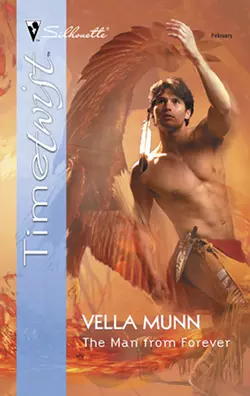

The Man From Forever

Dawn Flindt

OUT OF THE MISTS OF TIMEWhen she first came to the sacred tribal land in the California wilderness, anthropologist Tory Kent paid little heed to the tales of a mystical warrior keeping watch there. But then a dark figure appeared through the mists before her–and suddenly the unimaginable became reality. Wherever–whenever–he had come from, the one called Loka was truly a man, and he awakened a need within Tory that could scarcely be denied. For he had returned, after a century in the shadows, to claim her–the woman destiny had promised only to him. Though entangled by undeniable passion, each walked a path seemingly impossible to weld together. For Tory was tied to the present. And Loka was bound by an age-old promise to protect his people's legacy…even at the cost of his own life.

“LOKA, I FELT SOMETHING THAT FIRST DAY.”

He shrugged, the gesture low and studied. If he’d thrown a thousand words at her, the impact couldn’t have been greater. She would never say there was a vulnerability to him, but something—maybe it was the loneliness he’d endured since his awakening—was etched on every line of his body. She was the first human being who’d touched him in six months—no, in more than a hundred years.

Thinking of nothing except putting an end to that, she slipped closer.

He watched her, his beautiful eyes seeing things in her she knew no one else ever had. I’ve been alone, too, she said with her heart.

His powerful fingers closed over her wrist and drew her close, closer, gentle despite his strength. Silence coated the air between them and yet she knew.

He wanted her.

Dear Reader,

Welcome to the wild, windblown world of the Lava Beds in Northern California, the location for The Man from Forever. More than a hundred and thirty years ago, the Modoc Indians fled a reservation and found shelter in the caves created by ancient volcanic eruption.

Although their battle is over, the area has been made into a national landmark. When I went there, I gave myself over to the quiet beauty of a stark land untouched by progress—a land where the spirits of those brave people wait to touch and be touched. I knew I had to write about a warrior capable of facing great danger as he bridges time and space and the woman who takes him from loneliness to fulfillment.

I hope you enjoy reading that warrior’s story as much as I loved writing it. I’d love to hear from you at vmunn@attglobal.net.

Sincerely,

Vella Munn

The Man from Forever

Vella Munn

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

Although Loka and Tory are fictional characters,

The Land of Burned Out Fires and

the Modoc Indians are real.

Located in Northern California,

the Lava Beds National Monument stands as a testament to

the resourceful Native Americans who once made that

fascinating land their home.

I am honored to dedicate this book to the spirit,

the essence, of those people.

Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Epilogue

Prologue

The warrior’s body woke, one slow, gliding movement at a time. He became aware of sound—a distant, half-remembered whisper of wind sliding its restless way over the land. He remembered—remembered closing himself in the cave’s darkness beside his dying son, swallowing the shaman’s bitter potion, feeling strength flow out of his body, losing control of his thoughts. Losing the thoughts themselves.

How long ago had that been?

He lay on the bear pelt he’d spread on the ground for his forever sleep. The air moving almost imperceptibly over his naked body felt warm, yet not quite alive—ancient air. He was in Wa’hash, the most sacred of places.

Strength flowed into his war-honed muscles. He gave thanks to Eagle for the power in his body. Cho-ocks the shaman had been wrong. The mix of ground geese bone, bunchgrass and other things unknown hadn’t ended him after all. He couldn’t stay in the underworld with his son; something—or was it someone?—had brought him back.

Back to empty-bellied children, despairing women and men ready for battle.

The anger that had fed him and his chief and the others during that cruel-cold winter of 1873 returned in powerful waves. They were Maklaks—the Modocs—proud people living on land given to them by Kumookumts, their creator. The white skins had had no right to bring their cattle and horses and fences here. The army had had no right to force them to live on a reservation with their enemy, the Klamath. But those things had happened.

Sitting, he tried to hold on to his anger, but his body tightened into a brief, pain-filled knot. He breathed through it, kneaded his calves and thighs, then forced himself to stand. His belly felt utterly empty, his flesh unwashed, but those things didn’t matter. Soon his eyes would make the most of the sliver of light coming in through the small opening.

Another kind of hunger touched him with hot, familiar fingers. It pulled him away from urgent questions about what had brought him back to life. His manhood signaled a message that he’d learned to master during the long, cold months of hiding and fighting. Either he’d forgotten how to keep need reined in or something was—

Something or someone.

Like a wolf after a scent, he left his son’s bones and went in search of light, taking with him the knife his grandfather’s grandfather had created from the finest black rock. His legs unerringly led him down the narrow tunnel that led to the surface and, hopefully, understanding. When he reached the place where surface and tunnel met, he picked up the ladder, but the rawhide that held the wood in place was dry and brittle. Although he had never cowered from an enemy’s bullet, he shuddered now. It took many seasons for rawhide to become useless.

After freeing the sturdiest pole, he used it to shove aside the rock that covered the hole. Then he sprang upward, hooked his hands over the rocky ground and pulled himself up. Bright sunlight assaulted his eyes. The wind brought with it the sweet, endless smell of sage, and for a moment he believed that nothing had changed. Peace didn’t last long enough.

The enemy.

Cautious, he rose to a low crouch. The Land Of Burned Out Fires was as it had always been, stark and yet beautiful, home to the Maklaks, rightful place of things sacred and ancient. He could see nearly as far as he could run in a long day, the horizon a union of sky and earth. Knife gripped in fingers strong enough to build a fine tule canoe, he balanced his weight on his powerful thighs and spun in a slow circle. Shock sliced into him, almost making him bellow.

The mother lake that had always fed his people had shrunk! Shock turned into rage, then beat less fiercely as the emotion that had brought him out here reasserted itself.

The enemy.

Only, if he could believe his senses, this unknown thing wasn’t a soldier or settler. The knowledge tore at his belief in who and what he was in a way that had never happened before. The morning the army had set fire to the tribe’s winter village, he’d felt as if the energy of a thousand volcanoes had been unleashed inside him. This, too, was a volcano—heat and fire.

Sucking in air, he forced himself to seek the source of the heat. For a heartbeat he thought he’d spotted a deer or antelope, but his keen eyesight soon brought him the truth.

A woman was out there, so far away that he could tell little about her except that she was unarmed, lean and long, graceful. She walked alone, stepping carefully and yet effortlessly over lava rock and around brush sharp enough to tear flesh.

The enemy, this woman?

She stopped, head cocked and slightly uplifted. Her arms remained at her side, yet there was a tension to them that struck a familiar chord inside him. He viewed the world of his childhood and his ancestors’ childhood through untrusting eyes. She was doing the same, trying to make sense of something that kept itself hidden from her.

Let her be afraid.

He slipped around rocks and bunchgrass until he was close enough that if he had bow and arrow, he could bring her down. She was too skinny to survive a harsh winter, and yet he found something to his liking about that. He imagined her under him, arms and legs in constant motion. She would wrap herself around him, nipping, digging her fingers into his back until the volcano she’d turned him into exploded. She’d absorb his energy, share hers with him, her cries echoing in the distance.

Angry, he forced away the dangerous thought. This was no willing Maklaks maiden. The strange woman wore clothes he’d never seen, her sturdy shoes made from an unknown material. She didn’t belong here, was so stupid that she stood alone and vulnerable on land fought over by Indian and white.

Didn’t belong here? Yes, her bare arms didn’t know what it meant to be assaulted by winter cold and summer heat, and yet she looked around her with wanting and loneliness, her eyes and soft mouth telling him of the turmoil inside her, tapping a like unrest inside him. Had her emotions reached him somehow and pulled him from the place where he believed he would spend eternity?

