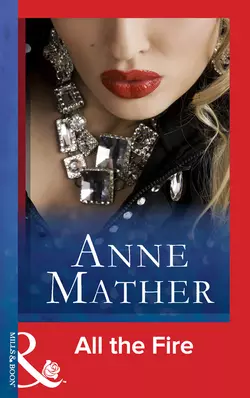

All The Fire

Anne Mather

Mills & Boon are excited to present The Anne Mather Collection – the complete works by this classic author made available to download for the very first time! These books span six decades of a phenomenal writing career, and every story is available to read unedited and untouched from their original release.Her trip to Greece has absolutely nothing to do with Dimitri Kastro! Joanne has her wedding to plan, and she would never be accompanying the impossible Dimitri back to Greece if it wasn’t her last chance to see her dying father. She is definitely not going because her heart beats faster every time the gorgeous Greek enters the room…And why would she willingly spend time with a man who has made it perfectly plain he finds her selfish and naïve? But on the beautiful Greek island where her father lives, Joanne sees another side to difficult Dimitri. Suddenly she is in danger of falling for the real Dimitri beneath the prickly exterior…

Mills & Boon is proud to present a fabulous collection of fantastic novels by bestselling, much loved author

ANNE MATHER

Anne has a stellar record of achievement within the

publishing industry, having written over one hundred

and sixty books, with worldwide sales of more than

forty-eight MILLION copies in multiple languages.

This amazing collection of classic stories offers a chance

for readers to recapture the pleasure Anne’s powerful,

passionate writing has given.

We are sure you will love them all!

I’ve always wanted to write—which is not to say I’ve always wanted to be a professional writer. On the contrary, for years I only wrote for my own pleasure and it wasn’t until my husband suggested sending one of my stories to a publisher that we put several publishers’ names into a hat and pulled one out. The rest, as they say, is history. And now, one hundred and sixty-two books later, I’m literally—excuse the pun—staggered by what’s happened.

I had written all through my infant and junior years and on into my teens, the stories changing from children’s adventures to torrid gypsy passions. My mother used to gather these manuscripts up from time to time, when my bedroom became too untidy, and dispose of them! In those days, I used not to finish any of the stories and Caroline, my first published novel, was the first I’d ever completed. I was newly married then and my daughter was just a baby, and it was quite a job juggling my household chores and scribbling away in exercise books every chance I got. Not very professional, as you can imagine, but that’s the way it was.

These days, I have a bit more time to devote to my work, but that first love of writing has never changed. I can’t imagine not having a current book on the typewriter—yes, it’s my husband who transcribes everything on to the computer. He’s my partner in both life and work and I depend on his good sense more than I care to admit.

We have two grown-up children, a son and a daughter, and two almost grown-up grandchildren, Abi and Ben. My e-mail address is mystic-am@msn.com and I’d be happy to hear from any of my wonderful readers.

All the Fire

Anne Mather

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

Table of Contents

Cover (#u07ad2a84-5258-5299-8b26-c17476cc33c0)

About the Author (#uc8c84040-a2a5-5538-bbe3-e6cc79c337c8)

Title Page (#u7b716bae-8658-5c40-bcc4-03d485da8d54)

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE (#ufcb0a138-27b9-5c53-86b0-124fdd0724a1)

DIMITRI KASTRO thrust his hands deep into the pockets of his thick sheepskin coat, his collar turned up against the unaccustomed chill of an English spring. The grim environs of the cemetery were stark against the grey sky from which a smattering of rain was beginning to fall, and the trees, skeletal bare in the fading afternoon light, gave little protection. Dimitri hunched his shoulders and thought longingly of the warmth and light of his hotel suite and the bottle of Scotch that awaited him there. But, of course, they would have to wait. He began to walk slowly along the path to where a small gathering of mourners were gathered round an open grave. Standing in the shadow of a stooping oak, he regarded the group sombrely, speculating which of them was Joanne Nicolas.

He glanced at his watch. Matt had said three-fifteen and it was already long after three-thirty, but obviously he was in time. He should have arrived sooner but he had been caught up with a business telephone call at the hotel and his departure had been delayed.

He looked again at the group. There were not many of them; a couple of middle-aged women, a middle-aged man and a boy, a young man of perhaps twenty-five, and a girl who was without doubt Joanne Nicolas. Dimitri’s expression hardened. From here he could see very little. She was tall and slim, but her features were turned away from him and her hair was concealed beneath a black headscarf. He imagined she would look a little like Matt; round features, dark hair and eyes, an amiable disposition. He felt a surge of contempt as he wondered again why she had chosen to contact her father after all these years, just to tell him his first wife, her mother, was now dead. What could it matter to her father who had been denied seeing her for twenty years? Dimitri felt that in Matt’s place he would have ignored the letter altogether, but Matt was made of gentler tissue and despite Andrea’s doubts he had determined to contact his daughter. It was natural of course that Andrea should have doubts. She had had to bear his disappointment in being denied access all these years. And there was Marisa. Obviously, she was bound to feel something when for eighteen years she had been the apple of his eye.

Dimitri stamped his feet impatiently. The service was almost over. The priest was intoning the last rites, throwing the first handful of earth on to the coffin. This was something Dimitri was familiar with, although the rest of the service had been alien to him.

He watched the girl, studying her reactions. She stood very straight and still, showing no emotion, and he wondered if she was as cold as she appeared. Surely the involvement in burying her own mother must have left some pain in her heart? He shrugged. British people were unlike his own countrymen. They were so reserved, so afraid to show their feelings. Didn’t they realize that that was what life was all about? That being involved, sharing pain and ecstasy, was part of the joy of living! Back home in Greece they would not have been afraid to cry, to shout their grief aloud. Just as in times of gaiety they were not afraid to show their excitement and pleasure. But his was a warm land with warm people, not cold and bare like this England of today.

He glanced round. His car was parked by the gate and he wondered whether the rest of this group had provided themselves with transport. He didn’t want to go to the girl’s home. Matt had said: speak to Joanne; that could be done almost anywhere. At his hotel, for example, which seemed much more suitable than someone’s living-room.

The service was soon over. The priest turned and put a reassuring hand on the girl’s arm, and then led the way back through the rows of headstones to the path. The girl followed him, her head bent, and Dimitri moved forward, allowing the priest to pass him before putting a restraining hand out and catching the girl’s arm.

‘Miss Nicolas?’ His voice sounded alien, even to himself, with its rather deep accent.

The girl halted and turned her face up to him, staring at him with wide curious eyes. Dimitri felt a muscle jerk in his cheek; she was so vastly different from anything he had imagined. She was not like Matt at all, except perhaps that she had his height and slenderness of build. Her face was oval, her skin creamy soft and flawless, while the widely spaced eyes were an amazing shade of violet and fringed with black lashes. Her mouth was wide also, but there was real beauty in her features, and her hair, as the concealing scarf slipped back to her shoulders, was that peculiar shade of ash-blonde which can appear white in some lights. It was long and straight, and fell against her cheeks now as she removed the scarf altogether.

‘Yes?’ she said now, questioningly, and her voice was slightly husky, but whether from emotion or not he couldn’t be certain.

Dimitri recovered himself and gave a slight bow of his head. He was conscious that the other members of the group had gathered about them, most closely the young man who had placed a possessive hand on her other arm and seemed poised to make some cutting retort to anything Dimitri might say. He was young, with overly long brown hair and the kind of arrogant youthfulness Dimitri had seen in the faces of students involved in demonstrations against authority. Obviously he considered Dimitri’s intervention unwelcome to say the least. But Dimitri was not perturbed. He was perfectly capable of dealing with any antagonism that might arise.

Now he looked again at Joanne Nicolas. ‘My name is Dimitri Kastro,’ he introduced himself politely. ‘I am the second cousin of your father, Matthieu Nicolas, and it is on his behalf that I am here.’ He paused, glancing rather impatiently at the attentive faces of the group around them. ‘Is there somewhere we might talk? My hotel, perhaps?’

Joanne Nicolas studied him with her composed violet eyes. ‘Dimitri Kastro?’ she murmured, shrugging her shoulders. ‘That means nothing to me.’

Dimitri controlled his impatience. ‘Why should it?’ he inquired bleakly. ‘However, you did write to your father, did you not, Miss Nicolas?’

‘To tell him of my mother’s death, yes, I did,’ she nodded.

‘Joanne?’ It was the young man who spoke now. ‘What is all this about?’

The girl shook her head, obviously not wishing to discuss her affairs here. ‘I wrote – to my father,’ she explained reluctantly. ‘I thought he had a right to know that – that Mother was dead!’ There was just a trace of emotion in her tones and Dimitri felt slightly relieved. She was not as indifferent as she would have them believe.

The young man frowned. ‘Heavens, why?’ he exclaimed, echoing Dimitri’s own sentiments. ‘He never cared about you, did he? Why should you consider him now?’

