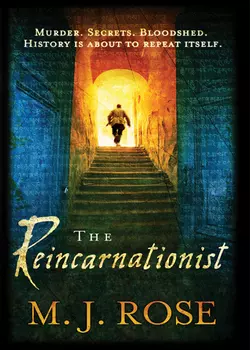

The Reincarnationist

M. J. Rose

A bomb in Rome, a flash of bluish-white light, and photojournalist Josh Ryder's world exploded. From that instant nothing would ever be the same.As Josh recovers, his mind is increasingly invaded with thoughts that have the emotion, the intensity, the intimacy of memories. But they are not his memories. They are ancient– and violent. A battery of medical and psychological tests can't explain Josh's baffling symptoms.And the memories have an urgency he can't ignore– pulling him to save a woman named Sabina– and the treasures she is protecting. But who is Sabina? Desperate for answers, Josh turns to the world-renowned Phoenix Foundation– a research facility that scientifically documents cases of past life experiences.His findings there lead him to an archaeological dig and to Professor Gabriella Chase, who has discovered an ancient tomb– a tomb with a powerful secret that threatens to merge the past with the present. Here, the dead call out to the living, and murders of the past become murders of the present.

THE

Reincarnationist

“M.J. Rose delivers a tale that goes beyond chills and thrills.

It’s a delight of intrigue with a clever twist. Not a disappointing page.”

—Steve Berry, The Templar Legacy

“THE REINCARNATIONIST is a riveting thriller – smart, original, and so well written. Rose hooks you on the first pages of the book, where current-day murders pull the reader into ancient secrets and shocking revelations, and keeps you turning till the stunning denouement.”

—Linda Fairstein, Bad Blood

“A breakneck chase across the centuries.

Fascinating and fabulous.”

—David Morrell, Creepers

“Both unnerving and mesmerising, THE

REINCARNATIONIST by M.J. Rose will excite anyone who’s ever had the slightest curiosity about past lives.

The story is packed with unforgettable characters, breath-taking drama, and fascinating research, cementing M.J. Rose’s reputation as a master storyteller.”

—Gayle Lynds, The Last Assassin

“A triumph! A breathtaking, smart and inventive novel that dazzles while it thrills. THE REINCARNATIONIST

is one of the year’s best reads.”

—David J. Montgomery, Chicago Sun-Times & Philadelphia Inquirer

“I simply believe that some part of the human self or soul is not subject to the laws of space or time.”

—Carl Jung

AUTHOR’S NOTE

While The Reincarnationist is a work of fiction, whenever possible I relied on the facts of history and preexisting theories about the subject of reincarnation to construct the backbone of this tale.

Life in ancient Rome, paganism, early Christianity and ancient beliefs in reincarnation, as well as the Vestal Virgins, are as history recorded them. So are the descriptions of Vestals’ duties, domicile and temple, as well as the rules they lived by. Their vows of chastity were sacrosanct, and they were buried alive for breaking them.

I have taken liberties when discussing their involvement with the Memory Stones—which are wholly my own invention, as are the Memory Tools.

Many of the locations in this novel exist. The Riftstone Arch is in Central Park; the Church of the Capuchins is where I describe it in Rome. Several tombs of Vestals have been discovered in various locations around Rome, but Sabina’s was not found, as there is no record of a Vestal by that name.

The Phoenix Foundation does not, unfortunately, exist. And while Malachai and Dr. Talmage are entirely fictitious, I was inspired by the amazing Dr. Ian Stevenson, who has done past life regressions with over 2,500 children.

Josh, Natalie and Rachel experience past life regressions in ways that are similar to those of people I’ve met and read about, but their stories are entirely my invention.

My own reading and research into reincarnation theory has been an ongoing process, and what I described in these pages was culled from the tenets and writings of those who have studied and believed over thousands of years. Included at the end of this novel is a list of books for those of my readers who wish to delve further into this fascinating concept.

Please visit Reincarnationist.org for more information.

Also available byM.J. Rose

THE HALO EFFECT

THE DELILAH COMPLEX

THE VENUS FIX

The

Reincarnationist

M. J. Rose

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

This book is dedicated to my remarkable editor,

Margaret O’Neil Marbury, who convinced me

I could climb this mountain.

&

To Lisa Tucker and Douglas Clegg, wonderful writers

and friends, who threw me a lifeline every

step of the way.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This is my ninth published novel and the one I have been writing the longest, since before I even knew I wanted to be a writer, when my mother first introduced me to the idea of reincarnation. I missed her a little less while I was working on this book and I’m certain she would love it best of all.

There are so many people I’d like to thank, starting with Loretta Barrett, Nick Mullendore and Gabriel Davis of Loretta Barrett Books for all their hard work and excellent advice. Thanks to the whole team at MIRA Books—especially Donna Hayes, Dianne Moggy, Alex Osusek, Laura Morris, Craig Swinwood, Heather Foy, Loriana Sacilotto, Katherine Orr, Marleah Stout, Stacy Widdrington, Pete McMahon, Gordy Goihl, Ken Foy, Fritz Servatius and Cheryl Stewart, Rebecca Soukis and Sarah Rundle. I am indeed blessed to have all of these amazing people in my corner and behind this book. It’s been a wonderful experience—thank you.

Thanks to Mayapryia Long, who gave me the right information at the right moment. For support, advice, information or just great conversation, thanks to Mara Nathan, Jenn Risko, Carol Fitzgerald, Judith Curr, Mark Dressler, Barry Eisler, Diane Vogt, Amanda’s father, Suzanne Beecher, David Hewson, Shelly King, Emily Kischell, Stan Pottinger, Elizabeth’s fiancé, Simon Lipskar, Katherine Neville, the Rome-Arch Listserv, Meryl Moss and all the International Thriller Writers.

My gratitude to each bookseller, librarian and every reader.

As always to my loving family: Gigi, Jay, Jordan, my father and Ellie.

And to Doug Scofield, for the calm in the storm, the eternal optimism and the music.

Chapter 1

They will come back, come back again,

As long as the red earth rolls.

He never wasted a leaf or a tree.

Do you think he would squander souls?

—Rudyard Kipling

Rome, Italy—sixteen months ago

Josh Ryder looked through the camera’s viewfinder, focusing on the security guard arguing with a young mother whose hair was dyed so red it looked like she was on fire. The search of the woman’s baby carriage was quickly becoming anything but routine, and Josh moved in closer for his next shot.

He’d just been keeping himself busy while awaiting the arrival of a delegation of peacekeepers from several superpowers who would be meeting with the pope that morning, but like several other members of the press and tourists who’d been ignoring the altercation or losing patience with it, he was becoming concerned. Although searches went on every hour, every day, around the world, the potential for danger hung over everyone’s lives, lingering like the smell of fire.

In the distance the sonorous sound of a bell ringing called the religious to prayer, its echo out of sync with the woman’s shrill voice as she continued to protest. Then, with a huge shove, she pushed the carriage against the guard’s legs, and just as Josh brought the image into that clarity he called “perfect vision,” the kind of image that the newspaper would want, the kind of conflict they loved captured on film, he heard the blast.

Then a flash of bluish white light.

The next moment, the world exploded.

In the protective shadows of the altar, Julius and his brother whispered, reviewing their plans for the last part of the rescue and recovery. Each of them kept a hand on his dagger, prepared in case one of the emperor’s soldiers sprang out of the darkness. In Rome, in the Year of their Lord 391, temples were no longer sanctuaries for pagan priests. Converting to Christianity was not a choice, but an official mandate. Resisting was a crime punishable by death. Blood spilled in the name of the Church was not a sin, it was the price of victory.

The two brothers strategized—Drago would stay in the temple for an hour longer and then rendezvous with Julius at the tomb by the city gates. As a diversion, that morning’s elaborate funeral had been a success, but they were still worried. Everything depended on this last part of their strategy going smoothly.

Julius drew his cape closed, touched his brother’s shoulder, bidding him goodbye and good luck, and skulked out of the basilica, keeping to the building’s edge in case anyone was watching. He heard approaching horses and the clatter of wheels. Flattening himself against the stone wall, Julius held his breath and didn’t move. The chariot passed without stopping.

