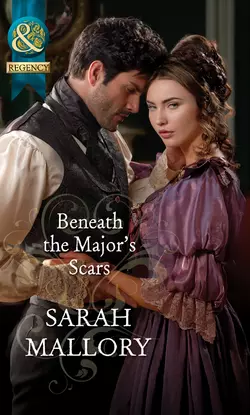

Beneath the Major′s Scars

Beneath the Major's Scars

Sarah Mallory

When a tainted beauty… After being shamelessly seduced by a married man, Zelah Pentewan finds her reputation is in tatters. Determined to rise above the gossip-mongers, Zelah knows she can rely on no one but herself.…MEETS A FORMIDABLE BEAST! But her independence takes a knock when a terrifying stranger must come to her aid. Major Dominic Coale’s formidable manner is notorious, but Zelah shows no signs of fear. She doesn’t cower at his touch as she begins to get a glimpse of the man behind the scars… The Notorious Coale Brothers They are the talk of the Ton!

THE NOTORIOUS COALE BROTHERS

They are the talk of the Ton!

Twin brothers Dominic and Jasper Coale

set Society’s tongues wagging

with their disreputable behaviour.

Get to know the real men behind the

scandalous reputations in this deliciously

wicked duet from Sarah Mallory!

Major Dominic Coale

He’s locked away in his castle in the woods,

with only his tormenting memories for

company, until governess Zelah Pentewan

crosses the threshold …

BENEATH THE MAJOR’S SCARS

December 2012

Jasper Coale, Viscount Markham

Used to having his own way where women

are concerned, Jasper would bet his fortune

on being able to seduce beautiful

Susannah Prentess—but she proves

stubbornly resistant to his charms!

BEHIND THE RAKE’S WICKED WAGER

January 2013

AUTHOR NOTE

Identical twins—fascinating, aren’t they? And they have been used very often in plots—by Shakespeare and Georgette Heyer, amongst others.

I have identical twin boys myself, and they came as a bit of a shock. It was only after the birth that I learned there were twins on my mother’s side of the family, and as she and I were both born under the star sign of Gemini—the twins—perhaps I should have been more prepared! However, I know from experience that twins are individuals, so when I decided to write about Jasper and Dominic Coale I wanted to give them very different stories. I began with Dominic, the younger brother. This is his story.

It was common practice amongst the English aristocracy for younger sons to join the army, and so it is with Dominic. He goes off to fight in the Peninsula War, but after suffering terrible injuries he finds his life takes a very different turn from that of his twin.

When Zelah (and the reader) first meets Dominic he has retired to Rooks Tower, an isolated house on Exmoor. He is irascible and a confirmed recluse, but Zelah’s young nephew Nicky has seen beyond his defensive shell and considers Dominic a firm friend. It is through Nicky that Zelah and Dominic meet and discover a mutual attraction, although they are both reluctant to acknowledge it. Zelah has been hurt before, and is determined upon an independent life, while Dominic believes his scarred face and body must repel every woman. They both have lessons to learn if they are to achieve happiness.

Some time ago I wrote a Christmas story—SNOWBOUND WITH THE NOTORIOUS RAKE—which is set on Exmoor, the beautiful wild moors in the south-west of England. Ever since I have wanted to use Exmoor again, so this is where Dominic buys his property, Rooks Tower, and it is here that Zelah falls in love with the proud man behind the horrific scars.

I really enjoyed writing Dominic and Zelah’s story, and I hope you have as much pleasure reading it.

About the Author

SARAH MALLORY was born in Bristol, and now lives in an old farmhouse on the edge of the Pennines with her husband and family. She left grammar school at sixteen to work in companies as varied as stockbrokers, marine engineers, insurance brokers, biscuit manufacturers and even a quarrying company. Her first book was published shortly after the birth of her daughter. She has published more than a dozen books under the pen-name of Melinda Hammond, winning the Reviewers’ Choice Award in 2005 from Singletitles.com for Dance for a Diamond and the Historical Novel Society’s Editors’ Choice in November 2006 for Gentlemen in Question.

Previous novels by the same author:

THE WICKED BARON MORE

THAN A GOVERNESS

(part of On Mothering Sunday)

WICKED CAPTAIN, WAYWARD WIFE

THE EARL’S RUNAWAY BRIDE

DISGRACE AND DESIRE

TO CATCH A HUSBAND …

SNOWBOUND WITH THE NOTORIOUS RAKE

(part of An Improper Regency Christmas)

THE DANGEROUS LORD DARRINGTON

Look for Sarah Mallory’s THE ILLEGITIMATE MONTAGUE part of Castonbury Park Regency mini-series Available now

Did you know that some of these novels are also available as eBooks? Visit www.millsandboon.co.uk

Beneath the

Major’s Scars

Sarah Mallory

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

For P and S, my own twin heroes.

Prologue

Cornwall—1808

The room was very quiet. The screams and cries, the frantic exertions of the past twelve hours were over. The bloodied cloths and the tiny, lifeless body had been removed and the girl lay between clean sheets, only the glow of firelight illuminating the room. Through the window a single star twinkled in the night sky. She did not seek it out, she had no energy for such conscious effort, but it was in her line of vision and it was easier to fix her eyes on that single point of light than to move her head.

Her body felt like a dead weight, exhausted by the struggle she had endured. Part of her wondered why she was still alive, when it would be so much better for everyone if she had been allowed to die with her baby.

She heard the soft click of the opening door and closed her eyes, not wishing to hear the midwife’s brisk advice or her aunt’s heart-wrenching sympathy.

‘Poor lamb.’ Aunt Wilson’s voice was hardly more than a sigh. ‘Will she survive, do you think?’

‘Ah, she’ll live, she’s a strong ‘un.’ From beneath her lashes the girl could see the midwife standing at the foot of the bed, wiping her hands on her bloody apron. ‘Although it might be better if she didn’t.’

‘Ah, don’t say that!’ Aunt Wilson’s voice cracked. ‘She is still God’s creature, even though she has sinned.’

The midwife sniffed.

‘Then the Lord had better look out for her, poor dearie, for her life is proper blighted and that’s for sure. No man will want her to wife now.’

‘She must find some way to support herself. I cannot keep her indefinitely, and my poor brother and his wife have little enough: the parish of Cardinham is one of the poorest in Cornwall.’

There was a pause, then the midwife said, ‘She ain’t cut out to be a bal maiden.’

‘To work in the mines? Never! She is too well bred for that.’

‘Not too well bred to open her legs for a man—’

Aunt Wilson gasped in outrage.

‘You have said quite enough, Mrs Nore. Your work is finished here, I will look after my niece from now on. Come downstairs and I will pay you for your trouble …’

The rustle of skirts, a soft click of the door and silence. She was alone again.

It was useless to wish she had died with her baby. She had not, and the future seemed very bleak, nothing but hard work and drudgery. That was her punishment for falling in love. She would face that, and she would survive, but she would never put her trust in any man again. She opened her eyes and looked at that tiny, twinkling orb.

‘You shall be my witness,’ she whispered, her lips painfully dry and her throat aching with the effort. ‘No man shall ever do this to me again.’

Her eyes began to close and she knew now that whenever she saw that star in the evening sky, she would remember the child she had lost.

Chapter One

Exmoor—1811

‘Nicky, Nicky! wait for me—oh!’

Zelah gave a little cry of frustration as her skirts caught on the thorny branches of an encroaching bush. She was obliged to give up her pursuit of her little nephew while she disentangled herself. How she wished now that she had put on her old dimity robe, but she had been expecting to amuse Nicky in the garden, not to be chasing him through the woods; only Nurse had come out to tell them that they must not make too much noise since the mistress was trying to get some sleep before Baby woke again and demanded to be fed.

As she carefully eased the primrose muslin off the ensnaring thorns, Zelah pondered on her sister’s determination to feed the new baby herself. She could quite understand it, of course: Reginald’s first wife had died in childbirth and a number of wet nurses had been employed for Nicky, but each one had proved more unreliable than the last so it was a wonder that the little boy had survived at all. The thought of her sister’s stepson made Zelah smile. He had not only survived, but grown into a very lively eight-year-old, who was even now leading her in a merry dance.

She had allowed him to take her ‘exploring’ in the wildly neglected woodland on the northern boundary of West Barton and now realised her mistake. Not only was Nicky familiar with the overgrown tracks that led through the woods, he was unhampered by skirts. Free at last, she pulled the folds of muslin close as she set off in search of her nephew. She had only gone a few steps when she heard him cry out, such distress and alarm in his voice that she set off at a run in the direction of his call, all concerns for snagging her gown forgotten.