A middle-aged woman intervened. ‘Joanne,’ she said reproachfully, ‘you didn’t tell me you had written to your father.’

Joanne Nicolas looked impatiently at Dimitri. ‘I didn’t think it was necessary, Aunt Emma,’ she replied.

Dimitri glanced at the other members of the group. Then he looked again at the girl. ‘Miss Nicolas,’ he said, rather shortly, ‘I realize you are involved with your family at this time, but it is important that I should speak with you.’

She lifted her slim shoulders. She was wearing a coat of dark blue woollen cloth, its hem and collar edged with a silvery fur, and as she moved her head the lightness of her hair was startling against the darkness. At another time and in another place Dimitri would have found her disturbingly attractive, but as it was he felt a rising sense of frustration at having such difficulty in adhering to Matt’s wishes.

‘Perhaps you could come and see me tomorrow Mr. Kastro.’ She was speaking again.

Dimitri felt the muscle jerking in his cheek. ‘That would not be at all convenient, Miss Nicolas.’

The young man gave him an appraising stare. ‘Can’t you see that Miss Nicolas is upset?’ he inquired angrily. ‘She doesn’t want to be bothered with any – foreigners tonight!’

Dimitri stiffened. ‘I think we should allow Miss Nicolas to decide, don’t you?’

‘Oh, Jimmy, please!’ Joanne sighed. ‘Can’t you see I’ll have to speak to Mr. Kastro if he insists, after he’s come so far …’ She compressed her lips and looked at the others. ‘Aunt Emma, Uncle Harry, Alan, Mrs. Thwaites! Would you all mind? I mean – I don’t suppose this will take long, and there’s nothing more to do …’ She bit her lip suddenly.

The woman she had called Mrs. Thwaites came forward to press her arm understandingly. ‘Of course we don’t mind, Joanne,’ she said. ‘It’s only right that you should speak to this gentleman. Just because your parents were divorced doesn’t make you any the less your father’s daughter …’

Joanne frowned. ‘Oh, yes, Mrs. Thwaites, it does. My father and I are strangers to one another. This is a purely formal affair.’ She looked again at Dimitri. ‘Isn’t it, Mr. Kastro?’

Dimitri shrugged. ‘If you are ready … I have a car …’

The girl’s aunt snorted. ‘How do we know he’s who he says he is?’ she asked, tossing her head.

Dimitri put his hand into his jacket pocket and produced the letter Joanne had written to her father. He did it silently and Joanne studied it equally silently. ‘Shall we go then?’ she asked stiffly. The young man, Jimmy, caught her arm, but she merely shook her head, saying: ‘Go back to the house with the others, Jimmy. I won’t be long, but I’d rather be alone. Whatever Mr. Kastro has to say, it can’t take long.’

Jimmy chewed his lip. ‘All right, Jo,’ he agreed, but he was obviously put out by her attitude. ‘Do you want me to meet you in town?’

Joanne refused politely, and then said: ‘Where are you staying, Mr. Kastro?’ as though she wanted her family to know where she might be found.

‘The Bell,’ returned Dimitri uncommunicatively, and she nodded, turning to say goodbye to the others.

Dimitri thrust his hands back into his pockets and leaving her to follow him, he began to walk briskly back to his car. His impatience was not appeased by her apparent acquiescence. She was not coming with him gladly and this puzzled him. He would have thought she would have jumped at the chance to discuss her father. Why else had she written to him unless it was to try and cash in on his affairs now that Ellen Nicolas was dead and unable to offer any objections?

He reached the sleek Mercedes and glanced round. She was still hovering with the others and his impatience increased. Just who the hell did she think she was, keeping him hanging around? Did she imagine he was some kind of messenger boy for her father? Did she imagine she could treat him like she treated that long-haired youth, Jimmy? He got into the car and slammed the door deliberately, the sudden noise reaching her ears and causing her to glance his way rather anxiously.

Reaching into the glove compartment, he produced a case of cheroots and putting one between his teeth he lit it with his lighter. Drawing on it deeply, he stared grimly out at the fading day. The warmth of the car was welcoming after the chill outside, but it did not improve his temper.

A few moments later the passenger door opened and Joanne Nicolas hesitated tentatively on the point of entering.

‘Get in!’ he commanded coldly, his accent thickening in his anger. ‘You’re letting in the cold air!’

She gave him a speculative glance and then with a shrug she got in beside him, sitting as far away from him as it was possible to sit. ‘I’m sorry I’ve kept you waiting,’ she ventured politely.

‘Yes, so am I,’ remarked Dimitri dryly, and set the car in motion.

He was conscious of her resentment at his words, but he could not retract them. There was something about her attitude, her indifference, that infuriated him and he realized he would find it quite enjoyable to hurt her. His lean fingers tightened on the wheel as he swung the car on to the main Oxhampton Road. He would be glad when his part in this affair was over and he could leave this country of cold climate and cold people.

The cemetery where Ellen Nicolas had been laid to rest was on the outskirts of the town, but his hotel was quite central. However it was not a large town and it did not take many minutes to cover the couple of miles between the two. Dimitri had no intention of starting any kind of desultory conversation in the car, and as Joanne Nicolas seemed wrapped in her own thoughts they remained silent for the whole journey.

The Bell Inn was not large, but it had a reputation for comfort and good food and was the usual accommodation sought by the more affluent visitors to the town. Dimitri parked the Mercedes in the car park, and switching off the engine indicated that she should get out. He didn’t feel particularly polite and as he had little respect for Joanne Nicolas’s motives he had no intention of treating her with consideration. If she considered him rude and ill-mannered she refrained from revealing her feelings to him and did as he indicated and closed her door securely, waiting while he checked that all the doors were locked. Then as he began to walk into the hotel she accompanied him in silence.

Dimitri glanced at his watch. It was a little after four, but English licensing hours were such that the bars in the hotel were closed and he cursed the fact. It would have been easier confronting her over a drink, whereas now their only alternative was the ubiquitous afternoon tea.

Loosening his overcoat, he said: ‘We’ll go into the lounge. I don’t suppose it will be busy at this hour of the afternoon.’

In fact the lounge was deserted, but at least it was warm, and when a waiter came to ascertain their needs, Dimitri ordered afternoon tea realizing that he could not in all decency refrain from offering the girl some refreshment.

Joanne Nicolas seated herself at a table in one corner on a low banquette and after he had removed his overcoat Dimitri seated himself opposite her in a comfortable armchair. It was difficult to know where to begin, and he took out his cheroots and lit one before commencing.

‘I’m sorry I can’t offer you a cigarette,’ he commented coldly, but Joanne shook her head indifferently.

‘I don’t smoke,’ she replied calmly, and he realized she had successfully disposed of his impoliteness.

He studied the glowing tip of his cheroot for a moment, and then he said: ‘Tell me, Miss Nicolas, just why did you write to your father?’

She shrugged her slim shoulders. ‘Mr. Kastro,’ she said carefully, ‘let me say something first. I am perfectly aware from your … well … attitude that you consider my reasons for contacting my father were those of self-interest. Before we go any further, let me disabuse you of that fact!’

Dimitri’s dark eyes narrowed. ‘Indeed. Then answer my question; why contact him at all? Didn’t you know it would disturb him?’

Joanne’s eyes widened. ‘Disturb him?’ she echoed rather faintly. ‘I hardly think the death of a woman with whom he spent less than three years of his life would disturb him!’

Dimitri’s expression hardened. ‘But then you didn’t take the trouble to discover much about the man who is your father, did you, Miss Nicolas?’ he inquired bleakly.

She looked annoyed at this. ‘I suppose I was as interested in him as he was in me!’ she returned, rather heatedly.

Dimitri frowned. ‘What is that supposed to mean?’ he asked ominously.

But just at that moment the waiter came in with their tray of tea and placed it on the table in front of Joanne. Dimitri nodded his thanks and the waiter withdrew, closing the door behind him.

The girl was obviously endeavouring to control her feelings, and she used the tray of tea as an excuse for avoiding his eyes. Glancing his way, she saw that he was making no attempt to deal with the teapot and fragile tea service, so with a sigh she said: ‘Shall I?’ and took his lack of reply as assent.

But Dimitri refused any tea so that she poured only one cup and sipped it rather nervously, ignoring the delicately cut sandwiches and plates of cakes. Eventually she had to answer him, and she said slowly:

‘You must be aware, Mr. Kastro, that I have not seen my father since I was two years old.’

‘I am aware of that, yes.’ Dimitri nodded.

She looked up at him curiously. ‘Then why do you ask – what do I mean?’ She shook her head. ‘Look – this conversation hasn’t much point. My reasons for writing to my father were simple ones. I wanted to inform him that my mother was dead, that was all. I didn’t – and don’t – expect anything from him. If my letter led him to believe otherwise – then I’m sorry.’ She finished slowly as though choosing her words carefully.

