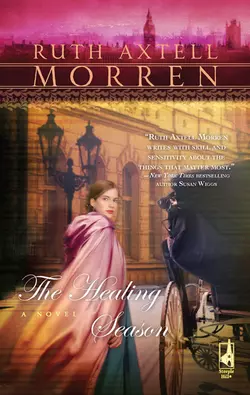

The Healing Season

The Healing Season

Ruth Axtell Morren

Mills & Boon Silhouette

Praise for

RUTH AXTELL MORREN

and her novels

DAWN IN MY HEART

“Morren turns in a superior romantic historical.”

—Booklist

“Morren’s tales are always well plotted and fascinating, and this one is no exception. 4½ stars.”

—Romantic Times BOOKreviews

LILAC SPRING

“Lilac Spring blooms with heartfelt yearning and genuine conflict as Cherish and Silas seek God’s will for their lives. Fascinating details about 19th-century shipbuilding are planted here and there, bringing an historical feel to this faith-filled romance.”

—Liz Curtis Higgs, bestselling author of Whence Came a Prince

WILD ROSE

Selected as a Booklist Top 10 Christian Novel for 2005

“The charm of the story lies in Morren’s ability to portray real passion between her characters. Wild Rose is not so much a romance as an old-fashioned love story.”

—Booklist

WINTER IS PAST

“Ruth Axtell Morren writes with skill, sensitivity and great heart about the things that matter most…. Make room on your keeper shelf for a new favorite.”

—New York Times bestselling author Susan Wiggs

“Inspires readers toward a deeper trust in the transforming power of God…[Readers] will find in Winter Is Past a novel not to be put down and a new favorite author.”

—Christian Retailing

The Healing Season

Ruth Axtell Morren

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

For Justin, Adája and André.

Thanks, guys, for putting up with a writing

mom. When I dotted the final i and crossed

the final t on this one, André said,

“Great, that means you won’t be on the

computer 24/7 anymore.”

Only until the next story beckons…

But unto you that fear my name shall the sun of righteousness arise with healing in his wings.

—Malachi 4:2

The Bible is a book of reversals. Old things become new, the dead come to life, the lost are found. Even those who were the vilest of sinners are now empowered by grace to become the virgin bride of Jesus Christ.

—Francis Frangipane,

Holiness, Truth and the Presence of God

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Epilogue

Questions for Discussion

Author’s Note

Chapter One

London, 1817

The sight that greeted Ian Russell as he stood in the doorway of the dark, malodorous room gave him that sense of helplessness he hated. It was in stark contrast to those times when he was setting a bone or stitching up a wound, knowing he was actively assisting a person in his recovery.

This situation was the kind where he knew his pitifully small store of skills would be of little use.

Here, only God’s grace could save the pathetically young woman lying on the iron bed in front of him, her life ebbing from her like the tide in the Thames, leaving exposed the muddy rocks and embankments on each side.

Blood soaked the covers all around the lower half of the bed. Ian crossed the small room in a few strides and set down his square, black case at the foot of the bed.

The women were always young: fourteen, fifteen, twenty, sometimes even thirty—if they lived that long. Women in their prime, their lives snuffed out by the life growing within them. This one didn’t appear to be more than seventeen or eighteen.

As he began drawing back the bedclothes, he looked at the only other occupant of the dim room—a young woman sitting beside the bed.

“Will…will she be all right?” she asked fearfully. He spared her another glance and found himself caught by her breathtaking loveliness. Large, long-lashed eyes appealed to him for reassurance. Strands of light-colored hair framed delicately etched features as if an artist’s finest brush had been used to trace the slim nose, the fragile curve of her cheek, the pert bow of her lips.

He blinked, realizing he’d been staring. “I don’t know,” he answered honestly before clearing his mind of everything but saving the life of the pale girl lying on the sodden bed.

“Can you tell me what happened?” he asked, attempting to determine whether it was a miscarriage by nature, or a young woman’s attempt to abort an unwanted life.

As he lifted the girl’s skirts and measured the extent of dilation, he listened to the other woman’s low, hesitant account.

“She had…tried to drink something…several things, I think…but nothing worked. I think she grew desperate and tried to get rid of it herself.” She raised her hand and showed him the knitting needle. “I found this beside her.”

It didn’t bode well. Blood poisoning could already have set in. If the girl contracted a severe case of fever, she’d be dead in a few days. He prayed she hadn’t punctured anything but the membranes.

Sending a plea heavenward, Ian set to work to stop the bleeding.

“Can you remove her stays?” he asked the young woman sitting by the bed. Would she be able to handle what was in store, or was she too squeamish?

The young woman stood and gingerly approached him. As she hesitated, he repressed an impatient sigh. Pretty and useless. Probably a lightskirt, he decided, like the one lying unconscious. His heart raged with the familiar frustration at how easily a young woman’s virtue was lost in this part of London.

But he had no one else to assist him. It was two in the morning, and he’d been summoned from his bed, with no idea what he would find when he arrived at his destination.

The edges of the young woman’s sleeves were stained with blood as if she’d already tried to help her friend. At his bidding now, she leaned over the bed and began to lift the girl’s dress higher. Her hands were shaking so much they fumbled on the lacings of the corset.

“Here, let me,” he said, barely concealing his annoyance. He took one of the scalpels from his case and slit the corset up its length.

It was a wonder the girl hadn’t already miscarried, the way she was bound so tightly. She was further along than he’d supposed.

He addressed his reluctant assistant. “It’s important that we stop the bleeding. In order to do that, I’m going to have to remove the unborn child. Do you think you’ll be up to this? You’re not going to faint on me?”

The woman stared at him, her pupils wide black pools within silvery irises. She bit her lip. “I’ll…I’ll try not to.”

“You’ve got to do better than that.” He tried for the note of encouragement he used with students around the dissecting table for the first time, but his mind was more concerned with the young girl bleeding to death. They had a long night ahead of them.

Dawn was lighting the interior of the room when Ian straightened to massage the kinks out of his lower back.

He glanced at his young assistant. Her pretty frock was ruined, the front and sleeves spattered with blood.

She hadn’t fainted, he’d give her that, although many times he thought she’d be sick. She’d clasped her hand over her mouth more than once. Now she wiped the perspiration from her forehead with her sleeve, pushing back the damp golden strands of hair that had fallen from their knot.

“The bleeding has abated and her pulse, though weak, is regular. We’ve done all we can for now.” He turned away from the bed to the basin of water to wash his hands.

After dumping it out the window and pouring some fresh water to wash off his instruments, he asked, “Can you see if there are any fresh linens for the bed?”

She started, then glanced around the dingy surroundings. “I don’t know if she would have anything.”

“Perhaps the woman who let me in earlier. Can you ask her?”

She pressed her lips together. “I doubt she would be so obliging.”

“I suggest you find out. Bribe her if you have to. Your friend can’t lie in that bloody mess.” He nodded curtly toward the soiled linens.

The young woman straightened her back and gave him a look that told him the words had stung. It was the first hint of anything other than fear he’d seen in her all night. He’d rarely had such a jittery nurse. He was surprised a woman her age—at least twenty, he’d judge—hadn’t been around a delivery room before.

She left the room without a word.

Ian forgot her as he dumped cranioclast, regular forceps, crochet and hooks into the basin. The water immediately clouded red.

He had little hope the girl on the bed would survive. If the loss of blood didn’t kill her, childbed fever likely would.

The other woman returned as he was drying the instruments.

“You had some success,” he said, noting the folded linens she carried in her arms.

“Not with the landlady.” She laid the gray sheets down on the vacated chair and eyed the bed. “The neighbor upstairs whose boy went to fetch you last night gave me what little she could spare.”

As she continued standing there, he approached the bed. “Here, I’ll show you how.” He began to strip the soiled sheets from under the patient, again amazed at the woman’s ignorance in changing a bed for an invalid. “If you can procure some fresh ticking for this bed later today, it would help.”

She nodded, taking hold of the sheet on the other side of the bed. After they had done the best they could with the limited supplies available, Ian took up the bucket with the remains of the night’s work.

“I’m going to see about a burial.”

Once again the young woman looked queasy. She averted her eyes from the bucket and nodded.

Ian found the lad who’d brought him the night before and had him fetch a shovel.

Out in the small, refuse-filled yard, he dug a hole deep enough to keep stray animals from uncovering it, dumped the remains into it, and filled it with the dirt.

