Rising Tides

Emilie Richards

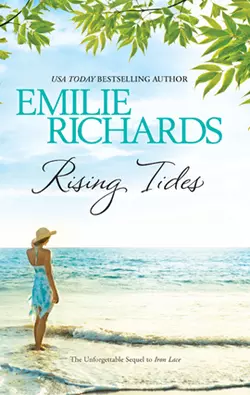

Nine people have gathered for the reading of Aurore Gerritsen's will. Some are family, others are strangers. But all will have their futures changed forever when a lifetime of secrets is finally revealed.Aurore Gerritsen left clear instructions: her will is to be read over a four-day period at her summer cottage on a small Louisiana island. Those who don't stay will forfeit their inheritance. With the vast fortune of Gulf Coast Shipping at stake, no one will take that risk.Tensions rise as Aurore's lawyer dispenses small bequests, each designed to expose the matriarch's well-kept secrets. Longtime loyalties are jeopardized and shocking new alliances are formed as the family feels the sands of belief shifting beneath their feet. As a hurricane approaches and survival itself is threatened, the fourth day dawns and everyone waits for the final truth to be revealed.

Rising Tides

EMILIE RICHARDS

Rising Tides

For Maureen Moran, with thanks for her support.

Dear Reader,

I was delighted to learn that Iron Lace and the sequel, Rising Tides, would be re-released in trade paperback this year. The novels were originally published more than a decade ago, and since that time I’ve had many letters asking where they could be purchased. I’m happy to say these new editions will appeal to readers who didn’t find them the first time, as well as readers who did, but would like new copies to replenish their libraries.

Iron Lace and Rising Tides were written before Hurricane Katrina destroyed so much of the Crescent City, including the house where I lived when I was researching the stories. The two novels are set between historic hurricanes, an unnamed one at the end of the nineteenth century, and Hurricane Betsy in 1965. The research was thought provoking. It was also preparation for what was to come, although I was no longer living there to watch Katrina up close. Like the rest of the country, I grieved, but unlike many I was not surprised.

Louisiana is a unique state with a unique identity. I like to think of these books as literary gumbo, exploring the myriad of people, cultures and attitudes that have made it what it is. Once you’ve lived there, no matter where you go, a part of you will always call Louisiana home.

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

EPILOGUE

LETTER TO READER

PROLOGUE

New Orleans, 1965

Dried rose petals, vetiver and death. The three scents pooled in the sultry May air until there was no escape from them. After her first waking breath, Aurore was frightened to take another. More disturbing still was the knowledge that, once again, she had dreamed of Rafe.

As always, he had come to her when she least expected him. Others sometimes came, apparitions who stalked her dreams and the lucid moments when she dared to count the days left to her. But it was only Rafe who came when she was sleeping soundly, Rafe who gathered the events of her life like wildflowers in a summer meadow and presented them back to her.

She forced herself to breathe, but as she did, the air seemed to grow more oppressive. She had forbidden her household staff to turn on the air-conditioning in this wing of the house, and the ceiling fans whirring above her mixed warm air with warmer. Someone had closed her windows as she napped, afraid, she supposed, that she would awaken if a mockingbird shrieked a crow’s call from the branch of a magnolia. Her staff didn’t understand that each waking moment was a lagniappe, an unexpected gift appreciated only by the old.

She was old. She had denied the truth for years, convinced at sixty that activity was an antidote for aging, convinced at seventy that she could ignore death as she had sometimes ignored the other unpleasant realities of life. Now she was seventy-seven, and death wasn’t going to ignore her. Death had loomed beside her bed for weeks, ready to pounce if her will faltered. Had there been one such moment, she knew, she would be gone already, and she hadn’t been ready to die. Not then. Not with stories waiting to be told, secrets waiting to be revealed.

She had almost waited too long. Years ago she could have called her family together, summoned them like an imperious matriarch and forced them to listen to an old woman’s tales. They wouldn’t have dared disobey her summons.

But she had waited. Now, with death waiting to claim her, she knew she could wait no longer. She opened her eyes and saw that the room was growing dark. Twilight had always seemed like God’s indrawn breath, a pause in the progression of time. But there was no time to pause now. Never again.

Something rustled at her bedside, the unmistakable crackle of a starched white uniform. She turned her head and saw that the woman standing there was the gentlest of the nurse-companions who charted the ebb tide of her life. Aurore struggled to form words. “Has Spencer arrived?”

“Yes, Mrs. Gerritsen.”

To Aurore, her own voice seemed a profane rasp in the stillness, but she was pleased it was audible. “How long?”

“He’s been here nearly an hour. I told him you’d want me to wake you, but he wouldn’t let me.”

“He protects me.” She moistened her lips with her tongue. “He always has.”

“Would you like some water?”

Aurore nodded. She could feel the head of the bed lifting as the young woman cranked. “Just a sip. Then…Spencer.”

“Are you sure you feel well enough?”

“If I waited until I felt better…I’d never see him.”

The nurse made sympathetic noises low in her throat as she poured water from a pitcher, then lifted a glass to Aurore’s lips. The water trickled in, drop by drop, until Aurore signaled that she was finished.

“Do you want anything else before I get Mr. St. Amant?”

“The windows. I don’t want them…closed again. Never again.”

“I’ll open the French doors, too.”

Aurore listened as the rustle circled her bed. She heard the slide of windows, and then, from outside, the chirping hum of the year’s first cicadas. The air that drifted in was damp against her skin, primeval in its rain-forest scent and sensation. For a moment she was seventeen, standing on the bank of the Mississippi River, and river mist was rising to envelop her. She was leaning forward, watching barge and steamer make their way against the current. She was leaning forward, waiting for life to begin.

“Aurore…”

Aurore turned her head and gazed at the man who had been her attorney for nearly fifty years.

“How are you, dear?” Spencer asked.

“Old. Sorry I am.”

Spencer slowly lowered himself to the chair the nurse had placed at the bedside. “Are you really sorry? I re member when you were young, you know.”

“You remember too much.”

“Sometimes I think so.” He took her hand. His was dry and trembling, yet still strong enough to enfold hers.

Her mind drifted again, as it sometimes did now. She remembered a day so many years before, at Spencer’s office on Canal Street. The office was still there, despite Spencer’s being well past the age of retirement. She didn’t know why he hadn’t passed on his practice to one of his younger partners, but she was glad, so glad, he hadn’t.

“You were elegant,” she said. “Compassionate. I still thought…you would turn me away.”

“The first day you came to see me?” He laughed a little. “You were so pale, and you wore a hat that cast a shadow across your forehead. I thought you were lovely.”

“But…you couldn’t have liked what you heard.”

“It wasn’t my place to like or not like what you told me. I promised you I would never betray a word of what passed between us. You played with a long strand of amber and jet beads while we talked.”

“Amber and jet.” She smiled. “I don’t remember.”

“The beads passed between your fingers, one by one, like a rosary. There was time for a hundred pleas for intercession before you left my office.”

She lifted her gaze to his. “I’ve learned since that no one…will intercede for me.”

His hand tightened around hers. “Then you’ve learned more than most people ever do, my dear.”

“I want you to file the new will. Just as we wrote it. I want…the old will destroyed.”

Seconds passed by. “You’ve thought this over care fully?”

“It is all…I’ve thought about.”

“Things may not turn out as you wish. More harm than good could result. At the very least, people you love could be hurt.”

“My whole life…I’ve been afraid to tell the truth.”

“And you’re not afraid now?”

“I’m more afraid.” He sat forward, cradling her hand in his lap, but she continued before he could speak. “But even more afraid…the truth will never be told. Others must have the chance to be courageous now…as I never was.”

“This is an act of courage.”

Her mind drifted to two men she had loved. Rafe. And her son, Hugh. Two men who had known what courage was. “No. Not an act of courage,” she said. “The last, desperate act of a coward.”

Twilight deepened into night as they sat together. Finally he spoke again. “Shall I come back tomorrow to see if you’ve changed your mind?”

“No. Will you do this for me, Spencer? Just as we talked about? You’ll go down…to Grand Isle?”

“I’ll do whatever you wish.” He paused. “I always have.”

“No one ever had a better friend.”

“Yes. We’ve been friends.” He lifted her hand to his lips and kissed it. Then, gently, he placed it at her side. “I have an address for Dawn. She’s in England, taking photographs for a magazine in New York. I could ask her to come home.”

