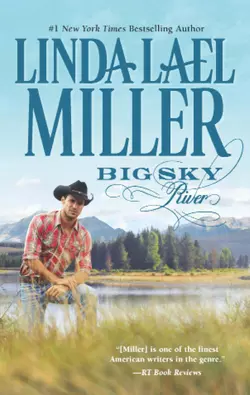

Big Sky River

Linda Lael Miller

The "First Lady of the West," #1 New York Times bestselling author Linda Lael Miller brings you to Parable, Montana—where love awaits.Sheriff Boone Taylor has his job, friends, a run-down but decent ranch, two faithful dogs, and a good horse. He doesn’t want romance—the widowed Montanan has loved and lost enough for a lifetime. But when a city woman buys the spread next door, Boone’s peace and quiet are in serious jeopardy.With a marriage and career painfully behind her, Tara Kendall is determined to start over in Parable. Reinventing herself, living a girlhood dream, is worth the hard work. Sure, she might need help from her handsome, wary neighbor. But life along Big Sky River is full of surprises . . . like falling for a cowboy-lawman who just might start to believe in second chances.

The “First Lady of the West,” #1 New York Times bestselling author Linda Lael Miller, brings you to Parable, Montana—where love awaits.

Sheriff Boone Taylor has his job, friends, a run-down but decent ranch, two faithful dogs and a good horse. He doesn’t want romance—the widowed Montanan has loved and lost enough for a lifetime. But when a city woman buys the spread next door, Boone’s peace and quiet are in serious jeopardy.

With a marriage and a career painfully behind her, Tara Kendall is determined to start over in Parable. Reinventing herself and living a girlhood dream is worth the hard work. Sure, she might need help from her handsome, wary neighbor. But life along Big Sky River is full of surprises…like falling for a cowboy-lawman who just might start to believe in second chances.

Dear Reader,

Welcome to Parable, Montana, and the third story in my Big Sky series!

Sheriff Boone Taylor has been staying under the radar, doing his job but letting the rest of his life slide—much to the annoyance of his neighbor, cosmetics executive turned chicken farmer Tara Kendall. When she looks out over her otherwise lovely view of the countryside, her eyes invariably find the “eyesore” Boone calls home.

Now, suddenly, children arrive on the doorstep—Boone’s two little boys, who have been living with his sister since soon after his wife Corrie’s death, and the twin preteen stepdaughters Tara loves and constantly misses, since her ex-husband allows her little or no time with them.

Big Sky River is a book about two wonderful, heart-bruised people who have nearly stopped believing in love, even though it’s all around them, like the mountains and rivers and famed Big Sky, finding their way to each other and pooling their broken dreams to make a new one together—the kind that lasts.

So here’s a hearty welcome to Parable, whether you’ve been here before or this is your first visit. Sit back, join in and be prepared to smile—and maybe even shed a tear or two.

You’re going to like it here.

Best,

Praise for the novels of #1 New York Times bestselling author Linda Lael Miller

“Miller’s name is synonymous with the finest in western romance.”

—RT Book Reviews

“This is a delightful addition to Miller’s Big Sky series. This author has a way with a phrase that is nigh-on poetic, and all of the snappy little interactions between the main and secondary characters make this story especially entertaining.”

—RT Book Reviews on Big Sky Mountain

“Miller’s down-home, easy-to-read style keeps the plot moving, and she includes…likable characters, picturesque descriptions and some very sweet pets.”

—Publishers Weekly on Big Sky Country

“After reading this book your heart will be so full of Christmas cheer you’ll want to stuff a copy in the stocking of every romance fan you know!”

—USATODAY.com Happy Ever After on A Lawman’s Christmas

“Miller once again tells a memorable tale.”

—RT Book Reviews on A Creed in Stone Creek

“A passionate love too long denied drives the action in this multifaceted, emotionally rich reunion story that overflows with breathtaking sexual chemistry.”

—Library Journal on McKettricks of Texas: Tate

“Miller’s prose is smart, and her tough Eastwoodian cowboy cuts a sharp, unexpectedly funny figure in a classroom full of rambunctious frontier kids.”

—Publishers Weekly on The Man from Stone Creek

“Strong characterization and a vivid Western setting make for a fine historical romance.”

—Publishers Weekly on McKettrick’s Choice

Big Sky River

Linda Lael Miller

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

For Sadie—third time’s the charm, sweet dog.

Send me another just like you.

Contents

Chapter One (#u771cfe59-53ef-5a03-9d22-291b609c5c4f)

Chapter Two (#u975cf06b-5d23-5ebf-931a-17fc8a7ca733)

Chapter Three (#u1b77ca03-5b60-5171-a2c1-fa1cfc120b82)

Chapter Four (#u13de6a6e-2cc5-5919-94bc-0dc3736981c8)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Excerpt from Big Sky Country (#litres_trial_promo)

Excerpt from Big Sky Mountain (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE

SHERIFF BOONE TAYLOR, enjoying a rare off-duty day, drew back his battered fishing rod and cast the fly-hook far out over the rushing, sun-spangled waters of Big Sky River. It ran the width of Parable County, Montana, that river, curving alongside the town of Parable itself like the crook of an elbow. Then it extended westward through the middle of the neighboring community of Three Trees and from there straight on to the Pacific.

He didn’t just love this wild, sprawling country, he reflected with quiet contentment. He was Montana, from the wide sky arching overhead to the rocky ground under the well-worn soles of his boots. That scenery was, to his mind, his soul made visible.

A nibble at the hook, far out in the river, followed by a fierce breaking-away, told Boone he’d snagged—and already lost—a good-sized fish. He smiled—he’d have released the catch anyway, since there were plenty of trout in his cracker-box-sized freezer—and reeled in his line to make sure the hook was still there. He found that it wasn’t, tied on a new one. For him, fishing was a form of meditation, a rare luxury in his busy life, a peaceful and quiet time that offered solace and soothed the many bruised and broken places inside him, while shoring up the strong ones.

He cast out his line again, and adjusted the brim of his baseball cap so it blocked some of the midmorning glare blazing in his eyes. He’d forgotten his sunglasses back at the house—if that junk heap of a double-wide trailer could be called a “house”—and he wasn’t inclined to backtrack to fetch them.

So he squinted, and toughed it out. For Boone, toughing things out was a way of life.

When his cell phone jangled in the pocket of his lightweight cotton shirt, worn unbuttoned over an old T-shirt, he muttered under his breath, grappling for the device. He’d have preferred to ignore it and stay inaccessible for a little while longer. As sheriff, though, he didn’t have that option. He was basically on call, 24/7, like it or not.

He checked the number, recognized it as Molly’s, and frowned slightly as he pressed the answer bar. She and her husband, Bob, had been raising Boone’s two young sons, Griffin and Fletcher, since the dark days following the death of their mother and Boone’s wife, Corrie, a few years before. A call from his only sibling was usually benign—Molly kept him up-to-date on how the boys were doing—but there was always the possibility that the news was bad, that something had happened to one or both of them. Boone had reason to be paranoid, after all he’d been through, and when it came to his kids, he definitely was.

“Molly?” he barked into the receiver. “What’s up?”

“Hello, Boone,” Molly replied, and sure enough, there was a dampness to her response, as though she’d been crying, or was about to, anyhow. And she sounded bone weary, too. She sniffled and put him out of his misery, at least temporarily. “The boys are both fine,” she said. “It’s about Bob. He broke his right knee this morning—on the golf course, of all places—and the docs in Emergency say he’ll need surgery right away. Maybe even a total replacement.”

“Are you crying?” Boone asked, his tone verging on a challenge as he processed the flow of information she’d just let loose. He hated it when women cried, especially ones he happened to love, and couldn’t help out in any real way.

“Yes,” Molly answered, rallying a little. “I am. After the surgery comes rehab, and then more recovery—weeks and weeks of it.”

Boone didn’t even reel in his line; he just dropped the pole on the rocky bank of the river and watched with a certain detached interest as it began to bounce around, an indication that he’d gotten another bite. “Molly, I’m sorry,” he murmured.

Bob was the love of Molly’s life, the father of their three children, and a backup dad to Griff and Fletch, as well. Things were going to be rough for him and for the rest of the family, and there wasn’t a damn thing Boone could do to make it better.

“Talk to me, Molly,” he urged gruffly, when she didn’t reply right away. He could envision her, struggling to put on a brave front, as clearly as if they’d been standing in the same room.