Why?

Chapter 1

Six months later

Home.

No, not home, but understanding, maybe.

It was going to be a glorious day—hot but unbelievably clean—the kind of day that made a person glad to be alive and put life into perspective. At least it did if that person had a handle on herself. On that thought, Victoria—Tory—Kent opened her car door and stepped out. Although night shadows still covered the land, the birds were awake. Their songs filled the air and made her smile.

This land was so deceptively desolate, miles and miles of blackened rock. When she’d first seen the Lava Beds National Monument of Northern California, her impression had been that the country was a harsh joke, a massive, lifeless testament to the power of volcanic eruption and little more. But it wasn’t lifeless after all. She would have to share it with other visitors and park personnel. At least it was too early for anyone else to be at the parking lot near the site that had been named Captain Jack’s Stronghold, after the rebel Modoc chief who once lived here. For a little while, her only companions would be the deer and birds and antelope and scurrying little animals that somehow found a way to sustain themselves on the pungent brush and scraggly trees that found the lava-strewn earth, if not rich, at least capable of sustaining life.

A distant glint of light caught her attention, pulling her from the persistent and uneasy question of what she was doing here when the opportunity of a lifetime waited on the Oregon coast. Concentrating, she realized that the rising sun had lit distant Mount Shasta. Although it was June, snow still blanketed the magnificent peak. This morning, the snow had taken on a rosy cast, which stood out in stark contrast to the still-dark, still-quieted world she’d entered.

What was it she’d read? That the Modocs who once roamed this land, and who had murdered her great-great-grandfather, considered Shasta sacred. Looking at it now, she understood why.

“Are you still around, spirits?” she muttered softly, not surprised that she’d spoken aloud. Ever since her too-brief visit last winter, the isolated historic landmark had remained on her mind—although haunted might be a more appropriate term.

While at work, she’d managed to keep her reaction to herself, but no one was watching her today. In fact, even her boss, the eminent and famous anthropologist Dr. Richard Grossnickle, didn’t know what she was doing. She’d tell him once she joined him at the Alsea Indian village site, maybe.

After making sure she had her keys with her, she locked her car and started up the narrow paved path that would take her through the stronghold, one of the high points of the monument and where some one hundred and fifty Modoc men, women and children had spent the winter of 1873. She’d taken no more than a half-dozen steps before turning to look back at her car for reassurance. It was the only vehicle in the parking lot, the only hunk of metal and plastic and rubber amid miles and miles of nothing. Behind the car lay a surprisingly smooth grassland and beyond that the faint haze that was Tule Lake. The grasses, she knew, existed because years ago much of the lake had been drained to create farmland out of the rich lake bottom.

Ahead of her—

The land tumbled over on itself, a jumble of hardened lava, hardy sagebrush, surprisingly fragrant bitterbrush, ice-gray rabbitbrush. The plants’ ability to find enough soil for rooting here made her shake her head in wonder. She knew they provided shelter for all kinds of small animals and hoped her presence wouldn’t disturb the creatures.

It probably would. After all, this time of day—fragile dawn—belonged to those who lived and died here, not to intruders like herself. Intruder? If your ancestor had fought and died here, his blood soaking into the earth, did that give you some kind of claim to the land?

Was that why she hadn’t been able to shake it from her mind and had to come back? Because she had some kind of genetic tie to this place?

After a short climb, she found herself at the end of the paved area. Day was emerging in degrees, as if one layer after another was being lifted to reveal more and more detail. From the relative distance of the parking lot, the stronghold had looked like nothing more than a brush-covered rise, but she’d reached the top and was fast learning that depth and distance here obeyed different rules. One minute she was walking on level ground with nothing except weeds to obscure her view. Then, after no more than a dozen or so steps, she’d dropped into a lava-defined gully. The rocky sides trapped her, held her apart from all signs and thoughts of civilization.

There’d been a box filled with pamphlets at the beginning of the trail, and after depositing her twenty-five cents, she’d taken one of them. A wooden post with a white number 1 on it corresponded to a paragraph in the pamphlet. She was standing at the site of what had been a Modoc defense outpost. From strategic places like this one, the Indians had been able to keep an eye on the army. As a result, a fighting force of no more than sixty warriors had held off close to a thousand armed soldiers for five months.

A stronghold. It was aptly named.

As the day’s first warmth reached her, she stopped walking and concentrated so she could experience everything. In her mind, it was that fateful winter. Settlers had been living in the area for years, slowly, irrevocably encroaching on land that had always belonged to the Indians.

A fort had been built some miles away and the Modocs and Klamaths had been forced onto an uneasily shared reservation. Some of the Modocs under the leadership of Captain Jack had fled and taken up residence on the other side of Tule Lake. When the army, charged with recapturing the rebels, attacked one frozen dawn, the Modocs had scrambled into their canoes and paddled across the lake to take refuge here in what they’d called The Land Of Burned Out Fires.

Peace talks had been tried, and tried. Thanks to indecision on the part of the government and opposition from the Modocs, it had taken months to decide who would try to wrangle out some kind of settlement. Her great-great-grandfather, a distinguished veteran of the Civil War and commander of the troops stationed here, had been a member of that commission. On April 11, 1873, General Canby had been killed a few miles away, the only true general to die during the struggle.

Such a simple scenario. Wrongs committed on both sides. Forceful, clashing egos. An impenetrable hiding place. A hellish winter for everyone. Her ancestor’s blood spilled on nearly useless land.

The birds hadn’t stopped their gentle songs. Occasionally, they were interrupted by a crow’s strident call that made her smile. The wind had barely been moving when she arrived, but it was increasing, an uneven push of air that sent the brush and grasses to murmuring. She wondered what it had been like to be surrounded by little more than crows and other birds and wind for five months, to constantly listen for the sounds of the enemy. Thanks to the correspondence between Alfred Canby and Washington officials, she had a fair idea of what that winter had been like for the army troops, and looking at the land now she could understand why so many had deserted.

It hadn’t been that easy for the Modocs. They couldn’t leave.

Something in the sky distracted her. Looking up, she spotted an eagle floating in great, free circles over her. Not for the first time, she thought that birds had an ideal life. If it wasn’t for mealtime, she wouldn’t mind being an eagle. To spend one’s days playing with the wind, drifting high above the earth like a free-spirited, tireless hang glider, unconcerned about taxes, an aging car, job politics… Her contemplation of the eagle became more intense when she realized it was slowly but steadily coming closer. She could now make out the details of its proud white head, imagine its sharp eyes were focused on her. Were there such things as rabid eagles? Surely the creature hadn’t mistaken her for breakfast, had it?

Its circles became tighter, more focused until she had absolutely no doubt that she was what held its attention. Those talons would make short work of her cotton shirt and the flesh beneath. Her car keys were no match against its killing weapons. To be attacked by a bird of prey—

With a scream that sent a bolt of fear through her, it wheeled away, disappearing in a matter of seconds. Still shaken, she waited to see if it would return, but it must have decided that a mouse or snake would taste better. After longer than she cared to admit, she dismissed the bird and its unusual behavior and went back to her history lesson.

Captain Jack, she thought with a grim smile. The Modoc chief had had an Indian name, but she couldn’t remember it. From the pictures she’d seen of him, he looked like a peaceful enough man, but something had snapped inside him and his followers, and they’d gone to war against the United States Army, although she doubted he’d known the sum of what he’d been up against. Still, in 1873, after years of coexistence with whites, the Modocs of his time hadn’t been primitive savages, nothing like the cultures she studied as an anthropologist.

What brought the eagle back to mind she couldn’t say. Maybe because on a subconscious level she’d been asking herself how far the Modocs had come from their prehistoric beliefs. Surely they’d no longer perceived eagles and other creatures as gods.

