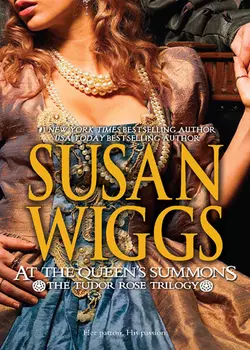

At The Queen′s Summons

Susan Wiggs

Feisty orphan Pippa de Lacey lives by wit and skill as a London street performer. But when her sharp tongue gets her into serious trouble, she throws herself upon the mercy of Irish chieftain Aidan O'Donoghue.Pippa provides a welcome diversion for Aidan as he awaits an audience with the queen, who holds his people's fate in her hands. Amused at first, he becomes obsessed with the audacious waif who claims his patronage.Rash and impetuous, their unlikely alliance reverberates with desire and the tantalizing promise of a life each has always wanted—but never dreamed of attaining.

Praise for the novels of

#1 New York Times bestselling author

SUSAN WIGGS

“Wiggs is one of our best observers of stories of the heart. Maybe that is because she knows how to capture emotion on virtually every page of every book.”

—Salem Statesman-Journal

“Susan Wiggs is a rare talent! Boisterous, passionate, exciting! The characters leap off the page and into your heart!”

—Literary Times

“[A] lovely, moving novel with an engaging heroine…Readers who like Nora Roberts and Susan Elizabeth Phillips will enjoy Wiggs’s latest. Highly recommended.”

—Library Journal on Just Breathe [starred review]

“Tender and heartbreaking…a beautiful novel.”

—Luanne Rice on Just Breathe

“Another excellent title [in] her already outstanding body of work.”

—Booklist on Table for Five [starred review]

“With the ease of a master, Wiggs introduces complicated, flesh-and-blood characters into her idyllic but identifiable small-town setting.”

—Publishers Weekly on The Winter Lodge [starred review, a PW Best Book of 2007]

At the Queen’s Summons

Susan Wiggs

Dedicated with love to my friend,

mentor and fellow writer,

Betty Traylor Gyenes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to:

Barbara Dawson Smith, Betty Traylor Gyenes and Joyce Bell, for providing all the generous hours of critique and support

The many members of the GEnie® Romance Exchange, an electronic bulletin board of scholars, fools, dreamers and wisewomen

The Bord Failte of County Kerry, Ireland

And the sublime Trish Jensen for her eagle-eyed proofreading skills.

Contents

Part One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Part Two

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Part One

Now is this golden crown like a deep well

That owes two buckets filling one another;

The emptier ever dancing in the air,

The other down, unseen and full of water;

That bucket down and full of tears am I,

Drinking my griefs, whilst you mount up on high.

—William Shakespeare

Richard II (IV, i, 184)

From the Annals of Innisfallen

In accordance with ancient and honorable tradition, I, Revelin of Innisfallen, take pen in hand to relate the noble and right valiant histories of the clan O Donoghue. This task has been done by my uncle and his uncle before him, since time no man can remember.

Canons we are, of the most holy Order of St. Augustine, and by the grace of God our home is the beechwooded lake isle called Innisfallen.

Those before me filled these pages with tales of fabled heroes, mighty battles, cattle raids and perilous adventures. Now the role of the O Donoghue Mór has fallen to Aidan, and my work is to chronicle his exploits.

But—may the high King of Heaven forgive my clumsy pen—I know not where to begin. For Aidan O Donoghue is like no man I have ever known, and never has a chieftain been faced with such a challenge.

The O Donoghue Mór, known to the English as Lord of Castleross, has been summoned to London by the she-king who claims the right to rule us. I wonder, with shameful, un-Christian relish, after clapping eyes on Aidan O Donoghue and his entourage, if Her Sassenach Majesty will come to regret the summons.

—Revelin of Innisfallen

One

“How many noblemen does it take to light a candle?” asked a laughing voice.

Aidan O Donoghue lifted a hand to halt his escort. The English voice intrigued him. In the crowded London street behind him, his personal guard of a hundred gallowglass instantly stopped their purposeful march.

“How many?” someone yelled.

“Three!” came the shout from the center of St. Paul’s churchyard.

Aidan nudged his horse forward into the area around the great church. A sea of booksellers, paupers, tricksters, merchants and rogues seethed around him. He could see the speaker now, just barely, a little lightning bolt of mad energy on the church steps.

“One to call a servant to pour the sack—” she reeled in mock drunkenness “—one to beat the servant senseless, one to botch the job and one to blame it on the French.”

Her listeners hooted in derision. Then a man yelled, “That’s four, wench!”

Aidan flexed his legs to stand in the stirrups. Stirrups.Until a fortnight ago, he had never even used such a device, or a curbed bit, either. Perhaps, after all, there was some use in this visit to England. He could do without all the fancy draping Lord Lumley had insisted upon, though. Horses were horses in Ireland, not poppet dolls dressed in satin and plumes.

Elevated in the stirrups, he caught another glimpse of the girl: battered hat crammed down on matted hair, dirty, laughing face, ragged clothes.

“Well,” she said to the heckler, “I never said I could count, unless it be the coppers you toss me.”

A sly-looking man in tight hose joined her on the steps. “I saves me coppers for them what entertains me.” Boldly he snaked an arm around the girl and drew her snugly against him.

She slapped her hands against her cheeks in mock surprise. “Sir! Your codpiece flatters my vanity!”

The clink of coins punctuated a spate of laughter. A fat man near the girl held three flaming torches aloft. “Sixpence says you can’t juggle them.”

“Ninepence says I can, sure as Queen Elizabeth’s white arse sits upon the throne,” hollered the girl, deftly catching the torches and tossing them into motion.

Aidan guided his horse closer still. The huge Florentine mare he’d christened Grania earned a few dirty looks and muttered curses from people she nudged out of the way, but none challenged Aidan. Although the Londoners could not know he was the O Donoghue Mór of Ross Castle, they seemed to sense that he and his horse were not a pair to be trifled with. Perhaps it was the prodigious size of the horse; perhaps it was the dangerous, wintry blue of the rider’s eyes; but most likely it was the naked blade of the shortsword strapped to his thigh.

He left his massive escort milling outside the churchyard and passing the time by intimidating the Londoners. When he drew close to the street urchin, she was juggling the torches. The flaming brands formed a whirling frame for her grinning, sooty face.

She was an odd colleen, looking as if she had been stitched together from leftovers: wide eyes and wider mouth, button nose, and spiky hair better suited to a boy. She wore a chemise without a bodice, drooping canion trews and boots so old they might have been relics of the last century.

Yet her Maker had, by some foible, gifted her with the most dainty and deft pair of hands Aidan had ever seen. Round and round went the torches, and when she called for another, it joined the spinning circle with ease. Hand to hand she passed them, faster and faster. The big-bellied man then tossed her a shiny red apple.

She laughed and said, “Eh, Dove, you don’t fear I’ll tempt a man to sin?”

Her companion guffawed. “I like me wenches made of more than gristle and bad jests, Pippa girl.”

She took no offense, and while Aidan silently mouthed the strange name, someone tossed a dead fish into the spinning mix.

Aidan cringed, but the girl called Pippa took the new challenge in stride. “Seems I’ve caught one of your relatives, Mort,” she said to the man who had procured the fish.

The crowd roared its approval. A few red-heeled gentlemen dropped coins upon the steps. Even after a fortnight in London Aidan could ill understand the Sassenach. They would as lief toss coins to a street performer as see her hanged for vagrancy.

He felt something rub his leg and looked down. A sleepy-looking whore curved her hand around his thigh, fingers inching toward the horn-handled dagger tucked into the top of his boot.

With a dismissive smile, Aidan removed the whore’s hand. “You’ll find naught but ill fortune there, mistress.”

She drew back her lips in a sneer. The French pox had begun to rot her gums. “Irish,” she said, backing away. “Chaste as a priest, eh?”

Before he could respond, a high-pitched mew split the air, and the mare’s ears pricked up. Aidan spied a half-grown cat flying through the air toward Pippa.

“Juggle that,” a man shouted, howling with laughter.

“Jesu!” she said. Her hands seemed to be working of their own accord, keeping the objects spinning even as she tried to step out of range of the flying cat. But she caught it and managed to toss it from one hand to the next before the terrified creature leaped onto her head and clung there, claws sinking into the battered hat.

The hat slumped over the juggler’s eyes, blinding her.