For a moment, Aurore was tempted to say yes. Just to see Dawn, to have her beside her bed, to touch her one last time. Then to be forced to reveal everything to her granddaughter, much as Dawn had once revealed childhood secrets to her.

Everything.

Aurore couldn’t bear the thought. She really was the coward she had claimed to be. “No. It’s best she not come home until…”

“I understand.”

“There’s only so much I have the strength to do.”

Spencer rose. “Then I’ll send her your letter and send the others theirs…when I must.”

“Yes. The letters.” She thought of the letters, which she had dictated herself. And all the lives that they would change.

“You’re tired. And you still have another visitor.”

Aurore didn’t ask who the visitor was. She was certain from the sound of Spencer’s voice that it was some one she would be glad to see.

Aurore knew when Spencer left the room, although her eyes were closed by then. The cicadas’ song grew louder, and she could picture the insects’ hard-shelled, alien bodies sailing from limb to limb of the moss-covered live oaks bordering her Garden District yard. With the windows open, the evening air was redolent of the last of the sweet olives and the first of the magnolias, and it masked the fragrances of an old woman’s life and impending death.

She heard footsteps, but she didn’t have the strength to open her eyes once more. A hand took hers, a firm, strong hand. She felt lips, warm against her cheek.

“Phillip,” she whispered.

“You don’t have to talk, Aurore. I’ll stay for a while anyway. Just rest now.”

The voice was Phillip’s, but for a moment it was Rafe by Aurore’s side. In that instant, she was no longer old, but young once more. Her life was ahead of her, her decisions were not yet made. As she drifted toward dreams, the cicadas’ song became one dearer and more familiar. Phillip was humming one of the songs his mother had made famous when Aurore fell asleep.

CHAPTER ONE

September 1965

The young man Dawn Gerritsen picked up just outside New Orleans looked like a bum, but so did a lot of students hitchhiking the world that summer. His hair wasn’t clean; his clothes were a marriage of beat poet and circus performer. To his credit, he had neither the pasty complexion of a Beatles-mad Liverpudlian nor the California tan of a Beach Boy surfer. In the past year she had seen more than enough of both types making the grand tour of rock bands and European waves.

The hitchhiker’s skin was freckled, and his eyes were pure Tupelo honey. Biloxi and Gulfport oozed from his throat, and the first time he called her ma’am, she wanted to drag him to a sun-dappled levee and make him moan it over and over until she knew, really knew, that she was back in the Deep South again.

She hadn’t dragged him anywhere. She didn’t even remember his name. She was too preoccupied for sex, and she wasn’t looking for intimacy. After three formative years in Berkeley, she had given up on love, right along with patriotism, religion and happily-ever-afters. Her virginity had been an early casualty, a prize oddly devalued in California, like an ancient currency exchanged exclusively by collectors.

Luckily her hitchhiker didn’t seem to be looking for intimacy, either. He seemed more interested in the food in her glove compartment and the needle on her speedometer. After her initial rush of sentiment, she almost forgot he was in the car until she arrived in Cut Off. Then she made the mistake of reaching past him to turn up the radio. It was twenty-five till the hour, and the news was just ending.

“And in other developments today, State Senator Ferris Lee Gerritsen, spokesman for Gulf Coast Shipping, the international corporation based in New Orleans, announced that the company will turn over a portion of its land holdings along the river to the city so that a park can be developed as a memorial to his parents, Henry and Aurore Gerritsen. Mrs. Gerritsen, granddaughter of the founder of Gulf Coast Shipping, passed away last week. Senator Gerritsen is the only living child of the couple. His brother, Father Hugh Gerritsen, was killed last summer in a civil-rights incident in Bonne Chance. It’s widely predicted that the senator will run for governor in 1968.”

Although the sun was sinking toward the horizon, Dawn retrieved her sunglasses from the dashboard and slipped them on, first blowing her heavy bangs out of her eyes in her own version of a sigh. As she settled back against her seat, she felt the warmth of a hand against her bare thigh. One quick glance and she saw that her hitchhiker was assessing her with the same look he had, until that moment, saved for her Moon Pies and Twinkies. Dawn knew what he saw. A long-limbed woman with artfully outlined blue eyes and an expression that refuted every refined feature that went with them. Also a possible fortune.

He smiled, and his hand inched higher. “Your name’s Gerritsen, didn’t you say? You related to him?”

“You’re wasting your time,” she said.

“I’m not busy doing anything else.”

She pulled over to the side of the road. A light rain was falling and a harder one was forecast, but that didn’t change her mind. “Time to stick out your thumb again.”

“Hey, come on. I can make the rest of the trip more fun than you can imagine.”

“Sorry, but my imagination’s bigger than anything you’ve got.”

Drawling curses, he reclaimed his hand and his duffel bag. She pulled back onto the road after the door slammed shut behind him.

She was no lonelier than she had been before, but after the news, and without the distraction of another person in the next seat, Dawn found herself thinking about her grandmother, exactly the thing she had tried to avoid by picking up the hitchhiker in the first place. This trip to Grand Isle had nothing to do with pleasure and everything to do with Aurore Le Danois Gerritsen. On her deathbed, Aurore had decreed that her last will and testament be read at a gathering at the family summer cottage. And the reading of the will was a command performance.

The last time Dawn drove the route between New Orleans and Grand Isle, she’d only had her license for a year. South Louisiana was a constant negotiation between water and earth, and sometimes the final decision wasn’t clear. She had flown over the land and crawled over the water. Her grandmother had sat beside her, never once pointing out that one of the myriad draw bridges might flip them into murky Bayou Lafourche or that some of the tiny towns along the way fed their coffers with speed traps. She had chatted of this and that, and only later, when Aurore limped up the walk to the cottage, had Dawn realized that her right leg was stiff from flooring nonexistent gas and brake pedals.

The memory brought an unexpected lump to her throat. The news of her grandmother’s death hadn’t surprised her, but neither had she truly been prepared. How could she have known that a large chunk of her own identity would disappear when Aurore died? Aurore Gerritsen had held parts of Dawn’s life in her hands and sculpted them with the genius of a Donatello.

Some part of Dawn had disappeared at her uncle’s death, too. The radio report had only touched on Hugh Gerritsen’s death, as if it were old news now. But it wasn’t just old news to her. Her uncle had been a controversial figure in Louisiana, a man who practiced all the virtues that organized religion espoused. But to her he had been Uncle Hugh, the man who had seen everything that was good inside her and taught her to see the same.

Two deaths in two years. The only Gerritsens who had ever understood her were gone now. And who was left? Who would love her simply because she was Dawn, without judgment or emotional bribery? She turned up the radio again and forced herself to sing along with Smokey Robinson and the Miracles.

An hour later she crossed the final bridge. Time ticked fifty seconds to the minute on the Gulf Coast. Grand Isle looked much as it had that day years before when she had temporarily crippled her grandmother. Little changed on the island unless forced by the hand of Mother Nature. The surf devoured and regurgitated the shoreline, winds uprooted trees and sent roofs spinning, but the people and their customs stayed much the same.

The island was by no means fashionable, but every summer Dawn had joined Aurore here, where the air wasn’t mountain-fresh and the sand wasn’t cane-sugar perfection. And every summer Aurore had patiently patched and rewoven the intricate fabric of Gerritsen family life.

Today there was wind, and the surf was angry, al though that hadn’t discouraged the hard-core anglers strung along the shoreline. A hurricane with the friendly name of Betsy hovered off Florida, and although no body really expected her to turn toward this part of Louisiana, if she did, the island residents would protect their homes, pack their cars and choose their retreats be fore the evacuation announcement had ended.

Halfway across the length of Grand Isle, Dawn turned away from the gulf. A new load of oyster shells had been dumped on the road to the Gerritsen cottage, but it still showed fresh tire tracks. The cottage itself was like the island. Over the years, Mother Nature had subtly altered it, but the changes had only intensified its basic nature. Built of weathered cypress in the traditional Creole style and surrounded by tangles of oleander, jasmine and myrtle, it was as much a part of the landscape as the gnarled water oaks encircling it. Even the addition, de signed by her grandmother, seemed to have been there forever.

Dawn wondered if her parents had already arrived. She hadn’t called them from London or the New Or leans airport, sure that if she did they would expect her to travel to Grand Isle with them. She had wanted this time to adjust slowly to returning to Louisiana. She was twenty-three now, too old to be swallowed by her family and everything they stood for, but she had needed these extra hours to fortify herself.