The light through the trees indicated that there was a clearing ahead. She pushed her way through the remaining low tree branches and found herself standing on the lip of a steep slope. The land dropped away to form a natural bowl and the ground between the trees was dotted with early spring flowers, but it was not the beauty of the scene that made Zelah catch her breath, it was the sight of Nicky’s lifeless body stretched out at the very bottom of the dell, a red stain spreading over one leg of his nankeen pantaloons and a menacing figure bending over him.

Her first, wild thought was that it was some kind of animal attacking Nicky, but as her vision cleared she realised it was a man. A thick black beard covered his face and his shaggy hair reached to the shoulders of his dark coat. A longhandled axe lay on the ground beside him, its blade glinting wickedly in the spring sunlight.

Zelah did not hesitate. She scrambled down the bank.

‘Leave him alone!’ The man straightened. As he turned towards her she saw that beneath the shaggy mane of hair surrounding his face he had an ugly scar cutting through his left eyebrow and cheek. She picked up a stick. ‘Get away from him, you beast!’

‘Beast, is it?’ he growled.

‘Zelah—’

‘Don’t worry, Nicky, he won’t hurt you again.’ She kept her gaze fixed on the menacing figure. ‘How dare you attack an innocent boy, you monster!’

‘Beast, monster—’ His teeth flashed white through the beard as he stepped over the boy and came towards her, his halting, ungainly stride adding to the menace.

Zelah raised the stick. With a savage laugh he reached out and twisted the bough effortlessly out of her grasp, then caught her wrists as she launched herself at him. She struggled against his iron grip and her assailant hissed as she kicked his shin. ‘For heaven’s sake, I am not your villain. The boy tripped and fell.’ With a muttered oath he forced her hands down and behind her, so that she found herself pressed against his hard body. The rough wool of his jacket rubbed her cheek and her senses reeled as she breathed in the smell of him. It was not the sour odour of sweat and dirt she was expecting, but a mixture of wool and sandalwood and lemony spices combined with the earthy, masculine scent of the man himself. It was intoxicating.

He spoke again, his voice a deep rumble on her skin, for he was still holding her tight against his broad chest. ‘He tripped and fell. Do you understand me?’

He is speaking as if to an imbecile! was Zelah’s first thought, then the meaning of his words registered in her brain and she raised her head to meet his fierce eyes. She stopped struggling.

‘That’s better.’ He released his iron grip but kept his hard eyes fixed upon her. ‘Now, shall we take a look at the boy?’

Zelah stepped away, not sure if she trusted the man enough to turn her back on him, but a groan from Nicky decided it. Everything else was forgotten as she fell to her knees beside him.

‘Oh, love, what have you done?’

She put her hand on his forehead, avoiding the angry red mark on his temple. His skin was very hot and his eyes had a glazed, wild look in them.

The man dropped down beside her.

‘We’ve been clearing the land, so there are several ragged tree stumps. He must have caught his leg on one when he tumbled down the bank. It’s a nasty cut, but I don’t think the bone is broken.’

‘How would you know?’ demanded Zelah, carefully lifting away the torn material and gazing in horror at the bloody mess beneath.

‘My time in the army has given me considerable experience of injuries.’ He untied his neck-cloth. ‘I have sent my keeper to fetch help. I’ll bind up his leg, then we will carry him back to the house on a hurdle.’

‘Whose house?’ she asked suspiciously. ‘He should be taken to West Barton.’

‘Pray allow me to know what is best to be done!’

‘Please do not talk to me as if I were a child,’ she retorted. ‘I am quite capable of making a decision.’

He frowned, making the scar on his forehead even more ragged. He looked positively ferocious, but she refused to be intimidated and met his gaze squarely. He seemed to be struggling to contain his anger and after a moment he raised his hand to point towards a narrow path leading away through the trees. He said curtly, ‘Rooks Tower is half a mile in that direction; West Barton is at least five miles by carriage, maybe two if you go back on the footpath, the way you came.’

Zelah bit her lip. It would be impossible to carry Nicky through the dense undergrowth of the forest without causing him a great deal of pain. The boy stirred and she took his hand.

‘I d-don’t like it, it hurts!’

The plaintive cry tore at her heart.

‘Then it must be Rooks Tower,’ she said. ‘Let us hope your people get here soon.’

‘They will be here as soon as they can.’ He pulled the muslin cravat from his neck. ‘In the meantime I must stop the bleeding.’ His hard eyes flickered over her. ‘It will mean moving his leg.’

She nodded and squeezed Nicky’s hand.

‘You must be very brave, love, while we bind you up. Can you do that?’

‘I’ll try, Aunty.’

‘Your aunt, Nicky? She’s more of an Amazon, I think!’

‘Well, she is not really my aunt, sir,’ explained Nicky gravely. ‘She is my stepmama’s sister.’

Zelah stared, momentarily diverted.

‘You know each other?’

The man flicked a sardonic look towards her.

‘Of course, do you think I allow strange brats to run wild in my woods? Introduce us, Nicky.’

‘This is Major Coale.’ The boy’s voice wavered a little and his lip trembled as the major deftly wrapped the neckcloth around his leg. ‘And this, sir, is my aunt, Zelah.’

‘Celia?’

‘Zee-lah,’ she corrected him haughtily. ‘Miss Pentewan to you.’

‘Dear me, Nicholas, you should have warned me that your aunt is a veritable dragon.’

The scar cutting through his eyebrow gave him a permanent frown, but she heard the amusement in his voice. Nicky, clinging to Zelah’s hand and trying hard not to cry, managed a little chuckle.

‘There, all done.’ The major sat back, putting his hand on Nicky’s shoulder. ‘You were very brave, my boy.’

‘As brave as a soldier, sir?’

‘Braver. I’ve known men go to pieces over the veriest scratch.’

Zelah stared at the untidy, shaggy-haired figure in front of her. His tone was that of a man used to command, but beneath that faded jacket and all that hair, could he really be a soldier? She realised he was watching her and quickly returned her attention to her nephew.

‘What happened, love? How did you fall?’

‘I t-tripped at the top of the bank. There’s a lot of loose branches lying around.’

‘Aye. I’ve left them. Firewood for the villagers,’ explained the major. ‘We have been clearing the undergrowth.’

‘And about time too,’ she responded. ‘These woods have been seriously neglected.’

‘My apologies, madam, if they are not to your liking.’

Was he laughing at her? His face—the little she could see that was not covered by hair—was impassive.

‘My criticism is not aimed at you, Major. I believe Rooks Tower was only sold last winter.’

‘Yes, and I have not had time yet to make all the improvements I would wish.’

‘You are the owner?’

Zelah could not keep the astonishment out of her voice. Surely this ragged individual could not be rich enough to buy such a property?

‘I am. Appearances can be deceptive, Miss Pentewan.’

She flushed, knowing she deserved the coldness of his response.

‘I beg your pardon, that is, I—I am sure there is a vast amount to be done.’

‘There is, and one of my first tasks is to improve the road to the house and make it suitable for carriages again. I have men working on it now, but until that is done everything has to come in and out by packhorse.’

‘Major Coale’s books had to be brought here by pack-pony,’ put in Nicky. ‘Dozens of boxes of them. She likes books,’ he explained to the major, whose right eyebrow had risen in enquiry.

‘We have an extensive library at home,’ added Zelah.

‘And where is that?’

‘Cornwall.’

‘I guessed that much from your name. Where in Cornwall?’

A smile tugged at her mouth, but she responded seriously.

‘My father is rector at Cardinham, near Bod-min.’

Zelah looked up as a number of men arrived carrying a willow hurdle.

She scrambled to her feet and stepped back. The major handed his axe to one of the men before directing the delicate operation of lifting Nicky on to the hurdle. When they were ready to move off she fell into step beside the major, aware of his ungainly, limping stride as they followed the hurdle and its precious burden through the woods.

‘I can see you have some experience of command, Major.’

‘I was several years in the army.’

Zelah glanced at him. He had been careful to keep to the left of the path so only the right side of his face was visible to her. Whether he was protecting her sensibilities or his own she did not know.

‘And now you plan to settle at Rooks Tower?’

‘Yes.’

‘It is a little isolated,’ she remarked. ‘Even more so than West Barton.’

‘That is why I bought it. I have no wish for company.’

Zelah lapsed into silence. His curt tone made the meaning of his words quite clear. He might as well have said I have no wish for conversation. Very well, she had no desire to intrude upon his privacy. She would not speak again unless it was absolutely necessary.