He’d finally reached the edge of the porch when, behind him, like a sudden avalanche of rocks, he heard an angry shout split open the silence: “Show me where the treasury is!”

This was the disaster Julius and his brother had feared and discussed, but Drago had been clear—even if the temple was attacked, Julius was to continue on. Not turn back. Not try to help him. The treasure Julius needed to save was more important than any one life or any five lives or any fifty lives.

But then a razor-sharp cry of pain rang out, and ignoring the plan, he ran back through the shadows, into the temple and up to the altar.

His brother was not where he’d left him.

“Drago?”

No answer.

“Drago?”

Where was he?

Julius worked his way down one of the dark side aisles of the temple and up the next. When he found Drago, it wasn’t by sound or by sight—but by tripping over his brother’s supine body.

He pulled him closer to the flickering torches. Drago’s skin was already deathly pale, and his torn robe revealed a six-inch horizontal slash on his stomach crossing a vertical gash that cut him all the way down to his groin.

Julius gagged. He’d seen eviscerated carcasses of both man and beast before and had barely given them a passing glance. Sacrifices, felled soldiers or punished criminals were one thing. But this was Drago. This blood was his blood.

“You weren’t … supposed to come back,” Drago said, dragging every syllable out as if it was stuck in his throat. “I sent him … to look in the loculi … for the treasures. I thought … Stabbed me, anyway. But there’s time … for us to get out … now … now!” Drago struggled to raise himself up to a sitting position, spilling his insides as he moved.

Julius pushed him down.

“Now … we need … to go now.” Drago’s voice was weakening.

Trying to staunch the blood flow, Julius put pressure on the laceration, willing the intestines and nerves and veins and skin to rejoin and fuse back together, but all he accomplished was staining his hands in the hot, sticky mess.

“Where are the virgins?” The voice erupted like Vesuvius without warning and echoed through the interior nave. Raucous laughter followed.

How many soldiers were there?

“Let’s find the booty we came here for,” another voice chimed in.

“Not yet, first I want one of the virgins. Where are the virgin whores?”

“The treasury first, you lecherous bastard.”

More laughter.

So it wasn’t one man; a regiment had stormed the temple. Shouting, demanding, blood-lust coating their words. Let them pillage this place, let them waste their energy, they’d come too late: there were no pagans to convert, no treasure left to find and no women left to rape, they’d all already been killed or sent into hiding.

“We have to go …” Drago whispered as once again he fought to rise.

He’d stayed behind to make sure everyone else got out safely. Why him, why Drago?

“You can’t move, you’ve been hurt—”Julius broke off, not knowing how to tell his brother that half of his internal organs were no longer inside his body.

“Then leave me. You need to get to her … Save her and the treasures … . No one … no one but you …”

It wasn’t about the sacred objects anymore. It was about two people who both needed him desperately: the woman he loved and his brother, and the fates were demanding Julius sacrifice one of them for the other.

I can’t let her die and I can’t leave you to die.

No matter which one he chose, how would he live with the decision?

“Look what I found,” one of the soldiers shouted.

Screams of vengeance reverberated through the majestic hall. A shriek rang out above all the other noise. A woman’s cry.

Julius crawled out, hid behind a column and peered into the nave. He couldn’t see the woman’s upper body, but her pale legs were thrashing under the brute as the soldier pumped away so roughly that blood pooled under her. Who was the poor woman? Had she wandered in thinking she’d find a safe haven in the old temple, only to find she’d descended into hell? Could Julius help her? Take the men by surprise? No, there were too many of them. At least eight he could see. By now the rape had attracted more attention, drawing other men who forgot about their search to crowd around and cheer on their compatriot.

And what would happen to Drago if he left his side?

Then the question didn’t matter because beneath his hands, Julius felt his brother’s heart stop.

He felt his heart stop.

Julius beat Drago’s chest, pumping and trying, trying but failing to stimulate the beating. Bending down, he breathed into his brother’s mouth, forcing his own air down his throat, waiting for any sign of life.

Finally, his lips still on his brother’s lips, his arm around his brother’s neck, he wept, knowing he was wasting precious seconds but unable to stop. Now he didn’t have to choose between them—he could go to the woman who was waiting for him at the city gates.

He must go to her.

Trying not to attract attention, he abandoned Drago’s body, backed up, found the wall and started crawling. There was a break in the columns up ahead; if he could get to it undetected, he might make it out.

And then he heard a soldier shout for him to halt.

If he couldn’t save her, Julius would at least die trying, so, ignoring the order, he kept moving.

Outside, the air was thick with the black smoke that burned his lungs and stung his eyes. What were they incinerating now? No time to find out. Barely able to see what lay ahead of him, he kept running down the eerily quiet street. After the cacophony of the scene he’d just left, it was alarming to be able to hear his own footsteps. If someone was on the lookout the sound would give him away, but he needed to risk it.

Picturing her in the crypt, crouched in the weak light, counting the minutes, he worried that she would be anxious that he was late and torment herself that something had gone dangerously wrong. Her bravery had always been as steadfast as the stars; it was difficult even now to imagine her afraid. But this was a far different situation than anything she’d ever faced, and it was all his fault, all his shame. They’d risked too much for each other. He should have been stronger, should have resisted.

And now, because of him, everything they treasured, especially their lives, was at stake.

Tripping over the uneven, cracked surfaces, he stumbled. The muscles in his thighs and calves screamed, and every breath irritated his lungs so harshly he wanted to cry out. Tasting dirt and grit mixed with his salty sweat as it dripped down his face and wet his lips, he would have given anything for water—cold, sweet water from the spring, not this alkaline piss. His feet pounded the stones and more pain shot up through his legs, but still he ran.

Suddenly, raucous shouting and thundering footfalls filled the air. The ground reverberated, and from the intensity he knew the marauders were coming closer. He looked right, left. If he could find a sheltered alcove, he could flatten himself against the wall and pray they’d run past and miss him. As if that would help. He knew all about praying. He’d relied on it, believed in it. But the prayers he’d offered up might as well have been spit in the gutter for the good they’d done.

“The sodomite is getting away!”

“Scum of the earth.”

“Scared little pig.”

“Did you defecate yourself yet, little pig?”

They laughed, trying to outdo each other with slurs and accusations. Their chortles echoed in the hollow night, lingered on the hot wind, and then, mixed in with their jeers, another voice broke through.

“Josh?”

No, don’t listen. Keep going. Everything depends on getting to her in time.

A heavy fog was rolling in. He stumbled, then righted himself. He took the corner.

On both sides of him were identical colonnades with dozens of doors and recessed archways. He knew this place! He could hide here in plain sight and they would run by and—

“Josh?”

The voice sounded as if it was coming to him from a great blue-green distance, but he refused to stop for it.

She was waiting for him … to save her … to save their secrets … and treasures… .

“Josh?”

The voice was pulling him up, up through the murky, briny heaviness.

“Josh?”

Reluctantly, he opened his eyes and took in the room, the equipment and his own battered body. Beyond the heart rate, blood oxygen and blood pressure monitor flashing its LED numbers, the IV drip and the EKG machine, he saw a woman’s worried face watching him. But it was the wrong face.

This wasn’t the woman he’d been running to save.

“Josh? Oh, thank God, Josh. We thought …”

He couldn’t be here now. He needed to go back.

The taste of sweat was still on his lips; his lungs still burned. He could hear them coming for him under the steady beat of the machines, but all he could think about was that somewhere she was alone, in the encroaching darkness, and yes, she was afraid, and yes, she was going to suffocate to death if he didn’t reach her. He closed his eyes against the onslaught of anguish. If he didn’t reach her, he would fail her. And something else, too. The treasures? No. Something more important, something just beyond his consciousness, what was it—

“Josh?”

Grief ripped through him like a knife slitting open his chest, exposing his heart to the raw, harsh reality of having lost her. This wasn’t possible. This wasn’t real. He’d been remembering the chase and the escape and the rescue as if they had happened to him. But they hadn’t. Of course they hadn’t.

He wasn’t Julius.

He was Josh Ryder. He was alive in the twenty-first century.

This scene belonged sixteen hundred years in the past.

Then why did he feel as if he’d lost everything that had ever mattered to him?

