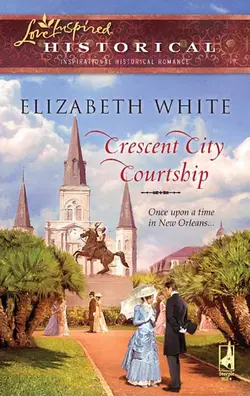

Crescent City Courtship

Elizabeth White

Indulge your fantasies of delicious Regency Rakes, fierce Viking warriors and rugged Highlanders. Be swept away into a world of intense passion, lavish settings and romance that burns brightly through the centuriesAbigail Neal dreams of escaping her life in the slums of New Orleans someday.But how can a woman alone unprotected ever fulfill her dreams of becoming a doctor? Then, young medical student John Braddock comes to pay a call on a neighbor. Though the scars left on her heart have taught her never to trust anyone, Abby is drawn to John's caring nature.Soon an unlikely friendship develops between the son of privilege the poor daughter of missionaries. But when Abby's mysterious past comes back to haunt her present, will she call upon her faith to help right a wrong make a new life with her very own Prince Charming?

“Tell me, Abigail, why it is you don’t subscribe to the belief of romantic love between marriage partners.”

She blinked and cut a glance at John. “What?”

“I’m curious to know if you are one of those women looking for all-consuming passion in a marriage partner.”

“I shall never marry.”

He laughed, assuming she was joking. But when she simply stared at him, his amusement faded. “You cannot be serious.”

She shrugged. “Who would marry me?” A faint smile traced her lips. “According to Dr. Pitcock, my head is too big.”

“No—what he said is that you are surprisingly normal for such a bright woman. I suppose you think there isn’t a man capable of keeping up with you.”

ELIZABETH WHITE

As a teenager growing up in north Mississippi, Elizabeth White often relieved the tedium of history and science classes by losing herself in a romance novel hidden behind a textbook. Inevitably she began to write stories of her own. Torn between her two loves—music and literature—she chose to pursue a career as a piano and voice teacher.

Along the way Beth married her own Prince Charming and followed him through seminary into church ministry. During a season of staying home with two babies, she rediscovered her love for writing romantic stories with a Christian worldview. A previously unmined streak of God-given determination carried her through the process of learning how to turn funny, mushy stuff into a publishable novel. Her first novella saw print in the banner year 2000.

Beth now lives on the Alabama Gulf Coast with her husband, two high-maintenance teenagers and a Boston terrier named Angel. She plays flute and pennywhistle in church orchestra, teaches second-grade Sunday school, paints portraits in chalk pastel and—of course—reads everything she can get her hands on. Creating stories of faith, where two people fall in love with each other and Jesus, is her passion and source of personal spiritual growth. She is always thrilled to hear from readers c/o Steeple Hill Books, 233 Broadway, Suite 1001, New York, NY 10279, or visit her on the Web at www.elizabethwhite.net.

Elizabeth White

Crescent City Courtship

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

While Jesus was having dinner at Levi’s house, many tax collectors and sinners were eating with him and his disciples, for there were many who followed him. When the teachers of the law who were Pharisees saw him eating with the sinners and tax collectors, they asked his disciples: “Why does he eat with tax collectors and sinners?” On hearing this, Jesus said to them, “It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick. I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners.”

—Mark 2:15–17

To Emma—because she loves historicals

and because she prays.

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Epilogue

Author’s Note

Questions for Discussion

Chapter One

New Orleans, November 1879

Gasping for breath, Abigail Neal pounded on Charity Hospital’s enormous oak front door, bruising her fist and driving a splinter into the heel of her hand. She’d covered the six blocks from the District at a flat-out run, but no one had offered to pick her up and take her to her destination. Not that she’d expected it.

“Come on, come on,” she muttered. “Someone answer the door.” She pounded again, this time with the flat of both hands. The sound echoed off the tall columns and wooden floor of the porch and reverberated through the hallway inside.

Where was everyone? Yanking the splinter out of her hand and sucking away a welling drop of blood, she peered through the little pane of glass in the door. Why lock the door of a hospital? To defend against marauding sick people?

Tess wasn’t going to make it if a doctor didn’t come soon.

Abigail was about to bang again when a pair of filmy, protruding eyes met hers on the other side of the window. The latch scraped back and the door opened, revealing a short, barrel-chested man with a pockmarked face. “You’ll have to go to the back door,” he said, squinting up at her. “Nurses are all in evening prayers.”

“I don’t need a nurse. I want a doctor.” Abigail forced herself to stand still, clutching her fingers together to keep from wringing her hands. People often wouldn’t help a person who seemed desperate.

The man scratched his head, disturbing the few wisps of gray hair clinging to his shining scalp. “Ain’t no doctors here to the front. That’s why I says go to the back and wait—that’s where the clinic is.” He looked her up and down. “You don’t look sick, no ways.”

“I’m not sick,” Abigail said, striving for patience. “I want you to fetch a doctor so that I can take him back to the—I want him to come with me.”

“Ain’t none here right now,” the guard repeated stubbornly. “Doc Laniere’s teaching a surgery lesson—”

“Doctor Laniere?” Abigail grabbed the man’s arm. “He’s the one I want. Someone told me he’s very kind and he’s the best doctor in the city.”

“He’s the best all right. But he’s busy, and—”

“Take me to him immediately.” Abigail straightened, well aware of the intimidating effect of her full height. “What is your name?”

“They call me Crutch.” The man glanced uneasily over his shoulder. “Mayhap I could see if Nurse Charlemagne—”

“I told you I don’t want a nurse. I want the doctor.” Abigail found herself on the verge of frustrated tears. Every moment of delay endangered not only Tess’s life but that of the baby. Pride hadn’t done a bit of good so far. “Please, Mr. Crutch. My friend is having her baby—she’s been laboring all day and most of last night. She’s getting weak, I don’t have a way to get her here and I don’t know what to do.”

An enormous sigh was followed by a clicking of tongue against teeth. “He’s gonna squash me like a mosquito,” Crutch muttered, then to Abigail’s relief, disappeared through a white pedimented doorway beyond the staircase.

Even though Crutch left the door standing wide, allowing an unobstructed view of the unadorned entryway, Abigail remained on the enormous two-story porch, unwilling to risk expulsion. She stood watching horse-drawn carriages rattle down Common Street. Some turned on Baronne before reaching the hospital, some continued to Philippa, where they rounded the corner of the beautiful green sward of grass which gave Common Street its name, then disappeared beyond tall rows of businesses. The scene was infinitely refined and orderly.

And she was going to bring the great doctor back with her to a tenement in the District. Well, he would just have to take her and Tess as he found them. She sat down on the broad top step of the porch and linked her fingers across her knees.

An interminable time later, Abigail heard the clatter of footsteps on the stairs behind her. She jumped to her feet and turned, expecting to see Crutch returning with the doctor. Instead she found a young man striding toward her with a black leather case in one hand and a fine felt hat in the other.

“I’m John Braddock,” he said with curt nod. “I understand you need a doctor.”

“Yes, but—” Wide-eyed, she stared at him. That name. What an odd coincidence. She blinked. “Mr. Crutch went for Dr. Laniere. He should be right back.”

“I sent him to bring the mule cart around for us.”

“But—I wanted the house surgeon. Where is he?”

Braddock frowned. “Dr. Laniere is conducting a surgery. Do you or do you not need a doctor?”

“I do, but—”

“Then we’d best hurry. Here’s Crutch with the cart.” He ran down the steps to the drive path, where the messenger was alighting from a small wagon pulled by a lop-eared mule.

Abigail picked up her skirts and followed. “But are you a doctor?” He was very young, perhaps in his mid-twenties.

Braddock vaulted onto the seat of the cart and took the reins from Crutch. “This is a medical college,” he said, reaching a hand down to Abigail. “I’m a second-year student, top of my class. Professor Laniere wouldn’t have sent me if he didn’t think I could deliver a baby. Come on, get in.”

Abigail stared up at him. A student? But Dr. Laniere was in surgery and Tess needed help now. She allowed young Braddock to pull her up onto the narrow seat, settling as far away from him as she dared without pitching herself onto the pavement.

“Where is the patient?” he asked, glancing at her.

“Tchapitoulas Street.”

“That’s a long street. Which part?”

“The District,” she managed, burning with humiliation. “We’re next to the saloon on the corner of Poydras.”

“I might have known.” He flapped the reins to set the cart into motion.

