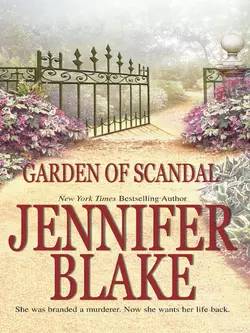

Garden Of Scandal

Jennifer Blake

Laurel Bancroft has lived for years as a recluse, isolating herself from a town that has branded her a murderer.But now, convinced people have finally forgotten, she is ready to resume her life. Then Laurel meets Alec Stanton. Hired to help redesign her garden, Alec is a stranger with a mysterious past. Though more than ten years younger, Alec is exactly what Laurel needs: intelligent, talented, passionate.But as their relationship grows, so does a dangerous threat against them. Someone wants Laurel to return to her seclusion and give up her younger lover–someone who hasn't forgotten that night so many years ago.

It wasn’t so easy to shut away the memory of the afternoon before.

If she closed her eyes, Laurel could still feel Alec’s arms around her, feel the disturbing moment when she had pressed against the hard warmth of his body. It had been like standing at the center of a lightning strike, caught in the flare of white-hot heat, blinding light and searing power. Nothing had prepared her for the conflagration, or for the rush of need that poured through her in response. She had been stunned, held immobile by feelings so long repressed, she had forgotten they had existed. If she had ever known them.

She wasn’t sure she had. Even in the days when she was first married, when loving was so strange and new, she had not felt so fervid or so uncertain of her own responses, her own will.

No. She wouldn’t think about it. She would forget she had ever touched Alec Stanton. And she would pray to high heaven that he did the same.

“Full of passion, secrets, taboos and fear, Garden of Scandal will pull you in from the start as you work to unwind the treachery and experience the sizzle.”

—Romantic Times

GARDEN OF SCANDAL

JENNIFER BLAKE

For my husband, Jerry, with loving appreciation

for the man who, at our home known as

Sweet Briar, constructed the real garden of antique

roses that provided the inspiration for this book.

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

1

She tore out of the lighted house like a banshee. Screaming in a shatteringly clear soprano above the growling of the great black German shepherd, she skimmed across the front porch. She was halfway down the high steps before the ancient wooden screen door slammed shut after her.

Part harridan, part avenging Valkyrie, she raced toward him wearing a nightgown with light streaming through it from behind. Her long hair shifted and whipped around her, shimmering silver-gold in the moonlight. Her feet barely touched the ground. Fleet, slender, with the pure lines of her face twisted in concern, she was the most fascinating thing Alec Stanton had ever laid eyes on.

“Sticks! Here, boy!” she called out as she ducked under the low-hanging limb of a magnolia, dodged the rambling branches of a spirea. Her gaze was riveted on the dog standing ferocious guard on the mossy brick walk.

The German shepherd growled, a ragged warning that resonated deep in his massive chest. His eyes never left Alec. He lifted his ruff, baring his teeth in challenge. As the woman came nearer, the animal moved protectively to block her path with his body.

“What is it, boy? What have you got cornered?” Her voice was anxious but not fearful as she slowed her pace. Then she saw Alec.

She stopped so quickly that her hair swirled forward, covering her arms like a cape of captured moonbeams. Her hands clenched into fists. Her eyes widened. She squared her shoulders, then stood so motionless she might have been turned into pale, warm marble.

The dog ceased to exist for Alec. And he forgot why he was there amid the tangled briers, vines and overgrown shrubbery that were the front garden of the Steamboat Gothic mansion known as Ivywild. Moving like a man in a daze, he stepped forward out of the night.

The German shepherd launched off his haunches in attack. Eighty pounds of hard muscle and death, he sprang straight for Alec’s throat.

“Down! Down, Sticks!” The woman’s shout mingled with the dog’s snarl. Yet there was no hope the animal would, or could, obey.

Alec’s instinct and training kicked in. He spun away as the dog hit him, moving with the force of the assault, flowing with it to lessen the impact even as he snatched the dog’s huge black head in an iron grip. Finding the pressure points, Alec drove his thumbs against them. He sank to his knees, still turning, flexing hard muscles as he came about in a full circle.

It was over in a moment. When Alec rose, the animal was stretched out, limp and barely breathing, on the walk between him and the woman.

She moaned and dropped to the ground, gathering the lolling head of her guard dog into her lap. Holding tight, she rocked back and forth.

“He’ll be all right,” Alec said with stringent softness.

She made no reply. Then he heard the catch in her breathing as the dog stirred, whimpered.

Abruptly, she looked up with the wetness of tears glittering in her eyes. “You might have killed him!”

“If I’d wanted to kill him he’d be dead. I just put him out for a few minutes while we get things cleared up here.” Alec could have pointed out that her precious Sticks might have crushed his throat, but it didn’t seem worth the effort.

Her fingers sank into the dog’s coat, holding him closer. “You’re on private property. I want you off in the next two seconds or I call the police. Is that clear enough for you?”

This was not the way things were supposed to go. He had meant to knock politely, then stand outside on the porch while he spoke his piece. He hadn’t expected to feel his heart squeezed in a breath-catching vise at the sight of a woman’s form in a whisper-thin nightgown. He had never dreamed it could happen—not to him, and especially not here with this woman. It was too unexpected for comfort, much less acceptance.

Putting her pet out cold was not a good start, no matter what he had in mind. “I’m sorry if I hurt your dog,” he said.

“Oh, yes, I can tell!” The look she gave him was scathing.

“He shouldn’t have attacked.”

“He was just—He thought I needed protecting.”

It was entirely possible the dog had been right. Wary and off-balance, Alec tried again, looking for some kind of stable ground. “You’re Mrs. Bancroft, Laurel Bancroft?”

“What of it?”

“I…wanted to talk to you.” That had been his original purpose. Things had changed. For what good it would do him.

She didn’t give an inch. “I can’t imagine we have anything to discuss.”

“The lady who keeps house for you, Maisie Warfield, is a good friend of my grandmother’s. She said you need help clearing this jungle of a garden, that it had more or less gotten away from you since your husband died.” His grandmother had said a great deal more. He should have paid attention, he thought, as he added, “I have a little experience with that kind of work.”

She watched him for several seconds, her expression intently appraising. Then she said in disbelief, “You’re Miss Callie’s grandson?”

Stung by the amazement in her tone, he made his agreement short.

“You’re no gardener!”

He shook his head. “Engineer. But I worked as a yardman to put myself through school.” He gave the words a hint of an edge to let her know he didn’t care to be prejudged.

“I can’t afford an engineer,” she said baldly.

He considered telling her she could have his services for free—any service she wanted, any time. But that wouldn’t work, and he still had sense enough, just, to know it. “Manual labor at the going rate is what I’m offering.”

“Why?”

The single word hung between them for a moment as Sticks lifted his head and shook himself before turning to lie on his belly. The dog looked up at Alec, then away again, as if embarrassed. Whining, he crawled forward a few inches to lick his mistress’s hand in apology.

Watching the animal with a hot sensation very like envy, or even jealousy, pervading his skull, Alec said, “A lot of reasons, but let’s just say I need the money.”

“You can get a better job anywhere else.”

“I need to hang loose, not be too tied down.”

Her gaze was concentrated as she smoothed her hand over the dog’s head in a gesture of comfort, then got to her feet. “Because you don’t like wearing a suit? Or is it your brother?”

“Both.”

She knew all about him and Gregory; he might have guessed. That was one of the glories of small towns. Also their major pain in the backside.

He allowed his eyes to glide over her, then away. But he could still see the slim moon-silvered shape of her burning in his mind like a candle flame. He swallowed hard.

“If you expect me to be sympathetic—” she began.

“No.” He made an abrupt, slicing gesture. “Sympathy is something we don’t need. Either of us.”

She stiffened. “My situation has nothing to do with you!”

He looked back at her, speaking gently as he tilted his head. “I meant my brother and myself. Though I guess it would be safe to include you in it, too.”

She didn’t answer; only stood staring up at him. The moonlight washed across her features, highlighting the scrubbed freshness of her skin that was so translucent it responded to every shift of emotion beneath its surface. He could see the blue of her eyes, wine-dark as the Aegean Sea, yet clear, as if she knew more than she wanted to about people. Particularly men and their baser urges.

