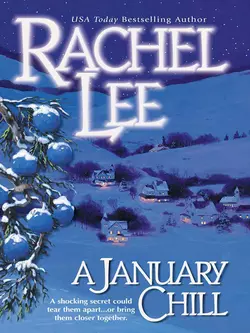

A January Chill

Rachel Lee

Secrets, lies, blame and guilt. Only love and forgiveness can overcome the mistakes of the past. Witt Matlock has carried around a bitter hatred for Hardy Wingate, the man he holds responsible for the death of his daughter. And now, twelve years later, the man he blames for the tragedy is back in his life–and in that of his niece, Joni.Widow Hannah Matlock has kept the truth about her daughter Joni's birth hidden for twenty-seven years. Only she knows that Witt is Joni's father, and not her uncle. She and Witt have never spoken of the night she tried to get even with her philandering husband by seducing his brother. But with Hardy coming between Witt and Joni, Hannah knows she must let go of her secret…whatever the consequences.Anger, resentment and deceit threaten to destroy a family that teeters on the verge of collapse, until four damaged souls can learn to forgive…and allow themselves to love.

“Why’d you come back to Whisper Creek?”

The sleepy question came from behind him. He turned and saw that Joni’s eyes were open. She still looked sleepy, and amazingly huggable.

He shrugged. “I don’t know. It’s home.”

She shook her head. “I’m serious, Hardy. The way Witt has treated you… Why didn’t you take a job with some architectural firm in Denver or Chicago? You could have made more money.”

“Is that what you think I should be doing? Making more money?”

“No. It’s just that I wondered why. You had a way out.” She pushed her hair back from her face. “It’s all about Karen, you know. It’s all about this feeling of unfinished business. At least for me.”

Before he could say a word, she’d disappeared into her room. He turned back to the window and stared out into the teeth of the blizzard. Yes, it was unfinished business that had brought him back. But not Karen. Not Witt.

Joni.

“Lee crafts a heartrending saga….”

—Publishers Weekly on Snow in September

A January Chill

Rachel Lee

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

1

The November evening was frigid and blowing dry snow so hard it stung. Joni Matlock came through the back door of the house, taking care to stomp the snow off her boots, then removed them and set them by the wall on the rag rug. Her feet instantly felt cold, because the mudroom wasn’t heated. Shivering a little, she shook out of her jacket, tugged off her knit cap and hung both on a peg next to her mother’s.

Then she darted into the kitchen and gave thanks for the heat that made her face sting. Her mother was sitting at the table in the dining room, visible through the open doorway, apparently busy with her needlework.

“Mom,” Joni said, “you put too much wood in the stove again.”

Hannah Matlock looked up with a smile. “I get cold, honey. You know that.”

“It must be eighty in here.” But Joni wasn’t complaining too seriously. It felt good after the bitter chill of the dark evening outside. On the trip home from the hospital where she worked as a pharmacist, her car heater didn’t even have time to start working. She felt like an ice cube.

“There’s fresh coffee,” Hannah said, bowing her head over her stitchery. “And I thought I’d just heat the leftover pot roast for dinner.”

“That sounds good.”

Joni poured herself a mug of coffee and whitened it with a few drops of cream. Real cream. She couldn’t stand the nondairy creamers. Then she stood in the doorway between the kitchen and dining room, sipping the hot brew and watching her mother stitch.

At fifty, Hannah’s hair was still as black as a starless night, a gift from her Ute ancestors. Her face, too, held a hint of the exotic in high cheekbones, and was still nearly as seamless as her daughter’s. Her eyes were dark brown, almost as dark as her hair, and Joni had always envied them because they seemed to hold mystery.

Joni, for her part, had bright blue eyes. Hannah always said Joni’s eyes had captured the sky. Joni felt differently about them. Blue eyes were a lot more sensitive to the light, and all winter long she had to hide them behind sunglasses.

The women were alike enough, however, to be sisters.

Joni joined her mother at the table, cradling her mug in her cold hands. “How was your day?”

“Delightful,” Hannah said. She rarely said anything else. “Well, there was one bad spot. I had to help put down Angie Beluk’s dog.” Hannah worked as a veterinary assistant four mornings a week.

“I’m sorry,” Joni said, feeling a pang. “What was wrong?”

“Cancer.” Hannah sighed and snipped her thread. Then she put her hoop to one side. “Poor Angie. She had Brownie for sixteen years.”

“That’s so sad.”

“Well, it happens, unfortunately. On the brighter side, we delivered a litter of pups. What about you? How was your day?”

Joni sipped her coffee, feeling the heat all the way down to her stomach. “Oh, the usual. I rolled pills, mixed elixirs, chatted with a dozen people….”

Hannah laughed. “You make it sound so boring!”

Joni smiled back at her. “It’s not. But it sure isn’t the height of adventure.”

Something in Hannah’s face softened. “Is that what you really want, Joni? Adventure?”

After a moment, Joni shook her head. “Not really. Remember the curse, ‘May you live in interesting times’? I’ll settle for ho-hum, thank you very much. Want me to put the pot roast on to heat before I go change?”

“No, honey, I’ll do it. You just go on up.”

“Okay.” Taking her mug with her, Joni rose and disappeared into the living room, in the direction of the stairs.

Hannah stared after her, a faint crease between her eyebrows. Maybe, she thought for the hundredth time, she had made a mistake in moving them fifteen years ago to Whisper Creek after Lewis died.

She had told herself at the time that it was for Joni that she had brought them here, but now, in retrospect, she wondered if she hadn’t really done it because she was afraid herself. After all, staying in Denver had meant finding reminders of Lewis around every corner and in every familiar face. She had tried to go back to work but had found being in the hospital again was just impossible for her. Every sound, every smell, reminded her of Lewis and the fifteen years they had shared.

So maybe she hadn’t really done it for Joni. Maybe she had been lying to herself when she justified the move by assuring herself she was taking the child away from all the bad influences to a quiet community where kids didn’t hang around in gangs and kill innocent doctors who were crossing a parking lot on the way to save lives.

Maybe she had been lying to herself when she argued that Joni would be better off near the only family either of them had, Lewis’s brother, Witt.

Maybe those had all been excuses because she was unwilling to face her own fears and her own pain—and her shame.

But she hadn’t really wondered about it until lately. Not until three years ago, when Joni had finished her schooling and moved back into her old bedroom while taking a job at the little mountain hospital just outside town. For the first time it had seriously occurred to Hannah that she might have crippled Joni in some way.

Because what could a twenty-six-year-old woman possibly want in this town? There was no adventure, few single men of her age, nowhere to go on Friday night other than a movie theater and a couple of bars. Why hadn’t Joni taken a job somewhere else? Her pharmacy degree and her grades surely would have given her her pick.

But Joni had chosen to come here and live with her mother. Not that Hannah minded. It just made her feel terribly guilty.

As did her secret, the one she had never whispered to a soul. Over the years she had almost convinced herself it wasn’t true, but lately…lately every time she wondered if she had gone wrong somehow with Joni, the thought came back to haunt her.

Maybe she had made it worse by keeping it so long. Maybe she had deprived Joni of something essential. Every time the thoughts rose in her mind, she shied away from them, telling herself that the truth would have made no essential difference, that all she had done was protect herself and her child from shame.

But she hadn’t really protected herself, because the shame still burned in her, making her squirm inwardly. Reminding her that her motives had never been as pure as she had told herself. Keeping her from the one thing she wanted more than anything apart from Joni’s happiness.

But it was too late now, she told herself. She had made her mistakes, and there was no way to mend them. She had to believe that, at the very least, she had taken good care of her daughter.

Sighing, she rose from the table and went to put the leftovers in the microwave to warm. And she tried not to think of the terrible secret she guarded.

Upstairs, Joni’s room was like an oven. The heat from the woodstove downstairs funneled up the stairwell and filled the bedrooms. It was one of the reasons she was always trying to persuade her mother not to put so much wood in the fire.

Smothering a sigh, she battled to open the argumentative bedroom window and let some of the overpowering heat escape into the frigid night. The icy chill that only a few minutes ago had been making her so uncomfortable now actually felt welcome as it sucked some of the heat out.

