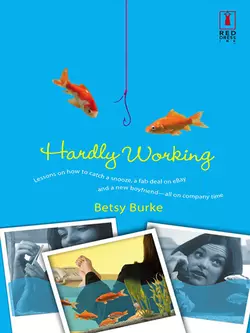

Hardly Working

Betsy Burke

Dinah Nichols, PR chick for Green World International, knows how to spin a story. She has to, otherwise how else would rescuing loons get the media attention it deserves? But a visit from Higher Management guru Ian Trutch means she'll have to put some spin on the "fabulous work" she and the staff have been doing.Sure, her latest hobby of haranguing a cocky colleague is worthwhile, but it isn't part of GWI's mission statement or anything. So, how to convince the higher-ups she and the others are working hard for their higher purpose? Hmm. Dating Trutch seemed the obvious move, but now she's not so sure he is what he says he is, and the office is turned upside down as acts of local ecoterrorism are suddenly on the rise, and Dinah's famed mother–a bona fide well-known Jacques Cousteau type–makes an unforgettable appearance, putting Dinah's entire career in jeopardy.Will Dinah navigate her eclectic crew to safety, or will they have to swim for it?

Hardly Working

Hardly Working

Betsy Burke

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My heartfelt thanks to Yule Heibel and her family, my Canadian and Italian families, Elizabeth Jennings, Jean Fanelli Grundy, Marie Silvietti, Helen Holobov and Kathryn Lye.

For Brock Tebbutt and Joe Average

Contents

November

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

December

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

January

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

February

Epilogue

November

Chapter One

Friday

“So… Dinah. The big THREE OH,” said Jake.

My mind hurtled back from the dreamy place where I’d been idling. I slammed my hand down on the mouse. The Ian Trutch page closed and up came the brochure I was supposed to be working on for the important December fund-raiser. The event would also be an opportunity to award the year’s most generous donors and present the pilot project we’d been trying to push through for the last two years, the ecological aquatic waste treatment system, affectionately nicknamed “Mudpuddle” by those of us at Green World International.

“Hi, Jake.” I swiveled around to look at him.

Jake Ramsey, my boss and the office’s token male, hovered, filling up the doorway to my tiny office. He hid a nervous laugh with a nervous cough. “So…you’ve got your great big thirtieth coming up in a couple of days. How are you going to celebrate?”

“Shhh, keep it down, Jake.”

“What? What’s the problem?”

“That three oh number. I didn’t expect it so soon.”

“Life’s like that. You just turn around and there you are. Older.”

“Terrific, Jake. So who finked about my birthday?”

“Ida.”

“I should’ve known.” As small, sweet and wrinkled as a hundred-year-old fig, Ida worked the switchboard at the front desk. She was the employee nobody had been able to force into retirement. Well past the average employee’s spontaneous combustion age, she was very good at her job. Irreplaceable really. She took half her pay under the table in the form of gossip. It was, she said, excellent collateral.

“Well, don’t tell anybody else,” I whispered. “I was planning on staying twenty-nine for another couple of years.”

Probably too late. If Ida knew then everybody knew.

Jake looked expectant. “Big party planned, eh? You have to have a big party.” His reformed alcoholic’s eyes brightened with longing.

His own thirtieth birthday had sailed by a couple of decades ago, leaving him with a pear-shaped torso and an ex-wife who blamed him for everything from her lost youth to the hole in the ozone layer.

He often let us know that his only passion these days was his La-Z-Boy recliner positioned in front of the sports network. He was immune to women, he said, and no woman would ever trick him again. But Green World International was an office full of women. We weren’t fooled.

“I don’t know about a party. The trouble is,” I said, “my birthday falls on the Sunday, and we’ve got Mr. Important CEO from the East coming in on Monday morning, haven’t we?”

“We sure do. Ian Trutch,” sighed Jake, his features clouding over.

Ian Trutch was higher management. In our office, all higher management was referred to as The Dark Side.

The sudden announcement from the main branch about Ian Trutch had come just the week before and everybody was on edge. Trutch would be arriving in Vancouver to do a little monitoring and streamlining around our office. In other words, there might be a massacre.

As soon as Jake had let the Trutch bomb drop, I’d gone into a state of panic. I wanted to keep my job. The downside of working here was the pitiful wages, cramped ugly offices, weird volunteers, and all that unpaid overtime. The upside was the altruistic goals and the great gang of fellow party anima…uh…employees.

So I immediately Googled Ian Trutch, then called the scene of his last slaughter to try to get information on him. When I finally got Moira, my connection in Ottawa, on the phone, she nearly had to whisper. “Listen Dinah, he’s ruthless…last month there were four more empty desks…lower-level employees. You think they’re gonna touch The Dark Side? No way. I don’t even know if I should be talking to you…Big Brother might be watching…and he has cronies… I’ve gotta tell you what happened to a woman here…uh-oh…one of his cronies has just come sleazing in…gotta go.” The phone slammed down. I sat there a little stunned. I knew Moira was overworked and probably needed a vacation—bad. But four empty desks were still four empty desks.

So maybe he was ruthless. And if his Web-site picture was any indication, he was also first-class material.

Ian Trutch was beautiful.

The beautiful enemy.

Green World International’s in-house magazine had run a long article on him. It stated that Ian Trutch had been hired by GWI to bring the organization into the twenty-first century, that his aim was to make GWI into a smooth-running and profitable machine.

Profitable and machine were two words that did not fit Green World’s profile at all. We were an environmental agency, for crying out loud.

GWI’s current interest was biomimicry, which studies the way nature provides the model for a cradle-to-cradle, rather than cradle-to-grave, use of natural capital, or the planet’s natural resources. Our mission was to redefine “sustainable development,” make it less of an oxymoron, promote biodiversity as a business model, and the idea that a certain kind of agriculture was killing the planet, and that the flora and fauna of a forest or an ocean did not need human intervention or human witnesses to be a success as a forest or an ocean. We were trying to talk world leaders and policy makers into letting the planet’s last few resources teach us all how to live.

Simple, really.

If you happened to be God.

My job was in PR and the creative department, finding as many ways as possible to pry donations out of tight corporate fists. And I was good. My degree in environmental studies enabled me to scare the wits and then the money out of people, because the world picture I painted for the future was scientifically backed up and not pretty. Not pretty at all. And let’s face it. Having a world-famous scientist for a mother may have helped a little. The biggest problem was making that first contact with the right people.

And now there was the whole water business. In the last year since Jake had been promoting the Mudpuddle model to our international counterparts, the office had gone crazy. We’d moved to bigger premises. They were still shabby as hell but bigger. Communications with the other Green World offices, in Moscow, Barcelona, Rome and Tokyo, had been flying back and forth.

And the best part of all? We’d finally found Tod Villiers, the superdonor we’d been seeking. The government was going to match his donation one hundred per cent and it was a sum that ran close to half a million.

Tod was a venture capitalist in his late forties. He was fat, sleek, bald, olive-skinned, and had the most unfortunate acne-scarred skin and bulging pale-brown eyes. But the bottom line was that he loved the project, recognized its worth, and wanted to invest. He’d written a check that amounted to a teaser. So lately, I had to keep his interest inflated until the second and largest part of his donation was processed and his contribution awarded at the fund-raiser in the spring. Because although we’d also received the final check, it was post-dated. I wasn’t worried though.

It did mean that all of a sudden, the spotlight was on us in a way it never had been before. We had begun paying fanatically close attention to anything that had to do with H

O. National Bog Days and World Water Forums were suddenly big on our agenda. Never again would we take a long deep bath, use the dishwasher, jump into a swimming pool, or run the water too long while brushing our teeth, without feeling horribly guilty.

Green World was experiencing a huge growth spurt and this, according to head office, was why Trutch was being sent in. To do a little strategic pruning before the branches went wild.

“Listen, Jake,” I said, “when this Trutch guy arrives on Monday morning, send somebody else out to get the coffee and donuts. Weren’t we going to be democratic about the Joe jobs? Send Penelope.”

Jake perked up and asked, “How are things working out with Penelope anyway?”

A deep, languid female voice broke into our conversation. “Jake, darling, the next time you decide to hire someone who’s good at languages, make sure they’re old enough to drink alcohol and get legally laid first.”

It was Cleo Jardine, GWI’s Eco-Links Officer, and social co-conspirator to yours truly. Cleo is part Barbadian and part Montrealer, a wild-haired woman with coloring that makes you think of a maraschino cherry dipped in bitter chocolate.