Dimitri studied her intently. She certainly seemed sincere enough, and yet he could not believe the truth of it. She must know her father was a wealthy man. It was inconceivable that she should be willing to ignore the fact that he was in some way responsible for her now. It didn’t matter that she was not a child; she was Matthieu’s daughter and for him that was a lot.

She was speaking again, and Dimitri forced himself to concentrate on what she was saying: ‘If that was what you wanted to talk to me about, then I suppose our conversation is over—’ she was beginning, but he shook his head, interrupting her.

‘Just wait a moment, Miss Nicolas,’ he said, impatiently. ‘My reasons for being here have far more reaching tendencies. And our conversation has been a trifle one-sided, you will agree. However, I’m prepared to accept to a degree that your motives for writing to Matt were innocent ones, even though my brain argues that this cannot be so.’

Joanne’s eyes were disturbed now. ‘Mr. Kastro, you’ve been consistently rude and objectionable to me ever since we met this afternoon at the cemetery! And now that I have stated my case, I don’t intend to sit here any longer listening to your insinuations about my honesty—’ She rose abruptly to her feet, and with a sigh, Dimitri rose too, preventing her escape by blocking her path.

‘Calm yourself, Miss Nicolas,’ he said sourly. ‘This kind of ridiculous display will get neither of us anywhere!’

Joanne was breathing swiftly, her breast rising and falling beneath the softness of a black cashmere jumper. She had loosened her coat while she drank her tea and Dimitri could see the rounded contours of her body matched the flawlessness of her complexion. In consequence, his tone was harsher than he desired.

‘Will you get out of my way, or shall I call for assistance?’ she exclaimed angrily.

Dimitri stood aside without a word and she brushed by him, marching across the room to the door. She was certainly a magnificent young animal, thought Dimitri with reluctant admiration. How proud Matt would be of her. And Marisa? He frowned. Marisa wouldn’t like it at all.

As she reached out a hand to turn the handle, Dimitri spoke: ‘Did you know that your father has only about six months left to live?’ His voice was mild but very distinct.

Joanne halted as though carved to stone, and for a moment she did not move at all. Then slowly she turned to face him, her cheeks paling slightly and a questioning disbelief in the wide violet eyes. ‘You – you can’t be serious!’ she murmured huskily.

‘Oh, but I am,’ he returned coolly, thrusting his hands into the front pockets of his trousers.

Slowly, with hesitant steps, she came back to him, staring at him curiously as though willing him to admit he was merely trying to frighten her. Finally, when his eyes did not waver, she said: ‘But why? Why? My father is a young man! He can’t be more than about forty-five!’

‘That’s right.’

‘Then – then how?’ She shook her head.

‘A year ago he had a heart attack and it was discovered he had an organic heart disease. The doctors give him until the fall!’

Joanne pressed her fingers to her lips. ‘How terrible!’ she whispered incredulously. ‘I – I never – suspected …’

‘How could you?’ queried Dimitri, rather sardonically. ‘You’re not psychic, are you?’

‘No, but – well – I’m so sorry… .’ Her voice trailed away.

Dimitri lifted his broad shoulders in an eloquent gesture. ‘So are we all,’ he commented sombrely. ‘Your stepmother – your half-sister …’

Joanne’s face suffused with colour. ‘I have a half-sister?’ she said wonderingly. ‘I didn’t know.’

Dimitri’s eyes grew sceptical again. ‘I can’t believe that,’ he muttered roughly.

Joanne looked at him again. ‘Why not? My father did not apprise us of his affairs!’ she said stiffly.

‘Did he not?’ Dimitri raised his eyes heavenward. ‘My dear Miss Nicolas, one of us has been grossly deceived!’

Joanne bit her lip. ‘I don’t understand you.’

‘Obviously not.’

‘Stop talking in innuendoes!’ she exclaimed suddenly. ‘If you have something to say to me, say it!’

Dimitri gave her a half-smile, but it was a sardonic salutation. ‘Very well,’ he said, with a sigh. ‘Your father wrote regularly to your mother. Not only that, he continued to support you both long after it was necessary to do so!’

‘That’s not true!’ She scarcely let him finish. ‘My mother would accept nothing from my father – after – after he deserted us!’

Dimitri endeavoured to control the anger that her words aroused in him. He must try to accept that she was more innocent than he would have believed possible. ‘It is true!’ he said tightly. ‘I can prove it, if you give me time!’

Joanne’s eyes mirrored her distrust of him. ‘Is there more?’ she demanded, biting her lips.

‘Much more,’ he snapped, a trifle impatiently. ‘Much, much more! So much that I doubt my capacity for telling you without losing my temper!’

She stared at him unhappily. ‘Then don’t tell me,’ she said, rather chokingly. ‘Surely you can see you are as biased as I am?’

Dimitri heaved a sigh. ‘Won’t you sit down?’ he inquired tautly. ‘Some of this must be said. I insist. If only for the sake of your father who is still alive. Your mother is dead. What I say cannot hurt her now.’

Joanne hesitated, and then with a gesture she perched rather nervously on the edge of the banquette. ‘Very well,’ she said quietly. ‘What have you to say?’

‘Merely this,’ said Dimitri heavily. ‘Your father is a man involved with his family – every member of his family, and that includes you. Whatever has gone before, he is prepared to forgive you and take you back.’

Joanne stared at him. ‘Take me back?’ she echoed, uncomprehendingly.

‘Maybe my choice of words was unsuitable in the circumstances,’ said Dimitri, leaning his hands on the table and looking down at her. ‘But that was what your letter accomplished, Miss Nicolas!’

Joanne could not meet his gaze for long, and her lashes veiled her eyes. ‘So that was why you imagined I had written to my father,’ she said slowly. ‘Your fears were unfounded, Mr. Kastro.’

Dimitri straightened and frowned. ‘What do you mean?’

Joanne looked up. ‘Surely it’s obvious. Naturally the news of my father’s illness has shocked me, but ultimately it alters nothing.’

Dimitri uttered an expletive. ‘You don’t seem to understand what I am trying to say, Miss Nicolas,’ he affirmed with emphasis. ‘Your father sent me here to bring you back to him!’

Joanne looked positively astounded. ‘My father did what?’

‘I think you heard what I said, Miss Nicolas. What other reaction did you expect him to have?’

Joanne shook her head bewilderedly. ‘I didn’t imagine he would react in any way,’ she exclaimed. ‘After all, why should he? He never bothered about me all these years—’

‘That is not true!’ said Dimitri harshly. ‘You must not labour under that misapprehension!’

‘What do you mean?’ Her young face was strained.

‘Exactly what I say! Believe me, Miss Nicolas, this is as distasteful to me as it is to you, but it seems your mother has deceived you on various points. Your father did not abandon you without making absolutely certain you were well taken care of. And during the years since your parents’ divorce, he has regularly apprised himself of your activities.’

Joanne got unsteadily to her feet, and walked shakily across the room to where a tall window overlooked the bleak aspect of the car-park. ‘I – I can’t believe it,’ she said unevenly. ‘Why – why would my mother do a thing like that?’

Dimitri shrugged. ‘Who knows? Perhaps for the same reasons she discouraged every attempt Matt made to see you.’

Joanne swung round. ‘He tried to see me?’

‘When you were a child, yes. Your mother could not absolutely deny him the right when reasonable access had been granted by the courts, but she made it plain that any attempt he made to do so would meet with her disapproval and he realized that it would be impossible to have any kind of normal relationship with you without her condolence.’ Dimitri sighed. ‘Besides, he considered it unfair to place you between them like a bone of contention. I suppose later – after Marisa was born he became less aggressive, and Andrea naturally didn’t encourage his interest.’

‘This is the woman he married, of course,’ Joanne’s voice was chilled.

‘Yes.’

Joanne shook her head. ‘It’s incredible! I always thought my mother was completely independent. She worked, you know. She had an office job. I didn’t attribute her adequate income to anything except good housekeeping.’ She bit her lip. ‘Anyway, if my mother considered her reasons for keeping us apart were reasonable, I shouldn’t contest them.’

Dimitri studied her pale face. ‘Do you think her reasons were adequate?’

Joanne twisted the strap of her handbag. ‘I’m hardly in a position to judge. I was so young when – when they separated.’

Dimitri stifled an exclamation. ‘Obviously, it is impossible for us to discuss something so personal,’ he said brusquely. ‘However, my reasons for being here are impersonal, to me at least, and it is necessary that we should discuss them.’

‘You mean – my going to see my father?’

‘Of course.’

‘Well, that’s impossible! Absolutely impossible!’

Dimitri frowned. ‘Why?’

‘It’s not that simple,’ Joanne exclaimed. ‘I have a job to do. I can’t take time off – just like that.’

‘Then give up your job. Your father will support you.’ There was contempt in Dimitri’s expression now.