Finally they emerged from the trees and Zelah had her first glimpse of Rooks Tower. There was a great sweep of lawn at the front of the house, enclosed by a weed-strewn drive. At the far side of the lawn stood a small orangery, but years of neglect had dulled the white lime-wash and many of its windows were broken. Zelah turned away from this forlorn object to study the main house. At its centre was an ancient stone building with an imposing arched entrance, but it had obviously been extended over the centuries and two brick-and-stone wings had been added. Everything was arranged over two floors save for a square stone tower on the south-eastern corner that soared above the main buildings.

‘Monstrosity, isn’t it?’ drawled the major. ‘The house was remodelled in Tudor times, when the owner added the tower that gives the house its name, so that his guests could watch the hunt. It has a viewing platform on the roof, but we never use it now.’

She looked again at the house. There had been many alterations over the years, but it retained its leaded lights and stone mullions. Rooks Tower fell short of the current fashion for order and symmetry, but its very awkwardness held a certain charm.

‘The views from the tower must be magnificent.’ She cast an anxious look at him. ‘You will not change it?’

He gave a savage laugh.

‘Of course not. It is as deformed as I!’

She heard the bitterness in his tone, but could not think of a suitable response. The path had widened and she moved forwards to walk beside Nicky, reaching out to take his hand. It was hot and clammy. Zelah hid her dismay beneath a reassuring smile.

‘Nearly there, love. We shall soon make you more comfortable.’

The major strode on ahead, his lameness barely noticeable as he led the way into the great hall where an iron-haired woman in a black-stuff gown was waiting for them. She bobbed a curtsy.

‘I have prepared the yellow room for the young master, sir, and popped a warm brick between the sheets.’

‘Thank you, Mrs Graddon.’ He did not break his stride as he answered her, crossing the hall and taking the stairs two at a time, only pausing to turn on the half-landing. ‘This way, but be careful not to tilt the litter!’

Dominic waited only to see the boy laid on the bed that had been prepared for him before striding off to his own apartments to change out of his working clothes. It was a damnable nuisance, having strangers in the house, but the boy was hurt, what else could he do? He did not object to having Nicky in the house. He was fond of the boy and would do all he could to help him, but it would mean having doctors and servants running to and fro. He could leave everything to Graddon and his wife, of course, and the aunt would look after the boy until Buckland could send someone.

The thought of Miss Zelah Pentewan made him pause. A reluctant smile touched his lips and dragged at the scarred tissue of his cheek. She was not conventionally pretty, too small and thin, with mousy brown hair and brown eyes. She reminded him of a sparrow, nothing like the voluptuous beauties he had known. When he thought of her standing up to him, prepared to fight him to protect her nephew … by God she had spirit, for she barely came up to his shoulder!

He washed and dried his face, his fingers aware of the rough, pitted skin on his left cheek through the soft linen cloth. He remembered how she had glared at him, neither flinching nor averting her eyes once she had seen his scarred face. He gave her credit for that, but he would not subject her to the gruesome sight again. There was plenty for him to do that would keep him well away from the house for a few days.

‘Well, I have cleaned and bandaged the leg. Now we must wait. I have given him a sleeping draught which should see him through to the morning and after that it will be up to you to keep him still while the leg heals. He will be as good as new in a few weeks.’

‘Thank you, Doctor.’

Zelah stared down at the motionless little figure in the middle of the bed. Nicky had fainted away when the doctor began to work on his leg and now he looked so fragile and uncharacteristically still that tears started to her eyes.

‘Now, now, Miss Pentewan, no need for this. The boy has a strong constitution—by heaven, no one knows that better than I, for I have been calling at West Barton since he was a sickly little scrap of a baby that no one expected to survive. I’m hoping that bruise on his head is nothing serious. I haven’t bled him, but if he begins to show a fever then I will do so tomorrow. For now keep him calm and rested and I will call again in the morning.’

The doctor’s gruff kindness made her swallow hard.

‘Thank you, Dr Pannell. And if he wakes in pain …?’

‘A little laudanum and water will do him no harm.’

There was a knock at the door and the housekeeper peeped in.

‘Here’s the little lad’s papa come to see him, Doctor.’ She flattened herself against the door as Reginald Buckland swept in, hat, gloves and riding whip clutched in one hand and an anxious look upon his jovial features.

‘I came as soon as I heard. How is he?’

Zelah allowed the doctor to repeat his prognosis.

‘Can he be moved?’ asked Reginald, staring at his son. ‘Can I take him home?’

‘I would not advise it. The wound is quite deep and any jolting at this stage could start it bleeding again.’

‘But he cannot stay here, in the house of a man I hardly know!’

Doctor Pannell’s bushy eyebrows drew together.

‘I understood the major was some sort of relative of yours, Mr Buckland.’

Reginald shrugged.

‘Very distant. Oh, I admit it was through my letters to a cousin that he heard about Rooks Tower being vacant, but I had never met him until he moved here, and since then we have exchanged barely a dozen words. He has never once come to West Barton.’

A grim little smile hovered on the doctor’s lips.

‘No, Major Coale has not gone out of his way to make himself known to his neighbours.’

‘I think Nicky must stay here, Reginald.’ Zelah touched his arm. ‘Major Coale has put his house and servants at our disposal.’

‘Aye, he must, at least until the wound begins to heal,’ averred Dr Pannell, picking up his hat. ‘Now, I shall be away and will return tomorrow to see how my patient does.’

Reginald remained by the bed, staring down at his son and heir. He rubbed his chin. ‘If only I knew what to do. If only his mama could be with him!’

‘Impossible, when she is confined with little Reginald.’

‘Or Nurse.’

‘Yes, she would be ideal, but my sister and the new baby need her skill and attentions,’ said Zelah. ‘I have considered all these possibilities, Reginald, and I think there is only one solution. You must leave Nicky to my care.’

‘But that’s just it,’ exclaimed Reginald. ‘I cannot leave you here.’

‘And I cannot leave Nicky.’

‘Then I had best stay, too.’

Zelah laughed.

‘Now why should you do that? You know nothing about nursing. And besides, what will poor Maria do if both you and I are away from home? I know how my sister suffers with her nerves when she is alone for too long.’

‘Aye, she does.’ Reginald took a turn about the room, torn by indecision.

Nicky stirred and muttered something in his sleep.

‘Go home, Reginald. These fidgets will disturb Nicky.’

‘But this is a bachelor household.’

‘That is unfortunate, of course, but it cannot be helped.’ She dipped a cloth in the bowl of lavender water and gently wiped the boy’s brow. ‘If it is any comfort, Reginald, Major Coale has informed me—via his housekeeper—that he will not come into this wing of the house while we are here. Indeed, once he had seen Nicky safely into bed he disappeared, giving his housekeeper orders to supply us with everything necessary. I shall sleep in the anteroom here, so that I may be on hand should Nicky wake in the night, and I will take my meals here. So you see there can be no danger of impropriety.’

Reginald did not look completely reassured.

‘Would you like me to send over our maid?’

‘Unnecessary, and it would give offence to Mrs Graddon.’ Zelah smiled at him. ‘We shall go on very comfortably, believe me, if you will arrange for some clothes to be sent over for us. And perhaps you will come again tomorrow and bring some games for Nicky. Then we shall do very well.’

‘But it will not do! You are a gently bred young lady—’

‘I am soon to be a governess and must learn to deal with situations such as this.’ She squeezed his arm. ‘Trust me, Reginald. Nicky must stay here and I shall remain to look after him until he can be moved to West Barton. Now go and reassure Maria that all is well here.’

He took his leave at last and Zelah found herself alone in the sickroom for the first time. Nicky was still sleeping soundly, which she knew was a good thing, but it left her with little to do, except rearrange the room to her satisfaction.

Zelah took dinner in the room, but the soup the housekeeper brought up for Nicky remained untouched, for he showed no signs of waking.

‘Poor little lamb, sleep’s the best thing for him,’ said Mrs Graddon when she came to remove the dishes. ‘Tomorrow I shall make some lemon jelly, to tempt his appetite. I know he’s very fond of that.’

‘Oh?’ Zelah looked up. ‘Is my nephew in the habit of calling here?’

‘Aye, bless his heart. If he finds an injured animal or bird in the woods he often brings it here for the master to mend, and afore he goes he always comes down to the kitchens to find me.’

Zelah put her hands to her cheeks, mortified.

‘Oh dear, he really should not be bothering Major Coale with such things, or you.’