Chapter 2

Rome, Italy—the present Tuesday, 6:45 a.m.

Sixteen feet underground, the carbine lantern flickered, illuminating the ancient tomb’s south wall. Josh Ryder was astounded by what he saw. The flowers in the fresco were as fresh as if they’d been painted days before. Saffron, crimson, vermilion, orange, indigo, canary, violet and salmon blossoms all gathered in a bouquet, stunning against the Pompeii-red background. Beneath him, the floor shimmered with an elaborate mosaic maze done in silver, azure, green, turquoise and cobalt: a pool of watery tiles. Behind him, Professor Rudolfo continued explaining the importance of this late fourth-century tomb in his heavily accented English. At least seventy-five, he was still spry and energetic, with lively, coal-black eyes that sparkled with excitement as he talked about the excavation.

He’d been surprised to have a visitor at such an early hour, but when he heard Josh’s name, Rudolfo told the guard on duty that yes, it was fine, he was expecting Mr. Ryder later that morning with the other man from the Phoenix Foundation.

Josh had woken before dawn. He rarely slept well since his accident last year, but last night’s insomnia was more likely due to the time change—having just arrived in Rome that day from New York—or the excitement of being back in the city where so many of his memory lurches took place. Too restless to stay in the hotel, he grabbed his camera and went for a walk, not at all sure where he was going, But something happened while he was out.

Despite the darkness and his ignorance of the city’s layout, he proceeded as if the route had been mapped out for him. He knew the path, even if he had no idea of his final destination. Deserted avenues lined with expensive stores gave way to narrow streets and ancient buildings. The shadows became more sinister. But he kept going.

If he’d passed anyone else, he hadn’t noticed them. And even though it had seemed like a thirty-minute walk, it turned out to have taken more than two hours. Two hours spent in a semi-trance. He’d watched the night change from blue-gray to pale gray to a lemony-pink as the sun came up. He’d seen lush green hills develop the way the images in a photograph did in a chemical bath. From nothing to a shadow to a sense of a shape to a real form, but he didn’t know if he’d stopped to take any shots of the scenery. The whole episode was both disconcerting and astonishing when it turned out that, seemingly by chance, he’d stumbled onto the very site he and Malachai Samuels had been invited to view later that morning.

Or not by chance at all.

The professor didn’t ask why he was so early or question how he’d found the dig. “If it were me, I wouldn’t have been able to sleep, either. Come down, come down.”

Content to let the professor assume enthusiasm had brought him there at six-thirty in the morning, Josh breathed deeply and took a first tentative step down the ladder, refusing to allow his mind to dwell on the claustrophobia he’d suffered his whole life and which had intensified since the accident.

Strains of music from Madame Butterfly that had first caught Josh’s attention and then drawn him up this particular hill were louder now, and he concentrated on the heartbreaking aria as he descended into the dimly lit chamber.

The space was larger than he’d anticipated, and he exhaled, relieved. He’d be able to tolerate being there.

The professor shook his hand, introduced himself, then turned down the volume on the dusty black plastic CD player and began the tour.

“The crypt is—I will do this for you in feet, not meters—eight feet wide by seven feet long. Professor Chase—Gabriella—and I believe it was built in the very last years of the fourth century. Until we have the carbon dating back we can’t be positive. But from some of the artifacts here, we think it was 391 A.D., the same year the cult of the Vestal Virgins ended. Such decoration is atypical for this type of burial chamber, so we believe it must have been intended for someone else and then used for the Vestal when her inconstancy was discovered.”

Josh lifted his camera to his eye, but before he took a shot he asked if the professor minded. Nothing short of a bomb had ever stopped him from taking a photo when he was working for the Associate Press. Then six months ago he’d taken a leave of absence to work as a videographer and photographer of children who came to the Phoenix Foundation for help with their past-life regression memories. Since then, he’d gotten used to asking for permission before shooting. In return, he had access to the world’s largest and most private library on the subject of reincarnation as well as the chance to work with the foundation’s principals.

“It’s fine, yes, but would you clear it with either Gabriella or me before you show the pictures or release them to anyone? Everything here is still a secret we are trying to keep until we have additional information about exactly what we have discovered. We don’t want to create false excitement if we’re wrong about our find. Better to be safe, no?”

Josh nodded as he focused and clicked the shutter. “What did you mean by the Vestal’s inconstancy?”

“Maybe that is the wrong word, I’m sorry. I meant the breaking of her vows. That’s better, no?”

“What vows? Were the Vestals nuns?”

“Pagan nuns, yes. Upon entering the order they took a vow of chastity, and the punishment for breaking that vow was to be buried alive.”

Josh felt an oppressive wave of sadness. As if on autopilot, he depressed the shutter. “For falling in love?”

“You are a romantic. You will enjoy Rome.” He smiled. “Yes, for falling in love or for giving in to lust.”

“But why?”

“You need to understand that the religion of ancient Rome was based on a strict moral code that stressed truthfulness, honor and personal responsibility while demanding steadfastness and devotion to duty. They believed that every creature had a soul, but they were also very superstitious, worshipping gods and spirits who had influence over every aspect of their lives. If all the rituals and sacrifices were performed properly, the Romans believed the gods would be happy and help them. If they weren’t, they believed the gods would punish them. Contrary to public misinformation, the ancient religion was quite humane in general. Pagan priests could marry, and have children and …”

The faint scents of jasmine and sandalwood that usually accompanied his memory lurches teased Josh, and he fought to stay attuned to the lecture. He felt as if he’d always known about these painted walls and the maze beneath his feet but had forgotten them until this moment. The sensations that usually accompanied the waking nightmares he’d been experiencing since the accident were rocking him: the slow drift down, the undulating, the prickles of excitement running up his arms and his legs, the submergence into that atmosphere where the very air was thicker and heavier.

He ran in the rain. His soaked robe was heavy on his shoulders. Under his feet the ground was muddy. He could hear shouting. He stumbled. Struggled to get up.

Focus, Josh intoned in some other section of his brain where he remained in the present. Focus. He looked through the lens at the professor, who was still talking, using his hands to punctuate his words, causing the light beam to crisscross the tomb wildly, illuminating one corner and then another. As Josh followed with his camera, he felt the grip on his body relax and he let out a sigh of relief before he could stop himself.

“Are you all right?”

Josh heard Rudolfo as if he was on the other side of a glass door.

No. Of course he was not all right.

Sixteen months before, he’d been on assignment here in Rome, which turned out to be the wrong place at the wrong time. One minute he’d been photographing a dispute between a woman with a baby carriage and a guard, and the next a bomb was detonated. The suicide bomber, two bystanders and Adreas Carlucci—the security guard—were killed. Seventeen people were wounded. No motive had been discovered. No terrorist group had claimed the incident.

The doctors later told Josh they hadn’t expected him to live, and when he finally came to in the hospital forty-eight hours later, scattered bits of what seemed like memories started to float to the surface of his consciousness. But they were of people he’d never met, in places he’d never been, in centuries he’d never lived.

None of the doctors could explain what was happening to him. Neither could any of the psychiatrists or psychologists he saw once he was released. Yes, there was some depression, which was expected after an almost-fatal accident such as the one he’d suffered. And of course, post-traumatic stress syndrome could produce flashbacks, but not of the type he was suffering: images that burned into his brain so he had no choice but to revisit them over and over, torturing himself as he probed them for meaning, for reason. Nothing like dreams that fade with time until they’re all but forgotten, these were endlessly locked sequences that never changed, never developed, never revealed any of the layers that hid beneath their horrific surface.

These were blue-black-scarlet chimeras that came during the day when he was awake. They obsessed him to the point of becoming the final stress in an already-broken marriage and set him apart from an entire phalanx of friends who didn’t recognize the haunted man he’d become. All he cared about was finding an explanation for the episodes he’d experienced since the accident. Six full blown, dozens of others he managed to fight back and prevent.

As if they were made of fire, the hallucinations burned and singed and scorched his ability to be who he’d always been, to function, to sustain some semblance of normalcy. Too often, when he caught sight of himself in a mirror, he blanched. His smile didn’t work right anymore. The lines in his face had deepened seemingly overnight. The worst of it was in his eyes, as if someone else was in there with him waiting, waiting, to get out. He was haunted by the thoughts he couldn’t stop from coming, like a great rising flood.