Joanne gave him an eloquent stare. ‘I prefer my independence,’ she averred quietly.

He shrugged. ‘What is your job?’

‘I’m a secretary to a group practice of doctors.’

‘Not an irreplaceable position,’ he commented dryly.

‘No. But I like it,’ she replied hotly. ‘And my holiday is fixed for June. I’m getting married then.’

‘Indeed?’ Dimitri’s voice was like ice. ‘While your father is slowly dying.’

Joanne gasped, and bent her head. ‘That’s a cruel thing to say,’ she whispered.

Dimitri took a deep breath. It was a cruel thing to say, he knew that, but he was fighting for Matt’s peace of mind. Until now it had never occurred to him that she might refuse, but to return to Matt with her refusal was untenable. Somehow she had got to be made to see sense. He clenched his fists, wishing he could simply demand that she accompany him, but he could not, and not even the hurt anguish in her eyes could deter him from doing everything in his power to get her to agree.

‘Have you ever been to Greece, Miss Nicolas?’ he asked now.

Joanne looked up. ‘No. When my parents were married my father worked in London.’

Dimitri considered this. ‘I suppose you do realize that your father is a Greek,’ he queried harshly.

Joanne stiffened. ‘Of course.’

‘Your letter was sent to the firm’s offices in Athens; don’t you know where your father actually lives?’

‘Why should I?’ she asked sharply.

Dimitri shrugged. ‘He owns an island, Dionysius. He and Andrea moved there almost ten years ago.’

Joanne compressed her lips. ‘That’s of no interest to me.’

‘Isn’t it? Aren’t you the faintest bit curious about your father? Or his second wife? Or your half-sister?’

‘What are you trying to do, Mr. Kastro?’

Dimitri clenched his fists. ‘I’m trying to make you see sense, Miss Nicolas,’ he said violently. ‘And I’m also trying to keep my temper in the face of extreme provocation!’

‘What do you mean?’

‘I mean you are a selfish young woman, Miss Nicolas, if you can continue with your life here with complete disregard for the man who sowed the seed of your conception in your mother’s womb!’ His dark face was contorted with his anger, and she moved uncomfortably.

‘What would you have me do?’ she cried.

‘I would have you go to Dionysius!’ he told her roughly. ‘I would have you make a dying man happy!’

She pressed the palms of her hands to her hot cheeks. ‘And what of my family? My fiancé?’

‘I am not asking you to abandon your fiancé,’ returned Dimitri impatiently. ‘Surely between now and June you could find the time to spend a visit with your father!’

Joanne looked confused. ‘And my job… .’ she murmured, almost to herself.

‘Leave it!’ he commanded coldly. ‘No doubt you will be leaving in June anyway.’

She frowned. ‘Why?’

‘You said you were getting married,’ he reminded her briefly.

‘In England a wife does not give up her job,’ returned Joanne, with a trace of humour.

Dimitri inclined his dark head. ‘That is indeed a pity,’ he commented expressionlessly.

She shook her head. ‘I need time to think – to talk this over with my fiancé.’

‘I presume the young man at the cemetery was your fiancé.’

‘That’s right.’

Dimitri gave a derogatory grimace. ‘Then I imagine your task will not be a pleasant one,’ he remarked. ‘I do not believe he will voice any enthusiasm for my suggestions.’

Joanne sighed. ‘Jimmy is possessive,’ she admitted.

‘He is also very stupid if he imagines a woman with independent tendencies like yourself appreciates such an attitude,’ Dimitri observed.

Joanne’s eyes darkened. ‘I don’t need your opinion, Mr. Kastro,’ she replied sharply. ‘Jimmy and his parents have been very good to both my mother and myself.’ There was a faint choking sound in her voice, and Dimitri realized he had forgotten exactly what she had been through today.

He realized, also, that he felt suddenly very weary. ‘Very well, Miss Nicolas,’ he said now. ‘I have your word that you will consider my proposition – your father’s proposition?’

Joanne nodded. ‘I don’t have much choice,’ she replied. ‘Contrary to your beliefs, Mr. Kastro, I am not without emotions, and quite honestly the prospect of meeting my father arouses my curiosity if nothing else.’ She bit her lip. ‘That’s a terrible admission to make, isn’t it, on the very day my mother is buried?’

Dimitri lifted his broad shoulders eloquently. ‘It would be unnatural for you not to be curious about your father,’ he stated. ‘We are all human, Miss Nicolas.’

Joanne sighed. ‘With human failings,’ she added.

As their interview appeared to be at an end, Dimitri walked towards the door. ‘Come,’ he said. ‘I will run you home,’ but this time she was adamant.

‘I’d rather be alone,’ she affirmed. ‘I’ll give you my decision tomorrow.’

‘At twelve.’ He was cold and businesslike, but as yet he could feel no pity for her. She nodded, and after she had gone Dimitri went swiftly up to his suite. Pouring himself a stiff drink, he loosened his tie and flung himself on the bed. He was relieved that the interview was over and yet he knew that there was something about Joanne Nicolas which would linger in his thoughts. Even while he was verbally berating her downstairs he had been aware of her attraction, and his senses had stirred in spite of himself. He felt a cynical amusement at his own vulnerability, and deliberately forced his thoughts into less disturbing channels.

CHAPTER TWO (#ufcb0a138-27b9-5c53-86b0-124fdd0724a1)

JOANNE turned into Latimer Road with some misgivings. She wished it could have been possible for her to return to the house without having to face her aunt and uncle. Aunt Emma was her mother’s only sister and obviously she would have little sympathy with any pleas Joanne might make on her father’s behalf. She was bound to support all that Joanne’s mother had done, and it would not be easy to convince her that Joanne could not in all conscience ignore everything that Dimitri Kastro had told her.

And then of course there was Jimmy to face. He had made his attitude very plain and his instant dismissal of the other man had been an instinctive effort to show his authority where Joanne was concerned. It was certainly a difficult situation, but at least it had in part banished the sense of bereavement that had previously absorbed her. Maybe she was being unreasonable in considering all that Dimitri Kastro had told her on a day when her thoughts should have been all with her mother. But in spite of everything that had gone before, Matthieu Nicolas was her father and the knowledge that he was dying had disturbed her quite badly. She couldn’t remember him at all, of course, and what little her mother had told her about him had not been complimentary, and yet Joanne had to admit to herself that he was still her parent, and as such, the closest living relative she possessed.

She reached number twenty-seven, and pushed open the gate. There were lights in the front lounge, the dullness of the day requiring the artificial illumination. She could see her aunt and uncle and their son, her cousin Alan, watching the television, while Jimmy was standing at the window and waved enthusiastically when he saw her.

He came to meet her as she entered the hall of the small house, taking her coat from her and saying: ‘You’ve been ages! You should have let me run you back.’

Joanne managed a faint smile, smoothing her hair behind her ears automatically. ‘Mr. Kastro offered to run me back,’ she said quietly, ‘but I preferred to get the bus. I needed time to think.’

‘Think? What about?’ Jimmy frowned.

Joanne sighed. ‘Lots of things.’ She moved down the hall despite his attempts to detain her. ‘Is there a cup of tea? I’m thirsty.’

Aunt Emma came bustling out of the lounge. ‘So there you are, Joanne,’ she exclaimed. ‘And about time, too. Whatever have you been doing? It’s almost six!’

Joanne shook her head. ‘Is there some tea?’ she asked, ignoring her aunt’s question.

‘Of course. Though you’d better boil up the kettle, it’s ages since it was made. We’ve all had some sandwiches. I thought we’d better get on. Mrs. Thwaites has gone. She said she had to see to her husband’s tea.’

Joanne nodded. ‘That’s all right, Aunt Emma, I can manage. Did you have plenty to eat?’

Her aunt dabbed her eyes. ‘I wasn’t particularly hungry,’ she maintained with a sniff. ‘Joanne, what did that man want with you? Foreigners! I never did trust them. Look what happened to your dear mother …’

‘Not now, Aunt Emma,’ exclaimed Joanne, brushing past her into the small kitchenette. ‘Er – Jimmy – empty the teapot, will you, love?’

Both Jimmy and her aunt were forced to accept that for the moment Joanne had no intention of divulging her affairs, so Aunt Emma returned to the lounge where she could be heard talking in undertones to her husband. Joanne half-smiled. She could guess what she was saying. She was well aware that Aunt Emma considered her whole attitude sadly lacking in sympathy, but it was simply that Joanne was not the kind of person who could publicly display her grief and consequently sometimes she appeared cold and unfeeling.

Jimmy emptied the teapot into the sink, and busied himself with the dirty dishes. If he was curious he was endeavouring to conceal it. Joanne watched him with gentle eyes. She did love him, she thought tenderly. He was so kind, so reliable, so lovable! She smiled and on impulse slid her arms round his waist from behind, hugging him.