There was, she admitted, a fine line to be walked between giving primitive people’s beliefs the respect they deserved and not laughing over the notion of coyotes who told tall tales, snakes that were thought to be immortal because they shed their skins, warning children not to harm a frog for fear of causing the closest stream to dry up. Despite six years of studying and working with Dr. Grossnickle, she’d been unable to determine to her satisfaction what had given birth to such legends. Certainly she understood early people’s need to make order out of the uncertainties of their lives, but talking animals or the belief that the Modoc creator went around disguised as an old crone… Well, to each his own. She’d talk the talk; she knew she had to do that if she intended to keep her job. But beyond that…well, let’s get real.

Still, she admitted as she moved on to the next marker, there was something about standing on the actual land in question that made logic and professional dispassion a little hard to hold on to. Thinking of everything the Modocs had lost, she stared at the magnificent nothingness of land that stretched out around her. Except for the trail and occasional markings, the stronghold hadn’t changed.

That’s why she’d come out here before visitors started arriving, so she could more easily capture the essence of that earlier time. She began walking again, a slow gait that hopefully diminished the likelihood of losing her footing. Although it took some doing, she managed to read a little more from the brochure. She was surprised to learn that the naturally fortified stronghold itself was little more than a half mile in diameter. The land for as far as she could see was so awesomely vast and rugged that where the Modocs had entrenched themselves seemed larger than it really was. Back then, Tule Lake had dominated the area to the north while most of the south was barren volcanic rock. The chance of sneaking up on the Modocs—

A sound overhead caused her to again stare at the sky. She spotted what she thought must be the same eagle silhouetted against the blueing sky, but this time it was far enough away that she didn’t feel uneasy. “What do you see up there?” she asked. “Are your eyes keen enough that you can spot the Golden Gate Bridge?”

Looking as if it weighed no more than a feather, the great bird dipped one wing. Sunlight caught the tip and gave her an impression of glistening black. “Forget the Golden Gate. You don’t want to get any closer to civilization than this. And if you stay up there, the two of us are going to get along just fine.”

As if taking her suggestion to heart, the bird floated away. When she looked around, thinking to reorient herself, the stronghold seemed to have lost a little of its definition. It was, she thought, as if night had decided to return. After blinking a few times, she dispelled that possibility, but the wind had picked up and the sound it made coated her thoughts, allowed her to dismiss everything she’d experienced in her life before this moment.

Not only that, she could almost swear she was no longer alone.

There was such a thing as too much solitude, Tory told herself a half hour later. You’d think that a person who could see so far that she was aware of the earth’s curve wouldn’t be looking over her shoulder.

Only, it wasn’t just the aloneness, and she knew it, damn it. Something—someone—was watching her. It could be the eagle, a rabbit, maybe even one of the antelope she understood made their home in the park.

“Say,” she whispered because she didn’t want to disturb the lizard staring at her from a rock. “Whoever you are, I don’t suppose you brought some coffee with you, did you?”

Silence, but then she didn’t really expect any different.

According to the pamphlet, she should be approaching one of the dance rings the Modocs had used during their shamanistic rituals, but because she’d veered off the trail while seeking the best vantage point to study Captain Jack’s wide, shallow cave, it took a little while to orient herself. She’d been right; it was going to be a clean day. Clean and clear and utterly beautiful in the way of a sky unspoiled by pollution. Just the same, she couldn’t help but be a little uneasy.

Grass grew between the large rocks that had been placed in a crude circle over a hundred and twenty years ago. She tried to imagine what the spot looked and sounded like back when the shaman—Curly Headed Doctor, the pamphlet said—strung red rope around the stronghold and then sang and danced through the night to ensure that his magic remain powerful.

A red rope to hold back an army. How simplistic. She’d seen a picture of the shaman and had been surprised by how young and untested he appeared, but apparently most, if not all, of the tribe had believed in him—at least they had until the army trampled his rope.

She sat on one of the rocks and faced into the center. If there’d been someone beside her, their shoulders would have touched, and she didn’t see how there would have been enough room for dancing in the middle if every rock had had an occupant. An incredible bond must have been forged here. All right, there’d been political squabbling, conflicts between Captain Jack and some of the more militant rebels, but on a cold yet peaceful night, surely the leaders had come here with a singleness of thought, a shared dream for freedom.

She rocked forward and rested her elbows on her knees, eyes closed to slits that blurred her vision and freed her from the question of who or what shared this place with her. To belong, to be part of a large clan, to put aside petty differences in order to survive, to have learned the necessity of depending on one another…

How long she’d been sitting here she couldn’t say. She didn’t think it had been more than a couple of minutes, and yet she was surprised by how quickly she’d gone from wondering if she should have brought along a can of Mace to losing herself in sensation.

She was suddenly restless, so uneasy with herself that she wasn’t sure she’d be able to conquer the emotion. It came at her more and more often these days—quiet and yet, rough questions about where her life was heading. She’d felt like that sometimes back in high school when warm spring nights and loud music and a grin from a boy sent her heart spinning out of control. She’d weathered those adolescent emotions, smothered them under work goals and ambition and the excitement of knowing that she and Dr. Grossnickle and the university that employed them were on the brink of the anthropological find of three decades. Colleagues, the press, even the bureaucrats and legal types she’d been butting heads with over excavation rights assumed she spent every waking moment immersed in exploring this primitive civilization.

What they didn’t know about was the search, a goal—or something—she couldn’t define.

She needed hard-driving music, to be behind the wheel of a speeding convertible with the wind screaming through her hair. She needed—all right, she needed a man to quiet her body.

After sucking one lungful of air after another into her, she managed to conquer the worst of her energy, but she knew it would only erupt again unless she started moving. Standing, she reached for the brochure, thinking to continue the history lesson. Then she froze.

There was someone out there—a man. Naked but for a loincloth. He clutched a gleaming black knife in strong fingers, and yet she couldn’t make herself concentrate on the weapon.

A savage. Savage.

The word slid inside her, solid and yet misty like a vivid dream that fades upon awakening. But this was no dream.

She stepped over the rock, freeing herself from the dance ring’s confinement, not so she could run, but because—

Because her legs had decided to walk toward him.

He didn’t move; she would swear to that. And yet he kept changing. It was, she finally decided, the way the sun greeted him, lent light to his dark flesh and made his ebony hair glisten. She couldn’t say how old he was; he stood too far away for her to make out his features. Still, if the truth was in his broad shoulders, the flat plane of his belly, the proud way he held his head, he was a man in his prime.

Prime. Savage. Warrior.

There wasn’t enough air at The Land Of Burned Out Fires. If he’d stolen it, she would soon have to demand he return it to her, but maybe—probably—the fault lay in her.

This wonderfully lonely land had remained locked in the past. She didn’t care why that was, didn’t care whether she ever left it. Somehow—although it was impossible—she’d found a primitive brave, and he was staring at her, and the space between them had become charged.

She moved closer, a skill so complex that it should have been beyond her, because her need to touch him, to look into his eyes, to feel his hands on her, was like an explosion inside her. She should say something, ask him to explain the impossible, but if she spoke, he might evaporate, and she needed to stretch out this moment, enlarge it until it became enough to last a lifetime.

One step, two, three, and still he remained. She could now see that he had a small scar over his right shoulder blade and the fine hairs on his arms and legs were as dark as the back of Captain Jack’s cave. His thighs—the loincloth exposed every inch of them—looked as strong and durable as the lava that dominated the land. Those legs could, she knew, lock a woman between them.

They could take her places only imagined before, awaken a gnawing beast of hunger that could only be filled by passion—raw and unadorned passion.

The air was gone again. She had to fight to breathe. The effort did something to her, snapped something deep inside and reminded her of who and where she was.

This man couldn’t be. He couldn’t!

Chapter 2

Eyes narrowed against the sun, the warrior watched the woman race for her wagon, her car. The urge to bury the ancient knife in her and avenge what she’d done to him was powerful, and yet, now that he’d seen her up close, looked into her eyes, anger and rage had to share space with another emotion.

