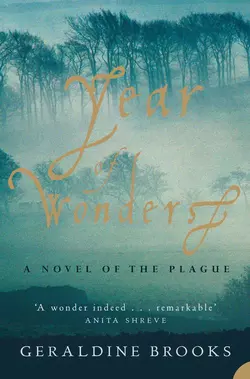

Year of Wonders

Geraldine Brooks

From the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of ‘March’ and ‘People of the Book’.A young woman’s struggle to save her family and her soul during the extraordinary year of 1666, when plague suddenly struck a small Derbyshire village.In 1666, plague swept through London, driving the King and his court to Oxford, and Samuel Pepys to Greenwich, in an attempt to escape contagion. The north of England remained untouched until, in a small community of leadminers and hill farmers, a bolt of cloth arrived from the capital. The tailor who cut the cloth had no way of knowing that the damp fabric carried with it bubonic infection.So begins the Year of Wonders, in which a Pennine village of 350 souls confronts a scourge beyond remedy or understanding. Desperate, the villagers turn to sorcery, herb lore, and murderous witch-hunting. Then, led by a young and charismatic preacher, they elect to isolate themselves in a fatal quarantine. The story is told through the eyes of Anna Frith who, at only 18, must contend with the death of her family, the disintegration of her society, and the lure of a dangerous and illicit attraction.Geraldine Brooks’s novel explores love and learning, fear and fanaticism, and the struggle of 17th century science and religion to deal with a seemingly diabolical pestilence. ‘Year of Wonders’ is also an eloquent memorial to the real-life Derbyshire villagers who chose to suffer alone during England’s last great plague.

Year of Wonders

Geraldine Brooks

a novel of the Plague

For Tony.Without you, I never wouldhave gone there.

O let it be enough what thou hast done,When spotted deaths ran arm’d through every street,With poison’d darts, which not the good could shun,The speedy could outfly, or valiant meet.

The living few, and frequent funerals then,Proclaim’d thy wrath on this forsaken place:And now those few who are return’d agenThy searching judgments to their dwellings trace.

From Annus Mirabilis, The Year of Wonders,1666, by John Dryden

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#uea0d8481-d2b1-50fd-859e-237953df8d67)

Title Page (#ue2f92fda-32d5-53bb-85b0-30171c67de16)

Epigraph (#u074ef530-89a3-5647-a93e-0becdc6018e2)

Leaf-Fall, 1666 (#ue23faa88-1637-54d8-9637-270c269dc10b)

Apple-picking Time (#u55c4486a-fd26-5fca-a857-795614048a56)

Spring, 1665 (#u34d8f06c-b279-5967-9c80-c2c9cd8caa91)

Ring of Roses (#u87b1b550-fe20-5985-af33-34edbc7ea38d)

The Thunder of His Voice (#u0f4db404-4a39-5533-b668-e7aadbabdace)

Rat-fall (#uaac63c6e-1243-5c3f-bec9-b63cd10a81ef)

Sign of a Witch (#litres_trial_promo)

Venom in the Blood (#litres_trial_promo)

Wide Green Prison (#litres_trial_promo)

So Soon to Be Dust (#litres_trial_promo)

The Poppies of Lethe (#litres_trial_promo)

Among Those That Go Down to the Pit (#litres_trial_promo)

The Body of the Mine (#litres_trial_promo)

The Press of Their Ghosts (#litres_trial_promo)

A Great Burning (#litres_trial_promo)

Deliverance (#litres_trial_promo)

Leaf-Fall, 1666 (#litres_trial_promo)

Apple-picking Time (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Afterword (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Geraldine Brooks (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Leaf-Fall, 1666 (#ulink_aee824e1-a161-50ce-81ea-5d7696eedc45)

Apple-picking Time (#ulink_e3842d02-f9b2-5b98-9eed-8107da5222d4)

I used to love this season. The wood stacked by the door, the tang of its sap still speaking of forest. The hay made, all golden in the low afternoon light. The rumble of the apples tumbling into the cellar bins. Smells and sights and sounds that said this year it would be all right: there’d be food and warmth for the babies by the time the snows came. I used to love to walk in the apple orchard at this time of the year, to feel the soft give underfoot when I trod on a fallen fruit. Thick, sweet scents of rotting apple and wet wood. This year, the hay stooks are few and the woodpile scant, and neither matters much to me.

They brought the apples yesterday, a cartload for the rectory cellar. Late pickings, of course: I saw brown spots on more than a few. I had words with the carter over it, but he told me we were lucky to get as good as we got, and I suppose it’s true enough. There are so few people to do the picking. So few people to do anything. And those of us who are left walk around as if we’re half asleep. We are all so tired.

I took an apple that was crisp and good and sliced it, thin as paper, and carried it into that dim room where he sits, still and silent. His hand is on the Bible, but he never opens it. Not anymore. I asked him if he’d like me to read it to him. He turned his head to look at me, and I started. It was the first time he’d looked at me in days. I’d forgotten what his eyes could do – what they could make us do – when he stared down from the pulpit and held us, one by one, in his gaze. His eyes are the same, but his face has altered so, drawn and haggard, each line etched deep. When he came here, just three years since, the whole village made a jest of his youthful looks and laughed at the idea of being preached at by such a pup. If they saw him now, they would not laugh, even if they could remember how to do so.

‘You cannot read, Anna.’

‘To be sure, I can, Rector. Mrs. Mompellion taught me.’

He winced and turned away as I mentioned her, and instantly I regretted it. He does not trouble to bind his hair these days, and from where I stood the long, dark fall of it hid his face, so that I could not read his expression. But his voice, when he spoke again, was composed enough. ‘Did she so? Did she so?’ he muttered. ‘Well, then, perhaps one day I’ll hear you and see what kind of a job she made of it. But not today, thank you, Anna. Not today. That will be all.’

A servant has no right to stay, once she’s dismissed. But I did stay, plumping the cushion, placing a shawl. He won’t let me lay a fire. He won’t let me give him even that little bit of comfort. Finally, when I’d run out of things to pretend to do, I left him.

In the kitchen, I chose a couple of the spotted apples I’d culled from the buckets and walked out to the stables. The courtyard hadn’t been swept in a sennight. It smelled of rotting straw and horse piss. I had to hitch up my skirt to keep it off the muck. Before I was halfway across, I could hear the thud of his horse’s rump as he turned and strutted in his confinement, gouging clefts into the floor of the stall. There’s no one strong or skilled enough now to handle him.

The stable boy, whose job it was to keep the courtyard raked, was asleep on the floor of the tack room. He jumped when he saw me, making a great show of searching for the snath that had slipped from his hand when he’d dozed off. The sight of the scythe blade still upon his workbench vexed me, for I’d asked him to mend it long since, and the timothy now was naught but blown seed head and no longer worth the cutting. I was set to scold him about this, and about the filth outside, but his poor face, so pinched and exhausted, made me swallow the words.

Dust motes sparkled in the sudden shaft of sunlight as I opened the stable door. The horse stopped his pawing, holding one hoof aloft and blinking in the unfamiliar glare. Then he reared up on his muscled haunches and punched the air, saying, as plainly as he could, ‘If you aren’t him, get out of here.’ Although I don’t know when a brush was last laid on him, his coat still gleamed like bronze where the light touched it. When Mr. Mompellion had arrived here on this horse, the common talk had been that such a fine stallion was no fit steed for a priest. And people liked not to hear the rector calling him Anteros, after one of the old Puritans told them it was the name of a pagan idol. When I made so bold as to ask Mr. Mompellion about it, he had only laughed and said that even Puritans should recall that pagans, too, are children of God and their stories part of His creation.

I stood with my back pressed against the stall, talking gently to the great horse. ‘Ah, I’m so sorry you’re cramped up in here all day. I brought you a small something.’ Slowly, I reached into the pocket of my pinafore and held out an apple. He turned his massive head a little, showing me the white of one liquid eye. I kept prattling, softly, as I used to with the children when they were scared or hurt. ‘You like apples. I know you do. Go on, then, and have it.’ He pawed the ground again, but with less conviction. Slowly, his nostrils flaring as he studied the scent of the apple, and of me, he stretched his broad neck toward me. His mouth was soft as a glove, and warm, as it brushed my hand, taking the apple in a single bite. As I reached into my pocket for the second one, he tossed his head and the apple juice sprayed. He was up now, angrily boxing the air, and I knew I’d lost the moment. I dropped the other apple on the floor of the stall and slid out quickly, resting my back against the closed door, wiping a string of horse spittle from my face. The stable boy slid his eyes at me and went silently on with his mending.

