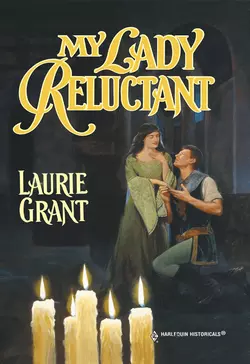

My Lady Reluctant

My Lady Reluctant

Laurie Grant

THESE WERE DANGEROUS TIMESAnd none knew it better than Brys de Balleroy as he played a deadly game in the service of his queen. 'Twas an honorable but lonely life, until the night the Lady Gisele stood naked and determined by his bedside !Gisele de L'Aigle would be no man's property, yet she'd brought upon herself the royal decree that would see her wed tot he Baron of Balleroy. And though her spirit rebelled, Brys had saved her from certain death, and roused her passion in a way no man had done before.

“If I could transform myself into a man this instant, I would do so,”

she snapped. “All my life I have been made to feel I had no value because I was a female. But worthless as I am, Brys, I care about you….” Her voice trailed off. Then Gisele almost jumped when she felt his hand touching her shoulder.

“And I for you, though I know you will not believe it, Gisele,” he said, his voice husky. “I have been fighting my desire for you ever since I found you in the Weald. But you didn’t want to become a wife, and I thought you deserved better than me.” He looked away, adding, “Yet I could not resist trying to seduce you in the garden. Damn me for a double-minded rogue.”

“Deserved better than you, my lord?” she asked, honestly puzzled. “Why on earth would you say that…?”

Dear Reader,

Welcome to Harlequin Historicals, Harlequin/Silhouette’s only historical romance line! We offer four unforgettable love stories each month, in a range of time periods, settings and sensuality. And they’re written by some of the best writers in the field!

We’re very excited to bring you My Lady Reluctant, a terrific new medieval novel by Laurie Grant. This book has something for everyone—intrigue, emotion, adventure and plenty of passion! Spurned by her betrothed and forced to find another husband, the heroine travels from Normandy to England to attend court. En route, she is attacked by outlaws but is rescued by a mysterious knight…who protects her by day and invades her dreams by night!

The Outlaw’s Bride by Liz Ireland is a fresh, charming Western about a reputed Texas outlaw and a headstrong “nurse” who fall in love—despite the odds against them. Deborah Simmons returns with a frothy new Regency romance, The Gentleman Thief, about a beautiful bluestocking who stirs up trouble when she investigates a jewel theft and finds herself scrutinizing—and falling for—an irresistible marquis.

And don’t miss Carolyn Davidson’s new Western, The Bachelor Tax. In this darling tale, a least-likely-to-marry “bad boy” rancher tries to avoid a local bachelor tax by proposing to the one woman he’s sure will turn him down—the prim preacher’s daughter….

Enjoy! And come back again next month for four more choices of the best in historical romance.

Sincerely,

Tracy Farrell

Senior Editor

My Lady Reluctant

Laurie Grant

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

Available from Harlequin Historicals and LAURIE GRANT

Beloved Deceiver #170

The Raven and the Swan #205

Lord Liar #257

Devil’s Dare #300

My Lady Midnight #340

Lawman #367

The Duchess and the Desperado #421

Maggie and the Maverick #461

My Lady Reluctant #497

To my wonderful agent, Maryanne Colas, for her

guidance (and help with my French!) and friendship,

and always, to Michael, my very own hero

Contents

Prologue (#u31381e07-93a3-5443-9f6e-767f36f19a5d)

Chapter One (#u51a22f52-7296-5b4b-a970-35afa0fc781a)

Chapter Two (#u3ba0a77c-c5b0-5119-a536-4c714b8b2204)

Chapter Three (#udd2d829c-ae3c-56bf-87b7-fbfd40d682e9)

Chapter Four (#uafe06faf-d74a-5fe5-a036-a33e563d5b5a)

Chapter Five (#ue601cddf-570d-5ef4-948a-0b92bb7a131d)

Chapter Six (#u0bde2ab4-1eb0-5c13-bba6-01581054f98a)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Historical Afterword (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue

Normandy, 1141

“He rejected me? The Baron of Hawkswell rejected me, Sidonie Gisele de l’Aigle? Is he so rich that he has no interest in wedding an heiress?” Indignation laced Gisele’s voice and sent a rush of heat up her neck to flush her cheeks. By the Virgin, she would never survive the humiliation, the shame!

Her father, Charles, Count de l’Aigle, smirked. “Nay, he’s but a fool. Not only is Alain of Hawkswell not overwealthy, but he’s spurned you for a lady whose family are adherents of Stephen’s!”

Gisele felt her jaw drop with shock, and for a moment she forgot the affront to her own pride. For one of the Empress Matilda’s lords to refuse her choice of a bride for him, the heiress of a Norman family whose alliance with the empress was bedrock-solid, was beyond foolish, unless…

“Is he changing sides, then? Does he now side with King Stephen?” she mused.

Her father’s brow furrowed, and he rubbed his chin.

“Nay, that’s the mysterious part. The word is he’s as much Matilda’s man as before, yet he’s apparently married the woman with Matilda’s blessing.”

Gisele sighed as the pain of rejection mingled with envy in her soul. It wasn’t so mysterious, not to her. Lord Alain had married for love. He had loved this woman enough to risk the empress’s displeasure and had been rewarded by not losing her favor. Ah, to have a man love her, Gisele de l’Aigle, like that! And the name Alain had had such a kind sound to it. Gisele had thought that here was a man who might understand her, who might value her for what she was, and not merely what she could bring him by marriage. Her heart mourned the passing of that dream.

“There must be more going on there than meets the eye,” her father continued, oblivious of her grief, “but in any case my problem is not solved. Here I am, an old man with no heir for my lands but a mere girl, a girl who’s of marriageable age, and not a husband in sight.”

Being seen as of no value by her father, at least, was an old and familiar hurt. He had always treated her as if being born female were somehow a fault she could have remedied in the womb if she’d only been industrious enough. I may be but a girl, but I’m worth your love, she wanted to cry, but knew it was no use. He could not love her, would never love her as he would have if she’d been the son he’d hoped for. Now she only represented a pawn he could use to obtain a son, at least one by marriage. Well, she’d have no more of it!

“Don’t think you can palm me off on some sprig of nobility on this side of the Channel, then, my lord father! I’ll just stay here at l’Aigle and be your chatelaine,” she announced, stalking over to the open window to look down on the swirling currents of the Risle that flowed just beyond the curtain wall.

“And when I die?” her father interrupted, his face darkening.

“I’ll be the Lady of l’Aigle in my own right.”

“Foolish wench!” Her father’s voice was a lash that cut her heart. “Did you just crawl out from underneath a cabbage leaf? No mere female can hold a castle, l’Aigle or any other!”

“But the empress is her father’s heir to the throne in her own right.”

“Yes, and you have heard what a merry time she’s having trying to hold on to that throne, have you not?” the count retorted. “England is torn apart while she wrangles with her cousin, Stephen of Blois! And you’d be overrun by our nearest neighbor in a se’enight. Nay, Sidonie Gisele—” he always used both her names, both the one she went by, Gisele, as well as her first name, which had been the name of his despised dead wife, when he meant to make an unpleasant point “—a noble female has two choices in this world—the marriage bed or the convent. I cannot even allow you to chose the latter, for I have no heir and I will not give l’Aigle back to the duchy of Normandy when I die!”

His last words, shouted so loudly that they echoed off the stone walls, merely strengthened her resolve to be owned by no man. But before she could voice her resistance, her father spoke again.

“I haven’t given up my dream of having a holding in England, even if only through my daughter,” the count replied in his condescending way, “and actually, the empress has not left me without remedy,” the old man said, joining her at the window. “She bids me send you to wait upon her. As a lady-in-waiting to the empress, you are bound to catch the eye of some powerful and marriageable vassal of hers.”

“I? Go to England alone?” How could he send her to a country he had just described as torn apart by civil war? Yet, there were advantages to the idea, not the least of which was the pleasure of leaving behind a father who could not love her or even respect her. The empress was a powerful woman, even though she was having to fight to keep the crown her father, Henry, had bequeathed her. Matilda, a woman unhappy in her own marriage, would surely understand Gisele’s wish to control her own fate, and allow her to remain unwed.

Mayhap, once she was in England, she’d see this Alain, Baron of Hawkswell, and the lady he’d chosen over her.