His were the basest of the base.

She had just come from a shower, he thought; he could smell the fresh soap and clean-woman scent of her. It was as potent an aphrodisiac as any he had ever imagined. He ached with it, hardening beyond comprehension from no more than sharing the same warm night air.

She seemed fragile, yet there was inner strength in the way she stood up to him, a stranger in the dark. She was real—a little shy, but self-possessed to the point of being regal. She wasn’t perfect; there were fine lines at the corners of her eyes, and her upper lip was not quite as full as the lower. She was almost perfect, though, so close to beautiful that it was nearly impossible to look away from her.

It wouldn’t do. She’d never have anything to do with Callie Stanton’s California-hippie grandson. To her, he must look like a kid with more brawn than brains. It was downright funny, if you thought about it. Only he wasn’t laughing.

Laurel shivered a little under the impact of Alec Stanton’s gaze. His eyes were so black, the pupils expanding, driving out all color, leaving still, dark pools of consideration. He was tall and broad, a solid presence holding back the night that crowded around them. She knew instinctively he would be more than able to protect her from whatever might be lurking in the darkness. Yet she did not feel safe.

He was too big, too strong, too fast. The defense he had made against poor Sticks was some dangerously competent form of martial arts; she knew enough to recognize that much even if she didn’t know what to call it. Beyond these things, he was far too exotic with his long black hair tied back in a ponytail with a leather thong, the dark ambush of his thick brows and lashes in the strong square of his face, and the silver slash of an earring shaped like a lightning bolt that was fastened in his left ear.

He was dressed entirely in black: boots, jeans, and a sleeveless T-shirt that emphasized the sculpted muscles of his torso. The skimpy shirt also exposed the multicolored stain of an intricate tattoo on his left shoulder, dimly recognizable as a dragon winding across his pectoral and around his upper arm.

As she avoided his black gaze, her eyes flickered over the tattoo, then back again. Her fingers tingled, and she curled them tighter into her palm against the sudden impulse to touch the dragon, stroke the warmth and smoothness of its—his—skin and feel the power of the muscles that glided beneath the painted design. If she tried, she might be able to span the beast with her spread hand, feeling its heartbeat under her palm where the pumping heart of the man lay beneath the wall of his chest.

She drew a sharp breath, snatching her mind from that image as if backing away from a hot stove. She must be crazy. At just over forty-one, she was at least ten years older than he was, maybe a little more.

She had been alone too long, that much was plain. She had grown so used to her solitude and isolation here at Ivywild that she had come flying out of the house in nothing more than her nightgown. Worse than that, she was having wild fantasies simply because she was alone with an attractive man. Definitely, she was losing it.

The warm spring night pressed against her, as if driving her toward the man in front of her. She could smell the wafting fragrance of magnolia blossoms from the tree that loomed above them. The chorus of night insects was a quiet and endless appassionato, an echo of the feelings that sang through her.

At her feet, Sticks struggled upright, then stepped forward to press against her knee. The movement was a welcome release from the curious constraint that held her.

“Look,” she said abruptly, her voice more husky than she intended. “All I had in mind was hiring some older man to cut down a few trees, hack back the brush, maybe dig a rose bed or two—”

He cut across her words in incisive tones. “I can do twice as much in half the time.”

“I’m sure you could, but the point is—”

“The point is you’re afraid of me. I don’t suit the notions of backward, provincial Hillsboro, Louisiana, about how a man should look. I’m not your average redneck—crew-cut and squeaky clean, with nothing on his mind except fishing, hunting and drinking beer. Or at least, nothing he can share with a woman. I don’t fit.” His voice softened. “But then neither do you, Laurel Bancroft.”

Her lips tightened before she opened them to speak. “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“Don’t you?”

The smile that accompanied his inquiry lasted only an instant. Yet the brief movement of his mouth altered the hard planes and angles of his face, giving him the devastating attraction of a dark angel. There was piercing sweetness in it, and limitless understanding. It saluted her independence even as it deplored it, applauded her courage in spite of her intransigence. It plumbed her loneliness, offered comfort, promised surcease.

Then it was gone. She fought the chill depression that moved over her in its wake. And lost.

On a deep breath, she said, “That isn’t it—or at least I’d like to think I’m not so petty. But I don’t need any more problems right now.”

“You need help and I need money. We’re a natural.” His words were even, an explanation rather than an appeal.

She flung out a hand in exasperation. “It isn’t that simple!”

“Not quite. My brother has cancer in the final stages. Did you know that? I took unpaid leave from the firm where I work in L.A. to come visit Grannie Callie with him. Now he wants to stay. Good home-cooked food and quiet living may help or may not, but at least it’s worth the chance. Still, I’ll be damned if I’ll live off my grandmother’s charity. I could get a more permanent—not to mention better paying—job, yes. But I’d have to be away all day, and that’s not what I need. Your place is close, the work shouldn’t be too confining. I’m a fast worker, I get the job done and I’m not too proud to follow orders. I know a rose from a rutabaga, and I can lay brick, pipe water, whatever it takes. What more do you want?”

What more, indeed? Nothing, except to listen, endlessly, to the deep, steady timbre of his voice. Which was reason enough to be wary.

“It’s just a small project,” she said. “I might install a little fountain in the middle of the roses after things are cleared away, but it’s not really worth your time, much less your skill.”

His smile came again, warming her, enticing her against her will. “Neither are worth all that much just now. They’ll be worth even less if you turn me down.”

“I don’t think…”

“Tell you what,” he said, easing forward. “I’ll work the first day for free. If you decide I’m no use to you, that’s the end of it. If you like what I’ve done, we’ll take it from there.”

“I can’t let you do that,” she said in protest.

“A fair trial, that’s all I ask. Starting at eight in the morning. What do you say?”

She was definitely crazy, because the whole thing was beginning to sound almost reasonable. What was the difference between hiring him or old man Pender down the road, or even young Randy Nott who did odd jobs for her mother-in-law? This man would be hired help, a strong back and pair of able arms. Probably more than able, but she wouldn’t think about that. A couple of days, maybe a week, and then he would be gone.

In sudden decision, she said, “Make it seven, to get as much done as possible before it gets too hot.”

“You’re the boss.”

Somehow, she didn’t feel like it.

He nodded once, then moved away, melting into the darkness along the overgrown path toward the drive. After a moment, Laurel heard the low rumble of a motorcycle being kicked into life. Then he zoomed off in a blast of power. The noise faded and the night was still again.

A shiver moved over her in spite of the warmth of the evening. She clasped her arms around her, holding tight. Sticks looked up, whining, as he picked up on her disturbance.

“What do you think, boy?” she asked, the words barely above a whisper. “Did I make a mistake?”

The dog gave a halfhearted wag of his tail as he stared in the direction Alec Stanton had gone.

She sighed and closed her eyes. “I thought so.”

Her new hired hand was on time the next morning—Laurel had to give him that much. She had barely pulled on her old jeans and faded yellow T-shirt when she heard his bike turn in at the drive.

Maisie Warfield, her housekeeper, hadn’t arrived yet, since she always had to get her “old man”—as she called her husband who was nearing retirement age—off to work before she could show up. Rather than waiting for Alec Stanton to come to the door and twist the old-fashioned doorbell, Laurel picked up her sneakers and moved in her sock feet toward the side entrance. At least she didn’t have to worry about Sticks. He had spent the night on the screened back veranda and was still shut up out there.

Alec Stanton was not on the drive where his bright red Harley-Davidson leaned, looking as out of place in front of the old, late-Victorian house as a ladybug on the hem of an ancient lace dress. Nor was he in the tangled front garden. However, a ripping, shredding sound led her to the side of the house. He was already at work there, tearing a clinging green curtain of smilax and Virginia creeper away from the overlap siding.

He looked around at her approach. His nod of greeting was brief before he spoke. “The whole place needs painting, though I can see at least a dozen boards that should be replaced first. You’ll lose more if you don’t protect them soon.”

“I know,” she said shortly.

“I could—”

“I can take care of it,” she said, cutting off the offer he was about to make. “You’re here for the garden.”