He lived in fear of his own mind, which projected the fragmented kaleidoscopic images: of a young, troubled man in nineteenth-century New York City, of another in ancient Rome caught up in a violent struggle and of a woman who’d given up everything for their frightening passion. She shimmered in moonlight, glistening with opalescent drops of water, crying out to him, her arms open, offering him the same sanctuary he offered her. The cruelest joke was the intensity of his physical reaction to the visions. The lust. The rock-hard lust that turned his body into a single painful craving to smell her scent, to touch her skin, to see her eyes soaking him up, to feel her taking him into her, looking down at her face softened in pleasure, insanely, obscenely hiding nothing, knowing there was nothing he was holding back, either. They couldn’t hold back. That would be unworthy of their crime.

No, these were not posttraumatic stress flashbacks or psychotic episodes. These shook him to his core and interfered with his life. Tormented him, overpowered him, making it impossible for him to return to the world he’d known before the bombing, before the hospital, before his wife ultimately gave up on him.

There was a possibility, the last therapist said, that there was something neurological causing the hallucinations. So Josh visited a top neurologist, hoping—as bizarre as it was to hope such a thing—that the doctor would find some residual brain trauma as a result of the accident, which would explain the waking nightmares that plagued him. He was disconsolate when tests showed none.

Josh was out of choices—nothing was left but to explore the impossible and the irrational. The quest exhausted him, but he couldn’t give up; he needed to understand even if it meant accepting something that he couldn’t imagine or believe: either he was mad, or he’d developed the ability to revisit lives he’d lived before this one. The only way he would know was to find out if reincarnation was real, if it was truly possible.

That was what brought him to the Phoenix Foundation’s Drs. Beryl Talmage and Malachai Samuels, who, for the past twenty-five years, had recorded more than three thousand past-life regressions experienced by children under the age of twelve.

Josh took another photograph of the south corner of the tomb. The smooth, cold metal case felt good in his hands, and the sound of the shutter was reassuring. Recently he’d given up digital equipment and had been using his father’s old Leica. It was a connection to real memories, to sanity, to support, to logic. The way a camera worked was simple. Light exposed the image onto the emulsion. Developing the film was basic chemistry. Known elements interacted with paper treated with yet other known elements. A facsimile of an actual object became a new object—but a real one—a photograph. A mystery unless you understood the science. Knowledge. That was all he wanted. To know more—to know everything—about the two men he had been channeling since the accident. Damn, he hated that word and its association with New Age psychics and shamans. Josh’s black-and-white view of the world, his need to capture on film the harsh reality of the terror-filled times, did not jibe with someone who channeled anything.

“Are you all right?” the professor asked again. “You look haunted.”

Josh knew that, had seen it when he looked in the mirror; glimpsed the ghosts hiding in the shadows of his expression.

“I’m amazed, that’s all. The past is so close here. It’s incredible.” It was easy enough to say because it was the truth, but there was more he hadn’t said that was amazing. As Josh Ryder, he’d never before stood in that crypt sixteen feet under the earth. So then how did he know that behind him, in a dark corner of the tomb the professor hadn’t yet shown him or shone the light on, there were jugs, lamps and a funerary bed painted with real gold?

He tried to peer into the darkness.

“Ah, you are like all Americans.” The professor smiled.

“What do you mean?”

“Impertinent … no … impatient.” The professor smiled yet again. “So what it is it you are looking for?”

“There’s more back there, isn’t there?”

“Yes.”

“A funerary bed?” Josh asked, testing the memory. Or the guess. After all, they were in a tomb.

Rudolfo shined the light into the farthest corner, and Josh found himself staring at a wooden divan decorated with carved peacocks adorned with gold leaf and studded with pieces of malachite and lapis lazuli.

Something was wrong: he’d expected there to be a woman’s body lying on it. A woman’s body dressed in a white robe. He was both desperate to see her and dreading it at the same time.

“Where is she?” Josh was embarrassed by the plaintive despair in his voice and relieved when the professor anticipated his question and answered it.

“Over there, she’s hard to see in this light, no?” In a long slow move, the professor swept the lantern across the room until it illuminated the alcove in the far corner of the west wall.

She was crouched on the floor.

Slowly, as if he were in a funeral procession, walking down a hundred-foot aisle and not a seven-foot span, Josh made his way to her, knelt beside her and stared at what was left of her, gripped by a grief so intense he could barely breathe. How could a past-life memory, if that’s what it was—something he didn’t believe in, something he didn’t understand—make him sadder than he’d ever been in his life?

There, in a field, in the Roman countryside at 6:45 in the morning, inside a newly excavated tomb that dated back to the fourth-century A.D., was proof of his story at its end. Now, if he could only learn it from the beginning.

Chapter 3

I call her Bella because she is such a beautiful find for us,” Professor Rudolfo said, shining the lamp on the ancient skeleton. He was aware of Josh’s emotional reaction. “Each day, since Gabby and I discovered her, I spend this time in the morning alone with her. Communing with her dead bones, you might say.” He chuckled.

Taking a deep breath of the musty air, Josh held it in his chest and then concentrated on exhaling. Was this the woman he only knew as fractured fragments? A phantom from a past he didn’t believe in but couldn’t let go of?

His head ached. The information, present and past, crashed in waves of pain. He needed to focus on either then or now. Couldn’t afford a migraine.

He shut his eyes.

Connect to the present, connect to who you know you are.

Josh. Ryder. Josh. Ryder. Josh Ryder.

This was what Dr. Talmage taught him to do to stop an episode from overwhelming him. The pain began subsiding.

“She teases you with her secrets, no?”

Josh’s “yes” was barely audible.

The professor stared at him, trying to take his mental temperature. Thinking—Josh could see it in the man’s eyes—that he might be crazy, he resumed his lecturing. “We believe Bella was a Vestal Virgin. Holy and revered, they were both protected and privileged. Tending the fire and cleaning the hearth was a woman’s job in ancient times. Not all that different nowadays, no matter how hard women have tried to get us men to change.” The professor laughed. “In ancient Rome, that flame, which was entirely practical and necessary for the survival of society, eventually took on a spiritual significance.

“According to what is written, tending the state hearth required sprinkling it daily with the holy water of Egeria and making sure the fire didn’t go out, which would bring bad luck to the city—and was an unpardonable sin. That was the primary job of the Vestals, but …”

As the professor continued to explain, Josh felt as if he were racing ahead, knowing what he was going to say next, not as actual information, but as vague recollections.

“Each Virgin was chosen at a very young age—only six or seven—from among the finest of Rome’s families. We cannot imagine such a thing now, but it was a great honor then. Many girls were presented to the head priest, the Pontifex Maximus, by anxious fathers and mothers, each hoping their daughter would be picked. After the novitiate was chosen, the girl was escorted to the building where she would live for the next three decades: the large white marble villa directly behind the Temple of Vesta. Immediately, in a private ritual witnessed only by the other five Vestals, she’d be bathed, her hair would be arranged in the style brides wore, a white robe would be lowered over her head and then her education would begin.”

Josh nodded, almost seeing the scene play out in his mind, not quite sure why he was able to picture it so precisely: the young, anxious faces, the crowd’s excitement, the solemnity of the day. The professor’s question broke through the dreamscape and jolted Josh back to the present.

“I’m sorry, what did you say?” Josh asked.

“I was requesting that you not discuss anything I am telling you or that you will see with the press. They were here all of yesterday trying to get us to reveal information we aren’t ready to. And not just the Italian press. Your press, too. Dozens of them, following us. Like hungry dogs, they are. One man especially, I can’t remember his name… . Oh, yes. Charlie Billings.”

Josh knew Charlie. They’d been on assignment together a few years before. He was a good reporter and they’d stayed friends. But if he was in Rome it wouldn’t be good for the dig: it was hard to keep a story away from Charlie.

