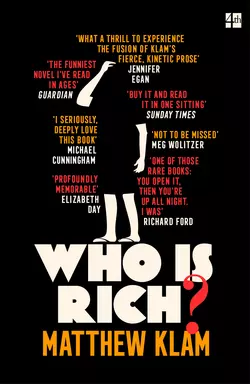

Who is Rich?

Matthew Klam

‘Who is Rich? Is a tantalizing novel – acute and smart and stark, but mostly it’s unrelentingly funny about a large number of very inappropriate things. It’s one of those rare books: you open it, then you’re up all night. I was‘ Richard FordEvery summer, a once-sort-of famous cartoonist named Rich Fischer leaves his wife and two kids behind to teach a class at a week-long arts conference in a charming New England beachside town. It’s a place where drum circles happen on the beach at midnight, clothing optional. Rich finds himself worrying about his family’s nights without him, his back taxes, his stuttering career and his own very real desire for love and human contact. One of the attendees this year is a forty-one-year-old painting student named Amy O’Donnell. Amy is a mother of three, unhappily married to a brutish Wall Street titan who commutes to work via helicopter. Rich and Amy met at the conference a year ago, shared a moment of passion, then spent the winter exchanging inappropriate texts and emails and counting the days until they could see each other again.Now they’re back.Who Is Rich? is a warped and exhilarating tale of love and lust, a study in midlife alienation, erotic pleasure, envy, and bitterness in the new gilded age that goes far beyond humour and satire to address deeper questions: of family, monogamy, the intoxicating beauty of children and the challenging interdependence of two soulful, sensitive creatures in a confusing domestic alliance.

Copyright (#ulink_09b5bc97-4cd3-586d-9982-54c68e580bcf)

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk (http://www.4thEstate.co.uk)

First published in the United States by Random House in 2017

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2018

Copyright © 2017 by Matthew Klam

Drawings copyright © 2017 by John S. Cuneo

Cover design by Jack Smyth

“Sea-Level Elegy” was first published in Stag’s Leap (Jonathan Cape 4th October, 2012). Reprinted by permission of Jonathan Cape and Aragi Inc.

Matthew Klam asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008282516

Ebook Edition © March 2018 ISBN: 9780008282523

Version: 2018-03-23

Dedication (#ulink_99044503-ce9b-5ef5-ac6c-3193c730bb0c)

FOR DANIEL MENAKER

Epigraph (#ulink_22e3c0d7-0e5e-5b2a-9bb3-708673dd96cf)

Once, each summer, I howl,

and draw myself back, out of there, where

desire and joy, where ignorance, where

touch and the ideal, where unwilled yet willful

blindness – once a year, I have mercy,

I let myself go down where I have lived, and then,

hand over hand, I pull myself back up.

“Sea-Level Elegy”, Sharon Olds

Contents

Cover (#u513bb8af-583b-525e-bef6-d40179a7a8c1)

Title Page (#u87323787-9b9f-5355-8f6a-b63cd48ff547)

Copyright (#u15dc95c6-1a87-5e17-8aa5-086bc734f78b)

Dedication (#u87a6db28-27e5-5d1d-b92f-fdfb2c976248)

Epigraph (#u9b4c954c-b8fc-5627-ae95-e017a5377b5f)

Chapter One (#u3d0d0b05-556b-59e7-bd6e-d3bc3ab4ea47)

Chapter Two (#uff233ca1-733f-5312-bb87-270bf466210c)

Chapter Three (#uc68ed9e4-2769-56f9-bd9f-301e5f170c54)

Chapter Four (#u4e095c9a-c9a1-5069-90f9-dd34579dbe58)

Chapter Five (#u037911ed-6388-5e1b-9c48-70b6d6bb0c69)

Chapter Six (#u3f248615-cdbb-5079-8237-0e97f2829bcb)

Chapter Seven (#u41c9aea3-e82d-5c43-ac1a-9dae38b3b743)

Chapter Eight (#u3dbcc776-20f1-5c60-b54d-ace7ce47d58d)

Chapter Nine (#u0f66e65f-eb8a-537d-842c-0d6fdd4a7812)

Chapter Ten (#u14fd6207-ce8c-5861-878e-e154e5af40d1)

Chapter Eleven (#ubd32e260-db3c-5ceb-92bb-5f38f6701aa4)

Chapter Twelve (#uaa85dcfe-e0e4-5c64-a926-3cd329aa8140)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By Matthew Klam (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

ONE (#ulink_70aa3847-7945-5c4f-80f4-4b6107b6efab)

Fog blew in Saturday morning. I sat under a big white tent and drank some coffee while my chair sank into the lawn. I talked to a kid with a heavy beard in a mangled straw hat who last year for some reason we started calling Swaggamuffin.

A girl wearing a name tag passed out rosters to faculty. A guy walking behind her handed me an info packet. I sat there eating toast, looking at my notes. Other people were out there too, chatting and smoking. I said hello to a dozen familiar faces from over the years and drank several more cups. The fog burned off. A lawnmower buzzed. The sky was a flawless aquamarine blue.

I’d written a three-part lecture, on drawing techniques, brainstorming, and plotting, and also found some handouts with exercises from last year or the year before that. We supplied them with pencils, erasers, pens, nibs, brushes, and paper—100-pound acid-free Bristol board for comic applications—and a little plastic thing called the Ames Lettering Guide, which I still had no idea how to use.

We were gathered on the campus of a college you’ve never heard of, at the end of a sandy, hook-shaped peninsula, bound by the Atlantic and scenic as hell. It was my fifth straight summer running a workshop at an annual summer arts conference, and once again my class was full. The conference had begun fifteen years before as a one-day poetry festival and had grown every year in size and popularity, although the college itself had not fared as well. Over time, pieces of it had been boarded up to save money until the entire school was abandoned, then reopened in a limited capacity as a satellite of the nearest state U. The college had kept its name, which was the name of the town, which had been named after the people who’d been here since the beginning of time, who’d made peace with the English settlers, teaching them to fish and hunt, helping them slaughter neighboring tribes, before they too were wiped out by disease or dragged off and sold into slavery.

Nada Klein, with her long French braid and dark wolfish eyes, walked through the tent with her shawl dragging on the ground. She beat cancer every year, and showed up late to her own slide talks, and was widely mocked and imitated. Larry Burris was back, too. He skipped his meds one year and wore a jester’s cap to class and lit his own notes on fire, and had to spend the night in a hospital. He stood beside me now, beneath the tent flap, patiently signing a copy of his book, and handed it back to a woman who hugged him. On the faculty were many friends I’d come to know over the years as intellects, historians, wordsmiths, talented performers, storytellers with big fake teeth, addicts, drunkards, perverts, world-famous womanizers, sufferers of gout, maniacs, liars—embittered, delusional, accomplished, scared of spiders, unable to swim, loveless, and cruel. I noticed Barney Angerman, who’d won the Pulitzer for drama the year I was born, and Tabitha Portenlee, who’d written an acclaimed incest memoir; she was helping Barney through the breakfast line as he gripped her arm. This past winter the conference director had asked me to name another cartoonist I could vouch for to teach a second comics workshop, but I didn’t answer him. I worried, because of the way my career had gone, that I’d be hiring my replacement.

A little before nine I went to the Fine Arts building. Hurrying down a long hall, past students and teachers, I looked for my studio. There were classes in the annex now, landscape photography, felt making, fresco on plaster, whatever that was.

When I got there they were pulling out their stuff, giving each other the once-over. I flipped through my notes. A woman who lived in town was complaining about beach traffic. A skinny kid stared at me, wearing a sundress, mascara, and a pearl choker. A young Asian woman stared at him, clutching her pencil case. A young man in a white polo, a craggy-looking old guy, and a girl with button eyes and tiny feet were talking with affection about their dogs.

