Enticing Benedict Cole

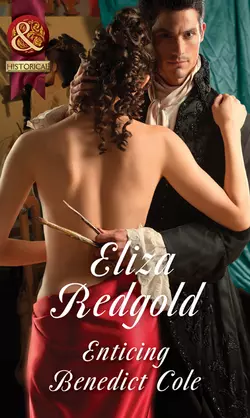

Enticing Benedict Cole

Eliza Redgold

AN ARTIST, A LADY, A SECRET PASSION…When Benedict Cole shuns her request for painting lessons, Lady ‘Cameo’ Catherine Mary St Clair takes matters into her own hands. She arrives at Benedict’s studio – only to be mistaken for a model! It’s an opportunity she just can’t turn down…Benedict knows better than to let intimacy interfere with his work, yet he can’t quell his fascination for the mysterious Cameo. And after one daring night together everything changes. Will Cameo still be his muse when Benedict discovers who she really is?

How she would continue to obey his curt instructions without a quick rejoinder she simply didn’t know.

Squarely she placed her feet in front of her and crossed them at the ankle, wishing for something to lean against. Still, the chaise longue was softer than his armchair, and she would allow no fault to be found with her posture.

‘That will do.’

As he rested on his heels her whole body stiffened under his scrutiny.

‘You need to remain still,’ he commanded her brusquely.

How could she be still with him staring at her? She dropped her shoulders and puffed out a slow breath.

‘Now turn to the right. No, not like that—turn some more.’

‘More?’

‘Now raise your eyes. Raise your eyes! Not move your whole head.’

‘I’m not sure what you mean!’ Cameo exclaimed, exasperated.

In a single swift movement he vaulted beside her and clasped her chin.

Author Note (#ulink_c4c60ffe-29f9-5395-862f-8a355eb05d81)

A portrait of passion …

Do you love the Victorian era? I do. It was an amazing time, when passion lurked beneath propriety and secrets and scandals were hidden beneath the surface. This story is inspired by the desperately romantic Pre-Raphaelite artists and models of Victorian England. The beautiful and sensual Pre-Raphaelite paintings are some of the most familiar artworks in the world today. I expect, like me, you have your favourites—do get in touch and let me know!

Just like Benedict Cole’s, the art and the love lives of the Pre-Raphaelite painters—a group of brilliant, free-thinking young men—were considered scandalous. Their artistic milieu was in complete contrast with the strict conventions of the Victorian upper classes. Ladies like ‘Cameo’, Lady Catherine Mary St Clair, lived in a controlled, stifling world, and often felt trapped and unhappy. It would have been considered unthinkable for a young aristocratic woman such as Cameo to want to pursue art seriously, and even more unthinkable to be an artist’s model.

This story celebrates every woman who ever challenged convention for the sake of art, and for the sake of love.

I hope you enjoy it!

Enticing Benedict Cole

Eliza Redgold

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

ELIZA REDGOLD is an author, academic and unashamed romantic. She was born in Scotland, is married to an Englishman, and currently lives in Australia. She loves to share stories with readers! Get in touch with Eliza via Twitter: @ElizaRedgold, on Facebook: facebook.com/ElizaRedgoldAuthor (http://www.facebook.com/ElizaRedgoldAuthor) and Pinterest: pinterest.com/elizaredgold (http://www.pinterest.com/elizaredgold). Or visit her at goodreads.com/author/show/7086012.Eliza_Redgold (http://goodreads.com/author/show/7086012.Eliza_Redgold) and elizaredgold.com (http://elizaredgold.com).

Enticing Benedict Coleis Eliza Redgold’s magical debut for Mills & Boon Historical Romance!

For Madeleine, who first listened to the whole story, and for my sister, the original Catherine Mary.

Many thanks to those who made Cameo’s acquaintance more than once in writing this story.

To the Wordwrights critique group, Janet Woods, Deb Bennetto, Karen Saayman and Anne Summers, who read early versions and made such valuable comments, and to Jenny Schwartz, an angel of a critique partner.

Thanks to my daughter, Jessica, who played Yann Tiersen’s Rue des Cascades on the piano as theme music while Cameo raced through the streets of London to find Benedict, and to my husband, James, who always makes London magical.

Contents

Cover (#u0bca2c40-ee69-559a-aaa4-407ef0b30db3)

Introduction (#u916876b7-0896-58ae-9fb0-c9ad2e3b344a)

Author Note (#ulink_5af1bcad-8c0c-5d71-b7a5-9dc421351c5b)

Title Page (#u5bbb8559-0c5a-571a-b57b-196785eef89c)

About the Author (#u1f3c5b72-51e6-5715-a7c1-4e0183584e2a)

Dedication (#u62aba978-96c4-530a-a560-82ed332a52d3)

Acknowledgments (#u7e850cd7-9a73-5099-a5a3-975e52c3cf6a)

Prologue (#ulink_aa6f7260-282e-5850-9bc4-035407a8d295)

Chapter One (#ulink_bb74a4a3-2977-5692-a87e-38e2e58bbdd5)

Chapter Two (#ulink_09955f87-9407-5c7d-8d42-0859d668cdc3)

Chapter Three (#ulink_8fab1755-1865-540a-b0d2-7125d8351380)

Chapter Four (#ulink_42368c2c-6306-560a-a199-377b92455a3c)

Chapter Five (#ulink_a02c137a-76df-5af7-8dcf-23f8610dca11)

Chapter Six (#ulink_75042c63-c914-5f58-877c-eaf9e51c4be8)

Chapter Seven (#ulink_8f4d6dc8-6ffd-5d69-93bf-9eb35318317b)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Historical Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#ulink_68f8f6f6-760b-5c9b-876c-ab1e30c6b907)

‘Love, A more ideal Artist he than all.’

—Alfred, Lord Tennyson:

‘The Gardener’s Daughter’ (1842)

‘On that veil’d picture—veil’d, for what it holds

May not be dwelt on by the common day.

This prelude has prepared thee.’

—Alfred, Lord Tennyson:

‘The Gardener’s Daughter’

London 1852

Cameo pressed the letter to her lips.

Beneath her carefully crafted, polite phrases would he read her hopes and dreams in each line?

Through the open window she stared out past the silhouette of the ash tree into the starry night beyond, as if by will she summoned him to reply. Beyond, by the light of the moon, she made out in front of the house the darkened grassy garden of the square with its plane trees, the high black wrought-iron railings encircling the snowdrops and daffodils. She felt caged in the house, like a bird who longed to be free. She wanted to be out in the world, to be part of it all. To learn. To paint. To live.

With a sigh she closed the velvet curtains and retreated into her bedroom. On her dressing table the candle flickered. The flame leapt high, with its orange, red and yellow tongue, its vivid blue centre. If only she could learn to capture such passionate colours with her paints!

He did.

Benedict Cole.

That was his name. She’d stared at it, scrawled in black paint at the corner of the canvas.

She’d discovered his passion and power when she’d seen his painting at the Royal Academy of Art. It had stopped her in her tracks, her breath shuddering.

The work was marvellous. The subject was simple, a woman holding sheaves of wheat. But the subject of the painting wasn’t what caught her attention. It was the strokes of his brush.

As if his paintbrush stroked her skin.

As if it touched her heart.

There was a secret in that painting, as if it held a message, as if it spoke directly to her. She...recognised it. That was it. Somehow, she understood the soul of the artist who had painted that picture. The effect on her had been extraordinary. She wanted to stand in front of it for hours, soaking in the colours, the textures, his use of light. She returned again and again to view it.

Benedict Cole must teach her. She knew it. She needed to learn everything he knew. Only he could free her hands and the emotions locked inside her. Only he could show her how to put them on paper, on canvas, with charcoal, with paint, until the work came to life.

She must find a way.

Now at last she’d gathered up her courage to write to him.

She yearned to pour out all her hopes and dreams in the letter, her longings and desires. But her phrases remained stilted. Draft after draft, pen staining her fingers, she’d tried to find the right words to ask his consent to give her lessons and that she would pay him handsomely for his time.

And she hoped that he would understand. It meant so much more.

Her heart beating fast, she picked up the letter.

Sealing it with a drop of wax, she blew out the candle.

She could only pray for his answer.

Chapter One (#ulink_bde32448-8cec-50a4-b48d-51955bfd550b)

‘This morning is the morning of the day.’

—Alfred, Lord Tennyson:

‘The Gardener’s Daughter’

‘The answer is no!’ Gerald St Clair, Earl of Buxton, threw his newspaper down on the breakfast table. ‘Don’t ask me again, Cameo!’

Cameo leaned forward. She clutched the carved stone of her necklace so hard it dug into her skin. ‘Please, Papa, please.’