“This Billings hounded me and Gabriella until she talked to him. What is that expression? On the record? So the story ran and the crowds came. Students of pagan religions, some academics, but mostly those who belong to modern-day cults devoted to resurrecting the ancient rituals and religion. They were very quiet and reverential. Behaving as if this was a still sacred site. They didn’t bother us. It was the traditional churchgoers who started the small riot and all the problems. Stomping around and protesting and shouting out silly things such as we are doing the devil’s work and that we would be punished for our sins. They misunderstand Gabby and me. We are scientists, no? Then, last night, I received a call from Cardinal Bironi in Vatican City who offered me an obscene amount of money to sell him what we’ve found here and not make it public. Based on what he offered, he—or the people who have put up the money—are very afraid of what we might have found. That’s what happens when the word pagan is whispered in the Holy City.”

“But why? They’re the ones with all the power.” “Bella could add to the existing controversy over the trivial role women now play in the church compared to ancient times. It is a very popular argument and a big problem that modern religion gives women less of a role than ancient religion.” The professor shook his head. “And then,” he said softly, “there is the other issue. Any artifact that doesn’t have a cross on it can be viewed as a threat. Especially if these artifacts have something to do with reincarnation, as Gabriella and your bosses believe.” “Why reincarnation? Because of the absolution problem?” “Yes, imagine if man believed he alone bore responsibility for his eternal rest, that it is within his own control to get to heaven. No Father, no Son, no Holy Ghost. What would happen to the power the Church holds over our souls? Imagine the worldwide confusion and rebellion and exodus from the Church if reincarnation were ever proved.”

Josh nodded. In the past few months, he’d heard variations on this theme from Dr. Talmage. His eyes returned to Bella. Even as a corpse, her intensity was like a strong wind on a beach—there was nowhere to go to escape its force. He took a step closer to her.

“Are you curious how we have certified Bella as a Vestal?” the professor asked.

“There’s no question she was a Vestal,” Josh answered too quickly, and then worried that Rudolfo had picked up on his slip.

From the professor’s curious glance, he had. “How do you know that?”

He must be more careful. “I misunderstood what you said, I’m sorry. Professor, please, how can you certify that she was a Vestal?”

Rudolfo grinned as if he had not just pleaded with Josh to ask this very question. His warm eyes twinkled and he launched into his explanation with gusto. “We have written records about the Vestals that describe certain details, each of which we see here. Although this tomb does not conform to the barren type of pressed-dirt enclosure most often used when Vestals were put to death, this woman was buried alive—the punishment reserved for those nuns who broke their vows—not to starve to death but to suffocate. That’s the reason for those jugs. One for water, the other for milk—” He pointed to the roughhewn earthenware. “The very presence of the bed confirms it. You don’t bury a dead man or woman with a bed. Or an oil lamp, for that matter.”

“Why do you think she was over there in the corner, though? Not sleeping on the cot? As the oxygen ran out it would have made her tired. Wouldn’t she have gone to sleep where it was comfortable?”

“Very good, that’s one of our questions, too. It’s also very confusing why sacred objects were buried with her, because ancient Romans weren’t like the Egyptians. Their dead were not outfitted for the afterlife. Other than the lamp and the water and the milk, we didn’t expect to find anything else here.”

Josh’s head pounded again. “What kind of objects did you find?”

The professor pointed to a wooden box in the mummy’s hands. “She has been holding on to that for sixteen hundred years. Exciting, no?”

Josh instantly recognized it. No, that was impossible. He must have seen a photograph of a similar box in a museum. Even more confusing, despite its familiarity, he had no idea what it was. “Have you opened it yet?”

The professor nodded. “To come across a fine carved fruit-wood box like that and not open it? I don’t know many archaeologists who could resist. It’s much older than Bella. Gabby and I think it dates back to before 2000 B. C., maybe as far back as 3000 B. C., and it doesn’t appear to be Roman at all, but Indian. We need to wait for the carbon dating.”

“And inside? What is inside?” Pinpricks of excitement ran up and down Josh’s arms.

“We can’t be certain until we do more work and take many tests, but we think they are the Memory Stones of the legendary Lost Memory Tools that your own Trevor Talmage wrote about.”

“What are you basing that on?”

“The words carved here and here.” He pointed to the border running around the perimeter of the box. “We believe these are the same lines found on an ancient Egyptian papyrus currently in the British Museum. The same lines Trevor Talmage translated in 1884. Do you know about that?”

Josh nodded. Talmage was the founder of the Phoenix Club—what was now the Phoenix Foundation. And Josh had read the entire “Lost Memory Tools” folder of original notes and translations that had been found behind a row of books in the library during the 1999 renovation at the Foundation.

He was given the gift of a great bird who rose from fire to show him the way to the stones so he could pray upon them with song and lo! All of his past would be shown unto him.

As Josh recited the words, a voice inside his head spoke them in another language that sounded alien and archaic.

“That’s the same translation that Wallace Neely used,” Rudolfo said.

“Who?” The name tickled Josh’s consciousness.

“Wallace Neely was an archeologist who worked here in Rome in the late 1800s. Several of his digs were financed by your Phoenix Club. He found the original text that Talmage was in the process of translating at the time of his death … .”

He continued talking as Josh recalled a flashback he’d had six months ago, on the first day he’d walked into the Phoenix Foundation.

Percy Talmage, home for the summer break from Yale, was in the dining room, listening to his uncle Davenport talk about protecting the club’s archeological investments in Rome. His uncle mentioned the archeologist they’d been financing. His name was Wallace Neely and he was searching for the Lost Memory Tools.

And now, here in this ancient tomb, sitting beside the professor, another memory surfaced, but not one that belonged to him; Josh was remembering for someone in the past. He was remembering for Percy.

Percy was just eight years old the first time he’d heard about the tools. His father had shown him the ancient manuscript he was translating. It had been written by a scribe who said the tools were not just a legend. They existed. The scribe had seen them and given a full description of each of the amulets, ornaments and stones.

“The tools are important,” Trevor said to his son, “because history is important. He who knows the past controls the future. If the tools exist and if they can help people rediscover their past lives, you, me—and every member of the Phoenix Club—need to ensure this power is used for the good of all men, not selfishly exploited.”

Percy didn’t understand just how important it was for years. And years.

Was it possible that Josh had traveled halfway around the world to come back to where he’d started? Like so many things, this couldn’t be a coincidence. He needed time to work out the connections, but that time wasn’t now; the professor was still talking.

“In the 1880s Neely purchased several sites in and around this area, a practice that was very common then,” the professor explained. “People bought the land they wanted to excavate so they could own the spoils outright. The club went into partnership with Neely and helped pay for the excavations, which could explain why the same inscription appears in both his journal and Talmage’s notes.”

Josh peered down at the intricately carved wooden box clasped in the mummy’s hand. In its center was a bird rising out of a fire, a sword in its talons. It was almost identical to the coat of arms carved into the Phoenix Foundation’s front door. In the border, around the perimeter, he saw the markings that Rudolfo had pointed out.

“Do you know what language this is?”

“Gabriella has plans to be in touch with experts in the field. She believes they could be an ancient form of Sanskrit.”

“I thought she was an expert?”

“She is. In ancient Greek and Latin. This is neither.”

Josh was confused about something. “You said this tomb was intact when you found it?”

“Yes.”

“So how could Neely have been here?”

“We don’t believe he—or anyone else—ever worked on this site. The pages we have from his journal indicate he excavated two sites nearby but found nothing. He’d gone to work on a third site, but we don’t know what happened there. His journal abruptly ended while he was in the middle of that dig.”

“Abruptly?”

“He was killed. There’s very little known about the circumstances.”

“But you have the journal?”

“We have some pages.”

“Where did you get them?”

“Ask Gabby. She brought them to me along with the grant to take up where Neely stopped.”

“And now you think you’ve found what he and the men who belonged to the Phoenix Club were looking for.”

The professor nodded. “We think so. At least some of it, but there are so many unknowns still.” He pointed to a slightly discolored area on the wall near where the mummy crouched. “That was hidden by a tapestry and we don’t know why. Or why we found a knife beside Bella, because typically Roman women were never buried with weapons. And why is the knife broken? What was she doing?”

Taking a long breath, Rudolfo looked down at the creature. “Oh, Bella. What secrets do you have?” The professor got down on his knees and leaned toward her.

“Talk to me, my Belladonna,” he whispered in an intimate voice.