She draped a slim dark arm around Jake’s neck and half whispered in his ear, “Little Penelope has a trunk full of brand-new pretty little white things for her wedding night, Jake. She’s got it all figured out. The perfect pristine little life. In any other situation I might find it charming.”

“Huh?” Jake looked slightly startled. Then he laughed. “I know she’s young, but she’s very talented.”

It wasn’t the young and talented part that bothered us.

Well.

Maybe it did.

Just a tiny bit.

“The kind of talent we need in this office,” said Cleo, “pees standing up. And if you had to hire another female, Jake, why couldn’t you have hired somebody with a face like a pit bull but a nice disposition?”

“I couldn’t find a pit bull with her qualifications,” said Jake.

The new talent, Penelope Longhurst, was a very smart twenty-two-year-old. She’d graduated from Bennington College, summa cum laude, at the age of twenty. She was very pretty, too. She had big green eyes and shiny honey-blond hair. But if her necklines got any higher they were going to choke her. She was a self-proclaimed virgin and proponent of the New Modesty and Moralism Movement.

Every office should have one.

Since Penelope had come to work at GWI three months ago, we could sense her getting more superior by the minute, filling up with smugness. Any day, she was going to burst, and purity and self-righteousness would fly all over the office.

“It’s fear,” Cleo observed. “Penelope’s just afraid. She’s sensitive. You can tell she is. She just needs to get over that hump. No pun intended.”

So it was sheer synchronicity that when I left Jake and Cleo and went down the hall to the ladies’ room to splash cold water on my face and fix my makeup in the mirror, that Penelope, Miss Virgin Islands herself, happened to burst out of one of the cubicles in that moment.

She moved with maniacally nervous energy. I couldn’t help thinking that a few orgasm-induced endorphins would have done her good.

For crying out loud.

They would have done all of us good.

She planted herself in front of the mirror next to me and fiddled with her buttons and hair and the lace at the top of her collar. Her fingers wouldn’t stay still. They skittered all over her clothes like policeman’s hands performing a search.

“Hey, Penny. Something wrong?”

She shook her head and huffed.

“So how’s it going?” Bathroom mirror etiquette requires that one must at least make an attempt at friendly chitchat with fellow colleagues. I popped the cap off my new tube of cinnamon burgundy lipstick.

Penelope’s expression was strange. She looked at me as if I were applying cyanide to my lips.

“Like this color?” I asked.

She stared at my mirror image and remained motionless.

I kept it up. “I figure you never know when some gorgeous specimen might come into the office, right?”

Her mouth became small and brittle.

I’m not a person who gives up easily. “Have to be prepared for any eventuality, I always say.”

Now you would think, with Penelope being younger than everyone else, and new to the job, that she might try to get along?

Be nice?

Speak when spoken to?

Even suck up a little?

But do you know what she said? She fixed me, one superior eyebrow still raised, and said, “You know what you are, Dinah? You’re a man-eater.”

I stared at her.

A man-eater?

A man-eater was something out of a forties movie.

An extinct animal.

And furthermore, Penelope knew nothing about me.

There was nothing to know.

Well, almost nothing.

In some ways my life was so narrow you could have shoved it through a mail slot. I was just plain old Dinah Nichols who three years ago had left her ex-fiancé, Mike, over on Vancouver Island, and exchanged her cozy and familiar little homespun angst for the big cold new angst in the city of Vancouver. I had been badly in love with Mike. Sloppily, sweetly, desperately, wetly, thrillingly, forever in love with Mike. And then I had one of those revelations about him. It came as a lightning flash from the overworked heavens. In twenty-four hours I had my bags packed and was ready to leave for Vancouver. I didn’t even give Mike the satisfaction of a fight.

During my last three years in the city, I’d been operating on a tight budget, both financially and emotionally. I had a pared-down existence of work, home, home, work, apart from my occasional clubbing forays with Cleo and my next-door neighbor, Joey Sessna. Joey was the only man in my life. I’d spotted him at one of the GWI fund-raisers a few weeks after I started working there. He was the one guest who didn’t fit the profile for that occasion (millionaire and over ninety). Joey was in his late twenties and remorselessly gay (he’s quite appetizing in the smoldering Eastern European overgrown schoolboy sort of way, with his straight dirty-blond hair, his pale blue eyes, and his pearly but crooked teeth). The day I first set eyes on him, he had snuck into the event through a side door and was shoveling hors d’oeuvres onto his plate with the kind of style and abandon you only see in starving actors. I managed to wind my way over to him before anybody else could kick him out, and by the time the fund-raiser was over, Joey had performed his entire repertoire of imitations and given me a lead on the apartment I have now.

I tried to play things up. If I wasn’t always having as much fun as I’d planned to, I at least tried to give the impression of somebody who was having more than her share of good times.

Whereas Penelope, as far as I could tell, had everything, and could have been having an authentic blast. She was fully financed by her wealthy parents, owned an Audi, credit cards, and could book airplane tickets whenever she felt like it. There were rumors of a nerdy, virginal boyfriend back East, and more rumors that he would pay a visit in the near future, no doubt to indulge in some heavy petting and assure himself that his Penelope hadn’t been accidentally ravished by one of the office Alphas.

Through my lunchroom eavesdropping I knew that Penelope, before university, had been to a Swiss finishing school and it was there that one of the worst moments of her life occurred.

Penelope confided to Lisa that in the school’s elegant dining hall, she was served rabbit on Crown Derbyshire plates. Nobody had been aware that those same rabbits had been her best friends, her furry confidantes, and that every night she’d gone down to the rabbit hutches to tell them all her woes (until they became dinner, of course).

She’d had no other friends at school. Penelope wasn’t like the other girls, that bunch of hoydens who slid down the drainpipe to hitch a ride into town to meet boys and neck and grope and have unprotected sex in the back of a car.

To hear Penelope going on about it, the Swiss finishing school had been torture to a soundtrack of cuckoo clocks. She’d watched from the sidelines as the other girls acted out their fantasies all around her, experimented with their commandment-busting sexuality, destroyed their best years through carelessness.

How tempted I was to cut in and challenge Penelope. I wanted to ask, “When in history have the teenage years ever been the best years for anybody? The teenage years suck.”

And then there was her mortification with the results of her schoolmates’ adventures. At first it was the smaller things, the broken hearts and first disillusionments, and then came the bigger things, the STDs, the pregnancies and designer drugs.

But Penelope had kept her head above water while the other girls had been drowning. She’d kept her corner of the room tidy and her virginity intact. She was able to replace her furry friends with books in other languages. They hadn’t been hard to tackle at all. Everybody in Switzerland spoke at least four languages. And she had a taste for music, poetry and literature. In the lunchroom, I’d overheard her droning on endlessly to Lisa about her favorite books, Le Grand Meaulnes for its hopelessness and romanticism, and Remembrance of Things Past for the lost world she would have preferred to this modern one.

I had the impression that Penelope was like a new-age geisha, cultivated in arts and languages and femininity, putting everything on offer except the sex.

As for me, well, perhaps I’d overdone the whole business of single girl fending for herself. Because there had been offers of help from my mother but I didn’t take them up. Our family’s wealth had been dwindling for quite a while.

I stared back at Penelope’s reflection in the mirror. Maneater. It was a silly, outdated thing to say. I had to think about it for a second. Was it a backhanded compliment? Penelope must have made a mistake. She’d mixed me up with Cleo. Fearless Cleo Jardine, who saw the entire masculine population as her own private buffet.

I said to Penelope’s reflection, “You’ve got the wrong person.”

Penelope replied, “No I haven’t. I know about you.”

“I have a Green World question for you, Penelope. How do you say home, work, work, home in Russian?”

“Dom, robotya, robotya, dom.”

“As in robot?”

“Yes.”

“Thank you, Penelope, for that depressing bit of information. Now I’m going to say this to you once, and you better believe me. My life is dom, robotya, robotya, dom.”

“I meant what I said. I know about you. You’re a man-eater.”

I didn’t know how to defend myself. I’d grown up on the edge of a boreal rain forest and been homeschooled with a small motley crew of children, the progeny of artists, scientists, and freethinkers seeking an alternative existence. Now that Penelope was standing in front of me, I regretted never having been involved in a schoolyard scrap.

How could I tell her that it had been ages since I’d devoured a man, that I’d barely nibbled on one in over a year? Sure, I was hungry enough, but since breaking up with Mike, men had been getting harder and harder to digest.

Okay, I admit I may have given her the wrong impression. Accidentally on purpose. It had been my idea to get Ida at the switchboard downstairs to give the Code Blue signal any time a hot guy entered the building. And perhaps that could seem a little predatory to the uninitiated. Or the undesperate. But every woman in the Green World International office except Penelope put their shoes back on, slabbed on the cover stick, fumigated themselves with their favorite perfume and got ready to scope when Ida gave the Code Blue.