Abigail refused to look at him again, although the jostling of the cart forced her elbow to brush his again and again. She gritted her teeth. By the time they traversed the short distance to the tenement room she shared with Tess, her nerves were a raw jangle of anxiety, fear and resentment.

The young doctor spoke not another word to her until he stopped the cart in front of the saloon and lightly jumped down to tie the mule to a hitching post. He reached for his bag, then offered a hand to Abigail. “Perhaps you could tell me what the trouble is and who I’m to treat.”

Disdaining his hand, Abigail got down from the cart on her own. “My friend Tess has been laboring to deliver her baby all day and most of last night. She was so weak and frightened…I didn’t know what to do.”

“When did contractions start?”

Abigail hurried for the door of the tenement. “About this time yesterday.”

Braddock grabbed her arm. “She’s been in labor for twenty-four hours and you’re just now asking for help?”

“I’ve delivered babies before.” She jerked away from him. “It’s just that I’ve never encountered this difficulty.” Not for the first time she wished she’d had the opportunity for training this rich boy had. Then she’d have known what to do without incurring his disdain.

“Never mind. Which room?” They were in the tiny ground-floor entryway. Narrow unpainted doors opened to the right and left and the treads of a rickety staircase wobbled straight ahead.

“This way.” Abigail turned to the door on the right and lifted the door latch. There was no key because there was no lock. “Tess?” She entered the dark, shabby little room, frightened by the silence. She could sense the silent young doctor behind her.

A soft moan came from the shadows where Tess’s pallet lay against the wall.

Relieved, Abigail hurried over. “Tess, I’ve brought a doctor. He’s going to help us bring the baby out.”

“I can’t…I’m too tired, Abby.” Tess’s voice was a thread.

Abigail fell to her knees and laid a gentle hand on Tess’s distended belly. “Yes, you can. Dr. Braddock is going to help you.” She looked over her shoulder to find him setting his bag on the table.

He looked up. “We’ll need all the extra linens you have. You’ve a way to boil water?”

Abigail swallowed. “Of course.”

“Abigail? Abby?” Tess’s voice sounded terrified. “It’s starting again. The pain—” A scream interrupted her words, ripping from the center of her being.

Torn between compassion and the practical need to attend to the doctor’s wishes, Abigail hurried to find the pile of clean rags she’d been collecting against Tess’s lying-in. As she mended the fire she’d left burning low in the tiny cookstove that squatted against the only exterior wall of the room, she was conscious of Tess’s inhuman, wailing accompaniment to Braddock’s rather jerky movements.

He laid out a collection of shining instruments on one of the rags, arranging them with fastidious neatness. He seemed slow, reluctant.

She watched him with resentment. She should be the doctor, not him.

By the time she had a tin pot of water boiling to her satisfaction on the stovetop, Tess’s screams had subsided to whimpers. Abigail gestured for Braddock’s attention. “Now what?”

He got to his feet. “We need to let the water cool a few minutes. I want to wash my hands and instruments. Do you have lye soap?”

She frowned. “We need to hurry. She’s not going to be able to stand another contraction like that.”

Braddock scowled. “I’ll remind you that you came to me for help. Professor always washes everything.”

Abigail stared at him. If she argued with him, he would stand there until Kingdom Come, and Tess would die. Tight-lipped, she found him the soap, then knelt beside Tess to bathe her head with a cool cloth. “Hold on,” she murmured. “Just a few more minutes.”

Behind her John Braddock doused his instruments one by one in the boiling water, then returned them to the clean cloth. After removing the pot from the stove, he stood waiting for it to cool, hands in the pockets of his trousers, staring at nothing.

Abigail watched him. His body was tall and strongly built inside those fashionable clothes. He’d laid the beautiful hat on the shaky pine table, revealing a headful of wavy golden brown hair. She supposed one could call him good-looking, although her perspective on handsome men was admittedly skewed. She had yet to see him smile, but his nose was firmly arched, with fine nostrils, and the eyes wide-set and intelligent.

His brain was the most important part of his body as far as she was concerned.

Finally, just as Tess started screaming again, he decided the water was cool enough to the touch and proceeded to thoroughly soap and rinse his hands. Catching Abigail staring as he dried them, he gave her a mocking bow.

“Now, your ladyship, I’m ready.”

Chapter Two

John knelt beside his moaning patient and stared at the baby in his hands. For the first time in his life he uttered the name of God in prayer. He’d never lost a life before—at least not on his own.

He laid the stillborn infant on a ragged towel, then turned to the woman who had been quietly hovering behind him for the past two hours. He held out a shaking hand. “Give me that needle and suture.”

She handed him the implements he required, watching his every movement with vigilant, protective eyes.

He began the job of sewing up the woman’s torn body. “Here, hold this sponge.”

His provisional nurse knelt and followed his gestured instructions. “What about the baby?”

“You can bury it later. It’s more important to take care of your friend.”

Abigail gasped, dropping the sponge. “The baby’s dead? How could you let it die?” She picked up the infant and cradled it against her bodice. Her face twisted and silent sobs began to shake her thin body.

John swallowed against a surge of sympathy but kept stitching. Crying wasn’t going to bring the baby back to life. He finished the sutures, efficiently mopped the wound and sat back on his heels. He studied his patient’s chalky face. At least she was still breathing, harsh painful gasps between bloodless lips. Her eyes squeezed shut as he drew her dress down over her knees. She would live.

“Where’s her husband?” He got up to rinse his hands in a bowl of sterilized water, wiped them on the last clean towel, then opened his bag to stow his instruments.

“I’m not married.” The gritty whisper came from his patient. Grunting, she tried to sit up. “Abigail, let me see the baby.”

“Here, lie down or you’ll start the bleeding again.” John knelt to put a hand to her shoulder, which was almost as thin as the skeleton that sat in a spare chair in his boarding house bedroom.

The patient speared him with pain-clouded eyes. “I have to see him.”

“It’s—it was a girl,” John stammered. “She didn’t make it.”

“A girl. Please, let me hold her just a minute.”

John met Abigail’s eyes for an agonized moment. She looked away.

“Give it to her,” he managed.

His patient took the infant’s naked, messy little body against her own, cuddling it as if it were alive and ready to suckle.

What was a fellow supposed to do? He was no minister capable of dealing with these depths of grief. Inarticulate anger seized him as he took a deliberate look around. The tiny, shabby tenement room was scrupulously clean—apparently the lye soap had been put to use—but the odor of mildew and age infused every breath he took. This was no place for two young women to live alone, no matter what their morals.

Dr. Laniere would have known exactly how to deal with the situation. But back at the hospital, Crutch had interrupted the professor demonstrating the amputation of an infected finger for a ring of medical students. The professor had sent John, assuring him he was perfectly capable of delivering a baby.

Eagerly he’d accepted the assignment. John had always assumed he could do anything he set his mind to. But his confidence had diminished as he realized the breech presentation had left the baby in the birth canal too long.

Capable. A crack of despairing laughter escaped him. Lesson learned.

Unfortunately, there was nothing more he could do here. Snapping the latch of his bag, he turned toward the door.

He’d taken no more than a couple of steps when he found himself deluged from behind by lukewarm water. It streamed down the back of his neck, plastered his hair to his forehead and nearly strangled him as he took a startled breath.

With a choked exclamation, he turned to find Abigail glaring at him, the cracked pottery bowl held in her hands like a battle mace.

“Where do you think you’re going?” she demanded, looking as if she might fling the bowl at his head, too.

Speechless, John dropped his bag and swiped water out of his eyes with his sleeve. Intent on getting to the patient, he hadn’t properly looked at the woman who had summoned him. For the first time it dawned on him that the woman’s few words had been spoken in cultured tones, rather than the typical Creole waterfront accent. And although she was dressed in a ratty brown skirt and blouse, she had the tall, sturdy build of a warrior princess. Nobody would call this woman beautiful, but it was a face a man couldn’t forget once he’d seen it.

A furious face. Light green eyes glittered with the flame of peridots set in gold.

John found his voice. “How dare you.”

It wasn’t a question. It was his equivalent of a bowl of water dumped over the head, uttered in a drawl cultured by a lifetime spent in the elite drawing rooms of New Orleans.

“How dare I?” She bared a set of lovely white teeth, but it was not a smile. She clonked the bowl down on the table and stalked up to him. He was a tall man and her eyes were on a level with his lips. “I’ll tell you how I dare. I prayed for you. Not for Tess and the baby, but for you! I could tell you were scared spitless, you stuck-up beast.” She sucked in a breath. “You laughed.”

Stung to the heart, John sucked in a breath. Of course he hadn’t been laughing at her or Tess, but at the irony of his own impotence.

