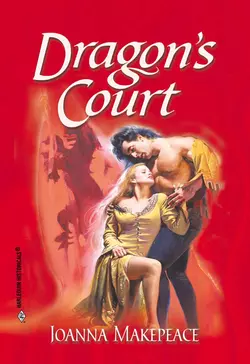

Dragon′s Court

Joanna Makepeace

The man she loved, but couldn't marryAfter watching her father pay a steep price for his allegiance to the deposed Richard III, Anne Jarvis vowed to find a peaceful life with a simple man who had no political leanings. Undercover agent for the crown Dickon Allard didn't fit that bill, though as he escorted her to London, Anne couldn't imagine how bleak her world would be without him.She thought that her time at Court as lady-in-waiting to Queen Elizabeth would make her forget him. But as political mayhem ensued, Anne prepared herself for the turmoil she had to face…and the battle she would wage to protect her love!

She closed her eyes and pictured him.

Dickon was a man to rely on, a man many women must have known—and loved—

She shied from the thought. Such a man was not made to marry. Any woman trusting enough to love him could soon find her heart broken when she became a widow. No, whatever her father wished, she would not allow herself to become fond of Richard Allard. She must dismiss all tender thoughts of him from her mind and concentrate on acquitting herself well at Court and—possibly—finding herself a wealthy and steady suitor who was as desirous of achieving success and a comfortable existence as she was herself.

Dragon’s Court

Joanna Makepeace

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

JOANNA MAKEPEACE

taught as head of English in a comprehensive school before leaving full-time to write. She lives in Leicester with her mother and a Jack Russell terrier called Jeff, and has written over thirty books under different pseudonyms. She loves the old romantic historical films, which she finds more exciting and relaxing than the newer ones.

Contents

Chapter One (#uaad0b043-423b-52b1-81c4-c0a07a88276b)

Chapter Two (#u8be04ab8-b682-5860-a2e9-daf35ae030d5)

Chapter Three (#ue16564ab-0651-5366-bef8-68ecf071dc06)

Chapter Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One

1499

Anne would have managed the rescue of the kitten without any need for assistance had not the hem of her gown caught on a branch of the apple tree she was climbing and caused her to lose balance and, for a dizzying moment, hang almost head down in space. She caught desperately at a lower branch and managed to pull herself to safety again and stayed for a while, winded, clutching at the rough bark of the tree’s stout trunk for dear life.

She regained her wits and her courage again eventually and saw she was safely ensconced on a stalwart branch about halfway up. The trouble was that her hem was still caught and, as she looked down, annoyed, and began to tug at it viciously, she discovered that her efforts were decidedly endangering the steadiness of her refuge.

She slithered until she was half-crouched, half-seated, and surveyed the terrain around her. The kitten remained on the topmost branch where it had retreated from the threat of Ned’s dog. It mewed pitifully and Anne shook her head at it regretfully.

“I’m sorry, Kitty,” she murmured, “but, for the present, you’ll either have to manage to descend by yourself or stay where you are.”

Frowning, she peered round to discover that Ned and the dog were no where in sight. Her thirteen-year-old brother had declared his intention of fishing in the Nene and the hound pup had given up the chase, abandoned the kitten and run off in the direction of his young master’s whistle to heel.

Fortunately this part of the manor orchard was close to the path leading up to the house. Someone, Anne thought grimly, would be sure to come along soon and it had never been her way throughout her sixteen years of life to give way to uncontrolled panic. Still, her position here was not only precarious but uncomfortable.

The weather was fine and bright this September morning of 1499 but it was growing much colder than it had been earlier this morning and she shivered and blew on her fingers. Her back was securely placed against the supporting trunk but she dared not wriggle too hard lest the branch she was actually seated on gave way. She was, she judged, probably more than six feet from the ground.

Only yesterday her lady mother had organised the household servants into the picking of the orchard fruit and most of them even now were engaged in sorting and laying the apples and pears out carefully in attic and barn to keep throughout the autumn and early winter months ahead.

Anne was warmly wrapped in hooded cloak and thick stockings and petticoats beneath her warm russet gown but the chill wind was beginning to permeate the frieze cloth of her cloak and she wished a groom or Ned, returning, would come soon now and release her from her uncomfortable perch. She prayed, though, it would not be her father.

Recently she had displeased him on more than one or two occasions and her mother had warned her many times about hoydenish behaviour. Scrambling up the apple tree would be considered so, she thought, and gave a heavy sigh.

If she came under her father’s disapproving eye again it could mean a sore back and she would have only herself to blame. She had been irritable and difficult for weeks now and Ned had castigated her scathingly for causing her father’s anger to fall not only on her head but on his as well. It had been to get out of the way of the disagreeable atmosphere of the house that he had taken himself off to the river.

She bit her lip thoughtfully. Her discontent had made itself felt only since Dionysia Gresham, their neighbour’s daughter and Anne’s closest friend, had been conducted to her place in the Countess of Chester’s household where she would wait upon that lady and, in time, be found a suitable husband.

That should not be too long, Anne mused, for Dionysia was pretty enough and gentle and good tempered to boot. Anne missed her friend and envied her her good fortune, and bitterly resented the fact that her own father had made it very plain that such a life amongst the great ones of the realm could never be hers.

A sound beneath her caused her to break off her reverie and glance cautiously downwards.

A man was peering up at her, shading his eyes from the glitter of the low September sun. She could not move sufficiently to have a clear view of his face but she could see he was wearing a brown hooded frieze cloak over a leather jack, stout brown woollen hose and that his leathern boots were mired with dust. His hood had fallen back and she saw he had a thick crop of untamed brown hair.

“Mistress Eve,” he called gaily, “are you willing to offer me the apple of temptation?”

He had been carrying a canvas pack of some sort which he had deposited at the foot of the tree as he stood, hands on hips, regarding her. He was possibly a travelling chapman, she decided. She did not know him and if he could be persuaded to rescue her before anyone came who did, she would be at a greater advantage when explaining to her mother about the tear in her gown.

She said tartly, “You can see surely, fellow, that all the apples are picked. My hem is caught on that branch. Please free me.”

He looked round for the offending branch and made a sign.

“I see it. Stay where you are, quite still. That branch you are resting on looks somewhat too frail to hold your weight much longer. Hang on to the trunk.”

Did he think her a fool? she thought dourly. Of course she intended hanging on for grim life. Once he started to shake that lower branch it could unseat her.

She saw now, with some trepidation as he approached the tree, that he was a big man, powerfully built, and she prayed he would not use too much effort in disentangling her hem and cause the bough to shake further and dislodge her. In actual fact, he proved to be surprisingly gentle and dextrous. He was tall enough to reach up and free the hem without needing to climb and Anne was surprised when he called up to her that the material was now free.

“You should manage to climb down, mistress, unless you are scared to do so. If so, I’ll come up and fetch you.”

“Certainly not,” she snapped. “I can manage. I’ve been climbing trees all my life.”

“Indeed?” The voice sounded amused and she noted that it was not a peasant’s voice, but deep pitched and without obvious dialect. Certainly he did not come from Northamptonshire, she determined. Possibly if he were a travelling chapman he would have lost his own dialect and adopted others as he moved around from place to place.

Now that she was free to descend she would rather have done so in privacy. She peered down uncertainly as the newcomer stood slightly away from the tree trunk now, hands on hips, regarding her. There was no help for it, she must climb down under his amused gaze. She could hardly dismiss him, as she would have done had he been one of the Rushton men.

It was more difficult than she had thought, for she had stiffened during the uncomfortable moments she had spent on her precarious perch. She almost fell the last few feet. The stranger stepped immediately close and, putting his arms around her waist, drew her gently to the ground.

She stood for a moment with her back to him, leaning against the trunk, then breathlessly swung round to thank him.

“That was well done,” she said grudgingly. “You can let go of me now. I am quite safe.”

Grinning, he did as she requested and made to move back to his pack.

“I suppose you can climb well?” she demanded and he turned, eyebrows raised to regard her again.

“Tolerably well, mistress. Like you I have been climbing trees for most of my life though not, I must say, so much recently.”

She chose to ignore his pithy though oblique reference to her youth. She pointed upwards to the topmost branch.