‘Lord love ‘ee, mistress, the boy ain’t doin’ no ‘arm,’ exclaimed Mrs Graddon. ‘In fact, I think ‘e does the master good.’ She paused, slanting a sidelong glance at Zelah. ‘You’ve probably noticed that the major shuns company, but that’s because o’ this.’ She rubbed her finger over her left temple. ‘Right across his chest, it goes, though thankfully it never touched his vital organs. Took a cut to his thigh, too, but the sawbones stitched him up before he ever came home, so his leg’s as good as new.’

‘But when he walks …’

The housekeeper tutted, smoothing down her apron.

‘He’s had the very finest doctors look at ‘im and they can find nothing wrong with his leg. They say ‘tis all in his head. For the master don’t always limp, as I’ve noticed, often and often.’ She sighed. ‘Before he went off to war and got that nasty scar he was a great one for society—him and his brother both. Twins they are and such handsome young men, they captured so many hearts I can’t tell you!’

‘You’ve known the family for a long time?’

‘Aye, miss, I started as a housemaid at Markham, that’s the family home, where the master’s brother, the viscount, now lives. Then when the master decided to set up his own house here, Graddon and I was only too pleased to come with him. But he don’t go into company, nor does he invite anyone here, and I can understand that. I’ve seen ‘em—when people meets the master, they look everywhere but at his face and that do hurt him, you see. But Master Nick, well, he treats the major no different from the rest.’

Zelah was silent. In her mind she was running over her meeting with Major Coale. Had she avoided looking at his terrible scarred face? She thought not, but when she had first seen him she believed he was attacking Nicky and she had been in no mood for polite evasions.

The housekeeper went off and Zelah settled down to keep watch upon her patient.

* * *

As the hours passed the house grew silent. She had a sudden yearning for company and was tempted to go down to the kitchen in the hope of meeting the housekeeper, or even a kitchen maid. She would do no such thing, of course, and was just wondering how she could occupy herself when there was a knock at the door. It was Mrs Graddon.

‘The major asked me to bring you these, since you likes reading.’ She held out a basket full of books. ‘He says to apologise, but they’s all he has at the moment, most of his books being still in the crates they arrived in, but he hopes you’ll find something here to suit.’

‘Thank you.’ Zelah took the basket and retreated to her chair by the fire, picking up the books one by one from the basket. Richardson, Smollett, Defoe, even Mrs Radcliffe. She smiled. If she could not amuse herself with these, then she did not deserve to be pleased. She was comforted by the major’s thoughtfulness. Feeling much less lonely, she settled down, surrounded by books.

It was after midnight when Nicky began to grow restless. Zelah was stretched out on the bed prepared for her when she heard him mutter. Immediately she was at his side, feeling his brow, trying to squeeze a little water through his parched lips. He batted aside her hand and turned his head away, muttering angrily. Zelah checked the bandages. They were still in place, but if he continued to toss and turn he might well open the wound and set it bleeding again.

She wished she had not refused Mrs Graddon’s offer to have a truckle bed made up in the room for a maid, but rather than wring her hands in an agony of regret she picked up her bedroom candle and set off to find some help.

Zelah had not ventured from the yellow bedroom since she had followed Nicky there earlier in the day. She retraced her steps back to the great hall, too anxious about her nephew to feel menaced by the flickering shadows that danced around her. There was a thin strip of light showing beneath one of the doors off the hall and she did not hesitate. She crossed to the door and knocked softly before entering.

She was in Major Coale’s study, and the man himself was sitting before the dying fire, reading by the light of a branched candelabra on the table beside him.

‘I beg your pardon, I need to find Mrs Graddon. It’s Nicky …’

He had put down his book and was out of the chair even as she spoke. He was not wearing his coat and the billowing shirt-sleeves made him look even bigger than she remembered.

‘What is wrong with him?’

‘He is feverish and I c-cannot hold him …’

‘Let me see.’ He added, observing her hesitation, ‘I have some knowledge of these matters.’

Zelah nodded, impatient to return to Nicky. They hurried upstairs, the major’s dragging leg causing his shoe to scuff at each step. It was no louder than a whisper, but it echoed through the darkness. Nicky’s fretful crying could be heard even as they entered the anteroom. Zelah flew to his side.

‘Hush now, Nicky. Keep still, love, or you will hurt your leg again.’

‘It hurts now! I want Mama!’

The major put a gentle hand on his forehead.

‘She is looking after your little brother, sir. You have your aunt and me to take care of you.’ He inspected the bottles ranged on the side table and quickly mixed a few drops of laudanum into a glass of water.

The calm, male voice had its effect. Nicky blinked and fixed his eyes on Zelah, who smiled at him.

‘You are a guest in the major’s house, Nicky.’

‘Oh.’ The little fingers curled around her hand. ‘And are you staying here too, Aunt Zelah?’

‘She is,’ said the major, ‘for as long as you need her. Now, sir, let me help you sit up a little and you must take your medicine.’

‘No, no, it hurts when I move.’

‘We will lift you very carefully,’ Zelah assured him.

‘I don’t want to …’

‘Come, sir, it is only a little drink and it will take the pain away.’

The major slipped an arm about the boy’s shoulders and held the glass to his lips. Nicky took a little sip and shuddered.

‘It is best taken in one go,’ the major advised him.

The little boy’s mouth twisted in distaste.

‘Did you take this when you were wounded?’

‘Gallons of it,’ said the major cheerfully. ‘Now, one, two, three.’ He ruthlessly tipped the mixture down the boy’s throat. Nicky swallowed, shuddered and his lip trembled. ‘There, it is done and you were very brave. Miss Pentewan will turn your pillows and you will soon feel much more comfortable.’

‘Will you stay, ‘til I go to sleep again?’

‘You have your aunt here.’

‘Please.’

Zelah responded with a nod to the major’s quick glance of enquiry.

‘Very well.’ He sat down at the side of the bed and took the little hand that reached out for him.

‘Would you like me to tell you a story?’ asked Zelah, but Nicky ignored her. He fixed his eyes upon the major.

‘Will you tell me how you got your scar?’

Zelah stopped breathing. She glanced at the major. He did not look to be offended.

‘I have told you that a dozen times. You cannot want to hear it again.’

‘Yes, I do, if you please, sir. All of it.’

‘Very well.’

He pulled his chair closer to the bed and Zelah drew back into the shadows.

‘New Year’s Day ‘09 and we were struggling through the mountains back towards Corunna, with the French hot on our heels. The weather was appalling. During the day the roads were rivers of mud and by night they were frozen solid. When we reached Cacabelos—’

‘You missed something,’ Nicky interrupted him. ‘The man with the pigtail.’

‘Ah, yes.’ Major Coale’s eyes softened in amusement. In the shadows Zelah smiled. She had read Nicky enough stories to know he expected the same tale, word for word, each time. The major continued. ‘One Highlander woke to find he couldn’t get up because his powdered pigtail was frozen to the ground. A couple of days later we reached the village of Cacabelos and the little stone bridge over the River Cua. Unfortunately discipline had become a problem during that long retreat to Corunna and General Edward Paget was obliged to make an example of those guilty of robbery. He was about to execute two of the men when he heard that the French were upon us. The general was extremely vexed at this, and after cursing roundly he turned to his men. “If I spare the lives of these men,” he said, “do I have your word of honour as soldiers that you will reform?” The men shouted “Yes!” and the convicted men were cut down.’

‘Huzza!’ Nicky gave a sleepy cheer.

Major Coale continued, his voice soft and low.

‘And just in time, for the enemy were already in sight. They were upon us in an instant, the French 15th Chasseurs and the 3rd Hussars, all thundering down to the bridge. All was confusion—our men could not withdraw because the way was blocked with fighting men and horses. Fortunately the chasseurs were in disarray and drew back to regroup, giving us time to get back across the bridge. We fixed bayonets and waited below the six guns of the horse artillery, which opened fire as the French charged again. The 52nd and the 95th delivered a furious crossfire on their flanks, killing two generals and I don’t know how many men, but still they came on and fell upon us.’

He paused, his brow darkening. Nicky stirred and the major drew a breath before going on.

‘I found myself caught between two chasseurs. I wounded one of them, but the other closed in. His sabre slashed down across my face and chest. I managed to unseat him and he crashed to the ground. He made another wild slash and caught my leg, but I had the satisfaction of knowing he was taken prisoner and his comrades were in full retreat before I lost consciousness.’

‘Don’t stop, sir. What happened then?’ Nicky’s eyes were beginning to close.