She’d returned. He wanted to grab her and insist she tell him why. Most of all he’d demand to know whether her presence was what had awakened him.

Belly empty, he cast around for a rabbit or other small animal, but even as he thought he detected a furtive movement, his attention returned to the woman. She’d reached her car, and although she was too far away for him to see anything of her expression, her body language told him a great deal.

She was afraid of him. Even though he was no longer near her, she continued to carry herself as if fear rode deep and full and low inside her. She might call others of her kind to her. If she did, they’d hunt him with powerful weapons and his blood would join that of his ancestors who’d died here. But he didn’t see that as something to avoid. Death, maybe, would bring him the peace he’d known as a small child.

Once again he tried to put his thoughts to finding something to eat before the strangers started swarming over what had once had been his land, but she hadn’t yet left in the fast, loud wagon he’d heard her kind call a car. Until she had, all he could do was watch. She’d stopped running, but probably only because she’d become winded. She now walked as fast as she could, an awkward and jerky movement that used much more energy than it would have if she moved with her hips.

What did he care! Let her break her leg on the ungiving rocks. If she did, the green-clad men and women who were today’s soldiers would come and bear her away. Except then she’d tell them what had made her run, and his uneasy peace would be shattered.

She’d reached her car. It took her a long time to open the door, and he guessed her fingers shook so that the task was nearly impossible. It was too late to bury his knife in her back and silence her. She’d gotten away!

A sound like a bear’s deep growl escaped his throat. Turning his back on her, he stepped around the dance ring and stood where she’d been just before she ran. What fools the strangers were! Those who didn’t laugh and whoop like stupid children, walked slowly, reverently around it. At first he’d been mystified by their actions but finally he’d decided that they must think this weed-clogged circle of rocks was something to be revered. It had been, once. But the enemy had defiled it with their presence and Cho-ocks’s magic had long ago left.

Left like everything of his time except for him.

Another growl threatened to break free, but knowing it would only tear through him like what he’d felt at his son’s death, he stifled the sound. Looking down, he imagined the exact spot where the woman had placed her boots.

She was responsible! She had brought him to this time he didn’t want, where he didn’t belong! Thinking to grind her prints into nothing, he lifted his foot, but before he could lower it, something on a nearby bush caught his attention. It was a single hair, long and rich, the dark color of a wolf in his prime. Freeing it from the bush, he held it between thumb and forefinger. Despite his roughened fingertips, what he felt reminded him of goose down. The hair belonged to the enemy-woman. In the hands of a powerful shaman, it could be used to bring sickness and maybe death to whoever it belonged to.

He’d been wrong to do nothing but follow a warrior’s way. Cho-ocks had been willing to teach him his shaman’s magic. He should have stilled his impatience and anger against the enemy and listened and learned. If he had, he could…

Soft. Soft as the down on a newborn chick. Touched with light from the sun. He brought the hair close to his nose and inhaled, but couldn’t smell anything. His need to understand what had happened to his world had brought him close to a number of women, always without their knowledge. He hated the way they smelled, their scents so strong that they overpowered the sage even. But this woman hadn’t covered her body with anything that assaulted his nostrils, and he liked that.

Enemy-woman.

She had a name. And she would tell him what spell she’d cast over him. Once he understood, he would…

Eyes big and dark. A soft and gentle mouth. Long, strong arms and legs. Slender waist and hips that flared to accommodate a child placed within her. Hips and breasts made to taunt a man. To remind him of how long he’d slept alone.

Breathing more rapidly than she should have a need to, Tory sped around yet another turn. The landscape whipped behind her on both sides, but although she’d come out here for the express purpose of observing the land before she had to share it with other visitors, she couldn’t put her mind to concentrating on it.

She’d seen—what? A Modoc warrior? She’d been asking herself the same stupid question for the past fifteen minutes until she was sick to death of it. Unfortunately, she still hadn’t come up with an answer. At least now that she was no longer staring into eyes as dark as night, the stark and unreasoning fear that had sent her running had begun to fade.

It must be some kind of joke.

Slamming her fist into the steering wheel, she again ordered the stupid words to stop ramming around inside her. Hand stinging, she again tried to find a logical explanation. Unfortunately, as before, her mind didn’t want anything to do with logic.

He’d looked so innately primitive, not at all like those so-called savages Hollywood slapped makeup on. She’d never been able to watch Westerns because the Indians looked so phony. Yes, she supposed that a lot of them actually were Native Americans, but they hadn’t belonged in the wilderness they’d been thrust into for the sake of the movie. Despite war paint and bows and arrows and little more than loincloths, there’d been something self-conscious about the way they presented themselves.

This man, this warrior, was as natural a part of his rugged environment as the eagle had been. That was what she couldn’t forget. That, and something in those ebony eyes that had found and ignited a part of her she hadn’t known existed.

A park-service vehicle coming from the opposite direction shocked her back to the here and now and away from absolutely insane images of herself willingly following the Indian back to wherever he’d come from. She thought about trying to flag the park employee down, but what would she say? That she’d had a hallucination about a nearly naked, absolute hunk of a man and wanted to know if it was a common occurrence around here?

There must be some kind of an explanation, logical and practical, so clear-cut that she’d be embarrassed for not having thought of it before.

Yeah, right.

After traveling another ten miles, she reached park headquarters, only then realizing what she’d done. She’d intended to spend the day poking around the lava beds. Instead, tail tucked between her legs, she’d hightailed it for civilization. Angry with herself and yet unable to come up with the fortitude necessary for turning around and going back the way she’d come, she eased her vehicle into one of the parking slots. The rustic cabin she’d rented was not quite a mile away, isolated but accessible via a well-maintained footpath. It came equipped with a two-way radio to be used in case of an emergency.

Some of the park personnel lived here year-round. While wandering around at dusk last night, she’d happened upon the paved road leading from headquarters to the small collection of houses within shouting distance of where she now sat. Although she hadn’t stayed around the residential area because she didn’t want to invade anyone’s privacy, she remembered seeing a couple of satellite dishes. Two girls riding bikes had waved at her, and when she’d asked them, they explained that they went to school in the town of Tulelake, which was “only” thirty miles away. They were on their way to the nearby campground to see if there were any kids their age staying there tonight. The girls were friendly and eager to talk; they’d argued with each other over whether they’d want to stay at the campground or where she was. One had always wanted to spend a night at the cabin. The other wasn’t interested because it didn’t have a TV or electricity and what would she do once it got dark.

Tory hadn’t bothered to tell them that once she got to the Oregon coast, she expected to spend months camping out without electricity. Because it hadn’t been the first time, she hadn’t had any trouble falling asleep last night with nothing except coyotes and owls to keep her company. Tonight, however—

She deliberately hadn’t told anyone of her ties to one of the central players during the Modoc War because she didn’t want to risk someone deciding to exploit that. Still, in the back of her mind rode the question of whether she’d thought she’d seen a survivor of that time because her great-great-grandfather had died here.

Like that makes any kind of sense.

“Will you stop it!” she muttered, and got out of the car. A strong breeze brought with it a hint of the day’s heat, the pungent scent of sage and lava and an almost overwhelming desire to walk away from this spot of civilization and out into the wilderness where he might find her again.

When she checked in yesterday, the parking lot had been filled with dusty, crammed vans, cars with out-of-state licenses, even a group of senior citizens on expensive motorcycles. This morning, hers was the only vehicle not belonging to park employees. She was surprised to see them here. Shouldn’t they be out doing whatever it was they did to maintain the lava beds?

She opened the door to the small visitors’ center and looked around. There was a small collection of Modoc artifacts behind glass on one wall, a large, rough-finished wooden canoe against another wall, shelves filled with a display of books, pamphlets and postcards. A sign above the information desk, unmanned at the moment, informed her that anyone interested in exploring the caves that honeycombed the area were encouraged to sign in here so they could be issued hard hats and flashlights.