“Can you get up and rescue the kitten?”

He shaded his eyes again then distinguished the animal shaded by the leaves now turning from green to golden brown.

“I suppose so,” he said and she noted again the tinge of amusement in his tone, “but in my experience cats usually manage to descend without help if you leave them alone. He managed to get up there by himself, he’ll come down by himself.”

She drew in a sharp breath of annoyance. “Why do you think I went up there, if not to fetch the kitten? He is very young and frightened. He ran up when my brother’s dog barked at him.”

“Ah, in that case—” He grinned and, throwing back his cloak and hood, approached the tree again and began to climb steadily.

She stepped back to watch him, a little alarmed now for his safety. He was no youth and might well not be so agile as Ned. Perhaps she should not have ordered him to climb. He seemed skilful enough, swinging easily from branch to branch after first testing to check whether each would stand his weight, which was considerable. The kitten seemed reluctant to trust him at first and retreated along the top branch, mewing pitifully.

Anne heard him utter a quick curse then he leaned closer to the frightened animal and began to murmur to it beneath his breath. After one or two moments the kitten allowed itself to be lifted up and he thrust it into the opening of his leathern jack and began to descend nimbly. Landing gracefully for so big a man, he handed the quivering bundle of black fur to her with a little bow.

“Safe and sound if still a little alarmed. Is he yours? You must keep your brother’s dog under control.”

Her tone was haughty as she replied, “He is one of our courtyard cat’s litter. Cato only wanted to play. He’s little more than a puppy himself.”

The man was looking at her appraisingly and she flushed darkly. How dared he stare so insolently? Obviously she was not looking her best for she could feel that the wind had caught tendrils of her hair and pulled them clear of her white linen cap and her gown and cloak had not been improved by close contact with the tree trunk. Impatiently she pushed back her hair and pulled her hood into place.

He had a broad, open countenance, dark skinned as one would expect of a man who had stayed long out of doors, particularly during the summer months. His forehead was high and broad and his nose beaklike, a little craggy. His most attractive features were his wide-spaced grey eyes and a full, generous mouth, surprising in that very masculine face. The chin was firm and well chiselled and bore a decided cleft. It was an interesting face, she decided, and tried to guess his age. There were little laughter lines around the eyes and deep clefts from nostrils to the corners of his mouth. He was well past his twentieth birthday, she thought, but he was not old, not even middle aged.

For his part he was in no doubt about her age. She must be sixteen now or almost so. The last time he had seen her she had been still a child, clinging to her mother’s skirts; now true womanhood was almost upon her. Like her lady mother, she was dark. The thick masses of her hair streaming below her cap well past her waist had not been braided and the autumn sun glinted on the waving tresses, touching the blue-black gloss with touches of gold.

She had her mother’s creamy complexion, too, and a lovely oval-shaped face with strongly marked but fine features and her father’s startlingly blue eyes. She stood uncertainly, holding the kitten which was wriggling and scratching in her too-tight hold, at the same time trying to clutch the billowing folds of her brown frieze cloak about her slender form.

He had expected her to be tall and slim, for both her parents, Sir Guy Jarvis and Mistress Margaret, her mother, were tall and he could see that her young breasts, despite her efforts to hold her cloak close and hide her form from him, were taut and firm, pushing against the stuff of her russet gown. They would soon be looking for a husband for her, he thought, and sighed a little, inwardly. That would be no easy task for Sir Guy, under the present prevailing circumstances.

She moved a trifle uncertainly as if she was not sure how to dismiss him.

“You have come far, sir?”

White teeth gleamed in an answering smile in that dark complexioned face. “From the north,” he said evasively.

She hesitated. “My father is Sir Guy Jarvis and my home, Rushton Manor, only a short distance from here. You have done me a service. If you come to the manor I am sure our servants can provide you with a meal. You must be hungry.”

He gave her that little odd bow in answer which was in no way servile.

“Thank you, Mistress Jarvis.”

He shouldered his bag and moved beside her down the path until they reached the gatehouse and passed into the courtyard of Rushton. The house faced them, half-timbered, the undercroft of mellow Northamptonshire stone. The kitten scratched Anne deeply and ungratefully, sprang from her arms and shot off in the direction of the stables. She gave a startled cry. Her companion turned at once to see what had caused her distress and she sucked at the wound on her hand.

“Little beast,” she remarked ruefully, as he bent to examine the hurt.

“Cat scratches can be nasty,” he warned. “You must ask your lady mother for some tansy salve.”

She nodded. His large hand was holding her slender small one very gently and she felt suddenly uncomfortable in his presence. This stranger had a way of making her aware of her own childish folly in attempting to rescue the kitten without uttering one word of disapproval—yet why should she heed a passing stranger, an inferior to boot? She was about to point out the way to the back door into the kitchen quarters and quickly rid herself of his disturbing presence when her father’s voice came from the top of the steps leading up to the hall.

“Anne, where have you been? Your mother has sent out more than one woman to find you—” He broke off abruptly, staring at the two of them across the courtyard; then, with that grace of movement Anne always associated with her handsome father, he leaped easily down the steps and covered the distance between them quickly.

“Dickon? Dickon Allard, is it really you?”

The newcomer laughed. “Indeed it is, Sir Guy. It seems a long time since I came to Rushton Manor.”

Anne watched in dawning horror as her father took the stranger’s strong brown hands into his own grasp and squeezed them affectionately, then he pulled the man close and clasped him to his heart.

“You are welcome as always, Dickon, you know that. Margaret will be delighted to see you. Come in immediately and get warm near the hall fire. We must order food for you at once. How far did you travel today?” He stepped back apace, frowning, somewhat puzzled. “Where is your horse, man?”

Again Anne heard that deep-throated chuckle. “My mare cast a shoe about a mile and a half back, so I led her to the nearest village smithy. The smith said it would be quite a long job so I thought I’d come on here and fetch her later. I was stiff in the saddle, have ridden from Leicester this morning; the walk has loosened me up.”

Anne could not meet the man’s eyes. Richard Allard, the son of her father’s friend, Sir Dominick Allard, the man whom Sir Guy Jarvis had served for years as squire—and she had treated him like a servant! Her blue eyes flashed dangerous fire. He must have known well enough who she was.

Why hadn’t he announced himself immediately and not left her to jump to so unfortunate a conclusion? How was she to know? The man had arrived on foot, plainly dressed, if not shabbily, and carrying his own valise like a pedlar his pack. Could she be blamed for treating him so condescendingly?

Her father was regarding her and she flushed under his critical scrutiny.

“I see you and my Anne have met already. I trust she made you welcome?”

Anne waited in dread for the visitor’s reply. He was facing her now, his grey eyes dancing with amusement, doubtless at her discomfiture.

“Mistress Anne greeted me very warmly, Sir Guy, and, like you, was very anxious to assure my comfort. She instantly thought how hungry I must be feeling.” He turned to his host as a servant hastened up to relieve him of his valise. “In truth, I am not hungry, just saddle sore, as I said, but I broke my fast at the village inn where I waited for the smith’s verdict about my mare. I can certainly wait until supper, but I would welcome an opportunity to bathe.”

“Of course, of course. Come first and greet Margaret. How are your parents? I trust your father’s old wound does not still trouble him?”

“He still limps, sir. I’m afraid he will carry that reminder of the final charge at Redmoor until his dying day but in himself he keeps well and my mother is blooming, as ever. To me she is the epitome of the Nut Brown Maid of the ballad. Each time I come home to Wensleydale from my travels I expect to see her changed, or, at least, some traces of grey in her hair, for my father’s temples are as grey as a badger’s these days, but she is as lovely as I remember her when I left.”

Anne was aware that both her father and Sir Dominick Allard had served in the household of the late King Richard and had fought side by side in his last fatal battle and defeat at Redmoor near the little market town of Bosworth in Leicestershire in 1485.

Sir Dominick had taken a severe wound to his thigh in the charge in which his King had met his death, a wound that still troubled him, one that had kept him from fighting in Lord Lovell’s attempt the following year at East Stoke near Newark to place the pretender Lambert Simnel on the throne. That battle had proved as ill fated as Redmoor and King Henry had triumphed again. Anne had heard it whispered about the manor that her father had taken part in it, but had managed to return home in secret without his treason being discovered.