Her room was blessed with a walk-in closet large enough to be a dressing room—which was a good thing, since the room itself barely had enough room for the four-poster double bed and a rocking chair. The closet was chilly, since it had been closed all day, and she shivered a little as she changed swiftly into what she called her “compromise clothes,” a pair of chinos and a long-sleeved cotton shirt. She wouldn’t suffocate at the temperature her mother preferred, yet they would prevent her from shivering in the drafts that always stirred in this old house.

Downstairs, she found Hannah humming quietly as she set the table. Hannah frequently hummed, though she never sang out loud, and Joni always found the sound comforting. Taking the plates from her mother’s hands, she finished the job.

“So not one exciting thing happened today?” Hannah asked.

“Not really.” Joni put the porcelain candleholders in the middle of the table and lit the red tapers that were left from last Christmas. Every year, Hannah went overboard scattering red candles around the house for the holiday. Then they spent all the next year burning them. “Pneumonia is going around again. You be sure to stay away from anyone who’s coughing, Mom.”

Hannah gave her a wry smile. “I used to be a nurse.”

Joni laughed. “You’re right. I’m terrible about that.”

“I don’t mind. But I will remind you. And the same goes for you, Miss Smarty-Pants. Don’t forget to wash your hands.”

They exchanged understanding looks.

Hannah returned from the kitchen, carrying the casserole dish that held the remains of the pot roast. Using a big steel spoon, she began to dish out the food. “How bad is it? Are many people getting sick?”

“Bob Warner said the wards are almost full. The docs think this is going to be the worst winter in years.”

Hannah clucked her tongue. “Well, tell Bob that if they need extra hands, I’ll be glad to come in and help. I’m not that rusty.”

“He knows that.” Joni gave her a wicked grin. “You’ve been practicing on dogs and cats for a long time.”

“Child, you are terrible. The skills aren’t all that different.”

Joni pursed her lips. “I’m sure. And you know how to pin a patient down.”

Hannah looked over the top of her reading glasses at her daughter. “That can be useful on any ward.”

Then they both laughed and sat at the table, facing each other across the candles.

The best thing about living with her mother now, Joni often thought, was how they’d become such good friends. Her going away to college seemed to have given them just the distance they needed to cross the mother-child barriers, and what had grown between them since was something Joni wouldn’t have traded for anything.

“So,” Hannah said, “apart from pneumonia, what else happened in your day?”

Joni hesitated, knowing the family position on Hardy Wingate too well to suppose the news would be greeted warmly, but then decided to go ahead and tell her mother anyway. “I saw Hardy Wingate today. Apparently his mother is in the hospital with pneumonia.”

Hannah looked up from her plate and pursed her lips. “Joni…”

“I know, I know. Witt hates him. Well, you don’t have to worry about it, Mom. Hardy will barely talk to me.” Which was a shame, she thought. She’d had a crush on Hardy years ago, and while she’d outgrown it, she still thought he was attractive. And nice, despite her uncle Witt’s opinion.

“Well,” said her mother after a few moments, “I’m sorry Barbara is sick.”

Apparently it was okay to feel bad about Hardy’s mother.

After supper Hannah went back to her needlework and Joni did the dishes. There was a small window over the chipped porcelain sink, and she found herself pausing frequently as she washed to look out into the night. The hill there was so steep she could almost look over the neighbor’s roof toward downtown. She did, however, have an unimpeded view of the night sky, and since the moon was full tonight, she could even see the pale glow of snowcapped mountains in the distance.

Whisper Creek had sprung up around silver mines in the 1880s, nestled on the eastern edge of the valley between two mountain ranges. The town itself was built into the hills, and many of the houses clung to steep terrain. It had never grown large enough to spread into the valley to the west, where the land was flat and open. Her uncle Witt owned a lot of that land out there. Not that it did him any good. Runoff from the tailings left in the hills by miners a century ago had tainted the water and consequently the land. Brush was about all that grew out there, and even it was thin.

The land hadn’t always been poor. Back when the first Matlock had purchased it with the money he’d made from his own silver mine, it had been verdant with promise. But after about forty years or so, the cattle had started sickening and dying.

Uncle Witt hadn’t even tried to do anything with the land. What could he do? It would take more money than he had to reclaim it, and even though the EPA had declared the town and the area around it a Superfund site, there didn’t seem to be much improvement.

Joni sometimes looked at the land, though, trying to think of things that could be done with it. The view, after all, was spectacular. But who could come up with the money to turn it into a resort? Everyone in town talked about ways to draw tourists to the area, to give the economy another base apart from the unreliable molybdenum and silver mines, but so far no one had been able to ante up the investment money.

Realizing she was daydreaming again, Joni quickly returned her attention to the dishes. After a busy day at work, where inattention could cost someone’s life, she generally felt mentally drained and had a tendency to zone out when she came home. Today had been an exceptionally busy day, as the altitude, the dryness of the air and the low temperatures seemed to weaken people’s resistance.

Then there had been Hardy Wingate. She felt almost guilty for even thinking about him, but his face popped up before her mind’s eye. He’d looked exhausted, she thought. His square, bronzed face had been paler than usual, and his gray eyes had been bloodshot. He’d been in the hospital cafeteria, swallowing coffee in the hopes that caffeine would keep him going.

Seeing him, she had walked over to him and joined him. He’d looked at her almost hesitantly, as if expecting her to say something nasty. Or as if she were on some list of prohibitions he didn’t want to break.

“Hi,” she’d said, sitting across from him anyway.

“Hi.” His voice had sounded strained, weary.

“Are you sick?” It was a pointless question. He looked exhausted, but he didn’t look ill.

“My mother. I was up all night with her in intensive care.”

“I’m sorry.” And she truly had been. Still was. Barbara Wingate was a lovely woman. “Pneumonia?”

“Yeah.”

“How’s she doing now?”

“Better. They said I could go get some sleep.”

She pointed to the coffee. “That’s a great sleeping potion.”

For an instant, just an instant, he looked as if he might crack a smile. But then his face sagged again. “I’ll be here all night.”

“I don’t think so. You’ll collapse, yourself, if you don’t get any sleep.”

“I’ll be fine.” Then, without another word, he tossed off the last of his coffee, rose and walked away.

And now, standing at the sink, Joni heard herself sigh. He hadn’t even said goodbye, as if simple social courtesies were forbidden, too. And all because of Witt.

The phone rang, and she heard her mother pick it up in the living room. A little while later, Hannah’s laugh wafted to her. Good news of some kind. That was a plus. God knew they could use some.

Not that life was all that bad, but there were times when Joni thought they were all dying in this little town. Silver prices were lousy, and the silver mine was on minimal operation, which meant a lot of miners were on layoffs that were supposedly only temporary. The molybdenum mine was doing better, but there was some talk of cutbacks there, too.

This had always been a boom-and-bust town, and it looked as if they were once again on the edge of a bust.

And she didn’t usually feel this down. She wondered if maybe she was getting sick, too, then decided she just didn’t have time for it.

She drained the dishwater, rinsed the sink and was just drying her hands when her mother came into the kitchen.

“Witt’s coming over,” Hannah said. “He said he has some good news.”

Not for the first time, Joni noticed the way Hannah’s face brightened and her eyes sparkled when Witt was coming over. It was the only time Hannah ever looked that way.

“Great,” she said, although after talking to Hardy Wingate today, she was feeling surprisingly unreceptive toward the idea of seeing her uncle. Silly, she told herself. The feud was more than a decade old, so old they should all be comfortable with it. Why was she feeling so uncomfortable? Because she was afraid Witt would look into her eyes and read betrayal there, all because she had talked to a man she’d known since her school days?

How ridiculous could she get?

Witt arrived fifteen minutes later, apparently having walked from his house across town. When he stepped in through the front door, he brought the frigid night in with him, and Joni felt the draft snake around her bare ankles.

Witt was a bear of a man, over six feet, and broad with muscle from hard labor. He filled the doorway and then the small living room as he stripped off his coat and muffler. A grin cracked his weathered face, and his eyes, as blue as Joni’s, seemed to be dancing.

He wrapped Joni in a big hug, the way he always had, his arms seeming to make promises of safety and eternal welcome. Even when she was irritated with him, which she was every now and then, Joni couldn’t help responding to that hug with one of her own.

“You’re cold,” she told him, laughing in spite of herself.

“You’re warm,” he countered. “You’re singeing my fingers.”

“That’s because Mom keeps it so hot in here.”

Witt released her and turned to Hannah. “Still a hothouse flower, huh?”