“Nay, of course you would not be alone,” the old man snapped. “I believe I know what’s due to the heiress of l’Aigle. I would have to send a suitable escort of my knights along—a half dozen should be an impressive enough number, though I can ill spare them, you know—and old Fleurette to attend you. The knights will return as soon as they’ve delivered you to the empress, while Fleurette can remain with you.”

Thus ridding you permanently of two mouths to feed rather than one, eh, Father? The idea of her old nurse, now more of a beloved companion than a servant, coming with her was comforting enough to prevent Gisele from commenting on her father’s begrudging her even the temporary use of six of his knights.

Once she was in England, all would be different.

Chapter One

“I vow, there is nothing more to bring up but my toenails,” moaned Gisele in the sheltered aftcastle of the cog Saint Valery.

“Yes, you’re no sailor, that’s sure,” Fleurette murmured soothingly as she smoothed the damp brown locks away from Gisele’s forehead as her lady lay with her head pillowed in her old nurse’s lap. “The Channel’s been smooth as glass from the moment we left Normandy. I’d hate to see how you’d fare in rough seas.”

“Well, you never shall, for I’m never setting foot on a ship again my entire life,” muttered Gisele, then grabbed the basin at her nurse’s feet as a new round of spasms cramped her belly.

“What, never returning home?” asked the old woman in shocked tones. “Of course you shall return to Normandy, if only to allow your father to meet the fine lord you will marry, and to show him his grandchildren.”

Gisele had yet to confide in her former nurse that her plans were different from those her father had made for her, and she didn’t have the energy to do it now, so she merely played along.

“Of course I shall go to Normandy to show off my husband and the babes he shall give me,” she told Fleurette with a wan attempt at a smile. “I’m sure we shall be so blissful that it will be no effort at all to just float across the waves….”

“Ah, go on with you, then!” Fleurette said, giving her an affectionate pat. “You always did have a ripe imagination!”

“I have an imagination? ’Tis you imagining me with a husband and babe in a triumphal return to l’Aigle, long before we have so much as landed in England, let alone met any of Matilda’s marriageable lords.”

“Eh, well, I don’t know what your lord father can be thinking of, sending you off to a country in the grip of civil war—”

“England lies ahead!” called the lookout in the crow’s nest.

Within an hour of landing, they were on their way to London. Gisele, exhausted from the hours of retching aboard the tossing cog, would have liked to lie overnight in Hastings, and she knew the elderly Fleurette would have been better off with a night of rest. But Sir Hubert LeBec, the senior of the knights, was a hard-bitten old Crusader who clearly saw escorting his lord’s daughter as an onerous chore, to be accomplished as swiftly as possible. He allowed Lady Gisele and her companion just time enough to take some refreshment at an inn, but no more.

Gisele had thought just an hour ago she’d never be able to eat again, but now, revitalized by a full stomach and delighted to be back on firm ground again, did not begrudge her father’s captain his hurry. She was eager to get on with her new life, the life that would begin once she reached London, which was now held by the empress.

Lark, the chestnut palfrey she had brought from l’Aigle, had smooth paces and gentle manners, allowing Gisele to savor the beauty of the coastal area as they left the town behind. The countryside was decorated in the best June could offer. Blue squill garnished grasslands nearest the sea, giving way to white cow parsley banking the roadsides, mixed with reddish-purple foxglove. Some fields were dotted with grazing sheep; others looked like they were carpeted in gold, for the rape grown to feed pigs and sheep was now in flower. In the sky, skylarks and kestrels replaced the gulls that had ruled the air over the harbor.

So this is England, she thought with pleasure. Her father had called it a foggy, wet island, but today at least, she saw no evidence of such unpleasant weather. This is my new home. Here I will build a new life for myself, a life where I am my own mistress, at no man’s beck and call.

After she had been a-horse for some three hours, Gisele urged her palfrey up to the front of the procession, where the captain was riding with another of the men. “How far is it to London? Will we reach it tonight, Sir Hubert?” Gisele asked LeBec.

He wiped his fingers across his mouth as if to rub out his smirking grin. “Even if we had wings to fly, my lady, ’twould be too long a flight. Nay, we’ll lie at an abbey tonight—”

“An abbey? Is there not some castle where we might seek hospitality? Monastic guest houses have lumpy beds, and poor fare, and the brothers who serve the ladies look down their pious Benedictine noses at us,” Gisele protested, remembering her few journeys in Normandy.

“We’ll stay at an abbey,” Sir Hubert said firmly. “’Twas your father’s command, my lady. Much of southern England is sympathetic to Stephen, and the even those who were known to support the empress may have turned their coats since we last had word on the other side of the Channel. You’d be a great prize for them, my lady—to be held for ransom, or forcibly married to compel your father to support Stephen’s cause.”

His words were sobering. “Very well, Sir Hubert. It shall be as my lord father orders.”

He said nothing more. Soon they left the low-lying coastal area behind and entered a densely forested area.

“What is this place?” Gisele asked him, watching as the green fastness of the place enshrouded the mounted party and seemed to swallow up the sun, except for occasional dappled patches on the forest floor.

“’Tis called the Weald, and I like it not. The Saxons fleeing the Conqueror at Senlac once took refuge here, and the very air seems thick with their ghosts.”

His words formed a vivid image in her mind, and as Gisele peered about her, trying to pierce the gloom with her eyes, it seemed as if she could see the shades of the long-dead Saxons behind every tree.

“Then why not go around the Weald, instead of through it?” she inquired, trying not to sound as nervous as he had made her feel.

“’Tis too wide, my lady. We’d add a full day or more onto our journey, and would more likely encounter Stephen’s men.” Evidently deciding he’d wasted enough time in speech with a slip of a girl, he looked over his shoulder and said, “Stay alert, men. An entire garrison could hide behind these oaks.”

Gisele, following his gaze, looked back, but was made more uneasy by the faces of the other five knights of the escort. Faces that had looked bluff and harmless in the unthreatening sunlight took on a secretive, vaguely menacing, gray-green cast in the shadows of the wood. Eyes that had been respectfully downcast during the Channel crossing now stared at her, but their intent was unreadable.

For the first time Gisele realized how vulnerable she was, a woman alone with these six men but for the presence of Fleurette, and what good could that dear woman do if they decided to turn rogue? What was to stop them from uniting to seize her and hold her for ransom, figuring they could earn more from her ransom than a lifetime of loyal service to the Count de l’Aigle? Inwardly she said a prayer for protection as she dropped back to the middle of the procession to rejoin Fleurette.

Fleurette had been able to hear the conversation Gisele had had with LeBec, and it seemed she could guess what her mistress had been thinking. But she had apprehensions of her own. “’Tis not your father’s knights we have to worry about in here,” she said in low tones. “’Tis outlaws—they do say outlaws have thriven amid the unrest created by the empress and the king both striving for the same throne. ’Tis said it’s as if our Lord and His saints sleep.”

Gisele shivered, looking about her in the murky gloom. The decaying leaves from endless autumns muffled the horses’ plodding and seemed to swallow up the jingle of the horses’ harnesses, the creak of leather and the occasional remark passed between the men. Not even a birdcall marred the preternatural quiet.

Gisele could swear she felt eyes upon her—eyes other than those of the men who rode behind her—but when she stared into the undergrowth on both sides of the narrow path and beyond her as far as she could see, she saw nothing but greenery and bark. A pestilence on LeBec for mentioning ghosts!

Somewhere in the undergrowth a twig snapped, and Gisele jerked in her saddle, startling the gentle palfrey and causing her to sidle uneasily for a few paces.

Gisele’s heart seemed to be ready to jump right out of her chest.

She was not the only one alarmed. LeBec cursed and growled, “What was that?”

Suddenly a crashing sounded in the undergrowth and a roe deer burst across the path ahead of them, leaping gracefully into a thicket on their left.

“There’s what frightened ye, Captain,” one of the men called out, chuckling, and the rest joined in. “Too bad no one had a bow and arrow handy. I’d fancy roast venison for supper more than what the monks’ll likely serve.”

“Those deer are not for the likes of you or me,” countered LeBec in an irritated voice. Gisele guessed he was embarrassed at having been so skittish. “I’d wager the king lays claim to them.”

“What care have we for what Stephen lays claim to?” argued the other. “Is my lord de l’Aigle not the empress’s man?”

“You may say that right up until the moment Stephen has your neck stretched,” the captain snapped back.

For a minute or two they could hear the sounds of the buck’s progress through the distant wood, then all was quiet once more. The knights clucked to their mounts to resume their plodding.