As she pulled up in front of the house she saw that a car was parked under one of the trees, a tan Karmann Ghia with a California license plate. She wondered who had come so far for the reading of her grandmother’s will. Was there a Gerritsen, a Le Danois three times re moved, who had always waited in the wings?

She parked her rented Pontiac beside the little convertible and pulled on her vinyl slicker and brimmed John Lennon cap to investigate. The top was up, but she peered through one of the rain-fogged windows. The car belonged to a man. The sunglasses on the dashboard looked like an aviator’s goggles; a wide-figured tie was draped over a briefcase in the rear.

She wrapped her slicker tighter around her. Mary Quant had designed it as protection against London’s soft, cool rain. Now it trapped the Louisiana summer heat and melted against Dawn’s thighs, but she didn’t care. Her gaze had moved beyond the car, beyond the oleander and jasmine, to the wide front gallery. A man she had never expected to see again leaned against a square pillar and watched her.

She was aware of rain splashing against the brim of her hat and running in streams across her boots, but she didn’t move. She stood silently and wondered if she had ever really known her grandmother.

Ben Townsend stepped off the porch. He had no protection, Carnaby-mod or otherwise. The rain dampened his oxford-cloth shirt and dark slacks and turned his sun-streaked hair the color of antique brass. His clothes clung to a body that hadn’t changed in the past year. Her eyes measured the span of his shoulders, the width of his waist and hips, the long stretch of his legs. Her expression didn’t change as he approached. Repressing emotion was a skill she had cultivated since she saw him last.

“I guess you didn’t expect me.” He stopped a short distance from her, as if he had calculated to the inch exactly how close she would allow him to come.

“A masterpiece of understatement.”

“I got a letter asking me to come for the reading of your grandmother’s will.” He shoved his hands in his pockets. Dawn had seen him stand that way so many times, shoulders hunched, palms turned out, heels set firmly in the ground. The stance made him real, not a shadow from her memories.

“I’m surprised you bothered.” She rocked back on her heels, too, as if she were comfortable enough to stand under the dripping oak forever. “Expecting to find a story here?”

“Nope. I’m an editor now. I buy what other people write.”

For the past year, Ben had worked for Mother Lode, a celebrated new magazine carving out its niche among California’s liberal elite. Dawn had read just one issue. Mother Lode obviously prized creativity, intellect and West Coast self-righteousness. She wasn’t surprised Ben had moved quickly up its career ladder.

“You always were good at pronouncing judgment,” she said.

He hunched his shoulders another inch. “And you seem to have gotten better at it.”

“I’ve gotten better at lots of things, but apparently not at understanding Grandmère. I can’t figure if inviting you was an attempt to force a lovers’ reunion, or if she just had a twisted sense of humor.”

“Do you really think your grandmother asked me here to hurt you?”

“You have another explanation?”

“Maybe it has something to do with Father Hugh.”

She tossed back her hair. “I don’t know why it should. Uncle Hugh’s been dead a year.”

“I know when he died, Dawn. I was there.”

“That’s right. And I wasn’t. I think that was the subject of our last conversation.”

That conversation had taken place a year before, but now Dawn remembered it as if Ben’s words were still carving catacombs under her feet. She had been standing beside Ben’s hospital bed on the afternoon after her uncle’s death. A nurse had come at the sound of raised voices, then scurried away without saying a word. Dawn could still remember the smell of lilies from an arrangement on another patient’s bedside table and the tasteless Martian green of gladiola sprays. Ben had shouted questions and waited for answers that never came.

“Did you know, Dawn? Did you know that your uncle was going to be gunned down like a common criminal? Did you know that a mob was on its way to that church to turn a good man into a saint and a martyr?”

“Look, I’m staying,” Ben said. “I don’t know why I was invited here, but I’m going to stay long enough to get some answers. Can we be civil to each other?”

“You’re a Louisiana boy. You know hospitality’s a tradition in this part of the world. I’ll do my part to live up to it.”

Dawn studied him for another moment. His hair was longer than it had been a year ago, as if he had made the psychological transition from Boston, where he had worked on the Globe, to San Francisco. He wore glasses now, wire-framed and self-important. He no longer looked too young to have answers to all the world’s problems. He looked his full twenty-seven years, like a man who had found his place in the world and never in tended to relinquish it.

Her father was a man who also radiated confidence and purpose. Dawn wondered what would happen when Ferris Lee Gerritsen discovered that Ben Townsend had received an invitation to Grand Isle.

Ben waited until her gaze drifted back to his. “I’m not going to push myself on you.”

“Oh, don’t worry about me. Nobody pushes anything on me these days. And nobody puts anything over on me, either. Stay if you want. But don’t stay because you want to finish old conversations.”

“Maybe there’ll be some new conversations worth finishing.”

She shrugged, then turned back to her car for her lug gage, making a point of dismissing him. She had left al most everything she owned in Europe. She reached for her camera case and her overnight bag, but left her suit case inside.

In the distance, thunder exploded with renewed vigor, and the ground at Dawn’s feet seemed to ripple in response. The sultry island air was charged with the familiar smells of ozone and decay. By the time she straightened, Ben was no longer beside her. She watched as he walked down the oyster-shell drive, glad she didn’t have to pretend to be casual even a moment longer.

She might not have understood Grand Isle’s draw for her grandmother, but each year Dawn had been drawn to it herself. The summers had been a time to bask in her grandmother’s love. Nothing else had been expected of her. The sun had been too hot, the occasional breeze too enticing. She had done nothing of consequence on the island except grow up. But Aurore’s pride in her had been the solid ground that Dawn built the best part of herself upon.

How proud had Aurore been before she died, and what had she known? Had she known that Dawn still loved her? That despite her exodus after her uncle’s death, she had still yearned for her family? That falling in love with Ben Townsend so long ago had not been the same as declaring sides in a war Dawn had never understood anyway?

Most important of all, had her grandmother understood that even though Dawn had crossed an ocean, she had never really been able to break free of any of the people she loved?

Louisiana was a statewide Turkish bath, which might explain the inability of its residents to move forward into the twentieth century. Their brains were as steamed as Christmas pudding, their collective vision as fogged by heat and humidity as the air on an average afternoon. On a day like this one, when raindrops sizzled in the summer air, it was possible to see why nothing ever changed, and nothing was ever challenged.

Ben stood on the beach and watched the foam-tipped breakers rearrange a mile of seaweed. Grand Isle was an obscure sandpile, projecting like an obscene middle finger into water the temperature of piss. In the hour since his encounter with Dawn, he had walked nearly the entire length of it.

Louisiana wasn’t Ben’s favorite place. He had been born not far from Grand Isle, but a year ago he had al most died there, too. A year ago he had watched as a martyr was gunned down by bigots and left to bleed away his life, one drop at a time.

Where was Father Hugh Gerritsen now? Ben didn’t believe in heaven any more than he believed that hell could be worse than Louisiana. Somehow, though, he couldn’t believe that Father Hugh’s life had been over between one drop of blood and the next. Maybe he had come back to earth—for a Catholic priest, he’d been surprisingly eclectic in his theology—and even now was toddling around somewhere, preparing to give humanity’s inhumanities one more run for their money.

What would Father Hugh think of his niece? The woman in the violent purple slicker had certainly looked in need of a priest—or a convent. Her legs were a mile long, her hair was a red-brown sweep ending—not accidentally, he was certain—at the exact tip of her breasts. A year in Europe had taken her from a debutante in flowered shirtwaists to a vixen in a pop-art miniskirt.

And those eyes, those challenging, provocative eyes. She had learned to use them, too. She had gazed straight through him as if he had never been her lover. As if he had never accused her of participating in her uncle’s murder.

Hadn’t he known that she would be shocked to see him, and that shock would turn to anger? Maybe. But he hadn’t expected the ice-cold arrogance, the chip on her shoulder as massive as one of the island’s oaks. Whatever Aurore Gerritsen had planned for them, it wasn’t this instant animosity, this reduced equation of a relationship once rich in respect and love.

In the distance, against the stark silhouette of an off shore oil platform, Ben watched fishermen hauling in a circular net filled with the shining, flopping bodies of mullet. Their boat rode the waves, and the net dipped and lurched as they dragged it on board. He winced, empathizing with the mullet who were gasping their last breaths as they struggled to free themselves from a force they couldn’t understand.