Torches, apple and fish all clattered to the ground. The skinny man called Mort stomped out the flames. The fat man called Dove tried to help but trod instead upon the slimy fish. He skated forward, sleeves ripping as his pudgy arms cartwheeled. Just as he lost his balance, his flailing fist slammed into a spectator, who immediately threw himself into the brawl. With shouts of glee, others joined the fisticuffs. It was all Aidan could do to keep the mare from rearing.

Still blinded by the cat, the girl stumbled forward, hands outstretched. She caught the end of a bookseller’s cart. Cat and hat came off as one, and the crazed feline climbed a stack of tomes, toppling them into the mud of the churchyard.

“Imbecile!” the bookseller screeched, lunging at Pippa.

Dove had taken on several opponents by now. With a wet thwap, he slapped one across the face with the dead fish.

Pippa grasped the end of the cart and lifted. The remaining books slid down and slammed into the bookseller, knocking him backward to the ground.

“Where’s my ninepence?” she demanded, surveying the steps. People were too busy brawling to respond. She snatched up a stray copper and shoved it into the voluminous sack tied to her waist with a frayed rope. Then she fled, darting toward St. Paul’s Cross, a tall monument surrounded by an open rotunda. The bookseller followed, and now he had an ally—his wife, a formidable lady with arms like large hams.

“Come back here, you evil little monkey,” the wife roared. “This day shall be your last!”

Dove was enjoying the fight by now. He had his opponent by the neck and was playing with the man’s nose, slapping it back and forth and laughing.

Mort, his companion, was equally gleeful, squaring off with the whore who had approached Aidan earlier.

Pippa led a chase around the cross, the bookseller and his wife in hot pursuit.

More spectators joined in the fray. The horse backed up, eyes rolling in fear. Aidan made a crooning sound and stroked her neck, but he did not leave the square. He simply watched the fight and thought, for the hundredth time since his arrival, what a strange, foul and fascinating place London was. Just for a moment, he forgot the reason he had come. He turned spectator, giving his full attention to the antics of Pippa and her companions.

So this was St. Paul’s, the throbbing heart of the city. It was more meeting place than house of worship to be sure, and this did not surprise Aidan. The Sassenach were a people who clung feebly to an anemic faith; all the passion and pageantry had been bled out of the church by the Rome-hating Reformers.

The steeple, long broken but never yet repaired, shadowed a collection of beggars and merchants, strolling players and thieves, whores and tricksters. At the opposite corner of the square stood a gentleman and a liveried constable. Prodded by the screeched urging of the bookseller’s wife, they reluctantly moved in closer. The bookseller had cornered Pippa on the top step.

“Mort!” she cried. “Dove, help me!” Her companions promptly disappeared into the crowd. “Bastards!” she yelled after them. “Geld and splay you both!”

The bookseller barreled toward her. She stooped and picked up the dead fish, took keen aim at the bookseller and let fly.

The bookseller ducked. The fish struck the approaching gentleman in the face. Leaving slime and scales in its wake, the fish slid down the front of his silk brocade doublet and landed upon his slashed velvet court slippers.

Pippa froze and gawked in horror at the gentleman. “Oops,” she said.

“Indeed.” He fixed her with a fiery eye of accusation. Without even blinking, he motioned to the liveried constable.

“Sir,” he said.

“Aye, my lord?”

“Arrest this, er, rodent.”

Pippa took a step back, praying the way was clear to make a run for it. Her backside collided with the solid bulk of the bookseller’s wife.

“Oops,” Pippa said again. Her hopes sank like a weighted corpse in the Thames.

“Let’s see you worm your way out of this fix, missy,” the woman hissed in her ear.

“Thank you,” Pippa said cordially enough. “I intend to do just that.” She put on her brightest I’m-an-urchin grin and tugged at a forelock. She had recently hacked off her hair to get rid of a particularly stubborn case of lice. “Good morrow, Your Worship.”

The nobleman stroked his beard. “Not particularly good for you, scamp,” he said. “Are you aware of the laws against strolling players?”

Her gaze burning with indignation, she looked right and left. “Strolling players?” she said with heated outrage. “Who? Where? To God, what is this city coming to that such vermin as strolling players would run loose in the streets?”

As she huffed up her chest, she furtively searched the crowd for Dove and Mortlock. Like the fearless gallants she knew them to be, her companions had vanished.

For a moment, her gaze settled on the man on the horse. She had noticed him earlier, richly garbed and well mounted, with a foreign air about him she could not readily place.

“You mean to say,” the constable yelled at her, “that you are not a strolling player?”

“Sir, bite your tongue,” she fired off. “I’m…I am…” She took a deep breath and plucked out a ready falsehood. “An evangelist, my lord. Come to preach the Good Word to the unconverted of St. Paul’s.”

The haughty gentleman lifted one eyebrow high. “The Good Word, eh? And what might that be?”

“You know,” she said with an excess of patience. “The gospel according to Saint John.” She paused, searching her memory for more tidbits gleaned from days she had spent huddled and hiding in church. An inveterate collector of colorful words and phrases, she took pride in using them. “The pistol of Saint Paul to the fossils.”

“Ah.” The constable’s hands shot out. In a swift movement, he pinned her to the wall beside the si quis door. She twisted around to look longingly into the nave where the soaring stone pillars marched along Paul’s Walk. Like a well-seasoned rat, she knew every cranny and cubbyhole of the church. If she could get inside, she could find another way out.

“You’d best do better than that,” the constable said, “else I’ll nail your foolish ears to the stocks.”

She winced just thinking about it. “Very well, then.” She heaved a dramatic sigh. “Here’s the truth.”

A small crowd had gathered, probably hoping to see nails driven through her ears. The stranger on horseback dismounted, passed his reins to a stirrup runner and drew closer.

The lust for blood was universal, Pippa decided. But perhaps not. Despite his savage-looking face and flowing black hair, the man had an air of reckless splendor that fascinated her. She took a deep breath. “Actually, sir, I am a strolling player. But I have a nobleman’s warrant,” she finished triumphantly.

“Have you, then?” His Lordship winked at the constable.

“Oh, aye, sir, upon my word.” She hated it when gentlemen got into a playful mood. Their idea of play usually involved mutilating defenseless people or animals.

“And who might this patron be?”

“Why, Robert Dudley himself, the Earl of Leicester.” Pippa threw back her shoulders proudly. How clever of her to think of the queen’s perpetual favorite. She nudged the constable in the ribs, none too gently. “He’s the queen’s lover, you know, so you’d best not irritate me.”

A few of her listeners’ mouths dropped open. The nobleman’s face drained to a sick gray hue; then hot color surged to his cheeks and jowls.

The constable gripped Pippa by the ear. “You lose, rodent.” With a flourish, he indicated the haughty man. “That is the Earl of Leicester, and I don’t believe he’s ever seen you before.”

“If I had, I would certainly remember,” said Leicester.

She swallowed hard. “Can I change my mind?”

“Please do,” Leicester invited.

“My patron is actually Lord Shelbourne.” She eyed the men dubiously. “Er, he is still among the living, is he not?”

“Oh, indeed.”

Pippa breathed a sigh of relief. “Well, then. He is my patron. Now I had best be go—”

“Not so fast.” The grip on her ear tightened. Tears burned her nose and eyes. “He is locked up in the Tower, his lands forfeit and his title attainted.”

Pippa gasped. Her mouth formed an O.

“I know,” said Leicester. “Oops.”

For the first time, her aplomb flagged. Usually she was nimble enough of wit and fleet enough of foot to get out of these scrapes. The thought of the stocks loomed large in her mind. This time, she was nailed indeed.

She decided to try a last ditch effort to gain a patron. Who? Lord Burghley? No, he was too old and humorless. Walsingham? No, not with his Puritan leanings. The queen herself, then. By the time Pippa’s claim could be verified, she would be long gone.

Then she spied the tall stranger looming at the back of the throng. Though he was most certainly foreign, he watched her with an interest that might even be colored by sympathy. Perhaps he spoke no English.

“Actually,” she said, “he is my patron.” She pointed in the direction of the foreigner. Be Dutch, she prayed silently. Or Swiss. Or drunk. Or stupid. Just play along.

The earl and the constable swung around, craning their necks to see. They did not have far to crane. The stranger stood like an oak tree amid low weeds, head and shoulders taller, oddly placid as the usual St. Paul’s crowd surged and seethed and whispered around him.

Pippa craned, too, getting her first close look at him. Their gazes locked. She, who had experienced practically everything in her uncounted years, felt a jolt of something so new and profound that she simply had no name for the feeling.

His eyes were a glittering, sapphire blue, but it was not the color or the startling face from which the eyes stared that mattered. A mysterious force dwelt behind the eyes, or in their depths. Awareness flew between Pippa and the stranger; she felt it enter her, dive into her depths like sunlight breaking through shadow.

