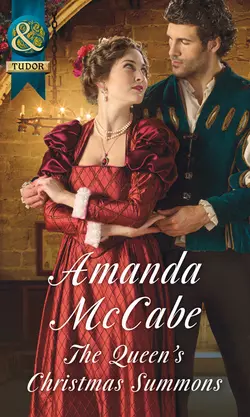

The Queen′s Christmas Summons

The Queen's Christmas Summons

Amanda McCabe

‘Royal courts are glittering places. But there can be many dangers there.’The words of Juan, the shipwrecked Spanish sailor who Lady Alys Drury nursed back to health, echo in her mind as she puts on another courtly smile.Then Alys locks eyes with a handsome man amid the splendour of Queen Elizabeth’s Christmas court—Juan is posing as courtier John Huntley! Alys is hurt at Juan’s deception until she learns he’s an undercover spy for the crown… Even amid the murky machinations of the court, can true love still conquer all?

“Royal courts are glittering places. But there can be many dangers there.”

The words of Juan, the shipwrecked Spanish sailor Lady Alys Drury nursed back to health, echo in her mind as she puts on another courtly smile.

Then Alys locks eyes with a handsome man amid the splendor of Queen Elizabeth’s Christmas court—Juan is posing as courtier John Huntley! Alys is hurt at Juan’s deception until she learns he’s an undercover spy for the crown... Amid the murky machinations of the court, can true love still conquer all?

Praise for Amanda McCabe (#u313f38b3-8dca-5081-a183-163efcbb9c2f)

‘McCabe sweeps readers into the world of the Elizabethan theatre, delighting us with a lively tale and artfully drawing on the era’s backdrop of bawdy plays, wild actors and thrilling adventure.’

—RT Book Reviews on The Taming of the Rogue

‘Including a darling little girl, meddling relatives and a bit of suspense, McCabe’s story charms readers.’

—RT Book Reviews on Running from Scandal

‘McCabe highlights an unusual and fascinating piece of history whilst never losing sight of the romance or adventure.’

—RT Book Reviews on The Demure Miss Manning

Alys put on her courtly smile, prepared to meet another of Ellen’s peacock friends—and the smile froze before it could form.

It had not been an illusion, a fleeting trick of her tired mind. It was him—Juan. Right there before her when she had been so sure she would never see him again—could never see him again. She shivered and fell back a step, suddenly feeling so very cold.

He did not quite look like her Juan, bearded and ragged from the sea. He was just as tall, but his shoulders were broader, and he wore no beard to hide the elegant angles of his sculpted face, his high cheekbones and sharp jawline, his sensual lips. He wore courtly clothes of purple velvet trimmed with silver, a high, narrow ruff at his throat. But his eyes—those brilliant summer-green eyes she had once so cherished—widened when his glance fell on her.

The Queen’s Christmas Summons

Amanda McCabe

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

AMANDA MCCABE wrote her first romance at the age of sixteen—a vast epic, starring all her friends as the characters, written secretly during algebra class. She’s never since used algebra, but her books have been nominated for many awards, including the RITA®, Romantic Times Reviewers’ Choice Award, the Booksellers’ Best, the National Readers’ Choice Award, and the Holt Medallion. She lives in Oklahoma with her husband, one dog and one cat.

Books by Amanda McCabe

Mills & Boon Historical Romance

and Mills & Boon Historical Undone! eBooks

Bancrofts of Barton Park

The Runaway Countess

Running from Scandal

Running into Temptation (Undone!)

Linked by Character

A Notorious WomanA Sinful AllianceHigh Seas StowawayShipwrecked and Seduced (Undone!)

Stand-Alone Novels

Betrayed by His Kiss

The Demure Miss Manning

The Queen’s Christmas Summons

More Mills & Boon Historical Undone! eBooks by Amanda McCabe

To Court, Capture and Conquer

Girl in the Beaded Mask

Unlacing the Lady in Waiting

One Wicked Christmas

An Improper Duchess

A Very Tudor Christmas

Visit the Author Profile page

at millsandboon.co.uk (http://millsandboon.co.uk) for more titles.

For Kyle, for three lovely years—so far

Contents

Cover (#u93b4dabe-9cf8-580b-a5b8-e205eac22a1d)

Back Cover Text (#ucd9c7e3a-3cd9-5c02-b54a-6ec73f7eaed2)

Praise (#ud93f3892-b8e5-5f25-ba5c-c8441e831e99)

Introduction (#ueca87518-415c-547d-aad6-174e6a9453ce)

Title Page (#u681f252c-a0e6-59af-9613-e7e3d8a6b624)

About the Author (#uddf594b6-1fb5-522d-921c-ebc275fb3d17)

Dedication (#u5f910b1a-2027-545b-b12f-b046ff4623ff)

Prologue (#ucc470f43-25c5-5191-b50d-43d336378dfd)

Chapter One (#u03cf5e8c-a8d3-5dab-bc2f-ee24d80ec7ab)

Chapter Two (#u8e9145bc-ec3c-5ad4-a568-dbc588e000c0)

Chapter Three (#uc62f17a9-3f0d-5960-86d2-aa57482a30cd)

Chapter Four (#u601d05ee-07ba-50c7-bb7a-772a78160fd7)

Chapter Five (#u9262ed7a-aa05-5da8-b676-e02075a2ee62)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#u313f38b3-8dca-5081-a183-163efcbb9c2f)

Richmond Palace—1576

‘You must stay right here, Alys, and not move. Do you understand?’

Lady Alys Drury stared up at her father. Usually, around her, he was always smiling, always gentle, but today he looked most stern. In fact, she did not understand. In all her eight years, her father had never seemed so grave. The man who was always laughing and boisterous, ready to sweep her up in his arms and twirl her around, could not be seen. Ever since they journeyed here, to this strange place, a royal palace, her parents had been silent.

After long days on a boat and more hours on bumpy horseback, riding pillion with her mother, they had arrived here. Alys wasn’t sure what was happening, but she knew she did not like this place, with its soaring towers and many windows, which seemed to conceal hundreds of eyes looking down at her.

‘Yes, Papa, I understand,’ she answered. ‘Will we be able to go home soon?’

He gave her a strained smile. ‘God willing, my little butterfly.’ He quickly kissed her brow and turned to hurry away up a flight of stone steps. He vanished through a doorway, guarded by men in green velvet embroidered with sparkling gold and bearing swords. Alys was left alone in the sunny, strange garden.

She turned in a slow circle, taking in her fantastical surroundings. It was like something in the fairy stories her nursemaid liked to tell, with tall hedge walls surrounding secret outdoor chambers and strictly square beds of flowers and herbs.

And the garden was not the only strange thing about the day. Alys’s new gown, a stiff creation of tawny-and-black satin, rustled around her every time she moved and the halo-shaped headdress on her long, dark hair pinched.

She kicked at the gravelled pathway with her new black-leather shoe. She wished so much she was at home, where she could run free, and where her parents did not speak in angry whispers and worried murmurs.

She tipped back her head to watch as a flock of birds soared into the cloudy sky. It was a warm day, if overcast and grey, and if she was at home she could climb trees or run along the cliffs. How she missed all that.

A burst of laughter caught her attention and she whirled around to see a group of boys a bit older than herself running across a meadow just beyond the formal knot garden. They wore just shirts and breeches, and kicked a large brown-leather ball between them.

Alys longed to move closer, to see what game they played. It didn’t look like any she had seen before. She glanced back at the doorway where her father vanished, but he hadn’t returned. Surely she could be gone for just a moment?

She lifted the hem of her skirt and crept nearer to the game, watching as the boys kicked it between themselves. As an only child, with no brothers to play with, the games of other children fascinated her.

One of the boys was taller than the others, with overly long dark hair flopping across his brow as he ran. He moved more easily, more gracefully than the boys around him. Alys was so fascinated by him that she didn’t see the ball flying towards her. It hit her hard on the brow, knocking her new headdress askew and pushing her back. For an instant, there was only cold shock, then a rush of pain. Tears sprang to her eyes as she pressed her hand to her throbbing head.

‘Watch where you’re going, then!’ one of the boys shouted. He was a thin child, freckled, not at all like the tall one, and he pushed her as he snatched back the ball. ‘Stupid girls, they have no place here. Go back to your needlework!’

Alys struggled not to cry, both at the pain in her brow and at his cruel words. ‘I am not a stupid girl! You—you hedgepig.’