He didn’t understand Dawn, and he didn’t understand her grandmother or her reasons for inviting him here. He didn’t understand the malaise that surrounded the Gerritsens’ lives, or how they had failed to detect it. Worse, like the mullet, he didn’t know how to fight what he couldn’t see.

The sun had nearly disappeared. Now, banked behind thunderclouds, it glowed just a short distance from the horizon. Ben knew it was time to return to the Gerritsen cottage. He had given Dawn enough time to get used to the idea that he was back in her life. He had probably given her parents time to arrive, and anyone else who had been invited, too. He trudged across sand and crunched his way through a fifty-yard stretch of wild flowers and sea grasses. Ozone and the herbal essence of the vegetation scented the air. Behind him, as a light rain began again, he heard the triumphant cawing of sea gulls feasting on the mullet the fishermen had missed.

He was halfway back to the cottage when the heavens opened and the rain began in earnest. He was al ready wet, but with darkness falling, his tolerance was disappearing fast. The main road bisecting the island was lined with fishing camps and the occasional store that served them. He headed for the closest one to wait out the worst of the storm.

Ten steps led up to the wood-frame building, which was no larger than a three-car garage. Inside there were two narrow aisles flanked with counters and shelves. Of more interest were the occupants.

The storekeeper was lounging against the counter. A man who’d embraced his fifties without an argument, the storekeeper was balding, stooped and paunchy. When he smirked at the younger man who was standing across from him, his tobacco-stained teeth were an inch too long.

So enthusiastically was he staring and smirking, the storekeeper didn’t even notice Ben. “Well, boy,” he said to the man in front of him, “I might know where the house is, and I might not. Depends on why you want to know. Me, I can’t figure why a nigger’d be looking for Senator Gerritsen’s house after dark, unless he’s got something on his mind he shouldn’t.”

Ben stood in the doorway and watched the other man—a man who, at thirty-seven, hadn’t been a boy for two decades—react to the storekeeper’s words. Ben recognized him. He waited for his reaction.

Phillip Benedict leaned across the counter. “Now if I wanted to kill Senator Gerritsen, coon ass, you think I’d stop here first so you could remember exactly what I looked like?”

The storekeeper cranked himself up to a full five-foot-four, but he needed an additional ten inches to be Phillip’s equal. Actually, Ben concluded, he needed a whole lot more than inches.

“Get out of my store! Go on. Get! And watch your back while you’re on the island. Might find yourself riding the waves facedown if you don’t!”

Phillip had beautiful hands, long-fingered and broad. One of them gathered the material of the storekeeper’s shirt and twisted it so that he couldn’t move away. “It would take a very quiet man to sneak up on me, coon ass. You don’t have that kind of quiet. You got a big mouth. I’d hear it yapping a mile away. So you be careful, ‘cause while you’re yapping, I might just sneak up on you. And you wouldn’t hear me.” He let go of the shirt and pushed the man away from the counter. Then he turned. His eyes met Ben’s. For a moment, he didn’t move.

“Coon ass?” Ben asked.

“Wish I’d coined the phrase.”

Ben looked past Phillip to the storekeeper, who was edging toward the wall. “He’s a mean son of a bitch,” he told the man. “Eats white folks for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Now, I’d be careful. All that, and a friend of the Gerritsen family, too. He’s a good man to stay away from.”

“Both of you get out!”

“Bad for business to be so rude.” Ben picked up a candy bar and fished for some change, which he laid on the counter. “Want anything, Benedict?”

“Yeah. A head on a platter.”

“Next store down the road.” Ben draped an arm around Phillip’s shoulder. “Let’s see what we can do.”

They exited that way, although Ben kept his eye on the storekeeper until they were safely out the door. “About now is a good time to make tracks,” he said at the bottom of the steps. “Do you have a car?”

“Sure as hell didn’t hitchhike.”

“Let’s go.”

When they were both in the car, Phillip pulled onto the road, and they were quiet until he’d taken one of the turns off the main route and parked in front of the is land’s Catholic church. Phillip was the first to speak. “Sun’s going down, white boy. Ain’t safe for niggers or agitators on a backass Looziana road.”

“What in the hell are you doing here?”

Phillip lifted a brow. “I could ask the same.”

Ben tried to imagine how he could explain something he didn’t understand himself. In the meantime, he examined the other man.

Phillip Benedict was a journalist of note. He was widely praised for his insight and biting commentary, but it was his color and his convictions about prejudice and freedom that set him apart from other Ivy League—educated newsmen. From jailhouse interviews with Martin Luther King to his assessment of the achievements of the late Malcolm X, Phillip had reported the struggle for civil rights like a war correspondent. More times than not, he had been right in the thick of battle.

The two men had liked each other from their first encounter, years before. They had been covering the same story in New York, Ben as a young reporter right out of college and Phillip as a seasoned journalist. They had spent a long night together in a Lower East Side bar along with half a dozen other newsmen, waiting for someone to emerge from a building across the street. Phillip had taken Ben under his wing, and with hours to kill they had traded their personal stories. But over the years they hadn’t spent much time in each other’s presence, and over the past year none at all. Their lives and their careers had taken them in different directions.

“I’m not exactly sure why I’m here,” Ben said. “But I was invited to the reading of a will. You?”

“Seems I’ve been invited, too. Aurore Gerritsen was one interesting old lady.”

Ben shifted so that his back was against the car door. He had known from the conversation in the store that Phillip’s presence on Grand Isle had something to do with the Gerritsen family, but he hadn’t really expected this. He had guessed that Phillip was looking for a story.

Or feeling suicidal.

Raindrops glistened in Phillip’s hair and on the dark hollows of his cheeks. He didn’t look any the worse for his confrontation with the storekeeper. In fact, he looked like a man waiting for new challenges. “This is getting stranger by the moment,” Ben said. “Why you?”

Phillip smiled. “You told the man. I’m a friend of the family.”

“I was just trying to keep your ass in one piece. What’s the real reason?”

Phillip shifted, too, trying to make room for his long legs. “Are you entertaining theories?”

“Yeah, and you could entertain a whole lot more than that by coming to a place like Grand Isle and manhandling the locals.”

Phillip took his time looking Ben over before he spoke again. “Do you know why you were invited?”

“How much do you know about the Gerritsens?” Ben reached into his shirt pocket for the Butterfingers he’d bought at the store. He ripped it open and broke it in two, offering half to Phillip.

Phillip declined with a shake of his head. “I just know what I’ve been told.”

“How much do you know about Father Hugh Gerritsen?” Ben asked.

“I know he was killed last year. Over there in Bonne Chance.” Phillip hiked his thumb over his shoulder.

“Yeah. A short sail, or a hell of a trip by car. I was born there, and sometimes I wake up in the middle of the night and I’m there again. I can feel the heat and the damp settling all over me, and I’m back in Bonne Chance.”

“You were there when he died, weren’t you?”

Ben wasn’t surprised that Phillip knew. They had never talked about it, but the story had been covered in the national media. “I was there. But there’s more to it than that. His niece and I…” He shrugged. “Dawn and I were close.”

“That right?”

“All I really know is I’m here, and I’m planning to stay.”

“So am I.”

“You’ve avoided telling me why you were invited.”

“I don’t know for sure.”

“But you could guess if you had to?”

“I got to know Mrs. Gerritsen at the end of her life. My being here has something to do with that.”

“Do you know anybody else who’s coming?”

Phillip gave a half smile that Ben could have interpreted a hundred different ways. “My mother and step father.”

Ben gave a low whistle. He had never met Phillip’s family, but he had heard Phillip’s mother sing a thou sand times. She was Nicky Valentine, a world-famous jazz and blues singer who owned a nightclub in New Or leans.

“Got their invitations the same day I got mine,” Phillip said.

Ben had a hundred questions, but Phillip had a journalist’s natural reticence. Ben would get his answers when they all gathered back at the cottage. “This is going to be even more interesting than I thought.”

Phillip’s smile hardened into something else. “Especially when the senator and his wife find out who’s been invited to their house.”

“I wouldn’t turn my back on him, if I were you.”

Phillip swiveled in his seat and reached for the ignition. “We’ve got questions, both of us, and they need answering. Maybe it’s time we found out what’s planned. But whatever it is, it’s not going to be boring. There’s a story here. Dark and light folks, tapping together to an old lady’s song.”