Well, I thought, it’s easier to bring a small comfort to that poor beast than it is to his master. When I came back into the house, I could hear the rector out of his chair, pacing. The rectory floors are old and thin, and I could follow his steps by the creak of the boards. Up and back he walked, up and back, up and back. If only I could get him downstairs, to do his pacing in the garden. But once, when I suggested it, he looked as if I’d proposed something as ambitious as a trek up the White Peak. When I went to fetch his plate, the apple slices were all there, untouched, turning brown. Tomorrow, I’ll start to work with the cider press. He’ll take a drink without noticing sometimes, even when I can’t get him to eat anything. And it’s no use letting a cellar full of fruit go bad. If there’s one thing I can’t stand anymore, it’s the scent of a rotting apple.

At day’s end, when I leave the rectory for home, I prefer to walk through the orchard on the hill rather than go by the road and risk meeting people. After all we’ve been through together, it’s just not possible to pass with a polite, ‘Good night t’ye.’ And yet I haven’t the strength for more. Sometimes, not often, the orchard can bring back better times to me. These memories of happiness are fleeting things, reflections in a stream, glimpsed all broken for a second and then swept away in the current of grief that is our life now. I can’t say that I ever feel what it felt like then, when I was happy. But sometimes something will touch the place where that feeling was, a touch as slight and swift as the brush of a moth’s wing in the dark.

In the orchard of a summer night, if I close my eyes, I can hear the small voices of children: whispers and laughter, running feet and rustling leaves. Come this time of year, it’s Sam that I think of – strong Sam Frith grabbing me around the waist and lifting me into the low, curved branch of a gnarly, old tree. I was just fifteen. ‘Marry me,’ he said. And why wouldn’t I? My father’s croft had ever been a joyless place. My father loved a pot better than he loved his children, though he kept on getting them, year passing year. To my stepmother, Aphra, I was always a pair of hands before I was a person, someone to toil after her babies. Yet it was she who spoke up for me, and it was her words that swayed my father to give his assent. In his eyes I was but a child still, too young to be handfasted. ‘Open your eyes, husband, and look at her,’ said Aphra. ‘You’re the only man in the village who doesn’t. Better she be wedded early to Frith than bedded untimely by some youth with a prick more upright than his morals.’

Sam Frith was a miner with his own good lead seam to work. He had a fine small cottage and no children from a first wife who’d died. It did not take him long to give me children. Two sons in three years. Three good years. I should say, for there are many now too young to remember it, that it was not a time when we were raised up thinking to be happy. The Puritans, who are few amongst us now, and sorely pressed, had the running of this village then. It was their sermons we grew up listening to in a church bare of adornment, their notions of what was heathenish that hushed the Sabbath and quieted the church bells, that took the ale from the tavern and the lace from the dresses, the ribands from the Maypole and the laughter out of the public lanes. So the happiness I got from my sons, and from the life that Sam provided, burst on me as sudden as the first spring thaw. When it all turned to hardship and bleakness again, I was not surprised. I went calmly to the door that terrible night with the torches smoking and the voices yelling and the men with their faces all black so that they looked headless in the dark. The orchard can bring back that night, too, if I let my mind linger there. I stood in the doorway with the baby in my arms, watching the torches bobbing and weaving crazy lines of light through the trees. ‘Walk slow,’ I whispered. ‘Walk slow, because it won’t be true until I hear the words.’ And they did walk slow, trudging up that little hill as if it were a mountain. But slow as they came, in the end they arrived, jostling and shuffling. They pushed the biggest one, Sam’s friend, out in front. There was a mush of rotten apple on his boot. Funny thing to notice, but I suppose I was looking down so that I wouldn’t have to look into his face.

They were four days digging out Sam’s body. They took it straight to the sexton’s instead of bringing it home to me. They tried to keep me from it, but I wouldn’t be kept. I would do that last thing for him. She knew. ‘Tell them to let her go to him,’ Elinor Mompellion said to the rector in that gentle voice of hers. Once she spoke, it was over. She so rarely asked anything of him. And once Michael Mompellion nodded, they parted, those big men, moving aside and letting me through.

To be sure, there wasn’t much there that was him. But what there was, I tended. That was two years ago. Since then, I’ve tended so many bodies, people I loved and people I barely knew. But Sam’s was the first. I bathed him with the soap he liked, because he said it smelled of the children. Poor slow Sam. He never quite realized that it was the children who smelled of the soap. I washed them in it every night before he came home. I made it with heather blooms, a much gentler soap than the one I made for him. His soap was almost all grit and lye. It had to be, to scrape that paste of sweat and soil from his skin. He would bury his poor tired face in the babies’ hair and breathe the fresh scent of them. It was the closest he got to the airy hillsides. Down in the mine at daybreak, out again after sundown. A life in the dark. And a death there, too.

And now it is Elinor Mompellion’s Michael who sits all day in the dark, with the shutters closed. And I try to serve him, although sometimes I feel that I’m tending just another in that long procession of dead. But I do it. I do it for her. I tell myself I do it for her. Why else would I do it, after all?

I open the door to my cottage these evenings on a silence so thick it falls upon me like a blanket. Of all the lonely moments of my day, this one is always the loneliest. I confess I have sometimes been reduced to muttering my thoughts aloud like a madwoman when the need for a human voice becomes too strong. I mislike this, for I fear the line between myself and madness is as fine these days as a cobweb, and I have seen what it means when a soul crosses over into that dim and wretched place. But I, who always prided myself on grace, now allow myself a deliberate clumsiness. I let my feet land heavily. I clatter the hearth tools. And when I draw water, I let the bucket chain grind on the stone, just to hear ragged noise instead of the smothering silence.

When I have a tallow stub, I read until it gutters. Mrs. Mompellion always allowed me to take the stubs from the rectory, and although there are very few nowadays, I do not know how I would manage without. For the hour in which I am able to lose myself in someone else’s thoughts is the greatest relief I can find from the burden of my own memories. The volumes, too, I bring from the rectory, as Mrs. Mompellion bade me borrow any book I chose. When the light is gone, the nights are long, for I sleep badly, my arms reaching in slumber for my babies’ small, warm bodies, jolting suddenly wakeful when I do not find them.

Mornings are generally much kinder to me than evenings, full as they are of birds’ songs and fowls’ clucking and the ordinary promise that comes with any sunrise. I keep a cow now, a boon that I was not in purse to have in the days when Jamie or Tom could have benefited from the milk. I found her last winter, wandering gaunt in the middle of the road, her hide draped loose upon her bony nethers. Her big eyes looked at me with such a vacant, hopeless stare that I felt I was gazing into a mirror. My neighbours’ cottage was empty, the ivy already creeping across the windows and the grey lichens crusting the sills. So I drove her inside and fitted it up as her boose, fattening her through the cold months with their oats – abundant food of which the dead had no need. She had her calf alone there, without complaint. By the time I found him I guess he had been born two hours, his back and sides dried out but still wet behind the ears. I helped him get his first drink, putting my fingers in his mouth and squirting her teat between them onto his slippery tongue. In return, the next night I stole a bit of her rich, yellow birth milk to make a beastings pie, baked with egg and sugar, and took it to Mr. Mompellion, rejoicing when he ate it as if he were my child, thinking how Elinor would be glad of it. The little bull calf is sleek now, and his mother’s brown eyes regard me with a kindly patience. I love to lean my head against her warm flank and breathe the scent of her hide as the steaming milk foams into my bucket. I carry it to the rectory to make a posset or churn sweet butter or skim the cream to serve with a dish of blackberries – whatever I think will best tempt Mr. Mompellion. When I have enough in the pail for our small needs, I turn her out to graze. She has fattened so since last winter that every day now I fear she will lodge halfway through the doorway.

Bucket in hand, I leave the cottage by the front door, for in the mornings I feel more able to meet whomever might be abroad. We live all aslant here, on this steep flank of the great White Peak. We are always tilting forwards to toil uphill, or bracing backwards on our heels to slow a swift descent. Sometimes, I wonder what it would be like to live in a place where the land did not angle so, and people could walk upright with their eyes on a straight horizon. Even the main street of our town has a camber to it, so that the people on the uphill side stand higher than those on the downhill.

