping illnesses and attacks that affected not only the Cheyenne, but threatened bands of all the Nations. Chosen by members of this council eight years ago to be the leader of The Horse Band, Black Horse was known for his slow-to-rise temper. He did not rile easy, but when he did, he was a fierce warrior whom few dared oppose, which meant that his opinions were respected and sought after. But on this day he could not deny the shift in attitudes of many of the leaders. Several Great Chiefs, those of the older generation, were absent; they had departed this earth, some killed in attacks, others dead from the white man’s illnesses. The younger generation that had replaced them were not following the traditional path of advocating for peace.

Several of the these leaders wore war shirts made of deerskin and decorated with hammered silver coins taken from white men, and they demanded revenge with a ferocity more in line with the Southern Cheyenne than the northern bands. Black Horse was of the younger generation but he was not a new leader, and his values had been learned from those who had come before him. His heart and soul and his vision had been challenged by the white man, and at times still weighed heavy inside him, despite his commitment to peace.

While the smoking pipe was passed around the circle, he listened through the long hours of arguments and suggestions. Although he could understand the anger and frustration of those demanding more direct action, his overall view remained unaltered. Believing that the best plan for prosperity was to remain steadfast to the way of life The People had always known, Black Horse chose his words wisely.

“Tsitsistas,” he started slowly, while nodding to include each leader sitting around the large circle, “are of small number because we know that Mother Earth can only host so many of her children. Just as the grass can only feed a specific number of buffalo, elk and deer. If there are too many of any one kind, some will starve, die, until Mother Earth can rebalance the numbers again. We do not know this number, only Mother Earth has this knowledge, but Tsitsistas should remain small in number so all can eat rather than see some starve.”

“Too many Tsitsistas have died,” Otter Hair argued. “The white man’s sickness and the battles they rage have made our number even smaller. Soon we will disappear. This is the white man’s wish, and we must stop them before none are left.”

There were times when looking another directly in the eye was considered bad manners, but not when disciplining. Black Horse leveled a glare upon Otter Hair—named for the strips of otter fur braided into his hair—until the other leader dipped his chin, acknowledging that Black Horse had not given permission for another to speak. He would not rise to anger during a tribal council, but neither would he tolerate misbehavior. To interrupt another was always bad manners and never allowed.

He held silent long enough for all to understand his displeasure with Otter Hair before saying, “The death of every Cheyenne, of every brother, every sister, is felt across our land, but we cannot let the pain cloud our vision. It is our duty, that of each chief in this council, to see Tsitsistas survive. To assure every member of our band is fed and taken care of, and to assure the next generation has much land with plentiful food. This cannot happen when all we discuss is battles with the white man. We must talk of the hunting season and health of our people. The white man is not our concern.”

He paused in order to draw on the pipe that had once again reached him and let others consider the truth behind his words. He also used the time to attempt to settle the stirring inside him. It was difficult to strive for peace while a sense of injustice infiltrated Cheyenne land. Inside, where he tried not to look, he saw changes and knew that more were coming. He also knew that Maheo—The Great Creator—would show him what must be done when the time was right.

Passing the pipe to Silver Bear, Black Horse added, “The white men continue to fight each other where the sun rises. They do not care about future generations and will kill many of their own kind without help from Tsitsistas. When their war is over, the Apache, the Comanche and our southern brothers who decorate their clothes and horses with the scalps of white men will attack the survivors. We will council again then, if our help is needed.”

Chapter One (#u93838129-679b-5093-a0af-7fbd0f891812)

July 1864, Nebraska Territory

If a year ago someone had told her she’d be a part of a misfit band of women, wearing the same ugly black dress every day, and have calluses—yes, calluses—on her hands, she’d have laughed in their face. Then again, a year ago she’d had no reason to believe her birthday would be any different than the nineteen previous ones had been, complete with a party where friends plied her with frivolous gifts of stationery, silly doodads and fans made of colorful ostrich feathers.

Lorna Bradford lifted her stubby pencil off the page of her tattered diary where she’d written Tomorrow is my birthday, and questioned scribbling out the words. It wasn’t as if there would be a celebration, and she certainly didn’t need a reminder of what had happened last year. That night was the catalyst that had brought her here, to a land and a way of life that was entirely foreign to her. But somehow, though she had once been a stranger to it, she had begun to grow used to this life, this land, and to feel at home, as amazing as that seemed.

Wearing the same dress day after day didn’t faze her as much as it once would have; and the calluses on her hands meant she no longer needed to doctor the blisters she’d suffered from during the first few weeks holding the reins of the mules.

Nibbling on the flat end of the pencil, Lorna scanned the campsite she and the others had created for the night. Stars were already starting to appear. Soon it would be too dark to write in her diary. Maybe that was just as well. She had nothing to add. It had been an uneventful day. God willing, tomorrow would be no different.

Lorna pulled the pencil away from her lips and twirled it between her thumb and fingers. She made a note of some sort every night, and felt compelled to do so again. Perhaps because it was habit or maybe because it marked that she’d lived through another day. Despite the past. Despite the odds. Despite the obstacles.

In fact, her notations were proof they were all still alive, and that in itself said something. The four of them might be misfits in some senses of the word, but they were resilient and determined.

Meg O’Brien was most definitely determined. She was over near the fire, brushing her long black hair. Something she did every night. The care she gave her hair seemed odd considering it was covered all day and night by the heavy nun’s habit. Then again, the nun’s outfits had been Meg’s idea, and the disguises had worked for the most part. Soon Meg would plait her hair into a single braid and cover it with the black cloth, a sign her musing was over for the evening. Though boisterous and opinionated, Meg sat by herself for a spell each night. Lorna wondered what Meg thought about when she sat there, brushing her hair and staring into the fire, but never asked. Just as Meg never asked what Lorna wrote about in her diary each night.

Lorna figured Meg had a lot of secrets she didn’t want anyone to know about, and could accept that. After all, they all had secrets. Her own were the reason she was in the middle of Nebraska with this misfit band.

She and Meg had met in Missouri, when Meg had answered Lorna’s advertisement seeking passage on a wagon train. The railroad didn’t go all the way to California. A stagecoach had been her original plan, but the exorbitant cost of traveling on a stage all the way to California was well beyond her financial resources, thus joining a wagon train had become her only choice. When she’d answered the knock on her hotel room door, Meg had barreled into the room asking, “You trying to get yourself killed?”

Lorna had pulled her advertisement right after Meg had explained that wagon trains heading west had slowed considerably since the country was at war and that Lorna would not want to be associated with the ones who would respond to her advertisement. Meg had been right, and Lorna would be forever grateful to her. They’d formed a fast friendship that very first meeting, even though they had absolutely nothing in common.

The clink and clatter coming from inside the wagon, against which Lorna was leaning, said Betty Wren was still fluttering about, rearranging the pots and pans they’d used for the evening meal. Betty liked things neat and orderly and knew at any given moment precisely where every last item of their meager possessions and supplies was located. Too bad she hadn’t known where that nest of ground bees had been. Perhaps then her husband, Christopher, wouldn’t have stepped on it.

The wagon train had only been a week out of Missouri, and Christopher had been their first fatality. He’d died within an hour of stepping on that bee’s nest. Others had been stung as well, but none like him. Lorna had never seen a body swell like Christopher’s had. A truly unidentifiable corpse had been buried in that grave. She’d never seen a woman more brokenhearted than Betty, either, and was glad that Betty only cried occasionally these days.

Betty’s heart was healing.

They eventually did. Hearts, that was. They healed. Whether a person wanted them to or not. Even hate faded. That was something she hadn’t known a year ago. A tightening in Lorna’s chest had her glancing back down at the notation in her diary. The desire for retribution, she had discovered, grew stronger with each day that passed.