Hannah laughed but shook her head. “Sorry.” The truth was, as Joni knew, her mother had spent too many cold nights as a child, and keeping warm made her feel as if she lived in the lap of luxury, even if the lap was a small, aging Victorian house on the side of a hill in a tiny mountain mining town.

“Well,” said Witt, greeting her with a much more restrained hug than he had given Joni, “if I suddenly dash out into a snowbank, you’ll know it’s because my clothes started smoking.”

Hannah laughed; she always laughed at Witt’s humor, Joni thought, not for the first time.

Hannah offered her usual gesture of hospitality. “I was just about to make coffee. Join me?” Hannah never made coffee in the evening, but she always said this same thing to a guest. Long ago, when she’d been eight or nine, Joni had asked her why.

“Because,” Hannah had explained, “it’s polite to offer refreshments to a guest, but I don’t want them to feel like they might be putting me out, so I always say I was about to do it.”

Joni had thought that was kind of silly. Why not let your guests know you were doing something especially for them? But she’d been watching Hannah’s hospitality charm people for years.

“Sure,” Witt said, following her toward the kitchen. “Coffee’s great, but yours in the best.”

He always said that. For some strange reason, tonight that irritated Joni. What was wrong with her? she asked herself. Why was she getting so irritated by things that were practically family rituals?

They gathered at the dining-room table, another family tradition. The only times they ever gathered in the living room were at Christmas or when they had company from outside the family.

Hannah brought out a coffee cake she had baked that day and cut a large slice for Witt. Joni declined.

“All right,” Hannah said when they all had their coffee. “What’s the good news, Witt?”

He was grinning from ear to ear, wide enough to split his face. “You’ll never guess.”

Hannah looked at Joni and rolled her eyes. Joni had to laugh. “I know,” she said to her mother. “He bought a new truck. Cherry red with oversize tires.”

Hannah laughed, and Witt scowled. “You’ll never stop teasing me about that truck I drive, will you?”

“Of course not,” Joni told him. “It’s a classic. Older than me, and so rusted out I can see the road through the floorboards.”

“Well, just so you know, I am gonna buy a new truck.”

No longer joking, Joni put her coffee mug down and looked at her uncle in wonder. “Are you okay? You’re not getting sick?”

“Jeez,” Witt muttered. “She’ll never lay off. Hannah, you should have got the upper hand when she was little.”

“Apparently so,” Hannah agreed. But her eyes danced.

“No,” Witt told his niece, “I’m not sick. I’m not even a little crazy. And if trucks didn’t cost damn near as much as a house, I’d’ve bought a new one years ago.”

“So what happened to make you buy one now?” Joni asked.

“I won the lottery.”

Silence descended over the table. It was one of the longest silences Joni could remember since the news that Witt’s daughter, her cousin Karen, had been killed in a car accident. Silences like this were frought with shock and disbelief.

It was Hannah who spoke first, almost uncertainly. “You’re kidding.”

Witt shook his head. “I’m not kidding. I won the lottery.”

“Well, wahoo!” Joni said as excitement and happiness burst through the layer of shock. “Double wahoo! That’s wonderful, Uncle Witt! Enough to buy a new truck, huh?”

But Witt didn’t answer her. Instead, he simply looked at her and then at Hannah. Another silence fell, and Joni felt her heart begin to beat with loud thuds. Finally she whispered, “More than enough to buy a truck?”

Hannah’s dark eyes flew to her daughter, then leaped back to Witt. She reached out a hand and touched his forearm. “Witt? How much did you win?”

Witt cleared his throat. “It’s…well…kinda hard to believe.”

“Ohmigod,” Joni said in a rush, feeling hot and cold by turns. “Uncle Witt…” She turned to look at her mother, as if she could find some link back to reality there. But Hannah’s face was registering the same blank disbelief. Things like this didn’t happen to people they knew.

“It’s…” Witt sighed and ran his fingers through his hair. “I won the jackpot.”

“Oh my God.” This time it was Hannah who spoke, her tone prayerful. “Oh, Witt, that’s a lot of money. How much?”

“Eleven million.” His voice sounded almost choked. “Of course, it won’t be that much. The payout is over twenty-five years, and there’s taxes and stuff but, um…”

Joni, always great at math, calculated quickly. “You’ll still be bringing home almost two hundred thousand a year,” she said. “My God. That’s incredible.” Then, as a sudden, wonderful exuberance hit her, she let out a whoop. “Oh, man, Uncle Witt, you’re on easy street now. So you get the new truck and a lot else besides.” She grinned at him, feeling a wonderful sense of happiness for the man who had been like a father to her since the death of her dad. “It couldn’t happen to a nicer guy. So, are you going to Tahiti?”

He laughed, sounding embarrassed. “Nah. Not unless Hannah wants to go.”

Hannah’s eyes widened; then her cheeks pinkened. “Tahiti? Me?” She waved away the idea. “What on earth would I do there? Besides, the winnings are yours, Witt.”

His face took on a strange tension, one Joni couldn’t identify. “So what then?” she pressed him.

“I haven’t had a whole lot of time to think about it, Joni. Jeez, I just found out last week.”

“Last week? You’ve been sitting on this for a week?” She couldn’t believe it. She would have been shrieking from the rooftops.

“Well, I didn’t exactly believe it. I wanted to verify it first. Then…well…” He hesitated. “I don’t want the whole world to know about it, not just yet.”

“That’s understandable,” Hannah said promptly. “But you must have been thinking about what you want to do with the money.”

But Joni’s thoughts had turned suddenly to a darker vein, one that left her feeling chilled. She’d heard about lottery winners and how their lives could be turned into absolute hell by other folks.

“Just put it all in a bank, Uncle Witt,” she said. “Put it away and use it any way you see fit. And just remember, you don’t owe anything to anyone.”

His blue eyes settled on her, blue eyes that she sometimes thought were the wisest eyes she’d ever looked into.

“I do owe something, Joni,” he said slowly. “Everyone owes something. I’m thinking about building a lodge on the property. You know how long this town has wanted something like that. It’d make jobs for folks around here, jobs that don’t depend on a mine. And if we had the facility, I’m sure the tourists would follow. God knows we’ve got plenty of snow and hills.”

But the chill around her heart deepened. Because the simple fact was, when there was a lot of money involved, nothing was ever that simple.

“Well,” said Hannah briskly, “this calls for a celebration. Let me get you a glass of Drambuie, Witt. What about you, Joni?”

“No thanks, Mom.” She hated to drink. Besides, something about this didn’t feel right. Witt was looking strange, and Hannah was looking disturbed, and there was suddenly an undercurrent so strong in the room that Joni could feel her own nerves stretching.

But she’d had that feeling before with her mother and her uncle. It had been there ever since she could remember, the feeling that things were being left unspoken. It was so familiar she hardly wondered about it.

But all of a sudden it seemed significant. And just as suddenly, Witt’s news didn’t feel like anything to celebrate.

The chill settled over her again, this time a strong foreboding. In her heart of hearts, she knew nothing was ever going to be the same again.

2

Hardy Wingate sat at his mother’s bedside and tried not to give in to the anxiety that was creeping along his nerve endings. Barbara was better, they told him. She’d passed the crisis. But he couldn’t see it. She was still on oxygen, she still had tubes running into her everywhere, and the only improvement he could see was that she wasn’t on a respirator anymore. Her breathing was still labored, though, and he knew things could change in an instant, no matter what they told him.

He touched her hand gently, hoping she could tell he was there. Since last night, when he’d brought her in, she hadn’t seemed to be aware of much. Which was probably a good thing. He hoped she wasn’t suffering.

But he was going crazy, sitting there with nothing to occupy him but worry and guilt. And memories. God-awful memories of sitting beside Karen Matlock’s bedside twelve years ago, just before she died. Just before Witt Matlock threw him out.

He didn’t blame Witt for that, but it had hurt anyway. And sometimes it still hurt. Like right now, when he was reliving the whole damn nightmare because he had nothing to occupy his thoughts.

He’d picked up a paperback novel at the gift shop earlier, some highly touted thriller, but it hadn’t been able to hold his attention. Either J. W. Killeen was losing his touch or Hardy Wingate just didn’t have the brainpower left to focus on it.

So he sat there holding his mother’s hand, trying not to think about how frail it felt, trying not to think about Karen Wingate and that hellish night twelve years ago. But trying not to think about things only seemed to make him think about them more.