“What do you want me to do?” he said through stiff lips. He could hardly let her see his humiliation, but perhaps he could redeem himself somewhat.

The girl studied him, taken aback, as though she’d expected him to either hit her or leave without a word. “You could at least help me bury the baby.”

“I’m a doctor, not a grave digger.”

“You’re not much of a doctor, either.”

John flinched at this brutal truth. “Is there a…graveyard nearby?”

The girl shook her head. “We’re nearly underwater here. The charity burial grounds is on the north side of the city.”

Tess began to cry, clutching the child closer.

John didn’t know what to do with this slide into helplessness. Despite her derisive words, Abigail looked at him as if she expected him to do something heroic. Clearly he had a maudlin trollop, a corpse and an angry Amazon to deal with before he could go home and go to bed. And he’d been up since before dawn.

With a sigh he walked toward a rusty sink in the corner of the room and activated the pump. He stuck his head under the anemic stream of murky water, rubbed hard, and came up dripping. His coat was ruined, but that was the least of his worries at the moment. Slicking his hair back with both hands, he turned. “Abigail, wash the baby and wrap her in a blanket. We’ll take Tess to Dr. Laniere. Then I’ll send someone from the hospital to take care of the burial.”

Abigail nodded, a rather contemptuous jerk of her severely coifed brown head, but moved to obey.

John knelt beside his patient. “Where are your clean clothes?” He touched her shoulder again, aware of the awkwardness of the gesture.

Her anxious dark eyes followed Abigail’s ministrations to the child. She shook her head. “I don’t have any.”

John sat back on his heels and looked around. Other than the cookstove, a shaky three-legged table shoved next to the far wall and the two straw-filled cots, there wasn’t a stick of furniture in the room.

His sister, Lisette, had two armoires stuffed with more dresses than she could wear in a year. Her shoes lined a dressing room shelf that ran the entire length of her bedroom.

The abject poverty of these women filled him with guilt. Releasing a breath, he gathered Tess up in his arms, ignoring the blood on her skirt that soaked through his sleeve and the shabby shoes tied to her feet by bits of rope. He concentrated on rising without disturbing her sutures.

The girl let out a gasp of pain and clutched his neck.

“It’s all right, you’re all right,” he muttered.

“Be careful!” Abigail turned, clutching the blanket-wrapped bundle close. “Should I go look for help?”

The last of John’s patience fled. “Just open the door,” he said through his teeth.

Those light eyes narrowed. She gave John a mocking curtsy as he passed with Tess in his arms. “Your lordship.”

He was grateful to find the cart still tied in front of the building. Equipages had been known to disappear during calls in this part of the city, especially after dark. Thank God he had decided at the last minute to bring it. Riding would have been faster, but one never knew when a patient would have to be hauled to hospital.

Hitching her skirt nearly to mid-calf, Abigail climbed into the back of the cart with a lithe motion that gave John an unobstructed view of trim ankles and a pair of down-at-the-heels black-buttoned boots. She sank cross-legged onto the clean straw and opened her arms. “Here, lay her head in my lap.”

Swallowing a time-wasting retort, John complied. Later he would impress upon her who was in charge.

Abigail stroked Tess’s damp reddish hair off her forehead, a tender gesture at odds with her brisk, no-nonsense manner. She looked up at John, brows raised. “Let’s go.”

Scowling at her presumption, John climbed onto the narrow bench at the front of the cart and flapped the reins. With a snort the mule jerked into motion. As the cart bumped over the uneven bricks of Tchapitoulas Street, John could hear an occasional groan from his patient, accompanied by hisses of sympathy from Abigail.

“Can’t you be more careful?” she shouted over the clop of the mule’s hooves and the rattle of the cart.

He stopped, letting another wagon and several pedestrians pass, and stared at her over his shoulder. “Would you care to drive, Miss—?”

“Neal.” Darkness had nearly overtaken the waterfront, but John detected a hint of amusement in her tone. “My papa often asked my mother the same thing when I was a little girl.” All traces of levity vanished as she sighed. “Forgive me. I know we have to hurry.”

“Yes. We do.” Surprised by the apology and puzzled by an occasional odd, sing-song lilt in the girl’s cultured voice, John stared a moment longer, then turned and clicked his tongue at the mule. He would question Abigail later—after the baby was buried.

A grueling ten minutes later, the cart turned a corner onto St. Joseph Street, leaving behind the waterfront’s crowded rail depots, dilapidated shanties, cotton presses and towering warehouses. Inside the business district, two-and three-story brick buildings hovered on either side of the narrow street like overprotective mammies. Streams of green-slimed water, the result of a recent rain, rushed in the open gutters beside the undulating sidewalks. Businessmen intent on getting home after the day’s work hurried along, ignoring the stench of decayed vegetation, sewage and shellfish that permeated everything.

John frowned, unable to overlook the city squalor. He had tried to convince his father that a platform of sanitation reform would solidify his mayoral campaign. The senior Braddock preferred more socially palatable topics of debate. If all went well, John’s father would be elected in November.

If all did not go well, the pressure would be on John to quit medical school, go into the family shipping business and try for political office himself. Phillip Braddock often opined that power was a tool for good; he meant to grab as much as possible, even if it had to come through his son.

Because John had no intention of becoming anyone’s puppet, he was concentrating on getting his medical diploma and staying out of the old man’s way. As much as John admired him, his father had a great deal in common with the new steam-powered road rollers.

As he guided the cart onto Rue Baronne, he wondered what his father would have to say about these two passengers. Probably shake his leonine head and expound at length on the wages of sin.

He glanced over his shoulder again. Abigail had rested her elbow on the side of the cart and propped her head against her hand. She seemed, incredibly, to be asleep, with Tess dozing in her lap.

What set of circumstances had brought the two of them to such a pass? He saw women like them often, when he and his friends did rounds in the waterfront, but he’d never before had such a personal confrontation with a patient. Or a patient’s caregiver.

“You just passed the hospital,” Abigail said suddenly.

“I thought you were asleep.” Annoyed to have been caught daydreaming, John flipped the reins to make the mule pick up his pace. “We’re not stopping at the hospital. Dr. Laniere has a clinic and a few beds at his home. Tess will be better cared for there.”

“I see.” Abigail was quiet for the remainder of the trip.

The professor’s residence on Rue Gironde was a lovely three-story brick Greek revival, with soaring columns supporting a balcony and flanking a grand front entrance at the head of a flight of six broad, shallow brick steps. Wrought iron graced the balcony and the steps, lending a charming whimsy to the formal design of the house.

John bypassed the curve of the drive circling in front of the house and took a narrower path that passed alongside and led around to the back entrance into the kitchen and clinic. The house and grounds were as familiar to him as the home he’d grown up in. The Braddocks and the Lanieres had maintained social ties since John was a boy, despite the fact that the Lanieres’ loyalties to the Confederacy during the “late upheaval” had been in serious doubt. It was even rumored that Gabriel Laniere had been a Union spy and had fled prosecution as a traitor, leaving Mobile with his wife and a couple of body servants in tow. Phillip Braddock chose to discount such nonsense; ten years ago he had been appointed to the board of directors of the medical college, and remained one of its main financial contributors and fund-raisers.

John drew up under a white-painted portico designed more for function than elegance, which opened into a tiny waiting room off the clinic. He got out and tied the mule, then went around to reach for Tess and the baby. As he slid his arms under her back and knees, Abigail stopped him with a hand on his shoulder. An oil lantern hanging beside the door illuminated a surprising sprinkle of freckles across her formidable nose.

“Thank you for bringing us here,” she said. “You didn’t have to.”

And why had he? John studied the anxious pucker between her level brows. He frowned and straightened. “Hope Willie’s still here,” he muttered to himself. “We’ll need to send the baby to the hospital for burial preparation while we get Tess settled.” He shifted his burden and stepped back. “She needs a clean gown and I want to check her sutures after that ride.”

Abigail struggled to her feet, apparently numb from having sat in one position so long. “Who’s Willie?”

“House servant. Butler, coachman, a bit of everything.” John moved aside as Abigail swung over the side of the cart to the ground. When she appeared to be steady on her feet, he jerked his chin at the door. “Ring the bell and somebody will let us in.”

Abigail pulled the tasseled bell cord and moments later the door opened with a jerk.

“Winona.” For the hundredth time John shook his head at the waste of such exotic loveliness cooped up in a kitchen and doctor’s clinic. “Is there an empty bed in the ward?”