“I’m delighted to hear they keep well and hope, one day soon, to see them both again.”

Sir Guy linked arms with Richard Allard and led the way up the steps into the manor hall, Anne trailing behind. She looked anxiously round for Ned to join them but he was still remaining out of the way near the river. Sweet Virgin, her mother would demand an account of her meeting with their visitor, especially in view of the condition of Anne’s torn gown and her green-stained cloak. What could she say, how explain her boorish behaviour?

So far Richard Allard had kept the circumstances of their encounter to himself. Would he continue to do so? She did not deserve so much consideration. Now that she thought about it, his very manner and bearing, as well as his speech and mode of address, should have established him in her mind as a man of standing. How could she have been so crass?

Her beloved father appeared almost slight and spare beside this bear of a man. Sir Guy’s fair hair, as ever, was dressed elegantly and his handsome features were alight with pure pleasure at Richard Allard’s arrival. He led him swiftly to the comfort of the blazing fire in the hall’s fine heraldically decorated fireplace and summoned a servant to bring ale and wine and take the visitor’s cloak.

“Anne, go at once to the solar and inform your mother that Dickon Allard is here. She will issue orders for the preparation of a chamber. Where is Ned? He should be here too to greet our honoured guest.”

“Fishing in the Nene,” she said promptly and, meeting Dickon Allard’s smiling eyes, made him her first quick curtsy. Then, grateful to be out of his presence for a while, she sped off to the solar to break the news to her mother. With her hand on the door knob she reflected that perhaps it would have been better had her father allowed her to remain in the hall. At least she would have heard what Richard Allard said to him.

Margaret Jarvis looked up hastily as her daughter entered. She was sewing at the dark blue velvet of a new-fashioned French hood and was alone. Her dark brows rose in interrogation as Anne swept in, her cloak billowing behind her.

“There you are. I have been looking for you. I wished to try this on you for size. Goodness, child, what have you been doing to your clothes? You know your father’s means are limited these days. You should take more care. It is bad enough that Ned tears his hose, but you should know better.”

“I’m sorry, Mother, but a kitten got caught up a tree and just would not come down. I had to climb. There was no one else nearby. He is safe now.”

The child was breathless and evidently excited. Margaret was surprised. Just lately nothing had excited Anne or pleased her. Indeed, Margaret reflected, had she behaved so badly as her daughter had done recently, her own father would have taken a switch to her. Guy had held his hand and Margaret had admired his patience with the girl. Her own had been fast running out.

The whole of the trouble lay in the fact that Dionysia Gresham had left their neighbouring manor to enter the Countess of Chester’s household and would, most likely, attend her mistress at court at Westminster. Anne sorely missed her friend’s company but there was more to it than that. Although the reasons for her own ineligibility to attend a noble household had been explained to her often enough, Anne had never really accepted them.

“We have a visitor,” Anne announced breathlessly. “Richard Allard, from Yorkshire, isn’t it?”

Like her father’s, Anne’s mother’s face expressed immediate pleasure at the news.

“Richard, here? Oh, how good it is to have him. I shall have news of Dominick and Aleyne. It is far too long since we heard from them.” She rose at once, laying aside the unfinished hood. “Your father has been informed?”

“Oh, yes. He is with him in hall. He sent me to fetch you. Father says a room must be prepared for him.”

Again Margaret Jarvis’s dark brows rose. “I did not hear a horse enter the courtyard.”

“No, he is on foot. Apparently his mare cast a shoe. Father will send a groom to fetch her from the smithy later.”

Margaret was moving unhurriedly towards the door of the solar. Anne admired her stately passage in her dark burgundy velvet gown. It suited her well, though the tight-fitting sleeve cuffs were somewhat rubbed and Lady Jarvis still affected the old style of headdress: small cap, hennin and veil.

Though Anne was aware of the latest changes in fashion through Dionysia who took careful note of all news from Court since tidings of her impending term of service in the Earl of Chester’s household, she was aware that her mother remained as lovely as her father had declared her to have been when he had wed her at Westminster, more than sixteen years ago, in the late King Richard’s time, and in his very presence.

Anne was fully aware that it was this very allegiance to the late King’s household and her father’s continued stubborn loyalty to the Plantagenet cause that had resulted in their present impecunious state here at Rushton.

Sir Guy Jarvis had been pardoned after Redmoor, for King Henry had shrewdly declared the beginning of his reign the day before the battle, thereby making all those who had fought for their King technically traitors. Anne’s father had survived the pursuit following the battle and managed to reach the comparative safety of Rushton, but the King’s officers had levied a swingeing fine from which the manor had never truly recovered financially.

The number of household servants and dependents had had to be cut to the bone and for eleven years Sir Guy was aware that his every move was watched by agents of the Tudor now living in Northamptonshire. Anne sighed resentfully as she faced the need for economy in her own dress allowance, which denied her new-fashioned garments like the ones her friend Dionysia had obtained in which to travel to her new household.

She would not have minded that so much if she had not to face the prospect of life here at Rushton, familiar and dear, but irritatingly dull. Anne had listened open-mouthed to her mother’s tales of life at Court and the intrigues and adventures that had befallen her there and wished that such a fascinating and exciting life could be hers.

The arrival of Richard Allard brought home further the need for all of them to guard their tongues and behaviour. The Allards, too, made little secret of their contempt for the Tudor’s claims and Anne wondered doubtfully what was the reason which had brought Richard here. Could it be to embroil her father into yet another secret plot against the King? She paled at the thought.

Only recently the arrest of the second pretender to the King’s claim, the man they called Perkin Warbeck, had caused fear and despondency to spread through those families who still doggedly supported the Plantagenets and Anne knew her mother constantly feared for her father’s safety.

How could she constantly live like that? Anne wondered. She could not. She wanted a settled, peaceful life, if not at Westminster, at least secure on her own small manor with her husband and children safe by her side. Yet she knew well that the neighbouring gentry would be wary of allying themselves in marriage with the disgraced Sir Guy, that her father would not find it easy to find her a husband.

She put to rights her appearance and joined her parents with their visitor in the hall to find that Ned had now come home and was seated near Richard Allard, listening intently to the tales of his recent travels. Anne experienced a momentary feeling of irritation that her brother should greet this stranger in so admiring a manner and regretted, more than ever, that she had had to appear before him in her old russet gown which had had to be pinned at the torn hem by her maid, Mary Scroggins.

Anne’s worst suspicions were confirmed as it was obvious from the line the conversation was taking that Richard Allard’s loyalties were cast in the same mould as her father’s.

Sir Guy was speaking as she entered and, at a signal from her mother, Anne seated herself on a stool by Lady Jarvis’s side.

“In Leicester did you manage to visit the Friary?”

Richard Allard took a pull at his wine cup and nodded. “Aye, I see the Tudor has not kept his word and had the promised memorial put on the tomb, but the King lies safe and snug and I paid for masses to be said for his soul.”

Anne had heard that King Richard’s body had been shamefully treated following the battle at Redmoor and had been brought back into Leicester town half-naked, across the neck of his own destrier, White Surrey, wearing a felon’s halter around his neck. His body had been exhibited for public view in the church of St Mary the Lesser, outside Leicester’s castle and finally buried by the Grey Friars within their enclosure.

On his rare visits to Leicester Anne’s father had visited the tomb, but had never once taken Anne to see it. She knew his visits there were viewed with disapproval by some of his neighbours, yet another mark against him for his commitment to the former dynasty.

King Richard III had been dead now for fourteen years. Surely, Anne thought angrily, her father and this man could allow him to rest in peace and not continue to antagonise the present occupant of the throne even in secret. If Sir Guy were to accept the situation without complaint it would be more likely that she, Anne, would be allowed to mix with her neighbours’ daughters and the prospect of a suitable marriage would be made possible.

It was all very well for Ned to talk boastfully of what amounted to treason, but he was still a boy and his life was unlikely to be blighted by his youthful opinions which, undoubtedly, would mellow with time. She glared at him as he pressed Richard Allard for more news of the world at large.