Dear God, he began, then stopped, not quite knowing what more to say. A poor half-formed child, destined for a miserable existence if it had come to term. And yet, he felt the familiar sense of defeat over every lost life, life that hadn’t yet had a chance to live.

Thank You for sparing the mother, he finally continued. I pray You’ll watch over her in the coming days that she might heal. Bless this infant. Welcome him into Your kingdom.

He gave a final pat with the back of the shovel to the unmarked grave and returned it to the boy. “Thank you.”

“Sorry for getting you up in the middle of the night. Mum and I ’eard the screams. ’Twas awful. Sounded like she was dying.” He sniffed. “Mum’d ’eard as ’ow you don’t charge people wot ’aven’t got ’ny blunt.”

He nodded. “You did the right thing.”

Ian trudged back upstairs. He reentered the room and gathered his things to depart. Ignoring the other woman, he bent over his patient and felt her forehead. If fever didn’t develop over the next twenty-four hours, she had a fighting chance.

Lord, grant her Thy healing, if it be Thy will. Show her Thy mercy and grace.

He straightened and turned to the young woman who had been sitting by the bedside. Once again he was struck with her beauty. Ethereal and fragile…how deceiving looks could be.

In another few years she’d probably be poxed and coming around to St. Thomas’s to be treated, like so many of the women he saw.

“I’ll be by later in the morning to check on her,” he told the young woman. “There isn’t much you can do for her now, except keep her warm and give her some water to sip if she wakes.” He handed her a small parcel from his satchel. “This is ergot. If you stir a little in water, it will help stop the bleeding.”

She took it gingerly. He tried to give some words of encouragement, but didn’t want to get her hopes too high. “Try to get some rest yourself,” he said simply.

She made no reply, so he gave a last look toward the girl on the bed. What she needed was divine intervention, and he was too exhausted to pray.

Ian departed the room as silently as he’d come.

Eleanor woke to the sound of low voices. Her maid knew better than to disturb her before noon.

Her eyelids protested as she forced them open. Two men stood by the bed. Frightened, she sat up, finding herself in a chair. She didn’t remember falling asleep here. Why wasn’t she in her bed?

Betsy! Recollection came back in a heap of nightmarish images. Her friend had been bleeding to death when Eleanor had found her.

Aching muscles in her neck and back shrieked in outrage as she looked toward the bed. The tall, young doctor who’d arrived in the wee hours of the night was standing at Betsy’s bedside now, another man beside him.

He’d come back as he’d promised.

Had Betsy made it? Eleanor couldn’t see past the two men.

Standing, she winced at the pins and needles shooting through her feet. What time could it be? It was difficult to judge from the overcast day visible through the small, dirty window. Had she really been able to fall asleep after all she’d seen last night? Eleanor shook her head as she walked softly toward the bed.

Hearing her approach, the doctor turned. “I’m sorry to disturb your slumber.”

She passed both her hands down the sides of her head, trying to smooth her hair. She must look a fright.

“How is she?” she asked, made even more self-conscious under the doctor’s steady gaze, which seemed to miss nothing from her tangled locks to her rumpled, bloodstained dress.

“About the same,” he answered, turning his attention back to Betsy. “That’s good news, actually,” he added, his tone gentler than it had been the previous evening when he’d barked orders like a ship’s commander. Last night she’d put up with it only because she was so desperately frightened for Betsy’s life. The doctor had seemed so competent, never hesitating in his rapid actions, his hands skillful and steady.

But this morning was a different story. Betsy was out of the woods, it appeared, and the doctor didn’t look quite so fierce.

Eleanor wet her lips, considering how to play this scene. The grateful friend…the composed nurse…the weary toiler…

She studied the doctor a few seconds before turning a questioning glance in the other man’s direction.

The doctor answered the unspoken question in her eyes. “This is my apprentice, Mr. Beverly.” The man was only a youth from what she could see.

“Pleased to meet you, Mr. Beverly,” she said graciously, extending her hand. “Excuse my appearance. Dr.…?” She raised an eyebrow to the dark-haired doctor.

“Mr. Russell,” he supplied for her. “I’m a surgeon,” he added, explaining the lack of title.

She nodded and addressed herself to the youth. “Mr. Russell can tell you how we spent our evening. I haven’t had a chance to go home and change my garments.”

The boy was blushing furiously and stammering protestations.

“I would introduce you,” the surgeon said, “but as we didn’t have time for the niceties last night, I am afraid I am still ignorant of your identity.”

“Eleanor Neville.” She never tired of the sound of the stage name she’d given herself. It had the ring of quality. The syllables rolled off her tongue with self-assurance.

“Mrs. Neville,” the youth stammered. “It’s an honor to meet you.”

“Thank you.” She gave a demure smile. It was obvious he recognized the name.

The surgeon made no sign that her name meant anything to him. “Has she awakened at all?” he asked her.

“Once,” she replied. “She was thirsty and I gave her a few sips of water as you suggested with the powder. That was all she could manage.”

He nodded. “Yes, it’s to be expected.”

“I haven’t had time to go home yet. I wanted to ask you—can she be moved? It would be much easier to take care of her in my own house.”

“I’m afraid she has lost too much blood to be moved this soon.”

Eleanor frowned. “I don’t know how often I will be able to stop in to see her. Perhaps you could recommend a nurse. I could pay her.” She turned an apologetic smile toward the younger man. “I must be at work most afternoons and evenings.”

As he nodded in understanding, she turned to find the surgeon’s eyes on her. They held a censure that made her wonder what she had said that was so wrong.

In the light of day she saw that his dark hair was actually auburn, its coppery shade deepened to chocolate-brown in the eyes focused on her. Before she could speak, his attention shifted to his apprentice.

The two men spent the next couple of minutes discussing Betsy’s case. Eleanor heard words like erysipelas, necrosis, and blood poisoning. Mr. Russell took the woman’s temperature, felt her pulse and finally said to Eleanor, “Continue giving her the ergot. Also, comfrey tea. It will help bring down any inflammation and stanch the bleeding. I’ll be by tomorrow, but if she takes a turn for the worse, send the boy around again.”

She nodded. “I’ll do my best, but as I said, I must leave her in the evening to work.”

He looked down at her, and again she felt strong disapproval emanating from those dark irises. “Can you not forgo your evening’s activities for one night?”

She stared at him for a moment. Forgo her evening’s performance at the theater? What did he think she was—a mere chorus girl? She glanced at the young man, and seeing his cheeks turn deep red, she felt vindicated. Obviously he understood the impossibility of the suggestion.

She drew herself up. “I couldn’t possibly ‘forgo’ my duties tonight.”

“Are you so popular with your clientele that you cannot give up an evening’s earnings for the sake of your friend here? May I remind you she is still in grave danger?”

Her eyes grew wider.

“Ian,” the apprentice began hesitatingly, “Mrs. Neville isn’t…er…uh…”

As Eleanor glanced from one man to the other in puzzlement, it suddenly dawned on her. The good surgeon thought she was a prostitute! Her nostrils flared as she drew herself up.

Abruptly, she clamped her mouth shut on the set down she was about to give him. Putting both hands on her hips, she thrust one forward, shaking back her hair away from her face.

“Well, I don’t know now,” she drawled in her broadest cockney. “I got me clients, and they ’spect to see me regular. Kinda like yer patients, I should imagine. Wot ’appens if you don’t come callin’, eh? Go to the next quack down the block, I shouldn’t wonder.”

She blew on her fingernails and polished them against her bodice, as she gave the young man a firm nod. His mouth hung open and his eyes stared at her.

“There’re so many gents callin’ theirselves doctors nowadays, a cove’s gotta watch out for ’is business, ain’t it so, Mr. Beverly?”

“Oh…uh, yes, ma’am.” His jaws worked furiously, as if they needed to catch up to his words.

She began strutting around the room, hands still on her hips, swaying them just as she saw the women outside the theater do. “So, you see ’ow it is, Doc. I got me rounds tonight, just like you.”

She turned back to them and gave the doctor a long, slow look up the length of his tall, slim physique.

When she reached his eyes, she detected the same stern look he’d worn throughout the night as he’d battled for Betsy’s life. She flicked a glance at the young apprentice. He’d lost his dumb stupor and was actually grinning. He must have figured out she was playacting.

“Oh, we understand, perfectly, Mrs. Neville,” Mr. Beverly told her with a vigorous nod.