The Lanieres’ young housekeeper’s smooth dark brow folded in instant lines of concern. “Mr. John! What you doin’ here so late?” Clucking her tongue, Winona moved back to let him enter with his slight burden. “Of course there’s a bed. Nobody else here, in fact. Who’s this poor lady?”

She led the way out of the waiting room into the well-stocked dispensary, then into a third room. She lit a gas lamp on a plain side table. Bathed as it was in quiet shadows and antiseptic odors, the room looked inviting enough. John was glad he’d elected to come here, rather than the hospital.

“A maternity call I made late this afternoon. Breech delivery.” As Winona turned down one of the four beds with movements unhurried but efficient, John kept an eye on Abigail. She stood just inside the room, hands clenched in the folds of her skirt. She looked more than out of place. She kept looking out the window as if expecting to be followed. “This is Abigail Neal,” he said.

Winona, in her unassuming way, exchanged nods with the other woman.

“We lost the baby,” John said as he laid his burden on the smooth, clean sheet.

“Bless her heart,” Winona breathed, touching Tess’s wan face and pulling up the top sheet.

“She’ll be fine, but we need to arrange a burial in the morning.” John took the baby out of Tess’s arms. “Where’s Dr. Laniere?”

“Gone to deliver another baby.”

John winced. “Gone how long?”

“Maybe an hour. He’d just come back from the hospital and sat down to supper. Miss Camilla’s upstairs puttin’ the children to bed.”

“All right. I’ll stay until he comes back.” John glanced at Abigail, who looked like she might topple over, if not for the wall behind her. “Winona, could you fix Miss Neal a cup of tea and a biscuit or two? Maybe find her a clean dress and a nightgown for the patient?”

Winona nodded. “Was just goin’ to suggest that. Be back in a bit.” She paused in the kitchen doorway and gave Abigail a kind glance over her shoulder. “Ma’am, there’s a chair over there in the corner if you want to sit down.”

“Thank you—” But Winona had already disappeared. “What a lovely young woman.” Abigail moved the wooden straight chair close to the bed.

“Yes, and she’s a wonderful cook, too.” John had been moving about the room, but when the silence became prolonged, he looked around to find Abigail, head bent, folding pleats in her ugly skirt. “What’s the matter?”

“Nothing.”

John shrugged and moved to the window, where he stared at his reflection in the dark window. He hoped the professor would be back soon.

Chapter Three

Abigail straightened the lye-scented sheet across Tess’s shoulders and brushed the lank hair away from her face. The chair beside the cot had become most uncomfortable in the last hour, despite the pleasure of the tea and biscuits Winona had provided.

Tess, now clothed in a plain white nightgown Winona pulled from a supply closet, was finally asleep. Abigail herself had been given a faded dark blue cotton dress with elegant jet buttons marching up the front and ending at a neat white stand-up collar. She couldn’t remember ever having worn such a lovely garment.

She looked up at John Braddock. He had ceased prowling the room and now towered at the foot of the bed, holding Tess’s nameless little one close to his sharp-planed face. He had not put the baby down once since he’d picked her up. Expression somber, he brushed the waxen cheek with his knuckle, then examined her minute fingers one by one.

Abigail wondered what drove the emotions that crossed his expressive face. Was it remorse for the loss of his little patient? Did he regret his earlier condescension?

She could hardly believe some of the things she’d done and said to him in the past few hours. Up to this point, her anger at him and fear for Tess had given Abigail strength beyond herself, but something about the young doctor’s tearless grief flayed her emotions. She bent to lay her forehead beside Tess’s shoulder and let hot tears soak the sheet. She was empty. She didn’t know what to do, where to turn.

“Birth and death, all at once.”

Abigail turned her head. “What?”

“I never realized how closely tied they are. Some of us get a lot of time and some get none at all.” John lifted his gaze from the baby’s face and Abigail saw stark confusion in the heavy-lidded hazel eyes. “Do you think it’s all predetermined? Am I wasting my time?”

“I don’t know.” She sat up and scrubbed away her tears with both hands. “The baby might have been dead before you got there.” It was hard to admit that. “Tess would’ve died, too, if you hadn’t come. I was thinking—I’m not sure I could’ve carried on if she had.”

John’s face was a study in consternation. “Is she your sister?”

“No.” Abigail adjusted the sheet again and checked to make sure Tess’s breathing was still regular. “Six months ago I arrived in New Orleans with nowhere to go, no family and no friends. Tess took me in and helped me find a job.”

He stared at her and she felt her face heat. What must she look like to this educated, expensively dressed young high-brow? Even in stained and wrinkled clothing, with his thick hair falling into his eyes from a deep widow’s peak, he looked like he belonged in somebody’s parlor.

“Where did you come from?” His elegantly marked brows drew together. “You don’t look like the usual fare from the District.”

Abigail came out of her chair. “Give me that baby right now—” she tugged at the infant corpse—” and get out of here.” When he resisted, looking down at her as if she were crazy, she glared up into his multicolored eyes. “If you don’t like the way I look, go put on your smoking jacket and settle down for a beer with the fellows. Then you can laugh over us slum wenches to your heart’s content and not think about us one more second.”

The fellow refused to behave in any predictable way. He hooked his free arm around Abigail’s shoulders and yanked her close, the baby between them. “Abigail, I’m sorry.” His voice was husky, almost inaudible.

Abigail stood with her face buried in the fine, still-damp wool of John’s coat, the soft, bulky shell of a baby pressing against her bosom. Her world shifted.

How long? How long since she’d been held in the hard strength of a man’s embrace? Not since she was a small girl, before her mother left and her father became the Voice of God.

She ought to pull away from this improper embrace. Humiliating to need it so much. No more crying, though. She stood stiff, wondering what he was thinking.

“Braddock, what’s going on here?” The deep, resonant voice came from the doorway.

John Braddock let Abigail go and stepped back. “S-Sir! I’m so sorry, but I didn’t know what else to do.”

“Looked to me like you knew exactly what you were doing.”

Abigail turned, straightening her hair and smoothing her skirt in the presence of the tall, distinguished man who strode into the clinic carrying a black medical bag. His thick black hair, gray-shot on the sides, and the lines fanning out from intelligent black eyes put his age somewhere in the mid-forties, but the trim, athletic figure would have rivaled many a younger man.

Abigail glanced at John, waiting for an introduction. The younger doctor seemed to be struck dumb with mortification. She dropped a curtsy toward the professor, whose mouth had quirked with disarming humor. “Thank you for coming, Dr. Laniere. I’m Abigail Neal. I’m the one who came for you on behalf of my friend Tess.”

“Ah, yes.” Dr. Laniere’s expression sobered. “The difficult labor.” He approached Tess and bent to lay a gentle hand against her forehead, then lifted her wrist to check her pulse.

Abigail met John’s gaze. She started to speak, but he shook his head once, hard, his lips clamped together. “Prof, the baby didn’t make it.” At the professor’s inquiring look John continued doggedly. “Breech presentation kept the baby too long without oxygen. The mother was losing blood quickly, so I made the decision to save her.” His tone was firm, almost clinical, but Abigail heard the note of distress in the elegant drawl.

The young doctor’s contained anguish inexplicably drew Abigail’s sympathy. She had a crazy urge to comfort him.

Dr. Laniere steepled his fingers together, propping his forehead against their tips. For a moment the only sound in the room was Tess’s harsh breathing, then the professor dropped his hands and looked up with a sigh. He approached John to clasp his shoulder. “We’ll talk about your procedures later, Braddock.” He laid his other hand on the baby’s head, as if in benediction. “Why did you bring him here?”

Although he’d missed his guess at the swaddled infant’s sex, Abigail noted with gratitude that he didn’t call the baby “it.”

“They wanted a burial and didn’t have any place to go,” said John. “I told them you’d help us find a minister and a gravesite.”

“Did you?” Dr. Laniere sounded amused.

“Please, sir,” Abigail intervened before John’s defensiveness could spoil their advantage. “We’d be grateful if you could help us. All we can afford is the charity catacombs and I just can’t see that poor little one abandoned there.”

Dr. Laniere stood with his hand resting on Braddock’s shoulder, but he fixed Abigail with a look so full of compassion that she nearly broke down in tears again. “I understand your distress. But you know the baby is in the arms of the Father now.” He smiled slightly. “Perhaps, of all of us, the least abandoned.”

Abigail wished she could believe that.

Hope lifted the discouraged droop of John Braddock’s mouth. “That’s so, isn’t it, sir?”

“As I live and breathe in Christ.” Dr. Laniere squeezed his student’s shoulder. “Now let’s see what we can do to make your patient more comfortable and take care of the baby’s resting place.”

