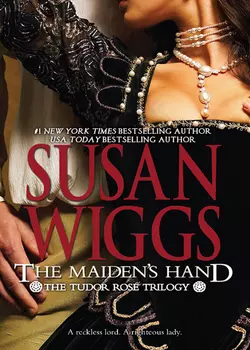

The Maiden′s Hand

Susan Wiggs

Roguishly handsome Oliver de Lacey has always lived lustily: wine, weapons and women are his bywords. Even salvation from the noose by a shadowy society provides no epiphany to mend his debauched ways.Mistress Lark's sole passion is her secret work with a group of Protestant dissidents thwarting the queen's executions. She needs no other excitement—until Oliver de Lacey drops through the hangman's door and into her life.As their fates become inextricably bound together in a struggle against royal persecution, both Oliver and Lark discover a love worth saving…even dying for.

Praise for the novels of #1 New York Times bestselling author

SUSAN WIGGS

“Wiggs is one of our best observers of stories of the heart. Maybe that is because she knows how to capture emotion on virtually every page of every book.”

—Salem Statesman-Journal

“Susan Wiggs is a rare talent! Boisterous, passionate, exciting! The characters leap off the page and into your heart!”

—Literary Times

“[A] lovely, moving novel with an engaging heroine…Readers who like Nora Roberts and Susan Elizabeth Phillips will enjoy Wiggs’s latest. Highly recommended.”

—Library Journal on Just Breathe (starred review)

“Tender and heartbreaking…a beautiful novel.”

—Luanne Rice on Just Breathe

“Another excellent title to [in] her already outstanding body of work.”

—Booklist on Table for Five (starred review)

“With the ease of a master, Wiggs introduces complicated, flesh-and-blood characters into her idyllic but identifiable small-town setting.”

—Publishers Weekly on The Winter Lodge

(starred review, a PW Best Book of 2007)

The Maiden’s Hand

Susan Wiggs

The Tudor Rose Trilogy

Book Two

To my fellow writer

Barbara Dawson Smith,

with love and gratitude for all the years of friendship.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I wish to thank Joyce Bell, Betty Gyenes and Barbara Dawson Smith for generously giving their time and support. Also, thanks to the many members of the GEnie

Romance Exchange, an electronic bulletin board, for so many interesting discussions.

Special thanks to Trish Jensen and Kathryn van der Pol for their proofreading skills.

I am falser than vows made in wine.

—William Shakespeare

As You Like It, Act III, Scene v

Contents

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Epilogue

Prologue

Oliver de Lacey had died badly. He had gone blubbering and pleading to the hangman’s noose, and his last act as a mortal man had been to piss himself.

That morning, he had arisen in his dank cell in Newgate, begged one last time to sire a child on the warden’s daughter, lied through his teeth to the priest who came to grant him absolution, and vomited up his last breakfast.

Now he was paying the ultimate price for his many sins.

After the hanging, Oliver’s descent into hell was not what he expected. Indeed, it bordered on the peculiar. Darkness, aye, but what were those evil slits of gray light and that creaky, lumbering sound? And if he had left his mortal body behind, why did he feel this damnable pain in his neck? Why did he smell fresh-cut wood?

It was new and particularly awful for a man who had not expected to die by execution as a common criminal, of all things. He had always known he would die young. But he had worked hard to ensure himself a glorious demise. He had dreamed of perishing while fighting a duel, racing horses, perhaps even while bedding another man’s wife.

Not—God forbid—swinging by the neck while a bloodthirsty crowd jeered at him.

At least no one knew it was Lord Oliver de Lacey, Baron Wimberleigh, who had died at dawn. He had been arrested, tried and sentenced in his guise of Oliver Lackey—a bearded, common rapscallion who had incited one riot too many.

Thank heaven for small favors. He had spared his family a great shame. They had all gone abroad until the spring; they would come back to find that Oliver had vanished without a trace.

Ah, what a waste, he thought in disgust as his strange conveyance transported him to eternal damnation. He had wanted to make his mark in his short time on earth. In pursuit of this, he had loved every woman he could find, fought every battle he could join, sampled every delicacy, read every book, embarked on every adventure available to an affable young lord. He had lived fast and hard and voraciously with the knowledge that his illness would one day conquer him.

And this morn, an hour before cock crow, he had died a coward’s death.

“They say he died badly.” The voice penetrated Oliver’s hell-bound chariot. “Did you see?”

God’s light, but it was a horrid, unholy voice.

“I saw.” This voice, in contrast, was as sweet as the trill of a lark at dawn. “He showed no dignity whatsoever. I can’t think why Spencer was so insistent about taking this one.”

Spencer? The devil was called Spencer?

“Spencer,” said the ugly voice, “like the Lord above, works in mysterious ways. Does he know you have come?”

“Of course not,” said the woman. “He thinks I only help with the ciphering. He must never know.”

“Well, pox and pestilence, I don’t like it. Not one bit.”

Amen, thought Oliver. Death was getting stranger by the moment. Descending into hell was an odd business indeed.

The creaking and jangling ceased abruptly.

Now what? Oliver wondered. He braced himself for an onslaught of fire and brimstone.

“Careful, now. Is anyone about?” the man asked.

“Just the chief grave digger in his hut yonder. You did give him plenty of fortified wine?”

“Oh, aye. He won’t stir his bones.”

“But I see a light in the window,” the woman said.

“Right. We’d best put on a good show, then. Move the cart just to the edge of the pit. Let’s get this one out.” The chariot lurched. “Easy now. Easy! Frigging slump-backed nag. Almost backed into the pit. Hand me that chisel. I’ll just pry open this panel.”

A screeching sound rent the air, followed by an equine whinny.

“Shrouds and shambles!” the man hissed. “Mind the box! You’ll spill it.”

A square of light opened at Oliver’s lifeless feet. He began tilting, sliding, until his remains poured down a steep incline. He landed on something dusty and infinitely more noxious than anything he had done inside his canions.

“Oh, no,” whispered the female voice. “Dr. Snipes, what have we done?”

What indeed, Oliver wondered.

“He’s fallen into the pit,” she said as if she’d heard his question.

Ah, thought Oliver. At last it begins to make sense. Hell was a pit, exactly as Messer Dante had described. Except this place was cold. Bone-chillingly cold.

“We’ve got to get him out,” said the man called Snipes.

Yes, yes, please. Oliver tried to speak, but no sound emerged from his brutalized throat.

“Dr. Snipes, look! He’s come around. Sweet mercy, he is saved!”

Saved?

Oliver saw a pair of shadows looming above him, the sky a cloudy dark gray behind them.

“Mr. Lackey? Can you hear me?” the woman called out.

“Yes.” The word came out as a thin wheeze.

“He speaks! God be praised!”

Why did this instrument of the Devil praise God? And why did she address him as Lackey? Surely the Devil knew his true identity.

“Mr. Lackey, we must get you out of there,” Snipes said.

“Where am I?” There. He had spoken. A horrible rasp, to be sure, but his speech was intelligible.

“I, er, that is, you’re near the City ditch across from Greyfriars,” Snipes said. “In a, er, in a pauper’s grave.”

“This isn’t hell?” Oliver asked stupidly.

“Some would say aye,” the woman murmured.

God, he loved her voice. It was particularly the sort of voice he adored in a woman—sweet but not shrill, crisp and precise as a well-tuned gittern.

“Surely it’s not heaven,” he said. “Purgatory, then?”

“Oh, Dr. Snipes,” the woman whispered, “he thinks he is dead.”

“I am dead,” Oliver stated in his raspy voice. The dust and straw stirred as he lifted his fist. He sneezed. “I died badly. You said so yourself.”

He could have sworn he heard stifled mirth. “Sir, you were hanged, but you did not die.”

“Why not?” Oliver felt slightly miffed.

“Because we would not let you. We bribed the hangman to shorten the rope and saw to it you were cut down, pronounced dead and nailed into your box before you died.”

“Oh.” Oliver thought about this for a moment. “Thank you.” Then he groaned. “You mean I begged and humbled and pis—er, disgraced myself for naught?”

“It would seem so.”

A distant cock crowed.

“Come, time is short. We must get you out of there. Can you move?”

Oliver tried to sit up. Jesu, but his limbs were weak! He managed to prop himself up. “This place is all lumpy,” he complained. “What sort of hellhole do I find myself in?”

“Lark told you,” Snipes said. “’Tis a pauper’s grave.”

Lark. Her name was as lovely as her voice.

“You might wish to make haste,” she called. “You could catch a disease from them.”

“From what?” Oliver asked.

“From the corpses. ’Tis a pauper’s grave, sir. There’s a heap of them down there, covered with straw and lime dust. When the grave is full, it will be covered over.”