“Can’t think of anything to write about?”

That was the final member of their group speaking, Tillie Smith. She, too, had lost her husband shortly after the trip started, while crossing a river. The water wasn’t deep, but Adam Smith had been trapped beneath the back wheel of his wagon, and it was too late by the time the others had got the wagon off him. Trapped on his back, he’d drowned in less than two feet of water. It had been a terrifying and tragic event.

“I guess not,” Lorna answered, shifting to look at Tillie, who was under the wagon and wrapped in a blanket. More to keep the bugs from biting than for warmth. The heat of the days barely eased when the sun went down, but the bugs came out, and they were always hungry. How they managed to bite through the heavy black material of the nun outfits was astonishing.

“You could write that I say I’m sorry,” Tillie said.

“I will not,” Lorna insisted. “You have nothing to be sorry about.”

Tillie wiggled her small frame from under the wagon, pulling the blanket behind her. Once sitting next to Lorna with her back against the same wheel, she wrapped the blanket around her shoulders. “Yes, I do. If not for me, the rest of you would still be with the wagon train. You should have left me behind.”

Lorna set her pencil in her diary, and closed the book. After the death of her husband, pregnant Tillie had started to hemorrhage. The doctor traveling on the train—a disgusting little man who never washed his hands—said nothing could be done for her. In great disagreement, Lorna and Meg, as well as Betty, who’d latched on to her and Meg for protection as well as friendship by that time, had chosen to take matters into their own hands. The small town they’d found and the doctor there had tried, but Tillie had lost her baby a week later. It had taken another three weeks—since Tillie had almost died, too—before the doctor had declared she could travel again. The wagon train had long since left without them, so only the four women and their two wagons remained. That was also why she and Meg only had one dress each. They’d started the trip with two each, but had given the extra dresses and habits to Betty and Tillie. Four nuns traveling alone were safer than four single women. That was what Meg had said and they all believed she was right.

“Leaving you behind was never an option,” Lorna said. “And we are all better off being separated from the train. They were nothing more than army deserters and leeches. There wasn’t a man on that train I trusted, and very few women.”

“You got that right,” Meg said, joining her and Tillie on the ground.

“Furthermore,” Betty said, sticking her head out the back of the wagon, “taking you to see Dr. Wayne was our chance to escape.”

Lorna turned to Meg, and they read each other’s minds. Neither of them would have guessed that little Betty, heartbroken and quieter than a rabbit, had known of the dangers staying with the wagon train would have brought. Lorna and Meg had, and had been seeking an excuse to leave the group before Tillie had lost her husband and become ill.

Betty climbed out of the wagon and sat down with the rest of them. “I wasn’t able to sleep at night with the way Jacob Lerber leered at me during the day. Me! With Christopher barely cold in his grave.”

The contempt in Betty’s voice caused Lorna and Meg to share another knowing glance. Jacob Lerber had done more than leer. Both of them had stopped him from following Betty too closely on more than one occasion when she’d gone for water or firewood. Gratitude for the nun’s outfits had begun long before then. Everyone had been a bit wary of her and Meg, and kept their distance, afraid of being sent to hell and damnation on the spot. When Tillie had become ill, no one had protested against two nuns taking her to find a doctor. In fact, most of the others on the train had appeared happy at the prospect.

“But,” Tillie said softly, “because of me, we might not get to California before winter. It’s midsummer and we aren’t even to Wyoming yet.” Glancing toward Meg, Tillie added, “Are we?”

Meg shook her head. “But I’ve been thinking about that. There are plenty of towns along the way. I say wherever we are come October, we find a town and spend the winter. It would be good if we made it as far as Fort Hall, but there are other places. Having pooled our supplies, we have more than enough to see us through and come spring, we can head out again.”

Betty and Tillie readily agreed. Meg had become their wagon master, and they all trusted her judgment. None of them had anyone waiting at the other end, and whether they arrived this year or next made no difference.

To them. To Lorna it did. She needed to arrive in San Francisco as soon as possible. That was why she was on this trip, but she hadn’t told anyone else that. Not her reasons for going to California nor what she would do once she arrived and found Elliot Chadwick. That was the first thing she’d do. Right after getting rid of the nun’s habit. However, she also wanted to arrive in California alive. Others on their original train had told terrifying stories about being caught up in the mountains come winter, and claimed they couldn’t wait for Tillie to get the doctoring she’d needed.

Meg’s plan of wintering in a small town, although it made sense, wasn’t what Lorna wanted to hear. She didn’t want to pass the winter in any of the towns between here and California. The few they’d come across since leaving Missouri were not what she’d call towns. Then again, having lived in London most of her life, few cities in America were what she’d been used to, not even New York, despite having been born there.

“Lorna, you haven’t said anything,” Meg pointed out. “Do you agree?”

Meg might have become their wagon master, but for some unknown reason, they all acted as if Lorna was the leader of their small troupe. “Yes,” Lorna answered, figuring she’d hold her real opinion until there was something she could do about it. “Wherever we are come October, that’s where we stay.” She turned to Tillie. “And no more talk of being sorry. We are all here by choice.” Holding one hand out, palm down, she asked, “Right?”

One by one they slapped their hands atop hers. “Right!” Together they all said, “One for all and all for one.”

As their hands separated, Lorna reached for the diary that had tumbled off her lap. Too late she realized the others had read the brief entry she’d written for the day.

The women looked at one another and the silence thickened as Lorna closed the book.

Tillie picked up the pencil and while handing it back said, “How old will you be tomorrow?”

Lorna took the pencil and set it and the book on the ground. “Twenty.”

“I’m eighteen,” Betty said. “Had my birthday last March, right before we left Missouri.”

“Me, too,” Tillie said. “I’m eighteen. My birthday is in January.”

The others looked at Meg. She sighed and spit out a stem of grass she’d been chewing on. “Twenty. December.”

Betty turned to Lorna, her big eyes sparkling. “I have all the fixings. If we stop early enough tomorrow, I could bake a cake in my Dutch oven.”

Lorna shook her head. “No reason to waste supplies on a cake...or the time.”

Silence settled again, until Tillie asked, “Did you have cake back in England? Or birthday parties?”

Lorna considered not answering, but, ultimately, these were her friends, the only ones she had now. Meg didn’t, but Betty and Tillie, the way their eyes sparkled, acted as if living in England made her some kind of special person. No country did that.

“Yes,” she said. “My mother loved big, lavish parties, with all sorts of food and desserts, and fancy dresses.”

“What was your dress like last year?” Betty asked, folding her hands beneath her chin. Surrounded by the black nun’s habit, the excited glow of her face was prominent.

Lorna held in a sigh. She’d rather not remember that night, but couldn’t help but give the others a hint of the society they longed to hear about. “It was made of lovely dark blue velvet and took the seamstress a month to sew.”

“A month?”

She nodded. “My mother insisted it be covered with white lace, rows and rows of it.”

“You didn’t like the lace,” Meg said, as intuitive as ever.

Lorna shrugged. “I thought it was prettier without it.”

“I bet it was beautiful,” Betty said wistfully. “How many guests were there?”

“Over a hundred.”

Tillie gasped. “A hundred! Goodness.”

Lorna leaned back against the wagon wheel and took a moment to look at each woman. In the short time she’d known them, they had become better friends than anyone she’d known most of her life. Perhaps it was time for her to share a bit of her story. “It was also my engagement party. I was to marry Andrew Wainwright. The announcement was to be made that night.”

While the other two gasped, Meg asked, “What happened?”