And I confess that it had been my idea to provoke Penelope a little once we understood her position regarding the opposite sex. She had no position. Not in bed, anyway.

Maybe she was still thinking of the day I got Joey to pick me up for lunch. I stayed away for two hours, then came back to the office with a rose in my hand, a little chardonnay dabbed behind my ears, and my dress on inside out. I stood in front of Penelope’s desk for at least five minutes, so that she couldn’t possibly have missed those great seam bindings.

She’d avoided me for the rest of the day. She hadn’t understood that it was just one of our little office tests.

To see if she had a funny bone.

But the test had resulted negative.

And really, one ersatz male morsel during the lunch hour doesn’t qualify a woman as a man-eater.

Sunday

Here it was, two hours and twenty-five minutes to the official end of my thirtieth birthday and I was still brooding on Penelope’s words, wishing they were a bit true. I was still having trouble imagining me, Dinah Nichols, as a man-eater. Penelope clearly needed to get a life.

Cleo and Joey were late. We were supposed to be having a birthday drink together at my place. I’d even dusted.

Thirty was so big, so critical, so depressing now that I was minus a boyfriend, that I decided maybe it was something I would just brush off lightly.

Okay.

Deny completely.

It didn’t matter, I told myself, that my closest friends had better things to do on my birthday. I’d just stay at home, holed up by myself and meditate on my singleness.

Okay, to be fair, both of them were very busy.

The office had sent Cleo down to the Urban Waste Congress in Seattle. Joey had gone down with her to do an agent audition there and they’d be driving back together.

Joey’s film and TV roles were mostly very, very small and nonspeaking. He’d been lucky. He’d worked a lot over the last few years in sci-fi and police drama series. In the course of his career, he’d been slimed to death, machine-gunned in the street, set on fire, pushed off the side of a building, had his eyeballs drilled by Triassic creepers, had himself disintegrated into fine white talcum powder, and been sucked violently up a tube.

Ever the perfectionist, trying to improve himself in his craft, Joey often begged me to critique his performances. What can you say to a guy who has basically been fodder for extra-terrestrials? “Excellent leg work. Fantastic squirming, Joey. You really look like you’re being mashed to a pulp.”

I made some popcorn to stave off the gloom and settled back into the couch to wait for my friends. Some irrational part of me expected a sign that I’d reached that scary thirty benchmark, like an earthquake or a total eclipse of the sun. But it had been a very quiet Sunday, filled with vital activities like scouring the rough skin off my feet and giving my hair a hot oil treatment. By evening, I’d slumped onto the couch to wait for Joey’s immortal three seconds in an ancient X-Files rerun. I was going to have to resign myself to a life of solitude and strawberry mousse.

Then the phone rang.

I jumped up from the couch too fast and tripped over the plastic bowl on the floor, scattering salty buttered popcorn all over the Persian carpet. It wasn’t too late to hope. Someone had remembered after all.

Some ex-boyfriend from my past?

Or Mike—my ex-true love?

Or an ex-boyfriend-to-be from my future? Some guy I’d met at a fund-raiser then forgotten about, who might be a friend of a friend of a friend and had gone to a lot of trouble to get my number?

Or Thomas? My therapist? For all the money I was paying him, he was supposed to be making me feel better, wasn’t he? And a little birthday call would make me feel better.

And then I remembered.

The Tsadziki Pervert.

He’d been phoning me up and, in an eerie hissing voice, proposing to cover my whole body in tsadziki. You know that Greek dip made of yogurt and cucumbers? Then he was going to scoop it all up with pita bread until my skin showed through. It had to be some guy who had seen me around. Probably with Mediterranean looks and visible panty line, knowing my luck. He knew who I was because he was able to describe some of my physical features. If it was him again, this would be his third and last call.

I skidded into the hallway and found the shiny silver whistle, the kind that crazed PE teachers use. It was supposed to be dangling from a string next to the phone for any kind of Telephone Pervert Emergency that might come up, but I’d forgotten to do it. I’d made a mental note to avoid all of Vancouver’s tavernas and Greek restaurants but I’d forgotten to tie on the secret weapon. I held the whistle near my lips and got ready to pierce the Pervert’s eardrum.

I know what you’re thinking. Why didn’t I have a call-checking phone or an answering machine? And you’re right. I should have. But that would have taken such a big chunk of mystery out of my life. Not knowing who was on the other end, and anticipating something good, or something evil involving sloppy exotic foods, burned up at least fifty stress calories. And there was always that got-to-have Gap shirt to spend the money on instead.

My buttery hand grappled with the receiver. “Hello?”

“Happy birthday, Di Di.”

“Mom.” I was relieved and let down at the same time. If my own mother hadn’t called, it would have meant that things were grimmer than I thought. “I didn’t expect to hear from you. Aren’t you supposed to be out in the field up there in the Charlottes?”

“Cancelled that, poppy. Off to Alaska in a couple of days. They want me to go up and take a look at the Stellar’s sea lion situation there. Been following a project on dispersal and we’ve got quite a few rather far from natal rookeries. Shouldn’t you be celebrating with friends, Di Di?”

“I am.” I turned The X-Files up higher.

“Sound a little odd. Not on drugs, are they? By the way, a couple of things. Now…what would you like for your birthday? I think it should be something very special. Thirty. You’re on your way to becoming a mature person.”

As if I needed to be reminded.

“I’ll give it some thought, Mom.”

“Righto, Di Di. We’ll be seeing each other soon anyway. I’ll be popping in and out of Vancouver. Have several guest lectures to give up at the university. Migration of the orcinus orca is first on the schedule. They’ve organized an entire cetacea series this year. I told them I was quite happy to do the odd one as it would give me a chance to see my daughter. Oh, and another thing I keep forgetting to mention. Mike and his little wife came around several weeks ago.”

“His little WHAT?”

“Tiny limp thing, Dinah dear. Believe they’ve been married for about three months. I should think she might just blow away with the first strong wind. Don’t think she’ll be helping old Mike much with the hauling.”

“What hauling?”

“She and Mike were just about to move to Vancouver when I talked to them. I gave them your address and phone number. He seemed very eager to see you again.”

I could feel the popcorn backing up into my throat.

I liked to blame my mother for the fact that I was cruising into the end of my thirtieth birthday and flying solo. And even if it wasn’t her fault, I needed to blame my manlessness on someone. She was the logical choice.

I’d often whined to Thomas, my therapist, “How am I supposed to deal with a proper relationship? I’ve had no role models. My mother thinks that men are beasts of burden who are useful for mending your fences, mucking out your stables, feeding your seals and whales, and worshipping at your feet, but should definitely be fired if they can’t be made to heel.”

My mother is a zoologist. Marine mammals are her specialty.

And Thomas would reply, “No life is accompanied by a blueprint.”

As for a father, well, that was the main reason I was paying Thomas. There was just a terrible lonely rejected feeling where a flesh-and-blood father should have been.

Thomas was very attractive. I’d shopped around to find him. I went to him twice a month. He wasn’t your full-fledged Freudian—I couldn’t have afforded that. He was a bargain-basement therapist with just the right amount of salt-and-pepper beard and elbow patch on corduroy. He cost about as much as a meal at a decent restaurant but wasn’t nearly so fattening. His silences were filled with wisdom. And he had a real leather couch. This probably worried his girlfriend upstairs. I could picture her creeping around, but then having to give in to her suspicions and stick her ear to the central heating grates, just to be sure that nobody was pushing the therapeutic envelope down in the basement studio.

I talked and Thomas listened wisely. Then he’d pull on his pipe, expel a plume of smoke, and sprinkle his opinions, suggestions and bromides over me.

All through my childhood, I’d fantasized about this father of mine. When I was six, and asked my mother who my father was, she gazed coldly and directly at me and explained that he was out of her life, and therefore out of mine, and that I was not to ask about him again.

My mother is tall, lean, white-skinned, rosy-cheeked and blond with the beginnings of gray. She looks like a Celtic princess and is considered beautiful by almost every man she meets. I’m medium height, black-eyed, dark-haired, and on the good side of chubby. Genetically speaking, I had to wonder if that made my father a short, dark stranger.