Ben was silent as Phillip started the car. The rain had slacked off again, but the sky was almost dark. He imagined that everyone who had been invited to hear the will was at the cottage by now. Maybe Phillip was right. Maybe a story would unfold in the next hours. But one thing was for certain. During her lifetime, Aurore Le Danois Gerritsen had been a woman to reckon with. Even now, even in death, she was still determined to have her way.

CHAPTER TWO

At seventy-four, Spencer St. Amant should have had nothing to worry about except whether an afternoon thundershower was going to keep him from taking a stroll down Esplanade Avenue. But while his cronies gathered at the Pickwick Club and talked incessantly about their days in the sun, Spencer sat in his Canal Street law office and directed the parade of fresh-faced Tulane graduates who did his legwork.

He had considered retirement once, a decade before. In a private dining room at Arnaud’s he had thought it over between courses of shrimp remoulade and trout meunière. And when the last bite of trout was vanquished, he had walked back to his office and announced to his staff that the jockeying for position could cease immediately. Someday they would find him at his desk, facedown amid volumes of the Louisiana legal code. Until then, he was still in charge.

Spencer doubted that anyone had ever suspected the reason for his decision. He wasn’t married to the law, and most parts of mediating society’s quarrels didn’t appeal to him. As a youth, he had wanted to fly. He had dreamed of soaring above the clouds like the Wright brothers, exploring every corner of the world stretched before him. Instead, he had stayed on the ground to fulfill his duty to his family.

His duty to the long-dead St. Amants who had taken such pride in the family firm had been discharged long ago. But his duty to the woman he had loved had not. Aurore Gerritsen had never known that he continued his law practice to stay close to her side. She had died his friend and client, more than he could ever have hoped for if he told her the truth.

His duty to her was not yet ended. There were still her last wishes to fulfill. One final act of love.

Despite the rain, Spencer moved slowly up the path to the Gerritsen cottage. As he drew closer, he was re minded of the first time he had gone up in an airplane. The airfield had once been acres of corn, and as the flimsy two-seater began its take-off, he had been thrown from side to side. Decades had passed, many more than he cared to think about, but he still remembered that moment of terror when he had realized that his life was about to be transformed, that something more than a plane had been set in motion and couldn’t be halted.

On the front gallery, he knocked and waited. At the sound of footsteps he waved to his driver, who had al ready deposited his suitcase by the front door. The young man promptly backed down the drive and disappeared with a squeal of Spencer’s own tires. Spencer held himself erect—a considerable feat—and stood back as Pelichere Landry came outside to greet him. She was a stout woman with the dark hair of her Acadian ancestors and an unswerving and clear-eyed devotion to Aurore Gerritsen. She, and her mother before her, had taken care of the Gerritsen family for as long as Spencer had known any of them.

“I’m glad to see you standing there,” he said. “I didn’t know who would be here.”

“Mais yeah, I can tell that.” Pelichere stepped away from him so that she could get a better look.

He felt her appraising gaze and tried to stand a little straighter. “I’m fine.”

“You don’t look so fine.”

“Before I get any surprises, you’d better tell me. Is anyone else here yet?”

“Dawn’s up in her room. I made her eat. Ben Towns end, he came. He went.”

“He’ll be back,” Spencer said.

“The others are coming? Still?”

Spencer nodded.

“Aurore, she always did what she thought was best. Even when it wasn’t.” Pelichere picked up Spencer’s suitcase. “Your room’s ready, and there’s coffee in the kitchen.”

The sound of a car engine chased the lure of both from Spencer’s head. He turned as a dark, sleek Lincoln came to a halt under the oaks. “The senator,” he said, although he was sure Pelichere already knew that.

“Me, I’ve got other fish to fry.” The door banged shut behind Pelichere, and Spencer was left alone to greet Ferris Lee and Cappy Gerritsen. He watched as Ferris got out to open the door for his wife.

Ferris Lee Gerritsen wasn’t classically handsome. He was barrel-chested and broad-shouldered, with a high forehead and gray hair that was still thick enough to require a good haircut. His nose had been broken more than once, and the arrogant thrust of his chin had invited punches, too.

But what was the exact shape of a nose, the cut of a jaw, compared to personal magnetism? He had eyes that crackled with patriotic fervor and a resonant voice that could stroke or destroy. Combined with a rare understanding of the hopes and prejudices of his constituents, his charisma could usher him into the governor’s mansion in 1968.

Cappy Gerritsen, blond and petulant, was dressed as if she were setting out for an afternoon of bridge and gossip. Her white linen shift stopped just above her knees, but it wasn’t short enough to be in poor taste. Many things could be said about Cappy, but never that her taste was poor.

Ferris wasted no time on pleasantries. He spoke be fore he reached the porch. “Maybe we can get down to business before this place is blown to Hades and back.”

“I listened to the forecast on my trip down,” Spencer said. “There’s nothing to worry about yet. Maybe not at all.”

“I’ve tried to reach you a dozen times in the last few days.”

“Have you?” Spencer knew full well that a dozen was a low estimate.

“I don’t understand the point of this. I’m supposed to be in Baton Rouge this week. Why couldn’t we read the will in New Orleans?”

“I’d rather talk about the reasons when everyone’s here.”

Ferris’s expression had been anything but cordial; it grew less so. “And just who’s expected?”

“I’d like to know if my daughter’s arrived,” Cappy said, before Spencer could answer.

“Dawn is here, though I haven’t seen her yet.”

“Well, at least she hasn’t entirely forgotten she has a family.”

Spencer watched Ferris silence his wife with a frown. “Suppose you forget about everybody else for a minute,” Ferris said, “and tell me exactly what’s going on?”

“I’m following your mother’s wishes. That’s all I can say.”

“That’s all you will say. I—” Ferris’s gaze went from Spencer’s face to the drive. A small car, one of Detroit’s newer compacts, was approaching the house.

Spencer wished he had a chair. He also wished for a Ramos gin fizz, although the days when it would have agreed with him were long over. “And who’s this?” Ferris asked.

Spencer watched a tall man unfurling himself from behind the steering wheel. As Phillip Benedict approached, Spencer admired the elegant posture, the strong, even features.

Ferris answered his own question. “Ben Townsend.”

Until that moment, Spencer had noticed only one man; now he switched his gaze to the other. Ben was nearly as tall as Phillip, with the same lithe confidence of movement. The confidence of the young.

Ferris stepped forward. Ben thrust his hands in his pockets and rocked back on his heels. He assessed Ferris before he spoke. “Good evening, Senator Gerritsen.”

“You’re not welcome here.” Ferris didn’t look at Phillip. “Neither is your…friend.”

Spencer crossed the porch before Ben could respond. He extended his hand to Phillip. “Phillip.” Then he turned to Ben and held out his hand. “I’m Spencer St. Amant. Thank you for coming.”

“Hasn’t this gone far enough?” Ferris asked. “I want to know what this is about.”

“Well, I’ll tell you what it’s about, Senator,” Phillip said. He smiled pleasantly, although he was carefully assessing everyone as he spoke. “My name’s Phillip Ben edict. Your mother invited Townsend here and me to hear her will. Now, sure as you’re her representative in the land of the living, I know you’re going to make us right at home.”

“You could never feel at home here.”

“As your mother’s attorney, I welcome Ben and Phillip in her name.” Spencer turned away from Ferris and Cappy, to signal that his business with them was completed. “I just got here myself, but I know there have been beds prepared for you.”

Phillip’s reply was drowned out by the sound of an other car. Both young men turned to see who was coming. Spencer watched a late-model Thunderbird pull up the driveway. No one said a word as the car stopped be side Phillip’s and its two occupants got out. Phillip stepped forward as a man and woman walked slowly to ward him. “Hello, Nicky,” Phillip said.

Nicky stopped a short distance from her son. She nodded to him, her eyes wary; then she looked past Phillip to the porch. “Mr. St. Amant?”

Spencer smiled and stretched out his hand. Nicky introduced her husband; then she paused. “And Ferris Lee,” she said, inclining her head. “Ferris, you probably haven’t had the pleasure of meeting my husband, Jake Reynolds.”

Jake didn’t offer his hand, and Ferris didn’t move. Ben filled the gap by offering his to Nicky. “I’m Ben Townsend.”

Spencer watched them shake. He could not think badly of Aurore, but for a moment he wished that she had made different decisions in her lifetime. “I was just telling the others that beds have been prepared,” he said. “And I’m sure there’s dinner, if you haven’t eaten al ready.”

