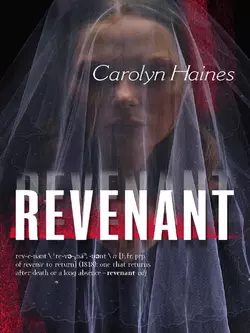

Revenant

Carolyn Haines

When a decades-old mass grave near a notorious Biloxi nightclub is unearthed, reporter Carson Lynch is among the first on the scene. The remains of five women lie within, each one buried with a bridal veil– and without her ring finger. Once an award-winning journalist, Carson knows her career is now hanging by a thread. This story has pulled her out of a pit of alcohol and self-loathing, and with justice and redemption in mind she begins to investigate.Days later two more bodies appear, begging the question– is a copycat murderer terrorizing Biloxi, or has a serial killer awoken from a twenty-five-year slumber?

Carolyn Haines

REVENANT

For Alice Jackson—

We had some fun when the Mississippi

Gulf Coast was a reporter’s dream.

Contents

Acknowledgments

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I can never write about newspapers and journalists without thanking my parents, who drew me into the profession they loved. When I was so small I had to stand on a wooden box, I disassembled the slugs of hot type to be melted and reset for the next edition of the paper.

My parents, Roy and Hilda Haines, burned with the passion of true journalists, and they passed that love to me.

In my life I’ve been privileged to know many fine reporters and editors. The Sellers family in Lucedale gave me my first paid job at a weekly at the age of seventeen. Leonard Lowry, Fitz McCoy, Elliot Chase, Sarah Gillespie, Robert Miller, Fallon Trotter, John Fay, Buddy Smith, Rhee Odom, Tom Roper, Gary Smith, Ann Hebert, Jim Young, Doug Sease, Bill Minor, Elaine Povich, Ronni Patriquin Clark, Jim Tuten, Lee Roop, B. J. Richey, Phil Smith—each one of them helped me down the road toward becoming a better reporter and also helped me recognize my limitations.

Newspapering gave me opportunities that few young people ever see. I owe the people I worked with many thanks.

As always, I owe thanks to my critique group, the Deep South Writers Salon: Renee Paul, Alice Jackson, Susan Tanner, Stephanie Chisholm, Gary and Shannon Walker and Aleta Boudreaux.

My agent, Marian Young, is the best. And the editorial staff at MIRA can’t be beat. Thank you, Lara Hyde, Valerie Gray and Sasha Bogin.

I’m knocked over by the terrific cover and the hard work that Erin Craig put into creating a design that conveyed so much of the story. This book has been a terrific experience from beginning to end.

Thank you all.

1

A seagull swooped low over the white, man-made beach of Biloxi. The midmorning sun was bright, and I squinted against the glare of the sparkling Mississippi Sound. The water held potential. An accidental drowning wouldn’t be a bad way to go, and it would be so much easier on my parents than suicide. My BlackBerry buzzed against my waist, disrupting the constant whisper of the water, the promises of numbness and sleep. I turned back to my truck and checked the number. The newspaper. I was late again.

A discarded coin cup clattered across the parking lot. Casinos, the new Mississippi cash crop. The Gulf Coast was second only to Las Vegas for gaming, a point of pride for those who saw growth as the only indication of progress. The garish casinos, complete with parking garages and hotels, were a blight, built by people who’d forgotten a storm called Camille and the damage of two-hundred-mile-per-hour winds. Talk about a gamble—putting huge floating barges in the Mississippi Sound. It was 2005, and thirty-six years had passed since Hurricane Camille wiped out the Gulf Coast. But Mother Nature, like a guilty conscience, only feigns sleep.

Of course, mine was the minority opinion in a town that had finally seen the promise of two cars in every garage fulfilled by the economic boost brought by the lure of the one-armed bandits.

It was only March, but already the hurricane experts were predicting a bad year for 2005. In a different place and time, I might have wanted to see the list of construction materials used on the hotels and new condominiums that crowded the coastline. If the construction was not up to standards, a Category Five hurricane, like Camille, could be death and destruction. In the past, that would have caught my professional interest, but not anymore. I was done with all of that.

I drove to the newsroom of the Morning Sun, ignoring the hostile glances of my coworkers as I went into my office and closed the door. They’d converted a conference room to make my office and indentations from the heavy table were still in the carpet. My desk and computer were at the end of the room beside the long narrow window that reminded me of a fortress. If the Injuns, or the liberals, surrounded us, I’d have a place for my shotgun. The paper’s policy would be to shoot on sight.

My telephone rang. “Where the hell have you been? It’s almost ten o’clock. We’re running a daily newspaper here, Carson, not a magazine.”

In my three weeks of employment, nothing had happened that warranted my presence at the paper at eight. “Sorry, Brandon,” I said. “I was busy contemplating suicide, but I’m too much of a coward to carry through with it. So, what’s going on?” I fumbled through a desk drawer for an aspirin bottle. Perhaps I should have apologized to Brandon Prescott, the publisher, but I didn’t care for him or my job.

“Drop the pity party, Carson. We don’t have time for it. They’re bulldozing the Gold Rush. When they started scraping up the parking lot they found a grave with five bodies in it. It’s the biggest story of the decade. Joey’s already there. I want you over there right now. And what the hell good is that pager unless you turn it on!”

Brandon was steamed, but there was always something that had his blood pressure at the boiling point. Lately, it was me, his prize. He’d dragged me out of the gutter and put me in a suit and an office with an official press badge. If I were a better person, I’d be grateful.

“I’m on the way,” I said, surprised at the tingle at the base of my skull. My reptilian brain felt a surge. Five bodies buried at one of the most glamorous—and notorious—nightclubs along the Gulf Coast. It could be a big story. In the ’70s and ’80s, the Gold Rush had been the pre-casino gathering place of the Dixie Mafia and the late-night party place where the young and beautiful of all social strata came to be seen. It was even possible someone had pushed up the tarmac and uncovered Jimmy Hoffa. After all, it was the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Anything was not only possible, but it was also probable.

I walked out of my office and was met with the baleful glares of six reporters. They already knew about the bodies, and they’d been hoping it would be their story. By rights, it should have belonged to one of them. But I had the big name and I got the choicest scraps Brandon tossed. I walked out into the March sunshine, hoping the bodies were either very old or very fresh.

Once upon a time, driving along the Mississippi Gulf Coast had been a pleasure. Miles of lazy, four-lane Highway 90 hugged the beaches where there were more migratory birds than fat sunbathers. With the advent of gambling in 1992, all of that changed. Sunbathers were already on the beach, even though the March sun had barely warmed the water above sixty degrees. For at least a mile ahead the traffic was almost at a standstill. If I didn’t get to the Gold Rush soon, the bodies would be bagged and moved. In an effort to calm down, I turned my radio to a country oldies station. There was always a chance I’d catch a Rosanne Cash tune.

Instead, I got Garth Brooks and “The Dance.” There had been a time when I agreed with the sentiment expressed in the song. I’d changed. There were very few experiences worth the pain. I flipped off the radio and took a deep breath. Traffic started moving, and in another fifteen minutes I was at the club.

Police cars and coroner vans lined the sandy shoulder of the highway, lights no longer flashing. Clusters of men in uniform stood whispering. Biloxi Police Department Deputy Chief Jimmy Riley sat behind the tinted windows of an unmarked car. It would have to be a big case for Riley to put in an appearance.

Mitch Rayburn, the district attorney, was also on the scene, and I’d made it a point to know as much as possible about him. Mitch was smart and ambitious, a man dedicated to protecting his community. There’d been tragedy in his past, but I didn’t know the exact details. Yet. What I saw was a man sincere about distributing justice. So far, he seemed to play a straight hand, which would be a definite detriment to his future political ambitions.

Detective Avery Boudreaux did everything but stomp his foot when he saw me pull up. Avery disliked reporters in general and me in particular. We’d already had a run-in over a stabbing at a local high school.

“Hi, Avery,” I said, because I knew he’d rather swallow nails than talk to me. “I’ll bet the bulldozer operator was shocked.” I started toward the edge of the shallow grave and heard Avery bark an order to stop.

“Let her go,” Mitch said. “We’re going to need the newspaper’s cooperation.”

I almost turned around in shock; Mitch was being amazingly cooperative. Then I figured the crime scene had already been molested by a bulldozer. I could hardly do more damage. The area was at the far back corner of the lot. Stumps and the damaged stalks of vegetation indicated that it had once been a shady, secluded spot.