Old Mab, the woman who had raised Pippa, would have called it magic.

Old Mab would have been right, for once.

The earl cupped his hands around his mouth. “You, sir!”

The foreigner pressed a very large hand to his much larger chest and raised a questioning black brow.

“Aye, sir,” called the earl. “This elvish female claims she is performing under your warrant. Is that so, sir?”

The crowd waited. The earl and the constable waited. When they looked away from her, Pippa clasped her hands and looked pleadingly at the stranger. Her ear was going numb in the pinch of the constable.

Pleading looks were her specialty. She had practiced them for years, using her large, pale eyes to prize coppers and crusts from passing strangers.

The foreigner raised a hand. Into the alleyway behind him flooded a troop of—Pippa was not certain what they were.

They moved about in a great mob like soldiers, but instead of tunics these men wore horrible gray animal hides, wolfskins by the look of them. They carried battleaxes with long handles. Some had shaved heads; others wore their hair loose and wild, tumbling over their brows.

Everyone moved aside when they entered the yard. Pippa did not blame the Londoners for shrinking in fear. She would have shrunk herself, but for the iron grip of the constable.

“Is that what the colleen said, then?” He strode forward. He spoke English, damn him. He had a very strange accent, but it was English.

He was huge. As a rule, Pippa liked big men. Big men and big dogs. They seemed to have less need to swagger and boast and be cruel than small ones. This man actually had a slight swagger, but she realized it was his way of squeezing a path through the crowd.

His hair was black. It gleamed in the morning light with shards of indigo and violet, flowing over his shoulders. A slim ebony strand was ornamented with a strap of rawhide and beads.

Pippa chided herself for being fascinated by a tall man with sapphire eyes. She should be taking the opportunity to run for cover rather than gawking like a Bedlamite at the foreigner. At the very least, she should be cooking up a lie to explain how, without his knowledge, she had come to be under his protection.

He reached the steps in front of the door, where she stood between the constable and Leicester. His flame-blue eyes glared at the constable until the man relinquished his grasp on Pippa’s ear.

Sighing with relief, she rubbed the abused, throbbing ear.

“I am Aidan,” the stranger said, “the O Donoghue Mór.”

A Moor! Immediately Pippa fell to her knees and snatched the hem of his deep blue mantle, bringing the dusty silk to her lips. The fabric felt heavy and rich, smooth as water and as exotic as the man himself.

“Do you not remember, Your Preeminence?” she cried, knowing important men adored honorary titles. “How you ever so tenderly extended your warrant of protection to my poor, downtrodden self so that I’d not starve?” As she rambled on, she found a most interesting bone-handled knife tucked into the cuff of his tall boot. Unable to resist, she stole it, her movements so fluid and furtive that no one saw her conceal it in her own boot.

Her gaze traveled upward over a strong leg. The sight set off a curious tingling. Strapped to his thigh was a shortsword as sharp and dangerous looking as the man himself.

“You said you did not wish me to suffer the tortures of Clink Prison, nor did you want my pitiful weight forever on your delicate conscience, making you terrified to burn in hell for eternity because you let a defenseless woman fall victim to—”

“Yes,” said the Moor.

She dropped his hem and stared up at him. “What?” she asked stupidly.

“Yes indeed, I remember, Mistress…er—”

“Trueheart,” she supplied helpfully, plucking a favorite name from the arsenal of her imagination. “Pippa Trueheart.”

The Moor faced Leicester. The smaller man gaped up at him. “There you are, then,” said the black-haired lord. “Mistress Pippa Trueheart is performing under my warrant.”

With a huge bear paw of a hand, he took her arm and brought her to her feet. “I do confess the little baggage is unmanageable at times and did slip away for today’s performance. From now on I shall keep her in closer tow.”

Leicester nodded and stroked his narrow beard. “That would be most appreciated, my lord of Castleross.”

The constable looked at the Moor’s huge escort. The members of the escort glared back, and the constable smiled nervously.

The Moor turned and addressed his fierce servants in a tongue so foreign, so unfamiliar, that Pippa did not recognize a single syllable of it. That was odd, for she had a keen and discerning ear for languages.

The skin-clad men marched out of the churchyard and clumped down Paternoster Row. The lad who served as stirrup runner led the big horse away. The Moor took hold of Pippa’s arm.

“Let’s go, a storin,” he said.

“Why do you call me a storin?”

“It is an endearment meaning ‘treasure.’”

“Oh. No one’s ever called me a treasure before. A trial, perhaps.”

His lilting accent and the scent of the wind that clung in his hair and mantle sent a thrill through her. She had never been rescued in her life, and certainly not by such a specimen as this black-haired lord.

As they walked toward the low gate linking St. Paul’s with Cheapside, she looked sideways at him. “You seem rather nice for a Moor.” She passed through the gate he held open for her.

“A Moor, you say? Mistress, sure and I am no Moor.”

“But you said you were Aidan, the O Donoghue Moor.”

He laughed. She stopped in her tracks. She earned her living by making people laugh, so she should be used to the sound of it, but this was different. His laughter was so deep and rich that she imagined she could actually see it, flowing like a banner of dark silk on the breeze.

He threw back his great, shaggy head. She saw that he had a full set of teeth. The eyes, blazing blue like the hearts of flames, drew her in with that same compelling magic she had felt earlier.

He was beginning to make her nervous.

“Why do you laugh?” she asked.

“Mór,” he said. “I am the O Donoghue Mór. It means ‘great.’”

“Ah.” She nodded sagely, pretending she had known all along. “And are you?” She let her gaze travel the entire length of him, lingering on the more interesting parts.

God was a woman, Pippa thought with sudden certainty. Only a woman would create a man like the O Donoghue, forming such toothsome parts into an even more delectable whole. “Aside from the obvious, I mean.”

Mirth still glowed about him, though his laughter had ceased. He touched her cheek, a surprisingly tender gesture, and said, “That, a stor, depends on whom you ask.”

The light, brief touch shook Pippa to the core, though she refused to show it. When people touched her, it was to box her ears or send her packing, not to caress and comfort.

“And how does one address a man so great as yourself?” she asked in a teasing voice. “Your Worship? Your Excellency?” She winked. “Your Hugeness?”

He laughed again. “For a lowly player, you know some big words. Saucy ones, too.”

“I collect them. I’m a very fast learner.”

“Not fast enough to stay out of trouble today, it seems.” He took her hand and continued walking eastward along Cheapside. They passed the pissing conduit and then the Eleanor Cross decked with gilded statues.

Pippa saw the foreigner frowning up at them. “The Puritans mutilate the figures,” she explained, taking charge of his introduction to London. “They mislike graven images. At the Standard yonder, you might see real mutilated bodies. Dove said a murderer was executed Tuesday last.”

When they reached the square pillar, they saw no corpse, but the usual motley assortment of students and ’prentices, convicts with branded faces, beggars, bawds, and a pair of soldiers tied to a cart and being flogged as they were conveyed to prison. Leavening all the grimness was the backdrop of Goldsmith Row, shiny white houses with black beams and gilt wooden statuary. The O Donoghue took it all in with quiet, thoughtful interest. He made no comment, though he discreetly passed coppers from his cupped hand to the beggars.

From the corner of her eye, Pippa saw Dove and Mortlock standing by an upended barrel near the Old ’Change. They were running a game with weighted dice and hollow coins. They smiled and waved as if nothing had happened, as if they had not just deserted her in a moment of dire peril.

She poked her nose in the air, haughty as any grande dame, and put her grubby hand on the arm of the great O Donoghue. Let Dove and Mort wonder and squirm with curiosity. She belonged to a lofty nobleman now. She belonged to the O Donoghue Mór.

Aidan was wondering how to get rid of the girl. She trotted at his side, chattering away about riots and rebels and boat races down the Thames. There was precious little for him to do in London while the queen left him cooling his heels, but that did not mean he needed to amuse himself with a pixielike female from St. Paul’s.

Still, there was the matter of his knife, which she had stolen while groveling at his hem. Perhaps he ought to let her keep it, though, as the price of a morning’s diversion. The lass was nothing if not wildly entertaining.

He shot a glance sideways, and the sight of her clutched unexpectedly at his heart. She bounced along with all the pride of a child wearing her first pair of shoes. Yet beneath the grime on her face, he could see the smudges of sleeplessness under her soft green eyes, the hollows of her cheekbones, the quiet resignation that bespoke a thousand days of tacit, unprotesting hunger.

By the staff of St. Brigid, he did not need this, any more than he had needed the furious royal summons to court in London.