The pole was being pulled into the river by then; he stepped on it to keep it from going in and fumbled to cut the line with his pocketknife while Molly was still regathering her composure, keeping the phone pinned between his shoulder and his ear so his hands stayed free. Except for the boys and her and Bob’s kids, Molly was all the blood kin Boone had left, and he owed her everything.

“It’s—” Molly paused, drew a shaky breath “—it’s just that the kids have summer jobs, and I’m going to have my hands full taking care of Bob....”

Belatedly, the implications sank in. Molly couldn’t be expected to look after her husband and Griffin and Fletcher, too. She was telling her thickheaded brother, as gently as she could, that he had to step up now, and raise his own kids. The prospect filled him with a tangled combination of exuberance and pure terror.

Boone pulled himself together, silently acknowledged that the situation could have been a lot worse. Bob’s injury was bad, no getting around it, but he could be fixed. He wasn’t seriously ill, the way Corrie had been.

Visions of his late wife, wasted and fragile after a long and doomed battle with breast cancer, unfurled in his mind like scenes from a very sad movie.

“Okay,” he managed to say. “I’ll be there as soon as I can. Are you at home, or at the hospital?”

“Hospital,” Molly answered, almost in a whisper. “I’ll probably be back at the house before you get here, though.”

Boone nodded in response, then spoke. “Hang on, sis,” he said. “I’m as good as on my way.”

“Griffin and Fletcher don’t know yet,” she told him quickly. “About what’s happened to Bob, I mean, or that you’ll be coming to take them back to Parable with you. They’re with the neighbor, Mrs. Mills. I want to be there when they find out, Boone.”

Translation: If you get to the boys before I do, don’t say anything about what’s going on. You’ll probably bungle it.

“Good idea,” Boone conceded, smiling a little. Molly was still the same bossy big sister she’d always been—thank God.

Molly sucked in another breath, sounded calmer when she went on, though she had to be truly shaken up. “I know this is all pretty sudden—”

“I’ll deal with it,” Boone said, picking up the fishing pole, reeling in the severed line and starting toward his truck, a rusted-out beater parked up the bank a ways, alongside a dirt road. He knew he ought to replace the rig, but most of the time he drove a squad car, and, besides, he hated the idea of going into debt.

“See you soon,” Molly said, and Boone knew even without seeing her that she was tearing up again.

Boone was breathless from the steep climb by the time he reached the road and his truck, even though he was in good physical shape. His palm sweated where he gripped the cell phone, and he tossed the fishing pole into the back of the pickup with the other hand. It clattered against the corrugated metal. “Soon,” he confirmed.

They said their goodbyes, and the call ended.

By then, reality was connecting the dots to form an image in his brain, one of spending a whole summer, if not longer, with two little boys who basically regarded him as an acquaintance rather than a father. And it was a natural reaction on their part; he’d essentially abdicated his parental role after Corrie had died, packing off the kids—small and baffled—to Missoula to stay with Molly and Bob and their older cousins. In the beginning, Boone had meant for the arrangement to be temporary—all of them had—but one thing led to another, and pretty soon, the distance between him and the children became emotional as well as physical. While his closest friends had been needling him to man up and bring Griffin and Fletcher home practically since the day after Corrie’s funeral, and he missed those boys with an ache that resembled the insistent, pulsing throb of a bad tooth, he’d always told himself he needed just a little more time. Just until after the election, and then until he’d gotten into the swing of a new job, since being sheriff was a lot more demanding than being a deputy, like before, then until he could replace the double-wide with a decent house.

Until, until, until.

Now, it was put up or shut up. Molly would need all her personal resources, physical, spiritual and emotional, to steer Bob and her own children through the weeks ahead.

He sat there in the truck for a few moments, with the engine running and the phone still in his hand, picturing the long and winding highway between Parable and Missoula, and finally speed-dialed his best friend, Hutch Carmody.

“Yo, Sheriff Taylor,” Hutch greeted him cheerfully. “What can I do you out of?”

Married to his longtime love, the former Kendra Shepherd, with a five-year-old stepdaughter, Madison, and a new baby due to join the outfit in a month or so, Hutch seemed to be in a nonstop good mood these days.

It was probably the regular sex, Boone figured, too distracted to be envious but still subliminally aware that he’d been living like a monk since Corrie had died. “I need to borrow a rig,” he said straight out. “I’ve got to get to Missoula quick, and this old pile of scrap metal might not make it there and back.”

Hutch got serious, right here, right now. “Sure,” he said. “What’s going on? Are the kids okay?”

Though they’d only visited Parable a few times since they’d gone to live with Molly and Bob, Griffin and Fletcher looked up to Hutch, probably wished he was their dad, instead of Boone. “The boys are fine,” Boone answered. “But Molly just called, and she says Bob blew a knee on the golf course and he’s about to have surgery. Obviously, she’s got all she can do to look after her own crew right now, so I’m on my way up there to bring the kids home with me.”

Hutch swore in a mild exclamation of sympathy for the world of hurt he figured Bob was in, and then said, “I’m sorry to hear that—about Bob, I mean. Want me to come along, ride shotgun and maybe provide a little moral support?”

“I appreciate the offer, Hutch,” Boone replied, sincerely grateful for the man’s no-nonsense, unshakable friendship. “But I think I need some alone-time with the kids, so I can try to explain what’s happening on the drive back from Missoula.”

Griffin was seven years old and Fletcher was only five. Boone could “explain” until he was blue in the face, but they weren’t going to understand why they were suddenly being jerked out of the only home and the only family they really knew. Griffin, being a little older, remembered his mother vaguely, remembered when the four of them had been a unit. The younger boy, Fletcher, had no memories of Corrie, though, and certainly didn’t regard Boone as his dad. It was Bob who’d raised him and his brother, taken them to T-ball games, to the dentist, to Sunday school.

“Not a problem,” Hutch agreed readily. “The truck is gassed up and ready to roll. Do you want me to drop it off at your place? One of the hands could follow me over in another rig and—”

“I’ll stop by the ranch and pick it up instead,” Boone broke in, not wanting to put his friend to any more trouble than he already had. “See you in about fifteen minutes.”

“Okay,” Hutch responded, sighing the word, and the call was over.

Boone stayed a hair under the speed limit, though just barely, the whole way to the Carmody ranch, called Whisper Creek, where he found Hutch waiting beside the fancy extended-cab truck he’d purchased the year before, when he and Kendra were falling in love for the second time. Or maybe just realizing that they’d never actually fallen out of it in the first place.

Now, Hutch was hatless, with his head tilted a little to one side the way he did when he was pondering some enigma, and his hands were wedged backward into the hip pockets of his worn jeans. Kendra, a breathtakingly beautiful blonde, stood beside him, pregnant into the next county.

“Have you had anything to eat?” Kendra called to Boone, the instant he’d stopped his pickup. Dust roiled around her from under the truck’s wheels, but she was a rancher’s wife now, and unfazed by the small stuff.

Boone got out of the truck and walked toward them. He kissed Kendra’s cheek and tried to smile, though he couldn’t quite bring it off. “What is it with women and food?” he asked. “A man could be lying flat as a squashed penny on the railroad track, and some female would come along first thing, wanting to feed him something.”

Hutch chuckled at that, but the quiet concern in his gaze made Boone’s throat pull tight like the top of an old-time tobacco sack. “It’s a long stretch to Missoula,” Hutch observed, quietly affable. “You might get hungry along the way.”

“I’ll make sandwiches,” Kendra said, and turned to duck-waddle toward the ranch house. Compared with Boone’s double-wide, the place looked like a palace, with its clapboard siding and shining windows, and for the first time in his life, Boone wished he had a fine house like that to bring his children home to.

“Don’t—” Boone protested, but it was too late. Kendra was already opening the screen door, stepping into the kitchen beyond.

“Let her build you a lunch, Boone,” Hutch urged, his voice as quiet as his manner. Since the wedding, he’d been downright Zen-like. “She’ll be quick about it, and she wants to help whatever way she can. We all do.”

Boone nodded, cleared his throat, looked away. Hutch’s dog, a black mutt named Leviticus, trotted over to nose Boone’s hand, his way of saying howdy. Kendra’s golden retriever, Daisy, was there, too, watchful and wagging her tail.

Boone ruffled both dogs’ ears, straightened, looked Hutch in the eye again. Neither of them spoke, but it didn’t matter, because they’d been friends for so long that words weren’t always necessary.

Boone was worried about bringing the boys back to his place for anything longer than a holiday weekend, and Hutch knew that. He clearly cared and sympathized, but at the same time, he was pleased. There was no need to give voice to the obvious.

