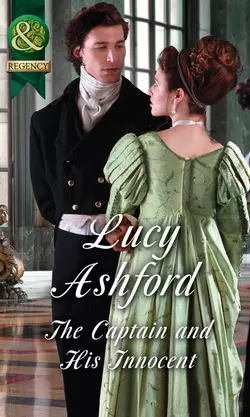

The Captain And His Innocent

The Captain And His Innocent

Lucy Ashford

In bed with the enemy!The war is over, Napoleon is in exile and Ellie Duchamp’s world is changed for ever. Now, embroiled in a web of espionage on the Kentish coast, Ellie finds herself at the mercy of a dangerous but intriguing stranger – ex-army captain Luke Danbury.In a world ruled by danger and deception, it’s hard to know who to trust. But, try as she might to remind herself that Luke is her enemy, innocent Ellie cannot help but respond to the craving she senses in the Captain’s kiss!

‘Ellie,’ he broke in. ‘You talk a little too much.’

‘And I won’t allow you to silence me!’

‘Won’t you?’

She gasped. Because he was lifting the fingertips of his left hand to let them trail across her full mouth, brushing away a tiny cold snowflake that had landed there, then letting the pad of his finger travel on down to her deliciously pointed little chin.

And he leaned in and kissed her.

Just a touch. That was all Luke ever intended. Just one brief, sweet meeting of lips—but the joining of their mouths, her soft skin against his, sent lightning bolts through him, astonishing him. He saw that her eyes were closed, realised that her lips were slightly parted, and his heart drummed, his loins pounded. She was wonderfully sensual—and she was an innocent. Stop there, Luke ordered himself. God help him, everything about her shouted a warning for someone like him to stay well clear.

But he didn’t.

Author Note (#ulink_306b1000-6dbf-5d63-b658-fe2c8afdcd76)

You’ll see that this book is set in 1815, in the months before Waterloo, and my heroine, Ellie Duchamp, is a French refugee who has been sent by her English relative Lord Franklin to the safety of his mansion in Kent.

But nearby is the run-down estate of disreputable ex-army captain Luke Danbury, whose brother has been lost in France and labelled a traitor. As soon as Luke discovers the secret of Ellie’s past he ruthlessly resolves to blackmail her and dig out the truth about his brother—but he hasn’t reckoned on the sparks of attraction that fly instantly between the two of them!

The lonely Kent coast is beset by rumours of smugglers, intrigue and French spies. On the same side now, Luke and Ellie battle to uncover the truth—but can they really have a future together when the exposure of Ellie’s past might very well ruin them both?

Here is their story, which I really hope you’ll enjoy.

The Captain

and His Innocent

Lucy Ashford

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

LUCY ASHFORD studied English with History at Nottingham University, and the Regency is her favourite period. She lives with her husband in an old stone cottage in the Derbyshire Peak District, close to beautiful Chatsworth House, and she loves to walk in the surrounding hills while letting her imagination go to work on her latest story.

You can contact Lucy via her website: lucyashford.com (http://lucyashford.com).

Contents

Cover (#u7c1b5a9e-9a2a-552c-8f0f-f7503c4a7019)

Introduction (#uaaa84c75-c03c-5be6-9083-475659b1cb50)

Author Note (#u4f4ccf6d-e263-588a-a16a-70c30cea201e)

Title Page (#u7c1c6248-ebd6-5709-88f2-69abe801913e)

About the Author (#ue26656eb-3ea5-5bad-90ae-2ab7bcb0cc2c)

Chapter One (#u6556dce7-bb9c-51ca-bf5b-cc7791733d39)

Chapter Two (#u1daa4b37-d8fd-54a8-85e6-eddb2abffb22)

Chapter Three (#u2d59e250-3d86-5d67-98ab-0612255e29c0)

Chapter Four (#ue01e5385-8952-5add-88ba-add3c754756f)

Chapter Five (#u27511723-59b2-5d85-80b3-5c4644ba9cae)

Chapter Six (#u7b4fd2e7-44d1-5928-bc9b-1158ca0b7ecb)

Chapter Seven (#u58e28177-4cbf-556b-ac42-eb93e80e5d71)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#ulink_967c37db-b38e-5050-aae1-ac4f69d8142e)

Kent, England—1815

In the grey light of a January afternoon, two dark-clad men stood on a lonely shingle beach gazing out to sea. ‘Soon we won’t be able to see a thing out there, Captain Luke,’ muttered the older one restlessly. ‘This wretched mist that’s rolling in is as thick as the porridge they used to give us in the army.’

‘Be grateful for that mist, Tom.’ Luke Danbury’s eyes never shifted from the forbidding grey sweep of the sea. ‘It means the Customs men won’t spot Monsieur Jacques’s ship out there.’

‘I know, Captain. But—’

‘And I wish,’ Luke went on, ‘that you’d stop calling me Captain. It’s over a year since you and I left the British army. Remember?’

Tom Bartlett, who had a weatherbeaten face and spiky black hair, glanced up warily at the taller, younger man and clamped his lips together for all of a minute. Then he blurted out, ‘Anyway. I still think you should have sent me as well as the Watterson brothers to bring in Monsieur Jacques. It would be just like the pair of them to lose their way out there.’

‘Would it?’ Luke’s face held the glimmer of a smile. ‘While you and I were soldiering in the Peninsula, Josh and Pete Watterson were in the navy for years—remember? Those two don’t lose their way at sea, whatever the weather. They’ll be here soon enough.’

Tom looked about to say something else; but already Luke was walking away from him to the water’s very edge, a low sea breeze tugging at his long, patched overcoat and his mane of dark hair.

‘Well,’ Tom was muttering to himself as he watched him, ‘I hope you’re right, Captain. I hope those Watterson brothers will row the French monsieur to shore a bit faster than their wits work.’ He glanced up at the cliffs behind them, as if already picturing hostile faces spying on them, hostile guns pointed at them. ‘Because if the Customs men from Folkestone spot us, we’ll be clapped in irons fast as we can blink, you and me. And that’s a fact.’

The other man stood with his hands thrust in his pockets, studying the mist that rolled ever thicker across the sea. As if his gaze could penetrate it. As if he could actually see the coast of France; could even perhaps picture the far-off place where last year his brother had vanished without trace.

Bitterness filled Luke Danbury’s heart anew. He clenched and unclenched his gloved right hand, thinking... News. He had to have news, one way or another. He was tired of waiting. He needed to know—for better or worse.

Behind him Tom Bartlett, once his loyal sergeant-at-arms, had started grumbling again softly, but broke off as Luke shot out his hand for silence.

Because Luke’s sharp ears had registered something. And, yes—a moment later, he could see it, a rowing boat slowly emerging from the mist, with two men pulling at the four oars, while another man in a black coat and hat leaned forward eagerly from the bow. Tom was already wading into the shallows, ready to reach out a hand to the black-clad passenger and help him ashore as the boat’s keel grated on shingle. ‘There we are now, monsieur!’ Tom was calling in welcome. ‘You’ll enjoy being back on dry land again, eh?’

‘Dry land, yes.’ Jacques laughed. ‘And with friends.’

Tom preened a little at that praise, then turned to the Watterson brothers, who were making the oars secure; brothers who looked so like each other, with their mops of curling brown hair, that they might have been twins. ‘Well, you rogues,’ declared Tom. ‘I always said the navy’s better off without you. You took that much time, I thought you’d lost your way and rowed to France and back.’

The brothers grinned. ‘The army’s certainly better off without that gloomy face of yours, Tom Bartlett. Though you’ll cheer up a little when you see what’s weighing down our boat.’

‘A gift from Monsieur Jacques?’ Tom was nodding towards their passenger, who was already deep in conversation with Luke Danbury a few yards away.

‘A gift from Monsieur Jacques.’ The brothers, after dragging the boat even further up on to the beach, were reaching into it to push aside some old fishing nets and haul out a heavy wooden crate. ‘Brandy,’ they pronounced in unison. ‘Monsieur Jacques rewards his friends well. Come on, you landlubber, and give us a hand.’

* * *

‘My men have dropped anchor out there for the night,’ Monsieur Jacques was saying to Luke. ‘A good thing you caught sight of us before that mist came down, my friend. A good thing that your Customs men didn’t.How long is it since I was here?’

‘It was late October.’ Luke’s voice was level.

‘As long ago as that...’ Jacques glanced at the men by the boat and gave Luke a look that meant, Later, my friend. When we are alone, we’ll talk properly. Then he went striding across the shingle to where Luke’s men had placed the crate of brandy, withdrew one bottle with a flourish and uncorked it with his penknife.