Richard Allard had clearly been recently from the realm but he was discreet and somewhat vague as to his wanderings. Anne was in little doubt that more than likely he had been at the Court of King Henry’s greatest avowed enemy, the late King’s sister, Margaret of Burgundy, at Malines.

From time to time Richard Allard’s eyes passed over her as she sat demurely and she read amusement in them. Her father had passed no comment on her recent behaviour, so she gathered that her treatment of his friend’s son had not been divulged and she sank back on her stool somewhat relieved.

Supper was served and their visitor continued to regale them with news of other men her father had known and loved in the past. Watching Sir Guy, Anne saw that his handsome face was alight with avid interest, a state she had not seen revealed in him for many a month.

Afterwards, her father announced his intention to visit the stables to check that Master Allard’s horse had been brought back to Rushton and was being bedded down comfortably. Ned rose at once, eager to accompany him.

Sir Guy smiled at his visitor. “No need for you to come, Dickon. We will see everything is done for your horse’s comfort. Make further acquaintance with my daughter.” He smiled at Anne genially and moved to the screen doors. Lady Jarvis had left earlier, murmuring that she must ensure that the sheets in Master Allard’s chamber had been aired and the warming pan brought into use. Anne nervously found herself alone with their visitor.

“Sir,” she said hesitantly, “I am grateful that you have made no reference to my boorish behaviour in the orchard. My father would have been gravely displeased.”

He shrugged lightly. “You were not to know who I was.”

“No,” she stammered awkwardly, “but—but I am enjoined to be courteous to everyone I meet.”

“Indeed? And are you?”

“Yes, no—most of the time,” she added lamely. “You caught me when—when my spirits were low.”

“You must have been vastly uncomfortable up that tree, possibly frightened.”

“Oh, not frightened.” She found herself laughing as his grey eyes twinkled and she realised he was teasing her gently. “Well, I was just beginning to panic, just a little, and Ned seemed completely out of range of my calling, but—but it was not that.”

“Oh? You are not happy here at Rushton?”

“Yes, of course I am—but sometimes I long to go further afield as you have done.”

“From necessity, Mistress Anne, I assure you. Often I would prefer to be living in tolerable comfort with my family in Wensleydale.”

“Then why do you not remain there?” she said impulsively and immediately blushed with shame as she realised her question was impertinent in the extreme.

He looked grave for a moment and said quietly, “Duty calls me from home more than I would wish. My father’s old injuries necessitate him remaining at home and we have duties—elsewhere.”

“And you are on your way south?” she enquired diffidently.

“Yes, I journey to London on business but I hope to return home for Christmas. My younger sister, Anne, is expecting her second child then and I am anxious to attend the christening.”

“Your sister is wed to a local gentleman?”

“Yes, she is very happily wed to Sir Thomas Squire whose manor is near Bolton. She already has a healthy brat of a five-year-old-son, Frank, whom we all love dearly. I am hoping she will bear a daughter this time, for me to cosset.”

Anne was silent for a moment, considering. How fortunate Anne Allard had been to marry a man who loved her and to bear his children, but how could she endure the dull life in the wilds of Yorkshire?

“Is—is Sir Thomas of—your persuasion?” she enquired cautiously.

Richard Allard’s grey eyes opened very wide and, again, his expression grew grave.

“Yes,” he replied, a trifle shortly, “as most gentlemen of Yorkshire are, but he is circumspect and does not pursue his views too actively.”

She knew the unspoken rider to that was “as I and my father and your father do.”

Her lips trembled as a little tingle of fear ran through her.

When her mother returned and said meaningfully that it was getting late and the ladies should retire Anne was almost relieved to obey. She rose and curtsied and met her father on his way in through the screen doors as she left in her mother’s wake.

Sir Guy poured more wine for his guest when they were left alone together.

“How long can you stay this time, Dickon?”

“No more than two days then I must be on my way again.”

“To London?” The finely arched brows rose interrogatively.

Richard Allard nodded and drained his wine cup. “Yes. You will have heard that Warbeck was rearrested in June after some attempt to escape and now is confined in the Tower—with the Earl of Warwick?”

Sir Guy drew his chair closer. His son, Ned, had already been dispatched to bed and he had given his servants instructions not to disturb him further tonight. Even so he was careful to keep his voice low when talking of such inherently treasonable matters with his friend’s son.

“You think he may be too close?”

Richard Allard sighed. Sir Guy had again refilled his wine cup and he swirled it slowly, moodily, watching the firelight glow in the bloodlike depths.

“It would be preferable, for both their sakes, if they were kept strictly apart.”

“Surely Henry will be aware of that and take steps to see that that is done?”

“Yet, if there is danger in such contact with Warbeck, that might prove profitable for Henry.”

Sir Guy sat bolt upright. “You mean he would have an excuse to rid himself of the Earl? Over the years he must have longed to do so. The late King’s nephew has so clear a claim to the throne that it must be a constant thorn to Henry’s peace of mind.”

“Precisely.” Richard stared down at his boots and stirred his feet restlessly.

“I go to keep an eye on things, nothing more. If it proves necessary to try to extricate the Earl…” He shrugged. “I pray heaven there is no such need.”

“You are known at Court?”

“I have never attended since I served King Richard as a page before Redmoor but, like you, as my father’s son, I need to remain discreet. I intend to be back in Yorkshire at Christmas. My sister Anne will be delivered then. You know she miscarried a child two years ago and was very ill. She is now recovered and happy about the impending birth but, naturally, we are all anxious for her.”

“Your mother in particular.” Sir Guy nodded. He hesitated. “You are still unwed, Dickon?”

Richard inclined his head smilingly.

“No romantic entanglements?”

“Oh, plenty.” The young man laughed. “I have thought myself in love many times, particularly when I was young but—I have never deemed it politic to offer marriage to any woman and I am still heart whole.”

Sir Guy supped his wine. “I imagine your mother has pressed you to take a wife—for the succession if nothing else.”

“My father understands well my reasons. Like you, we find managing the desmesne is difficult under straitened circumstances. What have I to offer a maid?”

“Strength, youth, good health and you are not un-comely.”

Richard Allard laughed heartily. “I am no longer so young, sir.”

“How old are you, Dickon, now, twenty-five, -six?”

“Twenty-seven,” the other replied with a rueful shrug.

“I was almost your age when I wed my Margaret.”

“An arranged marriage?”

“We had been betrothed five years earlier but her father broke off the arrangement. He wished her to marry one of Dorset’s gentlemen but the fellow died. She was about to enter into a new betrothal when King Edward died and her father’s fortunes were altered. King Richard saw to it that I was given my bride.”

“Against her will?”

Sir Guy pursed his lips thoughtfully. “Perhaps so, at first, but afterwards we realised our love for each other. Our marriage, like your father’s, has been totally successful. Margaret has given me her complete support. Her love and loyalty have never faltered, despite our difficulties over the years since Redmoor.” He paused and then said deliberately, “At one time your father and I considered a contract between you and my Anne.”

Richard Allard turned bright grey eyes upon his host. “Aye, I know, and—and I would be very honoured, yet I am old for the lass. She must be sixteen or near-abouts.”

“In a few weeks, and mature for her age.” Sir Guy frowned. “Lately she has been restless, fretting against her exile from what she considers the hub of events. Of course, I am relieved that she is—only, I also know she will soon be ripe for the marriage bed and I am anxious to see her settled.” He shrugged. “After all, who knows what the future will bring to any of us?”

“I said I would be honoured, sir, but…”

“You do not find Anne attractive?”

The grey eyes lit up. “I find her enchanting. She has her mother’s beauty and a combination of yours and Lady Jarvis’s sprightly make-up. It is just that—my duty leads me into dubious business. Were I free to consider marriage I would request her hand.” He broke off, staring into the fire’s bright heart. “You must know, Sir Guy, how deeply our womenfolk suffer when we are engaged in dangerous work. I would not risk either the security or the happiness of Mistress Anne while I am committed elsewhere than in Wensleydale.”

Sir Guy sighed again regretfully and nodded in agreement.

He decided to change a subject which could be embarrassing for his guest. He said quietly, “You saw this Warbeck at close quarters—often?”