Or maybe it was talking to Joni Matlock earlier in the cafeteria that was making him think so much about Karen. Back in high school, when he’d been dating Karen, he’d gotten to know Joni because the girls were close. But since Karen’s death…well, he hadn’t had a whole lot to do with the Matlocks since then.

And even in a small town like this, it was possible to avoid people if you really wanted to. Right after the accident, he’d gone away to college. By the time he got back, Joni had gone away to school, and since her return three years ago, the most he’d seen of her was across the width of the supermarket or Main Street. Which suited him fine.

But then today, out of the clear blue, she’d come up to him while he was having coffee in the cafeteria and had joined him. What had possessed the woman? She knew what her uncle thought of him. And she must have noticed that he’d been working on avoiding her. Hell, the reason the width of the street was always between them was that he was perfectly willing to cross the damn thing to get away when he saw her coming.

Then, like nothing in the world had ever happened, she plopped down with him at the cafeteria table. Weird. And he’d been within two seconds of jumping up and walking away when she’d asked about his mother.

Now, he couldn’t ignore that. He couldn’t be rude in the face of that kind of politeness. His mother had raised him better than that. So he’d been stuck, and he’d had to talk to her.

And all the time he’d been itching to get away. He supposed it was stupid, after all this time, but he didn’t want any more trouble with Witt Matlock. That man hated him.

Well, why the hell not? He hated himself.

He froze suddenly, his heart stopping in his chest as he realized that his mother was no longer breathing. Caught in a vise of fear, he lifted his gaze to her face. Then, just as he was reaching for the call button, she drew a long, ragged breath. Then another. The tortured tempos of life resumed.

He waited breathlessly for a long time, but Barbara seemed to have taken a firm grasp on life once more. The tightness in his chest eased a little, but as it did, he felt the burn of unshed tears in his eyes.

“Hang in there,” he heard himself tell her in a rough whisper. “Hang in there, Mom.”

Even as he spoke the encouragement, he wondered why. Maybe she was as tired of it all as he sometimes felt. As he felt right now. Sometimes it just didn’t seem worth the effort.

But he wasn’t ready to lose her yet. He probably never would be, but she was only fifty, and he figured he shouldn’t have to be losing her for a good long while yet.

As soon as he had the thought, bitterness rose in him, burning his throat like bile. Karen had been too young, too. Only seventeen. Life and death didn’t care about things like youth.

But Barbara kept breathing, difficult though it was, and the heart monitor kept recording her steady, too-rapid beats. He watched the lambda waves form on the display, one after another in perfect rhythm, checked the digital readouts and saw that her blood pressure was steady, her pulse a constant eighty-five. Too fast, but strong. Strong enough. Not like it had been with Karen.

For a few seconds he was suddenly back in the ICU twelve years ago, watching the monitor, all too aware despite his lack of knowledge that the ragged pattern of Karen’s heartbeats wasn’t a good sign. Aware that the rattling unsteadiness of her breathing was terrible. Aware that those low numbers on the blood pressure monitors were dangerous.

Aware that no one was doing anything for her just then. Wondering why, ready to go grab someone and demand they help her. Sensing that they had done all they could.

Then Witt had come into the cubicle behind him.

“Get out!”

He jerked, as if the words had been spoken behind him right now instead of twelve years ago. He came back to the present with the feeling of someone who had just taken a long, rough journey. His heart was pounding, and his face was damp with sweat. God!

There was a rustle, and the curtain was pulled back. Delia Patterson entered, giving him a slight smile and a nod as she approached the bed. She checked the IV and made a note on a clipboard.

“How is she?”

Delia, a slightly plump woman with the champagne-blond hair that a lot of older women adopted to cover the gray, looked at him. She’d known Hardy all his life. “You can see for yourself.”

“Delia…”

She shook her head. “I can’t make any promises. And I’m not the doctor. But…” She hesitated. “We might see some difference by morning. Maybe. The doctor put her on some pretty powerful antibiotics, Hardy. But no one can say for sure, understand?”

He nodded, hating the uncertainty. He’d always hated uncertainty, but life seemed to deal out very little else.

“You staying all night?” she asked.

“I plan to.”

“That waiting-room couch is mighty hard.” She glanced at her watch. “And you’ve been in here longer than the allowed ten minutes.”

“For God’s sake, I’m just sitting here holding her hand.”

She nodded. “Okay, I’ll give you another ten.”

“Thanks.”

On the way out the door she paused and laid her hand on his shoulder. “If she’s more alert in the morning, she’s going to need you then, Hardy. You might consider getting some serious sleep tonight.”

“I want to be here. In case.”

She nodded. “But I can call you if…anything changes. You could be here in ten minutes.”

“That might be too many minutes. Thanks, Delia, but I’m staying.”

“And probably catching pneumonia, too.” She shook her head. “We’re overflowing into the hallways. Have you been immunized?”

“Who, me?”

She shook her head, muttered something and walked out. Hardy felt a faint smile curling the corners of his mouth, but it faded as he turned back to his mother. She was fighting for her life, and if she could summon the energy to do that, then he could damn well stick it out with her.

After ten more minutes Delia kept her word and banished him to the ICU waiting room. Much to his relief, there were only two other people there. Given Delia’s description of patients overflowing into the halls, he’d figured the waiting rooms would be getting full, too.

There was one couch. It didn’t look too healthy, as if it hadn’t been cleaned in a long time, and it didn’t offer any extra padding for comfort. In fact, he thought minutes after he’d stretched out on it, the floor was probably more comfortable.

So what? He could handle it for forty minutes until Delia would be obliged to let him back into the ICU.

But as soon as he closed his eyes, Joni Matlock filled his mind’s eye. Everything was determined to torture him, it seemed. There couldn’t be a worse possible time to start thinking about the Matlocks. Thinking about Joni inevitably led him to thinking about Karen, and tonight he didn’t want to remember how the best medical treatment in the world hadn’t been able to save Karen, not with his mother at death’s door.

But good time, bad time, right time, wrong time, it didn’t make a bit of difference. His thoughts wouldn’t leave him alone, and they seemed bound and determined to focus on Joni.

Okay, he told himself. Think about Joni. Think about her until you’re bored and your mind decides to go somewhere else.

So he thought over their conversation earlier. It had been brief. He figured she’d picked up on the fact that he really didn’t want to talk to her. She’d been polite, concerned the way any stranger would be. Nothing more. Nothing to get all bent about.

Except that he couldn’t forget those blue eyes of hers. It wasn’t just that they were pretty, though they certainly were. It wasn’t just that they were as arrestingly blue as a clear mountain-morning sky. It was the way they seemed to speak to him. They’d only talked for three minutes, if that, but when he’d walked away, he’d had the feeling they’d shared an entire subtext, her eyes to his.

But those eyes had always made him feel that way. They’d always drawn him and spoken to him. If life had treated them all differently, he might have gotten to know her better. Instead, he avoided her the way he avoided Witt. Because some things were better left buried, and there was no way he could talk to Joni Matlock without remembering Karen Matlock.

As easy as that, his thoughts turned on him and began to twist into dark corridors. Swearing under his breath, he sat upright and forced himself to remember where he was. He had to stop beating himself up over the past. He knew that. It was done, and he couldn’t change any of it.

But when it got dark, on nights when he couldn’t sleep, he could still hear Karen’s scream as the other car swerved straight at him, could still remember her screams as they lay in the mangled wreckage of his car. Could still remember Witt looking at him out of cold, dead eyes and saying, “You killed her, boy. You killed her.”

The sounds and smells of the ICU had brought it all back to the surface, bubbling up like explosive gases in the swamp of his brain. His hold on the present, he realized, was getting mighty tenuous.

Shoving himself to his feet, he went out into the brightly lighted corridor to pace. But that, too, was familiar, and he realized with a sickening plunge of his stomach that yesterday and today were starting to fuse in his weary brain. He wasn’t sure from one minute to the next which year it was and who was lying in the ICU near death.

God, he thought he’d gotten over the worst of this a few years ago, but now here it was again, rearing up to bite him on the butt. He deserved it; he knew that. But deserving this kind of torture didn’t mean he had to like it.

He passed his hand over his face, trying to wipe away the images that seemed to be dancing at the edges of his vision, horrific images that were burned forever into his mind. Feeling desperate, he glanced at his watch and realized it was only two minutes until they would let him in to see Barbara one last time before they shut down visiting hours for the night.