“Thank you, but we’re going to listen to this will, then we’re leaving,” Nicky said. “Maybe Aurore Gerritsen thought a little black-and-white pajama party would further the cause of civil rights, but I don’t savor the idea of staying in this house tonight.”

Spencer had expected resistance. He applied his gentlest coercion. “It’s much too late to think about driving back.”

“I’m afraid we have as little interest in being guests as Senator Gerritsen has in being our host.”

“I’m sorry, but it’s not that straightforward.”

“Let them go,” Ferris demanded.

Spencer had known that gentleness wouldn’t be enough. Somehow, it never was. He smiled sadly. “I’m afraid that’s not possible, Senator. Your mother stipulated that everyone has to spend the night at the cottage tonight. In the morning, I’ll share all the conditions for the reading of her will. But I’ll warn you now, it won’t hurt any of you to unpack everything you’ve brought. We’ll be spending four nights together.”

“What kind of charade is this?” Ferris asked. “You can’t keep us locked up here. I won’t tolerate it.”

Spencer sighed and remembered that moment when the ancient two-seater had lifted away from the earth and his world had changed forever. “I can’t keep you here,” he agreed. “But there’s one more thing I ought to tell you now. Anyone who leaves before the reading is completed will not inherit.”

Dawn heard Spencer’s final words from the hallway of the cottage. She started for the door, but before she reached it, Nicky Reynolds spoke. “I can’t imagine a woman I never met left me anything so significant that I should let myself be strong-armed.”

The screen door slammed shut behind Dawn. She should have expected it, because standards at the cottage were more relaxed than at any of the other Gerritsen homes. But she hadn’t, and she hadn’t expected to see Ben flinch, as if someone had just aimed a gun at him and pulled the trigger.

“Mrs. Reynolds, if my grandmother asked you here, it couldn’t have been to hurt you.” She walked down the porch steps, purposely concentrating on no one but Nicky and her husband. She had heard her father’s voice, but she wasn’t prepared to deal with him. Dawn had heard of Nicky Valentine Reynolds, of course. Nicky, who had never tolerated segregated audiences in a city famed for them, had always interested her, and the interest factor had just multiplied enormously.

“I’ll be happy to show you to your room,” Dawn said. “There’s a large one next to mine that I think you’ll like. You can see the Gulf if you have the determination.” She held out her hand to Nicky. “I’m Dawn Gerritsen. Please, I hope you plan to stay.”

Nicky lifted her hand with her signature languid grace. She introduced her husband, and Dawn felt her hand disappear into the hard flesh of his. Jake Reynolds was an imposing man, large and muscular enough to feel at ease anywhere. He seemed at ease now, but he stood close to his wife, hip edged toward hers, with the skill of a bodyguard.

Dawn turned so that she could see her parents, too. They had changed little in the months she was gone. Her mother was gazing into the distance. Her father was staring at her, his eyes narrowed, and for once his thoughts were visible for anyone to read. She knew the price she would pay when he got her alone. She spoke to him, as well as to Nicky. “No one here will hurt you. I give you my word.”

“Now that’s interesting,” Phillip said, “considering that the influence of this family couldn’t even keep one of its own from being gunned down like an animal.”

Dawn looked at Phillip for the first time. He was a stranger to her. “I’m sorry. We haven’t been introduced.”

“This is my son, Phillip Benedict,” Nicky said.

Dawn recognized the name. She had often read his work. Before she could respond, Jake spoke. “We’ll be staying. All of us.”

Dawn saw the rising tide of mutiny in Nicky’s eyes. Even angry, she was a stunning woman. Had she lived a century before, she might have danced at the French Quarter quadroon balls. Beautiful women of mixed racial heritage had been the cause of more than one duel in the nineteenth century. New Orleans society had seen fit to create a special place for them—minus the sanctity or the security of marriage vows, of course.

“We’ll stay the night,” Nicky said.

Dawn admired the way Nicky had neither agreed nor disagreed with her husband in public. They would stay the night. Clearly, whether they would stay longer remained to be worked out between them.

She listened as Ben offered to help with luggage. He was standing beside Phillip, and their similarities were more interesting than their differences. Both carried themselves as if they toted precious cargo, as if knowledge hard won set them apart from mere mortals. And although she had never seen Phillip before, he and Ben seemed united in their decision to condemn her and her family.

“Why don’t you come with me,” she told Nicky, “while the men bring your suitcases? You can tell me if there’s another room you’d like better.”

Nicky nodded. As they climbed the steps, Dawn realized that her father and mother were no longer standing on the gallery, but Spencer remained to oversee the settling-in. He looked exhausted.

Inside, she paused in the center hallway, compelled by the oddity of the circumstances to make small talk. “It’s a large house, though it doesn’t look like it from the outside. It was built by an Acadian family more than a hundred years ago. When I was a little girl, I used to lie awake at night and listen for their voices.”

“Did you ever hear them?”

“What would you think if I said yes?”

“That you have imagination.”

“I’m a photographer. Some people don’t think that takes imagination.”

“Some people don’t think singing other people’s songs takes imagination, either.”

Dawn felt the flush of camaraderie. She pointed out the layout of the rooms downstairs, then started up to the second floor. Her mother had disappeared, and Dawn hoped she wouldn’t meet her now. Since she had openly defied her father, she anticipated his appearance with even less enthusiasm.

She led Nicky to the bedroom at the end of the hall way in the addition. It was large and airy, furnished with pine and cypress antiques of straight, simple lines. The bed, a nineteenth-century tester, was draped in hand-crocheted lace.

“This was my grandmother’s room.” Dawn stepped inside. Immediately she was embraced by the entwined fragrances of roses and vetiver, fragrances she would al ways associate with Aurore. “I think you’ll be comfort able here. There’s a private bath.”

“Your grandmother’s room?”

“It’s one of the larger ones in the house, and it was her favorite, because there really is a view of sorts, if you step out here.” She walked to the French doors leading out to a small balcony and threw them open. Immediately fresh air swept into the room, licking at the scents.

“Why are you giving this room to me?”

Dawn faced her. “Why not?”

“You know the answer to that.”

Dawn was afraid she did. She was the daughter of Ferris Lee Gerritsen, noted for his opposition to civil rights, and blood was supposed to tell. “I hope you won’t hold my father’s prejudices against me. We’re not at all the same.”

“You’re not at all what I would have expected.”

“Well, you’re even more.” As a photojournalist, Dawn had learned to quickly assess faces. Nicky was one of those rare women who would be equally beautiful on film or in person. Her dark hair hugged her head in short, soft curls. Her eyes were an impenetrable green, the still surface of a tree-shaded bayou. Her features were broad and strong, sensual, earthy and somehow—and this fascinated Dawn most of all—wise. Nicky was at least as old as Dawn’s own parents, but age seemed only to have intensified her assets.

She realized she was staring. “You were a great favorite of Grandmère’s. I grew up listening to your voice. Seventy-eights at first. Then 45s. Then albums, with your photograph smiling at me from the record rack.”

“Your grandmother was a complete stranger to me.”

“I think you would have liked her.”

Nicky ran her hand over the lace coverlet, but she didn’t answer. Dawn heard footsteps on the stairs and realized that their private moment was about to end. “This situation is extraordinary, Mrs. Reynolds. Please tell me if there’s anything I can do to make it more comfortable for you.”

“It’s not going to be comfortable, no matter what any of us do.”

“You haven’t met Pelichere Landry yet. She was a friend of Grandmère’s, and she takes care of the cottage when no one’s here. I know she’s set out food in the kitchen. When you’ve settled in, please introduce your self, and she’ll show you where everything is.”

Dawn stepped aside as Jake and Phillip entered. Ben was carrying a suitcase, but he stopped in the doorway. Without a word, she moved past him.

“So you decided to come.” Phillip kissed his mother’s forehead, and didn’t have to bend far to do it. She was only half a head shorter than his six-foot-two.

“I don’t know why I did.” Nicky pushed him away before he could answer. She and Phillip had gone round and round about this invitation to Grand Isle since the moment it arrived. She had flatly refused to come, but somehow she had ended up here anyway. “And don’t bother telling me you don’t know why I was invited. You never could lie worth anything. You know a whole lot more about this situation than you’ve let on so far.”

“Have you had supper?” Jake asked Phillip.

“There weren’t a lot of places on the way down where I could have been sure to leave with a full stomach and a full set of teeth.”