‘Hey!’ he exclaimed, with pleasure, turning round to her. ‘What’s all this? Cupboard love?’

Joanne shook her head. ‘No, nothing much. Oh, Jimmy, what I’ve got to tell you you’re not going to like!’

Jimmy’s face darkened. ‘No? Why?’

Joanne sighed and drew back from him, aware of the change in his attitude at her words. ‘I’ve got to go to Greece,’ she said, without preamble. ‘My father wants to see me.’

Jimmy’s face registered shock, anger and disbelief in quick succession. ‘You can’t be serious!’

She nodded slowly. ‘I’m afraid I am, Jimmy. I have a reason …’

‘What possible reason can you have?’ he interrupted her. ‘My God, only hours ago you were considering the way your mother was left with you to bring up on a pittance! Now that she’s buried you’re actually considering visiting the man responsible because he sends some blasted henchman to bring you to him!’

‘No,’ protested Joanne. ‘It’s not like that.’ She sighed, seeking words to explain things to him. ‘My father is very ill – he’s dying, in fact. He wants to see me—’

‘It’s a bit late for him to want that now, isn’t it?’ sneered Jimmy, his good-humour banished. ‘What is this? Some kind of dying act of recompense? Is he making retribution for his sins?’

‘No!’ Joanne turned away, fumbling with cups and saucers. She had known Jimmy would take this badly, but what could she do? She had to go. Of that she was certain. It didn’t matter what anyone said, she had to accept that at least part of what Dimitri Kastro had said was true. ‘Jimmy,’ she pleaded, ‘try to understand.’

Jimmy slammed shut the cutlery drawer and leant back against the sink. ‘What’s there to understand?’ he snapped angrily. ‘I don’t understand you, that’s obvious!’

Joanne gave a helpless gesture. ‘I have no choice.’

‘Didn’t your mother mean anything to you, Joanne?’ he exclaimed.

‘How can you ask that?’ she whispered. ‘You know I loved her very much.’

‘Then how can you do this to her memory?’

Joanne swung round. ‘Do what? She’s dead! What I do can’t hurt her now! I have to think of my father; he’s still alive!’

‘And when did he think of you?’

Joanne didn’t want to discuss that. She didn’t want to tell Jimmy what Dimitri Kastro had said until she knew more about it. If what he had said was true then surely even Jimmy must feel less aggressive. But right now he was not likely to even listen to her.

Now, she said: ‘When my parents were divorced and my mother was given custody of me, my father made several attempts to see me. But he didn’t succeed. My mother made it plain that it would be better for me not to see him and he accepted that.’

‘I’ll bet he did!’ Jimmy hunched his shoulders. ‘I don’t suppose his second wife encouraged his interest.’

Joanne shrugged. ‘I don’t suppose she did. They have a child – a girl – my half-sister.’

Jimmy snorted. ‘How touching! And what is this visit to be? A kind of family reunion?’

‘Oh, no, nothing like that. Look, Jimmy, my father sent Mr. Kastro to ask me to come to Greece, to see him. In the normal way I would refuse outright. As it is, I can’t.’

Jimmy chewed his lower lip. ‘Because of his illness?’

‘Yes.’

‘You’re sure he is ill?’

Joanne coloured. ‘I have no reason to doubt it,’ she said stiffly.

Jimmy shook his head helplessly. ‘It doesn’t make sense! Why ever did you write to him in the first place?’

Joanne lifted her shoulders. ‘I don’t know. I just felt he should know. After all, she was his wife – his first wife.’

‘Hmmn!’ Jimmy sounded impatient. ‘You didn’t tell me you’d written.’

‘I didn’t tell anyone. Heavens, I only wrote three days ago. And these last three days haven’t exactly been easy for me!’

‘I suppose not.’ Jimmy sighed, running a hand over his hair. ‘Are you going to tell your aunt?’

‘I shall have to, shan’t I?’

‘Today?’

Joanne shook her head. ‘I don’t know.’

‘I should wait. Give her time to get over your mother’s death.’ He looked at her suddenly with speculative eyes. ‘How much time have you? When do you intend to go?’ He gave an exclamation. ‘What about your job?’

Joanne was thankful that the kettle boiled at that moment. She didn’t know how to answer him. She didn’t know sufficient about it herself to make any statements. She made the tea and added milk to the cups, hoping he would be diverted. But as she poured the tea, he said:

‘Well, Jo? What’s on your mind now?’

Joanne sighed. ‘Honestly, I don’t know myself yet. I – I – promised to meet Mr. Kastro tomorrow at twelve to give him my decision.’

Jimmy’s face brightened. ‘You mean you haven’t committed yourself?’

Joanne shook her head again. ‘No,’ she admitted. ‘But I’m going to.’

‘But why?’ Jimmy made an angry gesture. ‘You’re crazy! We’ve got a good life here, haven’t we? You’ve got a good job and so have I. In a few weeks we’ll be looking around for a house and then there’s the wedding… . How can you jeopardize everything? Can’t you write to your father and explain how things are?’

Joanne looked uncomfortable. ‘No,’ she said finally. ‘How could I write and tell a dying man that I haven’t the time – or the inclination – to visit him?’

‘And what about your job? These trips cost money.’

Joanne shrugged. ‘I expect my father will pay my fare.’

‘Oh, I see. It’s his money that interests you!’ Jimmy’s lip curled.

‘That’s a foul thing to say,’ she cried unsteadily. ‘If that’s the way you feel I can pay my own fare! I don’t want his money; not any of it!’

‘Huh!’ Jimmy turned and stared moodily out of the window at the darkened garden. ‘And what will you do if they won’t release you at the practice?’

Joanne returned her cup to its saucer, the tea untasted. ‘For goodness’ sake, Jimmy,’ she exclaimed, ‘stop asking me questions! Give me time to think about it! It was as much of a shock to me as it was to you, seeing that man at the cemetery!’

Jimmy’s eyes narrowed. ‘Bloody foreigner!’ he muttered fiercely. ‘I knew he meant trouble as soon as I saw him. What is he? Your father’s bodyguard, or something?’

‘I don’t know who he is,’ Joanne told him quietly. ‘He said he was some distant relation, a cousin or something.’ She bent her head. ‘And when you talk about foreigners remember I’m half Greek myself!’

Jimmy rolled his eyes heavenward. ‘You may have had Greek ancestors, but you’re as English as I am,’ he ex-postulated. ‘I’ve never heard you mention that before!’

Joanne lifted her shoulders. ‘I suppose like Mother I didn’t like to think about it.’

‘And now you do?’ Jimmy sounded impatient.

‘I didn’t say so.’

‘You didn’t have to.’ Jimmy hunched his shoulders. ‘Hell, this beats everything! Don’t I get any say in this at all?’

Joanne felt unutterably weary, the day finally exacting its toll upon her. ‘Jimmy, if it was your father, what would you do?’

‘That’s a bit different.’

Joanne poured the tea she had made down the sink. ‘Let’s join the others,’ she suggested tiredly, and with ill grace Jimmy preceded her into the lounge.

It wasn’t until later when Joanne was in bed that she allowed the whole weight of the problem to invade her mind. Was she being unreasonable in agreeing to go and see her father? Was she being careless of Jimmy’s – of her aunt’s – feelings? In truth only Jimmy knew as yet, but she knew if she did decide definitely to go she would have to tell her aunt if only because she would hate her to hear it from any other source, and Mrs. Lorrimer, Jimmy’s mother, knew her aunt reasonably well.

Not that she expected Jimmy to divulge her private affairs, but if he felt driven enough by his own feelings he might be unable to hide that something was wrong from his parents.

Joanne punched her pillow into shape, trying to relax. She knew she really had no need to consider the problem; she had to go. Her conscience would not allow her to refuse. And anyway, if what Dimitri Kastro had said was true then her father deserved the chance to meet his elder child.

She didn’t know who to believe. Her mother had always been so bitter when it came to her father that she had not persevered with too many questions and consequently she knew very little about their divorce. If it was true that her father had been sending her mother money all these years then her mother must have decided it was better to keep the knowledge to herself. It was hard to exist on one person’s salary, Joanne excused her thoughtfully, and who could blame anyone for accepting what was, after all, their due?

Even so, it was a little disturbing to discover that the woman around whom you had built your life had been systematically deceiving you.

Her thoughts turned to more immediate matters. The following day was Friday and she was not expected back at her desk until Monday morning. But once her decision was taken she would have to contact Dr. Hastings, the senior partner in the practice, and explain the position to him. It was extremely doubtful that he would appreciate her problems, for her work required a certain amount of local knowledge and she was very efficient in this respect. She knew most of the patients, she knew which doctor they invariably saw, and she was capable of deciding what was serious and what was not. She had been with the practice for three years and as she was rarely absent herself they relied upon her completely.