“All I understand,” said the surgeon, “is that your young friend’s life is hanging by a thread. Her only hope lies in skilled nursing help.”

As Ian strode from the building, he experienced the impotent fury he did every time he saw a young woman unmindful of the consequences of her street life. Hadn’t Mrs. Neville learned something from seeing her friend nearly bleed to death?

He clenched his jaw. The woman was more beautiful than she had a right to be. She might be able to ply her trade for a few short years, but then what? If she’d seen the ugly results he dealt with every day from women dying of the pox or clap, she’d rethink her occupation.

He chanced a glance at Jem, his young apprentice, already regretting having brought him. The woman had enthralled him in a few minutes of conversation.

In reality Jem was his uncle’s latest apprentice at the apothecary, but Ian knew how important it was for an apothecary to get practical experience with patients, so he took him on his rounds whenever he had a chance.

The boy was whistling a cheerful tune that Ian didn’t recognize. “You can’t let every pretty face discompose you, my boy,” Ian chided, remembering the boy’s blushes around the beautiful Mrs. Neville.

Jem’s pale complexion turned ruddy again. “But that wasn’t just any pretty lady, that was Eleanor Neville!”

“Is she related to royalty?”

The boy stopped in his tracks. “Don’t you know who Mrs. Neville is?”

“Not a clue. Should I?”

“She’s the greatest actress on the stage.”

An actress? He stared at Jem in disbelief. Then he remembered her strange turnaround, one moment a frightened young woman, her speech too refined for her mean surroundings, the next talking like any common streetwalker. She had been pulling his leg! He shook his head. He had misjudged her, and she had turned the tables on him. He couldn’t help a grudging smile.

“An actress, is she?” he asked thoughtfully. “I’ve heard of the great Mrs. Siddons and Dorothy Jordan, but of Mrs. Eleanor Neville, not a whisper.”

“That’s because those others are at the Drury Lane. Mrs. Neville plays in the burlettas at the Surrey.”

Burlettas! The word conjured up images of women prancing about a stage, singing bawdy songs.

“Don’t look like that! You should see her sing and dance. And she’s funny. She has more talent in her tiny finger than all the actresses at the Drury Lane and Covent Garden put together.”

“I guess I’ll just have to take your word for that.” Ian resumed his walk, unwilling to spend more time thinking about a vulgar actress. The description belied the delicately featured young woman who had fought beside him throughout the night.

“You can joke, but someday you’ll see I’m right,” Jem insisted.

“I doubt I shall have such an opportunity since I rarely indulge in theatergoing, much less musical burlesque.” He glanced at the street they were on. “Let’s get a hack at the corner and go to Piccadilly. We’ll visit Mrs. Winthrop and then stop in and see how Mr. Steven’s hernia is doing.”

As they continued in silence, Ian noticed Jem shaking his head once or twice. Finally the boy could keep still no longer. “I can’t believe you didn’t recognize Mrs. Neville. Why, her playbills are posted everywhere. She’s been taking London by storm in her latest role. I’ve heard even the Prince is enchanted.”

“Well, then I must be the only one in London who has not yet succumbed to Mrs. Eleanor Neville’s charms. She was almost useless as an assistant.” Again, a different picture rose to his mind, of a young woman overcoming her terror to save a friend’s life. He shook aside the image. An actress was little better than a prostitute.

“I was afraid I’d have to divide my time between reviving her and keeping my primary patient from bleeding to death,” he added cuttingly.

“Poor thing! She must have had a rough time of it. I wish I’d been there with you!”

Ian looked at the young man with pity. “To help my patient or to hold Mrs. Neville’s hand?”

Ian couldn’t help picturing those slim hands with their almond shaped nails, how they’d smoothed back the patient’s hair from her brow, and remembering her soft voice as she encouraged her friend throughout the night’s ordeal.

An actress? The image wouldn’t fit the one formed last night. How long would the innocent-looking, ladylike woman be impressed upon Ian’s memory?

Chapter Two

As she sat before her mirror, her maid dressing her hair, Eleanor was gratified to note that a full nine hours’ rest followed by the special wash for her face made of cream and the pulverized seeds of melons, cucumber and gourds had left her complexion as fresh and soft as a babe’s.

She touched the skin of her cheek, satisfied she would need no cosmetics today.

With her toilette completed, Eleanor went to her wardrobe and surveyed her gowns. The mulberry sarcenet with the frogged collar? She tapped her forefinger lightly against her lips in consideration. No, too militaristic.

The pale apricot silk with the emerald-green sash? She had a pretty bonnet that matched it perfectly. Too frivolous?

She ran her hand over the various gowns that hung side by side, organized by shades of color. Blues, from palest icy snow to deepest midnight, greens from bottle to apple, reds from burgundy to cerise, and so on to the white muslins and satins. She enjoyed seeing the palette of colors. Gone forever were the days when she was lucky enough to have one dirty garment to clothe her back.

She pulled out one gown and then another until she finally decided on a walking dress of white jaconet muslin with its richly embroidered cuffs and flounced hemline. With it she wore a dark blue spencer and her newest French bonnet of white satin, trimmed with blue ribbons and an ostrich plume down one side of the crown.

When she had judged herself ready, she stood before her cheval glass for a final inspection. Her blond tresses peeked beneath the bonnet, with a small cluster of white roses set amidst the curls. She fluffed up her lace collar. White gloves and half boots in white and blue kid finished the outfit. The picture of maidenly innocence and purity.

“How do I look, Clara?” she asked the young maid.

“Very pretty, ma’am. The colors become you.”

Eleanor smiled in recognition of the fact. Good. If her appearance didn’t put Mr. Russell to shame, her name wasn’t Eleanor Neville.

She took up the shawl and beaded reticule her maid held out to her.

“Is the coach ready?” she asked Clara.

“I’ll see, madam,” Clara answered with a bob of her head and curtsy.

“I shall be in the drawing room below,” Eleanor said.

She had found out from the young boy in Betsy’s rooming house that Mr. Russell had a dispensary in Southwark, in the vicinity of Guy’s and St. Thomas’s Hospitals. They were not so very far from the theater, she thought, as she sat in her coach and rode from her own neighborhood in Bloomsbury and headed toward the southern bank of the Thames.

She needed to accomplish two things on this visit to the surgeon: firstly, to find out about proper nursing care for Betsy, and secondly, to clear up a few things to the good doctor.

She would present such a composed, elegant contrast to the woman he’d seen the night before last that he would fall all over himself with apologies.

She was not a streetwalker and had never been. It mortified her more than she cared to admit that after so many years, someone could so easily fail to notice her refinement and see only the dirty street urchin.

It hadn’t helped that she’d behaved like such a poor-spirited creature during Betsy’s ordeal. But it had been awful finding Betsy like that. Eleanor still felt a twinge of nausea just thinking about it.

She gazed out the window of her chaise, no longer seeing the streets, but recalling the terrified young girl, younger than Betsy, when she’d gone into premature labor. She rarely ever called up those memories, but last night had summoned up all the horrors of those hours of painful labor in vivid detail.

Her own delivery had ended successfully in the birth of a child who had survived, but the ordeal for a scared, undernourished, ignorant girl had almost killed her.

She folded her gloved hands on her lap. Those days were far behind her. She was a different person, one older and wiser in the ways of the world, and few people knew anything of her past.

The coach arrived at the surgeon’s address, and the coachman helped her descend onto the busy street.

The building looked respectable enough. Mr. Russell must have achieved some success in his profession to be able to open his own dispensary.

Several people stood in line at the front. As she neared the brick building, she noticed the brass plaque by the door.

Mr. Ian Russell, licensed Surgeon, Royal College of Surgeons

Mr. Albert Denton, Apothecary-Surgeon

Below it appeared: Midwifery Services.

She pushed past those waiting, ignoring their angry looks and murmurs, and entered the brick building.

Immediately, she took a step back. The place reeked of sickness and poverty. The waiting room was packed with unwashed bodies—young, old, and every age in between. By their dress, they did not look like paying patients. The rumors must be true that Mr. Russell served one and all.

Every available wooden bench was occupied. Some huddled on the floor. The rest stood leaning against the walls.

Eleanor braced herself and ventured farther into the waiting room. She was surrounded by the lowest refuse of life, those that inhabited Southwark and other similar London neighborhoods. She saw them lurking at the fringes of the theater every night when she departed in her coach. Hard work and determination had enabled her to escape these surroundings, and she had no desire to ever live in such conditions again.