Kendra returned almost right away, moving pretty quickly for somebody who could be accused of smuggling pumpkins. She carried a bulging brown paper bag in one hand, holding it out to Boone when she got close enough. “Turkey on rye,” she said. “With pickles. I threw in a couple of hard-boiled eggs and an apple, too.”

He took the bag, muttered his thanks, climbed into Hutch’s truck and reached through the open window to hand over the keys to the rust-bucket he’d driven up in. Some swap that was, he thought ruefully. His old buddy was definitely getting the shitty end of this stick.

“Give Molly and Bob our best!” Kendra called after him, as Boone started up the engine and shifted into Reverse. “If there’s anything we can do—”

Boone cut her off with a nod, raised a hand in farewell and drove away.

After a brief stop in Parable, to get some cash from an ATM, he’d keep the pedal to the metal all the way to Missoula. Once there, he and Molly would explain things, together.

God only knew how his sons would take the news—they were always tentative and quiet on visits to Parable, like exiles to a strange new planet, and visibly relieved when it was time to go back to the city.

One thing at a time, Boone reminded himself.

* * *

TARA KENDALL STOOD in front of her chicken coop, surrounded by dozens of cackling hens, and second-guessed her decision to leave a high-paying, megaglamorous job in New York and reinvent herself, Green Acres–style, for roughly the three thousandth time since she’d set foot in Parable, Montana, a couple years before.

She missed her small circle of friends back East, and her twelve-year-old twin stepdaughters, Elle and Erin. She also missed things, like sidewalk cafés and quirky shops, Yellow Cab taxis and shady benches in Central Park, along with elements that were harder to define, like the special energy of the place, the pure purpose flowing through the crowded streets like some unseen river.

She did not, however, miss the stress of trying to keep her career going in the midst of a major economic downturn, with her ex-husband, Dr. James Lennox, constantly complaining that she’d stolen his daughters’ love from him when they divorced, along with a chunk of his investments and real estate assets.

Tara didn’t regret the settlement terms for a moment—she’d forked over plenty of her own money during their rocky marriage, helping to get James’s private practice off the ground after he left the staff of a major clinic to go out on his own—and as for the twins’ affection, she’d gotten that by being there for Elle and Erin, as their father so often hadn’t, not by scheming against James or undermining him to his children.

Even if Tara had wanted to do something as reprehensible as coming between James and the twins, there wouldn’t have been any need, because the girls were formidably bright. They’d figured out things for themselves—their father’s serial affairs included. Since he’d never seemed to have time for them, they’d naturally been resentful when they found out, quite by accident, that their dad had bent his busy schedule numerous times to take various girlfriends on romantic weekend getaways.

Tara’s golden retriever, Lucy, napping on the shady porch that ran the full length of Tara’s farmhouse, raised her head, ears perked. In the next instant, the cordless receiver for the inside phone rang on the wicker table set between two colorfully cushioned rocking chairs.

Hurrying up the front steps, Tara grabbed the phone and said, “Hello?”

“Do you ever answer your cell?” her former husband demanded tersely.

“It’s charging,” Tara said calmly. James loved to argue—maybe he should have become a lawyer instead of a doctor—and Tara loved to deprive him of the satisfaction of getting a rise out of her. Then, as another possibility dawned on her, she suppressed a gasp. “Elle and Erin are all right, aren’t they?”

James remained irritable. “Oh, they’re fine,” he said scathingly. “They’ve just chased off the fourth nanny in three weeks, and the agency refuses to send anyone else.”

Tara bit back a smile, thinking of the mischievous pair. They were pranksters, and they got into plenty of trouble, but they were good kids, too, tenderhearted and generous. “At twelve, they’re probably getting too old for nannies,” she ventured. James never called to chat, hadn’t done that even when they were married, standing in the same room or lying in the same bed. No, Dr. Lennox always had an agenda, and she was getting a flicker of what it might be this time.

“Surely you’re not suggesting that I let them run wild, all day every day, for the whole summer, while I’m in the office, or in surgery?” James’s voice still had an edge to it, but there was an undercurrent of something else—desperation, maybe. Possibly even panic.

“Of course not,” Tara replied, plunking down in one of the porch rocking chairs, Lucy curling up at her feet. “Day camp might be an option, if you want to keep them busy, or you could hire a companion—”

“Day camp would mean delivering my daughters somewhere every morning and picking them up again every afternoon, and I don’t have time for that, Tara.” There it was again, the note of patient sarcasm, the tone that seemed to imply that her IQ was somewhere in the single digits and sure to plunge even lower. “I’m a busy man.”

Too busy to care for your own children, Tara thought but, of course, didn’t say. “What do you want?” she asked instead.

He huffed out a breath, evidently offended by her blunt question. “If that attitude isn’t typical of you, I don’t know what is—”

“James,” Tara broke in. “You want something. You wouldn’t call if you didn’t. Cut to the chase and tell me what that something is, please.”

He sighed in a long-suffering way. Poor, misunderstood James. Always so put-upon, a victim of his own nobility. “I’ve met someone,” he said.

Now there’s a news flash, Tara thought. James was always meeting someone—a female someone, of course. And he was sure that each new mistress was The One, his destiny, harbinger of a love that had been written in the stars instants after the Big Bang.

“Her name is Bethany,” he went on, sounding uncharacteristically meek all of a sudden. James was a gifted surgeon with a high success rate; modesty was not in his nature. “She’s special.”

Tara refrained from comment. She and James were divorced, and she quite frankly didn’t care whom he dated, “special” or not. She did care very much, however, about Elle and Erin, and the fact that they always came last with James, after the career and the golf tournaments and the girlfriend du jour. Their own mother, James’s first wife, Susan, had contracted a bacterial infection when they were just toddlers, and died suddenly. It was Tara who had rocked the little girls to sleep, told them stories, bandaged their skinned elbows and knees—to the twins, she was Mom, even in her current absentee status.

“Are you still there?” James asked, and the edge was back in his voice. He even ventured a note of condescension.

“I’m here,” Tara said, after swallowing hard, and waited. Lucy sat up, rested her muzzle on Tara’s blue-jeaned thigh, and watched her mistress’s face for cues.

“The girls are doing everything they can to run Bethany off,” James said, after a few beats of anxious silence. “We need some—some space, Bethany and I, I mean—just the two of us, without—”

“Without your children getting underfoot,” Tara finished for him after a long pause descended, leaving his sentence unfinished, but she kept her tone moderate. By then she knew for sure why James had called, and she already wanted to blurt out a yes, not to please him, but because she’d missed Elle and Erin so badly for so long. Losing daily contact with them had been like a rupture of the soul.

James let the remark pass, which was as unlike him as asking for help or giving some hapless intern, or wife, the benefit of a doubt. “I was thinking—well—that you might enjoy a visit from the twins. School’s out until fall, and a few weeks in the country—maybe even a month or two—would probably be good for them.”

Tara sat up very straight, all but holding her breath. She had no parental rights whatsoever where James’s children were concerned; he’d reminded her of that often enough.

“A visit?” she dared. The notion filled her with two giant and diametrically opposed emotions—on the one hand, she was fairly bursting with joy. On the other, she couldn’t help thinking of the desolation she’d feel when Elle and Erin returned to their father, as they inevitably would. Coping with the loss, for the second time, would be difficult and painful.

“Yes.” James stopped, cleared his throat. “You’ll do it? You’ll let the twins come out there for a while?”

“I’d like that,” Tara said carefully. She was afraid to show too much enthusiasm, even now, when she knew she had the upper hand, because showing her love for the kids was dangerous with James. He was jealous of their devotion to her, and he’d always enjoyed bursting her bubbles, even when they were newlyweds and ostensibly still happy. “When would they arrive?”

“I was thinking I could put them on a plane tomorrow,” James admitted. He was back in the role of supplicant, and Tara could tell he hated it. All the more reason to be cautious—there would be a backlash, in five minutes or five years. “Would that work for you?”

Tara’s heartbeat picked up speed, and she laid the splayed fingers of her free hand to her chest, gripping the phone very tightly in the other. “Tomorrow?”

“Is that too soon?” James sounded vaguely disapproving. Of course he’d made himself the hero of the piece, at least in his own mind. The self-sacrificing father thinking only of his daughters’ highest good.

What a load of bull.

Not that she could afford to point that out.

“No,” Tara said, perhaps too quickly. “No, tomorrow would be fine. Elle and Erin can fly into Missoula, and I’ll be there waiting to pick them up.”