Still, she sighed, that was something she would have to face, and if they chose to dismiss her and find someone else then no doubt she would not find it too difficult to obtain another job on her return. She was an experienced secretary and she was sure that in spite of their feelings the doctors would be only too willing to supply her with a reference.

The biggest stumbling block was, of course, Jimmy. It was natural that he should feel resentful. He didn’t know all the facts and besides, he was not involved as she was. He must be made to understand the tenuous threads of a blood relationship that were impossible to destroy entirely. He hadn’t considered that she might actually want to see her father. That thought had not occurred to him. But it had occurred to Joanne, more strongly every minute, and the idea of meeting Matthieu Nicolas filled her with a forbidden sense of excitement that no amount of self-recrimination could erase. She was only human, after all, and she had never before allowed her thoughts such free rein.

Her mother had always refused to discuss personal matters with her daughter, and the little Joanne had learned had been from Aunt Emma. Naturally Aunt Emma was biased, Joanne had realized that, but even so there had had to be a certain amount of truth in what she had told her.

Her mother, Ellen, had first met Matthieu Nicolas while he was at college in London, just after the war. Ellen had been working as a secretary, taking a commercial course in the evenings. She was a couple of years older than Matthieu, but with the kind of English beauty that attracted the swarthy young Greek. When she discovered his parents were rich, she had tried to put an end to their affair, but Matthieu’s attraction had proved too great for her and eventually she had succumbed. Matthieu’s time at college ended, and when he found that Ellen wanted to stay in England, he arranged to work at the British-based branch of his father’s company. To begin with, they had been happy, but it was after Ellen became pregnant that the trouble started. Joanne had always been aware that her mother had not wanted children so early in their marriage, and in consequence she had blamed Matthieu for her condition. He on the contrary had affirmed that he wanted many children, and while on Aunt Emma’s lips that had sounded coarse and unfeeling, now Joanne wondered. Was it so unreasonable to want a large family? Had her mother been entirely reasonable in refusing to consider a second child? Joanne didn’t know. She only knew that after she was born her father began to spend time away from them, often in Athens with his family, and eventually the break-up came. There was another woman, of course, this Andrea, that Dimitri Kastro had spoken about, and now they had a daughter, too. But that was hardly the large family her father had previously planned, so maybe her mother had not been so unreasonable after all.

Joanne heaved a sigh and slid out of bed. It was impossible trying to sleep with so many thoughts tormenting her brain. It was still hard to realize that her mother was not asleep in the next bedroom, and a shiver ran through her at the knowledge that she was alone in the house. Aunt Emma had wanted to stay, but she had not encouraged her to do so. Sooner or later she would have to get used to living here alone, and the sooner the better.

But it had been a shock when she learned of her mother’s sudden illness that precipitated her death, and now the whole affair assumed overwhelming proportions.

Leaving her bedroom, Joanne went down the stairs and going into the kitchen she put on the kettle. Tea, she thought, with some sarcasm, the universal tonic.

While the kettle boiled she went into the lounge. The house was not centrally heated, but there was an all-night burner in the lounge, and now she opened it up and glanced at the clock. It was only a little after midnight. Still quite early really, but after Aunt Emma and Jimmy and the others had gone, she had gone straight to bed feeling exhausted. But not exhausted enough, obviously, she thought now.

When the doorbell rang a few minutes later she almost jumped out of her skin. ‘Wh – who is it?’ she called nervously, suddenly aware of her own vulnerability.

‘Joanne! It’s me, dear. Mrs. Thwaites,’ came a voice through the letter box, and with a sigh of relief Joanne went and opened the door.

‘Mrs. Thwaites!’ she exclaimed, in astonishment. ‘What are you doing here?’

The older woman smiled gently. ‘Oh, Joanne, I wanted to come back earlier on, but I knew your aunt was here, and Jimmy, of course, and I didn’t like to intrude. How are you? Are you all right? I was just going to bed when I saw this light come on.’ The Thwaites just lived across the road.

Joanne invited her into the lounge and said: ‘I went to bed, but I couldn’t sleep, so I’m just making some tea. Will you have a cup?’

Mrs. Thwaites’ eyes twinkled. ‘Yes, please. I never say no to tea,’ she confessed, with a chuckle.

Joanne went and made the tea, her spirits rising considerably. She liked Mrs. Thwaites. Indeed, in her younger days she had been the recipient of many of Joanne’s confidences, and had always been there with a friendly ear to listen to her troubles. Somehow her own mother had not been so easy to talk to.

When the tea was made and they were seated round the now roaring fire, Mrs. Thwaites said: ‘Well? Did you talk to Mr. Kastro? Or is it private?’

Joanne sighed. ‘Of course it’s not private,’ she said, pressing the older woman’s hand. ‘I told Jimmy, but I haven’t told Aunt Emma.’

‘Told her what? Is it about your father?’

Joanne gasped. ‘How did you know?’

‘Well, it was obviously to do with him, wasn’t it? Why else would Mr. Kastro have the letter you sent? What’s it all about, Joanne? Does he want to see you?’

Joanne stared at her in astonishment. ‘Yes.’

Mrs. Thwaites nodded. ‘I thought so. It’s only natural, isn’t it? You being his daughter, and all.’

Joanne shook her head in amazement. ‘Honestly, Mrs. Thwaites, you flabbergast me, you really do. You’re the only person who would say a thing like that, and guess what it was all about into the bargain.’

Mrs. Thwaites sighed. ‘Well, my dear, I’ve known your mother for a good many years, God rest her soul, but she was ever a hard woman where your father was concerned.’

Joanne frowned. ‘What do you mean?’

Mrs. Thwaites shook her head. ‘Oh, nothing much, dear. Tell me what that Mr. Kastro said. I’d like to hear it.’

Joanne explained everything, her expressive face mirroring her doubts as she mentioned his illness. When she had finished, even outlining Jimmy’s feelings, Mrs. Thwaites nodded slowly.

‘It’s quite a problem, for you.’

‘I know.’ Joanne stared into the fire. ‘If only Jimmy would try to understand! If he was on my side I wouldn’t care what Aunt Emma said. As it is I know she’ll appeal to him in this, and he’s likely to agree with her.’

Mrs. Thwaites sniffed. ‘Well, it seems to me you couldn’t possibly not go. He is your father, after all.’

‘You understand that?’

‘Of course. And your Jimmy might have understood it better if your father himself had come, or better still sent someone else to do his bidding.’

Joanne frowned. ‘What do you mean?’

Mrs. Thwaites compressed her lips. ‘You mean to tell me you didn’t notice what that Mr. Kastro was like?’

Joanne’s frown deepened. ‘I don’t know what you mean?’

Mrs. Thwaites clicked her tongue. ‘Oh, Joanne, it’s been a difficult day for you and I think I’m being a little saucy.’

Joanne narrowed her eyes, seeing again Dimitri Kastro’s dark features. ‘You must tell me now you’ve begun,’ she pressed her. ‘You don’t – you can’t imagine that Jimmy could be – jealous?’

Mrs. Thwaites sipped her tea. ‘Well, it’s certainly worth considering,’ she remarked dryly. ‘Good heavens, Joanne, it’s the most natural thing in the world. Take a look at yourself in the mirror some time. And you can’t deny that this man Kastro was very attractive.’

Joanne half-smiled. ‘Mrs. Thwaites!’ she murmured reprovingly.

Mrs. Thwaites chuckled. ‘Anyway, that’s what I think.’

Joanne sighed. ‘Jimmy has no need to be jealous,’ she averred firmly. ‘Mr. Kastro wasn’t my type at all. All that black hair! And he’s so dark-skinned!’

Mrs. Thwaites finished her tea and accepted another cup. ‘It was only a thought,’ she said. ‘But don’t underestimate yourself so much. I’ve seen men looking at you. And if you ask me, Jimmy has reason to be jealous. What he does not have the right to do is to get his jealousy muddled up with his feelings about your father.’

‘So you think I should go?’

‘Most definitely. Have you made a decision yet?’

‘Not officially. I’m meeting Mr. Kastro at twelve to tell him what I’ve decided.’

Mrs. Thwaites nodded. ‘And that’s what’s keeping you awake.’

‘I suppose so.’

‘Well, don’t let it. Joanne, you’re young, what are you? Twenty-one, twenty-two?’ And at Joanne’s nod, she went on: ‘You’ve all your life ahead of you, years to spend with Jimmy, while your father has only six months left. If you don’t go, in years to come, all these years that are Jimmy’s, you’ll always blame yourself for allowing him to persuade you not to go. You may even get around to blaming him, if things are bad. For heaven’s sake, child, you’re not getting married for three months. You’ve got all the time in the world!’

‘But what if I lose my job?’ exclaimed Joanne doubtfully.

‘What if you do? You’re a competent secretary. You can easily get another job. Reliable secretaries are not so easy to come by.’

‘I suppose you’re right.’

