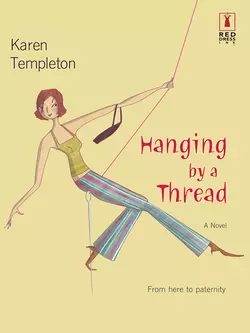

Hanging by a Thread

Karen Templeton

You can take the girl out of Queens…Or can you? Because for five years, fashion assistant Ellie Levine was taking a halfhearted stab at it, commuting to Manhattan by day, trying desperately to keep secret her outerborough existence–that accent, that hair…that daughter. Until the day fate landed her back in her Richmond Hill neighborhood 24/7, the very place she'd sworn to escape.Now she has a business to run there–not the business she had in mind, perhaps, but a business nonetheless. And the boy next door, who for years had been the married-man-next-door, is suddenly available. And interested?Maybe there really is no place like home. So even if you can take the girl out of Queens, would you?

Hanging by a Thread

KAREN TEMPLETON

spent her twentysomething years in New York City. Before that, she grew up in Baltimore, then attended North Carolina School of the Arts as a theater major. A RITA

Award-nominated author of seventeen novels, she now lives with her husband, a pair of eccentric cats and four of their five sons in Albuquerque, where she spends an inordinate amount of time picking up stray socks and mourning the loss of long, aimless walks in the rain. Visit her Web site at www.karentempleton.com.

Hanging by a Thread

Karen Templeton

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

This book is dedicated to anyone who’s struggling with seemingly impossible decisions, and to anyone who’s made a few that have come back to haunt you.

I trust Ellie’s story will give you hope.

Or if not hope, at least a good laugh.

And to all the folks on the richmondhillny.com message board…thanks for actually believing I was a writer and not some weirdo stalker, and double thanks for answering what I’m sure were some really eye-rolling questions.

Contents

chapter 1

chapter 2

chapter 3

chapter 4

chapter 5

chapter 6

chapter 7

chapter 8

chapter 9

chapter 10

chapter 11

chapter 12

chapter 13

chapter 14

chapter 15

chapter 16

chapter 17

chapter 18

chapter 19

chapter 20

chapter 21

chapter 22

chapter 23

chapter 24

chapter 25

chapter 26

chapter 27

chapter 28

Postscript

chapter 1

Through a jungle of eyelashes, eyes the color of overcooked broccoli assess the image in front of them. Which would be me, a short, pudgy woman in (mostly) men’s clothes, clutching a size eight (regular) Versace suit. Scrambled data is transmitted to Judgment Central while a bloodred, polyurethane smile assures me the saleswoman’s only reason for living is to serve me. Whatever galaxy I’m from.

“Would you—” eyes dart from me to suit back to me “—like to try this on?”

An understandable reaction, since we both know I’ve got a better chance of finding Hugh Jackman in my bed than shoving my butt into this skirt.

I lean forward conspiratorially. “It’s for my sister,” I whisper. “For her birthday. A surprise.”

The smile doesn’t falter—she’s been trained well—but I can’t quite read her expression. I’m guessing either pity for my apparently having been dredged from the stagnant end of the gene pool, or—more likely—seething envy that I’m not her sister. Not that I would actually buy my own sister an eight-hundred-dollar anything, but still.

“Oh.” Smile falters a little. “All right. Will that be a charge?” A discreetly tasteful vision in taupe and charcoal, she leads me to the register, her movement all that keeps her from blending completely into her cave-hued surroundings. Why is it that half the sales floors in this city these days make me want to go spelunking instead of shopping?

“No. Cash,” I say, clumping cheerfully behind in my iridescent magenta Jimmy Choo knockoff platform pumps. When we get to the counter, I dig in my grandmother’s ’70s vintage LV bag for my wallet, from which I coolly extract nine one-hundred-dollar bills and hand them over. I grin, brazenly flashing the dimples.

She cautiously takes the money, as if whatever’s tainting it might somehow implicate her, mumbles, “Er, just a minute,” then vanishes. To check that it’s not counterfeit, maybe. While I’m waiting, my gaze wanders around the sales floor, checking out both the flaccid, shapeless offerings on display and the equally shapeless women—all of whom put together wouldn’t make a decent size 6—circling, considering. The air hums with awe and expectancy. Their breathing quickens, their skin flushes: tops, skirts, dresses are plucked from racks, clutched to nonexistent bosoms, ushered into hushed waiting rooms for a hurried, frenzied tryst. For some, there will be an “Oh, God, yes!” (perhaps more than once, if they chose well), the heady rush of fulfillment, transient and illusory though it may be. For others (most, in fact), the encounter will prove a letdown—what seemed so alluring, so enticing at first glance fails to meet unrealistic expectations.

But true lust is never fully sated, and hope inevitably supplants disappointment. Which means that soon—the next day, maybe the day after that—the cruising, the searching, the trysts will begin anew.

Thank God, is all I have to say. Otherwise, schnooks like me would starve to death.

My unwitting partner in crime returns, her smile a little less anxious. Apparently I’ve passed the test. Or at least my money has.

“Would you…like that gift-wrapped?”

“Just a box, thanks.”

My conscience twinges, faintly, as I watch her lovingly swathe the suit in at least three trees’ worth of tissue paper, laying it tenderly in a box imprinted with the store’s logo, as if preparing a loved one for burial. The irony touches me. Minutes later, I’m hoofing it back downtown in a taxi, the suit ignorantly, trustingly huddled against my hip.

The taxi reeks of some oppressively expensive perfume, making my contact lenses pucker, making me almost miss the days when cabs smelled comfortingly of stale cigarettes. Opening the window is not an option, however, since Reykjavik is warmer than it is in Manhattan right now. It’s that first week after New Year’s, when the city, bereft of holiday decorations, looks like an ugly naked man left shivering in an exam room. I take advantage of a traffic snarl at 50th and Broadway to fish my cell phone out of my purse and call home, half watching swarms of tourists trying to decide whether or not to cross against the light. They’re so cute I can’t stand it.

“Mama!”

I’m immediately sucked back through time and space, not just to Richmond Hill, Queens, but into another dimension entirely. Instead of feeling connected, I feel oddly disconnected, that the woman in this taxi is not the person my daughter hears on the other end of the line. In the background, I hear Mr. Rogers reassuring his tiny viewers about something or other (my throat catches—how could Mr. Rogers die?). Guilt spurts through me again, sharper this time; I push the box slightly away, spurning it and everything it connotes, as if Fred Rogers is looking down from Heaven and sorrowfully shaking his head at me.

“Hey, Twink,” I say to the little girl who dramatically altered the course of my life half a decade ago. “Whatcha doing?”

You would think I would know by now not to ask leading questions of loquacious, detail-obsessed five-year-olds.

“I got hungry so I fixed myself a peanut butter sandwich,” Starr says, “but the bread was totally icky so I had cheese and crackers instead, and a pickle, and then I had to pee, and then you called so now I’m talking to you. Oh, and I saw the cutest puppy on TV—” a subject she’s managed to wedge into every conversation over the past three months “—and Leo said he’d take me for a walk later, if it’s warm enough, and you would not believe the loud fight those people behind us had this morning—”

I elbow my way through a comma and say, “That’s nice, honey…can I talk to Leo for a sec?”

I hear breathing. Then: “So can we?”

“Can we what?”

Breathing turns into a small, pithy, much-practiced sigh. “Get a puppy.”

Considering I want a puppy about as much as I want a lobotomy, I say, “We’ll see,” because I’m in a taxi and this is using up my free minutes and while I basically know more about nuclear physics than I do about mothering, I do know what kind of reaction “No, we can’t” will bring. And I have neither the minutes nor the strength to deal with the ramifications of “no” today.

Of course, the little breather on the other end of the line is a poignant reminder of the ramifications of “yes,” but there you are.

“Put Leo on,” I say again. Breathing stops, followed by a clunk, followed by heavier, masculine breathing.

“Yes, I’m still alive,” are the first words out of my grandfather’s mouth.

“Just checking,” I say, playing along. Sharing the joke. Except my father’s father had a quadruple bypass a few years ago. So the joke’s not so funny, maybe. I can hear, immortalized through the magic of reruns, King Friday pontificating about something or other. My grandfather is not immortal, however; there will be no reruns of his life, except in my memory. An unreliable medium, as I well know.

“Just checking?” He chuckles. “Three times, you’ve called today.”

“I worry,” I say, sounding like every woman stretching back to Eve. Whose real reaction to Adam’s nakedness was probably, “For God’s sake, put something on, already! You want to catch your death?”

“You shouldn’t worry,” my grandfather says. “It can kill you.”