Stupid, he thought. Family members ought to be able to visit patients in the ICU round the clock. What difference did it make if it was midnight, 2:00 a.m. or 8:00 a.m?

But they were strict about it, and he didn’t want to squawk too loudly right now, especially since he’d been pushing the limits all day and the nurses had been letting him.

He was standing right outside the ICU door when Delia opened it.

“Last call,” she said, pursing her lips. “Ten minutes and you’re outta here, Hardy. Then you’re going to go home and get some sleep. With this pneumonia going around, we ain’t got no room for exhaustion cases.”

He gave her a wan smile and made his way to the cubicle where his mother lay. No change. At once relief and disappointment filled him, but he reminded himself that he’d been told not to expect a miracle. Morning. He’d been told again and again that she might be better in the morning. It was so hard to believe right now, though, as he stood at her bedside, holding her hand gently and murmuring nonsense to her.

Ten minutes later, when he was evicted, nothing had changed. He had the panicky feeling that his mother was slipping slowly away from him, so slowly that it was almost undetectable. And he couldn’t really blame her.

Life had been hard on her for a long time. First there had been his drunken bum of a father. Then, when Lester had left, there had been the two jobs she worked to keep Hardy and herself clothed and sheltered. She’d even continued working two jobs so he could go to college. Then she’d helped him start his construction firm, working the endless hours right beside him as they built the business. Now that things were finally going good, it seemed somehow so unreasonably unfair that she should be at death’s door.

But maybe she’d had enough. He could hardly blame her. He knew he hadn’t lived up to her dreams for him. There was the accident with Karen’s death, which had certainly hurt her, too, and then his refusal to date anyone, though she kept encouraging him to. She wanted grandbabies, she said, but he couldn’t bear the thought of caring like that again.

So maybe she was just fed up. Her life had been one major disappointment after another.

And the thoughts running through his brain were doing nothing at all to ease his panic.

When he stepped blindly out of the ICU, he bumped into someone. It took him a moment to recognize Joni. “What are you doing here?” he demanded roughly. It was a question he had no right to ask, and he realized it almost as soon as the words came out of his mouth.

But she didn’t take it amiss. “I was worrying about you and your mother. How is she?”

“Pretty bad,” he admitted reluctantly. “We probably won’t know anything till morning.”

“I’m sorry.”

He gave her a short nod.

She reached out tentatively and touched his forearm briefly. “Let me buy you a cocoa?”

He looked down at her and shook his head. “Joni, you’re courting disaster. You know what Witt thinks of me.”

“Yeah. But I happen to disagree, and I’m over twenty-one. Cocoa?”

“The cafeteria’s closed.”

She gave him a wink that made him feel strangely light-headed. Lack of sleep, he told himself.

“Hey,” she said, grabbing his hand, “I work here, remember? I know where the good stuff is hidden.”

She took him away from the ICU toward the reception area, then steered him through a door that said Employees Only.

Inside was a staff lounge. A nurse was sitting on an easy chair with her shoes kicked off, eating a snack. A man in scrubs was stretched out on a couch with a cushion over his face.

Joni waved at the nurse, then put her finger over her lips as she looked at Hardy and pointed to the sleeping man. He nodded.

She made two mugs of instant cocoa, passed him one, then indicated he should follow her. They left the lounge and went to sit in the reception area.

“See?” she said. “Insider knowledge.”

“Thanks.” He hoped it didn’t sound as grudging as it felt, because the cocoa was hot and delicious and contained the first calories he’d put in his system since a sandwich at noon.

“You look awful,” she told him.

She hadn’t changed a bit, he realized. She was still the mouthy fourteen-year-old who’d pestered the living bejesus out of him and Karen sometimes. Even back then, he’d tried to be understanding. A kid who’d lost her daddy and moved to a town that didn’t easily make room for new arrivals—yeah, she’d had a reason to be a pest. Everybody else in the world had kind of ignored her.

“Have you slept within recent memory?” she asked.

“I’ve dozed here and there. Don’t give me hell, Joni. I’m not up for it.”

“Okay.” She sipped her cocoa and looked at him from those amazing blue eyes.

“Don’t you need to get home and get some sleep yourself?”

She shrugged. “I’m not on duty tomorrow. Day off.”

“Even with the epidemic?”

“I might be called in,” she admitted.

“Then go get some sleep.”

“Are you trying to get rid of me?”

They stared at each other, letting her words hang in the air between them. Neither of them wanted to mention Karen, he realized, but she lay between them as surely as if she were there.

“I’m trying to keep you out of trouble with your uncle,” he said finally.

“My problem, not yours.”

He cocked an eye at her. “What put you in such a feisty mood?”

“I don’t know. Maybe it’s realizing that age doesn’t necessarily make a person wise.”

He sipped his cocoa, wondering what she was getting at, and almost afraid to ask. He didn’t know Joni at all anymore, he reminded himself. Since Karen’s death, until today, they hadn’t passed more than a dozen words.

“Can you keep a secret?” she asked finally.

“Sure. But you shouldn’t be telling them to me.”

“I’ve got a reason.”

She always had a reason. He remembered that from way back when. According to Joni, she never did a thing without good reason. He had his own thoughts about that.

“Witt won the lottery,” she told him. “But don’t tell anyone else.”

“Yeah?” He felt a mild interest. “That’s neat. You all going to take a vacation in Hawaii?” His mother had always wanted to do that. It pained him that he hadn’t yet been able to make that dream come true for her. This year, he promised himself. Somehow, if she made it through this pneumonia, he was going to get her to Hawaii, if he had to move heaven and earth.

“I suggested Tahiti.” She gave him a smile that struck him as uneasy and sad. Despite all his overwhelming emotional exhaustion because of the last twenty-four desperate hours, he still managed to feel a pang for Joni.

“What’s wrong?”

“Not a thing,” she said. “It’s a lot of money.”

“Well, that’s a good thing,” he said generously. “Witt’s worked hard in the mine all his life. You can’t begrudge him an early retirement.”

“I’d never do that. No, I’m really pleased for him.”

“So, is he going to Tahiti?”

She shook her head. “No.”

“Seems a shame. But maybe it wasn’t enough for the trip.”

She looked at him sideways. “How about eleven million dollars?”

That set him back on his heels. Numbers like that were usually attached to major construction jobs, none of which he’d so far managed to garner for his company. “Wow,” he said after a moment. “Wow. But it doesn’t pay out in a lump sum.”

“No, but even with the payout schedule it’s a lot of money.”

“I guess he will retire.”

“Actually…” She hesitated. “He’s thinking about a career change.”

“That’s cool.” Like he cared.

“He’s…um…thinking about building a resort on that property he owns west of town.”

And suddenly Hardy understood why she was mentioning this to him. He looked straight at her and felt the entire world hold its breath for a few seconds. Then he said slowly, “Joni…are you sure you know what you’re doing?”

Her mouth tightened, and she looked away. When she faced him again, her eyes were moist. “When Karen died, I didn’t just lose my best friend. I lost my other best friend, too.”

In spite of himself, he felt his throat tighten a little, and he cleared it. “Joni…”

She shook her head, silencing him. “It’s been twelve years, Hardy. Twelve years! And ever since we talked this afternoon, I’ve been thinking about how much Witt’s anger has cost me. And you, too. Karen would never have had to sneak out with you that night if Witt hadn’t thought you weren’t good enough for her. And you and I could still have been friends except for Witt. Damn it, Hardy, it’s not right. And Karen had the guts not to let it keep her away from you. Maybe I’ve got the same guts, finally.”

“Joni…Joni, it’s not a matter of guts. It’s a matter of not raking up a whole lot of…unpleasantness. Not at this late date. After all this time, Witt’s not going to change his mind about me. It’ll just open old wounds for everyone.”

“Maybe they need to be opened.” A tear spilled down her cheek. “This money’s a bad thing, Hardy. I’ve been feeling it ever since Witt told me about it. The only way to avoid the bad things is to turn it to some good. You could build that lodge better than anybody.”

“You don’t know that. There’s no way you can know that.”

“I believe it.”

He knew what she was offering him. Witt would never, ever, have asked him to bid on the project, would never even have let him know it was up for bid. But if he could just give Witt the best bid…maybe he’d get the job anyway. And it was exactly the kind of job he knew how to do, the kind of job he was constantly looking for. It could benefit them both.