She took a few steps more and found a bit of wall space to lean against. Daring another peek around her, she saw that some of the sick had even brought a form of payment: a pigeon in a small wooden cage, a handkerchief wrapped around some bulky item—a half-dozen potatoes or turnips to give to the good surgeon in exchange for his services.

She heard moans of pain beside her and, looking down, she saw a man holding his wrist gingerly in his other hand. Beside him sat another with an exposed ulcerated leg propped up in front of him.

Eleanor brought her scented handkerchief to her nostrils, fearing the foul miasma that permeated the air. She couldn’t take the risk of exposing herself to some perilous humor and sicken.

All eyes were upon her—at least of those patients not too caught up in their pain. She read admiration and some envy in their glances. She was accustomed to that look and bestowed smiles on one and all alike before retreating behind an impersonal gaze above the crowd.

The closed door opposite her across the room suddenly opened and she recognized Mr. Beverly, the young apprentice. She waved her handkerchief at him. He saw her immediately and nodded in greeting, a wide grin splitting his face. She smiled graciously, relieved to see that he immediately made his way toward her.

“Mrs. Neville, what are you doing here? Has the young woman taken a turn for the worse?”

“No, though she is still very weak. But it is about Miss Simms that I am here. If I could speak with Mr. Russell for a few moments?” She gave him a look of gentle entreaty.

“Yes, of course, madam. Let me inform him that you are here.” He took an apologetic glance about the room. “As you can see, he’s quite busy today, but I know he’ll see you as soon as I let him know you are here.”

“I shan’t require much of his time.”

He was gone only a few moments before returning to beckon her through the door.

Mr. Russell was finishing bandaging up a patient’s arm.

“That should do it, Tom,” he told the burly young man. “Let’s hope you fall off no more ladders for a while, eh?”

“You’re right, there, Mr. Russell. I’ve got to watch me step from now on.”

“All right. Come by in a week and we’ll see how you’re mending.”

As soon as the man had left, Mr. Russell came toward her. The smile he had given the male patient disappeared and he was back to the frowning surgeon. Eleanor suppressed her vexation. All the trouble she’d taken with her appearance and she didn’t detect even a trace of admiration in those brown eyes.

He probably knew nothing of fashion. Look at him, in his vest, the sleeves of his shirt rolled up to his elbows. Her physician would never so much as remove his frock coat when he came for a visit.

“Mrs. Neville, Jem tells me you’ve come about your friend.”

She cleared her features of anything but concern. “Yes, about Betsy Simms. I’m quite distraught. I haven’t been able to stop by to see her since early yesterday afternoon. She felt warm to my touch. I brought fresh linens and some broth, but I greatly fear her being alone there. I tried to talk to the landlady, but she didn’t care to involve herself in any way.”

“What about the boy’s mother? The one who lives upstairs.”

“I tried her, too, but she works all day. She promised to look in this evening.”

“She has no family?”

Eleanor shook her head sadly. “None that I know of. She is a singer at the theater where I work.” She wondered if the words meant anything to him, but saw no reaction in his eyes.

“When she missed a performance, I stopped by her room on my way home. I didn’t want her to be dismissed from the troupe. I found her doubled over, bleeding…well, you saw her condition.”

Again his eyes gave her no clue to his thoughts, though he listened intently. She scanned the rest of his face, noticing again the reddish tints of his hair. She wondered if he had the fiery temper to match.

“I see,” he replied, his tone softening. “You said she had taken some potions?”

“Yes, she told me she’d been to a local herbalist who’d given her a remedy to take, but to no avail. Then she’d bought something from a quack. It made her awfully sick, but still…” Her voice trailed off at the indelicate subject.

“No menses,” he finished for her.

“Just so,” she murmured, looking down at her hands, which still held her handkerchief.

“I’ll stop by to see her again today.”

“That would be most kind,” she said with a grateful smile. “Are you sure she cannot be moved?”

“It would be highly risky at this point. You cannot nurse her yourself?”

“No. I can look in on her every day and bring her fresh linens and refreshment, but I usually have rehearsals in the afternoon and performances in the evening. My evenings are late, so in consequence, my day begins later than most.”

He was weighing her words. Finally, he said, “It may be possible to find her a nurse through a Methodist mission I work with. There are many worthy women who give of their time there to help the poor and infirm.”

“If they could send someone, I’d gladly pay her. I meant to tell you as well to send your medical bills to me.”

He dismissed her offer with an impatient wave of his hand. “Don’t worry about it. Why don’t you go to the mission and inquire about a nurse? They are usually shorthanded themselves, so I don’t promise anything.”

“Very well. Where is this mission?”

“In Whitechapel.”

“Whitechapel?” Her voice rose in dismay. That was worse than Southwark.

“Yes.”

“You want me to go there alone?”

“I beg your pardon. I go there so often myself, I forget it’s not the kind of neighborhood a lady would frequent.” His glance strayed to the outfit she’d given so much thought to that morning.

She wasn’t quite sure his tone conveyed a compliment. “I should think not.”

He considered a few seconds longer and finally answered, the words coming out slowly, as if he was reluctant to utter them. “If you’d like…I could accompany you there. Would late this afternoon be satisfactory? Your Miss Simms should really have some nursing help as soon as possible.”

She nodded. “I will be at the theater this evening, but I don’t have a rehearsal this afternoon.”

“I can leave as soon as I finish with all my patients here.”

“Very well. Do you have a carriage?”

He shook his head. “No, I don’t keep a carriage.”

“We can go in mine, if you think my coachman won’t be beaten and robbed while he is waiting for us.”

“He’ll be quite all right, I assure you.”

“Then I’ll come by around three o’clock. Does that give you sufficient time?”

“Yes, that would be fine.”

As she turned to go, his next words stopped her. “I believe I owe you an apology.”

She turned around slowly.

“The other night, I mistook you for…”

Assuming her cockney, she filled in, “A doxy?”

She detected a slight flush on his cheeks. At his nod, she batted her hand coyly. “Gor! Think nothin’ of it, guv’n’r. ’Appens all the time. I don’t know wot it is about folks, but they’re forever mistayken me for someone else. Sometimes even the Queen, poor old deah. I tell ’em ‘I ain’t such ’igh quolity.” She finished with a hearty laugh. “But neither am I no judy, no, sir!”

He was giving her a bemused look, as if he didn’t know what to make of her little performance. “You’re an actress.”

“Yes,” she answered in her own accent. “You’ve never been to the Surrey—the Royal Circus now?”

“No.”

“No? It’s not far from here.”

“I don’t go to the theater.”

Her eyes widened in disbelief. “Never?” The theater was one of the few places where everyone could meet and find enjoyment, from highest to lowest in society. “Are you a Quaker?”

He gave a slight smile. “No, I haven’t the time for such amusement.”

She remembered the packed waiting room. “I can well believe that.”

When he said nothing more, she knew it was time to make her exit. “I shall not keep you from those who need you more. Until three o’clock, then?”

“Until three o’clock.”

Ian popped a few cardamom seeds into his mouth as he watched Mrs. Neville’s chaise pull up at the curb of the dispensary. The actress was punctual, at least. He was still annoyed with himself that he’d committed to accompanying her to the mission. He had little time to spare for excursions like this. Still, the girl needed nursing. It was a miracle she was even alive.

The coachman opened the door and let down the steps. Ian climbed into the smart coach, nodding to Mrs. Neville and seating himself opposite her in its snug interior.

She glanced toward the dispensary before the carriage door shut behind him. “It looks deserted now. What a difference from this morning.”

“Yes, every broken limb has been set, every wound bandaged.”

As the carriage lumbered forward, she asked him, “Do you have such a roomful of patients every day?”

He smiled slightly. “No. Sometimes there are more.” He grinned at the horrified look in her eyes. “I’m only partially speaking in jest. The dispensary is only open four days a week. On the other days I do rounds at St. Thomas’s Hospital a few streets down and hold an anatomy lecture for students there. I also tend the sick at the mission we’re heading for. Then there are the days I pay house calls.”

“When do you rest?”

“I honor the Lord’s Day, unless I’m called for an emergency.”

She nodded and looked out her window. Had he satisfied her interest with his answers and was she now back to thoughts of her own world?

What would occupy such a woman’s thoughts? He found himself unable to draw his eyes away from her. For one thing, she had an exquisite profile. Her small-brimmed bonnet gave him an ample view. Her curls were sun-burnished wheat. Her forehead was high, her nose slim and only slightly uptilted, her lips like two soft cushions, her chin a smooth curve encased in a ruffled white collar.