Black humor is a big thing in my family. A survival tactic, ironically enough. “I’ll take that chance.”

Another chuckle; I listen carefully for any sign the man might momentarily drop dead. Never mind he’s been healthy as a horse since the operation. But at seventy-eight, he’s already bucking the family odds. I mean, one glance at my family medical history and the insurance examiner got this look on her face like she half expected me to keel over in front of her.

With good reason. Not only does our family exhibit a propensity for dying young, but without warning. Well, except for my mother. But other than that, it’s hale and hearty one minute, gone the next, boom. My mother, at forty, from ovarian cancer. My father at fifty-one, massive heart attack. Grandmother, sixty-three, stroke. Assorted aunts, uncles, third cousins—boom, boom, boom. Okay, and one splat, but Uncle Archie always had been the black sheep in the family.

“Well,” my grandfather says, amused, “nothing’s changed since lunchtime, I’m fine, the baby’s fine, everybody’s fine. Except maybe you.”

By the way, my graduation present was a burial plot. What can I tell you, the Levines tend to be practical people.

I change the subject. “You fix the Gomezes’ leaky faucet?”

My grandfather owns a pair of duplexes. We all live in one, he rents out the two apartments in the other. Sure, they bring in extra cash, but speaking as somebody who finds changing a lightbulb a pain in the butt, I keep thinking he should just sell the place, give over the responsibility to someone else.

“This morning,” he says. “Think maybe I’ll switch out their refrigerator, too.”

“What’s wrong with their fridge? It can’t be more than, what? Ten years old?”

“It’s too small. Especially with the new baby coming.”

Which would make their third. Sometimes, I’m surprised Leo even bothers to collect the rent. These aren’t tenants, they’re family. Not that I don’t like the Gomezes—or the Nguyens, in the upstairs apartment—don’t get me wrong. Mr. Gomez paints his own apartment, just asks Leo for the paint; and Mrs. Nguyen’s window boxes in the summer are the envy of the neighborhood, regular forests of petunias. Besides, the Gomez kids give Starr somebody to play with, on those odd occasions when she’s in the mood for other children. It’s just…oh, hell, I don’t know. I just think he should be free by now, you know?

“Don’t worry,” he says. “I can sell the old one, it’ll be okay.”

My brain’s slipped a cog. “Old what?”

“Refrigerator.”

“Oh.” The taxi driver blats his horn, scaring the crap out of me. Nothing moves, however. “Starr says maybe you’ll take her for a walk later?”

“I thought maybe. We’ve been cooped up in this house too long. It’s up in the mid-twenties, I’ll make sure she’s warm, don’t worry.”

But this time, even as I smile, I realize the knot in my gut isn’t anxiety (for once), it’s something closer to envy. My grandfather will dress my daughter in her leggings and heavy, puffy coat and mittens and that silly fake fur hat he gave her for Christmas—she will look adorable, very Beatrix Potter—just as he did me when I was her age, and take her on the same walk, up and down the funny little elevated Richmond Hill sidewalks, show her the same things, tell her the same stories. Will she listen as I did? Will she be as enthralled with Leo Levine as I was at her age?

As I still am?

“And I think you should get her that dog,” he says, and the sentimental bubble I’d been floating in goes pfft. “We could go to the pound on Saturday, let her pick. Something small.”

I shudder. “Small dogs are yippy. And neurotic.”

“A big dog, then.”

“Like either of us wants to pick up a big dog’s poop. Anyway, I probably have to work on Saturday,” I add, which is the truth.

“Again?”

“You know Market Week’s coming up. Nikky needs me.”

“Your daughter needs you, too,” he says quietly. “So do I, for that matter.”

I get this funny, tight feeling in my chest. “Oh, come on—you two do just fine without me.”

“That’s not the point.” I can hear the smile in his voice. “When you’re not around, it’s like…like ice cream without the chocolate sauce. Nothing wrong with plain ice cream, plain ice cream is fine. But with chocolate sauce, ah…then it’s a party.”

I laugh, which jostles loose the funny feeling, just a little. “Great. Now I’m gonna crave an ice-cream sundae for the rest of the day.”

“So. You won’t work on Saturday?”

My smile fades. “I’m sorry. I have to.”

“What kind of life is this, that you can’t spend the whole weekend with your daughter?”

“It’s my life,” I say softly, because what else can I say? “The one where I have to work to support my kid, you know? Like you and Dad did your kids?”

“That was different,” he says, with a deep sadness, like a man watching helplessly from the riverbank as floodwaters wash away everything he’s known and accepted as real, solid, indestructible.

“Yes, it was.” Up ahead, traffic finally jars loose. I skid across the slick seat like a pinball as the cabby swerves into what he perceives to be an opening in the next lane. “We’ll talk later,” I say, adding, “I’ll try to be home by six,” before clapping my phone shut and stowing it back in my bag, shoving that part of my existence right in there with it.

I swear, sometimes I feel like Batman, living two lives. Except I’d look totally stupid in that outfit.

We shoot through Times Square and on down Seventh Avenue like a front-runner in the Daytona 500. Something like three seconds later, the taxi screeches to a halt in front of the building that houses Nicole Katz’s showroom and offices, way up in the thirtieth floor penthouse.

The cabby nods his thanks at the hefty tip—I’m very generous with other people’s money—and I haul myself and the poor unsuspecting garment out of the cab. I can feel the cabby’s eyes glued to my backside as I dodge passersby to get to the revolving door. Considering the amount of clothes I have on, the guy must have some imagination, is all I have to say. Considering how long it’s been since I’ve had anything even remotely resembling sex, I’m not even tempted to take offense.

Thirty stories and a major head rush later, the elevator opens directly onto reception. Chinoiserie for days, lots of black lacquer and reds and yellows, don’t ask. I’m sure it was cutting edge in 1978. Sprawled across the wall over the reception desk like a row of stoned Bob Fosse dancers, ridiculously large, gleaming gold letters spell out:

Nicole Katz, Ltd.

Valerie, our receptionist since Christmas, is too deeply engrossed in what I assume is a personal phone call (frown line snuggled neatly between her dark brows, liberal use of “Ohmigod!”) to acknowledge my return as I pass the desk. Whatever. She’s twenty-one. Engaged. Working at Nicole Katz is not exactly her life’s goal. A year from now, she will be remembered only as what’s-her-name, that brunette receptionist we had a while back, name started with a V, maybe? And she will undoubtedly remember me as the short, chunky chick who wore all those strange hats and weird clothes.

Our relationship is based on mutual dismissability.

I yank open one side of the double glass door and walk into the showroom. Which, I observe on a sigh, has been visited in my absence by a small but potent explosive device. Rumpled, discarded samples and fabric swatches obliterate every pseudo-Chinese surface; Joy and leftover cigarette smoke duke it out for air rights. Nikky’s personal handiwork, would be my guess. The devastation is even more grotesque in the harsh winter daylight blaring through the wall-to-wall windows overlooking the Hudson.

The woman is a total nutcase, but she’s a successful nutcase.

“Where is it, where is it?” I hear the instant the door shooshes closed, cutting off Valerie’s next “Ohmig—” Before I can answer, Jock, the draper, lunges at me, snatching the box from my hands with only a glancing leer at my wool-swathed chest. “You got a size 8, right?”

Having done this at least a dozen times in the past year, I do know the drill. “Yes, Jock,” I say, yanking off my hat and shrugging out of my father’s camel topcoat, then one of his Pierre Cardin suit jackets (both altered to fit me), wedging the lot into the mirrored closet next to the showroom doors. I tug down the hem of one of my mother’s Villager sweaters, circa 1968. The dusty rose one with the ivory and blue design across the yoke. Starr has already informed me she wants it when she gets big. We’ll see.

My desperately-needs-a-trim layered hair crackles like a miniature electrical storm around my head. My Telly Monster imitation. This does not stop Jock from grabbing me, plastering his (not exactly impressive) crotch against my hip and planting a big, sloppy kiss on my cheek. Then he’s off to do what a draper’s gotta do. I hope, for his sake, he got more out of our little encounter than I did.

Oh, Giaccomo Andretti’s basically harmless, his lothario complex notwithstanding. He’s just a bit doughy and married for my taste. And his view of his skills as a draper is a tad skewed. Jock sees himself as a world-class pattern maker. That he hasn’t draped an original pattern since Dinkins was mayor is beside the point.

Not that the Versace will be recognizable once its progeny have Nikky’s label in them. She’s not stupid. The lapel will be wider or narrower or ditched altogether; the skirt will be longer or shorter or slit up the back if this one’s slit up the sides; the fabric will be a print if this one’s a solid or solid if this one’s a stripe, silk instead of linen, a fine wool instead of gabardine.