“You will not give her that beastly powder.” Abigail stood in the kitchen doorway, effectively preventing John’s entrance into the clinic. The professor had gone to take care of the burial arrangements, leaving the two of them to watch over Tess. “I’ve known women who never rid themselves of the craving, once they taste it.”

John showed her the harmless-looking brown bottle of morphine. “But it would ease her pain and help her sleep.”

“Yes, but if you slow her heart enough, she may not wake up at all.”

“What do you know about it?” John stiffened. “We’ll ask Dr. Laniere.”

She’d studied on her own, but hadn’t known enough to help her mother. “I know what I’ve seen—”

“John, at the risk of sounding uncivil, what are you doing here so late?”

Abigail turned.

A pretty, curly-haired young matron entered the clinic with a baby of about six months propped on her hip. She tipped her head to smile at Abigail around John’s shoulder. “I’m Camilla Laniere. Meggins, say ‘How do you do.’” She picked up the baby’s hand to wave.

John looked guilty. “I’m sorry if we disturbed you.”

“Nonsense. I was just surprised to see anyone here, that’s all.”

When the baby stuck her chubby fist in her mouth, Abigail smiled. “How do you do, young lady?”

“Afflicted by swollen gums, I’m afraid,” said Mrs. Laniere, brushing her knuckles gently across the baby’s flushed cheek. “We came down for a sliver of ice.” She paused, a question in her soft voice. “I didn’t know we had a patient in the clinic.”

Abigail brushed past John. “I’m not the patient, ma’am. My name is Abigail Neal, and my friend Tess is in the ward here. Your husband sent Mr. Braddock to us. He brought us here when—” She faltered. “Tess is very ill. She lost her baby.”

“I’m so very sorry.” Mrs. Laniere reached to clasp Abigail’s hand. She glanced at John, heading off his clear intention to continue the opium debate. “You did well to bring them here, John. What have you done with my husband?”

John blinked, reverting to some instinctive standard of manners. “He’s taking care of laying out the—the body. He sent Willie to find a couple of grave diggers.”

“Ah. Then I assume we’ll have the burial in the morning.”

“Yes, ma’am, before church.” He hesitated. “Because the professor will be back soon, I believe I’ll leave the patient in his hands. She’s resting fairly comfortably now. I’ve a pharmacy test to study for.” He pressed the vial of morphine into Abigail’s hand. “You can trust Dr. Laniere to do the right thing.”

“I’m sure I can.” Pocketing the opiate, Abigail gave him a dismissive nod. “Good evening, Mr. Braddock.”

“Good evening, Miss Neal.”

When he closed the door behind him with a distinct thump, Meg flinched and snuggled her face into her mother’s neck.

Shaking her head, Mrs. Laniere hugged the baby. “Please overlook John’s abruptness. He’s…a bit tense these days.”

“I suppose I should have thanked him.” Abigail leaned against the table, rubbing her aching temple. “Does he think he knows everything?”

“I’m afraid it’s rather characteristic of the genus homo.” Mrs. Laniere smiled. “But John in particular, being considered brilliant in his field, tends to be a bit…insistent in expressing his opinions.”

Abigail laughed. “That’s one way to put it.”

“You must be worried about your friend.” Mrs. Laniere hesitated, swaying with the baby. “My dear, would you care to sit down with me for a cup of tea?”

“I couldn’t impose. Tess—”

“—is resting. We’ll be near enough to hear her if she calls. And I’d like a bit of intelligent female conversation while I nurse the baby.”

Abigail studied Camilla Laniere’s frank, friendly face. There seemed to be no ulterior motive. She smiled faintly. “I’d adore a cup of tea, Mrs. Laniere.”

“Please. Camilla. I’m not that much older than you.”

The doctor’s wife led the way into the kitchen, then unceremoniously handed the baby over to Abigail and began tea preparations. Despite her itchy gums, Meg seemed remarkably placid. Giving a contented sigh, she popped her thumb in her mouth and laid her head on Abigail’s shoulder.

After a startled downward glance, Abigail smiled and patted her charge’s cushioned bottom. Leaning against the dough box, she watched Camilla’s familiar movements around the roomy, well-equipped kitchen. “Where did the servants go?”

“Winona and Willie are our only house servants.” Camilla measured tea into a lovely floral china teapot. “They both go home on Saturday evenings to be with their families on the Lord’s Day.”

“I suppose we interrupted your family time tonight, but I was so grateful when your husband arrived—”

“My dear, you mustn’t apologize.” Camilla set the kettle on the stove to boil and smiled over her shoulder. “Gabriel is always glad to be of service. I would have been down here myself if I hadn’t been putting the children to bed.”

As Abigail stared into Camilla’s golden-brown eyes, something flashed between them—an intuition of friendship, an offer of human connection. Abigail looked away, hardly able to bear this sudden kindness.

After a moment Camilla quietly took the baby, leaving Abigail empty-handed and feeling foolish. “I think you need a place to stay tonight. To be with your friend.” She laughed as Abigail shook her head. “I’m being utterly selfish, you know. Winona and Willie won’t be back until tomorrow evening. If our patient needs something, you’d be here for her.”

“All right.” Abigail returned the smile. “I’ll stay. And of course you must call me Abigail. ‘Miss Neal’ ran away many years ago and hasn’t been heard from since.” Touching the baby’s pink foot, she looked up from under her lashes. “Besides, I have to make sure the Barbarian doesn’t try to feed opium to Tess.”

Feeling a soft little hand patting her cheek, Abigail struggled out of deep sleep into utter darkness.

“Winona! Winona, wake up, I’m thirsty!” lisped the small, invisible person behind the hand. “It’s hot and Mama’s rocking the baby and I can’t sleep.”

Abigail suddenly remembered where she was. Winona’s little room off the clinic, just a few steps from Tess’s bed in the ward. This must be one of the Laniere children.

She sat up. “I’m not Winona, I’m Abigail. But I’ll get you a drink of water—just a minute, let me light a candle.”

“Ooh! Just like Goldilocks! What’re you doing in Winona’s bed?”

Abigail laughed. “Winona will be back tomorrow.” Swinging her legs off the side of the bed, she lit the candle and held it up so she could see the wide, bespectacled eyes of a little boy who looked like his mother—probably around seven years old, judging by the missing front teeth. His hair curled in every direction but down and his nightgown was buttoned two buttons off, so that the hem hitched crookedly around his knees.

He poked his spectacles up on his button nose with one finger. “You ain’t Goldilocks. Your hair’s brown.”

Abigail tugged the braid hanging over her shoulder, wishing for a proper nightcap. “It is indeed. What’s your name?”

“Diron. Are you gonna get me a drink or not?”

Since Camilla had thoughtfully provided a pitcher of clean water and a cup for her guest before retiring, Abigail smiled and poured a drink for the boy. Diron downed it quickly and held out the cup for more. It was then that she noted the small red blister on the child’s forehead.

“Just a minute.” She reached out to push back the bright curls. His forehead was warm.

Enduring her touch with a long-suffering frown, Diron scratched his stomach.

“How long have you been itching?” she asked.

“I dunno. I must’ve got a bunch of mosquito bites. Can I please have some more water?”

“Certainly. But I want to see your tummy.”

She poured the water, then while he drank it, matter-of-factly unbuttoned his nightgown. His chest and upper abdomen were covered with the tiny red blisters. Chicken pox.

No wonder the poor child was so hot and thirsty. Camilla was busy with the baby, but she would want to know.

When Diron finished his water, Abigail took him by the hand and led him into the clinic and through the kitchen. The sound of both of their bare feet slapping against the wooden floors tickled her sense of humor and she enjoyed the feel of his small warm hand in hers. He was a trusting little fellow.

In the carpeted hallway she saw the stairs to the upper floors. It was a large, airy house, bigger than anything Abigail had been inside before, with lots of screened windows and light, gauzy curtains stirred by a cool nighttime breeze.

On the first landing she felt Diron tug her hand. “Miss Lady. I’m tired.” He gave an enormous yawn.

“Would you like a piggy-back ride?” He nodded and she walked down a few steps to let him climb on. “Goodness, you’re a big boy.” She grunted as he clutched her around the neck and waist. “Hold tight now.”

As Abigail trudged up the remaining steps to the first floor, Diron leaned around. “Where’d you get that funny accent?”

“China,” she replied without thinking.

“Oh, pooh. I didn’t believe you was Goldilocks, neither.”