The earl shook his head, his whiskers quivering. ‘I’ve had quite enough of this. You’re Lady Catherine Mary St Clair. You have a place in society to uphold. All this nonsense must stop immediately. No daughter of mine is going to be an artist.’

She took a deep breath. ‘Being an artist isn’t so unsuitable. I’m asking for some proper painting lessons, that’s all.’

The vein on the earl’s forehead popped out. ‘It’s quite ridiculous. I blame myself. I should never have allowed you take up art in the first place. It’s all you talk of, all you do.’

And all she thought of, Cameo reflected guiltily. At that very moment she wished she had her sketchbook and pencil with her, to make a study of her father’s irate expression.

‘Listen to me, Cameo. Painting may remain your hobby, but nothing more. I’ve been too lenient with you, I see that now. It’s time to think of your future.’ Her father’s gruff tone had softened. She knew how much he loved her and he always sounded particularly gruff when he was trying to protect her from the outside world. But she didn’t want to be protected. Not from the world. Not from art.

‘I am thinking of my future, Papa.’ She took another huge breath. ‘My future is as a painter.’

The earl choked on his bacon and kidneys. ‘Your future is marriage.’

From the other end of the long, polished table Lady Buxton spoke in her soft voice. ‘You’ll forget all about painting lessons when you’re married, Cameo dear. Take our Queen Victoria. She and Prince Albert are an example to all those who seek the happy estate. Even though she is queen, she believes the best place for women is home and family.’

Cameo turned to her mother, sat behind the silver coffee pot. ‘I’m not against a home and family, Mama. It’s just I’ve discovered there’s more to life. There’s art. Art is real life.’

‘Art! Real life!’ blustered Lord Buxton. ‘You’ll put off your suitors with all this nonsense.’

‘Lord Warley asked especially if you were to attend Lady Russell’s ball,’ the countess chimed in with a smile. ‘He’s such a lovely young man. So well mannered.’

Cameo shuddered, as if Lord Warley had taken her hand to bow. Even the slightest touch of Robert Ackland, Earl of Warley, always turned her stomach. He came from a similar background to hers. Their fathers held the same rank in society. But couldn’t her mama sense what lay beneath Lord Warley’s good manners? Perhaps because Cameo spent so much time sketching, always trying to capture character, she had become more attuned to what was hidden behind propriety. ‘Oh, no, Mama. Not Lord Warley. Never.’

‘Our family has been friends with their family for years,’ her papa reminded her. ‘I was very fond of my old friend Henry Ackland. I don’t know his son well and he doesn’t seem much like his father, but Henry was a good man, God rest his soul.’

Her father still missed his old friend. Cameo gentled her voice. ‘I don’t want to think about suitors yet, Papa, that’s all. Please. I long to learn to paint in the new style, like the Pre-Raphaelites.’

‘The Pre-Raphaelites,’ her mother repeated in a horrified whisper. ‘The way they carry on is shocking, I’ve heard.’

‘But the new style of painting is wonderful. Why, I saw an extraordinary work in the Royal Academy of Art.’ Cameo’s heart beat faster as she recalled it. ‘If I took lessons, perhaps I could learn to paint like that. I’ll never be that good, but one day, I might be able to exhibit.’

Her mama almost dropped her coffee cup. ‘You couldn’t possibly show your paintings in public. What would people say? Perhaps you could paint some flowers on the name cards for our dinner parties this Season instead,’ she added hopefully. ‘That would be lovely.’

‘I suppose George could have art lessons if he wanted them?’ The question burst out before Cameo could halt it. She gripped her hands together.

‘It’s different for your brother.’ Her mother put her fingertips to her temples. ‘And please don’t raise your voice.’

Her father glowered. ‘Stop upsetting your mama and stop these foolish ideas. I’ve let it go far enough. I ought not to have allowed it in the first place.’

‘Papa...’

‘Enough, I said. I won’t discuss this matter with you again. Why are you arguing in such a manner? It isn’t like you, Cameo. Now, behave like a young lady.’

I’d rather behave like an artist. Cameo choked back the words.

‘I’m sorry, Papa.’

With shaking fingers she picked up her cup.

She hated to deceive her parents, but she had no choice.

Alas. It was already too late.

* * *

‘Cameo?’ Maud poked her head around the drawing-room door. ‘Briggs told me you were in here. Am I interrupting?’

‘Not at all.’ Cameo laid down her paintbrush. No matter how hard she tried there was no discernible improvement in her work. ‘It’s lovely to see you, Maud. It isn’t going well this morning.’

Cameo stood at her easel, an old linen sheet spread beneath her. She was fortunate to be allowed to continue to paint in the drawing room, after an incident with some spilt paint. Of course, it had been ochre.

Her easel was placed where the light was best. Through the windows the March sun cast its spring promise. Cameo had asked her mama if she might fling wide the heavy curtains for more light, but at her mother’s shocked face the question had trailed away.

Now Maud peeped over her shoulder. ‘What are you working on today?’

Carefully Cameo wiped her hands with a rag. She’d promised her mama to try to keep her hands clean, too, after she’d appeared at luncheon with oil paint under her fingernails.

‘I’m doing what apprentices used to do when they worked in the studios of the Old Masters,’ she explained. ‘They copied the Masters’ work to learn their technique. It’s a good way to learn, though not as good as actually watching a master at work with his own hands. I’m not up to landscapes yet so I’m making a copy of that portrait.’

She pointed to the gold-framed portrait that hung above the fireplace. It depicted her grandmother as a young woman. She wore a white dress and a cameo necklace tied with a black-velvet ribbon, the same black-and-white stone that now hung around Cameo’s neck. Set in gold, with a loop as well as a pin, it could be worn as either a brooch or a necklace.

‘You’re so like your grandmama,’ her mother often said. Her grandmama’s hair had been dark, almost black, and her eyes, though difficult to discern in the portrait, were the same deep blue as Cameo’s, so deep they could appear purple. Violet eyes, her mama called them.

Maud glanced from one painting to the other. ‘Your painting will be just as good,’ she said loyally.

Cameo slipped off her paint-splattered artist’s smock. ‘You’re being much too kind, Maud, and you know it. I’ve got so much to learn, but how can I improve when there is always a luncheon or a dinner or a ball we must attend? And we have to keep changing our clothes. Imagine how wonderful it would be to get up in the morning and be able to paint all day.’

Cameo sighed. She tried to keep her spirits high, but it was difficult. More often now, at night, she despaired. Sometimes she lay awake in bed until she threw back the covers, lit a candle and seized her pencil. Then she drew and drew, sheet after sheet, until dawn came. It was the only way to soothe her sense of being trapped, her frustration. Yet she was forced to play at art, to keep it as a hobby, never learning, barely improving. Without lessons, without a guiding hand, she would never become the artist she longed to be.

Maud’s round blue eyes were sympathetic. ‘Do you really want art lessons so much?’

‘So much that I had the most terrible argument with Papa and Mama.’ She paced the room, her gown trailing across the carpet. Impatiently she hitched it up. ‘I must take matters into my own hands. I’ve got a few ideas.’

‘Oh, no, Cameo.’ Maud’s curls bobbed in alarm. ‘Your ideas are always so reckless. Surely you must obey your parents’ wishes.’

Maud would never do anything of which her parents disapproved.

‘Art is everything to me,’ Cameo said. ‘I will even pay for lessons myself.’

Maud appeared bewildered. ‘But how would you pay?’

In spite of the luxuries that surrounded her, Cameo had only a little money of her own. All her needs were provided for and she was made a small allowance, but that was all.

Her fingers touched her throat. ‘I could sell some of my jewellery.’

Maud’s hand flew to her mouth. ‘Not your cameo necklace.’

Cameo smiled. ‘I’ve worn it ever since Mama gave it to me. Just as I’ve worn the name George gave me when I was born.’

‘Cam-mee, because he couldn’t say Catherine Mary.’ The dimple that displayed whenever George was mentioned appeared in Maud’s cheek. ‘And it became Cameo.’

Cameo’s fingers ran over the black-and-white jewel with the woman’s profile carved on to its face. She shook her head firmly. ‘No. I could never sell my cameo necklace.’

But she would do almost anything for painting lessons.

Benedict Cole would understand. She felt convinced of it. No one in her family or any one of her friends, not even Maud, understood her longing, her need to paint. To try to speak of it, to explain to those who didn’t share her passion, was like speaking a foreign language.

In Benedict Cole’s painting at the Academy she’d discerned a flame that burned inside the artist’s heart, which drove him on to create, no matter what the cost, no matter what the risk. She couldn’t describe it but she knew it was there, that flame.

It burned inside her, too.

* * *

After Maud left, Briggs, the butler, entered the drawing room, with a white paper square held aloft on a silver tray. ‘This has come for you, Lady Catherine Mary.’