There was nothing flashy about the room, no plastic trinkets. Still, it helped her put her incredible experience behind her. This was a place of telephones and probably even fax machines. There’d be computers somewhere, a park director whose credentials would put hers to shame. None of the dedicated professionals who worked and lived here would have seen a mirage from another time.

And neither had she.

Then what did you see?

Someone had played a joke on her—that’s what it had been. An elaborate and very good hoax.

Try telling your nervous system that.

Hoping to squelch her thoughts, she opened her mouth to call out when she heard voices coming from somewhere behind the information desk. She guessed there was a room back there. Maybe park personnel were having a meeting. If that was the case, she didn’t want to disturb them. Besides, what would she say?

A tiny tentacle of fear inched down her back, causing her to look toward one of the little windows. All she could see were weather-stunted trees and dark lava rocks—nothing to be afraid of.

What was she doing here?

Instead of forcing herself to answer what she hoped to accomplish by taking shelter under a roof when she should be out looking for a piece of her roots, she picked up one of the books about the Modoc War. She’d done no more than read the back blurb when the sound of raised voices caught her attention. Before she could decide what to do, she heard a door being opened. The voices became more distinct.

“People will see right through it. You can’t get away with something that cornball in this day and age. They’ll laugh us right out of the water.”

“No, they won’t. People love the unexplained. Besides, you already admitted you don’t have a better suggestion.”

“Only because I haven’t had time to come up with one.”

“The hell you haven’t. We’ve been staring at a budget shortfall for the better part of a year now. That’s what I’m here for. Why you’re being so…”

Two men came around the divider that separated the public area from the rest of the building. They stared at her, their conversation trailing off to nothing. One of them, a tall, balding man probably in his late fifties, wore the standard green uniform and a name tag that identified him as Robert Casewell, acting director. Tory guessed that his had been the deeper of the two voices, the one who’d told the other that his suggestion wouldn’t hold water. The other man, closer to her age, wore civilian clothing. If he’d been sent here to deal with the budget in some way, he apparently wasn’t a park employee.

“I’m sorry,” she said when the two men continued to stare at her. “I should have let someone know I was here, but I didn’t want to disturb anyone.”

“It’s all right,” Robert Casewell said. “The meeting’s over.” He jerked his head at the other man. “You and I need to get together, Fenton. Come up with something that makes sense.”

“What I proposed makes sense. You just need to open up your thinking.”

The director muttered something under his breath, nodded at Tory, then walked out the door. Not sure what she was supposed to do now, she gave Fenton a tentative smile. “I heard a little,” she admitted. “I know what you mean about budget problems. They never seem to go away, do they?”

“They will if I can get people to listen.” Fenton, who was maybe three inches taller than her, with the slightest bit of thickening around his waist and a thatch of windblown hair, smiled down at her. “I’m not a walking encyclopedia about the lava beds, but if you’ve got a question, maybe I can answer it.”

Can you? Can you tell me whether I really saw a man who must be at least a hundred and fifty years old, who looked at me with the most compelling eyes I’ve ever seen? Stammering a little and hating herself for sounding half-bright, she explained that she’d been out on her own this morning but had decided she needed a map and game plan so she wouldn’t risk getting lost. “I love hiking, but I have the suspicion I could get disoriented in short order around here. It’s amazing. From a distance everything looks so level, but once you really look at it, you see all those hills and valleys.”

“Yeah, there’s enough of them, all right. You’re here alone?”

Wary in the way of a woman who has learned to navigate the world on her own, she simply shrugged. She should grab a map, ask a couple of questions and get out of here, but after what she’d experienced this morning, a roof felt inordinately comforting.

“So am I,” Fenton was saying. He introduced himself as Fenton James and she felt obliged to introduce herself in turn. When he stuck out his hand, she did the same. “I’ve been here about three weeks now,” he said. “I thought everyone came as part of a group, mostly families on vacation, sometimes college students or history buffs. Couldn’t you find anyone who wanted to stare at nothing with you?”

Something about Fenton’s tone didn’t sit right with her, but she didn’t have time to analyze what that was. “I’m on my way to a job,” she said, dismissing the understatement. “I just have time for a day or two of poking around.”

“Two days. Most people are in and out in an afternoon, unless they take in the caves, which I can’t understand why. Where’s this job of yours? I can’t imagine anyone having to go through here to get to a job.”

Why Fenton cared what she was up to remained beyond her. However, talking to the man had already taken her thoughts miles away from what she’d seen, or thought she’d seen, earlier. Even if he was trying to hit on her, setting him straight gave her something to do. Besides, he said he’d been at the lava beds for three weeks. If he’d noticed something unexplainable, maybe they could compare reactions. But she doubted that he’d been left feeling as if a huge chunk of what she thought of as her civilized nature had been sucked from him. Keeping the telling as brief as possible, she let him know she was part of the team selected to study some Native American ruins on the Oregon coast.

“How did you accomplish that?” he exclaimed. “My God, that’s the find of the century! The opportunity for—what are you? An archaeologist?”

“Anthropologist.”

“Whatever.” He shrugged. “I never understood the difference.”

She could have told him that an archaeologist dealt with the physical world while anthropologists concerned themselves with things social and spiritual, but what was the point? “You’ve heard of the Alsea discovery, I take it,” she said instead.

“Who hasn’t? I’d give anything to be part of it. The chance for making one’s mark, well—say, maybe you can explain something for me.” He rested his arm on the counter, the gesture bringing him a little closer to her. Although the air still held a high desert morning chill, she thought she caught a whiff of perspiration. “The site was discovered over a year ago. What’s the holdup? I mean, I’d think everyone would be hot to trot getting their discoveries written up in the press and all. There’s Pulitzer Prize potential there, you know.”

Maybe. Maybe not. At the moment that was a moot point.

“What’s going on?” he persisted. “Why isn’t everyone up to their eye teeth in pottery and weapons?”

“It isn’t that easy.” The sun had reached the window to her left, inviting her to come outside and experience the morning. If she did, would she find only other visitors, or would a look at the horizon reveal someone who couldn’t possibly exist? “There’s an incredible amount of red tape.”

“I suppose so. What is it, the government wanting a piece of the pie?”

There’d been concern about impact on the environment expressed by both state and federal agencies, as well as more than one politician trying to make a name for himself. And the Oregon Indian Council had insisted that they, not university staff, should be responsible for safeguarding artifacts, only they weren’t interested in the artifacts so much as protecting what they insisted was sacred ground. Once, the strip of land between ocean and mountains had been sacred to the Alsea Indians, but the culture that had lived there no longer existed. That was what she’d argued alongside Dr. Grossnickle during three trips to Washington, D.C. Finally, after more legal maneuvering than she wanted to think about, the Indians’ claim had been dismissed.

Things were now clear for work to begin. That’s what she told Fenton, the explanation as brief as she could make it.

“At least we don’t get much of that around here.” He gave her what he must think was a conspiratorial smile. “There’s an Indian council, but they don’t care what we do here. At least if they don’t like something, I haven’t heard about it. Not that I’d have time to deal with any opposition. I’ve got my hands full trying to put this park on solid financial footing.”

She listened with half an ear while Fenton explained that because of governmental cutbacks, the park was hard-pressed to match last year’s budget, let alone plan for the future. He’d left a “choice position”—his words—with a San Francisco bank to spearhead a budget drive here, but so far all he’d met with was opposition. “Casewell calls my plan manipulation. Deception. I call it a stroke of genius. You tell me, what’s wrong with capitalizing on a few ghost sightings?”

She’d been glancing at the window, both eager to be outside and grateful for the room and its proof of normalcy. Now Felton’s comment captured her full attention. “Ghost sightings?”