“All that lime makes for excellent grazing once the grass starts,” Snipes remarked helpfully.

“You mean…?” Bile rose in Oliver’s stomach. He lurched to his feet. “You mean you dumped me into a heap of…of corpses?”

“A most regrettable accident,” said Lark.

Oliver had spent weeks in Newgate, enduring poor food and putrid air. He had been hanged nearly to death. There was no way he should have had the strength to sink his hands into the damp earth and scramble out of the grave.

But he did.

In mere seconds he was sprawled, gasping for breath, on the cold and dewy grass.

“God’s shield, that’s foul.” Wheezing, he rolled over. His saviors bent to peer at him. Snipes wore the black cloak and tunic of an undertaker, and in the uncertain light Oliver could see a withered, twisted arm, a prominent nose and chin, and wispy white hair beneath a flat cap.

“I’ll just go and tell the gravedigger we’ve buried the poor sinner.” Snipes lumbered off into the shadows toward a wattled hut in the distance.

“Have you the strength to rise?” asked Lark.

Oliver looked at her. “My God,” he said, staring at the pale oval of her face, its delicate, dawn-limned features framed by a nimbus of glossy raven hair escaping a plain coif. “My God, you are an angel.”

Her full red lips quirked at the corners. “Hardly.”

“Tis true. I am dead. I have died and gone to heaven, and you are an angel, and I am going to spend eternity with you. Hallelujah!”

“Nonsense.” Her manner became brisk as she stuck out her hand. “Here, I’ll help you up. We must get you to the safe hold.”

She tugged at his hand, and her touch infused him with miraculous strength. When he stood upright, he saw that he towered over her. Just for a moment he felt a sense of deep connection with her. He could not tell if she felt it, too, or if she always wore that wide-eyed, startled expression.

“A safe hold?” he whispered.

“Aye.” She surreptitiously wiped her hand on her apron. “You’ll stay there until your throat is healed.”

“Very well. I have only one more question for you, mistress.”

“Yes?”

He gave her his best smile. The one that women of good breeding said could dim the stars.

She tilted her head to one side, clearly lacking the breeding to be properly dazzled.

“Yes?” she said again.

“Mistress Lark, will you have my baby?”

One

“Spencer, you would not countenance what that yea-forsooth knave said to me.” Lark paced the huge bedchamber of Blackrose Priory. “Of all the effrontery!”

“Said to you?” Spencer Merrifield, earl of Hardstaff, had the most endearing way of lifting one eyebrow so that it resembled a gray question mark. Sitting in his grand tester bed, his thin frame propped against pillows and bolsters, he was bathed in the early-evening light that streamed through the oriel window. “You spoke to him?”

“Yes. I—at the safe hold.” She cringed inwardly at the small lie and studied the pattern of lozenge shapes that tiled the floor. Spencer would object to her being present for the hanging. But the safe hold was run by godly folk whose goals matched Spencer’s own.

“I see. Well, then. What did Oliver de Lacey say to you?”

She frowned and plopped down onto a stool by the bed, tucking her soft, kerseymere skirts between her knees. “I thought his name was Oliver Lackey.”

“That is one of his names. In sooth he is Lord Oliver de Lacey, Baron Wimberleigh, son and heir to the earl of Lynley.”

“He? A noble?” The man had been wearing a stained shirt and plain fustian jerkin over torn and ragged canions and hose. No shoes; those were always appropriated by prison wardens. He had looked as common as a mongrel dog—until he had smiled at her.

Spencer watched her closely as if seeking to peer into her mind. She was familiar with the look. When she was very small, she used to liken Spencer to the Almighty Himself, with all the powers of His station.

“Betimes he goes about incognito,” Spencer explained, “I suppose to spare his family from embarrassment. Now. What did the young lord say to you?”

Will you have my baby?

Lark’s face burned scarlet at the memory. Her response had been a drop-jawed look of astonishment. Then, humiliated to the depths of her prayer-fed soul, she had flounced away, instructing him to hide in the cart until Dr. Snipes joined them and they reached the safe hold.

“I shall lie low,” Oliver had said, “but I should be more content if you were lying beneath me.”

Thank heavens Dr. Snipes had returned and spared her from having to respond.

Now she looked at Spencer and felt such a wave of horror and guilt that her hands trembled. She buried them deep in the folds of her skirts.

“I do not recall his precise words,” she said, lying again. “But he had a most insolent manner.”

“Perhaps his brush with death put him in a foul mood.”

It was an unusually tolerant observation from a man of little tolerance. Lark blinked in surprise. She tried to will her flushed cheeks to cool. “He could use a lesson in manners.”

“Be he rapscallion or man of honor, did he deserve to die?”

“No,” she whispered, instantly contrite. She took Spencer’s hand; his was cool and dry with age and infirmity. “Forgive me. I lack your generosity of spirit.”

His fingers squeezed hers briefly. “A woman cannot be expected to comprehend the matters that move a man to courage.”

She felt a sudden urge to snatch her hand away, then just as quickly buried the impulse. She owed all that she was to Spencer Merrifield. If from time to time his well-meaning comments grated, she should ignore them with good grace.

“And what lofty purpose do you have in mind for Oliver de Lacey?” she asked.

She could see the flame of the dying sun reflected in Spencer’s cloudy gray eyes, which peered all the way through to her soul. Sometimes she feared his wisdom, for he seemed to know her better than she knew herself.

“Spencer?” She touched her stiff gray bodice, wondering if her partlet or coif had come askew.

“I’ve a purpose in mind for the lad. My dear,” he said, “I am sick and getting sicker.”

A lump of dread rose in her throat. “Then we shall seek a new physician, consult—”

He waved her silent. “Death is part of the circle of life, Lark. It’s all around us. I have no fear of the hereafter. But I must make provisions for you. The manor of Evensong is already yours, of course. I intend to leave you all my worldly goods, all my monies. You’ll want for nothing.”

She did take her hand away then and tucked it between her knees, seeking warmth as an unbearable chill swept over her. He spoke so matter-of-factly, when in truth his death would change her life irrevocably.

“You are nineteen,” he observed. “Most women are mothers by the time they reach your age.”

“I have no regrets,” she said stoutly. “Truly, I—”

“Hush. Listen, Lark. When I’m gone, you will be left alone. Worse than alone.”

Worse? She caught her breath, then said, “Wynter.”

“Aye. My son.” The word was a curse on his lips. Wynter Merrifield was Spencer’s son by his first wife, Doña Elena de Dura. Many years ago, before Lark’s birth, the marriage had crumbled beneath the weight of Doña Elena’s scorn for her English husband and her flagrant affairs with other, younger men. Like the Church of England and the Church of Rome, Spencer and Elena had been torn apart, the fissure created by infidelity and hatred.

And Wynter, now a strapping young lord of twenty-five, was the casualty.

When she had left Spencer, Doña Elena had not told him she was expecting a child. While in sanctuary in Scotland, she had given birth and raised Wynter to be as bitter against his father as she was and as devoted to Queen Mary as Elena had been to Catherine of Aragon.

Two and a half years earlier Wynter had come back to Blackrose Priory to hover like a carrion bird over his father’s wasting form. Each day Lark watched him furtively from her chamber window. As slim and darkly handsome as a young god, he rode the length and breadth of the estate, his black horse sweeping along the rich green water meadows by the river or racing up the terraced hills where sheep grazed.

The thought of Wynter made Lark fitful, and she stood and walked to the window. The sun was lowering over the wild Chiltern Hills in the distance, and shadows gathered in the river valley.

“By law,” Spencer said wearily, “Wynter must inherit my estate. It is entailed to my sole male heir.”

“Is he your heir?” she asked baldly, though she did not dare to turn and look at Spencer.

“A sticky matter,” Spencer admitted. “I knew nothing of his existence when I put aside my first wife and had the marriage annulled. But as soon as I learned I had a son, I had him legitimized. How could I not? He did not ask to be born to a woman who would teach him to hate.”

Lark heard the clink of glass as Spencer poured himself more of his medicine. “I should not have asked. Of course he is your son and heir.” She shivered and continued to face the window, battered by a storm of bitter memories. “Your only one.”

“You must help me stop him. Wynter wishes to exalt Queen Mary by reviving a religious house at Blackrose Priory. He’ll turn this place into a hotbed of popish idolatry. The monks who lived here before the Dissolution were voluptuous sinners,” Spencer went on. “I sweated blood into this estate. I need to know it will stay the same after I’m gone. And what will become of you?”

She rushed to the stool by the bed. “I try not to think about life without you. But when I do, I see myself continuing the work of the Samaritans. Dr. Snipes and his wife will look after me.” It had occurred to her that she possessed some degree of cleverness, perhaps even enough to look after herself. She knew better than to point that out to Spencer.