My mother had been orphaned young, and my great-grandparents, whom I vaguely remember as a couple of gnarled, complaining, whisky-drinking bridge players, had left her a trust fund. My mother is the triumphant product of an elite private school in Victoria where she and other rich girls bashed each other’s shins with grass hockey sticks and studied harder than the rest of the city. There, she acquired her slightly English accent and a heartiness that plagued me all through my childhood. There was no ailment that chopping wood, cleaning fish or a good hike along the West Coast Trail couldn’t cure. I was fit against my will.

From the day I hit puberty, I couldn’t wait to get somewhere where the fish, feed, and manure smell didn’t linger on my clothes.

I’m convinced that if my mother had grown up without a trust fund, and had been forced to have a man support her through a pregnancy, things would have been different. I would be a well-adjusted girl with a steady permanent boyfriend. Studying marine mammals is not exactly a lucrative profession. Only somebody with an independent income could carry out the kind of field work or maintain the kind of hobby menagerie my mother had over on Vancouver Island. The animals; the seals, raccoons, hawks, dogs, cats, sheep and ponies required extra hands and lots of feed.

When I was little, I was convinced that I too was a member of the animal kingdom and that all those pets were my brothers and sisters. To get my mother’s attention, I would get down on all fours and eat out of the dog’s dish. My mother didn’t even blink. Maybe I really was just another vertebrate in all her animalia, an experiment, a scientific accident. But whenever I brought this up with Thomas, he’d tell me that I probably wasn’t seeing the whole picture. Maybe he was right. And maybe not.

I knew what I wanted for my thirtieth birthday.

At twenty-five minutes to midnight, there was a knocking at my door. When I opened up, Joey barged past me brandishing a bottle of Asti Spumante. Cleo followed, holding a bottle of chardonnay. Both of them looked as though they’d run a marathon.

I followed them both to the living room, then Joey did an about-face, said, “Glasses,” and went straight back into the kitchen to look for some.

Cleo flapped her long burgundy fingernails at me. “I know, Dinah, I know, we’re so late and you’re going to kill us.”

“I don’t turn into a pumpkin until midnight,” I said. “That gives us twenty-two minutes to get toxic and sing ‘Happy Birthday’ to me. How was the conference?”

“Shitty, Dinah.”

“Really?”

“No, literally. It was all about what we’re going to do or not going to do with the planet’s crap. Excrement. I feel like I need a bath. You know who the biggest culprits are?”

I shook my head.

“Cattle. The methane emissions from all the cow flop on this planet are going to blow us from here to kingdom come.”

“Imagine it, Dinah,” shouted Joey from the kitchen, “all the way home in the car, I get to listen to a lecture about cow farts.”

“It must have been a gas,” I said.

“Har, har,” he bellowed. I could hear him crashing around in my kitchen cupboards. “Dinah. You’ve got no glasses. Where are all your Waterford crystal wineglasses?”

“They were Wal-Mart, not Waterford and they got broken,” I said.

It was a little embarrassing.

“All of them? Should I guess? Accidentally on purpose?” asked Joey.

“Thomas said it was okay to break things as long as nobody got hurt. Mike bought them years ago and I finally got around to breaking every last one. It felt great.”

“Okey-dokey. We’ll drink out of the Nutella jars. Who wants Minnie Mouse and who wants Donald Duck? I get Dumbo.”

We poured the drinks and toasted my thirtieth.

Cleo sauntered over to my west-facing side window and gazed out. “Ooo. Your neighbor’s awake. Very, very awake.”

I panicked. “Close the curtains, Cleo. If you’re going to be a peeping Tom, try to be subtle about it.”

She whipped the curtains back across the glass and continued to spy through the crack in the middle. “God, what’s that he’s got with him? A black cat? Ooo. Hey. He’s taking off his shirt. Look at that bod. Fantastic. So toned. That man is so buff. This is better than Survivor. Take off the rest of it, honey, we’re waiting.” Cleo’s hot breath steamed up the window glass.

Joey raced over to the window and tried to elbow Cleo out of the way. “Shove over. Let me see.”

“You gu-uuys,” I protested.

Cleo’s face was flushed. “I don’t see how you can stay away from this window, Dinah? Does he always leave his blinds open? He is one hot hunk of man.”

“How would I know? He just moved in. And I try not to spend all my time glued to the window spying on my neighbors.”

It was a lie.

The new neighbor had moved in that summer. From the side window in my living room, I could look straight down into my neighbor’s ground-floor living room. His was a nineties house with floor-to-ceiling sliding doors that filled the lower north and east side of the house. A tiny L-shaped patio had been created outside the sliding doors, and beyond that, a row of bamboo had been planted to shield the windows from the street. Except that from my second-story side window, I could see everything. It was like looking into a fishbowl, perfectly situated for anonymous viewing of his living room as long as I kept the lights turned off and the curtains closed. It was an exercise in futility though because my neighbor was gay.

The neighbor’s partner would show up sporadically, sometimes for the weekend, sometimes for a couple of days during midweek, and there would be small moments, never anything overt, but a hand on a hand, an occasional woeful hug, long intense talks in the living room, wild uncontrolled laughter bubbling up, the both of them so easy with each other, so completely relaxed, that there was no doubting how well matched they were. They were perfect soul mates. I envied and admired them. From my window, their relationship appeared to have everything. Then the partner, who was small and dark in contrast to my heavier brown-haired neighbor, would disappear for a week or more, and my neighbor, obviously at a loss, would pull out his home gym and work out.

During those hot evenings in late August, I was behind that curtain watching him move his half-naked sweat-shined body. And I swear, if Russell Crowe had come along and hip-checked my neighbor out of the way, and taken his place there at the bench press, and let the last shafts of light catch the muscular ripple of his arms and torso, you wouldn’t have been able to tell the difference between the two of them.

August flowed into September and September into October and I still went to the window to catch a glimpse from time to time. My voyeurism told me that I’d been hanging on too long. How could I criticize the Tsadziki Pervert when I too was becoming an urban weirdo? I told myself that it was because I needed time before getting burned again. But now the years were beginning to speed up. I’d reached thirty without even realizing it.

“You can get your mind off his éclair, Cleo. It’s not earmarked for you. Take my word for it,” said Joey, “Dinah and I have been surveying him for a while and we are happy to inform you that he is of the religion Pas de Femme. Where information gathering is concerned, we make the CIA look like a bunch of wussies.” Joey’s expression was triumphant.

“He’s not gay,” wailed Cleo. “He can’t be, can’t be, can’t be.”

“He is, he is, he is,” said Joey, stamping his foot in imitation.

She clumped over to the table to pour herself another larger slug of wine. “The best ones. Always the best ones. And anyway, Joey, how do you know?”

Joey said, “I’ve seen him around. In the clubs.”

“Which clubs?”

“Well. I’ve seen him at Luce and Numbers and Lotus Sound Lounge. And he always has his arm around the same guy. The guy that comes over sometimes. Small, dark French-looking man with zero pecs. I’m telling you, he’s so monogamous he’s dreary.”

I took one last peep. The neighbor stood motionless now, looking out at the sky and the luminous gray clouds that threatened to burst. It was odd that we’d never met, never crossed paths. Just bad timing, I supposed. He only lived next door, but his world and mine could have been a million light years apart.

“Oh shit,” said Joey, “he’s turned the light off.”

“Probably tired of his voyeur neighbors,” I said.

Cleo had turned away from the side window to face my big front French doors. She shrieked and pointed. Outside the windowpane, hanging in midair above the little balcony, dangling from a cord, was a shadowy man.

Chapter Two

The man-shaped silhouette waved.

I ran over and opened up the French doors, then stepped out on the balcony to help the guy down.

“Simon. You’re back. Come inside before somebody calls the police.”

With expert rock-climber’s maneuvers, Simon lowered himself down to the balcony, then began to haul his cords down after himself and wind them up. He was grinning the whole time. I stepped aside to let him into the apartment, then I picked up his equipment and passed it through to him. He stood in the middle of the living room, straightened up and brushed himself off. He was dressed in black, and very lithe, thinner than when I’d last seen him, two years before.

“Hey, Di. Happy birthday. Figured I’d drop in on you. Hey, so cool to see you.”

Joey muttered, “Now that’s what I call an entrance.”

I smiled at Cleo and Joey. “This is the Simon Larkin I’m always telling you about. The one I grew up with. The one who shared my dog biscuits.”

“Yeah,” said Simon. “You could say that Di’s my honorary sister.”

Joey batted his eyelids and leapt forward to offer his hand. “Hi, great to meet you, Simon. I’m the famous actor, Joey Sessna. You may have seen me in—”

I punched Joey’s upper arm.

He yowled. “Ouch. Jeez, Dinah. Wha’d you do that for?”