“Andrew never arrived,” Lorna answered as bitterness coated her tongue. “Unbeknownst to me, he’d been sent to Scotland that morning.”

“Sent to Scotland? By whom?” Betty asked.

“His father,” Lorna said, trying to hold back the animosity. It was impossible, and before she could stop herself, she added, “And my stepfather.”

“Why?”

Night was settling in around them, and inside, Lorna was turning dark and cold. She hated that feeling. Her fingernails dug into her palm as she said, “Because my stepfather, Viscount Douglas Vermeer...” Simply saying his name made her wish she was already in California. “Didn’t want me marrying Andrew.” Or anyone else, apparently. Since he’d made certain later that night that it would never happen.

“Why not?” Tillie asked.

At the same time, Betty asked, “Oh, how sad. Did you love Andrew dearly?”

As astute as ever, Meg jumped to her feet. “Lorna will have to finish her tale another night. It’s late, and morning comes early.” She then started giving out orders as to what needed to be done before they crawled beneath the wagons.

No one argued, and a short time later, Lorna and Meg were under one wagon, Betty and Tillie under the other. Meg didn’t utter another word, and neither did Lorna. There was nothing to say. She’d never told Meg what had happened that night back in London. She didn’t have to; her friend seemed to know it was something she didn’t want to remember. To talk about. Just like a hundred other things Meg seemed to know.

Lorna shut her mind off, something she’d learned how to do years ago, and closed her eyes, knowing her body was tired enough she’d fall asleep. That was one good thing about this trip. It was exhausting.

* * *

The next morning, when the early-dawn sunlight awoke them, they all crawled out from beneath the wagons. No one complained of being tired or of sore muscles as they began their work of the day. Breakfast consisted of tea and the biscuits Betty had made the night before along with tough pieces of bacon. Betty insisted they have meat—bacon that was—once a day. She’d save the grease and make gravy out of it tonight, as she did every day. A year ago, Lorna would have quivered at such meals. Now she simply accepted them, and was thankful she didn’t have to depend upon herself to do the cooking.

Another good thing about these women was that they were affable without any of the falseness of those she’d known all her life. Each one wished her a happy birthday with sincerity and no expectations of learning more. That was the good thing about mornings. It was a new day. A new start. The conversation of last night was as dead to her as everything else she’d left behind.

Once the meal was over, she and Meg gathered the mules they’d staked nearby and hitched them to the wagons while the other two cleaned up their campsite. Lorna appreciated that Betty and Tillie didn’t mind doing those chores. Kitchen duties had never appealed to her, not like the stables. That was one thing she missed, the fine horseflesh that had lived in the barns back home. Her father had taught her to ride when she was very little, and the memories of riding alongside him were the only ones she cherished and refused to allow to become sullied.

Once set, all four of them climbed aboard the wagons.

The lead wagon was Meg’s and she drove it; the second one was Betty’s. Tillie’s had been lost in the river accident that took her husband’s life. This morning, Lorna sat in the driver’s seat of the second wagon. She and Betty, as well as Tillie, took turns driving it. Another chore she didn’t mind. Each step the animals took led her farther and farther away from England, and closer to California.

Tillie was on the seat beside her and Betty beside Meg. The trail they followed was little more than curved indents in the ground. Summer grass had grown up tall and thick, and Lorna wondered how Meg deciphered where the trail went and where it didn’t.

“Meg says we might cross into Wyoming today,” Tillie said.

“We very well may,” Lorna answered. They’d passed the strange formation of Chimney Rock a few days ago, and ever since then, Meg had been saying they’d be crossing into Wyoming soon. Truth was, as far as any of them knew, they might already have entered Wyoming. It wasn’t as if there was a big sign saying Welcome to Wyoming or any such thing. The area was neither a state nor territory, just a large plot of land the government hadn’t figured out what they wanted to do with yet. That was how Meg described it.

Lorna, like the others, had long ago put their trust in Meg’s knowledge. Although she had no idea how Meg had acquired such knowledge, it was admirable.

“Do you ever wish you hadn’t left England?” Tillie asked.

“No,” Lorna answered. She’d have to be dense to believe what she’d revealed last night wouldn’t eventually bring about questions, but she didn’t need to elaborate on them. Leaving England had been her decision, and she’d never questioned it. Nor would she. She was glad to be gone from there, and far from everyone who still lived there.

“Will you ever go back?”

“No.”

“You don’t like talking about it, do you?”

“No,” Lorna said. “That part of my life is over. No need to talk or think about it.” That, of course, was easier said than done. And a lie. Some days the memories just wouldn’t stop. More so today, an exact year since her stepfather had stolen the one thing that had been truly hers, and only hers. She’d win in the end, though; once she arrived in San Francisco, Douglas would get his due.

“Adam and I lived in Ohio,” Tillie said. “I’ve told you that before, but I didn’t mention that Adam’s father said he either had to join the army or go west.”

“I know,” Lorna said.

“How would you know? I never mentioned it.”

“Because most every man on that wagon train had made that same choice.”

“He chose west because of me,” Tillie said. “I was afraid he’d die being a soldier.”

Lorna held her breath to brace for what was to come. Tears most likely, and more blame. Tillie was a fan of both. The girl had had a hard time, Lorna would admit that, but at some point, enough becomes enough, as she herself had learned.

“Can I tell you something?” Tillie asked.

“Yes.” The answer hadn’t been needed. Tillie would go on either way.

“I’m glad we went west. I’m sorry Adam died, and that I lost the baby, but if he’d gone to the army, I’d be living with his parents now and would never have met you, or Meg or Betty. I would never have known how strong I am. How much I can do.”

Lorna glanced sideways just to make sure those words had come from Tillie. It wasn’t likely a stranger had appeared out of nowhere and jumped up on the seat beside her, but hearing Tillie saying such things was about as unexpected. After assuring herself that it was Tillie’s big brown eyes looking back at her—her curly red-brown hair was well covered by the black habit—Lorna grinned. “I’m glad you came west, too.” She was sorry for Tillie’s losses, but had said that plenty of times before. “And I’m glad you’re on this trip with me,” she added instead.

They conversed of minor things then, just to lighten the monotony of the trail. Tall grass went on as far as they could see in this wide-open country. There were a few small hills here and there, and a large line of trees along the river that ran just south of them. They’d camp near the river again tonight, like every night. Meg said farther into Wyoming, they wouldn’t have the water they did here in Nebraska. Lorna hoped they wouldn’t have the high temperatures, either. It was unrelenting. The yards of black material covering her from head to toe intensified the heat, making the sun twice as hot as it ever had been in England.

By the time they stopped for the noon meal, Lorna questioned if she’d ever been so sweaty and miserable in her life. She wasted no time in unhitching the mules and leading them down to the river for water. The poor animals had to be beyond parched.

“Sure is a hot one,” Meg said, dropping the lead rope as her mules stepped into the water and started slurping.

“Miserably so.” Lorna pushed the tight habit off her head and lifted the heavy braid of her hair off the back of her neck to catch the breeze. The relief wasn’t nearly enough. “I feel like jumping in that river and swimming clear to the other side.”

Meg looked up and down the river, and then over her shoulder where Betty and Tillie were busy seeing to the noon meal. It wouldn’t be much, just more tea and biscuits, and maybe some dried apple chips.

“Why don’t we?”

Lorna pulled her gaze off the other women to glance at Meg. She was smiling, which in itself was a bit rare. “I don’t know,” Lorna said, trying to conceal how her heart leaped inside her chest. “Why don’t we?”

“No reason I can think of,” Meg said. “You?”

Lorna shook her head. “Not a one.”

Meg glanced up and down the river one more time. “I gotta say, a swim sounds like a better way to celebrate a birthday than any stupid party with fancy dresses covered in lace.”