He gestured at the chest at the foot of the bed. “Open that.”

She did as he asked, using a key from the iron ring she wore tied to her waist. She found a stack of books and scrolled documents in the chest. “What is all this?”

“I’m going to disinherit Wynter,” he said. She heard the pain in his voice, saw the flash of regret in his fading eyes.

“How can you?” She closed the lid and rested her elbows on top of the chest. “You do love your son.”

“I cannot trust him. When I see him, I notice a hardness, a cruelty, that sits ill with me.”

She thought of Wynter with his hair and eyes of jet, his lean swordsman’s body, and his mouth that was harsh even when he smiled. He was a man of prodigious good looks and deep secrets. A dangerous combination, as she well knew.

“How will you do this?” she asked without turning around. “How will you deny Wynter his birthright?”

“I shall need your help, dear Lark.”

She turned to him in surprise. “What can I do?”

“Find me a lawyer. I cannot trust anyone else.”

“You would entrust this task to me?” she asked, shocked.

“There is no one else. I shall need you to find someone who is discreet, yet totally lacking in scruples.”

“This is so unlike you—”

“Just do it.” A fit of coughing doubled him over, and she rushed to him, patting his back.

“I shall,” she said in a soothing voice. “I shall find you the most unscrupulous knave in London.”

Lark stood at the grand river entrance of the elegant half-timbered London residence. It was hard to believe Oliver de Lacey lived here, along the Strand, a stretch of riverbank where the great houses of the nobility stood shoulder to shoulder, their terraced gardens running down to the water’s edge.

The door opened, and she found herself facing a plump, elderly woman with a hollowed horn thrust up against her ear. “Is Lord Oliver de Lacey at home?”

“Eh? He ain’t lazy at home.” The woman thumped her blackthorn cane on the floor. “Our dear Oliver can be a right hard worker when he’s of a mind to be wanting something.”

“Not lazy,” Lark called, leaning toward the bell of the trumpet. “De Lacey. Oliver de Lacey.”

The woman grimaced. “You needn’t shout.” She patted her well-worn apron. “Come near the fire, and tell old Nance your will.”

Venturing inside a few more steps, Lark stood speechless. She felt as if she had entered a great clockwork. Everywhere—at the hearth, the foot of the stairs, along the walls—she saw huge toothed flywheels and gears, all connected with cables and chains.

Her heart skipped a beat. This was a chamber of torture! Perhaps the de Laceys were secret Catholics who—

“You look as though you’re scared of your own shadow.” Nance waved her cane. “These be naught but harmless contraptions invented by Lord Oliver’s sire. See here.” She touched a crank at the foot of the wide staircase, and with a great grinding noise a platform slid upward.

In the next few minutes, Lark saw wonders beyond imagining—a moving chair on runners to help the crippled old housekeeper up and down the stairs, an ingenious system to light the great wheeled fixture that hung from the hammer beam ceiling, a clock powered by heat from the embers in the hearth, a bellows worked by a remote system of pulleys.

Nance Harbutt, who proudly called herself the mistress of Wimberleigh House, assured Lark that such conveniences could be found throughout the residence. All were the brainchildren of Stephen de Lacey, the earl of Lynley.

“Come sit.” Nance gestured at a strange couch that looked as if it sat upon sled runners.

Lark sat, and a cry of surprise burst from her. The couch glided back and forth like a swing in a gentle breeze.

Nance sat beside her, fussily arranging several layers of skirts. “His Lordship made this after marrying his second wife, when the babies started coming. He liked to sit with her and rock them to sleep.”

The vision evoked by Nance’s words made Lark feel warm and strange inside. A man holding a babe to his chest, a loving woman beside him…these things were alien to Lark, as alien as the huge dog lazing upon the rushes in front of the hearth. The long-coated animal had the shape of a parchment-thin greyhound, with much longer legs.

A windhound from Russia, Nance explained, called borzoyas in their native land. Lord Oliver bred them, and the handsomest male of each litter was named Pavlo.

Lark forced herself to pay close attention to Nance Harbutt, the oldest retainer of the de Lacey family. The housekeeper had a tendency to ramble and a great dislike for being interrupted, so Lark sat quietly by.

Randall, the groom who had accompanied her from Blackrose Priory, was waiting in the kitchen. By now he would have found the ale or hard cider and would be useless to her. This did not bother her in the least. She and Randall had an agreement. She made no comment on his tippling, and he made no comment on her activities for the Samaritans.

According to Nance, the sun rose and set on Lord Oliver. There was no doubt in the old woman’s mind that he had hung not only the moon, but also the sun and each and every little silver star in the heavens.

“I wish to see him,” Lark said when Nance paused to draw a breath.

“To be him?” Nance frowned.

“To see him,” Lark repeated, speaking directly into the horn.

“Of course you do, dearie.” Nance patted her arm. Then she did a curious thing; she smoothed back the hood of Lark’s black traveling cloak and peered at her.

“Dear God above,” Nance said loudly. She picked up her apron and fanned her face.

“Is something amiss?”

“Nay. For a moment you—that look on your face put me in mind of Lord Stephen’s second wife, the day he brought her home.”

Lark recalled what Spencer had told her of Oliver’s family. Lord Stephen de Lacey, a powerful and eccentric man, had married young. His first wife had perished giving birth to Oliver. The second was a woman of Russian descent, reputed to be a singular beauty. Though flattered by the comparison, Lark thought the elderly retainer’s sight was as weak as her hearing.

“Now then,” Nance said, her manner brisk, “when is the babe due?”

“The babe?” Lark regarded her stupidly.

“The babe, lass! The one Lord Oliver sowed in you. And God be praised that it’s finally happened—”

“Ma’am.” Lark’s ears took fire.

“Weren’t for lack of trying on the part of the dear lordling. “Course, ’twould be preferable to marry first, but Oliver has ever been the—”

“Mistress Harbutt, please.” Lark fairly shouted into the trumpet.

“Eh?” Nance flinched. “Heaven above, lass, I ain’t so deaf as a stone.”

“I’m sorry. You misunderstand. I have no…” She lacked the words to describe how appalled she felt at the very suggestion that she might be a ruined woman carrying a rogue’s bastard. “Lord Oliver and I are not that well acquainted. I wish to speak to him on a matter. Is he at home?”

“Sadly, nay.” Nance blew out her breath. Then she brightened. “I know where he’d be. This time of day he’s always going about important business.”

Lark felt vastly relieved. Perhaps the young nobleman was engaged in lordly matters, serving his turn in Parliament or perhaps doing good works among the poor.

It might prove an unexpected pleasure to encounter him in his lofty pursuits.

Deep in the darkest tavern on the south bank, Oliver de Lacey looked up from the gaming table as the black-cloaked stranger entered. A woman, judging by her slight build and hesitant manner.

“Hell’s bells,” said Clarice, shifting on Oliver’s lap. “Don’t tell me the Puritans are at us again.”

Oliver savored the suggestive movement of her soft buttocks. Clarice was no more than a laced mutton in a leaping house, but she was a woman, and he adored women without prejudice.

More than ever, now that he had been given a second chance at life.

“Ignore her,” he said, nuzzling Clarice’s neck, inhaling the scent of lust. “No doubt she is a dried-up old crone who cannot bear to see people enjoy life. Eh, Kit?”

Christopher Youngblood, who sat across the table from Oliver, grinned. “In sooth you enjoy it too much, my friend. Such constant revelry does rob the savor from it.”

Oliver rolled his eyes and looked to Clarice for sympathy. “Kit’s smitten with my half sister, Belinda. He’s saving his virtue for her.”

Clarice shook her head, making her yellow curls bounce on her bared shoulders. “Such a waste, that.”

The other harlot, Rosie, leaned toward Kit, caught his starched ruff in her fingers and turned him to face her. “Let the lady have his virtue,” she declared. “I’ll take his vice.” She gave him a smacking kiss on his mouth and pounded the table in high good humor as his face turned brick-red.

Laughing uproariously, Oliver called for more ale and summoned Samuel Hollins and Egmont Carper, his favorite betting partners, to a game of mumchance. His spirits lubricated by ale and soft womanhood, he rolled the dice in the bowl.

And won. Lord, how he won. This was his first outing since that unfortunate incident—he refused to call it anything so grim as a hanging—and the luck that had delivered him from death now clung to him like a woman’s sweet perfume.

Lucky as a cat with nine lives, he was, and it never occurred to him to wonder if he deserved it. Nor did it cross his mind that the whole incident had been very unusual indeed. Two strangers had risked their own safety to rescue him.

At a cottage near St. Giles, they had provided him with a basin of hot water, a shaving blade and a set of clean clothing. He had bathed, shorn off his beard, dressed and returned home to sleep ’round the clock.