Our village is a thin thread of dwellings, unspooling east and west of the church. The main road frays here and there into a few narrower paths that lead to the mill, to Bradford Hall, the larger farms, and the lonelier crofts. We have always built here with what we have to hand, so our walls are hewn of the common grey stone and the roofs thatched with heather. Behind the cottages on either side of the road lie tilled fields and grazing commons, but these end abruptly in a sudden rise or fall of ground: the looming Edge to the north of us, its sheer stone face sharply marking the end of settled land and the beginning of the moors, and to the south, the swift, deep dip of the Dale.

It is a strange prospect, our main street these days. I used to rue its dustiness in summer and muddiness in winter, the rain all rizen in the wheel ruts making glassy hazards for the unwary stepper. But now there is neither ice nor mud nor dust, for the road is grassed over, with just a cow-track down the centre where the slight use of a few passing feet has worn the weeds down. For hundreds of years, the people of this village pushed Nature back from its precincts. It has taken less than a year to begin to reclaim its place. In the very middle of the street, a walnut shell lies broken, and from it, already, sprouts a sapling that wants to grow up to block our way entire. I have watched it from its first seed leaves, wondering when someone would pull it out. No one has yet done so, and now it stands already a yard high. Footprints testify that we are all walking round it. I wonder if it is indifference, or whether, like me, others are so brimful of endings that they cannot bear to wrench even a scrawny sapling from its tenuous grip on life.

I made my way to the rectory gate without meeting any soul. So my guard was down and I was unready to face the person who, in all the world, I least wished to see. I had entered the gate and had my back turned to the house, refastening the latch, when I heard the rustle of silk behind me. I turned suddenly, slopping milk from my bucket as I did so. Elizabeth Bradford scowled as a droplet landed on the aubergine hem of her gown. ‘Clumsy!’ she hissed. And so I reencountered her much as I had last seen her more than one year earlier; sour-faced and spoiled. But the habits of a lifetime are hard-shed, and I had dropped into a curtsy without willing it, my body acting despite the firm resolve of my mind to show this woman no such deference.

Typically, she did not even bother with a greeting. ‘Where is Mompellion?’ she demanded. ‘I have been rapping upon that door for a good quarter hour. Surely he cannot be so early abroad?’

I made my voice unctuously polite. ‘Miss Bradford,’ I said, ignoring her question, ‘it is a great surprise, and an honour unlooked for, to see you here in our village. You left us in such haste, and so long since, that we had despaired of ever more being graced by your presence.’

Elizabeth Bradford’s pride was so overweening and her understanding so limited that she heard only the words and missed the tone. ‘Indeed.’ She nodded. ‘My parents were well aware that our departure would leave an unfillable gap here. They have always felt their obligations most keenly. It was, as you know, that sense of obligation that caused them to remove us all from Bradford Hall, to preserve the health of our family so that we could continue to fulfil our responsibilities. Surely Mompellion read my father’s letter to the parish?’

‘He did,’ I replied. I did not add that he had used it as an occasion to preach one of the most incendiary sermons we ever had from him.

‘So, where is he? I have been kept waiting long enough already, and my business is urgent.’

‘Miss Bradford, I must tell you that the rector sees no one at present. The late events in this place, and his own grievous loss, have left him exhausted and quite unequal to shouldering the burdens of the parish at this time.’

‘Well, that may be, insofar as the normal run of parishioners is concerned. But he does not know that my family is returned here. Be so good as to inform him that I require to speak with him at once.’

I saw no purpose in further discourse with this woman. And I have to own that I was consumed with curiosity to see if the news of the Bradfords’ return would rouse Mr. Mompellion, or draw forth any sign of feeling. Perhaps wrath could rouse him where charity had not. Perhaps he needed to be singed by just such a brand.

I swept by her and walked on ahead to open the rectory’s great door. She pinched her face at this; she was not accustomed to sharing a doorway with servants, and I could see she had expected me to pass to the kitchen garth and then come and let her in with accustomed ceremony. Well, times had changed in the Bradfords’ absence, and the sooner she accustomed herself to the inconveniences of the new era the better.

She pushed past me and found her own way to the parlour, pulling off her gloves and flicking them impatiently against the palm of her hand. I saw the surprise in her face as she registered the bareness of the room, stripped as it was of all its former comforts. I went on to the kitchen. No matter how urgent her business, she would have to wait until Mr. Mompellion broke his fast, since that scant serving of oatcake and brawn was the only meal I knew with any certainty that he would take. She was pacing, barely able to contain herself, as I passed by some minutes later with the laden tray. I glimpsed her through the open door. Her brow was drawn so low, her scowl so deep, that she looked as if someone had grabbed her face from beneath and dragged it groundwards. Upstairs, I took a minute to compose myself before I knocked on the door. I did not want to say, or look, more than I should when I announced to the rector his caller.

‘Come,’ he said. He was standing by the window when I entered, and the shutters, for once, were opened. His back was to me as he spoke. ‘Elinor would be sorry to see what has become of her garden,’ he said.

I did not know at first how to answer that. To speak the evident truth – yes, indeed, she would – seemed likely only to feed his gloom. To deny his proposition would be a falsehood.

‘I expect she would understand why it is so,’ I said, bending to set out the dishes from his tray. ‘And even if we had hands enough to do the ordinary tasks – to pull the weeds and prune the dead-wood – yet it would not be her garden. We would lack her eye. What made it her garden was the way she could look at a handful of tiny seeds in the bareness of winter and imagine how they would be, months later, sunlit and in flower. It was as if she painted with blooms.’

When I straightened, he had turned and was staring at me. The shock of it went through me once again.

‘You knew her!’ He said it as if it had only just come to him.

To cover my confusion, I blurted out what I had hoped to convey with care. ‘Miss Bradford is in the parlour. The family is returned to the Hall. She says she needs to speak with you urgently.’

What happened next astonished me so much that I almost dropped the tray. He laughed. A rich, amused laugh the like of which I hadn’t heard for so long I’d forgotten the sound of it.

‘I know. I saw her. Banging on my door like a siege engine. Truly, I thought she meant to break it down.’

‘What answer should I give her, Rector?’

‘Tell her to go to Hell.’

When he saw my face, he laughed again. My eyes must have been wide as chargers. Wiping a tear of mirth from his own, he struggled for composure. ‘No, I see. You can barely be expected to carry such a message. Put it into whatever words you like, but convey to Miss Bradford that I will not see her, and get her from this house.’

It was as if there were two of me, walking down those stairs. One of them was the timid girl who had worked for the Bradfords in a state of dread, fearing their hard looks and harsh words. The other was Anna Frith, a woman who had faced more terrors than many warriors. Elizabeth Bradford was a coward. She was the daughter of cowards. As I entered the parlour and faced her thunderous countenance, I knew I had nothing more to fear from her.

‘I am sorry, Miss Bradford, but the rector is unable to see you at present.’ I kept my voice as level as I could, but as her jaw worked in that angry face, I found myself thinking of my cow worrying at her cud, and I felt the contagion of Mr. Mompellion’s strange fit of mirth. It was all I could do then to keep my composure and continue. ‘He is, as I said, not currently performing any pastoral duties, nor does he go into society or receive any person.’

‘How dare you smirk at me, you insolent slattern!’ she cried. ‘He will not refuse me, he dare not. Out of my way!’ She moved for the door, but I was quicker, blocking her path like a collie facing down an unruly tup. We stared at each other for a long moment. ‘Oh, very well,’ she said, picking up her gloves from the mantel as if purposing to leave. I stood aside then, meaning to show her to the front door, but instead, she pushed past me and was upon the steps to Mr. Mompellion’s room when the rector himself appeared on the landing.

‘Miss Bradford,’ he said, ‘do me the kindness of remaining where you are.’ His voice was low but its jussive tone stopped her. He had shed the hunched posture of the past months and stood tall and straight. He had lost flesh, but now, as he stood there, animated at last, I could see that gauntness had not ravaged him but rather given his face a kind of distinction. There had been a time when, if you looked at him when he was not speaking, you might have called his a plain face, save for the deep-set grey eyes that were striking, always, for their expressiveness. Now, the hollowness of his cheeks called attention to those eyes, so that you could not take your gaze from them.