Yet here she was. And his heart was moved by the look of want in her wide eyes.

“Have you eaten today?” he asked.

“Only if you count my own words.”

He raised one eyebrow. “Is that so?”

“No food has passed these lips in a fortnight.” She pretended to sway with weakness.

“That is a lie,” Aidan said mildly.

“A week?”

“Also a lie.”

“Since last night?” she said.

“That I am likely to believe. You do not need to lie to win my sympathy.”

“It’s a habit, like spitting. Sorry.”

“Where can I get you a hearty meal, colleen?”

Her eyes danced with anticipation. “Oh, there, Your Greatness.” She pointed across the way, past the ’Change, where armed guards flanked a chest of bullion. “The Nag’s Head Inn has good pies and they don’t water down their ale.”

“Done.” He strode into the middle of the road. A few market carts jostled past. A herd of laughing, filthy children charged past in pursuit of a runaway pig, and a noisome knacker’s wagon, piled high with butchered horse parts, lumbered by. When at last the way seemed clear, Aidan grabbed Pippa’s hand and hurried her across.

“Now,” he said, ducking beneath the low lintel of the doorway and drawing her inside. “Here we are.”

It took a moment for his eyes to adjust to the dimness. The tavern was nearly full despite the early hour. He took Pippa to a scarred table flanked by a pair of three-legged stools.

He called for food and drink. The alewife slumped lazily by the fire as if loath to bestir herself. In high dudgeon, Pippa marched over to her. “Did you not hear His Lordship? He desires to be served now.” Puffed up with self-importance, she pointed out his rich mantle and the tunic beneath, decked in cut crystal points. The sight of a well-turned-out patron spurred the woman to bring the ale and pasties quickly.

Pippa picked up her wooden drinking mug and drained nearly half of it, until he rapped on the bottom. “Slowly now. It won’t sit well on an empty stomach.”

“If I drink enough, my stomach won’t care.” She set down the mug and dragged her sleeve across her mouth. A certain glazed brightness came over her eyes, and he felt a welling of discomfort, for it had not been his purpose to make her stupid with drink.

“Eat something,” he urged her. She gave him a vague smile and picked up one of the pies. She ate methodically and without savor. The Sassenach were terrible cooks, Aidan thought, not for the first time.

A hulking figure filled the doorway and plunged the tavern deeper into darkness. Aidan’s hand went for his dagger; then he remembered the girl still had it.

As soon as the newcomer stepped inside, Aidan grinned and relaxed. He would need no weapon against this man.

“Come sit you down, Donal Og,” he said in Gaelic, dragging a third stool to the table.

Aidan was known far and wide as a man of prodigious size, but his cousin dwarfed him. Donal Og had massive shoulders, legs like tree trunks and a broad, prominent brow that gave him the look of a simpleton. Nothing was farther from the truth. Donal Og was brilliant, wry and unfailingly loyal to Aidan.

Pippa stopped chewing to gape at him.

“This is Donal Og,” said Aidan. “The captain of my guard.”

“Donal Og,” she repeated, her pronunciation perfect.

“It means Donal the Small,” Donal Og explained.

Her gaze measured his height. “Where?”

“I was so dubbed at birth.”

“Ah. That explains everything.” She smiled broadly. “I am honored. My name is Pippa Trueblood.”

“The honor is my own, surely,” Donal Og said with faint irony in his voice.

Aidan frowned. “I thought you said Trueheart.”

She laughed. “Silly me. Perhaps I did.” She began licking grease and crumbs from her fingers.

“Where,” Donal Og asked in Gaelic, “did you find that?”

“St. Paul’s churchyard.”

“The Sassenach will let anyone in their churches, even lunatics.” Donal Og held out a hand, and the alewife served him a mug of ale. “Is she as crazy as she looks?”

Aidan kept a bland, pleasant smile on his face so the girl would not guess what they spoke of. “Probably.”

“Are you Dutch?” she asked suddenly. “That language you’re using to discuss me—is it Dutch? Or Norse, perhaps?”

Aidan laughed. “It is Gaelic. I thought you knew. We’re Irish.”

Her eyes widened. “Irish. I’m told the Irish are wild and fierce and more papist than the pope himself.”

Donal Og chuckled. “You’re right about the wild and fierce part.”

She leaned forward with interest burning in her eyes. Aidan gamely ran a hand through his hair. “You’ll see I have no antlers, so you can lay to rest that myth. If you like, I’ll show you that I have no tail—”

“I believe you,” she said quickly.

“Don’t tell her about the blood sacrifices,” Donal Og warned.

She gasped. “Blood sacrifices?”

“Not lately,” Aidan concluded, his face deadly serious.

“Certainly not on a waning moon,” Donal Og added.

But Pippa held herself a bit more stiffly and regarded them with wariness. She seemed to be measuring the distance from table to door with an expert eye. Aidan had the impression that she was quite accustomed to making swift escapes.

The alewife, no doubt drawn by the color of their money, sidled over with more brown ale. “Did ye know we’re Irish, ma’am?” Pippa asked in a perfect imitation of Aidan’s brogue.

The alewife’s brow lifted. “Do tell!”

“I’m a nun, see,” Pippa explained, “of the Order of Saint Dorcas of the Sisters of Virtue. We never forget a favor.”

Suitably impressed, the alewife curtsied with new respect and withdrew.

“So,” Aidan said, sipping his ale and hiding his amusement at her little performance. “We are Irish and you cannot decide on a family name for yourself. How is it that you came to be a strolling player in St. Paul’s?”

Donal Og muttered in Gaelic, “Really, my lord, could we not just leave? Not only is she crazy, she’s probably crawling with vermin. I’m sure I just saw a flea on her.”

“Ah, that’s a sad tale indeed,” Pippa said. “My father was a great war hero.”

“Which war?” Aidan asked.

“Which war do you suppose, my lord?”

“The Great Rebellion?” he guessed.

She nodded vigorously, her hacked-off hair bobbing. “The very one.”

“Ah,” said Aidan. “And your father was a hero, you say?”

“You’re as giddy as she,” grumbled Donal Og, still speaking Irish.

“Indeed he was,” Pippa declared. “He saved a whole garrison from slaughter.” A faraway look pervaded her eyes like morning mist. She looked past him, out the open door, at a patch of the sky visible between the gabled roofs of London. “He loved me more than life itself, and he wept when he had to leave me. Ah, that was a bleak day for the Truebeard family.”

“Trueheart,” Aidan corrected, curiously moved. The story was as false as a strumpet’s promise, yet the yearning he heard in the girl’s voice rang true.

“Trueheart,” she agreed easily. “I never saw my father again. My mother was carried off by pirates, and I was left quite alone to fend for myself.”

“I’ve heard enough,” said Donal Og. “Let’s go.”

Aidan ignored him. He found himself fascinated by the girl, watching as she helped herself to more ale and drank greedily, as if she would never get her fill.

Something about her touched him in a deep, hidden place he had long kept closed. It was in the very heart of him, embers of warmth that he guarded like a windbreak around a herdsman’s fire. No one was allowed to share the inner life of Aidan O Donoghue. He had permitted that just once—and he had been so thoroughly doused that he had frozen himself to sentiment, to trust, to joy, to hope—to everything that made life worth living.

Now here was this strange woman, unwashed and underfed, with naught but her large soft eyes and her vivid imagination to shield her from the harshness of the world. True, she was strong and saucy as any rollicking street performer, but not too far beneath the gamine surface, he saw something that fanned at the banked embers inside him. She possessed a subtle, waiflike vulnerability that was, at least on the surface, at odds with her saucy mouth and nail-hard shell of insouciance.

And, though her hair and face and ill-fitting garments were smeared with grease and ashes, a charming, guileless appeal shone through.

“That is quite a tale of woe,” Aidan commented.

Her smile favored them both like the sun bursting through stormclouds.

“Too bad it’s a pack of lies,” Donal Og said.

“I do wish you’d speak English,” she said. “It’s bad manners to leave me out.” She glared accusingly at him. “But I suppose, if you’re going to say I’m crazy and a liar and things of that sort, it is probably best to speak Irish.”

Seeing so huge a man squirm was an interesting spectacle. Donal Og shifted to and fro, causing the stool to creak. His hamlike face flushed to the ears. “Aye, well,” he said in English, “you need not perform for Aidan and me. For us, the truth is good enough.”

“I see.” She elongated her words as the effects of the ale flowed through her. “Then I should indeed confess the truth and tell you exactly who I am.”

Diary of a Lady

It is a mother’s lot to rejoice and to grieve all at once. So it has always been, but knowing that has never eased my grief nor dimmed my joy.