Lorna laughed. “I agree. And getting out of these heavy dresses for a moment would be heavenly, Sister Meg.”

Meg laughed. “Then, stake down your mules, Sister Lorna.”

Grinning, and with her heart skipping with excitement, Lorna didn’t waste a minute in staking the animals and then unbraiding her hair. She hadn’t been swimming in years, but it wasn’t something a person forgot. Hopefully! Then again, submerging herself in that cool river water would be worth almost drowning.

Meg shouted for Betty and Tillie to join them. In no time, all four of them were stripped down to their underclothes and running for the water, giggling like girls half their age. The water was as refreshing as Lorna imagined and not nearly as deep as it looked. She was halfway across the river before the water reached her waist, at which point she pinched her nose and fell onto her back. Sinking beneath the water was trivial, yet the most spectacular event she’d had in months. When she resurfaced, she stretched out and slowly kicked her feet to propel her around as she floated on her back. The water was like taking a bath, except that it smelled earthy and pure instead of cloying and sweet from the various flower oils her maid, Anna, had drizzled in the brass tub before she’d proclaim the bath was ready.

Of all the people she’d thought of over the past year, Anna hadn’t been in her memories at all. Yet the woman should have been. She’d been the one mainstay in her life, clicking her tongue and waggling a finger at the slightest misstep. Maybe that was why. As Tillie had pointed out, learning to take care of oneself was liberating. Lorna liked that. Taking responsibility suited her.

Stretching her arms out at her sides, she smiled up at the bright blue sky. Not answering to anyone was liberating, too. So was not being committed to doing anything or being anywhere she didn’t want to be or do.

This was how her life would be from now on. Free to do as she pleased.

“Well, well, well, what do we have here?”

The chill that encompassed her had nothing to do with the water. Lorna dropped her feet. As they sank into the soft sand, she turned to where the familiar male voice had come from.

Jacob Lerber stood on the riverbank, along with three other men who looked just as uncouth. They reminded her of the stories she’d heard about wolves, complete with evil eyes and yellow teeth.

All four of them had guns hanging off their waists. She’d learned since coming to America that only those who didn’t mind killing broadly displayed their weapons. Which was why she kept hers hidden, and would have had it on her right now if she hadn’t decided to go swimming. As it was, her little gun was still in a deep pocket in her dress...which was on the shore not five feet from Lerber. The man who’d sold her the tiny pistol had said it wouldn’t do any harm at a distance, but if a man got within three feet of her it would stop him dead in his tracks. The very reason she’d bought it. No man would ever get that close to her again.

“What do you want, Lerber?” Meg shouted.

“Hush,” Lorna hissed, inching her way to where the others stood in the waist-deep water. What Lerber wanted was obvious—making sure he didn’t get it needed to be the focus.

“Well, now, I was just worried about the four of you out here all alone,” Jacob drawled. “Thought I best backtrack and check how you fine ladies were getting along.”

“More likely you got kicked off the wagon train,” Meg yelled.

Lorna agreed, but hushed Meg again. “We’re getting along just fine,” Lorna said. “Thanks for stopping.”

“Thanks for stopping?” Betty hissed under her breath.

“Shush,” Lorna insisted.

“You can shush us all you want,” Meg snapped. “They ain’t leaving. Mark my word.”

“I know that,” Lorna replied. “I’m just trying to come up with a plan.”

“What you ladies whispering about out there?” Jacob shouted. “How happy you are to see us?”

The others beside him chortled, and one slapped him on the back as if Jacob was full of wit.

Intelligence was not what Jacob was known for. “Delighted for sure,” Lorna answered while gradually twisting her neck to see how far the opposite bank was. The men hadn’t yet stepped in the water. From the looks of Jacob’s greasy hair, he was either afraid of or opposed to water. If she and the others swam—

Her brain stopped midthought. What she saw on the other side of the river sent a shiver rippling her spine all the way to the top of her head. Lorna shifted her feet to solidify her stance in the wet sand and get a better view, just to make sure she wasn’t seeing things. The way her throat plugged said she wasn’t imagining anything.

“Indians,” Meg whispered.

That was exactly what they were. Indians. Too many to count. And they weren’t afraid of water. Especially the one on the large black horse who was front and center. He was huge and so formidable the lump in Lorna’s throat silenced her scream as his horse leaped into the water like a beast arising from the caverns of hell. The very image of her worst nightmare.

Water splashed as other horses lunged to follow him, and the Indians on their backs started making high-pitched yipping noises.

Frozen by a form of fear she’d never known existed, Lorna couldn’t move, didn’t move until the screeches of the women penetrated her senses. She spun to tell them to hush, but her attention landed on the other riverbank, where Jacob and his cronies ran beside their horses, attempting to leap into their saddles before the animals left them afoot. All four managed to mount, and watching them gallop away would have been a relief if the riverbed beneath her hadn’t been vibrating.

Waves swirled as the Indians rode past. Their stocky horses were swift and surefooted, and leaped out of the water to take after Jacob and his men. Their crazy yipping noises echoed off the water, the air, and vibrated deep inside her.

“What are we going to do?” Betty was asking. “What are we going to do?” Lorna spun back around, toward the bank still lined with huge horses and bare chests. One by one, the horses stepped into the water, and her fear returned ten times over. As her gaze once again landed on the great black horse hurdling the opposite bank, she muttered, “Hell if I know.”

Chapter Two (#u93838129-679b-5093-a0af-7fbd0f891812)

Black Horse slowed his mount while signaling four warriors to pursue the white men. It would take no more than that. He then spun his horse around to return to the riverbank and the women. Moments ago the four of them had been frolicking in the water like a family of otters in the spring. The sight of it, how their white clothes had puffed up around them, had made his braves laugh. He did not laugh.

One of his hunting parties had reported the women—four of them in two wagons—traveling alongside the river two days ago. At one time, many wagon trains traveled this route, but since the white men started fighting each other, the trains had almost disappeared. He had liked that, had welcomed the idea of fewer white people on Cheyenne land. The peace his people had known while his grandfather had been leading their band was his greatest desire. Inside, though, he knew peace would only happen when the white man and the bands learned to settle disagreements without bloodshed. He had left the last tribal council knowing that would not happen any time soon. Although many had agreed with him, some had not.

If not for the white men reported to be trailing these women, he would have let the women pass through Cheyenne land without notice, but he could not allow Tsitsistas to be blamed for what could happen to them.

Stopping at the water’s edge, Black Horse drew in a breath of warm summer air and held it. Bringing white women into his village would upset the serenity, but so would the army soldiers if something happened to the women. This was Cheyenne land, and his band would be blamed.

The tallest woman, the one with long brown hair that curled in spirals like wood peeled thin with a sharp knife, was not crying like the others, or running for the bank. She stared at him with eyes the same blue as the living water that falls from the mountains when the snow leaves. There was bravery in her eyes. A rarity. All the white women he had met acted like the other three. Other than Ayashe—Little One—but she had been living with Tsitsistas for many seasons.

Keeping his eyes locked on the woman’s, he motioned for braves to gather the others and hitch the mules to the wagons, and then nudged his horse toward the water. The woman did not move. Or blink. She stood there like a mahpe he’e, a water woman, who had emerged from the waves during a great storm, daring to defy a leader of the people. He had to focus to keep his lips from curling into a smile. Only a white woman would believe such was possible.

She held up one hand. “We come in peace.”

No white person comes in peace. Not letting anything show, especially that he understood her language, Black Horse lifted his chin and nodded toward the wagons. “Tosa’e nehestahe?”