‘Here’s to the health of the valiant fishermen—Josh and Peter Watterson!’ He raised the bottle and drank. ‘To the health of Tom Bartlett! And most of all to your own very good health, Captain Danbury!’

Jacques passed the bottle across to Luke’s right hand—but Luke swiftly reached to take the bottle with his left, which, unlike the other, was ungloved. His eyes were expressionless.

‘Pardon.’ Jacques looked embarrassed for a moment. ‘Mon ami, I forgot.’

‘No matter.’ Luke’s voice was calm, though a shadow had passed across his face. ‘To the health of everyone here. To freedom’s true friends, in England and in France.’

‘To freedom’s true friends!’ echoed the others.

Luke drank and handed the bottle back to Jacques. ‘And may justice be some day served,’ he added, ‘on the British politicians in London, with their weaselly words and broken promises.’

‘Justice.’

‘Aye, justice, Captain.’ One by one, the little group on the shore by the cliffs passed round the brandy bottle, echoing his toast sombrely.

At last Luke turned to Tom. ‘I intend to take Jacques up to the house for the night, of course. But before we set off, I want you to check the road for me, Tom.’

‘The London road, sir?’

‘Exactly. I want you to make sure there are no spies around. No government men.’

Already Tom was on his way, hurrying along the beach to a path that climbed steeply up the cliff. The Wattersons still hovered. ‘Josh. Peter,’ Luke instructed, ‘I’d like you to take that brandy to the house and warn them there that our guest has arrived.’

‘Aye, Captain.’ They set off immediately.

And so, with the afternoon light fading, and the sea mist curling in and the cries of the gulls their only company, Luke and the Frenchman were alone. And I’m free, thought Luke, to ask him the only question that really matters.The question he’d asked of so many people, so many times, for the past year and a half.

‘Jacques, my friend.’ He was surprised that his voice sounded so calm. ‘Is there any news of my brother?’

The Frenchman looked unhappy. Uncomfortable. Luke’s heart sank.

‘Hélas, mon ami!’ Jacques said at last. ‘I have asked up and down the coast, as I sailed about my business. I have asked wherever I have friends, in every harbour from Calais in the north to Royan in the south. And—there is nothing.’ The Frenchman shrugged expressively. ‘Your brother disappeared with those other men at La Rochelle in the September of 1813. Sadly, many of them are known to have died. As for your brother—we can only hope that no news is good news, as you English say.’ His face was taut with sympathy. ‘But I do have something for you.’

Reaching into the inside pocket of his coat, he handed Luke a small packet wrapped in oilskin. Luke, cradling it in his gloved right hand, peeled it open with his left—until at last a gleam of colour flashed in his palm. Ribbons. The glitter of brass. War medals, engraved with the names of battles: Badajoz, Salamanca, Talavera. Luke felt fierce emotion wrench his guts.

He looked up at last. ‘Where did you get these?’

‘From an old French farmer’s widow. She found them lying half-buried in one of her maize fields—she has a small farm that adjoins the coast near La Rochelle. Realising they were British, she gave them to me, and asked me to get them home again. They could be your brother’s, couldn’t they?’

Luke nodded wordlessly. They could. But even if they were,he told himself, this doesn’t mean he’s dead. He might still be alive over there. A prisoner, perhaps. Needing my help...

He mentally rebuked himself, because he’d suddenly noticed the dark shadows beneath the Frenchman’s eyes and realised how weary he was despite his outward cheerfulness.

‘We’ll have time enough to talk later,’ Luke said. ‘I would be honoured, Jacques, if you would come to the house, to dine with us and stay for the night as usual.’

‘Gladly—though I must leave before dawn tomorrow. It’s not safe for my crew to keep the ship at anchor once daylight comes.’ Jacques gripped Luke’s shoulder almost fiercely. ‘You know that I’ll do anything I can to find your brother. I owe you this, mon ami, at the very least—’

He broke off, realising at the same moment Luke did that Tom Bartlett was back, his feet crunching on the shingle. ‘There’s travellers on the high road, Captain!’

‘Revenue men?’ Luke’s voice was sharp.

‘No, Captain, it’s a fine carriage. With two grooms as well as the driver, and luggage aplenty strapped on the back.’

Luke felt his lungs tightening. ‘Does it look as though the carriage has come from London, Tom?’

‘Aye, that would be my guess. Can’t make out the coat of arms on the door. But the horses, they’re Lord Franklin’s all right—I recognised the four fine bays that he keeps stabled at the George Inn close to Woodchurch.’

‘And is Lord Franklin in the carriage?’

‘I caught sight of a middle-aged woman and a younger one, by her side. But was his lordship in there as well?’ Tom shook his head. ‘I couldn’t see and there’s the truth of it.’

Luke made his decision—he needed to know exactly who was in that carriage. ‘Tom, see Monsieur Jacques up to the house, will you? I’ll join you as soon as I can.’ Even as he spoke, he was already setting off along the beach, towards the path Tom had followed.

Tom guessed his intention and was aghast. ‘You’ll never catch up with those four bays of Lord Franklin’s!’

Luke turned calmly to face him. ‘They’ll have to stop, Tom. Don’t you remember that half the road’s fallen in a little beyond Thornton, after that heavy rain a week ago? Lord Franklin’s coachman will have to take that particular stretch of road very slowly, or he could risk breaking a wheel. There’s woodland I can take cover in. I’ll be able to observe the carriage and its occupants at leisure.’

‘But if Lord Franklin is in the carriage, Captain, what are you going to do?’

Luke let the silence linger for a moment. ‘Don’t worry. I’m not going to kill him. At least—not yet.’

And with that, he turned his back and once more headed swiftly towards the cliff path.

Tom sighed and smiled resignedly at Jacques. ‘Well, monsieur,’ he said, ‘let’s be off up to the house, shall we? There’ll be logs burning on the fire and my good wife will have a pot of stew keeping hot on the stove. And thanks to you, we’ve brandy to drink...’ He hesitated. ‘I take it there’s no news yet of the captain’s younger brother?’

Jacques shook his head. ‘No news.’

‘Then we can still hope,’ said Tom, ‘that he’ll turn up safe and well!’ He set off once more, cheerful at the prospect of hot food. But Monsieur Jacques, following behind, looked sombre.

‘Safe and well?’ he murmured under his breath. ‘Sadly, I doubt it, my friend. I doubt it very much.’

Chapter Two (#ulink_261a515b-c587-5e8b-9213-736d1c6cf3ee)

Ellie Duchamp, nineteen years old, gazed out of the carriage window at the alien English countryside and remembered that she had hoped to travel to Bircham Hall on her own. To have the time, and the silence perhaps, to come to terms with all that had happened to her in the last few months.

But she had had no period of grace in which to contemplate how or why her life had changed so rapidly, ever since Lord Franklin Grayfield, wealthy English aristocrat and collector of art treasures, had found her in a garret room in Brussels. Ever since, he had told her she was his relative and would thenceforth be in his care.

No time or silence—far from it—because beside her in the carriage was the female companion Lord Franklin had provided for her, Miss Pringle, a very English spinster, who had arrived at Lord Franklin’s Mayfair house a few days ago. Who could not conceal her excitement at being entrusted to escort Ellie to his lordship’s country residence, Bircham Hall, in the county of Kent.

Yesterday, as they prepared for their noon departure, Lord Franklin himself—middle-aged, polite as ever—had stood outside his magnificent London mansion in Clarges Street to watch as Ellie’s trunk was strapped to the back of his coach. Miss Pringle, as she took her leave of his lordship, declared ardently that she would take as much care of Ellie as if she were her very own daughter. And Ellie soon realised that to her new companion, taking care meant one thing only—talking.

All the way through London, Miss Pringle had talked. She had talked through the city’s suburbs and through the green fields beyond Orpington. She had talked all the way through their halts at the various coaching inns where the ostlers raced to change Lord Franklin’s horses.

Ellie had told Miss Pringle at their very first meeting that she understood English perfectly well; but Miss Pringle insisted on speaking slowly and enunciating every syllable with the greatest care. And Ellie was being driven to the limits of her patience.

Lord Franklin had announced that although the journey to Kent could be achieved in one day, he felt Ellie would be more comfortable with an overnight stop at the Cross Keys in Aylesford. Ellie had hoped that the evening meal they took in the private dining room there might silence her companion a little, since Miss Pringle keenly enjoyed her food. But somehow, Miss Pringle managed to eat a substantial amount and also produce as many words as ever at exactly the same time.

‘Of course,’ Miss Pringle pronounced, ‘Lord Franklin has always honoured my family with his esteem, Elise.’