“Excellent,” James said, with obvious relief. Not “thank you.” Not “I knew I could count on you.” Just “Excellent,” brisk praise for doing the right thing—which was always whatever he wanted at the moment.

That was when Elle and Erin erupted into loud cheers in the background, and the sound made Tara’s eyes burn and brought a lump of happy anticipation to her throat. “Text me the details,” she said to James, trying not to sound too pleased, still not completely certain the whole thing wasn’t a setup of some kind, calculated to raise her hopes and then dash them to bits.

“I will,” James promised, trying in vain to shush the girls, who were now whooping like a war party dancing around a campfire and gathering momentum. “And, Tara? Thanks.”

Thanks.

There it was. Would wonders never cease?

Tara couldn’t remember the last time James had thanked her for anything. Even while they were still married, still in love, before things had gone permanently sour between them, he’d been more inclined to criticize than appreciate her.

Back then, it seemed she was always five pounds too heavy, or her hair was too long, or too short, or she was too ambitious, or too lazy.

Tara put the brakes on that train of thought, since it led nowhere. “You’re welcome,” she said, carefully cool.

“Well, then,” James said, clearly at a loss now that he’d gotten his way, fresh out of chitchat. “I’ll text the information to your cell as soon as I’ve booked the flights.”

“Great,” Tara said. She was about to ask to speak to the girls when James abruptly disconnected.

The call was over.

Of course Tara could have dialed the penthouse number, and chatted with Elle and Erin, who probably would have pounced on the phone, but she’d be seeing them in person the next day, and the three of them would have plenty of time to catch up.

Besides, she had things to do—starting with a shower and a change of clothes, so she could head into town to stock up on the kinds of things kids ate, like cold cereal and milk, along with those they tended to resist, like fresh vegetables.

She needed to get the spare room aired out, put sheets on the unmade twin beds, outfit the guest bathroom with soap and shampoo, toothbrushes and paste, in case they forgot to pack those things, tissues and extra toilet paper.

Lucy followed her into the house, wagging her plumy tail. Something was up, and like any self-respecting dog, she was game for whatever might happen next.

The inside of the farmhouse was cool, because there were fans blowing and most of the blinds were drawn against the brightest part of the day. The effect had been faintly gloomy, before James’s call.

How quickly things could change, though.

After tomorrow, Tara was thinking, she and Lucy wouldn’t be alone in the spacious old house—the twins would fill the place with noise and laughter and music, along with duffel bags and backpacks and vivid descriptions of the horrors wrought by the last few nannies in a long line of post-divorce babysitters, housekeepers and even a butler or two.

She smiled as she and Lucy bounded up the creaky staircase to the second floor, along the hallway to her bedroom. Most of the house was still under renovation, but this room was finished, having been a priority. White lace curtains graced the tall windows, and the huge “garden” tub was set into the gleaming plank floor, directly across from the fireplace.

The closet had been a small bedroom when Tara had purchased the farm, but she’d had it transformed into every woman’s dream storage area soon after moving in, to contain her big-city wardrobe and vast collection of shoes. It was silly, really, keeping all these supersophisticated clothes when the social scene in Parable called for little more than jeans and sweaters in winter and jeans and tank tops the rest of the time, but, like her books and vintage record albums, Tara hadn’t been able to give them up.

Parting with Elle and Erin had been sacrifice enough to last a lifetime—she’d forced herself to leave them, and New York, in the hope that they’d be able to move on, and for the sake of her own sanity. Now, they were coming to Parable, to stay with her, and she was filled with frightened joy.

She selected a red print sundress and white sandals from the closet and passed up the tub for the room just beyond, where the shower stall and the other fixtures were housed.

Lucy padded after her in a casual, just-us-girls way, and sat down on a fluffy rug to wait out this most curious of human endeavors, a shower, her yellow-gold head tilted to one side in an attitude of patient amazement.

Minutes later, Tara was out of the shower, toweling herself dry and putting on her clothes. She gave her long brown hair a quick brushing, caught it up at the back of her head with a plastic squeeze clip and jammed her feet into the sandals. Her makeup consisted of a swipe of lip gloss and a light coat of mascara.

Lucy trailed after her as she crossed the wider expanse of her bedroom and paused at one particular window, for reasons she couldn’t have explained, to look over at Boone Taylor’s place just across the field and a narrow finger of Big Sky River.

She sighed, shook her head. The view would have been perfect if it wasn’t for that ugly old trailer of Boone’s, and the overgrown yard surrounding it. At least the toilet-turned-planter and other examples of extreme bad taste were gone, removed the summer before with some help from Hutch Carmody and several of his ranch hands, but that had been the extent of the sheriff’s home improvement campaign, it seemed.

She turned away, refusing to succumb to irritation. The girls were as good as on their way. Soon, she’d be able to see them, hug them, laugh with them.

“Come on, Lucy,” she said. “Let’s head for town.”

Downstairs, she took her cell phone off the charger, and she and the dog stepped out onto the back porch, walked toward the detached garage where she kept her sporty red Mercedes, purchased, like the farm itself, on a whimsical and reckless what-the-hell burst of impulse, and hoisted up the door manually.

Fresh doubt assailed her as she squinted at the car.

It was a two-seater, after all, completely unsuitable for hauling herself, two children and a golden retriever from place to place.

“Yikes,” she said, as something of an afterthought, frowning a little as she opened the passenger-side door of the low-slung vehicle so Lucy could jump in. Before she rounded the front end and slid behind the steering wheel, Tara was thumbing the keypad in a familiar sequence.

Her friend answered with a melodic, “Hello.”

“Joslyn?” Tara said. “I think I need to borrow a car.”

CHAPTER TWO

LIKE TRAFFIC LIGHTS, ATMs were few and far between in Parable, which was why Boone figured he shouldn’t have been surprised to run into his snarky—if undeniably hot—neighbor, Tara Kendall, right outside Cattleman’s First National Bank. He was just turning away from the machine, traveling cash in hand, his mind already in Missoula with his boys and the others, when Tara whipped her jazzy sports car into the space next to his borrowed truck. She wore a dress the same cherry-red as her ride, and her golden retriever, a littermate to Kendra’s dog, Daisy, rode beside her, seat belt in place.

Tara’s smile was as blindingly bright as the ones in those ads for tooth-whitening strips—she’d probably recognized the big extended-cab pickup he was driving as belonging to Hutch and Kendra, and expected to meet up with one or both of them—but the dazzle faded quickly when she realized that this was a case of mistaken identity.

Her expression said it all. No Hutch, no Kendra. Just the backwoods redneck sheriff who wrecked her view of the countryside with his double-wide trailer and all-around lack of DIY motivation.

The top was down on the sports car and Boone could see that, like its mistress, the dog was wearing sunglasses, probably expensive ones, a fact that struck Boone as just too damn cute to be endured. Didn’t the woman know this was Montana, not L.A. or New York?

Getting out of the spiffy roadster, Tara let her shades slip down off the bridge of her perfect little nose and looked him over in one long, dismissive sweep of her gold-flecked blue eyes, moving from his baseball cap to the ratty old boots on his feet.

“Casual day at the office, Sheriff?” she asked, singsonging the words.

Boone set his hands on his hips and leveled his gaze at her, pleased to see a pinkish flush blossom under those model-perfect cheekbones of hers. He and Tara had gotten off on the wrong foot when she had moved onto the land adjoining his, and she’d made it plain, right from the get-go, that she considered him a hopeless hick, a prime candidate for a fifteen-minute segment on The Jerry Springer Show. She’d come right out and said his place was an eyesore—in the kindest possible way, of course.

In his opinion, Tara was not only a city slicker, out of touch with ordinary reality, but a snob to boot. Too bad she had that perfect body and that head of shiny hair. Without those, it would have been easier to dislike her.

“Hello to you, too, neighbor,” Boone said, in a dry drawl when he was darned good and ready to speak up. “How about this weather?”

She frowned at him, making a production of ferreting through her shoulder bag and bringing out her wallet. Behind her, in the passenger seat, the dog yawned without displacing its aviator glasses, as though bored. The lenses were mirrored.

“If you’re finished at the machine—?” Tara said, with a little rolling motion of one manicured hand. For a chicken rancher, she was stylin’.

Boone stepped aside to let her pass. “You shouldn’t do that, you know,” he heard himself telling her. It wasn’t as if she’d welcome any advice from him, after all, no matter how good it might be.