The frown tugging her brows together said she did not understand his question of where she came from. He had not expected her to know the language of his people, but had wanted to be sure. Others like her had come before. Dressed in their black robes that covered everything but their faces, they tried to teach people about a god written on the pages of a book. Each Indian Nation had their own god and no need to believe in others, or books.

Faint victory shouts indicated his warriors had caught up with the men that had disappeared over a small knoll, and Black Horse waved a hand toward the wagons, indicating the woman should join the others.

Her cold glare glanced at the other women putting their black dresses over their wet clothes. Only white people would do that. Their ways made little sense.

Turning back to him, her eyes narrowed as she asked, “What do you want with us?”

There were many advantages to knowing the white man’s language, and more advantages in not letting that knowledge be known. He waved toward the wagon again.

Her sneer increased. “What? You grunt and wave a hand, and expect me to know what you want and to obey? Let me assure you that will not happen.”

She was not like the other holy women he had encountered. They had all been quiet and timid. She was neither.

Earlier she had skimmed across the water with the ease of an otter, and catching the sense she was about to do so again, Black Horse urged Horse into the water.

The woman looked one way and then the other, and then, just as he expected, she shot under the water.

The water was not deep enough to conceal her or her white clothes, and he tapped his heels against Horse’s sides. He caught up with her just as she lifted her head out of the water, and the look of shock on her face made him hide a smile.

“Get away from me, you filthy beast,” she shouted. “Get away!”

As one would a snake, Black Horse shot out a hand and grabbed her behind the head. Grasping the material between her shoulders, he lifted her out of the water. She was as slippery as a fish and her fingernails scratched at his arm while she continued shouting and kicking her feet. Despite her fighting, he draped her across the front shoulders of Horse. Keeping her there took both hands, but Horse needed nothing more than a touch of heels to spin around and return to the bank. He and the animal had been together since Horse had been a colt. Shortly after acquiring Horse, others had started calling him He Who Rides a Black Horse, and though many events had occurred that offered to provide him with a different name, he did not take one. He liked being known as Black Horse.

Her kicking and squirming almost caused her to slip from his hold when Horse stopped on the bank to shake the water from his hide. In that one quiet moment, Black Horse could feel her heart racing against his thigh. It startled him briefly, the contact of another person. It had been a long time.

Once Horse started walking again, she started her kicking, squirming and screaming all over and Black Horse renewed the pressure on her back. When Horse stopped near the wagon, Black Horse balled the material across her back into his hand. Just as he started to lift her, a sharp sting shot across his leg.

Before her teeth could sink deeper, he wrenched her off his lap and dropped her to the ground. “Poeso,” he hissed. She had the claws and teeth of a poeso—a wild cat. There was no blood, because the hide leggings had protected his skin. They had protected him against far worse, but he still had to rub the sting from the area.

His braves as well as the other women were watching, waiting to see what would happen next. If he had been only a warrior, the braves would have laughed at what the white woman had done, but because he was the leader of their people they stood in silence, waiting to follow his next move, whatever he chose it to be.

The woman continued to hiss and snarl like a cat, having no idea she had just offended a leader of the Cheyenne Nation, and Black Horse accepted her ignorance. He prided himself on being a highly respected leader, one who did not make decisions based on spite, but on thoughtful deliberations. He ignored her screeching while gesturing for the men to finish hitching up the mules—until one word she said caught his attention.

Black Horse jumped off Horse and wrenched the bundle of clothes out of her hands, searching until he found what she was after. Holding up the little gun, he laughed. It was smaller than his fingers.

“Laugh all you want, you beast!” she shouted. “It can still kill you. It’s called a gun.”

Why did all white people think only they knew what guns were? The fur trade wars over a century ago had brought guns to all the people, back before Tsitsistas had started following the buffalo. But guns wore out and could not be repaired, and were much less accurate when it came to hunting than bows and arrows. Their thundering noise scared more buffalo than their bullets killed.

He tucked the gun in the pouch hanging on his side and tossed the clothes at the woman, along with the pair of stiff boots that were lying on the bank. Shrill calls from his returning warriors filled the air and he grinned. Just as he had known, each brave led a horse behind him.

“They killed them that fast?” the woman asked, eyes wide.

“Hova’ahane,” he answered, knowing she had no idea he had just told her no. Tsitsistas were not conquerors. Not the northern bands. His warriors rarely killed unless threatened. It was his goal to make sure it remained that way.

“Tahee’evonehnestse,” he said, once again waving toward the wagon, telling her to get on with the others, who had obeyed his braves while this poeso battled him. There was always one. Always a he’e—a woman—who refused to listen; for a moment he wondered if saving her, if being a fair and just leader, was worth the trouble.

* * *

Lorna knew the brown beast of a man, with black hair hanging way past his shoulders and wearing a scowl as fierce as the rest of him, wanted her to get on the wagon with the others, but she wasn’t about to. Men, no matter what nationality, thought that because of their strength they could order women about, make them grovel and beg and plea. She’d lived that way once, and never would again. Furthermore, this man was worse than all the others she’d known. Stronger. The strength of his hold could have easily broken her spine, and his thighs had been harder than logs. The fact he hadn’t killed her said one thing. He was saving her for worse. Much worse.

That wouldn’t happen again.

Turning toward Meg, Tillie and Betty, who were peeking out of the canvas opening in the back of Meg’s wagon, Lorna shouted, “Get out of there! We can’t go with them!”

“We don’t have a choice,” Meg answered. “We only have one gun, and if you haven’t noticed, there are twenty of them.”

“I don’t care how many there are!”

“You may want to be killed,” Meg said, “but I’d like to see tomorrow.”

“Which we won’t if we go with them,” Lorna insisted.

“These are Cheyenne Indians. They’re peaceful.”

Just then the beast grabbed her by the back of her camisole again, and the back her bloomers. “You call this peaceful?” she shouted at Meg between screaming at him to let her go.

Lorna kicked and continued to scream, but the black-haired heathen carried her to the wagon and tossed her inside as if she weighed no more than a feather pillow. Unable to catch hold of anything, she hit the other women and they all tumbled among the crates and chests. Before they managed to get up, a brave jumped in the back.

His presence had Tillie and Betty whimpering, and Meg pulling Lorna’s hair.

“Stay down,” Meg hissed. “The Cheyenne are peaceful Indians, but I’m sure they’ll only take so much from a white woman.”

“I’ll only take so much from them.” Lorna wrenched her hair away from Meg. The wagon lurched and she planted a hand on top of a trunk to spin around. Another brave was driving. “Did you hitch up the mules?”

“No,” Meg said. “The braves did while you were arguing with their chief in the middle of the river.”

“How do you know so much about Indians?” Lorna asked.

“I told you, I made the trip to California before.”

Meg had told her that, but Lorna hadn’t believed it. Whether she acted like it or not, Meg wasn’t old enough to have gone all the way to California and back to Missouri. At least that was what Lorna had believed up until now. Meg did seem to know a lot about a variety of things they’d needed to know along the way, including Indians, it appeared, but she had figured Meg had learned most of it from reading about it. Just as she had. She’d also hoped they wouldn’t encounter any Indians. None.

Flustered, Lorna said, “He’s not a chief. He doesn’t have a single feather in his hair.” Or clothes on his body, other than a pair of hide britches and moccasins. She chose not to mention that. The others had to have noticed.

“They don’t wear war bonnets all the time,” Meg said. “White people portray that in paintings and books because it makes the Indians look fiercer.”

Lorna glanced at the brave sitting on the back of the wagon. “No, it doesn’t.” If you asked her, a few white feathers among all that black hair might make them look more human. Not that humans had feathers, but wearing nothing other than hide breeches and moccasins, these men looked more like animals than humans. Especially the beast who’d plucked her out of the water. The one who’d stolen her gun. She would get that back. Soon.