Elise was Ellie’s French name, the name she’d been christened with. Her French father and English mother had always called her Ellie; but she didn’t trouble to correct those who preferred to call her Elise, since they were strangers, who knew nothing of her life or her past.

‘My dear father,’ Miss Pringle went on through a mouthful of ham and peas, ‘was the vicar of Bircham parish, you know, for many years. And since my papa’s sad death, Lord Franklin—well, no one could have been kinder, or more considerate! It was a great sadness for me to have to leave the Vicarage on Papa’s demise—but Lord Franklin understood perfectly. He said to me, “My dear Cynthia, we cannot have you leaving Bircham, when you have been such a valuable part of its life for so many years.” Those were his exact words! And in the end, Lord Franklin found me a cottage—the very best of cottages, I might add!—in a most superior part of Bircham village. I have really been more than comfortable there, and of course I have had my many charitable works to keep me busy.’

Miss Pringle leaned closer. ‘But when I heard from Lord Franklin that he wanted me to come up to London to accompany you to Bircham Hall itself and to live there as your companion—well, I was so very honoured. To think, Ellie, that he is your long-lost relative! And as you’ll know, he is off travelling again very shortly. Taking advantage of the end of this horrid war with France to go and observe the art and classical buildings of Paris. Lord Franklin is forever travelling and enlarging his wonderful collection of artistic treasures. Which is, of course, how he met you. In Bruges, was it not?’

‘In Brussels,’ Ellie replied tonelessly, pushing aside her plate. ‘If you have no objection, Miss Pringle, I am rather tired and would like to withdraw to my bedchamber now.’

* * *

But the next morning, at breakfast, the inquisition started again.

‘So...’ Miss Pringle began, over her toast and marmalade, ‘Lord Franklin came upon you in Brussels. But to think, that he should turn out to be your mother’s second cousin—you could not have wished for a luckier stroke of fate!’ Suddenly her eyes fixed on Ellie’s shabby travelling cloak and dowdy bonnet and she said, a little more hesitantly, ‘You know, I was led to understand that Lord Franklin generously furnished you with a quantity of new clothes in London.’

‘He did,’ Ellie answered. ‘But I prefer to travel in more practical clothing.’

‘Very wise.’ Miss Pringle nodded. ‘Very wise, since you will find, I think, at Bircham Hall that practicality is of the utmost importance.’

Ellie wanted to ask her what she meant. Was it chilly there? Was it uncomfortable? But it couldn’t, surely, be as frugal or cold as some of the dire places she’d taken shelter in during the last year or more. And then it was time to go out to where the carriage stood in the yard of the inn.

There, the ostlers, under the careful eye of the coachman, were harnessing up four beautiful greys, and Miss Pringle saw Ellie gazing at them. ‘Lord Franklin keeps only the best, of course,’ she declared, ‘at each posting house. This is our next-to-last change, I believe, and by this afternoon we shall be at Bircham Hall. How my heart lifts at the thought! And there you will meet Lady Charlotte, who is sure to give you a wonderful welcome...’

Was it Ellie’s imagination? Or did Miss Pringle’s confident tone falter just a little at the mention of Lord Franklin’s widowed mother?

‘My mother,’ Lord Franklin had told Ellie, ‘used to come to London occasionally, but never does so now. I have sent word to inform her that you will be arriving at Bircham Hall and have asked her to ensure you will be happy there.’

But how will Lady Charlotte really feel? Ellie was wondering rather wildly as the carriage rolled on through the Kent countryside. How can she relish the prospect of having a nineteen-year-old French girl—a penniless orphan—suddenly foisted upon her?

One thing was for sure—Ellie would know soon enough.

* * *

They made slow progress, as slow as the previous day. Miss Pringle talked on as the road led them up and down hills, past farms and the occasional village, past fields of sheep, and dark woodland.

And then, soon after the final change of horses, Ellie could see the sea. The afternoon light was fading, and from the far horizon a low mist was rolling in across the expanse of grey waves; but even so, she pressed her face to the carriage window, realising that between the shore and the road lay a bare expanse of heathland. She glimpsed the sturdy tower of a small and ancient church, and nearby stood a lonely old house with sprawling wings and gables, set on a slight rise and shrouded by stunted sycamores.

She craned her head to gaze at it, but the carriage was entering woodland again and the house had already disappeared from view. A house of secrets, she suddenly thought.

Ellie, her father would have fondly said. You and your imagination.

A sharp pang of renewed loss forced her to close her eyes. By the time she opened them again, the carriage had rounded the next headland and the sea was visible once more. Down below was a cluster of little houses around a harbour, with an inn and a wharf where fishing boats were tied up and men mended their nets.

Miss Pringle was still talking about Lord Franklin. ‘His family—the Grayfields—can, I believe, trace their ancestry back to Tudor times...’

Ellie glanced down at her small black-leather valise on the carriage floor. She wondered what Miss Pringle would do if Ellie were to seize her valise, jump out of the carriage, run down to the harbourside and beg one of those fishermen to take her away from England’s cold and hostile shores. I am homesick, she thought with sudden anguish. Homesick for the Paris of my childhood. For the happy times I spent there with my father and mother. I’m even homesick for Brussels, where I endured those last desperate months with my poor, dying papa.

‘Oh, look at that mist.’ Miss Pringle was shuddering. Ellie realised her companion was looking out of the window also. ‘And soon it will be dark. January. How I hate January. It’s this sort of weather, they say, that brings out the smugglers. Lord Franklin does his very best to stop their obnoxious trade, but they are desperate renegades. It’s even said they’re in league with the French—and after all, on this part of the coast, France is less than twenty miles away.’

The fishing village was no longer in sight. The road was heading inland again to carve its way through thick oak woodland, and Miss Pringle talked on. But suddenly she cried out in alarm.

‘What is this? Gracious me. Why have we stopped?’

Ellie noted the fearful expression on her companion’s features. Highwaymen, that expression said. Robbers. Murderers. ‘Please,’ said Ellie. ‘Calm yourself.’

By then one of the grooms, distinctive in Lord Franklin’s navy-and-gold livery, had appeared at the window of the carriage. ‘Begging your pardon, ladies, but it appears that half the road ahead of us has fallen away, no doubt because of the recent rain.’

Miss Pringle put her hands to her cheeks. ‘Oh, my goodness. Oh, my goodness...’

‘No reason at all to be alarmed, ma’am,’ said the groom hastily. ‘But we need to do a bit of repair work to make sure the way’s safe for Lord Franklin’s horses. It’ll take us ten, perhaps fifteen minutes—no more.’

The moment he’d disappeared, Ellie leaned forward. ‘Miss Pringle?’

‘Yes?’ Miss Pringle had got out her smelling salts and was sniffing vigorously.

‘I think I will take advantage of our halt to get a little fresh air.’

‘But you took a walk less than an hour ago, Elise, when we last stopped to change the horses! And very soon, we’ll be at Bircham Hall. Can you not wait? Besides, I’m not sure it’s safe for you to wander hereabouts, I’m really not sure at all.’

But Ellie had already opened the carriage door and was jumping down to the road, with her cloak wrapped tightly around her.

* * *

Although it was not yet four, a fierce chill was starting to pierce the air. And the mist! The mist she’d seen out at sea was rolling in across the land now, blanketing the woods that surrounded them with its clammy and sinister air. Though if she looked hard, she could still just see the road ahead. Could see, too, where the left-hand side of the road’s stony surface had fallen away, into the verge that bordered it.

That, Ellie, is the problem with insufficient drainage, she could almost hear her father saying. And look at the lack of proper foundations! You cannot build a road for heavy traffic merely by throwing a haphazard layer of rocks on top of mud. And of course the Romans knew it was often necessary to dig deep ditches on either side to take away the winter floods...

At least Lord Franklin’s two grooms were well equipped for emergencies like this. Her father would have approved of that. The grooms couldn’t see her, standing as she was in the shadows beyond the coach; but she could see that one of them had an axe to hew down the nearby saplings, and as fast as he felled them, the other was spreading them across the damaged part of the road to create a surface that would—at least temporarily—bear the weight of Lord Franklin’s coach and horses.

And as she watched them working, she realised what they were saying.

Pretty little piece, isn’t she, the girl? And she speaks good English, for a Frenchie.

Well, her mother was English, I’ve heard. An English trollop, who ran off with a Frenchman.

I wouldn’t mind running off with that one...

Ellie’s cheeks burned. So often. She’d heard the same vitriolic gossip so often. Head high, she walked away from them, back down the road they’d come along—and only when she was completely out of sight of both the carriage and the grooms did she stop, realising that her eyes were burning with unshed tears.