In the next heartbeat, chaos descended from above. Shapes that Gisele only vaguely recognized as men landed on LeBec and two of the other men, bearing them to the ground as their startled horses reared and whinnied. Arrows whirred through the air. One caught the other man ahead of Gisele in the throat, ending his life in a strangling gurgle of blood as he collapsed on his horse’s withers.

“Christ preserve us!” screamed Fleurette, even as an arrow caught her full in the chest. She sagged bonelessly in the saddle and fell off to the left like a limp rag doll.

“Fleurette!” Gisele screamed frantically, then whirled in her saddle in time to see the rear pair of knights snatched off their horses by brigands who had been merely shapeless mounds amidst the fallen leaves seconds ago. Then Lark, stung by a feathered barb that had pierced her flank, forgot her mannerly ways and began to buck and plunge. Gisele struggled desperately to keep her seat while the shouts and screams of the men behind her and ahead of her testified to the fact that they were being slaughtered by the forest outlaws. The coppery smell of blood filled the air.

With no one left to protect Gisele, the outlaws were advancing on her now, their dirty, bearded, sweat-drenched faces alive with anticipation, holding crude knives at the ready, some with blades still crimson with the blood of the Norman knights dead and dying around them. She was about to be taken, Gisele realized with terror, and what these brigands would do to her would make LeBec’s mention of being held for ransom or forcibly wed sound like heaven in comparison. They’d rape her, like as not, then slit her throat and sell her clothes, leaving her body to be torn by wild animals and her bones to be buried eventually by the falling leaves.

But her palfrey was unwittingly her ally now. As Gisele clung to Lark’s neck, her mount plunged and kicked so wildly that none of the brigands could get near her. One of them picked up his bow and nocked an arrow in the bowstring, leveling it at the crazed beast’s chest.

Then another—perhaps he was the leader—called out something in a guttural English dialect unknown to Gisele. The gesture seemed to indicate that they were not to harm the palfrey—no doubt that man, at least, realized the mare was also a valuable prize. The brigands fell back, but their eyes gleamed like those of wolves as they circled around Gisele and her mare, looking for the opportunity to snatch the wild-eyed horse’s bridle.

In a moment they would succeed, Gisele thought, still striving to keep her seat, and then they would rend her like the two-legged wolves they were. Our Lady help me! Then, on an impulse, she shrieked as if all the demons in hell had just erupted from her slender throat.

It was enough. Terrified anew, the mare sprang sideways, knocking a nearby outlaw over onto his back, then bolted between two other outlaws and headed off the path into the depths of the wood at a crazed gallop. Gisele bent as low as she could over the mare’s straining neck as branches whipped by her face, tearing at her clothes, snatching off her veil and scratching her cheeks.

The sounds of the brigands’ foot pursuit grew more and more distant behind her. If she could just circle her way back out of this wood, Gisele thought, she would ride back to the nearest village. She’d find someone in authority to help her go back and find the rest of her party, though she was fairly certain none were alive. Fleurette had probably died instantly, Gisele thought with a pang of grief, but there was no time to mourn now. A parish priest would surely help her find assistance to get to London and the empress—and she’d send the sheriff back to clean out this nest of robbers!

But Gisele had no idea which way the mare was headed. She had lost her reins as well as her sense of direction in the attack. For all she knew, the terrified beast was going in a circle that would lead her right back into the brutal arms of the outlaws!

She ducked just in time to avoid a painful collision with a stout oak branch, and after that she did not dare to raise her head again. The ground blurred by beneath her. Saints, if she had only been riding astride, it would be easier to hug the horse’s neck, but ladies did not ride astride.

Ladies did not usually have to flee for their lives, either, Gisele reminded herself. When a quick glance revealed no low-lying branches immediately ahead, she renewed her clutching hold on the beast’s streaming mane and threw her right leg over the mare’s bunching withers. There was no stirrup to balance her on that side, of course, but she gripped with her knees as if her salvation depended upon it. Without reins, she would just have to wait until the palfrey wore itself out, and hope that the Weald was not as deep as it was wide. Surely she’d come out before she was benighted here, and find some sort of settlement on the other side.

A log loomed ahead of them, and Gisele tried in vain to persuade the mare away from it by pressure from her knees and tugging on her mane, but having come so far on her own impulses, the palfrey was seemingly loath to start taking direction now. The horse gathered herself and leaped the log, with Gisele clinging like a burr atop her, but then caught her hoof in a half-buried root at her landing point on the other side.

Whinnying in fear, the mare cartwheeled, her long legs flailing. Gisele had no chance to do more than scream as she went flying through the air, striking the bole of a beech with the side of her head. There was a flash of light, and then—nothing.

Chapter Two

Gisele awoke to a gentle nudge against her shoulder. Lark? But no, she thought, keeping her eyes closed, whatever pushed against her shoulder was harder than the soft velvety nose of her palfrey. More like a booted foot…

The outlaws had found her, and were poking her to see if she lived. She froze, holding her breath. In a moment they would try some more noxious means of eliciting a response, and she would not be able to hold back her scream. Doubtless that would delight them.

She waited until her lungs burned for lack of air, then took a breath, eyes still closed.

“The lady lives, my lord.”

“So ’twould seem.”

They spoke good Norman French, not the gutteral Saxon tongue of the outlaws. Gisele’s eyes flew open.

And looked directly up into eyes so dark and deep that they appeared to be black, bottomless pools. The man who owned such eyes stood over her, gazing down at her with open curiosity. He had a warrior’s powerful shoulders and broad chest, and from Gisele’s recumbent position he seemed tall as a tree. He wore a hauberk, and the mail coif framed a face that was all angular planes. The lean, chiseled face, firm mouth, and deep-set eyes shouldn’t have been a pleasing combination, but despite the lack of a smile, it was.

Next to him, the other man who had spoken leaned over to stare at her, too. Even taller than the man he had addressed as my lord, he was massively built, and wore a leather byrnie sewn with metal links rather than a hauberk. Possibly a half-dozen years younger than his master, he was not handsome, but his face bore a stamp of permanent amiability.

“Who—who are you?” Gisele asked at last, when it seemed their duel of gazes might go on until the end of the world.

“I might ask the same of you,” the mail-clad man pointed out.

Gisele wondered if she should tell him the truth. By his speech, the quality of his armor, and the presence of the gold spurs, she could tell he was noble, but whose vassal was he? If he was Stephen’s and found out she was the daughter of a vassal of Matilda’s, would he still behave chivalrously toward her, or treat her with dishonor? She dared not tell him a lie, for in the leather pouch that swung from her girdle, she bore a letter her father had written to introduce her to the empress. If the man standing over her was the dishonorable sort, he might have already have searched that pouch for valuables, and discovered her identity and her allegiance. But he did not look unscrupulous, despite the slight impatience that thinned his lips now.

“I am Lady Sidonie Gisele de l’Aigle. And you?”

He went on studying her silently, until the other man finally said, “He’s the Baron de Balleroy, my lady. What are you doing in the woods all alone?”

“Hush, Maislin. Forgive my squire his impertinence, Lady Gisele. My Christian name is Brys, since you have given me yours. Might I help you to your feet?” he asked, extending a mail-gauntleted hand.

Up to this point Gisele hadn’t moved from her supine position, but as she pushed up on her elbows preparatory to taking his hand, it suddenly seemed as if the devil had made a Saracen drum out of her head and was pounding it with fiendish glee. With a moan she sank back, feeling sick with the intensity of the pain.

“She’s ill, my lord!” the squire announced anxiously.

“I can see that,” she heard de Balleroy snap. “Go catch her palfrey grazing over there, Maislin, while I see what’s to be done. I can see that your face is scraped, my lady, but where else are you hurt? Is aught broken?”

She opened her eyes again to find de Balleroy crouching beside her, his face creased with concern. He was reaching a hand out as if to explore her limbs for a fracture.

“Nay, ’tis my head,” she told him quickly, before he could touch her. “It feels as if it may split open. I…my palfrey fell, and I with her. I…guess the fall knocked me insensible. How long have I lain—” she began, as she struggled to sit up again.

“Just rest there a moment, Lady Sidonie,” he began.

“Gisele,” she corrected him.

He looked blank for a moment, until she explained, “I go by my middle name, Gisele. I was named Sidonie for my mother, but to avoid confusion, I am called Gisele.” There hadn’t been, of course, any confusion in the ten years that her mother had been dead, but de Balleroy needn’t know that.