But her most striking feature was those eyes. Pale silver rimmed by long, thick lashes a shade darker than her hair.

This afternoon she was dressed in a dark blue jacket and white skirt, which looked very fashionable to his untrained eyes. He frowned, trying to remember if she had worn the same outfit earlier in the day. But he couldn’t recall. It had been something dark, but he couldn’t remember the shade. He’d been too dazzled by the shade of her eyes to notice much of anything else.

Chiding himself for acting like a schoolboy, he tore his attention away from her and examined the interior of the coach. It had a comfortable, velvet-upholstered cabin, which looked too clean and new to be a hired vehicle. To keep such a carriage in London, with its pair of horses, was quite expensive.

He wondered how a mere actress could afford its upkeep. He glanced at her again, remembering Jem’s high praises. She must indeed be a successful actress to be outfitted so well. Still, he doubted. He knew actresses usually had some titled gentleman setting them up in style.

But she went by Mrs. Neville.

“Your husband, is he an actor as well?” he found himself asking.

She turned to him. “There is no Mr. Neville,” she replied, her pale eyes looking soft and innocent in the light.

“I’m sorry,” he answered immediately, assuming she was widowed.

She smiled, leaving him spellbound. The elegant beauty was now transformed into a lovely young girl. “You think I am a widow? I repeat, there is no, nor ever was, a Mr. Neville. It’s merely a stage name.”

It was his turn to be surprised. “You mean it’s not your real name?” She must think him an unsophisticated country bumpkin.

She laughed a tinkling laugh. “I just liked the sound of Mrs. Eleanor Neville. It adds a sort of dignity, don’t you think?”

“Yes, I suppose it does,” he answered slowly, trying to adjust his notions of her. Curiosity got the better of him. “What was your…er…name before?”

The friendly look was gone, in its place cool disdain. “My previous name is of no account. It has been long dead and forgotten.”

He felt the skin of his face burn and knew a telltale flush must be spreading across his cheeks, but Mrs. Neville had already turned back to her window. Despite her rebuke, he felt more intrigued than ever. Why would a person ever change her name? Was it a commonplace practice among theatrical people?

It was a long carriage ride, across the Thames and through the congested streets of the City. He spoke no more to her, preferring to concentrate his thoughts on the rest of the evening. He would probably stop at his uncle’s apothecary shop to drop off several prescriptions and pick up the ones he’d had Jem leave earlier in the day. He needed to check on a few patients. That brought his thoughts back to the young woman who’d nearly killed herself.

“Did you have a chance to look in on—er—Miss Simms again, Mrs. Neville?”

Mrs. Neville. He couldn’t get used to the name anymore. It made her sound matronly, completely at odds with the young ingenue looking at him.

“Yes, I stopped to see Betsy before I came to collect you. She had awakened. I fed her some broth and gave her the powder you left. She was still very weak although she didn’t seem feverish.”

He nodded, glad the danger was passing. “I’ll go around tonight.”

“She’s very scared,” Mrs. Neville added.

“She might well be. She almost killed herself.”

“She doesn’t think she had any other choice. If she’d been discovered in a family way, she would have lost her position. If that had happened, she’d have lost her room. She would have ended up in the street. What would she have done with a child then?”

Ian was well familiar with the scenario. He saw it played out countless times a day.

He began to feel a grudging admiration for the young actress. She had not abandoned her friend and was now going to some lengths to assure her full recuperation. He continued to observe her as the carriage trod the cobblestone streets. Beneath Mrs. Neville’s fashionable appearance, there lay a woman very much aware of the grimmer realities of life.

The carriage drew up at the Methodist mission. Eleanor looked around her suspiciously as Mr. Russell helped her alight. The streets had grown narrower and smellier. She clutched her handkerchief to her nose as the doctor led her toward the entrance of the mission.

It at least had a welcoming appearance. A lamp stood at the door and the stoop was swept clean. They entered without knocking.

Eleanor breathed in the warm air before once more putting her handkerchief to her face, this time to mask the smell of cooked cabbage and lye soap.

Mr. Russell poked his head into a room and finding no one led her farther down the corridor.

“Good afternoon, Doctor,” an older woman called out cheerfully as she emerged from another room. “We weren’t expecting you today. What can I do for you?”

“Is Miss Breton in at the moment?”

“No, I’m sorry, sir, she had to step out.”

“Who is in the infirmary?”

“Mrs. Smith.”

“I shall go in and speak with her, then. Thank you.”

Eleanor noticed the woman eyeing her as they walked by and entered a long room filled with beds. Every one was occupied, she noticed, and they all held children. She’d never seen a children’s hospital before. She looked curiously at each bed as Mr. Russell led her toward a woman at the far end.

After brief introductions, she listened as the surgeon explained to the woman their need for a nurse. Eleanor only half paid attention, her interest drawn to the children in the room. A little girl in a nearby bed smiled at her, and she couldn’t help smiling back. Slowly, she inched her way toward her. The child’s dark hair and eyes reminded her of her own Sarah.

“Are you feeling poorly?” she asked the girl softly.

The child nodded. “I was, but now I’m feeling much better. Nurse tells me I must stay in bed a while longer, though.”

“Yes, you must get stronger.” The child was so thin it was a wonder her illness hadn’t done her in.

A young boy beside her called for her attention, and before long Eleanor found herself visiting each bed whose occupant was awake.

Mr. Russell approached her. “We’re very fortunate. There is a lady who is available to spend part of the day with Miss Simms. We can go to her house now and make arrangements if you have time. She lives not far from here.”

“Very well. Let’s be off.” She turned to the children around her and smiled. “I want to see you all well the next time I visit. If you promise, I’ll bring you a treat.”

“We promise!” they all chorused back.

Chapter Three

After they’d visited the nurse, Mrs. Neville dropped Ian off, at his request, near London Bridge.

“Good night, Mr. Russell,” she said, holding out her hand. “Thank you for accompanying me.”

“You needn’t thank me. It’s part of my job,” he replied, hesitating only a fraction of a second before taking her hand in his.

He felt a moment of union as her gloved hand slipped into his. For some reason, he was loath to let it go immediately. Repudiating the feeling, he disengaged his hand from hers. “Good night, Mrs. Neville.”

Without another word, he opened the carriage door and descended into the dark street.

He quickly crossed the parapeted bridge, giving not a backward glance as he heard the rumble of the chaise continue on its way.

He breathed in the mild September air in an effort to get the image of Mrs. Neville out of his mind. He had lived through too much and seen too much to let one pretty female face stir him.

Entering the neighborhood of Southwark, he walked the short distance to St. Thomas’s Hospital. The new building was little more than a century old, a beautiful neoclassical design fronting Borough High Street. Instead of taking this main entrance, Ian continued on to the corner and turned down St. Thomas’s Street toward the small church that formed part of the hospital’s southern wall.

His uncle had been recently appointed the hospital’s chief apothecary, and Ian was sure he would still be found in his herb garret under the church’s roof.

Ian climbed the narrow circular stairs leading to the church’s attic. The spicy aroma of drying herbs permeated the passageway. “Anybody here?” he called out when he reached a landing.

“I’m in the back.” Jem’s voice came from a side partition.

Ian poked his head through the curtained doorway and found Jem washing bottles. “Uncle Oliver in the garret?”

The younger man grinned. “Yes, he is.”

Ian climbed the last section to the raftered attic that served as his uncle’s workshop. Sheaves of herbs hung from the roof. Bottles and jars lined the shelves set against the naked brick walls. One section held a cupboard full of small square drawers. A desiccated crocodile was suspended from the ceiling.

His uncle was hunched over a large glass globe that sat upon a squat brick kiln. As its contents bubbled and steam collected on the globe’s interior surface, a slow drip ran down its narrow glass neck into a china bowl at the other end.

“Good evening, Uncle Oliver.” Ian set down his medical case and leaned his elbows against the long, thick table that bisected the room.

His uncle twisted his gray head around. “Ah, good evening, Ian. Come for the prescriptions?” He resumed his watch on the distilling herbs as Ian replied, “Yes. I caught a ride across town.”

“Is that so? How fortunate. Who was coming all this way at this hour? Someone coming to Guy’s or St. Thomas’s for an evening lecture?”