And he was none the worse for the wear, save for a bruised neck, now artfully concealed by a handsome ruff and some redness in his eyes.

His saviors, Dr. Phineas Snipes and Mistress Lark, had wondered aloud why the mysterious Spencer had singled out Oliver for saving.

Oliver de Lacey did not wonder why. He knew. It was because he was blessed. Blessed with angelic good looks, for which he took no credit but which he used to his utmost advantage. Blessed with a large, loving family whose only fault was that they were too hasty to forgive his every transgression. Blessed with a quick mind and a glib tongue. Blessed with a lust for life.

And cursed, alas, to die young. There was no cure for his sickness. The attacks of asthmatic breathlessness were few and infrequent, but when they came, they struck like a storm. For years he had fought each battle, but he knew in the end the disease would conquer him.

“Ollie?” Clarice tickled his ear with her tongue. “Your turn to cast the dice.”

Like a large dog shaking off water, Oliver rid himself of the thoughts. He made a masterful throw. A perfect seven. Clarice squealed with delight, Carper grudgingly gave up his coin, and Oliver rewarded his woman by tucking a ducat deep into her doughy cleavage.

“M-my lord?” A soft, uncertain voice broke in on his revelry.

With a grin of triumph still on his face, Oliver looked up. “Yes?”

The black-clad Puritan gazed down at him. A slim white hand pushed back the hood.

Oliver stood, dumping Clarice from his lap. “You!”

Mistress Lark bobbed her head at him. Her face was stark white, the eyes a luminous rain-colored gray, her lower lip trembling. “Sir, I would like to speak to you.”

Without even looking at Clarice, he reached down and helped her to the bench. “Of course. Mistress Lark.” He gestured at his companions and rattled off their names.

“Do sit down,” he said. She made him feel the most uncanny discomfort. In the smoky lamp glow of the tavern, she did not look as ethereally beautiful as she had at dawn two days before. Indeed, she appeared quite plain in her coarse garb, her hair scraped back into a tight black braid.

“There isn’t any room at the table,” she said. “And besides—”

“I’ve a perfectly good knee just waiting for you.” He grabbed her wrist and lowered her onto his lap.

She yelped as if he had set fire to her backside, and jumped up. “Nay, sir! I shall wait until it is convenient for you to speak to me. In private.”

“Please yourself,” he said, wondering why he felt this urge to bedevil her. “You might have a bit of a wait, then. Fortune is favoring me today.” He held out his tankard. “Have some ale.”

“No, thank you.”

He had the most remarkable urge to kiss her prissy mouth until it became soft and full beneath his. To caress her slender body and melt her stiffness into compliance.

Aware now that he had set the rules of a waiting game, he winked at her and turned back to his companions.

Lark was certain that everything decent about her was being peeled away in layers. What a fool she had been to suppose Oliver de Lacey would be pursuing lordly goals. She was doubly a fool to have left Randall in drunken slumber and come here on her own. She had paid a ferryman to take her across the river. She had moved like a thief through noxious alleyways crammed with vagrants and cozeners, all for the sake of finding a man whom Spencer had, for once in his life, wrongly judged to be a man of honor.

All Lord Oliver seemed to be pursuing were the pleasures of the gaming table, the oblivion of strong ale and the fleshly secrets hidden beneath the laced corset of the woman called Clarice.

Bawdy talk rose like a fog from the gamesters, some of it so wickedly obscure that Lark did not understand. She felt like the flame of a candle buffeted by the winds of corruption. Stubbornly, she refused to be snuffed out.

If he meant to humiliate her by forcing her to wait her turn, then wait she would. Oliver de Lacey did not know her at all. She had learned duty and loyalty from the most honorable man in England. She would endure any torment for Spencer’s sake.

Of course, Spencer would never know how she had suffered. She could not tell him she had stood amid ruffians and doxies and gamesters. And most of all, she could not tell him that she took a secret, shameful interest in her surroundings.

The blatant and lusty sensuality of the people around the gaming table shocked her. It was but midmorning, and they were tippling ale and wine like wedding guests at a midnight feast.

And the center of all the attention, like the sun casting its fire on a host of lesser bodies, was Oliver de Lacey himself.

He bore no resemblance to the pitiful victim who had fallen into the dusty pit of corpses just two days before.

He was as comely as a prince, his hair a shimmering mass of white-gold waves, his face carved into a perfect balance of hard lines and angles harmonizing with a sensual mouth and eyes the color of a robin’s egg. In some men such beauty might have created an air of softness, but not in Oliver de Lacey. His expression held a rare blend of humor and male potency that sparked a flare of awareness in Lark.

He had little to show for his suffering in the bowels of Newgate prison. Most men who had been arrested and condemned for inciting a riot, then secretly saved from death, might be loath to flaunt their presence so soon after the event.

A splendidly cut doublet of midnight-blue velvet displayed his broad shoulders to shameless advantage. Flamboyant gold braid laced his sleeves around powerful arms. And when he threw back his head to laugh, displaying healthy teeth and a musical tenor chuckle, she could hardly blame Clarice for clinging to him. He had that air of potency, of magnetism, that made even sensible folk feel safe and treasured when he was near.

Will you have my baby? The memory came unbidden; his words echoed in her mind, and she hated herself for clinging to them. He had meant it as a jest, no more.

It was chilly in the tavern, with its damp plaster and timber walls and the bleak light of oil lamps. There was no reason on earth Lark should feel warm. Yet she did, as if she possessed embers inside, with some force from without fanning them.

“You’re certain you don’t wish to sit with us?” Oliver inquired, studying her so closely that she was certain he noticed her hot throat and cheeks and ears.

“Quite certain,” she said.

He heaved a great sigh. “I cannot bear to have you standing there in discomfort.” He spread his arms as if to embrace all who sat around the table. “My friends, I must go with dear Mistress Lark.”

She saw the disappointment on their faces, and in an odd, intuitive way she understood it. When Oliver withdrew from the table, it seemed the sun had drifted behind a cloud.

Then he did a singular thing. He sank to one knee before Clarice. Gazing up at her as if she were Queen Mary herself, he took her hand in his, placed a lingering kiss in her palm, and closed her fingers around the invisible token. “Fare you well, my lovely.”

Watching the intimate and chivalrous farewell gave Lark the oddest sensation of yearning. Certainly there was nothing remarkable about a rogue parting from his doxy, yet Oliver managed to glorify the simple act with an air of wistful romance and tenderness. As if he cherished her.

She wondered what it would be like to be cherished, even for a moment. Even by a rogue.

Then he spoiled it by reaching around and pinching Clarice’s backside, causing her to bray with laughter. When he stood and donned a blue velvet hat, the plume brushed the blackened ceiling timbers.

“Kit, I shall call for you later.”

Kit Youngblood sent him a jaunty salute. Though somewhat older than Oliver, more blunt featured and quiet, he was nearly as handsome. Taken as a pair, the two were quite overwhelming. “Do. I missed our carousing while you were away. On a pilgrimage, was it?”

The look they shared was steeped in mirth and fellowship. Then, without warning, Oliver took Lark by the hand and drew her out into the alleyway.

As soon as she recovered her surprise, she pulled away. “Kindly keep your hands to yourself, my lord.”

“Is it your mission in life to wound me?” he asked, looking remarkably sober for all that he had quaffed three tankards of ale while she had watched.

“Of course not.” She clasped her hands in front of her. “My lord, I came to see you to—”

“You held out your hand to me when I lay gasping on the ground at a pauper’s grave. Why flinch when I do the same to you?”

“Because I don’t need help. Not of that sort.”

“What sort?” He tilted his head to one side. The plume in his hat curved downward, caressing a face so favored by Adonis that Lark could only stare.

“The touching sort,” she snapped, irritated that her head could be turned by mere looks.

“Ah.” All male insolence, he reached out and dragged his finger slowly and lightly down the curve of her cheek. It was worse than she had suspected—his touch was as compelling as his lavish handsomeness. She had the most shameful urge to lean her cheek into the cradling warmth of his hand. To gaze into his eyes and tell him all the secret things she had never dared admit to anyone. To close her eyes and—

“I must remember that,” he said, dropping his hand and grinning down at her. “The lady does not like to be touched.”

“Nor do I like walking in a strange alley with a man I hardly know. However, it is necessary. You see, there is a matter—”

“Hail the lord and his lady!” A group of men in sailor’s caps and tunics tumbled past, swearing and spitting and jostling one another as they shoved themselves into the tavern.

“Good fishing to ye,” one of them called out to Oliver. “I hope the perch are biting fair.” The door slammed behind the man, muffling his guffaws.

Lark frowned. “What did he mean?”