She started to lever herself into a sitting position, but he put a hand on her shoulder to forestall her. “As to how long you lay there, I know not—but ’tis late afternoon now. And as my squire asked, what were you doing in the Weald alone?” There was an edge to his voice, as if he already suspected her answer.

And then she remembered. “Fleurette! I must go to her! And the men! Maybe I was wrong—even now, one or two may still live!” She thrashed now beneath his hand, struggling to get up, her teeth gritted against the pain her movement elicited.

“Lie still, my lady! You gain nothing if the pain makes you pass out again! You traveled with that party of men-at-arms, and the old woman? My squire and I…well, we came upon them farther back, Lady Gisele. There is nothing you can do for them. They are all dead.”

He could have added, And stripped naked as the day they were born, their throats cut, but he did not. Lady Sidonie Gisele de l’Aigle’s creamy ivory skin had a decidedly green cast to it already. If he described the scene of carnage he and his squire had found, she just might perish from the shock.

She ceased trying to rise. Her eyelids squeezed shut, forcing a tear down her cheek, then another. “We were set upon by brigands, my lord,” she said, obviously struggling not to give way to full-blown sobbing. “They jumped out of the trees without warning. I saw the arrow pierce my old nurse’s breast…but I hoped…”

“Like as not she was dead before she hit the ground, my lady.” Brys de Balleroy said, keeping his voice deep and soothing. “I’ll come back and see them buried, I promise you. But now we must get you to safety—’twill be dusk soon, and we must not remain in the woods any longer. Do you think you can stand?”

She nodded.

“Let me help you,” he told her, placing both of his hands under her arms to help her up. Over his shoulder, Brys saw that his squire had caught the chestnut mare and stood holding the reins nearby, his face anxious.

Lady Gisele gave a gallant effort, but as she first put her weight on her left foot, she gasped and swayed against him. “My ankle—I cannot stand on it!” Pearls of sweat popped out on her forehead as he eased her to the ground. Her face went shroud-white, her pupils dilated.

Leaving her in a sitting position, he went to her foot and began to pull the kidskin boot off.

She moaned and grabbed for his hand. “Nay, it hurts too much….”

He took the dagger from his belt and slit the kidskin boot open from top to toe, peeling the ruined boot from around her swollen ankle before probing the bone with experienced fingers.

He looked up to see her gritting her teeth and staring at him with pain-widened eyes. “’Tis but sprained, I think, my lady, though I doubt not it pains you, for ’tis very swollen. You cannot ride your mare, that’s clear, so you will have to ride with me.”

“But surely if you’ll just help me to mount, I can manage,” she insisted, trying once again to rise.

“You’ll ride with me,” he said, his face set. “You still look as if you could swoon any moment now, and I have no desire to be benighted in this forest with no one but me and my squire to fend off those miscreants. They may come looking for you, you know, so I’ll hear no more argument. Maislin, tie her palfrey to a tree and bring Jerusalem over. I’ll mount and you can lift her up behind me, then lead her mare. You can manage to ride pillion, can’t you, Lady Gisele? I’d hold you in front of me, but I’d rather have my arms free in case your attackers try again before we get out of the wood.”

She nodded, her eyes enormous in her pale oval face. Brys could not tell what hue they were, not in this murky gloom, but he could see she was beautiful, despite the rent and muddied clothes she wore. She had a pert nose, high cheekbones and lips that looked made for a man’s kiss. Beneath the gold fillet and the stained veil which was slightly askew, a wealth of rich brown hair cascaded down her back, much of it loose from the thick plait which extended nearly to her waist.

Once Brys was mounted on his tall black destrier, Maislin lifted Lady Gisele up to him from the stallion’s near side, his powerfully muscled arms making the task look effortless.

“Put your arms about my waist, my lady,” Brys instructed her. “Jerusalem’s gait is smooth, but ’twill steady you as we ride.”

A faint essence wafted to his nostrils, making him smile in wonder. After all she had been through, Lady Gisele de l’Aigle still smelled of lilies. He felt her arms go around him and saw her hands link just above his waist; then felt the slight pressure of her head, and farther down, the softness of her breast against his back. God’s blood, what a delicious torment of a ride this would be!

“You have not said how you came to be here, Lady Gisele,” he said, once they had found the path that led out of the Weald.

He felt her tense, then sigh against his back. He could swear the warmth of her breath penetrated his mail, the quilted aketon beneath, and all the way to his backbone.

“I suppose I owe you that much,” she said at last. “But I must confess myself afraid to be candid, my lord. These are dangerous times….”

Stung by her remark, he said, “Lady, I do not hold my chivalry so cheaply that I would abandon you if I liked not your reason for being in this wood with such a paltry escort. And even if I wanted to, Maislin wouldn’t allow it. He aspires to knighthood and his chivalry, at least, is unsullied.”

He heard her swift intake of breath. “I’m sorry,” she said at last. “I have offended you, and ’twas not my intent, when you have offered me only kindness. But even in Normandy we are aware of the trouble in England, as one noble fights for Stephen, the other for the empress. I know not which side you cleave to, my lord, though I know I am at your mercy whichever it is.”

The idea of this demoiselle being at his mercy appealed to him more than he cared to admit. Aloud, he said, “Then I will tell you I am a vassal of the empress. Does that aid you to trust me? I swear upon the True Cross you have naught to fear of me, even if you are one of Stephen’s mistresses.”

He felt her relax against him like a full grain sack that suddenly is opened at the bottom. “No, I am assuredly not one of those. The de l’Aigles owe their loyalty to Matilda as well, Lord Brys. In fact, I am sent to join her as a lady-in-waiting.”

“Then we are on the same side. ’Tis well, is it not? And better yet, I am bound for London with a message for the empress, so I will consider it my honor to escort you to her court.”

“Our Lord and all His saints bless you, Lord Brys,” she murmured. “I will write to my father, and ask him to reward your kindness.”

“’Tis not necessary, lady. Any Christian ought to do the same,” he said. He felt himself begin to smile. “I am often with her grace, so we shall see each other on occasion. If I can but claim a smile from you each time I come, I shall ask no other recompense.” He could tell, from the shy way she had looked at him earlier, that she was a virgin. Alas. Lady Gisele, if only you were a noble widow instead of an innocent maiden, I’d ask an altogether different reward when I came to court. Brys felt his loins stir at the thought.

Behind him, he heard Maislin give a barely smothered snort, and knew his squire was struggling to contain his amusement at the fulsome remark. He would chasten him about it later, Brys was sure.

“And when did you come to England, Lady Gisele?” he asked, thankful she was riding behind him and could not see the effect his thoughts had on his body.

“We landed at Hastings but this morning, my lord.”

Brys considered that. “Lady Gisele, forgive me for asking, but if your father is as aware of the conditions here as you say, why would he send you with but half a dozen men and an old woman?”

She was silent, and Brys knew his words had been rude. What daughter could allow a parent to be criticized? “I’m sorry if I sounded harsh—”

“Nay, do not apologize, for you are right. There should have been a larger escort. I know that had my horse not bolted, I would have been lucky to escape those brigands with my life, let alone my honor.” Her voice was muffled, as if she fought tears. “Poor Fleurette—to have died because of my father’s…misalculation. And those six men, too. They did not deserve to perish like that, all unshriven.”

He was ready to swear she’d meant some other word when she’d said miscalculation, and he wondered what it was—and what was wrong with the Count de l’Aigle that he valued his daughter so cheaply.

“You have a tender heart, lady.” He only hoped it would not lead her astray at Matilda’s court.

“Fleurette had been my nurse from my earliest childhood, so ’tis natural I would grieve at her death,” she said, sounding a trifle defensive. “The men…well, I have difficulty accepting that because my lord father ordered them to escort me to London, they lie dead now.”

This was an uncommon noblewoman, to spare a thought for common soldiers. “Dying violently is the risk any man-at-arms runs, but doubtless their loyalty will outweigh their sins, Lady Gisele.”

“God send you are right.”

Perhaps it was best not to allow her to dwell on such things right now. After a moment he said, “You go to court to wed, my lady?”

He felt her stiffen against his back. He glanced back over his shoulder and saw that her eyes had the light of defiance dancing in them.

“’Twas my father’s wish, my lord.”

He was quick to catch the implication. “But not yours?” he asked, glancing over his shoulder again.

He saw her shrug. “I shall have a place at the empress’s court,” she said. “That will be enough for me. What need have I for some lord to carry me off to his castle to bear a child every year till I am no longer able?”