“No, just a—” He paused, at a loss to describe Mrs. Neville. “Friend of a patient’s” sounded too complicated. “A lady—” Was an actress a lady? He doubted it. “Someone in need of hiring a nurse. I took her to the mission to see if they could recommend someone.”

“A lady? A young lady, an old lady?” His uncle stood and gave the bellows a few puffs to increase the flames of the fire in the kiln before turning away from the alembic and approaching the opposite side of the table.

“Give your uncle who rarely stirs nowadays from this garret a bit of color and detail to events outside the wards of St. Thomas’s.”

Ian smiled at his uncle’s description of his life. “A young lady,” he answered carefully, turning to fiddle with the brass scales in front of him.

“Well, I’m relieved she wasn’t an old crone. Did you have a lively time?” Uncle Oliver went to the end of the table and brought forward some stoppered bottles.

Ian took the bottles from him. Digitalis against dropsy; essence of pennyroyal for hysteria; tincture of rhubarb as a purgative; crushed lavender flowers to use in a poultice; some comfrey powder to ease inflammation.

“I don’t think one can describe a visit to the mission’s infirmary as ‘lively,’” he began, then stopped himself as he remembered the smiles and laughter of the children in the few moments Mrs. Neville had entertained them. “Have you ever heard of Eleanor Neville?”

“The actress?”

Ian looked in surprise that even his semisecluded uncle knew the actress’s name. “I thought you knew nothing of the goings-on of the outside world.”

Uncle Oliver smiled. “I do read the papers. I hear she’s a hit in the latest comedy at the Royal Circus.”

Ian began placing the bottles into his medical case.

“The Royal Circus,” his uncle repeated with a fond smile, taking a seat on a high stool across from Ian. “My parents used to take me there as a boy when it was an amphitheater. It rivaled Astley’s equestrian acts. It’s not too far from here, on Surrey. Haven’t you ever been?”

“No,” Ian replied shortly. His uncle well knew he never went to the theater. He had little time for acrobats and tumblers.

His uncle rubbed his chin thoughtfully. “Now they put on melodramas and musical operas—burlettas, I think they call them. It was renamed the Surrey for a while under Elliston. Then Dibdin took over its management a few years ago and gave it back its original name.”

“You sound quite the expert on the theatrical world.”

“Oh, no, although I do enjoy a good comedy or drama now and then.” His uncle gave him a keen look under his graying brows. “It wouldn’t do you any harm to get out and enjoy some entertainment from time to time. You’ll kill yourself working and found you’ve hardly made a dent in humanity’s suffering.”

“I’ll tell that to the queue of patients waiting for me at the dispensary the next time.”

Uncle Oliver chuckled. “Just send them over to me. Jem and I will fix them up.”

“Most of them can’t afford the hospital’s fee.”

“So, tell me more of Eleanor Neville. I imagine she is young and pretty.”

Ian shut his case and set it on the floor. “Yes, you could describe her as young and pretty.”

His uncle folded his hands in front of him and leaned toward Ian as if prepared for a lengthy discourse. “You are making me envious. To meet a renowned actress who is both young and pretty. What did the two of you find to talk about?”

Ian frowned. “What is that supposed to mean?”

“Well, I can’t imagine your telling her about your latest dissection, much less the doctrines of Methodism. And I feel you wouldn’t want to hear too much about what goes on in the theater world.”

“So, you think I have no conversation?” He took up the black marble mortar and pestle and began pounding at the chamomile flowers his uncle had left in it.

“Not at all. I’m just curious how you spent your afternoon with Miss Neville.”

“She introduced herself as Mrs. Neville, but she explained later that she wasn’t married, that it was merely a stage name.” His pounding slowed as he thought about it again.

“Unmarried, eh? It gets more and more interesting. You know, Ian, I’ve told you before, you need to find yourself some female companionship. It’s time you were married and settled in a real home and not just some rooms next door to your dispensary.”

Ian couldn’t help laughing. “When did we get from meeting an actress to settling down?”

His uncle didn’t return the smile. “Perhaps when it’s the only young woman I’ve heard you mention in I don’t know how long. I’m grasping at the proverbial straw.”

“Well, you can let it go. I met Mrs. Neville purely by chance and, I assure you, I’m unlikely to see her again, except in the course of my work, if our—er—mutual patient takes a turn for the worse.” Ian began explaining the events that had led up to their meeting, in an effort to divert his uncle’s attention from Mrs. Neville.

After Ian finished describing the night’s struggle to save Miss Simms, his uncle got up from the stool and rummaged in his various drawers and Albarello jars, mixing together a variety of dried herbs. He came back with a small sack for Ian.

“Mix an infusion of this and have her drink it as often as possible throughout the course of the day. It should help with the bleeding.”

Ian took it and put it with the other prescriptions. “Thank you.”

“Speaking of your life,” his uncle continued. “I’ve been thinking of talking with the board here at St. Thomas’s. They could use another instructor in pathology. Why don’t you curtail some of your patient load and take on additional teaching work? It would leave you more time for research.”

Ian rubbed his temples. It was a familiar suggestion. “I am satisfied with my work as it is, as you well know.”

“You would ultimately help more people if you could continue working in the laboratory and at the dissection table.”

Ian walked away from his uncle and stopped at the small dormer window overlooking the courtyard of the great hospital. He munched on a cardamom seed he took from the bag in his pocket as he watched a few students crisscrossing the courtyard’s length on their way to an evening lecture.

It didn’t help that his uncle knew Ian almost better than he knew himself. Uncle Oliver had become like a second father to Ian, when as a lad of thirteen Ian had begun his apprenticeship under him. Except for the war years and his time spent walking the wards at La Charité in Paris, Ian had been primarily under his uncle’s tutelage since he’d left home.

He turned back to Uncle Oliver. “I must be going. I still have to look in on the young woman before calling it a day.”

His uncle, as usual, knew when it was time to end a conversation. The two bid each other good night, and Ian descended the stairs. With a final wave to Jem, who was sweeping the floor before leaving for the evening, Ian exited the apothecary shop.

When he reached the main road, he saw the mist rising on the river in the distance.

He turned in the opposite direction and continued walking but soon his steps slowed. If he turned down any one of the narrow streets on his right, they’d take him to Maid Lane. It would be less than a mile to New Surrey Street. There Mrs. Eleanor Neville was probably preparing to step onto the stage. He pictured the lights and raucous crowds. He imagined her cultured voice raised above the audience.

Giving his head a swift shake to dispel the images, he picked up his pace and headed on his way.

Life was full enough as it was. He had no need to go looking for trouble.

When Eleanor finally left her dressing room that night, exhausted yet exhilarated after her performance, she walked toward the rear entrance of the theater where she knew her carriage awaited her. She gave her coachman instructions to stop at Betsy’s before going home.

She was afraid the landlady wouldn’t open, but after several minutes, someone finally heeded her coachman’s loud knocking.

“It’s late to be paying calls,” the woman snapped.

“I’m looking in on my friend.”

“That Betsy Simms? She ought to be thrown in the magdalen! This ain’t no house of ill repute.”

“I’m sure it isn’t,” Eleanor replied acidly, walking past the slovenly woman, who barely made room for her. She quickly climbed the foul-smelling, narrow stairs and opened Betsy’s door without knocking. She found her friend awake.

“How are you feeling?” Eleanor asked softly, crouching by the bed.

“As if I’d been run over by a dray,” she answered weakly.

“You might as well have been. Thank goodness that surgeon was nearby and came as soon as he was called. I had no idea what to do.”

“He stopped by a little while ago.”

“Did he?” A warm flood of gratitude rose in her that he’d kept his word.

Betsy gave a faint nod. “He said I was doing all right but that I needed to rest for several days. He told me how foolish I’d been.” Tears started to well up in her eyes.

Eleanor pressed her lips together. Why couldn’t his lecture have waited a few more days, at least until Betsy was a bit stronger? “Don’t pay him any heed. He was just concerned about you.”

“I tried to explain, but he didn’t let me tire myself.” She took a few seconds to gather her flagging strength. “He…told me you had already explained everything to him.”

“That’s right.” Eleanor rose from her cramped position. “Now, don’t concern yourself with any of that right now. Just think about getting well again.” As she spoke she brought a glass of water she found by Betsy’s bed. “Here, take a sip of this and then get back to sleep.”

She cupped her hand under Betsy’s head to raise it. The girl obediently took a few sips and then sagged against the pillow.