He shrugged, his gesture casual when she was on edge. “Spirits. Ghosts. Whatever you want to call them.” Although they were alone, he leaned closer and would have whispered in her ear if she hadn’t pulled back. “I’ll tell you because you’re in the same business, so to speak. Most people, they come here, take a look around and say how amazing it is that the Indians held out so long, then go on their way. But some of them, particularly those who walk around Captain Jack’s Stronghold, say they feel something there.”

“Something?”

Again he shrugged his maddening shrug. “You tell me. I’ve never felt anything, but I’d have to be fourteen kinds of a fool not to realize there’s a potential in this. The way I look at it, people with overactive imaginations stand where the Indians stood and they convince themselves that the Modocs left something of themselves behind when they were hauled off to the reservation. I think folks want to believe that. That way they don’t have to feel guilty about what was done to the Indians.”

“Maybe.” She hedged. “But you’re not talking about something that actually exists.” Or does he? “How can you capitalize on that?”

He gave her what she thought might be a sly wink. “The power of suggestion. A few well-placed leaks to the press and we’ll have people swarming here, either because they want to believe, or because they’re determined to disprove the rumors.”

“But when they don’t see anything, it won’t take long for them to decide they’ve been duped.”

“You’re assuming they’ll come away disappointed. But if they don’t—”

“What are you saying?”

For such a brief period of time that she might have imagined it, Fenton lost his self-confident air; she could almost swear he’d started to glance out the window. Then, smiling deliberately, he briefly touched his hand to her shoulder. “I’m telling you this because, like I said, we’re in the same business. We’re both looking to make a name for ourselves, you through what you can gain from an extinct culture, me from what it’ll do to my career if I turn this park around. Anything and everything is open to different interpretations. For example, those who have been working here for years either count themselves tuned into something—shall we call it otherworldly?—or they don’t. Whatever it is, none of them quite know what to make of what’s been happening lately.”

“What are you talking about?”

“You’ve got me. I’m not the one going around admitting I’ve been seeing things, but there have been sightings.”

When he stood there staring at her, she nearly screamed at him to tell her what he was talking about. But there was no way she was going to let him think she believed in this ghost or spirit or whatever he was rattling on about; neither would she do anything to discourage him from talking. Finally he shrugged and moved to the window and looked out as if assuring himself that their conversation would remain private. “What gave me the idea of capitalizing on things is that all of these sightings, or whatever you want to call them, are the same.”

“Are they?”

“Yep. A warrior, brave, whatever you want to call him.”

“A warrior?” She thought her voice squeaked a little at the end, hoped it didn’t.

“Good-looking stud, at least that’s what some say. Damn imposing, too. He’s always way off in the distance so no one can ask him what the heck he’s up to, but those who do see him are convinced he’s real.”

Convinced he’s real. “You say he’s always a long way away.”

“A real shy fellow. Not that I mind, because that keeps the mystery going.” He ended that with another of his winks, this one lasting longer and punctuated by a slight upward turn of his mouth. “That’s what I’m trying to get the director to understand. We don’t have to come up with anything folks can either prove or disprove. In fact, that’s the last thing we want. But if every once in a while people see something or someone they can’t explain, that’ll keep them coming.”

Could Fenton have already put his plan into operation? Was that what she’d seen, nothing more than some actor Fenton James had hired to perpetrate this elaborate hoax of his? If that’s what it was—and she wanted the explanation to be that simple—she could tell Fenton that the actor was very, very good.

“It’s certainly different from anything I’ve heard,” she said and moved away as if to leave.

“It’s more than that. It’s a stroke of genius, if it works.”

“If it works? It sounds as if you’ve done more than just presented the idea to the director.”

“Maybe I have. Maybe I have.”

Chapter 3

Five minutes later, Tory had finally extricated herself from the talkative Fenton and had started toward her cabin. By now people were beginning to arrive at park headquarters, their voices following her until she’d traveled a good quarter of the way. If the heat kept increasing, she’d have to change to shorts before going out again. She should have brought her camera this morning; she wouldn’t make that same mistake again because—

Biting the inside of her mouth, she stopped the errant thought. She’d been about to tell herself that a camera was absolutely necessary if she was going to prove the existence of a ghostly warrior for all concerned when there was no such thing.

By effort of will, she forced her thoughts on nothing more complicated than the best place to search for ground squirrels and other scurrying creatures. Looking around, she became aware of her isolation in a way she hadn’t been last night. True, she could see the faint jet trail left behind by a plane, and it was a simple matter to get in touch with someone via the walkie-talkie at the cabin, but she doubted that anyone would hear if she screamed.

Scream? Why would she do that? Hadn’t she asked for the remote cabin because she wanted a little time with her own company, a welcome change of pace from the hectic meetings and yet more meetings?

After unlocking her door, she stepped inside the single room. She’d left her small duffel bag on the couch because there didn’t seem to be much purpose in settling in if she was only going to be here two nights. Thinking to change into shorts, she started rummaging through her belongings. She stopped when she came across the folder filled with newspaper clippings. Although her own role in the Alsea project was essentially a supportive one, she’d been quoted numerous times and had had her picture taken on more than one occasion. Dr. Grossnickle teased her that she was robbing him of top billing, but that wasn’t true and they both knew it. Still—

Frowning, she opened the folder and studied the most recent articles. Not only was she photographed alongside Dr. Grossnickle, but two paragraphs of the accompanying article were about her successful effort to discredit the Oregon Indian Council’s claim that they alone had the right to excavate and record. Not only was the article one of the most accurate ones that had been written about the project, it had appeared on the front page of a recent Oregonian newspaper. If Fenton James had read the article and seen her name on the guest register and decided—

Decided what? To convince a high-profile anthropologist that something unexplained lurked around the lava beds? Taking the argument as far as it would go, he had struck up a conversation with her and immediately introduced the subject of ghosts or spirits or whatever he wanted to call them.

But he’d also told her straight out that he was trying to come up with a way to capitalize on people’s overactive imaginations and mine them for the park’s financial benefit. There’d been nothing veiled about his intentions.

Warned by the threat of a headache, she turned her thoughts to the less weighty question of whether to stay with boots or change into more comfortable shoes for her next trek into the wilderness. When she started unlacing her boots, she told herself it was not because she could run faster in tennis shoes.

It was dark by the time Tory returned to her cabin, and she needed to use a flashlight to find her way home. Throughout a long and eventful day, she’d gone through three rolls of film while documenting the park’s wildlife and had eaten both lunch and dinner with vacationers who’d insisted she share burgers and hot dogs with them. True, she hadn’t put up much of an argument when the invitations were offered. It wasn’t that she was a great fan of stale buns and wilted lettuce, but being around people kept her from thinking about that morning. And if there’d been times, like when she was trying to get close enough to capture a small herd of antelope in her telephoto lens, when she felt as if she were being watched, she’d chalked it up to that overactive imagination of hers.

At least she tried to; only now, surrounded by night and alone with her thoughts, she couldn’t shake the suspicion—all right, the conviction—that something, or someone, had had his eye on her.

Warrior. Although she barely whispered the word, it took on a life of its own, existed beside her in the small, kerosene-lit cabin, floated just beyond the two windows.

Warrior—a man willing to give up his life for freedom.

Unexpected emotion touched her, but she didn’t try to argue it away with twentieth-century logic. Once, men who answered to no name except “warrior” had roamed this land; that evocative word had spoken of what lived in their hearts.

She’d seen their land today, at least what had once been theirs. The past year of her life had been taken up with one legal and political maneuver after another, all of it aimed at unlocking the key to a way of life that no longer existed. Consumed by those documents and studies and strategies and jockeying for position, she’d forgotten to take the time to focus on the actual people who had once lived the life she was so determined to record.

But here at The Land Of Burned Out Fires not enough had changed. Although the wolves and grizzlies were gone, the deer and antelope that once sustained the Modocs still roamed free. The eagles they had turned to for guidance continued to soar through an unspoiled sky. And because ancient volcanoes had rendered it inhospitable to so-called progress, most of the land remained as it had always been. Only the Modocs had left.