‘I was patched up and put on to a baggage wagon. Luckily I had no serious internal injuries, for I fear it would have been fatal to be so shaken and jarred as we continued to Villafranca. I remember very little after that until we reached England. Someone had sent word to Markham, and my brother came to collect me from Falmouth and take me home. There I received the best treatment available, but alas, even money cannot buy me a new face.’

He lapsed into silence. Nicky was at last in a deep sleep, his little hand still clasped in the major’s long lean fingers. Silence enveloped them. At length the major became aware of Zelah’s presence and turned to look at her. She realised then her cheeks were wet with tears.

‘I—I beg your pardon.’ Quickly she turned away, pulling out her handkerchief. ‘You have been most obliging, Major Coale, more than we had any right to expect.’ She wiped her eyes, trying to speak normally. ‘Nicky is sleeping now. We do not need to trouble you any longer.’

‘And what will you do?’

‘I shall sit with him …’

He shook his head.

‘You cannot sit up all night. I will watch over him for a few hours while you get some sleep.’

Zelah wavered. She was bone-weary, but she was loath to put herself even deeper in this man’s debt. He gave an exasperated sigh.

‘Go and lie down,’ he ordered her. ‘You will not be fit to look after the boy in the morning if you do not get some sleep.’

He was right. Zelah retired to the little anteroom. She did not undress, merely removed her shoes and stretched out on the bed, pulling a single blanket over her. Her last waking thought was that it would be impossible to sleep with Major Coale sitting in the next room.

Zelah was awoken by a cock crowing. It was light, but the sun had not yet risen. She stared at the unfamiliar surroundings, then, as memory returned, she slipped off the bed and crept into the next room. Nicky was still sleeping soundly and the major was slumped forwards over the bed, his shaggy dark head on his arms.

The fire had died and the morning air was very chill. Noiselessly Zelah crossed the room and knelt down by the hearth.

‘What are you doing?’

The major’s deep voice made her jump.

‘I am going to rescue the fire.’

‘Oh, no, you are not. I will send up a servant to see to that.’

He towered over her, hand outstretched. She allowed him to help her up, trying to ignore the tingle that shot through her at his touch. It frightened her. His presence filled the room, it was disturbing, suffocating, and she stepped away, searching for something to break the uneasy silence.

‘I—um—the story you told Nicky, about your wound. It was very … violent for a little boy. He seemed quite familiar with it.’

‘Yes. He asked me about my face the very first time he saw me and has wanted me to recount the story regularly ever since.’ He was watching the sleeping boy, the smile tugging at his lips just visible through the black beard. ‘I was working in the woods and he came up, offered to help me finish off the game pie Mrs Graddon had packed into my bag to sustain me through the day.’

‘You must have thought him very impertinent.’

‘Not at all. His honesty was very refreshing. Most people look away, embarrassed by my disfigurement.’

‘Oh, I beg your pardon. I hope you did not think that I—’

The smile turned into a grin.

‘You, madam, seemed intent upon inflicting even more damage upon me.’

The amusement in his eyes drew a reluctant smile from Zelah.

‘You did—do—look rather savage. Although I know now that you are very kind,’ she added in a rush. She felt herself blushing. ‘You have been sitting here all night and must be desperate for sleep. I can manage now, thank you, Major. You had best go …’

‘I should, of course. I will send someone up to see to the fire and order Mrs Graddon to bring your breakfast to you.’

‘Thank you.’ He gave her a clipped little bow and turned to leave.

‘Major! The chasseur—the one who injured you—was he really taken prisoner?’

He stopped and looked back.

‘Yes, he was.’ His eyes narrowed. ‘I may look like a monster, Miss Pentewan, but I assure you I am not.’

Chapter Two

Nicky was drowsy and fretful when he eventually woke up, but Dr Pannell was able to reassure Zelah that he was recovering well.

‘A little fever is to be expected, but he seems to be in fine form now. I think keeping him still is going to be your biggest problem.’

Zelah had thought so too and she was relieved when Reginald arrived with a selection of toys and games for his son.

‘Goodness!’ She laughed when she saw the large basket that Reginald placed on the bed. ‘Major Coale will think we plan to stay for a month.’

Reginald grinned.

‘I let Nurse choose what to send. I fear she was over-generous to make up for not being able to come herself.’

‘And what did our host say, when you came in with such a large basket?’

‘I have not seen him. His man informed me that he is busy with his keeper and likely to be out all day.’ He glanced at Nicky, happily sorting through the basket, and led Zelah into the anteroom. ‘I had the feeling he was ordered to say that and to make sure I knew that he had given instructions for a maid to sit up with the boy during the night. Setting my mind at rest that he would not be imposing himself upon you while you are here.’

‘Major Coale is very obliging.’

‘Dashed ragged fellow though, with all that hair, but I suppose that’s to cover the scar on his face.’ He paused. ‘Maria asked me to drop a word in your ear, but for my part I don’t think there’s anything to worry about.’

‘What did she wish you to say to me?’

He chewed his lip for a moment.

‘She was concerned. Coale was well known as something of a, er, a rake before the war. His name was forever in the society pages. Well, stands to reason, doesn’t it, younger son of a viscount, and old Lord Markham had some scandals to his name, I can tell you! Coale’s brother’s inherited the title now, of course, and from what I have read he’s just as wild as the rest of ‘em.’ He added quickly, ‘Only hearsay, of course. I’ve never had much to do with that side of the family—far too high and mighty for one thing. The Bucklands are a very distant branch. But that’s neither here nor there. We were worried the major might try to ingratiate himself with you—after all, we are mighty obliged to him—and Maria thought you might have … stirrings.’

‘Stirrings, Reginald?’

He flushed.

‘Aye. Maria says that sometimes a woman’s sympathy for an injured man can stir her—that she can find him far too … attractive.’

Zelah laughed.

‘Then you may set Maria’s mind at rest. The only stirring I have when I think of Major Coale is to comb his hair!’

Reginald stayed for an hour or more and after that Hannah, the chambermaid appointed to help Zelah look after Nicky, came up to introduce herself. By the time dinner was brought up it was clear that she was more than capable of nursing Nicky and keeping him amused, and Zelah realised a trifle ruefully that it was not Nicky’s boredom but her own that might be a problem.

Zelah and Hannah had taken it in turns to sit up with Nicky through the night, but there was no recurrence of the fever and when Dr Pannell called the following morning he declared himself satisfied that the boy would be able to go home at the end of the week.

‘I will call again on Friday, Miss Pentewan, and providing there has been no more bleeding we will make arrangements to return you both to West Barton. You will be the first to use the major’s new carriageway.’

‘Oh, is it finished?’ asked Zelah. ‘I have been watching them repair the drive, but I cannot see what is going on beyond the gates.’

‘I spoke to the workmen on the way here and they told me the road will be passable by tomorrow. The road-building has been a godsend for Lesserton, providing work for so many of the men. The problems with grazing rights is making it difficult for some of them to feed their families.’

‘Is this the dispute with the new owner of Lydcombe Park? My brother-in-law mentioned something about this before I came away.’

‘Aye, Sir Oswald Evanshaw moved in on Lady Day and he is claiming land that the villagers believe belongs to them.’ The doctor shook his head. ‘Of course, he has a point: the house has changed hands several times in recent years, but no one has actually lived there, so the villagers have been in the habit of treating everything round about as their own. The boundaries between Lydcombe land and that belonging to the villagers have become confused. He’s stopped them going into Prickett Wood, too, so they cannot collect the firewood as they were used to do and Sir Oswald’s bailiff is prepared to use violence against anyone who tries to enter the wood. He’s driven out all the deer, so that they are now competing with the villagers’ stock for fodder.’ He was silent for a moment, frowning over the predicament, then he shook off his melancholy thoughts and gave her a smile. ‘Thankfully Major Coale is of a completely different stamp. He is happy for the local people to gather firewood from his forest. It is good fortune that Nicky chose to injure himself on the major’s land rather that at Lydcombe.’

Zelah had agreed, but as the day wore on she began to wonder if she would have the opportunity to thank her host for his hospitality. With Hannah to share the nursing Zelah was growing heartily bored with being confined to the sickroom.

When the maid came up the following morning she asked her casually if the major was in the house.

‘Oh, no, miss. He left early. Mr Graddon said not to expect him back much before dinner.’

She bobbed a curtsy and settled down to a game of spillikins with Nicky. Left to amuse herself, Zelah carried her work basket to the cushioned window seat and took out her embroidery. It was a beautiful spring day and she could hear the faint call of the cuckoo in the woods.

The sun climbed higher. Zelah put away her sewing and read to Nicky while Hannah quietly tidied the room around them. The book was one of Nicky’s favourites, Robinson Crusoe, but as the afternoon wore on his eyelids began to droop, and soon he was sleeping peacefully.