‘Of course I’m right.’ Mrs. Thwaites pressed her arm gently. ‘Joanne, you’re letting other people make your decisions, just like you’ve done all your life.’

Joanne stared at her. ‘What do you mean?’

‘You know what I mean. Your mother! You can’t deny she dictated your life almost entirely. Until her illness …’

‘It’s terrible to think that both my parents are dying so young,’ Joanne exclaimed.

Mrs. Thwaites stirred her tea thoughtfully. ‘Your mother died heedlessly, Joanne. She was warned months ago that she should have that operation. It was her own fault that she let it wait.’

‘But why did she?’

‘I wonder?’ Mrs. Thwaites sniffed. ‘Maybe she was afraid of what you might learn if she went into hospital.’

Joanne frowned. ‘You mean – about the money?’

‘I guess I do. Maybe your father wrote letters. Maybe he asked about you. She must have known you would take it badly that she hadn’t told you.’

Joanne shook her head. ‘I don’t understand why she should do such a thing.’

‘Don’t you? Your mother was a very possessive woman, Joanne, surely you realized that. After your father left, you became everything to her.’

‘A bone of contention,’ sighed Joanne unhappily.

‘A sword of victory, you mean,’ said Mrs. Thwaites almost inaudibly. ‘It must have been terribly hard for your father to accept that he no longer had a child except as a name on a certificate.’

‘You never said anything like this before,’ Joanne cried.

‘How could I? Your mother would never have forgiven me for attempting to alienate your affections. At least, that was how she would have seen it. But now, with this opportunity facing you, I feel you should be apprised of some of the facts.’

Joanne nodded. ‘I suppose you’re right,’ she agreed again. ‘I suppose Jimmy will understand eventually.’

‘If he loves you, he’ll have to,’ commented Mrs. Thwaites dryly, and Joanne was forced to agree yet again.

Much later, after Mrs. Thwaites had assured herself that there was nothing more she could do and left, Joanne returned to bed. Now she felt less indecisive. If Mrs. Thwaites thought she ought to go, too, then she couldn’t be all wrong in going, could she?

Ultimately she slept, and it was almost eleven o’clock before she woke to the realization that she was meeting Dimitri Kastro at twelve.

CHAPTER THREE (#ufcb0a138-27b9-5c53-86b0-124fdd0724a1)

THE Bell Inn was crowded with lunchtime diners when Joanne entered the reception hall a little after twelve. It was a popular eating place, although not one that Joanne had frequented previously. Pushing her way through to the reception desk, she confronted the young woman who was endeavouring to cope with the internal switchboard as well as handle inquiries. When Joanne asked for Mr. Kastro she looked rather surprised and said:

‘Is he expecting you, Miss – er …?’

‘Nicolas,’ Joanne said helpfully. ‘And yes, he is expecting me.’

The young woman raised arched eyebrows. ‘Oh, very well. Hang on a moment and I’ll ring his suite for you.’

Joanne registered the word ‘suite’ and turned to one side to await developments. Obviously whoever he was and whatever his occupation he was not without affluence. She looked about her with interest as she waited, enjoying the aromas of perfume and cigar smoke, and a faint smell of good food emanating from the restaurant. Most of the group occupying the reception hall seemed to be in a party and were gravitating towards the bar for a drink before their meal. Joanne glanced down at the suit she was wearing, wondering whether she ought to have used the cloakroom before encountering Dimitri Kastro, and then decided she was being unnecessarily self-conscious. After all, she was only here to affirm that she would go to see her father, and it was unlikely that he would notice anything about her.

When she was beginning to feel conspicuously solitary and slightly annoyed that she should be kept waiting a hand touched her arm, and she swung round hastily. Dimitri Kastro stood before her, dark and alien in a bronze-coloured suit and a cream shirt patterned with dark brown. On Jimmy the shirt would have looked informal, but Dimitri Kastro’s darkness gave elegance to his attire.

‘Good morning,’ he said politely, ‘or perhaps I should say good afternoon. I’m sorry if I have kept you waiting, but I had several business calls to make.’

Joanne gathered her composure. ‘That’s quite all right,’ she replied, equally politely. ‘I suppose I could have telephoned my decision. I didn’t think of that last night.’

Dimitri shook his head. ‘I do not care to discuss personal matters on the telephone,’ he replied smoothly. ‘And in any case, there are various arrangements to be made if you have decided to accept your father’s invitation.’

Joanne nodded. ‘I suppose so.’

Dimitri glanced round, and said: ‘Come. We will go into the residents’ bar. We can get a drink there before lunch.’

‘Lunch?’ Joanne frowned uncertainly.

‘But of course. Did I not make this plain yesterday?’

‘Frankly – no.’ Joanne wasn’t at all sure she wanted to have lunch with him. She wasn’t sure she ought to. Jimmy would be hardly likely to approve, for one thing, and for another, her relationship with Dimitri Kastro was a business one and nothing more. Even so, today, after Mrs. Thwaites’ assertions of the night before, she was aware that many women would consider it very exciting to be invited to lunch with him. Tall and broad-shouldered, with a lean hard body, he was certainly attractive, although Joanne wasn’t at all sure she liked such blatant masculinity. Besides, he was far too sophisticated for her tastes, and she didn’t much like the cynical line to his rather sensuous mouth. He looked at her as though he found women easy game and despised them for it.

Now Joanne said: ‘Perhaps we could settle our affairs over a drink, Mr. Kastro. I don’t think I should lunch with you.’

Dimitri Kastro’s dark brows ascended. ‘May I ask why?’ he queried, his accent pronounced as it sometimes was, she had noticed, when he was annoyed.

Joanne shrugged her slim shoulders. ‘Well, to be honest, my fiancé wouldn’t approve.’

The trace of a sardonic smile touched his lips. ‘Would he not?’ he commented thoughtfully. ‘But surely you are old enough to make that kind of decision for yourself.’ There was mockery in his tone.

Joanne felt a faint flush staining her cheeks. ‘That’s not the point …’ she began uncomfortably.

Dimitri Kastro began to look bored. ‘Nevertheless, I feel I must insist,’ he replied, his voice hardening. ‘I do not intend to be dictated to by your fiancé.’

Joanne sighed, and when he indicated that she should precede him across the entrance hall she did so, passing through the swing doors that separated the private apartments of the hotel from the public ones. Here the carpet was thicker, more luxurious, and the residents’ bar was attractively decorated with coloured lights and ships’ wheels. Dimitri suggested that they seated themselves at the bar, and Joanne agreed, perching on one of the tall scarlet padded stools. The bar steward was swiftly summoned and Joanne said she would have a gin and tonic. Dimitri ordered Scotch for himself, and then turned sideways to study Joanne as he spoke.

‘Now; do I take it that you have decided to accept your father’s invitation?’

Joanne ran her tongue over dry lips. ‘Yes,’ she said quickly, before she had a chance to change her mind, and then felt an immense sense of anxiety at her impulsiveness.

‘Good.’ Dimitri nodded briefly at the steward who brought their drinks. He pushed Joanne’s glass towards her, and added: ‘I rather thought you might.’

Joanne frowned. ‘You say that as though you think I have some ulterior motive for agreeing,’ she said sharply. ‘Let me assure you that my reasons are not personal ones. My fiancé is against the whole affair, and he doesn’t consider I owe my father anything. He thinks I’m crazy for going, jeopardizing my job at a time when we should be concentrating on saving for a house. As for my aunt – well, she doesn’t know yet, but she won’t like it either. She is my mother’s sister, and obviously she’ll consider I’m being unfaithful to her memory.’ Her cheeks were heated as she finished, and Dimitri toyed with his glass thoughtfully.

‘I see,’ he said, drawing out his case of cheroots. ‘This – er – young man – Jimmy; he doesn’t consider it a worthy gamble?’

Joanne stared at him incomprehensively. ‘What do you mean?’

Dimitri raised his dark brows. ‘Never mind,’ he replied evasively. ‘Come; we must discuss details.’

Joanne sipped her drink with some misgivings. She was aware that in spite of his eagerness to persuade her to go and see her father Dimitri Kastro did not trust her. But she didn’t care, she told herself with some impatience. It was actually nothing to do with him, and she couldn’t see what his involvement was. Being a distant cousin gave him no rights so far as she was concerned.

‘Tell me, Mr. Kastro,’ she said suddenly, ‘do you work for my father?’

Dimitri Kastro shook his head. ‘No. Why?’

Joanne bit her lip. ‘I just wondered. You do have a job, though, do you?’ She was being inquisitive and she knew it. After all, it was none of her business.

Dimitri gave her a sardonic smile. ‘Oh, yes, I have a job,’ he answered. Then: ‘Shall we go through to the restaurant? They’re saving a table for us.’

Joanne noticed that he had finished his drink and hastily swallowed the rest of hers. She had the uncomfortable feeling that he had deliberately snubbed her although his manner was as urbane as before.