‘What did you call me, wench?’ The boy took a menacing step towards her.

‘Enough!’ The tall boy stepped forward to pull her would-be attacker back. He shoved the mean boy away and turned to Alys with a gentle smile. She noticed his eyes were green, an extraordinary pale green sea-colour she had never seen before. ‘You are the one at fault here, George. Do not be ungallant. Apologise to the lady.’

‘Lady?’ George sneered. ‘She is obviously no more a lady than you are a true gentleman, Huntley. With your drunken father...’

The tall boy grew obviously angry at those words, a red flush spreading on his high, sharp cheekbones. His hands curled into fists—and then he stepped back, his hand loosening, a smile touching his lips. Alys forgot her pain as she watched him in fascination.

‘It seems you must be the one who took a blow to the head, George,’ Huntley said. ‘You are clearly out of your wits. Now, apologise.’

‘Nay, I shall not...’ George gasped as Huntley suddenly reached out, quick as a snake striking, and seized his arm. It looked like a most effortless movement, but George turned pale. ‘Forgive me, my lady.’

‘That is better.’ Huntley pushed the bully away and turned away from him without another glance. He came to Alys and held out his hand.

He smiled gently and Alys was dazzled by it.

‘My lady,’ he said. ‘Let me assist you to return to the palace.’

‘Th...thank you,’ she whispered. She took his arm, just like a grown-up lady, and walked with him back to the steps.

‘Are you badly hurt?’ he asked softly.

Alys suddenly realised her head did still hurt. She had quite forgotten everything else when she saw him. It was most strange. ‘Just a bit of a headache. My mother will have herbs for it in her medicine chest.’

‘Where is your mother? I’ll take you to her.’

Alys shook her head. Her mother had stayed at the inn, pleading illness, so her father had taken Alys away with him. She didn’t know how to get back to the inn at all. ‘She is in the village. My father...’

‘Has he come here to see the Queen?’

The Queen? No wonder this place was so grand, if it was a queen’s home. But why was her father to see her? She felt more confused than ever. ‘I was not supposed to move from the steps until he returns. I’ll be in such trouble!’

‘Nay, I will stay with you, my lady, and explain to your father when he returns.’

Alys studied him doubtfully. ‘Surely you have more important things you must be doing.’

His smile widened. ‘Nothing more important, I promise you.’

He led her back to the top of the stone steps where her father left her and helped her sit down. He sat beside her and gently examined her forehead. ‘It is rather darkening, I’m afraid. I hope your mother has an herb to cure bruising.’

‘Oh, no!’ She clapped her hand over her brow, feeling herself blush hotly that he should see her like that. ‘She does have ointments for such, but it must be hideous.’

He smiled, his lovely green eyes crinkling at the corners. ‘It is a badge of honour from battle. You are fortunate to have a caring mother.’

‘Does your mother not have medicines for you when you’re ill?’ Alys asked, thinking of all her mother’s potions and creams that soothed fevers and pains, just as her own cool hands did when Alys was fretful.

He looked away. ‘My mother died long ago.’

‘Oh! I am sorry,’ she cried, feeling such pain for him not to have a mother. ‘But have you a father? Siblings?’ She remembered the vile George’s taunt, of Huntley’s ‘drunken father’, and wished she had not said anything.

‘I seldom see my father. My godfather arranges for my education. No siblings. What of you, my lady?’

‘I have no siblings, either. I wish I did. It gets very quiet at home sometimes.’

‘Is that why you came to look at our game?’

‘Aye. It sounded very merry. I wondered what it was.’

‘Have you never played at football?’

‘I’ve never even heard of it. I have seen tennis, but few other ball games.’

‘It’s the most wonderful game! You start like this...’ He leaped up to demonstrate, running back and forth as he told her of scoring and penalties. He threw up his arms in imagined triumph as he explained how the game was won.

Caught up in his enthusiasm, Alys clapped her hands and laughed. He gave her a bow.

‘How marvellous,’ she said. ‘I do wish I had someone at home to play such games with like that.’

‘What do you play at home, then?’ he asked. He tossed her the ball. She instinctively caught it and threw it back.

‘I read, mostly, and walk. I have a doll and I tell her things sometimes. There isn’t much I can do alone, I’m afraid.’

‘I quite understand. Before I went to school, I was often alone myself.’ His expression looked wistful, as if his thoughts were far away, and Alys found herself intensely curious about him, who he was and what he did.

‘Alys! What are you doing?’ she heard her father shout.

She spun around and saw him hurrying towards her, frowning fearsomely. ‘Papa! I am sorry, I just...’

‘I fear your daughter took a bit of a fall here, my lord,’ her new friend said, stepping close to her side. She felt safer with him there. ‘I saw her, and I...’

‘And he came to help me, most gallantly,’ Alys said.

Her father’s frown softened. ‘Did you indeed? Good lad. I owe you many thanks.’

‘Your daughter is a fine lady indeed, my lord,’ Huntley said. ‘I am glad to have met her today.’

Her father softened even more and reached into his purse to offer the boy a coin. Huntley shook his head and her father said, ‘My thanks again. We bid you good day, lad, and good fortune to you.’ He swung Alys up into his arms and walked away from the grand palace.

Alys glanced back over her shoulder for one last glimpse of her friend. He smiled at her and waved, and she waved back until he was out of sight. She thought surely she would never forget him, her new friend and gallant rescuer.

Chapter One (#u313f38b3-8dca-5081-a183-163efcbb9c2f)

Dunboyton Castle, Galway, Ireland—1578

‘And this one, niña querida? What is this one? What does it do?’

Lady Alys Drury, aged ten and a half and now expected to learn to run a household, leaned close to the tray her mother held out and inhaled deeply, closing her eyes. Despite the icy wind that beat at the stout stone walls of Dunboyton, she could smell green sunshine from the dried herbs. Flowers and trees and clover, all the things she loved about summer.

But not as much as she loved her mother and their days here in the stillroom, the long, narrow chamber hung with bundles of herbs and with bottles of oils and pots of balms lining the shelves. It was always warm there, always bright and full of wonderful smells. A sanctuary in the constant rush and noise of the castle corridors, which were the realm of her father and his men.

Here in the stillroom, it was just Alys and her mother. For all her ten years, for as long as she could remember, this had been her favourite place. She could imagine nowhere finer.

She inhaled again, pushing a loose lock of her brown hair back from her brow. She caught a hint of something else beneath the green—a bit of sweet wine, mayhap?

‘Querida?’ her mother urged.

Alys opened her eyes and glanced up into her mother’s face. Elena Drury’s dark eyes crinkled at the edges as she smiled. She wore black and white, starkly tailored and elegant, as she often did, to remind her of the fashions of her Spanish homeland, but there was nothing dark or dour about her merry smile.

‘Is it—is it lemon balm, mi madre?’ Alys said.

‘Very good, Alys!’ her mother said, clapping her hands. ‘Sí, it is melissa officinalis. An excellent aid for melancholy, when the grey winter has gone on too long.’

Alys giggled. ‘But it is always grey here, Madre!’ Every day seemed grey, not like the sunlit memories of her one day at a royal court. Sometimes she was sure that had all been a dream, especially the handsome boy she had seen that day. This was the only reality now.

Her mother laughed, too, and carefully stirred the dried lemon balm into a boiling pot of water. ‘Only here in Galway. In some places, it is warm and sunny all the time.’

‘Such as where you were born?’ Alys had heard the tales many times, but she always longed to hear them again. The white walls of Granada, where her mother was born, the red-tiled roofs baking in the sun, the sound of guitar music and singing on the warm breeze.

Elena smiled sadly. ‘Such as where I was born, in Granada. There is no place like it, querida.’

Alys glanced out the narrow window of the stillroom. The rain had turned to icy sleet, which hit the old glass like the patter of needles as the wind howled out its mournful cries. ‘Why would your mother leave such a place?’

‘Because she loved my father and followed him to England when his work brought him here. It was her duty to be by his side.’

‘As it is yours to be with Father?’

‘Of course. A wife must always be a good helpmeet to her husband. It is her first duty in life.’

‘And because you love him.’ This was another tale she had heard often. The tale of how her father had seen her mother, the most beautiful woman in the world, at a banquet and would marry no other, even against the wishes of his family. Alys knew her parents had not regretted choosing each other; she had often caught them secretly kissing, seen them laughing together, their heads bent close.