“Do what?” She had the faintest sprinkling of freckles across her nose, he noticed, oddly disconcerted by the discovery.

“Get your wallet out between the car and the ATM,” Boone answered, in sheriff mode even if he was dressed like a homeless person. He was in a hurry to get to Missoula, that was all. Hadn’t wanted to take the time to change clothes. “It’s not safe.”

Tara paused and, sunglasses jammed up into her bangs now, batted her thick lashes at him in a mockery of naïveté. “Surely nothing bad could happen with the sheriff of all Parable County right here to protect me,” she replied, going all sugary. She had the ATM card out of her wallet by then, and looked ready to muscle past him to get to the electronic wonder set into the bank’s brick wall.

“Have it your way,” Boone said tersely. Why wasn’t he back in Hutch’s flashy truck by now, headed out of town? He wanted to see his boys, do what he could do for Molly and her three kids, maybe stop by the hospital and find out how Bob was holding up. But it was as if roots had poked right through the bottoms of his boots and the layer of concrete beneath them to break ground, wind down deep, and finally twist themselves into a hell of a tangle, and that pissed him off more than Tara’s snooty attitude ever had.

“Thank you,” she said, a little less sweetly, brushing by him and shoving her bank card into the slot before jabbing at a sequence of buttons on the number pad. “I will.”

Boone rolled his eyes. Sighed. “People get robbed at ATMs all the time,” he pointed out, chafing under the self-imposed delay. It would take a couple hours to reach Missoula, who knew how long to sort things out and load up the kids, and then two more hours to make it home again. And that was if they didn’t stop along the way for supper.

Tara took the card out of the machine, collected a stack of bills from the appropriate opening, and started the process all over again. Who needed that much cash?

Maybe it was a habit from living in New York.

Her back—and a fine little back it was, partly bared by that skimpy sundress of hers—was turned to him the whole time, and she smelled like sun-dried laundry and wildflowers. “In Parable?” she retorted. “Who would dare to commit a crime in your town, Boone Taylor?”

He waited until she’d completed the second transaction and turned around, nearly bumping into him. She was waving all those twenties around like the host on some TV game show, just asking for trouble. “I do my best,” he told her, enjoying the flash of flustered annoyance that lit her eyes and pulsed in her cheeks, “but Parable isn’t immune to crime, and there are some risks nobody but a damn fool will take.”

She arched her eyebrows, shoved her sunglasses back into place with an eloquent gesture of the middle finger on her right hand. “Are you calling me a damn fool?” she asked, in a tone about as companionable as a room full of pissed-off porcupines.

“No,” Boone said evenly. I’m calling you a spoiled city girl with a very high opinion of yourself, he thought but didn’t say. “I’m only suggesting that you might want to be a little more careful in the future, that’s all. Like I said before, Parable is a good town, but strangers do pass through here, in broad daylight as well as after dark, and we might even have a few closet outlaws in our midst.”

Tara blinked up at him. “Are you through?” she asked politely.

He spread his hands and smirked a little, deliberately. “I tried,” he said. He could have added, “Don’t come crying to me if you get mugged,” but of course she’d have every right to do just that, since he was the law.

She went around him, sort of stalked back toward her car. It was amusing to watch the slight sway of her hips under that gauzy dress as she moved.

“Thanks so much,” she said tersely, opening the driver’s side door and plunking down behind the wheel. Only then did she bother to stick the cash in her wallet and drop that back into her bag.

The dog looked from her to Boone with the casual interest of a spectator at a slow tennis match.

Boone swept off his baseball cap and bowed deeply. “Anytime, your ladyship,” he said.

Tara pursed her lips, looked back over one satin-smooth shoulder to make sure no one was behind her, and ground the car’s transmission into Reverse. Her mouth was moving, but he couldn’t hear what she said over the roar of the engine, which was probably just as well.

It would serve her right, though, he thought, if he cited her for reckless driving. He didn’t have the time—or a case, for that matter—but he savored the fantasy as he got back into Hutch’s truck.

* * *

BOONE TAYLOR WAS just plain irritating, Tara thought, as she and Lucy drove away from the bank. Unfortunately, he was also a certified hunk with the infuriating ability to wake up all five of her senses and a few she hadn’t discovered yet. How did he do that?

She stayed on a low simmer all the time she was running errands—buying groceries, taking them home and putting them all away, filling the pantry and the fridge and part of the freezer. Boone had disrupted her whole afternoon, and wasn’t that just perfect, when she should have been enjoying the anticipation of her stepdaughters’ arrival?

To sustain her momentum, she prepared the guest quarters, scrubbing down the clean but dusty bathroom, opening the windows, vacuuming and fluffing pillows and cushions, swapping out the sheets, even though the first ones hadn’t been slept in. Tara hadn’t had company in a while, and she wanted the linens to be clothesline-fresh for the twins.

Throughout this flurry of activity, Lucy stayed right with her, supervising from the threshold, occasionally giving a little yip of encouragement or swishing her tail back and forth.

“Everything is done,” Tara told the dog when it was, straightening after smoothing each of the white chenille bedspreads one final time and glancing at the little clock on the nightstand between them. “And it isn’t even time to feed the chickens.”

Lucy uttered a conversational little whine, keeping up her end of the conversation.

Tara thought about her family-unfriendly car again, and Joslyn’s generous offer to lend her the clunky station wagon her housekeeper, Opal, shared with Shea, Joslyn and her husband Slade’s eighteen-year-old stepdaughter.

Borrowing the vehicle would be too much of an imposition, she decided, as she and Lucy headed down to the kitchen via the back staircase. It was time to head over to Three Trees, cruise past both auto dealerships, and pick out a big-girl car. Something practical, like a minivan or a four-door sedan, spacious but easy on gas.

Within minutes, she and Lucy were back on the road, this time with the car’s top up so they wouldn’t arrive all windblown, like a pair of bad credit risks.

* * *

MOLLY AND BOB lived in a modest two-story colonial on a shady side street in the best part of Missoula. The grass in the yard was greener than green and neatly trimmed, possibly with fingernail scissors. Flowers grew everywhere, in riotous tumbles of color, and the picket fence was so pristinely white that it looked as if the paint might still be wet.

Boone stopped the truck in front, and though not usually into comparisons since he wasn’t the materialistic type, he couldn’t help being struck by the contrast between his sister’s place and his own.

He sighed and shoved open the driver’s side door, keys in hand. He’d been wishing he’d taken the time to shower and put on something besides fishing clothes ever since the run-in with Tara Kendall outside the bank in Parable, if only to prove to the world in general that he did his laundry and even ironed a shirt once in a while. Now, faced with the obvious differences, he felt like a seedy drifter, lacking only a cardboard begging sign to complete the look.

The screen door opened and Molly stepped out onto the porch, waving and offering up a trembling little smile. Her long, dark hair was pulled back into a messy ponytail, and she wore jeans, one of Bob’s shirts and a pair of sneakers that looked a little the worse for wear. Mom-shoes.

“Bob’s been admitted,” she said right away, coming down the porch steps and meeting him at the front gate, opening the latch before Boone could reach for it. “He’s getting a new knee in the morning.”

“Maybe I’ll stop by and say hello to him on the way out of town,” Boone offered, feeling clumsy.

“He’s pretty out of it,” Molly answered. “The pain was bad.”

Boone put a hand on his sister’s shoulder, leaned in to kiss her forehead lightly. “What happened, anyhow?” he asked. Bob was the athletic type, strong and active.

Molly winced a little, remembering. “One of the regulars brought his nephew along today—he’s never played before—but he has one heck of a backswing. Caught Bob square in the knee.”

Now it was Boone who winced. “Owww,” he said.

“Owww, indeed,” Molly verified. “The nephew feels terrible, of course.”

“He should,” Boone said.

That was when Molly made a little sound of frustration and worry, and hugged him close, and Boone hugged her back, his chin propped on top of her head.

“I’m sorry, sis,” he told her. The phrase sounded so lame.

Molly sniffled and drew back, smiling up at him. “Come on inside. I just made iced tea, and the kids will be back soon. My crew went to pick up some pizza—late lunch, early dinner whatever—and Griffin and Fletcher went with them.” Her eyes misted over. “I’ve told them about the operation and rehab and how they’ll be going back to Parable with you, but I’m not sure they really understand.”

Boone nodded and followed his sister up the porch steps and on into the house. While it wasn’t a mansion, the colonial was impressive in size and furnished with a kind of casual elegance that would be impossible to pull off in a thirdhand double-wide.