In the restaurant the waiter escorted them to a table near the tall windows and left them with the menu. Dimitri studied his with some concentration and then said: ‘Have you any preference? Myself, I find your food lacking in variety.’

Joanne studied the list of dishes available. ‘Perhaps you ought to try the Chinese restaurant,’ she commented coolly. ‘They have a much wider variety. I understand their food is quite colourful!’

Dimitri lowered his menu and regarded her over its rim. ‘Thank you for the suggestion,’ he murmured mockingly, unperturbed by her attempt at retaliation. ‘However, there is a Greek restaurant in Brownsgate, so I’ve been informed, and if I feel the need for sustenance I can always go there!’

Joanne refrained from answering him. She felt certain that whatever she might say he would have a ready answer for her, and it was rather annoying to feel continually at a disadvantage. With Jimmy she felt his equal, but this man seemed bent on submitting her to his will. She studied him surreptitiously from behind the menu. She was aware that several feminine eyes had turned in their direction as they entered and she wondered if they were causing speculation among this gathering of business men and country squires. Although Oxhampton was only fifty miles from London it was mainly a farming community and such industry as there was was confined to dairy production. Therefore Dimitri Kastro was bound to arouse interest particularly with his foreign manner and swarthy appearance.

Finally Joanne decided to have a prawn cocktail followed by steak and salad, and with a faint smile in her direction Dimitri ordered the same. Then he ordered some wine and sat back to regard her thoughtfully.

‘Your father is delighted with your decision,’ he said casually, astounding her by the calm indifference of his statement.

Joanne, who had been silently admiring the fur coat worn by a woman just entering the restaurant, jerked her head back to stare at him in amazement. ‘I’m sorry,’ she said uneasily, ‘what was that you just said?’

Dimitri stubbed out the cheroot he had been smoking. ‘I said your father was delighted that you had agreed to come to Dionysius,’ he replied smoothly. ‘I spoke to him last evening – the telephone, you know.’ His tone mocked her astonishment.

Joanne shook her head. ‘But you didn’t know my decision last evening!’ she exclaimed.

He shrugged. ‘Let us say I presumed what it would be,’ he remarked. ‘My dear Miss Nicolas, there never was any doubt, was there? Unless you were a woman without heart, you could not deny a dying man’s last request.’

Joanne seethed, staring down at the cutlery on the table with assumed concentration. She had never met a man who was so supremely indifferent to her feelings. ‘I think you took a chance – a very big chance,’ she muttered tightly, not looking at him. ‘You couldn’t be certain that my fiancé wouldn’t stop me!’

Dimitri Kastro gave a derisive exclamation. ‘Could I not? Miss Nicolas, your fiancé could not prevent you from writing to your father …’

‘He knew nothing about it!’

‘Exactly. You kept it from him.’ Dimitri snapped his fingers. ‘And yesterday he could not prevent you from coming with me – to speak with me!’

‘That’s ridiculous! Why shouldn’t I have spoken to you?’

Dimitri shrugged. ‘Maybe you might have suggested he accompany you.’

Joanne shook her head. ‘Are you trying to say something, Mr. Kastro, because I warn you—’

‘My dear Miss Nicolas, what you do, who you involve yourself with, is your own affair. All I am saying is that the possibility of your fiancé deterring you once your mind was made up was very slight – very slight indeed!’

The waiter arrived with the wine and Dimitri tasted it experimentally before allowing it to be poured. Then, when the prawn cocktail was served, he applied himself to it with easy assurance.

Joanne was less relaxed and had to force herself to eat at all. Something about Dimitri Kastro disturbed and frightened her a little. There was a ruthlessness about him that defied any attempt at rationalization, and it was impossible to better him. With determination, she said:

‘You appear to know everything about me, Mr. Kastro, simply by deduction. It’s a pity I am not blessed with your gift of perception.’

Dimitri shrugged lazily. ‘I have known many women, Miss Nicolas. They are not the complex creatures they would have us men believe.’

‘That’s rather a cynical attitude, Mr. Kastro.’

‘Perhaps it is. Perhaps I am a cynic. In my work it is sometimes impossible to be anything else.’

Joanne eyed him curiously. ‘And what precisely is your work, Mr. Kastro?’

He did not immediately reply, for the waiter came to remove their plates and it was not until their steaks had been served that he said:

‘I am a biochemist, Miss Nicolas. A rather unsavoury subject for discussion at lunch, wouldn’t you say?’

Joanne was surprised. ‘I should think it’s a fascinating occupation,’ she replied.

He helped himself to salad and then said: ‘But not if one has a weak stomach.’

Joanne’s eyes narrowed. ‘I am not aware that my stomach is weak,’ she countered, rather impatiently.

‘Did I say it was?’ His urbane manner was infuriatingly detached.

Joanne endeavoured to tackle the food on her plate. At least his occupation suited the ruthless streak in his nature. She wondered if he had ever been married, or whether indeed he was married at present. He had not the gregarious open nature attributed to his countrymen in general and did not volunteer information with any enthusiasm. He was an enigma, and one which she ought not to be so intrigued by. Yet she was. Maybe it was his difference, his alien attitudes, his foreignness, that fascinated her. In any event, she deliberately turned her concentration to the food, determined not to give him the satisfaction of guessing her feelings. She had been engaged to Jimmy now for almost two years and in consequence this unusual involvement with another man, a stranger, was infecting her with a sense of restlessness, and it was as well that he was not too closely associated with her father.

‘Have you considered when you will leave?’ Dimitri asked suddenly, changing the subject completely.

Joanne lifted her shoulders. ‘Of course not. It’s much too soon to think of such a thing. Why?’

He drank some of his wine and would have poured more into her glass, but she put her hand over it, shaking her head. ‘I leave England at the end of next week,’ he remarked. ‘Is that too soon for you?’

Joanne’s eyes were wide with surprise. ‘The – the end of next week!’ she faltered incredulously. ‘But I never imagined anything so – so – precipitate! Yesterday you didn’t give me to understand that this was a matter of such urgency.’

Dimitri replaced his glass on the table, fingering its stem. ‘Perhaps I should be honest with you,’ he said slowly, and Joanne frowned.

‘What do you mean? Honest? Haven’t you been honest with me?’

‘I have been – how would you put it?’ He drew his brows together scowlingly, and Joanne realized it was the first time she had known him unable to put his thoughts into English. Then he nodded, with some satisfaction. ‘Diplomatic, that is it,’ he averred firmly.

Joanne sighed. ‘In what way?’

He shrugged. ‘Do not look so apprehensive, Miss Nicolas. It is simply that your father wished – hoped – that you might desire the opportunity to escape from England for a while until the memories of your mother were less painful to you. He suggested that a holiday with him might be welcome at this time.’

‘I see.’ Joanne pushed the remains of her meal aside, her appetite evaporating in uncertainty. ‘You didn’t tell me that yesterday.’

‘No. I considered it essential that you should decide on the most important aspect first; that of actually accepting your father’s invitation. I did not want to cloak the invitation with unnecessary details.’

Joanne sipped her wine rather tremulously. Things were beginning to move too fast for her. Already she was wishing she had not agreed to accept her father’s invitation without gaining Jimmy’s support, particularly after discovering that Dimitri Kastro had never expected her to refuse. And now – this! It was unnerving.

‘Even if I wanted to leave so quickly, I couldn’t possibly,’ she exclaimed. ‘I must give them notice at the practice in order to find a replacement.’

Dimitri lay back in his seat regarding her strangely. ‘The matter of your work you can leave in my hands,’ he replied summarily. ‘I guarantee to supply your employers with an adequate replacement within forty-eight hours.’

Joanne’s expression was ludicrous. ‘You can’t be serious!’

‘Why not? There are agencies in London capable of supplying slave girls for homesick Arabian oil barons!’

She hunched her shoulders helplessly. No matter what she said, what protestations she might make, he vaunted her at every turn.

‘I don’t know,’ she said now. ‘I just don’t know.’

She straightened as the waiter came to take their order for a dessert, and she made no demur when Dimitri ordered a strawberry gateau for them both.

For the rest of the meal they were silent, Joanne busy with her thoughts and unwilling to invite any more confrontations. How could she leave at the end of next week? What would Jimmy say? What reasonable excuse could she make for her actions? Unless he conceded that the sooner she went to Greece and got it over with, the better. She wished there was someone she could turn to for advice. But apart from Mrs. Thwaites she would get no encouragement from anyone, of that she was certain, and Jimmy’s parents were likely to regard her actions as nothing short of thoughtless. She was being drawn two ways at one and the same time, and she didn’t know which was right.

Dimitri Kastro ordered coffee and cognac, and then said: ‘Without wanting to appear discourteous, Miss Nicolas, I should tell you that your expression is very revealing. You’re uncertain and distrustful, and you haven’t the strength of your own convictions.’

Joanne sighed. ‘You must agree – I have a problem.’