“Not often.” Richard Allard’s tone was wary as if he guessed at the other’s next question. “You are about to ask if I believe that his pretensions are genuine?”

“Yes.”

Richard shook his head. “I wish I could answer that squarely. I just do not know. I saw him quite close once or twice. Certainly he resembles both the late King Edward and Queen Elizabeth, his wife. That likeness is quite uncanny. Were it otherwise I would have dismissed his claims out of hand for, to be frank, sir, he does not appear to have that about his character that would make me accept him as a son of King Edward, for all my father has told me about that man, or a nephew of King Richard. He is charming, courtly, but without that steel core which was their inner strength. Of course, his life has been unfortunate and without that training which would have prepared him for intrigue and war…”

“His confession?”

Richard Allard’s grey eyes met those of his host quizzically. “If you or I had been in the hands of Henry’s officials, would we not have confessed to anything? I think we can dismiss the confession from our considerations.”

“You have met with the Duchess Margaret?”

“No. I have been in contact with Wroxeter, of course. He is her trusted man, as you know, and has been in attendance at Malines since Redmoor. He gave me no direct opinion on the man’s identity, only, naturally, that he was of use to Margaret in putting a burr beneath the Tudor’s saddle cloth. I know only that that slur on the late King’s reputation, regarding the murder of his nephews, is slanderous.

“The boys survived Redmoor, as you know only too well. Where they are now, I cannot tell. It is just as well I do not know. Were I to fall into Henry’s hands it could be disastrous to their well being if I were to be questioned on such matters. I cannot be certain I would be able to hold out against divulging the facts were I subjected to torture.”

Richard’s father had made him aware that, following King Richard’s coronation, Sir Guy Jarvis had escorted the elder of the young sons of King Edward IV north to Castle Barnard, while the younger prince, Richard, had been taken abroad, presumably to Burgundy. He did not know if Sir Guy was aware of the whereabouts of his former charge. It was clear from his question that he was as unsure as all of them were about the true identity of the latest pretender to claim King Henry’s throne.

Was the man who now lay in the Tower the very prince who had been escorted to his Aunt Margaret’s palace in Burgundy? The man had confessed that he was an imposter, the son of a merchant named Warbeck who had been carefully groomed for his role but, as he himself had said to Sir Guy, who could be sure that such a confession had not been extracted under torture or even the threat of torture? Richard was well aware that such pressures on even the bravest of men could not always be overcome.

Sir Guy appeared to have fallen into a reverie from which he drew himself up abruptly.

“It is getting late, my friend. You must be wearied. You’ve been travelling some days. I’ll escort you to your chamber.”

Richard rose willingly enough. At the door to the inner rooms of the house he stopped for a moment and looked directly at his host.

“Sir, as I have said, I do not expect my business in London to engage me for too long a time, neither do I anticipate any particular—difficulties. When I complete the handling of my father’s affairs and—any other problem I might encounter, I would be grateful if I could break my return journey here at Rushton.”

“You know you will be very welcome, Richard.”

The other hesitated for only a moment then he said deliberately, “Should all go well, I will then request the hand of your daughter, Anne, in marriage, sir.”

Sir Guy gave a faint hiss of breath and his blue eyes shone with an excited gleam.

“That request will be received favourably, you can be assured of that, Dickon. However…” He paused and his lips curved a trifle sardonically “…though you will encounter no opposition from me, you may do so from the lady herself.”

A crease appeared between Richard Allard’s brows. “You would not wish to force her hand?”

Sir Guy looked away from him. He sighed heavily. “I would not wish to do so, but I am anxious to ensure her safety and happiness. Married to a man who would not hold my views, let us say, she could endanger the security not only of herself but of all of us. Ned’s future needs to be safeguarded. I do not wish to have to hold a discreet silence within the bounds of my own family. Anne is by no means docile nor easily silenced from stating her own candid views on such uncompromising matters as the running of a household, fashion—and more volatile subjects.

“She would be safe from the pressures of State affairs in Yorkshire, and I know your lady mother would receive her joyfully.” His smile broadened. “I can recall your mother, Richard, when she and your father first met and I served him as squire.

“I trod a difficult balancing act between them, unwilling to anger him but anxious not to upset your mother, who held different opinions then from his and those she holds now. She was then, as she is now, a very gracious and courageous lady. I would be happy to think of my child in her care. I know she would neither over-cosset nor browbeat her.”

Richard Allard’s lips curved into an answering smile. He could well imagine the situation. Much of the tale of his parents’ stormy courtship and marriage had been told to him but, knowing his mother as he did, he was aware that there must have been many a skirmish between them before the state of wedded bliss had been established.

“The only bar to a proposition of marriage being offered today, sir, is the fear that I may be unable to offer Mistress Anne the security you are so anxious to gain for her. I could wish for no more suitable bride or future mistress for my Yorkshire estates than Mistress Anne.”

Sir Guy clapped him heartily upon the shoulder.

“God go with you, Richard. I shall pray for you constantly. Yet swear to me that you will take every care.”

Richard Allard threw back his head and laughed. “I am used to taking great care of my skin, sir. I shall not cease to do so when such a prize is there for me when this game is played through to its conclusion.”

Chapter Two

Anne found Richard Allard in the stables early next morning examining his horse’s new shoe. She stopped abruptly as he swung round to face her.

“Good morning, Master Allard.” She sounded a trifle breathless as if she had been running. “I trust you slept well.”

He was dressed as he had been yesterday in leather jack, warm hose and riding boots. She glanced at him hastily. “Are you planning to leave us this morning?”

His grey eyes twinkled as he surveyed her. She was looking fresh and sparkling in a plain blue woollen gown, linen coif as yesterday, pattens for crossing the littered courtyard and warm cloak. She flushed under his scrutiny, as if realising she had been rude to question her father’s guest on the matter of his departure, and made to pass by him towards the back corner where the stable cat was energetically licking her kittens. He blocked her way.

“Are you anxious to see me go, Mistress Anne?”

The flush became darker and she stammered, “Of course not, sir. It was just that I saw you dressed for riding and thought….”

“No, your father offered me his hospitality freely and I told him I would most probably leave tomorrow.”

“Oh,” she said a little lamely. “He will be glad to have you stay longer and hear in more detail about your home and parents. Ned will be delighted. He longs to travel as you have done and will hang on your every word.”

“You do not find my conversation interesting?”

“Of course I do.” She looked flustered. “But it is unlikely that I will ever have the opportunity to travel.”

“You would like to do so?”

Her blue eyes grew dreamy. “I would like to see more of the world than Rushton, certainly, though,” she added hastily, “I love the manor dearly.”

“You would like to go to Court as your mother did?”

“Yes,” she said, then defensively, “I know my father would never wish to see either Ned or I in the service of the King but…”

“You think that foolish?”

“My parents are—they have had their chances,” she murmured, her cheeks burning. “It is only natural that I would wish to see London town, see the Queen and, yes, the King also.”

“And the severed heads on Tower Bridge,” he added drily and her blue eyes grew huge and concerned.

“I had not thought…”

“Mistress Anne, you must know it would be unwise, even dangerous, for your father to go near to Westminster considering his former loyalties.”

“But other men have…”

“Changed their coats? Yes, that is certainly so and to good advantage for many of them, but it is not your father’s way.” There was utter contempt in his voice and she stepped back apace as if she feared he might strike her.

“But all that is so long ago,” she protested. “I never knew King Richard and Ned and I have to suffer for something which took place when I was just a babe in arms.”

“But I did know the King,” he returned evenly, “and so you must excuse my own partiality.”

“You knew King Richard?” Her eyes were huge again now, rounding in wonder.

“Indeed I did, I served him as page and was honoured to do so.”

“You—liked him—in spite of what they say of him?”

“I do not know to whom you have been speaking, Mistress Anne, but no one who knew the King well in the old days, except the traitors who deserted him, would say much to his discredit, certainly not to those who served formerly in his household.”

“But they say,” her voice sank to a whisper, “that he murdered his nephews.”

“Have you made such an accusation to your father?”

Her face whitened. “Oh, no, I would not dare. You will not…”

“No, I will not tell him, Mistress Anne,” he returned grimly. “But do me the courtesy of never referring to such slanderous filth again.”