Josh experienced a flash of a completely unfounded and unexpected emotion: a white-hot surge of jealousy unlike anything he’d ever felt for any lover he’d ever had. He wanted to rush over and pull Rudolfo away, to tell him he had no business leaning in so close, no right to get so near to her. Josh hadn’t known that this corpse even existed an hour before, but his recollections had taken over and in his mind he saw muscles appearing, then being covered by flesh, the flesh plumping out her face, neck, hands, breasts, hips, thighs and feet, all coming to life, her lips pinking, her eyes being colored a deep blue. The remnants of her coppery cotton robe turned white as they’d been years before. Only her long and wavy red hair remained the same—parted in the middle and braided into two ropes that hung past her shoulders.

She was a corpse now, skin like leather and brittle bones, but once … once … she’d been beautiful. A million images crashed inside his head. Centuries of words he’d never heard before. One louder than the rest. He snatched it out from the cacophony.

Sabina.

Her name.

Chapter 4

“I’m not sure you believe the story you just told me, but I believe it,” the professor said after Josh told an abbreviated version of what had happened to him in the past sixteen months and how he had come to be there so early that morning. “Every time you looked at her, I could tell there was something else you were seeing. I knew there was some connection more than just curiosity.” He seemed inordinately pleased with himself.

Yes, in the gloomy light, if Josh squinted, the mummy was almost a living woman crouched there in the corner, not a sixteen-hundred-year-old shell whose sleep had recently been disturbed.

A breeze from the opening to the tomb whooshed through the space, and a single wisp of a curl escaped from her braids.

She’d always been so proud of how she looked, of being well kept; how she’d hate that her hair had come undone. He could see her unbraiding it, turning it into a glorious jasmine-and-sandalwood-perfumed silk tent that covered them both as they kissed in the dark, in secret, under the trees. Her hair fell on his cheeks, his lips and twisted in and out of his fingers: it was the thread that wove them together, that would keep them from ever separating.

He didn’t think about what he was doing, it happened too fast, he simply reached out and grasped the curl and—

“No,” the professor shouted as he pulled Josh’s arm away. “She is fragile. That she is still intact is a miracle. If you touch her, she might break. Do you understand?”

The sensation of her hair on his fingers was almost more than Josh could bear. Turning away, rubbing his hands together, he found and then focused on the ancient oil lamp, blackened with soot on the ground. It looked as if she’d pushed it as close as she could get it to the alcove in the wall, at that discolored patch of earth.

The gates in his mind opened an inch wider. Josh’s head throbbed with the new rush of information. He needed to go deeper into the lurches instead of skimming them, but he could only be in one place at a time. Then or now. Not both.

Give in to it. Concentrate on what happened. Long ago. Long ago, right here. What happened here?

Josh, oblivious to the professor’s warnings that he might be defiling the dig, fell to his knees and clawed at the dirt wall with his bare hands. He had something to prove. To her. To himself. He didn’t know what it was—only that something that lay behind this partition would vindicate him.

“What are you doing?” the professor asked, horrified. “Stop!”

As if the dream had become reality and the reality had slipped away, Josh only vaguely heard the professor cautioning him to stop, barely felt the man’s hands trying to pull him back. The man’s protestations didn’t matter. Not anymore.

The dirt was packed tightly, but once he dug the first few handfuls out the rest was easier to break through. The wall, which was only four or five inches thick, three-and-a-half-feet tall and three feet wide, broke apart in chunks, revealing what appeared to be the opening of a tunnel. A piece of rock ripped the skin on his left palm, but he couldn’t stop, he was almost there.

A gush of cool, stale air rushed toward him.

Ancient air.

Sixteen-hundred-year-old molecules and particles filled his lungs, along with the scents of jasmine and sandalwood. He climbed in, despite the claustrophobia that reached out and grabbed hold of him and the out-of-control panic that threatened his progress. Sweating suddenly, now gasping for breath, he desperately wanted to turn around, but the pull of the tunnel was more powerful than the paranoia.

The space only accommodated him on all fours. So, on his hands and knees, he crawled forward, immediately engulfed in darkness, and sadness crushed him as if the air itself was weighted down with it. He struggled on slowly, going five yards in, ten yards in, then twenty and then twenty-five. The professor continued calling out for Josh to stop, but he couldn’t: there was an end point somewhere up ahead and he needed to reach it.

He navigated a turn, gulping for air, and froze, incapable of moving. It would be easier to die now than to go forward. Picturing the dirt that surrounded him, he saw it coming loose, breaking free, raining down on him. So real was the manifestation of his fear, he could taste the grit in his mouth, feel it in his nostrils, closing up his throat.

But something important waited for him up ahead. More important than anything else in the world.

“Stop, stop!” Rudolfo yelled, his voice coming from a far distance, distorted and echoing.

Oh, how he wanted to, but he managed another five yards.

The professor’s voice reached him, but more faintly now. “What if there is a drop and you can’t see it? What if you fall? I can’t get to you.”

No, and that was one of the fears that plagued him now. A sudden break, a hollow cave beneath this one, a descent into subterranean darkness.

He sensed the energy in the tunnel and let it pull him forward. Almost alive, it begged him to come, to come deeper into its shadows, to explore what was waiting, what had been waiting for so damn long.

“Come back at least and get a flashlight…. What you are doing is dangerous… .”

Of course, the professor was right. Josh had no idea what lay ahead, but he was too close now to turn back, not sure that if he did he would find the nerve to start over.

He moved forward another foot and then he felt it. Something long and hard under his fingers. Trying to identify it through touch, he examined its contours and its circumference.

A long stick? Some kind of weapon?

The surface was slightly pitted. It wasn’t wood. Or metal.

No. He knew through logic and through a primordial instinct.

It was bone.

Human bone.

Chapter 5

New York City—Tuesday, 2:00 a.m.

Four months after her aunt’s unexpected death from a heart attack, Rachel Palmer learned that a woman who lived in her building was assaulted on the stoop as she fished in her bag for her keys. Much to her chagrin, Rachel couldn’t shake how uncomfortable she felt in the brownstone after that: always looking over her shoulder when she opened the front door, rushing up the stairs, quickly throwing the bolt behind her and never sleeping through the night. When she mentioned that she was going to start looking for another place, her uncle Alex suggested she temporarily move into his palatial duplex at Sixty-Fifth and Lexington.

Even though he never said it or showed it, she knew he was lonely—Alex and her aunt Nancy had been inseparable the way certain childless couples can be—and even though he was only sixty-two-years old, Rachel sensed it was going to be a long time before he sought the companionship of another woman.

Rachel’s father had abandoned her mother when she was a child, and Alex had stepped in, becoming much more to her than an uncle. Now she was glad to keep him company and enjoy the inviolability the building’s doorman plus her uncle’s round-the-clock security system gave her.

Without realizing it, Rachel got used to the companionship, and in the past two days since Alex had left for a week-long business trip to London and Milan, she’d had trouble getting to sleep. Having given up for the night, she was in bed with the lights on, simultaneously watching an old movie on television, sipping a glass of white wine and reading the next morning’s news on her laptop.

Tomb Belongs to Vestal Virgin

By Charlie Billings

Rome, Italy

It was confirmed yesterday that the recent excavation outside of the city gates is believed to be the burial site of one of ancient Rome’s last Vestal Virgins.

“We were fairly certain that the tomb dated back to the late fourth century, specifically from 390 to 392 A.D. The pottery and other artifacts we’ve found further bears this out. Barring any more surprises, we believe the woman buried here was a Vestal,” said Gabriella Chase, professor of archeology at Yale University, a specialist in ancient religions and languages, who, along with Professor Aldo Rudolfo from the University of Rome La Sapienz, has been working at sites in this area for three years.

“What makes this particular excavation especially exciting is that the woman buried here may be one of the last six Vestals,” Chase said. “After more than a thousand years, the cult of the Vestals came to an end in 391 A.D., coincident with the rise of Christianity under the reign of Emperor Theodosius.”

The noise emanating from the television disappeared. The lights in the bedroom dimmed. Rachel tried to keep reading, tried to stay in bed, feel the sheets under her hands, pillows at her back, but deep inside of her, her heart fluttered, raced; the promise of understanding gave her a physical thrill. A whole world that she didn’t know anything about presented itself like an uncut diamond. All she needed to do was step forward and explore it.