‘At last!’ Cameo leapt up and reached for the envelope. Her name and address was written on it in strong black letters. ‘Thank you, Briggs. And—no one saw?’

The merest glimmer of a smile showed on the butler’s impassive face. She only ever saw him grin widely at Christmas, when each year she gave him a picture she had painted especially for him, as she’d done since she was a small girl, the results improving somewhat over the years. One could not call the butler family, yet to Cameo he was. All the servants were old friends and allies, people she could trust with her secrets.

‘His lordship has gone to Westminster and her ladyship is resting upstairs.’ Briggs gave a slight bow and discreetly closed the door.

Cameo’s fingers trembled with such excitement she could barely open the seal. At last, to be able to work with a true artist, someone who would understand. Eagerly, she began to read.

Dear Lady Catherine Mary St Clair

In response to your letter regarding painting lessons, I regret to inform you I will not be able to fulfil your request. I have neither the time nor inclination to teach aristocratic society ladies to dabble at art.

Benedict Cole

‘Oh!’ She gasped as if a pail of cold water had been thrown over her.

Tears smarted in her eyes. If he knew how hard she’d tried to learn, to teach herself. How hard she’d fought for lessons, of her desperation, her despair. No, he dismissed her, just as everyone else did.

Her heart sank as she crumpled onto the sofa. She’d convinced herself Benedict Cole was the guiding hand she so desperately needed. She dropped her head in her hands, wiped away another tear. Her hands clenched. She might as well give up.

Just the thought of giving up sparked the flame.

Cameo’s temper burst into life. Fury burned within her as hot as the coals in the grate. How dared he. Dabble at art. The nerve of the man. How dare he presume that simply because of her title she wasn’t serious about art? It was insulting.

Jumping to her feet, she crossed to the oval gilt-framed mirror by the door and surveyed her reflection. How could she convince him?

Off came her pearl earrings and the diamond-studded watch pinned to her bodice. She must appear a serious student of art to make him understand, not the kind of society lady about whom he made such infuriating assumptions. She straightened the white-lace collar and cuffs of her grey morning dress and smoothed down her hair with a nod. Yes, that would do.

For a moment she hesitated. Could she, Lady Catherine Mary St Clair, go to a painter’s studio unannounced when they hadn’t been formally introduced? Her mama would be horrified.

The spark surged inside her.

It wouldn’t be a social call.

Benedict Cole must teach her to paint. Somehow, she would change the artist’s mind.

* * *

The carriage rattled to a stop.

Cameo’s fury and determination had built with every turn of the carriage wheel. As they rolled out of the quiet, leafy square in Mayfair, with its large cream houses, glossy black-painted doors, marble steps and iron railings, onto Oxford St and the roaring bustle of the shops and crowds, all she could think about was Benedict Cole. She longed to confront him. How could he make such assumptions about her, the kind she’d been fighting against all her life? If he knew...if she told him...

She leapt up so fast she almost hit her head on the carriage.

Out on the street, Bert, the coachman, had opened the door and put the box down for her. ‘Here we are.’ He rubbed his forehead and glanced about dubiously. ‘Are you sure this is the place you’re wanting?’

Briskly, she stepped down into the street and adjusted her skirt. No turning back now. ‘Yes, this is it. Will you mind waiting for me, Bert?’

‘I’ll be here.’ He grinned good-naturedly. ‘Anything for you, Lady Catherine Mary.’

Tying her bonnet with a firm bow, she set off against the wind. In spite of spending much of her life in London, there were parts of the city she barely knew. She certainly never stopped in Soho. The family carriage always drove through. She had expected the soot and dirt, certainly, but not the vibrant activity sweeping her along the cobbled road. Spread with straw and litter, the busy street echoed with the sounds of carriages and carts, horses’ hooves, and vendors shouting their wares. There were shops, too, with people going in and out, tinkling the doorbells. The smell from the fishmonger’s window, full of shoals of mussels and oysters, reached her before she saw it and a yeasty odour emanated from empty barrels outside a public house, a sign with a lamb painted on it swaying above the door.

Through the crowd she hurried, past two fighting boys, their mothers with baskets on their arms chatting to each other uncaring of the scuffle, and past a flower seller who offered with a toothless grin to sell her a bunch of daisies. A young woman in a low-cut bodice standing on a corner sent her a brazen glare. With a gulp Cameo hastened on.

In front of a tall red-brick building she checked the number. Yes, this was the address of the infuriating Benedict Cole, yet in front of her stood a bakery, the scent of hot bread and buns wafting out every time a customer opened the door. The artist must live upstairs, but there was no obvious way to get in.

A girl sat on the pavement nearby, shabby and meek, with bare feet and a shawl around her thin shoulders.

‘Matches,’ she called hoarsely, ‘matches.’

Cameo crouched down and smiled. ‘Hello.’

‘Hello, miss.’

‘What’s your name?’

‘It’s Becky, miss. Do you want some matches?’

‘I don’t have any money with me.’ Why hadn’t she brought her reticule with her? She normally did, for she kept a tiny sketchbook and sharpened pencils inside, but she’d rushed out in such a hurry. ‘I’ll bring you some another day, I promise.’

The girl sighed. ‘That’s all right.’

‘I will, Becky. Perhaps now you can help me. Do you know how to get in to where the people live upstairs?’

‘You go round the back, miss, down that alleyway. There’s a red door.’

‘Thank you,’ Cameo called, already moving away.

A cat yowled as she entered the dingy alley. For a moment she hesitated before she picked her way through the sodden newspaper, broken glass bottles, cabbage stalks and something that looked like—no; it couldn’t be. Edging around the rubbish, she narrowly avoided a puddle of something that looked and smelled worse.

The red door, if the flakes of peeling paint identified it as such, was ajar. At her touch it swung open wider, creaking.

Inside the cramped entrance hall, she stared, half fascinated, half appalled. She’d never visited such a rundown establishment. The walls had been white once, perhaps, but now they were an indeterminate colour, yellow or cream, with water marks at the bottom, where the damp had crept in. A staircase with a worn green runner lay directly in front of her, the woodwork scuffed and dull.

Dust dirtied her white-kid gloves as she gripped the banister. She brushed them on her skirt. Up two narrow flights of steps she climbed, passing closed doors on each landing, checking numbers as she went and up a third flight, which was narrower still.

Out of breath, she reached the attic door at the top. It bore no number, just a name plate beside it, simple and beautiful. She hadn’t expected something so unique. Carved from a piece of oak, a pattern of leaves and berries had been etched on to its square edges, and at the centre scrolled the name: Benedict Cole.

Well, now, Benedict Cole. You’re about to receive a surprise visit from a society lady.

Her heart drummed as she rapped on the door. No reply.

Under her skirts she tapped her foot. She knocked again, harder.

The door flung open. Cameo gasped and fell backwards at the sheer force of the man who glowered in front of her, his fist gripping a paintbrush. Benedict Cole. She knew it with a certainty flaming inside her belly. Tall, with dark hair that swooped over his forehead, he wore a loose, unbuttoned painting shirt covered with blotches of dried oils in a frenzy of colours. Yet his eyes held her attention. Dark brown, under heavy black brows, they blazed with a fierce inner light that seared into her very soul.

‘You’re too late.’ His educated accent held an unexpected warm burr.

With a huge gulp of air she tried to steady her ragged breathing. ‘Too late?’

‘I’m too busy to see you now.’ He started to close the door.

‘Wait! I must see you. You are Benedict Cole?’

He scowled. ‘Who else would be working in my studio?’

‘Please. Just give me a few minutes of your time.’

Eyebrows drawn together, he studied her. ‘You’ve seen the notice.’

‘The notice...?’

‘Will you please stop repeating every word I say? Are you dim-witted as well as unpunctual? Yes, my notice seeking a new model. I have a major new work in mind.’

‘You’re looking for a model. For your painting.’

‘How many times do we have to have this conversation? If you’re not here to be considered, then why exactly are you here wasting my time?’

In a flash, she realised what had happened. ‘Well, actually...’

‘Well, actually what?’ he mimicked, the corner of his mouth lifting in a sneer.

How dare this man speak to her in such a manner? In person he was just as rude as in his letter, even ruder if that were possible. Cameo opened her mouth to tell him of his mistake in no uncertain terms and then snapped it shut again.

Her mind whirred. He’d made it clear he didn’t wish to provide painting lessons to Lady Catherine Mary St Clair. Now, upon seeing him, he appeared to be the kind of man who would never change his mind.

Cameo smiled. ‘I’m so sorry I’m late, Mr Cole. You’re quite right. I’ve come to be your model.’

Chapter Two (#ulink_8307050d-f57e-578b-b7fc-13dc7afa81d6)

‘As never pencil drew. Half light, half shade,

She stood.’