Chapter Four

A chill had sneaked across the river during the night, sending fog drifting across the graveyard, twining through Abigail’s hair and muting her and Dr. Laniere’s footsteps. The ground was soft, even on this elevated patch a mile or so away from the river, and she had to step over puddles of water in the shallow hollows of sunken graves.

Abigail carried the baby, dressed in a tiny white gown worn by Meg just a few months ago. Camilla would have attended the funeral service, but she’d had to remain with the feverish and itchy Diron. Tess was induced to remain in bed only by Abigail’s promise of writing down exactly what was said at her baby’s interment.

They were to call her Caroline.

“Here we are,” said Dr. Laniere, halting beside a tiny fresh grave, barely three feet long and a couple of feet wide. He opened the lid of the small wooden casket he’d carried from the house and looked across the top of it at Abigail. “It’s time to put her in the casket.” His deep-set dark eyes were somber, filled with sympathy. “Remember—”

“I know. She’s with the Father.” Abigail closed her mind against the instinct to pray. She’d been brought up to talk to God at every turn and the habit kicked in at moments of stress. But it was difficult to believe God was really interested in either her or this small wasted life.

Placing the baby in the box, she arranged the lacy white skirts in graceful folds. She was glad Tess couldn’t see this. She could remember Caroline cuddled in her arms like a white-capped doll.

Dr. Laniere placed the lid on the box and was about to lower it into the grave when pounding footsteps approached.

“Wait!” John Braddock ran out of the mist, panting. In one hand he carried his black medical bag. “Professor, I want to see her again before you bury her.”

Dr. Laniere straightened.

Abigail hadn’t expected the young doctor to actually come for the burial. She was even more surprised that he’d apparently already been on a medical call. “What are you doing here?” she blurted, sounding perhaps more defensive than she’d intended.

“I’ve a right to be here,” he said breathlessly. “I delivered this baby, and—” He swallowed. “Let me see her, please.”

When the professor opened the box, Braddock removed his hat, clutching it as he stared at the baby. “I’m so sorry,” he muttered. “I promise I’ll learn to do better.”

Abigail’s throat closed. She didn’t want to like this privileged rich boy. Pressing her lips together, she looked away.

She heard the lid go back on the box and then the gritty sound of wood landing on sand and clay. The two men picked up the shovels left by the grave diggers and began to fill in the small hole in the ground.

The job took less than a minute. She made herself look at the mound of fresh dirt, the only visible trace of Tess’s baby—except the scars on her friend’s body. She thought of her father’s pontifications on Scripture. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust. The Lord cherishing the death of his beloved.

She couldn’t find anything particularly precious about this stark moment.

“Oh, God, we know you’re here.” Dr. Laniere lifted his resonant voice. “We know you give and you take away and you are sovereign. We pray you’ll remind us of your presence even in the darkness of grief. We pray you’ll be ever near to Tess as she recovers. Please champion these young women and help them find real help as they seek you. Please use Camilla and the children and me to meet their needs. And I pray you’ll hear and meet young Braddock’s desire to be a healer, even as you heal his heart.”

What about my desire to be a healer? Abigail thought as the professor paused. What about my wounded heart? She opened her eyes and looked up just as a ray of sunshine broke through the patchy fog. An enormous rainbow soared from one end of the graveyard to the other. She caught her breath.

“In the name of our Lord, who takes our ashes and turns them to joy…Amen.”

The professor and John replaced their hats. Abigail, shivering in the cool morning dampness, hurried toward the cemetery entrance. She wanted to get back to Tess, to write down the words of the service before she forgot them. Ashes to joy…

“Wait, Abigail.” Shifting his medical bag to the other hand, John caught up with her, took her hand and pulled it through his elbow. “I thought you should know I went back to the District last night.”

“Did you?” Stumbling on the soggy, uneven ground, she reluctantly accepted the support of his arm. “Needed a bit of alcoholic sustenance?”

“No, I—” He gave her an exasperated look. “Must you assume the worst?”

She shrugged. “I don’t know many men who lead me to expect anything else.”

“Well, in this case you’re wrong. I went back there because I’d heard a child coughing in the apartment next to yours. The walls are so thin—”

“Yes, they are.” She didn’t need to be reminded. “That would be the McLachlin baby. He has chronic croup. I’ve tried to get Rose to move him out of that mildewy apartment, but she can’t afford anything better.”

“Well, I went back to see about him. Stupid woman wouldn’t let me in, even though I told her I was a doctor.”

Abigail looked up at him. “To the contrary. For once she was using her head, not letting a strange man into her apartment.”

There was a brief silence. “I see your point.” John opened the graveyard gate and held it as Abigail passed through. “Then perhaps you’d agree to return with me this afternoon and persuade her of my good intentions. I’d like to look at the baby to see if anything can be done about that cough.”

Abigail hesitated. “She can’t afford to pay you.”

“I know that.” He let out an exasperated sigh. “Prof encourages us to see charity cases when we have time. It’s good practice.”

“Oh, well, then. For the sake of your education, I suppose I’d best come with you.”

He stiffened. “Miss Neal—”

“Mr. Braddock.” She squeezed his elbow. “I was only tweaking you.”

He looked at her for a moment before a slow grin curled his mouth. “Were you, indeed? Then for the sake of your education, I’ll allow you to observe a man who practices medicine for more than money. Perhaps you might learn something.”

His eyes held hers. Something shifted between them. Abigail looked over her shoulder to find the professor’s reassuring presence several paces back.

John followed her gaze. “Prof, I’m going back to Tchapitoulas Street with Miss Neal to look after a sick little boy.”

“Fine. Just bring her back before noon and you may stay for dinner, too.” Dr. Laniere waved them on and turned off toward Daubigny Street, where his family attended church.

For the next couple of blocks, Abigail maintained a tense silence. In the distance church bells began to ring. “Are you a church-going man, Mr. Braddock? Perhaps your family will wonder where you are.”

“My family would be quite astonished to see me at all on Sunday before late afternoon,” he said easily. “I don’t live at home.”

“Oh.” When he didn’t elaborate, she looked at him. “Then a wife or—or sweetheart?”

“I assure you I am quite unattached at the moment. Are you trying to get rid of me?”

“Of course not.” Abigail looked away, blushing, as they turned the corner at the saloon. “I agreed to come with you to check on the baby.” Her relief that he was unattached was absurd. There was nothing personal whatsoever in his escort.

“Yes, you did. And here we are.” He stood back as Abigail opened the outer front door and knocked on the door across the entryway from her old apartment with Tess.

She could hear the baby crying inside, Rose’s anxious voice, the other two children giggling and shrieking. “Rose?” She knocked again. “It’s Abigail.”

The door jerked open and Rose appeared with the baby on her hip. A little girl and a little boy of about four and five clung to her skirts, one on each side. “Abigail—what are you doing here? Is something wrong?”

Abigail glanced at John over her shoulder. “I brought Dr. Braddock with me. He wants to look at Paddy.”

Rose’s big blue eyes widened. “Paddy’s fine.”

Abigail laid a hand on the baby’s back and felt the rattle of his lungs as he breathed. He’d tucked his face into Rose’s shoulder, but Abigail could just see the curve of a feverish cheek. “Rose. Please let us in. Denying trouble never made it go away.”

Rose stared at John, one hand clasping the baby, the other protectively on her daughter’s head. Abigail knew she must be thinking of the drunken husband who had brought her and the children over from Ireland and abandoned them two months ago. As she’d told John earlier, Abigail herself had little reason to rely on any man’s trustworthiness. But some tiny part of her insisted on giving this one a chance to prove himself.

John seemed to realize he was here on sufferance. “Mrs. McLachlin, I think I know what’s causing Paddy’s cough. If you’ll just let me look at him for a minute, I can give him some medicine and he’ll feel much better tonight.” His tone was, if not exactly humble, moderate enough to reassure.

Baby Paddy suddenly erupted in one of his fits of croupy coughing. Rose took a flustered step back. “All right. Come in, both of you, but don’t look at the mess. The children have been playing all morning.”

Abigail would not have increased Rose’s embarrassment for the world, but she couldn’t help marveling that the young Irishwoman had survived this long on a laundress’s wage with three small children. Clearly she was in dire straights. Except for two dolls made from bits of yarn and a pile of rusty tin cans the children had been playing with in the center of the room, there was little difference between this apartment and the one Abigail had shared with Tess. Poverty had a way of leveling the ground.

To her surprise, as she and Rose seated themselves on the two wooden chairs, John took off his hat, sat down cross-legged on the floor and opened his bag. He produced a couple of splinters of peppermint candy wrapped in waxed paper and smiled at the two older children, who stared at him from behind Rose’s chair. “Look what I’ve got here, widgets. I’ll give it to you, but you have to open your mouths wide and let me see if there’s room for it to go in.”