I looked down into the grave. It was my lucky day. There was no flesh left, only smooth, white bones. Delicate in the bright sun. Five skeletons, five rib cages, five spinal columns embedded in dirt. All of the skulls were intact, the pelvises riding over femurs and tibias. They’d been laid side by side with some gentleness, it seemed. The connective tissue in the joints had disintegrated, so when the bodies were moved, they would fall to pieces. Whoever had buried the bodies had assumed the asphalt would protect them, and they’d been right, for a good number of years.

I caught Joey’s eye. He was standing about twenty feet back with his digital Nikon dangling from his hand. He nodded. I stepped in front of Avery, effectively blocking him. Joey rushed forward and fired off several shots before two cops grabbed him.

“Damn it, Mitch.” Avery thrust me to the side. “I told you we couldn’t trust her!”

“It’s better to let the public know,” I said. “Speculation is far worse than knowledge.”

“Except for the families of the victims.” Avery’s mouth was a thin line. “I should arrest both of you.”

I didn’t let his words register. Brandon Prescott ran a newspaper that thirsted for sensationalism. I knew my job, and even when I didn’t like it, I knew how to do it. There was very little of my old life that I’d held on to, but I was a damn good journalist. I got the story.

“Any idea who the bodies might be?” I directed my question to Mitch. He waved at the cops to release Joey. The photographer dashed for his car to get back to the office.

“Not yet,” Mitch answered.

“Wouldn’t you know, they were just so inconsiderate. They didn’t carry any identification into the grave with them. Can you believe it?” Avery glared at me.

“That’s a great quote, Avery,” I said. “Very professional.”

“That’s enough, both of you.” Mitch’s mouth was a tight line. “There are five dead people here. Let’s focus on what’s important. Avery, we need to cooperate with Carson. We’re not going to be able to keep the media out of this.” He pointed to the highway where a television news truck had stopped. “That’s our real problem.”

“Do you have any idea who the victims are?” I asked Avery again, this time in a more civil tone.

“As soon as we get the medical examiner to give us a time frame for the deaths, we’ll start going through missing-person reports.” Avery was watching the television news crew as he talked.

“When we know something, we’ll call you, Carson,” Mitch promised. “I’d personally appreciate it if you didn’t run the photo of the remains.”

He’d effectively ripped my sails. The photo was needlessly graphic, and he knew I knew it. I hadn’t been in Biloxi long, but Mitch had grown up here. He knew the score. “Talk to Brandon,” I said. “You know I don’t have a say in what gets printed and what doesn’t. Have something good to offer in exchange.”

“We wouldn’t have to negotiate with Prescott if you hadn’t set it up for the photographer.” Avery shook his head in disgust.

“Who owns the Gold Rush now?” I watched the television reporter being held at the edge of the parking lot. My time was running out.

“Alvin Orley sold it to Harrah’s about five years ago,” Mitch said. “It’s been empty for about that long. I think the casino corporation is going to build a parking garage here.”

“Lovely. More concrete.” I looked around at the oak trees that lined the property. With the bulldozers already at work, they were history. “Never let a two-hundred-year-old oak stand in the way of more parking space.”

“Why in the hell did you come back here if Miami was such a paradise?” Avery asked.

I looked him dead in the eye. “I guess when my daughter burned to death and I fell into a haze of alcoholic guilt, wrecked my marriage and got fired, I thought maybe I should leave the scene of my crimes and come home to Mississippi. Biloxi was the only paper that would hire me.” Avery didn’t flinch, but he had the decency to drop his gaze to the ground.

“Alvin’s still doing time in Angola prison,” Mitch said, breaking the strained silence. “I want to personally ask him some questions. I’m going to talk to him this afternoon. You could ride with me, Carson.”

I felt the sting of tears. It had taken me more than two years after Annabelle’s death to be able to control my crying. Now I was about to lose it again because a D.A. stepped out of his professional skin and offered me a ride to a Louisiana prison. I was truly pathetic.

“Thanks. I’ll let you know.” I turned away and walked back to the shallow grave. The five skeletons were lying side by side, heads and feet in a row. I had no idea what had killed them, whether they were male or female, how old they were or why they’d been killed. For all of the things I didn’t know, I was relatively certain that they’d been murdered. The skeletons were perfect. Lying under the asphalt, they’d been safe from predators and animals that normally disturb skeletal remains. I knelt down beside the grave for a closer look.

Avery was watching me, alert to my possible theft of a femur or maybe a scapula. I examined the bones, stopping on the left hand of the first victim. I couldn’t be certain, but it seemed that a finger was missing. I looked at the next body and saw the same thing. Then again on the third, fourth and fifth.

“Hey, Avery,” I called. “The ring fingers are missing on all of them.”

He came to stand beside me, his black eyes assessing me, and not kindly. “We know,” he said. “And that’s something we’d like to keep out of the paper.”

I couldn’t keep a photograph from Brandon, but I could keep this information. At least for a day. “Okay,” I agreed, “until tomorrow. After that, I can’t promise.”

“The M.E. said the fingers were probably severed,” Avery said. “It might be our best clue for catching whoever did this.”

I nodded, still glancing at the bones. Something else caught my eye. Beside each skull were the remains of some kind of material, and beneath that, plastic hair combs. “Look at that,” I said. “Nobody wears hair combs like that anymore. What are the odds that all five bodies would have had combs?”

“These bodies have probably been here at least twenty years. I’ve got somebody checking records to see if we can find out when this parking lot was last paved.”

“You figure they’re all women?” I asked, feeling yet again the tingle at the base of my skull.

“If you jump to a conclusion, Ms. Lynch, please don’t put it in print. There are fools out there who believe what they read in the newspaper.”

“Thanks, Avery.” I was almost relieved to have him back to his normal snarly self.

“I’ll stop by and talk to Brandon,” Mitch said. “And you can decide if you want to ride to Angola with me. We could get there by three, back by seven or so.”

“Thanks. I’ll think about it.” When I glanced toward my truck, I saw that Riley had returned to his desk job. The forensics team had done its work and was bagging the bodies. I’d seen hundreds of the black, zippered bags, but they still left me feeling empty. Would the families of the victims find peace or more horror? I got in my truck and eased into the moving traffic jam that was the highway.

2

Instead of going to the paper, I detoured to city hall. Biloxi was an old sea town. Fishing was once the heart and soul of the settlement, and the preponderance of business development was right along the water on Highway 90 or on Pass Road, which paralleled the coast through two counties. The population was French, Spanish, Yugoslavian, German, Italian and Scotch-Irish with a smattering of Lebanese. The Vietnamese were the newcomers who had earned an uneasy place in the fishing industry. The population was predominantly Catholic, a fact that figured into how the gravy train of state funding was distributed for many years. With the power base situated in the Protestant delta, the Gulf Coast sucked hind tit. The casinos changed all of that. The coast now had the upper hand. King Cotton and the rich planter society of the delta were passé.

Highway 90 still had remnants of the gracious old coast I remembered. Live oaks sheltered white houses with gingerbread trim and green shutters. There was an air of serenity and welcome, of permanence. I drove through one such residential area and then turned onto Lemuse where city hall was located.

When I asked for the records of building permits issued in the 1980s, I discovered that Detective Boudreaux’s minion was one step ahead of me. A police officer had just copied those documents. They were right at hand, and I read with interest that a small addition had been built onto the Gold Rush in October 1981. The parking lot had also been expanded and paved. The five victims had to have been murdered prior to that. I had a place to begin looking and I sped back to the paper.

The newsroom had fallen into the noon slump. Only Jack Evans, a senior reporter, and Hank Richey, the city editor, were still at their desks, and I hoped they wouldn’t see me. They were journalists of the old school, and like me, they’d found themselves employed in an entertainment medium. I slunk past the newsroom to my office and was almost there when I heard Jack yell.

“What’s wrong, Carson? Vomit on your shirt?”

I couldn’t help but smile. Jack was awful, and I liked him for it.

“I just need a little nip from that bottle I keep in my desk.” It wasn’t a joke.

“How bad was it?”

I shook my head. “More strange than gruesome.”

“Mitch is talking to Brandon right this red-hot minute. I hear Joey got some good shots of the skeletons.” Jack grinned. “Mitch will have to trade his soul to keep Brandon from printing that.”

“I warned him.” I sat down on the edge of Jack’s desk. He was a medium-built guy with a head of white hair and a face that tattled all of his vices. In Miami I’d worked with a top-notch reporter who reminded me of Jack. We’d once rented a helicopter to cover some riots. It had been both harrowing and exhilarating.