‘I would be obliged if you would refrain from insulting members of my household whilst they are carrying out my instructions,’ he said. ‘Please be good enough to allow Mrs. Frith to show you to the door.’

‘You can’t do this!’ Miss Bradford replied, but this time in the tone of a very young child who has been thwarted in its pursuit of a plaything. The rector was standing half a flight of stairs above her, so that she had to gaze up at him like a supplicant. ‘My mother has need of you…’

‘My dear Miss Bradford,’ he interrupted coldly. ‘There were many people here with needs this past year, needs that you and your family were in a position to have satisfied. And yet you were not…here. Kindly ask your mother to do me the honour of advancing the same tolerance for my absence now that your family arrogated for so long in regard to its own.’

She was flushed now, her face a blotchy patchwork. Suddenly, surprisingly, she began to cry. ‘My father is not any longer…my father does not…It is my mother. My mother is very ill. She fears…she believes she will die of it. The Oxford surgeon swore it was a tumour but there is no question now…Please, Reverend Mompellion, her mind is much disordered; she will take no rest and speaks of nothing but seeing you. That is why we are come back here, that you may console her and help her face her death.’

He was silent for a long moment, and I felt sure that his next words would be a request to me to look out his coat and hat so that he could go to the Hall. His face, when he spoke, was sad, as I had so often seen it. But his voice was strange and rough.

‘If your mother seeks me out to give her absolution like a Papist, then she has made a long and uncomfortable journey to no end. Let her speak direct to God to ask forgiveness for her conduct. But I fear she may find Him a poor listener, as many of us here have done.’ And with that he turned his back and climbed the stairs to his room, closing the door behind him.

Elizabeth Bradford threw out a hand to steady herself and gripped the banister until bone of her knuckles showed through the skin. She was trembling, her shoulders shaking with sobs that she struggled to suppress. Instinctively, I went to her. Despite my years of aversion for her, and hers of contempt for me, she folded up into my arms like a child. I had meant to help her to the door, but she was in such a state that I could not bring myself to shove her out, though it was clearly the rector’s wish that she be gone. Instead, I found myself shepherding her to the kitchen and easing her down upon the bucket bench. There, she gave herself up so completely to sobbing that the little piece of lace she used as a handkin was soaked through. I held out a dishclout, and to my astonishment she took it and blew her nose as indelicately and unselfconsciously as an urchin. I offered her a mug of water and she drank it thirstily. ‘I said the family was back, but in truth it is just my mother and me and our own servants. I do not know how I can help her, she grieves so. My father will have none of her ever since he learned the truth of her condition. My mother has no tumour. But what she has, at her age, may surely kill her just the same. And my father says he cares not. He has ever been cruel to her, but now he excels himself in his wretchedness. He is saying the most terrible things…He has called his own wife whore…’ And there she finally stopped herself. She had said more than she intended. Far more than she should. Rising from the bench as if it had suddenly turned to a hob that was blistering her noble backside, she squared her shoulders and handed me the soiled dishclout and the empty mug without a thank you. ‘I can find my own way out,’ she said, brushing past me without a glance. I did not follow her, but I knew she was gone by the slam of the great oaken door.

It was only with her going that I gave myself pause to be astonished by what Mr. Mompellion had said to her. His mind had become even darker than I had thought. I was concerned for him. I did not know what I could do to bring him comfort. Nevertheless, I climbed the stairs to his room as quietly as I could and listened outside his door. Inside there was silence. I knocked gently, and when he did not answer I opened the door. He was seated with his head in his hands. The Bible, as always, was beside him, unopened. I had a sudden, keen memory of him, sitting just so, at the end of one of the darkest days of the past winter. The difference was that Elinor had been seated beside him, her gentle voice reading from the Psalms. It was as if I heard it still, a low hum, so soothing, broken only by the soft rustle as she turned the pages. Without asking his leave, I picked up the Bible and turned to a passage I knew well:

‘Bless the Lord, O my soul;

And forget not all his benefits,

Who forgives all your iniquity,

Who heals all your diseases,

Who redeems your life from the Pit…’

He rose from his chair and took the book from my hand. His voice was low, but brittle. ‘Very well read, Anna. I see my Elinor may add a credential as a fine teacher to her catalogue of excellent qualities. But why did you not choose this one?’ He flipped a few pages, and began to declaim:

‘Your wife will be like a fruitful vine

Within your house;

Your children will be like olive shoots

Around your table…’

He raised his eyes and glared at me. Then slowly, deliberately, he opened his hand. The book slipped from his fingers. Instinctively, I leapt forward to catch it, but he grabbed my arm, and the Bible hit the floor with a dull thump.

We stood there, face-to-face, his hand tightening on my forearm until I thought he might break it. ‘Rector,’ I said, struggling to control my voice. At that, he dropped my arm as if it were a burning brand and raked his hand through his hair. The pressure of his grip had left a welt, throbbing. I could feel the tears welling in my eyes, and I turned away so that he would not see them. I did not ask his leave to go.

Spring, 1665 (#ulink_21a85695-016b-5fc2-8492-375b7fe6639f)

Ring of Roses (#ulink_e3a2fb91-56cd-56ac-8202-5a06173f6151)

The winter that followed Sam’s death in the mine was the hardest season I had ever known. So, in the following spring, when George Viccars came banging on my door looking for lodging, I thought God had sent him. Later, there were those who would say it had been the Devil.

Little Jamie came running to tell me, all flushed and excited, tripping over his feet and his words. ‘There a man, mummy. There a man at the door.’

George Viccars swept his hat from his head as I came from the garth, and he kept his gaze down on the floor, respectfully. Different from all those men who look you over like a beef at saleyard. When you’re a widow at eighteen, you grow used to those looks and hard towards the men who give them.

‘If you please, Mistress Frith, they told me at the rectory you might have a room to let.’

He was a journeyman tailor, he said, and his own good, plain clothes told that he was a competent one. He was clean and neat even though he’d been on the road all the long way from Canterbury, and I suppose that impressed me. He had just secured a post with my neighbour, Alexander Hadfield, who presently had a surfeit of orders to fill. He seemed a modest man, and quiet-spoken, although when he told me he was prepared to pay sixpence a week for the attic space in my eaves, I’d have taken him if he was loud as a drunkard and muddy as a sow. I sorely missed the income from Sam’s mine, for I was still nursing Tom, and my small earnings from the flock were only a little augmented by my mornings’ work at the rectory and occasional service at the Hall, when they needed extra hands. Mr. Viccars’s sixpence would mean a lot in our cottage. But by the end of the week, it was me who was ready to pay him. George Viccars brought laughter back into the house. And later, when I could think at all, I was glad that I could think about those days in the spring and the summer when Jamie was laughing.

The young Martin girl minded the baby and Jamie for me while I worked. She was a decent girl and watchful with the children but Puritan in her ways, thinking that laughter and fun are ungodly. Jamie misliked her sternness and was always so glad when he’d see me coming home that he’d rush to the door and grab me around the knees. But the day after Mr. Viccars arrived, Jamie wasn’t at the door. I could hear his high little laugh coming from the hearth, and I remember wondering what had come over Jane Martin that she’d actually brought herself to play with him. When I got to the door, Jane was stirring the soup with her usual thin-lipped glare. It was Mr. Viccars who was on the floor, on all fours, with Jamie on his back, riding around the room, squealing with delight.

‘Jamie! Get off poor Mr. Viccars!’ I exclaimed. But Mr. Viccars just laughed, threw back his blond head, and neighed. ‘I’m his horse, Mrs. Frith, if you’ve no objection. He’s a very fine rider, and he rarely beats me with the whip.’ The day after that, I came home and found Jamie decked out like a Harlequin in all the fabric scraps from Mr. Viccars’s whisket. And the day after, the two of them were at work slinging oat sacks from the chairs to make a hiding house.