The little girl, Stella, glanced at her brother. “It’s candy,” she whispered.

“I want it,” he whispered back. The first to conquer his shyness, he edged toward John, who held the candy just out of reach. Apparently seduced by the twinkle in John’s eyes, he dropped his jaw and stuck out his tongue. “’ee? ’ere’s ’oom.”

John laughed and deftly plied a tongue depressor as he peered down the little boy’s throat. “There is, indeed. Here you go.” He laid the candy on the boy’s tongue. “What’s your name?”

“Sean.” The boy danced backward, eliminating any chance of the candy being snatched away. His eyes closed in ecstasy. “Marmee, I like this.”

“Me! Me!” Stella gaped wide as she crowded close to John, gagging slightly as he depressed her tongue. But she patiently held still to let him look at her throat. When she received her candy, she sucked on it furiously, gazing at John with adoration. “Can Paddy have some too?”

John shook his head. “Paddy’s too little. But maybe he’d let me look at his throat anyway?”

By this time, Rose was thoroughly disarmed and handed over the baby without further protest. John took him with a gentle competence that reminded Abigail of the way he’d held poor little Caroline that morning. Her throat closed as Paddy blinked up at the doctor’s handsome young face.

John examined the baby thoroughly, laying his ear against Paddy’s chest and back to listen, gently moving his arms and legs, palpating the glands beneath the soft little chin. He tracked the movement of Paddy’s eyes by moving his finger back and forth, grinning when the baby grabbed it and tried to suck on it. “No, no, boo. Dirty.” He looked at Rose as he lifted Paddy onto his shoulder and patted his back. “Definitely teething, which causes fever. But the cough worries me. It means there’s mucus draining into his stomach, maybe collecting fluid in his lungs. You’ll need to suction out as much of it as you can, keep him at a comfortable temperature, wash everything that goes in his mouth. Keep him fed—which means taking care of yourself.” His eyes softened as he looked around at the bare room. “Do you get enough to eat?”

Distress took over Rose’s worn young face. “I do the best I can, but there aren’t many vegetables available this time of year, and meat…” She swallowed. “I can’t afford—”

“Fish,” Abigail blurted. “Tess and I used to go to the docks early in the morning and ask for whatever wasn’t quite good enough to send to the market. You can make stews and gumbo, rich in good stuff.”

Rose blinked back tears. “Maybe I could ask Tess to bring back extra…in return for laundry service.”

Abigail exchanged a smile with John. “I’m sure she’d be happy to when she’s back on her feet.”

John handed the baby back to his mother and began to repack his bag. “Yes, that’s a good idea. And meantime, wrapping the baby up and taking him outside for cool night air will ease his breathing and help him sleep. Just be sure he doesn’t get too cold.”

Rose stood up and swayed with Paddy clasped to her bosom. “Dr. Braddock, thank you for coming back. I shouldn’t have been rude to you last night.” She hesitated as John rose and dusted the seat of his trousers. “I’m sorry I can’t…I don’t have the money to pay you for your trouble.”

He stared at her, a hint of the old arrogance drawing his brows together. Or perhaps, Abigail thought, it was simple embarrassment. “I don’t need your money,” he said.

“Then perhaps you’d care to bring your laundry by.” Rose’s soft chin went up. “I’m considered the best in the neighborhood.”

Catching Abigail’s warning look, John shrugged. “I’ve no doubt you are. We’ll see. But I promised to return Miss Neal to the clinic before noon, so we’d best hurry. I or one of the other fellows will stop by here tomorrow to check on Paddy. I’ll send some bleach to wipe down the floors and ceiling. Some say that keeps down the spread of croup.” He gave Rose a quick nod and offered his hand to little Sean. “Help your marmee out by playing quietly when the baby’s asleep, won’t you, old man?”

Sean nudged his sister. “Would you bring more candy when you come back?”

John winked. “I’ll see what I can do.”

“Goodbye, Rose.” Abigail smiled at her neighbor as she followed John out to the entryway. “Don’t forget about the fish.”

“Thank you, Abigail.” Rose’s expression was considerably less troubled than when they’d first arrived. “I don’t know what else to—just thank you.” She shut the door hurriedly.

As they began the long walk back to the Lanieres’, Abigail took John’s proffered arm and sighed. “She’ll listen to you, I think.” She glanced at him. “You were very sweet to the children.”

She knew she’d used the wrong word when his fine eyes narrowed. “Perhaps you’d expected me to growl at them.”

Smiling, she shrugged. “You did surprise me a bit. I confess your motivations confuse me, John. People like Rose—and Tess and me, for that matter—cannot pay you in coin, and you seem to have a rather contemptuous attitude toward our entire class. Why do you want to be a doctor? Is it simple scientific hunger?”

He didn’t immediately answer. “Imperfections bother me,” he said slowly. “I suppose that could be considered a character flaw. But I see no reason for those little ones to suffer from hunger and disease if there’s anything I can do about it.” He glanced at her, cheeks reddened, she thought not entirely from the wind whipping off the river. “I don’t mean to be arrogant.”

An inappropriate urge to giggle made Abigail look down, pretending to watch her step. “Because imperfections annoy me as well, I’ll take it upon myself to correct you as needed.” She gave him a mischievous glance from under her lashes.

To his credit, John laughed. “Magnanimous of you, Miss Abigail. You’ll give me lessons in social intercourse, and I’ll keep your considerable predisposition for interference well occupied. We should get along famously.”

Almost lightheaded with the unexpected pleasure of intelligent repartee with an attractive—if slightly prickly—male, Abigail turned the conversation to his background with the Laniere family. John Braddock was like no man she’d met in her admittedly abnormal life. Perhaps she had more to learn than she’d thought.

“It’s got to be here somewhere,” John muttered to himself that evening as he skimmed through the last of six pharmaceutical books he’d borrowed from Marcus Girard. He sat on his unmade bed, his back propped against the wall, a cup of stout Creole coffee wobbling atop the tomes stacked at his elbow.

The cramped and exceedingly messy fifteen-by-fifteen-foot room on the second level of Mrs. Hanley’s Boarding House for Gentlemen was one of John’s greatest sources of personal satisfaction. It hadn’t been easy to endure his mother’s tearful accusations of ingratitude nor his father’s blustering threats of disinheritance. But in the end, John’s determination to live on his own had worn them both down. Two years ago, on his twenty-third birthday, he had packed his clothes and books into four sturdy trunks and had them carted to the boarding house. He then rode his black mare, Belladonna, to the livery stable around the corner on Rue St. John—another serendipitous circumstance which afforded him no end of amusement.

Mrs. Clementine Hanley insisted on absolute moral purity in her lodgers—the enforcing of which she took quite seriously and personally. She also set a fine table and could be counted upon to provide fresh linens daily.

Unfortunately, she was not so dependable in the matter of functioning locks.

John looked up in irritation when the doorknob rattled. The key worked its way loose and hit the floor with a clank. “Girard, if you come in here again, I’m going to souse every pair of drawers you own in kerosene and set them on fire.”

The door opened anyway and Marcus’s ingenuous, square-cut face insinuated itself in the opening.

John glared. “Go away!”

Marcus leaned over to pick up the fallen key and tossed it at John. The key plunked into the half-full coffee cup. “Oops.” He gave John an unrepentant grin. “A little iron supplement for your diet, old man.”

Snarling under his breath, John used his pillow case to mop up the sloshed coffee. “You’d better have a good reason for interrupting me again.” He fished the key out of his cup.

Marcus swaggered into the room with his usual banty-rooster strut, hands thrust into the enormous pockets of a peacock-blue satin dressing gown. He paused in front of the skeleton spraddled in a straight chair under the room’s tiny, solitary window.

“Hank, old bean.” Marcus bowed, sketching a salute. “I trust this evening finds you hale and hearty.”

John resisted the urge to laugh. Encouraged, Marcus could go on for hours in that oily false-British accent. He closed the book on his finger. “What do you want, Girard?”

“Stuck-up rotter, ain’t you?” Giving the skeleton a thump on the cranium, Marcus hopped onto the window sill and folded his arms across his barrel chest. “Came to rescue you.”

“Rescue me? The only way you can rescue me is to find me another pharmacy book.”

“Braddock, I’ve lifted every book m’father has on the subject. If what you’re looking for ain’t there, it just—ain’t there. Come on, I know you’ve memorized the lists for the test. Let’s toddle over to the District and slum a little.”