Her mother laughed and tucked Alys’s wayward lock of hair back into her little cap. ‘And that, too, though you are much too young to think of such things yet.’

‘Will I have a husband as kind as Father?’

Her mother’s smile faded and she bent her head over the tea she stirred. Her veil fell forward to hide her expression. ‘There are few men like your father, I fear, and you are only ten. You needn’t think about it for so long. Marriages are made for many reasons—family security, wealth, land, even affection sometimes. But I promise, no matter who you marry, he will be a good man, a strong one. You will not be here in Ireland for ever.’

Alys had heard such things so often. Ireland was not really their home; her father only did his duty here to the Queen for a time. One day they would have a real home, in England, and she would have a place at court. Perhaps she would even serve the Queen herself, and marry a man handsome and strong. But she could conceive of little beyond Dunboyton’s walls, the cliffs and wild sea that surrounded them. There had only been that one small glimpse of the royal court, the boys playing at football, and then it was gone.

‘Now, querida, what is this one?’ her mother asked as she held out a small bottle.

Alys smelled a green sharpness, something like citrus beneath. ‘Marjoram!’

‘Exactly. To spice your father’s wine tonight and help with his stomach troubles.’

‘Is Father ill?’

Elena’s smile flickered. ‘Not at all. Too many rich sauces with his meat, I have warned him over and over. Ah, well. Here, niña, I have something for you.’

Alys jumped up on her stool, clapping her hands in delight. ‘A present, Madre?’

‘Sí, a rare one.’ She reached into one of her carved boxes, all of them darkened with age and infused with the scent of all the herbs they had held over the years. Her mother removed a tiny muslin-wrapped bundle. She laid it carefully on Alys’s trembling palm.

Alys unwrapped it to find a few tiny, perfect curls of bright yellow candied lemon peels. The yellow was sun-brilliant, sprinkled with sugar like snowflakes. ‘Candied lemon!’

Her favourite treat. It tasted just like the sunshine Alys always longed for. She couldn’t resist; she popped a piece on to her tongue and let it melt into sticky sweetness.

Her mother laughed. ‘My darling daughter, always so impetuous! My brother could only send a few things from Spain this time.’ She gave a sigh as she poured off the new tisane of lemon balm. ‘The weather has kept so many of the ships away.’

Alys glanced at the icy window again. It was true, there had been few ships in port of late. Usually they saw many arrivals from Spain and the Low Countries, bringing rare luxuries and even rarer news of home to her mother.

There was the sudden heavy tread of boots up the winding stairs to the stillroom. The door opened and Alys’s father, Sir William Drury, stood there. He was a tall man, broad of shoulder, with light brown hair trimmed short in the new fashion and a short beard. But of late, there were more flecks of grey in his beard than usual, more of a stoop to his shoulders. Alys remembered what her mother had said about his stomach troubles.

But he always smiled when he saw them, as he did now, a wide, bright grin.

‘Father!’ Alys cried happily and jumped up to run to him. He hugged her close, as he always did, but she sensed that he was somehow distant from her, distracted.

Alys drew back and peered up at him. She had to look far, for he was so very much taller than she. He did smile, but his eyes looked sad. He held something in his hand, half-hidden behind his back.

‘William,’ she heard her mother say. There was a soft rustle of silk, the touch of her mother’s hand on her shoulder. ‘The letter...’

‘Aye, Elena,’ he answered, his voice tired. ‘’Tis from London.’

‘Alys,’ her mother said gently. ‘Why don’t you go to the kitchen and see if our dinner will soon be ready? Give this to the cooks for the stew.’

She pressed a sachet of dried parsley and rosemary into Alys’s hand and gently urged her through the door.

Bewildered, Alys glanced back before the door could close behind her. Her father went to the window, staring out at the rain beyond with his back to her, his hand clasped before him. Her mother went to him, leaning against his shoulder. Alys dared to hold the door open a mere inch, lingering so she could find out what was happening. Otherwise they would never tell her at all.

‘There is still no place for you at court?’ Alys heard her mother say. Elena’s voice was still soft, kind, but it sounded as if she might start to cry.

‘Nay, not yet, or so my uncle writes. I am needed here for a time longer, considering the uprisings have just been put down. Here! In this godforsaken place where I can do nothing!’ His fist came down on the table with a sudden crash, rattling the bottles.

‘Because of me,’ her mother whispered. ‘Madre de Dios, but if not for me, for us, you would have your rightful place.’

‘Elena, you and Alys are everything to me. You would be a grace to the royal court, to anywhere you chose to be. They are fools they cannot see that.’

‘Because I am a Lorca-Ramirez. I should not have married you, mi corazón. I have brought you nothing. If you had a proper English wife—if I was gone...’

‘Nay, Elena, you must never say that. You are all to me. I would rather be here at the end of the world with you and Alys than be a king in a London palace.’

Alys peeked carefully through the crack in the door and watched as her father took her mother tightly into his arms as she sobbed on his shoulder. Her father’s expression when he thought his wife could not see was fierce, furious.

Alys tiptoed down the stillroom stairs, careful to make no sound. She felt somehow cold and fearful. Her father was almost never angry, yet there was something about that moment, the look on his face, the sadness that hung so heavy about her mother, that made her want to run away.

Yet she also wanted to run to her parents, to wrap her arms around them and banish anything that would dare hurt them.

She made her way to the bustling kitchen to leave the herbs with the cook, hurrying around the soldiers who cleaned their swords by the fire, the maids who scurried around with pots and bowls. London. It was there that lurked whatever had angered her father. She knew where London was, of course, far away over the sea in England. It was home, or so her father sometimes said, but she couldn’t quite fathom it.

When he showed her drawings of London, pointing out churches and bridges and palaces, she was amazed by the thought of so many people in such grand dwellings. The largest place she knew was Galway City. When she went to market there with her mother, Father said London was like twenty Galways.

London was also where Queen Elizabeth lived. The Queen, who was so grand and glittering and beautiful, who held all of England safe in her jewelled hand. Was it the Queen who angered him now? Who slighted her mother?

Her fists clenched in anger at the thought of it as Alys stomped across the kitchen. How dared the Queen, how dared anyone, do such a thing to her parents? It was not fair. She didn’t care where she lived, whether Galway or London, but she did care if her father was denied his true place.

‘How now, Lady Alys, and what has you in such a temper?’ one of the cooks called out. ‘Have the fairies stolen away your sugar and left salt instead?’

Alys had to laugh at the teasing. ‘Nay, I merely came to give you some of my mother’s herbs. ʼTis the cold day has me in a mood, I think.’

‘It’s never cold down here with all these fires. Here, I need a spot of mint from the garden and I think a hardy bunch still has some green near the wall. Will you fetch it for me? Some fresh air might do you some good, my lady.’

Alys nodded, glad of an errand, and quickly found her cloak before she slipped out into the walled kitchen garden.

The wind was chilly as she made her way to the covered herb beds at the back of the garden, but she didn’t care. It brought with it the salt tang of the sea and whenever she felt sad or confused the sea would calm her again.

She climbed up to the top of the stone wall and perched there for a glimpse of the sea. The outbuildings of the castle, the dairy and butcher’s shop and stables, blocked most of the view of the cliffs, but she could see a sliver of the grey waves beyond.

That sea could take her to London, she thought, and she would fix whatever there had hurt her family. She would tell the Queen all about it herself. And maybe, just maybe, she would see that handsome boy again...

‘Alys! You will catch the ague out here,’ she heard her father shout.

She glanced back to see him striding down the garden path, no cloak or hat against the cold wind, though he seemed not to notice. His attention was only on her.

‘Father, how far is London?’

He scowled. ‘Oh, so you heard that, did you? It is much farther than you could fly, my little butterfly.’ He lifted her down from the wall, spinning her around to make her giggle before he braced her against his shoulder. ‘Mayhap one day you will go there and see it for yourself.’

‘Will I see the Queen?’

‘Only if she is very lucky.’

‘But what if she does not want to see me? Because I am yours and Mother’s?’

Her father hugged her tightly. ‘You must not think such things, Alys. You are a Drury. Your great-grandmother served Elizabeth of York, and your grandmother served Katherine of Aragon. Our family goes back hundreds of years and your mother’s even more. The Lorca-Ramirez are a ducal family and there are no dukes at all in England now. You would be the grandest lady at court.’