She was where she was because of a man, and another, no matter what color his skin might happen to be, was not going to be the reason her life changed again. Was not! She’d fight to the death this time. To the very death.

“Give me those,” she snapped while snatching her clothes from beneath the feet of the brave who sat on the tailgate. It was difficult with the wagon rambling along at a speed it had never gone before, and with the others crowded around her, but Lorna managed to get dressed—minus the habit—and put on her boots.

She then scrambled past Meg and over the trunks until she stuck her head out of the front opening. The brave was too busy trying to control the mules to do much else. Lorna climbed over the back of the seat—despite how Meg tugged on her skirt—and sat down next to him. The other wagon was following them at the same speed. The braves surrounding them had their horses at a gallop, too. The mules would give out long before their horses would; even she could see that.

Whether he was a chief or not, the man on the black horse was a fool to force the animals to continue at this speed. She needed these mules to get her to California.

“What’s his name?” she asked, pointing toward the leader of the band. The one atop the finest horseflesh she’d seen since coming to America. If she had an animal like that, she could have ridden all the way to California, and been there long before now.

The brave hadn’t even glanced her way.

“What do you call him? That one on the black horse?”

The brave didn’t respond.

“Him,” she repeated, “on that black horse, what is his name?”

The brave grunted and slapped the reins across the backs of the mules again.

Lorna let out a grunt, too, before she cupped her hands around her mouth. “Hey, you on the black horse!” When he glanced over one shoulder, she added, “You better slow down! Mules can’t run like horses!”

He turned back, his long hair flying in the wind just like his horse’s mane. The two of them, man and horse, appeared to be one, their movements were so in tune.

“Did you hear me?” she asked.

“Everyone heard you,” Meg said from inside the wagon. “Hush up before you irritate him.”

“I don’t care if I irritate him,” Lorna answered. “He’s already irritated me.”

“He saved us from Lerber.” That was Betty. “They all did. Shouldn’t we be thankful for that? Show a little appreciation?”

Lorna spun around to let the other woman know her thoughts on that. Words weren’t needed. Betty cowered and scooted farther back in the wagon.

“My guess,” Meg said, “is that is Black Horse. He’s the leader of a band of Northern Cheyenne.”

Lorna shot her gaze to Meg. “How do you know that?” The name certainly fit the man.

“I’m just guessing,” Meg said. “They’ll slow down after we cross the river. They are putting distance between us and Lerber.”

“Distance? Why?” Lorna asked. “They killed Lerber.”

“No, they didn’t. I told you they are Cheyenne. They just stole their horses.”

“You can’t be sure of that.” Lorna certainly wasn’t.

“They are the reason I said we had to take the northern route,” Meg said. “The Indians are friendlier. Southern Indians, even bands of Cheyenne, are the ones that kill and kidnap people off wagon trains. They use them as slaves.”

Lorna had assumed Indians were all the same, no matter what band they were. “How can you possibly know that?”

Meg chewed on her bottom lip as if contemplating. After closing her eyes, she sighed. “My father was a wagon master. He led a total of eight trains to California. Two of them, I was with him.”

Lorna hadn’t pressed to know about a family Meg never mentioned. “Where is he now?”

“Dead.”

The word was said with such finality Lorna wouldn’t have pushed further, even if she hadn’t seen the tears Meg swiped at as she sat down and looked the other way.

Lorna swiveled and grabbed the edge of the wagon seat. The horses and riders ahead of them veered left and the wagons followed, slowing their speed as they grew nearer to the trees lining the river. A pathway she’d never have believed wide enough for the wagon, let alone even have noticed, widened and led them down to the river. The brave handled the mules with far more skill than she’d have imagined, or than she had herself. As long as she was being honest with herself she might as well admit it. With little more than a tug on the reins and a high-pitched yelp, he had the mules entering the river. The water was shallow. Even in the middle, the deepest point, it didn’t pass the wheel hubs.

In no time they’d crossed the river and traveled into the trees lining the bank on the other side. Just as Meg had suggested, their pace slowed and remained so as they made their way through a considerable expanse of trees and brush. The trail was only as wide as the wagon, and once again, Lorna sensed that you had to know this trail existed in order to find it. She did have to admit the shade was a substantial relief from the blazing sun they’d traveled under for the past several weeks. She’d take it back though, the heat of the sun that was, to regain her freedom from this heathen as big as the black horse he rode upon.

He hadn’t turned around, not once, to check to see if they’d made it across the river or not, but she’d rarely taken her eyes off him.

“Where are you taking us?” she asked the brave beside her.

A frown wrinkled his forehead, which didn’t surprise her. English was as foreign to him as their language was to her. Turning toward Meg, she asked, “Where are they taking us?”

“Their village would be my guess,” Meg said.

“Why?”

“I haven’t figured that out yet.”

“I have,” Lorna said. “To kill us, right after they rape us.”

“No, they won’t,” Meg insisted. “But that is what Lerber would have done.”

Lorna didn’t doubt Meg was right about Lerber, nor did she doubt that this band of heathens would do the same. Despite Meg’s claims. She’d read about the American Indians, in periodicals from both England and New York. Anger rose inside her. If only the railroad went all the way to the West Coast she would have been riding in a comfortable railcar, like the one she’d traveled in from New York to Missouri. There had been heavy velvet curtains to block out the sun and a real bed. Tension stiffened her neck. Getting to California was worth sleeping on the hard ground, and no one, not even a band of killer Indians was going to stop her from getting there.

“Look at that.”

Lorna turned at Tillie’s hushed exclamation. As the wagon rolled out of the trees, a valley of green grass spread out before them, with a winding stream running through the center of it. Teepees that looked exactly like ones in the books she’d read were set up on both sides of the stream, hundreds of them. The scent of wood smoke filled the air and a group was running out to meet them on the trail. It wasn’t until they grew closer that she realized the group was mainly children and dogs. Some of the dogs were as tall as the children they ran beside, others tiny enough to run through the children’s legs, and many of them were decorated with feathers and paint. She’d read about Indians doing such things to their horses, but not their dogs.

What strange creatures they were, these Indians, and for a brief moment, she wondered what her mother would think of this peculiar sight. Mother hated America, which was partially why Lorna had chosen to return here. Maybe these creatures were part of the reason her mother hated her father’s homeland so severely.

Lorna had told herself she’d love America, if for no other reason than to spite her mother, but painted dogs were hard to ignore. As hard to ignore as the man on the black horse.

Most of the children now ran a circle around him, yipping and clapping. The last trek of their journey he’d led them at a pace the mules were much more accustomed to—slow, miserably slow. As their train rumbled forward, the smaller children and their dogs headed back toward the camp, whooping and yelling in their language. It sounded ugly and harsh, especially when shouted at such a volume. A few of the group, older boys it appeared, ventured all the way to the wagons, where they chattered among themselves and pointed at her sitting on the seat as if she were a circus attraction.

Usually, children and their innocent tactics humored her, but these, as scantily dressed as the big man on the black horse, were alarming. She waved a hand to shoo them away, but they laughed and continued walking alongside the wagon. Shouting, telling them to be gone did little more than make them laugh harder, and mimic her.

“Aren’t they adorable,” Tillie whispered.

It hadn’t been a question, but Lorna answered as if it had been. “Hell, no!”

“Sister Lorna!” Tillie reprimanded. “You shouldn’t curse.”

Being scolded wasn’t necessary. She’d rarely said a curse word before in her life, but today, they were jumping out of her mouth like frogs. Justly so. “I’m no more of a sister than you are, and I doubt the disguise will do us any good here.”