It is the cold air, that is all, she told herself fiercely, dashing them away with her hand. The cold.

She walked on, remembering seeing the sea and that fishing village. In what direction, she wondered suddenly, did the coast of France lie? South? East? Almost instinctively, she reached deep into the capacious pocket sewn to the inside of her cloak to pull out a small leather box.

And jumped violently as a tall figure loomed out of the shadowy woods ahead of her. The box fell to the ground, somewhere in the undergrowth beside the road.

‘If I were you,’ the man was saying calmly, ‘I wouldn’t run. There’s really not much point, I’m afraid.’

What he meant was that there wasn’t much chance of escape. From him. Ellie fought her stomach-clenching fear. This man was tall. This man was powerful. Hampered as she was by her heavy travelling clothes, she’d never make it back to the carriage before he caught her. What was he? A highwayman? One of the local smugglers, perhaps, that Miss Pringle had fretted about?

He certainly didn’t look like a law-abiding citizen. His long coat appeared to have been mended over and over again; his leather boots were spattered with mud, as if he’d walked a long way. Stubble roughened his strong jaw, and his dark wavy hair was unkempt, but his eyes were bright blue and knowing.

A man to be afraid of. Her heart was already pounding wildly; but she forced herself to speak with equal calmness. ‘You may as well know,’ she said, tilting her chin, ‘that I have nothing about me of any value. If you’re intending to rob me, you’re wasting your time.’

His eyes glinted. ‘I’m not here to rob you. I’m merely curious. I’d heard that Lord Franklin has a new ward—and you must be her.’

What was it about his voice—his deep, husky voice—that sent fresh pulses of alarm tingling through her veins? And how had he heard that she was coming to Bircham Hall?

‘I am not Lord Franklin’s ward,’ she answered. Keep your breathing steady, Ellie. Look at him with the disdain he deserves. ‘But there is a family connection. My mother was his relative...’

He came closer. Panicking, she took a step back. ‘Indeed, mam’selle,’ he said softly. ‘to find yourself suddenly in the care of a rich and aristocratic Englishman must have seemed like a fairy tale come true. Lord Franklin is said to be a great collector of foreign objets d’art. And what could be more fitting than for him to return from the Continent with a pretty French girl in his care?’

She felt her breathing coming tight and fast. She had been a fool, indeed, to have wandered so far from the coach. Play for time, she told herself. Play for time.

‘You are mistaken,’ she said steadily, ‘if you think that I would allow myself to be...collected. Lord Franklin took me in his care out of duty, that is all. In other words—no fairy tale. And unless you wish me to assume that your own intentions are unworthy, monsieur, I would ask you to let me pass—this minute!’

She’d already started to move. But he was quicker, stepping sideways to block her path, intimidating her with his height and the breadth of his shoulders.

‘Did you realise,’ he said, ‘that Lord Franklin was a relative of yours before you met him, I wonder?’

She was momentarily overwhelmed by the hard, purposeful set of his face. By the brightness and intensity of those blue eyes. No. No, she didn’t.

Memories whirled around her. Memories of a badly furnished attic room above a bread shop in Brussels. Memories of her father lying on a narrow mattress while she bathed his forehead, desperate to cool his fever. The bread-shop owner, the Widow Gavroche, hurrying upstairs to her. ‘Mam’selle, mam’selle—there is an English gentleman here to see you! His name is Lord Franklin Grayfield and he is very fine!’

Ellie had been alone, with no friends and no money. In danger there. She had thought that she’d left danger behind her now that she was in England—but this tall man who’d come prowling out of the mist reminded her otherwise.

She had to get away. But that little box...

Letting her eyes sweep downwards, she spotted it suddenly in the undergrowth. She made a swift move towards it, but he was quicker, and before she could stop him, he had stooped to pick up her small leather box for himself.

Ellie felt the blood leave her face. ‘That is mine. Give it back to me!’

He gave her a curious half-smile—and ignored her. Her heart was hammering so hard against her ribs that it hurt. He’d picked up the box with his left hand, she noticed—held it there in his palm, while with his right hand he was turning it slowly.

He wore a black glove on his right hand. And there was, she realised, something odd about it. Something wrong with it. The first two of his fingers were missing. But he had no trouble opening the box. And Ellie felt slightly sick, as the brass casing of her father’s compass gleamed in the half-light.

‘A pretty trinket,’ he was saying approvingly as he gazed down at it. ‘It must be worth something.’

‘Perhaps it is. Perhaps it isn’t.’ Ellie was sliding her hand into the folds of her cloak. ‘But, monsieur, if you’ve any sense at all, you will return it to me—immédiatement—or I swear you will regret it.’

His eyes gleamed. ‘You’re going to make me?’

For answer she lifted the small pistol she had in her hand and released the safety catch. She was pointing it straight at his heart.

His body tensed very slightly, but his eyes still glinted with mockery. ‘Mam’selle,’ he reproved. ‘Really. To go to such extremes... I take it you know how to use that thing?’

His voice. The rich, velvety timbre of it. Every word he spoke made something shiver down her spine in warning. Made her grip the pistol even tighter. ‘Do you want to find out?’ She forced her voice into absolute calmness. ‘Give me the compass back. Or I shoot.’

He watched her, his eyes assessing her. Then suddenly he laughed and held the compass out with a small nod. Ellie grabbed at it, her pulse pounding.

‘An unusual object,’ he said calmly. ‘A valuable object, I would venture to say.’ He swept her a mockery of a bow. ‘Our meeting has been interesting—but I’ll make no further effort to detain you. And I hope your stay at Bircham Hall is a pleasant one. Your servant, mademoiselle.’

And he was gone. Into the mist and woodland. As suddenly, and as silently, as he’d appeared.

She found she was gasping for breath, as if the air had been kicked out of her lungs. She remembered the gleam in his blue eyes as he gazed at the compass. Dieu. Had he had time to look at it? To really look at it?

With an enormous effort at self-control, she secured the safety catch on her pistol, then slipped it and the compass back into the pocket inside her cloak.

She hurried towards the carriage, willing her heart to stop thudding. Please God, the compass had only attracted his attention because he thought it was something he could sell. But surely he was no ordinary roadside thief. Who was he? And how did he already know so much about her?

She drew a deep, despairing breath. The answer to that was easy. Bircham Hall, Miss Pringle had frequently pointed out, was the largest and most prestigious house in this part of Kent. The staff would all have been warned of Ellie’s arrival and they would doubtless have spread the news around the neighbourhood.

That was how he knew. And he’d been watching for the coach, guessing it would have to stop there; hoping for a chance perhaps to rob its occupants. She’d provided him with the perfect opportunity, by wandering away down the road.

A common thief. That was the obvious answer. And yet she had a feeling that his intentions were somehow far, far more dangerous than that.

She could see Miss Pringle now, standing outside the carriage, visibly fretting. She let out an exclamation when she saw Ellie. ‘There you are. I’ve been imagining all sorts of terrible things...’

‘I’m all right, Miss Pringle,’ Ellie soothed her. ‘Really I am.’

Just at that moment a groom came up to inform them that the carriage was ready to set off again. And for the remainder of their journey to Bircham Hall, Ellie closed her eyes and pretended to be asleep.

But she couldn’t erase the image of the man with the maimed right hand and the dangerous blue eyes. Something strange and unfamiliar tingled through her body. Fear? No—she’d known fear often enough, and fear didn’t make your pulse race at the memory of a man’s face, of his dangerous smile. Fear didn’t make you notice a man’s thick dark lashes. Didn’t make you remember the magical curve of his lips when he smiled and make you wonder how many women he had kissed.

She would be safe at Bircham Hall, she told herself. She would have no friends, but she would be safe. And the man was surely nothing but a lowly ruffian.

Then she shivered. Because she was remembering that the stranger in the long, patched coat had spoken not like a ruffian, but like an English gentleman—and his voice had melted her insides, even though every word he spoke was either a veiled insult or a threat.

Sharp waves of panic were clawing at her throat. She’d thought she would be out of danger, when she reached England’s shores—but clearly, she could not have been more wrong.

Chapter Three (#ulink_9ad46816-0e44-57b8-8c01-bcbcadb57977)

The dusk always fell swiftly along this part of the coast, blurring the lonely expanse of gorse-topped cliff and the miles of shingle beach. There were still ghostly reminders of the now-ended war with France, for in the distance was a rugged Martello tower, built in case of a Napoleonic invasion, and sometimes soldiers rode out from Folkestone to patrol the coast; though they were more likely nowadays to be hunting for smugglers rather than invaders.