In other words, this so-called “designer” doesn’t have an original idea rattling around underneath her Bucks County Matron silver pageboy. Her “classic” fit is derived from, quite simply, other designers’ slopers.

Yep. By three o’clock this afternoon, Jock will have carefully dissected the Versace and traced the pattern from it. By noon tomorrow, Olympia, Jock’s best seamstress, will have so carefully reconstructed it no one will ever know it was apart. And by the next morning, I will have returned said suit to the salesgirl, with the sorrowful explanation my sister didn’t like it, after all.

And for this I spent four years at FIT.

Divested of my contraband goods, I hie myself to what passes for my office this week—a banquet table crammed into a corner of the bookkeeper’s office. Apparently my boss can’t quite figure out what I do or where to put me. She only knows she can’t do without me. Or so she says. Which is fine by me. Making myself indispensable is what I do best.

And yes, I’ve asked for an office. Repeatedly. Nikky keeps saying, “You’re absolutely right, darling, I’ve simply got to do something about that….” and then she promptly forgets about it.

Before you ask, “And you’re here why?” two words:

Benefits package.

A stack of new orders awaits me. In Nikky’s completely indecipherable handwriting. Of course, even if the woman weren’t writing in some ancient Indo-European dialect, since she routinely leaves out things like, oh, sizes and colors…

At least, these seem to be mostly reorders. So in theory, if I look up the stores’ original orders, I should be able to figure it out.

In theory.

Long red nails a blur at her calculator, Angelique, the bookkeeper du jour, doesn’t even glance over. “Thought you’d like that,” she says in her Jamaican accent. Nikki is nothing if not an equal-opportunity employer. In the past three months, we’ve had one Italian, one Chinese, and two Jewish bookkeepers of various genders and sexual orientations. And now Angelique, who I give two more weeks, tops. Especially as her crankiness indicators have been rising quite nicely over the past few days. It takes a special person to work here. Sane people need not apply.

“Nikky said to tell you Harry needs these ASAP so he can figure out the cutting schedules and get them to the subs.”

The subcontractors. Better known as the sweatshops that permeate the relentlessly drab real estate over on 10th and 11th Avenues, filled with seamstresses who speak a dozen different languages, none of which happen to be English. Skirts that retail for two-four-eight-hundred bucks, cut out by the dozens by powersaws on fifty-foot long cutting tables, stitched together by industrial sewing machines that sound like 747 engines, for which the sub gets a few bucks a skirt. Which is not what the seamstresses get, believe me. But hey—Nikky can say her products are American-made.

Of course, I can’t sit at my ersatz desk because my chair is piled with samples dumped there by God-knows-who. So I gather them up—from the current fall line, we’re all sick to death of them—and haul them back to the showroom, thinking maybe I should straighten out the showroom before Sally, Nikki’s saleswoman, sees it.

“Je-sus!”

Too late.

I shoulder my way through the swinging door, my arms full, to be greeted by large, horrified blue eyes. Sally Baines is the epitome of elegant, with her softly waved, ash-blond hair and her restrained makeup. Today our lovely, slim, fiftyish Sally is tastefully attired, as usual, in Nikki’s (cough) designs—a creamy silk blouse tucked into a challis skirt in navy and dark green and cranberry paisley, a matching shawl draped artfully over her shoulders and caught with a gold and pearl pin.

“An hour, I was gone.” The words are softly spoken, precisely English-accented. “If that. How can she do this much damage in one bloody hour?”

This is a rhetorical question.

“Come on,” I say, hefting the samples in my arms up onto the rack, then turning to the nearest mangled heap. “I’ll help.”

I hear the ghosts of anyone who’s ever lived with me laughing their heads off. Okay, so I’m not exactly known as the Queen of Tidy.

Just as Sally and I are cleaning up the last of the debris, in this case lipstick-marked coffee cups and full ashtrays, Nikki sweeps in through the doors, swathed in Autumn Haze mink and looking as fresh as three-day-old kuchen. She scans the now-clean room (I’m brought to mind of those insurance commercials where the destruction is undone by running the film backwards), then beams at us as much as the Botox will allow.

“You two are absolute angels,” she says, sweeping over to me to give me a one-armed hug. “Angels. I would have straightened up myself later, you know that—”

Sally and I avoid looking at each other.

“—but I got stuck at lunch with my attorney and time just got away from me. Did you get the suit? Is Harold here? Did my daughter call?”

“Yes, I don’t think so, and not that I know of,” I said, wondering why she doesn’t ask Vanessa or Virginia or whatever the hell her name is, since, um, she’s the one paid to answer the phone?

Harold, by the way, is Nikky’s husband. You’ll undoubtedly meet him later. Lucky you.

Nikky goes on about whatever it is Nikky goes on about for another thirty seconds or so, then sweeps into the back to assuredly wreak more havoc, leaving a zillion startled molecules in her wake. Ten seconds later, the yelling starts.

So Harold is here. He has a teensy office, way in the back (where all good bogeymen live) just large enough for him to run his own business from. And what business might that be, you ask? Okay…picture some Lower East Side bargain emporium, racks and racks of sleazy little tops for $5.99. Those are Harold’s. He actually hires a—picture quotation marks drawn in the air—designer to crank out these things, which are then produced someplace where monsoons and leeches are taken seriously. We all try to ignore him, but unfortunately he periodically emerges from his lair, snarling and snapping, to fight with his wife and piss me—and everybody else—off. An occupation in which he is apparently presently engaged.

Sally bequeaths me a sympathetic glance as I haul in a breath, close my eyes and reenter the Twilight Zone. However, I think as I return to my cubbyhole and begin logging all those orders onto the computer so I can print out the cutting list so Harry, our production manager, can order fabric and send specs over to the subs, compared to some jobs I could name, this one is downright cushy. There is that medical plan, for one thing. And I tell myself, as I often do, that one must endure a certain amount of indignity on the way to the top, if for no other reason than to be able to enjoy inflicting similar indignities on those underneath you when you get there.

It’s all part of some divine plan. Or at least, part of my plan. After five agonizing years on salesfloors and in buyer’s offices, Seventh Avenue is a major, major step. “Assistant to name designer,” the ad had said.

Yeah, well, she has a name all right. But then, so do we all.

Actually, Nicole isn’t her real name. My guess is Rivkah Katz didn’t quite project the image she was looking for. Not much call for babushkas in the Hamptons. But for all her hard work (cough), for all her stuff isn’t cheap (as opposed to her husband’s stuff, which redefines the word), you won’t find Nicole Katz Designs in Bendel’s or Barney’s or Bloomie’s. You won’t find Gwyneth or Renee or Julia sporting her togs. Anna Wintour isn’t wetting her pants to get a sneak peek at her fall line.

You will, however, find her clothes tucked away in Better Sportswear in Macy’s or L&T or Dayton’s, in boutiques catering to well-off women of a certain age. You might catch the broad-stroked sketches splashed across a full page in the Times twice a year, showcasing her pretty silk blouses and fine wool skirts; a cashmere twinset; a suit, suspiciously familiar. Pricey enough to be taken seriously by many, but not pricey enough to be taken seriously by those who—supposedly—count. No doubt about it, Nikky Katz is solidly second tier. But she’ll never be first tier, never have her clothes mentioned in the same breath as Prada or Klein (either one) or Versace.

The thing is, though, she’s in a damn good position for someone whose talent is limited to sticking with the tried-and-true. And for knowing which designs to knock off. Hey—the woman’s raking it in hand over fist, producing a stable product that continues to sell by dint of its not being subject to the whims of the rich, bored twenty-somethings that fuel the upper echelons of the fashion industry. Her customers depend on her to give them what works, and in twenty years, she hadn’t disappointed them yet.

All in all, not a bad gig. Especially as she’s all but invisible, way up here in her snug little niche, her customers clinging to her like bees to a hive. Neither the big designers nor the young and hungry newbies want her market share. Ergo, in one of the most fatuous, unpredictable, unstable industries in the world, Nikky Katz’s business is as solid and safe as Fort Knox.

Which is why she’s my idol.

chapter 2

Now before you say, “You are one totally sick puppy,” hear me out.

God knows, I don’t emulate the woman personally. But you better believe I admire her success. And I count myself blessed for the chance to suck every bit of knowledge about the biz out of her. Because while I may be totally over the moon about fashion, I can’t design my way out of a paper bag any more than she can. And I figure, hey, if Nikky Katz can make it, then there’s hope for me.

Granted, I’ve known how to sew since I was five. I can make up anything from a pattern, and I’m a magician at alterations, if I say so myself. I can rework and adapt with the best of ’em. But let me tell you, I’ve got more filled sketchbooks than you can possibly imagine crammed in my closet at home, without a single creative, original, hot idea among them. In fact, my design teachers at FIT kindly suggested I switch to merchandising, because I was wasting their time and my money otherwise.