An image flashed before his mind’s eye of this woman nursing a babe—his babe. Sternly he banished the picture before he grew too fond of it. There was no place in his life for such feelings, and the lady had just indicated there was none in the life she wanted, either. But he could not stop himself from probing further, though in a carefully neutral tone of voice, “You do not wish to fulfill the role that nature and the church has deemed fit for a woman?”

“There must be more for a woman than the marriage bed or the convent, no matter what the church tells us,” she said with a passionate insistence. “There must be.”

“Lady, has a man hurt you in some manner?” he asked in a low tone that would not carry to Maislin’s ears. Had he been wrong about her? Had some man robbed her of her innocence?

Her answer came a little too quickly. “Hurt me? Nay, my lord! Just because the lord the empress selected for me chose to marry some other lady, you should not think that I am not heart-whole.”

She was lying, he’d wager his salvation on that. There was a wealth of wounded pride in her voice. But something about her last few words sounded familiar….

“Nay, my lord,” she went on in a breezy voice, “’Tis merely that I see no need to w—”

Suddenly he realized who she was. “Ah, you’re the one Matilda offered to Baron Alain of Hawkswell, aren’t you?”

“And how did you know such a thing?” she asked, her voice chilly.

He felt her remove her arms from about his waist and draw a little away from him. Instantly his body felt deprived. He wanted to demand that she put her arms back around him—he didn’t want her to fall, of course!

“Fear not, proud lady—’tis not a thing bandied about court—the only reason I know is that Alain is a good friend.”

“How nice for you to have such a friend,” she said, as if every courteous word cut her like a dagger.

“Nay, do not bristle at me,” he said, patting her hands that were still clasped around his abdomen with his free one. “Alain would not have suited you at all—a widower with two children? Claire is much more his sort, for all that her family are adherents of Stephen’s. You’ll see what I mean if you ever meet them.”

“Mayhap,” she said noncommittally, but he could tell she was lying again. She’d move heaven and earth to avoid encountering the man who had rejected her, sight unseen. What a proud, fierce maid she was!

“I think you have the right idea, Lady Gisele—enjoy your life at court just as any bachelor knight enjoys his freedom,” he told her. “You’ll enjoy the empress’s favor and all her lords will covet you.”

“I told you,” she began, impatience tingeing her voice, “I care not about the opinion of men—”

“Of course, of course,” he said. “Hold to that course, my lady, for we are knaves one and all.” But Brys could guess how Lady Gisele’s coolness would affect the men in the empress’s orbit—they’d be panting all the more after Gisele de l’Aigle, like brachets after a swift doe. He felt acid burn in his stomach at the thought. And Brys could only wonder how long Matilda would allow such a beauty to indulge her whims before she used her as a pawn in making an alliance.

Chapter Three

At last they came to a Benedictine priory just beyond the edge of the Weald. Gisele, exhausted by the day’s events and longing to have some time to grieve in private, told Brys before he even assisted her to dismount that she was too tired to dine in the guest house and would seek her bed early instead.

“Very well, then, my lady,” he said. “Doubtless you’ll feel better on the morrow. I will send the infirmarer to you with a salve for your cuts and a draft to help you sleep. Your ankle will have swollen since this afternoon, and the pain is apt to keep you wakeful.”

“You seem very familiar with what this house has to offer, my lord,” she said. Now that they were beyond the forest gloom, she saw that his eyes were not black, but a deep, rich brown, like the color of her palfrey’s coat.

“I have sought remedy for injury here before,” he said, without elaborating.

She could tell that Brother Porter was scandalized by the way de Balleroy handed her down to his squire, then took Gisele back into his arms and bid the monk to lead the way to the ladies’ guest quarters. But the disapproving Benedictine did not remonstrate with him, just directed another pair of monks to stable the horses, before gesturing for de Balleroy to follow him.

Gisele awoke and hobbled her way to the shuttered window, throwing it open to see if it was yet light. She was alarmed to see that the sun was already high in the sky. The infirmarian’s potion had been powerful indeed! She hadn’t even heard the chapel bells call the brothers to prayer during the night. Her ankle still throbbed, though less than it had last even.

Then a sudden thought struck her. Dear God, what if Brys de Balleroy had grown tired of waiting and had ridden on to London without her? What of his promise to have Fleurette and the men-at-arms buried?

Hopping awkwardly over to the row of hooks by the door where she had left her muddied, torn gown hanging, she found the garment miraculously clean and dry again. Propped up against the wall beneath the gown was a crutch with a cloth-padded armrest. She silently blessed whichever Benedictines had done her these kindnesses, and with the crutch to help her, ventured out into the cloister and across the garth until she came to the gate.

“Where is my lord de Balleroy? Has he left?” she asked Brother Porter.

“Aye,” replied the monk. “He and the big fellow, his squire, left at Prime—along with a wagon and a pair of our brothers. He said he promised you he would bury your dead. Some other brothers are already digging the graves in our cemetery.”

“Oh.” So de Balleroy was as good as his word, Gisele thought, warmed by the idea that he had been up and about and fulfilling his promise while she had still been deep in slumber.

The party returned at midday. Gisele, waiting just inside the gate, saw a grim-faced de Balleroy riding behind the mule-drawn cart with its ghastly load.

“Make ready to leave, Lady Gisele,” he said as he dismounted.

“But may we not remain until they are buried? Fleurette—” she began, her voice breaking as she saw the monks begin to unload the sheet-wrapped, stiffened forms. She could not even tell which one was her beloved nurse.

“Is at peace already, my lady, and if we stay for the burial we will have to spend another night here. We will have to pass one more night on the road as ’tis, and I think it best to get you to the empress as soon as I can. Do not fear, the Benedictines will see all done properly.”

She could see the prudence of that, of course, but nevertheless, her heart ached as she rode away from the priory within the hour, once more riding pillion behind de Balleroy.

The next day, as the distant spires of London came into view ahead of them, de Balleroy turned west.

“We do not go directly to London?” Gisele questioned.

“Nay. The empress resides at Westminster, a few miles up the Thames, my lady,” de Balleroy told her. “But you’ll see the city soon and often enough. Now that Matilda has finally been admitted to London, and will soon be crowned, she likes to remind the citizens of her presence.”

Gisele nodded her understanding and reined her palfrey to the left, where the road led over marshy, sparsely settled ground. Though her ankle was still slightly swollen and painful, she had insisted she would sit her own horse this morning, not wanting to arrive at the empress’s residence riding pillion behind the baron as if she had no more dignity than a dairymaid. It was bad enough that outlaws possessed every stitch of clothing she owned, except for what she had on her back. Seeing her in the enforced intimacy of this position, however, someone might take them for lovers. Having her good name ruined would not be a good way for Gisele to begin her new life!

Perhaps de Balleroy had guessed her thoughts this morning. Instead of arguing about her ankle’s fitness, he had lifted her up into her saddle as if she weighed no more than an acorn, sparing her the necessity of putting her weight on the still-tender ankle to mount.

Gisele took the opportunity to study de Balleroy covertly, an easier task now that she was no longer sitting behind him. The sun gleamed on his chin-length, auburn hair. Somehow she had not expected it to be such a hue; his dark eyes and eyelashes had given no hint of it, and she had never previously seen him without his head being covered. This morning, however, he had evidently felt close enough to civilization to leave the metal coif draped around his neck and shoulders.

“Faith, but ’tis hot this morn,” he murmured, raking a hand through his hair, an action which caused the sun to gild it with golden highlights that belied the dangerous look of his lean, beard-shadowed cheeks. “I believe the sun is shining just to welcome you to court, Lady Gisele.” He flashed a grin at her, making her heart to do a strange little dance within her breast.

Firmly she quashed the flirtatious reply that had sprung ready-born to her lips. She owed this man much for her safety, but it would not do to let him think his flattery delighted her, after telling him before that such things were unimportant to her. From the ease at which such smooth words flowed from his lips, she supposed he had pleased many women with his cajolery—but she was not going to join their number!

“I believe too much sun has addled your brain, my lord,” she said tartly.

“Just so, Lady Gisele,” Maislin agreed from behind them. “From the color of his hair, ’tis obvious his skull must have been singed at one time or another, and his brain beneath it, too!”

Apparently, however, de Balleroy took her retort for bantering. “Ah, Lady Gisele, you wound me to the heart with your dagger-sharp tongue. I’ll be but a shadow of my former robust self by the time I bid you farewell at Westminster.” His merry smile didn’t look the least bit discomfitted, however.