‘Best thing for’n. Little mite.’ Hannah looked down fondly at the sleeping boy. ‘Why don’t you go and get yourself some rest, too, miss? I’ll sit here and watch’n for ‘ee.’

Zelah sighed, her eyes on the open window.

‘What I would really like to do is to go outside.’

‘Then why don’t ‘ee? No one’ll bother you. You could walk in the gardens. I can always call you from the window, if the boy wakes up.’

Zelah hesitated, but only for a moment. The spring day was just too beautiful to miss. With a final word to Hannah to be sure to call her if she was needed, she slipped down the stairs and out of the house.

The lawns had been scythed, but weeds now inhabited the flowerbeds and the shrubs were straggling and overgrown. After planning how she would restock the borders and perhaps add a statue or two, she moved on and discovered the kitchen garden, where some attempt was being made to improve it.

The hedge separating the grounds from the track that led to the stables had been hacked down to waist height, beds had been dug and cold frames repaired. Heartened by these signs of industry, Zelah was about to retrace her steps when she heard the clip-clop of an approaching horse. Major Coale was riding towards the stables on a huge grey horse. She picked up her skirts and flew across to the hedge, calling out to him.

He stopped, looking around in surprise.

‘Should you not be with the boy?’

She stared up at him.

‘You have shaved off your beard.’

‘Very observant. But you have not answered my question.’

‘Hannah is sitting with him. It was such a beautiful day I had to come out of doors.’

She answered calmly, refusing to be offended by his curt tone and was rewarded when he asked in a much milder way how the boy went on.

‘He is doing very well, thank you. Dr Pannell is coming in the morning to examine Nicky. All being well, I hope to take him back to West Barton tomorrow.’ He inclined his head and made to move on. She put up her hand. ‘Please, don’t go yet! I wanted to thank you for all you have done for us.’

‘That is not necessary.’

‘I think it is.’ She smiled. ‘I believe if I had not caught you now I should not have seen you again before we left.’

He looked down at her, unsmiling. His grey eyes were as hard as granite.

‘My staff have orders to look after you. You have no need to see me.’

‘But I want to.’ She glanced away, suddenly feeling a little shy. ‘You have been very kind to us. I wanted to thank you.’

She could feel his eyes boring into her and kept her own fixed on the toe of his muddy boot.

‘Very well,’ he said at last. ‘You have thanked me. That is an end to it.’

He touched his heels to the horse’s flanks and moved on.

‘I wish I had said nothing,’ she muttered, embarrassment making her irritable. ‘Did I expect him to thaw a little, merely because I expressed my gratitude? The man is nothing but a boor.’

Even as she spoke the words she came to a halt as another, more uncomfortable thought occurred. Perhaps Major Coale was lonely.

What was it Mrs Graddon had said? He was a great one for society. That did not sit well with his assertion that he had no wish for company. His curt manner, the long hair and the shaggy beard that had covered his face until today—perhaps it was all designed to keep the world at bay.

‘Well, if that is so, it is no concern of mine,’ she addressed the rosemary bush beside her. ‘We all have our crosses to bear and some of us do not have the means to shut ourselves away and wallow in our misery!’

When Dr Pannell called the next day he gave Nicky a thorough examination, at the end of which Zelah asked him anxiously if he might go home now.

‘I think not, my dear.’

‘But his mama is so anxious for him,’ said Zelah, disappointed. ‘And you said he might be moved today …’

‘I know, but that was when I thought the major’s new road would be finished. Now they tell me it will not be open properly until tomorrow. Be patient, my dear. Major Coale has told me his people will be working into the night to make the road passable for you.’

With that she had to be satisfied. Nick appeared quite untroubled by the news that he was to remain at Rooks Tower. His complaisance was much greater than Zelah’s. She hated to admit it, but she was finding the constant attendance on an eight-year-old boy and the company of an amiable but childish chambermaid a little dull.

After sharing a light luncheon with Nicky, Zelah left the boy reading with Hannah and went off in search of Mrs Graddon, to offer her help, only to find that the good lady had gone into Lesserton for supplies. Unwilling to return to the sickroom just yet, Zelah picked up her shawl and went out to explore more of the grounds.

Having seen enough of the formal gardens, she walked around to the front of the house and headed for the orangery. A chill wind was blowing down from the moors and she wrapped her shawl about her as she crossed the lawn. The orangery was built in the classical style. Huge sash windows were separated by graceful pillars that supported an elegant pediment. Between the two central columns were glazed double doors. The stone was in good order, if in need of a little repair, but the woodwork looked sadly worn and several panes of glass were broken.

Zelah was surprised to find the doors unlocked. They opened easily and she stepped inside, glad to be out of the wind. The interior was bare, save for a few dried leaves on the floor, but there were niches in the walls which were clearly designed to hold statues. A shadow fell across her and she swung around.

‘Oh.’

Major Coale was standing in the doorway. She guessed he had just returned from riding, for his boots were spattered with mud and there was a liberal coating of dust on his brown coat. His broad-brimmed hat was jammed on his head and its shadow made it impossible to read his expression. She waved her hand ineffectually.

‘I—um—I hope you do not mind …’

‘Why should I?’ He stepped inside, suddenly making the space seem much smaller. ‘I saw the open doors and came across to see who was here. What do you think of it?’

‘It is in need of a little repair,’ she began carefully.

‘I was thinking of tearing it down—’

‘No!’ She put her hand to her mouth. ‘I beg your pardon,’ she said stiffly. ‘It is of course up to you what you do here.’

‘It is indeed, but I am curious, Miss Pentewan. What would you do with it?’

‘New windows and doors,’ she said immediately. ‘Then I would furnish it with chairs for the summer and in the winter I would use it as it was intended, to shelter orange trees.’

‘But I have no orange trees.’

‘You might buy some. I understand oranges are extremely good for one.’

He grunted.

‘You are never at a loss for an answer, are you, ma’am?’

Yes, she thought, I am at a loss now.

She gave a little shrug and looked away.

‘I should get back.’

‘I will accompany you.’

She hurried out into the sunlight and set off for the house. Major Coale fell into step beside her.

‘So you will be leaving us tomorrow. I met Dr Pannell on the road,’ he explained, answering her unspoken question. ‘You will be glad to return to West Barton.’

‘Yes.’ He drew in a harsh breath, as if she had touched a raw wound and she hurried to explain. ‘It is not—you have been all kindness, and your staff have done everything required …’

‘But?’

She drew her shawl a little tighter.

‘I shall be glad to have a little adult company once more.’

There. She had said it. But as soon as the words were uttered she regretted them. ‘Please do not think I am complaining—I am devoted to Nicky and could not have left him here alone.’

‘But you have missed intelligent conversation?’

‘Yes,’ she responded, grateful that he understood. ‘When I lived at home, in Cardinham, Papa and I would talk for hours.’

‘Of what?’

‘Oh, anything! Politics, music, books. At West Barton it is the same, although my sister is a little preoccupied at the moment with her baby. But when Reginald is at home we enjoy some lively debates.’ She flushed a little. ‘Forgive me, I am of course extremely grateful to you for all you have done—’

‘I know, you told me as much yesterday. Yet it appears I am failing as a host.’ They had reached the front door and he stopped. ‘Perhaps you would join me for dinner this evening.’ The request was so unexpected that she could only stare at him. ‘No, of course that is not possible. Forget I—’

‘Of course it is possible.’ She spoke quickly, while an inner voice screamed its warnings at her. To dine alone with a man, was she mad? But in that instant when he had issued his invitation she had seen something in his eyes, a haunting desolation that burned her soul. It was gone in a moment, replaced by his habitual cold, shuttered look. But that brief connection had wrenched at the core of loss and loneliness buried deep within her, and Zelah found the combination was just too strong to withstand. ‘I would be delighted to join you.’

His brows rose.

‘There will be no chaperone.’

‘Nicky will be in the house and your housekeeper.’

His hard eyes searched her face for a moment.

‘Very well, Miss Pentewan. Until dinner!’

With that he touched his hat, turned on his heel and marched off towards the stables.

* * *

Zelah looked at the scant assortment of clothes laid out on the bed. Whoever had packed her bag had clearly assumed she would spend all her time in the sickroom. Neither her serviceable grey gown nor the dimity day dress was suitable for dining with the major. However, there was a green sash and matching stole that she could wear with her yellow muslin. Mrs Graddon had washed it for her and there were only a few drawn threads from her escapade in the woods. Once she had tied the sash around her waist and draped the stole over her arms she thought it would serve her well enough as an evening dress.