The notorious red light district was located a few blocks from the medical college and Mrs. Hanley’s Boarding House. It also happened to be where John had encountered Tess and Abigail. Yesterday’s experience had destroyed whatever appeal the District once had. And going back with Abigail this morning to visit the McLachlin family had turned it rather into a source of conscience.

John opened the book again. “I’m busy. And if you had even half as many brains as Hank, you’d take one of these books down to your room and have a look yourself.”

Marcus gave John a puzzled look. “What’s got into you today? You didn’t go to church this morning, did you?”

John gave a bark of laughter. “Not exactly. I attended a funeral.”

Marcus sat up straight, his thin, sandy hair all but on end. “I’m sorry, Braddock! Who died?”

“Nobody you know.” John had no intention of exposing the life-changing experiences of the last two days to Marcus’s inanities. “I’m just—not in the mood. Comprendez-vous?”

Marcus pursed his lips. It was common knowledge that John’s family ties took him in directions that less well-connected students could only dream of. “Certainly. I understand. Death and all that.” He slid off the window seat and sidled toward the door. “You were my first choice of companion, but I guess I’ll head down to Weichmann’s room to see if he’d care to get his head out of the books for a bit.” He paused with his hand on the doorknob. “If Clem asks, tell her we’ve gone on a call.”

Mrs. Hanley would certainly ask, should John be so foolish as to stick his nose outside the room. He gave Marcus an absent wave as the brilliantly hued dressing gown disappeared into the hallway. There had better be no emergency calls tonight.

He took a sip of the stone-cold coffee, then propped the cup on his chest, dropping the book onto the floor. He’d been studying the composition and medicinal uses of opium for hours and there was still no conclusive evidence that Abigail Neal was wrong. It was true that opium and all its derivatives—including morphine and laudanum—could be addictive when consumed even once. Certainly the substance was effective as a painkiller, but were the side effects worth it?

John didn’t know. He was discovering there were a lot of things he didn’t know. The more he studied medicine, the more he realized its practice was largely in the realm of guesswork, intuition and trial and error. Frequently even mysticism. Even Dr. Laniere, his favorite professor and mentor, sometimes made fatal judgments. He had as good a record of success as any physician John had yet to meet, but…people did die under his care.

Why didn’t God just tell people how to go on? Why did they get ill and injured in the first place? If he could heal at all, why didn’t he heal everybody?

Irritated at the intrusion of such unscientific thoughts, John slung his coffee cup onto the bedside table and got up off the bed. He took a deep breath and bent to touch his toes a few times.

He’d been entertaining a lot of God-related meanderings ever since the delivery of that stillborn baby. All day he’d had a sense of someone looking into his mind, prodding his thoughts and feelings. One of the main reasons he’d taken Abigail back to visit that croupy baby was to escape the strong urge to go to church.

Just a bit spooked, he turned a full circle, taking in his familiar surroundings. Nothing out of order. The narrow, tumbled bed with the coffee stain on the pillow. The square table holding a pile of anatomy textbooks and the Tiffany lamp his mother had given him on his twenty-first birthday. Sepia-toned photographs of his parents and her sister Lisette on the mantel above the tiny fireplace. Hank holding court in the chair under the window. The plain mahogany chifforobe with its mirror reflecting his confusion back at him.

John thrust both hands through his hair and stared at his own reddened eyes. Not enough sleep lately. That was all it was.

Then he looked at his hands. They shook. The nails were immaculate, the signet ring on his left little finger dull gold with a garnet set into the family crest. Rich man’s hands? Healer’s hands?

He hurried to the window, leaned out and sucked in a draft of thick, clammy, November air. He’d lived in New Orleans all his life and the humidity had never bothered him before, but he found himself struggling for a breath. No wonder little Paddy McLachlin was so sick.

John looked down, watching passersby fading in and out of the pools of gaslight spotting the sidewalks. When had it gotten dark out? Maybe he should try to catch up to Girard and Weichmann after all.

He pulled his head back inside the room, banged down the window sash and yanked the curtain closed. He sat down to tug on his boots, decided against a coat and tore out of the room, slamming the door behind him. He pounded down the stairs, shoving the useless key into his pocket.

God couldn’t influence his thoughts if he wasn’t there.

Chapter Five

The next morning John slumped at a table in a nearly empty classroom, listening to the heavy marching of the clock on the wall behind him. Traffic clamored from the street outside the open window to his left.

He stared at the test in front of him and wondered which of the medicines he’d just listed would be the quickest remedy for acute hangover. Maybe he should go straight for the arsenic. Quelling a strong desire to hang his head out the window and heave, he contemplated the top of Dr. Girard’s bald head, visible behind the Monday morning Daily Picayune.

Marcus’s father was a cold-hearted old goat, a brilliant lecturer whose written tests had been known to reduce grown men to tears. He sat at the front of the lecture hall, behind a bare table which exposed his short legs, stretched out and crossed at the ankle. His scarlet-and-lemon-striped waistcoat, half-inch-thick watch chain and green paisley ascot revealed the source of Marcus’s love for sartorial splendor.

John wished the professor had his son’s amiable temperament.

He was one of only two students left in the room. Everyone else, including Marcus himself, had either completed the test or given up in despair. He glanced across the room at Tanner Weichmann. Weichmann had not indulged in spirits last night, but had come along more or less to keep Marcus out of trouble. In fact, it had been he who put both Marcus and John to bed, after paying for a hack home and supporting the two of them up the narrow stairs. Good thing Clem slept like the dead or they might all have been out on the street tonight.

John supposed he should be grateful not to have awoken in a gutter somewhere, robbed of his clothes and money. Weichmann was a serious pain, but he was dependable. Perhaps not as gifted a scientist as John, not nearly as much fun as Marcus, but methodical to the point of insanity. John was certain he’d finished the test long ago, but Weichmann would check his answers to make sure every word was spelled correctly and all sentences complete.

Weichmann suddenly looked up, his dark eyes probing John’s. He wiggled heavy black brows and elaborately pulled out his watch.

John couldn’t resist looking over his shoulder at the clock. Nearly noon. Time was almost up. He suppressed a groan, bent over his paper again and dredged up the therapeutic and alterative uses of mercury. By the time he finished his answer, Dr. Girard had folded his paper in a neat square and waited, stubby fingers linked and his brow creased in impatient lines. John looked around. Weichmann had disappeared.

“Braddock, you seem determined to make me miss my noon meal,” growled Dr. Girard. “Are you quite finished?”

“Yes, sir. Sorry, sir.” John rose and clattered down the steps of the amphitheater, sticking his pencil stub behind his ear. He reluctantly handed over his paper. “When will you have them graded?” If he failed this test he would have to repeat the course. Pharmaceuticals tended to be his downfall because of the spellings.

Without looking at him, the professor stuffed John’s test into a leather portfolio. “You’ll know soon enough.” He rolled out of the room without a backward glance.

John ran a hand around the back of his neck, popping the joints to relieve tension. At least it was over. Pass or fail, there was nothing he could do about it now. He needed to go lie down.

He headed for the door and nearly jumped out of his skin when someone grabbed his arm as he passed into the hallway.

“How did you do, Braddock?”

John wheeled. “Careful, Weichmann, or you’ll be cleaning your shoes. I’m still a bit unsteady this morning.”

Weichmann gave an evil chuckle. “Speaking of morning, you missed rounds. Prof wasn’t happy.”

Dr. Laniere wasn’t the only professor, of course, but every med student distinguished him with the title. No one wanted to disappoint Professor Laniere.

John lifted a shoulder and continued down the hall toward the stairs. “Couldn’t be helped. What did you tell him?”

“Told him you had a previous engagement.”

“You did not.”

“No. But I should have. Braddock, you never drink. What’s gotten into you, old man?”

Since the words were almost a direct quote of Marcus’s the day before, John hurried down the marble stairs without replying. He wasn’t going to admit that a prostitute’s dead baby had resulted in his hearing from God.

Weichmann’s long, skinny legs had no trouble keeping up. “There’s a few minutes for lunch before anatomy lab. Want to go for a beignet and coffee?”

John’s stomach revolted. “No!”

“Oh, sorry…Didn’t think.”

John sat down and planted his elbows on his knees, laying his pounding head in his palms. He could feel Weichmann hovering behind him on the stairs, his breath wheezing and whistling. It took little to get the young Jew’s asthma kicked up.

“No, I’m sorry. I don’t know what’s wrong with me.” John stared at the gray squiggles in the white marble between his feet. “Weichmann, has God ever communicated with you? You know, like Moses and the burning bush?”