Eleanor set the glass on the bedside table and straightened. “I shall be off, then. A nurse is coming tomorrow, did Mr. Russell tell you that?”

Betsy nodded. “He was very kind.”

Eleanor smoothed the bedcovers and adjusted the pillow beneath Betsy’s head.

“What else could I have done?” Betsy asked. “I couldn’t have the baby. The theater wouldn’t have kept me on if they’d known—”

“Shh. Don’t think about that now.” Eleanor patted the girl’s hand.

“But how do you manage it? Haven’t you ever found yourself in such a situation?”

Eleanor hesitated, not wanting to upset Betsy further. But when she saw that the girl would not be quieted, she finally said, “Once…when I was very young—even younger than you.”

“What did you do?”

“It doesn’t matter now. It was long ago. What I learned since then is to be very careful. You mustn’t let this happen to you again.”

“But what do you do? You saw what happened. None of those potions did any good.”

“You must prevent it from happening. You must be very careful with the kind of man you take up with. It’s up to him. You must insist he take the necessary precautions.”

“What kind of precautions?”

Eleanor looked at the pale young woman in pity. She had so much to learn. “You needn’t concern yourself about that now. You have a long recovery ahead of you. But once you’re well, we’ll talk again. Because if you don’t learn to be careful, you’d better stay away from men.”

“But you laugh and flirt with them as much as the rest of us girls at the theater.”

“It only looks that way. What those gentlemen offer must be very good before I’ll allow them to come any nearer than arm’s length.”

The two were silent a few moments, each lost in thought. Finally Betsy sighed. “Mr. Russell told me I wouldn’t survive a second time. He said it was only by God’s grace that I lived through this time.”

“I don’t know about God’s grace, but I think you were lucky you had a competent surgeon. Now, don’t think about it anymore for the moment. Get some rest and get yourself well. We all miss you at the theater. I’ve told the manager you have the grippe.”

Again Betsy’s eyes widened in fear. “Did he believe you?”

“He was just scared that we’d all get it. He told me you’re to stay away until there is no danger of contagion. Now, get to sleep. I’ll be by again tomorrow. I hope your new nurse isn’t an ogre.” With a laugh and a wave, she left the room.

As she sat in her carriage and resumed her ride home, she told herself to forget about Betsy’s problems for the moment. She herself needed to get her beauty sleep. Tomorrow she would be having dinner with the Duke d’Alvergny. He had been very attentive at the theater for several weeks, and she had fobbed him off.

But she’d made some inquiries and discovered him to be extremely wealthy and influential.

She had spoken the truth to Betsy. Romantic attachments were dangerous, but a gentleman with the right connections and a generous pocket was always worth a second look. Perhaps it was time to see what the duke had to offer.

“Come watch Punch and Judy! Watch Punch knock out Judy! Tuppence a show.” The hawker’s voice carried above the crowd. A young boy tugged on Ian’s hand.

“Oh, may we watch?” The other children took up the chorus.

Ian turned to Jem as the children shouted their glee. “I guess Punch and Judy will be next.” The two men shepherded the children they’d brought from the dispensary neighborhood toward the puppet theater.

Ian fished out his change and gave the money collector the fee.

As the hunchbacked Punch whacked his wife, Ian’s attention wandered. His glance strayed to Jem. The youth seemed as entranced by the small puppet show as the children they’d brought to the street fair.

Leaving Jem laughing heartily at the high-pitched voice of Punch screaming at Baby, Ian looked over the crowd. The streets were packed with people for the annual Southwark Fair. It would be the last one until the winter carnivals.

His gaze was arrested by a small commotion about half a block down. As a few people shifted, providing an opening, he saw what held their attention.

Mrs. Eleanor Neville was holding court. There was no better way to describe the scene before him. Those around her fawned over her, as she graciously bestowed her favor to all and sundry. She smiled, offering her hand to men, women and children alike.

As if on cue, she moved on, ready to greet those farther on. The crowd parted, men doffing their high-crowned hats, women fluttering their handkerchiefs, children clamoring for a last-blown kiss.

She was with another young woman. As they came closer, her attention was drawn to the noise of the Punch and Judy show. Her face lit up and she turned to her companion. At that moment her glance crossed Ian’s.

He thought she wouldn’t recognize him in that crowd, but she raised an eyebrow and he inclined his head in acknowledgment. She said something to her companion and to his surprise, the two started walking toward him.

“Good afternoon, Mr. Russell. I’m surprised to see you at such an entertainment. Who is minding the dispensary?”

He smiled sheepishly, aware of the people around them eyeing him curiously. “My partner.”

She smiled. “I confess I find myself perplexed. You have no liking for the theater, yet here I find you at a fair.” Her lips formed a pretty pout. Ian struggled to shift his focus away from them.

He nodded at the young children around him. “I’ve brought some of the children who usually spend their time in the streets around the dispensary.” At that moment Jem turned around and his eyes grew wide at the sight of Mrs. Neville. He made his way to her side.

“Mrs. Neville! What a pl-pleasure,” he said, holding out his hand, then drawing it back again as if unsure that was the proper thing to do.

Mrs. Neville laughed charmingly and held out her own hand. “The pleasure is mutual. It is good to see you again, Mr. Beverly, under more cheerful circumstances.” She introduced them to her companion, a chorus member from the Royal Circus.

Ian, impatient with the curiosity of the crowd around them, said, “I think Punch is becoming angry with our drawing attention away from his show.”

Mrs. Neville turned to the puppet stage. “I love Punch and Judy. I started out playing at street fairs, you know.” She stood at his elbow, so close the sleeve of her dress brushed his arm, and it became even harder to keep his attention on the show than before.

When the show ended, somehow he found himself part of Mrs. Neville’s entourage. She charmed the children, and their group moved along slowly through the jammed streets, stopping at the various stands.

She ended up walking at his side as Jem and the other actress moved in front of them with the children.

“What do you have there?” Mrs. Neville gestured to the bag in his hand.

“Cardamom seeds,” he answered. He held out the bag to her, wondering if she would find the gesture unrefined.

Instead she removed her glove and took one. She chewed on it and smiled. “It’s spicy.”

He felt captivated by that smile, revealing such purity and sweetness. “I got in the habit of chewing on them when I was first apprenticed to my uncle. His apothecary was a treasure of spices and sweet-tasting lozenges for a kid. He told me to eat these instead of the sweets. Better for my teeth and breath, he advised.

“During the war, they helped alleviate the boredom on long marches across the plains of Spain and fooled the stomach into thinking it had been fed.”

“You were with the army?”

“As surgeon.”

Jem stopped in front of a booth with a dartboard. The hawker immediately challenged them to try for the prizes. The children clamored for Jem and Ian to win them one.

Jem was unsuccessful after three attempts. Ian paid the man in charge and took his three darts. Like Jem’s, his darts landed far from the bull’s-eye. He turned to the children with a shrug. “Sorry, no prizes today.”

Mrs. Neville gave him a coy smile. “I hope your stitches in surgery are better than your aim.”

Her silvery-gray eyes were looking up at him in teasing challenge, and it occurred to him she was flirting with him.

He was accustomed to receiving unwanted attention from the many street women he attended in his practice, but they were derelict and only incited his pity. The heartfelt gratitude he received from other female patients or mothers of children he’d treated humbled him and made him all the more aware of the sacred trust between physician and patient. The only other women he dealt with were at the mission or chapel, modest and respectful in their comportment toward him.

Mrs. Neville’s behavior was different. It was direct and demure at the same time, elegant and playful in one.

“Mr. Russell is the finest surgeon.” Jem defended him immediately. “You wouldn’t want anyone else if you were going under the knife.”

She chuckled, a sound rich and charming like warm caramel. “I’ll try to remember that when I need someone to cut me open and stitch me up. Now, I’ll show you how to win a prize.” She turned to the children. “Let’s see, how many are there of you?” she asked the children as if she hadn’t seen already. “Three only? That means one prize for each.”

They yelled in excitement. Calmly, she turned to the man at the booth. “I shall need three darts, if you please.” She gave him a coin and received her three darts.

The children began hopping up and down, pointing to the things they wanted to win.

“Now, you must hush.” She put her finger to her lips and bent toward them. “Be very, very still so I can concentrate and win your prizes for you.” Wide-eyed in wonder, they promptly fell silent. Ian couldn’t help smiling at the immediate obedience Mrs. Neville’s words invoked in the children. At the same time he wondered if it was wise getting their hopes up.