So, yep, forget the designing. Somebody else can design…and I’ll do the marketing. Because that, I am good at. Yeah, I know, most people would consider drawing the pretty pictures and playing with the fabrics the “fun stuff.” But see, it’s the whole philosophy of fashion that fascinates me so much: whatever it is that drives people—women, primarily—to wear what they wear. How we costume ourselves, choosing each article of clothing, each accessory, to telegraph to the world who we are. Or who we think we are. Or, in many cases, who we’d like to be. Even the most casually donned attire says something, if nothing other than that the wearer doesn’t give a damn.

For me, the rush doesn’t come from designing a garment, but from figuring out why it appeals. I mean, that scene back at the store? Honey, watching all those women get worked up got me worked up. Like fashion porn. And I got a real early start—not to mention all the cute shoes I wanted—hanging out at my family’s shoe store in Queens when I was a kid. I learned early on that the relationship between a woman and what she chooses to put on her body is a sacred thing. And I knew I had to be part of it, even if I was woefully untalented.

So. Working for Nikky Katz is my dream job, for the moment. And until she figures out what to do with me, I get to do a little bit of everything. I can deal with a little yelling, a little craziness, now and then if it helps me reach my goal….

The phone rings on Angelique’s desk. She answers it, says, “It’s for you.”

One day maybe I’ll have my own desk with my own extension.

One day maybe I’ll be able to get a phone call without my heart clogging my throat.

But it’s nothing scary, only Tina, my best friend since she, her mother and two older sisters moved across the street from us when I was five. Tina’s married to my other best friend, Luke Scardinare. His family—he’s one of six brothers—and mine have lived next door to each other my whole life. Luke used to make my life miserable on a regular basis and I’d kill with my bare hands anybody who even thinks about bad-mouthing him. Which is the same way I feel about Tina, even though she didn’t make my life miserable on a regular basis.

I realize she’s asking if we can meet up at Pinky’s, a bar a couple blocks from where I live. “I need to talk,” she says, her voice giving nothing away, which is unusual for Tina because usually her voice gives everything away. Twelve years ago she says to me, “Does this lipstick make me look slutty?” and I instantly knew she and Luke had done it for the first time.

“Sure, okay. What’s up?”

“I’ll tell you when I see you. Seven okay?”

“Eight, eight-fifteen would be better.” Her Queens accent calls to mine, buried deep beneath the Manhattan persona I apply like makeup every morning. “I gotta read to Starr at seven.”

“Couldn’t you skip it, just this once?”

Tina and Luke don’t have kids, even though they’ve been married for five years already. They don’t talk about it, and I don’t pry, but I know Luke’s mother, Frances, wonders. Tina’s mother is blessedly no longer close enough to inflict direct damage. Although my guess is Tina and her sisters will be mopping up the fallout from their childhood for some time. On the outside, Tina’s your typical smartmouthed Outerborough Broad; on the inside, thanks to Dear Old Mom, she’s a tangled mass of insecurities.

“No, I can’t skip it, I promised her this morning.”

There’s a tiny pause, like when a reporter halfway around the world doesn’t answer the New York anchor’s question right away. “Okay, fine,” she says on a sigh, and hangs up. I’m tempted to feel guilty, until I realize if it was that important I would have heard it in her voice. Or she would have been sobbing and incoherent, like she was that time Luke and she broke up their senior year. Of course, they were back together before the weekend was out, although not before Tina had gone through three boxes of tissues and two pans of brownies. Not a fun weekend. Well, except for the brownies, which she shared.

Before I have a chance to cancel my guilt trip, I get another call. Angelique hands it over. Judging from her expression, I’m guessing she’s finding this an interesting way to break the afternoon’s tedium.

It’s Luke this time. “You gonna be home tonight? I need to talk.”

Gee—you don’t suppose these two calls are related, do you? And why, out of the approximately eight million relatives these two have between them, do they pick me to help them sort through whatever it is this time?

Because they always have, that’s why. Because they know they can trust me.

I’m quiet for too long, I guess, because Luke says, “Shit— Tina already called you, huh?”

And the cornerstone of my trustworthiness? An ironclad policy of not lying. Unless I absolutely have to. “Uh…yeah. She did.”

That gets another “Shit” and a very heavy sigh. Then: “She say anything?”

“No.”

“You sure?”

“Yeah, I’m sure,” I say, thinking even admitting her wanting to talk is probably a confidence violation. However, telling him we’re meeting up at Pinky’s definitely is. I can’t help it, I’ve always been protective of Tina. Probably more than is good for her, I know, but I can’t help it. Although my wanting to shield her from life’s doo-doo is nothing compared to how Luke treats her. The term “spun glass” comes to mind.

“Hey,” I say. “What’s going on?”

“Gotta go, I’ll talk to you later.”

And he hangs up.

Luke and Tina. My very own reality show. With extra cheese.

“He sounds sexy,” Angelique says after I hand back the phone.

Sexy? Luke? Yeah, I suppose. In that heavy-lidded Italian thug kind of way. Not that Luke’s a thug, but put him in tight jeans and a T-shirt, dangle a cigarette from his lips, put lifts in his shoes, and you got it.

“Married friend.”

“How married?”

“Very. Five years. To the woman who called earlier, in fact. They’re nuts about each other, have been since ninth grade.”

“Huh.” Some keys click. “Bet that voice sounds even better in the dark.”

She may have a point. However, as I’ve been listening to Luke since we were communicating in monosyllables and grabbing our Gerber teething biscuits out of each other’s hands, I can’t say as his voice has made much of an impression on me. Okay, maybe once or twice, in a weak, deluded moment, but not for a long time.

A very long time.

“He’s a plumber,” I say, don’t ask me why. “Well, plumbing contractor. Works for his father.”

“Hey. Plumbers make good money. And they’ll never be out of work.”

This is true. “But he’s married,” I repeat, realizing this is the first real conversation Angelique and I have ever had. And possibly the last, if I win the how-long’s-she-gonna-last pool. “To my best friend.”

After more paper shuffling and clicking, Angelique says, “So. You have a boyfriend?”

I don’t have the time or energy to deal with a puppy, what on earth would I do with a boyfriend? This, however, doesn’t stop images from springing to mind. Involving things one might do with boyfriends and various appendages attached thereto. I quickly, if regretfully, push the images away.

“Not at the moment. My old one broke and I never got around to replacing him.” I then add, tempted to look around furtively and lower my voice, “I have a daughter, though.”

Her dark eyes light up. “Me, too! How old is yours?”

“Five going on forty. Her birthday was a couple of days ago.”

“You got a picture?”

Do I have a picture, is the woman nuts? Like CIA operatives in a clandestine meeting, we drag out our wallets and compare children. I compliment Angelique on hers, already a knockout at seven. But let’s be honest here, Starr is going through what I hope to hell is an awkward phase. God knows, nobody’s going to mistake me for Catherine Zeta-Jones—even at her most pregnant—but my baby’s skinny, she’s nearsighted (like her mama), she’s got all this frizzy black hair (like her Great-Gran Judith)…poor thing looks like a myopic johnny mop.

“She looks very…sweet,” Angelique says at last.

Sweet is not the word I’d choose to describe Starr, but my heart cramps anyway because I’m crazy in love with her. Even if she totally freaks me out at times. “Thanks,” I say softly.

It’s kinda nice, being able to talk about my kid at work. Not something I ever thought about when I was really single. I mean, please—is “single mother” an oxymoron or what? “Single” implies “alone,” and God knows, the one thing you’re not once you’ve got a kid is alone. Anyway, it’s not as if nobody knows about Starr, it’s just that women who aren’t mothers aren’t real interested in hearing about your kids. Not that I blame them. If you’re not living it, it’s kinda hard to understand the excitement generated by that first dump in the toilet. Still. It gets old, pretending your children basically don’t exist while you’re at work. As if they’re houseplants or something. Because, you know, we couldn’t possibly be a hundred percent focused on our work if we’re also worrying about our kids. Never mind that some of us can actually do two things at once. And do them well, to boot.

Nikky suddenly bursts into the office, a frantic expression overriding the Botox. “Ellie! Darling! Come quick! You have to help me!”

Exclamation points whiz past my ears. “Sure, I’ll be there in a sec, right after I get this cutting list done—”

“No! This can’t wait! The Volare rep just called and said the company’s discontinued the floral print! Which means I have to pick a substitute! And I’ve got stores expecting those sundresses in six weeks!”