“Nonetheless, you shouldn’t curse. Especially not in front of children.”

“These are Indians,” she answered. “Heathens. The children are just like their parents. Their leader,” she added with renewed scorn. “Besides, they can’t understand a word we say.” Then lifting a hand, she pointed to the others now rushing out to greet them. “None of them.”

“Oh, my,” Tillie whispered.

“Oh, yes,” Lorna mocked. “Oh, my.”

There was now a great amount of shouting, and barking dogs, and those whooping sounds that made the hair on the back of her neck stand straight. The entire village, or at least half of it, now approached the wagon. Old and young lined the trail, babbling strange words and pointing as if watching a parade. The men were shirtless, other than a few who actually had on shirts or vests—stolen from white men they’d killed most likely—and the women had on hide dresses covered with beads and other trinkets. Most of the men wore ankle-high moccasins on their feet, but some men and almost all of the women wore fringe-topped boots made of hide that came up to their knees.

Their little wagon train, still led by the beast Black Horse, traveled all the way to the center of the encampment before stopping. The men on horseback, all except their leader, road several fast circles around the wagons, yipping loudly. The ones leading the horses they’d stolen from Lerber were the loudest, and in turn, received the loudest cheers from the crowd that had gathered.

Their screeches and chants were enough to make a person’s blood run cold. Lorna’s did, and she turned to Meg. “Friendly, you say.”

The astonishment, which was a combination of fear and shock, on Meg’s face sent Lorna’s heart into her throat.

Chapter Three (#ulink_4a0b9c20-b32d-5f1c-a2a3-51817100a519)

The white women in the wagon cowered together, holding on to each other as fear filled their eyes. Except for the water woman. She had not covered her mass of curls with the black material like the others, and her stare was not full of fear. It was cold and directed at him. Returning her stare, Black Horse lifted his chin, and allowed the celebration to continue. Acquiring horses, no matter how small the number, was a great accomplishment for any warrior. Because all bands were preparing for the hunting season, raids on Crow or Shoshone for horses had not happened since Tsitsistas had started to move north, and his warriors were enjoying the reception as much as if they had brought home dozens of ponies.

Four other bands had joined his to follow the great herds of buffalo, which was the way their fathers and their fathers’ fathers had done it. Displaying the rewards of the day before other warriors caused great excitement for his entire band.

The bands would separate again after the hunt, each leader taking his people to where they would continue to hunt for deer and elk and then reside until the snow once again melted. As long as the white soldiers continued fighting each other far away, where the sun rose each morning, his people would have another peaceful winter.

A shiver tickled his spine and he hardened his stare at the white woman. More than one tribe had been led into a trap set by the white man. The massacre in Nebraska had been a trap, and the white man’s want of the yellow rocks had caused many other battles. Two winters ago in the land the whites called Minnesota a large number of Sioux had been killed and the survivors had been forced to move west, into Cheyenne land. This spring, after the tribal council, messengers had said the white man found more yellow rock north of Cheyenne land. There would be more battles. More tricks. More traps.

Black Horse lifted a hand. The reception had lasted long enough. “Nehetaa’e!”

His command was instantly obeyed. The warriors slowed their ponies and those gathered near quieted. He then commanded four braves who were married to each take a white woman to their lodges and have their wives look after them. Then he commanded others to take the wagons outside the last circle of lodges and search them thoroughly.

Mahpe he’e, water woman, as he’d aptly named her in his mind, was again the only one to protest, biting and scratching Rising Sun as he attempted to lift her out of the wagon. Black Horse turned away, knowing the warrior was much stronger. After dismounting, he handed Horse over to the young boy waiting for the duty.

“Hotoa’e?” the boy asked.

“Hova’ahane,” Black Horse answered, shaking his head. They had not found buffalo on this day, but soon would. Sweet Medicine promised a successful hunt. Not just to his band, but the others camped with them.

The boy, Rising Sun’s child, nodded and started to lead Horse away, but stopped at the sound of his father’s howl. Black Horse spun around to spy the woman launching herself into the air, claws out.

He caught her by both arms and held her in the air. She would have landed on his back and dug those claws deep into his skin if he had not turned around. Like a mountain cat. Poeso was a much better name for her. She was as wild and most likely as devious as a cat.

Her feet struck his shins as she shouted into his face, “Give me my gun, you ugly heathen!”

He spun her around, but that just made her kick backward. The heels of her boots made his shins smart. Grasping both of her arms in one hand, he wrapped his other arm around her waist to hold her close to his side where her feet could no longer meet with his legs. He lifted his head to shout for Rising Sun to come get her, but the warrior had dread in his eyes. His wife, Little Dove, who was wiping at the blood trickling down her husband’s arm, did not look at him. Did not need to. Black Horse recognized that she did not want the responsibility of the white woman any more than her husband, but they would take her if he told them to.

The white woman was still shouting, and squirming. Black Horse had had enough, and told her so. “Nehetaa’e!”

“Don’t shout at me in that wretched language!” she yelled in return.

Black Horse tightened his hold and glanced around, looking for someone to take the woman. Not a single warrior met his gaze. They all stood stock still, waiting to hear who he would command to take her. Except Sleeps All Day, who scurried away as if suddenly remembering an imminent task. The celebration must have awoken him. Sleeps All Day, along with those he oversaw, stood guard through the moon hours while others slept, and took great pride in his post. He was also unmarried, and therefore not one who could take the woman.

A just leader does not request others to do things he would not do himself, and Black Horse stood by that. Always had. It was part of the reason his band was so strong.

Turning slowly, Black Horse caught the gaze of the only person looking at him. She Who Smiles. His mother-in-law was a gentle woman, not one he could turn this wild poeso over to, even though She Who Smiles stepped closer, nodding.

It was a moment before the white woman stopped shouting long enough to hear She Who Smiles’s soft voice.

Poeso twisted and after giving his mother-in-law a cold glare, turned it on him. “What does she want?”

Black Horse had to bite his tongue to keep from answering in her language. There had been no fear in her eyes before, but it was there now. For no reason. She Who Smiles never raised a hand at anyone. Not even him. Not even after he’d killed her daughter. She Who Smiles did not blame him for Hopping Rabbit’s death. No one did. Except him. He had fallen for one of the white man’s traps, and it had stolen his family from him. If he had been a mere brave, he would have revenged the death of his wife and his son, but a leader had to think of what was best for all, not just for himself.

“What does she want?” the white woman repeated, this time with excruciatingly slow pronunciation.

Burying his thoughts in that dark and hollow grave inside him, he nodded. “Epeva’e,” he said, telling her it was all right for her to go with She Who Smiles.

Lorna shook her head. She had no idea what he’d just said, but understood she was to go with this woman. Not likely. She wasn’t about to go anywhere without her gun. As Black Horse’s hold lessened, she spun. During her fight to get away from the other Indian in order to retrieve her gun from him, she’d lost sight of Meg, Tillie and Betty.

The area that had been as crowded as a marketplace was now empty, and eerily quiet. Even the wagons were gone. She spun back around. Black Horse had completely released her, but there was no sense in attempting to attack him again. His strength was beyond her. Her ribs could very well be bruised from the hold he’d had on her a moment ago.

Softly, the tiny woman whispered something in their language. Coming from her, the words didn’t sound nearly as harsh or ugly as when he spoke. The woman had kind eyes and her long black hair was streaked with gray, which made her look soft and pretty rather than old as one would think.

“I don’t know what you are saying,” Lorna said, frustrated. “I don’t know what anyone is saying, or doing, or...” She pinched at the bridge of her nose in an attempt to hold back the tears. Crying would not accomplish anything, nor would it change anything. She’d promised herself she’d never be in this predicament again. Never be at the mercy of someone else. Ever. She’d crossed the ocean alone, and traveled from New York to Missouri alone.