She was surprised to see the color rise in Oliver’s cheeks. Why would so shameless a man blush at a sailor’s remark?

“He must have mistaken me for the sporting type.” Oliver started off down the alley.

“Where are we going?” Picking up her skirts, Lark hurried after him.

“You said you wished to talk.”

“I do. Why not here? I have been trying to explain myself.”

A creaking sound came from somewhere above, where the timbered buildings leaned out over the roadway. Oliver turned, grabbed Lark in his arms and pushed her up against a plastered wall.

“Unhand me!” she squeaked. “You rogue! You measureless knave! How dare you take liberties with my virtue!”

“It’s a tempting thought,” he said with laughter in his voice. “But that was not my purpose. Now be still.”

Even before he finished speaking, a cascade of filthy wash water crashed down from a high window. The deluge filled the road where Lark had stood only seconds ago.

“There.” Oliver eased away from the wall and continued down the street. “Both your gown and your virtue are safe.”

Miffed, she thanked him tersely. “Where are we going?”

“It’s a surprise.” The sound of his tall, slashed knee boots echoed down the tunnellike lane.

“I don’t want a surprise,” she said. “I simply want to talk to you.”

“And so you shall. In good time.”

“I wish to talk now. Forsooth, sir, you frustrate me!”

He stopped and turned so abruptly that she nearly collided with him. “Ah, Mistress Lark,” he said, his bluer-than-blue eyes crinkling at the corners, “not half so much as you frustrate me.” She feared he would touch her again, but he merely smiled and continued walking.

She followed him along a pathway, passing kennels where dogs for the bull baitings were housed, trying not to gawk at a flock of masked prostitutes gathering to watch the sport.

The north end of the path opened out to the Thames. The broad brown river teemed with wherries, shallops, timber barges and small barks. Far to the east rose the webbed masts of great warships and merchantmen, and to the west loomed London Bridge. From this distance Lark could not see the grisly severed heads of traitors that adorned the Southwark Gate of the bridge, but the whirling scavenger kites made her think of them and shiver.

Oliver lifted his hand, and in mere seconds a barge with three oarsmen at the bow and a helmsman at the stern bumped the bottom of the water steps.

Bowing low and gesturing toward the canopied seat of the barge, he said, “After you, mistress.”

She hesitated. It had been a mistake to leave Randall behind. For all she knew, Lord Oliver was dragging her along the path to perdition.

Still, the open, elegant barge looked far more inviting than the dank alley, so she descended the stone steps to the waterline. The helmsman held out a hand to steady her as she boarded.

“The lady mislikes being touched, Bodkin,” Oliver called out helpfully.

With a shrug, Bodkin withdrew his hand just as Lark had one foot in the barge and the other on the slimy stone landing. The barge lurched. She tumbled onto the leather cushioned seat with a thud.

Mustering courage from her bruised dignity, she glared up at Oliver. His buoyant grin flashed as he grasped the pole of the canopy and swung himself onto the seat beside her.

Lark stared straight ahead. “I assume we are going someplace where we can speak privately.”

Oliver nudged the oarsman in front of him. “Hear that, Leonardo? She wants to tryst with me.”

“I do not.”

“Hush. I was teasing. Of course I will take you to a place of privacy. Eventually.”

“Eventually? Why not immediately?”

“Because of the surprise,” he said with an excess of good-humored patience. “The tide’s low, Bodkin. I think it’s safe to shoot the bridge.”

The helmsman tugged at his beard. “Upstream? We’ll get soaked.”

Oliver laughed. “That’s half the fun. Out oars, gentlemen, to yonder bridge.”

Lark hoped for a mutiny, but the crew obeyed him. In perfect synchrony, three sets of long oars dipped into the water. The barge glided out into the Thames.

In spite of her annoyance with Lord Oliver de Lacey, Lark felt a thrill of excitement. Turbulence churned the waters beneath the narrow arches of London Bridge. She knew people had drowned trying to pass beneath it. Yet the smooth, swift motion of the sleek craft gliding through the water gave her the most glorious feeling of freedom. She told herself it had nothing to do with the benevolent, lusty and wholly pagan presence beside her.

Moments later, white-tipped wavelets lifted the bow of the boat. As the barge neared London Bridge, it bucked like a wild horse over the roaring waters around the pilings.

Lark lifted her face to the spray. She had come to London for a business transaction, and here she was in the throes of a forbidden adventure. She swirled like a leaf upon the water, buffeted, at the mercy of a whimsical man who, with sheer force of will, had turned her from her purpose and swept her up in an escapade she should not want to experience.

“I wish you would listen to what I have to say,” she stated.

“I might. Especially if it involves wine, women and money.”

“It does not.”

“Then tell me later, my dove. First we’ll have some fun.”

“Why do you insist on surprising me?” she demanded, gripping the gunwale of the boat.

“Because.” He swept off his hat and pressed it over his heart. He looked boyishly earnest, eyes wide, a silver-gilt lock of hair tumbling down his brow. “Because just once, Lark, I want to see you smile.”

Two

She did not understand him at all. That much she knew for certain. She could not fathom why he insisted on entertaining her. Nor did she know why it pleased him so to wave to strangers boating on the Thames, to call out greetings to people he’d never met, to run alongside a herring-buss to inquire about a fisherman’s catch.

Most of all, she could not comprehend Oliver’s shouts of humor and ecstasy when they shot the bridge. The adventure was sheer terror for her.

At first. Her senses were overcome by the rush of the water with its damp, fishy smell. Her teeth jarred with the churning sensation as the bow lifted, then slapped down. The rush of speed loosened tendrils of hair from her braid and caused her skirts to billow up above her knees.

Terror, once faced, was actually rather exhilarating. Especially when it was over.

“Was that my surprise?” she asked weakly once the bridge was behind them.

“Nay. You haven’t smiled yet. You’re white as an Irish ghost.”

She turned to him and forced up the corners of her mouth. “There,” she said through her teeth. “Will that do?”

“It is precious. But nay, I reject that one.”

“What is wrong with my smile?” she demanded. “We cannot all be as handsome as sun gods with beautiful mouths and perfect teeth.”

He laughed, tossing his mist-damp hair. “You noticed.”

“I also noticed your vast conceit.” She poked her nose into the air. “It rather spoils the effect.”

He sobered, though his eyes still shone with mirth. “I meant no insult, dear Lark. It is just that your smile was not real. A real smile starts in the heart.” Forgetting—or ignoring—her interdict against touching, he brushed his fingers over her stiff bodice. “Love, I can make your whole body smile.”

“Oh, honestly—”

“It is a warmth that travels upward and outward, like a flame. Like this.”

She sat transfixed as his hands brushed over the tops of her breasts, covered by a thin lawn partlet. His fingers grazed her throat, then her chin and lips. She thought wildly of the oarsmen and Bodkin at the helm, yet even as a horrible embarrassment crept over her, she stayed very still, transfixed by Oliver.

“A true smile does not end here, at your mouth.” He watched her closely. “But in your eyes, like a candle piercing the darkness.”

“Oh, dear,” she heard herself whisper. “I am not certain I can do that.”

“Of course you can, sweet Lark. But it does take practice.”

Somehow, his lips were mere inches from hers. And hers tingled with a hunger that took her by surprise. She wanted to feel his mouth on hers, to discover the shape and texture of his lips. She had been lectured into a stupor about the evils of fleshly desires, she thought she had done battle with temptation, but no one had ever warned her about the seductive power of a man like Oliver de Lacey.

Closing her eyes, she swayed toward him, toward his warmth, toward the scents of tavern and river that clung to him.

“I am touching you again,” he said, and she heard the whispered laughter in his voice. “Please forgive me.” He dropped his hands and drew away.

Her eyes flew open. He lay half sprawled on the tasseled cushions, one leg drawn up and one hand trailing in the water. “A rather cold day, is it not, Mistress Lark?”

She resisted the urge to make certain her partlet was in place. “Indeed it is, my lord.” She was not used to being teased. And she was definitely not used to bold, handsome men who flung out jests and insincere compliments as if they were alms to the poor.

It mattered not, she told herself. Spencer claimed he needed Oliver de Lacey. For Spencer’s sake she would endure the young lord’s insolent charm. Certainly not for her own pleasure.

“Will you listen now?” she asked. “I have come a very long way to see you.”

“Nell!” he roared, causing the barge to list as he leaned out from under the canopy. “Nell Buxley!” He waved at a shallop proceeding downstream, aimed toward Southwark. “I made heaven in your lap last time we met!”

“Good morrow to you, my bed-swerving lord,” brayed a wine-roughened female voice. A grinning woman in a yellow wig leaned out from the shallop. “Who’s that with you? Have you ransacked her honor yet?”

With a moan of futility, Lark slumped back against the cushions and yanked her hood over her head.