—Alfred, Lord Tennyson:

‘The Gardener’s Daughter’

‘We’ll see about that.’ Benedict Cole arched his eyebrow. ‘You’d better come in and let me look at you.’

Leaving the door ajar, he turned away. ‘Are you coming in or not?’

Cameo followed him into the studio. Was it necessary for him to be so abrupt? He turned his back on her, something that was never done in society. Yet her irritation vanished as she surveyed her surroundings. Why, the studio was exactly the kind of space she had always wished she might have one day. The light that flooded in from the windows was so much better than in the drawing room at home. It glinted on the tools of the painter’s trade scattered everywhere: papers, pots of oil paints, rags, bottles and brushes, and canvases propped against the walls. A huge easel, much stronger than her slender folding one, dominated the room. There were no fine carpets to worry about here, just wooden floorboards, scratched and worn.

Her eyes closed. She savoured the smell of oil paint and turpentine permeating the studio. No perfume had ever smelled so sweet. Upon opening her eyes, she encountered the artist’s stare.

‘Are you quite well?’

A flush heated her cheeks. ‘I like the smell of oil paints and turpentine, that’s all.’

‘That’s unusual. Many models complain about it. They say it makes them feel ill.’

‘How could anyone not like the smell of paints?’

‘It’s a point in your favour.’ He threw aside his paintbrush and beckoned. ‘Come over by the window.’

‘Why?’

‘Why do you think? I need to see you in a proper light.’

To her surprise her hands trembled beneath her gloves. She walked over to the window on legs that were also unsteady.

‘Take off your coat and your bonnet.’ His impatience was barely concealed. ‘I need to see your face.’

With effort she bit down the sprightly retort that sprang to her lips. Removing her pearl-tipped hat pin, she dropped her bonnet along with her grey woollen coat on to a faded brocade chaise longue pushed up under the window.

He gave a sharp intake of breath.

‘Is this what you...?’

‘Be quiet,’ he snapped. ‘I need to look at you, not listen to you.’

He must be the most insufferable man she had ever met. No one had ever spoken to her in such a way. Cameo fumed as he stared at her with increasing intensity.

‘Take down your hair.’

Her gloved hands flew protectively to her head.

He responded with an impatient shake of his own. ‘How can I see you as you should be when your hair is in that, how can I put it...’ He gave a dismissive wave. ‘Overdone style? I must see it loose. The painting will require it.’

An overdone style. Her mama’s French maid had done it in the latest fashion, with ringlets down both sides, that morning.

‘What’s the matter now? Did you come here as a model or not?’

His words renewed her purpose. One by one, she took the pins from her hair and dropped them on to the chaise longue, sensing Benedict Cole behind her watching each move. She slipped out the last hairpin. Curls whispered at her neck as strands of long, black curls loosened from their ringlets and loops, tumbling about her shoulders, foaming down her back.

Twirling towards him she met his dark eyes. She couldn’t break his gaze even if she wanted to.

At last he spoke. His voice had become husky. ‘This is extraordinary. I’ve been thinking of a painting for many months now. I imagined a woman with hair and eyes in exactly your colour. I began to think I may never find her and that perhaps I imagined such shades. You’re precisely the model I’m looking for.’

Cameo clasped her fingers together as a thrill raced through her. ‘You want me in your painting? Me?’

As if she were no longer in the room, he turned away. She heard him mutter to himself, ‘Yes, I can do it.’

‘Do what?’

He spun around with a scowl. ‘You must keep silent if you model for me.’

‘I will keep silent when I’m modelling, but I’m not modelling now.’ She reached to pick up her bonnet. ‘Nor do I wish to do so if you’re going to be quite so rude.’

‘Wait.’ He made an apologetic gesture and sent her an unexpected smile. ‘You’ll have to forgive the moods of an artist. I’m not one for social niceties when I’m painting. You need to understand that.’

‘I do understand that,’ Cameo retorted. ‘But you have to understand. If I am to be your model, I will require them.’

‘You require social niceties?’ He studied her for a long moment with an expression impossible to fathom. He moved over to the fireplace and indicated a chair. ‘Come and sit down. There are a few questions I need to ask you.’

Cameo’s stomach lurched. She’d almost given herself away. Her temper mustn’t get the better of her.

This was her only chance.

Trying to appear subdued, she followed Benedict Cole to the fireplace. Papers and books lay on each available surface, even on the armchair.

‘Just move those,’ he said irritably.

She placed the pile of books on a gateleg table and sat. Horsehair poked out in tufts on the arms of the chair and, judging by the hard feel of it beneath her, there wasn’t much left in the seat either.

With one hand, he dragged a straight wooden chair opposite her after dropping more papers on the floor with an easy, casual gesture. No wonder his studio was so untidy. It was unimportant to him. His surroundings took second place to his work, while she spent most of her painting time spreading sheets and tidying away.

His face was half-shadowed and he didn’t speak for a long moment. Unnerving enough when he stood staring at her, now he was seated, his closeness became even more alarming.

Cameo’s heartbeat quickened.

‘So you want to be an artist’s model?’

‘Ah, yes.’

He gave her another of his long-considering examinations. ‘Forgive me. You’re different from the other girls I’ve seen who want to be models.’

He suspected her already, she realised with dismay. ‘Different? In what way?’

‘Your voice suggests you’ve been raised a lady,’ he said bluntly. ‘As does your request for social niceties. As do your clothes.’

‘I wore my best to see you.’ With trembling fingers she smoothed her foulard skirt, a mix of silk and cotton. Did she dare try to put on an accent? No. She’d never make it work and it seemed horrid, too. ‘This is my finest gown.’

His dark eyes narrowed. ‘Tell me, why is it you’re seeking employment?’

‘I have little choice in seeking employment.’ She put her hand to her forehead. ‘I’ve fallen on hard times.’

‘Have you indeed?’

‘Yes. I’m alone in the world and I have few options for an income.’

Crossing one long trousered leg over the other, he leaned back. ‘Tell me more about yourself. First, what’s your name?’

There was no way she could supply her real name. She cast a quick look down at her dress. The colour? Too obvious. ‘My name is Ashe. Miss Ashe. With an e.’

‘With an e,’ he drawled. ‘And your first name, if I may enquire?’

Surely it was safe enough to use her nickname. ‘It’s Cameo.’

His head reared. ‘Cameo? I’ve never heard of a girl named Cameo before.’

‘I was a foundling.’ She pointed to her necklace. ‘I was found with this necklace, so I was called Cameo.’

His intent gaze fell to the neck of her dress, where the stone nestled. He seemed to take in more than her necklace. ‘It’s a fine piece.’

Her cheeks burned. ‘Yes. It is very fine.’

‘You say you were found with it. Your mother must have been a person of quality.’

‘My mother may have been of quality. She may have been a lady.’ Cameo found she was quite enjoying making up a new life story, her indignation driving her imagination. ‘Though perhaps my father was a gentleman, perhaps he gave her the necklace. It’s often a gentleman who takes advantage of a poor, innocent girl.’

He arched a winged eyebrow. ‘Is it?’

‘I believe so.’

As he leaned over, a strong masculine scent mixed with turpentine and paint reached her. ‘Some people invite trouble, don’t you think?’

The horsehair prickled through her dress as she shifted away from him. Suddenly she became aware of the danger of being alone in a room with a man to whom she hadn’t been introduced. Her mama would have fainted away. ‘I don’t know what you mean, sir.’

‘Cameo.’ He lingered on the word. ‘The word is Greek. Tell me more about your necklace.’

‘There’s little else I know about it. Though I’m sure it was a tragedy. I have a strong feeling my mother never left me willingly. I think she was forced to give me up. Perhaps my wicked father gave her this necklace and she left it with me as a keepsake or perhaps, as you say, she was of quality and owned it herself. In any case, it was found with me.’

‘Where?’

‘In my swaddling clothes.’

‘No, where were you found?’

The question floored her, but only for a moment. ‘There’s a place near Coram Fields in Bloomsbury. Foundlings have long been left there.’ Luckily her mama had given money to help the unfortunate foundlings only a few months before.

Still he seemed suspicious. ‘And who found you?’

‘Nuns,’ Cameo replied wildly. ‘Nuns found me. Then a kind genteel lady took me in and raised me as her own.’

‘And her name was?’

‘A Mrs...’ From her sleeve she edged out her lace handkerchief to play for time. ‘Cotton. That was her name. Poor Mrs Cotton. She had no family of her own, so she took me in. As I grew up I became her companion.’ With a corner of the handkerchief she dabbed at her eyes. ‘It’s sad. She died close to a year ago. After that I was all alone. It is thus you find me, seeking employment.’

He crossed his arms. ‘It’s a strange story.’

‘Not so strange. There are many others who have found themselves in my sorry position. I cast myself upon your mercy, sir,’ she added, with a dramatic flourish.