This time she did withdraw from the rank fury in his tone.

“I must go,” she said hurriedly.

“Why did you come?”

“I came to see the kittens.” She glanced beyond him into the darker recesses of the stables. “And see that the one which you rescued is—” She broke off abruptly and tilted her chin. “No, actually, I saw you come in here and wanted to see if you were going to leave.”

“Ah, then you are anxious to speed my departure?”

“Yes.” Her lips trembled a little. “I think your presence here is disturbing my father’s peace.”

“You fear I might lead him into treason?”

“I think you could do so.”

“I swear to you I will do nothing to endanger him, for all your sakes.”

She gave a little relieved swallow.

They were about to leave the stable together when they heard the sounds of approaching horses and Ned breezed in and grinned at sight of Richard Allard.

“I’m glad to see you, sir. I was wondering if you would like to take a ride with me. We could go over the desmesne lands and down to the Nene, even go as far as Fotheringhay.”

Richard nodded and held up his hand for a moment’s silence then said very quietly, “Who was riding in such haste into the courtyard?”

“I don’t know.” Ned started to answer quite loudly, then, seeing their guest’s expression, immediately lowered his voice. “I didn’t wait to see…probably some boring acquaintance of my father, but I…”

He moved towards the entrance to the stable as if to ascertain the identity of the new arrivals, for it was clear from the noise and the flurry of grooms from another stable that there were at least two men who were even now dismounting. Quickly Richard Allard moved to prevent him and, as Anne, too, hastened towards the entrance he hissed in her ear fiercely, “Please stay within the stable, both of you.”

Anne was outraged by his vehemence and the hard grip upon her arm which halted her in her tracks. How dared the man impose his will upon her and in her own stable! Ned, more amenable, merely opened his blue eyes, so like his sister’s, and raised fair eyebrows at their guest in bewilderment.

Shadowed by the stable doorway, Anne and Richard Allard were able to observe the new arrivals without being seen. Instinctively she knew Richard Allard would take steps to prevent her making any sound, even to putting his other hand across her mouth. Though she gave a little surprised hiss at the sight of her father’s visitors, she made no other comment. Ned was content to remain behind them until they were able to enlighten him.

The two men handed their sweating mounts into the care of the Jarvis grooms and moved towards the manor house entrance. Still Richard Allard kept his hold on Anne’s arm until they had disappeared into the hall, then he led her firmly back into the recesses of the stable and pulled neatly close the door. Ned blinked at him in the gloom.

“They are the King’s men,” Anne said wonderingly, “wearing the royal device of the portcullis.”

“Aye,” Richard Allard said grimly. “So I noticed, Mistress Anne. I’ll ask you to remain here for a while until we have some idea of the reason for their visit.”

Ned sank obediently down upon a bundle of hay. “You don’t fear harm to my father, sir? If so, surely…”

“He’s more likely to fear harm for himself,” Anne returned contemptuously. “Isn’t that so, sir? You do not wish either my brother or I to speak of your presence here at Rushton.”

“That is so, Mistress Anne,” he said suavely. To Ned he added, “It is unlikely these men intend to arrest your father. Had there been such an intent there would have been a larger escort. It would seem these two are messengers or, possibly, they have arrived to question him on some matter which has come to the notice of the King’s council. However,” he soothed, noting Ned’s rising alarm, “it cannot pose real danger otherwise he would be arrested and carted off to London without delay.”

Ned said shrewdly, “You think they are here to question him about you? If so, my father could unwittingly speak of your presence here, surely.”

Richard Allard shook his head decisively. “Your father would not be so unwise as to fall into that mistake. No, neither he nor your mother will mention my arrival yesterday.”

“Are you wanted by the King’s men?” Anne demanded bluntly.

“Not that I am aware of. It is just that I have learned to be cautious when calling on any man whose loyalty to King Henry is held in doubt, with good reason or not, by the King’s officials. I would never compromise them. So, if you please, we will wait until they take their departure. I cannot think that will be long delayed. I heard one give instructions to the groom to rub down and water their mounts but have them in readiness to depart again within the hour.”

Sulkily Anne sank down beside her brother while Richard Allard took up a watchful position near the partially opened stable door.

Ned was still looking puzzled. He said softly, “You don’t fear that Master Allard and Father are engaged in anything…”

“Treasonable? I should think that very possible,” Anne replied coolly, “and I blame Father for it. He should have more consideration for Mother.”

“Mother is of father’s persuasion,” Ned said equably, “and when I am of age…”

“You will use more circumspection, I hope,” Anne said cuttingly.

Richard Allard moved away from the door.

“They appear to be leaving already.”

Anne could hear the men talking, but not their words. They did not sound in the least angry or put out, however, so she guessed they had been courteously received at the manor house. She waited impatiently until their horses were led out, the men mounted and she heard the clatter of their horses’ hooves upon the cobbles of the courtyard again.

“Well, Master Allard,” she snapped. “I trust we can now be released from our imprisonment.”

Ned laughed outright and waited until Richard Allard smilingly nodded his permission.

“Oh, come, Anne,” he reproved his sister. “Master Allard was only ensuring that neither of us said anything untoward in the presence of those King’s men. After all, that could have endangered Father.”

Anne knew he was right, but she only gave an angry shrug as Richard Allard opened the stable door now for them all to pass out.

Her relief at the men’s departure was short lived, however, when, entering the hall, she perceived her father was in one of his rare, uncontrollable furies. He was waving a parchment at her mother who was seated patiently by the hearth. His other hand pounded the trestle near to him.

“I will not do it,” Sir Guy shouted. “I cannot be forced to do it. I’ll not place Anne in a humiliating position. I’ll defy that usurper. He has no right…”

Lady Jarvis cautioned her husband to be circumspect when she saw Anne start anxiously at the sound of her name uttered with such an explosion of fury.

“Anne,” she said quietly, “we were wondering where you had hidden yourself, and Ned, I see you have found Master Allard.”

Sir Guy controlled his temper with difficulty and nodded to his friend.

“Ah, Dickon, I wasn’t sure where you were and also unsure whether you wished me to keep your presence here secret. Did you note our visitors from Westminster?”

“I did indeed, sir,” Richard said quietly. “I hope they brought you no disturbing news.”

“Disturbing enough.” Sir Guy indicated the parchment in his hand with disgust. “I am ordered, if you please, to present my daughter, Anne, to the Court at Westminster.”

“The letter is from the Queen, in actual fact,” Lady Jarvis interposed. “And it is more a request than a command, though, of course, it must be considered as such. She asks that Anne should come to Westminster to be a companion to Lady Philippa Telford, Lord Wroxeter’s daughter, who is to come from Burgundy to serve Her Majesty.

“Knowing Sir Guy’s past friendship with Lord Wroxeter, she thinks it would be desirable that the two girls share accommodation and duties at Court. Philippa, as you are no doubt aware, is only thirteen years old and Anne would act as a friend and chaperon.”

Sir Guy let out a pent-up gasp of pure fury.

“How can I believe this farrago of nonsense? Richard, can you believe that Wroxeter, the Tudor’s most bitter enemy, would consider the prospect of sending his daughter to Henry’s Court where she would be what amounted to a hostage to ensure Martyn Telford’s acceptance of Henry’s usurpation without further assistance to the Duchess Margaret’s attempts to unseat him?”

Richard Allard perched on a corner of the trestle. “Can I see the letter, sir?”

Sir Guy thrust it at him as if it were encrusted with filth.

Anne had been listening incredulously to this account of the contents of the letter and burst out, “But, Mother, you cannot refuse me this wonderful chance to…”

“Be silent, girl, while your betters are considering,” her father snapped. Ned shrugged uneasily and took himself some distance away out of reach of his father should an incautious word from him bring down on his head the full extent of his sire’s wrath.

Richard Allard pursed his lips and, while reading, ran his other hand through his thick brown hair in a gesture which Anne, watching, thought was probably habitual.

“It does appear strange, I grant you,” he said at last, “but reads genuine in tone. If I recall, my mother once said that Lady Wroxeter and the Queen had been close companions during the time of Queen Anne’s last illness. It could mean that Queen Elizabeth has now recollected that past friendship and wishes to offer her friend’s daughter a place at Court and the opportunity of a fair match.