“Simon doesn’t know who you are, Joey. He doesn’t watch TV. He doesn’t have to. He has real-life entertainment. When he isn’t scaling some terrifying rock face, he’s infiltrating some interesting urban landmark. Right, Simon?”

“Hey, babe. That’s me.” He grabbed me and squeezed me in one of his death lock hugs. Cleo and Joey were practically drooling. Simon was tall and toned with messy strawberry-blond curls and navy-blue eyes. He looked like a Renaissance angel in Lululemon sportswear.

Cleo grabbed my glass out of my hand, poured some wine into it, and handed it to Simon. “I’m Cleo Jardine.”

He said, “Thanks, Beauty,” and downed it in one gulp.

Joey began to jabber at Simon and I started to whisper to Cleo, “Before you get any ideas, there’s something I’ve got to tell you about Simon….” But she and Joey were so involved in ogling him that they couldn’t hear me.

“Hey Di,” said Simon, “got any growlies in the house? I’m perishing with hunger.”

I knew what was in my fridge. The Empty Fridge Diet was the most successful one I’d tried so far. We quibbled for a few minutes, then decided to call out for Chinese food when Cleo offered to pay.

When the food arrived, we all attacked it like starving refugees. But after a minute or two, I noticed Cleo and Joey making way for Simon as he helped himself two and three and four times. Simon had that effect on people.

Joey’s chatter turned into a runaway train as he tried to impress Simon with his TV and movie credits. Simon just grinned and nodded but I doubted he knew what Joey was talking about.

I said quietly to Cleo, “Simon is a bottomless pit. You don’t ever want to invite him over for dinner.”

A sly look came over her face. “I was thinking I could take him to one of those all-you-can-eat smorgasbords.”

Finally, when all the little cardboard cartons were empty, Simon rubbed his stomach and beamed angelically. “That was a nice little snack. We can get a proper meal a little later, huh, Dinah? After we’ve been out for your surprise birthday treat.”

“A proper meal? What were we stuffing into our faces just now? And a surprise? It’s after midnight, Simon. I’ve got a big day at the office tomorrow. The CEO’s coming in from the national headquarters…”

“Dinah, I’m bitterly disappointed. When was midnight ever late for you? Better face it. You’re only thirty and you’re so far over the hill you might as well just lie down and roll the last little bit of the way into your grave.” He fatefully shook his head.

I took the bait. I leapt up and began to run around, clearing up, snatching glasses out of hands and throwing away balled-up paper napkins and empty takeout boxes. “Okay, so where are we going?”

“Like I said, it’s a surprise. And I should add that I actually put some research into this.” I was very familiar with Simon’s brand of surprise. I both dreaded and longed for it.

Cleo and Joey looked at each other, then at Simon and me, and said in chorus, like two schoolchildren, “Can we come, too?”

“You don’t know what you’re getting yourselves in for. This is my whale rub friend,” I said.

“Oh my God,” said Cleo melodramatically, “not your whale rub friend? Now would that have something to do with massage?”

“Whale rub?” chirped Joey. “It sounds obscene.”

“I’ll tell you about it sometime,” I said, “when I’m really, really drunk.”

Simon nodded and chuckled. “Yeah. I’d forgotten about the whale rub.”

“Please, Simon, can we come too, wherever it is you’re taking her?” schmoozed Cleo. “I hate to be left out of the party.”

“Can we, Simon, can we?” asked Joey.

Simon moved into his inimitable and rare business mode. “I don’t know. You’re going to have to be fast. Comfortable clothes. Dark stuff. No high-heeled shoes, eh, babe?” He directed this at Cleo. “No tail ends that could hang out or get caught in or on something. We should get going, Di. We’ve got a bit of a tight and squeaky time frame here.”

I said, “What he means, is that if we don’t have the timing perfect, we’ll be like mice in a trap, squeaking our heads off. Simon doesn’t have much respect for legalities.”

“Aw, c’mon now, Di. I’ve got a most excellent lawyer. So let’s breeze on outa here,” said Simon.

Joey went back to his place to change and I lent Cleo something in black. I had a closetful. Nothing hides the fat better than black. While we were getting ready, Simon was going through my kitchen cupboards. He managed to find an old bag of sultana raisins, some chocolate chips, half a box of muesli, and a joke tin of escargot that I’d won at a New Year’s raffle. He inhaled all my remaining food supplies and announced that it was time to leave.

Simon guided us up to the roof of the Hotel Vancouver in Mission Impossible style, dodging porters and chambermaids, coaxing us through poorly-lit, forlorn hotel arteries that gave off stale and slightly greasy-smelling odors, corridors and dark places that had a vague presence of skittering creatures nearby—rats, mice, pigeons. All the way up the endless flights of stairs, he whispered, “Don’t fall behind.”

I managed to keep up with Simon. Joey, who was skinny and hyperactive, was just behind me. I sprinted along but my legs felt it around the tenth floor. Cleo, who was only interested in physical activity if there was a man dangled like a carrot at the end of her efforts, lagged about a floor behind us all, complaining that she wished she’d made her last will and testament before we’d left. We went up and up and up until we reached a door. We followed Simon out into a long musty narrow corridor lined with tiny gabled windows that looked out onto the city, a zone where chambermaids must have slept once, country girls who cried into their pillows night after night until the city was finally able to distract them.

Once he had coaxed us all out onto the roof, Simon explained. “The idea behind a good urban infiltration is to take the road less traveled, find those forgotten back routes and rooms. For example, I’ve got a friend who did an infiltration in a part of the University of Toronto. He kind of lost his way and ended up taking a tunnel to another wing that had all these more or less abandoned barrels stored there. They were full of slime. No kidding. Later he found out the barrels were used to store eyeballs. Hundreds of thousands of eyeballs. Must have been part of the ophthalmology department. That’s the fun of it. Discovering things. He said it was a pretty freaky place. Could have been a hiding place for all kinds of crazies.”

We were seated precariously on the green copper roofing looking out over the myriad of city lights under the cloudy night sky. The gray stone of the hotel plunged downward just a few feet from where we sat. We could see between the glass high-rises to the North Shore and Grouse Mountain high up in the distance. Beyond the dense bright core of downtown in the other direction I could see the Burrard and Granville Bridges, the beads of car lights in constant motion.

Simon opened his small backpack and pulled out a bottle of Brut. “For you, Di. Happy birthday, eh?”

“Jeez, Simon, if somebody had told me that I was going to toast my thirtieth birthday on the rooftop of the Hotel Vancouver, quite a different picture would have come to mind.”

“It’s exciting,” shivered Cleo, paler and stiller than usual.

Joey nodded in agreement, looking no less terrified.

Simon could have been telling Cleo and Joey that the earth was flat and the moon was made of blue cheese and they would have had the same expressions on their faces. Simon was so decorative, so distractingly gorgeous. I should have, I really should have told them what else he was. And wasn’t.

“Fascinating,” oozed Cleo.

“Absolutely,” agreed Joey.

“Now I have something to say,” I announced.

“Here, here,” said Cleo.

“I have to inform you all that Penelope Longhurst…”

“Oh God, here we go,” said Cleo.

“Penelope Longhurst has decided that I, Dinah Nichols, am a man-eater.”

“A what?” squealed Cleo.

“How quaint,” said Joey.

“You been up to tricks while I been away, Di?” asked Simon. He laughed, took the Brut bottle back, popped its cork, took a swig and handed it back to me.

“Not enough tricks,” I said.

“Now let me see,” said Cleo. “There are the Joan Crawford, Lana Turner, Sharon Stone, Madonna, Hollywood kinds of man-eaters. Then there are the literary kinds—the Iris Murdochs and the Sylvia Plaths who eat men like air.”

Joey said, “Actually, the image that comes to my mind is more basic—a jungle animal, a lioness ravaging some poor male.”

“If only I had it in me, Joey. I hate to say it, but that Penelope’s starting to piss me off big-time,” I said.

“We’re pretty sure she was sexually traumatized at some point in her young life when she was at Swiss finishing school,” said Cleo.

I muttered, “I wish somebody would sexually traumatize me. It’s been nearly three years if you don’t count that one stupid little mistake with Mike. Here’s my point; if the shoe doesn’t fit, cram your foot in a little harder until it does. Here’s to me, Dinah Nichols, man-eater.” I raised the bottle and drank.

Monday

I felt as though I had a hamster wheel in my head. And worse, the hamster was hungover. I made a list of all the no-brainers I could do that day to make myself look busier than I was. Penelope wafted past my open door with her The-Intact-Hymen-Shall-Inherit-the-Earth look on her face. Jake was right behind her and when I caught his eye, he pointed at her and mimed eating something. Yipeee. He was sending her on her way to do gopher errands.