In the few hours since the major had invited her to dine, Zelah had pondered upon his reasons for doing so, and had come to the conclusion that it was twofold: he was being kind to her, but also he was lonely. If she thought for a moment that he was attracted to her she would have declined his invitation, but Zelah had no illusions about herself. Her mirror showed her a very nondescript figure, too thin for beauty and with soft brown hair that was neither fashionably dark nor attractively blond. And at two-and-twenty she was practically an old maid.

Sometimes she thought back to the happy girl she had been at eighteen, with a ready laugh and a sparkle in her eyes. Her figure had been better then, too, but at eighteen she had been in love and could see only happiness ahead. A year later everything had changed. She had lost her love, her happy future and her zest for life. Looking in her mirror now, she saw nothing to attract any man. And that could only be to her benefit, she reminded herself, if she was going to make her own way in the world.

Hannah had found her a length of yellow ribbon for her hair and five minutes before the appointed hour she presented herself to her nephew.

‘Well, will I do?’

Nicky wrinkled his nose.

‘I wish I could come with you, Aunty.’

‘So, too, do I, love,’ said Zelah earnestly. She had been growing increasingly anxious about meeting the major as the dinner hour approached.

‘Ah, well, after I’ve given Master Nicky his supper we are going to finish our puzzle,’ said Hannah, beaming happily. ‘Now you go on and enjoy your dinner, miss, and don’t ‘ee worry about us, we shall have a fine time!’

Zelah made her way down to the great hall, where the evening sun created a golden glow. She had no idea where the drawing room might be and was just wondering what to do when Graddon appeared.

‘This way, madam, if you please.’

He directed her to a door beside the major’s study and opened it for her.

After the dazzling brightness of the hall, the room seemed very dark, but when her eyes grew accustomed she saw that she was alone and she relaxed a little, looking about her with interest. It was a long room with a lofty ceiling, ornately plastered. The crimson walls were covered with large paintings, mostly of men and women in grey wigs and the fashions of the last century, but there was one painting beside the fireplace of a young lady with her hair tumbling like dark, polished mahogany over her shoulders. She wore a high-waisted gown and the artist had cleverly painted the skirts as if they had just been caught by a soft breeze. Zelah stepped closer. There was a direct, fearless stare in the girl’s dark eyes and a firm set to those sculpted lips. She looked strangely familiar.

‘My sister, Serena.’

She jumped and turned to find the major standing behind her.

‘Oh, I did not hear you—’ She almost said she had not heard the scuffing of his dragging foot. Flustered, she turned back to the painting. ‘She is very like you, I think.’

He gave a bark of laughter.

‘Not in looks, I hope! Nor in temperament. She was not the least serene, which is why Jasper and I renamed her Sally! Very wild and headstrong. At least she was until she married. Now she is a model of respectability.’

‘And is she happy?’

‘Extremely.’

She took a last look at the painting, then turned to her host. Although she had seen him without his beard that afternoon, his clean-shaven appearance still surprised her. He had brushed his thick, dark hair and tied it back with a ribbon. The ragged scar was now visible, stretching from his left temple, down through his eyebrow and left cheekbone to his chin, dragging down the left side of his mouth.

The look in his eyes was guarded with just a touch of defiance. Zelah realised he expected her to look away, revolted by the sight of his scarred face. She was determined not to do that and, not knowing quite what to do, she smiled at him.

‘You look very smart, sir.’

The wary look disappeared.

‘Thank you, ma’am.’ He gave a little bow. ‘I believe this is still the standard wear for dinner.’

They both knew she was not referring to the black evening coat and snowy waistcoat and knee breeches, but her smile grew.

‘Your dress is very different from the first time I saw you.’

‘I keep that old coat for when I am working in the woods. It is loose across the shoulders and allows me to swing the axe.’ He paused. ‘Graddon informs me that there has been a slight upset in the kitchen and dinner is not quite ready.’ A faint smile lifted the good side of his mouth. ‘Mrs Graddon is an estimable creature, but I understand my telling her I would be entertaining a guest caused the sauce to curdle.’

‘Sauces are notoriously difficult,’ she said carefully.

He held out his arm to her.

‘Perhaps you would care to step out on to the terrace while we wait?’

Zelah nodded her assent and took his proffered arm. He walked her across the room to the door set between the long windows.

‘You see the house has been sadly neglected,’ he said as he led her out of doors. He bent to pluck a straggling weed from between the paving slabs and tossed it aside.

‘The rose garden has survived quite well,’ she observed. ‘It needs only a little work to bring it into some sort of order.’

‘Really? When I last looked the plants were quite out of control.’

‘They need pruning, that is all. And even the shrubbery is not, I think, beyond saving. Cut the plants back hard and they will grow better than ever next year.’

‘Pity the same thing does not apply to people.’

She had been happily imagining how the gardens might look, but his bitter words brought her back to reality. She might be able to forget her companion’s disfigurement, but he could not. A sudden little breeze made her shiver.

‘I beg your pardon. It is too early in the year to be out of doors.’

The major put his hand out to help her arrange her stole. Did it rest on her shoulder a moment longer than was necessary, or was that her imagination? He was standing very close, looming over her. A sense of his physical power enveloped her.

This is all nonsense, she told herself sternly, but the sensation persisted. Run, Zelah, go now!

‘Perhaps, ma’am, we should go back inside.’

He put his hand beneath her arm and she almost jumped away, her nerves jangling. Immediately he released her, standing back so that she could precede him into the room. He had turned slightly, so that he presented only the uninjured side of his face to her and silently Zelah berated herself. Major Coale was acting as a gentleman, while she was displaying the sort of ill-mannered self-consciousness that she despised. That was no way to repay her host’s kindness. She must try harder.

He escorted her to the dining room, where Zelah’s stretched nerves tightened even more. A place was set at the head of the table and another on its right hand. It was far too intimate. She cleared her throat.

‘Major, would—would you object if I made slight adjustment to the setting?’

She flushed under his questioning gaze, but he merely shrugged.

‘As you wish.’

She squared her shoulders. The setting at the head of the table was soon moved to the left hand, so that they would be facing each other. She had to steel herself to turn back to the major.

The silence as he observed her work was unnerving, but Zelah comforted herself that the worst he could do was order her to go back to her room and eat alone. At last those piercing eyes moved to her face.

‘Do you think you will be safer with five foot of mahogany between us?’

‘It is more … seemly.’

‘Seemly! If that is your worry, perhaps we should ask Mrs Graddon to join us.’

Zelah’s anger flared.

‘I agreed to dine with you, sir, but to sit so close—’

‘Yes, yes, it would be unseemly! So be it. For God’s sake let us sit down before the food arrives.’

He stalked to her chair and held it out. She sat down. He took his own seat in silence.

‘I beg your pardon,’ said Zelah. ‘I did not mean to put you to all this trouble.’

It was a poor enough olive branch, but it worked. Major Coale gave her a rueful look.

‘And I beg your pardon for losing my temper. My manners have lost their polish.’

The door opened and the footmen came in with the first dishes.

After such an unpromising start Zelah feared that conversation might be difficult, but she was wrong. The major proved an excellent host, exerting himself to entertain. He persuaded her to take a little from every dish on the table and kept her glass filled while regaling her with amusing anecdotes. She forgot her nerves and began to enjoy herself. They discussed music and art, the theatre and politics, neither noticing when the footmen came in to light the candles, and by the time they finished their meal Zelah was exchanging opinions with the major as if they were old friends. When the covers were removed the major asked her about Nicky and she found herself chatting away, telling him how they filled their days.

‘Hannah is so good with him, too,’ she ended. ‘Thank you for sending her to help me.’

‘It was Mrs Graddon who suggested it, knowing the girl comes from a large family.’

‘Nicky adores her and would much rather play spillikins with her than attend to his lessons.’

His brows rose. ‘Don’t tell me you are making him work while he is laid up sick?’

She laughed.

‘No, no, but I like him to read to me a little each day and to write a short note to his mama. He is reluctant to apply himself, but I find that with a little encouragement he is willing enough. And it is very good practice for me.’

‘Practice?’

‘Yes, for when I become a governess.’

She selected a sweetmeat as the butler came up to refill her glass. The major waved him away.

‘Thank you, Graddon, that will be all. Leave the Madeira and I will serve Miss Pentewan.’ He waited until they were alone before he spoke again.

‘Forgive my impertinence, ma’am, but you do not look old enough to be a governess.’

She sat up very straight.