“I hear Wroxeter was ailing the last time I was at Malines. They lost their second child, you know, a boy, so Lady Wroxeter must have had a hard time recently. If Wroxeter were to die, the Countess would be in straitened circumstances. Since Redmoor, Wroxeter’s lands were sequestered and their fortunes have been greatly strained as all of ours have been.

“Wroxeter may well have come to the conclusion that this offer would be in his daughter’s best interest as,” he added meaningly, “this invitation to you to send Mistress Anne to Court could be in hers.”

Sir Guy blew out his lips and, turning from them, began to pace the hall restlessly. Anne watched uneasily. She knew only too well that the haughty stride and proud, rigid set of the shoulders indicated that he was by no means satisfied with Richard Allard’s final assessment of the situation. Lady Jarvis caught their visitor’s eye and shrugged helplessly.

Anne, knowing it unwise, ventured an opinion though her mother shot her an angry glance.

“Father, I want to go. You cannot deny me this chance.”

He shot round instantly and stood regarding her, feet astride, hands clasped behind his back, his blue eyes cold with fury.

Richard Allard said quietly, “As I see it, sir, you have really no choice. The Queen’s request is a royal command, couched however kindly.”

“Then I must consent to my daughter becoming a hostage for my own compliant behaviour.”

Blue eyes met grey ones and, finally, Sir Guy’s drew away and he turned his back on them again. He gave a slight impotent movement of one hand and at length came back to the hearth and threw himself down in his chair.

He looked apologetically at his Margaret. “Forgive me, my dear. My feelings got the better of me. I cannot bear to think of Anne within the dragon’s lair.”

Anne made a little moue of concern as she recognised her father’s contemptuous reference to the King’s personal device of the Red Dragon.

Richard nodded in sympathy. “Mistress Anne is unlikely to be within the King’s presence often. She may not even be presented to him. I understand Henry frequents his wife’s apartments rarely these days. Not even those closest to the King can avoid acknowledging that he is not demonstrative.”

He gave a little bark of a laugh. “One of our spies reported that the King’s Majesty, as he insists on being referred to these days, appears to bestow his warmest caresses upon his pet monkey which disgusts and angers his councillors. The little beast is destructive, particularly to state documents, I hear.”

Sir Guy did not appear either amused or mollified by the information. He glared at his daughter who stood before him in an attitude of beseeching docility now that she had a glimmer of hope that her wildest dreams might be possible of attainment after all.

He sighed heavily. “As you say, it would be unwise to give Henry what amounted to an affront, and a refusal to comply with the Queen’s request would be received as such.”

Anne waited in an agony of suspense for his decision, her eyes modestly downcast.

“Anne has no suitable garments nor jewellery,” Sir Guy grunted at last, looking to his wife for support.

“We can manage to send her attired fittingly,” Lady Jarvis said slowly, “though it will come hard on our household purse. It will not be expected that the daughter of the disgraced Sir Guy Jarvis arrive at Court dressed extravagantly and in the height of fashion. The King would be unduly suspicious about the source of such unusual wealth and would, no doubt, manage to find a reason for fining us again, more strictly this time. However, that is not my immediate concern.”

She cast a doubtful glance at her daughter. “I fear for Anne’s safety on the journey. Guy, you should not venture into London and there are still pockets of discontent throughout the realm and some masterless men preying on travellers, many of them unfortunate remnants of the battles of Redmoor and Stoke. I shall worry—and we all know that Anne can be her own worst enemy. She says straight out what she thinks, has no skill in subterfuge and knows nothing of the lies and intrigues which makes all Courts miasmas of fear and hatred.”

“Mother, I swear I will be discreet and docile,” Anne interposed. “I would not be so foolish as to anger Her Grace the Queen or place Father in a difficult position by unwise references to his former loyalties.”

Lady Jarvis sighed. “It is not so easy to change or disguise one’s nature as you think, my girl, and your promise still does not relieve me of alarm about your journey.”

Sir Guy said doubtfully, “I trust my men and she would have Mary Scroggins with her. The woman is sensible and reliable. Thank the Virgin she takes after her mother, Kate, rather than that rapscallion, Will, her father.”

“If it would relieve your mind, Lady Jarvis, I, myself, could escort Mistress Anne to London,” Richard offered. “Sir Guy knows I have business there and could see her safely installed at Court and report to you both about her reception and accommodation there on my way home to Yorkshire.”

Anne could not have been more astonished or dismayed by this announcement and was about to remonstrate when she saw that her parents were considering this offer with considerable favour.

“If you would do that, Dickon, it would certainly relieve me of one source of anxiety,” Sir Guy said. “Unless it would mean some measure of inconvenience to you or—” his eyes searched the other’s carefully “—some element of added danger.”

“No, no, sir,” Richard replied cheerfully. “I could see Mistress Anne and her maid safely bestowed and take lodgings in London for a few weeks and keep a careful eye on the situation. If I had any cause for concern I could inform you immediately and, if necessary, take steps to remedy the matter.”

“But I would not wish—” Anne stared rebelliously at their visitor whose restricting presence on this fascinating adventure awaiting her was the very last thing she wanted. Then she realised that her father’s consent to this journey could only be gained by her willing acceptance of Richard Allard’s offer of escort and she finished lamely, “If Master Allard’s business will not be put out by this arrangement, then I shall be glad of his company on my ride south.”

Sir Guy lifted his two hands as if he was helpless to object and Lady Jarvis nodded briskly at her daughter.

“Go up to your chamber, Anne, and ask Mary to come to me in the solar. We cannot insist that she go with you. We must give her the opportunity to refuse if she is so minded though, I admit, I hope she will be willing. I would not wish you to be in any other woman’s charge during these next months.”

She rose as Anne did with alacrity. “The Queen’s messenger requested that you set out for Westminster as soon as can be arranged in order to be there when young Lady Philippa arrives. Since that is so there is a great deal to be done in preparation.”

Anne rushed towards her father and planted a kiss upon his cheek. He grinned broadly though pushing her gently aside.

“There, minx, it looks as if you will get your way as usual. Mind, I expect you to be obedient to Master Allard upon the road and give him no cause to be alarmed for your safety or angered by some stupid prank.”

Anne’s blue eyes blazed, though she quickly veiled them from her father’s gaze. Why must he continually treat her as if she were a naughty child when, within a few weeks, she would have reached marriageable age?

She sank into a little curtsy and, nodding at her mother and laughing in Ned’s direction, for he was pulling a comically wry face, she hastened from the hall in search of her maid.

Lady Jarvis bent over her husband’s fair head as he sat in the chair. She read defeat in his eyes and gently ruffled his still-bright hair.

“The Queen is Plantagenet, Guy, remember. I do not think she would wish to bring your daughter to any harm nor Lady Philippa. I think we can give Anne into Master Allard’s care readily, knowing she could have no finer mentor. I’ll go up now and see what I can to refurbish some of my old Court gowns. The materials are still fine though the style is outdated. Mary will help me. Her skill with the needle is prodigious. I’ve only recently been fashioning one of the new French hoods for Anne.”

He reached back and squeezed her hand and, as she then withdrew, he raised fair eyebrows in Richard Allard’s direction.

“By all the Saints, I hope you are all right in your assessment of this,” he said fervently.

Anne rushed up the stairs to her own chamber, calling imperiously for her maid, Mary Scroggins. The woman appeared soon enough, her sleeves rolled up to her plump elbows, for she had been carefully laundering some of the fine lawn shifts which remained of the better garments Lady Jarvis had retained from the days when coin had been more plentiful in this house. Some had been skilfully darned for none of the newer garments were so soft and delicate and Mary insisted upon dealing with Lady Jarvis’s and Anne’s garments herself.

“What is all the pother?” she enquired mildly in the familiar tones of the trusted servant. Mary had come into service at Rushton four years ago from Lady Allard’s service in Wensleydale where her mother served in attendance upon Sir Dominick and Aleyne.

Anne did not try to reprove her for insolence of tone. She regarded Mary as her trusted companion as well as her attendant.