He shook his head. “Witt will never agree, no matter how good the bid is.”

“I have some influence, Hardy.”

“That may be. But you don’t want to get crosswise with your uncle, Joni. He and your mom are the only family you have.”

“Well, you do what you think best. But I’ll tell you right now, the next time you cross a street when you see me coming, I’m going to cross it, too.” She drew a tremulous breath. “It’s like…it’s like I can feel Karen telling me to do this. I know that’s crazy, but it’s what I feel. I’m not going to let Witt tell me who I can be friends with anymore. And neither should you.”

He looked at her, wondering if she were getting sick or slipping a cog. All this time… Yeah, all this time. He suddenly remembered that it hadn’t been Joni who’d been avoiding him. No, he’d been the one avoiding her. Because of Witt. Because he was scared to look into that abyss yet again. Because he’d managed to put his guilt on the back burner finally, and getting involved with the Matlocks was only going to make him face it all over again.

He closed his eyes, the memories surging in him, filling him with blackness. “It won’t work, Joni.”

“You don’t know until you try.”

He did know, though. He knew in his deepest heart that Witt would never give him the job. But he also knew in his deepest heart that he wouldn’t be able to live with himself if he didn’t try.

Why, he wondered, did nearly every damn thing in his life have to be just beyond his grasp? It seemed to him that life had always been teasing and tantalizing him with promises it snatched away before they were barely fulfilled. And, God, he hoped his mother wasn’t another one of them.

When he looked at Joni again, his eyes felt swollen and hot, and his heart hurt almost too much to bear. “What’s the point? It won’t happen.”

“Maybe, maybe not,” she said. “But you’ll never know if you don’t try.”

A great philosophy, but words were cheap. Hardy had absolutely no doubt that he was going to find himself disappointed once again.

But what the hell, he thought. After a while you got used to being kicked.

But all that faded away at four-thirty in the morning when Barbara Wingate awoke, her fever gone and her gaze once again aware.

So maybe, Hardy thought gratefully, you didn’t always have to get kicked.

It was a thought that kept him smiling the rest of the day.

3

Wind whipped the snow into a whiteness that erased the world as Joni drove home from work on a chilly January afternoon. A blizzard was moving through the mountains, and she was beginning to wonder if she’d stayed a little too late at the hospital. She didn’t have all that far to drive, though, and she reminded herself that she would be driving through this kind of weather at least a dozen more times before winter blew its last white breath over the Colorado Rockies. Heck, some years she drove through this until June.

It was two days after New Year’s, and she was feeling as good as it was possible to feel in the wake of the holidays. She wondered if she would have her usual letdown or if she was finally old enough not to get so high on anticipation that she would inevitably crash after New Year’s.

Probably not, she decided. Nor was she sure she really wanted to outgrow the magical, excited feeling that always preceded Christmas for her.

When she got home and had left her outerwear in the mudroom, she went to find her mother. Hannah was sitting in the living room, reading.

“Miserable out there,” she remarked to her daughter. “Did you have trouble getting up the hill?”

“No. But I wouldn’t want to try it in an hour.” The stack of mail was on the table by the door, and she flipped through it, pulling out her credit card bill and the utility bill that she paid as part of her share of the household costs. Then she came to a thick manila envelope that wasn’t addressed to anyone.

“What’s this?” she asked.

“Witt left it. He said it’s the request for bids he had a lawyer draw up.” Hannah smiled. “He was as excited as a kid. Apparently he’s sent a bunch of them out to firms in Denver, and now he can’t wait for the replies.”

“So why did we get a copy?”

Hannah laughed. “I think he wanted to show off a little.”

Witt liked to show off for her mother, Joni thought. She often wondered why the two of them had never gotten together. They were both widowed, after all. But…sometimes she sensed there was an invisible wall between them. Some kind of barrier the two refused to cross.

Silly, she told herself. She was imagining things. “I guess he won’t mind if I look at it.”

“I guess he was hoping you might,” Hannah replied. “Witt’s like any other man. He wants to hear how brilliant he is.”

The statement carried the warmth of affection, and Joni laughed. She tucked the envelope under her arm and headed upstairs.

“Trust me,” Hannah called after her, “it’ll put you to sleep.”

But Joni had other thoughts in mind, and she eagerly pried the envelope open when she reached her room. A stapled stack of papers came out, and a quick scan told her most of it was boilerplate, establishing rules such as how the bid should be presented. But there was a specification, too, one that she was able to determine required an architectural proposal for a thirty-room lodge. The other details didn’t matter to her. What did matter was the due date on the request: January tenth.

She was jolted by the nearness of the date. Witt must have sent these out early last month or even in November to the firms in Denver. They would need at least a month to respond.

The due date was only a week away. And Hardy probably hadn’t even seen this yet.

She checked the date again to be sure she wasn’t mistaken. This was fast, awfully fast, but maybe it had to be, so construction could start as early as possible in the spring.

But why had it taken Witt so long to drop this copy off for her mother? Had he deliberately done this so it wouldn’t fall into Hardy’s hands? But why would he even suspect it would? No, it must be that he’d only now gotten a spare copy from his attorney.

Eight days. If Hardy was to have any chance of responding to this, she had to get the papers to him right away.

But even as she jumped up from the bed, ready to dash out into the blizzard once more, a thought yanked her back. If she did this, Witt might never forgive her.

Her pulse racing, she flopped onto the bed and stared at the cracked ceiling, thinking about that. It was all well and good to believe that Witt ought to forgive Hardy. The police had blamed the drunk driver for the accident, and Joni couldn’t understand why Witt persisted in believing Hardy was responsible—except that Hardy wasn’t supposed to be seeing Karen, and if Karen hadn’t climbed out the window that July night, she would probably still be alive.

But Karen was dead, and Witt honestly believed that Hardy was responsible. There was, she supposed, a possibility that Witt was right. Maybe he knew something about what had happened that she didn’t. But it was more likely, she believed, that he simply needed a scapegoat, and since the drunk driver hadn’t survived the accident, Hardy was the only person left to blame.

Taking this proposal over to Hardy would be seen as a betrayal. Witt might never forgive her. But then she decided that was ridiculous. Witt always forgave her. He would be mad, sure, but he would forgive her once she explained.

Explained. It occurred to her that maybe she’d better be able to explain this to herself before she tried to explain it to Witt. Common sense dictated that she just stay out of this. It wasn’t her problem, nor was it her feud—as Hardy had made patently clear since their talk that night at the hospital. He was still avoiding her like the plague.

But it was her problem, she decided. She loved Witt, and she liked Hardy. It pained her that Witt had carried such anger all this time. It meant that he wasn’t healing.

Karen would want her to do this. She believed that in her soul. They’d been like sisters, especially after Joni moved to town, sharing everything—their hopes, dreams and feelings. Sharing Witt as a father, and Hannah as a mother. Sharing Hardy’s friendship, although only Karen had dated him.

Karen wouldn’t like to see her father so bitter and angry, and she wouldn’t like Hardy to miss this opportunity. There was not a doubt of that in Joni’s mind. Karen, had she been here, never would have allowed this state of affairs to continue for so long.

But Karen wasn’t here, and Witt was. She hated to have Witt angry with her and always had. She loved him so much that she wanted to be perfect for him, although it was an impossible goal.

And sometimes, dimly, she realized that she’d spent the last twelve years trying to replace his daughter for him. Maybe it was time to grow up and accept that she couldn’t replace Karen, and that she had to live her own life as she saw fit.

Sitting up, she went to the closet and pulled out a small photo album she kept on a shelf beneath a stack of sweatshirts. Almost all the pages were empty, but that was because she only had a half-dozen photos of Karen.

Oh, Witt had shoe boxes full of pictures of his daughter, but these photos were special. These photos had been hers and hers alone, taken with a cheap camera that hadn’t lasted beyond a couple rolls of film. In retrospect, she wished she’d photographed Karen more often, instead of wasting film on scenery. But she hadn’t guessed what was going to happen.

So here they were, her six private memories of Karen. The first snapshot, her favorite, showed her and Karen sitting on the bleachers at the high school football field. They had both laughed and acted silly that afternoon at football practice, full of the high spirits and joy of youth. Hardy had snapped that photo of them just before practice had started. She could still remember how he had looked all suited up for the game, holding her silly little camera in his big hands.