I tried to let George Viccars know how much I valued his kindness, but he brushed my thanks away. ‘Ah, he’s a fine little boy. His father must have been more than proud of him.’ So I tried to repay him by making a better table than we might otherwise have had, and his praise for my cooking was generous. The neighbour towns at that time had no tailor, so Mr. Hadfield had work to spare for his new assistant. Mr. Viccars would sew long into the evening, burning down a whole rushlight as he sat late by the fire plying his needle. Sometimes, when I was not too tired, I would set myself some chore near the hearth to keep him company awhile, and he would reward me with many tales of the places he’d sojourned. He had seen much for a young man, and his powers of description were good. Like most in this village, I had no occasion to travel farther than the market town seven miles distant. Our closest city, Chesterfield, lies twice as far, and I never had cause to journey there. Mr. Viccars knew the great cities of London and York, the bustling port life of Plymouth, and the everchanging pilgrim trade at Canterbury. I was pleased to hear his stories of these places and the manner of life of the people biding there.

These were a kind of evening I’d never had with Sam, who looked to me for all his information of the tiny world for which he cared. He liked to hear only of the villagers he’d known since childhood, the small doings that defined their days. And so I gave him such news as the arrival of Martin Highfield’s new bull calf and the expectation of Widow Hamilton for her wool-clip. He was content just to sit, exhausted, his big frame spilling from the chair that seemed so small when he was in it. I would prattle of what I’d heard of the villagers and the children’s doings and he would let the words wash over him, gazing at me with a half smile no matter what I said. When I ran out of talk, his smile would widen and he’d reach for me. His hands were big, cracked things with broken, blackened nails, and his idea of lovemaking was a swift and sweaty tumble, a spasm and then sleep. Afterward, I would lie awake under the weight of his arm and try to imagine the dim recesses of his mind. Sam’s world was a dark, damp maze of rakes and scrins thirty feet under the ground. He knew how to crack limestone with water and with fire; he knew the going rate for a dish of lead; he knew whose seams were likely to be Old Man before the year turned, and who had nicked whose claim up along the Edge. Inasmuch as he knew what love meant, he knew he loved me, and all the more so when I gave him the boys. His whole life was confined by these things.

Mr. Viccars seemed never to have been confined at all. When he entered our cottage, he brought the wide world with him. He had been born a Peakrill lad in a village near to Kinder Scout but had been sent off to Plymouth to take up tailoring, and in that port town had seen silk traders who traversed the Orient and had befriended lace makers even from among our enemies the Dutch. He could tell such tales: of Barbary seamen who wrapped their copper-coloured faces in turbans of rich indigo; of a Musalman merchant who kept four wives all veiled so that each moved about with just one eye peeking from her shroud. He had gone to London at the end of his apprenticeship, for the return and restoration of King Charles II had created prosperity among all manner of trades. There, he had enjoyed much work sewing liveries for courtiers’ servants. But the city had tired him.

‘London is for the very young and the very rich,’ he said. ‘Others cannot long thrive there.’ I smiled and said that since he had yet to pass his middle twenties he seemed young enough to me to be able to dodge footpads and withstand late nights in alehouses.

‘Maybe so, Mistress,’ he replied. ‘But I grew tired of seeing no farther than the blackened wall at the opposite side of the street and hearing nothing but the racket of carriage wheels. I longed for space and for good air. You cannot believe that what men breathe in London really is air at all, for the coal fires send soot and sulphur everywhere, fouling the water and turning even the palaces into grimy, black hulks. The city is like a corpulent man trying to fit himself into the jerkin he wore as a boy. So many have moved there looking for work that souls are heaped up to live ten and twelve to a room no larger than the one we sit in. Poor souls have tried to add on to their dwellings and garner space as they can, so that misshapen parts of buildings lean out across the alleyways and teeter high atop decaying roofs that you wonder can hold the weight. The gutters and spouts are fixed on any how, so that even long after rain has passed, the wet drips down upon you to leave you always clammy damp.’

He had also grown weary, he said, of gentlemen who bespoke a household’s liveries and then left him to wait a year or more for the settlement of his accounts. ‘And I can tell you that by then I felt myself lucky to be paid at all,’ he added, for he had had colleagues driven destitute by lordly defaulters.

When he had ascertained I was not by any means of a Puritan bent, he shared with me some tales of the bawdiness and carousing he had witnessed in the city after the king sailed home from exile. At first I felt sure he embroidered these as skilfully as the fabrics under his hand, and so I challenged him one evening, as we sat companionably, he on the floor, long legs crossed and draped with the linen piece he was stitching, me at the table, my fingers greasy as I patted out the oatcakes and slung them up on a string before the fire to dry.

‘No, Mistress. If anything, I am exaggerating in the contrariwise direction, for I have no wish to offend you.’

I laughed at this and told him I was not too nice to hear the truth and wished to know how things stood in the world. I may have urged him too much in this way, or perhaps it was the second mug of my own good ale that I poured for him, for he launched then into some tales of the king travelling in disguise to a whorehouse and having his pockets thoroughly picked there. Mr. Viccars was surprised when I laughed at this and told him I hoped the lady in question made off with a king’s ransom, for certainly she had earned it in servicing such a one and many worse.

‘You don’t blame her for choosing a living of lustfulness and debauchery?’ he enquired, his eyebrow raised in mock severity.

‘May be I might,’ I replied. ‘But before I blamed, I would like to know the extent of her choices in the hard world that you have described to me. If you are drowning in a sewer, your first concern might be that you are drowning, not how vile you smell.’ Perhaps I spoke too frankly at this, for his next revelation about the works of the king’s favourite poet, the Earl of Rochester, did shock me, so much so that I remember yet the main part of the lines he declaimed. Mr. Viccars was a fine mimic. Before he gave me the verses, he fixed his frank, open countenance into a parody of a foppish sneer and turned his own gentle voice into a lordly bray:

‘I rise at eleven, I dine at two,

I get drunk before seven, and the next thing I do

I send for my whore when, for fear of the clap,

I come in her hand and I spew in her lap…’

I didn’t let him get any further in his recitation, stopping my ears with my hands and excusing myself directly, for truly although I am loath to judge others, I can scarce credit that the nobles and gentry who so stand upon their superiority to such as we can yet be so base as to make the worst of us seem like angels. Later, lying in my room with my babies curled on the pallet beside me, I was sorry I had acted so. I longed to learn about the places and the people that I could never hope to see, and now I feared I would appear such a prude to Mr. Viccars that he would no longer speak freely with me.

And surely the poor man looked mortified the next day, afraid that he had irrevocably offended me. I told him then that I had had it directly from our rector that knowledge is not itself evil, it is only the use to which one puts it that may imperil the soul. I said I was grateful for the insight into the state of our country’s highest councils and would be more grateful still to hear other such poems, for are not all His Majesty’s loyal subjects bound to strive to emulate their king? And so we made a jest of it, and as spring softened into summer, so we became more easy with each other.

Mr. Hadfield had ordered a box of cloth from London and there was great excitement when the parcel arrived, as there always is at the coming of goods from the city, with many in the village interested to see what manner of colour and figure might now be worn in town. Because the parcel arrived damp, having travelled the last of its journey in an open cart unprotected from rain, Mr. Hadfield asked Mr. Viccars to see to its drying, and so he contrived lines in the garth of our cottage and slung the fabrics out to air, thus giving everyone ample chance to look and comment. Jamie made a game of it, of course, running up and down between the flapping fabrics, pretending he was a knight at a joust.

Mr. Viccars was so well fixed with orders that I was surprised indeed when, just a few days after the London fabrics arrived, I returned from my work to find a dress of finespun wool lying folded on the pallet in my room. It was a golden green, the colour of sunlight-dappled leaves, of modest style, but well cut and flattering, its whisk and hands trimmed in Genoa lace. I’d never had so fine a thing – even for my handfast I’d worn the borrowed dress of a friend. And since Sam had died I’d been in the one shapeless smock of rough serge, Puritan black, innocent of any adornment. I expected to go on so, for neither my means nor my inclination had led me to look to bedecking myself. And yet I held the soft gown up to me and walked by the window, thrilled as a girl, trying to catch a glimpse of my reflection in the pane. It was in the glass I saw Mr. Viccars standing behind me, and I dropped the dress, embarrassed to be caught so immodestly preening. But he was smiling his big open smile, and he looked down deferentially when he grasped my mortified state.

‘Forgive me, but I thought of you directly I sighted that cloth, for the green is exactly the colour of your eyes.’