I felt a bit better and was just contemplating how to continue avoiding any real work when the office intercom suddenly erupted with Ida’s voice at top volume. “CODE BLUE, and I mean REALLY REALLY BLUE.” I raced out of my office and into the main room.

What was left of breathable air was bombarded with fragrant powders and atomized scents. A frenzy of beautifying shook the office. Jake came out of his office, too, and looked on, shaking his head.

Ida’s voice came over the intercom again. “Code Blue about to advance.”

We all raced over to the window. On the street below, a black Ferrari with beige leather upholstery was inviting the local grunge merchants to either take it for a joy ride or just leave it where it was and vandalize it. But a second later, a svelte figure in a dark-gray glam Goth suit stepped out on the sidewalk.

Ida’s voice broke in again. “Code Blue looking better than my dreams.”

He had a full head of messy black hair with a hint of silver that stayed perfectly in place even though huge gusts of wind were making litter roil up the street. He gazed up at the facade of the GWI building. We all leapt back out of his view, except for Lisa Karlovsky, our big blond volunteer coordinator, who smiled and waved down at him. Then she turned her head upward and laughed. “Guess who else is hanging out the window upstairs?”

“Not Ash?” said Cleo.

We all shoved and jostled and pushed ourselves out through the window frame to get a look at Ash looking at Ian Trutch. She was leaning out above us, her glasses dangling from her hand, her dark eyes wide.

“That,” said Lisa, “is the first time I have ever seen her without those bottle bottoms covering her face.”

“We should hold a press conference,” said Cleo.

Ash, otherwise known as Aishwarya Patel, was our entire accounting department. Thin and sallow, of undetermined age and wearing a dull black frump suit intended to be a power suit, Ash seemed to think she was the most important person in our organization because the donation money was processed by her. She was allergic to the human race and ate her daily lunch of sour grapes at her desk in her office. Her door was always closed. All communication from Ash came through e-mail directives, usually capital letters, which came across like cyber-screaming. Even though her office was upstairs, right next to the lunchroom, where all of us made at least ten stops a day at the fridge full of goodies, Ash found it too socially challenging to get up and walk those few feet into the lunchroom to tell us anything in person, to give us, for example, her last earth-shaking directive, TO ALL OFFICE STAFF: DO NOT STIR COFFEE THEN PUT WET SPOON BACK IN SUGAR BOWL. LUMPS FORM.

And I heard that Jake, in a rare moment of unprofessionalism, sent an e-mail back to Ash, “Well, hey, Ash, sweetheart, that’s life. LUMPS FORM.”

Ian Trutch frowned up at all of us, then walked toward the main entrance.

Ida’s voice burst in. “Code Blue advancing. Code Blue advancing…oh baby…”

We all pulled ourselves back into the room.

“So that’s the big mucky-muck, eh? The new CEO. Like them apples,” said Lisa.

“It’s him,” said Cleo. “And thank goodness for that. Can’t have a morning’s makeup wasted.”

Fran, the secretary, said, “He’s had work. I’d put money on it.” Since her husband had dumped her and her three children for Silicon Chick, Fran had been wearing her forty-nine years, crow’s feet, double chin, limp gray hair and extra hip-padding with pride. Her favorite game these days was Spot The Cosmetic Surgery. “He’s a careful piece of work, I’ll bet. Expensive work.”

“Fran.” Cleo laughed. “He’s only in his thirties. Why would he need work?”

“Wake up, sister. This is the Age of Perfection. And perfection can be bought,” she snorted. “But I just want to add the footnote that I’d let this one warm my bed on a cold night, nose job and all, just as long as he’s out of it by morning.”

I was reserving judgment. I got myself a cup of coffee and went back into my office to think about what I’d just seen. Ian Trutch was everything we were not. He was trouble in a fancy package. And it was going to be very bad for our image to have a CEO who whizzed around town in a black Ferrari. But then the frisson of nervousness kicked in and for the next few minutes I fantasized about meeting the enemy halfway and riding around in a fast car with an even faster man. Something I’d never done.

The ringing phone interrupted my reverie. I picked it up and said, “Dinah Nichols.”

The voice on the other end was incoherent. It took me a minute to realize it was Joey. He was crying and stuttering.

I said, “Joey, Joey, calm down. I can’t understand a word you’re saying.”

All I could make out was “hoia…coy…hoia…glop…oodle” between the gasps and the tears.

I tried again. “What’s happened? Get a grip on yourself.”

“It’s too horrible….” sobbed Joey.

“Just take a few deep breaths then tell me slowly.”

There was a wet silence and then he started. “You know I walk dogs for Mrs. Pritchard-Wallace out near Point Grey?”

“Yeah?”

One of Joey’s filler jobs.

“Not anymore.”

“What happened?” I asked.

“Well, early this morning I was taking Jules and Pompadour, Mrs. PW’s miniature poodles, for a walk along by the golf course, when this thing, this creature from Hell comes streaking out of nowhere, snatches Pompadour in its jaws then streaks away. Nothing left but Pompy’s diamond collar. It was a wolf. I’m sure it was a wolf.”

“It was probably a coyote.”

“You’re kidding me, Dinah.”

“Was it sort of a yellowish color?”

“Yes, my God, it was. How did you know?”

“Don’t you read the news?”

“Variety. I read Variety. You know that. I haven’t got time for global disaster.”

“Jeez, Joey. They figure there must be at least two thousand coyotes in and around town. They can’t catch them because they’re just too smart. I’d heard about them, I’d just never had a firsthand account. Wow.”

“Wow is right. Mrs. PW’s going to have hysterics. She doesn’t know yet. She’s out getting her facade renovated.”

“Her what?”

“Getting her face stripped and varnished. A peeling and a facial, darling.”

“Oh.”

“And I’m shaking all over. I’m going to have a Scotch right now.”

“Joey. At nine forty-five in the morning?”

“It’s not every day somebody’s thousand-dollar poochie gets to be part of the urban wildlife food chain.”

“God, yeah. Listen, Joey, you don’t want to get the coyotes used to a diet of expensive house pets. It might build their expectations. You know? Like potato chips? Once you’ve had one, you just can’t stop. So don’t encourage them…careful where you walk your dogs. Listen, speaking of predators and prey, the big boss from the East just blew in driving a Ferrari and I’m really worried, I’ve heard he’s completely insensitive to people’s feelings. He decimated the last office he was in and then some. And I’m told that there may be a total massacre in this office, too…”

It would have been better if I hadn’t looked up at all.

“Ooops…gotta go.” I slammed down the phone.

He, Mr. Silent Shoe Soles, was standing in my open doorway, staring at me. The CEO. He was so luscious-looking in real life that I could hardly swallow.

Chapter Three

Ian Trutch continued to stare at me. I tried to match his stare but I couldn’t stop myself from taking inventory. My eyes went first to his face and then to the mahogany skin and black chest hair at the neck of his unbuttoned white shirt. I swallowed with difficulty. If I’d been another kind of girl, if I’d been Cleo, for example, I would have been tempted to climb down inside that crisp shirt and stay there. Maybe all day. Definitely all night. Little things, the length of his fingers, the way his cuffs circled his wrists, made me shiver.

He had eyes the color of swimming pool tile, surrounded by long, black, almost feminine lashes, and a little set of deep thinker creases between his eyebrows, reflecting his Harvard Business School prowess. His thick, silver-black, stylishly electro-shocked hair was just waiting for some girl’s hands to give it a good running through, though I suspected he was the type who didn’t like having his hair messed up. Everything else about him was immaculate. He had a knowing, ever-so-slightly cruel mouth and a pirate’s tan.

Sailing, sailing, sailing the bounding main…

It was a good thing I knew where the boundaries lay and wasn’t the sort of girl who fell for that whole superficial gorgeous man thing. If I had been a real man-eater like Cleo, I would have considered pursuing him for his body alone. Like wanting a whole bottle of Grand Marnier for yourself, it would be a sweet, intoxicating blast, but ultimately bad for you.

I stopped staring at him. He definitely clashed with the office décor, the splodgy lemon custard walls, the burnt caramel Naugahyde furniture, the mangy, pockmarked beige wall-to-wall carpet. The big question kept nagging at me. Why was a glossy high-rise type like Ian Trutch playing CEO to a low-rise walk-up organization like ours?

Jake appeared behind him. “Dinah, this is Ian Trutch. Ian, this is Dinah Nichols, our PR and communications associate.”