I opened the info packet and read the bios of the other teachers and guest speakers printed in the conference pamphlet. There were different levels of us, unknown nobodies and one-hit has-beens, midlist somebodies and legitimate stars. As I read, I could hear my own labored breathing. I tried to slow it down but felt worse, graying as the blood left my brain. I read my course description from who knows when.

MATTICOOK COLLEGE SUMMER ARTS CONFERENCE

CARTOONING STUDIO: SEMIAUTOBIOGRAPHICAL COMICS

with Rich Fischer

July 18–21. Tuition: $1,500. Ages 18+. For-credit option:

$1,900.

Are you ready to take your cartooning to the next level? Start from scratch, or bring your own comic in progress to our 4-day summer intensive, and we’ll help you do just that …

A murmuring of bodies came from the hall. Fans turned slowly over us. An old galvanized ventilation system snaked around the ceiling. A thin woman stepped cautiously into the room, walked out, then came back in. Wild brown hair, sharp elbows, bony wrists, redness around her mouth, raw, wounded-looking lips, a long skirt, moccasins. Was she the kind of person to take time out of her busy life to make a fictionalized comic about herself? Apparently.

I moved across the studio, faking a slight limp in order to give my movements in flip-flops and canvas shorts a more tweedy gravitas, and adjusted the blinds. In this way I became the parent, the benign elder, with knowledge and some intangible quality of goodness that would allow my students to project onto me the power to contain their aspirations. I’d be the vessel, I’d hold their dreams, whatever. When it was quiet, I asked them to go around the room and introduce themselves.

I wasn’t a teacher. I didn’t belong here. I’d ditched my family and driven nine hours up the East Coast in Friday summer highway traffic so I could show off in front of strangers, most of whom had no talent, some of whom weren’t even nice, while I got paid almost nothing. They’d blown their hard-earned money to come to this beautiful place not to swim or sail but to sit in a room all day writing and drawing their guts out, telling themselves it was a dream come true.

I’d driven up here for the first time the summer after my only book came out. This conference was one of many good things that had come to me in those days. It was maybe the only thing left. Every time I pulled into town and saw the blinking neon lobsters, the bowling alley, the giant plastic 3-D roadside sandwich, it gave me a big feeling, reminding me of a once-limitless future.

Melanie Lenzner taught high school art in New Hampshire and went on too long, acting like it was her class, not mine. Helen Li, a biomolecular engineering student, said she didn’t want to start med school in the fall. Nick, the trans kid, said his father had thrown him out of the house and that he—or she—lived in her car. Carol, faded red hair cut short and stalky, looked alarmed, and asked how long he or she’d been homeless. George had gone into the army at eighteen, had fought in Vietnam, lost his wife twenty years ago, and had a daughter named Sonya who lived in Buffalo. Sang-Keun Kim, mustache, ponytail; I thought I’d seen him back in the eighties in porno movies. Frances, a granny in a white cardigan, so happy to be here. Vishnu wanted us to know that he’d taken workshops from cartoonists more famous than me. Rebecca, the skinny one, worked in Hartford as a midwife. Behind the sinks, a teenage girl wearing a wool hat, deerskin slippers, and flannel pajama pants looked up through a face screened in acne. I asked her to move closer. She said no. Her name was Rachel.

I passed around a ream of eleven by seventeen and asked everybody to take some.

I hadn’t published anything in six years. I worked as an illustrator now, at an esteemed magazine of politics and culture, a venerated institution of American journalism and the second- or third-oldest magazine in the country. Illustration is to cartooning as prison sodomy is to pansexual orgy. Not the same thing at all. Anyway, you might’ve seen my magazine work but didn’t know it—unless you happened to be scanning for names with a microscope. Some watered-down version, muted to satisfy commercial demands.

I’d been so full of promise, so amazed to have graduated from the backwater of fanzines and college newspapers to mainstream publishing. I had an appointment with destiny, I’d barely started, then I blinked and it was over. Nobody writing to beg for a blurb, no more mysterious checks arriving in the mail, no agent’s letterhead clipped to the check, no more calls from my publisher, not even to say go fuck yourself. What I missed most of all, had lost or forgotten, was the making of comics, triangulating the pain of existence through these bouts of belligerence, shame, suspicion, and euphoria, writerly noodlings and decipherable images organized into an all-encompassing environment. No more bragging, no more swagger, no more tasteless personal revelations. Cartoonists still made comics, and I hated them to the core of my filthy soul, and prayed for the return of 1996, when everything that would happen was about to happen, when I’d try to imagine how far I’d go.

If you’ve experienced precocious success, you know it’s rare. At first it seems like there must be some mistake, but you get used to it in a hurry; you’re sure it’ll always be this way. You travel, and meet famous cartoonists; they praise you, you chat like old friends and get to know them personally, you get sick of their whining and quickly lose respect for anyone on earth who struggles or complains. You come to expect fan mail, strangers popping up to kiss your ass, a certain deference or tone of voice. You start to think that anyone making comics who is without a national reputation, or miserable or obscure and lacking attention from jerkoffs in Hollywood, is a fucking moron.

I wrote on the board, Plumber, Hitler, moneybags,

“Let’s just take a couple minutes here—”

hayseed, hottie, hobbit,

“—to sketch these—”

lunch lady, Nabokov, beer wench,

“—keep the pencil moving—”

Sasquatch, sous-chef, snowman.

Then I walked around, trying not to look accusingly or even curiously at anyone, offering praise, encouraging spontaneity, saying positive stuff.

“Love it” … “Yes!” … “Lusty!” … “Good!”

The whole idea of this doodling was to lower the anxiety level in the room, to lighten the mood, to give them a feeling of poise and excitement, to discover in any character the autonomous core—

“Maybe another minute to wind up the one you’re on—”

—to raise the body temp and get the molecules bubbling. Then I went to the board and drew a snowman with a grin made of coal, and an indent where the nose should be, and this huge honking carrot, slightly bent, sticking out below the equator, you know where. Underneath the snowman I wrote, “Hungry?”

They laughed.

“Humor arises from the surprising juxtaposition of text and image.”

I drew a rabbit with a worried face, staring at the carrot. Then I erased the rabbit and put the carrot back where it belonged. I drew Satan in an overcoat, with a scarf around his neck, leaning on the snowman, complaining on the phone that the thermostat was broken. Then I got rid of Satan and drew a second snowman saying to the first, “Why does everything smell like carrots?”

“When you look at a comic, do you read the words first? Or look at the drawing?” We went around the room and shared our thoughts.

Then I broke them into groups, and for the next twenty minutes they made a racket, shouting, telling tales, arms flapping. They exchanged ideas, offered feedback and helpful insights, discussed, dissected, and ripped each other to shreds. In an email I’d sent out a month earlier, I’d asked them to bring along notes, a script, and some art, exhorting them to bravely mine their personal experiences for therapeutic and artistic gains, in order to come up with the one important story they’d develop this week.

Rebecca had in mind a moment inside an ambulance, her younger self in a paramedic’s uniform, leaning heavily over an old man, working to restart his heart, failing to, panic setting in. Sarah wanted to do something light and fun about her job in a bookstore. Brandon, in the white polo, made notes on his first gay pride weekend, bleaching his hair, snorting amyl nitrate, realizing, in the end, If you’ve seen one drag queen, you’ve seen ten thousand. They had four days to turn their thumbnails into finished pencil drawings, which they’d then ink and letter, scan and reproduce, and present to the world by Tuesday afternoon, in time for open studio.