I felt my face flush, and my vexation at blushing just made my cheeks and throat burn all the hotter. ‘Good sir, you are kind, but I cannot accept this dress from you. You are here as my lodger, and glad I am to have such a one as you. But you must know that to be man and woman under one roof is a perilous matter. I fear that we approach too near to terms of friendship…’

‘I would we may,’ he interrupted quietly, his expression now serious and his eyes on mine. At that I blushed scarlet all over again and knew not how to answer him. His face also was rather flushed, and I wondered if he, too, was blushing. But then, as he took a step towards me, he staggered a little and had to fling a hand against the wall to steady himself. At this I felt a small surge of anger, thinking that he had been helping himself to the ale jar and preparing myself in case his behaviour began to resemble the grog-swilling oafs I had sometimes had to deal with since Sam died. But Mr. Viccars kept his hands to himself, raising them to his brow and rubbing at it, as if it pained him. ‘Have the dress in any wise,’ he said quietly. ‘For I mean only to thank you for keeping a comfortable house and welcoming a stranger.’

‘Sir, I thank you, but I cannot think it right,’ I said, folding the gown and holding it out to him.

‘Why do you not seek advice on the morrow when you are at the rectory?’ he said. ‘Surely if your pastor sees no harm in it, there may be found none?’

I saw some wisdom in what he proposed and assented to it. If not the rector – for I could not see opening my heart on such a matter to him – I knew that Mrs. Mompellion would know how to advise me. And there was still, I was surprised to discover, woman enough alive within me to want to wear that dress.

‘Will you not at least try it upon yourself? For a workman likes to know where he stands in the mastery of his craft, and if you learn on the morrow that you mayn’t accept this gift in all propriety, at least you will have rewarded my pains and gratified my pride of workmanship by letting me see how I have done.’

Did I do right, I wonder, in so readily agreeing to his suggestion? I stood there in the doorway, fingering the fine stuff, and my curiosity to have the dress upon my body overbore my sense of what was or was not fit to do. I waved Mr. Viccars down the stairs to await me and shrugged myself out of my rough tunic. For the first time in months, I noticed how dingy were the linens I wore beneath, blotched with sweat and stained by leaking milk. It seemed improper to put the new dress over these unclean things, so I slipped them off as well and stood for a moment, regarding my own body. Hard work and a lean winter had robbed me of the softness left behind after Tom’s birth. Sam had liked me fleshy. I wondered what Mr. Viccars liked. The thought stirred me, so that my skin flushed and my throat tightened. I gathered up the green dress. It slid softly over my bare flesh. My body felt alive as it hadn’t in a long time, and I knew quite well that only part of the reason was the feel of the dress. As I moved, the skirt swayed, and I felt an urge to move with it, to dance again like a girl.

Mr. Viccars had his back to me, warming his hands at the fire. When he heard my tread on the stair, he turned and caught his breath, and his face brightened in a smile of appreciation. I twirled, making the skirt swirl around me. He clapped his hands and then held them wide. ‘Mistress, I would make you a dozen such gowns to display your beauty!’ Then, the playful tone left his voice and it dropped, becoming husky. ‘I would you might think me worthy to provide for you in all matters.’ He crossed the room and placed his hands on my waist, drew me gently towards him, and kissed me. I will not say I know what would have happened then if his skin, when it brushed mine, had not been so hot that I pulled back.

‘But you are fevered!’ I exclaimed, reaching, as mothers will, to lay a hand on his forehead. Thus was a moment lost, for better or worse.

‘It is true,’ he said, releasing me and once again rubbing at his temples. ‘All this day I have felt a grudging of ague, and now it rises and my head pounds, and I do feel a most dreadful ache probing at my bones.’

‘Get you to your bed,’ I said gently. ‘I will give you a cooling draught to take up with you. We will speak again of these things on the morrow, when you are restored.’

I do not know how Mr. Viccars slept that night, but I rested ill, confused by a tumble of thoughts and reawakened feelings that were not entirely welcome to me. I lay a long time in the dark, listening to the babies breathe their slight, soft, animal breaths beside me. I closed my eyes and conjured the feel of Mr. Viccars’s hands landing gently on my waist and tightening their grip there. I was like one who forgets all day to eat until the scent from some other’s roasting pan reminds her she is ravenous. My hand reached in the darkness and closed around Tom’s tiny, budlike fist, and I realized that though I loved the touch of my children’s little hands, there was another kind of touch – hard and insistent – for which my body hungered.

In the morning, I rose before cock crow so as to accomplish my household chores before Mr. Viccars descended from his garret. I did not wish to encounter him until I had had more space to examine my desires. I left the children in their sleepy tangle, tiny Tom curled up like a nutmeat in its shell, Jamie’s slender little arms flung wide across the pallet. They both smelled so sweet, lying there in their night-warmth. Their heads, covered in their father’s fine, fair down, gleamed bright in the dimness. My heavy, dark hair could not have been more unlike their pale curls, but their small faces, insofar as you can discern such things in features so unformed, were said by everyone to favour my own looks more than their father’s. I put my face to their necks and breathed the yeasty scent of them. God warns us not to love any earthly thing above Himself, and yet He sets in a mother’s heart such a fierce passion for her babes that I do not comprehend how He can test us so.

Downstairs, I fanned the embers and relaid the fire and then went out to the well to draw the day’s water, setting a big kettle to heat and drawing a basinful to wash myself as soon as the ground-chill had gone from it. Drawing more, I scrubbed the gritstone flags, and while they dried I drew my shawl around me and took my broth and bread out into the brightening garth, watching the sky’s edge turn rosy and the mists rise from the two streams that bracket our hamlet. Our village has a fair prospect, and that morn the air was rich with summer’s loamy fragrance. It was a morning fit for the contemplation of new beginnings, and as I watched a whinchat trailing a worm to feed his young, I wondered if I, too, should look for a helper in the rearing of my boys.

Sam had left me the cottage and the sheepfold behind, but they had nicked his stowe the day they brought his body out of the mine. I told them that day that they need not wait to nick it again, for three weeks, six weeks, or nine, I could neither shore the fallen walls nor was I in purse to have another do it. Jonas Howe has the seam now, and being a good man, and a friend of Sam’s, he feels he has choused me, although why he should I know not, as it can hardly be a swindle when the law here time out of mind has made it plain that those who cannot pull a dish of lead from a mine within three nicks may not keep it. He said he would make miners of my boys alongside his own when they were of age. Though I thanked him for his promise, I was not sincere when I did so, for I firmly hoped not to see them in that rodent life, gnawing at rock, fearing flood and fire and crushing fall. But the tailoring trade was another gate’s business, and I would be pleased to have them learn it. Beside, George Viccars was a good man with a quick understanding. I enjoyed his company. Certainly, I had not shrunk from his touch. I had married Sam for far less cause. But then again, I was not fifteen anymore, and choices no longer had that same clear, bright edge to them.

When I’d broken my fast I searched the bushes for a brace of eggs for Mr. Viccars and another for Jamie. My fowl are unruly and never will lay in their roost. Then I returned inside to knead the dough for the morrow’s bread and covered it to rise in a bowl near to the fire. I decided to leave the remaining chores for the afternoon and returned upstairs to set Tom to my breast so that Jane Martin would find him with full belly when she arrived shortly to watch over him. As I hoped, he barely stirred as I lifted him, greeting me only with a single long stare before closing his eyes and commencing his contented suckling.

As a result of my early rising, I was at the rectory well before seven, and yet Elinor Mompellion was already in her garden, a pile of prunings rising high beside her. Unlike most ladies, Mrs. Mompellion did not scruple to toil with her hands. Especially she loved to work in her garden, and it was not uncommon to see her face as streaked with dirt as a charwoman’s from carelessly pushing back wisps of hair that loosened as she dug and weeded.

At five and twenty, Elinor Mompellion had the fragile beauty of a child. She was all pale and pearly, her hair a fine, fair nimbus around skin so sheer that you could see the veins pulsing at her temples. Even her eyes were pale, a white-washed blue like a winter sky. When I’d first met her, she reminded me of the blow-ball of a dandelion, so insubstantial that a breath might carry her away. But that was before I knew her. The frail body was paired with a sinewy mind, capable of violent enthusiasms and possessed of a driving energy to make and do. Sometimes, it seemed as if the wrong soul had been placed inside that slight body, for she pushed herself to her limits and beyond, and was often ill as a result. There was something in her that could not, or would not, see the distinctions that the world wished to make between weak and strong, between women and men, labourer and lord.