He yanked down a long streamer of smilax and let it fall, leaving it to be dug up by the roots later. Stripping off his gloves, he tucked them into the waistband of his jeans. He ran a critical eye over the house, which loomed above them, with its balustraded verandas that were rounded on each end in the style of a steamboat, its gingerbread work attached to the slender columns like ice-covered spiderwebs, and the conical tower set into the roofline. “It’s a grand old place,” he said. “It would be a shame to let it fall into ruin.”

“I don’t intend to,” she answered tartly. “Now, if you’ll…”

“Your husband’s old family home, I think Grannie said. How did you wind up with it?”

“Nobody else wanted it.”

That was the exact truth, she thought. The place had been the next thing to abandoned when she first saw it. Her husband’s mother, Sadie Bancroft, had moved out not long after her husband left her back in the sixties. His sister Zelda had no interest in it; she’d had more than enough of the big barn of a place as a child and couldn’t comprehend why Laurel had begged to buy it from the family after she and Howard were married. Even Howard had grumbled about the upkeep and often talked of trading it in for a small, neat ranch-style house during the fifteen years they were married. But that was all it had been—talk.

“It’s mighty big for one person.”

“I like big,” Laurel said and felt a sudden flush sweep over her face for no reason that made any sense. Or she hoped that it didn’t, although that seemed doubtful, considering the ghost of a smile hovering at one corner of Alec Stanton’s mouth.

“Where shall I start?”

“What?”

He tilted his head. “You were going to tell me where to start to work.”

“Yes. Yes, of course,” she said and spun around, leading the way toward the front garden.

She had meant to help him, in part to be on hand to point out what she wanted to keep and what needed to go. She soon saw that it was unnecessary. He knew his plants and shrubs; his time as a yardman had been put to good use. He was also efficient. He didn’t start work until he had checked out the tools in the shed behind the detached garage, then oiled and sharpened them.

“You could use a new pair of hedge shears,” he suggested as he ran a callused thumb along the edge of a wide blade. “It would make your job around here a lot easier.”

He was right, and she knew it. “I’ll tell Maisie to pick them up next time she goes into town.”

“You’re also out of gas for the lawn mower.”

“She can get that, too.”

He studied her for a moment, his eyes as dark and fathomless as obsidian. “You know you have a flat on your car? And the rest of the tires are so dry-rotted you’d be lucky to get out of the driveway on them.”

“I don’t go out much,” she said, avoiding his gaze.

“You don’t go at all, to hear Grannie tell it—haven’t left this place in ages. All you do is read and make clay pots in the shed out behind the garage. Why is that?”

“No reason. I just prefer my own company.” She gave him a cool look before she turned away. “I’ll be in the house if you need anything.”

To retreat was instinctive self-protection, that was all. She didn’t have to explain herself. Certainly it was none of this man’s business whether she went out or stayed home, worked with her pottery or flew to the moon on a broomstick. Nor did she need someone watching her, giving unasked-for advice, prying into her life. She would pay him for what he did today, regardless of what he had said, then send him on his way. She had gotten along without Alec Stanton before he came, and she could get along without him when he was gone.

As the day advanced, however, it could not be denied that he was making progress. He cut away dozens of pine and sassafras saplings from the old fence enclosure, exposing the unpainted pickets almost all the way across the front of the garden. He rescued and pruned the Russell’s Cottage Rose in the corner, tearing out a head-high pile of honeysuckle vines in the process. An arbor and garden bench of weathered cypress were unearthed from a covering of wild grapevines. And the debris from his efforts was thrown into a pile that made a slow-burning green bonfire. The gray pall of smoke rose high enough to cross the face of the noonday sun.

Laurel tried not to watch him. Yet against her best intentions it seemed everything she did took her near the front windows of the house. It was only natural to look out. A perfectly ordinary impulse. That was all.

He had removed his shirt in the middle of the morning. A sheen of perspiration gilded the sun-bronzed expanse of his back, shimmering with his movements, while dust and bits of dried leaves stuck to the corded muscles of his arms. The soft hair on his chest glinted like damp velvet, making a conduit for the trickling sweat that crept down the washboard-like ridges of his abdomen to dampen the waist of his jeans. He was hot and sweaty and dirty and magnificent. And she disliked him intensely for making her aware of it.

The last thing she wanted was to think about a man—any man. She had gotten along fine without being reminded of the male race; had hardly thought of love or sex since her husband had died. To be forced to return to all that now would not be helpful. She wouldn’t do it, she wouldn’t.

“I’ve got cold roast chicken and fruit salad for lunch,” Maisie said from behind her. “You want I should serve it for you and Alec out on the veranda?”

Laurel swung to face the housekeeper with guilty color flooding her face. Maisie Warfield, rotund and white-haired, stood in the doorway that led from the dining room to the parlor. She wiped her wet hands on a dish towel as she studied Laurel. There was a shrewd look in the snapping blue of her eyes, and faint amusement crinkled the tanned skin around them into shallow wrinkles.

“No. No, I don’t think so,” Laurel replied. “You—can take him a sandwich and a cold drink.”

Maisie’s smile faded and she set her hamlike fist that held the dishcloth on a padded hip. “Why? You got something against Alec?”

“Of course not. I just prefer my privacy.” Laurel turned back to the window, ignoring the other woman’s stern gaze.

“He’s not going to bite.”

A wry smile curled Laurel’s lips. “How do you know?”

“What?”

She turned to give her housekeeper a straight glance. “I said, yes, I know. But I still don’t intend to eat with him. Or anything else.”

“You’d rather stay shut up in this house instead of keeping him company.”

“That’s about it.”

The housekeeper shrugged. “You don’t know what you’re missing.”

Laurel made no reply. She was too afraid Maisie might be right.

2

Alec worked like a man possessed, slashing and hacking and piling brush without letting up. The sun burned down on his head. Sweat poured off him in streams. He tied a bandana around his forehead and kept working. His shirt grew soaked, clinging to him, confining his movements. He stripped it off and kept working. He could feel the sting of long scratches on his arms from his bout with forty-foot runners from an ancient dog rose. He ignored them and kept working.

He didn’t care about any of it. It was good to use his muscles, to feel them heat up until they glided and contracted in endless rhythm, responding effortlessly to his need. He liked the heat of the sun on his back, enjoyed the smells of cut stems, disturbed earth and smoke. It gave him a sense of accomplishment to rescue antique shrubs and perennials, to watch some semblance of order emerge from what had been a confused mess.

He had to prove himself to make sure he got this job, but there was more to it than that. He needed to show Laurel Bancroft that he was as good as any redneck at achieving what she needed done.

He had thought from the way she was dressed this morning that she might work with him. He had been looking forward to the prospect. But she had gone inside the house and shut the door. He hadn’t caught so much as a glimpse of her since.

She was good at closing herself off, from all accounts. Grannie Callie had said she’d hardly left this old place since her husband had died. People seemed to think she had gone a little peculiar. Not crazy, exactly, but not your average grocery-shopping, soaps-watching, club-and-tennis young matron, either.

The kind of work he was doing didn’t take a great deal of concentration, and his mind had a tendency to wander. If he let himself, he could see Laurel Bancroft as some kind of enchanted princess under a spell; she had that fragile look about her. She was trapped in her castle of an old house, drugged and sleeping while life passed her by. And he was a knight-of-old come to hack his way through the thorns and briers to save her.

Jeez, he must be losing it.

Some knight. No armor, for one thing. A pair of hedge clippers in his hands instead of a sword. Hardly perfect, either. And he was definitely not pure.

A screen door slammed at the side of the house. Maisie rounded the corner and leaned over the railing.

“Lunchtime, boy,” she called. “Sandwiches up here on the veranda. You want water or tea?”

He stopped, wiping sweat from his eyes with his forearm before he frowned up at her. “‘Boy’?”

She gave him a grin that put a thousand wrinkles in her face and made him feel good inside. “You don’t like that? I could have called you dummy for being out in this sun without a hat. Water or tea?”

“Water.” He should have known better than to try intimidating a woman who claimed she had changed his diaper when he was a kid. “Where’s Mrs. Bancroft?”

The elderly housekeeper’s gaze slid away from his. “She don’t eat lunch. You want to wash up, there’s a bathroom off the kitchen.”