She turned to the dartboard and hefted the three darts in her hand, as if determining their weight. She chose one and brought it up level to her face, pointing it toward the round board. The crowds behind were forgotten as the attention of their party was focused on the black center of the dartboard.

Breaths held, they watched as, after an interminable few seconds, she threw the dart.

It arced, then descended and, with a soft thud, landed firmly within the bull’s-eye. The children erupted in shouts of triumph.

She paid them no attention, as her hands once again toyed with the remaining darts.

“Beginner’s luck! Beginner’s luck!” the owner of the booth chanted. “Let’s try for two in a row. Can’t make two in a row.”

Other patrons, waiting for their turn, took up the chant. The noise brought more people to the booth.

Mrs. Neville ignored them as she took aim again. The crowd fell silent as if collectively holding its breath.

Another tense few seconds went by, before whoosh and bull’s-eye.

The cheers were louder this time. Some of the children couldn’t contain their excitement, but jumped higher, clutching at the railing of the booth. Ian glanced at the owner of the stand, who was the only one not looking pleased at the victory.

“Here, now, you watch it,” warned the owner sternly to the boisterous children. “I don’t want my stand comin’ to pieces.”

Ian gently held them back from the railing and told them to be still for the last turn.

Mrs. Neville moistened her lips briefly, the only sign that she was feeling anything other than perfectly calm. The last dart was held lightly in her fingertips. Slowly, it rose to eye level.

It flew through the empty space and landed at dead center, right between the other two darts.

The crowd shouted and applauded.

“I never seen such an aim. And a lady, too!”

“That’s the actress, Eleanor Neville.”

“She’s a wonder.”

“Amazing.”

As if oblivious of the compliments being thrown around her, she bent down to the three children and asked them to tell her which toys they wanted. They pointed to the desired objects. She turned to the stern-faced proprietor, who had taken out the darts and held them in his hand, and calmly told him her choice of prizes.

With a jerk, he took the toys off the shelf and slammed them on the counter, a Bartholomew baby doll for the girl, a wooden dog covered with patches of fur for one of the boys, and a yo-yo for the other.

The children grabbed them and chattered happily as they were led away by the adults.

“You’ve made a few children happy for the day,” Ian remarked as they continued down the street.

“You say they hang about the dispensary.”

“Yes. The whole neighborhood is full of children.” She made no reply. “Mrs. Neville, where did you learn such an accurate aim?”

She smiled. “Oh, I’ve thrown a lot of darts in my life. I told you I started out my career at street fairs.” She nodded up ahead. “See the acrobats? I was cutting capers and walking on ropes since I was fourteen. We traveled from village to village and town to town. There was ample time to play darts at taverns or just nail the board to a tree when we had to camp out on a meadow.”

He listened, finding it hard to imagine such a fashionably dressed young lady up on a makeshift stage doing acrobatic tricks.

They ambled down the street, stopping frequently. The children watched in awe a juggler tossing balls in the air. Another player balanced a ball at the end of a stick.

“I’ve done it all. Even equestrian feats. That’s how I started at the Surrey.”

“And now?”

“Now? I have lead roles in the melodramas, only we mustn’t call them melodramas, only burlettas, or we might lose our license. The royal theaters at Drury Lane and Covent Garden are the only ones permitted to put on straight dramatic works.”

“I didn’t think there was much difference,” he said drily. He knew enough of the theater to know that in recent years the Drury Lane and Covent Garden were known to put on bigger and bigger extravaganzas instead of pure classical dramas.

“Strictly speaking, anything the minor theaters put on must be set to music, with no spoken lines permitted. But you’re right, there is less and less distinction between the majors and minors. Still, we must watch how we bill our performances or we could be shut down.”

A pastry vendor came by, swinging the tray suspended from his neck back and forth. “Tasty hot pasties. A ha’pence each, penny for two. Come and have a meat pasty!”

Ian stopped the man and bought the children each a bulging meat pastry. He turned to Mrs. Neville. “Would you care for one?”

“No, thank you. I eat very little before a performance.”

He eyed her critically. She seemed much too fragile to him. “You can’t mean to say you starve yourself during the day.”

“I have been recently following a regimen of only fruit and vegetables on a performance day and tea laced with honey and lemon for my throat. I only dine after the show.”

“You certainly don’t look as if you needed to follow such a strict regimen.” He offered her his pastry.

“I shall only take a bite since it looks so tempting.” She broke off a corner of the warm pastry he held out to her.

“Thank you, it’s delicious,” she told him after she’d swallowed it and daintily wiped her mouth with her lace-edged handkerchief. As she looked up at him, he was struck afresh by the color of her eyes. It was the clear gray of the mist hanging over the sea at dawn.

He cleared his throat, too dazed by his reaction to her to formulate any more complicated response than “You’re welcome.”

They stopped at another booth, this one selling all sorts of trinkets. After Jem had bought a pair of fans for the two ladies, he turned to present one to Mrs. Neville.

“I c-can’t believe I’m really h-here walking with a famous actress. How do you do such amazing things on the stage, from pretending you—you’re a pirate to a princess—”

She laughed as she took the fan and opened it with a flourish. “Haven’t you heard that ‘all the world’s a stage’? You live in one. Look around you. There are all kinds of dramas taking place right under your nose.

“Take that couple for instance.” She motioned with her fan to a stout couple standing at the next booth. “You can tell by their gestures alone that he missed his target and now she is berating him for wasting his money and not getting her a prize.”

“You’re right,” Jem told her in amazement. He burst out laughing when the colorfully dressed woman turned to the man and scolded him for his clumsiness. “How did you notice them?”

She shrugged. “I take those things I see and use them on the stage—the irate wife, the distressed husband, the lost, frightened child.” She stopped talking and, fixing her eyes on Ian, stared hard at him for a few seconds.

“Wot? Don’t you see the draggle-tailed duck in front o’ yous? Can’t you ’it the bleatin’ target? I didn’t come to the fair so you could lose all our brass. What kind of a big looby are you?” She turned to Jem and the actress with a nod. “Gor, if it’d been my first ’usband, Alf, never a better man, if ’e’d ha been ’ere, ’e’d ha’ knocked down a dozen ducks already.”

Jem and the children were doubled over in laughter, and the younger actress was clapping her hands in glee. Ian couldn’t help but smile. He was as captivated as Jem by Mrs. Neville’s ability to capture the scene they’d witnessed only briefly at the next booth.

It struck him that this beautiful woman was as close an observer of human drama as he was of a sick body in order to diagnose it properly.

“Come, we’d better keep moving before they notice us,” she said, once more in her natural tone. She placed her hand in the crook of his elbow, and Ian looked down at the kid glove, wondering at how natural it felt to have it resting there.

They walked along, following Jem and the children. Mrs. Neville’s young friend had attached herself to Jem, and Ian watched in amusement as Jem blushed and stammered his replies to her.

A moment later Ian turned to an angry voice up ahead.

“They take away the food from a man’s mouth. They make us fight for the king, then put us on the street when we come ’ome!” A dirty, disheveled man wearing an old army jacket, stood waving a crutch and shouting to the crowd. One foot ended in a filthy, wrapped stump.

Ian felt Mrs. Neville’s hand tighten on his arm as she noticed the speaker. “Poor man,” she murmured.

The speaker soon had a group gathered around him, raising their hands and shouting back in agreement.

They stood watching him for a couple of minutes, but then the mass of people attracted by the angry veteran began pressing uncomfortably around them.

“It sounds like a disgruntled soldier,” he answered briefly. “It could get ugly. People have been drinking.”

Mrs. Neville looked worried. “Perhaps we should turn around. The children—”

“Yes.” Ian raised his voice to get Jem’s attention. Unfortunately, the young man had been drawn to the excitement ahead, and Ian had to squeeze through the growing crowd to reach him.

“Jem, hold up.”

“Yes? What—oh, it’s you, Ian.”

“I think we should leave this area.”

By this time the voices had grown louder and angrier and people began jostling and pushing to get closer.

A rock flew over the crowd and glass shattered. As if a signal to erupt, the crowd took up whatever was at hand and began throwing things. Men swung their canes around, unmindful of who stood in the way. Women flung their handbags and umbrellas, children screamed.

In a matter of seconds, they were in the midst of a full-blown riot.

Chapter Four

The crowd took up rocks, clubs and sticks and directed the brunt of their violence at the booths and the shop windows around them.