Just enough light lingered for Luke to see that both headland and beach were deserted, though he could hear gulls crying out above the waves. Still on foot, he had left the woods and the road well behind him now, taking instead the ancient paths used by local fishermen and farmers until he came at last to a rough track that led to a solitary house looming up from behind a thicket of wind-stunted sycamores.

The house was said to have been built on the site of an ancient long-vanished fortress, constructed over a thousand years ago to protect this coastland from Germanic invaders. Now wreaths of mist shrouded it, whispering of past lives and of ancient battles. The locals said it was haunted; said that the fields which surrounded it, blasted by winter winds, were good only for the most meagre of crops and the hardiest of sheep. But Luke loved this landscape with a passion that was ingrained in his very being.

He loved the winters, when frost and snow shrouded the bare countryside, and howling winds blew in from the sea; winds so cold they might have come straight from the freezing plains of Russia. He loved the summers, when the fields were filled with grazing sheep and lambs, and birdsong filled the nearby marshlands from dawn till dusk.

His brother, Anthony—two years younger than he—had loved it all, too.

Anyone seeing the house from a distance would think it derelict, but the locals would tell a passing stranger that it was the residence of Luke Danbury, a spendthrift and a wastrel who had once been a captain in the army in Spain, but who had now mortgaged his family estates to the hilt and was anyway absent for much of the time, doing God knew what.

Making madcap, mysterious sea voyages, he’d heard people say. Up to no good. Away as often as hewas here. Gambling, probably, and women, they muttered knowingly. Once he was engaged to an heiress—and didn’t she have a lucky escape! He’s let all his farmland, once so prosperous before the war, go to waste. And his missing brother’s a disgrace as well. The family name is ruined...

The track led up to the front gate of the house, which stood permanently open. Indeed, such was the tangle of undergrowth—old, half-wild shrubs and ivy growing all around—that Luke doubted it could ever be shut. The house itself looked uninhabited; no lights shone from any of the front windows, and wreaths of sea fog crept around the gables and turrets. But Luke pushed his way through the wreck of a garden and past the twisted sycamores, towards the courtyard and stables round the back—and there, glowing lantern light welcomed him.

There, the cobbles were well swept, with stacks of logs for burning, and bales of hay for the horses, all neatly piled under shelter. Several farms belonged to the estate, and the equipment for the usual winter jobs had been gathered there also for his tenants to collect: tools for fencing and ditching work, shovels and pickaxes.

He noted it all automatically; yes, this what he had to concentrate on now. Saving the estate. Saving the livelihoods of the men, and their families, who depended on him. But all the time, he was thinking, too, that the rumours were true—that Lord Franklin Grayfield had returned from abroad with a French girl. An orphan, they said, and a distant relative, whom Lord Franklin had taken into his care.

But Lord Franklin, as far as Luke knew, was not a man given to sudden, sentimental gestures of generosity. So why go to the trouble of bringing this girl—this relative—back to London? And why did Lord Franklin almost immediately decide to banish the girl to the Kent countryside?

Of course, there would be gossip aplenty for Luke to listen to and sift through for himself, in the taverns of Bircham Staithe harbour, or in the larger ale houses of Folkestone a few miles away. There always was gossip about a rich, clever and ultimately mysterious man like Lord Franklin. There was already gossip about this girl, too—Luke had heard from people who’d glimpsed her in London that her name was Elise Duchamp and that she was pretty, in a French sort of way. But they hadn’t told him that she went around carrying a pistol in her pocket and quite clearly knew how to use it. No one had mentioned that.

And as for ‘pretty’—was that the way to describe her rich dark curls, her full mouth and slanting green eyes? Was it her mere prettiness that had sent a jolting kick of desire to his blood—and had urged him, with age-old male instinct, to draw her slender body close, so he could feel the feminine warmth of the curves he just knew would lie beneath that old, shapeless cloak?

She was intriguing, in more ways than one. There was considerably more to her than met the eye. Take, for example, that compass.

Luke Danbury let out a breath he hadn’t even realised he was holding. He was passing the stables now, mentally registering that the horses were secure for the night. A couple of them gently whickered as he paused to stroke their noses, murmur their names. A moment later he was opening the stout door that let him in to the back of the house, inhaling the familiar scents of stonework and smoke from the fires as he walked through the flagged hall to the low-beamed dining room at the very heart of the old building.

The sound of cheerful voices told him before he even entered that Tom, the two Watterson brothers and Jacques had settled themselves extremely comfortably around the vast oak table, eating Mrs Bartlett’s hot beef stew and drinking some red French wine.

Eagerly they welcomed Luke and pulled out a chair for him, while Mrs Bartlett, Tom’s wife, came hurrying from the adjoining kitchen to ladle out a dish of stew for him. Jacques poured Luke a glass of the wine.

‘What detained you, my friend?’ asked Jacques curiously. ‘We were beginning to think you might have gone into town, to find yourself a pretty girl.’

Tom was blunter. ‘Did you find out if Lord Franklin was in the coach?’

‘He wasn’t.’ Luke drank half his wine and put his glass down. ‘Apparently he’s still in London.’

‘Then who were the girl and the old woman?’

‘The girl’s a relative of Lord Franklin’s. The other one’s her companion, I believe.’

Tom nodded wisely. ‘Ah. The orphan he’s said to have taken into his care—which must have been a surprise to everyone, cold-blooded fish that he is. I heard rumours that she’s pretty. Is she?’

‘She certainly does her best not to be.’ No more. No need to say any more.

‘She’s French, they say,’ announced Josh Watterson eagerly. ‘That’s interesting.’

‘Maybe.’ Luke poured himself more wine and the others concentrated again on their food—all except for Jacques, who was watching him sharply.

Monsieur Jacques, Luke’s men called him. He’d been a soldier, captured by the English and condemned to rot as a prisoner of war—until Luke freed him. ‘And I pay my dues,’ Jacques liked to explain to Luke’s companions. ‘I help my friends as they help me.’

It was to pay back his debts that Jacques now ran his small sailing ship with skill and bravado between the coasts of France and England on dark and misty nights such as this. But Jacques was frowning in puzzlement as he pushed his empty plate aside and said, ‘Why, my friend Luke, would Lord Franklin suddenly discover a young French relative? Why didn’t he know of her before? Surely, wealthy families such as his have their ancestry well documented for generations back?’

‘That’s true.’ Luke paused in eating his meal. ‘Their family lines are guarded as thoroughly as their fortunes, to prevent interlopers from getting any of their money.’

‘That’s exactly what I thought. Has the girl taken his fancy, do you think?’

Luke let out a bark of laughter at that. ‘Highly improbable. They say Lord Franklin hasn’t touched a woman since his wife died ten years ago—and he wasn’t overfond of her, by all accounts.’

Jacques smiled. ‘So a liaison of some sort is out of the question. But why did he go to the trouble of bringing her to England? And why—having claimed her as his responsibility—would he banish her to Bircham Hall?’

‘When I have the answers, I’ll be glad to share them with you.’

‘Indeed,’ the Frenchman said. ‘So you’re going to make enquiries, are you? Should I perhaps begin to wonder if this French demoiselle of Lord Franklin’s is more interesting than you say?’

Luke savoured his wine before putting the glass down. ‘Totally uninteresting,’ he said. ‘Too young and too proud, I imagine. Besides, I have more than enough to deal with at the moment.’

‘With your estate and your farms? I hope I sense optimism?’

Just then Mrs Bartlett came bustling in to clear away the used dishes, and Tom and the Wattersons stated their intention of carrying out their usual evening tasks. Luke sat back in his chair and took his time answering Jacques’s question. ‘I’m not sure if it’s optimism, or foolishness. I’ve found some new tenants for the farms—but do you know how much the price of English grain has dropped in the last year? I’ll be keeping the men busy, it’s true, but it might all be for nothing.’

‘You’re not wishing you’d married your heiress?’

‘Hardly. That ended almost three years ago. She’s marrying someone else in spring—someone her father considers far more suitable—although my tenants might wish I had her money to throw around.’

Jacques shook his head. ‘You’re giving them something better than money, Luke. You’re giving them hope, and you’ve got to remember that.’

Luke looked around bleakly. ‘I’m postponing bankruptcy, that’s all. I must by now have sold off everything of value that’s ever belonged to my family.’

‘You can still fight for your family’s honour. Not with sword or pistol, it’s true—but you know as well as I there are other ways. I’m going back to France tomorrow—and if your brother’s still alive, I will find him, I swear.’

Tom Bartlett came in, with more logs for the fire. ‘You’re talking about the captain’s brother?’ he said eagerly. ‘Who knows—he might even turn up here one day, right out of the blue. I can just see it, Captain Luke—he’ll ride up the track, bold as ever, and tell us all his adventures, just like he used to.’