Feeling a little overwhelmed, she turned on the battery-controlled radio and chose an all-news station. While she did what cleaning up she could, she caught up on the outside world. By the time she changed to an easy-listening station, she’d gotten back in touch with what she’d long believed herself to be—an up-and-coming cultural anthropologist with more than thirty years of productivity ahead of her. Sentiment didn’t get the job done.

She’d intended to do a little reading, fiction for a change of pace, but had read no more than five pages before hours of walking and fresh air caught up with her. She turned off the radio and climbed into the double bed with its sagging mattress. An owl kept hooting. She heard what seemed like a thousand crickets, and if she listened carefully, she caught what must be a few frogs somewhere in the sound. Just before she fell asleep, she asked herself when she’d last heard nothing except the sounds of nature. She couldn’t remember.

He came into her dream, a whispering presence, heat and weight. She was standing in the middle of a ring of rocks, but this time there were no weeds obscuring the dance area. A sound that was part crickets and owls and frogs and part something else spread over the night breeze like music from an ageless source. Bare toes digging into the sparse soil, she lifted her head so she could pull the incredibly clean air deep into her lungs. She felt her hair sliding over her shoulders and realized with no sense of shock that she was naked.

He walked toward her. This man, this warrior, wore no more than she did, and yet there was nothing vulnerable about his body. He strode out of the desert as if pride were as vital a part of him as the blood coursing through his veins. His mouth, firm and yet strangely gentle, briefly held her attention and kept her from losing her sanity in the rest of what he was. If he hated her for intruding on his land and his ancestors’ land, his mouth gave nothing of that away. Although her need to take in his entire body and commit it to memory was all but overpowering, she deliberately turned her attention to his eyes.

His fathomless eyes.

She felt herself begin to shake, knew her reaction had nothing to do with cold. The moon emerged in the space of a heartbeat. It bathed the warrior with white-silver rays, feathers of light that slowly and sensually revealed muscle and bone, strength and power. Still, she couldn’t stop staring into his eyes.

They were black. More than black, they seemed to have been alive forever and born at the earth’s core. She wondered if he had his grandfather’s eyes, maybe the eyes of the first Modoc to walk this land. In them she saw generations of a proud and resourceful people who understood the seasons and land and sky in a way that had been lost. His mind held the knowledge to gather and hunt throughout the summer so there would be enough to sustain the tribe through the harshest winter. His eyes knew to scan the horizon for the first glimpse of the winter birds that came to the vast waterways.

This warrior with his war-hardened body had hands made for hunting and fighting, for wrestling what he needed for life from land that offered nothing to more civilized people. Although they now hung along his naked thighs, the fingers curving in slightly, tendons standing out in stark relief beneath deeply tanned flesh, she imagined them cradling a child.

What would those hands feel like on her?

Made breathless by the question, she tried to step outside the dance ring, but the rocks expanded until she was trapped within the walls they’d become. Despite that, she could still see him and shrank a little from a gaze that told her he had the power to control these hard stones. She gaped in amazement and yet acceptance when he used his powerful hands to push one boulder aside so he could step inside.

She couldn’t take her eyes off his thighs; a dusting of black hair draped flesh that had known years of heat and cold and physical life. Beneath the sheltering skin lived muscle and bone. His calves and ankles and feet were like the rocks that held her, made for eternity. She saw in them the runner he must be, the tireless hunter, protector of women and children.

He hadn’t said a word. Still, she knew what had brought him here. The answer lay in the way he used his body, the arrogant strength of him, the blatant sexuality. Although she shrank from him, at the center of her being she wanted what he was. She faced the challenge and danger, the volcano. Their coupling would be as rough and wild as the land he called home. There’d be no gentle whispers, no lengthy foreplay. Instead, he would take what he needed from her, and she would do the same to him. Again and again until her strength gave out.

He lay on his back on his bear-pelt bed. Since awakening—he could think of nothing else to call it—he’d cleared the brush from the slit of an opening above him. Although it was too narrow for him to get his body through or give the enemy access, it allowed enough sunlight to enter during the day that he could easily study the countless etchings that were his people’s history. At night, especially when the moon was full, the cave took on a silver cast.

Staring at the opening, he tried to imagine how the land his people called The Smiles Of God had looked when it was painted in the colors the creator had used to bless the moon. But although he gave thanks to Kumookumts for his generous gift to the Maklaks, he couldn’t keep his thoughts on what the world must have been like when Kumookumts was creating it.

The woman filled him. He’d watched her today. Often her car—how he hated the harsh word—took her far from where he was, but she seemed to have no purpose to her wanderings, and several times came close enough that he could truly study her. Like so many of her kind, she carried that thing they called a camera. He would like to know what they did with their cameras once they were done pointing them. At least they didn’t make a noise like a gun, and he guessed they weren’t weapons because they often pointed them at each other.

She’d come here alone. He’d seen loners before, but there was something about her that made her stand out from the others. He’d tried to tell himself it was because he held her responsible for his awakening, but tonight, with Owl foretelling of death and his body restless with his man-need, he knew it was more than that.

He wanted her. He’d been awake for six moons and looked at women with lust and then acknowledged that he couldn’t have them. He’d spent his lust-need by running until his lungs screamed. But what he felt for her was different. Like the power of a volcano, it held him in its fiery grasp and warned him that if he didn’t run until his legs gave out, he might take her. If he did, she would alert the army men and they would kill him.

Was that Owl’s warning? That his need for this woman would mean the end to him?

A growl of anguish rolled up from deep inside him and pushed its way past his lips. Shaking his head, he tried to deny the depth of his craving, but it was no good. He’d had a wife, a woman chosen by his family because of her social standing in the clan. Although she’d been older than him with interest in little more than digging camas bulbs and drying and storing them for winter, she’d let him climb atop her and he’d spent his energy inside her. She’d given him his son. For that he would always be grateful to her.

But she was dead and energy fed upon him the way lightning-born fire feeds upon trees and brush.

When another cry threatened to find freedom, he shoved himself into a sitting position. The moonlight now slid over his head and shoulders, carved his legs in shadowy relief. Gripping a calf, he thought about the great distance he’d walked today, not hunting as he should have, but searching for the woman again.

She carried herself as few of the enemy did. Instead of lumbering like a grass-fattened cow, she walked with an ease that drew reluctant admiration from him. She must spend much of her life, not in a small, cramped house, but where her legs could find exercise. She was tall, slender. Her hair flowed long and straight and dark down her back; the wind loved to play with it. He wondered where she’d come from, where she would go when her time here was done. He wondered what had brought her here. Most of all he asked himself what she’d thought when he showed himself to her.

She’d known he was watching her today. He’d seen the truth in the way she looked around, the wariness in her bear-brown eyes. After spending the morning pointing her camera at anything that moved, she’d joined some of the enemy. Even when she was surrounded by them, there were times when she scanned the horizon, and although he was so far away that he couldn’t read the truth in her gaze, he’d sensed it in what her body said to him.

Her body, her hated woman’s body.

He flopped back on his pelt but a moment later scrambled to his feet and strode to the nearest wall. Although it lay in complete shadow, he placed his hand flat over a drawing of men herding elk into a brush-and-rope enclosure. When the settlers came bringing their hungry cattle with them, the elk had fled to the mountains and there had no longer been a use for the enclosures. Still, this drawing, like others of Eagle and Bear and Frog and Weasel, of generations of Maklaks life and ways, remained. As long as they did, as long as he devoted himself to their care and protection, he wouldn’t be alone.

Guided by instinct, he ran his hand over his people’s entire history, ending with the winter when the army burned a small village and forced them to take shelter in caves under land capable of sustaining only rabbits and mice. The men, himself included, had searched for food to fill their families’ bellies and when, in desperation, they’d killed some of the enemy’s cattle, they’d known they were doing something that would never be forgiven. There were no drawings of that because what today’s enemy called Captain Jack’s Stronghold was far from this sacred place. There was only what he’d created last winter—proof that the Maklaks weren’t all gone after all. He remained.