I asked if anyone needed help. Mel fumbled with her pencil sharpener. I heard crickets chirping in Sarah’s empty head. Then I walked to the back of the room and looked at the floor. I heard pencils and paper, the steady breathing of humans at work. I stood behind the printing press, my hands on the wheel, like a sea captain trying to get on course.

TWO (#ulink_b22c97fc-8dec-5949-b550-e278f09499af)

By the time we took a break, other classes had also made their way outside to the picnic tables in the courtyard. A breeze as light as champagne bubbles swept over us from the bay. Sailboats dotted its sparkling waters. I felt relieved. I’d been nervous before class, and almost puked at breakfast. That first lecture always unhinged me, but I’d gotten through it.

But there was something else not right, and it took me a second to figure out what it was: Angel Solito, walking out of Fine Arts, squinting into the sun, coming toward me. He wore a navy blue hooded sweatshirt with long white strings. His arms hung down at his sides, and he wore eyeglasses. I said something, and he reached out a hand. His face was bumpy, as if a rash was trying to come through from underneath, and his hair had been slept on or pushed up into a ridge.

I couldn’t tell if he had any clue who I was, but I knew an editor of a British anthology who knew him. I said her name, like I didn’t care either way, and sternly congratulated him on his book.

“Uh-huh.”

He was the cartoonist who Carl, the director, had hired. Solito was young enough to be my son, if I’d had a son at fourteen, and on closer inspection the whites of his eyes were laced with red threads and his head tipped forward as if he had horns. Maybe he’d been heading to the big black plastic coffee urn on the picnic table behind me and I’d gotten in his way. Maybe he didn’t care, and just needed to vent, and would’ve talked this way to anybody. He shook his head and said, “Man, it’s been crazy,” and told me how exhausted he was, how he ran out of money two days ago and was waiting for a check from his publisher. As soon as the conference ended, he’d be hitting the road again.

“The book rolls out overseas, in Sweden and Denmark—”

At some point I realized he was confiding, I was being confided in, and I guess I appreciated that.

“—then the big rollout in Europe, at the end of the summer, beginning of fall—”

Chewing his lower lip, blinking at me, talking about some French fellowship, oblivious, harassed, as if French people had been calling all night and he hated to disappoint them, as a woman appeared at his side, with flyaway hair and skin so fair she was glowing, hugging his book to her chest.

“I’m so tired, man, I haven’t done any work in, like, months—”

As another young woman walked past us in pigtails, then stopped short when she realized it was him.

“—new idea for a book but I need to get into a quiet place, and hopefully kind of erupt—”

“Sure, of course.”

“You’ve been living the life for, like, ten years!” he said, taking a step toward the picnic table and his waiting fans. “You gotta tell me what it’s like. That’s why we gotta hang out!”

“Absolutely!” Fuck you.

He gave me a tired wave, a polite smile, almost sad, and I gave him a reassuring nod.

Tell you what it’s like, Angel. I sold ten thousand books in the last six years. He sold a hundred thousand copies in hardback in three months and foreign rights in thirty-eight countries. That’s, like, a million bucks in royalties. The woman in pigtails hesitated, but the blond one had her book ready and jumped.

I’d seen his work somewhere, maybe I saw an excerpt in some anthology, or maybe his publisher sent me a galley, or I might’ve seen it in a bookstore, in a stack on a table in front, and stood over it for however many hours it took to read the thing from start to finish, before stumbling back out into daylight, shivering and mumbling to myself, groping my way out the door.

Ran out of money. That fucker!

Angel Solito traveled from Guatemala to California, mostly on foot, mostly alone, eleven years old, walked a continent to find his parents, and finally did but never found the American dream. His story was rendered in clear bold lines, with faces delicately hatched, with big heads and a ferocious expressiveness. Reviews of his work had been universally frothy. In the days after I read it I had strange moments, traveling to some breathy place, almost happy, imagining that it was my book, my story, that I’d walked three thousand miles to find my parents, four and a half feet tall, eighty pounds, and alone.

He stood by the picnic table as more bodies surrounded him. He had caramel skin and shiny black hair. I felt the thrill of being him, like they were digging me, thanking me. I’d dreamed of the big time, and here it was, so beautiful, so real! Then I remembered that I didn’t get robbed by soldiers and chased by wolves. I didn’t crawl across the Sonoran Desert. Where I came from, eleven-year-olds could barely make their own beds.

I grew up in a middle-class suburb with good public schools an hour north of the G.W. Bridge, under a stand of white pine trees in an old house with wavy wooden floors and a loose banister. Walking thousands of miles to find my family would’ve been unnecessary. My brother lived across the hall. My father sold life insurance and other tax-dodging instruments from a skyscraper in New York City. My mom taught music to fourth, fifth, and sixth graders, in an attempt to make up for her own artistic failures. We lacked for nothing in that house except talent.

Back in the studio, a dozen people sat bowed, bent over their desks—doing what? Trying to pump life into a poorly realized, made-up world. Brandon didn’t know where to put his word balloons, and Rebecca needed a beveled edge, and Sang-Keun couldn’t figure out how to draw a cowboy hat.

“It’s round but curved,” I said, leaning over his shoulder. “Like a Pringle potato chip. A disk intersecting an ovoid.”

What did he see as my hand flew across the page? Several cowboy hats, spilling out of a pencil. Did he notice how each one was unique and expressive, reflecting the life of its owner? Did he note the skill or understand how hard I worked to make something difficult look effortless?

He touched the collar of his T-shirt, staring at the drawing as I moved to the next desk. He didn’t know anything. He didn’t care. I showed Sarah how to turn on the light box, and walked to the sinks and looked out the window, and tried my best to stay out of the way as a new generation of artists pounded at the gates of American graphic literature.

THREE (#ulink_cb36ea70-bc78-53fe-8d24-c9b823f50c11)

After class I cut across the lawn with a girl who wore cat-eye glasses and had small, pointy teeth, and a man with clay dust all over him, whacking it off his clothes, and Vishnu, who kept bumping into me.

“Professor,” he said, “in an interview you said male cartoonists are derivative whereas women are all original. Isn’t that kind of sexist?”

“I think I said guys have to shake off Batman comics. Women don’t have that as much.”

“Did you ever play Five-Card Nancy or stay up all night to do a twenty-four-hour comic?”

“No.”

“Why not?” He gave me a canny look, one cartoonist to another.

“There’s no point.”

“I couldn’t agree less.” He was a thin, beaky young man with a hollow-boned lightness and no romance in his heart. His hair was thick, blue black, and chopped above the ears. “Do you use a drawing tablet?”

“No.”

“Well, what’s your favorite inking tool? And what kind of ink, and which nibs, and how do you hold and use the nib? Can I get a demo tomorrow?”

“Sure.”

“Have you ever used a toothbrush for texture?”

The problem of walking and talking on a hilly, shifting terrain presented itself.

“Do you like to use a smooth paper or something more grainy?” He thought I knew the secrets and could lay them out for him like coconut macaroons. I told him we’d discuss it in class.

At the beginning of class he’d corrected my pronunciation of his name: “Not Veeshnu. Vishnu.” At the end of class he’d asked if I planned to cover self-publishing and self-promotion, and if I had advice on how to get his self-published work into circulation. I said no, but I only said it because I felt that a person who showed up with a stack of sophisticated mini comics to a class advertised for beginners could go fuck himself.

For the rest of class he’d just sat there, though when I asked if he had an idea to work on, he seemed to nod toward his massive accomplishment, his minis, and said he was deciding between a few possibilities, then asked if I had a pub date for my next comic, to draw a comparison I guess, that I wasn’t producing anything at the moment, either. When you’re the new guy, with a new book out, they treat you one way. When you’re the same guy six years later, it’s something else.