Entering, she was bedazzled by a scene that glittered in hyper-realistic sunshine. Warmth surrounded her and held her, cosseting her like a summer wind. Comforted and excited at the same time. The radiance was inside her now, and she felt light, so light she was flying, moving faster and faster and at the same time aware of each sensation as if it was happening in very slow motion.

The sun burned her cheeks. The smell of the heat filled her nostrils. Her body hummed as if she were an instrument someone played. She heard music, but it didn’t have anything to do with tones or keys or chords or melody. It was pure rhythm. Her heart changed its beat to keep pace. Her breathing altered to the new timing.

Then it was cold. Shivering, she peered through a glass door, through a crack in the curtains, spying on two men, both hunched over a desk.

“This is what I came to Rome for. What I gave up hope I’d ever find,” said the one she knew well, though she couldn’t remember his name.

Then she saw the magic colored stones and their reflections. Flashes of blue and green lights filled her with a desperate pleasure. It was a drug. She wanted to stand there and try to understand how they melded into each other, creating a hundred new shades: a rainbow of emerald melting into peacock blue melting into cobalt melting into sea green melting into sage melting into teal, into red, burgundy and crimson.

“This is important, a real find.” The man’s voice was hard like the edges of the stones and she felt little cuts on her skin where his words touched her. She didn’t care if she bled. She wanted to be part of this moment and this pain and this excitement. It surpassed anything that had ever happened to her before.

And then it was over.

Dizzy, Rachel put her head back and stared up at the ceiling. Her skin was burning hot. How long had the episode lasted? A half hour?

She picked up her wine. No, the glass was still cold.

Only minutes?

Except it seemed so real, so much more real than any daydream she’d had before. It wasn’t just an image stuck in her head. She thought she’d been sucked through time and space and had been somewhere else for a moment, not seeing the scene played out but being part of it.

Leaving her bedroom, she walked down the sweeping staircase and headed toward the kitchen. She needed something stronger than wine. She wished her uncle was home so she could tell him what had happened; it was the kind of thing he’d be fascinated by. No, nothing had happened. She must have been tired, after all, fallen asleep without knowing it, dreamed the villa and the man and the colors.

After pouring a brandy, she took a few sips, the fiery liquid stinging her eyes and burning the back of her throat, and then, instead of going back to her bedroom, she went into her uncle’s den and sat down at his desk. She felt safer there, surrounded by all his books. That was when she noticed, tucked into his desk blotter so that it was hardly noticeable, a corner of newsprint.

She pulled it out.

Tomb Possibly Dates Back 1600 Years.

Rachel shivered as she read the dateline. This story had been filed two weeks ago, in Rome, by that same reporter. No, there was nothing portentous about Alex tearing out this article. He was a collector. Tombs yielded ancient artifacts. The house was filled with objets d’art. She was overreacting. It was just a coincidence.

Wasn’t it?

What else could it be?

Chapter 6

Rome, Italy—Tuesday, 7:45 a.m.

Josh felt a sharp, searing, twisting pain in his middle. Taking his breath away. Stunning him with its intensity. He broke out in a second cold sweat. The pain worsened. He needed to get out of the tunnel; his panic was making it almost impossible for him to breathe. If he hyperventilated now he might suffocate, and the professor was too old and too slow to get to him in time. He needed to get out now.

But he couldn’t turn around. The space was too narrow. How was that possible? He’d gotten here, hadn’t he?

He sat back on his haunches and reached out both of his hands, feeling for the walls on either side. His fingers hit dirt almost immediately. The tunnel must have narrowed as it continued without him being aware of it.

The reality of the darkness descended on him. He was fully conscious and present. The smell of the dank air nauseated him and he was suddenly, inexplicably sure he was going to die in this tunnel. Now. Any minute. In this small, narrow space that was not big enough for a man to turn around in.

A small rock came loose and pinged him on the shoulder. What if his presence caused an avalanche of stone, and he became trapped in this passageway to hell? His chest tightened and his breathing became increasingly labored. He tried a series of contortions but couldn’t manage to turn.

His panic heightened.

A few deep breaths.

A full minute of focusing on one fact: he’d gotten this far, that meant he would be able to get out.

Of course. Just go backward. Don’t try to turn now. Don’t turn until the space widens again.

The gripping frenzy broke, the anxiety vanished and Josh became aware of a very different pain. The tunnel was filled with rubble. Small pebbles and sharp stones ripped his palms, pressed down deep to the bone in his knees. He held his hands up to his face, forgetting for a minute that there was no light—he couldn’t see what he’d done to his flesh but could guess from the overpowering sweet smell of blood. Struggling out of his shirt, he banged his head on the tunnel’s roof. Ripping the fabric with his teeth, he used the strips to wrap around both of his bleeding palms. There was nothing he could do for his knees.

Crawling backward was awkward and slow going, and he’d only gone a few feet when he heard the voices: the professor and another man were speaking in loud, rapid Italian. Something about the cadence made him think they were arguing.

Moving steadily, doing his best to ignore the pain, he finally reached the point where he could turn around. After that he moved faster, and seconds later rounded a curve. Ahead was a straightaway at the end of which he could see the interior of the tomb.

The professor stood in pale yellow lantern light, fists by his sides, facing someone Josh couldn’t see but could hear. The stranger’s voice was cruel and demanding. The professor’s response was angry and defiant. No translation was necessary. The professor was in jeopardy.

Josh crawled forward another foot. Then another.

The stranger crossed in front of the tunnel opening and became somewhat visible. From his clothing, he looked like the man guarding the site whom Josh had encountered when he’d first arrived.

Nothing to worry about, then.

Except they continued to argue; hot words were flung back and forth so rapidly that even if Josh had spoken basic Italian, he wouldn’t have been able to understand.

The shouting escalated and the professor tried to push the guard away, but the man stepped back adroitly and Rudolfo lost his balance, falling to the ground. The guard put his foot on the professor’s chest.

It was almost impossible to crawl faster. There was too much debris in the tunnel, and despite the makeshift bandages, his wounds throbbed. But he must. This was tied to the past, a chance for Josh to right a wrong. It was inches from his reach, almost within his grasp.

A stone pierced the skin on his right knee. Involuntarily, Josh swore under his breath. Then he froze. The only chance he had to stop whatever was going on was to take the guard by surprise.

Then everything happened so quickly that he would have missed it if he’d glanced away for five seconds, but his eyes were riveted to the action. He just wasn’t fast enough to stop any of it. The entire tomb was in his sight now. Far away still, but visible.

The guard leaned down, bent over the ancient corpse and snatched the fruitwood box out of her arms.

“No, no …” The professor clawed at the guard, jumping on him like an angry monkey, grabbing at him, for the box.

As if the professor were a mere annoyance, the large man flung Rudolfo off. The professor landed on the ground, close to the mummy. Too close. His arm hit her and her head fell forward—she was in danger of coming apart. Rudolfo let out an agonized scream and rushed to her side. But before he could reach her, the guard kicked her with his heavy boot and her intact form splintered at the waist with a sickening crack.

While the professor kneeled at Sabina’s side, the guard opened the fruitwood box, pulled out what looked like a leather pouch, shook its contents into his hand, pocketed whatever he’d found and then hurled the box at the professor. It hit his shoulder and broke apart, the pieces flying into the air and then landing haphazardly.

Josh was only ten yards away, planning on how he was going jump out, take the man by surprise, tackle him and get back what he’d taken.

Hand forward.

Knee forward.

Hand forward.

Knee forward.

Rudolfo stood, dizzy, rocking back and forth. The guard hurried toward the ladder.

With only a few feet left to go, Josh inched steadily forward. The way the tunnel was angled he could see the whole scene, and he watched with growing dread as the professor rushed toward the opening of the tomb.

The guard had started up the ladder.

Rudolfo tried to grab hold of the man’s shirt, to pull him down, to stop him.

The guard pushed the professor’s hand away as if it were nothing more than an insect and took another step up.

Not ready to give up, Rudolfo took hold of the ladder’s wooden dowels and tried to shake the guard loose.

Josh had two, maybe three yards to go.