The garden was fragrant that morning with the sharp tang of lavender. It seemed that the colours and patterns of the plantings changed by the day under her skilled hands, the misty blues of forget-me-nots ceding to the rich midnight larkspurs, then easing to the soft pinks of the mallow flowers. Under every window she had set bowpots of jessamine and gilly flowers so that the scents wafted sweetly through the house. Mrs. Mompellion called the garden her little Eden, and I believe God did not mislike her claim, for all manner of flowers flourished there, far beyond what are commonly expected to grow and thrive through the hard winters on this mountainside.

That morning I found her on her knees, deadheading the daisies. ‘Good morning, Anna,’ she said as she saw me. ‘Did you know that the tea made of this unassuming little flower serves to cool a fever? As a mother you’d do well to add some herb lore to your store of knowledge, for you never can be sure when your children’s well-being might depend upon it.’ Mrs. Mompellion never let a minute pass without trying to better me, and for the most part I was a willing pupil. When she had discovered that I hungered to learn, she commenced to shovel knowledge my way as vigorously as she spaded the cowpats into her beloved flower beds.

I was ready to take what she gave. I had always loved high language. My chief joy as a child had been to go to church, not because I was uncommonly good, but because I longed to listen to the fine words of the prayers. Lamb of God, Man of Sorrows, Word made Flesh. I would lose myself in the cadence of the phrases. Even as our pastor then, the old Puritan Stanley, denounced the litanies of the saints and the idolatrous prayers of the Papists for Mary, I clung to the words he decried. Lily of the Valley, Mystic Rose, Star of the Sea. Behold the Handmaid of the Lord. Let it be done unto me according to Thy Word. Once I realized that I could memorize bright snatches of the liturgy, I set myself to do it every Sunday, adding to my harvest like a farmer building his stook. Sometimes, if I could escape from under my stepmother’s eye, I would linger in the churchyard, trying to copy the forms of the letters inscribed upon the tombstones. When I knew the names of the dead, I could match the shapes engraved there with the sounds I reasoned they must stand for. I used a sharpened stick for my pen and a patch of smoothed earth as my tablet.

Once, my father, carting a load of firewood to the rectory, came upon me so. I started when I saw him, so that the stick snapped in my hand and drove a splinter into my palm. Josiah Bont was a man of few words, and those mostly curses. I did not expect him to understand my strong longing towards what to him must surely seem a useless skill. I have said that he loved a pot. I should add that the pot did not love him, and made of him a sour and menacing creature. I cringed from him that day, waiting for his fist to fall. He was a big man, ever quick with a blow – and often for less cause. And yet he did not strike me for shirking my chores, but only looked down at the letters I had attempted, rubbed a grimy fist across his stubbled chin, and walked on.

Later, when several of the other village children taunted me about it, I learned that my father had actually been crowing about me at the Miner’s Tavern that day, saying that he wished he had the means to have me schooled. It was an easy boast, one he would never have to make good upon, for there were no schools, even for boys, in villages such as ours. But the news of this warmed me and made the children’s teasing a small matter, for I had never had a word of praise from my father’s lips, and to learn that he thought me clever made me begin to think that perhaps I might be so. After this, I became more open and would go about my work muttering snatches of Psalms or sentences from the Sunday sermon, meaning purely to pleasure my ear but earning an undeserved name for religious devotion. It was just such a reputation that led to my recommendation for employment at the rectory, and thus opened the door to the real learning that I craved.

Within a year of her coming, Elinor Mompellion had taught me my letters so well that, though my hand remained unlovely, I could read with only some small difficulties from almost any volume in her library. She would come by my cottage most afternoons, while Tom slept, and set me a lesson to work upon while she went on the remainder of her pastoral visits. She would call in again on her way home to see how I had managed and help me over any hurdles. Often, I would stop in the midst of our lessons and laugh for the sheer joy of it. And she would smile with me, for as I loved to learn, so she loved to teach.

Sometimes, I would feel some guilt in my pleasure, for I believed I gained all this attention because of her failure to conceive a child. When she and Michael Mompellion arrived here, so young and newly wedded, the entire village watched and waited. Months passed, and then seasons, but Mrs. Mompellion’s waist stayed slim as a girl’s. And we all – the whole parish – benefited from her barrenness, as she mothered the children who weren’t mothered enough in their own crowded crofts, took interest in promising youths who lacked preferment, counselled the troubled, and visited the sick, making herself indispensable in any number of ways to all kinds and classes of people.

But of her herb knowledge I wanted none; it is one thing for a pastor’s wife to have such learning and another thing again for a widow woman of my sort. I knew how easy it is for widow to be turned witch in the common mind, and the first cause generally is that she meddles somehow in medicinals. We had had a witch scare in the village when I was but a girl, and the one who had stood accused, Mem Gowdie, was the cunning woman to whom all looked for remedies and poultices and help with confinements. It had been a cruel year of scant harvest, and many women miscarried. When one strange pair of twins was stillborn, fused together at the breastbone, many had begun muttering of Devilment, and their eyes turned to Widow Gowdie, clamouring upon her as a witch. Mr. Stanley took it upon himself to test the accusations, taking Mem Gowdie with him alone into a field and spending many hours there, dealing with her solemnly. I do not know by what tests he tried her, but after, he declared that he conceived her entirely innocent as to that evil and upbraided the men and women who had accused her. But he also had harsh words for Mem, saying she defied God’s will in telling folk that they could prevent illness with her teas and sachets and simples. Mr. Stanley believed that sickness was sent by God to test and chastise those souls He would save. If we sought to evade such, we would miss the lessons God willed us to learn, at the cost of worse torments after our death.

Though none now dared whisper witch against old Mem, there were some who still looked aslant at her young niece, Anys, who lived with her and assisted at confinements and in the growing and drying and mixing of her brews. My stepmother was one of these. Aphra harboured a wealth of superstitions in her simple mind and was ever ready to believe in sky-signs or charms or philtres. She approached Anys with a mixture of fear and awe, and perhaps some envy. I had been at my father’s croft when Anys had come with a salve for the sticky-eye, which all the young ones were catching at the time. I had been surprised to see Aphra stealthily hiding a scissors, spread full open like a cross, under a bit of blanket upon the chair upon which she invited Anys to sit. I chided her for it, after Anys was gone. But she waved off my disapproval, showing me then the hag-stone she’d draped over her children’s pallet and the phial of salt she’d tucked into the doorpost.

‘Say what you will, Anna. That girl walks with too much pride in her step for a poor orphan,’ my stepmother opined. ‘She carries herself like one who knows summat more than we do.’ Well, I said, and so she did. Was she not well skilled in physick, and weren’t we all the better off on account of it? Had Anys not just brought us a salve for the sticky-eye that would soothe the children’s pains far quicker than Aphra or I had means to do it? Aphra simply made a face.

‘You’ve seen the way the men, old and young, sniff around her as if she were a bitch in heat. You can call it physick all you like, but I think she’s brewing up more than cordials in that croft of her’n.’ I pointed out that when a young woman was as fine figured and fair of face as Anys, men hardly had to be bewitched into interest in her, especially if that young woman had no father or brothers to remind them where to keep their eyes. Aphra scowled as I said this, and I felt I probed near the place where her ill will to Anys resided.

Aphra, neither handsome nor quick-witted, had settled for marriage with my dissolute father when she had passed six and twenty years with no better man making her an offer. They did well enough together since neither expected much. Aphra enjoyed a pot almost as much as my father, and the two of them spent half their lives in drunken rutting. But I think that in her heart Aphra had never ceased to pine for the kind of power a woman like Anys might wield. How else to account for her ill thoughts towards one who did only good by her and her children? It was true enough that Anys was refractory and cared not for the conventions of this small and watchful town, yet there were others less upright who did not draw such disapproval as she. Aphra’s superstitious mutterings found many willing ears amongst the villagers, and sometimes I worried for Anys on account of it.