In the main office, a blond kid had me sign a tax form so I could get paid. He told me without smiling that they needed people after lunch for softball. According to the contract, teachers were expected to play.

FOUR (#ulink_e35ea99f-23fb-5310-93ec-2caa1afb8ffd)

In order to reach this place I’d crossed several state lines, mounted several bridges, exited highways, and ridden others until they ended. I eventually headed down a coveted stretch of land, surrounded by water on three sides, known by painters for its light, somewhat unto itself most of the year but overrun in July and August, and finally reached my destination.

Everybody knows a spot like this, a fishing village turned tourist trap, with pornographic sunsets and the Sea Breeze Motel. Out of respect for the powerful emotional attachments people form to such places, I’d rather not say exactly where I went, in the event that the detailing of my location causes even more congestion on the streets of that nicely preserved, remote southern New England coastal town.

A Dutch windmill stood at the highest point on campus, a replica or maybe the real thing, brass plates screwed to its siding from an ongoing fundraiser to repair it. On the distant practice fields, yellowing in the heat, the college held a lacrosse camp for high school boys and girls. It sat along some quaint national seashore, amid a high number of colonial-era buildings, among shifting mountains of sand, speckled with dune grass. A frolicsome place, a remote place, a place I’d barely heard of before coming here to teach. We arrived by bus or ferry or train or car, or airplane service direct from Boston. Because of its location, the conference had an easy time attracting artists, oil painters, memoirists, old guys, skitterish teenagers in search of illicit pleasures, driftwood sculptors, printmakers, actors, and playwrights.

They offered a filmmaking workshop. They taught all kinds of crafts. In the afternoon there were shuttles to the beach and a Ping-Pong table in the main building and shows in the gallery and staged readings of plays in the auditorium every night. The writers took classes in red brick buildings with white shutters. Other buildings were crumbling or had been condemned and were barricaded behind tall metal fences with posted signs. The actors camped out in the auditorium. The studios were over the hill, on the far side of the windmill, in what had once been a shipyard. Fine Arts occupied a long, skinny two-story wooden structure that creaked like a sailboat, shingled and faded, and there were cinder-block dorms where they’d put me the first two years, and a wharfy, flaking cottage where they stuck the gang of interns.

This year they’d put me in the Barn; it really was a barn, chopped into apartments for staff during the year, and still partly unfinished. The door to the top-floor apartment wasn’t locked, it didn’t even close, it thunked against the doorframe, swollen from the seacoast weather. It was one big open room with the angled walls of an attic, rusted skylights and a windowed cupola in the peak, and a narrow swath running down the middle of the room where you could stand up straight. There was a kitchen, frying pans whose handles fell off when you touched them, a coffee table and dresser, a white plastic fan, a filthy plaid couch, and two twin beds crammed in along the eaves.

I’d arrived on Friday at five and hung up my shirts, my head at an angle, hitting it once hard enough on a beam that I expected my skull to crack open and my brain to fall out. I stood on the bed and with some effort cranked open the skylight, stuck my head through, and looked out across campus. I heard a seagull bark like a dog. Over the rooftops of the little town I saw blue water, the harbor jetty, and a dinky lighthouse I’d never noticed before. I felt like I’d shimmied up the mast of a ship.

No humidity, no horrifying summer heat, no buses banging down the avenue, no garbage trucks, no marital rancor, just a clean white mattress on a low metal frame, and nobody to wake me up in the middle of the night by punching me in the head, or barfing down my neck, or giving me a heart attack every two hours with his bloodcurdling screams. Nobody else yelling “Daddy!” through the shower door. When I tell her to stop she begins kissing the door, because that’s how much she loves me.

I loved them, too. What would I do without them? All last week, I’d had moments of fear and excitement, waking up with a stomachache, worrying how they’d live without me, while peeling Kaya’s carrots, packing Beanie’s diaper bag, but also feeling less owned by them and maybe cocky and probably gloating, unintentionally ignoring Robin, and she’d noticed it, shaking her head and muttering how I’d already checked out or was too lazy to marinate the fish, rolling her eyes when I forgot to put ice in her water, not wanting it when I came back with the ice tray. Kaya picked up on it too, woke up in the night and needed to pee, wondering if she could have some potatoes, telling me about Louis, the turtle at camp, as we walked back from the bathroom and I tucked her into bed. Maybe it was all in my mind.

We shared our babysitter with the family of a girl named Molly. Robin had picked them up from Molly’s on her way home from work on Friday. I’d called them from the highway in the last hour of my drive. Her mom and stepdad were coming for dinner if they could get it together. I heard Beanie, grunting and sucking, and Kaya going, “Horsey horsey,” which meant Beanie was on Robin’s boob and Kaya was on Robin’s knee.

“Maybe they won’t come,” she’d said.

Her mom was in the late stages of dementia, and her stepfather was attempting to drink himself to death. Her sister lived three thousand miles away and never called. Her brother had faded into myth.

“It’ll be fine,” I said. “Make your frittata.”

“All right,” she said to Kaya. “Knock it off.”

“Kaya,” I said, knowing she could hear, “get off Mommy so Beanie can eat.”

“She used to make jokes: ‘When I’m drooling in the corner, smother me with a pillow.’”

“She’s not drooling.”

“Yet. But maybe this is when I’m supposed to kill her.”

“Don’t kill her tonight.”

“All right.”

“Or at least make it look like an accident.”

“Don’t tell me what to do. Kaya, stop it.”

“Sorry.”

“What’s wrong with you?”

I didn’t know who she was talking to.

If Robin needed help she’d call Elizabeth, who lived eighteen feet away. They liked to stand in the alley between our two houses and talk intensely as the girls rode up and down on their tricycles. Robin talked about Beanie’s sleep patterns and Kaya’s emotional IQ. Elizabeth talked about her fourteen-month-old’s language problems and her seven-year-old caving to the mind games of her five-year-old. They talked about clients Elizabeth saw for psychotherapy and a story editor who tortured Robin. They discussed clothing, did fashion shows for each other: can I get away with this, is this consistent with my persona? They talked about cutting off their hair, glass beads, making jewelry, maternity undergarments, the anti-inflammatory properties of turmeric, hot yoga, colon cleansing, the perils of a Montessori education, the naughty spanking trilogy, the sexy vampire movies, postpartum body issues, hip pain, back spasms, stretched stomachs, cosmetic surgery where they freeze your fat. If you got her talking long enough, Robin mentioned her weight, that she was bigger now, so she thought her head looked too small. They talked about sex and marriage, aging parents, the transformation of a loved one in decline, the terrible suffering of their mothers, helplessness and guilt.

I hung up and drove the last fifty miles to campus. After unpacking the car I went to dinner and ate barbecued chicken under the big white tent, at a table with Howard, a bald guy with a tanned, polished head, and Tina or Dina, who’d come here last year and made sculptures out of wire. After dinner we crowded onto the porch, where a poet read a poem. Carl gave his welcoming remarks, urging us not to climb through windows if we lost our dorm keys. Then we went off to see the theater company do a mash-up of Chekhov plays, set in the 1930s, with Uncle Vanya shooting himself in the second act, wandering in and out with a bandage on his head. In the big hall of the main building I heard Tabitha give the same talk she gave last year, about her spiritual journey beyond incest, into alcoholism, then past that, into group sex and casino gambling, ending in healing and forgiveness. In the gallery there were photos taken by an American soldier during some of the hundreds of trips he’d made while bringing fuel to stranded convoys all over Afghanistan, of the landscape, people, and culture, before he himself was finally blown up and killed. The photos survived. I ate some chocolate-dipped strawberries and talked to a woman with blue streaks in her hair.