It looked as if Laurel Bancroft was avoiding him. He didn’t know whether that was good, because it was a sign that he disturbed her, or bad, because it meant she couldn’t stand him. Either way, he was going to have to do something about it.

At least Maisie didn’t desert him. She brought her chicken salad and tea out to the table on the shady front veranda. While he ate, he teased her about her diet fare and how much her old man was going to miss her curves when they were gone. After a while, he got around to what he really wanted to say.

“So what is it with the lady of the house? Is she a recluse or just stuck-up?” He leaned back in his chair, rubbing the condensation from the sides of his water glass with his thumb while he tried to look bored and a little disgusted.

Maisie gave him a narrow look. “She doesn’t have too much for people, is all.”

“How’s that?”

“Her husband died, you know that?”

He nodded as he massaged the biceps in his right arm that had begun to tighten on him.

“Did you know she killed him?” she asked.

Shock brought him upright. “You’re bullsh—I mean, there’s no way!”

“She did it, God’s truth,” Maisie said with a shake of her head. “Not that she meant to. He stepped behind her car as she was backing out of the garage. But there were folks who claimed it was on purpose. The mother-in-law, for one.”

“Nobody else believed it, though, right? I mean, just look at her. How could they?”

“Some people will believe anything. Anyway, seems Laurel and Howard had been having problems. Then there was a big life-insurance policy.”

“But nothing came of it?”

“Nothing official, no investigation. Sadie Bancroft, the husband’s mother, said it was on account of Sheriff Tanning being Laurel’s old boyfriend. Maybe, maybe not. I don’t know. Anyway, it blew over.”

“Except for the gossip?”

“Yeah, well, there’s always that part.”

He tilted his head. “So she’s hiding out. But why, if she really didn’t mean to do it?”

“You want to know that, you’ll have to ask her.”

Maisie was avoiding his gaze. Alec wondered why. “Think she’ll tell me?”

“Might.” The older woman stood and began stacking dishes. “Depends maybe on how you go about it and why you want to know.” She walked off with her load, leaving him to himself.

Alec sat on for a few minutes, drinking water as the ice melted in his glass, and gazing out over the garden at what he had done and what he still needed to do. From up here, he could see the outlines, barely, of what had been a typical front yard in the old days. It had been fenced with white pickets to keep out the cows that ranged freely back then, with a gate accessing the driveway, which passed in front of the house, then made a sharp right turn into the garage that was separate from the house. A straight brick sidewalk cut from the front gate to the steps, and curving walkways followed the oval ends of the house around toward the back.

Planting had apparently been haphazard, except for the great treelike camellias and Cape jasmine at the fence corners and the roses along the pickets and over the arbors above the gates. He had found evidence of bulbs of all kinds everywhere, from daffodils and iris to licoris. Originally, the soil between the plantings would have been swept clean of every blade of grass and raked in patterns. Sometime in the forties or fifties, probably, Saint Augustine grass had been planted in the open spots. There were still patches of the thick sod here and there, although the rest was choked with weeds and briers and enough saplings to stock a small forest.

And he had to get after it. He drained his glass, picked up his sweat-damp gloves and went back to work.

Maisie left in the middle of the afternoon, flipping him a quick wave as she drove off in her old boat of a car. He dug up the tough tubers of a mass of saw briers that were trying to climb a column while he allowed a little time to pass. When he thought it might not look too much like he had waited for the housekeeper to leave before storming the house, he pulled his discarded shirt back on, then went and gave the antique brass doorbell a quick twist.

The harsh, discordant sound rang through the house, and from around back, Laurel’s German shepherd, smart dog that he was, started barking immediately. Earlier, Alec had seen Sticks shut up on the porch. The two of them had eyed each other through the screen. Leaning against the doorjamb now, Alec wondered whether Laurel Bancroft was protecting him from the dog or the dog from him.

Laurel didn’t want to answer the door. She felt threatened, almost beleaguered inside her own house. She wished she had never mentioned the garden to Maisie, then this Alec Stanton would never have shown up. She could have gone on as she had been for nearly five years, in comfortable solitude with little contact with the outside world beyond her housekeeper, her grown children, and the man who drove the brown truck that brought her mail-order purchases.

Catalogs had become her lifelines to the world. It was a catalog of antique roses from a place in Texas that had started her thinking about the garden again after all this time. Now look where it had gotten her.

It was a strange blend of fear and irritation that made her snatch open the front door after the third ring. Her voice sounding distinctly tight and unwelcoming, she said, “Yes?”

“Sorry to disturb you, ma’am,” the dark-haired man who leaned on the doorjamb said, “but I needed to ask a couple of questions.”

He wasn’t sorry at all; she could see that. What she couldn’t see was why he couldn’t have come to the door before Maisie left. The urge to slam it in his face was so strong, a tremor ran down her arm. The main thing stopping her was the suspicion that he might prevent it if she tried.

Through compressed lips, she asked, “What is it?”

“I wondered if you could show me where you want your fountain? And it would help if I had some idea how you’d like to lay out the rose beds you mentioned. Plus, I’m not exactly sure what to save and what to get rid of.”

She glanced at the yard beyond him with a doubtful frown. “Surely you haven’t got as far as all that? I thought you were just clearing and cleaning.”

He smiled, a lazy movement of sensuously molded lips that made her breath catch in her throat. “It always helps to have a plan. Would you mind stepping out here just a minute to tell me a couple of things?”

How could she refuse such a polite and reasonable request? It was obviously impossible. In any case, she was intrigued by the clear line of sight he had created by fighting back the growth along the sidewalk from the steps to the gate. It had seemed a great distance between the two points before, when trees and brush had choked the passage and obscured the view. Now it appeared to be only a few yards.

Before she knew it, she had moved across the porch and down onto the brick path. Alec was talking, pointing out dying jonquil foliage along the walk, asking if she wanted to leave the yellow jasmine vine that had woven its way through a huge spirea near the side gate, and a dozen other questions.

She answered, yet she was painfully aware of being outside in the afternoon sun, exposed and vulnerable to another human being. At the same time, she felt a rising excitement. She could almost see the garden she had envisioned emerging from the shambles around her. In a single day, this man had laid bare the form of the front yard so she could tell how things used to be and how she wanted them again.

Roses. She wanted roses. Not the stiff, formal, near-perfect hybrid blooms everyone thought of when they heard the word, but rather the old Chinas, teas, Bourbons and Gallicas of years gone by. They were survivors, those roses. They had been rescued from cemeteries and around the foundations of deserted houses where they’d been growing, neglected, for countless years. Tough, hardy, they clung to life. Then in early spring, and even through the searing heat of summer and into fall, they unfurled blooms of intricate, fragile beauty, pouring their sweet perfume into the air as if sharing their souls.

Standing in the center of the front garden, Laurel said, “I’d like the fountain here, with the path running around it on either side, then on to the steps. I thought maybe an edging of low boxwood of the kind they have in French gardens would be good, with a few perennials like Bath’s pinks, blue Salvia and Shasta daisies. Beyond that, just roses and more roses.”

She glanced at Alec, half afraid she might have spoken too extravagantly. He was watching her with consideration in the midnight darkness of his eyes and a faint smile hovering at one corner of his mouth. For long moments, he made no answer. Then, as if suddenly becoming aware of her gaze, he gave a quick nod. “I can do that.”

“You think it will work?”

“I think it will be perfect.”

He sounded sincere, but she could hardly take it on trust. “You’re only saying that because you can see it will take weeks of work.”

His smile faded. “I wouldn’t do that. Actually, what I am is relieved. I was afraid you were going to want big maintenance-free beds of junipers all neatened up with chunky bark mulch.”

She made a quick face. “Too West Coast subdivision.”

“Exactly,” he agreed, his eyes warm and steady.

For a fleeting instant, she felt such a strong rapport with the man beside her that she was amazed. They were nothing alike, had little in common as far as background, yet they seemed in that moment to be operating on the same wavelength.

Perhaps this would work, after all. Just so long, of course, as they kept it simple and businesslike. She not only wanted this garden, she needed it. She had come to think, lately, that without it she might go into her house one day and never come out again.