Alys wasn’t so sure of that. Her mother and nursemaid were always telling her no lady would climb walls and swim in the sea as she did. But London—it sounded most intriguing. And if she truly was a lady and served the Queen well, the Drurys would have their due at long last.

She glanced back at the roiling sea as her father carried her into the house. One day, yes, that sea would take her to England and she would see its splendours for herself.

* * *

‘That lying whore! She has been dead for years and still she dares to thwart me.’ A crash exploded through the house as Edward Huntley threw his pottery plate against the fireplace and it shattered. It was followed by a splintering sound, as if a footstool was kicked to pieces.

John Huntley heard a maidservant shriek and he was sure she must be new to the household. Everyone else was accustomed to his father’s rages and went about their business with their heads down.

John himself would scarcely have noticed at all, especially as he was hidden in his small attic space high above the ancient great hall of Huntleyburg Abbey. It was the one place where his father could never find him, as no one else but the ghosts of the old banished monks seemed to know it was there. When he was forced to return to Huntleyburg at his school’s recess, he would spend his days outdoors hunting and his evenings in this hiding place, studying his Latin and Greek in the attic eyrie. Making plans for the wondrous day he would be free of his father at last.

He was nearly fourteen now. Surely that day would be soon.

Edward let out another great bellow. John wouldn’t have listened to the rantings at all, except that something unusual had happened that morning. A visitor had arrived at Huntleyburg.

And not just any visitor. John’s godfather, Sir Matthew Morgan, had galloped up the drive unannounced soon after breakfast, when John’s father was just beginning the day’s drinking of strong claret. When John heard of Sir Matthew’s arrival, he started to run down the stairs. It had been months since he heard from Sir Matthew, who was his father’s cousin but had a very different life from the Huntleys, a life at the royal court.

Yet something had held him back, some tension in the air as the servants rushed to attend on Sir Matthew. John had always been able to sense tiny shifts in the mood of the people around him, sense when secrets were being held. Secrets could so seldom be kept from him. His father used to rage that John was an unnatural child, that he inherited some Spanish witchcraft from his cursed mother and would try to beat it out of him. Until John learned to hide it.

It was secrets he felt hanging in the air that morning. Secrets that made him wait and watch, which seemed the better course for the moment. A fight always went better when he had gathered as much information as possible. Why was Sir Matthew there? He had only been at the Abbey for an hour and he already had John’s father cursing his mother’s memory.

And it had to be his mother Edward was shouting about now. Maria-Caterina was always The Spanish Whore to her husband, even though she had been dead for twelve years.

John glanced at the portrait hung in the shadowed corner of his hiding place. A lovely lady with red-gold hair glimpsed under a lacy mantilla, her hands folded against the stiff white-and-silver skirt of her satin gown, her green eyes smiling down at him. On her finger was a gold ring: the same one John now wore on his littlest finger.

One side of the canvas was slashed, the frame cracked, from one of Edward’s rages, but John had saved her and brought her to safety. He only wished he could have done the same in real life. To honour her, he tried to help those more helpless any time he could. As he had with that tiny, pretty girl once, when she was hit in the head with the football. He sometimes wondered where she was now.

He heard the echo of voices, the calm, slow tones of his godfather, a sob from his father. If Edward had already turned to tears from rage, John thought it was time for him to appear.

He unfolded his long legs from the bench and made his way out of the attic, ducking his head beneath the old rafters. He had had a growth spurt in his last term at school and soon he would need a larger hiding place. But soon, very soon by the grace of his mother’s saints, he would be gone from the Abbey for good.

He made his way down the ladder that led into the great hall. It had been a grand space when his great-grandfather bought the property from King Henry, bright with painted murals and with rich carpets and tapestries to warm the lofty walls and vaulted ceilings, but all of that had been gone for years. Now, it was a faded, dusty, empty room.

At the far end of the hall, his father sat slumped in his chair by the fire. He had spilled wine on his old fur-trimmed robe and his long, grey-flecked dark hair and beard were tangled. The shattered pottery remains were scattered on the floor, amid splashes of blood-red wine, but no one ventured near to clean it up.

Sir Matthew stood a few feet away, his arms crossed over his chest as he dispassionately surveyed the scene. Unlike Edward, he was still lean and fit, his sombre dark grey travelling clothes not elaborate, but perfectly cut from the finest wool and velvet. With his sword strapped to his side, he looked ready to ride out and fight for his Queen at any moment, despite his age.

What had brought such a man to such a pitiful place as Huntleyburg?

Sir Matthew glanced up and saw John there in the shadows. ‘Ah, John, my dear lad, there you are. ʼTis most splendid to see you again. How you have grown!’

Before John could answer, his father turned his bleary gaze to him, his face twisted in fury. ‘She has cursed me again,’ he shouted. ‘You and your mother have ruined my life! I am still not allowed at court.’

Sir Matthew pressed Edward back into his chair with a firm yet unobtrusive hand to his shoulder. ‘You know the reason you are not allowed at court has nothing to do with Maria-Caterina. In fact, she is the only reason your whole roof did not come crashing down on your head years ago.’

John looked up at the great hall’s ceiling, at the ancient, stained rafters patched with newer plaster. It was true his mother had been an heiress. But that money was long gone now.

‘She cursed me,’ Edward said pitifully. ‘She said the monks who once lived here would take their rightful home back and I would have naught.’

Sir Matthew gave him a distasteful glance. He poured out another goblet of wine and pressed it into Edward’s hand, smiling grimly as he gulped it down.

‘We have more serious matters to discuss now, Edward,’ Sir Matthew said. ‘Maria-Caterina is long gone and you have tossed away any chance you may have had. But it is not too late for John.’

‘John? What can he possibly do?’ Edward said contemptuously, without even looking at his son.

‘He can do much indeed. I hear from your tutors that you are most adept, John, especially at languages,’ Sir Matthew said, turning away from Edward and beckoning John closer. ‘That you should be sent to Cambridge next term. Do you enjoy your studies?’

Somewhere deep inside of John, in a spot he had thought long numbed, hope stirred. ‘Very much, my lord. I know my Greek and Latin quite well now, as well as French and Spanish, and some Italian.’

‘And your skills with the bow and the sword? How are they?’

John thought of the stag he had brought down for the supper table, one clean arrow shot. ‘Not bad, I think. You can ask the sword master at my school, I work with him every week.’

‘Hmm.’ Sir Matthew studied John closely, tapping his fingers against his sleeve. ‘And you are handsome, too.’

‘He gets it from his cursed mother,’ Edward muttered. ‘Those eyes...’

Sir Matthew peered closer. ‘Aye, you do have a dark Spanish look about you, John.’ He poured out even more wine and handed it to Edward without another glance. ‘Come, John, let us walk outside for a time. I haven’t long before I must ride back.’

John followed his godfather into the abbey garden. Like the house, they had once been a grand showplace, filled with the colour and scent of rare roses, the splash of fountains. Now it was brown and dead. But John felt more hope than he had in a long while. School had been an escape from home, a place where he knew he had to work hard. Was that hard work finally going to reward him? And with what?

‘You said I might be able to do much indeed, my lord,’ he said, trying not to appear too eager. To seem sophisticated enough for Cambridge and a career beyond. Maybe even something at court. ‘I hope that may be true. I wish to serve the Queen in any way I am able.’ And maybe to redeem the Huntley name, as well, if it was not lost for good. To bring honour to his family again would mean his life had a meaning.

Sir Matthew smiled. ‘Most admirable, John. The Queen is in great need of talented and loyal men like you, now more than ever. I fear dark days lie ahead for England.’

Darker days than now, with Spain and France crowding close on all sides, and Mary of Scotland lurking in the background at every moment? ‘My lord?’

‘The Queen has always had many enemies, but now they will grow ever bolder. I hope to raise a regiment to take to the Low Countries soon.’

‘Truly?’ John said in growing excitement. To be a soldier, to win glory on the battlefield—sure that would save the name of Huntley. ‘Might there be a place for me in your household there, my lord?’

Sir Matthew’s smile turned wry. ‘Perhaps one day, John. But you must finish your studies first. A mind like yours, adept at languages, will be of great use to you.’

John hid his flash of disappointment. ‘What sort of place might there be for me, then?’