Then I went back to the Barn, hung my pants on a nail in the wall by the refrigerator, and thought about Robin, what she was doing, what I’d be doing at that hour if I were home. It was just the usual struggle to stay in love, keep it hot, keep it real, the boredom and revulsion, the afterthought of copulation, the fight for her attention, treating me like a roommate, or maybe like a vision of some shuddering gelatinous organ she’d forgotten still worked inside her.

First a guy sticks something in you. Then a thing grows inside your body. Eventually it tears its way out, leaving a trail of destruction. Then it’s outside your body, but still sucking on you. It makes you weird, these different people in you and on you. Robin had had two C-sections and felt that they’d put her back together wrong the second time. A cold electric twinge shot down her back, down her leg, while walking, sitting, standing, or lying down. It defied any cure, painkillers, epidurals. For a while she wore a small black box on her belt that electro-stimmed her buttocks.

In a previous life, she bit my neck and licked my ear when we did it. After Kaya, I worried about courting her in my pajamas, with our little angel breathing down the hall, and lost focus and cringed as Robin’s patience ran out if I finished too fast or not fast enough and overstayed my welcome. Bad sex was better than nothing, but Beanie effectively ended the badness. Fuckless weeks, excused by parenting, turned weirdly okay. Like our anniversary, we weren’t sure anymore when it was supposed to happen. And, with the exception of my tongue on her clitoris every who knows when, she didn’t need to be touched. She had vibrators for that. I think she mostly thought of what I did as a way to save batteries.

Our sex life hadn’t been mauled by depression, routine, or conflict as much as it had been mauled by distraction, diffusion, a surfeit of beauty. Was that it? Our children’s vitality and strangeness, their softness, shocked me every day. Their lightness and willingness and spirit and stupidity surprised me, their readiness to bravely step into a world they couldn’t understand, packed with swimming pools, speeding cars, blazing sun, fanged dogs, stinging bees, heat, silent anger, slammed doors, inexplicable demands, funny hats slammed on their heads, and constantly from every direction these giants with twelve-pound heads, ten times their weight, five times their height, grabbing, pushing, shoving past, talking loud, telling them how to think, what to want, how to treat their own impulses, which ones to kill, which to love. No to crawling inside a dishwasher or smacking your food when you chewed. Yes to climbing trees and sucking your toes. I was sad for the bleakness of a little kid’s bumbling existence, envious of the simplicity of their cause. They faced the world because they had no choice. Someone was crying. Someone had pooped his pants. They were explorers in a new land. Robin and I stood by them, in parallel formation, to witness and guide them.

Parallel, as if on the same track, running at the same speed, but not touching and having no way to touch. Parallel like people who went to bed without remembering to say good night, or saying it without meaning it, or meaning it but not saying it. I appreciated how on those rare occasions when my wife would kiss me, she did so with flat lips, popping them the way she did when she smacked at her ice cream. In this way she turned my face into something more palatable.

Was it a good life? Was I more joyful, sensitive, and compassionate in my deeply entangled commitment to them? Was there anything better than seeing the world through the eyes of my nutty kids? Was my obligation to Robin the most sincere form of love? Or was I living despite their obstruction, intrusion, whatever? Had I instead been saved by the transcendent power of my ideas and work connected to the larger world, drawings I’d done for the magazine that illuminated trivial or important events of our time? Was I doing all I could to enrich and enhance and enliven my time on earth, or was I doing all I could to destroy, limit, or block any growth or connection? Or was I doing nothing, imitating real suffering while my time ran out, goofing around, rotting, sexless, ugly, and bitter?

Was this as close to love as I was ever going to get? The closer I got, the more I wanted to destroy the things I loved. Something rose up in me, threatening me. I had to deflect it somehow.

I’d never been able to beat back the loneliness of a solitary life, but as part of a couple I felt invisible and deformed, and even at those times when I meant what I said, my words of affection had to be forced through sarcasm and shame. When I misbehaved, acted out discreetly, impulsively, I felt unbreakable and invincible, although of course the guilt eventually tore me apart. And sometimes I examined those parts, and sometimes I pushed them away, but that was just pushing myself away, the pure, monstrous reality, the real me, and without those parts I was an empty shell. The longer it went on, the worse I felt, until I was out of control and panic seized me and I ran back home.

FIVE (#ulink_4287f33a-288f-546a-b3aa-fb41875f9f9c)

I’d spent the winter engaging in daydreams, fantasies, alternate realities, while flipping through emails in a secret folder, and looking at selfies of this same beautiful woman, barely clad in a towel at a fancy resort in Zurich, or on the swings with her kids at the park, or modeling the necklace I’d sent her at Christmas.

We met here a year ago. She took a class in the studio next to mine and pulled some late nights; we shared a bench in the courtyard, downwind of a cigarette. She was a nice woman with a few complaints, suggestible, not finished, wrapped up in her kids. She was unmoved by her own painting and thought her classmates were hilarious if a little hard to take: the lady who painted in her bra, the hipster who flirted with her in his little fedora. We bumped into each other in the laundry room, and went for a walk on the jetty at sunset, and talked about marriage, and stayed out late, and spilled our guts.

Wasn’t that the whole point of this place? To take a break and clear your head? And who really gave a fuck what two people did at an arts conference in some swinging summer paradise? Real life was so lonely anyway, and I figured I’d never see her again, so on the last night we went back to her dorm room and goofed around.

When the conference ended, we started zipping notes back and forth, just a few, then more and more. For a while I thought she’d leave him, and if she left him, maybe I’d leave Robin. But then she didn’t, and I didn’t, either. I saw her once in the fall, for an hour of furious hand holding and making out in a candlelit booth in New York City. And once in March, at her house in Connecticut. Then things got heavy and she stopped talking to me.

In June I sent her a birthday card and asked if she’d be coming back to the conference. It took her three weeks to say maybe. And now, after signing my contract and promising to play softball, as I headed to the tent for lunch, I thought about what might happen if she did. It didn’t help to think about it, but I’d spent a lot of time thinking about it anyway. I got excited. I still had passion. I came over a rise and the whole town lay beneath me, the buildings old and stinking of charm and practically spilling into the bay. I caught a whiff of sea life, a funky low-tide odor. For so long, I’d been deprived of even accidental physical contact. I needed love; short of love, I needed something. I saw myself as adventurous, amorous, and brave. I got stuck in some loop of possibilities and had to stifle a ridiculous little moan. I felt a dog-eared excitement, and rode that familiar surge of energy. By the time I reached the tent, people had worn a muddy track across the lawn between the check-in table and the buffet.

“Ha ya doin’? Everything good at home?”

“Yes!”

“You believe we’re back here again?”

I got something to eat and scanned the tent for the face I’d kissed and held, for those long legs of such smooth, glassy skin, striding briskly in the fresh breeze off the bay, for that stranger who’d hovered over me, gasping and weeping.

I didn’t see her, but students sometimes walked into town for meals. I went over by the brick wall and sat with some other faculty members, Vicky Capodanno, a painter, Tom McLaughlin, an old guy who’d written a memoir of his childhood, and this idiot biographer named Dennis Fleigel, who was waving his sandwich in the air. He had his foot propped on Vicky’s chair as she cut her salad.

“I read your book,” he said. I put my bag on the wall and downed my lemonade. I just wanted to eat. “Graphic novel, comic book, whatever you call it. What do you call it?”

“I’m not in that argument.”

“Do you check the number on Amazon?”

“It’s not in print.” I was eating some kind of chef’s salad, dry raw beets, chunks of cheddar, and these mysterious white cubes of something. This was a new, wholesome food service. “Hello, Vicky. Hi, Tom.”