In the early part of her reign, the queen gave our family a land grant in County Kerry, Munster, but until recently, we kept it in name only, content to leave Ireland to the Irish. Now, quite suddenly, we are expected to do something about it.

Today my son Richard received a royal commission. I wonder, when the queen’s advisers empowered my son to lead an army, if they ever, even for an instant, imagined him as I knew him—a laughing small boy with grass stains on his elbows and the pure sweetness of an innocent heart shining from his eyes.

Ah, to me it seems only yesterday that I held that silky, golden head to my breast and scandalized all society by sending away the wet nurse.

Now they want him to lead men into battle for lands he never asked for, a cause he never embraced.

My heart sighs, and I tell myself to cling to the blessings that are mine: a loving husband, five grown children and a shining faith in God that—only once, long ago—went dim.

—Lark de Lacey,

Countess of Wimberleigh

Two

“I can’t believe you brought her with us,” said Donal Og the next day, pacing in the walled yard of the old Priory of the Crutched Friars.

As a visiting dignitary, Aidan had been given the house and adjacent priory by Lord Lumley, a staunch Catholic and unlikely but longtime royal favorite. The residence was in Aldgate, where all men of consequence lived while in London. The huge residence, once home to humble and devout clerks, comprised a veritable village, including a busy glassworks and a large yard and stables. It was oddly situated, bordered by broad Woodroffe Lane and crooked Hart Street and within shouting distance of a grim, skeletal scaffold and gallows.

Aidan had given Pippa a room of her own, one of the monks’ cells facing a central arcade. The soldiers had strict orders to watch over her, but not to threaten or disturb her.

“I couldn’t very well leave her at the Nag’s Head.” He glanced at the closed door of her cell. “She might’ve been accosted.”

“She probably has been, probably makes her living at it.” Donal Og cut the air with an impatient gesture of his hand. “You take in strays, my lord, you always have—orphaned lambs, pups rejected by their dams, lame horses. Creatures better left—” He broke off, scowled and resumed pacing.

“To die,” Aidan finished for him.

Donal Og swung around, his expression an odd mix of humanity and cold pragmatism. “It is the very rhythm of nature for some to struggle, some to survive, some to perish. We’re Irish, man. Who knows that better than we? Neither you nor I can change the world. Nor were we meant to.”

“But isn’t that what we came to London to accomplish, cousin?” Aidan asked softly.

“We came because Queen Elizabeth summoned you,” Donal Og snapped. “And now that we’re here, she refuses to see you.” He tilted his great blond head skyward and addressed the clouds. “Why?”

“It amuses her to keep foreign dignitaries cooling their heels, waiting for an audience.”

“I think she’s insulted because you go all about town with an army of one hundred. Mayhap a little more modesty would be in order.”

Iago came out of the barracks, scratching his bare, ritually scarred chest and yawning. “Talk, talk, talk,” he said in the lilting tones of his native island. “You never shut up.”

Aidan said a perfunctory good morning to his marshal. Through an extraordinary chain of events, Iago had come ten years earlier from the West Indies of the New World. His mother was of mixed island native and African blood, his father a Spaniard.

Iago and Aidan had grown to full manhood together. Two years younger than Iago and in awe of the Caribbean man’s strength and prowess, Aidan had insisted on emulating him. Gloriously drunk one day, he had endured the ritual scarring ceremony in secret, and in a great deal of pain. To the horror of his father, Aidan now bore, like Iago, a series of V-shaped scars down the center of his chest.

“I was just saying,” Donal Og explained, “that Aidan is always taking in strays.”

Iago laughed deeply, his mahogany face shining through the morning mist. “What a fool, eh?”

Chastened, Donal Og fell silent.

“So what did he drag home this time?” Iago asked.

Pippa lay perfectly still with her eyes closed, playing a familiar game. From earliest memory, she always awoke with the certain conviction that her life had been a nightmare and, upon awakening, she would find matters the way they should be, with her mother smiling like a Madonna while her father worshipped her on bended knee and both smiled upon their beloved daughter.

With a snort of self-derision, she beat back the fantasy. There was no place in her life for dreams. She opened her eyes and looked up to see a cracked, limewashed ceiling. Timber and wattled walls. The scent of slightly stale, crushed straw. The murmur of masculine voices outside a thick timber door.

It took a few moments to remember all that had happened the day before. While she reflected on the events, she found a crock of water and a basin and cupped her hands for a drink, finally plunging in her face to wash away the last cobwebby vestiges of her fantasies.

Yesterday had started out like any other day—a few antics in St. Paul’s; then she and Mortlock and Dove would cut a purse or filch something to eat from a carter. Like London smoke borne on a breeze, they would drift aimlessly through the day, then return to the house on Maiden Lane squished between two crumbling tenements.

Pippa had the attic room all to herself. Almost. She shared it with a rather aggressively inquisitive rat she called, for no reason she could fathom, Pavlo. She also shared quarters with all the private worries and dreamlike memories and unfocused sadness she refused to confess to any other person.

Yesterday, the free-flowing course of her life had altered. For better or worse, she knew not. She felt no ties to Mort and Dove; the three of them used each other, shared what they had to, and jealously guarded the rest. If they missed her at all, it was because she had a knack for drawing a crowd. If she missed them at all—she had not decided whether or not she did—it was because they were familiar, not necessarily beloved.

Pippa knew better than to love anyone.

She had come with the Irish nobleman simply because she had nothing better to do. Perhaps fate had taken a hand in her fortune at last. She had always wanted the patronage of a rich man, but no one had ever taken notice of her. In her more fanciful moments, she thought about winning a place at court. For now, she would settle for the Celtic lord.

After all, he was magnificently handsome, obviously rich and surprisingly kind.

A girl could do far worse than that.

By the time he had brought her to this place, she had been woozy with ale. She had a vague memory of riding a large horse with the O Donoghue Mór seated in front of her and all his strange, foreign warriors tramping behind.

She made certain her shabby sack of belongings lay in a corner of the room, then dried her face. As she cleaned her teeth with the tail of her shift dipped in the water basin, she saw, wavering in the bottom of the bowl, a coat of arms.

Norman cross and hawk and arrows.

Lumley’s device. She knew it well, because she had once stolen a silver badge from him as he had passed through St. Paul’s.

She straightened up and combed her fingers through her hacked-off hair. She did not miss having long hair, but once in a while she thought about looking fashionable, like the glorious ladies who went about in barges on the Thames. In the past, when she bothered to wash her hair, it had hung in honey gold waves that glistened in the sun.

A definite liability. Men noticed glistening golden hair. And that was the last sort of attention she wanted.

She jammed on her hat—it was a slouch of brown wool that had seen better days—and wrenched open the door to greet the day.

Morning mist lay like a shroud over a rambling courtyard. Men and dogs and horses slipped in and out of view like wraiths. The fog insulated noise, and the arcade created soft, hollow echoes, so that the Irish voices of the men had an eerie intimacy.

She tucked her thumbs into her palms to ward off evil spirits—just in case.

Several yards from Pippa, three men stood talking in low tones. They made a most interesting picture—the O Donoghue with his blue mantle slung back over one shoulder, his booted foot propped on the tongue of a wagon, and his elbow braced upon his knee.

Donal Og, the rude cousin, leaned against the wagon wheel, gesticulating like a man in the grips of St. Elmo’s fire. The third man stood with his back turned, feet planted wide as if he were on the deck of a ship. He was tall—she wondered if prodigious height was a required quality of the Irish lord’s retinue—and his long, soft tunic blazed with color in hues more vivid than April flowers.

She strolled out of her chamber to find that it was one of a long line of barracks or cells hunched against an ancient wall and shaded by the arcade. She walked over to the wagon, and in her usual forthright manner, she picked up the hem of the man’s color-drenched garment and fingered the fabric.

“Now, colleen,” Aidan O Donoghue said in a warning voice.

The man in the bright cloak turned.

Pippa’s mouth dropped open. A squeak burst from her throat and she stumbled back. Her heel caught on a broken paving stone. She tripped and landed on her backside in a puddle of morning-chilled mud.

“Jesus Christ on a flaming crutch!” she said.

“Reverent, isn’t she?” Donal Og asked wryly. “Faith, but she’s a perfect little saint.”

Pippa kept staring. This was a Moor. She had heard about them in story and song, but never had she seen one. His face was remarkable, a gleaming sculpture of high cheekbones, a bony jaw, beautiful mouth, eyes the color of the stoutest ale. He had a perfect black cloud of hair, and skin the color of antique, polished leather.

“My name is Iago,” he said, stepping back and twitching the hem of his remarkable cloak out of the way of the mud.