The next photo, one she would never, ever let Witt see, was of Hardy and Karen. Snow was falling, and the flash had bounced off it, giving the couple in the photo a dim, background look. But they were holding each other, hugging, their faces pressed close as they grinned into the camera.

Where the first picture always made her smile in memory, this one always made her ache.

They had been so young. So sure that the world was their oyster. All of them. And maybe it had been, only instead of finding pearls they’d all found lumps of coal.

Her throat suddenly tight, Joni closed the album without looking any farther. She knew the photos by heart, anyway. She’d wept over them on enough cold, dark nights, lying up here, unable to believe that Karen was truly gone.

There was such a feeling of unfinished business, but not just for Karen, who had died. Lately she had been thinking that they’d all somehow gone into stasis since Karen’s death. As if they were in some kind of emotional suspended animation. All of them: Witt, who had never recovered from his grief; Hannah, who…who just seemed to be getting through the days. Herself, who always felt as if she was just marking time. And Hardy, who, as far as she could tell, hadn’t even dated.

They were all unfinished lives, and for so long none of them seemed to have taken any real steps to move forward emotionally.

Karen wouldn’t have liked that. And it was time, Joni decided with a stiffening of her shoulders, that someone pushed them past their frozen emotional states.

Scooping up the request for bids, she tucked it under her baggy green Shaker sweater and set out on her personal mission to thaw the glacier that had swallowed them all.

“Where are you going?” Hannah asked as Joni passed her in the living room. “Supper’s almost ready.”

“I won’t be long,” Joni replied, not even breaking step. “I just need to run over to…Sally’s. Back in a sec.”

“Be careful out there. It’s getting really bad.”

No kidding, Joni thought after she’d tugged on her parka, hat, mittens and boots, and stepped outside. It had been bad enough when she’d come home from work, but now the wind was blowing so hard that ice crystals stung her face, and the street lamp two houses down was nothing but a glow in the snowhidden night.

If she’d had to go either up- or downhill to get to Hardy’s house, she would have stopped right there. But he lived three blocks over on a cross street, a level run. She could make it.

The night was mysterious and threatening, the whipping snow hiding the landmarks, making the world look unfamiliar. Leaning into the wind, squinting against the stinging snow, she slipped and slid down the drifting street. The sidewalks, caught as they were between two deep snowbanks, were already filled with the snow they caught, and the going was easier on the street. There was no traffic at all to give her any problems.

It was so lonely out here. There was something about being out in the middle of a snowstorm alone that left her feeling cut off and solitary to her very soul. The little bits of warm light that reached her from the street lamps and the glow from nearby windows only made her feel lonelier somehow.

She’d always felt this way on cold wintry nights, walking down darkened streets with no other soul in evidence, but tonight was even worse than usual, as if all the empty places in her heart were filled with a cold, whistling wind she couldn’t ignore. Nor could she shrug off the feeling.

Hardy’s house was just another one of the small Victorians lining the streets in this part of town, but unlike the rest, his was a showplace renovated through his own hard work and skill.

Even back in high school, Hardy had loved to work with his hands and with wood. He’d replaced the gingerbread on the house during those years, spending painstaking hours in the school shop, because he didn’t have the tools at home, whenever he didn’t have to work. Karen had spent a lot of those hours with him, watching him, admiring his growing skill. Occasionally Joni had joined them.

But since Hardy had come back from college, he’d transformed the exterior, getting rid of the ugly aluminum siding and replacing it with wood, hanging new shutters, rebuilding the huge porch. She imagined he’d done a lot of work on the inside, too, but she didn’t know, because she’d never been invited in, not since Karen’s death.

At the foot of the porch steps, she hesitated, forgetting the snow that sliced at her cheeks. This was nuts, and she didn’t delude herself about it. Hardy might tell her she was crazy, to get lost. Sometimes she wondered if he agreed with Witt’s opinion of him.

Then there was Witt. He would forgive her. Maybe. He certainly hadn’t been able to forgive Hardy all these years. But she was different, she told herself. She was his niece. His brother’s daughter. He couldn’t possibly treat her the same way he had treated Hardy.

That was what she told herself, anyway. She was well aware that she didn’t believe it one hundred percent as she climbed the steps and finally rang Hardy’s bell.

A minute passed before the door opened. Hardy stood there in stocking feet, looking rumpled in jeans and a gray sweatshirt with the sleeves pushed up.

“Joni?” he said as if he couldn’t believe his eyes. “What the hell are you doing here?”

It wasn’t exactly a warm welcome, but Joni hadn’t expected one, not the way things were. But she wasn’t doing this for herself, or even for Hardy, really. She was doing it for Karen.

Before she could formulate a response, the wind ripped around the corner of his house, splattering her face with ice needles.

“Damn,” he said under his breath and reached out, taking her arm and pulling her inside. He closed the door behind her, shutting out the bitter night.

“Thanks,” she murmured, her thoughts scattering as she got a look at the inside of Hardy Wingate’s house.

Polished wood greeted her everywhere, from the original plank floors to the polished stair railing rising to the second floor. Colorful old rugs were scattered around the foyer, and the walls were painted a creamy white. Through the door to the right she could see a living room filled with beautiful period pieces, and to the left was the dining room, with a long Queen Anne table and chairs.

“I didn’t know you liked antiques,” she blurted.

“These aren’t antiques,” he said almost impatiently. “I made them myself.”

She looked up at him. “When do you have time?”

He shrugged. “I’ve been doing this for years. Keeps me busy in the evenings. What do you want?”

He wasn’t even going to ask her to take her coat off, she realized. Not even a civilized, neighborly offer of something hot to drink before she left. She was, however, stubborn enough not to allow him to rush her. What she was about to do deserved at least that much consideration.

“How’s your mother?”

“Getting better. Still exhausted. She sleeps a lot. She’s sleeping right now. Did you want to see her?”

She could tell he doubted it, and she couldn’t blame him; she certainly hadn’t tried to come see Barbara in the last two months. “No,” she said slowly. “I came to see you.”

“Big mistake. Witt’ll have your hide.”

“Witt’s not entitled to my hide. I’m a grown woman.” She smothered her exasperation. “And it’s all irrelevant, anyway.” Shoving her hand up under her jacket, she tugged the envelope out from under her sweater and offered it to him. It was warm from her body. “Here. The request for bids on Witt’s lodge.”

Hardy hesitated, looking at the envelope as she held it out to him. “Joni…” He trailed off as if he didn’t know what to say.

“You’ve only got until the tenth to submit,” she said, thrusting it toward him. “I’m sorry I couldn’t give you more time, but I just got this today. You’ll have to hurry.”

He still didn’t take the envelope. He stared at it as if it might explode at any moment. Then, slowly, he dragged his gaze from it and looked straight at her. “Witt is going to kill one of us if I take that.”

She shrugged, all too aware that he was right. “I can handle it.”

“Joni, why are you doing this? Why?”

She looked down, studying the braid rug beneath her feet, watching the melting snow drip from her boot and disappear into the rug. “Karen would want me to.”

For the longest time Hardy didn’t say anything. He didn’t even move or seem to draw a breath. Just as she was about to look up at him, to make sure she hadn’t shocked him into a stroke or something, he spoke.

“Take your jacket and boots off,” he said roughly. “You need something hot to drink, and I’m boiling water for tea.”

“I need to get right home,” she said, mindful that Hannah would ask questions if she was gone too long. She wasn’t comfortable with the lie she had already told, and she didn’t want to have to tell too many more of them.

“You’ve got time enough for some tea. If you’re worried about your mother, call her.”

Hannah wasn’t the biggest part of her problem, Joni thought gloomily as she tugged off her boots and hung her jacket on the coat tree. Not by a long shot.

She followed Hardy into the kitchen, which was behind the dining room toward the back of the house. Here, too, loving care was displayed in a brick floor and gleaming modern appliances complemented by beautiful oak cabinets and tiled countertops. Hardy waved her to a round oak table.

“Earl Grey okay?” he asked.

“Great.” She wasn’t much of a tea connoisseur, and she would have been content with ordinary old orange and black pekoe.

Hardy brought two steaming mugs to the table, both dangling tags over the side. “Sugar? Cream? Lemon?”

“Black’s fine.”