Jacques nodded approvingly. ‘That’s the spirit. Let’s raise our glasses to the captain’s brother. Let’s wish him a safe journey home!’

‘To Anthony,’ they echoed. ‘A safe return.’

* * *

Gradually, the fire died down. Midnight came and went; they talked of battles they’d fought and comrades they’d known until at last, knowing they must rise well before dawn, they went off to their beds.

All of them except Luke.

The big house was quiet enough now for him to hear the whisper of the wind in the trees outside and the faint hiss of the waves breaking on the long shingle beach below the cliffs. Somewhere in the distance a nightbird called.

He went to stir the embers of the fire, lifting the metal poker with his maimed right hand by mistake. Fool. Fool. The heavy implement clattered on the hearth. He picked the poker up almost savagely with his left hand and jabbed at the logs until they roared into life.

Damn it. He was of no use to anyone, least of all to himself. He ripped off the black leather glove and stared at the two stumps where his fingers had been. The scars had almost healed, and as for the ache of the missing joints—well, he was used to it.

What he could not grow used to was the feeling that his younger brother—who’d relied on him, who’d trusted him—was lost for good. Was dead, like the others. By hoping that Anthony had somehow survived, he’d made the final blow ten times as bad for himself.

Again and again during these last few months, he’d cursed his injured hand, because it had stopped him sailing to France with Jacques and hunting the coast for clues or answers. He couldn’t use a pistol, or a sword; wasn’t even much use at helping sail a ship. But perhaps Fate was telling him that he should turn his mind to other matters.

Perhaps Fate was reminding him that the answers he was seeking could also lie here, in England, not in France at all. Perhaps Fate was telling him that here, he could find out what had really happened to Anthony and his brave comrades. Why they had been betrayed—and by whom. Even though such secrets were as closely guarded as rich men’s fortunes.

He thought again of Lord Franklin Grayfield, a rich widower in his late forties; a remote, clever man who had a son out in India whom he hadn’t seen for years. Lord Franklin Grayfield, who cared far more for his art collection, it was said, than for female company.

Yet he’d claimed an unknown French girl as his

relative—the girl Luke had met that afternoon. Harshly, he dismissed his memory of the light lavender scent that emanated, ever so faintly, from her creamy skin. Harshly, he thrust aside his awareness of her downright vulnerability and the haunting sadness in her eyes. Instead, he told himself to remember the pistol she’d handled so deftly and so purposefully—as if in mockery of his own injury.

Caroline used to squeal in girlish horror at any mention of the war and weapons. But the French girl had that dainty gun and looked as if she knew how to use it. What kind of life had she led, before coming to England? And if the pistol had startled him, what in God’s name was he to make of the compass she’d dropped?

Once again Luke remembered the astonishing inscription that he’d seen engraved upon its side—he found that his heart was speeding at just the thought of it. He also remembered the look on her face as she’d snatched it from him. No wonder she was so eager—so very eager—to get it back.

Who was she, really? And what in hell was she doing here, under Lord Franklin’s so-called protection?

Chapter Four (#ulink_200bb3c8-d665-5c27-89b9-16558af29ec6)

Ellie, too, was still awake, sitting alone by the window in the icy spaciousness of her bedroom in Bircham Hall. It was past midnight. But she couldn’t sleep, because this was a day she would never, ever be able to forget.

After the repair to the road, Lord Franklin’s carriage had made swift progress, its driver no doubt eager to make up for the delay. They’d left the main road to pass through some gates by a well-lit lodge, after which they followed a long private drive; Ellie had seen how the carriage lamps picked out clumps of winter-bare trees set amidst grassy parkland.

And as they crossed the bridge over a river, she had her first view of the Hall—stately and foursquare, with flambeaux burning on either side of the huge, pillared entrance, as if in defiance of the January night.

Lord Franklin’s country residence. It was magnificent. It was haughty and forbidding. ‘Oh, look,’ cried Miss Pringle, who was peering out of the window, too. ‘Here we are at last, Elise. And I see—goodness me!—that all the staff are outside, waiting to greet you!’

Indeed, Ellie had seen them all there in the cold: the maids in black and the footmen, straight as soldiers, clad in Lord Franklin’s livery of navy and gold.

All waiting for her. Ellie’s heart sank.

But Miss Pringle practically bubbled with excitement. ‘Such an honour for you!’ she murmured as the grooms hurried to hold the horses and lower the carriage steps. ‘Such a very great honour! And look—here is Mr Huffley, his lordship’s butler...’

‘Miss Pringle. Mademoiselle.’The butler made a stiff bow to them as they descended from the carriage. ‘It is my pleasure, mademoiselle,’ he went on to Ellie, bowing again, ‘to welcome you most heartily to Bircham Hall. Allow me to present our housekeeper, Mrs Sheerham. Our cook, Mrs Bevington. The senior housemaid, Joan...’

The maids curtseyed to her, the footmen bowed their heads to her; all politeness, all decorum, despite the fact that their breaths were misting in the chilly air. For their sakes Ellie got through the ceremony as quickly as she could, then followed Mr Huffley up the stone steps to the house.

And only then did she remember that there was somebody else she had yet to meet.

‘Lady Charlotte will be expecting you,’ Miss Pringle was whispering at her side. ‘I declare, I cannot wait to see her ladyship again.’

The entrance hall was huge and cold, its walls hung with coats of arms and stags’ heads. All kinds of statues stood on either side of the hall: reclining figures of smooth white marble, stone busts set on pillars, precious relics that must, Ellie realised, have come from the ancient civilizations of Greece or Rome or Egypt.

It was a proud house, thought Ellie to herself with a shiver. All these priceless objects from the past seemed to be there to declare the history, wealth and importance of those who dwelt there. And in the midst of all this, as if claiming her own right to be a part of the grandeur, was a lady in her early seventies, with a lace-trimmed cap perched on her iron-grey hair and a gown of black. She sat in a bath chair. Two footmen were on either side of her, standing stiffly to attention.

‘Your ladyship...’ breathed Miss Pringle to her, sweeping an extravagant curtsey.

And Ellie was suddenly dry-mouthed as she made a low curtsey also. Nobody had told her about the bath chair. Nobody had told her...

She rose from her curtsey, aware that Lady Charlotte was raking her with hard eyes. ‘So you must be Elise Duchamp,’ she said, distaste for the foreign name etching every syllable. ‘I am Lord Franklin’s mother. I gather he has decided to banish you to Bircham? So much, I imagine, for your hopes of trapping my son into marriage.’

Ellie was shocked not just by the nature of the attack, but by its vicious suddenness. Never—never had she thought of Lord Franklin in that way. Dieu du ciel, he was surely over twice her age! ‘I do assure you, my lady, that nothing could be further from the truth!’

Lady Charlotte wheeled herself close, forcing Ellie backwards. ‘Are you really telling me that you never intended to make him your prize? Some people might—just might—believe you. I don’t, as it happens. Just remember, Elise—I shall be watching you.’

Her ladyship glanced up at Miss Pringle. ‘It’s almost five o’clock. I hope, Pringle, that you’ve shown some common sense for a change, and told the girl that we dine at six? We do not indulge in town hours here.’ She beckoned to the two footmen, who throughout all this had stared blankly ahead. ‘Take me to my room. Now.’ And Ellie watched speechless as the footmen wheeled the elderly lady away.

How could she have allowed herself to be brought here—trapped here like this? Why had she entrusted herself to these people?

Yet how could she have resisted her father’s last desperate plea as he lay dying? You must go with him, Ellie, to England. You must.

‘Papa,’ Ellie had argued. ‘We don’t know him. We cannot be sure.’

But her father had insisted. Lord Franklin will keep you safe, as I have never been able to, he’d said. Promise me...

Miss Pringle still hovered, all of a flutter. ‘What an honour for you, Elise,’ she was saying brightly. ‘How wonderful to be welcomed to Bircham by Lady Charlotte herself.’

But her hands were trembling, and Ellie realised that Miss Pringle was afraid of Lady Charlotte. Terrified, in fact. And then the housekeeper was there—Mrs Sheerham—saying to Ellie, ‘May I take you to your room, ma’am?’

Ellie followed her, quite dazed.

* * *

She found that she had been allotted a spacious suite on the second floor. Her trunk and valise had already been brought up and placed in the bedroom that adjoined the private sitting room.

She went over to them quickly, to check that the valise was still firmly locked. Looking round, she noted that thick curtains were drawn shut across all the windows; fires had been lit in both rooms and a dozen or more wax candles banished the darkness. The luxury of it all stunned her.