Even I can see there’s no turning off the panic button until the crisis has been resolved. Now, you might ask (understandably enough) why the woman can’t just pick a substitute fabric and be done with it. Well, there are several reasons, number one being—as you may have noticed—Nikky’s brain shuts down in a crisis. Two, since several hundred thousand dollars’ worth of orders are riding on this particular item, the substitute fabric has to be chosen very carefully. And three—and this is something almost no one else knows—Nikky is color-blind.

Yes, it’s very rare in women. And she only has trouble distinguishing greens, which is why you’ll never see any green items in her line. But she wanted a bold rose print for this particular model, and roses have leaves, and leaves are green (at least, they were in this print), so she had to rely on someone else to “see” the green for her and make sure it wasn’t some ugly baby poop color or something. But I’d really like to get home on time tonight, which means I could do without the handholding routine. However, if I don’t help her, Harold will get involved, and God knows—

“Problem, Nik?”

—nobody wants that.

Nikky schools her features before turning to her husband. “Nothing, just a little detail I need to work out with Ellie.”

Droopy-lidded eyes give me the once-over; it’s like being scrutinized by a jowly Kermit. Sparse strands of no-color hair cling to his liver-spotted scalp like drowning men to a life raft; underneath a white dress shirt and pleated suit pants quivers a large, amorphous body. I practically have to pin my finger to my lip to keep it from curling.

“It’s that goddamn Volare, isn’t it? I heard on the extension—”

A real jewel, this guy.

“—they pull a fast one on you, what?”

“They didn’t pull a ‘fast one,’ Harold,” Nikky says wearily, “they just discontinued the fabric for one of the items, it’s no big deal—”

“Goddammit, Nikky, what the hell’s the matter with you? I told you to dump those shysters, didn’t I? Right? Didn’t I tell you that, after the last time they pulled this shit? How many times you gonna let those sons of bitches do this to you before you find the balls to take your business elsewhere?”

“Oh, get over it, Harold!” Nikky crosses her arms and meets his gaze dead-on. When push comes to shove, she can stand up to him, I’ll give her that. But at what price? “I’m not going to destroy a twenty-year relationship simply because they canceled a fabric on me!”

“Why do you let these sons of bitches screw you to the wall over and over, Nikky? Why? I mean, Jesus—when’re you gonna stop acting like a woman and start acting like a businessperson?”

Silently, she stares him down for several seconds, then turns to me. “Come on, Ellie—”

“You stay right there,” Harold orders, jabbing a finger first at me, then his wife. “You’re gonna get on that phone, and you’re gonna tell those sons of bitches they will honor that order or that’s the last one you’ll ever place with them! Or better yet, maybe I’ll let Myron give ’em a goose, let ’em know they can’t get away with this shit—”

“You even think about calling the lawyer and you’re a dead man! This isn’t your business, Harold Katz, it’s mine! And I will run it as I see fit!”

“Right into the ground, the way you’re going! And since I sank every dime I had into this harebrained scheme of yours, I’ll stick my nose in whenever I damn well like!”

By this point, I half expect to see the hair raised on the back of her neck. Mine sure as hell is. And you should see Angelique’s eyes.

“And since I paid you back—three-fold—since then,” Nikky says, barely above a snarl, “butt the hell out.” Her gaze deliberately shifts to mine. “Ellie?”

I rise and follow, managing not to go “Ew, ew, ew” when I have to brush past the man. Who watches us, his little amphibianesque eyes burning a hole in the back of my head, before I eventually hear his footsteps retreat to his office.

How—why—the woman puts up with the man is beyond me.

Especially as I notice, when we reach her office, how shiny her eyes are.

I never know whether I should say anything or not, whether she’d welcome my sympathy or spurn it. Pride’s an unpredictable thing. But while Nikky might be addle-brained and totally disorganized, at heart she’s not a bad person. Medical plan or no, I wouldn’t still be here after a year if she was. And nobody deserves to be talked to like that. Ever. Well, except Harold. Or your average despotic dictator.

Then she pulls the substitute swatches out of the FedEx envelope with shaking hands, and my conscience shoves me from behind.

“Nikky, I—”

But she shakes her head, cutting me off.

“I don’t…” She clears her throat, then smoothes her hand over the polished cotton. The roses are similar to the original, if a bit smaller and redder. But the green is this yucky olive that brings to mind things nasty and distasteful. “I don’t think this one’s too bad, what do you think?”

“I think…” Oh, hell. “I think you should call the rep and tell him you’re holding them to the original contract. Or you’ll sue.”

Nikky’s head jerks up, the ends of her silver hair brushing her silk-clad shoulders. In her own, paralyzed way, she looks as flabbergasted as I feel.

“You agree with Harold?”

Since I’d always figured I’d have a better chance of agreeing with Rush Limbaugh than Harold Katz, you can image what this revelation is doing to my insides. “I think he…has a point. Even if I do have issues with how he makes his points.”

That gets a short, airy laugh. “You don’t have to be so diplomatic.”

“Yes, I do. I need this job.”

Another laugh, this one with a little more substance to it. Nikky sinks into her chair, a high-backed swivel number in a gorgeous flame stitch fabric. She twists the cap off a bottle of designer water, then digs a pill box out of her purse. Hell, if I had to live with Harold, I’d probably be scarfing down whatever the la-la drug of choice is these days like M&M’s.

She takes another swallow of water and replaces the cap. “Why?” she says, all smiles. Wow. Must be good stuff. “Why do you agree with Harold?”

“Because—” I pick up the substitute swatch. “Because this is total crap compared with the original. Because something tells me they are pulling a fast one. I mean, think about it—why should they yank the pattern when you’ve got how many hundreds of yards on order? Unless—”

“Unless a bigger designer saw it and pulled rank. So they’re only telling me it’s no longer available. I have figured that out.”

She doesn’t seem particularly surprised. Or disturbed. I, however, am both. Her lips curved at my obvious distress, she gestures for me to sit, then takes a cigarette case from her desk; five seconds later she’s calmly blowing smoke away from me. “Darling, in the scheme of things, six hundred yards is nothing. Especially if another house comes along and orders twice, maybe even ten times that. I don’t know….” A stream of smoke cuts through the air. “I can’t really blame the supplier for wanting to make the other guy happy, right?”

“But you’ve been a loyal customer for twenty years….”

“Because they’re willing to work with me and my smaller orders.” She leans forward. “Sure, there are other fabric houses I’d rather use. You think they’d give me the time of day?” The cigarette smoke stream jumps as she sinks back against the chair. Frowning, she brushes an ash off her left breast, then looks at me. “I’ve got more clout than some, less than others.” A shrug. “You learn to compromise. Pick your battles. Contrary to what Harold thinks, pitching a fit isn’t going to endear me to them. Or keep me in business.”

“So you just…back down?”

“I prefer to call it playing smart. However…” Her fingers brush the fabric, then shove it away, as though it’s toxic. “I may be second best, but I’m not stupid enough to pick something that’s gonna make my dress look like the knockoff—”

Somehow, I manage to keep a straight face.

“—so we start over.” Squinting, she crams the cigarette back in her mouth and says around it, gesturing toward the teetering piles on the long table over against the far wall, “Hand me the Volare book, wouldja? Let’s see what we can come up with.”

I do, but as I root through the rubble, I have to ask, “But isn’t it a little late to switch fabric on the stores now?”

“Like they care. You find it yet?”

I have, miraculously enough. I hand it to Nikky, who thunks it onto a six-inch pile of jumbled papers. Where they’d come from, I have no idea, since I’d just straightened up yesterday. “So,” Nikky says, the cigarette dangling from her lips, pool-shark fashion, “We chuck the roses altogether and go with…” She flips through the book. “A plaid, maybe? Or something completely different, like…” With a grin, she turns the book around, yanking the cigarette out of her mouth with a flourish. “Hats. These are cute, right? Is there any green in it?”

I shake my head. She grins.

“Yeah, hats. It’s brilliant.” With a wink, she grabs her phone and punches a single digit. Ten seconds later she’s going, “Lenny! Nikky. How are you? Good, good… Listen. Here’s the deal. Forget the roses…yeah, yeah, I don’t like this sample you sent over, it’s very Target, you know what I mean? So instead, send me swatches of…” She randomly flips through the book, rattling off a dozen numbers. Then, as if she couldn’t be bothered, “And this cotton with the hats…number 2376, just for the hell of it. They all available? You’re sure? Great. And I can have the swatches tomorrow?” She gives me a thumbs-up. “You’re a doll, Len. Take it easy, now.”

She hangs up, stubs out her cigarette, and smiles at me.

“I don’t get it,” I say.