“Oh? You’re not remaining?” she said, then wished she could kick herself, for his smile had broadened into a grin. But she was dismayed at the thought she would have to navigate the strange new world of Matilda’s palace without the presence of even one familiar face.

“Ah, so you will miss me,” he teased. “I’ll be back at court from time to time, never fear.”

“Oh, it’s naught to me, my lord,” she assured him with what she hoped sounded like conviction. She made her voice casual, even a trifle bored. “No doubt the empress will keep me so busy I should scarce know whether you are there or not. Do you return to a fief in England? Or mayhap you have a demesne and wife in Normandy?”

“Mayhap,” he said, shrugging his shoulders.

His evasiveness, coupled with her nervousness about the new life she was about to take up, sparked her temper.

“You’re very secretive, my lord. I was merely making conversation.”

“If you wanted to know if I was married, Lady Gisele, you should have asked me,” he said with maddening sangfroid.

Devil take the man! “As I said, ’tis naught to me,” she replied through clenched teeth. “I was just trying to pass the time. And after all, you know much about me and I know virtually nothing about you.”

She could read nothing in those honey-brown eyes, neither anger at her sharp tone nor amusement at her expense.

Finally he said, “I’m sorry, Lady Gisele. The responsibilities I bear for the empress have required that I keep my own counsel, and ’tis a habit hard to break.”

She averted her face from him. “Well, do not feel you must change your habit for me.”

“I am not wed,” he continued, as if she had not spoken. “I am the lord of Balleroy in Normandy, and in addition, hold Tichenden Castle here in England. I have a sister two years my junior, who acts as my chatelaine at Tichenden, two younger sisters being educated in a Norman convent—perhaps one of them will take the veil—and the youngest is a brother still at home. Our parents are dead. Is there aught else you would know?”

She refused to express surprise at the sudden flood of information. “Where is Tichenden? In the west, I assume, where the empress’s forces are strong?”

“Nay, ’tis on the North Downs.”

“But I thought Stephen’s adherents held that part of England?”

“And so they do, for the most part.” She saw that shuttered look come over his eyes again, and knew she must not delve further in this particular subject.

After ferrying themselves and their mounts across the Thames, they arrived at Westminster just at the hour of Sext. De Balleroy had just assisted Gisele to dismount and their horses were being led away by a servitor when Gisele’s stomach growled so loudly that even the baron heard it.

“Ah, too bad,” he mocked, “for I fear we’ve missed the midday meal, and ’twill be long till supper. Shall I take you first to the kitchens for something to fill your empty stomach?”

“That won’t be necessary,” she told him, wishing he’d allow her to keep her dignity, at least until she’d been presented to Matilda! “If you would direct me in finding the empress, or someone who knows where she may be found—”

Visibly making an effort to smoothe the teasing grin from his face, he murmured, “Very well, follow me, my lady. Maislin,” he called over his shoulder as he led her across the courtyard, “see that Lady Gisele’s palfrey is given a good stall, and all our mounts grained and watered, but tell the stable boy yours and mine are to be kept in readiness. We’ll likely depart by midafternoon. Oh, and don’t force me have to come and find you off in some shadowy corner with a scullery wench, Maislin.”

“Yes, my lord!” the squire called back, but his voice sounded undismayed by these strictures.

I wonder if you practice what you preach, my lord, Gisele wanted to say, but she was too intent on keeping up with him despite her painful limp.

At last he seemed to realize how far behind she was falling, and turned around. “Your dignity will have to wait until your foot is better, Lady Gisele,” he said, picking her up.

She only hoped no one important would see them.

He carried her into the palace, and through a maze of corridors, doors and antechambers. He strode along as surely as if he carried nothing, and this mysterious warren was his own castle. At last they came to a door guarded by two hefty men-at-arms, who crossed their spears to bar their way.

“Who would enter the empress’s presence?” one growled.

“Tell her chamberlain ’tis de Balleroy,” the baron responded easily, a slight smile playing over his lips as he set Gisele down.

One of the guards disappeared within, and a moment later, the door was opened, and a harried-looking man in a robe trimmed with squirrel stuck his head out and gestured that they were to enter.

Before the two could do so, however, a throaty female voice called, “Brys, is that you? Come in, you rascally knave!”

De Balleroy grinned at her as if to say, See, I told you we were knaves all!

They entered a spacious chamber into which the noonday sun streamed through several wide, arched windows, illuminating a feminine figure who glided toward them. As Matilda drew closer, Gisele saw that she was still strikingly attractive, with a slender waist that belied the fact that she had given her husband three sons. Worry had etched a sharpness to her features, though, and her gray eyes had a shrewd, penetrating quality to them. She wore a veil and wimple over her hair, with an ornate circlet of gold keeping the veil in place.

De Balleroy went down on one knee before the empress, bowing his head, while behind him Gisele awkwardly knelt also, uncertain what was proper for her to do.

“Brys,” Matilda purred in that caressing, faintly German-accented voice as she held out an ivory-white hand and extended it to de Balleroy to kiss, “Isn’t it wonderful that I am finally in Westminster Palace where I belong? I tell you, Geoffrey de Mandeville is a miracle worker, persuading those stiff-necked Londoners to let me in! Did you have a good journey? And who is this lovely maid behind you?”

Seemingly used to the empress’s flood of words, de Balleroy rose and said, “You glow like a jewel in its proper setting at last, Domina. My journey was uneventful until I traveled through the Weald, and found this lady lying unconscious, the only survivor of a massacre. May I present Lady Sidonie Gisele de l’Aigle? She goes by her middle name, Gisele.”

The empress’s eyes widened, and she glided past de Balleroy and placed her hands on Gisele’s blushing cheeks. Her hands were cool and smooth. “God in Heaven! A massacre? I have been expecting you, child—but what on earth happened? Your face—it is all scratched!” she said, tracing the scrapes on Gisele’s face, left by the tree branches during her wild ride.

“Outlaws, your…highness,” Gisele said hesitatingly. “My escort was attacked in the Weald—” She felt emotion tighten her throat.

“They were slaughtered to a man,” de Balleroy finished for her. “The miscreants even killed an old woman with them, the lady’s servant. If Lady Gisele’s horse hadn’t bolted, doubtless she would not be standing before you now, Domina. As it is, the robbers got everything she brought with her but the clothes she wears.”

“God be thanked you were preserved, child,” Matilda said, extending a hand to Gisele to assist her to her feet. Gisele arose, awkwardly because of the still-painful ankle, and she could feel Matilda assessing her, judging her appearance and her worth. If only she had had something more to wear than the travel-stained bliaut.

“I went back and buried the bodies, Empress,” de Balleroy said. “Would that I could return with a force of knights and clear out the rats’ nest of outlaws in the Weald as well.”

“Always, he is the soul of chivalry,” she said to Gisele. “Ah, Brys, if only I was already crowned, and Stephen of Blois banished across the Channel where he belongs! Then I would grant you that force! Since my cousin has been on the throne, felons and thieves have multiplied, and honest folk are murdered. It was not so in my father’s day, and will not be so in this land as soon as I have won—but who knows how long that may be?” She sighed heavily. “A deputation of the wealthiest merchants of London just left before you came, Brys, and they did not like it when I told them Stephen had left the treasury bare as a well-gnawed bone. And they took it very ill that I told them they would have to supply the funds for my crowning! Can you imagine it? They thought I should be crowned in the same threadbare garments that I brought from Anjou.”

Gisele did not think the purple velvet overgown, banded at the neck and sleeves with golden-threaded embroidery, looked at all threadbare, but possibly it was not ornate enough for the widow of the Holy Roman Emperor to wear to her crowning.

Gisele wondered, though, if it was wise for Matilda, who had been refused entrance into London for so long, to have immediately demanded money of the independent-minded Londoners. Even in Normandy it was known that the Londoners had long favored Stephen, Matilda’s rival. Surely it would have been prudent to wait a while before making financial demands?

Fortunately the empress did not seem to be expecting an answer to her question from de Balleroy, for she immediately turned back to Gisele.

“Ah, but you must be too fatigued to listen to such things, my dear, after what you have been through!” exclaimed the empress, putting her arm around Gisele’s shoulders. “I must immediately write a letter to your lord father, telling him what has befallen you and assuring him that you, at least, are unharmed!”