“So, what did you see?” Jack asked, patting his empty shirt pocket where his Camels had once resided.

When I’d first started as a journalist, this was a game that had honed my eye. “Five skeletons, all uniform in size, buried side by side. I’d say they died around the same time because of the dirt and the decomposition, and also because the parking lot was paved in 1981.” I frowned, thinking. “There were hair combs beside each skull, which would indicate female gender.” I looked at Jack and decided to risk trusting him. “Not for Brandon to know, but their ring fingers were missing.”

“A trophy taker,” Jack said, leaning forward. “This is going to be a big story, Carson. If you play it right, you could climb back up on your career and ride out of this shit hole.” He shook his head, anticipating my question. “I’m too old. Nobody wants a sixty-year-old reporter. But you could do it.”

I felt the numbness start in my chest. My precious career. I stood up. “If I wanted a real career, I wouldn’t be in this dump.” I realized how cruel it was only after I’d walked away. Well, cruelty was my major talent these days.

I grabbed a notebook off my desk and headed to the newspaper morgue, a type of library where newspaper stories were clipped and filed. The murders had to occur before October 1981, so I started there with the intention of working backward through time. October 31, 1981. The front-page photo was of children dressed in Halloween costumes. It was still safe to trick-or-treat then.

Mingled with the newspaper headlines were my own personal memories. I’d been a junior at Leakesville High School that year. I’d met Michael Batson, the first boy I’d ever slept with. He had the gentlest touch and genuine kindness for all living creatures. Now he was a vet, married to Polly Stonecypher, a girl I remembered as pert and impertinent.

The microfiche whirled along the spool. It gave me a vague headache, but then again, it could have been the vodka from the night before. I stopped on a story about Alvin Orley, the former owner of the Gold Rush. He was handing over a scholarship check to the president of the local alumni group of the University of Mississippi. I calculated that was right before his involvement in the murder of Biloxi’s mayor. I noted the date on my pad.

Cranking the microfiche, I moved backward through October. It was at the end of September when I noticed the first photos of the hurricane. Deborah. It had been a Category Three with winds up to 130 miles per hour. She’d hit just west of Biloxi, coming up Gulfport Channel. Those with hurricane experience know it wasn’t the eye that got the worst of a storm, but the eastern edge of the eye wall. Biloxi had suffered. There were photos of boats in trees, houses collapsed, cars washed onto front porches. It had been a severe storm, but not a killer like Camille. In fact, there were only two reported deaths. I stared again at the story, my eyes feeling unnaturally dry.

The D.A.’s brother, Jeffrey Rayburn, and his new bride, Alana Williams Rayburn, had drowned in a boating accident September 19. The young couple had been headed to the Virgin Islands for a honeymoon when they’d been caught in Hurricane Deborah.

The boat had been found capsized off the barrier islands a week after the storm had passed. Neither body was recovered.

The mug shot of the bride showed a beautiful girl with a radiant smile and blond hair. Dark-haired, serious Jeffrey was the perfect contrast. They were a handsome couple.

In a later edition of the paper I discovered a photo of the funeral, matching steel-gray coffins surrounded by floral arrangements. The slug line Together In Death made me cringe. The newspaper had a long and glorious history of sensationalism. As I studied the photo more closely, I saw a young Mitch Rayburn standing between the coffins. I recognized the grief etched into his face, a man who’d lost everyone he loved. I understood how he’d become a champion for justice as he tried to balance the scales for others who’d suffered loss.

I turned my attention to another short story about the tragic drownings. There was a quote from Mitch, who said that radio contact with the boat had been lost during the storm. As soon as the weather had cleared, search-and-rescue teams went out, but they found only the damaged sailboat.

“The coast guard believes that Jeffrey and Alana were swept overboard and that the boat drifted until it hit some shallows,” Mitch had said. “I appreciate all of the efforts of the coast guard and the volunteers who helped. I can only say that I’d never seen my brother happier than he was the day he set sail with his new bride.”

On more than one occasion, my mother had accused me of being incapable of sympathizing with others, and maybe she was right. I felt little at the deaths of a newly married couple, but for Mitch, the one left behind to survive, I felt compassion. Survivor’s guilt would have ridden him like a poor horseman, gouging with spurs and biting with a whip. I knew what that felt like. I lived with it on an hourly basis. I wondered how Mitch managed to look so rested and drug free.

I pushed back my chair and paced the small room, consumed with a thirst for a drink. At last, I sat down and spooled the microfiche backward. Mid-September gave way to stories about the Labor Day weekend, and then I saw the front-page story in the September 3 edition. No Clues In Disappearance Of Fourth Coast Girl. I scanned the story, which was a simple recounting of all the things the police didn’t have—suspects, theories or physical evidence of what had happened to Sarah Weaver, nineteen, of d’Iberville, a small community on the back of Biloxi Bay, where fishermen had resided for generations. It was a tight community of mostly Catholics with family values and love of a good time. In 1981, the disappearance of a girl from the neighborhood would have been cause for great alarm.

What the police did know was that Sarah was a high school graduate who’d been going to night school at William Carey College on the coast to study nursing. She disappeared on a Friday night, the fourth such disappearance that summer. She’d been employed part-time at a local hamburger joint, a teen hangout along the coast. She was popular in high school and a good student.

There were several paragraphs about the panic along the coast. Fathers were driving their daughters to and from work or social events. The police had talked about a curfew, but it hadn’t been implemented yet. Two Keesler airmen had been picked up and questioned but released. Fear whispered down quiet, tree-lined streets and along country club drives. Even the trailer parks and brick row subdivisions were locking doors and windows. Someone was stalking and stealing the young girls of the Gulf Coast.

I studied Sarah’s picture. She had light eyes—gray or blue—that danced, and her smile was wide and open. Was she one of the bodies in the grave? I couldn’t imagine that such information would be any solace to her family. If they didn’t know she was dead, they could imagine her alive. She would be forty-three now, a woman still in her prime.

In my gut, I felt it was likely that she was the fourth victim. But who was the fifth? There’d been no other girls reported missing, at least not in the newspaper, prior to the paving of the Gold Rush parking lot. I’d go back and read more carefully, just in case I’d missed something.

I took down Sarah Weaver’s address and skipped to the beginning of the summer. It didn’t take me long, scrolling through June, to find Audrey Coxwell, the first girl to go missing, on June 29. This story was played much smaller. Audrey was eighteen and old enough to leave town if she wanted. She was a graduate of Biloxi High and a cheerleader. She was cute—a perky brunette.

Her parents had offered a reward for any information leading to her recovery. I noted their address.

In the days following Audrey’s disappearance, there was little mention of her in the paper. Young women left every day. She was forgotten. No trace had ever been found of her. The reward was never claimed.

On July 7, I found the second missing girl, Charlotte Kyle, twenty-two, the oldest victim so far. The high school photo of Charlotte showed a serious girl with sad eyes. She was one of five siblings, the oldest girl. She was working at JCPenney’s.

This story was on the front page, but it wasn’t yet linked to Audrey’s disappearance. The newspaper or the police hadn’t considered the possibility of a serial killer on the loose. This was 1981, a time far more innocent than the new millennium.

I scanned through the rest of July. It was August before I found Maria Lopez, a sixteen-year-old beauty who looked older than her age. In her yearbook photo she was laughing, white teeth flashing and a hint of mischief in her dark eyes. There was also a picture of her mother, on her knees on the sidewalk, hands clutched to her chest, crying.

My hand trembled as I put it over the photo. I could still remember the feel of the strong hands on my arms, dragging me away from my house. My legs had collapsed, and I’d fallen to my knees inside my front door. A falling timber and a gust of heat had knocked me backward, and the firemen had grabbed me, dragging me back. I’d fought them. I’d cursed and kicked and screamed. And I’d lost.

The door of the newspaper morgue creaked open a little and Jack stood there, a cup of coffee in his hand. “I put a splash of whiskey in it,” he said, walking in and handing it to me. He closed the door behind him. “Everyone knows you drink, Carson, and they also know you haven’t contributed a dime to the coffee kitty. The second offense is the one that will get you into trouble.”

He was kind enough not to comment as my shaking hand took the disposable cup. I sipped, letting the heat of the coffee and the warmth of the bourbon work their magic.

“Carson, if you’re not ready, tell Brandon. He’s invested enough in you that he won’t push you over the edge.”