“Let me show you something around here,” Alec said, intruding on her thoughts. Turning, he led the way toward the back of the house where the old outdoor kitchen had been before it was moved inside just before World War II. Her footsteps slowed as she saw where he was headed.

He kicked aside a tangle of brier and weeds, which he had apparently hacked down earlier at the house corner. Underneath was a low brick curbing covered by a large concrete cap. Moving with quick efficiency and lithe strength, he bent and lifted the heavy concrete cover. It made a harsh grating noise as he shoved it from the curbing.

“Don’t!” she cried, stepping back.

He straightened, putting his fists on his hips. “You know what this is?”

“A cistern, of course,” she answered, incensed. “But my husband never—That is, he always said it was extremely dangerous. No one ever goes near it.”

Alec frowned. “It’s just a brick-lined hole in the ground. There’s not even any water in it anymore.”

“Howard was always afraid somebody, one of the kids, would fall in.”

“Then he should have filled it in. But it could be used now as a reflecting pool, if you wanted. It wouldn’t take much to seal the brick lining, make it watertight.”

“It would be so deep,” she protested.

“So’s a swimming pool,” he offered with a shrug, “but that doesn’t stop people from having them. Anyway, it’s not as if there are any kids toddling around to fall in.”

She shook her head, suppressing a shiver. “I’d rather not.”

“Suit yourself. It was just an idea.”

He was disappointed, she thought. The enthusiasm had died out of his face and his movements were stiff as he replaced the heavy concrete cap. Abruptly, she asked, “Did you see the creek?”

“I saw where one crosses the road below here. That it?”

Nodding, she led him toward the winding waterway that ran behind Ivywild, gliding among tall beeches, sweet bay trees and glades of ferns. She was halfway there before it came home to her what she was doing. She had actually left the fenced-in yard. She was moving farther away from the safety and comfort it represented with every step. How long had it been since she had done that so easily?

A shiver moved over her and the skin on the back of her neck prickled. She felt naked, as if she had deliberately abandoned her protective covering. Panic rose inside her, but she choked it down, breathing slowly in and out.

She would be all right—she would. The wide shoulders and hard body of the man at her side spelled protection. He was solid, like a wall or fence that stood between her and whatever danger might lie around her. She had felt it the night before, felt it even more strongly now.

Not that there was really anything out here, of course. Any jeopardy was all in her head, and she needed to get rid of it. She knew that and was determined to keep telling herself so until she believed it. Anyway, she would not be away from her house for long—only for the time it took to show Alec Stanton the small stream.

As she pushed on, moving ahead of him down the tree- and brush-covered slope, following a winding animal trail, she was hyperaware of the warmth and solidity of him beside her. He moved so quietly, with the natural grace of an Indian. In the dusky tree shadows, she thought she could see a copper tint in the deep bronze of his skin.

The awkwardness between them lingered, but it had a different quality from before. She couldn’t remember the last time she had been quite so aware of another human being. Nor could she recall the last time she had cared how any male felt other than her teenage son.

Alec was impressed with the creek. Standing knee-deep in the ferns that edged it, with his hair trailing in its damp ponytail down his back and leaf shadows making a tracery of gray dimness and golden light on his brown skin, he turned to her with a heart-stopping smile. Voice deep and reflective, he said, “This has possibilities.”

“I know,” she said and caught her breath, suddenly more afraid of those possibilities than she had been of anything in five long years.

He tilted his head, the darkness of his eyes as meltingly warm and sweet as chocolate. “Does this mean I get the job?”

He had done so much in so short a time. He could clear all the choking debris from Ivywild. He could make her rose garden for her. If she had not ventured out to see what he had done—what he could do—if she had not seen the promise, she might have answered differently. Now there was only one reply possible.

“Yes, I…suppose it must.”

Pleasure flared across his face in sudden brightness. “Good,” he said softly. “In fact, that’s great.”

Laurel wasn’t so sure.

She was even less certain when night closed in and Alec finally roared away down the drive on his Harley. She had grown used to being alone, and yet tonight she really felt it for the first time in ages. It was a warm evening, but she was chilled. Wrapping her arms around herself, she wondered what it would be like to have a man’s warm arms to hold her, or a firm chest to support her as she pressed close against it. It had been so long.

Of course, Howard had never been particularly good at simple affection. Whenever she’d tried to cuddle in his arms, she had usually gotten sex. That part of their marriage had been all right; not especially inspiring but no disaster, either. They had talked—mostly practical conversations of the kind necessary between husband and wife, about plumbing repairs, the children’s progress in school, what was for dinner. Sometimes they had gone out to eat or visited friends, driving home in companionable silence. Now and then, Howard had taken her hand. But no, he’d had no gift for gentle caresses, no interest in the passionless need to hold and absorb the essence of another person. It was foolish, perhaps, to miss what you had never had.

She was lonely, that was it. The night stretched empty and still and dreary ahead of her. There was nothing on television she wanted to watch, and she had read everything of interest on her bookshelves. She wasn’t sleepy, wasn’t even tired.

She couldn’t stop thinking of Alec Stanton. The way he looked at her, the way his smile started at one corner of his mouth and spread across his lips in slow glory. The deep set of his eyes under his brows, and the planes of his face that swept down from the high ridges of his cheekbones, giving him the predatory look of some ancient warrior. The easy way he moved, his deceptive strength. The gleam of his skin with its gilding of perspiration, the rippling glide of the dragon on his upper chest as his pectoral muscles contracted and relaxed.

How stupid, to indulge in sophomoric mooning over a hired hand, a young hired hand. It was even more stupid to allow herself the twinges of such a ridiculous attraction. If she could just be objective about it, she might laugh at the trick her mind had played on her, getting her worked up over such an unsuitable partner, like a canary eyeing the iridescent magnificence of a pheasant.

It was only hormones run amok, that was all. Nothing would come of it. Alec Stanton would do his job, then he would be gone and everything would be the same again. Everything, except she would have a new rose garden.

She would have to be satisfied with that.

It had been a mistake to leave her house, perhaps. There was more than one kind of safety, more than one kind of danger. Still, if she stayed inside now until after Alec had finished her garden, then she couldn’t get hurt.

Could she?

3

Laurel Bancroft was keeping an eye on him from the windows; Alec knew this because he had caught her at it.

He didn’t like it, didn’t appreciate being made to feel like a criminal she needed to stay away from at all costs. Or worse, that maybe he wasn’t good enough to associate with her. It had been going on for three days. He’d about had a bellyful of it.

He didn’t care if she was a widow, didn’t give a rat’s behind if she’d actually killed her husband and had good reason to shut herself away. It didn’t even matter that she didn’t see another soul beside Maisie. He wanted her out of that house. He wanted her to talk to him.

The anger that simmered inside him while he dug and chopped and ripped weeds from the ground was strange, in a way. What people thought and how they acted toward him had ceased to bother him years ago. But Laurel Bancroft had opened old wounds. She’d made him as self-conscious as a teenager again. She’d made him care, which was something else he held against her.

What it was about her, he didn’t know. It wasn’t just that she was an attractive woman, because there were jillions of those in California, and he had known his share. Nor was it, as his brother sometimes claimed, that he had a weakness for problem females. He might feel the need to lend a hand to those who seemed to be struggling, but that had nothing to do with the woman who owned Ivywild.

There she was again, behind the draperies that covered the window on the end of the house. She was standing well back and barely shifting the drape, but he had learned to watch for the shadowy movement.

That did it.

He dropped the shovel he was wielding, then stripped off his gloves and crammed them into his back pocket. He was not going to be spied on any longer. Either she was coming out or he was going in.

Maisie answered his knock. Her gray brows climbed toward her hairline as she saw the grim look on his face. Wiping her damp hands on her apron, she asked, “Something the matter?”

Alec gave a short nod. “I’d like to talk to Mrs. Bancroft a minute.”

“She’s busy,” the older woman answered, not budging an inch. “What do you need?”

“Answers,” he said. “Could you get her for me?”

Maisie considered him, her faded gaze holding a hint of acknowledgment of the human capacity for dealing misery. Finally, she nodded. “Wait here a minute.”

Alec put his hands on his hipbones as he watched the housekeeper move off into the house. Wait here, she’d said. Like a good boy. Or the hired help. His lips tightened.