‘Perhaps...’ Sir Matthew seemed to hesitate before he said, ‘Perhaps you have heard of my friend Sir Francis Walsingham?’

Of course John had heard of Walsingham. He was the Queen’s most trusted secretary, the keeper of many secrets, many dangers. ‘Aye, I know of him.’

‘He recently asked me about your progress. If matters do come to war with Spain, a man with connections and skills such as yours would be most valuable.’

John’s thoughts raced, a dizzying tidal pool of what a man like Walsingham might ask of him. ‘Because I am half-Spanish?’

‘That, of course, and because of your intelligence. Your—intuition, perhaps. I noticed it in you when you were a boy, that watchfulness, that—that knowledge. It is still there. Properly honed and directed, it will take you far.’

‘You think there will be danger from Spain soon? Is that why you are going to the Low Countries to fight them there?’

‘There will always be danger from Spain, my dear lad. Who knows what will happen in a few years, when you have finished your studies? Now, why don’t you tell me more of your schooling? What have you learned of mathematics there, of astronomy?’

John walked with Sir Matthew around the gardens back to the drive at the front of the house, where a servant waited with his horse. He told him about his schooling and asked a few questions about court, which Sir Matthew answered lightly.

‘Keep up with your studies, John, and do not worry about your father. I will see he comes to no harm,’ Sir Matthew said as he swung himself up into his saddle. ‘I must go now, but you will think about what I have said?’

‘Of course, my lord.’ John was sure he would think of little else. He bowed, and watched his godfather gallop away.

John looked back at the house. In the fading sunlight, Huntleyburg Abbey looked better than usual, its patches and cracks disguised. He would so love to restore it, to see its beauty come back to life, but he had never known how he would do that. Mayhap he could do it with secrets—Walsingham’s secrets, England’s secrets. But what would that be like? What path would his life follow? He wasn’t sure.

But he knew that if it took spy craft, working in the shadows, living half a life to restore the Huntley name his father had so squandered, he would do it. He would do anything, make any sacrifice, to bring back their honour. He vowed it then and there, to himself and his family. That would be his life.

Chapter Two (#u313f38b3-8dca-5081-a183-163efcbb9c2f)

Galway—early summer 1588

Alys, carrying a basket of linen to the laundry above the kitchens of Dunboyton Castle, heard an all-too-familiar sound floating up the stone stairs—the wailing sobs of some of the younger maidservants. Their panic had been hanging like a dark cloud over Dunboyton for days.

Not that she could blame them. She herself felt constantly as if she walked the sharp edge of a sword, about to fall one way or the other, but always caught in the horrible uncertainty of the middle. They said the Spanish Armada had left its port in Lisbon and was on its way to England, to conquer the island nation and all her holdings, including Ireland. Hundreds of ships, filled with thousands of men, coming to wage war.

She wished she could somehow banish the rumours that flew like dark ghosts down the castle corridors. It made her want to scream out in frustration.

Yet she could not. She was the lady of the castle now, as she had been in the nine years since her mother had died. She had to set an example of calm and fortitude.

She stepped into the laundry, and put down her basket with the others. She saw that the day’s work was not even half-finished, with linens left to boil unsupervised in the cauldrons, the air filled with lavender-scented steam so thick she could barely see through it.

‘Oh, my lady!’ one of the maids, young Molly, wailed when she saw Alys. ‘They do say that when the Spanish come, we will all be horribly tortured! That in their ships they carry whips and nooses, and brands to mark all the babies.’

‘I did hear that, too,’ another maid said, her voice full of doomed resignation. ‘That all the older children will be killed and the babies marked so after all might know their shame of being conquered.’

‘Don’t be silly,’ the old head laundress said heartily. ‘We will all be run through with swords and tossed over the walls into the sea before we can be branded.’

‘They say the Dutch in Leiden burned their own city to the ground before they let it fall into Spanish hands,’ another said. ‘We shall have to do the same.’

‘Enough!’ Alys said sternly. If she heard once more about the rumoured cruelties of the Spanish, people who were nowhere near Ireland, she would scream. What would her mother have said about it all? ‘If they are sailing at all, they are headed to England, not here, and they shall be turned back before they even get near. We are in no danger.’

‘Then why are all the soldiers marching into Fort Hill?’ Molly asked. ‘And why is Sir Richard Bingham riding out from Galway City to inspect the fortifications?’

Alys wished she knew that herself. Bingham had a cruel reputation after so bloodily putting down the chieftains’ rebellions years before; having him roaming the countryside could mean nothing good. But she couldn’t let the maids see that. ‘We are in more danger of a shortage of clean linen than anything else,’ she said, tossing a pile of laundry at Molly. ‘We must finish the day’s work now, Armada or not.’

The maids all grumbled but set about their scrubbing and stirring. As Alys turned to leave, she heard the whispers rustle up again. Whips and brands...

The stone walls felt as if they were pressing down on her. The fear and uncertainty all around her for so many days was making her feel ill. She—who prided herself on a sturdy spirit and practicality! A person had to be sturdy to live in such a place as Dunboyton. The cold winds that always swept off the sea, the monotony of seeing the same faces every day, the strangeness of the land itself, it had all surely driven many people mad.

Alys didn’t mind the life of Dunboyton now. Even if she sometimes dreamed of seeing other lands, the sparkle of a royal court or the sunshine of her mother’s Granada, she knew she had to be content with her father and her duties at the castle. It was her life and dreaming could not change it.

But now—now she felt as if she was caught in a confusing, upside-down nightmare she couldn’t wake from at all.

She had other tasks waiting, but she had to get away for just a few moments, to breathe some fresh air and clear away the miasma of fear the maids’ gossip had woven. She snatched a woollen cloak from the hook by the kitchen door and made her way outside.

A cold wind whipped around the castle walls, catching at her hair and her skirts. She hurried through the kitchen garden and scrambled over the rough stone wall into the wilder fields beyond, as she had done so often ever since she was a child. After her mother died, she would often escape for long rambles along the shore and up to the ruins of the abbey, and she would see no one at all for hours.

That was not true today. She followed the narrow path that led down from Dunboyton’s perch on the cliffs down to the bay. The spots that were usually deserted were today filled with people, hurrying on errands that she couldn’t identify, but which they seemed to think were quite vital. Soldiers both from her father’s castle regiment and sent from Galway City and the fort swarmed in a mass of blue-and-grey wool over the rocky beach.

Alys paused halfway along the path to peer down at them as they marched back and forth. Everyone said the Spanish were sweeping ever closer to England in their invincible ships and would never come this far north, but obviously precautions were still being taken, enough to frighten the maids. They said the Spanish had come here before, to try to help the chieftains defeat the English rulers, but they had been driven away then. Why would now be any different?

Whips and brands...hangings. Alys shivered and pulled her cloak closer around her. She remembered her mother’s tales of Spain, the way the candied lemons and oranges sent from her uncles in Andalusia would melt on her tongue like sunshine, and she could not reconcile the two images at all. Could the same people who had produced her lovely, gentle mother be so barbarous? And if so, what lay deep inside herself?

Her father was banished from the royal court, sent to be governor in this distant place because of her mother’s birthplace. What would happen to them now?

‘Alys!’ she heard her father call. ‘It is much too cold today for you to be here.’

She turned to see him hurrying up the pathway, the wind catching at his cloak and cap, a spyglass in his hand. He looked so much older suddenly, his beard turned grey, lines etched on his face, as if this new worry had aged him.

‘I won’t stay out long,’ she said. ‘I just couldn’t listen to the maids a moment longer.’

He nodded grimly. ‘I can imagine. Spreading panic now will help no one.’

‘Is there any word yet from England?’

‘Only that the ships have been gathering in Portsmouth and Plymouth, and militias organised along the coast. Nothing established as of yet. There have been no signal fires from Dublin.’

Alys gestured towards the activity on the beach. ‘Bingham is taking no chances, I see.’

‘Aye, the man does love a fight. He has been idle too long, since the rebellions were put down. I fear he will be in for a sharp disappointment when no Spaniard shows up for battle.’

Or if England was overrun and conquered before Ireland even had a chance to fight. But she could not say that aloud. She would start to wail like the maids.