He won’t care, Gisele wanted to blurt out. He will begrudge me the loss of his six knights much more than he values my safety, at least until I make an advantageous marriage and provide him with a male heir. But she did not say what she was thinking; she could not bear for this worldly, sophisticated woman who had been through so much herself to pity her.

“Thank you, Domina,” Gisele managed to say, calling the empress by the title she had heard Brys use.

“Things will appear better to you after you have rested and refreshed yourself, Gisele, my dear,” Matilda said. Her husky, accented voice had a very soothing quality, and all at once Gisele could see why so many men had been willing to follow and fight for this woman, even though her fortunes had often been precarious.

“Talford!” Matilda called to the chamberlain who had been hovering in the background. “Find Lady Gisele a suitable chamber in the palace! See that she has everything she needs between now and the supper hour, and that someone comes to show her the way to the hall. Lady Gisele, I will see you again at supper, where you will meet my other ladies and members of my court.”

It was a dismissal; Matilda was already drawing de Balleroy over to two carved, high-backed chairs over by one of the windows, and the harried-looking chamberlain was gesturing for her to follow him out the door. But Gisele had wanted to bid farewell to Brys de Balleroy and thank him for his and his squire’s kindness to her. She hesitated, willing de Balleroy to turn around. “I would thank my lord de Balleroy….” she said at last, when it seemed she would be ushered away with no chance to say anything further to him.

Brys de Balleroy turned, a curious light dancing in those honey-brown eyes, and smiled encouragingly at her.

“’Twas my honor to render you such a paltry service, my lady. No doubt when I next see you, you will have blossomed like a rose, a rose every man will want for his garden.”

Easy words, glibly spoken while Matilda smiled tolerantly, then pulled Brys toward the chairs.

She wanted to ask when that would be—when would he be returning to Westminster? But she felt he had already forgotten her, and so there was nothing to do but limp after the chamberlain as he led her from the room.

Chapter Four

“I do believe the Norman damsel has stolen your heart, my lord,” Maislin commented as they rode away from Westminster, following the river back toward London. White-headed daisies and purple loosestrife waved on the riverbanks; overhead, gulls flew eastward back toward the mouth of the Thames, following a barge.

“Oh? And how many buckets of ale did you manage to swill in the short time I was gone from you?”

Maislin blinked. “I? I’m sober as a monk at the end of Lent, my lord! In fact, I was just about to ask that we stop and wet our throats at that little alehouse in Southwark. Why would you ask such a thing?”

“Why? Because I’ve rarely known you to say such a foolish thing, Maislin.”

To give him credit, the shaggy giant didn’t try to pretend he didn’t know what Brys meant. “My lord Brys,” he retorted, “you looked back at the palace walls thrice since we left. Will you try to tell me it’s the empress you’re longing for, so soon after departing her presence?”

Brys chuckled. “Nay, I’m not so foolish as to get involved in Matilda’s coils.”

His squire nodded sagely. “Aye, then ’tis the Norman maiden you’re already missing. She’s stolen your heart,” he insisted.

“I have no heart to steal, don’t you remember?” Brys reminded Maislin, with a wry twist of his mouth. “At least, that’s what you always say when I won’t stop at every alestake between here and Scotland. Nay, I’m just pitying poor Lady Gisele. I feel like an untrustworthy shepherd who has just tossed a prize lamb in among a pack of wolves.”

Maislin grinned. “Could a man who never had a heart speak so, Lord Brys? Aye, you’ve got feelings for the Norman lass, I’ll be bound! And why not? She is a toothsome damsel, with those great round eyes and soft rosebud lips and that thick chestnut hair. Tell me your loins never burned while you were carrying her into the priory, or while she was ridin’ behind you with her softness rub—”

Brys put up a gauntleted hand to forestall his squire’s frankness. “Careful…” Damn Maislin, he could feel his aforementioned loins tingling as Maislin reminded him of the exquisite torment he’d experienced the past two days due to his enforced contact with the Norman maiden. “You’re confusing a heart with a conscience, Maislin,” he said. “I merely don’t like to think of an innocent such as Lady Gisele at the mercy of every lecherous knight at Matilda’s court.”

“Innocent?” Maislin mused consideringly. “Aye, I think you’ve the right of it there, my lord. The wench is innocent as a newborn kitten.”

“She can spit like a kitten, too,” Brys murmured, recalling the indignant way she had spoken of her rejection by his friend Alain of Hawkswell. “I merely fear she has not claws enough for the savage dogs that lurk about the empress,” he added, as some of the faces of Matilda’s supporters came to mind.

“There is a remedy, if you are truly worried, my lord,” Maislin said, mischief lurking in his blue eyes.

“Oh? And what would that be, pray?” Brys asked, suspicious.

“’Tis obvious! Take her to wife yourself, my lord! I’d vow you could have that kitten purring in your arms well before dawn!”

Suddenly the conversation had gone on too long. “Cease your silly japing, Maislin,” Brys commanded, turning his face from his squire. “You’re making my brains ache.”

“But ’tis no jape, my lord Brys,” Maislin protested. “Why not wed Lady Gisele? She’s comely enough for a prince, and is an heiress in the bargain! Why not make Hawkswell’s loss your gain? You must marry some lady and give a son to Balleroy!”

“Maislin, you forget yourself,” Brys snapped. “I’ll brook no more talk like this! You would do well to remember that we have been entrusted with a mission, and keep your mind upon it. Not upon your lord’s private business.”

“Yes, my lord,” his squire said, his usually merry face instantly crestfallen, his cheeks a dull brick red.

They rode in silence for the next few minutes. His squire’s words echoed back to him—You must marry some lady and give a son to Balleroy—as if Balleroy were not his castle in Normandy, but a greedy pagan god to be appeased by the offering of a male infant. He had sisters, and no inclination to tie himself down to a wife just now. If he was caught while he played his dangerous game, and paid with his life, one of his sisters could marry and provide Balleroy with its heir.

Then why could he not banish Gisele de l’Aigle’s face from his mind? Her creamy oval face, framed by glossy chestnut hair. Her eyes. Once they had left the forest gloom behind, he had discovered her eyes were a changeable hazel—now amber, now jade green shot with gold, depending upon her surroundings. And yes, that pair of soft lips his squire had compared to rosebuds, curse him. His loins ached as he thought of kissing those lips.

Well, he never would. He had no time for marriage, and hadn’t Gisele herself indicated she wanted no part of the wedded state? She wanted to be free and independent of either a husband’s control or that of the Church. Good luck, my lady, for I doubt you will find such a state anywhere in Christendom!

“I can see the alestake from here, Maislin,” he said, when they were halfway across the bridge to Southwark. He was determined to eject Gisele from his mind.

“Aye, my lord.”

Glancing over at the young giant, he saw that his squire’s eyes were fixed firmly between his mount’s ears. He had looked neither to the right nor the left, even when Brys had spoken. Brys felt shame stab at him. His squire was as strong as a young ox, and excelled at swordsmanship, yet his feelings were as easy to hurt as a puppy’s.

“Isn’t that the alehouse with the buxom serving wench you had your eye on last time we passed this way, Maislin? Here, tuck this into her bodice—” he held out a silver penny “—and I’ll wager she’ll invite you to the back chamber where she can serve you more privately.”

Maislin brightened immediately. “Thank you, my lord! I have no doubt she will! But…what of you, Lord Brys? She had a cousin working there too, as I recall…a cuddlesome thing nearly as pretty as she, if you don’t mind the pox scar on her cheek—I’m sure she’d do the same for you, my lord….”

Brys smiled. “No doubt, but I’ll just drink my ale while you…ah…sate another appetite.”

“Why do they call the empress ‘Domina?”’ she asked, not only because she wondered, but because she wanted to slow the chamberlain down. He set a quick pace in spite of his short legs.

“Because ’tis the proper title for a queen before she has been crowned,” Talford said, as if Gisele should have known it. “Until her coronation, she is ‘Domina’ or ‘the Lady of England’—or one uses her former title of Empress.”

“I see,” Gisele said, trying not to pant.

“It is to be hoped one of the other ladies can furnish you with a suitable gown, until you can obtain some of your own,” Talford sniffed, eyeing her brown bliaut with distaste.

Gisele said nothing. She guessed the supercilious chamberlain had been listening when the empress was told about the attack in the Weald.

He sniffed again as they stopped in front of a door. “Here is your chamber. You will share it with Lady Manette de Mandeville.”

De Mandeville—the empress had mentioned that name. Ah yes, Geoffrey de Mandeville, the man whom Matilda had claimed worked a miracle by getting the Londoners to let her in.