A low laugh rumbles from her throat. “I know everybody thinks I’m a ditz. Including you, you’re just nicer about it than most. But let me tell you something…” Again, she leans forward, and I see in her eyes exactly why she is where she is. “People let their guard down if they think you’re stupid. Then they’re the ones who do the stupid stuff, you know what I mean? Lenny has no idea which of these I’m really interested in. And by the time I clue him in, it’ll be too late for anybody else to get one up on me again. And I think I like the hats better, anyway.”

I think she’s kidding herself. But hey, not my business.

“Anyway, so when the swatch comes, you’ll scan it and send it to the buyers, tell them the other fabric came in flawed and this is what we’re switching to, and that’ll be that—”

Her eyes lift over my head, to her office doorway. The hair on the back of my arms bristles.

“Problem solved?” Harold asks.

“Yes, Harold,” she says, then adds, “By the way, Marilyn left a message on my voice mail, said seven was fine, she’d meet us at the restaurant.”

“How’d she sound?”

“Who can tell over voice mail?” Nikky says with a shrug. But her mouth thins in concern. “In a rush, though. As usual.”

“She gets that from you, you know. Never knowing when to stop.”

That’s okay, folks, don’t mind me.

“Mar’s a big girl, Harold. She doesn’t need Daddy clucking over her like some Jewish mother.”

“Yeah, well, maybe if the Jewish mother she’s got was doing her job, I wouldn’t have to,” he says, then walks away.

I get up, making noises about getting back to my work so I can leave on time tonight—

“He would die if I left him,” Nikky says softly.

“Um…what?”

“I know what you’re thinking. That you can’t understand why I put up with his crap. Well, I put up with his crap because he needs me. And what can I tell you, it feels good to be needed.”

Okay, fine, I can buy that. To a point. Otherwise, how could I constantly deal with Tina and Luke’s string of crises? Why would I be here, for God’s sake? But there’s a difference between being needed and getting off on self-flagellation. And before I realize it’s coming, I hear myself say, “But the way you let him yell at you—”

“That’s right. I let him yell at me. Because I make the money and I bought the house in Bucks County and I’m paying for our daughter to go to NYU and yelling at me is the only way he can still feel like the protector.”

Right. A protector who constantly tears down the person he’s supposed to be protecting? I’m sorry, but this is seriously not working for me.

“Oh, ditch the outraged expression, Ellie,” Nikky says with a gravelly laugh. “It’s all…posturing. He’s never laid a finger on me. And he did put everything he had in this business when I started out. Everything. If I live to be a hundred, I will always owe him for that.” Then she looks at me, hard, like a teacher awaiting my response on an oral exam.

“So…you’re happy?”

Her laugh startles me. “God, you’re so young,” she says, and probably would have said more if her phone hadn’t rung just then. Grateful for the interruption, I scurry out of her office and back to my cubby-of-the-week, wondering how fast I can get my work done, wondering what’s up with Tina and Luke, wondering why a woman like Nikky Katz would be so willing to settle for…whatever it is she’s settling for.

And thanking my lucky stars I’m not like that.

chapter 3

The bad news is, it takes me nearly an hour to make the trek on the A train from midtown Manhattan to Richmond Hill. The good news is, our house is only a few blocks from the subway stop. And it’s at the end of the line, so if I pass out—which has happened more than once—the conductor usually gives me a poke to make sure I get off.

Except for a few months, I have lived my entire life in this neighborhood. I don’t hate it, exactly, but the place is like quicksand. The harder you fight to get out, the more it sucks you back in. I’ve watched too many of my friends from high school settle into virtually the same lives as their parents had, even if they moved to another neighborhood, to Ozone Park or Forest Hills or Jamaica. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, as long as you’re sure that’s what you want.

I don’t.

And yet my entire body betrays me, sighing with relief the minute I set foot on Lefferts Boulevard. For good or ill, this is home, has been my entire life, and there’s something to be said for leaving the stresses of the city behind on the train. I can almost hear them, banging and howling as the train pulls away on the elevated tracks overhead.

I breathe in the bitterly cold, damp air as I clomp along, my toes freezing in these damn shoes (you will rarely find me in flats—without heels, I look like I’m standing in a hole). Pushing out a crystallized sigh, I pass the duplexes that were pretty much all single family homes when I was a kid, now almost all turned into apartments. Cooking smells accost me as I walk, cruelly taunting my empty stomach—East Indian, Caribbean, Asian stir-fries, the occasional whiff of something solidly middle European. We live near the end of the block, our pair of semidetached houses the same baby blue with white trim as they have been ever since I can remember. Twin front yards flank identical stoops, each just about big enough for ten blades of grass and a tub of marigolds or impatiens in the summer, although the Nyugens installed a small, gurgling fountain on their side last summer. We have a garage, in which resides a 1979 Buick LeSabre that my grandfather drives maybe three times a year, that I drive when there’s absolutely no way I can avoid it.

After my grandfather returned from the Korean War, when my father was six, he used a VA loan to buy the half that Leo, Starr and I live in now. When the Goodmans next door decided to move to Jersey in ’73, Nana and Leo bought the other side for my parents and sister, who was then a year old. The rationale was, since my father and grandfather were now partners in the shoe store over on Atlantic Avenue, why not live close to each other, too? I’ve often wondered how my mother felt about this arrangement, especially as she and my grandmother did not get along. Of course, my grandmother never got along particularly well with anybody, save for maybe my sister.

I pass Mrs. Patel’s, across the street and a couple houses down from mine, trying to remember when she first put up the plastic flamingo. Junior High, I think. Brightly illuminated by a pair of spotlights, he leans rakishly in her speck of a yard, still dressed in his Santa Claus hat.

The windows in both of our houses are lit up; a muted salsa beat throbs from the Gomez apartment, from what had been our living room when I still lived there. My gaze shifts to the other side, where I live now with my daughter and grandfather. And out of nowhere the thought comes, What if you never leave this house? What if you end up marking every season for the rest of your life by whatever outfit Mrs. Patel’s flamingo is wearing?

My blood runs cold. Home is all well and good, but your childhood home is someplace you’re supposed to be able to come back and visit, not rot in—

“Hey, you! You forget where you live or what?”

That’s Frances. Scardinare. Luke’s mother. Figures she’d get home the same time as me. Not that I don’t love Frances, but sometimes there just isn’t room in your head for anybody else.

But I smile anyway. Between Mrs. Patel’s spotlights and these damn halogens, the street’s lit up practically like it’s daytime. “Just trying to figure out if I’ve got the energy to haul my butt up these stairs, that’s all.”

“I know what you mean.” Frances passes her own stoop, her long, thin arms weighted down with several grocery bags. Let me tell you, when I hit my late fifties? I should look half as good as Frances does. Not that I will, considering she’s a good head taller than I am and has all this incredible bone structure. And legs. Even after six kids, she’s still a size ten. Without dieting. And since she started earning her own money selling real estate a couple years ago, she dresses well. Has her hair done at Reggio’s once a month, too, this really flattering, layered style that sets off her big eyes and high cheekbones. And somehow, it stays looking good between cuts. Me, my hair already looks like it’s growing out by the time I’ve tipped the shampoo girl.

Still clutching the bags, Frances holds out one arm for a hug, her wide mouth splayed in a huge grin. My heart does a little skip: when my mother died and my grandmother didn’t seem any too hot on the idea of filling the gap in my life, Frances did, like a mother cat taking on an extra kitten. The woman scares the snot out of me, but I would not have survived my teenage years without her. Or at least, I doubt anyone else would have.

She lets go, a frigid breeze toying with her dark hair. “Did you hear? Petie and Heather are finally getting married!”

Pete’s—nobody, but nobody besides Frances can get away with calling him “Petie”—the brother after Luke, a year younger. Heather Abruzzo was three years behind me, I think, but her older sister Joanne used to hang out with Tina and me from time to time when we were teenagers. “No! When?”

“June, when else—?”

My front door pops open; with an affronted, “Geez, finally!” my daughter shoots out of the house and down the steps to the icy sidewalk, fusing to my hip. I hug her back, noticing she’s in her nightgown and Elmo slippers.

“Get back inside, you’ll catch your death!”

Through her glasses, reproachful, and slightly pitying, brown eyes roll up to meet mine. “You don’t catch colds from the cold. You catch ’em from germs.”

I do know this, actually. But it’s unnerving hearing it from someone who’s still short enough to ride the bus for free.

“Maybe so.” I scoop her up into my arms—it’s like picking up a dust bunny, she’s so light—and kiss her on her cold, freckled little nose. I want to eat her up, even as the thought that we’re stuck with each other forever still gives me pause. “But you could get frostbite,” I say, “and that would be a lot worse, ’cause then your toes’d fall off.”