“I imagine they’ll have plenty of questions,” he said as they passed beneath the glittering crystal droplets dangling from the chandelier in the entryway. An antique grandfather clock ticked ponderously against one wall, measuring out what time remained to any of them, like a heartbeat. Life was fragile, anything could happen.

Molly glanced back at him over one shoulder, nodded. “I told them they’d be coming back here in a couple of months,” she replied. “After their uncle Bob has some time to heal.”

Boone didn’t comment. Despite his trepidation—he definitely considered himself parentally challenged—a part of him, long ignored but intractable, remained stone-certain that Griffin and Fletcher belonged with him, their father, on the little spread beside the river. Home, be it ever so humble.

This wasn’t the time to discuss that, though. Molly loved her nephews like they were her own, and with so many things to cope with, she didn’t need anything more to worry about.

And worry she would. With all that roiling in Boone’s mind, he and Molly passed along the wide hallway that opened onto a big dining room with floor-to-ceiling windows on one side overlooking the side yard, where a small stone fountain stood spilling rainbow-colored water and surrounded by thriving rosebushes. The scene resembled a clip from HGTV.

They’d reached the sunlit kitchen when Molly spoke again, employing her being-brave voice, the one she’d used during the hard days after their parents had died. She’d been just nineteen then, to Boone’s fifteen, but she’d managed to step up and take charge of the household.

“Griff is excited—already has his bags packed,” she told Boone, as she opened the refrigerator door and reached in for the pitcher of tea. Bright yellow lemon slices floated among the tinkling ice cubes, and there were probably a few sprigs of mint in there, too. Molly believed in small gracious touches like that. “Fletcher, though—” She stopped, shook her head. “He’s less enthusiastic.”

Boone suppressed a sigh, baseball cap in hand, looking around him. The kitchen was almost as big as his whole double-wide, with granite surfaces everywhere, real wood cabinets with gleaming glass doors, top-of-the-line appliances that, unlike the hodgepodge at his place, actually matched each other. There was even a real brick fireplace, and the table, with its intricately mosaicked top, looked long enough to accommodate a serious crowd.

Back at the double-wide, more than three people at a meal meant someone had to eat in the yard, or on the back steps, balancing a throwaway plate on their lap.

Molly smiled somewhat wistfully, as if she’d guessed what he was thinking, and gestured for Boone to sit down. Then she poured two tall glasses of iced tea and joined him, placing the pitcher in the middle of the table. Sure enough, there were little green leaves floating in the brew.

“Fletcher will adjust,” Molly went on gently. Her perception was nothing new; she’d always been able to read him, even when he put on a poker face. She was the big sister, and she’d been a rock after the motorcycle wreck that killed their mom and dad. Somehow, she’d seen to it that they could stay in the farmhouse they’d grown up in, putting off going to college herself until Boone had finished high school. She’d waitressed at the Butter Biscuit Café and clipped coupons and generally made do, all to prevent the state or the county from stepping in and separating them, shuffling Boone into foster care.

In the aftermath of the tragedy, the whole community of Parable had helped, the way small towns do, with folks sharing produce from their gardens, eggs from their chicken coops, milk from their cows, clothes from their closets, all without any hint of charity. Boone had done odd jobs after school and on weekends, but the main burden of responsibility had always been Molly’s.

Oh, there’d been some life insurance money, which she’d hoarded carefully, determined that they would both get an education, and the farm, never a big moneymaker even in the best of times, had at least been paid for. Their mom had been a checker at the supermarket, and their dad had worked at the now-closed sawmill, and somehow, latter-day hippies though they were, they’d whittled down the mortgage over the years.

The motorcycle had been their only extravagance—they’d both loved the thing.

When Boone was ready for college, he and Molly had divided the old place down the middle, with the house on Molly’s share, at Boone’s insistence. She’d sold her portion to distant cousins right away and, later on, those cousins had sold the property to Tara Kendall, the lady chicken rancher. Thus freed, Molly had studied business in college and eventually met and married Bob and given birth to three great kids.

And if all that hadn’t been enough, she’d stepped up when Corrie got sick, too, making regular visits to Parable to help with the kids, just babies then, cook meals, keep the double-wide fit for human habitation, and even drive her sister-in-law back and forth for medical treatments. Boone, young and working long hours as a sheriff’s deputy for next-to-no money, had been among the walking wounded, mostly just putting one foot in front of the other and bargaining with God.

Take me, not her.

But God hadn’t listened. It was as if He’d stopped taking Boone’s calls, putting him on hold.

Now, poignantly mindful of all that had gone before, Boone felt his eyes start to burn. He took a long drink of iced tea, swallowed and said, “Where were we?”

Molly’s smile was fragile but totally genuine. She looked exhausted. “I was telling you that your younger son isn’t as excited about going home with you as his older brother is.”

A car pulled up outside, doors slammed. Youthful voices came in through the open windows that made the curtains dance against the sills.

“Yeah,” Boone said. “I’ll deal with that. You just think about yourself, and Bob, and your own kids.”

Right on cue, Molly’s trio of offspring, two girls and a boy, rattled into the house. Ted, the oldest, had a driver’s license, and he carried a stack of pizza boxes in his big, basketball-player’s hands, while the girls, Jessica and Catherine, twelve and thirteen respectively, shambled in after him, bickering between themselves.

Griffin and Fletcher, who had accompanied them, were still outside.

When Jessica and Cate spotted Boone, their faces lit up and their braces gleamed as they smiled wide. They were pretty, like their mother, while Ted looked like a younger version of Bob, a boy growing into a man.

“Uncle Boone!” Jessica crowed.

He stood up, and just in time, too, because his nieces promptly flung themselves into his arms. He kissed them both on top of the head, an arm around each one, and nodded to his more reserved nephew.

Ted nodded back, and set aside the pizza boxes on one of the granite countertops. “I guess Mom told you about Dad being injured,” he said, with such an effort at manly self-possession that Boone ached for him.

“She told me,” Boone confirmed.

His nieces clung to him, and suddenly there were tears in their eyes.

“It’s awful, what happened to Dad,” said Jessica. “It must hurt like crazy.”

“He’s being taken care of,” Molly put in quietly.

Boone again squeezed both girls, released them. After a pause, he asked, “What’s keeping those boys of mine?”

“They’re admiring your truck,” Ted put in, grinning now.

Boone didn’t explain that he’d borrowed the rig from his best friend; it just didn’t matter. He wondered, though, if Griff and Fletch were avoiding him, putting off the unexpected reunion as long as they could.

Then the screen door creaked on its hinges and Boone braced himself.

Molly cleared her throat. “Kids,” she said quietly, addressing her brood. “Wash up and we’ll have pizza.”

“We’re still going to visit Dad tonight, right?” Cate asked worriedly.

“Yes,” Molly answered, as Boone’s young sons crossed the threshold and let the screen door slam behind them.

Ted, Jessica and Cate all left the room. Boone wondered if they were always so obedient and, if so, what was the magic formula so he could try it out on his own kids?

Meanwhile, Griff, the older of the pair, straightened his spine and offered a tentative smile. “Hello, Dad,” he said.

Fletcher, the little one, huddled close to his brother, their scrawny shoulders touching. “I don’t want to go to stupid Parable,” the boy said. He looked scared and sad and obstinate all at once, and his resemblance to his late mother made Boone’s breath snag painfully in the back of his throat. “I want to stay here!”

Boone walked over to them but left a foot or two of personal space.

“Uncle Bob broke his knee,” Griffin said, in case word hadn’t gotten around. “Ted says they’re going to give him a plastic one.”

Boone nodded solemnly, waiting. He didn’t want to crowd these kids, or rush them, either, but he was chafing to load up whatever stuff they wanted to take along and head for Parable.

“I’m ready to go anytime,” Griff announced.

“Not me,” Fletch glowered, folding his skinny arms and digging in the heels of his sneakers.

Boone crouched so he could look both boys in the eye. “It’s important to everybody, including your Uncle Bob, that you guys go along with the plan. That shouldn’t be too hard for a couple of tough Montana cowboys, right?”

Griff nodded, ready to roll, prepared to be as tough as necessary.

Fletcher, on the other hand, rolled out his lower lip, his eyes stormy, and warned, “I wet the bed almost every night.”

Boone recognized the tactic and maintained a serious expression. “Is that so?” he asked. “Guess that’s something we’ll have to work on.”

Fletcher nodded vigorously, but he kept right on scowling. He had Boone’s dark hair and eyes, as Griffin did, but he was Corrie’s boy, all right.