Alys borrowed her father’s spyglass and used it to scan the horizon. The water was dark grey, choppy as the wind whipped up, and she could see no vessels but a few local fishing boats. It had been thus for weeks, the weather unseasonably cold, storm-ridden and unpredictable. This was usually the best time of the year to set sail, but not now. The Spanish would be foolhardy to try to land in such an inhospitable place, for so many reasons.

But faint hearts had not conquered the New World, or overrun and mastered the Low Countries. Anything could happen in such a world.

‘They say Medina-Sidonia is ordered to bring Parma’s land forces from the coast of the Netherlands to overrun England,’ her father said. ‘Why would they come here?’

‘They won’t,’ Alys said with more confidence than she felt. ‘This shall be a tale you tell your grandchildren by the fire one day, Father. The salvation of England by a great miracle.’ She handed him the spyglass and took his arm to go back up the path towards the castle.

‘If I have a grandchild,’ he said in a teasing grumble. They had bantered about such things many times before, his need for a grandchild to dandle on his lap. ‘I fear there are no proper gentlemen for you to marry here, my Alys, unless you take one of Bingham’s men down there.’

Alys glanced back at the soldiers, all of them alike in their helmets. ‘Nay, I thank you. If that is my choice, I shall end a spinster, keeping house here for you.’

Her father frowned. ‘My poor Alys. ʼTis true no one here is worthy of you. If you could but go to court...’

Alys had heard such things before, but she had long ago given up hope of such a grand adventure. ‘I admit I should like the fine gowns I would have to wear at court and learning the newest dances and songs, but I fear I should be the veriest country mouse and bring shame to you,’ she said lightly. ‘Besides, surely I am safer here.’

He patted her hand. ‘For now, mayhap. But not for ever.’

They made their way back into the castle, into the midst of the bustle and noise of everyday life. Nothing ever seemed to change at Dunboyton. Yet she could still hear the clang of battle preparations just outside her door.

Chapter Three (#u313f38b3-8dca-5081-a183-163efcbb9c2f)

Lisbon—April 1588

‘King Philip will hear Mass at St Paul’s by October, I vow,’ Lord Westmoreland, an English Catholic exile who had lived under King Philip’s sponsorship for many months, declared stoutly. He waved towards the grand procession making its way past his rented window, through the old, winding cobblestone streets of Lisbon. ‘And I have been promised the return of my estates as soon as he does.’

His friend and fellow English exile Lord Paget gave a wry smile. ‘He will have to get there first.’ And that was the challenge. The Armada was now assembled, hundreds of ships strong, but after much delay, bad weather, spoiled provisions and a rash of desertions.

‘How can you doubt he will? Look at the might of his kingdom!’ Lord Westmoreland cried.

John Huntley joined the others in peering out Lord Westmoreland’s window. It was an impressive sight, he had to admit. King Philip’s commander of his great Armada, the mighty Duke of Medina-Sidonia, rode at the head of a great procession from the royal palace to the cathedral, resplendent in a polished silver breastplate etched with his family seal and a blue-satin cloak lined with glossy sable. Beside him rode the Cardinal Archduke, his robes as red as blood against the whitewashed houses, and behind them was a long, winding train of sparkling nobility, riding four abreast. The colours of their family banners snapped in the wind, golds and reds and blues. The sun gleamed on polished armour and turned the bright satins and silks into a rippling rainbow.

There followed ladies in brocade litters, peering shyly from beneath their cobweb-fine mantillas at the crowds, and then humble priests and friars on foot. Their black-and-brown robes were a sombre note, one lost in the waves of cheers from the Spanish crowds. The conquered Portuguese stayed behind their window shutters.

Just out of sight, the ships moored in the Tagus River let off a deafening volley from their guns. The last time Spanish ships had sailed up that river, it had been to conquer and subjugate Portugal. Now they sailed out to overrun new lands, to make all the world Spanish.

But John knew there was more, much more, behind this glittering display of power. The Armada had been delayed for so long, their supplies ran desperately short even now, before leaving port. Sailors had been deserting and Spanish gangs roamed the streets of Lisbon, pressing men to replace them.

He had to find out more of the truth of the Armada’s situation, the certainty of her plans, so he could pass on the word before they sailed out of Lisbon. After that, unless they found a friendly port, he could send no more messages until he arrived in England, one way or another. All the long months of careful planning, all the puzzle pieces he had been painstakingly sliding into place, would have to be carried to their endgame now.

England’s future, the lives of its people, were at stake.

‘What think you, Master Kelsey?’ Lord Westmoreland asked John, using the pseudonym that had been his for years, ever since he ‘deserted’ the Queen’s armies in Antwerp and carried information to the Spanish. It had followed him now to Lisbon and beyond. ‘Shall we regain our English estates and see the people returned to the true church before year’s end?’

‘I pray so, my lord,’ John answered. ‘With God’s will, we cannot be thwarted. I long for my own home again, as we all do, after the injustices the false Queen has inflicted on my family. My Spanish mother would rejoice if she could see this day.’

‘Well said, Master Kelsey,’ Lord Paget said. ‘We will bring honour and justice back to our homeland at last.’

‘And we shall avenge the sacrifice of Queen Mary of Scotland,’ Lord Percy said. He spoke softly, but everyone gathered around him looked at him in surprise. Percy obviously burned with zeal for his cause, praying in the church of the Ascension near his home for hours at a time, but he seldom spoke.

‘Aye, the poor, martyred Queen,’ Westmoreland said uncertainly.

‘She was the first of us to truly witness the great cruelty of the heretic Elizabeth,’ Percy said. ‘The tears of Catholic widows, the poor children torn from their families and raised to damnation in the false church. I know how they suffer; I have seen their words in my letters from England.’

John wished he, too, could see those letters; the information they would contain about traitors to England, the aid they gave to the Queen’s enemies, would be invaluable. Who knew what their true plans were once they landed in England? But thus far, though Westmoreland was careless with his words and his correspondence, Percy was not.

John laid a gentle hand on Percy’s tense shoulder. The gold ring that had once been his mother’s, the ring he never took off, gleamed. ‘You shall see your family again soon.’

Percy glanced at John, a wild, desperate light in his eyes. ‘I pray so. You will help us, Master Kelsey. You understand and you shall be there when the ships land while we wait and pray here.’

Aye, John thought, he did understand. Though not in the way poor Percy thought. He knew that England had to remain free of Spain at all costs, that the cruelty and bloodshed he had seen in the Low Countries could not be carried to English shores.

‘We should leave soon, gentlemen,’ Westmoreland said. ‘We must take our places in the cathedral to see the Duke take up the sacred standard.’

A murmur went through the crowd, wine goblets were drained and everyone took up their fine cloaks and plumed caps.

‘I must join you later,’ John said. ‘I have an appointment first.’

‘With a fair lady of Lisbon, I dare say!’ Paget said with a hearty laugh.

John did not deny it, only grinned and shook his head, and took their ribald teasing. A sacred day for them it might be, but they would never eschew gossip about pretty women. He made his way out of the house and through a winding maze of the steep, old streets with their uneven cobbles and close-packed white houses. The crowd had dispersed as the procession made its way to the cathedral and most of the houses were shuttered again, as if nothing had happened.

He could hear the toll of the church bells in the distance, could smell the bitter whiff of smoke from the ships’ guns lingering in the air, but there were none to block his path. No one seemed to pay him any attention at all as he passed, despite the richness of his black-velvet mantel embroidered with gold and silver and his fine red-satin doublet.

Nonetheless, he took a most circuitous path, careful to be sure he was not trailed. He had been trained to be most observant for many years, ever since his godfather introduced him to Walsingham and his shadowy world. He had learned code-breaking along with languages at Cambridge, along with swordplay, firearms and the surreptitious use of needle-thin Italian daggers. He had honed those skills fighting in the Low Countries, then making his way at the Spanish court under Westmoreland’s patronage. He was never followed—unless he meant to be.

Now, all those years of work were coming to fruition. The danger England had long feared from Spain was imminent, ready to sail at any moment. He had to be doubly careful now.

There was a sudden soft burst of laughter and his hand went automatically to the hilt of his dagger, but when he peered around the corner of a narrow alleyway he saw it was only a young couple, wrapped in each other’s arms, their heads bent close together. The girl whispered something that made the man smile and their lips met in a gentle kiss.

John moved on, pushing down a most unwelcome feeling that rose up inside of him unbidden—a cold pang of loneliness. There was no time for such things in his life, no place for tenderness.