“She is the daughter of Lord Geoffrey de Mandeville?”

“Lady Manette is the niece of the Earl of Essex—or at least ’tis what I’ve been told,” the chamberlain said, lifting a brow as if he doubted the relationship—making Gisele wonder why.

He knocked at the door, but no one answered within. He knocked again, harder this time, and from inside the chamber came a breathless, muffled shout: “Go away!”

Talford’s face hardened and he rolled his eyes heavenward. “It is I, Talford! Lady Manette, you must open this door!” He added softly, as if to himself, “And there had better not be anyone in there with you.”

Gisele heard a scuffling within, and a muttered curse in a voice which sounded too deep to be a woman’s, then a rustling as though someone walked across rushes toward the door. A moment later it creaked open, revealing a heavy-lidded flush-faced blond girl whose hair had mostly escaped the plait that hung to her slender waist. A heavily embroidered girdle was only half-tied at her hips.

“Yes?” she said, her gaze flicking from Talford to Gisele and back again.

“I did not truly did not think to find you here at this hour, my lady.”

Manette de Mandeville raised a supercilious pale brow.

“You knocked on the door and called my name, but you did not think to find me here?”

“It is past midday, my lady. I did not think to find you abed,” he said in his sententious way, nodding toward the interior, where bed with rumpled linens was clearly visible from the corridor. “I knocked only as a courtesy. I thought you would be about your duties with the rest of the empress’s ladies.”

“I was ill,” Lady Manette said, a trifle defensively. “My belly was cramping—my monthly flux, you know. And now,” she said, glancing meaningfully over her shoulder at the bed, “if you will excuse me…”

Gisele watched, fascinated, as the chamberlain’s face turned livid, then crimson.

“Such plain speaking is neither necessary nor becoming of one of the empress’s ladies,” Talford reprimanded her. “And I regret that you will have to rise to the occasion despite your um…ill health. The empress’s new lady has arrived, and she is to share your chamber. Not only that, but you will need to find her something suitable to wear—immediately,” he added, as Manette opened her mouth and looked as if she were about to protest. “Lady Gisele de l’Aigle has fallen upon misfortune and has naught but what she is wearing, and that will never do in the hall at supper, as I’m sure you can see.”

Manette’s eyes, which had only briefly rested upon Gisele, now darted back to her and assessed her frankly. “Ah, so you’re the heiress from Normandy,” she murmured in her sleepy, sultry voice. She looked at least mildly interested. “Well, in that case, you may come in,” she said to Gisele. “She’ll be fine, my lord,” she added, waving a hand dismissively at the chamberlain, who once again sniffed and stared as Manette took hold of Gisele’s hand and pulled her none too gently inside, then shut the door firmly in Talford’s face.

“The pompous old fool,” she said, jerking her head back toward the door to indicate the chamberlain.

Gisele was not sure how she should reply to that, although she’d found the chamberlain’s manner annoying, too. “I regret to disturb you while you are ill, Lady Manette,” she began diffidently. “If you will but indicate where the rest of the empress’s ladies are working, I will join them and you can go back to bed—”

A trill of laughter burst from Manette. “Oh, I’m not truly ill, silly, unless you count lovesickness! That was but a ruse to get Talford to leave the quicker! I thought if I embarrassed him enough—but never mind.” She went to the bed, and bent over by it, raising the blanket that dangled from the bed to the rushes. She said something in the gutteral tongue Gisele knew was English, though she didn’t understand it.

A moment later, a lanky, flaxen-haired youth crawled out from under the bed, and blinking at Gisele, bowed, then straightened to his full height, looking at Manette as if for direction.

“This is Wulfram. A gorgeous Saxon, isn’t he?” drawled Manette in Norman French, running a hand over the well-developed youth’s muscular shoulder. “And speaks not a word of French, so we may discuss his attributes right in front of him and he’ll never know. Nay, I wasn’t ill—Wulfram and I were just indulging in a little midday bed sport. Wulfram is um…very talented at that. Is he not handsome? A veritable pagan Adonis, if one may call a Saxon by a Greek name?”

The lanky Saxon looked distinctly uncomfortable, and Gisele was sure he had a very good idea that he was being discussed, even if he did not speak French.

Gisele, feeling the flush creeping up her cheeks, cleared her throat. “Yes…very handsome.”

She was startled when the Saxon extended his hand, touching her scraped cheek with unexpected gentleness. He asked Manette something.

“Wulfram wants to know what happened to you. He asks if ’twas over-rough lovemaking?” She giggled.

Gisele found herself flushing at the Saxon’s supposition. “Nay!” she said, then quickly told the other girl about the attack.

“Oh.” Manette seemed disappointed as she translated for Wulfram.

“I am intruding upon your…time together,” Gisele said. “Perhaps I might share another lady’s chamber, so you are not forced to…interrupt your trysts with Wulfram?” She started for the door, determined to escape this embarrassing situation.

Manette laid a detaining hand upon her wrist. “Nay, stay,” she said, laughing as if Gisele had said something hilarious. “It was inevitable I should be made to share with some lady sooner or later, as some of the other ladies are three to a bed! Besides, Wulfram and I can resume our play another time. We can work out an arrangement, you and I, so that neither of us interrupts the other in this chamber when we have male…company.”

Gisele felt her jaw drop open. “But I shall not be doing any such…” She couldn’t find a polite word for what she meant. Manette’s behavior was beyond her experience.

Manette’s eyes narrowed, and she studied Gisele again. “A virtuous demoiselle, are you? Never mind, you may begin to see things differently here, as you meet the courtiers about the empress. Or not,” she added with a shrug, as Gisele opened her mouth to deny it. “In any case, we shall get along very well, you and I. And you must not join the other ladies—they’d devour you, in your present state, dear Gisele,” she said, indicating the travel-stained gown. “It will take us the rest of the afternoon, but that will be sufficient, since Wulfram is here to fetch the seamstress to alter one of my gowns to fit you. I am bigger here than you,” she said, indicating Gisele’s bust, so that Gisele, aware that Wulfram was watching, blushed all over again. “But you have a lissome figure nonetheless. You will have knights and lordlings agog to meet you.” She rattled off something in English to the flaxen-haired lackey, then turned back to Gisele. “I told him to fetch Edgyth the seamstress, and have a wooden tub and hot water brought for a bath.”

Chapter Five

Two hours later, Gisele had bathed, submitted to Manette’s washing her hair, and donned the gown of mulberry-dyed wool the other girl had given her from her own wardrobe.

“Turn around and let me see,” Manette commanded.

Obediently, Gisele twirled around, feeling the pleated wool skirt bell around her, then settle against her legs. The gown had smooth, close-fitting sleeves with inset bands of embroidery just above the elbow; below the elbow the wool fell into flared pleats that came to mid-forearm in the front, and fingertip length in the back, revealing the tight sleeves of her undergown. Bands of embroidery that matched those on her upper arms circled her bodice just below her breast and made up the woven girdle that hung low on her hips. Her hair had been parted in the middle and encased in mulberry-colored bindings. Manette had even furnished her with a spare pair of shoes to replace her other pair, of which the left one had been clumsily repaired by the monks.

“Your hair is so thick and long, it doesn’t even need false hair added to lengthen it to your waist, as most of the ladies at court must do,” Manette approved, reaching out a hand to bring one of the plaits which had remained over Gisele’s shoulder when she had whirled around, back over her breast.

“Thank you—for everything,” Gisele said, a bit overwhelmed by the girl’s generosity. “I will return the gown to you as soon as I am able to purchase cloth and sew my own….”

“Pah, never mind that,” Manette said with an airy wave of a beringed hand. “’Twas one I was tired of, for the color looks not well with my fairness.” She patted her own tresses, in which the gold was supplemented, Gisele guessed, with saffron dye.

“And now for the finishing touch.” Reaching into a chest at her feet, Manette brought out a sheer short veil, which she placed atop Gisele’s hair, then added a flared and garnet-studded headband that sat on Gisele’s head like a crown.

“Ah, no, Manette, ’tis too much,” Gisele protested, reaching up to remove it. “I could never accept such a costly—”

“Don’t worry, silly, the headdress is but on loan,” Manette said, laughing at her as she reached out a hand to forestall Gisele from removing it. “Uncle Geoffrey is sure to find you very attractive, and that is all to the good,” she added in a low murmur, as if to herself. Her green eyes gleamed.