After a few seconds, he heard the murmur of voices, then a silence followed by the returning shuffle of the house slippers Maisie wore. She spoke while still some distance down the hall.

“She says find out what you want.”

“I want,” he replied with stringent softness, “to talk to her.”

“Well, she don’t want to talk to you, so don’t push it.”

“What if I do? You going to stop me? Or will you just tell Grannie Callie on me?” He stepped forward into the long hallway.

“You’ll get yourself fired,” Maisie warned, even as she backed up a few steps.

“Fine. I’ll be fired.”

“I thought you wanted this job.”

“Where is she?” He strode deeper into the house while Maisie turned and trotted along behind him.

“In her bedroom,” the older woman answered a bit breathlessly. “You can’t go in there.”

“I think maybe I can,” he said, heading for the door Maisie had glanced at as she spoke.

“It’s on your own head, then.”

The warning in the housekeeper’s voice as she came to a halt was fretted with something that might have been grudging approval. He didn’t stay to analyze it, but turned the knob of the bedroom door and pushed inside.

The widow Bancroft was sitting on a chaise longue with pillows propped behind her back, her feet curled to one side and a book in her hands. Her gaze widened and a tint of soft rose crept into her face as she stared at him. Her lips parted as if she had drawn a quick breath and forgotten to release it.

The bedroom was like her, Alec thought—a medley of cream, blue and coral-pink; of substantial Victorian furniture and fragile, sensuous fabrics. It was a retreat and he had breached it. More than that, he had caught her unawares, before she could raise her defenses. She was barefoot and almost certainly braless under an oversize and much-washed T-shirt worn with a pair of white shorts. Her hair spilled over her left shoulder, shimmering with the beat of her heart, and she wore not the first smidgen of makeup to obscure her clear skin or the soft coral of her lips. She was the most enticing sight he had ever come across in his life.

In the flicker of an eyelid, she recovered her outward aplomb. Setting her book aside, she uncurled from the chaise and got to her feet. As she spoke, her voice was edgy. “What is it? Do you have a problem?”

“You might say so. I want to know why you’re afraid of me.” He hadn’t meant it to come out just like that, but he let it stand anyway.

“I’m not,” she said in immediate denial.

“You could have fooled me. Unless you have some other reason for hiding in here?”

She stared at him an instant too long before she spoke. “Who said I was hiding? Just because I don’t feel the need to oversee everything you do—”

“You’re letting me make this garden on my own, and you know it. When I get through, it won’t be yours but mine.”

She shrugged briefly. “So I’ll make it mine when you’re gone.”

“There’s no need. I can make sure that it reflects what you want right now. You won’t have to lift a finger except to point. You can tell me what you want moved and what stays as is, what you want pruned to size and what you prefer to be left natural. I’ve gotten rid of the briers and vines and everything else that obviously doesn’t belong, but now it’s decision time.”

“You decide, then,” she said through compressed lips. “You seem to know more about it than I do, anyway.”

“I don’t know what you like or what you want.” The words were simple and he meant them, but the emphasis he put on them in his own mind turned his ears hot.

“Do whatever you like!”

He stared at her, then gave himself a mental shake. She was talking about flowers and shrubs, that was all. “Suppose I clear off everything,” he said, “take it down to the bare…ground.”

“You can’t!”

“I could,” he growled with absolute conviction. “Nothing easier.”

“But there are camellias out there over eighty years old, and one big sweet olive that—” She stopped, her eyes narrowing. “But you know that.”

“I know what’s there,” he said. “I just don’t know what you care about.”

“I can tell you—”

“Show me.” He cut across what she had intended to say without compunction.

Her lips firmed. “I don’t think—”

“Unless it’s me,” he said softly. “Since you’re not afraid, then you must not like the company.”

Surprise and dismay flashed in the rich blue of her eyes. “That isn’t it at all.”

“Then what’s the problem?”

“Nothing!”

“I don’t think so.”

Her lashes flickered. “At least it’s nothing to do with you, nothing to you. I can’t imagine why you’re so concerned.”

“Call me perverse. I like to know where I stand.”

“Where you don’t belong, actually. In my bedroom.” She flashed him a look of irritation before she turned away again.

“Level with me and I’m gone,” he stated with precision.

Her lips tightened, and she crossed her arms over her chest as she sighed. “It’s not you, all right? If you must know, it’s me. I don’t deal well with people.”

“That right?” he said with a raised brow. “You don’t have to deal with me, just talk to me. I’m not complicated and I don’t bite, but I hate being ignored.”

“I’m not ignoring you!”

“Maybe you just have no use for me, then.”

“That isn’t it at all. I don’t know what to say!”

His smile was slow but sure as he turned to the door and stood holding it open, waiting for her. “Then there’s no excuse left, since I can talk for both of us, and I don’t mind your company.”

The look she gave him was fulminating yet resigned. He had her and she knew it. She was not the kind of woman who could be cruel just to protect herself, no matter the provocation. He had suspected it, even counted on it. Which didn’t say much for him as a person, but it said even less for all the other idiots stupid enough to think she could commit murder. He watched her closely as she pushed her feet into her sandals, which sat beside the chaise, then moved ahead of him down the dim hallway.

Yeah, he had her number. He had Laurel Bancroft out of her bedroom, out of her house again. Now where was he going from here?

It was a good question—one he pondered often during the next week. He might be guilty of arrogance, thinking he knew what was best for her, but he didn’t intend to let that stop him. He was nothing if not high-handed.

At least he’d managed to coax her into the garden every morning. It had taken a lot of thought and energy, not to mention dozens of asinine questions that he could have answered himself without half trying. But on the sixth day, just yesterday, he’d kept her outside long enough to get her straight little nose pink from the sun, and dirt under the nails of her long, aristocratic fingers. As his reward, she had come out of the house this morning with her gloves in her hands and a straw hat on her head.

Working beside her was both a pleasure and a royal pain. She wanted to save everything recognizable, which was going to make her garden one unholy jumble. Not that he cared. Or had any right to complain.

She also had a reverence for living things that caused her to jump in and save every turtle, frog, lizard or even snake that came anywhere near the ax or shovel he might be wielding. This morning, she had spent an hour chasing a half-grown rabbit up and down the garden to be sure it found its way outside the fence.

As compensation for his tried patience, he could stand downwind from her while she worked and catch the incredible scent of roses and jasmine and warm female that drifted from her skin. He got to take his orders directly from her, which she always couched as courteous requests. He was permitted to admire the view when she bent over in close-fitting cutoff jeans to plait dying bulb foliage or to turn over a few shovelfuls of soil. He got to talk to her whenever he pleased. And sometimes, when he least expected it, he was rewarded for some quip or comment by her rare smile.

She was the kind of woman he might have laid down his life for in another place and time. As it was, he meant to drag her out of her self-imposed exile and see to it that she began to live again. He wasn’t quite sure why he was so bent on it except that he maybe needed something to distract himself, occupy his mind. Or maybe he just hated waste.

Yes, and maybe he was an idiot to think it was that simple. Denial had never been one of his problems before.

They were eating their lunch on the veranda. He was having trouble choking down Maisie’s homemade hamburger, although it was fine eating. His throat kept closing when he turned his head to look at Laurel sitting so naturally beside him. She was hot and tired, and her T-shirt was damp with perspiration so it clung in all the right places. Her hair was coming loose from the long braid down her back, and a piece of trash was caught on her gold-tipped lashes. He thought he had never seen anything so gorgeous in his life.

“Hold still,” he said, reaching out to touch her cheek, gently closing her eyelid with his thumb before sliding the offending bit of dried leaf from her lashes with two fingers.

She blinked experimentally as he took it away, then grinned at him. “Thanks.”

Incredible, how a single word could make him feel ten feet tall. Ready to leap tall buildings. Save the world. Or do lascivious-type things on the table between them that would get him booted off the property before he could turn around.

She was watching him, her gaze faintly inquiring. He suspected his face might be flushed, considering how cool the breeze felt that wandered down the long length of the veranda. Blowing the piece of trash from his fingers, he picked up his water glass and drank deeply.

“You don’t eat much, do you?” she said in tones of mild censure. “At least, not compared to how hard you work.”