A smile seemed to play at the corner of his lips and then vanished. ‘So you’re at my mercy, is that right?’

The sense of danger came back as she swallowed hard. ‘Yes.’

He stood and dropped a log on to the fire. With a blackened poker he made sparks fly. Turning back, he leaned casually against the chimney piece and crossed his long legs, the poker still in his grip. ‘There’s other, more suitable employment than being a model. You might work in a shop or be a governess or be a companion to another lady.’

The thought of Lady Catherine Mary St Clair working in a shop made her duck her head to hide a smile. ‘That’s true. And it may come to that now Mrs Cotton is gone.’ She dabbed at her eyes again with her handkerchief for effect.

Deftly he dropped the poker into a brass pot on the hearth. ‘Being an artist’s model is not the most respectable occupation, Miss Ashe. Not all the girls are from such a genteel background as yours, raised as you were by the good Mrs Cotton.’

‘What’s the usual background of models?’

‘They’re generally girls who work in shops and factories. Have you heard of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood?’

Had she heard of them? ‘Yes, I’ve heard of them... I mean, I think so.’

‘One of the Brotherhood, John Everett Millais, has recently been painting Shakespeare’s Ophelia. The model for his painting is called Lizzie Siddal and she was discovered working in a hat shop. She’s going to be married to another member of the Brotherhood, Dante Gabriel Rossetti.’

‘I didn’t know that.’

‘Not many do. But the artist-and-model relationship is one that often becomes...intimate.’

Cameo’s cheeks tinted yet again. How she wished she might stop blushing in this man’s presence.

‘Lizzie had to lie in water for hours on end in the painting to show Ophelia drowning and she nearly died. Modelling can be dangerous.’

‘I’m not afraid of danger.’ If only he knew. Just by being here she risked everything.

His brow lifted. ‘Is that right?’

‘Where else do artists’ models come from?’ she asked quickly to change the subject.

‘In the past it’s not been unknown for models to have come from the streets.’ An alarming glint sparked in his eyes. ‘As I said, modelling is not the most reputable occupation. Fallen women, kept women, mistresses, whatever you wish to call them—many have modelled for paintings.’

Cameo gripped her gloves together. She refused to reveal to Benedict Cole that his mention of mistresses and kept women shocked her, even if she never openly discussed such scandalous topics. ‘I’m merely an admirer of art. That’s why I seek employment as a model. Many a wet afternoon have I spent looking at paintings in a gallery.’ No need to mention that the gallery where she’d spent most time recently was the Royal Academy, where she’d been spellbound by his work.

‘I’m not sure you’re being entirely honest with me, Miss Ashe. But...’

Her breath caught in her throat.

‘But you’re ideal for my next painting. You’re hired.’

She exhaled. ‘Thank you.’

‘I’m not sure you’ll thank me when we’re working,’ he warned. ‘Being a model is not the easy job many young women think it will be. I shall require you to sit without moving for hours at a time, every day. Do you think you can do that?’

‘Yes, of course.’ Wasn’t half her life spent sitting bored at dining tables and in drawing rooms? ‘I’ll have no trouble with that.’

‘I’ve already completed a lot of the background work so I don’t need you for that. The work is partly complete.’ The wooden chair scraped across the floor as Benedict sat by the fire again and pushed his dark hair from his brow. ‘Do you have any questions for me?’

‘I don’t think so.’

‘Then you’re unusual. You haven’t asked the question most models ask the minute they walk in the door.’

‘And what is that?’

‘Payment, Miss Ashe,’ he drawled. ‘Most models are interested in how much they will be paid. Since you’re experiencing such—how did you put it?—hard times, I expected payment to be of the utmost importance to you.’

Beneath her layers of petticoats she gave herself a kick. ‘Oh.’

‘Perhaps it is your preference for social niceties preventing you making mention of the sordid topic of coin? Will a shilling each session be satisfactory?’

‘Is that the customary rate?’ she asked boldly.

His mouth curved. ‘I’m not trying to cheat you.’

‘Then that will be perfectly satisfactory.’

‘You’re most trusting, Miss Ashe.’

She dragged her attention away from him and his sardonic expression. ‘I do have a question. The painting’s subject—what is it?’

‘That’s a question I can’t fully answer now. I can only tell you it’s based on a poem by Alfred Tennyson. You know the poet’s work, perhaps.’

‘Mrs Cotton was fond of his work, as our dear Queen Victoria is,’ she replied, as her mind went immediately to the fine leather-bound volume of the poet’s work she kept on her bedside table. She had read the poems over and over again, revelling in the romance and passion, wishing she could make her paintings speak in such a way.

‘Many painters today are drawing on Tennyson’s work for inspiration. I must warn you, the painting may not be what you expect.’ He allowed a silence to fall between them for a moment. ‘How can I put this in a way to suit your delicate sensibilities...?’

Her skin rippled as his all-encompassing artist’s stare lingered over her. ‘Let me just say the painting will be somewhat—revealing.’

‘I’m not sure what you mean, Mr Cole.’

‘The painting will not be like your cameo. That is a profile of a woman’s face. But my painting will not merely be of your face. What I have in mind will require I make a study of...your form.’ Once again his gaze wandered over her.

‘I see.’ Her stomach gave another of those mysterious lurches. ‘To what extent will my...form...be displayed?’

‘You need have no fear.’ A smile flickered at the corners of his strong mouth. ‘I will produce a work acceptable to common standards of decency and at this stage it’s a private project. In the painting, you will appear in a simple white gown. But in order to paint you as I wish, you may need to show parts of yourself which ordinarily you do not. But even among artists, I can assure you, there are proprieties we observe.’

‘I’m no prude, Mr Cole.’ She gulped. ‘I will model to your requirements, assuming all the necessary proprieties are observed.’

‘Of course. I wouldn’t consider proceeding otherwise. Then we are agreed. Can you come tomorrow?’

‘Yes.’ Somehow, she’d find a way.

‘Come in the morning at nine o’clock. The sun will be at the right angle.’ He stood, ending the interview.

‘Thank you for calling,’ he added, with a somewhat teasing politeness.

Cameo got to her feet and replied coldly, ‘Thank you very much, Mr Cole. I will see you tomorrow.’

‘Miss Ashe. I think you’ve forgotten something.’ His voice halted her as she picked up her coat and bonnet. ‘Your hair.’

Why, she’d been sitting there the whole time in the company of a strange man with her hair down! Frantically she found the hairpins she’d dropped on to the chaise longue and began to pin up her heavy mass of hair. How could she restore it to her previous style, without the help of her mama’s maid? After a few attempts, she gave up. With a few hairpins, she coiled it into a spiral at the back of her head and pinned it in place. He made no comment, but she knew Benedict Cole missed nothing of her clumsy work.

She seized her bonnet and coat. ‘Well, goodbye.’

He gave a mocking bow. ‘Until tomorrow, Miss Ashe.’

Chapter Three (#ulink_cbc29765-a3c8-5ad6-a0ac-49613fda67d1)

‘The full day dwelt on her brows, and sunn’d

Her violet eyes.’

—Alfred, Lord Tennyson:

‘The Gardener’s Daughter’

The studio door slammed and a gust of wind blew through the window. Crossing the room, Benedict heaved down the sash. Miss Cameo Ashe had not yet appeared on the street. She’d still be going down the stairs with that quick light step he’d noticed, in her fine kid boots.

Her boots had exposed her. She’d been dressed in that alluringly simple grey dress, which had all the marks of simplicity that only came from quality, carved ivory buttons all the way down the front, a pristine lace collar and cuffs. Her figure was slender, willowy, her tiny waist emphasised by her corset, yet not in the over-exaggerated way he hated, for she was perfectly proportioned. Nestled at the tender point of her throat above her collar was her cameo necklace tied with a black-velvet ribbon, a large stone, black and white, the carving in relief exquisite. But her elegant, obviously expensive boots were the biggest clue. And her ankles, which he’d been unable to ignore as she sat on the armchair, were equally elegant, with the delicate lines of a purebred filly.

She was no orphan girl turned out on the street. Certainly there was a strength to her he’d noticed immediately, a determination that suggested an ability to survive, but there was also a vulnerability he found himself unable to define.

The story she had told him. His mouth lifted at the corners. It had so many holes, that story, yet she struggled on, trying to convince him she was a girl who had no choice but to be an artist’s model. How did she expect him to believe her when her voice held no hint of the streets? True, she explained that by saying she’d been taken in by a genteel lady, but it hadn’t added up.

At his easel he idly picked up a paintbrush, running it through his fingers. Explanations played in his mind. Nothing she told him made sense. Yet she intrigued him, captivated him. He hadn’t been able to believe it when she had lifted off her bonnet and eased the pins from her long black hair. As each silken strand was liberated, his heart had drummed faster and faster.