‘I hope everything is to your taste, ma’am?’ Mrs Sheerham was still standing by the door.

‘Yes. Thank you, it’s—it’s wonderful.’

‘Very good, ma’am.’ Mrs Sheerham’s expression softened just a fraction with the praise. ‘You’d no doubt like some tea and someone to help with your unpacking? I’ll see that a maid comes up to you shortly.’ She left and Ellie began to slowly remove her cloak.

Lady Charlotte hates me. She never wanted me here.

She’d barely had time to lay her cloak on the bed, when there was a knock at the door, and a girl in a black dress and white apron entered hesitantly.

‘My name is Mary, miss!’ She bobbed a curtsey. ‘Mrs Sheerham, she asked me to come up and see to you. And I’ve brought tea for you.’ Mary darted out again and came back in with a tray of tea things, which she set down on a small table in the sitting room, while Ellie stood back, hoping the girl wouldn’t guess that—before being taken under Lord Franklin’s wing—she had never had a personal maid in her life.

‘Now, while you drink your tea,’ Mary went on, ‘I shall start to unpack your clothes, shall I?’ Her eager eyes had already settled on Ellie’s trunk and valise, then fell a little. ‘But is that all?’

Ellie knew that most ladies of quality travelled with so much luggage that often a separate carriage was required for it. ‘There’s only the one trunk, I’m afraid, Mary,’ she answered quickly. ‘And, yes, I’d be grateful if you would unpack it.’

‘And what about the bag—?’

‘No,’ Ellie cut in. Mary was staring at her in surprise. ‘I mean,’ Ellie hurried on, ‘that there’s very little in the valise. My clothes are all in the trunk. So if you would put them away, I would be most grateful.’

‘Of course, miss!’ Briskly Mary set about unpacking Ellie’s clothes and hanging them in the wardrobe, or folding them into the various chests of drawers that were ready-scented with sprigs of dried lavender. As she did so, she exclaimed over the silk gowns, the velvet pelisses, the exquisite underwear. ‘Oh, miss. Are all these from Paris?’

Ellie shook her head. ‘They’re from London. Lord Franklin was kind enough to arrange for a modiste to make them for me.’

Mary gazed longingly at a rose-pink evening dress. ‘I don’t know when you’re going to wear these things here, miss. It’s a cold house, is Bircham Hall. And Lady Charlotte, she doesn’t have many guests or parties, exactly...’

‘It doesn’t matter,’ Ellie said quickly. ‘I’ve never been interested in parties or clothes.’

‘No, miss? But it’s such a shame that you’re going to be so quiet here. Now, if you’d stayed in London... Mr Huffley told us that in London there are lots and lots of French people like yourself, who had to run for their lives when that monster Napoleon became Emperor of France. Napoleon sent armies marching all over Europe, didn’t he?’

‘Yes.’ Ellie’s voice was very quiet. ‘Yes, he did.’

Mary had paused to admire an embroidered silk chemise before folding it meticulously in a drawer. Then she nodded. ‘But now, Napoleon’s locked up good and proper, on that island in the Mediterranean. Miles from anywhere. And our clever politicians and Lord Wellington will see that he never, ever gets free. Are you quite sure you don’t want me to unpack that valise for you, miss?’

‘Quite sure. And I think that is all, for now.’

But Mary’s eyes were still scanning the room. ‘Your cloak!’ she said suddenly. It was still on the bed, where Ellie had laid it. ‘It will be dusty after your journey. Shall I take it downstairs and brush it out for you?’

‘No!’ Ellie had already taken a step forward, to stop her. ‘No. That will be all, Mary.’ She forced herself into calmness. ‘Thank you so much.’

‘You’re very welcome, miss. You’ve not drunk your tea yet! Never mind, I’ll collect the tray later.’ Reluctantly, Mary took one last look around. ‘It’ll be time for you to go down to dinner soon. You’ll hear the bell ringing downstairs, ten minutes before six. Oh, and her ladyship doesn’t like anyone to be late.’ Her bright voice dimmed, just a little. ‘Most particular, her ladyship is. Most particular.’

Mary let herself out. And as soon as her swift footsteps faded into the distance, Ellie leaned back against the closed door and thought, I should never, ever, have allowed myself to be brought here. She hurried across to her cloak and, reaching deep into the inside pocket, drew out her pistol and the compass in its box.

She clasped them to her.

The man. The man, on the road... She could still remember how she’d felt, standing there with him so close, so powerful and dangerous. She would perhaps never forget the way her pulse had pounded when he smiled at her.

She had to forget him. As she hoped he would forget her. You will never see him again. You must erase him from your mind.

Drawing a deep breath, she laid the pistol and compass on the bed. Then she unfastened the silver chain round her neck, feeling for the small key that hung from it, and with that key she unlocked her valise. In it were several maps and charts, carefully folded, and below them were more objects, each in black velvet wrappings. She opened them one by one.

A surveyor’s prism. A miniature folding telescope. A magnifying lens, with an ebony handle. A tiny geologist’s hammer.

She wrapped them up again and put them back at the bottom of the valise. Put the pistol and compass in there, too, then the documents on top of them all.

She knew she ought to lock the valise again and hide it from sight, but instead she withdrew one of the folded documents and spread it out, carefully.

She translated the title into English, under her breath. A map of the valley of the Loire, showing its geology. Devised and drawn by A. Duchamp, Paris, in the year of Our Lord 1809...

She picked up the map with her father’s signature on it and held it close to her breast as the memories flooded back.

Chapter Five (#ulink_82736323-1365-5ebb-bae9-0f42ed38003a)

Ellie’s father, André Duchamp, was a geologist, surveyor and map-maker. He had lived with his wife and daughter in Paris, close to the church of St Denis in an apartment off the Rue Tivoli, which had a little balcony from where Ellie could look out on to the main street. She remembered being enthralled as a five-year-old child to one day see ranks of soldiers marching by, their tricolours held aloft, and two years later she’d seen Napoleon himself, the newly crowned Emperor of France, ride past at the head of his cavalry on a prancing white horse, acknowledging the cheers of the crowds who’d gathered to see him.

‘He is a great man,’ her father used to say. ‘He will bring peace and prosperity to France again.’

Their apartment was small, but even so, a whole room was given up to her father’s work, and he used to let Ellie watch him while he drew his maps. She was fascinated, too, by the telescopes and star charts he had in there, for he was a keen astronomer. ‘Why should I only map the ground beneath my feet?’ he would say. ‘When there are also the heavens above us to explore?’

Best of all, she loved to gaze at the array of geological samples he kept in a glass cabinet in that room. To Ellie they were as beautiful as any jewels, and her father would tell her about each one.

‘These pink crystals are feldspar, Ellie. Such a delicate colour, don’t you think?’

‘Oh, yes! And the green one, Papa?’

‘That’s olivine. And here’s a piece of hematite—such a dark, deep red that it’s almost black.’

Ellie nodded eagerly. ‘And that one must be gold!’

‘Fool’s gold, alas.’ Her father smiled at her excitement. ‘It’s called pyrites and it’s tricked many a fortune-

hunter.’

She’d gazed at him earnestly. ‘You know so much, Papa.’

He’d ruffled her hair. ‘Ah, but there’s always more to learn, little one.’

‘Is that why you go travelling?’

‘It’s my job, Ellie. I’m lucky to have a job that I love.’

She was always sad when her father was away. He went travelling for days—sometimes even weeks—at a time and only later in her childhood did she realise why he was so busy. It was because his expertise in both geology and map-making meant that he was invaluable in the planning and the physical creation of new roads that were intended to connect all of the cities and ports of France for travellers and traders.

When he was away, Ellie would gaze down the street from her window for his return, waiting for him and missing him. She was only vaguely aware of the wars the Emperor Napoleon was waging on France’s borders and beyond. But as the years went by, her father was away more and more often, for longer periods of time, and when he returned, his mood was often heavy, sombre, almost—though he always smiled to see his daughter.

When Ellie was seventeen, her mother died. She’d been ill for only a short while, and her father was brokenhearted. And that was truly the end of their old, familiar way of life, because one night, a few weeks after the funeral, Ellie found her father packing all his precious things into his leather valise. She saw how his face was etched with grief, how his hands trembled as he put them on her shoulders and said, ‘Ellie, my darling, we must flee Paris, you and I. This city is no longer safe for us.’

* * *

It made her almost smile to remember how in Brussels Lord Franklin had expressed his fear that the journey to England might exhaust her, because Ellie was used to the kind of journeys Lord Franklin probably couldn’t even imagine. She was used to travelling under a false name, and often by night; sometimes in mail coaches if they had the money, and in farm carts or on foot if they hadn’t.