He reached out his hand then clasped mine in both of his. They were warm and smooth. “Dinah. Very, very nice to meet you. I’ve heard a lot of good things about you.”

I swallowed. “You have?”

“You’re the girl who goes after the donors. Jake’s been telling me about you.”

“He has?”

Ian Trutch still had my hand prisoner. I knew I shouldn’t fraternize with the enemy in any way, but when he let go of it, my whole body screamed indignantly, “More, more.”

He added, “Join us, won’t you, Dinah? I’m just going to have a few words with the staff in the other room,” and then he touched my shoulder. I stood up and like a zombie, followed the two men out into the main room.

As soon as Penelope saw Ian Trutch, she bounced to her feet and went up to him. “Welcome to our branch, Mr. Trutch. Can I get you a coffee?”

Ian Trutch’s face became delectable again. He said, “Yes, thank you…and you are?”

“Penelope.”

“Penelope. A classical name for a classical beauty. Don’t wait too long for your Ulysses. I take my coffee black and steaming.”

Every woman in the room was staring, breathless, vacillating between envy and lust.

“Sit down, Mr. Trutch. I’ll bring it to you,” said Penelope.

But Mr. Trutch didn’t sit down. His tone became snappy. “There’s going to be a meeting in the boardroom upstairs in exactly thirteen minutes. Ten o’clock sharp. Everyone should be present.” He took one sip of the coffee Penelope had brought him, put down the mug and walked toward the back door. On his way out, he winked at me and said so softly that only I could hear, “Get ready for the massacre, Dinah.”

A little laugh escaped me.

He’d recognized me for who I was.

The worthy adversary.

I was looking forward to the battle, to showing him that our branch of Green World International was a great team. Excluding Penelope, of course.

Jake looked slightly ill. He turned away and headed back into his office. I followed him in. He sat down heavily then looked up at me with his tired bloodhound eyes. His hand was already dipping into his bottom desk drawer. I had a microsecond of panic that he might have a bottle hidden in there but he pulled out a Bounty Bar, ripped it open, and finished it in two bites. Then, ignoring the little chocolate blob dangling from his moustache, he tore open an Oh Henry! and gestured to the drawer as if to say, “Help yourself.”

“No thanks, Jake. I’ll just sniff the wrappers. I’m counting calories.” I was always counting calories. Four thousand, five thousand, six thousand…

He didn’t come out and say, “Ian Trutch doesn’t belong here,” but I knew he wanted to.

“Jeeee-susss,” sighed Jake, shaking his head. “I’m not sure I’m ready for this. I’ve got kind of a creepy feeling. A few years ago a feeling like this would have had me out of here and heading for the pub.”

I couldn’t stand to see Jake depressed. “Well, let’s think positively about this.”

He gave a sad little chuckle. “Ah…yeah, sure, Dinah. That would be the world’s greatest female cynic talking to the world’s greatest male cynic.”

“Well…there are some donors out there who respond better to the kind of image that Ian Trutch has. Maybe a little polish could attract more of the kind of donors we’re always trying to attract.”

“Polish, Dinah? I don’t know. I guess…”

I could see how troubled Jake was by all of it, by the suit that followed the lines of the perfect body perfectly, the chunky gold Rolex watch and sapphire signet ring, the aftershave that smelled like a leathery, wood-paneled library in an exclusive men’s club.

I’d spent most of my dating life with Mike, who was gorgeous in a subtle downscale kind of way. But Mike was a man who had, maximum, three changes of clothes, the highlight of which were artfully faded jeans and a pair of expensive but battered Nikes. Formal for Mike was a clean T-shirt.

It was the first time I’d ever been monitored and streamlined by such chic management. When I stepped back out into the main part of the office, I realized that it was a first for all the other women, too. The female energy was radioactive, buzzing out of control. The other women in the office were primed, and when ten o’clock rolled around and we trooped up to the boardroom, they were all ready to convert to his religion, whatever it might be.

Ian Trutch strode into the room, stood at the end of the long table, looking around him as though he were checking out all the emergency exits, then he nailed each and every one of us with those blue eyes and said, “First of all, I know how you’re feeling and I just want to reassure you all that my presence here does not represent what you think it represents.”

The tense expressions relaxed only slightly.

“I don’t know what you’ve heard from the main branch, but I want it to be understood immediately that this branch and the main branch represent two situations and methodologies that are in no way analogous. Main branch is the administrative headquarters so it follows that it was getting top-heavy with administrative personnel.”

Top-heavy? According to Moira’s version, it was the little guys who’d been axed back East. The people who did the legwork. The people like us.

“I’ve been told that this branch is known for its team-work.” He smiled. “But it needs to be stated that the individual player, for the sake of the team, will be rewarded for any private initiative taken in terms of information exchange. In the weeks that I’ll be monitoring this office, I’ll expect the maximum effort from everyone. It goes without saying that if there is deadwood here, then it will have to go. It’s also possible that there will be no redundancies. I want it to be known that there will be no unnecessary suffering. So let me just finish by saying that I am looking forward to a fruitful collaboration.” He smiled radiantly.

There was an audible group gulp. We weren’t sure whether we were praiseworthy or being judged guilty before the crime had even been committed.

And then he launched into his strategy. It was all in code of course, full of very businessy-sounding words that had little to do with the way Green World International operated. Best practices, upstream, downstream, outsourcing. Somewhere around the word input I looked sideways at Cleo. She had obviously fallen into a fantasy involving Ian Trutch and a round of input, output, input, output…

Lisa Karlovsky was sitting on the other side of me. She elbowed me and scribbled on a pad, “You following this?”

I scribbled back, “Sort of. Don’t trust him.”

She scribbled, “Don’t care. Waiting for him to smile again. Catch those nice dimples.”

Cleo, who was on the other side of me, grabbed Lisa’s pad and wrote, “Like to see all dimples. Not just head office dimples but branch office dimples too.”

For the rest of the meeting, I watched Lisa and Cleo watching him. The women were all working hard to understand as much as possible of Ian’s talk, but also to keep a euphoric expression off their faces, their jaws from relaxing. Except for Penelope, the little priss. She was taking notes briskly.

When Ian had finally finished, Jake stood up and went over to corner him in private. Cleo, Lisa and I huddled together.

Lisa whispered to us, “So. What was it we were supposed to understand from all that razzmatazz business-speak?”

“Sorry, I drifted. I didn’t follow it. He’s so amazing to look at, to breathe in,” said Cleo.

“I’m not sure,” I offered. “It sounds good at first, like we’re all supposed to be working together, but then you realize that what he’s really saying is that we’re all supposed to be spying on each other to see who the biggest slack-ass around here is and then go running to tell him about it.”

Lisa said, “I totally lost track. I was imagining what he’d be like naked and horizontal.”

“Don’t do it to yourself, Lisa,” I said. “He’s a complete vampire and will suck up all your goodness. I know because I called up Moira in the East and got a bit of dirt. Four empty desks, she said. No higher management. Just little guys. She couldn’t talk but I’m going to call her back and get more on him. We need to know the enemy.”

Lisa looked woeful. “But main branch is much bigger, Dinah. He just said it himself. It’s a whole different thing.”

“I’m immune to his charms. If I have to go down, I’m going down kicking.”

Cleo smiled. “You take men too seriously, Dinah.”

Lisa nodded.

I shook my head. “He belongs to a win-lose world. You either have to be beneath him, or above him, and if you are above him, he’ll take you down. I know the type. The animal kingdom is full of them. There is no win-win here.”

But Cleo was not discouraged. She eyed him hungrily. If she continued at the rate she’d been going, her sexual odometer would soon be into the triple digits. She was a woman who was used to taking men at face value, but taking them.

“We’re not the only ones lusting around here,” said Lisa, nodding toward Ash.

We all looked over at Ash who was watching Ian. She had a soft glazed-over look, never seen before that day.

I said, “She’s got him where she wants him all week. He’s going to be in her office going over the books.”

Cleo said. “She’s going to have human contact? Somebody’s actually going to talk to her face-to-face? It’ll give her a nervous breakdown to have to look him in the eye.”

After work that day, Jake, Ida, Lisa, Cleo and I got together at our usual, Notte’s Bon Ton, a pastry and coffee shop on Broadway, just a few blocks from our office, to save the world.

“Energy crisis? What we do is we exploit people power,” said Lisa. “Harness the energy of all those people who go to the gym to pump and cycle off all the fat the planet has labored so hard to supply to their necks and waistlines. We hook ’em up to generators. We don’t tell ’em, though. So they’re giving back some of the energy they stole from the grasslands when wheat was planted and the flour was ground up and baked into the donuts that they are right now stuffing into their mouths, right? Very cost efficient.” She punctuated this by sticking a cream-filled pastry into her mouth and wiping it broadly.