“I eat enough.” The words were short. The last thing he wanted from her was motherly concern.

She frowned a little. “I only wondered if it was on purpose, some kind of California health-food thing.”

“I guess you could call it that,” he allowed finally. “The old man I used to work with thought overeating caused all sorts of problems. Fat rats die young, he used to say. He was Chinese, laughed at the American diet while he stirred up ungodly mixtures of rice and vegetables. But he was eighty-six and going strong last time I saw him.”

“You did yard work with him?”

Alec gave a quick nod, pleased that she had remembered something of what he’d told her that first night. “Mr. Wu was a gardener. He taught me what I know about plants, and a great deal more, besides.”

Her smile was whimsical. “The wisdom of the venerable ancients?”

“You’ve been watching too many old Charlie Chan movies,” he answered with a grin. “Mr. Wu was big on Zen meditation and martial arts, but I never heard him quote Confucius.”

“Martial arts? Did he teach you that, too?”

He shrugged. “Only as a form of exercise—something else Mr. Wu was big on.”

“I’d have thought gardening would give you more than enough of that.” The words were dry as she flexed her neck muscles.

“That was my idea, too,” he replied with a faint laugh of remembrance. His gaze skimmed the softness of her breasts that were lifted into prominence as she turned her head and arched her back to relieve strain. “Mr. Wu had a way of changing a person’s mind.”

“You miss California, I expect. I mean, it must seem so different here.”

“I did miss it,” he replied with a slow shake of his head as he watched her. “But not anymore.”

She avoided eye contact. Relaxing, she used a fingertip to pick up a sesame seed that had fallen from her hamburger bun. “You’ll be going back, though, I guess?”

Would he? He had certainly thought so, once. Now he wasn’t so sure. With his brain feeling tight in his skull as he watched her place the sesame seed on the pink surface of her tongue, he said, “Not anytime soon.”

“Because your brother isn’t well enough? Or is it that he just doesn’t want to go?”

She was avoiding the issue of what he himself wanted, which seemed to indicate that she understood him a little better than he had figured. Although that might be wishful thinking on his part. After a moment, he said, “Gregory’s happy here, or happy enough. I’m not sure he’ll ever…leave.”

“That’s good, then. There must be something about it he likes.”

He gave her a straight look. “Yes, but that’s not what I was getting at.”

“Oh.” Her head came up. “You don’t mean…”

He gave a slow nod as he turned his head to squint at a blue jay just landing on a fence picket. Voice low, he said, “He isn’t going to make it.”

In the sudden quiet, the sound of a jay’s call was loud. After a moment, she said softly, “He knows?”

Alec nodded, since he didn’t quite trust himself to speak.

“How old…”

“Thirty-five in October, four years older than I am.” He was laying the age thing on the line between them. The way she had hesitated over the question made him think it might be what she wanted.

“Does he—That is, is he…all right about it?”

“No,” Alec said deliberately, “I don’t think you can say that.” Far from it, in fact. Gregory wasn’t taking it well at all, and who could blame him?

“He’s lucky to have you with him.”

It was the last thing he expected her to say—so unexpected that he laughed. “I’m not sure he would agree.”

“Maisie says your grandmother told her that you’re up with him all hours of the night.”

“Somebody has to check on him, give him his medication. Grannie fusses over him during the day, but she needs her rest.” He was surprised Laurel had spoken to Maisie about him. His brow quirked into an arch as he wondered why.

She colored slightly under his regard. “I saw you taking a nap after lunch that first day. Maisie told me you probably needed it, and why. You haven’t done it again, so I just wanted to say that I don’t mind, if you…feel the need.”

The need he felt had little to do with sleeping, though a great deal to do with lying down. Or not. “I appreciate the thought,” he said carefully, “but I’ve been managing a catnap in the evening while Grannie Callie cooks supper. I’ll get by.”

“It’s up to you.” She lifted one shoulder.

“You suggesting I’m too out of shape to do without it?” he asked in a weak effort to lighten the mood, change the subject.

Her gaze skated over his chest where he had left his shirt unbuttoned for coolness. Her mouth twisted in a wry smile. “Hardly.”

He held his lips clamped shut—it was the only way he could keep from grinning. He hadn’t been fishing for compliments, but he wasn’t immune to them, either.

He pushed his plate aside and leaned back in his chair. His wandering attention was caught by the scaling paint along the edge of the porch, and he grasped at the subject like a lifeline.

“When was the last time this house was painted?”

She shrugged. “Six years, seven maybe. I know it needs it, but…”

“As I said before, it would be a shame to let it go too far. It’s such a grand old place.”

“I know,” she said unhappily. “It’s just that it’s such a hassle.”

“I also told you I could do it.”

“You’d be here forever.”

Exactly, he thought. Instead he said, “Not quite. It’s amazing how fast you can cover ground with a few cans of paint and an air compressor.”

“Spray it, you mean?”

He lifted a brow. “It’s not a new concept.”

“No, but Howard always did it the hard way, with a brush.”

“Your husband, right?”

She nodded, her gaze on her plate. She put what was left of her hamburger down as if she were no longer hungry. Alec thought she looked a little pale. Remembering what Maisie had told him, he couldn’t blame her too much. “It isn’t your fault he died,” he said, his voice gravelly. “Don’t let it get to you.”

“You don’t know anything about it.” Her eyes flashed blue fire as she looked at him.

“Nothing except what I’ve been told. But even I have sense enough to know a woman who won’t hurt a turtle would never kill a man.” There it was, out in the open. He waited for her to tell him to get lost.

She looked away, swallowed hard. “One thing doesn’t necessarily cancel out the other.”

“You saying you really did run him down?”

“I might have.” Her face was flushed and a groove appeared between her brows.

“Sure. Pull the other one.” He caught himself waiting for the blowup, the show of temper in defense of her innocence. Where was it?

“Maybe I saw him coming up behind me before I backed out of the garage. Maybe I could have slammed on the brakes—but I didn’t.”

She was dead serious. Incredible as it seemed, she really believed she might have killed her husband on purpose. “Right, and maybe you figured he was bright enough not to walk behind a moving vehicle. Hell, anybody would.”

“But not everybody.”

“Forget them. Get on with your life.”

“That’s easy to say, but I can’t—” She stopped, took a deep breath as she lifted both hands to her face, wiping them down it as if she were smoothing away the remnants of horror. “Never mind. I don’t know how we got onto this, anyway. I—We were talking about painting. If you really want to fool with it, you can get what you need at the hardware store in town and charge it to me.”

“I could, or we might run into town now and you can pick out the paint colors.” The words were deliberate. He waited for the answer with more than casual interest.

“Oh, I don’t think that’s necessary. White will do.”

“With green shutters, I guess.” His tone was sarcastic, a measure of his disappointment.

“What’s wrong with that? It’s traditional, the way it’s always been.”

“It’s boring.”

“I guess you would like to fancy it up like some San Francisco Painted Lady?”

Her annoyance was more like it—it made her sound feisty and full of life. She was right about his taste, too. In self-defense, he said, “The Victorians liked things colorful.”

“Not around here, they didn’t. Whitewash was all anybody could afford after the Civil War, you know. Later on, everyone figured that if it was good enough for their grandparents, it was good enough for them. And it’s also good enough for me.”

“Well, heaven forbid we should go against tradition. Do you want antique white or bright white?”

“Antique.”

“I should have known.”

She was silent for a moment, staring at him. Then she got to her feet. “Fine. If that’s settled, I think it’s time we got back to work.”

It served him right.

The afternoon went quickly, at least for Laurel. One moment the sun was high; the next time she looked up it was spreading long blue shadows along the ground. She was fighting with a honeysuckle vine that had snaked its way through a baby’s-breath spirea. She had decided the only way to get rid of it was to cut both plants down to the ground when she heard a faint noise directly behind her. She swung with the hedge clippers wide open in her hands.

Alec sidestepped, lashed out with one hand. The next instant, the clippers were on the ground and her wrists were numb inside her gloves. She caught her left hand in her right, holding it as she stared at him.

He cursed softly as he stepped closer to take her wrists, then stripped off her gloves, which he dropped to the ground. Turning her hands with the palms up, he moved the bones, watching her face for signs of pain. Some of the tightness went out of his features as he saw no evidence of injury. Voice low, he said, “I didn’t mean to hurt you. It was just a reflex action.”