He’d found her. He’d begun to think it wasn’t possible, that he might never discover a model for the painting of his dreams. Yet there she was, standing in front of him, slender yet strong. And her eyes. Shaded beneath her bonnet, they had looked grey or blue outside the door when he had first met her. In the light of the studio he’d discerned they were the rare shade of purple he had searched for.

He’d already painted the background of the portrait in painstaking detail. It had been frustrating beyond belief to have an empty space at the centre of the canvas, waiting for the model to appear in order to complete the work.

His grasp tightened on the paintbrush as he visualised her. It would be all too easy to respond to her as a man rather than a painter. Not only did the quickening of his body tell him of his instant attraction to her physically, but also the curious vulnerability he saw in her eyes had touched him. She was no hardened model.

He laid down the brush and ran his fingers though his hair. ‘Trouble,’ he said aloud. ‘That’s what you are, Miss Ashe. Trouble.’

A knock came at the door. Was she back again to elaborate on her story? He hoped she wasn’t planning to cancel the arrangement. With a frown, he realised just how much he didn’t want that.

It wasn’t his mysterious new model standing there.

A familiar husky female voice greeted him. ‘Hello.’

‘Maisie. You’d better come in.’

She entered the studio with the sensual walk that so enticed her many admirers. It was a shame such a movement evaded capture on canvas, he often thought, though its sensuality had long ceased to tempt him. The appeal of Cameo Ashe’s awkward self-consciousness, on the other hand...

Loosening the thick cream-coloured shawl she wore, Maisie dropped it lazily on the chair by the fire to reveal her blue dress, cut low at her full breasts. Her thick, corn-coloured hair curled. He’d painted her as Demeter, the Greek goddess of the grain, with her arms full of wheat. The ripe epitome of plenty was young Maisie. But as an artist he knew hers were the type of looks that faded quickly.

Miss Ashe’s face flashed into his mind. Hers was a beauty that would stay the years, for it was in her bones and in her bearing. Puzzlement hit him again. Just who was she? And what had led her to him?

‘I came as soon as I heard you’d been looking for someone for your new work,’ Maisie said. ‘Why didn’t you come straight to me? Didn’t you want me to model for you?’ Her arms looped around his neck, giving him a full view of her luscious flesh. ‘No one else is as good as me.’

He unlooped her clinging arms. ‘You’re not right for this painting, Maisie.’

She pouted. ‘I want to come back.’

With a smile she traced a teasing line from his chest down towards his trousers.

‘You walked out on me, remember?’ Benedict reminded her. More accurately, her affections had wandered, he recalled drily as he removed her hand, to another man who’d shown her more attention. Clearly that hadn’t worked out.

Maisie moved her shoulders with a flounce. ‘Only because you’re always painting, painting, painting. It drove me mad. I wanted you to take me out once in a while.’

‘Painting isn’t just what I do.’ He’d tried to explain it to her many times before. ‘It’s who I am. I paint the way I breathe.’

‘But it’s so boring sitting here all day!’

‘Well, you’ve been spared that. I’ve found the model for my next work.’

From the flare of jealousy in her eyes he judged she didn’t like that news. ‘Who is she? Annie? Jenny?’

‘It isn’t anyone you know. It’s someone quite new.’

Maisie thrust out her chest like an indignant chicken. ‘Why’s she muscling in on our patch?’

That was indeed the question, Benedict brooded. Just why did Miss Ashe want to be his model?

‘Never mind.’ He picked up Maisie’s shawl and gave it to her. ‘I have to work.’

‘What a surprise,’ she snapped crossly.

At the door she turned and let the shawl fall away from the front of her dress. ‘You know where to find me, Benedict.’

The door closed behind her and Benedict let out a sigh of relief.

Models. He’d not let himself fall into a relationship with one again. When an artist painted a woman posed before him, he created an idealised version of her and, sometimes, that ideal enticed him into bed. But he wouldn’t be tricked that way again. He needed to concentrate, stay focused. He smiled inwardly. It was easier to paint without live models, but he was no landscape artist. Views weren’t enough for him.

Yet Miss Cameo Ashe, with her mysterious mix of spirit and beauty, stayed in his mind. He picked up his pencil and began to draw.

* * *

Cameo lit another candle. The flame flickered, sending shadows dancing on the walls of her blue-and-white bedroom, newly papered in a flowered print, for her mama liked to keep up with the times. Just recently she had installed a water closet down the hall, exactly the same as Queen Victoria’s.

It was the window seat in her bedroom Cameo loved most. The blue chintz curtains were open tonight, letting in the cool air. Through the windowpane a full moon outshone the fog, silvering the dark grey trunk and slender boughs of the ash tree outside. Sometimes, she heard the call of a nightingale in the square as she sketched through the night. Trying again and again, always aiming to improve. Attempting to make her hand recreate what was in her mind, in her heart. It was so hard, working alone. There was no one to share it all with, the triumphs and the failures. No one who understood that hidden, passionate part of her. No one who sensed the heat of her flame. Now, at last, even though it was a secret, she had a chance. To watch and to learn from a real artist.

From Benedict Cole.

She clasped her pencil. As his model she would spend hours in his studio, watching him as he worked like the apprentices of old and yet he had no idea of her true identity. There was so much she’d be able to learn, incognito.

So you’re at my mercy.

The sense of danger returned as his words reverberated in her brain. He suspected her, but she had to take the risk.

Taking up a fresh sheet of paper, she stretched. She’d sketched for hours perched on the gilt chair in front of her dressing table with her blue-and-white china jug and basin, silver hairbrushes and bottles of scent pushed impatiently aside.

A muffled voice came from outside the door. ‘Cameo? Are you still awake?’

‘Come in.’

‘What are you doing up?’ George entered in his black-tailed dinner jacket, his bow tie loosened. ‘I saw your candle. You ought to have been asleep hours ago.’

‘So should you. Where have you been? At your club, I suppose?’

‘Got it in one.’ With a yawn he stretched his legs out on the window seat and propped a chintz cushion behind his brown hair. ‘What a night. I’ve been playing cards. I say, I ran into Warley. He’s coming to the ball. Frightfully keen on you, isn’t he?’

Cameo grimaced. ‘Unfortunately.’

‘He lost a lot of money tonight, I believe.’ George craned his neck to look at her. ‘And what have you been doing? Painting?’

With her pencil she pointed to the pile of discarded paper. ‘Just drawing, trying to improve.’

He shook his head. ‘You’re a strange sister for a fellow to have, Cameo, with all this fuss about art. Why can’t you just be interested in gloves and bonnets like a girl ought to be?’

‘Like someone we both know, is that it?’

To her astonishment George coloured bright red. ‘Actually, there’s something I wanted to tell you.’ He grabbed another cushion and tossed it in the air, catching it neatly. ‘The thing is, I’ve decided to ask Maud Cartwright to marry me.’

‘Finally!’ Cameo wanted to leap up and hug her brother, but they never did such a thing in their family. ‘I thought you’d never ask her.’

‘Well, it takes me a while to come to a decision, but once I’ve made it I stick to it. That’s my way.’

‘Have you decided when?’

‘I thought I’d pop the question quite soon if I can get my courage up. Maybe at the ball.’ He tossed the cushion up again but she wasn’t fooled by his nonchalance. ‘Not sure she’ll have me.’

‘How could you possibly think Maud doesn’t want to marry you?’

‘I haven’t been entirely sure.’ He flushed redder and added, ‘Whether it’s more than friendship. We’ve all known each other so long.’

‘Since we were children and used to play in the square together.’

George grinned. ‘You were constantly in trouble for climbing trees.’

‘Nanny always shouted at me about the dirt and grass stains. You scaled trees as well, George, and you never got into trouble for it but Maud never wanted to climb. She always looked perfect in her pinafore and curls. Do you remember how she clapped when you got up on to the top branches?’ Cameo laughed softly. ‘Maud always loved you, I think. Oh, I’ll be so happy to have her as a sister.’

‘I expect it’s mutual.’

‘Everyone will be delighted.’ She mimicked their father’s gruff tone: ‘“You’ve made an excellent choice for your future wife, George.”’

They both laughed.

‘I’m so pleased for you,’ she said simply.

‘I’m rather pleased myself.’ He stood and tousled her hair on his way out the door.

How lucky George and Maud were to have each other, Cameo thought, as she stared out the window.

Benedict Cole’s mocking expression flashed into her mind. Until tomorrow, Miss Ashe.

There was no doubt he suspected her. Her temper red-hot, she’d grasped the opportunity to learn from him, but there was a deeper part of her that disliked being forced to deceive him, the same way she was deceiving her parents. It troubled her even though she didn’t want to admit it.