Lorna lifted her chin. She could do this, too. Glancing between Black Horse and the tiny woman, she chose the woman. Escaping her would be easy. Then she’d find Meg, Tillie and Betty, and the wagons. By nightfall, they’d be well away from these heathens.

Squaring her shoulders, she stepped away from the man and closer to the woman.

They said a few words to each other, things she couldn’t understand, but Lorna didn’t let that bother her. She’d find a way to get her gun back. It was still in the pouch hanging off his waist. Considering his strength, getting it back would not be easy, but not a whole lot had been easy the past year, and that hadn’t stopped her.

He gave her a nod before turning and walking away. Lorna watched to make note of which tent, or teepee as she had read they were called, he entered. As she’d informed Meg, she’d read about the American Indians while on the train from New York and wasn’t completely ignorant of their ways. However, the teepee he ducked down to enter looked no different from the dozens surrounding it. She tried counting from the end of the row, so she’d know which one was his, but there wasn’t a row. Instead, the teepees made a complete circle. Several circles actually. One large one with several smaller ones inside it.

The woman said something softly and gestured for Lorna to follow. She did, all the while trying to make sense of the layout and how to get back to the teepee Black Horse had entered. The farther they walked, the more confusing it became. The circles of teepees were not full circles, but half circles that formed another circle, and then another one. The entire area was a full circle of teepees. The layout was as symmetric as it was perplexing.

Other women and children, as well as a few men, went about their business, never glancing their way as she followed the older woman. The chatter that had once gone silent was about them again, but this time it wasn’t frightening, it just was. Like the noise at the market square or in a neighborhood full of children and good cheer. So were the colors. The teepees were brightly decorated, and Lorna couldn’t imagine where the Indians got the paint from, for it surely wasn’t something people on wagon trains hauled, and she assumed that was how the Indians got most everything they needed. They stole it.

Unless, of course, there was an army post nearby. Most of those had been abandoned, from what Meg said. The soldiers were needed back east to fight against one another. The thrill of having an army post nearby quickly dissolved. From what Meg had said, the few army men left in the west could not be trusted. Then again, she hadn’t been right about the Cheyenne Indians being friendly, so maybe there was a lot she wasn’t right about.

Friendly Indians would have chased away Lerber and his cronies and left them alone. Not have stolen their wagons and brought them here.

The Indian woman had stopped before a teepee and nodded slightly. Lorna glanced around a final time. While walking, she’d kept an eye out for her friends, but hadn’t seen a glimpse of any of them. She wasn’t a fool. Attempting to run away in the maze of tents would get her nowhere.

With a nod of her own, Lorna bent down and entered through an opening the Indian woman held apart. The interior was primitive. As had been her home the past few months, but while sleeping beneath a wagon, she’d been surrounded by familiar things. Here, she didn’t recognize much of anything. The teepee was circular, with tall logs that allowed her to stand once she’d entered. The narrow poles, at least twice as tall as she, were rather remarkable. They appeared to be identical in length and circumference and neatly fit together at the top, leaving a hole that allowed the sunlight to brighten what might otherwise have been a dark and confining space. Despite the sunlight, it was surprisingly cool inside, and much larger than she’d imagined.

“Nehaeanaha?”

Lorna turned to the other woman and shook her head while shrugging. “I don’t know what you are saying.”

The woman put her fingers to her lips. “Nehaeanaha?”

“Eat?” Lorna mimicked the action. “Nehaeanaha means eat?”

Repeating the action again, the woman nodded. “Nehaeanaha.”

“Why would it need so many syllables?” Lorna asked.

The woman frowned.

Shaking her head, Lorna said, “Never mind.”

“Nehaeanaha?”

Considering their lunch had been interrupted, food didn’t sound too bad. It would give her time to create a plan. “Sure,” Lorna said. “Why not?” Then, trying her best to copy the other woman’s word, she added, “Nehaeanaha.”

The woman’s smile never faded as she gestured for Lorna to sit on a pile of what looked like animal furs before she moved to where several things sat along the edge of the teepee—bowls and such. A few minutes later the woman handed Lorna a wooden bowl with chunks of jerky and a wooden tumbler full of water.

Once her thirst was quenched, Lorna took a bite of the jerky. It was hard and rather tasteless, but she ate it. That was one thing she’d learned since leaving home. Picky eaters went hungry, and hungry people had no energy. She needed all the energy she could get. There was a lot she had to do, and little time.

The woman refilled her bowl as soon as Lorna took out the last piece. Although her stomach could handle more, her jaw couldn’t. “No, thank you,” she said. “I’ve had enough.”

Still smiling, the woman nodded and took away the bowl.

“What is your name?” Lorna asked.

The woman shook her head and shrugged.

Lorna pointed at her chest. “Lorna.” Pointing at the woman, she asked, “Your name?”

The woman nodded and said a single word long enough it would have filled up an entire diary page.

“Uh?” Lorna asked. There was no way she could even attempt to pronounce what had been said.

Smiling brighter, the woman pointed at her lips.

“Happy?” Lorna asked. “You’re happy?” Shaking her head, she added, “I’m glad someone is.”

The woman pointed at her lips again, making her smile bigger.

“I see your smile.” She pulled up a fake one. “See mine?”

The woman giggled.

Lorna giggled, too. These were some strange people. Whether it was her name or not, Smile was a fitting name for the woman. Lorna drank the last of her water and held out the cup. “Thank you.”

Smile returned the cup to the edge of the teepee and then carried something else across the small area. To Lorna’s surprise, it was a hairbrush, a primitive one, but it would do the job. Her hair was a mass of snarls after swimming, and she reached for the brush.

With another ten-syllable word, Smile refused to hand over the brush. Instead, she sat down beside Lorna and started to brush her hair. Anna used to do that, but she’d been merciless when it came to wrenching apart the curls that twisted among each other, whereas Smile was gentle, brushing small sections at a time.

Other memories of England floated through Lorna’s mind. Of her mother. A memory she’d forgotten. Mother had never brushed her hair because once, when Lorna had been very little, Mother had cut it all off. Right to the nape of her neck. Her father had been furious and forbade her mother from ever touching her hair again. Mother hadn’t. Even after her father died. Lorna had been only seven, and didn’t remember a lot about him, considering he’d been absent more than not, but she did remember riding with him, and that hair-cutting incident. How mad he’d been over it.

Smile said something, and the memories disappeared as quickly as they’d formed. “I don’t understand what you’re saying,” Lorna said again.

With her smile never faltering, the woman rose and crossed the small space again. This time toward a pile of things on the other side of the opening. When she turned around, she was holding a hide dress, much like the one she wore. She then pointed at how Lorna’s dress was still wet in spots.

Lorna shook her head. “Oh, no,” she said. “My hair needed to be brushed, but we aren’t playing dress up. Wet or not, I’m not putting that on. I need to find my friends.” It was clear Smile didn’t understand. Lorna rose and crossed the room. Taking the dress from the other woman, she folded it and placed it on top of a pile of other things. “My friends,” she repeated. “The other women with me. I must find them so we can leave.” Waving a hand toward the teepee surrounding them, she said, “We can’t stay here. We are going to California.” Since the other woman didn’t understand a word she said, Lorna added, “I need to check on an investment, one my father willed to me. I’ll be a very rich woman then. I could pay you to help me escape.”

Lorna sighed then, knowing the Indian woman had no idea what she’d said. “I’ve told you more than I’ve told the women I’m traveling with.”

Still smiling, Smile nodded again.