“I know,” she replied, controlling a shiver at the feel of his warm, suntanned hands on hers. “You didn’t hurt me. I was only surprised.”

He flicked her a quick, assessing look. “Yeah, well, so was I. I didn’t know you were armed and dangerous.”

She could make something out of that, or leave it alone. She chose to bypass it. “You wanted something?”

His grasp on her arms tightened before he let her go with an abrupt, openhanded gesture. “As a matter of fact, yes. I was going to ask if you’ll show me where the headwaters of your creek are located. I’d like to know what kind of floodplain drains into it from north of here.”

“You have a reason, I suppose?” Realizing she was still rubbing her wrist where the feeling was returning, she made an effort to stop.

His eyes were jet-black and his smile a little forced as he inclined his head. “I was thinking of diverting water from the creek for your fountain.”

“But why?” She gave him a quick frown. “They have those kits that recirculate the water. Wouldn’t that work?”

“You have to keep adding more water, plus the fountain goes stagnant after a while.” He summoned a grin. “Besides, I have a passion for water projects, and what’s the point in being an engineer if you’re going to take the easy way out?”

“I don’t think you want to go tromping through the woods to follow the creek. It’s nothing but a thicket back in there, and the snakes are already crawling.”

“You mean you don’t want to do it, I think,” he said. “Doesn’t matter. You point me down the right roads, and I can get enough of an idea from the back of my bike.”

“If you mean you want me to lead you in my car—”

The quick shake of his head cut her off. “What I had in mind was you riding with me.”

“I don’t think so!” She hovered between amazement, doubt and anger, and was uncertain which was uppermost in her mind.

“Why? Afraid I’ll overturn you?”

“No, but—”

“There’re no buts about it. Either you trust me or you don’t. What’s the big deal?”

“You don’t understand,” she said a little desperately.

He didn’t budge an inch. “So make me.”

“I don’t like motorcycles.” She glanced away, past his shoulder, as she spoke.

“You don’t have to like them. Just ride on one.”

Her lips tightened. “This is ridiculous. I don’t have to give you a reason. I’m just not going.”

“You’re chicken,” he said softly.

She snapped her gaze back to his. “You have no right to say such a thing. You don’t know what it’s like when I leave here. You just don’t know!”

“What makes you so sure? You’re not the only one with problems,” he said with a swift gesture of one hand. “At least I know one thing, which is that you have some kind of phobia about your Ivywild. If you don’t get out of it, you’re going to wind up locked inside with no way to leave. Ever.”

She bit the side of her lip. In a voice almost too low to hear, she asked, “Would that be so bad?”

“It would be criminal,” he answered without hesitation. “You have too much living left in you. Will you let it all slip away? Will you let fear dictate what you can and can’t do?”

It was a novel thought. She wasn’t sure she had any life—or courage—left, not that it made any difference. “Look,” she began.

“No, you look,” he countered, setting his fists on his hipbones. “It’s just a little bike ride. All you have to do is hold on. I won’t go fast, I won’t overturn you, and you can choose the route. What more do you want?”

“To be left alone?” she said sweetly.

“Not a chance,” he replied with a grim smile. “Not if you want that fountain.”

She stared at him, wondering if she had imagined the threat behind his words. Could he really mean that he wouldn’t tackle the fountain project if she didn’t help him with this part of it? It was just possible he could be that stubborn, that determined to have his way.

She didn’t want to put it to the test, and that was both irritating and depressing. “Oh, all right,” she told him, bending to snatch up her gloves he had dropped. “When do you want to go?”

“Now?” he said promptly.

He obviously thought she would back out if they waited. It was possible he was right, although the last thing she would do was admit it. “Let me tell Maisie, then.”

“I already told her,” he said and had the nerve to grin. Turning, he walked away toward where his Harley stood in the driveway.

She watched him go; watched the easy, confident swing of his long legs, the way his jeans clung to the tight, lean lines of his backside, the natural way he moved his arms as if he were comfortable with his body, comfortable in it. He expected her to follow, was supremely certain she would.

Of all the conceited, know-it-all, macho schemers she had ever seen, he took the prize. She would be damned if she would trot along behind him like some blushing Indian maiden, all hot and bothered because he wanted her company.

He turned, his smile warm, almost caressing, a little challenging as he held out his hand. “Coming?”

She went. She didn’t know why, but she did. It was better than being called chicken.

Alec didn’t give Laurel a chance to balk, but led her straight to the bike. He swung his leg over it, then held it steady with his feet on the ground either side while he helped her climb on behind. As she settled in place, he put her hand at his waist as a suggestion. She took it away the minute he released it, and he had to duck his head to hide his disappointment.

“It’s bigger than I thought,” she said, her voice a little breathless.

“You’ve never done this before?” he asked, grinning a little to himself at the private double entendre.

“Never.”

“First time for everything. Ready to get it on—the road?”

“Just do it and stop talking about it,” she said through her teeth.

He flung her a quick glance over his shoulder, wondering if she could possibly tell what was going on in his head. But no, her face was tight and she certainly wasn’t laughing. He turned the key, let the bike roar, then put it in gear.

She was holding on to the seat, but it wasn’t enough to keep her steady for his fast takeoff. With a small yelp, she grabbed for his waist, wrapping her arms around him and meshing her fingers over his solar plexus. He could feel her breasts pressed to his backbone—a lovely, warm softness. Her cheek fit between his shoulder blades. Perfect, he thought, a grin tugging at the corner of his mouth. Just perfect.

He settled back a little and decreased his speed. His passenger would like it better, no doubt. Besides, it would make for a longer ride. After a moment, he turned his head to yell, “Am I going too fast for you?”

“No, it’s fine,” she replied above the engine noise, but she didn’t sound too sure.

Still, he was good, the soul of restraint. He spun along the blacktop roads, took the turn onto the dirt-and-gravel track she indicated without a murmur or hesitation. He didn’t show off, held the bike dead straight. The only time he stopped was to look at the creek where it passed through culverts or under bridges in its winding passage toward Ivywild.

It was a decent-size stream, fed along its route by a number of springs, which kept the water fresh and clean. Several dry washes fed into it, which, he guessed, must run fairly high during spring and winter rains. It also carried the runoff from a series of low ridges that twisted and turned for quite a few miles. Dams had been built along its course for a pond or two, but they hadn’t slowed it down a great deal.

The creek would be fine for his purpose; he saw that much in short order. Tapping it for a fountain should not cause a problem with either landowners or environmentalists. And it certainly wasn’t as if Louisiana had any shortage of water. If the state could only find some way to pump it out west, it would be rich.

“I’ve seen enough,” he said as they idled beside a rusting iron culvert. “What shall we do now?”

“Go home,” she replied, the words definite.

He gave a slow nod. “Right. But first, I’d like to see where this road comes out.”

She said something in protest, he thought, but just then he gunned the bike into motion so he didn’t quite catch it.

It was a dirt road, a hard-beaten, sandy track that meandered through the woods. There were a few big old trees standing on nearly every rise, as if it had once been lined with houses. All this land had been farms back before the turn of the century, with pastures and fields stretching over the rolling hills as far as the eye could see. That was according to Grannie Callie, anyway. She could still remember a lot of the family names, could tell him who gave up and moved to town to work in the mill, who took off to Texas, who went away to the big war, World War II, and never came back. It was strange to think about all those people living and working, having children and dying here, and leaving nothing behind except the trees that had sheltered their lives.

“Turn around!” Laurel yelled into his ear. “We’ve got to go back!”

He nodded his understanding, but didn’t do it. Zipping around the tight curves of the unimproved road, passing from bright sun to dark tree shadow and into the sun again, he felt free and happy and lucky to be alive. He wouldn’t mind riding on forever. He couldn’t think when was the last time he had enjoyed anything so much as roaring along this back road with Laurel Bancroft clinging to him, bouncing against him as they hit the ruts, tethered together now and then by a long strand of her hair that wrapped around his arm like a fine, silken rope.

“Stop!” she shouted, shaking him so hard with her locked arms that the bike swerved. “This road cuts through to the main highway. We’re getting too close to town!”