With a sigh she blew out the candle. Somehow, she had to keep his suspicions and her own doubts at bay. She wanted—no, she needed—to learn to paint.

Yet as she lay in bed, the sudden recollection of the artist’s sardonic gaze gave her stomach a sharp twist.

Cameo had to wonder if she would learn more than she’d bargained for from Benedict Cole.

Chapter Four (#ulink_492a45f5-e9b0-577d-a87d-e074951ce4b5)

‘And stirr’d her lips

For some sweet answer...’

—Alfred, Lord Tennyson:

‘The Gardener’s Daughter’

Cameo hitched up the skirt of her blue-poplin gown, avoiding the puddles in the alleyway. She’d dressed with care, avoiding her finer gowns. Benedict Cole mustn’t have any more clues as to her real identity.

In Soho, amidst the morning bustle, she made sure her family’s crested carriage stayed out of sight. Bert obligingly agreed to collect her later. For a moment she stood and watched as the shopkeepers rolled up their awnings and opened their shutters to reveal their goods on display in the windows, the apprentices washing down the windows and stoops. How she wished for time to sketch the lively scene. She wasn’t often out so early and she certainly had never seen the fresh fruit and vegetables being delivered in old carts pulled by heavy horses and one small cart pulled by a donkey.

Outside the bakery she stopped to pass some money to Becky, sitting with her matches forlornly laid out in front of her on the cobbles.

‘Thank you, miss. I never thought you’d remember.’

‘Of course I remembered, Becky. I promised.’

The girl sighed. ‘Lots wouldn’t, what if they promised or not.’

Becky would have the money Benedict Cole had promised her for being a model, Cameo decided, as she ascended the narrow staircase to the studio. It seemed deceitful to take payment from the artist when she knew she received a fair exchange, with the painting lessons he was unsuspectingly providing. It wasn’t as if she needed the pin money. It would be shoddy, as though she were cheating him.

On the attic landing Benedict opened the door wide. ‘Ah, Miss Ashe, you’re on time today.’

Cameo swept by him. As Lady Catherine Mary St Clair she would have made a spirited response. As Miss Ashe she must keep her temper.

‘I’ll endeavour to be punctual from now on, Mr Cole,’ she said with assumed meekness, as she removed her bonnet and cloak.

He seemed to hide a smile as he appropriated them from her and dropped them over the armchair by the fire. He hadn’t fallen for her obedient act.

Retreating to the window, she raised her arms, curving them above her. ‘Do you need me to take my hair down again?’

Her movement held his brooding glance. ‘I ought to paint you like that. No, leave your hair up for now. I wish to focus on your face. I need to get that right first.’

And she’d styled her hair in a simple knot to ensure she might easily put it up again. Vexed, she dropped her arms.

As she glanced out of the window at the rooftops and chimneys, towards the clouded sky, it struck her again how wonderful it was to have no curtains. What a contrast with the thick-cut velvet cloths of the drawing room in Mayfair that constantly felt as if they stifled her.

An acid voice broke her reverie. ‘If I might have your attention, Miss Ashe.’

Biting her lip to prevent a retort, she queried, ‘Where do you want me?’

He paused for a moment before he pushed out the shabby gold-brocade chaise longue. ‘Here. Sit down. Don’t go slouching into the side. Keep your spine straight and face me.’

How she would continue to obey his curt instructions without a quick rejoinder she simply didn’t know. Squarely she placed her feet in front of her and crossed them at the ankle, wishing for something to lean against. Still, the chaise longue was softer than his armchair and she would allow no fault to be found with her posture.

‘That will do.’

As he rested on his heels, her whole body stiffened under his scrutiny.

‘You need to remain still,’ he commanded her brusquely.

How could she be still with him staring at her? She dropped her shoulders and puffed out a slow breath.

‘Now, turn to the right. No, not like that, turn some more.

‘More.

‘Now raise your eyes. Raise your eyes! Not move your whole head.’

‘I’m not sure what you mean!’ Cameo exclaimed, exasperated.

In a single swift movement he vaulted beside her. He clasped her chin. ‘Raise your eyes, but hold your chin straight. Like so.’

Cameo jumped as he cupped her face. His fingers were strong, with a sensitivity that told of his artistic temperament.

He trailed his fingers lightly against her skin. ‘You won’t be able to jump like that when I’m drawing you.’

‘I didn’t jump! A draught must have come in from the window.’

‘I haven’t yet opened the window.’ Still scrutinising her, he backed away and pulled a stool into position behind the easel.

‘That’s it.’ He crossed his legs in front of him in an easy, practised manner. ‘Now you must hold still while I do my initial drawings. Can you do that?’

‘Yes.’ Why, from now on she vowed not to move an inch. She’d keep her attention on the reason why she’d come.

Painting lessons.

A chance to see a real artist at work.

A thrill ran through her whole body.

From where she sat with her head towards the interior of the studio she had a perfect view of exactly what Benedict Cole was doing. He wore no paint-splotched cover shirt today, just a loose white shirt with the neck open and a paisley waistcoat carelessly buttoned down to dark brown woollen trousers, his feet clad in well-polished boots.

Taking up a large sheet of paper, he propped it against the easel. Holding a stick of charcoal, he flexed his muscled arm and made strong, bold strokes, glancing back and forth at her all the while. Soon she became transfixed by the way he held her in his sights, put his head down to draw, then came intently up again in a single movement, like a breath. More than once he impatiently pushed back the black lock of hair that fell over his forehead, down towards two lines that creased between his eyebrows as he frowned in concentration.

You think you’re watching me, Mr Benedict Cole, when in fact I’m watching you. She smiled inwardly.

How fast he drew. Perhaps lack of speed was her first mistake with her own work. She was too tentative, too slow. She considered each line before she put it down. He sketched with an assurance she envied, rapidly completing one drawing, putting it aside and just as quickly picking up another piece of paper, skimming across the page with a strong sweep of his arm.

On and on he drew. How long she sat there she wasn’t sure, but surely one hour passed, then another. Her neck locked and ached. She hadn’t realised how difficult it was to hold one position without moving. The muscles of her tight neck wanted to roll, her stiff legs to stretch.

To keep her mind off it she continued her survey of the studio. There were things she hadn’t noticed yesterday. The canvases propped about the room appeared to be in various stages of progress. One seascape looked particularly good, but most of them were faced to the wall, their subjects hidden from her assessment. There were frames and odd pieces of wood, too, stacked to one side. It appeared chaotic at first glance, but she discerned an order beneath the chaos. He seemed to know exactly where to find what he needed with speed and ease. He reached for his tools on a cluttered painting table beside the easel without a sideways glance. There were strange objects on the table, too. A pile of stones, a bird’s feather and some oddly shaped shards of smooth glass.

Peeking to her left without moving her head, she spotted a huge bed with a carved wooden bedhead in the corner of the room. She hadn’t really noticed it yesterday. Why, she’d come not only to Benedict Cole’s studio, but also to his bedroom. Her cheeks felt hot.

He had left the bed unmade, she noted in amazement. The white sheets were rumpled and the pillow dented. The thought of him lying there sent an unexpected thrill through her body. Hastily, she focused on the carved bedhead above, with its intricate patterns of blackberries and leaves engraved into the glowing dark wood.

Next to the bed stood a washstand with a mirror, a thick white-china jug and bowl on its veined marble top, his brush and razor lying carelessly to the side. She pictured him shaving, the sharp blade sliding through the soap along the skin of his strong jaw. He’d use the same smooth strokes as when he drew, she imagined.

Would he be bare-chested? The question popped into her mind, startling her. Why, Lady Catherine Mary, she reproved herself in her old nanny’s voice. What a thing to think. But the intimate image of him shaving persisted, the muscles of his shoulders rippling beneath his olive skin as he leant over the water basin, his face dripping with water as he splashed off the soap.

Unable to hold still, she wriggled on her seat.

Benedict’s voice shot across the room. ‘Don’t move.’

‘I’m sorry.’

‘I told you that you’d have to hold still for long periods of time,’ he snapped, not raising his head.

‘I will be quite able to if you give me a moment to rest.’ The man was a tyrant. She had no intention of being bullied by him.

He tossed down the charcoal. ‘Yes, of course.’

With relief Cameo stretched her taut body. She knew Benedict Cole kept watching her as he leaned against the edge of the stool.

‘You’ve done well. Not every model can keep up with me.’

‘Thank you.’ Surprised at how much his praise pleased her, she stepped towards the easel.

‘Have you always painted?’

‘I can’t not paint.’

At last. He did understand. ‘I know just what you mean,’ she said impulsively, then bit her tongue. She momentarily forgot he must never suspect she, too, was an artist, or wanted to be. How wonderful it would be to reveal her true self and all her secret longings. But she had to pretend at home and here in the studio, too.