“Pippa,” she said breathlessly. “Pippa True—True—”

Aidan stuck out his hand and pulled her to her feet. She felt his smooth, easy strength as he did so, and his touch was a wonder to her, in its way, more of a wonder than the Moor’s appearance.

Iago looked from Pippa to Aidan. “My lord, you have outdone yourself.”

She felt the mud slide down her backside and legs, pooling in the tops of her ancient boots. Last winter, she had stolen them from a corpse lying frozen in an alley.

“Will you eat or bathe first?” the O Donoghue asked, not unkindly.

Her stomach cramped, but she was well used to hunger pangs. The chill mud made her shiver. “A bath, I suppose, Your Reverence.”

Donal Og and Iago grinned at each other. “Your Reverence,” Iago said in his deep, musical voice.

Donal Og pointed his toe and bowed. “Your Reverence.”

Aidan ignored them. “A bath it is, then,” he said.

“I’ve never had one before.”

The O Donoghue looked at her for a long moment. His gaze burned over her, searing her face and form until she thought she might sizzle like a chicken on a spit.

“Why am I not surprised?” he asked.

She sang with a perfect, off-key joy. The room, adjoining the kitchen of Lumley House, was small and cramped and windowless, but the open door let in a flood of light. Aidan sat on the opposite side of the folding privy screen and put his hands over his ears, but her exuberant and bawdy song screeched through the barrier.

“At Steelyard store of wines there be

Your dulled minds to glad,

And handsome men that must not wed,

Except they leave their trade.

They oft shall seek for proper girls,

And some perhaps shall find—”

She broke off and called, “Do you like my song, Your Worship?”

“It’s grand,” he forced himself to say. “Simply grand.”

“I could sing you another if you wish,” she said eagerly.

“Ah, that would be a high delight indeed, I’m sure,” he said.

She took his patronage seriously. Too seriously.

“The bed it shook

As pleasure took

The carpet-knight for a ride…”

She belted the words out unblushingly. Aidan had never seen a mere bath have this sort of effect on anyone. How a wooden barrel half filled with lukewarm water could make a woman positively drunk with elation was beyond him.

She splashed and sang and every once in a while he could hear a scrubbing sound. He hoped she was availing herself of the harsh wood-ash soap.

Pippa’s singing had long since driven the Lumley maids into the yard to gossip. When he had told them to draw a bath, they had shaken their heads and muttered about Lord Lumley’s strange Irish guests.

But they had obeyed. Even in London, so many leagues from his kingdom in Kerry, he was still the O Donoghue Mór.

Except to Pippa. Despite her constant attempts to entertain him and seek his approval, she had no respect for his status. She paused in her song to draw breath or perhaps—God forbid—think up another verse.

“Are you quite finished?” Aidan asked.

“Finished? Are we pressed for time?”

“You’ll wind up pickled like a herring if you stew in there much longer.”

“Oh, very well.” He heard the slap of water sloshing against the sides of the barrel. “Where are my clothes?” she asked.

“In the kitchen. Iago will boil them. The maids found you a few things. I hung them on a peg—”

“Oooh.” She managed to infuse the exclamation with a wealth of wonder and yearning. “These are truly a gift from heaven.”

They were no gift, but the castoffs of a maid who had run off with a Venetian sailor the week before. He heard Pippa bumping around behind the screen. A few moments later, she emerged.

Haughty pride radiated from her small, straight figure. Aidan clamped his teeth down on his tongue to keep from laughing.

She had the skirt on backward and the buckram bodice upside down. Her damp hair stuck out in spikes like a crown of thorns. She was barefoot and cradling the leather slippers reverently in her hands.

Then she moved into the strands of sunlight streaming in through the kitchen door, and he saw her face for the first time devoid of soot and ashes.

It was like seeing the visage of a saint or an angel in one’s dreams. Never, ever, had Aidan seen such a face. No single feature was remarkable in and of itself, but taken as a whole, the effect was staggering.

She had a wide, clear brow, her eyebrows bold above misty eyes. The sweet curves of nose and chin framed a soft mouth, which she held pursed as if expecting a kiss. Her cheekbones were highlighted by pink-scrubbed skin. Aidan thought of the angel carved in the plaster over the altar of the church at Innisfallen. Somehow, that same lofty, otherworldly magic touched Pippa.

“The clothes,” she stated, “are magnificent.”

He allowed himself a controlled smile designed to preserve her fervent pride. “And so they are. Let me help you with some of the fastenings.”

“Ah, my silly lord, I’ve done them all up myself.”

“Indeed you have. But since you lack a proper lady’s maid to help you, I should take her part.”

“You’re very kind,” she said.

“Not always,” he replied, but she seemed oblivious of the warning edge in his voice. “Come here.”

She crossed the room without hesitation. He could not decide whether that was healthy or not. Should a young woman alone be so trusting of a strange man? Her trust was no gift, but a burden.

“First the bodice,” he said patiently, untying the haphazard knot she had made in the lacings. “I have never wondered why it mattered, but fashion demands that you wear it with the other end up.”

“Truly?” She stared down at the stiff garment in dismay. “It covered more of me upside down. When you turn it the other way, I spill out like loaves from a pan.”

His loins burned with the image, and he gritted his teeth. The last thing he had expected was that he might desire her. Pippa lifted her arms and held them steady while he unlaced the bodice.

It proved to be the most excruciating exercise in self-restraint he had ever endured. Somehow, the dust and ashes of her harsh life had masked an uncounted wealth of charms. He had the feeling that he was the first man to see beneath the grime and ill-fitting clothes.

As he pulled the laces through, his knuckles grazed her. The maids had provided neither shift nor corset. All that lay between Pippa’s sweet flesh and his busy hands was a chemise of wispy lawn. He could feel the heat of her, could smell the clean, beeswaxy fragrance of her just washed skin and hair.

Setting his jaw with manly restraint, he turned the bodice right side up and brought it around her. As he slowly laced the garment, watching the stiff buckram close around a narrow waist and then widen over the subtle womanly flare of her hips, pushing up her breasts, he could not banish his insistent desire.

True to her earlier observation, her bosom swelled out over the top with frank appeal, barely contained by the sheer fabric of the chemise. He could see the high, rounded shapes, the rosy shadows of the tips, and for a long, agonizing moment all he could think of was touching her there, tenderly, learning the shape and weight of her breasts, burying his face in them, drowning in the essence of her.

A roaring, like the noise of the sea, started in his ears, swishing with the quickening rhythm of his blood. He bent his head closer, closer, his tongue already anticipating the flavor of her, his lips hungry for the budded texture. His mouth hovered so close that he could feel the warmth emanating from her.

She drew in a deep, shuddering breath, and the movement reminded him to think with his brain—even the small part of it that happened to be working at the moment—not with his loins.

He was the O Donoghue Mór, an Irish chieftain who, a year before, had given up all rights to touch another woman. He had no business dallying with—of all things—a Sassenach vagabond, probably a madwoman at that.

He forced himself to stare not at the bodice, but into her eyes. And what he saw there was more dangerous than the lush curves of her body. What he saw there was not madness, but a painful eagerness.

It struck him like a slap, and he caught his breath, then hissed out air between his teeth.

He wanted to shake her. Don’t show me your yearning, he wanted to say. Don’t expect me to do anything about it.

What he said was, “I am in London on official business. I will return to Ireland as soon as I am able.”

“I’ve never been to Ireland,” she said, an ember of unbearable hope glowing in her eyes.

“These days, it is a sad country, especially for those who love it.” Sad. What a small, inadequate word to describe the horror and desolation he had seen—burned-out peel towers, scorched fields, empty villages, packs of wolves feeding off the unburied dead.

She tilted her head to one side. Unlike Aidan, she seemed perfectly comfortable with their proximity. A suspicion stung him. Perhaps it was nothing out of the ordinary for her to have a man tugging at her clothing.

The idea stirred him from his lassitude and froze the sympathy he felt for her. He made short, neat work of trussing her up, helped her slide her feet into the little shoes, then stepped back.

She ruined his hard-won indifference when she pointed a slippered toe, curtsied as if to the manner born and asked, “How do I look?”

From neck to floor, Aidan thought, like his own private dream of paradise.

But her expression disturbed him; she had the face of a cherub, filled with a trust and innocence that seemed all the more miraculous because of the hardships she must have endured living the life of a strolling player.

He studied her hair, because it was safer than looking at her face and drowning in her eyes. She lifted a hand, made a fluttery motion in the honey gold spikes. “It’s that awful?” she asked. “After I cut it all off, Mort and Dove said I could use my head to swab out wine casks or clean lamp chimneys.”