“Mary, you will never guess…”

“I won’t unless you tell me,” the older girl replied. She was nearing nineteen years of age, brown-haired, with bright hazel eyes and plump rosy cheeks.

She had been reluctant at first to leave the only home she knew in her beloved Yorkshire but she had two other sisters who required places and her mother had insisted upon her going south into a household she knew well, for Kate Scroggins’s husband had served both Sir Dominick Allard and Sir Guy Jarvis. Mary had fitted into the household at Rushton very well and had come to love the girl, three years younger than herself, though there were times when she found Anne a handful and made no bones about telling her so.

Anne was breathless from her run upstairs. “Messengers from Court came and—and, Mary, I have been offered a place in the Queen’s household.”

“What?” Mary stared at her blankly. She was well aware of the situation that existed between those at the new King’s Court and the loyal followers of the late King Richard. “And has your father consented, Mistress Anne?”

“Well, of course, he does not wish me to go but he has had to give his consent, hasn’t he? It is the Queen’s command that I should go,” Anne returned blithely, swirling her skirts as she twisted round in a little jig of triumph. “Mother says you are to go to her in the solar and she will ask if you will go with me willingly. Mary, you will, won’t you? It will be such a grand adventure for both of us.”

“I don’t know about that,” Mary said practically. “My ma says there’s lots of disadvantages to waiting on them great ones at Court but if I don’t keep an eye on you, Mistress Anne, who else will be there to keep you out of mischief?”

“Well, on the journey, Master Allard,” Anne snapped. “Father insists he escort me.” She frowned. “He is so oafish. I do not want him beside me when I arrive in Westminster.”

“Master Richard an oaf?” Mary demanded, scandalized. “Mistress Anne, I’ll thank you to remember my ma and pa have been in service with Master Allard’s family for years and I’m telling you now he has excellent manners. His pa would stand for nothing less, even now, when he’s long been a grown man and gone travelling so far from home.”

“No, I don’t mean he’s oafish in behaviour,” Anne said, somewhat chastened, “but he’s wild and woolly in appearance, like a great shaggy dog—or a wolf,” she amended. “There’s nothing elegant about his clothes or his style of address, is there?”

Mary allowed a little secretive smile to linger round her mouth.

“His father was known as ‘Wolf Allard’, from his personal device, you know, but there was many a maid who thought his rugged looks appealing. I’ve heard many a tale about Master Richard, too. He’s had many admirers.”

“But never married,” Anne pressed. “Why not, do you think, Mary? He’s quite old, isn’t he?”

“He’s no great age for an eligible man,” Mary retorted. “He’s twenty-six or -seven, I think, a good age for deciding to settle down into matrimony, and, Mistress Anne, I’ll have you remember that the Allard lands have suffered the same deprivations of those here at Rushton. Master Allard needs to find a good wench who is worthy of him and isn’t looking for some fine, elegant young gentleman of means not to be compared to him, and not good enough to tie his points, in my opinion.”

Anne laughed. “You cannot be said to be impartial, Mary. Can I surmise you’ve admired him yourself from afar?”

“Indeed I have not,” Mary replied stoutly, “and even if I did I know my place and wouldn’t dare look so high.”

“Perhaps you are right,” Anne conceded slowly. “I am foolish to look for handsome looks and fine clothes. Oh,” she said irritably, “I am so tired of being told how necessary it is to economise. Am I pretty, Mary? Do you think some gentleman of court will find me attractive and offer for me even without a large dowry? Would not that be splendid?”

“Handsome is as handsome does,” Mary said darkly with downright Yorkshire common sense which made Anne laugh again as she held her skirts high and tripped daintily around the chamber as she imagined those grand ladies at Court did.

Anne was very concerned about the contents of the travelling chest she would carry with her to Westminster; over the next few days she watched, wrinkling her brow in doubt as her mother and Mary began to prepare those Court gowns she would need. In the end she thought she would have less need for concern for her mother’s heavy brocades and velvets were cut and restyled for her in those fashions Lady Jarvis had seen on wealthier ladies encountered in Northampton and Leicester.

She doubted the gowns were in the very latest designs but they would not disgrace Anne either in fit or quality and Anne was delighted when dressed in them and caught glimpses of herself in her mother’s travelling Venetian glass mirror. As she had inherited her mother’s dark luxuriant locks the colours suited Anne, with the rich hues of gold brocade, crimson velvet and blue samite bringing out the vivid shade of her eyes.

One gown charmed her most with its subtle draping of the overgown to the back, which Dionysia had told her was the very latest fashion. The new dark blue velvet hood trimmed with seed pearls sat well back from her glossy locks and would complement the other colours.

The day before her departure, as her sense of mingled excitement and apprehension rose, her mother sat alone with her within the solar after sending Mary on some small errand. Margaret Jarvis frowned slightly as she observed her daughter’s flushed countenance. She bit her underlip and wondered how best to broach the matter in hand.

“Anne,” she said at last, “I hope you will not pin too much hopes on future happiness at Court. I have been there and I can tell you it can be very lonely and frightening, even surrounded as one is by a veritable press of people.”

Anne eyed her thoughtfully. “But you were happy there. You loved Queen Anne for you named me after her and—and you met my father and…”

“I did not surrender to my love for your father from the first moment we met,” Lady Jarvis said tartly. “It took some time for me to learn to trust his motives and to love him truly. I do not want you to fall for the first popinjay who offers you flattery.”

“Do you judge me so foolish?” Anne demanded hotly.

“No, but your head is turned by your longing for this venture and I worry about you. You must learn to be decorous in behaviour, to keep your opinions to yourself, to accept without complaint any demand put upon you. I must also ask you to be particularly kind and protective of Lady Philippa, who is considerably younger than you. Doubtless she will feel very lost at Westminster for she was born in Burgundy and, to my knowledge, has never been to England before. Indeed, her English may not be good and it will be for you to be patient with her.”

“Perhaps she will not like me,” Anne considered, “or she may be haughty mannered. She is the daughter of an Earl.”

“Both Lord Wroxeter and his Countess are sensible, considerate people. I shall be very surprised indeed if you find their daughter lacking in either of those qualities yet she is little more than a child and you have been chosen to be her friend for specific reasons. Do not lead her into foolishness, Anne, as I know you are prone to do on occasions.”

Anne regarded her mother gravely and read very real anxiety in her eyes.

“I promise I will behave so as never to disgrace you,” she said quietly.

Margaret Jarvis hesitated and Anne turned to her sharply as if she had thought the homily was over, but, no, her mother had something else upon her mind and Anne waited in suspense for what was to come.

“Your father and I are particularly anxious that you should also behave well while under Master Allard’s care,” Lady Jarvis said with what Anne considered unusual vehemence.

That would be it, she thought sourly. They have already noted my distaste for the idea of his escort.

“I will give him no trouble, though,” she added tartly, “to hear Mary sing his praises, he is capable of dealing with any emergency which arises, a veritable paragon, Master Allard.”

“Your father thinks a great deal of Dickon Allard,” her mother said sharply. “See that you do heed him, for…” She hesitated and Anne pounced on that slight hesitation instantly.

“For?” she questioned. “What were you about to say, Mother?”

Lady Jarvis’s troubled eyes met her daughter’s challenging ones squarely.

“You might as well be told now. We have high hopes that when he has completed his business in London town Richard Allard will offer for your hand.” There, it was out and she compressed her lips as she saw first bewilderment and then pure fury dawn in her daughter’s expression.

“Marry Richard Allard?” she echoed in a high shrill tone. “You cannot mean it, Mother.”

“Why not? Despite the fines imposed after Redmoor the Allard lands are quite extensive and it would be a fair match.”

“But he is far too old for me.”

“Nonsense. Your father was almost that age when we were wed. Richard has reached the age of experience and will know how to deal with a high-strung young woman like yourself.”

“I will never consent to marry him,” Anne said through gritted teeth. “Do you hear me, never.”

Margaret Jarvis looked perplexed, then she gave way to anger.

“You will do as your father wishes, as every girl of your age must do. I cannot for the life of me understand why you are so much against the notion. Some time ago you were complaining that no one would ask for you since you are without dowry and that you wished to settle down soon, marry, have a household of your own and children.