“Richie,” Tom said. “How are you, bud?”

Vicky looked at me with deep intensity. “How are you?”

I couldn’t remember if I’d ever responded to her last email, from Vermont, where she’d gone to take a break from New York, trying to quit smoking, childless and out of romantic options, wondering how I was, asking for photos of me with my kids, or just my kids, or any cute kid stories—and I grinned at her like a lobotomized dope.

“I was just saying,” Dennis said, “that my book was selling, it sold pretty well, Amazon number below ten thousand for two straight years, word of mouth was good, but then that movie came out.”

“What movie?”

“Ring-a-Ding Ding. It’s about Sinatra, and when it came out, my Amazon number went from ten thousand to a hundred and fifty thousand, and it never went lower ever again.”

Charlene Wetzel joined us, smiling, and said, “I think I have a stalker.” More people sat down. “He wore sunglasses in class,” she said. “Last year, it took a few days. This year, first day: stalker.”

Heather Hinman, who taught poetry and had a coiled energy that included her hair, said that one of her students asked what font she typed in. Roberta Moser put her plate down and told us that she’d just finished an interview with the local NPR and that the questions were dumb.

I began to feel hopeless and desperate in a familiar way.

Dennis explained that NPR was fine for pushing an art film or a book, but that the machinery that promotes a studio movie is so much bigger. “Ring-a-Ding Ding the movie killed Ring-a-Ding Ding the book, and it never recovered.”

“What are we talking about?” Roberta asked.

“My book Ring-a-Ding Ding,” Dennis said, “and how it got killed by Ring-a-Ding Ding the movie, which I also wrote.”

Roberta smiled at Dennis. “I still don’t understand.”

Tom McLaughlin brought over a bottle of wine. Frederick Stugatz sat down with Ilana Zimmer, who put some wine to her lips and said, “I just got back from six weeks as artist in residence at the University of Bologna.”

Heather took a drink and said, “After this I go to Ole Miss.”

Frederick said, “After this I go to Berkeley.” He turned and stared at Ilana, who ignored him.

Dennis said, “Ring-a-Ding Ding the book is about a sensitive brute who happens to be the twentieth century’s greatest entertainer. The movie Ring-a-Ding Ding is a piece of shit. But that’s not my point. My point is that the kid who’s supposed to be eighteen was played by a twenty-six-year-old, and the eighteen-year-olds who saw it thought the guy looked like a senior citizen.”

Dennis had red hair and a pink forehead and surprisingly bright blue eyes. If you tried to make eye contact, he couldn’t see you. I liked to think of this as the result of some head trauma. It was a kind of blindness that made him unlikable but high-functioning. He’d written four biographies and two screenplays and went on morning talk shows when his books came out. I could imagine back in caveman days someone like him being cut from the tribe, dragged away, and thrown off a cliff.

Heather buttered a roll. She used to be a drunk but now wrote poems about bartending, drinking binges, blackouts, and AA. Roberta was a filmmaker. She’d been making a documentary for the past nine years about corrupt black mayors of major American cities, filming them in jail, running for office again, taking walks with their aged mothers. Frederick taught the musical book, whatever that was, and had been the genius behind last year’s musical about Karl Rove. Ilana Zimmer had headlined an indie rock band, with one hit in the eighties, then had a ho-hum solo career, and now dabbled in kids’ music. She ran a songwriting workshop every year in Frederick’s class. Vicky had paintings in museums around the world that were violent, cartoonish, biting, dark, and funny, that dealt with war, religiosity, porn, rape, but also the cost of art education, women’s bodies, and people who lived in garbage dumps. And Tom McLaughlin had been a high school English teacher for forty years, then retired and wrote a rambling memoir of his childhood growing up over a pool hall in Alffia, Texas, population 71, with wrenching scenes about killing cattle and the death of the town; it became an instant classic, then a hit movie. He sat there like the most relaxed guy in the world, his face heavily lined, familiar in a way from posters of him around the conference—they were hard to miss, his head gleaming and speckled with age spots.

The thing to do here was relax and not worry about where I ranked among them. I pushed my plate away and started drawing on the tablecloth. I drew the bay, a single steady line, wispy clouds in the distance, and walking along the shore I drew Batman, the Caped Crusader, looking a little haggard and overweight. Last year’s tablecloths had been made of a thick, toothy paper, with a spongy plastic coating underneath, but this was thin one-ply, and the ink bled like I was drawing on toilet paper. It was a waste of time, but I didn’t care. Batman was the first superhero I’d ever drawn. I hadn’t drawn him in thirty years. Why now? Drawing him middle-aged with a big keister seemed to answer something. He stood in the surf at low tide with a touristy camera around his neck and his tights stained dark from wading.

One line led to another, the feeling of deadness went away, and this arrangement of markings became a scene with a little girl about Kaya’s age holding Batman’s hand. Was it a memory? Was it cathartic? Did it work? I didn’t care. I kept going, surprising my eyes with what my hand could do. In Batman’s other arm I drew a little boy in a swim diaper—my knees bouncing under the table—until, shading in the bay around their ankles, I pressed too hard and tore the tablecloth.

Then I thought of home and felt my throat close up. I wondered how I’d protect my kids from hundreds of miles away. I worried that Kaya would ride her tricycle into the renovation pit from the construction next door. I worried that Beanie would suck the propeller out of my old tin clown whistle. Joey, the high school kid down the block, sometimes cut through the alley in his Subaru with his foot on the gas, even though a dozen kids under the age of ten jumped rope and played games there. A spasm of electric jolts shocked my heart, from the heady mixing of blood and guilt that brought on flashes of horror and feelings of dread and excitement, the fear that I would do something sexy and rotten and get away with it.

Stewart Rinaldi pulled up a chair and said, “What did I miss?”

“We’re talking about my book,” Dennis began, “Ring-a-Ding Ding.”

No one could stop him from explaining that the movie killed the book. When he finished, no one spoke. Beside me, Charlene folded things into a sandwich.

“Pass the salt.”

We had nothing else to say, or didn’t want to try for fear of starting Dennis up again. We didn’t discuss the news of the day or the presidential campaign or politics in general, power, money, greed, or war. As members of the cultural elite, we didn’t believe in any of that. We’d been teaching together for years. We sat in circles, bragging about things that mattered only to us. We were artists. We believed in ourselves.

And yet, things were happening out there. Obama had drawn a red line but Assad refused to back down, while hundreds of thousands fled, in what was looking like a massive refugee crisis. “Call Me Maybe” held steady at No. 1. Ernest Borgnine died. Kim Jong-un had been named Supreme Being of North Korea. The Republican primary had been brutal, awash in dark money, the first since the Supreme Court decided that mountains of secret cash in exchange for favors was totally fine. Romney emerged as the nominee, a hollow, arrogant flip-flopper. He’d spent the summer refusing to release his most recent tax returns, while his legal representatives explained away the Swiss bank account stuffed with tens or hundreds of his own millions. He was in London this week, having FedExed his wife’s half-million-dollar dressage horse over to compete in the Olympics.

We didn’t care about that stuff. We cared about art. We cared about lunch. Finally Dennis stood, picked up his bag, and walked out of the tent, past the drinks cooler, toward the library.

“Ring-a-ding ding,” Roberta said. “Does that ring any bells?”

“Forget it,” Tom said.