“I can do this.” Right. I sounded as if I were sitting on an unbalanced washing machine.

“Okay, but remember, you have a choice.”

I started to say something biting about choices, but instead, I nodded my thanks. “Where’d you get the bourbon?”

“You aren’t the only one with a few dirty secrets.” He grinned. “What did you find?”

“Four missing girls, all in the summer of 1981, before the parking lot was paved.”

“And the fifth?”

“I don’t know. Maybe she was killed somewhere else and brought to Biloxi.”

“Maybe.” He put a hand on my shoulder. “Mitch wants to see you. He’s waiting in your office.”

I drained the cup. “Thanks.” By the time I made it out of the morgue and into the newsroom, I was walking without wobbling.

3

I studied the back of Mitch Rayburn’s head as I stood in my office doorway. He had thick, dark hair threaded with silver. By my calculation he was in his mid-forties, and he wore his age well. His tailored suit emphasized broad shoulders and a tapered waist. He worked out, and he jogged. I’d seen him around town late in the evenings when I’d be pulling into a bar. He used endorphins, and I used alcohol; we both had our crutches.

“Carson, don’t stand behind me staring,” he said.

“What gave me away?” I asked, walking around him to my desk. He had two things I like in men—a mustache and a compelling voice.

“Opium. It’s a distinctive scent.”

“If I’m ever stalking a D.A., I’ll remember to spray on something less identifiable.”

He stood up and smiled. “I’m ready to go to Angola. Want a ride?”

I shook my head. “I have some leads to work on here, but I’d appreciate an update when you get back.”

“I didn’t realize I was on the newspaper’s payroll.”

I laughed. “How did it go with Brandon?”

“He’s holding the photo, and thanks for not mentioning the missing fingers.”

“You’re welcome. I’m not always the bitch Avery thinks I am.”

“You got off on the wrong foot, and Avery has a long list of grievances with the paper that date back to the Paleozoic era. Give him a chance to know you. He likes Jack Evans.”

I plopped in my chair and motioned him to sit, too. “I went back in the morgue and found four missing girls from the summer of 1981.”

Mitch’s face paled. “I remember…” His voice faded and there was silence for a moment. “I was in law school that year.”

Beating around the bush was a waste of good time. “I read about your brother and his wife. I’m sorry.”

His gaze dropped to his knees. “Jeffrey was my protector. And Alana…she was so beautiful and kind.”

Loss is an open wound. The lightest touch causes intense pain. I understood this and knew not to linger. “I think four of those bodies in the grave belong to the girls who went missing. I just don’t know how the fifth body fits in.” I watched him for a reaction.

“I’d say you’re on the right track, but it would surely be a courtesy to the families if we had time to contact them before they read it in the newspaper.”

Brandon would print the names of the girls if there was even a remote chance I was right. Or even if I wasn’t. I thought of the repercussions. Twenty-odd years wouldn’t dull the pain of losing a child, and to suffer that erroneously would be terrible. “Okay, if you’ll let me know as soon as you get a positive ID on any of them.”

He nodded. “We’re trying to get dental records on two of the girls. There were fillings. And one had a broken leg. Of course, there’s always DNA, but that’s much slower.”

I noticed his use of the word girls. Mitch, too, believed they were the four girls who went missing in 1981 and one unknown body. “Okay, I’ll do the story as five unidentified bodies. Brandon will have my head if he finds out.”

“Not even Avery Boudreaux could torture the information out of me,” he said, rising. “Thanks for your cooperation, Carson.” He stared at me, an expression I couldn’t identify on his face. “I think we’ll work well together. I want that.”

I arched an eyebrow. “Just remember, nothing is free. My cooperation comes with a price. I’ll collect later.”

As soon as he cleared the newsroom, I picked up the phone and called Avery. I told him about the girls, and that I was voluntarily withholding the information for at least twenty-four hours. His astonishment was reward enough. I got a quote about the investigation and began to write the story.

It was after four when Hank finished editing my piece. I left the paper and headed to Camille’s, a bar on stilts that hung over the Sound. The original bar, named the Cross Current, had been destroyed by the tidal surge of Hurricane Camille. The owner had found pieces of his bar all up and down the coast, had collected them and rebuilt, naming the place to commemorate all that was lost in that storm.

The bar was almost empty. I took a seat and ordered a vodka martini. It was good, but Kip over at Lissa’s Lounge made a better one. There had been a bar in Miami, Somoza’s Corpse, that set the standard for martinis. Daniel, my ex-husband, had taught the bartender to make a dirty martini with just a hint of jalapeño that went down smooth and hot. The music had been salsa and rumba. My husband, with his Nicaraguan heritage, had been an excellent dancer. Still was.

A man in shorts with strong, tanned legs sat down next to me. His T-shirt touted Key West, and his weathered face spoke of a life on the water.

“Hi, my name’s George,” he said, an easy smile on his face. “Mind if I sit here?”

I did, but I needed a distraction from myself. “I’m Carson.”

“I run a charter out of here, some fishing, mostly sightseeing.”

I nodded and smiled, wondering how desperate he was. I hadn’t worn a lick of makeup in two years, and sorrow lined my face. I looked in a mirror often enough to know everything that was missing.

“I moved here in 1978, out of the Keys,” he said. “I don’t like the casinos, but they’re a good draw for business.”

“The coast has changed a lot since the casinos came in.” I didn’t want to make small talk, but I also didn’t want to be rude.

He settled in beside me. “I lost the Matilda in ’81. My first boat.”

Storms interested me, and the weather was a safe enough subject. “I was inland then. Was it bad?”

“Deborah hit Gulfport, but we got the worst here in Biloxi. The Matilda was tied up in the harbor. I had at least ten lines on her, plenty to let her ride the storm surge. Didn’t matter. Another boat broke free and rammed her. She took on water and sank right in the harbor.” He shook his head. “She was sweet.”

“I guess you had plenty of warning that the storm was coming. Why didn’t you take her inland?”

“It was a fluke. Deborah hit the Yucatan, lost a lot of power and looked like she was dying out, but she came back strong enough. I really thought the boats could weather it. Never again. I take mine upriver now. I don’t care if it’s a pissin’ rainstorm.”

“Was there much damage?”

“Washed out a section of Highway 90. Took a few of those oak trees.” He shook his head. “That hurt me. Funny, I’ve had a lot of loss in my life, but those trees made me cry.” He sipped his beer. “Life’s not fair, you know. I lost my wife two years ago to cancer. She was my mate, in more ways than one.”

I knew then what had drawn him to me. Loss. It was a law of nature that two losses attract. “My dad’s told me stories of storms that came in unannounced. At least now there’s adequate warning.”

He nodded. “We thought it was petering out. After it hit Mexico, it just drifted, not even a tropical storm. Looked like if it was going anywhere, it’d drift over to the Texas coast. Then, suddenly, it reorganized and roared this way. Caught a young couple on their honeymoon. The storm just caught ’em by surprise.” He looked at me. “Enough doom and gloom. Would you like to go out when I take a charter?” he asked.

To me, boats were floating prisons. I shook my head but forced a smile. “Thank you, but I’m not much for boats or water. I’m afraid you’d regret your invitation.”

“Then how about dinner?”

I hated this. How could I explain that I had no interest in the things that normal people did? “No, thank you.”

He looked into my eyes. “Sometimes it helps to be around other people.”

“Not this time,” I said, putting a twenty on the bar and gathering my purse. “Vodka helps. And sleeping pills.” I walked out before I could see the pity in his eyes.

It was dark outside and I got in my pickup and headed east on Highway 90. The stars in the clear sky were obliterated by mercury-vapor lights and neon. The coast was a smear of red, green, purple, pink, orange, yellow—a hot gas rainbow that blinked and flashed and promised something for nothing.

I drove past the Beau Rivage, the nearly completed Hard Rock casino, the Grand, Casino Magic and the Isle of Capri. Once I was on the Biloxi-Ocean Springs Bridge, I left the glitz behind. Ocean Springs was in another county, one that had refused to succumb to the lure of gambling. My house was on a quiet street, a small cottage surrounded by live oaks, a tall fence and a yard that sloped to a secluded curve of the Mississippi Sound. I’d forgotten to leave a light on, and I fumbled with my keys on the porch. Inside a strident meow let me know that I was in deep trouble.

The door swung open and a white cat with two tabby patches on her back, gray ears and a gray tail glared at me.

“Miss Vesta,” I said, trying to sound suitably contrite. “How was your day?”