“He smells like pee every morning,” Griffin commented helpfully.

In a sidelong glance at Molly, who was getting out plates and silverware and unboxing the pizza, Boone saw her smile, though she didn’t say anything.

“Shut up, Griff,” Fletcher said, reaching out to give his brother an angry shove.

“Whoa, now,” Boone said, still sitting on his haunches, putting a hand to each of their small chests to prevent a brawl. “We’re all riding for the same outfit, and that means we ought to get along.”

His sons glared at each other, and Fletcher stuck out his tongue.

They were probably too young to catch the cowboy reference.

Boone sighed and rose to his full height, knees popping a little.

“Pizza time!” Molly announced, as Ted, Jessica and Cate reappeared, traveling in a ragtag little herd.

For a family in what amounted to a crisis, if not a calamity, they all put away plenty of pizza, but the talk was light. Every once in a while, somebody spoke up to remind everybody else that Bob would be fine, at least in the long run. New knee, good to go.

It was dark outside by the time the meal was over.

Boone did the cleanup, since Molly refused to let him reimburse her for the pizza.

Fletcher had been cajoled into letting Jessica and Cate help him pack, and Ted had loaded the suitcases in the back of Hutch’s truck.

Both boys needed booster seats, being under the requisite height of four foot nine dictated by law, and transferring those from Bob and Molly’s car and rigging them up just right took a few minutes with Molly helping and Fletcher sobbing on the sidewalk, periodically wailing that he didn’t want to go, couldn’t he please say, he wouldn’t wet the bed anymore, he promised. He swore he’d be good.

Boone’s heart cracked down the middle and fell apart. He hugged Molly goodbye—knowing she and the kids were anxious to get over to the hospital and visit Bob—shook his nephew’s hand and nodded farewell to his nieces.

“Tell Bob I’m thinking about him,” Boone said.

Molly briefly bit her lower lip, then replied, “I will.” Her gaze was on Griffin and Fletcher now, as if drinking them in, memorizing them. Her eyes filled with tears, though she quickly blinked them away.

Boone lifted a hand to say goodbye and got into the truck.

Molly stepped onto the running board before he could pull away, and spoke softly to the silent little boys in the backseat. “You guys be good, okay?” she said, in a choked, faint voice. “I’m counting on you.”

Turning his head, Boone saw both boys nod in response to their aunt’s parting words. They looked nervous, like miniature prisoners headed for the clink.

Molly smiled over at Boone, giving him the all-too-familiar you can do this look she’d always used when she thought he needed motivation or encouragement. “We’ll keep you posted,” she promised. And then she stepped down off the running board and stood on the sidewalk, chin up, shoulders straight.

Boone, who’d already used his quota of words for the day, nodded again and buzzed up the windows, bracing himself for the drive home.

It was going to be a long night.

* * *

TARA CALLED JOSLYN from the front seat of her previously owned but spacious SUV, watching as one of the car-lot people drove her cherished convertible around a corner and out of sight. She felt a pang when it disappeared, headed for wherever trade-ins went to await a new owner.

“I just wanted to let you know that I won’t be needing to borrow the station wagon, after all,” she said into the phone, studying the unfamiliar dashboard now. Lucy was in back, buckled up and ready to cruise.

“Okay,” Joslyn said, her tone thoughtful. “Mind telling me what’s going on?”

Still parked in the dealer’s lot, with hundreds of plastic pennants snapping overhead, Tara bit her lip. “It’s a long story,” she said after a moment’s hesitation. “Short version—Elle and Erin, my ex-husband’s twelve-year-old twins, are arriving tomorrow. Since we couldn’t all fit in the Mercedes—”

“Elle and Erin,” Joslyn repeated. She and Kendra Carmody were Tara’s best friends, and yet she’d never told either of them about the twins, mostly because talking about Elle and Erin would have been too painful. All Kendra and Joslyn knew was that there had been an ugly divorce.

“I’ll tell you the whole story later,” Tara said, eyeing the passing traffic and hoping she wouldn’t feel as though she were driving an army tank all the way back to Parable. “It’s time to get home and feed the chickens.”

“Right,” Joslyn said. “Exactly when is ‘later’ going to be?”

“Tonight?” Tara suggested. “You and Kendra could stop by my place for lemonade or tea or something?”

Once, she would have offered white wine instead, but Kendra was expecting, and Joslyn, the mother of a one-year-old son, was making noises about getting pregnant again, soon.

“I can make it,” Joslyn replied, clearly intrigued. “I’ll give Kendra a call—what time would be good?”

“Six?” Tara said, uncertain. She lived alone, while both her friends had husbands, and, in Joslyn’s case, kids, as well. They’d have to take family matters, like supper, into consideration.

“Make it seven and we’re good,” Joslyn said. “See you then.”

They ended the call with lighthearted goodbyes, and Tara turned in the driver’s seat to look back at Lucy. The dog wore a blue bandanna and her sunglasses dangled from a loose cord around her neck. “Hold on,” she said. “One test-drive doesn’t make me an expert at handling the big rigs.”

Lucy yawned and relaxed visibly, though she couldn’t lie down with the seat belt fastened around her. As always, she was ready to go with the flow.

They drove back to Parable and then home to the farm, blessedly without incident. There, Tara was met by a flock of testy chickens, probably suffering from low blood sugar. She rushed inside and up the stairs, Lucy right behind her, and exchanged her sundress and sandals for coveralls and ugly boots, the proper attire for feeding poultry and other such chores, and returned to the yard.

Lucy, who was alternately curious about the birds and terrified of their squawking, kept her distance, waiting patiently in the shade of the overgrown lilac bush that had once disguised a privy.

“Dog,” Tara said, gathering handfuls of chicken feed from a dented basin and flinging the kernels in every direction, “we are definitely not in New York anymore.”

CHAPTER THREE

BOTH THE BOYS were sound asleep in their safety seats when Boone finally pulled up in his own rutted driveway around eight that night, shut off the truck engine and gazed bleakly into his immediate future. A concrete plan for the long term would have been good, a to-do list of specific actions guaranteed to carry Griffin and Fletcher from where they were right now—confused and scared—right on through to healthy, productive manhood.

Boone sighed. One step at a time, he reminded himself silently. Just put one foot in front of the other and keep on keeping on. For now, he only had to think about getting his sons inside and bedded down for the night. After that, he’d take a quick shower and call to let Molly know that he and the kids had arrived home safely. Then, if it wasn’t too late, he’d give Hutch a ring, too, and tell him his truck was still in one piece, offer to drop it off at Whisper Creek before he went on to work in the morning.

Work. Inconvenient as it was, Boone was still sheriff, with a whole county full of good people depending on him, and a few bad apples to keep an eye on, too, and that meant he’d be in his office first thing tomorrow, with his boys tagging along, since he had yet to make any kind of child-care arrangements.

Just then, things seemed patently overwhelming. One step, he reiterated to himself, and then another.

Glad to be out of a moving vehicle and standing on his own two feet, Boone opened one of the rear doors and woke Griffin first with a gentle prod to the shoulder. The boy yawned and blinked his eyes and then grinned at Boone in the dim glow of the interior lights. “Are we there?” the kid asked, sounding hopeful.

Boone’s heart caught. “We’re there,” he confirmed with a nod, then unfastened Fletcher from the safety seat. Griffin scrambled out of the truck on his own, but the little guy didn’t even wake up. He just stirred slightly, his arms loose around Boone’s neck, his head resting on his shoulder.

For all Boone’s trepidation about getting the dad thing right, it felt good to be holding that boy. Real good.

They started toward the double-wide, slogging through tall grass. The trailer was pretty sorry-looking in broad daylight, and darkness made it look even worse, like a gloomy hulk, lurking and waiting to pounce. Why hadn’t he thought to leave a light burning before he took off for Missoula in such an all-fired hurry?

“I bet Fletch peed his pants,” Griffin said sagely, trekking along beside Boone with his small suitcase in one hand. “He stinks.”

Sure enough, the seat of Fletcher’s impossibly small Wranglers felt soggy against Boone’s forearm, and there was a smell, but it wasn’t a big deal to a man who’d spent whole nights guarding some drunken miscreant at the county jail.

Boone spoke quietly to Griffin, man-to-man. “Let’s not rag on him about that, okay? He’s still pretty little, and there’s a lot to get used to—for both of you.”

Griffin nodded. “Okay,” he agreed solemnly.

They climbed the steps to the rickety porch, Boone going first, and once he’d gotten the door open and stepped inside, he flipped the light switch.