Jake laughed, but both men knew the truth behind Phillip’s joke. Black humor, some called it. Both men had theories about that.

“Dawn told me that someone’s set out food for us in the kitchen,” Nicky said.

Jake set down the suitcase he had carried. “Suppose she meant we’ll be eating in the kitchen while the white folks eat in the dining room?”

“No, I don’t suppose that’s what she meant. She was trying to make us welcome.”

“If Dawn’s anything like her father,” Phillip said, “she can charm you right straight to the center of a lie, and you’ll never even know you’ve been there.”

“Would you like me to go down to the kitchen and see if I can get something to bring up?” Jake asked Nicky.

“I’d like that. Phillip?”

Phillip shrugged. “You don’t have to leave us alone, Jake.”

“Think I do.”

Nicky watched her husband leave. His footsteps were no longer audible when she spoke. “I think it’s time you did some explaining.”

Phillip wandered the room, stopping at a bedside table. Wildflowers bloomed in a cut-glass vase, and a handful of novels fanned out along the edges in invitation. “You’re one of the few people who know that Aurore Gerritsen hired me to write her life story. That she dictated it to me chapter and verse.”

“Knowing’s not the same as understanding.”

“Have you wondered just how far she went? How much she told me about her life?”

Nicky didn’t reply.

Phillip faced her. “She left out nothing.”

“How can you know what she left out?” She wandered to the French doors and gazed out over wizened water oaks bending in the wind.

Phillip joined her, putting his hand on her arm. His skin was smooth and brown in contrast to hers. “I can tell you this. I learned that a man I once called Hap, a man I knew in Morocco a long time ago, was really Hugh Gerritsen.”

She stiffened and shook off Phillip’s hand. “Is that why we’re here? Because once upon a time we knew Aurore Gerritsen’s son?”

“I think that’s some part of it.”

He had succeeded in making her look at him. “And what are the other parts?” she said.

“I can’t speak for Aurore. Not yet. But maybe I can speak for you. I think you came for answers to questions you gave up asking yourself a long time ago. Questions you’re going to need to share with Jake very soon. Be cause I don’t think any of us was invited here so that we could hold tight to our secrets.”

Something went still inside her. “You’ve always been the one with questions. That’s why you do what you do for a living. You probe and you probe, like a tongue that can’t keep away from a sore tooth.”

“If you worry a tooth long enough, eventually it gives way.”

“You think that’s what will happen here?”

“I think we can be assured of it.”

She wondered how much Phillip really knew about her relationship with Hugh Gerritsen, exactly how much he had been told and how much he remembered. Phillip had been young during those days so long ago, but his memory had always been extraordinary.

As if he could read her mind, he nodded. “You know to be careful, don’t you?” he asked.

“Careful of what? The truth? The senator?”

“The senator, for starters.”

“So we’re switching roles? When you were a little boy, I warned you about crossing the street, and now that I’m an old woman, you warn me about ghosts and bigots?”

“Something like that. Except for the old-woman part.”

“I know to be careful. I’m so careful I almost didn’t come. You be careful, too.”

“I’ve got careful running through my veins. Only reason my veins are still running.”

Jake appeared in the doorway with a tray. “I only had hands enough for two plates, Phillip. But there’s plenty more in the kitchen, and you’re welcome to come back up and eat with us.”

“I think I’ll just go settle in.”

Nicky followed her son to the door without saying anything more. She was both glad and sorry that their conversation was finished. Too much had been said, or perhaps not enough. She was too upset to know. When he was gone, she took glasses of iced tea off Jake’s tray.

Jake moved closer. “Are you all right?”

“I’m just fine.” She waited until he set the tray on the bed before she went into his arms.

She stood in his embrace and listened to the sound of thunder in the distance. Finally she pulled away. “There’s still time to leave, Jake.”

He pulled her close again, and she resisted for only a moment. “Do you want them saying you’re afraid? That you didn’t think you were good enough to face down the Gerritsens and find out what this is all about?”

She was all too afraid she knew what it was about. “I don’t care what anybody thinks.”

“You’d leave your son here to face them alone?”

“At least the food smells good,” she said at last.

“And there are some people here who might be worth knowing.”

Nicky thought of Dawn and the things Phillip had said about her. She wondered if Dawn knew how much she looked like the young Hugh Gerritsen.

“Shall we eat?”

Jake moved toward the bed, but he seemed in no hurry to get the tray. He smoothed his hand over the lace spread, much as Nicky had done herself. “Then I think we should retire for the night.”

“Retire’s not exactly the word you have in mind, is it?”

He flashed her his slow, certain-of-himself smile. “I figure if we’ve got to be here, there ought to be compensations.”

She considered telling him that no matter how important staying here was, she wouldn’t be able to if he wasn’t beside her. But she decided not to. She just smiled slowly and held out her arms. And in her own way, she let him know.

CHAPTER THREE

Cappy Gerritsen needed only one glance around the downstairs bedroom that she and Ferris always shared to set her off. “I told you we shouldn’t have come.”

Ferris didn’t raise an eyebrow or point out that she had been silent for the entire two-and-a-half-hour trip from New Orleans. Cappy frequently alternated between stony silences and passionate oratory. After twenty-some years of marriage, neither upset him greatly.

He lit a cigarette and watched the smoke spiral to the ceiling, where it was sternly disciplined by a fan. One of the few similarities between Cappy and his mother had been their mutual distaste for air-conditioning. Each spring his New Orleans home was held hostage to the heat and humidity until mid-June. The cottage, thanks to his mother’s whims, was unbearable the entire summer.

“Don’t look at me like that. You obviously feel the same way.” Cappy sucked in her bottom lip—a manner ism that had been adorably provocative on a debutante and was nothing short of irritating on a forty-seven-year-old matron.

Ferris snuffed the cigarette in a potted fern and lit an other. “I came out of respect for my mother.”

“That’s what you call driving all this way to be con fronted by these people?”

When Ferris didn’t try to soothe her, Cappy began fidgeting with the shells lined up along the top of a chest of drawers. “Surely you can’t think this makes any sense. Isn’t it bad enough that your mother ordered an immediate cremation? Everyone expected the family to announce the date and time for a funeral mass. Now this. When the word gets out, our friends will think your mother is still leading us around by our noses.”

“I doubt they’ll be that perceptive.”

She looked down at her arrangement, dissatisfied. She tried lining the shells up by size. “Dawn didn’t even call. I sent cables everywhere I could think of to tell her about your mother’s death, and she didn’t even call. Until I saw her standing on the gallery, I didn’t even know if she’d gotten the message.”

From the beginning, Ferris had understood the roots of Cappy’s little tantrum. He paid lip service to it, even as he silently tried to make sense of what his mother had done. “Dawn made it clear some time ago that she does what she wants.”

“This is ridiculous. I don’t want to stay here even one night. This can’t have any bearing on your inheritance.”

“As old as he is, Spencer St. Amant’s still a worthy adversary. He’s often done what he damned well pleased and gotten away with it. I’m sure that’s why Mother chose him to oversee this little drama.”

She moved a large conch to the center and stepped back to view it. “Well, I know the law, and the law says your mother had no choice but to leave you a third of her estate.”

“Do we want a third, or do we want it all? There’s the controlling interest in Gulf Coast to consider.”

He watched as her hands went still. Gulf Coast Ship ping was the crown jewel of the Gerritsen family, a multimillion-dollar financial empire that was synonymous with the port of New Orleans and traffic on the Mississippi. Cappy’s own family was wealthy, but Gulf Coast, and Ferris’s connection to it, gave her the power in New Orleans society that she desired.

Ferris fully appreciated that desire. Cappy was an asset he had recognized long ago. When she chose, she could radiate breeding and charm, while simultaneously extolling her husband’s political virtues. Cappy, with her River Road plantation gentility, could work a room like a southern Jackie Kennedy.

He gave her a moment to consider before he continued. “I’ll talk to Spencer and insist he get this over with quickly. If he doesn’t agree, we could always take our chances and drive back to the city. But, of course, if we leave, we won’t know exactly what transpires here, will we?”

“You don’t miss a thing.”

He strolled to her side and leaned over to kiss her cheek. “You’ll stay, then?”

“As always, my choices seem limited.”

“Go ahead and unpack a few things. I’m going to explore and see what I can find out.”