‘I am two-and-twenty, Major Coale. Not that it is any of your business!’ She bit her lip. ‘I beg you pardon. I am a guest in your house—’

‘Guest be damned,’ he interrupted roughly. ‘That is no reason you should endure my incivility. Being a guest here should not put you under any obligation.’

Zelah chuckled, her spurt of anger dying as quickly as it had come.

‘Of course I am under an obligation to you, Major. You have gone to great lengths to accommodate us. And how could I not forgive you for paying me such a handsome compliment?’

He gave a short laugh and filled their glasses.

‘So why are you intent on becoming a governess? Can Buckland not support you?’

‘Why should he do so, if I can earn my own living?’

‘I should not allow my sister to become a governess.’

‘But your father was a viscount. Reginald is only a brother by marriage, and besides, he has a family of his own to support.’ She picked up the glass he had filled for her and tasted it carefully. She had never had Madeira before, but she found she enjoyed the warm, nutty flavour. ‘I would not add to his burdens.’

He reached out, his hand hovering over the sweetmeats as he said lightly, ‘Perhaps you should look for a husband.’

‘No!’

The vehemence brought his head up immediately and she was subjected to a piercing gaze. She decided to be flippant.

‘As I am penniless, and notoriously difficult to please, I think that might be far too difficult. I do like this wine—is it usual for gentlemen to drink it at the end of a meal? I know Reginald prefers brandy.’

To her relief he followed her lead and their conversation moved back to safer waters. She took another glass of Madeira and decided it must be her last. She was in danger of becoming light-headed. Darkness closed around them. The butler came in silently to light more candles in the room and draw the curtains against the night, but they made no move to leave the table, there was still so much to say.

The major turned to speak to Graddon and Zelah studied his profile. How handsome he must have been before his face was sliced open by a French sabre. It was a momentary thought, banished as soon as it occurred, but it filled her with sadness.

‘You are very quiet, Miss Pentewan.’

His words brought her back to the present and she blushed, not knowing how to respond. In the end she decided upon the truth.

‘I was thinking about your face.’

Immediately he seemed to withdraw from her.

‘That is why I wanted you upon my right hand, to spare you that revulsion.’

She shook her head.

‘It does not revolt me.’

‘I should not have shaved off my beard!’

‘Yes, you should, you look so much better, only—’

‘Yes, madam? Only what?’ The hard note in his voice warned her not to continue, but she ignored it.

‘Your hair,’ she said breathlessly. ‘I am surprised your valet does not wish to cut it.’

‘I have no valet. Graddon does all I need.’

‘But I thought he was a butler …’

‘He does what is necessary. He was with me in Spain and brought me back to England. He stayed with me, helped me to come to terms with my new life.’

‘And Mrs Graddon?’

‘She was housemaid at Markham and decided to marry Graddon and come with him when I moved here.’ He raised his glass, his lip curling into something very like a sneer. ‘You see, my misfortune is their gain.’

She frowned.

‘Please do not belittle them. They are devoted to you.’

‘I stand corrected,’ he said stiffly. ‘I beg your pardon and theirs.’

‘I think you would look much better with your hair cut short. It is very much the fashion now, you know.’

He leaned closer, a belligerent, challenging look in his eye. It took all her courage not to turn away.

‘I need it long,’ he said savagely. ‘Then I can bring it down, thus, and hide this monstrous deformation.’ He pulled the ribbon from his hair and shook the dark curtain down over his face. ‘Surely that is better? I would not want to alarm the ladies and children!’

He was glaring at her, eyes narrowed, his mouth a thin, taut line, one side pulled lower by the dragging scar.

‘Nicky is not afraid of you,’ she said softly. ‘Nor do you frighten me.’

For a long, interminable time she held his eyes, hoping he would read not pity but sympathy and understanding in her gaze. He was a proud man and she was dismayed to think he was hiding from the world. To her relief, his angry look faded.

‘So would you have me trust myself to a country barber?’ he growled. ‘I think not, Miss Pentewan. Perhaps next time I go to London—’

‘I could cut it for you.’ She sat back, shocked by her own temerity. ‘I am quite adept at cutting hair, although I have no idea where the skill comes from. I was always used to trim my father’s hair, and since I have been at West Barton I have cut Nicky’s. I am sure no one could tell it was not professionally done.’

He was frowning at her now. She had gone too far. The wine had made her reckless and her wretched tongue had let her down. Major Coale jumped up and strode to tug at the bell pull. He was summoning a footman to escort her to her room.

‘Graddon, fetch scissors and my comb, if you please.’ He caught her eye, a glint in his own. ‘Very well, Miss Pentewan, let us put you to the test.’

‘What? I—’ She swallowed. ‘Are you sure it is what you want?’

‘Are you losing your nerve, madam?’

Zelah quite thought that she was. Two voices warred within her: one told her that to dine alone with a gentleman who was not related to her was improper enough, but to cut the man’s hair would put her beyond the pale. The other whispered that it was her Christian duty to help him quit his self-imposed exile.

The glint in his eyes turned into a gleam. He was laughing at her and her courage rose.

‘Not at all. Let us do it!’

‘Major, are you quite sure you want me to do this?’

He was sitting on a chair by the table and Zelah was standing behind him, comb in hand. They had rearranged the candelabra to give the best light possible and the dark locks gleamed, thick and glossy around his head, spreading out like ebony across his shoulders. The enormity of what she was about to do made her hesitate.

The major waved his hand.

‘Yes. I may change my mind when I am sober, but for now I want you to cut it.’

Zelah took a deep breath. It was too late to go back now, they had agreed. Besides, argued that wickedly seductive voice in her head, no one need ever know. She picked up the scissors and moved closer until her skirts were brushing his shoulder. It felt strange, uncomfortable, like standing over a sleeping tiger. Thrusting aside such fanciful thoughts, she took a secure grip of the scissors and began. His hair was like silk beneath her fingers. She lifted one dark lock and applied the scissors. They cut through it with a whisper. As she continued her confidence grew, as did the pile of black tresses on the floor.

His hair was naturally curly and she had seen enough pencil drawings of gentlemen with their hair à la Brutus since she had arrived at West Barton to recreate the style from memory—Reginald and Maria might live in a remote area of Exmoor, but they were both avid followers of the ton, receiving a constant stream of periodicals and letters from friends in London advising them of the latest fashions. She cut, combed and coaxed the major’s hair into place. It needed no pomade or grease to make it curl around his collar and his ears. She brushed the tendrils forwards around his face, as she had seen in the fashion plates. Her fingers touched the scar and he flinched. Immediately she drew back.

‘Did I hurt you?’

‘No. Carry on.’

Carefully she finished her work, combing and snipping off a few straggling ends until she was satisfied with the result. It was not strictly necessary, but she could not resist running her fingers though his glossy, thick hair one final time.

‘There.’ She brushed the loose hair from his shoulders. ‘It is finished.’

‘Very well, Delilah, let us see what you have done to me.’

He picked up one of the candelabra and walked over to a mirror.

Zelah held her breath as he regarded his image. In the candlelight the ugly gash down his face was still visible, but it seemed diminished by the new hairstyle. The sleek black locks were brushed forwards to curl about his wide brow, accentuating the strong lines of his face.

‘Well, Miss Pentewan, I congratulate you. Perhaps you should not be looking for a post as a governess, after all. You should offer your services as a coiffeuse.’

Relief made her laugh out loud. She said daringly, ‘You look very handsome, Major.’

He turned away from the mirror and made a noise between a growl and a cough.

‘Aye, well, enough of that. It is time I sent you back to the sick room, madam. You will need to be up betimes.’

‘Yes, of course.’ She cast a conscience-stricken look at the clock. ‘Poor Hannah has been alone with Nicky for hours.’ She held out her hand to him. ‘Goodnight, sir. I hope we shall see you in the morning before we leave?’

Again that clearing of the throat and he would not meet her eyes.

‘Perhaps. Goodnight, Miss Pentewan.’ He took her hand, his grip tightening for a second. ‘And thank you.’

Chapter Three

The following morning Reginald drove over in his travelling chaise, which Maria had filled with feather bolsters and pillows to protect Nicky during the long journey home. Nicky looked around as his father carried him tenderly out of the house.

‘Is Major Coale not here, Papa?’

‘He sends his apologies, Master Nick,’ said Graddon in a fatherly way. ‘He went off early today to the long meadow to oversee the hedgelaying.’

‘But I wanted to say goodbye to him!’

Nicky’s disappointed wail touched a chord in Zelah: she too would have liked to see the major. However, she was heartened by Reginald’s response.