“This is another place of iniquity!” Lark dug in her heels. “Why have you brought me here?”

Oliver chuckled. “’Tis Newgate Market, my love. You’ve never been?”

She stared at the swarm of humanity pushing through the narrow byways, crowding around stalls or pausing to observe the antics of a monkey here, a dancing dog there. “Of course not. I generally try to avoid places frequented by vagrants, cutpurses, and no-account young lords.”

Even as she spoke, she saw a lad dart up behind a portly gentleman. The child tickled the man’s ear with a feather, and when the man reached up to scratch, the little rogue cut his purse and slipped away with the prize.

Lark clapped one hand to her chest and pointed with the other. “That child! He…he…”

“And a good job he made of it, too.”

“He stole that man’s purse.”

Oliver began strolling down the lane. “Life is brutish and short for some people. Let the lad go.”

She did not want to follow Oliver into the raucous crowd, nor did she wish to stand alone, vulnerable to the evils that could befall her. Despite his devil-may-care manner, Oliver, with his prodigious height and confident swagger, made her feel protected.

“Watch this,” he said, sidling up to the dancing monkey. A few people in the crowd moved aside to let him pass. Lark fancied she could feel the heat of the sly, appreciative feminine glances that slid his way.

When the little monkey, garbed in doublet and hat, spied Oliver, it leaped excitedly over its chain. The keeper laughed. “My lord, we have missed you these weeks past.”

Oliver bowed from the waist. “And I have missed you and young Luther.”

Lark caught her breath. It seemed decidedly impious to name a monkey after the great reformer.

“Luther is a chap of strong convictions, are you not?” Oliver asked.

The creature bared its teeth.

“He is loyal to the Princess Elizabeth.”

At the sound of the name, the ape leaped in a frenzy, back and forth over its chain.

“He has his doubts about King Philip.”

As soon as Oliver named Queen Mary’s hated Spanish husband, Luther lay sullenly on the dirt path and refused to move. Oliver guffawed, tossed a coin to the keeper and strolled on while the crowd applauded.

“You are too bold,” Lark said, hurrying to match his long strides.

He sent her a lopsided grin. “You think that was bold? You, who have been known to steal out in the night to save the lives of condemned criminals?”

“That’s different.”

“I see.”

She knew he was laughing at her. Before she could scold him, he stopped at a stall surrounded by long canvas draperies.

“Come see the show of nature’s oddities,” a woman called. “We’ve a badger that plays the tambour.” Reaching out, she grasped Oliver’s shoulder.

Patting her hand, he pulled away. “No, thank you.”

“A goose that counts?” the hawker offered.

Oliver smiled and shook his head.

“A two-headed lamb? A five-legged calf?”

Oliver prepared to move off. The woman leaned close and said in a loud whisper, “A bull with two pizzles.”

Oliver de Lacey froze in his tracks. “This,” he said, pressing a coin into her palm, “I have got to see.”

He made Lark come with him, but she steadfastly refused to look. She stood in a corner of the stall, her eyes clamped shut and her nostrils filled with the ripe scent of manure. Several minutes passed, and she closed her ears to the whistles and catcalls mingling with the animal noises.

At last Oliver returned to her side and drew her out into the bright light. His eyes were wide with juvenile wonder.

“Well?” Lark asked.

“I feel quite strung with emotion,” he said earnestly. “Also cheated by nature.”

Lark shook her head in disgust. For once, Spencer was wrong. This crude, ribald man could not possibly be the paragon of honor Spencer thought him to be. “‘An heart that deviseth wicked imaginations,’” she muttered, “‘feet that be swift in running to mischief.’”

“I beg your pardon?” Oliver weighed his purse in his hand.

“Proverbs,” she said.

“Why, thank you, my lady Righteous.” With an insolent swagger, he plunged down yet another narrow lane, and Lark had no choice but to follow or be left alone in the crowd. They passed flower sellers and cloth traders, booths selling roast pork and gingermen. Oliver laughed at puppets beating each other over the head. He dispensed coins to beggars as easily as if he were passing out bits of chaff.

After what seemed like an eternity, they reached the boundary of the fair. In the distance they could see the horse fair at Smithfield.

“We’ll venture no farther.” Oliver’s face paled a shade. “I mislike the burning grounds.”

She followed him obligingly from the area. Though the blackened stakes and sand pits were not yet visible, she felt their proximity like the brush of a cobweb against her cheek.

“That is the first sensible thing I have heard you say,” she announced. “Think of the condemned Protestants who have been martyred here.”

“I’ve been trying not to.” As they walked past the fringes of the fair, Oliver heaved a great sigh. “I have failed.”

“What do you mean?”

“I wanted to make you laugh and smile, and you have not. Where did I go wrong?”

“Well, you could start with our near drowning while shooting the bridge.”

“I thought you’d find that exhilarating.”

“I found it foolish and unnecessary. As was your greeting to the woman called Nell.” Lark lifted a skeptical eyebrow. “Heaven in her lap?”

He had the grace to blush. “She’s an old friend.”

“What about your treasonous little exchange with a monkey?” Lark continued, enumerating the outrages. “And your prurient interest in a bull’s, er, his two…”

“Pizzles,” Oliver supplied helpfully.

“Hardly a cause for great mirth from me.”

“I know.” He had a rare gift for looking both sulky and charming at once. “I’ve failed you. I—” He broke off, glancing over her shoulder. The sulkiness disappeared, and his face glowed with sheer delight. “Come, Mistress Lark. Here is something you’ll like.”

Pulled along in the wake of his enthusiasm, she found herself at the stall of a bird seller. Wooden crates of burbling doves, huddled robins and moth-eaten gulls were stacked about haphazardly.

“How much?” Oliver asked the man.

“For which one, sir?”

“For all of them.”

The man’s jaw dropped. Oliver grabbed his hand and dumped a small fortune of coins into it. “That should keep you in your cups a good while.”

“My lord,” Lark said, “there are hundreds of birds here. How will you—”

“Watch.” He drew a silver eating knife from the leather sheath attached to his belt and pried open each cage. With a flourish he removed each little door.

“Oliver!” Lark barely noticed that she had used his Christian name. The bird seller uttered a blue oath.

Like a great, winged cloud, the once-captive birds rose. The sound of beating and whirring feathers filled the sky above the fair. It was an awesome sight, darkening the sun for a moment, then turning light as the flock of liberated birds dispersed.

Oohs and aahs issued from nearby fairgoers.

“‘The stars compel the soul to look upward,”’ Oliver de Lacey recited, “‘and lead us from this world to another.’ Plato.”

“I know.” She squinted up at the birds, now mere specks in an endless field of marbled blue. And against her will, a smile unfurled on her lips.

“Eureka!” Oliver spread out one arm like a seasoned showman. “She smiles. Eureka! Archimedes. When he first said ‘Eureka,’ he went running naked through the streets.”

“That,” she said, “I did not know.”

“It is said he made his discovery about the displacement of water while in his bath. The insight so aroused him that he forgot to dress himself before running to tell his colleagues.” Oliver lifted his face to the winter sun as the last of the birds disappeared. “There, you see, my angel. They can soar. I have set them all free.”

“All of them,” she agreed, feeling strangely content.

“Well, not quite.”

She peered at the cages. Not a single bird remained. The bird seller was already stacking his crates in a two-wheeled cart.

Oliver slipped one arm around her waist, and his other hand rested on her bodice, the fingers drumming on the stiff corset of boiled leather.

“There is still one little lark in a cage, eh?”

His barb hit home with a sting of unexpected pain. She tried to look imperious. “Sir, I am insulted. Unhand me.”

He bent low to whisper in her ear. “I could free you, Lark. I could teach you to soar.”

Heat swept from her toes to her nose, and she could not suppress a shiver as his warm breath caressed her ear. Alarmed, she broke away and stepped back. “I do not want you to teach me anything of the sort. I simply want help with a certain matter. You have refused to listen. You have dragged me from pillar to post on a fool’s errand. If you will not help me, I wish you would tell me now so I can be shed of you.”

“You wear outrage like an angel wears a halo.” He sighed dramatically, then lounged against a stone hitch post.

All her life she had been taught that men were strong and prudent, endowed with qualities a mere woman lacked. Oliver de Lacey was a reckless contradiction to that rule. Furious, she marched blindly down the road. She hoped the way led to the river.

With easy strides he caught up with her. “I’ll help you, Mistress Lark. I was born to help you. Only say what it is you require. Your smallest desire is my command.”

She stopped and looked up into his sunny, impossibly wonderful face. “Why do I think,” she said, “that I shall live to regret our association?”