That gets a considering look. I can tell she doesn’t quite believe it, but is this really a chance she wants to take?

“Go back inside, Twink,” I say, putting her down, feeling like a fraud, wondering if I’d feel less like one if she’d been planned. If I could tell her the truth about her father. If I knew the truth about her father. “I’ll be up in just a minute, I promise.”

“Swear?”

“Swear.”

She trudges back up the stairs, a tiny, shivering figure in flowery flannel, only to turn and threaten me: If I’m not inside by the time the big hand’s moved to the next number, she’s coming to get me.

After the door closes, Frances laughs. Then she says, “You’re getting home kind of late, aren’t you?”

“It’s not seven yet,” I say, but she gives me this reproving stare, her mouth all screwed up, then sighs.

“You work too hard.”

“And you don’t?”

“My kids are grown. Or nearly.” Her five oldest sons are out of the house; the youngest, Jason, is seventeen and probably wishes he was. “It doesn’t matter if I’m not there to cook their dinner.” I laugh, and she rolls her huge, almost black eyes. “Okay, so maybe I never did cook their dinner, but at least I was there. And speaking of dinner—” she shifts her bags to one hand, flexing the fingers on the other “—we’re going up to Salerno’s, you and Leo and the baby should come with us. Our treat.”

Frances and Jimmy are always like this, wanting to take us to dinner, their treat. Of course, my grandfather is just as bad, which gets to be a major headache when he and Jimmy start fighting over the bill.

“Starr’s already in her jammies.”

“So she’ll get dressed again. It’s barely seven. What’s the big deal?”

“Leo did brisket.”

“Which is always better the next day, right? So come on, you look like you could do with a night out. And if you’re there, we might even be able to enjoy our meal without looking at Jason’s sulky face all night.”

An understatement if ever there was one. My needing a night out, I mean, although I know what she means about Jason’s sulking, too. Poor kid. Adolescence has hit him harder than all his brothers combined. Not that the Scardinare testosterone surges didn’t terrorize the neighborhood for several years—there was an eight-or ten-year period when there were at least four teenagers in the house at any given time—but I guess it’s harder on Jason, being the baby and not having his older brothers around all that much. He’s like a walking David Lynch movie—very dark, very weird, with lots of incomprehensible erotic undertones. If I hadn’t baby-sat for him when he was little, he’d probably creep me out.

To further complicate things, I think he has a crush on me. He’s over here constantly when I’m not at work, following me around, his big moony eyes peering out at me through his straggly black bangs, like prisoners who’ve lost all hope. Think Nicholas Cage in Moonstruck, then multiply by ten. And like Cher, I want to smack the poor kid and yell “Snap out of it!”

But I don’t have the heart.

Then I remember, with a sickening thud, the main reason, or reasons, I can’t leave the house tonight: Tina. Whom I’m supposed to meet in a little over an hour.

“Mama!” Starr’s shrill little voice darts out from the doorway. Her hands are on her hips. “The big hand’s moved past two numbers! That’s ten minutes!”

“Another time,” I say to Frances.

She sighs and shakes her head, then turns toward her house, shouting, “Dinner, here, Sunday, Heather wants to show off her ring,” over her shoulder as she goes.

And I head up the stairs, wondering how somebody with no discernible personal life can have so many demands on her time.

An hour later, I’m by the front door, slipping my father’s coat over an outfit more appropriate to Pinky’s—Levi’s, slouch boots (with heels that could double as shishkebob skewers), a dark red vintage mohair sweater I found on eBay for ten bucks. I don’t know why I prefer older clothes to new, other than the obvious fact that I can’t afford to buy new. Nor do I know anybody who can. I mean, I read Vogue and think, chyeah, right. Not that I don’t think some of the stuff is seriously hot, but Jesus. Even if I weren’t a foot too short to wear any of it, by the time I could afford it, I’d be so old I’d look like a freak in it, anyway. I mean, two grand for a fringed skirt shorter than something I’d let my five-year-old wear? Please. And let’s not go anywhere near the six-or eight-or fifteen-hundred-dollar handbags. You’re supposed to be afraid that somebody might steal what’s in your purse, not the purse itself. Or am I missing something here?

So I wear old, cheap and/or free stuff. Mind you, having never harbored a secret desire to look like a bag lady, it’s old, good-looking cheap and/or free stuff. I do have, if I say so myself, a certain flair. For the ridiculous, perhaps, but at least nobody can accuse me of looking like everybody else.

Or around here, like anybody else. Sorry, but I don’t do big hair.

Anyway…by the time I read Starr the next chapter of Through the Looking Glass—interrupted a billion times by her pointing out words she recognized—and did two thorough monster sweeps of her room (there’s a big hairy purple one with a snotty nose and “sticky-outty” teeth who’s been a real pain in the butt lately) and tucked her in, it’s too late to eat, and my stomach is pitching five fits.

My grandfather, who’s been vacuuming the downstairs rooms, glances up from winding the cord into a precise figure eight, over and over, around the upright’s handles. It drives me nuts when I use the machine after he does. I keep telling him, it takes twice as long to do it this way, why not just loop it around the handles and be done with it? All that matters is that it’s up and out of the way, right? But he insists it’s neater the way he does it, that’s the trouble with the world these days, nobody takes the time to do anything carefully.

“You’re going out?” he says, hauling the Eureka out of the room.

“Yeah.” I cram an angora beret over my hair, yelling out, “Just to Pinky’s for a bit. Tina asked me to meet her there.”

Leo returns, plopping down into his favorite armchair and picking up the Nintendo controller. A second later, one of the Mario Brothers games blooms on the TV screen. The game system’s a hand-me-down from some Scardinare brother or other. Leo plays for hours, insisting it keeps his reflexes fine-tuned. “What’s up with her?”

“Couldn’t tell ya.”

He pauses the game to give me a more considering look, although I can’t really see his eyes through the sofa lamp’s glare off his glasses. But I can sure feel it. You have to understand, my grandfather is by no means some shriveled, sunken little old man. Still more than six feet tall, with a ramrod posture he expects everyone around him to emulate, even seated he’s an imposing figure. Age-loosened skin drapes gracefully around features too broad, too crude, to be called handsome, as though the sculptor had been in too much of a hurry to do much more than get the basics down. If he chose to be mean, he would be frightening. As it is, no mugger in his right mind would dare mess with him. Ironic considering that nobody’s a softer touch than Leo. I don’t dare take him into Manhattan—he’d be broke before he’d been off the train ten minutes, giving everything away to every panhandler he saw.

“Did you eat?”

“When I get back, I promise.” I cross the thickly-piled Oriental—in mostly blues and dark reds, to match the overstuffed Ethan Allen furniture my grandmother bought the year before she died—bending down to give him a kiss on his scratchy cheek. Heat purrs soothingly through the registers; the house smells like brisket and freshly washed clothes (there’s a basketful on the sofa, waiting for me to fold) and my grandfather’s spicy aftershave, and all I want to do is crash in my bedroom with a slab of meat large enough to feed Cleveland and watch one of my Jimmy Stewart movies. But instead I’m dragging my hungry, exhausted carcass back out into the bitter cold, because my friend needs me. Because I know Tina would do the same for me.

And has, I think as I hike to the bar, braced against the wind.

I mean, there was that time a couple years ago when we all came down with the flu—I’m talking near-death experience here, not your run-of-the-mill chills and fever crap—when Tina, despite an aversion to illness bordering on the obsessive, basically moved in, force-feeding the lot of us Lipton’s chicken noodle soup and ginger ale for two days and disposing of mountains of tissues like the Department of Sanitation clearing the streets after a blizzard.

Or going back even further, to when we were fourteen and had lied to our families about going to Angie Mason’s for a sleepover. Instead we went to this party at Ryan O’Donnell’s (remind me to never believe anything my teenage child tells me, ever), where I, being basically stupid and having zip tolerance for alcohol, got so drunk I wanted to die. And Tina, who even then could hold her booze like a three-hundred pound sailor, and who also knew if I went home in that condition, I would die, hauled me into the john and forced me to puke, made coffee in Ryan’s kitchen, sat there with me while I drank it, and got me home, shaky but sober, by curfew.

She was also there, at her insistence, when I told Dad and Leo I was going to have a baby.

I push open the heavy wooden door to Pinky’s; hops-saturated steam heat rushes out to greet me like long-lost relatives, defrosting my contacts. Like most neighborhood bars, the decor runs primarily to neon beer signs, dark wood and linoleum. At eight on a weeknight, the place is nearly empty—two or three guys at the bar, staring morosely at the rows of bottles lined up in front of the mirror; a couple talking softly at one of the small tables in the center of the floor. As Madonna yodels from the not exactly au courant jukebox, I take off my hat and gloves, shoving them in my coat pockets as I blink, willing my eyes to adjust to the dim, albeit smoke-free these days, light.