After the Armada was defeated and England was safe, after his task was done—mayhap then there could be such moments...

John gave a rueful laugh at himself. After that, if he even survived, which was unlikely, there would be another task, and another. Maybe one day he could restore Huntleyburg, even find a wife, but not for a long time. By then, he would be a veritable greybeard and beyond any mortal help from any lady. His father’s bitter ghost would have taken him over. But he could redeem his family’s honour, restore their good name and that had to be enough.

He finally found his destination, a public house at the crest of a steep lane. Its doorway and grimy windows looked over the red-tile roofs to the forest of ships’ masts that crowded the river port. It was an impressive sight—or would be if anyone in the dim, low-ceilinged, smoke-stained public room looked outside. It was not crowded, but there were enough people at the scarred tables for the middle of a day and they mostly seemed slumped in drunken stupors on their benches. The room had the sour smell of cheap ale and the illness that came from drinking too much of such ale.

John found his contact in a small private chamber beyond the main room, hidden behind a warren of narrow corridors. Its one window looked out on to an alleyway, perfect for an escape if needed. The man was small and nondescript, clad in plain brown wool with a black cap pulled over his wispy brown hair. He was someone that no one would look at twice on the street—his real strength. John hadn’t seen him since Antwerp.

‘The day draws nigh at last,’ he said as John drew up a stool and reached for the pitcher of ale.

‘’Tis not the best kept secret in Europe,’ John said. He had known this man for a long time and trusted him as much as he was able, which was not a great deal.

‘King Philip is not a man to make up his mind quickly. But now that he is ready to strike, even the Duke of Medina-Sidonia cannot warn him away.’

John thought of the Duke’s well-known qualms, the way he had first tried to turn down the ‘honour’ of the command, his worries about the lack of supplies, the poor weather. ‘And the Queen? Is she ready to strike in return?’

The man shrugged. ‘The English militias are woefully under-trained and lack arms, but the rumours of Spanish evils have spread quickly and they are ready to fight to the death if need be. If an army can be landed, that is.’

‘But England has greater defences than any land army.’

The man looked surprised John knew such a thing. ‘How many ships does King Philip command now?’

‘It is hard to say precisely. Ten galleons from the Indian Guard, nine of the Portuguese navy, plus four galleasses and forty merchant ships. That is only of the first and second lines. Thirty-four pinnaces to serve as scouts. Perhaps one hundred and thirty in all.’

‘Her Majesty has thirty-four galleons in her fleet, but Captain Hawkins has overseen their redesign most admirably,’ the man said. John nodded. Everyone knew that Hawkins, as Treasurer of Marine Causes and an experienced mariner, had been most insistent over vociferous protests that the Queen’s navy had to be modernised. ‘They are longer in keel and narrower in beam, much sleeker now that the large fighting castles were removed. They’re fast and slower to take on water. They can come about and fire on the old Spanish ships four times before they can even turn once.’

John absorbed this image as he sipped at the ale. ‘A ship of six hundred tons will carry as good ordnance as one of twelve hundred.’

‘Indeed. And Her Majesty’s guns, though fewer than King Philip’s, are newer. They have four-wheeled carriages, with longer barrels, and Hawkins’s new ships have a new continuous gun deck which can hold near forty-three guns.’

John nodded grimly. The San Lorenzo, Spain’s greatest galleon, held forty, but sixteen of them were small minions. Spain was indeed not prepared when it came to actual sea battle with England’s modern navy. But Spain was counting on land war with Parma’s superior forces, if they could be landed. ‘England is ready for sea battle.’

‘More than Spain could ever know or predict, I dare say.’

‘Spain sails knowing God will send them a miracle.’

‘So they will need it. Sailing with such an unwieldy, unprepared force can have no good end. Medina-Sidonia knows that.’ The man gave him a long, dark look. ‘To be on these ships is a dangerous proposition for any man.’

‘I do know it well, too. But information obtained from inside the ships could be of much use later.’

‘And once a path is decided upon, ʼtis impossible to turn back. I know that well.’ He finished his goblet of ale and rose to his feet. ‘God’s fortune to you, sir. I travel now to Portsmouth, one way or another, and will send your message to our mutual friend from there.’

John nodded and waited several minutes before following his contact from the ale house. He made his way back to his lodgings through streets turned empty and ghostly after the pageantry of the procession. The shutters were closed on the houses and everything seemed to hold its breath to see what would happen next.

John had been working towards this moment for so very long and, now that it was upon him, now that he was actually about to embark, he felt numb, distant from it all. He knew Sir Matthew would make sure his family’s name was restored if he died on the voyage and he himself could bring new glory to the Huntleys if he survived. It was what he had worked for, but at the moment it all seemed strangely hollow.

He found the house where he had lodgings, near the river wharves, and made his way up the staircase at the back of the building. It was noisier there; the dock workers did not have the luxury of locking themselves away until the Armada had sailed. They had to prepare the ships for the long voyage, and quickly. The sounds of shouts, of creaking ropes and snapping sails, floated over the crooked rooftops.

He could hear it even in his rooms, the small, bare, rented space that was exactly the same sort of place where he had lived for years. He barely remembered what being in one place was like, having a home to belong to. He unbuckled his sword and draped the belt over a stool, unfastening his doublet as he poured out a measure of wine.

But he was not alone. He could feel the presence of someone else, hear the soft scratching of a pen across parchment. He followed the sound to his small sitting room and found Peter de Vargas at his desk, the man’s pale head bent over a letter he was feverishly penning, as if time was running out. As it was for the men who were to sail at least.

John felt no alarm. Peter often borrowed his rooms, saying they were quieter than his family’s lodgings, and Peter seemed to have much to accomplish, though John had not yet deciphered what that was. He was a strange man, was Peter. Half-English, but fervent in the Catholic cause. He had befriended John when they first met in Madrid, and was a source of much information from the inner circle of the King’s court. John couldn’t help but pity him, though; Peter was a pale, sickly young man, but afire with zeal for his cause and eager to bring others into its work when he could.

He glanced up at John and his pale blue eyes were red-rimmed, bright as if with fever. ‘I did not see you at the cathedral,’ he said.

‘Nay, I could not find a place there, it was so crowded,’ John answered. ‘I watched from the street.’

‘Glorious, was it not? The cheers as the Duke raised the sacred standard were most heartening. God will surely bring us a miracle.’

It would take God to do so, John thought wryly, considering that poor preparations of the Spanish king. ‘Have you eaten?’

‘It is a fasting day,’ Peter answered. ‘I took a little wine. I need to send these letters before we sail.’

‘Who do you write to?’ John asked. ‘Your mother?’

‘Among others. I want them to know the glory of this cause.’ He glanced down at the letter he was working on. ‘This one—I do not know if it will reach its goal. I pray it must, for if anyone has to know all...’

‘It is this person?’ John said. Peter had often spoken of some mysterious correspondent, someone whose rare letters he treasured, someone who must know everything. Thus far John had had little luck finding out who it was. He thought it might be someone in England, a contact of Peter’s. He would soon find out who it was. Peter was a fool, dedicated to a cause that cared naught for him and would wreak destruction on half the world if it could. They had to be stopped and John would do whatever he had to in order to accomplish that.

If time did not run out for them all.

Chapter Four (#u313f38b3-8dca-5081-a183-163efcbb9c2f)

Galway—September

Alys could not sleep, despite the great lateness of the hour. The icy wind, which had been gathering off the sea all day, had grown into a howling gale, beating against the stone walls of the castle as if demons demanded entrance. The rain that had pounded down for days had become freezing sleet, always pattering at her window.

Every time she managed to doze off for a little while, strange dreams pulled her back into wakefulness. Fire-breathing dragons chased her, or the castle was turned into an icy fortress with everyone inside frozen. The long days of not knowing what would happen next, of waiting for messengers on the long journey from Dublin.

They said the Armada had been driven from England, defeated by Queen Elizabeth’s superior modern ships in battle at Gravelines, pushed back by great winds sent from God, but ships had been sighted wrecking in the storms off Ireland as they tried to flee along the coast and then towards home in Spain. They broke apart on the treacherous rocks, drowning hundreds, or the men straggled ashore to be robbed and killed.

Yet there were also tales, wilder tales, of armies storming ashore to burn Irish houses and take the plunder denied them in England. Or of Irish armies slaughtering any Spanish survivor who dared stagger on to land, mobs tearing them apart. The uncertainty was the worst and in the dark night nothing could distract her from her churning thoughts.