Apparently he felt the same, because he sat across from her, dipping his tea bag absently while he studied her. “Karen’s been gone a long time,” he remarked. “I doubt any of us could know what she’d want.”

“She’d want for her dad not to be so angry and bitter,” Joni said firmly.

“And me submitting a bid is going to change his mind?” The question was full of disbelief.

“If you submit a good one, it might force him to face how unfair he’s been to you.”

“Are you so sure that he’s been unfair?”

The question jolted Joni. What was he talking about? The cops had said the accident wasn’t his fault. The other driver had steered right into them and Hardy hadn’t been able to evade him. “It wasn’t your fault,” she said urgently.

“Maybe not.” He dragged his eyes away from her and looked toward a corner of the kitchen. “And maybe it was. The point is, Joni, nobody except me really knows what happened that night. I can’t blame Witt for thinking I should have done more. I think about that a lot myself.”

Horror gripped her like vines of ice around her heart. “No, Hardy.”

“Yes, Hardy,” he said almost mockingly. He looked at her. “I’ve replayed those thirty seconds in my mind so many times, and I keep reaching the same conclusion. I didn’t have enough experience at the wheel. Maybe I should have sped up instead of slowing down. Maybe I could have spun the wheel more. Maybe if I’d known that drunk drivers steer right into lights I would’ve had the presence of mind to turn mine off. Maybe I should have gone left instead of right. I can think of a dozen things I could have done differently. Maybe the outcome would have been different.”

He leaned forward, his gaze burning into her. “And if I can think that, why shouldn’t Witt? I don’t blame him for how he feels.”

She hated to think of Hardy feeling this way. “Hindsight’s always twenty-twenty.”

“No it’s not,” he said harshly. “It just asks a lot of pointless questions. But this isn’t getting us anywhere. I can’t bid on this project. I’d just be wasting my time.”

“You don’t know that.” Anger began to burn in her.

“And you don’t know that Witt might have a change of heart.”

“You don’t know that he won’t. My uncle isn’t a stupid man, Hardy. He wants to build the best lodge he can afford. He doesn’t want it to be second-rate, or fail because it isn’t attractive enough.”

“And he can get any one of a dozen decent architects and general contractors anywhere between Denver and Glenwood Springs.”

“He said he’s doing this to make jobs for local people.”

Hardy shook his head in exasperation. “Noble intent, but I’m sure he’s not thinking of me as local people. Christ, Joni, you still go off half-cocked, don’t you?”

Another time she might have bristled, but right now she didn’t want to argue with him. It would only make it easier for him to refuse to bid. “I’m not going off half-cocked. I’ve been thinking about this for months now.”

He just looked at her.

“Hardy, it’s time for this to end.”

His eyebrows lowered, and something in his jaw set. “Have you considered that you’re proposing to pick at one very large scab? That if you keep this up, someone may well wind up bleeding?”

“It’s been twelve years,” she said. It sounded like a mantra, even to her. “Enough is enough. Don’t chicken out, Hardy.”

She tossed the envelope on the table and rose, ignoring her tea. But before she could reach the kitchen door, his voice stopped her.

“How are you going to explain to Witt that you don’t have your copy of the bid package?”

She shrugged, refusing to look at him.

“Jesus H. Christ,” he said under his breath. “Drink your damn tea. I’ll make a copy of it.”

She faced him then. “You’re going to bid?”

“No, I’m going to save your altruistic butt.” Snatching up the envelope, he disappeared into the back of the house, where his office was. Moments later, she heard the sound of a photocopier warming up.

He was going to bid, she told herself. There would be no reason for him to make a copy otherwise.

But even as she lied to herself, she knew she was doing it. He was just making sure she didn’t have any excuse to leave without her copy of the request for bids.

He was taking care of her again, the way he’d always tried to in the old days. Part of her wanted to resent it, and part of her was touched that he still cared enough to do it, even after all these long years.

A few minutes later he returned with two sheafs of papers. One was her copy, carefully restapled at the corner. The other, unstapled, was clearly his copy.

“There,” he said, returning hers. “Look, this isn’t some kind of morality attack, is it?”

Confused, she looked at him. “Morality?”

“Yeah. You’re not on some moral high horse, thinking that you’re going to teach us all to be better people, are you?”

“No. God no! I’m not that conceited.”

“No?” He put his palms on the table and leaned toward her, looking straight at her. “Then what is this, Joni? Are you saying our feelings aren’t valid? That Witt doesn’t have a right to be angry with me? That I don’t have a right to feel it’s better to avoid the man?”

She felt hurt, because she didn’t at all like the way he seemed to be seeing her. Her eyes started stinging, and her throat tightened up. Pressing her lips together, she snatched up the envelope, stuffed the papers into it and headed for the door, picking up her jacket as she went.

“Joni…”

She didn’t want to look at him, but something made her turn around anyway. “I think…I think I’m ashamed of my behavior,” she said thickly. “I think I’ve let Karen down. You and I were friends, Hardy. We were friends.”

Hardy stood at his open door, watching her dash down the street. Not until she stopped and pulled on her jacket did he close the door.

Damn her, he thought almost savagely. Damn her eyes. What was she doing, shaking all this old stuff out of the woodwork at this late date? What was she hoping to accomplish? Did she think some miracle was going to occur if he entered his bid? Did she think Witt was going to forget all his anger and bitterness just because Hardy Wingate could build a better hotel?

Not bloody likely.

“Shit!” He swore under his breath so his mother wouldn’t be disturbed. He could almost hate Joni right now. She’d dangled a plum under his nose, something he would have given his eyeteeth to do, something that would have put him in a position to take his mother to Hawaii.

And considering that Barbara wasn’t doing well at all, he desperately wanted to give her that trip. Since her pneumonia she’d been so frail, even needed a wheelchair some of the time. Her lungs had been damaged, leaving her breathless after even mild exertion. He needed to get her to a lower altitude, but she refused to go.

Swearing softly once more, he grabbed the bid packet from the table and went back to his office. A spacious two rooms he’d added to the house, it was like another world: gleaming real-wood paneling, wide picture windows looking out onto a snowy, night-darkened backyard, a freestanding fireplace. Worktables, model tables, drafting boards, two computers…

It was his eyrie. His escape. His dream-place. When he was here, he forgot everything except creating.

On the model table right now was the project he’d been working on for the last couple of months despite himself: a lodge for Witt Matlock. He had decided to fly in the face of the conventional for this one. Instead of following the Vail and Aspen trend toward Alpine looks in redwood and cedar, he’d chosen to carry the Victorian charm of Whisper Creek into the hotel. High spires, lots of gingerbread, a porch that wrapped around. Beautiful.

Lines that sang. A creation that deserved to be realized.

He stretched out his arm and prepared to knock the whole thing to the floor, to wipe out the insane dream that Joni had planted in his brain.

But he couldn’t bring himself to do it. Instead, he dropped onto a stool and simply sat staring at the model. Seeing it not as it was, but as it could be when finished. Somebody else could build it, he told himself. It didn’t have to be Witt. Some other investor would come along, especially if Witt built a lodge.

That was what Witt probably wanted. A long, low building, the rustic log-cabin type. A male sort of retreat. That would be like Witt, to want something of that kind, not this Victorian froufrou.

But he knew he was lying to himself. He was lying to himself about a lot of things, and had been for many years. It was a poor excuse, realizing that deluding himself was the only way he could remain sane.

Squeezing his eyes shut, he clenched his fists and wondered why he couldn’t just keep on pretending. Wondered why Joni had suddenly decided she had to take action when this whole mess had been carefully buried years ago.

Did she suspect? he wondered. Had she always suspected at some unconscious level? And if Joni had, had Karen? And maybe Witt?

It was something he’d never really admitted to himself, and sometimes, over the past twelve years, he’d managed to convince himself he was imagining the whole thing.

But the heavy weight of guilt in his heart didn’t let him fool himself that easily. It wouldn’t let him forget for long.

The night he’d taken Karen out, the night she’d been killed…he’d begun thinking about breaking up with her.

Because he’d just started to realize that he was falling for someone else.

And that someone else had been Joni.

4

The drive to Denver took nearly four hours, even with the high speed limit on the interstate highway. Witt was impatient all the way, and glad of Hannah’s company to keep him distracted.

“I still don’t understand why you want me to come with you,” Hannah said as they were at last traveling through the suburbs, passing the Westminster exits.