“Hey, Ellie, how’s it goin’?”

My gaze sidles over to Jose, wiping down the bar. A year or so older than me, Jose’s been the night bartender here for the past couple of years. He’s got this whole pit bull thing going. Solid, you know? Not necessarily looking for a fight but up for one should the occasion present itself. In the summer, when he’s wearing a T-shirt, the tattoos are nothing if not impressive. The man on the stool closest to me bestirs himself long enough to give me the once-over. I give him a withering look, then pop out the dimples for Jose.

“Pretty good,” I say, then ask about his wife and kids—they’re doin’ okay, thanks, he says—then I ask if he’s seen Tina.

“Yeah, she came in a while ago. In the back. She looks like shit.”

Hey. If you’re looking for diplomacy, steer clear of Pinky’s.

I spot her in the booth farthest in the back, waving, so I grab a bowl of pretzels off the bar and head in her direction. Except the woman sitting at the table turns out to be Lisa Lamar, who sat next to me in half my classes all through high school and who will be forever after known as not only the first girl in our class to give a boy a blow job, but to pass on her newfound knowledge to a select few of us the following day. An act which solidified my standing in the ranks of the “cool” girls, which means I owe Lisa my life.

So of course we have to do the thirty-second catch-up routine. Only thirty seconds stretches into a good two minutes while she introduces me to her date, some guy named Phil whose unibrow compensates for the receding hairline, then fills me in on Shelly Hurlburt’s parents’ divorce after thirty-six years, could I believe it? (actually, I could) and asks me if I know whatever happened to Melody McFadden’s cousin Sukie, who was supposed to marry that baseball player, whats-his-name (I don’t, but I tell her I’ll ask around, one of the Scardinare daughters-in-law probably knows). Then after noisy hugs and both of us swearing we’ve got to get together, soon, I continue back to Tina.

Jose’s assessment was, unfortunately, not an exaggeration. Even in the murky light, she looks like holy hell.

While neither of us is, or was, a raving beauty—at least not without a lot of help—Tina’s always had a knack for making the most of what she has. No taller than I am, and in no danger of being mistaken for an anorexic, either (we were known in high school as the Boobsey Twins), her eyes might be set too far apart and her nose could use a little work, but with enough lip gloss and a Wonderbra, who cares? And she’s the only woman I know who can actually get away with that cut-with-a-weedwhacker-hairstyle—it hides a narrow scar over her right ear from where her mother threw a bottle at her when she was six—albeit with dark brown hair instead of blond. But tonight we’re talking Liza Minelli, The Dissipated Years.

“I know, I know, I look like crap,” she mutters as I slide into the booth. As usual, she’s wearing black, a heavy knit turtleneck that hugs her breasts. If I know her—and I do—the ass-cupping black jeans and hooker boots are right there, too. And in the corner, I see a hint of fake leopard. Mind you, none of this stuff is cheap. It’s just that Tina never really caught on to the concept of subtle. “I’m two screwdrivers ahead of you, so catch up.”

At least the girl’s getting her Vitamin C. However, since I haven’t eaten, and since that experience at Ryan O’Donnell’s left me bitter and disillusioned, I opt for a Coke. She makes a face and slugs back half her drink. I don’t like this. See, there are two Tinas, Okay Tina and Total Mess Tina. For most of our childhood, she was Total Mess Tina, mainly characterized by the absolute conviction that she somehow provoked and/or deserved her mother’s relentless physical and mental abuse. The girl had the self-confidence of a blind flea. Okay Tina only came out from time to time, like when I was puking up my intestines. It took Luke and me—with the help of various family members—years to send Total Mess Tina into remission. After all our work, relapse is not an option.

But I keep these thoughts to myself. For now.

“So I take it Luke doesn’t know you’re here?”

She laughs, but it’s not a pretty sound. “What, do I look like somebody with a death wish?” She finishes off her drink and gestures toward Jose for another. “Jesus, it’s cold tonight. You sure you don’t want something with a little more zing to it?”

My mother alarm goes off. “Tell me you didn’t drive over here.”

“What are you, the DUI police?”

I decide to leave it for now. But if she’s not walking steadily when we leave, no way is she getting behind the wheel. “So what’d you tell Luke?”

“He thinks I’m grocery shopping.”

I stuff about fifty little pretzels into my mouth at once, then say around them, “You don’t think he’ll get suspicious when you get home with no groceries?” Not to mention the fact that she’s gonna smell like, well, somebody who’s been hanging out in a bar.

“Like I’m not gonna pick up some things before I go home, geez, Ellie. Besides—” she picks up a little white box off the seat beside her “—I made a swing by Oxford’s and picked up a couple of those Napoleons he likes so much.” At my crestfallen look, she smiles and produces a second box, which she shoves across the table. “And éclairs for you.”

I clutch the box to my bosom, inhaling its bakery smell. “I owe you.”

“Yeah, well, I’m gonna hold you to that.”

Jose brings us her drink and my Coke; she picks it up, her wedding rings a flashing blur. Her first engagement ring was so small you had to take it on faith there was a diamond in it. But Luke does pretty well now, I gather. So for their fifth anniversary last year, they upgraded to two carats. Looks real good with the long maroon nails.

I set the box on the seat beside me so I won’t be tempted to rip into it before I get home, then get down to business. “So. What’s going on?”

That gets another long look, then Tina hauls a purse the size of Staten Island onto her lap; before I know it, she’s lit up a cigarette. Which is now a huge no-no in New York bars.

“What the hell are you doing?” I growl across the table. Tina spews out a stream of smoke and holds the cigarette under the table, giving me a look like a she-wolf whose pups have been threatened.

“There’s like nobody here, okay? God, quit being such a priss.” Then, after another quick, surreptitious pull, she says, with no emotion whatsoever, “I’m pregnant.”

We stare at each for a heartbeat or two. But the instant her cigarette bobs to the surface, I lunge across the table and grab it, dumping it into her drink.

“Bitch,” she mutters, calmly lighting up again. Tina’s got these pale blue eyes, like ice. And right now, the look she’s giving me is fast-freezing my blood. Which doesn’t prevent me from going for the second cigarette, but her hand ducks under the table before I can get it. “Chill, for God’s sake. It’s not like I’m keeping it.”

My gaze jerks to hers. “You’re not serious.”

“You bet your ass I’m serious.”

This is too many shocks on an empty stomach. “But Luke…” I lean over, whispering. “You know how much he’s always wanted a kid—”

“And you know how much I don’t. And swear to God, if you tell him, I’ll never speak to you again.”

My eyes burn, and only partly from the smoke. I hate this. Hate secrets. Especially ones that put me in the position of having to lie to somebody. “So why are you telling me this?” I sound whiny and I don’t care. “Why are you making me an accessory?”

“Because I need you to go with me when I…you know.”

“Me?”

“Yeah, you, who else? What, I’m gonna ask my mother? Luke’s mother? One of my sisters? Who else can I trust, huh?”

I feel sick. Who knew being trustworthy could be such a liability?

Tina puffs some more, then says, “God knows how this happened. We always use protection. Always.” I look at her with what I expect is a chagrined expression; I was on the Pill when Starr happened, too, which she knows. Tina sighs. “Sorry. I forgot.”

And because I am doomed to be the sympathetic one, I realize just how much this is tearing her apart. Criminy, she’s shaking like somebody coming off a three-day bender.

“Yo, Tina,” Jose shouts from the bar. “Put out the cigarette, babe, you wanna get my butt in a sling here?”

She blows out a breath and dumps the second butt in her drink, then goes for my pretzels.

“How far along are you?”

Her shoulders hitch. “Three weeks. More or less.”

“Then maybe you should give yourself a few days to think about this. I mean, right now you’re just in shock.”

“No shit. But the last thing I want to do is think about it.”

I know what she means. Oh, boy, do I know what she means. Because thinking about it opens the door to making it real. Makes it harder to not start thinking in terms of “baby.”

“And they say it’s easier the earlier you have it done,” she goes on. “I’m not waiting.”

Arguing with her right now would be pointless. But if she won’t go without me, maybe I can put her off for a couple days, buy some time for her to think this through. Yes, it’s all about choices, but my guess is panic’s short-circuiting her synapses right now. And when you’re freaked is not the time to make a decision that’s going to impact the rest of your life. Especially when there’s somebody else involved, I think with a sharp stab of pain.

“Tina, honey…you didn’t always feel this way. About not wanting kids.”