When he reached the doorway, Ferris took one last look over his shoulder. Cappy was leaning over the chest once more, compulsively rearranging the shells. The room was simple, casual and quaint, as only rooms in a summer home can be. But there was nothing there, or in the sprawling twelve-room house, for that matter, that didn’t underscore the ambience of old money and tradition.

And there was nothing that didn’t reek of family now vanished forever.

Ferris had spent all the summers of his boyhood in this place. He hoped this was the last summer he would ever see it.

Dawn unpacked the few clothes she’d brought with her, then wandered the bedroom as memories stung her. Some things were much as they had been years before. The closet still held clothes she had worn as a teenager. A pink bathing suit with a pleated skirt lay in the bottom drawer of the pine dresser, faded rubber flip-flops tucked neatly under it. The view was one she remembered. She stopped at the window and gazed outside at a gray drizzle, leftovers from the earlier shower. The Gulf was just visible here, a wedge of turbulent water that mirrored her emotions.

She turned at the sound of rapping on her door. “Come in.”

Three men had helped shape her into the woman she had become. Ben was the third, her uncle Hugh the second. The man who appeared in her bedroom doorway was the first, and possibly the most important.

She nodded warily. “Daddy.”

Ferris smiled. “You must be my daughter. No one else calls me Daddy.”

She tapered her own smile into a warning. “If that keeps up, I’ll wish I hadn’t come home.”

“You should have called your mother, darling.”

“I know that.” She crossed the room and rose on tip toe to kiss his cheek. “I just needed some time alone to think about Grandmère’s death.”

“That’s one of your problems. You always think too much.”

She stepped away from him and shook her head. “This is the sixties. Women are allowed to think. You’d do well to remember that, if you want to be the next governor.”

“So you read, too. What do you think my chances are?”

Dawn thought his chances were good, but she thought telling him was a bad idea. The state of Louisiana would benefit from a humbler Ferris Gerritsen—but not as much as it would benefit from a more liberal man in the governor’s mansion. “What do you think?” she countered.

“I think you’d better face your mother and get it over with. She’s furious at you for not getting in touch.”

She put that aside for a moment, only too aware of the scene to come. “Daddy, do you know what this is about?”

“No, but I intend to find out. I don’t believe your grandmother really invited Nicky Reynolds and her family here.”

Dawn didn’t want to address that. Not yet. “Do you know why Ben Townsend was invited?”

His expression didn’t change, but then, his thoughts were rarely visible. “No. Are the two of you—”

She cut him off with a wave of her hand. “I haven’t seen him since…in a year.”

“Apparently your grandmother had a sense of humor I never appreciated.”

She stepped back to view him better. “Don’t dredge up old scores to settle with Ben.”

His expression was still pleasant. His voice was not. “Ben Townsend doesn’t belong in this house, and he doesn’t belong with you.”

That was undoubtedly true, but she didn’t want to give her father the satisfaction of knowing he was right. “That’s over now.”

“It should never have started.”

“If we could change history, there’d probably be more significant mistakes for both of us to worry about, wouldn’t there?”

His response was interrupted by a noise on the stairs. Dawn looked beyond her father to see her mother coming toward them. She added guilt to the carousel of feelings she had experienced in the past hour, and prepared herself. “Mother.”

Cappy Gerritsen stopped on the third step from the top, her posture regal. Dawn envisioned a younger Cappy, the prewar New Orleans debutante, gliding across the floor of her family’s River Road home with a volume of Emily Post on her head.

Cappy’s body was still gracefully curved and firm, and though she was a size larger than the six she claimed, neither age nor an extra fifteen pounds could destroy her basic beauty. No silver showed in her pale gold hair, and only twin frown lines between perfectly shaped eye brows signaled her basic dissatisfaction with life.

“Don’t badger Dawn, Cappy,” Ferris warned. “Just be glad she’s home.”

Dawn went to the head of the stairs, but her mother had made it impossible to embrace her. Cappy had al ways been three impossible steps away. “You look wonderful,” Dawn said. “Daddy’s plan to become the next Huey Long must agree with you.”

Cappy didn’t attempt to be polite. “You could have called.”

“I know.”

“Your grandmother dies, and you can’t even call your father or me to tell us you’re sorry?”

“Cappy.” Ferris joined his daughter. “Dawn and I have already discussed this.”

Dawn dredged up a smile. “I’ll go on record. I’m a failure as a daughter. Okay? Now can we go on to some thing else?”

“You disappeared off the face of the earth for a year. You didn’t call. You didn’t write. You didn’t visit. What are we to you, anyway?”

The smile died. “Right now you’re a living reminder of why I didn’t do any of those things.”

“Well, your grandmother’s not a reminder anymore, is she? Where were you when she needed you here?”

“You know where I was. I was in England, trying to find out if there was anywhere in this world where I could be something more than a member of this family.”

“You don’t have to be part of this family at all!”

Ferris stepped between them. “I’m not going to listen to any more of this.” He turned to Dawn. “There’s enough happening here without you and your mother going after each other.”

She shook her head in wonder. “My God, I’m a kid again.”

“Both of you are tired,” Ferris said. “This is a difficult time. Wait until you’ve rested before you talk.”

“I found Pelichere. She has drinks out for us.” Cappy started down the steps.

Dawn accepted Ferris’s brief hug, but she didn’t re turn it. “I’ll be down in a little while,” she said. “Let me comb my hair.”

She waited until he was gone before she took up her station at the window again. A year ago she had journeyed to another continent to banish her emotions, but now she knew she hadn’t succeeded. The child who had summered in this room was still inside her. The teenager who had longed for the love of her parents dwelt there, too. And the young woman who had given herself body and soul to Ben Townsend still cried out for understanding and forgiveness.

By the faint glimmer of a cloud-hazed moon, Pelichere swept the cottage gallery until not one grain of sand was lodged between the weathered boards. Dawn had offered to do it for her, but Pelichere had refused.

“I doubt anyone will even notice the fine job I’m doing,” Pelichere said, “but your mama would notice if the job wasn’t so fine. Mais yeah. She’d notice, just like she noticed the water stains on her bedroom ceiling, under the spot where the shingles blew off last week.”

Dawn leaned against a pillar, not at all anxious to go inside again. After an evening that had seemed endless, the house was quiet now, as if everyone had scurried to their rooms like ghost crabs hiding from shadows. She hoped they all stayed in their individual holes, particularly her parents. “Did she give you trouble?”

“How was I to know that storm would pry off shingles that haven’t budged in a century? At fifty-seven I’m supposed to climb up on the roof and inspect, shingle by shingle, every time it rains? I’d be up on the roof more than I’d be down on the ground. So maybe your parents should make their home on Grand Isle now that your grandmother, she’s dead. What shingles would blow off with Senator and Mrs. Ferris Lee Gerritsen living here?”

“Is it going to be their house after the will’s read? Seems to me Grandmère always said she was going to leave the house to you.”

“She said that, yeah. But there was more she didn’t say.”

A shrill whistle cut through the air. Pelichere turned and raised a hand in greeting as a pickup rattled along the oak-lined drive. “Joe and Izzy Means from down the road. Do you remember them, chère?”

“A little.”

Joe and Izzy got out, and Joe went around to the back of the truck, while Izzy trundled her substantial bulk up the path to the house. “I been cooking,” Izzy said, be fore she’d even reached the steps. “And cooking, cooking, cooking. It’s not right you should have to cook for the next four days, you with guests.”

Dawn was sure Izzy knew the so-called guests weren’t Pelichere’s. She supposed that was half the reason Izzy had arrived. In South Louisiana, keeping up with neighbors was still the favored evening recreation.

Pelichere introduced Dawn, and Dawn leaned over for Izzy’s enthusiastic kiss. Then she watched Joe, one ton to Izzy’s two, stagger up the path, well behind his wife, his arms loaded with grocery bags.

“What’d you go and do, Izzy?” Pelichere asked. “Drain the Gulf and cook everything left wriggling on the bottom?”

Pelichere scolded her friend while Joe made several trips from the truck. He left when he had finished, announcing that he was going down to the water to see what the dedicated fishermen still lining the beach were pulling in.

“Pelichere, you sit out here with Izzy,” Dawn said. “I’ll bring you both some coffee.”

Pelichere demurred, but Dawn ignored her. She re turned in a moment with cups and a pot of coffee Pelichere had left to drip in the kitchen. The coffee was thick and rich, black as goddamn, just the way Pelichere and Izzy liked it. Strong dark-roast coffee was as much a part of the local culture as seagulls and fishing luggers.