A flash of yellow tabby churned out from under a chair and batted Vesta’s tail. She whirled, growling and spitting. So it had been one of those days. Chester, a younger cat, had been up to his tricks.

I went to the sunroom, examined the empty food bowl, replenished it and took a seat on the sofa so both cats could claim a little attention. They were as different in personality as night and day. Annabelle had loved them both, and it was my duty not to fail her. They were the last tangible connection I had to my daughter, except for Bilbo, the pony. Daniel hadn’t even tried to fight me for them when we divorced.

I thought about another drink, but I was pinned down by the cats. Today was Thursday, March 12, Bilbo’s birthday. He was twelve.

I wasn’t prepared for the full blast of the memory that hit. I closed my eyes. Annabelle’s hand tugged at my shirt. “Carrot cake,” she said, grinning, one front tooth missing. “We’ll make Bilbo a carrot cake. And he can wear a hat.” We’d spent the afternoon in the kitchen, baking. I’d made a carrot cake for Annabelle, and a pan of carrots with molasses for icing for Bilbo. Together we’d gone to the barn to celebrate. Daniel had come home early from his import/export business and had met us there, his laughter so warm that it felt like a touch. He’d brought a purple halter, Annabelle’s favorite color, for Bilbo, and it was hidden in a basket of apples.

Chester’s paw slapped my cheek. He was after the tears, chasing them along my skin.

I snapped on a light and got several small balls. The cats had learned to fetch. North of Miami, we’d had twenty acres for them to roam. When I moved to Ocean Springs, I decided to keep them inside, safe.

When the cats tired of the fetch game, I wandered the house. I’d painted the rooms, arranged the furniture, bought throw rugs for the hardwood floors, hung the paintings that I treasured, stored all the family photographs and stocked the pantry with food. It was the emptiest house I’d ever set foot in. When I’d first graduated from college and taken an apartment in Hattiesburg, I’d had a bed, an old trunk, some pillows that I used for chairs, a boom box and some cassettes, but the house had always been full of people.

The fireplace was laid, and I considered lighting it, but it really wasn’t cold, just a little chilly. The phone rang, and I picked it up without checking caller ID. It could only be work.

“Hey, Carson, I wanted to make sure that you’re coming home this weekend. Dad’s got the farrier lined up to do the horses’ feet.”

Dorry, my older sister, was about as subtle as a house falling on me. “I’ll be there. I already told Mom I would.”

There was a pause, in which she didn’t say that I’d become somewhat unreliable. “Today is Bilbo’s birthday,” I finally said. “I forgot.”

“We’ll celebrate Saturday,” she said softly. “He won’t know the difference of a few days.”

Dorry was the perfect daughter. She was everything my mother adored. “The horses need their spring vaccinations, too.” I sought common ground. “I’ll see about it. Dad shouldn’t be out there since he’s on Coumadin.”

“I know,” Dorry agreed. “Mom’s terrified he’ll get cut somewhere on the farm and bleed to death before she finds him.”

My father was the sole pharmacist in Leakesville, Mississippi. The drugstore there still had a soda fountain, and Dad compounded a lot of his own drugs. He was also seventy-one years old and took heart medicine that thinned his blood.

“I’ll take care of the horses. It’s enough that he feeds them every morning.”

“You know Dad. If he didn’t have the farm to fiddle around with, he’d die of boredom, so it’s six of one and half a dozen of the other.”

“Will you and Tommy and the kids be there Saturday?” I was hoping. When Dorry was there, my parents’ focus was on her and her family. She had four perfect children ranging from sixteen to nine. They were all geniuses with impeccable manners. Her husband, Dr. Tommy Prichard, was the catch of the century. Handsome, educated, a doctor who pulled off miracles, Tommy’s surgical skills kept him flying all over the country, but his base was a hospital in Mobile.

“I’ll be there. Tommy’s workload has tripled. He has to be in Mobile Saturday. I think the kids have social commitments.”

I was disappointed. I wanted to see Emily, Dorry’s daughter who was closest in age to Annabelle. “I’m glad you’ll be there.”

“Mom and Dad love you, Carson. They’re just worried.”

I couldn’t count the times Dorry had said that same thing to me. “I love them, too. I try not to worry them.”

“Good, then I’ll see you Saturday.”

The phone buzzed as she broke the connection. I took a sleeping pill and got ready for bed.

4

The ringing telephone dragged me from a medically induced sleep Friday morning. I ignored the noise, but I couldn’t ignore the cat walking on my full bladder. “Chester!” I grabbed him and pulled him against me. “Is someone paying you to torment me?”

He didn’t answer so I picked up the persistent phone and said hello.

“Where in the hell are you?” Brandon Prescott asked.

“In bed.” I knew it would aggravate him further.

“It’s eight o’clock,” Brandon said. “I believe that’s when you’re supposed to be in the office.”

“As I recall,” I answered, my own temper kindling, “when I took the job, we agreed there wouldn’t be rigid hours.”

“I expect you to be on time occasionally. That isn’t the issue. The newspaper has been swamped by families calling in, wondering if the unidentified bodies are someone they know. We need a follow-up story.”

In an effort to spare four families, I’d worried a lot of others.

Brandon continued. “I want you to go to Angola and talk to Alvin Orley. He might have an idea who the bodies are.”

“Mitch went yesterday. I’ll call him and do an interview.”

“He’s the D.A., Carson. That means he doesn’t want us to know what he found out.”

I gritted my teeth and said nothing.

“Besides, even if you get the same information, we can put it in a story. Quoting Rayburn about what Orley said diminishes the power. And the Orley interview will open the door for Jack to do a roundup of a lot of the old Dixie Mafia stories. It’ll be great. So head over to Angola. I got you a one-o’clock appointment with Orley. You can call in and dictate your story.”

I hung up and rolled out of bed. Hank would be righteously pissed off. Brandon was the publisher, but most of the time he acted like the executive, managing and city editor. He meted out assignments and orders, totally ignoring the men he’d hired to do the job. I called Hank at the desk and let him know where Brandon was sending me.

“I’ll call whenever I have something,” I told him.

“Jack’s already working on the old Mafia stories.” Hank’s voice held disgust. “Never miss a chance to drag up clichéd images from the past. We’re running an exceptional tabloid here.”

I made some coffee, dressed, ate some toast and headed down I-10 West toward New Orleans. Before I reached Slidell, I took I-12 up to Baton Rouge and then a two-lane north to St. Francisville and the prison.

Alvin Orley was serving twenty-five years on a murder charge in the slaying of Rocco Richaleux, the mayor of Biloxi at the time. Alvin didn’t actually pull the trigger, but he hired someone to do the job. He and Rocco had once been business partners in the Gold Rush and a number of other establishments that specialized in scantily clad women, booze, dope and gambling. Rocco’s political ambitions ended his affiliation with Alvin, and once elected, Rocco decided to clean up the coast, which meant his old buddy Alvin. Rocco ended up dead, and Alvin ended up doing time in Angola because the murder was carried out in New Orleans. It was a good thing, too. A jury of his peers in Biloxi might not have convicted him. Alvin had ties that went back to the bedrock roots of the Gulf Coast. And he was known to even a score.

Angola was at the end of a long, lonely road that wound through the Tunica Hills, a landscape of deep ravines that bordered the prison on three sides. Men had been known to step off into a hidden ravine and fall thirty feet. The steep hills were formed by an earthquake that created the current path of the Mississippi River, which was the fourth boundary of the prison. During its most notorious days, Angola was a playground for men of small intelligence and large cruelty. Inmates were released so that officers on horseback could chase them with bloodhounds. Manhunt was an apt description. But times had changed at Angola. It was now no better or worse than any other maximum-security prison.

I stopped at the gate. Angola was a series of single-story buildings. Decorative coils of concertina wire topped twelve-foot chain-link fencing. Hopelessness permeated the place. After my credentials were checked, I went inside to the administration building.

Deputy Warden Vance took me into an office where Alvin waited. He’d been in prison since he was convicted in 1983, more than twenty years ago. In the interim he’d lost his hair, his color, his vision and his body. He was a small, round dumpling of a man with a doughy complexion and Coke-bottle glasses. He sat behind a desk piled with papers. Two flies buzzed incessantly around him.

“I’ve read some of your articles in the Miami paper,” he said as I sat down across from him. “I’m flattered that such a star is interested in talking to me.”

“What do you know about the five bodies buried in the parking lot of your club?” I asked.