“I cannot understand why you agreed to this,” Kit Youngblood muttered to Oliver. He glared at the prim, straight-backed figure who rode in the fore. They were on the Oxford road leading away from the city, on an errand Oliver had embraced with good heart. The ride was enjoyable, for he loved his horse. She was a silver Neapolitan mare bred from his father’s best stock. Big-boned and graceful as a dancer was Delilah, the envy of all his friends.

“Keep your voice down,” he whispered, his gaze glued to Lark’s gray-clad form. He had always found the sight of a woman riding sidesaddle particularly arousing. “I owe her my life.”

“I owe her nothing,” Kit grumbled. “Why drag me along?”

“She needs a lawyer. For what purpose, she has yet to disclose.”

“You know as much about the law as I do.”

“True, but it would be unseemly for me to practice a profession.” Oliver feigned a look of horror. “People might think me dull and unimaginative, not to mention common.”

“Forgive me for suggesting it, Your Highness. Far better for you to follow your lordly pursuits of drinking and gaming.”

“And wenching,” Oliver added. “Pray do not forget wenching.”

“How did the woman know where to find you?”

“She went to my residence. Nance Harbutt directed her to my favorite gaming house.”

“Hunted you down, eh? And what have you done to the poor woman? She’s barely spoken since we left the City.”

“I took her to Newgate Market.” Closing his eyes, Oliver recalled the rapt expression on her small, pale face when he had set the birds free. “She loved it.”

“You’ve ever been the perfect host,” Kit said. “I do not know why I put up with you.”

“I wish I could say that it’s because you find me charming. But alas, ’tis because you’re in love with my half sister, Belinda.”

“Hah! Faithless baggage. I’ve not heard from her in a year.”

“The kingdom of Muscovy is not exactly the next shire. Fear not. She and the rest of my family will return before long.”

“She’s probably grown thin and sallow and peevish on her travels.”

Oliver chuckled. “She is Juliana’s daughter,” he reminded Kit, picturing his matchless stepmother. “Do you really think such a lass could grow ugly?”

“I almost wish she would. Suitors will be on her like flies on honey. She’ll take no notice of me, the landless son of a knight. A common solicitor.”

“If you believe that, then the game is up before it’s started. You—” Oliver broke off, scanning the road in the distance. “What’s that, a coach?”

Lark twisted around in her saddle. “It looks as if it’s gotten mired.” She made a straight seam of her mouth. “You would have noticed minutes ago if you had not been so busy yammering with Mr. Youngblood.”

“Mistress Gamehen,” Oliver said with a smile, “one day you will peck some poor husband to the bone.”

She tossed her head, the dark coif fluttering behind her. With a squeeze of his legs, Oliver guided his horse past her to investigate the distressed travelers.

The boxy coach had been traveling toward town. Rather than being pulled by big country nags or oxen, it was yoked to a pair of rather delicate-looking riding mounts. Curious.

Behind the coach was a bridge spanning a shallow, rocky creek. Apparently the conveyance had cleared the bridge and become stuck in the muddy berm at the roadside.

“Hello!” Oliver called out, craning his neck to see into the small square window. He waved his hand to show he had no weapon drawn, for travelers tended to be wary of highwaymen.

“Are you mired, then?” he shouted. No response. He drew up beside the coach, frowning at the horses. Indeed they were not draft horses. Smallish heads indicated a strain of Barbary blood.

“Hello?” Oliver twisted in the saddle to send Kit a quizzical look.

The coach door swung open. A blade sliced out and just barely caressed the nape of his neck.

“It’s a trap!” Oliver dismounted, drawing his rapier even before his feet hit the ground. Kit did likewise.

To Oliver’s dismay, Lark leaped out of her saddle, lifted her skirts and rushed toward the coach. Three men, wearing the tattered garb of discharged soldiers, swarmed out. From the grim expressions on their faces, they seemed bent on murder.

Oliver flourished his sword and feinted back from one of the soldiers, a bearded fellow. “I say!” Oliver parried a blow and sidestepped a thrust. “We’re not highwaymen.”

His answer was a wind-slicing front cut that slit his doublet. A bit of wool stuffing bulged from the tear.

A feeling of unholy glee came over him. He loved this feeling—the anticipation of a battle joined, the lure of physical challenge.

“You’re good,” he said to the bearded one. “I was hoping you would be.”

Danger always had this effect on him. It was a battle lust he had learned to crave. Some would call it courage, but Oliver knew himself well enough to admit that it was pure recklessness. Dying in a sword fight was so much more picaresque than gasping his last in a sickroom.

“En garde, you stable-born dunghill groom,” he said gleefully. “You’ll not have the virtue of this lady fair but with a dead man’s blessing.”

The soldier seemed unimpressed. His blade came at Oliver with raging speed. Oliver felt the fire of exhilaration whip through him. “Kit!” he yelled. “Are you all right?”

He heard a grunt, followed by the sliding sound of locking blades. “A fine predicament you’ve gotten us into,” Kit said.

Oliver fought with all the polish he could muster under the circumstances. He would have liked to tarry, to toy with his opponent and test his skills to the limit, but he was worried about Lark. The foolish woman seemed intent on investigating the coach.

The soldier came on with a low blow. Like a morris dancer, Oliver leaped over the blade. Taking swift advantage of the other’s imbalance, Oliver went in for the kill.

With his rapier, he knocked the weapon from the soldier’s hand. The sword thumped into the muddy road. Then Oliver whipped out his stabbing dagger and prepared to—

“My lord, are you not a Christian?” piped a feminine voice beside him. “‘Thou shalt not kill.’”

His hesitation cost him a victory. The soldier leaped away and in seconds had one arm hooked around Lark from behind.

“I’ll break her neck,” the burly man vowed. “Take one step closer, and I’ll snap it like a chicken bone.” Stooping, he snatched up his fallen sword.

“Don’t harm the girl!” one of the other soldiers cried.

“Divinity of Satan,” Oliver bellowed in a fury. “I should have sent you to hell when I had the chance.”

Glaring at Oliver, Lark’s captor drew back his sword arm.

“Thou shalt not kill, either,” Lark stated. As Oliver watched, astonished, she brought up her foot and slammed it down hard on the soldier’s instep. At the same time her pointed little elbow jabbed backward. Hard. If the blow had met his ribs, it would have left him breathless. But he was much taller than Lark and her aim was low, and when it connected, Oliver winced just from watching.

The man doubled up, unable to speak. Then, clutching himself, he half limped and half ran into the woods beyond the road.

Kit’s opponent, bleeding now, backed away. Swearing, he leapfrogged onto one of the horses, cut the traces and galloped off.

Oliver raced toward the third soldier. This one fled toward the remaining horse, but Lark planted herself in his path.

“No!” Oliver screamed, picturing her mown down like a sheaf of wheat. But as Lark’s hands grasped at the mercenary’s untidy tunic, he merely shoved her aside, mounted, spurred and was gone.

“Lark!” Oliver said, rushing forward. She lay like a broken bird in the path. “Dear God, Lark! Are you hurt—” He broke off.

It struck just then. The dark, silent enemy that had stalked Oliver all his life. The tightening of his chest muscles. The absolute impossibility of emptying his lungs. The utter certainty that this was the attack that would kill him.

The physicians called it asthma. Aye, they had a name for it, but no cure.

The world seemed to catch fire at the edges, a familiar warning sign. He saw Lark climb to her feet. Kit seemed to tilt as if he bent to pick something up. Lark moved her mouth, but Oliver could not hear her over the thunder of blood rushing in his ears.

God, not now. But he felt himself stagger.

“Ahhhh.” The thin sound escaped him. Shamed to the very toes of his Cordovan riding boots, Oliver de Lacey staggered back and fell, arms wheeling, fingers grasping at empty air.

Three

“I’ve never stayed at an inn before,” Lark confessed to Kit as she cut a strip of bandage.

Oliver leaned against the scrubbed pine table in the large kitchen and tried to appear nonchalant, when in fact he was doing his best to keep from sliding into a heap on the floor.

What was it about Lark, he wondered, that so arrested the eye and took hold of the heart?

Perhaps it was the childlike sense of wonder with which she regarded the world. Or perhaps her complete lack of vanity, as if she were not even aware of herself as a woman. Or maybe, just maybe, it was her sweet nature, which made him want to hold her in his arms and taste her lips, to be the object of her earnest devotion.

“Oliver and I know every inn and ivybush ’twixt London and Wiltshire,” Kit was saying. Discreetly he sidled over to the table beside Oliver.

To catch me if I fall, Oliver thought, feeling both gratitude and resentment. Cursed with his baffling illness, he had lived a peculiar and isolated boyhood. When he had finally emerged from his shell of seclusion, Kit had been there with his brotherly advice, his ready sword arm and a fierce protective instinct that surfaced even now, when Oliver had grown a handspan taller than his friend.