They were in the kitchen, but in that first moment Boone almost didn’t recognize the room. The dishes he’d left piled in the sink had been done up and put away. The linoleum floor didn’t exactly shine, being so worn, with the tar showing through in some places, but it glowed a little, just the same.

The effect was almost homey.

“Do we sleep where we did when we visited before?” Griffin asked. He sounded like a very small man, visiting a foreign country and eager to fit into the culture without breaking any taboos.

Still carrying Fletcher, who was beginning to wriggle around a bit now, Boone nodded a distracted yes and, having spotted the note propped between the sugar shaker and the jar of powdered coffee creamer in the middle of the table, zeroed in on it.

Griffin marched off to inspect the cubbyhole he and Fletcher would be staying in while Boone picked up the note. It was written in Opal Dennison’s distinctive, loopy handwriting, and he smiled as he read it. Although she kept house for Slade and Joslyn Barlow, Opal was definitely a free agent, working where she wanted to work, when she wanted to work.

Hutch called and said your boys were coming home for a spell, and you’d all probably get in tonight, so I let myself in and spruced the place up a mite. There’s food in the refrigerator and I put clean sheets on the beds and some fresh towels in the bathroom. I’ll be over first thing tomorrow morning to look after those kids while you’re working, and don’t even think about telling me you can manage on your own, Boone Taylor, because I didn’t just fall off the turnip truck.

She’d signed the message with a large O.

Boone set the slip of paper back on the table and carried a now-wakeful Fletch into the one and only bathroom. He set the boy on the lid of the toilet seat and started water running into the tub, which, thanks to Opal, was well scrubbed. Boone always showered, and that seemed like a self-cleaning type of operation, so he rarely bothered with the tub.

Fletch, realizing where he was, and with whom, rubbed both eyes with small grubby fists and immediately started to cry again.

“Hey,” Boone said quietly, turning to crouch in front of him the way he’d done earlier, in Molly’s kitchen. “Everything’s going to be all right, Fletcher. After a bath and a good night’s sleep, you’ll feel a whole lot better about stuff, I promise.”

He’d told the boys, during the first part of the drive back from Missoula, that their uncle Bob, hurt the way he was, would need lots of care from their aunt Molly and the cousins, so that was why they were going back to Parable to bunk in with him for a while. It was the best way they could help, he’d explained.

Griff hadn’t said anything at all in response to his father’s short and halting discourse. He’d just looked out the window and kept his thoughts to himself, which, in some ways, concerned Boone more than Fletcher’s intermittent outbursts. The littlest boy had exclaimed fiercely that he wanted to go back and help take care of Uncle Bob for real, and would Boone just turn around the truck right now, because Missoula was home, not Parable. When Boone had replied that he couldn’t do that, Fletch had cried as if his heart had been broken—and maybe it had.

After quite a while, during which Boone felt three kinds of useless and just kept driving because he knew the kid would have resisted any kind of fatherly move, like stopping the truck and taking him into his arms for a few minutes, Fletcher’s sobs gradually turned to hiccups. That went on for a long time, too, like the crying, before he finally fell into a fitful sleep, exhausted by the singular despair of being five years old with no control over his own fate.

Now, in this run-down bathroom, with the finish peeling away from the sides of a tub hardly big enough to accommodate a garden gnome, and the door off the cupboard under the sink letting the goosenecked pipe and bedraggled cleaning supplies show, Boone waited, still sitting on his haunches, for Fletcher’s response to the tentative promise he’d made moments before.

It wasn’t long in coming. “Everything won’t be all right,” Fletcher argued. “You’re not my dad—I don’t care what Griff says—Uncle Bob is my dad—and I’m not staying here, because I hate you!”

This was a scared kid talking, Boone reflected, but the words hurt just the same, like a hard punch to the gut.

“I can see why you’d feel that way,” he answered calmly, reasonably, catching a glimpse of Griffin out of the corner of his eye. The boy huddled in the bathroom doorway, looking on worriedly, so small in his jeans and striped T-shirt, with his shoulders hunched slightly forward, putting Boone in mind of a fledgling bird not quite trusting its wings. “But we’re going to have to make the best of things, you and Griff and me.”

Fletcher glared rebelliously at Boone and slowly shook his head from side to side.

“Dad?” Griff interceded softly. “I can help Fletcher with his bath, get him ready for bed and everything, if you want me to.”

Boone sighed as he rose to his full height. “Maybe that would be a good idea,” he said, shoving a hand through his hair, which was probably creased from wearing the baseball cap all day. He was still in the clothes he’d put on to go fishing early that morning, too, and he felt sweaty and tired and sad.

“He’s got pajamas in the suitcase,” Griffin said helpfully. “You could get them out—they’re the ones with the cartoon train on the front....”

Boone smiled down at his older son and executed an affable if lazy salute. “Check,” he said, starting down the short hallway to follow through on the errand assigned. As he walked away, he could hear Griff talking quietly to his little brother, telling him he’d like living here, if he’d just give it a chance.

Griffin was clearly having none of it.

Boone went outside, retrieved the suitcases and brought them in, opening the smaller one after setting both bags on the built-in bed that took up most of the nook of a bedroom reserved for the boys. Back in Missoula, they shared a room four times that size, with twin beds and comforters that matched the curtains and even a modest flat-screen TV on the wall.

He sighed again, bent over the suitcase and rooted through for the pajamas Griff had described. He found them, plus a couple toothbrushes in plastic cases, each one labeled with a name.

He took the lot back to the bathroom and rapped lightly on the now-closed door. “Pajama delivery,” he said, in the jocular tone of a room-service person.

There was some splashing in the background, and Griff opened the bathroom door far enough to reach for the things Boone was holding, grinning sympathetically.

“Thanks, Dad,” Griff said in a hushed voice.

Boone nodded in acknowledgment, turned away and wandered back into the kitchen, where he picked up the receiver from the wall phone and called Molly and Bob’s home number.

Molly answered right away. “Boone?” she said.

“Yep,” Boone replied. “We got home just fine.”

“Good,” Molly responded. “How are they doing? Griffin and Fletcher, I mean?”

“As well as can be expected, I guess,” Boone said, as another wave of weariness swept over him. “How’s Bob?”

“He’s probably asleep by now,” Molly answered. “He goes into surgery at six tomorrow morning.” She paused, though not long enough for Boone to wedge in a reply. “Are they in bed already? Griffin and Fletcher, I mean? Did they brush their teeth? Say their prayers?”

“Fletch is in the tub, mother hen,” Boone told his frazzled sister, with a smile in his voice. “We’ll get around to the rest of it later.”

Molly gasped, instantly horrified. “Fletcher is in the tub by himself?”

Boone frowned as it came home to him, yet again, how much he didn’t know about bringing up kids. “Griff is with him,” he said.

“Oh,” said Molly, clearly relieved.

“So things are pretty much okay on your end?” Boone asked. He was out of practice as a father, and every part of him ached, from the heart out. Bob was in for some serious pain and a long, rigorous recovery, and Molly, Ted, Jessica and Cate had no choice but to go along for the ride.

“We’re doing all right,” she said. “Not great, but all right.”

“You’ll let me know if there’s anything you need?”

“You know I will,” Molly answered. She paused a beat before going on. “Can we stay in touch by text and email for a while? I’m not sure I’m going to have enough energy for the telephone right at first, and I’m afraid every time I hear the boys’ voices, I’ll burst into tears and scare the heck out of them. I already miss them so much.”

Boone’s reply came out sounding hoarse. “Do whatever works best for you,” he said. “I’ll look after the boys, Molly. I’ll figure all this fathering stuff out. In the meantime, try to stop worrying about us, okay? Take care of yourself, or you’ll be no good to Bob and the kids. In other words, get some rest.”

“I’ll try,” she said, and he knew she was smiling, although she was probably dead on her feet after the day she’d put in. “You’re a good brother, Boone. And I love you.”

“Flattery will get you everywhere,” Boone answered. “And I love you, too. I’ll text or email tomorrow.”

“Me, too,” Molly said. “Bob will be out of surgery around noon.”

They said their goodbyes and rang off.

Boone glanced at the wall clock, decided it was still early enough to call Hutch and punched in the numbers for his friend’s landline.

Hutch answered on the second ring. “Back home?” he asked, instead of saying hello. Thanks to caller ID, people tended to skip the preliminaries these days and launch right into the conversation at hand.

“Yep,” Boone answered.

“How are Molly and Bob?”