“Mitch Rayburn asked the same thing. Yesterday. You know I remember giving a check to an organization that helped put Mitch through law school. Isn’t that funny?”

Alvin’s eyes were distorted behind his glasses, giving him an unfocused look. I knew the stories about Alvin. It was said he liked to look at the people he hurt. Rocco was the exception.

“Mitch had a hard time of it, you know,” he continued, as if we were two old neighbors chewing the juicy fat of someone else’s misfortune. “He was just a kid when his folks died. They burned to death.” He watched me closely. “Then his brother drowned. I’d say if that boy didn’t have bad luck, he’d have no luck at all.” He laughed softly.

My impulse was to punch him, to split his pasty lips with his own teeth. “I found the building permits where a room was added to the Gold Rush in October of 1981,” I said instead. “The bodies were there before that. Sometime that summer. Do you remember any digging in the parking lot prior to the paving?”

“Mitch told me that it was the same summer all of those girls went missing,” Alvin said. “He believes those girls were buried in my parking lot after they were killed. Imagine that, those young girls lying dead there all these years.”

“Do you know anything about that?”

“No, I’m sorry to say I don’t. My involvement with girls was generally giving them a job in one of my clubs. It’s hard to get a dead girl to dance.” He laughed louder this time.

“Mr. Orley, I don’t believe that someone managed to get five bodies in the parking lot of your club without you noticing anything.” I tapped my pen on my notebook. “I was led to believe that you aren’t a stupid man.”

“I’m far too smart to let a has-been reporter bait me.” He laced his fingers across his stomach.

“You never noticed that someone had been digging in your parking lot?”

“Ms. Lynch, as I recall, we had to relay the sewage lines that year. Construction equipment everywhere, with the paving. I normally didn’t go to the Gold Rush until eight or nine o’clock in the evening. I left before dawn. I wasn’t in the habit of inspecting my parking lot. I paid off-duty police officers to patrol the lot, see unattended girls to their cars, that kind of thing. I had no reason to concern myself.”

“How would someone bury bodies there without being seen?”

“Back in the ’80s there were trees in the lot. The north portion was mostly a jungle. There was also an old outbuilding where we kept spare chairs and tables. If the bodies were buried on the north side of that, no one would be likely to see them. Mitch didn’t tell me exactly where the bodies were found.”

I wondered why not, but I didn’t volunteer the information. “The killer would have had to go back to that place at least five times. That’s risky.”

Orley shrugged. “Maybe not. On weeknights, things were pretty quiet at the Gold Rush, unless we had some of those girls from New Orleans coming in. Professional dancers, you know. Then—” he nodded, his lower lip protruding “—business was brisk. Especially if we had some of those fancy light-skinned Nigras.”

Alvin Orley made my skin crawl. “Do you remember seeing anyone hanging around the club that summer?”

“Hell, on busy nights there would be two hundred people in there. And if you want strange, just check out cokeheads and speed freaks, mostly little rich boys spending their daddy’s money. The lower-class customers were more interested in weed. If I kept a book of my customers, you’d have some mighty interesting reading.”

He was baiting me. “I’m sure, but since you have no evidence of these transactions, it would merely be gossip. I’m not interested in uncorroborated gossip.”

“But your publisher is.” He wheezed with amusement. “There was a man, now that I think about it. He was one of those Keesler fellows. Military posture, developed arms. He was in the club more than once that summer.”

“Did you ever mention it to the police?”

Orley laughed out loud, his belly and jowls shaking. “You think I just called them up and told them someone suspicious was hanging around in my club, would they please come right on down and investigate?”

Blood rushed into my cheeks. “Do you remember this man’s name?”

“We weren’t formally introduced.”

“I have some photographs of the young ladies who went missing that summer. Would you look at them and see if any are familiar?” I pulled them from my pocket and pushed them across the desk to him.

He stared at them, pointing to Maria Lopez. “Maybe her. Seems like I saw her at the club a time or two. I always had a yen for those hot-blooded spics.” He licked his lips and left a slimy sheen of saliva around his mouth. “Nobody gives head like a Spic.”

“Maria Lopez was sixteen.”

“Maybe her mother should’ve kept a closer eye on her and kept her at home.”

“Any of the others?” I asked.

He looked at them and shook his head. “I can’t really say. Back in the ’80s, the Gold Rush did a lot of business on the weekends. College girls looking for a good time, Back Bay girls looking for a husband, secretaries. They all came for the party.”

I stood up. “Why did you decide to pave the parking lot, Mr. Orley?” I asked.

“It was shell at the time. I was going to reshell it, but the price had gone up so much that I decided just to pave it.”

“Thank you,” I said.

“Be sure and come back, Ms. Lynch. I find your questions very stimulating.”

He was chuckling as I walked out in the hall where a guard was waiting. Alvin Orley’s conversation was troubling. If the parking lot was shell, it would have been obvious that someone had dug in it. Orley wasn’t blind, and he wasn’t stupid.

Once the prison was behind me, I tried to focus on the beauty of the day. Pale light with a greenish cast gave the trees a look of youth and promise. I stopped in St. Francisville for a late lunch at a small restaurant in one of the old plantations. It was a lovely place, surrounded by huge oaks draped with Spanish moss. Sunlight dappled the ground as it filtered through the live oak leaves, and the scent of early wisteria floated on the gentle breeze.

I was seated at one of several tables set up on a glassed-in front porch. I ordered iced tea and a salad. The accents of four women seated at a table beside me were pleasantly Southern. They talked of their husbands and homes. I glanced at them and saw they were about my age, but beautifully made up and dressed with care. Manicured fingernails flicked on expressive hands. Once, I’d polished my nails and streaked my dark blond hair with lighter strands.

“Oh, here comes Cornelia,” one woman exclaimed to a chorus of “Isn’t she lovely?”

I looked out the window and my heart stopped with screeching pain. A young girl with flowing dark hair skipped up the sidewalk. She wore blue jeans and a red shirt. For just one second, I thought it was Annabelle. My brain knew better, but my heart, that foolish organ, believed. I half rose from my chair. My hands reached out to the girl, who hadn’t noticed me.

The women beside me hushed. A fork clattered onto a plate. A woman got up and ran to the door as the young girl entered. She pulled her to her side and steered her away from me as she returned to her table.

I sat down, waited for my lungs to fill again, my heart to beat. When I thought I could walk, I left money on the table and fled.

I drove for a while, trying not to think or feel. At three o’clock I had no choice but to pull over, find a pay phone—because reception was too aggravating on my cell—and dictate my story back to the newspaper. Jack volunteered to take the dictation, and I was glad.

“I’ve got about thirty inches on Alvin Orley’s illegal activities,” he said as he waited for me to think a minute. “I even got an interview with one of his old dancers. She said most all of them had to have sex with him to keep their jobs.”

I gave him my story, the gist of which was that Alvin failed to notice his parking lot was dug up. It wasn’t much of a story, but it would be enough for Brandon.

“Hey, kid, are you okay?” Jack asked.

“Tell me about the fire that killed Mitch’s parents.”

“I forget that you didn’t grow up around here. I guess I remember it so well because at first blush everyone thought it was arson. Harry Rayburn was a prominent local attorney who defended a lot of scum. Everyone jumped to the conclusion that an unhappy client had set the fire.”

“It was an accident?”

“That’s right. Electrical.”

“Both parents died, but the boys escaped?”

“Mitch was just a kid, and he was on a Boy Scout campout. Jeffrey was at baseball camp at Mississippi State University. He was still in high school but scouts were already looking at him. From everything I heard, it was a real tragedy. The Rayburns were sort of a Beaver Cleaver family. Mrs. Rayburn was a stay-at-home mom.” He sighed. “The house went up like a torch.” He hesitated. “Sorry, Carson.”

“It’s okay,” I said. “I asked.”

“I covered it for the paper, and I was there when Jeffrey got home from State. He’d picked Mitch up at Camp DeSoto along the way. It broke my heart to see those boys standing by the smoking ruins of what had been their home.”

“You’re positive there was no sign of arson?” I could have read Alvin Orley wrong, but I thought he’d hinted that Mitch’s luck was bad for a reason.

“None. That fire was examined with a fine-tooth comb. It was accidental.”

“I’m headed back to Ocean Springs. Tell Hank to call me on my cell if he needs me.”

“Will do, Carson. Drive carefully.”