I let Mrs. Mompellion wax on about the efficacy of rue and chamomile and busied myself rooting out the thistleweeds, as it is labour that requires hard pulling and can tend to make Mrs. Mompellion very faint if she stoops over it too long. Presently, I went to the kitchen to begin the day’s real labour and in the scrubbing of deal and sanding of pewter consumed the morning hours. There are some who imagine that the work of a housemaid is the dullest of drudgery, but I have never found it so. At the rectory and at the Bradfords’ great Hall, I found much enjoyment in the tending of fine things. When you have been raised in a bare croft, eating with wooden spoons from crude platters, there are a hundred small and subtle pleasures to be garnered in the smooth slipperiness of a fine porcelain cup under your hands in a tub of soapsuds or the leathery scent of a book as you work the beeswax into its binding. As well, these simple tasks engaged only the hands and left the mind free to wander unfettered down all manner of interesting pathways. Sometimes, as I polished the Mompellions’ damascene chest, I would study its delicate inlays and wonder about the faraway craftsman who had fashioned it, trying to imagine the manner of his life, under a hot sun and a strange God. Mr. Viccars had a rich and lovely fabric that he called damask, and I fell to wondering if that bolt of cloth had stood in the same bazaar as the chest and made the same long journey from desert to this damp mountainside. Thinking of Mr. Viccars broke my reverie and reminded me that I had not raised the problem of the dress with Mrs. Mompellion. But then I realized it was nigh to noon and Tom would be fair-clemmed and mewling for his milk. So I left the rectory in haste, thinking that the matter of the dress and its propriety could be raised with Mrs. Mompellion at some later time.

But that later time never came. For when I arrived at the cottage, the quiet inside was of the old kind in the days before Mr. Viccars joined our household. There was not laughter or merry shouting from within, and indeed, in the kitchen I found only a sullen Jane Martin distracting Tom with a finger of arrowroot and water, while Jamie, all subdued, played alone by the hearth, making towers from the bavins and thus strewing bits of broken kindling everywhere. Mr. Viccars’s sewing corner was as I’d left it that morning, with the threads and patterns piled neat and untouched from the night before. The eggs I’d left for him lay still in their whisket. Tom, seeing me, squirmed in Jane Martin’s arms and opened his wide, gummy mouth like a baby bird. I reached for him and set him to nurse before I enquired about Mr. Viccars.

‘Indeed, I have not seen him. I believed him to be gone out early to the Hadfields’,’ she said.

‘But his breakfast is uneaten,’ I replied. Jane Martin shrugged. She had made it plain by her manner that she misliked the presence of a male lodger in the house, although since Rector Mompellion had sent us Mr. Viccars she had had to hold her peace about it.

‘He a bed, Mummy,’ said Jamie forlornly. ‘I goed up to find him but he yelled me, “Go ’way.”’

Mr. Viccars must be ill indeed, I reasoned. Anxious as I was to attend to him, I had to complete Tom’s feeding first. Once he was satisfied, I drew a pitcher of fresh water, cut a slice of bread, and climbed to Mr. Viccars’s garret. I could hear the moans as soon as I set a foot on the attic ladder. Alarmed, I failed to knock, simply opening the hatch into the low-ceilinged space.

I almost dropped the pitcher in my shock. The fair young face of the evening before was gone from the pallet in front of me. George Viccars lay with his head pushed to the side by a lump the size of a newborn piglet, a great, shiny, yellow-purple knob of pulsing flesh. His face, half turned away from me because of the excrescence, was flushed scarlet, or rather, blotched, with shapes like rings of rose petals blooming under his skin. His blond hair was a dark, wet mess upon his head, and his pillow was drenched with sweat. There was a sweet, pungent smell in the garret. A smell like rotting apples.

‘Please, water,’ he whispered. I held the cup to his parched mouth, and he drank greedily, his face distorted from the grief of the effort. He paused from his drinking only as a spasm of shivering and sneezing racked his body. I poured, and poured again until the pitcher was drained. ‘Thank you,’ he gasped. ‘And now I pray you be gone from here lest this foul contagion touch you.’

‘Nay,’ I said, ‘I must see you comfortable.’

‘Mistress, none may do that now except the priest. Pray fetch Mompellion, if he will dare to come to me.’

‘Say not so!’ I scolded him. ‘This fever will break, and you will be well enough presently.’

‘Nay, Mistress, I know the signs of this wretched illness. Just get you gone from here, for the love of your babes.’

I did go at that, but only to my own room to fetch my blanket and pillow – the one to warm his shivers and the other to replace the drenched thing beneath his horrible head. He moaned as I reentered the garret. As I attempted to lift him to place the pillow, he cried out piteously, for the pain from that massive boil was intense. Then the purple thing burst all of a sudden open, slitting like a pea pod and issuing forth creamy pus all spotted through with shreds of dead flesh. The sickly sweet smell of apples was gone, replaced by a stench of week-old fish. I gagged as I made haste to swab the mess from the poor man’s face and shoulder and stanch his seeping wound.

‘For the love of God, Anna – he was straining his hoarse throat, his voice breaking like a boy, summoning I don’t know what strength to speak above a whisper – ‘Get thee gone from here! Thou can’t help me! Look to thyself!’

I feared that this agitation would kill him in his weakened state, and so I picked up the ruined bedding and left him. Downstairs, two horrified faces greeted me, Jamie’s wide-eyed with incomprehension, and Jane’s pale with knowing dread. She had already shed her pinafore in preparation to leave us for the day, and her hand was upon the door bar as I appeared. ‘I pray you, stay with the children while I fetch the rector, for I fear Mr. Viccars’s state is grave,’ I said. At that, she wrung her hands, and I could see that her girlish heart was at war with her Puritan spine. I didn’t wait to see who would win the battle but simply swept by her, dumping the bedding in the dooryard as I went.

I was running, my eyes down and fixed on the path, so I did not see the rector astride Anteros, on his way from an errand in nearby Hathersage. But he saw me, turned and wheeled that great horse, and cantered to my side.

‘Good heavens, Anna, whatever is amiss?’ he cried, sliding from the saddle and offering a hand to steady me as I gasped to catch my breath. Through ragged gulps, I conveyed the gravity of Mr. Viccars’s condition. ‘Indeed, I am sorry for it,’ the rector said, his face clouded with concern. Without wasting any more words, he handed me up onto the horse and remounted.

It is so vivid to me, the man he was that day. I can recall how naturally he took charge, calming me and then poor Mr. Viccars; how he stayed tirelessly at his bedside all through that afternoon and then again the next, fighting first for the man’s body and then, when that cause was clearly lost, for his soul. Mr. Viccars muttered and raved, ranted, cursed, and cried out in pain. Much of what he said was incomprehensible. But from time to time he would cease tossing on the pallet and open his eyes wide, rasping ‘Burn it all! Burn it all! For the love of God, burn it!’ By the second night, he had ceased his thrashing and simply lay staring, locked in a kind of silent struggle. His mouth was all crusted with sordes, and hourly I would dribble a little water on his lips and wipe them; he would look at me, his brow creasing with effort as he tried to express his thanks. As the night wore on, it was clear that he was failing, and Mr. Mompellion would not leave him, even when, towards morning, Mr. Viccars passed into a fitful kind of sleep, his breath shallow and uneven. The light through the attic window was violet and the larks were singing. I like to think that, somewhere through his delirium, the sweet sound might have brought him some small measure of relief.

He died clutching the bedsheet. Gently, I untangled each hand, straightening his long, limp fingers. They were beautiful hands, soft save for the one callused place toughened by a lifetime of needle pricks. Remembering the deft way they’d moved in the fire glow, the tears spilled from my eyes. I told myself I was crying for the waste of it; that those fingers that had acquired so much skill would never fashion another lovely thing. In truth, I think I was crying for a different kind of waste; wondering why I had waited until so near this death to feel the touch of those hands.

I folded them on George Viccars’s breast, and Mr. Mompellion laid his own hand atop them, offering a final prayer. I remember being struck then by how much larger the rector’s hand was – the hard hand of a labouring man rather than the limp, white paw of a priest. I could not think why it should be so, for he came, as I gathered, from a family of clergy and had but recently been at his books in Cambridge. There was not much between Mr. Mompellion and Mr. Viccars in age, for the reverend was but eight and twenty. And yet his young man’s face, if you looked at it closely, was scored with furrows at the brow and starbursts of crows’ feet beside the eyes – the marks of a mobile face that has frowned much in contemplation and laughed much in company. I have said that it could seem a plain face, but I think that what I mean to say is that it was his voice, and not his face, that you noticed. Once he began to speak, the sound of it was so compelling that you focused all your thoughts upon the words, and not upon the man who uttered them. It was a voice full of light and dark. Light not only as it glimmers, but also as it glares. Dark not only as it brings cold and fear, but also as it gives rest and shade.