A reluctant laugh broke from him. “It is not so bad. But tell me, why is your hair cropped short? Or do I want to know?”

“Lice,” she said simply. “I had the devil of a time with them.”

He scratched his head. “Aye, well. I hope you’re no longer troubled by the little pests.”

“Not lately. Who dresses your hair, my lord? It is most extraordinary.” Brazen as an inquisitive child, she stood on tiptoe and lifted the single thread-woven braid that hung amid his black locks.

“That would be Iago. He does strange things on shipboard to avoid boredom.” Like getting me drunk and carving up my chest, Aidan thought grumpily. “I’ll ask him to do something about this mop of yours.”

He meant to reach out and tousle her hair, a meaningless, playful gesture. Instead, as if with its own mind, his palm cradled her cheek, his thumb brushing up into her sawed-off hair. The soft texture startled him.

“Will that be agreeable to you?” he heard himself ask in a whisper.

“Yes, Your Immensity.” Pulling away, she craned her neck to see over his shoulder. “There is something I need.” She hurried into the kitchen, where her old, soiled clothes lay in a heap.

Aidan frowned. He had not noticed any buttons worth keeping on her much worn garb. She snatched up the tunic and groped along one of the seams. An audible sigh of relief slipped from her. Aidan saw a flash of metal.

Probably a bauble or copper she had lifted from a passing merchant in St. Paul’s. He shrugged and went to the kitchen garden door to call for Iago.

As he turned, he saw Pippa lift the piece and press it to her mouth, closing her eyes and looking for all the world as if the bauble were more precious than gold.

From the Annals of Innisfallen

I am old enough now to forgive Aidan’s father, yet young enough to remember what a scoundrel Ronan O Donoghue was. Ah, I could roast for eternity in the fires of my unkind thoughts, but there you are, I hated the old jackass and wept no tears at his wake.

He expected more of his only son than any man could possibly give—loyalty, honor, truth, but most of all blind, stupid obedience. It was the one quality Aidan lacked. It was the one thing that could have saved the father, niggardly lout that he was, from dying.

For certain, Aidan thinks on that often, and with a great, seizing pain in his heart.

A pitiful waste if you ask me, Revelin of Innisfallen. For until he lets go of his guilt about what happened that fateful night, Aidan O Donoghue will not truly live.

—Revelin of Innisfallen

Three

“So after my father’s ship went down,” Pippa explained blithely, “his enemies assumed he had perished.” She sat very still on the stool in the kitchen garden. The smell of blooming herbs filled the spring air.

“Naturally,” Iago said in his dark honey voice. “And of course, your papa did not die at all. Even as we speak, he is attending the council of Her Majesty the queen.”

“How did you know?” Beaming, Pippa twisted around on her stool to look up at him.

Framed by the nodding boughs of the old elm tree that shaded the garden path, he regarded her with tolerant interest, a comb in his hand and a gentle compassion in his velvety black eyes. “I, too, like to invent answers to the questions that keep me awake at night,” he said.

“I invent nothing,” she snapped. “It all happened just as I described it.”

“Except that the story changes each time you encounter someone new.” He spoke with mild amusement, but no accusation. “Your father has been pirate, knight, foreign prince, soldier of fortune and ratcatcher. Oh. And did I not hear you tell O Mahoney you were sired by the pope?”

Pippa blew out a breath, and her shoulders sagged. A raven cackled raucously in the elm tree, then whirred off into the London sky. Of course she invented stories about who she was and where she had come from. To face the truth was unthinkable. And impossible.

Iago’s touch was soothing as he combed through her matted hair. He tilted her chin up and stared at her face-on for a long moment, intent as a sculptor. She stared back, rapt as a dreamer. What a remarkable person he was, with his lovely ebony skin and bell-toned voice, the fierce, inborn pride he wore like a mantle of silk.

He closed one eye; then he began to snip with his little crane-handled scissors, the very ones she had been tempted to steal from a side table in the kitchen.

As Iago worked, he said, “You tell the tales so well, pequeña, but they are just that—tales. I know this because I used to do the same. Used to lie awake at night trying to put together the face of my mother from fragments of memory. She became every good thing I knew about a mother, and before long she was more real to me than an actual woman. Only bigger. Better. Sweeter, kinder.”

“Yes,” she whispered past a sudden, unwelcome thickness in her throat. “Yes, I understand.”

He twisted a few curls into a soft fringe upon her brow. The breeze sifted lightly through them. “If you were an Englishman, you would be the very rage of fashion. They call these lovelocks. They look better on you.” He winked. “A dream mother. It was something I needed at a very dark time of my life.”

“Tell me about the dark time,” she said, fascinated by the deftness of his hands and the way they were so brown on one side, while the palms were sensitive and pale.

“Slavery,” he said. “Being made to work until I fell on my face from exhaustion, and then being beaten until I dragged myself up to work some more. You have a dream mother, too, eh?”

She closed her eyes. A lovely face smiled at her. She had spent a thousand nights and more painting her parents in her mind until they were perfect. Beautiful. All wise. Flawless, save for one minor detail. They had somehow managed to misplace their daughter.

“I have a dream mother,” she confessed. “A father, too. The stories might change, but that does not.” She opened her eyes to find him studying her critically again. “What about the O Donoghue?” she asked, pretending only idle curiosity.

“His father is dead, which is why Aidan is the lord. His mother is dead also, but his—” He cut himself off. “I have said too much already.”

“Why are you so loyal to the O Donoghue?”

“He gave me my freedom.”

“How was it his to give in the first place?”

Iago grinned, his face blossoming like an exotic flower. “It was not. I was put on a ship for transport from San Juan—that is on an island far across the Ocean Sea—to England. I was to be a gift for a great noblewoman. My master wished to impress her.”

“A gift?” Pippa was hard-pressed to sit still on her stool. “You mean like a drinking cup or a salt cellar or a pet ermine?”

“You have a blunt way of putting it, but yes. The ship wrecked off the coast of Ireland. I swam straightaway from my master even as he begged me to save him.”

Pippa sat forward, amazed. “Did he die?”

Iago nodded. “Drowned. I watched him. Does that shock you?”

“Yes! Was the water very cold?”

His chest-deep chuckle filled the air. “Close to freezing. I dragged myself to an island—I later found out it is called Skellig Michael—and there I met a pilgrim in sackcloth and ashes, climbing the great stairs to the shrine.”

“The O Donoghue Mór in sackcloth and ashes?” In Pippa’s mind, Aidan would always be swathed in flashing jewel tones, his jet hair gleaming in the sun; he was no drab pilgrim, but a prince from a fairy story.

“He was not the O Donoghue Mór then. He helped me get dry and warm, and he became my first and only true friend.” Black fury shadowed Iago’s eyes. “When Aidan’s father saw me, he declared himself my master, tried to make me a slave again. And Aidan let him.”

Pippa clutched the sides of the stool. “The jackdog! The bootlicker, the skainsmate—”

“It was a ruse. He claimed me on the grounds that he had found me. His father agreed, thinking it would enhance Aidan’s station to be the first Irishman to own a black slave.”

“The scullywarden!” she persisted. “The horse’s a—”

“And then he set me free,” Iago said, laughing at her. “He had a priest called Revelin draw up a paper. That day Aidan promised to help me return to my home when we were both grown. In fact, he promised to come with me across the Ocean Sea.”

“Why would you want to go back to a land where you were a slave? And why would Aidan want to go with you?”

“Because I love the islands, and I no longer have a master. There was a girl called Serafina….” His voice trailed off, and he shook his head as if to cast away the thought. “Aidan wanted to come because he loves Ireland too much to stay.” Iago fussed with more curls that tickled the nape of her neck.

“If he loves Ireland, why would he want to leave it?”

“When you come to know him better, you will understand. Have you ever been forced to watch a loved one die?”

She swallowed and nodded starkly, thinking of Mab. “I never felt so helpless in all my life.”

“So it is with Aidan and Ireland,” said Iago.

“Why is he here, in London?”

“Because the queen summoned him. Officially, he is here to sign treaties of surrender and regrant. He is styled Lord of Castleross. Unofficially, she is curious, I think, about Ross Castle. She wants to know why, after her interdict forbidding the construction of fortresses, it was completed.”

The idea that her patron had the power to decide the fate of nations was almost too large for Pippa to grasp. “Is she very angry with him?” It even felt odd referring to Queen Elizabeth as “she,” for Her Majesty had always been, to Pippa and others like her, a remote idea, more of an institution like a cathedral than a flesh-and-blood woman.