I was tempted to get off the interstate at Covington and revisit some of my old haunts. Dorry and I had both shown hunter-jumper. Covington, Louisiana, had hosted some of the finest shows of the local circuit. Dorry had always been the better rider; she rode for the gold. I was more timid, more worried about my horse. I smiled at the full-blown memory of both my admiration for, and my jealousy of, her.

When I went to visit my parents, I’d be able to see Mariah and Hooligan, our two horses, as well as Bilbo, the pony. Both horses were close to thirty now, but they were in good shape. Dad took excellent care of them, and Dorry’s daughter, Emily, groomed and exercised them. She was the only one of Dorry’s children who liked animals, and truthfully, the only one that I felt any kinship with. At twelve, she was only a year older than Annabelle would have been. Had we lived close together, I believed they would have been famous friends.

I checked my watch and stayed on the interstate. I’d spent enough time on memory lane. I needed to get back to Ocean Springs. There were a few loose ends I wanted to tie up before the weekend, and Mitch Rayburn was one of them. He’d promised to call. There was also the matter of the four missing girls. I’d have to run their names in Sunday’s paper, but it would look better for everyone if I could quote Mitch or Avery. I wrote leads in my head as I sped down the highway toward home.

Dark had fallen by the time I pulled into my driveway. My headlights illuminated the shells that served as paving. If someone buried even a rabbit under the shells, I’d notice that they’d been disturbed. Much less five human bodies. Alvin Orley was either blind or lying, and I was willing to bet on the latter.

The cats were glad to see me. The truth was, Daniel would have made a better home for them. It was my selfishness at wanting to cling to that last little piece of my daughter that had made me insist on keeping them. I fed them, and somewhat mollified, Vesta settled on my lap as I went through my phone messages. My mother had called twice, Dorry once, Daniel once and Mitch Rayburn once. I called Mitch back.

“We got a positive identification on the bodies. Or at least four of them. You were right, Carson.”

I took no pleasure in that. “We’ll run the story Sunday. Any idea who the fifth body might be?”

“Not yet. Did Orley tell you anything?”

“I didn’t find out squat except that Alvin Orley belongs in prison. He’s a vile man.”

“He still manipulates from behind prison bars,” Mitch cautioned. “He’s not a man to piss off.”

“Don’t worry, I try to keep my personal opinion out of print.”

He laughed. “Brandon must be bitterly disappointed.”

Mitch knew Brandon well, yet he didn’t let it bother him. “Did you find any leads to the girls’ killer?”

“The missing fingers. The hair combs. We have leads we’re pursuing.”

“I wonder why he stopped killing.”

Mitch hesitated. “That’s a good question. Maybe he moved on, found a new location.”

“Have you checked the MO with other locations?”

“Nothing so far, but this was twenty-odd years ago.” He sighed. “I’m going to go for a jog and hope that self-abuse will shake something loose in my brain.”

“Sweat some for me,” I said. “I’m going to listen to some country music and drink something with ice and olives in it.”

“You’re too classy for me, Carson,” he said, laughing as he hung up.

5

I took a long, hot bath, eventually realizing that I couldn’t scrub Alvin Orley off my skin or out of my consciousness. Contamination by proximity. He was like a virus, a nasty one. I dressed, opened a can of soup for dinner, then headed for the public beach.

In truth, it wasn’t much of a beach, just the eastern shore of the Bay of Biloxi. Front Beach Drive curved along the water, the homes of the wealthy perched like dignified old guards upon the embankment. Many were set back off the road, telling of a time when lawns were purchased with playing fields for children in mind. Huge oaks shaded the houses and the road. It was early for a Friday night, and the road was quiet. The city had cracked down on the teenagers who liked to park and party there. To the north, it was cocktail hour at the Oceans Springs Yacht Club, a Jim Walters-looking building on stilts. To the south, the water undulated to the Mississippi Sound, passed between Horn and Ship Islands and finally mingled with the waters of the Gulf of Mexico.

I sat on a low stone wall and listened to the shush of the water. Instead of being comforting, it was unsettling, and I took off my shoes and walked in the cold sand. March was warm enough to tempt the flowers out, but the wind off the water at night was still cool. The stars on this stretch of beach, undimmed by competition with the casinos, were brilliant. I walked for an hour, then got in my truck and headed for Highway 57 and the lonely road to Lissa’s Lounge, a honky-tonk of the old school.

When I was a child, the only points of interest along the highway had been a bridge over Bluff Creek where teenagers swam on hot summer days, the Home of Grace for alcoholic men and Dees General Store. Until the past ten years, most of the land in north Jackson County had been owned by the paper companies. Now there were subdivisions cropping up everywhere. The huge tracts of timber had been clear-cut one final time and sold to developers. Horseshoe-shaped subdivisions with names like Willow Bend and Shady Lane jutted up on treeless lots.

Along the interstate, a large tract of land had been claimed to preserve the sandhill crane, a prehistoric-looking bird that was near extinction. The rednecks resented the no-hunting rule in the preserve, so they regularly set fire to it. So far, the score was 2-0 in the birds’ favor. Last fall, two arsonists had drunk a bottle of Early Times and set a hot fire that swept out of control. They watched the blaze begin to chew through the woods and thought it was great fun, until the wind changed. Sayonara, motherfuckers.

Lissa’s was tucked back off the highway on Jim Ramsey Road. It was an old place where folks had come to dance and drink for decades. Lissa Albritton was in her sixties, but she didn’t look a day over forty-nine. She was at the door every Friday night taking a three-dollar cover charge and checking the men’s asses when they walked by. She was a connoisseur. “That man sure knows how to pack out some denim,” she’d say when she saw something that caught her fancy. If the man walked by close enough, she’d cop a feel.

There were plenty of classier bars in Ocean Springs and along the Gulf Coast, places where women wore black sheaths and pearls and men wore pinstripes and ties. The coast had a highly developed sheen of sophistication these days. That’s why I preferred Lissa’s.

The karaoke duo, the Bad Boys, was rocking the bar by the time I got there. They were twin brothers, Larry and Leon, in their fifties with professional voices and day jobs as mechanics.

Lissa waved me in. “No charge, Carson. They’ve been waiting for you.” Her blond hair was swept up and sprayed so righteously that not a strand dared to wilt. I pushed through the door and disappeared in a haze of cigarette smoke.

“Hey, Carson,” the bartender called out as I made my way to the bar. “Leon’s been looking for you. He has some requests for ‘Satin Sheets.’” He handed me a martini and a wink. “This one’s on me. You should have been a queen of country. Like Jeanne Pruette.”

Kip was a good guy and a primo bartender. Lissa knew his value and paid him well. I took my drink and found a table against the wall, letting the smoke and darkness fall over me like a cloak. I found a crushed pack of Marlboros in my purse and lit one. It was Friday night, my weekly nod to another of my vices.

The patrons at Lissa’s were evenly split between men and women. Everyone wore jeans. The thinner women wore tight shirts, often with some decorative cutout that strategically revealed an asset. The older, heavier women wore the same thing with a much different effect. The men were lean and muscular and often silent. They drank hard, danced hard and worked hard. I was willing to bet not a single one of them failed to sleep hard when they finally clocked out. I envied them that.

“Carson Lynch, report to the microphone.”

I finished my drink, signaled for another and went to the stage. Leon handed me the mike. “Satin Sheets” was an old classic, a song of too much money and not enough love. It wasn’t my theme song, but I admired the crafting. I sang it with heart, and when I got back to my table, there were two martinis waiting on me.

Leon sang a waltz and then a two-step and I watched the dancers. One middle-aged couple quartered the dance floor, each move synchronized. They stared into each other’s eyes as if no one else existed. I smoked another cigarette and sang “Take the Ribbon from My Hair” when Larry motioned me back to the stage.

Instead of a drink, there was a note at my table. “You’re four up in the credit department.” I smiled at Kip. He knew I had a long drive home.

“Care to dance?”

The man was tall and handsome. He wore a black cowboy hat and he had the confidence of that breed.

“I don’t dance,” I said.

“I can teach you.”

“Another time, maybe.” Dancing was part of another lifetime.

He put his hand on a chair. “Mind if I sit?”

I did and I didn’t. I liked men. I enjoyed talking with them, laughing with them. I especially liked confident men; they had the balls to charm. But it always came down to expectations, and I was always a disappointment.

“You can sit down, but I’m not dancing and I’m not going home with you.”

He smiled. “You sure I was going to ask?”

“No. I just don’t want a misunderstanding when liquor has clouded your memory or your judgment.”