‘Watching you draw, I can see that it’s part of you,’ she said at last. ‘It seemed to come from somewhere within you.’

He studied her closely. Too closely. Had she revealed too much? ‘You’re observant. Yes, when I paint or draw it sometimes feels as if there is another hand guiding me. I’m doing what I’m meant to do. I’m driven to do it. There’s no alternative.’

‘May I see the sketches?’

‘I don’t show most of my models my first drawings. They’re not always flattering.’

‘I’d still like to look at them.’

‘If you insist,’ he said eventually, though she suspected he’d been about to refuse. ‘I started some of them yesterday.’

‘You drew me straight away?’

Collecting the sketch papers from the easel, he made no answer, just passed them to her before leaning back again, his arms crossed.

Cameo held up the first drawing, then the next and the next. They were simple head studies. Yet in each sketch was the mark of a true artist.

‘You—you’ve seen me.’ Her gasp escaped from her lips. ‘I mean, you’ve really, really seen me.’

He uncrossed his arms. ‘When an artist looks at his model he’s not just seeing the exterior. He must discern more.’

The smell of turpentine, soap and another more masculine scent she’d noticed the day before reached her as he moved closer and pointed to the drawings. ‘When I look at you it’s the line of your chin that reveals the determination of your character. But there’s something else. There’s wistfulness in your eyes, as though you’re longing for something.’

Instantly she dropped her lashes. ‘You saw this in my eyes?’

‘Yes. Your chin says one thing, but your eyes say another. It’s as if part of you is waiting to come to life. I perceived it immediately.’

Why, in a few hours this man had learned more about her than most people who had known her all her life. He had spotted what she tried to keep secret, contained within her body, all the passion and desire always threatening to brim over. And she thought she’d had his measure, watching him as he drew!

She forced out a laugh. ‘I have no such longing.’

‘Don’t lie to me,’ he rasped. ‘I’m an artist. I know what I see.’

Impatiently Benedict seized the sketches. ‘Let’s return to work.’ After a moment he cast down the charcoal. ‘It’s no good.’

‘What do you mean?’ Cameo asked indignantly. ‘I haven’t moved.’

His eyebrows knit together as he scowled at the paper in front of him. ‘It’s not that. I have the angle right, but I need—’

‘What is it?’

Impatiently he ran his fingers through his hair. ‘Your determined chin, Miss Ashe. I’m afraid it leads to your neck.’

Her hands flew upwards. ‘I don’t understand.’

‘I told you I won’t merely be painting your face. I’ll also be painting part of your body. I did make that clear.’

Cameo’s heart raced. Of course she understood what he’d said to her, but she hadn’t considered which parts of her body needed to be revealed.

‘I expected that, Mr Cole,’ she forced herself to reply with feigned unconcern. ‘What exactly is it you ask of me now?’

He pointed to her blue gown. ‘Unbutton the collar of your dress.’

A gulp of air rose up from her lungs. It was no more than she revealed in a dinner gown or a ball dress. In such evening attire her neck, even her shoulders and décolletage were bare. Yet her fingers became clumsy as she reached for the tiny buttons that held the collar tight, her heart beating so loudly he surely heard it.

She undid the top button. He made no sign to stop her. She undid the second. She ought to feel shy with her throat bare in front of him, yet she didn’t at all.

‘Is—is that enough?’

‘Almost.’

Cameo undid the third button.

His eyes darkened with an unidentifiable emotion. ‘Wait.’

With long strides Benedict crossed the room and reached for her.

Her body gave an instinctive jerk.

‘I’m not going to hurt you.’

No muscle moved in her body as he lifted her cameo necklace from where it had been lying on the soft fabric of her dress and dropped it down into her open collar. It fell against her skin towards the crevice between her breasts.

The cooler stone met her warm skin and she gave a sharp intake of breath, but the necklace wasn’t the cause of her sudden ragged breathing. His closeness, the heat from his body emanating through the thin cotton of his shirt, did that. He moved his hand away, but his powerful vision stayed transfixed upon her throat as if he were actually touching her skin.

His lips came down at the exact moment she raised hers to his. They moved together as one, his strong arms lifting her from the chaise longue as she stood on tiptoe to reach him while a greater force thrust them together. Nothing stopped her seeking the hardness of his lips in that moment, causing an explosion within her that dived to the depths of her stomach and flamed up again as a deep sigh opened her mouth. She let his cool tongue probe, meeting his hunger with hers, longing to taste him. She flung her hands around his neck as he wrenched her body even closer in his fierce embrace.

With a groan, Benedict heaved himself away from her and ran his hand through his hair. ‘Goodness.’

Cameo sank on to the chaise longue, clutching her bodice. Her heart felt like a bird beating its wings against the cage of her chest.

Benedict retreated behind the easel. ‘I warned you the relationship between artist and model can all too easily become intimate.’ Harsh lines bracketed the mouth that just moments before had so passionately searched hers. ‘That was...regrettable.’

She couldn’t reply. She could only gasp for breath.

His glance flew to his easel as though it were a powerful magnet. ‘This painting may be my greatest work. I can’t have anything interfere with my focus. I must complete this. It’s what I’m meant to do.’

Silence fell between them, except for the gasps that continued to escape her lips.

‘Some people don’t think artists have any rules.’ He spoke again, his voice husky. ‘But they do. They must. To be able to paint each day without fail there must be the kind of self-discipline that cannot be broken.’

Words evaded her as her body continued to shudder.

‘Do you understand? I cannot allow this between us. If you’re to remain my model—it must be as if what just happened never occurred.’

With shaking fingers Cameo touched her tender lips. ‘I see.’

‘I can assure you there will be no such lapse again.’

He coiled away from her and thrust his taut hands against the chimney piece. When he rounded on his heel, his expression appeared unfathomable.

‘I think we’ve had enough for today.’ He ran his fingers through his hair again. ‘We’ll continue tomorrow, Miss Ashe.’

Shocked to her core by her response to him, Cameo buttoned the bodice of her dress right to the top of her neck. In a trembling grip she grabbed her bonnet and cloak and rushed from the studio as fast as her shaking legs could take her.

Chapter Five (#ulink_8d57fda2-ae7f-563b-a555-ec56844ee941)

‘Ah, happy shade—and still went wavering down,

But, ere it touch’d a foot, that might have danced.’

—Alfred, Lord Tennyson:

‘The Gardener’s Daughter’

A hand parted the fronds of the potted palm tree. ‘What are you two whispering about?’

‘George!’ Cameo dropped her fan. ‘You startled me.’

Her brother gave his easy smile. ‘You look quite panicked. Just what is it that you have to be so guilty about?’

Retrieving her fan, Cameo pretended to study the ballroom, with its huge white pillars, gilt-painted cornices and ferns in huge tubs. The chandeliers scattered their rainbow reflections on the shimmering polished floor, challenging the dazzle of the women’s bright jewels. ‘Nothing.’

‘Hmm. Why is it I don’t believe you, little sister?’ George turned to Maud, standing beside Cameo, who peeped up at him from beneath her lashes.

‘Hello there,’ he said with a smile that Maud returned adoringly with added dimples. ‘Now tell me what is it you’re both so intent on discussing here in the corner that keeps you from dancing?’

‘Oh, well...’ Maud fluttered.

‘Are you telling each other secrets?’

Cameo had considered telling Maud all about her visits to Benedict Cole’s studio. How she wanted to pour out to her friend everything that happened. But she didn’t want to put Maud in such a position. It would be unfair, even though she longed to tell her all about it.

‘I don’t think you could keep a secret from me, could you, Maud?’ George asked. ‘How would I get it out of you?’

Maud giggled.

‘Blast.’ George’s teasing expression changed. ‘Look who’s coming towards us. It’s your new beau, Cameo.’ He raised his voice and gave a nod. ‘Good evening, Warley.’

‘St Clair.’ The man who approached them gave a stiff bow in return and then bowed to Cameo. ‘I hoped you might do me the honour of giving me the next dance, Lady Catherine Mary.’

As she bent a reluctant curtsy in reply her skin crawled, as it always did when she came close to Lord Warley. Still, there was no way to refuse the son of her papa’s oldest friend a dance. She loved her father too much for that.

‘I’m sure she’d be delighted,’ George said with a straight face.

The orchestra struck up another Viennese waltz. Cameo tried to avoid instinctively pulling away as Lord Warley pressed her up against him.

His tongue wet his lips. ‘Delightful evening.’

‘Delightful.’ Cameo dodged his feet landing upon her toes in their white-kid slippers, which offered no protection. He made a sharp turn and she stumbled.

‘Watch your step.’

It had been his fault, not hers. She fumed as he spun her again, nearly bumping into the couple next to them. George gave her a grin as he expertly swept Maud past.