Kit held out his hand and clenched his teeth as Lark washed the grit from his wound. She worked neatly, her movements deft as she applied the bandage. Oliver noticed that her nails were chewed, and he liked that about her, for it was evidence that she suffered unease like anyone else.

She wasted no missish sympathy on Kit but confronted his injury with matter-of-fact compassion and an unexpected hint of humor. “Try to avoid battles for a few days, Kit. You should give this gash a chance to heal.”

“I wonder what the devil those bast—er, rude scoundrels were after,” Kit said. “They didn’t even attempt to rob us.”

“Perhaps they were planning to kill us first.” Oliver had become rather casual about his brushes with death. Long ago he had decided to defy fortune. He refused to let the weakness of his lungs conquer him. He meant to die his own way. Thus far, the pursuit had been amusing.

“Thank you, mistress.” Kit pressed his bandaged hand to his chest. “I feel much better now. But I would still dearly like to know what those arse—er, wayward marls were about. Ah! I just remembered something.” With his good hand he reached into the cuff of his boot and pulled out a coin. “I did find this when we searched the coach.”

Both Oliver and Lark leaned forward to study the coin. Their foreheads touched, and as one they drew back in chagrin.

“Curious,” said Kit, angling the coin toward the waning light through the kitchen window. “Tis silver. An antique shilling?”

“Nay, look. ’Tis marked with a cross.” Cocking his head, Oliver read the motto inscribed around the edge of the piece. “‘Deo favente.’”

“With God’s favor,” Lark translated.

Oliver discovered a useful fact about Mistress Lark. She was incapable of keeping her counsel. Like an accused criminal in a witness box, she turned pale and ducked her head with guilt.

Damn the wench. She knew something.

“Who were they, Lark?” Oliver demanded.

“I know not.” She flung up her chin and glared at him. Oliver wondered if it was just a trick of the sinking light or if he truly saw the glint of fear in her eyes.

“I’ll keep this and make some inquiries.” Kit left the kitchen through a passageway to the taproom.

Oliver grinned and spread his arms wide. “Alone at last.”

She rolled her eyes. “Take off your doublet and shirt.”

He sighed giddily. “I love a wench who knows her own mind and is forthright in her desires.”

“My only desire is to find the source of all this blood.” She pointed to the dark, sticky stain seeping through his clothing.

“Your barbed tongue?” he suggested.

“If I could inflict such damage, my lord, I’d have no need of a protector, would I?” She patted the tabletop. “Sit here so I don’t have to stoop to examine you.”

He hoisted himself up. Without hesitation, she drew on first one lace point attaching his sleeve to his doublet and then the other. His bare, sun-bronzed arms seemed to stir her not at all. Did she not see how smooth and well muscled they were? How strong and shapely?

“Now the doublet,” she said, “or shall I remove that, as well?”

“It’s so much better when you do it.”

She nodded absently and began working the frogged onyx fastenings free.

Her hands were as light and delicate as the brush of a bird’s wing. As she bent close to her task, he caught a whiff of the most delicious scent. It clung to her hair, her clothes, her skin. Not perfume or oil, but something far more evocative.

Woman. Pure woman. How he loved it.

“Why did you stop me from killing that sheep biter who tried to murder me?” he asked.

She parted the doublet like a pair of double doors. “You are no assassin, my lord.”

“How do you know?”

“I don’t know for sure. But instinct tells me that you have never killed a soul, and it would pain you if you did. You seem a compassionate man.”

“Compassionate?” His doublet, finally freed, fell backward with a clunk to the table. “I am no compassionate man, but a bold and brash rogue. A brute of the first order.”

“A brute.” Her mouth thinned, and a sparkling echo of humor lightened her voice. “Who faints in the aftermath of battle.”

He snapped his mouth shut. So, she thought the asthma attack was a swoon. Should he set her straight, or should he allow her to go on believing him a coward? Worse than a coward. A high-strung, tender, emotional, limp-wristed, sentimental man. A wretch beyond redemption.

She answered the dilemma for him, bless her. She turned those enormous rain-colored eyes up to him and said, “My lord, I do not impugn your manhood.”

“Thank God for that,” he muttered. Seeing that he had irritated her, he donned a look of earnestness. “Go on.”

“Your behavior today marks you as a person of true courage. For a man who loves combat, to fight is no sign of bravery. But for one who abhors it, to do battle is a sign of valor.”

“Quite so.” The idea pleased him. If the truth be known, he loved a good sword fight or round of fisticuffs. But let her think he had been forced to drag courage from reluctance for her sake.

“This will hurt,” she said. “The fabric of your shirt clings to the wound.”

“I’ll try not to scream when you remove it.”

“Truly, you are never serious.” Gingerly she worked the caked lawn fabric from the gash in his side. He felt a burn, then a hot trickle as he began bleeding anew, but he’d be damned if he’d say anything. Compassionate man indeed!

She lifted the shirt over his head and removed it. Her exclamation was high-pitched, feminine and wholly welcome to Oliver’s ears.

“I do so love it when a woman cries out at the sight of my bare chest,” he said.

“Tis a terrible wound,” she said.

“Nay, just bloody. Clean it up and bandage it, and I’ll be good as new.”

He was hoping that as she worked she would notice his chest was broad and deep, nicely furred with golden hair a shade darker than that on his head. But the silly witling had no appreciation whatever for his physique. His male beauty was lost on her. He wondered what the devil she was thinking.

Determined to keep her wits about her, Lark concentrated on her task. But her thoughts kept wandering. She could barely keep from staring. She caught her lip firmly in her teeth and tried to think only of cleansing the wound, not of the magnificent body of the man sitting on the table.

He was right about the gash just beneath his arm. It was shallow and should heal well. His thick doublet had protected him from the worst of his opponent’s blade.

“’Tis clean now,” she said, rinsing her hands in the water basin. She pressed a folded cloth to the cut. “Hold this, please, and I’ll bind it.”

“This is such an honor.”

He was the most obliging man she had ever met. Perhaps that was why Spencer had chosen him.

“I shall have to wrap you snugly to keep the pad in place,” she said.

“Wrap away, mistress. I’m all yours.”

This proved to be the most awkwardly intimate part of the whole business. She leaned close, practically pressing her cheek to his naked chest as she passed the strip of cloth around behind him.

She could feel the warmth and smoothness of his skin. Could hear his heart beat. Its rhythm quickened.

Nonsense. She was plain as a wood wren, and he was as beautiful as a god.

A god, aye, but he smelled like a man.

In truth, the scent was as exotic to her as the perfumes of Araby. Yet some primal instinct inside her, some wayward feminine impulse Spencer had failed to suppress, recognized the scent of a man. Sweat and horse, perhaps a tinge of saddle leather and woodsmoke. Individually these smells provoked no reaction, but taken as a whole they made a heady bouquet.

She gritted her teeth and tried to keep from fumbling with the bandage. In one day she had seen and heard and felt more of the world than she had in all her nineteen years, and she did not like being thrust into such a feast of voluptuousness.

What she liked was life at Blackrose Priory. The quiet hours of study and prayer. The sober, steady rhythm of spinning and weaving. The safety. The solitude.

One day with Oliver de Lacey had snatched her out of that protective cocoon, and she wanted to go back in. To tamp down the wildness growing inside her, to deny that she had ever felt such a thing as excitement.

“Lark?” he whispered in her ear, and his breath was a tender caress.

“Yes?” She braced herself, wondering if he’d ask her again to have his child.

“My dear, you have bound me like a Maypole.”

“What?” Lark asked stupidly.

“While I’m not averse to bondage in some situations, I think several yards of cloth is sufficient.”

Startled, she stepped back. The makeshift bandage did indeed wrap him like ribbons round a Maypole. A strangled sound escaped her.

A giggle. Lark had never giggled in her life.

Oliver released a long-suffering sigh. “Had I known it was so easy to make you laugh, I would have gotten myself wounded much earlier in the day.”

She sobered instantly. “You must not say such things.” Seeking a distraction, she began to tidy the area, folding the unused bandages and removing the basin of water. “I never did thank you and Kit, my lord, for enduring such trouble on account of me.”

“What man would not lay down his life for a lady in peril?” he asked. “Happily, it did not come to that. In fact, I should thank you.”

She emptied the basin out the door of the kitchen and turned to him, perplexed. “Thank me for what?”

“As you pointed out earlier, you stopped me from killing a man. For all that he did provoke me, I should not like to have his blood on my hands.”

“My foolishness almost cost you your life. I let him grab me from behind.”

Oliver slapped his palms on the tabletop. “Ah, you did fight like a spitfire, Lark. Your quick thinking and courage are rare.”

“In a woman, you mean.”