People liked Dennis as a teacher. Around the faculty, though, he lost control. He engendered pity, which must’ve bothered him. The interns were clearing off the buffet table behind us, watery bowls of lentil salad no one wanted. Roberta said Dennis’s wife had moved out, and Charlene shook her head and said it was a long time coming. Frederick turned to stare at Ilana, who pretended not to notice. Vicky asked why we had to sit here, year after year, talking about Dennis Fleigel, and wondered if anyone wanted to go for a swim in the ocean, and gave me a deep, meaningful look, but I didn’t want to linger, to catch up, didn’t want to be her beach pal. I couldn’t listen to the grievances of childless grown-ups anymore, their boredom with their free time, wondering what they’d missed. Whatever had caught up with them was making them depressed.

SIX (#ulink_ca088b97-a535-5be9-b375-a6179aec3f86)

In college I couldn’t figure out what to major in. Over in English they were complaining that language itself had become brittle and useless, and over in art, so-called postmodern painting was being taught in a way I didn’t understand, as the subject as object ran into ontological difficulties that couldn’t be solved with a paintbrush. I started making comics for some relief—leaning heavily on my own journals, since I’d never learned how to make up anything—an episodic, thinly veiled series of stories about a girl and boy who fall in love, stay up late, eat pizza in their undies, make charcoal drawings, create installations of dirt and lightbulbs, hate their fathers, move into an apartment together, build futon frames, flush their contact lenses down the drain, throw parties with grain alcohol punch, get knocked up, have an abortion, read Krishnamurti, graduate, break up, fuck other people, and move together to Baltimore, to an abandoned industrial space where sunlight comes through holes in the roof, dappling the walls.

After college I published it myself, on sheets of eight and a half by eleven, folded in half and pressed flat with the back of a spoon, stapled in the middle, and handed it out personally at conventions for a dollar. Making comics kept me from going apeshit. Later, at the ad agency where I worked, I upped the production value, made the leap to offset printing, sending it through on the invoice of a client in St. Louis, who, without knowing, paid for my two-color card-stock cover. I didn’t dedicate myself to it, didn’t plan on toiling for years. I figured I’d do a few more, get a job as a creative director, drill holes in my head and use it as a bowling ball.

One day I got a call. “We like your comic. We’d like to publish it. Would you be interested in that?” I remember walking around the office, heat boiling my face, wondering who to tell. Soon my work began appearing in a free alternative weekly. A year after that, I cut a deal with a beloved independent publisher for a comic book of my very own. When I finally held it in my hands, twenty-four pages, color cover, I lifted it to my face and inhaled. I caught the attention of agents and editors, and a couple of big-name cartoonists, who championed my work, and the thing took on a life of its own.

All of a sudden I’m cool, phone’s ringing, there are lines at my tables at conventions. My cross-hatching improved; my brushwork became fearless. I put out two issues a year. The comic grew to thirty-two pages, then forty-eight.

TV and film people started calling. I quit my job and helped write a pilot. I flew to Brussels to be on a panel of cartoonists. I designed a book cover for a reissue of On the Road, did a CD jacket for a legendary L.A. punk band. I lived on food stamps, even as my ego ballooned. I broke into magazines, and caved to the occasional job for hire, and torched my savings, and somehow got by.

But in my own comics, I handled the hot material of my life. My characters were shacking up, doing PR for the Mafia, suffering premarital anxieties and fertility issues. My publisher suggested collecting these comics into a book. The book held together like a novel. It came out six years ago.

They couldn’t sell the TV pilot. The book went out of print. I couldn’t tell stories about myself anymore. I’d flip through my sketchbook, dating back to before Kaya was born, life drawings, junked panels, false starts, art ideas, rambling journal entries, then babies in diapers and crawling and wobbling, and all this tearstained agonized writing about how tired I was. Then I’d start to think about What I’m Capable Of, but then I’d think, Who cares. Fuck comics. I couldn’t write about these scenes of domestic bliss, maybe because they lacked the reckless, boozy, unzipped struggle of my youth, or maybe because my wife and kids were some creepy experiment I couldn’t relate to, or maybe because they were the most precious thing on earth and needed my protection from the diminishing power of my “art,” and writing about them was evil.

In my stories I’d been some kind of wild man, some bumbling lothario wielding his incompetence, mistaking his sister-in-law for a prostitute, knocking over the casket at the funeral of his boss, battling suburban angst and sexual constraint in a fictionalized autobio psychodrama. My success at selling that renegade message opened up a sustainable commercial existence, the very existence I’d been trying to avoid. Instead, I embraced conformity, routine, homeownership, marriage, and parenthood, in exchange for neighborly niceties and a sleepy, toothless rebellion in the pages of a crusty political magazine trying to be hip. I worked as an illustrator now, or what might be referred to as an “editorial cartoonist.” I’d also done other types of unclassifiable commercial whore work, promotional posters for a Swedish reggae festival, fabric patterns for a hip-hop clothing company. I had a handful of regular clients from over the years, a hotel soap manufacturer, a Canadian HMO, a fried chicken chain in the Philippines whose in-house art department called when they got totally overwhelmed, although it had been a while, actually, since I’d done any of that crap.

Magazine work asked less of me, and paid more, and at times could almost be fun. I’d done drawings of Anthony Weiner, the Arab Spring, bedbugs, the uprising in Syria, Walmart slaves, Obama as a jug-eared mullah, Obama in his Bermuda shorts in the Rose Garden burying tiny flag-draped coffins, the whole clown car of Republican kooks who’d been rolling across the country all year—Michele Bachmann, Herman Cain, Newt, Rick Perry, and several of Mitt. In one he’s waving from his yacht, and in another he’s wiping his ass with an American worker, and in yet another he’s burying his loot in the Caymans. I’d also done full-page drawings for longer features, assigned by Adam, my art director: Somali pirates, Gitmo prisoners force-fed on a hunger strike, and a dozen covers—“The CIA in Damascus,” “Stop Eating So Much Meat,” “The Breast Issue,” “Our Complicated Relationship with Drones.” I could make a living if I worked fast, on three things at once, and didn’t mind the art department yanking my chain.

SEVEN (#ulink_a443187d-e1a1-59ed-be30-3b05d337b683)

At midnight Beanie got hungry, and at three A.M. he made a sound like a cat being run over by a car, for an hour without stopping. At six he got up for good.

“I hope you have a better night tonight.”

“Please don’t talk about it.”

I regretted having called. They were at the park now, in unrelenting heat and humidity. I sat on a low brick wall by the flagpole, the Place of Good Reception, overlooking the sweep of the harbor, the bridge in the distance, seagulls curling in arcs under high pressure and plenty of sunshine, the temperature a breezy seventy-eight degrees, a skosh below the seasonal average.

First thing this morning they went off to gymnastics camp, where we’d enrolled Kaya for the next four Saturdays, and met a nice blond lady who knelt beside Kaya when Robin tried to leave, and a dark-haired unsympathetic woman collecting the pizza money, and a teenage gymnast, holding a sobbing girl, about Kaya’s age, in a pink tutu with a blue lump on her forehead and an ice pack on her wrist.

Kaya had enjoyed the trampoline but not the rope thing. Then some boy shoved her, waiting in line for a cookie. She’d let another boy lie on top of her during circle time, they bumped heads, and now she had a swollen lip. She quit after lunch and said she’d never go back.

Robin’s parents had made it to dinner last night after all, but it seemed that Dave hadn’t changed Iris’s clothes, and her hair was dirty. The last time I’d seen my mother-in-law, she’d used mascara to draw on eyebrows, and wore eye shadow that looked like fireplace ash, and had a bruise from a fall discoloring one side of her face. Every time she walked into a room Robin would walk out, as if an alarm had gone off, explaining loudly that one of the kids needed a cracker, and her mom would sit and tell me how fat people were in Florida, or call Robin’s stepfather Dan, or tell me she had a baby in her belly that was painful sometimes.