“Sure, Lisa,” I said.

“We go back to the horse and buggy,” said Jake. “Best natural fertilizer in the world, horse poop. And you drink one too many, your horse knows the way home.”

“Windmills,” I said. “The old-fashioned Dutch kind. They could do something arty with the sails, paint them. Stick them out in Delta. People could live in them. Wouldn’t that be cool?”

“Trampoline generated power,” said Jake. “Kids love trampolines. You harness that bounce, you could light up the whole city. Or that thing they do when you’re trying to drive across the country and they kick the back of your seat for thousands of miles. Man, if we could harness that…”

I shook my head. “We can’t do that one, Jake, exploitation of minors.”

“I’m just glad I won’t be around when the big food shortage hits,” said Ida. “And if I am, I’ll be too tough and stringy for anybody’s tastes.”

“Ida,” gasped Lisa, “you’re not suggesting cannibalism, are you?”

Ida pontificated. “I figure it like this. With the agricultural society going at it with all those nitrogen fertilizers, it’s going to be hard to return to being hunter/gatherers. What’s going to be left for us to gather or to hunt? You can’t even be a decent vegetarian anymore. I figure a nice roast brisket of fat arms dealer is a good place to start.”

“Here, here,” everybody agreed.

Cleo said, “Okay now, forget saving the world. I’ve got a headline.”

Now that we’d all given up pretending we didn’t fritter time away surfing the Net during working hours, we called our surfing Headline Research. At the end of the day we’d throw them at each other and play True or False. Losers paid for the pastries.

Cleo started with, “Delays In Sex Education, Education Workers Request Training.”

Jake’s was “Girl Guide Helps Snake Bite Victim In Kootneys.”

Ida gave us, “President Urges Dying Soldiers To Do It For Their Country.”

Lisa’s was “Cougar Terrorizes Burnaby Dress Shop, Trashes Autumn Line.”

I finished off the round with, “Scientists Say Oceans’ Fish Depleted By Ninety-Five Percent.”

Everyone turned on me, protesting.

Cleo said, “Ah, Dinah, there you go again. You’re being an awful bore. I know you’re an eco-depressive but couldn’t you just play it close to your chest for once.”

Lisa said, “Don’t focus on those negative things, Dinah, or you’ll draw them to you like a magnet. Life isn’t as bad as you think it is. Your glass could be half-full if you wanted it to be.”

I thought this was good coming from a woman who had been used all her life by professional navel-gazers and full-time fresh air inspectors she called “lovers.”

Ida sat back and contemplated her rum baba then said, “Be as negative as you like, Dinah, because by the time they really heat this planet up I’ll either be six feet under or too gaga to care.”

“Idaaa…” said Jake.

“There are worse things,” said Ida.

I held up my hands. “I come by it honestly, guys. I have an illustriously cynical mother. Now you all have to vote. Which is the fake?” I asked.

“Cougar,” said Cleo.

“I agree. Cougar,” said Ida.

“Girl Guide. Jake, you’re a fake,” said Lisa. “It’s an old joke, that one.”

“You nailed me, Lisa,” said Jake, his hands in the air.

“News for all you fish eaters, and that means you, too, Cleo,” I said. “The ocean’s fish stocks are only depleted by ninety percent and most of what you get these days is fish farm stuff. You should know that. That’s the other fake.”

“Oh friggin’ great. Big consolation. But you and I win, Dinah,” said Lisa, “which means the rest of you guys are paying for our cream puffs. The cougar headline was in the Sun this morning. I’m surprised you guys missed it. He’s been roaming around Vancouver and they just can’t seem to catch him.”

“We’re getting these cougar sightings around here from time to time,” said Jake, “but it’s been a while now. Then there’s the coyote situation. Damned forestry practices. They cut down the damned forests, these big cats lose their damned habitat, have no damned place to go, so what does anybody expect? They come into town on the log booms, stir up trouble.”

“If I didn’t know better I’d say you were making it up,” said Cleo.

“No way,” said Lisa, “and these are not happy animals. They’re feeling pretty crazy mad by the time they hit town. Look behind you when you’re walking down the street.”

“I knew about the coyotes. But cougars,” said Cleo. “Who would have thought it?”

I said, “The only wildlife you’ve had your eye trained on lately, Cleo, is homo sapiens, the male of the species.”

“True, true.” She smiled.

“There hasn’t been a cougar sighting since you’ve been here. Not in the last two years,” I said.

“There’s a whole variety of urban critters out there, believe me, Cleo. Our building was skunked last week,” said Lisa. “Little stripey guy got into the basement bin under the garbage chute. Quite the distinctive odor is skunk.”

“And speaking of distinctive odors,” said Ida. “How come the new CEO, Mr. Ferrari, isn’t here stuffing his face with butter cream bons bons like the rest of us? Boy, does he smell good.”

Jake polished his bald spot nervously and gave his mustache a little good luck tug. “Time management thing.”

“Yeah. The management ain’t got no time for us, eh?” joked Lisa.

“And what about the new girl?” Ida went on. “What’s her name again?”

“Penelope,” said Jake, perking up.

“How come she isn’t here either?” asked Ida.

Cleo said, “You have to make a choice, Ida. It’s Penelope or Dinah. The office virgin has taken a disliking to poor Di.”

“I thought Ash was the office virgin,” piped up Ida.

“We don’t really know anything about Ash,” said Cleo, grinning and wiggling her eyebrows.

“Just to change the subject slightly, I wonder how Ian Trutch is going to go down with our Indian volunteers?” Lisa pondered.

“Lisa!” We all pounced. “You can’t say that. It’s so politically incorrect.”

“Oh jeez, you guys. Dots not feathers.”

We all sat back. “Oh…okay then.”

Dinah Nichols the eco-depressive. It was another one of the reasons I was seeing Thomas. And again, I liked to blame my mother for forcing me to absorb a lifetime of scientific data that promises nothing good.

At night when I closed my eyes, the vision came to me on schedule. I could see the whole planet from a distance, the way the astronauts must have first seen it. But I saw it with an eagle’s eye, first hovering way off, out in infinity, and then honing in and zooming to all the trouble spots. The Chernobyls, the devastated rain forests, El Nino, the quakes and mudslides, the beached whales, the factories everywhere pumping and flushing out their toxins, cars, a gazillion cars studding the planet, and a brown sludge forming around the big blue ball like a sinister new stratosphere. It was only headline overload, but sometimes it got me down so low, it was hard to get out of bed.

Tuesday

By 8:00 a.m., I had learned that Ian Trutch was damaging our grassroots image even further by staying in a plush suite on the Gold Floor of the Hotel Vancouver. After a brilliant example of minor urban infiltration, I also found out very brusquely that nonguest people like me weren’t allowed to wander its corridors, not even with the lame excuse of having to deliver business-related papers. No siree.

When I got back out to the street after the nasty run-in with the Gold Floor receptionist, there was a parking ticket shoved under the windshield wiper of my battered red antique Mini. I swear, even to this day, that they moved that fire hydrant next to the car while I was inside.

I drove fast back to Broadway and the Green World International office. I was twenty minutes late for work because I had to play musical parking spaces for half an hour and then run ten blocks to the office. Of course, Ian Trutch was there to see me arrive late and all sweaty and flustered. He gave me an inquisitive blue stare and tiny smile, then went off to monitor somebody else.

I went into my office and shut the door. It was opened again immediately by Lisa, who pretended to have important business with me but was really just hiding from one of the needy cases. Every so often, some loafer would shuffle in off the street and say, “Hey, man, I’m a charitable cause, you guys do stuff for charities, so waddya gonna do for me?” And Lisa, being Miss High Serotonin Levels, and “good with people,” had been elected to handle them.

Lisa eyed my collection of office toys then picked up my Gumby doll and tied his legs in a knot. I looked up at her. With her blond hair in braids, her lack of makeup, and loose pastel Indian cottons over woolen sweaters, she looked as though she’d stepped through a time warp directly from Haight-Ashbury, from a gathering of thirtysomething flower children.

I said, “Another passenger from Dreck Central, eh, Lisa?”

“Shhh. It’s that bushy guy again. His name’s Roly. You know the nutty one with the long gray hair and beard who always wears the full rain gear right down to the Sou’wester? He keeps coming around and asking for me. I guess I shouldn’t have been so nice to him.”

“Lisa. You don’t know how not to be nice.”