Alone.

She should have come to Canby’s Cross yesterday. Loaded down with fresh film and a container of water, Tory left her car at yet another of the areas designated for vehicles. As she’d done yesterday, she’d chosen early morning so she could absorb the area’s essence without interference from her fellow travelers. Yesterday, compulsively taking pictures and finding people to talk to, she’d kept this particular site at the back of her mind. However, as she was waking this morning, she decided to make coming here the first order of business. After all, this was why she’d come to the lava beds, and activity, particularly this activity, should bury last night’s dream.

Maybe.

It took no more than a couple of minutes to walk the short distance to a large white cross designating where General Canby, her ancestor, had lost his life. She stood looking up at it, reaching out with her senses for something of the man. Out of the corner of her eye, she spotted distant Mount Shasta, the rising sun painting it gold and red. She became aware of closer landmarks, such as the rocky outcropping to her right, where armed Modocs had hidden while peace talks took place in the flimsy tent General Canby and the other peace commissioners had set up.

The army’s headquarters, a hastily erected tent city, was several miles away. Even farther away was Captain Jack’s Stronghold. From what she understood, the site where she now stood had been chosen because it had been seen by both sides as a neutral location.

But appearances were deceptive. The land lay in desolation all around her, perfect for friend and foe alike to conceal themselves while the principals argued and postured and tried to find grounds for compromise.

It hadn’t worked. The Modocs, led by their chief, Captain Jack, and the young killer, Hooker Jim, had ambushed the whites. In a matter of minutes her great-great-grandfather and a minister had been murdered, and former Indian superintendent Alfred Meacham left for dead.

Not sure of her emotions, Tory turned in a slow, contemplative circle, trying to imagine what the general had seen and felt during the last morning of his life. She couldn’t recall when she’d first heard of his role in history. As a child, she’d thought that being killed during an Indian war was a noble way to die. As she grew older, she occasionally thought of him with a sense of sadness because he hadn’t lived to see his grandchildren. But most of the time he never entered her mind. Standing here now, she knew he would always remain a part of her.

Although she’d brought her camera with her, it dangled from her fingers. Taking a picture would reduce the experience to something one-dimensional when she wanted to keep her senses alive and alert.

Once again she turned to take in her surroundings, this time not so she could gain a greater perspective on her ancestor, but because that feeling had returned.

The wind blew across the grasses and flattened them until they reminded her of a vast gray carpet. Dark lava rocks punctured the carpet and created the only contrast in color. A faint gray haze coated the sky and made it difficult for her to gauge the height of the hills surrounding Canby’s Cross. Still, driven by something she didn’t quite understand, she imagined she could hear the impatient sounds of waiting horses, the clang of weapons, men’s angry or nervous voices.

And through it all she knew she was being watched.

Chapter 4

Crouched behind a boulder, he watched the young woman run her hand over the white cross. When he’d first seen her car, he thought she might be leaving. If she did, he would be able to dismiss her from his mind, his thoughts, and think only of staying alive and safeguarding his people’s legacy. If she did, he would never know what she smelled like, sounded like, felt like under him. Never know her name, or why his life had been linked with hers.

She hadn’t left. Instead, she’d come to where the army leader had lost his life. More of the enemy than he could count had walked to the cross to aim their cameras at it, but she was simply standing beneath it, alone, looking sad and cautious, her eyes taking in her surroundings.

She sensed he was here. Everything about the way she moved and looked told him that. He could walk away from her, leave her with nothing except her suspicions. Or he could approach her and see if she again ran in terror.

Instead, he simply watched and absorbed and learned as she crouched at the cross’s base and ran her fingers over the dried grasses growing there. She looked, he thought, almost as he must when he touched his son’s blanket. Knowing that twisted his heart in a way he didn’t want. She was the enemy. It was his right to hate her. But how does a man hate a woman who has crawled into his dreams?

Confused, he moved a little closer so he could study her features without being watched in return. As he did, she sprang to her feet and looked warily in all directions, her long, straight, shiny hair floating on a breeze. She was like others of her kind, stupid in the ways of the wilderness. If she had spent her life hunting, she would know to watch for birds or rabbits frightened from their hiding places. The birds and small creatures always told when something dangerous was about.

Still, he didn’t ridicule her for her lack of knowledge; her body’s language told him that she sensed something few did. Yes, many came here, but instead of letting the land tell them what had happened that cold morning, they read the talking leaves they’d brought with them or the plaques that had been placed in the ground back where they left their cars. As a consequence, they knew nothing.

She understood that yesterday waited in the wind, and for that he admired her. He wondered what she heard, whether everything was being revealed to her or whether she knew only the army’s side. For her to truly understand this haunted place, she needed to hear the beating of Maklaks’ hearts, feel their fear and anger. There was only one way she could know all that; only one person who could tell her—him. In his mind he imagined himself looking into her soft, dark eyes while his words brought his people back to life.

What was he thinking? She was evil! Muscles taut, he touched his hand to the knife strapped to his waist.

He’d been here that long-ago day, a silent and somber shadow among other shadows that had come to watch this meeting between his chief and the army leaders. Keintepoos had had no faith in the words the army men spoke because those men were ruled by their leaders who lived far away and made decisions about things they didn’t understand, who hated and feared the Maklaks, who they had never shared meat with. His voice hard with anger and frustration, Keintepoos had agreed with the shaman Cho-ocks and the killer Ha-kar-Jim that if the army lost their leader, the others would flee in disarray. That was why Keintepoos had killed the army man, but instead of going back to where they’d come from, the army’s strength had grown until there was no escaping them.

Why did today’s enemy grieve over the army man’s death? General Canby was one of those who’d helped bring destruction to the People.

The woman was still looking for him, her attention split between the cross and whatever she was trying to find in the horizon. With her every movement, his awareness of her grew, until it was as if she stood beside him, her hand extended to him in invitation and challenge. He felt his body weakening, knew that if she placed her fingers on his flesh, he would forget everything except his need for her.

Sucking in sage-sweet air, he gripped his lower thigh with all the strength in his fingers until hunger for her was replaced by pain. Still, he knew that once the pain was gone, she would again crawl inside him. For a moment of awful and total weakness, he wanted nothing else in life.

Then, because he was a warrior in a world where it was a lonely thing to be a warrior, he pulled hatred from deep inside him and fed upon it.

“Blaiwas! Eagle! Hear my cry. I seek your wisdom. Should the woman live?”

Although he scanned the sky, he saw nothing. Again he sent out a plea, secure in the knowledge that the wind pushed his words behind him where she couldn’t hear. “Blaiwas. Eagle. You are my spirit and the truth lives within you. This woman beats upon my body with fists I do not understand. I must know. The owl call I heard last night. Is it the cry of a mortal bird or Owl himself sending his warning? Am I to die? Is she?”

The sky remained clean and clear, hazed only slightly by the morning, but as he continued to study it, he saw a small, dark and familiar shape. Closer and closer the shape came until he had no doubt that his spirit, Eagle, had answered. Directly overhead now, Eagle rode the wind in large, graceful circles until it was so close that he easily made out the knife-like tips of its talons. It flew with its head lowered, not because it sought food but because it had locked its eyes on him.

Eagle. Blaiwas.

Aware that the woman had taken note of Eagle, he sent out a silent message of thanks that his spirit had answered his call, then repeated his question. As if absorbing the whispered words, Eagle aimed its magnificent body upward in a powerful thrust. The coal-black bird with its pristine white head and tail nearly disappeared before jackknifing and heading down again. This time it aimed itself at the woman, coming so close that she ducked. A cry that seemed to come from the depths of the earth burst from Eagle and held, echoing.