Alys finally pushed back the heavy tangle of blankets and slid down from her bed. The fire had died down to mere embers, leaving the chamber freezing cold. She quickly wrapped her fur-lined bed robe over her chemise and stirred the flames back to life before she went to peer out the window.

She could see little. During the day, her chamber looked down on to the front courtyard of the castle, where guests arrived and her father gathered his men when they had to ride out. Beyond the gates was a glimpse of the cliffs, the sea beyond. Tonight, the moon was hidden by the boiling dark clouds and the sky and the stormy sea melded into one. Only the churning white foam of the waves breaking on the rocks cast any light. It was a perilous night indeed. Any ship out there would be drowned.

Alys shivered and drew back from the cold wind howling past the fragile old glass. She had rarely been at sea, but she did remember the voyage that had brought her family to Ireland when she was a child. The coldness, the waves that tossed everything around, making her stomach cramp. The fear of the grey clouds suddenly whipping into a storm. How much worse it must be for men, weakened by battle and long weeks at sea, so far from their sunny homes.

She pushed her feet into her boots and slipped out of her chamber, unable to bear being alone any longer. Despite the late hour, the torches were still lit in their iron sconces along the corridor and the stairway, smoking and flickering. She couldn’t see anyone, all the servants were surely long retired, but she could hear the echo of angry voices coming from the great hall below.

Messengers had been riding in and out of Dunboyton all day to meet with her father. She had seen little of them, for her father had sent her out of the hall to see to the wine and meat and bread being served, but the snatches she heard of their worried conversations was enough to worry her as well. What was left of the Armada was indeed sailing along the Irish coast, putting into ports where they could, but what would happen next, whether they would fight or surrender or how many there were, no one seemed to know.

The rumours that raced through the kitchens and the laundry were even wilder, and it took all her time to calm the servants and keep the household running. Invasion or not, they still needed bread baked, cheese strained and linen washed.

She tiptoed to the end of the corridor, where she could hear her father’s weary voice, too low to make out any words, and the angry tone of his newest visitors. When they arrived after dinner, mud-splashed though they were, Alys saw they wore the livery of Sir William Fitzwilliam, Deputy of Ireland. Sir William had once savagely put down the Spanish and Papal troops who helped the Irish chieftains to rebel at Smerwick near ten years ago and vowed to do the same to any Armada survivors now, with the help of his brutal agent Richard Bingham.

Already stories flew that, farther south, soldiers and scavengers scoured the coast, robbing corpses and stealing the very clothes off the weak survivors, killing them or leaving them to die of the cold.

Alys could hear drifts of their words now, caught in the cold draught of the corridor.

‘...must be found wherever they land. The Irish people are easily led astray by foreign designs against the Queen’s realm,’ the deputy’s man said, punctuated by the splash of wine. They would have to order more casks very soon. ‘If the old chieftains join them...’

‘We have not seen a hint of rebellion in years,’ her father answered. ‘The Spanish will never make it as far as Galway.’

‘Ships have already been sighted from the fort. Sir William only has twelve hundred men in the field now. He has sent messages to all the Queen’s governors along the coast to pass on his orders.’

‘And what orders would those be?’ her father asked wearily.

‘That any Spaniard daring to come ashore shall be apprehended, questioned thoroughly, and executed forthwith by whatever means necessary.’

Alys, horrified, backed away from those cold, cruel voices, their terrible words. She spun around and hurried towards the winding stairs that led up to the walkway of the old tower. Men always kept watch on those parapets, which had a view of the sea and the roads all around, and tonight the guards were tripled. Torches lit up the night, flickering wildly in the wind and reflecting on the men’s armour. The wind snatched at her cloak, but she held it close.

‘Lady Alys!’ one of the men cried. ‘You shouldn’t be out here in such cold.’

‘I won’t stay long,’ she said. ‘I just—I couldn’t stay inside. I thought if I could just see...’

He gave an understanding nod. ‘I know, my lady. Imagining can be worse than anything. My wife is sure we will be stabbed through in our beds with Spanish swords, she hasn’t slept in days.’

Alys shivered. ‘And shall we?’

He frowned fiercely. ‘Not tonight, my lady. ʼTis quiet out there. Only a fool would brave the sea on a night like this.’

A fool—or a poor devil with no choice, whose wounded ship had been blown far off course. Alys did have fears, aye, just like this soldier’s wife. Terrible things had happened in other lands conquered by the Spanish. But they were defeated now, beaten down and far from home. And how many of the men in those ships had been there of their own free will? Her fear warred with her pity.

She saw her father’s spyglass abandoned on a parapet, and took it up to peer out at the night. She could see nothing but the dark sea, the moonlight struggling to break through. Then, for an instant, she thought she saw a pinprick of light bobbing far out to sea. She gasped and peered closer. Perhaps it was there, but then it vanished again.

Alys sighed. Now she was imaging things, just like everyone else at Dunboyton. She tucked the spyglass into the folds of her cloak and made her way back inside to try to sleep again.

* * *

The Concepción had become a floating hell, carrying its cargo of the damned farther from any hope at every moment.

John felt strangely dispassionate and numb as he studied the scene around him, as if he looked at it through a dream.

The Concepción had sustained a few blows at Gravelines, wounds that had been hastily patched, and her mainsail was shredded in the storm that blew them off course and pushed them far to the north of the Irish coast, out of sight of the other ships. But she had managed to limp along, praying that a clear course would open up and push them up and over the tip of the island and on a course for Scotland, where friendly Frenchmen might be found.

Yet the weather had only grown worse and worse, a howling gale that blew the vessel around haplessly, destroying what sails they had left and battering her decks with constant rain that leaked to the decks below. There were too many weak men and too few to raise the sails or steer. Salt was caked on the masts like frost.

Even if the skies did clear, the men were too ill to do much about it. They were like a ghost ship, tossed around by the towering waves.

John propped himself up by his elbow on his bunk to study the scene around him. The partitions that had been put up in Lisbon to separate the noble officers from the mere sailors had been torn down, leaving everyone in the same half-gloom, the same reeking mess. Everything was sodden, clothes, blankets, water seeping up from the floorboards and dripping on to their heads, but not a drop to drink except what rain could be caught. The ship’s stores were long gone, except for a bit of crumbling, wormy biscuit. The smells of so many people packed into so small a space were overwhelming.

So many were starving, ill of ship’s fever and scurvy, and could only lie in their bunks, moaning softly.

John wanted to shout with it all, but he feared he too lacked the energy to even say a word. There was little sleep to be had, with the constant pounding of the waves against the wounded hull, the whine of the pumps that couldn’t keep up with the rising water, the groans of the men, the occasional sudden cries of ladies’ names, ladies who would probably never be seen again.

John spent much time thinking over every minute that had happened since he left Lisbon, since he left England, really. All he had done to try to redeem his family’s name, his own honour, all he had done thinking it would keep England safe. Surely he had given all he could, all his strength? What waited now? Perhaps the ease of death. But something told him he was not yet done with his earthly mission. More awaited him beyond these hellish decks.

He felt the press of his papers tucked beneath his shirt, carefully wrapped in oilskin to protect them. Would he ever have the chance to deliver them, to see the green fields of England he had fought so hard to protect? He could barely remember what Huntleyburg looked like. Perhaps he had lived a lie for too long now—it would be better if he died in it, too.

He heard a deep, rasping cough and looked to the next bunk where Peter de Vargas lay. Peter’s greatest desire was to see England Catholic again; he spoke of it all the time. John found him innocent, if very foolish and fanatical, and willing to spill any secrets he had.

But now Peter burned with fever, as he had for days, and was too weakened to fight it away. At night, John heard him cry out to someone in his nightmares, his voice full of yearning. John gave him what water and food could be found, but he feared little could be done for the young man now.

Yet it seemed now Peter had summoned up a burst of strength and he sat up writing frantically with a stub of pencil. His golden hair, matted with salt, clung to his damp brow, and his eyes burned brightly.

‘Peter, you should be resting,’ John said. He climbed out of his own bunk, wincing as the salt sludge of the floor washed over his bare, bleeding feet. He was trying to save what was left of his boots, though he was not quite sure why now. He pulled them on. He wrapped the ragged edges of his blanket around Peter’s thin shoulders.