“She has kept him waiting here for a fortnight.” Iago lifted her from the stool to the ground. “You look as pretty as an okasa blossom.”

She touched her hair. Its shape felt different—softer, balanced, light as the breeze. She would have to go out to Hart Street Well and look at her reflection.

“You said when you met Aidan, he was not the O Donoghue Mór,” she said, thinking that the queen must enjoy having the power to summon handsome men to her side.

“His father, Ronan, was. Aidan became Lord Castleross after Ronan died.”

“And how did his father die?”

Iago went to the half door of the kitchen and held the lower part open. “Ask Aidan. It is not my place to say.”

“Iago said you killed your father.”

Aidan shot to his feet as if Pippa had touched a brand to his backside. “He said what?”

Hiding her apprehension, she strolled into the great hall of Lumley House and moved through gloomy evening shadows on the flagged floor. An ominous rumbling of thunder sounded in the distance. Aidan’s fists were clenched, his face stark and taut. Instinct told her to flee, but she forced herself to stay.

“You heard me, my lord. If you’re going to keep me, I want to make sure. Is it true? Did you kill your father?”

He grabbed an iron poker. A single Gaelic word burst from him as he stabbed at the fat log smoldering in the grate.

Pippa took a deep breath for courage. “It was Iago who—”

“Iago said nothing of the sort.”

She emerged from the shadows and joined him by the hearth, praying he would deny her suggestion. “Did you, my lord?” she whispered.

He moved so swiftly, it took her breath away. One moment the iron poker clattered to the floor; the next he had his great hands clamped around her shoulders, her back against a stone pillar and his furious face pushed close to hers. Though she still stood cloaked in shadow, she could see the flames from the hearth fire reflected in his eyes.

“Yes, damn your meddling self. I killed my father.”

“What?” She trembled in his grip.

Aidan thrust away from her, turning back to face the fire. “Isn’t that what you expected to hear?” He clenched his eyes shut and pinched the bridge of his nose. Sharp fragments of that last, explosive argument came back to slice fresh wounds into his soul.

He spun around to face Pippa, intending to carry her bodily out of the hall, out of Lumley House, out of his life. She stepped from the gloom and into the light. Aidan stopped dead in his tracks.

“What in God’s name did Iago do to you?” he asked. As if to echo his words, thunder muttered outside the hall.

Her hand wavered a little as she brought it up to touch her hair, which now curled softly around her glowing face. “The best he could?” she attempted. Then she dropped her air of trembling uncertainty. “You are trying to change the subject. Are you or are you not a father-murderer?”

He planted his hands on his hips. “That depends on whom you ask.”

She mimicked his aggressive stance, looking for all the world like a fierce pixie. “I’m asking you.”

“And I’ve answered you.”

“But it was the wrong answer,” she said, so vehemently that he expected her to stomp her foot. Something—the washing, the grooming—had made her glow as if a host of fairies had showered her with a magical mist. “I demand an explanation.”

“I feel no need to explain myself to a stranger,” he said, dismayed by the intensity of his attraction to her.

“We are not strangers, Your Loftiness,” she said with heavy irony. “Wasn’t it just this morning that you undressed me and then dressed me like the most intimate of handmaids?”

He winced at the reminder. Beneath her elfin daintiness lay a soft, womanly body that he craved with a power that was both undeniable and inappropriate. Shed of her beggar’s garb, she had become the sort of woman for whom men swore to win honors, slay dragons, cheerfully lay down their lives. And he was in no position to do any of those things.

“Some would say,” he admitted darkly, “that the death of Ronan O Donoghue was an accident.” From the corner of his eye, he saw a flicker of lightning through the mullioned windows on the east side of the hall.

“What do you say?” Pippa asked.

“I say it is none of your affair. And if you persist in talking about it, I might have to do something permanent to you.”

She sniffed, clearly recognizing the idleness of his threat. He was not accustomed to females who were unafraid of him. “If I had a father, I’d cherish him.”

“You do have a father. The war hero, remember?”

She blinked. “Oh. Him. Yes, of course.”

Aidan slammed a fist on the stone mantel and regarded the Lumley shield hanging above as if it were a higher authority. “What am I going to do with you?” The wind hurled gusts against the windows, and he swung around to glower at her.

“‘Do’ with me?” She glanced back over her shoulder at the door. He didn’t blame her for not wanting to be alone with him. She wouldn’t be the first.

“You can’t stay here forever,” he stated. “I didn’t ask to be your protector.” The twist of guilt in his gut startled him. He was not used to making cruel statements to defenseless women.

She did not look surprised. Instead, she dropped one shoulder and regarded him warily. She resembled a dog so used to being kicked that it came as a surprise when it was not kicked.

Her rounded chin came up. “I never asked to stay forever. I can go back to Dove and Mortlock. We have plans to gain the patronage of…of the Holy Roman Emperor.”

He remembered her disreputable companions from St. Paul’s—the portly and greasy Dove and the cadaverous Mortlock. “They must be mad with worry over you.”

“Those two?” She snorted and idly picked up the iron poker, stabbing at the log in the hearth. Sparks flew upward on a sweep of air, then disappeared. “They only worry about losing me because they need me to cry up a crowd. Their specialty is cutting purses.”

“I won’t let you go back to them,” Aidan heard himself say. “I’ll find you a—” he thought for a moment “—a situation with a gentlewoman—”

That made her snort again, this time with bitter laughter. “Oh, for that I should be well and truly suited.” She slammed the poker back into its stand. “It has long been my aim in life to empty some lady’s slops and pour wine for her.” The hem of her skirts twitched in agitation as she pantomimed the menial work.

“It’s a damned sight better than wandering the streets.” Irritated, he walked to the table and sloshed wine into a cup. The lightning flashed again, stark and cold in the April night.

“Oh, do tell, my lord.” She stalked across the room, slapped her palms on the table, leaned over and glared into his face. “Listen. I am an entertainer. I am good at it.”

So he had noticed. She could mimic any accent, highborn or low, copy any movement with fluid grace, change character from one moment to the next like an actor trying on different masks.

“I didn’t ask you to drag me out of St. Paul’s and into your life,” she stated.

“I don’t remember any objections from you when I saved you from having your ears nailed to the stocks.” He tasted the wine, a sweet sack favored by the English nobility. He missed his nightly draft of poteen. Pippa was enough to make him crave two drafts of the powerful liquor.

“I was hungry. But that doesn’t mean I’ve surrendered my life to you. I can get another position in a nobleman’s household just like that.” She snapped her fingers.

She was so close, he could see the dimple that winked in her left cheek. She smelled of soap and sun-dried laundry, and now that her hair was fixed, it shone like spun gold in the glow from the hearth.

He took another sip of wine. Then, very gently, he set down the cup and reached across to touch a wispy curl that drifted across her cheek. “How can it be enough to simply survive?” he asked softly. “Do you never dream of doing more than that?”

“Damn you,” she said, echoing his words to her. She shoved away from the table and turned her back on him. There was a heartbreaking pride in the stiff way she held herself, the set of her shoulders and the haughty tilt of her head. “Goodbye, Your Worship. Thank you for our brief association. We shan’t be seeing each other again.”

“Pippa, wait—”

In a sweep of skirts and injured dignity, she strode out of the hall, disappearing into the gloom of the cloister that bordered the herbiary. Aidan could not explain it, but the sight of her walking away from him caused a painful squeeze of guilt and regret in his chest.

He swore under his breath and finished his wine, then paced the room. He had more pressing matters to ponder than the fate of a saucy street performer. Clan wars and English aggression were tearing his district apart. The settlement he had negotiated last year was shaky at best. A sad matter, that, since he had paid such a dear price for the settlement. He had bought peace at the cost of his heart.

The thought caused his mind to jolt back to Pippa. The ungrateful little female. Let her storm off to her chamber and sulk until she came to her senses.

It occurred to him then that she was the sort not to sulk, but to act. She had survived—and thrived—by doing just that.

A jagged spear of lightning split the sky just as a terrible thought occurred to him. Hurling the pewter wine cup to the floor, he dashed out of the house and into the cloister of Crutched Friars, running down the arcade to her door, jerking it open.

Empty. He passed through the refectory and emerged onto the street. He had been right. He saw Pippa in the distance, hurrying down the broad, tree-lined road leading to Woodroffe Lane and the eerie, lawless area around Tower Hill. A gathering wind stirred the bobbing heads of chestnut trees. Clouds rolled and tumbled, blackening the sky, and when he breathed in, he caught the heavy taste and scent of rain and the faint, sizzling tang of close lightning.

She walked faster still, half running.