They’d headed for Le Havre first, where her father had once had relatives—only to find that they’d long since disappeared, in the upheavals of revolution and war. After several cold and lonely weeks, her father came home one day with the heavy news that they were still being pursued—and so their travelling began again and they headed north.

If they felt they were safe—if they’d gone for a day without suspecting anyone was on their tail—they would treat themselves to a room in an inn for the night, even if the room was flea-ridden and furnished only with a couple of lumpy, straw-filled mattresses. More often they had to sleep in barns, or ruined cottages—places left derelict by years of war.

And Ellie had to be the strong one, because already her father’s health was failing. She had to do things she’d not have believed possible—become a liar, a thief, a fighter, even. Her father had taught her to use that small but lethal pistol, and though she’d never been forced to fire it, she’d made it plain to anyone who threatened their safety that she would—and could—shoot to kill.

She’d had to plan their route, make the decisions, and find—or steal—medicines for her ailing father, who was becoming weaker and weaker each day.

‘Soon we will be safe, Ellie,’ he would murmur each night, as he carefully unpacked his valise and checked his precious instruments. ‘Soon we will be able to stop running at last.’

For her papa, the running had indeed ended. He was dying of pneumonia in Brussels when Lord Franklin came to them—Lord Franklin Grayfield, a wealthy middle-aged English aristocrat who travelled abroad a good deal, he told Ellie in fluent French, because he was fascinated by European culture and art, and was eager to add to his collection of paintings and sculptures. To his great regret, he had been thwarted in his travels by the long war. ‘But now,’ he told her, ‘I am making up for lost time.’

He was clearly rich. He was also ferociously clever. And never in her life had Ellie been so astonished as when he told her, in the Brussels attic where she lived with her dying father, that her mother was a distant relative of his.

Ellie had been astounded. A relative? But her mother had told her that her English family had disowned her completely when she told them she was marrying a French map-maker.

‘How I wish I’d known this earlier,’ Lord Franklin said earnestly. ‘I’m afraid it’s only a few weeks ago that I was making some family enquiries and learned your mother had died; learned, too, that she had a daughter. I vowed to find you, although I wasn’t sure how. But my search for antiquities happened to bring me to Brussels. And you can imagine my surprise, to find out by chance in the marketplace that living here was a gentleman from Paris called Duchamp, whose wife was English and who had a daughter.’

Ellie had listened to all this with her heart pounding. Since arriving in this city, Ellie and her father hadn’t troubled to change their name, Duchamp, for it was common enough; but they’d done their utmost to conceal the fact that they were from Paris. And Ellie couldn’t recollect telling anyone, not even Madame Gavroche, their landlady, that her mother was English.

Lord Franklin was kind. He paid for an expensive doctor to visit her father, although it was far, far too late for anything to be done. He paid for the funeral and the burial, and afterwards he had taken her hand and said kindly, ‘You must come with me to England, Elise. And I promise I will do my utmost to make up for the dreadful grief you have had to face, alone.’

He never once asked her why she and her father had left Paris. He was thoughtful, he was generous; but she was wary of his generosity, and of him. Her strongest instinct was to stay in Brussels, in the little apartment above the bread shop, where Madame Gavroche and her son had been so good to her. But her dying father had pleaded with her to let Lord Franklin take her into his care.

What else could she do, but agree?

* * *

And so Ellie travelled to England—first in an expensive hired carriage to Calais, and then on Lord Franklin’s private yacht, across the Channel to Tilbury. And from there, they went on in Lord Franklin’s own carriage to his magnificent house in London. The city astonished her with the magnificence of its buildings, and she was overwhelmed by the elegance of the Mayfair house on Clarges Street in which Lord Franklin resided. And there, every possible comfort was offered to her by her new protector.

She was given her own maid. She was visited in rapid succession by a hairdresser, a modiste and a mantua maker. Soon a selection of expensive and fashionable gowns began to arrive for her. But Lord Franklin seemed—

despite his generosity—to be reluctant to let her meet anyone, or to let her go out anywhere. Once, she had asked him if he was in contact with any of her mother’s other relatives, and he replied, ‘Oh, my dear, most of them have died, or live somewhere in the north. No need to trouble yourself over them.’

Ellie was surrounded by a luxury she’d never known, but she hated being confined in that big house. Nevertheless she was determined to keep her promise to her father. Lord Franklin will keep you safe, as I have never been able to.

But her trust in Lord Franklin was badly shaken when one day she returned to her room after lunch and realised that, in her absence, someone had made a very thorough inspection of all her belongings.

She felt sick with the kind of shock and fear that she’d hoped never to feel again. To anyone else, certainly, there were no outward signs of disturbance—but she, who was used to running, used to hiding, could tell straight away. Someone—surely not her maid, who was a young, shy creature—had been through everything: every item of clothing, every personal effect in her chest of drawers and wardrobe. Ellie even felt sure that each book on her bookshelf was in a different place, if only by a fraction of an inch.

With her pulse pounding, she’d pulled out her father’s old black valise from the bottom of her wardrobe.

The lock was still intact—but if she looked closely, she could see faint scratch marks around it. Someone had been trying to get inside.

She went downstairs to find Lord Franklin. He was out a good deal of the time, either at his club or attending art auctions; but from the housekeeper she learned that, as luck would have it, he was in his study, talking to a man called Mr Appleby, who was, the housekeeper informed her, the steward at Lord Franklin’s country home, Bircham Hall.

Ellie had knocked and gone in.

‘Elise!’ Lord Franklin had turned to her, with his usual pleasant smile. ‘What can I do for you?’

Mr Appleby stood at his side; he was a little older than Lord Franklin, clad in a black coat and breeches, with cropped grey hair and with spectacles perched on the end of his nose. She glanced at him, then said to Lord Franklin, ‘Someone, my lord, has been through my possessions. Has searched my room.’ She’d meant to sound calm, but she could hear a faint tremor in her voice. ‘I would be obliged if you would question your staff. I really cannot allow this.’

Mr Appleby had looked as shocked as if she’d challenged Lord Franklin to a pistol duel. Lord Franklin himself was frowning in concern.

‘This is a grave allegation, my dear,’ he murmured. ‘But are you sure?’

‘I am completely sure. My lord.’

‘You perhaps doubt the honesty of my servants, Elise? You doubt their loyalty to me? Is anything actually missing?’

‘No! But that is not the point...’

Lord Franklin had turned to his steward. ‘Leave us a moment, would you, Appleby?’

‘Now, Elise,’ said Lord Franklin, when Mr Appleby had gone. ‘I’ve been thinking lately that perhaps London does not suit you. I’ve been wondering if you might like to live in my country house in Kent for a while—it’s in a peaceful area near to the coast and it will, I’m sure, be more restful for you than London, after the various ordeals you have endured. Do you have any objection?’

For a single wild moment, Ellie had thought of fleeing the Mayfair house, and of running back to...to where?

His lordship was already opening the door, to indicate their interview was at an end. ‘Bircham,’ he informed her, ‘is barely sixty miles or so from London, which makes it an easy journey, if spread over two days. And you really will be most comfortable there.’ He stood by the open door, waiting for her to agree. Her father’s voice echoed insistently in her ears. Lord Franklin will keep you safe.

She had bowed her head. ‘As you wish, my lord.’

* * *

And now, here she was at Bircham Hall. It was almost six o’clock and dinner would be served shortly. She paced her room in agitation. It must be safer than France,she kept telling herself. And saferthan London, where someone had searched her room—she’d been sure of it. But here, she’d found danger of an entirely different kind.

Lord Franklin’s formidable mother she felt she could deal with. But now, despite the heat of the room, she shivered afresh as she remembered the man on the road—the dark-haired man in the long coat, with the black-gloved hand—holding her father’s compass so casually. Lord Franklin is said to be a great collector of foreign objets d’art. And what could be more fitting than for him to return from the Continent with a pretty French girl in his care?

Ellie gazed at herself in the mirror, seeing her face, with her wide green eyes and dark curls and even darker lashes. Was she pretty? She’d never troubled to think about it. She’d spent months hiding from men who might be hunting her, months concealing her feminine figure with drab clothing, keeping, always, in the shadows.

But now, she remembered the way that man by the roadside had looked at her. She’d been travel-weary and full of foreboding about her future, and the sudden and silent arrival of someone she realised instantly posed as strong a threat as any she’d yet faced should have set fierce alarm bells jangling in her brain. She’d behaved stupidly, by not running straight away, back to the coach—surely he wouldn’t have dared to pursue her?