We talked while I sipped my martinis and smoked three more cigarettes. His name was Sam Jackson, and he ran cows and grew hay above Saucier.

“I’ll bet you’re the only woman in here drinking a martini,” he said, sipping a Miller Lite. “You don’t really belong here.”

“I don’t really belong anywhere.” I ate the last olive.

“You sound like you’re from here, though.” He studied me. “We’ve talked about grass and cows and horses and weather. I don’t know anything about you.”

“I’m a reporter for the Biloxi newspaper.”

He put his beer down. “Working on a story?”

I shook my head. “I like Leon and Larry. I like this place. No one knows me and no one bothers me. Kip makes a martini just the way I like it.”

“I’ll make you a bet,” he said, leaning forward, a hint of a smile in his eyes. “I’ll bet you that eventually you dance with me.”

“How much?” I asked.

“Oh, just one dance,” he said. “Then if I don’t step on your toes, we might try it again.”

I couldn’t help but laugh. “How much do you bet?”

“I’ll bet you a day-long ride on a goin’ little mare when I move the cows in another few weeks.”

“How did you know I rode?” I asked.

“Same way I know you dance,” he said. He pushed back his chair, tipped his hat and left. I watched him for a moment as he was stopped by a redhead and led the way to the dance floor. He swung her into a two-step.

I collected my two remaining cigarettes and left. It was almost midnight. Time to go.

Clouds gathered in the south, and as I reached the truck, they rushed the moon. The night was suddenly black. I was glad for the darkness and the fact that no other cars were on the highway. I’d eaten very little all day, and I realized I was hungry. Carbohydrates. And fat. Maybe a chocolate shake, too. It would help prevent a hangover tomorrow. I drove over the Biloxi Bridge toward the glowing neon of gambler’s paradise. There was a Wendy’s that stayed open late.

I’d just picked up my order of a burger, fries and a shake when I heard the sirens. There were 137 law officers in the Biloxi PD. It sounded as if half of them were traveling at a high rate of speed down Highway 90. Blue lights sped by. I fell in behind them, hoping no one would question a black Ford pickup at the end of a caravan of squad cars.

They pulled into a lot beside the beach where earlier in the day tourists had sunned and swum. A public pier stretched out over the water, disappearing into the night. Police officers jumped from their vehicles and ran on the weathered boards, their footsteps pounding. I followed at a sedate walk. No one stopped me or asked any questions.

The pier was about a hundred yards long and was used primarily for fishing, although I wouldn’t eat anything caught so close to shore. Officers had high-beam flashlights and were searching the old boards. There was something else there, too. I could catch glimpses but not enough to get the whole picture.

“Put someone on the beach,” Avery Boudreaux called out. “Block everyone off. No one comes on this pier, you got it? No one. Particularly no media.”

“Yes, sir,” two officers said and headed in my direction.

I tucked my head and walked past them as if I belonged there. I kept walking. When I was close enough to catch a glimpse in an officer’s light, I stopped. My stomach coiled, threatening revolt. I took a deep breath.

“Shit!” Avery exclaimed as he came to stand beside me. “How in the hell did you get out here?”

“Just lucky, I guess.” My voice strained for control.

He took my elbow and steadied me. “Don’t you dare mess up my crime scene,” he said.

“I won’t,” I promised.

“And don’t go any closer!”

“I won’t.”

“Are you okay?”

I nodded.

“Stay out of the way and don’t move. Mitch will be here any minute. He can take care of you.” He released my arm and went to talk to two officers.

I stared at the dead girl. She slumped on a bench, blood pooling around her hips and slowly dripping onto the pier. She looked as if she was smiling, but it was a trick of death. The rictus of her face was a strange imitation of the slash that had opened her throat.

She was naked, except for the bridal veil that floated softly in the chill breeze.

6

Standing in the shadows, I leaned against the rail and listened to the water. Out here, away from the beach, it was calmer. A boat bobbed about a half mile offshore, the lights swaying with the gentle swells. I took some deep breaths and conjured up a mental image of the humiliation I’d suffer if I fainted or threw up. I’d seen death wear a number of faces, but this girl was so young. Her body bore the beginning of a summer tan. Bikini tan lines. A pretty blue-eyed blonde. Somebody’s baby girl.

The breeze off the water was steady, and it lifted the gossamer veil in lazy drafts. Lace fluttered against her pale face. It was a beautiful veil with a band of seed pearls forming the delicate headpiece.

The police officers were busy setting up portable lights. No doubt Avery was watching me, but I moved a little closer. When the floodlights came on, I was able to check the girl’s left hand. The ring finger had been severed. I turned away, horrified by what I finally understood.

Mitch arrived. He talked to the policeman working the sign-up sheet for all law-enforcement officers on the scene. He moved on to Avery, talking in a terse whisper. At last he came to me, his face registering only annoyance.

“How the hell did you get here?”

“I followed the squad cars. They hadn’t set up the perimeter yet.”

“Carson, this is strictly off-limits.” In the glare of the lighting two policemen had rigged, I could see the white around the corners of his mouth and nose.

His anger stabilized me. “Take it easy, Mitch. I couldn’t write anything until Sunday’s edition even if I wanted to. I’m not going to jeopardize your investigation. I want this person caught as badly as you do.”

“As you so succinctly put it, you don’t have control over what’s printed. Brandon Prescott rules that paper, and he doesn’t give a damn about this investigation.”

I couldn’t argue that. “I don’t tell Brandon everything and you know it. As long as I’m kept in the loop.” It wasn’t a threat; it was just a statement of fact. I’d worked well with the Miami PD. I often knew more than I printed, until the time was right. “I’ve figured out the hair combs,” I told him. “Bridal veils. They attached the veils to the victims’ hair. Those five dead bodies were buried with bridal veils.”

“I can’t believe this is happening.” He turned so that his profile was to me.

I noticed then that Mitch was sweating, and his pasty color had nothing to do with anger. He was deeply affected by the murder. “But why would someone kill four, probably five, women in 1981, stop for twenty-four years and then start killing again?” I spoke more to myself than Mitch, but my words made him look at me. “It’s because we found the bodies.” I saw that Mitch thought the same thing.

“We have to stop him,” he said.

“You’re assuming it’s a man, or do you have evidence?”

He hesitated. “That was an assumption.”

“An easy one to jump to,” I agreed. Women killed other women, but not often with the trappings of nudity and a bridal veil. Also, the killer would have had to be pretty strong to restrain a young woman and slice her throat so deeply with one stroke. I wasn’t a forensics expert, but it certainly looked like a clean stroke to me.

“The ring finger’s missing,” I said. “Jack says he’s a trophy taker.”

“Jack’s not a forensic profiler. I wouldn’t print that,” Mitch snapped.

“Okay,” I said. “I won’t print it. But what are the cops thinking?”

“We thought we were working a crime that was twenty-four years old,” Mitch said with a hint of bitterness. “Carson, I’d like to keep you in the loop, but I need to know that you’ll work with us. Even when it means holding out details.”

Brandon would skin me alive. That wasn’t so bad, but there were ethical considerations. Brandon paid me to do a job that included digging up facts that no one else had. A story that the police were looking at a killer who took fingers as trophies—and this killer was current, not some cold case from another century—was a big deal. I had to figure out my obligations. “There are people’s lives at risk here. My job is to keep the public informed.”

He took a long breath. “I know that, but panicking the public won’t protect anyone. In fact, printing too much detail could screw up our chances of catching this guy.”

“I don’t intend to do that.” There was a fine line to walk between informing the public and damaging an investigation, and it was a boundary that had to be redrawn with every case. The problem was that both the police and the newspaper wanted to be the one to draw it.

“And what does Brandon intend?”

It was a good question because we both knew the answer. A panic would be right up Brandon’s alley, especially if the Morning Sun was leading the charge. I didn’t say anything.

“If Brandon gets hold of the words serial killer, trophy taker or anything similar, it will be blown way out of proportion, and you know it.”

I wasn’t certain that the facts could be distorted to seem worse than they were. In all truth, however, I couldn’t argue Brandon’s reliability, or lack thereof. I shifted the topic. “Do you think this is a copycat killer or the original?”

He took another breath. “If I talk to you freely, will you promise to work with me?”

I nodded. “We’re off the record, until I say otherwise.”

“The detail of the missing fingers on the five corpses was never released to the other media. If this is a copycat, that person had privileged information.”

“Either the original killer, a police officer or—”

“You,” he said. There was no hint of teasing in his face. “See how easily facts can lead to an illogical conclusion?”