The guard stopped climbing—he was halfway up now, and he just stood there, staring down at Rudolfo, and then he pulled out his gun.

The professor took a step up the ladder.

The guard’s finger teased the trigger.

Josh was almost at the entrance of the tunnel, and just as he screamed an agonized “no” in warning, the gun went off, causing an enormous explosion in the small tomb and drowning out his warning. Behind him, he heard a rumble and then the sound of heavy rain. No. Not rain. Rocks. Some parts of the tunnel’s walls were collapsing in on themselves. And in front of him, he saw the professor fall on his back on the hard, cold, ancient mosaic floor.

Chapter 7

T he man sat in the leather chair, his hands resting on the arm pads, his fingers circling the smooth nail heads. Around and around the cold metal circles as if this one movement was enough to keep him occupied forever. His eyes were shut. The gold drapes were drawn, and the room’s rich decor was cloaked in darkness.

He was satisfied to sit and do nothing but wait. Long pauses in the plan didn’t bother him. Not after all this time. From the moment he’d first heard the legend of the Memory Stones he knew that one day whatever power they held would be his. Needed to be his. No price was too high and no effort was too great to find out about the past.

His past.

His present.

And so, too, his future.

The idea that the stones might work, that they could, in fact, enable people to remember their previous lives, was unbearably pleasurable to him. He fantasized about the stones the way other men fantasized about women. His daydreams about what would happen once they were in his possession elevated his blood pressure, took away his breath and made him feel weak and strong at the same time in an utterly satisfying way. And because he’d been taught to be disciplined, he gave in to the temptation of dreaming about them only when he felt he deserved the indulgence.

He deserved it now.

Were they emeralds? Sapphires the color of the night skies? Lapis? Obsidian? Were they rough? Polished? What would they feel like? Small and smooth? Larger? Like glass? Would they be luminescent? Or dull, ordinary-looking things that didn’t begin to suggest their power?

He didn’t mind waiting, but it seemed to him that he should have heard by now.

He had an appointment he had to keep. No, it was premature to worry. He wouldn’t contemplate any kind of failure. He disliked that he’d involved other people in his plan. No one you hired, no matter how much you paid them, was entirely trustworthy. Regardless of how well he’d tried to plan for the mistakes that could happen along the way, he was certain to have overlooked at least a few. He felt a new wave of anxiety start to build deep in his chest and took several deep breaths.

Relax. You’ve reached this point. You’ll succeed.

But so much is at stake.

He picked up the well-worn book he’d been reading last night when his anticipation of what today would bring had kept him awake, Theosophy by the nineteenth-century philosopher Rudolf Steiner. There were always new books being published on the subject that mattered so much to him—he bought and read them all—but it was the thinkers of the past centuries whom he responded to and returned to so often: the poetry of Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Walt Whitman, Longfellow; the prose of Ralph Waldo Emerson, George Sand, Victor Hugo, Honoré de Balzac and so many more who engaged, reassured and aided him in amending and revising his own ever-evolving theories. They were his touchstones, these great minds that he could only know through their words. So many brilliant men and women who had believed what he believed.

He let the book fall open to the soft leather bookmark with his initials stamped on the cordovan in gold, at the beginning of a chapter titled “The Soul in the World of Souls after Death.” He’d underlined several paragraphs and he reread them now.

There follows after death a period for the human spirit in which the soul casts off its weakness for its physical existence in order then to behave in accordance with the laws of the world of the spirit and the soul alone, and to free the mind. It is to be expected that the longer the soul was bound to the physical the longer this period will last… .

His right hand returned to the brass buttons on the chair. The metal was cool to the touch. There was not much he’d ever lusted after the way he craved these stones. Once he had them, oh, the knowledge he would gain. The mysteries he would solve. The history he could learn. And more than that.

He read the next paragraph, in which Steiner described how great a pain the soul suffered through its loss of physical gratification and how that condition would continue until the soul had learned to stop longing for things that only a human body could experience.

What would it be like to reach the level of not longing? A pure level of thought, of experiencing the oneness of the universe? The ultimate goal of being reincarnated?

He looked up from the page and over at the phone, as if willing the call to come. It was a simple burglary: the professor was elderly. He would be there alone. It was just a matter of overpowering him and taking the box. A child could accomplish it. And if a child could do it, an expert could certainly do it. And he was only hiring experts at every step of the way. The most expensive experts money could buy. For a treasure, for this treasure, was any price too high?

There was no reason to worry. The call would come when the job was done. The round brass buttons were warm once more. He moved his fingers over to the next two, relieved by the cold metal on his skin, and returned to the book.

Having reached this highest degree of sympathy with the rest of the world of the soul, the soul will dissolve in it, will become one with it … .

If he had proof of past lives, actual reassurance of future lives, what would he do with the knowledge first? Not torture or punish; he had no desire to cause pain or sorrow. Find lost treasure? Discover truths that had been turned into lies through history? Yes, all that in time, but the first thing he would—

The sound startled him, although he was expecting it, and he jerked forward in the chair. As much as he wanted to, he didn’t pick up on the first ring. He put the bookmark back in the book and closed it. Listening to the second ring, he took a satisfying breath. He’d waited for this for so long.

Lifting the receiver, he held it up to his ear.

“Yes?”

“It’s done,” said the man in heavily accented Italian.

“You’ll proceed to the next step?”

“Yes.”

“Fine.”

He was ready to hang up, but the man spoke quickly. “There’s something I should tell you.”

He braced himself.

“We had a small accident, and—”

“No. Not on the phone. Report it through your contact.” He hung up and stood.

People were fools. He’d explained a dozen times how important it was that nothing revealing be discussed over the phone. Anyone could be listening. Besides, it didn’t matter if there’d been a small accident. Accidents happened, didn’t they? What mattered was that the stones were almost in his possession, at last.

Chapter 8

“Are you hurt?” Josh asked the professor.

“No, stunned, not hurt.”

He was on his back, lying on the mosaic floor, at the foot of the ladder.

“Here, let me help you. Are you sure he didn’t hit you?”

“It was so odd, looking up into the barrel of the gun, it was like looking into the night. Except a night as big as all the nights I’ve ever known. As big as all the nights Bella has slept all these sixteen hundred years.”

Rudolfo was having trouble straightening up; he was favoring one side of his body.

“Are you sure you are all right?”

He nodded. Concentrated. Frowned. And then looked down at his stomach.

The professor was wearing a dark blue shirt, and until that moment, in the low light inside the tomb, Josh had missed the spreading stain. But now they both saw it at the same time.

As carefully as he could, Josh pulled the professor’s shirt away from his body. The wound seeped blood. Snaking his fingers around Rudolfo’s back, he checked for an exit wound. He couldn’t find one. The bullet was still inside him.

Meanwhile, the professor kept talking. “Good timing for you,” he said. “If you hadn’t been in the tunnel you would be bleeding like a pig, too, eh?”

Except, Josh thought, if he’d been quicker, he might have prevented this. Hadn’t he thought this before?

“Bad timing for me,” the professor rambled. “I would have liked to have lived long enough to find out if what Gabriella and I have found … Find out if what Bella has been protecting all these years … is … is … as important as we think.”

“Nothing’s going to happen to you.” Josh put his fingers on the man’s wrist, looked at his own watch and counted.

“If I’d had a daughter …” the professor said, “she’d be just like her … tough as nails … with that one soft streak. She’s too much alone, though … all the time alone… .”

“Bella?” Josh asked, only half listening. The professor was losing blood too quickly; his pulse was too slow.

Rudolfo tried to laugh but only managed a grimace. “No. Gabby. This find … Her find … Something no one believed existed. But she was as cool as … What is your expression … Cool as … What is it?”

“Cool as? Oh. Cool as a cucumber.”

Rudolfo smiled faintly; he was visibly failing.

“Professor, I need to call for help. Do you have a phone?”

“Now we know … dangerous … what we found … . You’ll tell her, dangerous… .”

“Professor, do you have a phone? I need to call for help.”

“Did he take … all of the box, too?”

“The box?” Josh looked around and saw the pieces of it on the ground. “No. It’s still here. Professor, can you hear me? Do you have a phone? I need to call for help. We need to get you to a hospital.”

“The box … is here?” The idea seemed to buoy him.