Robin mentioned the urinary tract infection her mom had, a result of Dave’s neglect. He’d done his best to nurse her along, while also resisting and denying the obvious. By the time he’d finally given in and had Iris tested, she’d been tying her blouses in front for a year because she couldn’t figure out how to button them. I’d gotten used to the pantomime at dinner, nodding and smiling when she abandoned her fork and pawed through her plate.

Dave and Iris had worked hard all their lives, and this caretaking and dementia were their only retirement. He didn’t have religion or children or close family of his own, but he’d confided in me that after Iris died, he planned to take a bicycle tour through the wine regions of Tuscany. He enjoyed the light-tasting Chianti of Florence, as well as the more full-bodied pinot chiefly associated with Pisa. He’d already done the research.

“I need to talk to her nurses,” Robin said. “I have to call the house when Dave’s not there.” I could hear Kaya singing in the background. I could picture the bench where Robin sat at the park by a sweltering playground. “If he’s home, they won’t say anything.”

It was the song Kaya had been singing in the kitchen before I’d left. “Shakira, Shakira!”

“They’re not nurses,” she said. “They’re probably corn farmers. Or soldiers. When did the war end in Sierra Leone?” I said I didn’t know. Kaya yelled for Robin to watch her climb.“He’s so incapable of dealing with his grief.”

Actually, I thought Dave was holding up pretty well, considering. The steroid he took to suppress whatever was choking his lungs had terrible side effects. His face was bloated and his skin had turned red, thin, and fragile. His beard had gone white. He looked like Santa, if Santa started drinking every day at lunch, which Dave did.

“How come this morning at an air-conditioned gymnastics place for seventy-five bucks an hour she wouldn’t get off my lap, but we come here in a million degrees and she can’t stay off the monkey bars?” I figured it was because she knew the layout, but kept it to myself. “I got so mad at her for quitting. I started screaming, ‘You never try. Why is that?’ I’m sitting outside gymnastics, sweating my ass off, holding Beanie, she can literally see my head from the window, and twice she came out crying, saying she missed me. I just wanted to close my eyes for five seconds. You know how you say I never admit I’m wrong? Well, I was wrong, and I’m not just telling you I abused her to make you feel guilty. I went too far.”

“I’m sure you didn’t.”

“I had to shove him into his stroller so I could deal with her, but he wouldn’t let go, and I pressed down so hard I thought I broke his rib cage.”

“Jesus.”

“At lunch, the nice counselor let her sit on her lap, but the mean one told her she was a big girl and should stop crying. I’m going to find that one and explain to her that it doesn’t do any good to tell that to a four-year-old.”

“You tell Kaya that all the time.”

“That’s different.”

“Why is it different?”

“Because she woke me up five hundred times last night. Oh, here she is. You woke me up five hundred times last night.”

“I’m sorry, Mommy.”

“You don’t sound sorry.” It was true: Kaya didn’t sound sorry. I looked out at the bay, the sky, the seagulls, thankful for the distance between us.

“I’m locking her in her room tonight.”

“With what?”

“I’ll buy a hook.”

“Why didn’t I think of that?”

“I don’t know.”

“Because I wouldn’t do that to a dog.” Two sailboats tacked at the same angle as they cornered around the jetty.

“She’s not used to being ignored in the middle of the night. One peep and you’re there, hovering over her. Maybe now she’ll finally get sleep-trained. Now she’ll learn to spend the night in her bedroom alone.”

“You’re going to sleep-train her in one night?”

It went on like this for a while.

“It’s you, you feed and flirt and sing and have conversations at three A.M.—”

The bay, the water, the seagulls.

“When you’re here, it’s always ‘Daddy Daddy,’ keeping them out of the basement so you can work, brokering that. When you’re not here, it’s quiet and I feed them early and put them to bed early, not at nine o’clock—”

“Hey, why don’t you take the night shift for the next four years?”

“Because I need drugs to sleep.” Beanie let out that piercing cat scream. I heard her whacking him on the back. “And when I take medication, I need more sleep. I’m not doing this for you next summer, so have fun.”

“I’m having a blast.”

“I don’t care what you do up there, but if you give me a disease I will cut it off. Got it?”

“Fine.”

“Or shoot you. Or chop off your balls.”

“Understood.”

Beanie remained quiet, and then we were all quiet.

“I wouldn’t mind going to some makeout festival if my body wasn’t broken.”

“Go ahead.”

“As long as you take care of them while I take care of me.”

“I should probably get back to it.”

“You didn’t say how your first class went.”

“My class?”

“Yes.”

“Fine.”

“You say that every year. You worry about that class for weeks, slaving over your notes, ‘What do they want from me? I forgot how to teach!’ It hardly pays anything, and you’re up there having a blast and I’m here killing myself and for what?”

“At least it gets me thinking about comics again. I used to love making comics. I don’t know what happened. I have to get a break from the magazine. I have to start something I care about. I have to find a way back in.”

“Maybe you’re not supposed to write stories about your life anymore. Maybe you outgrew it. Maybe it bubbles up because you’re there and you should force it back down where it came from.”

“Thanks.”

“Or maybe being around those people, you’ll have an epiphany.”

“Sure.”

“Go on, shove it down. Next to your childhood. Next to your parents. Keep shoving.”

“You don’t know anything about me.”

“I know all about you. That’s what you’re trying to get away from. You think you’re worthless, so you make me feel worthless, and when you’re gone I don’t have that, nobody second-guessing me or giving me nasty looks or turning off my music or criticizing my soul. It’s more work, but there’s no time to be depressed or think, although I actually can think. Four producers are coming from L.A. on Monday, I’m meeting with the network, it’s the busiest time and budgets are insanely tight and Realscreen is right around the corner. I can keep fairly complicated ideas in my head without having any obligation from you to talk and listen. I’m myself. I get love from people at work, and Karen Crickstein wants to meet me for lunch, and Elizabeth comes over and we do the knitting tutorial, and have conversations that matter, and she doesn’t wish I would shut up and go away.”

EIGHT (#ulink_cf81c7fc-912a-504e-83e3-f4da1a5a8cd1)

The first time I saw her, standing in my foyer, she was holding a giant stick bug in a wooden frame. Robin Lister had moved to Baltimore for a job at the public television station, and knew somebody who knew the sister of this lunatic, Julie, who lived in our group house on Chestnut Ave. Robin took the room of the guy we called Lumpy, who was headed to law school in Denver, which meant we’d be sharing a bathroom.

I helped carry in boxes from her U-Haul. That night I heard her spitting into the bathroom sink, and the next morning I found her in the kitchen, in a thin yellow robe with tiny blue fishes, staring into the garbage, trying to figure out how many cups of coffee she’d already had by the look of the used filter. When I think back to whatever it was that brought us together, it probably happened in the kitchen. She’d been hired to write and edit bilingual scripts for a local children’s television program and had tape drives of old episodes to study, but she already had a few things to say about the show’s three main characters, a hyperactive skunk, a Hispanic beaver named Anselma, and a wise old chipmunk who protects the young explorers.

I found myself sitting across from her, lingering over breakfast, offering piercing analysis of our roommates’ psyches: Nedd, the ladies’ man; Rishi, an account exec at the ad agency where I worked; and Julie, the emotionally stunted MBA who talked like a baby. Robin had questions, and I projected a confiding warmth and a loud, Jewish, overcompensating wit.

She was seeing a guy named Jim, who deejayed on the weekends. He was followed by Digger, a cameraman from the Czech Republic who worked in war zones and had always just stepped off an airplane held together with duct tape. He’d been to the Congo, had ridden a horse across Afghanistan. Somehow, a year passed. I’d been dating Eileen Pribble, an elementary school art teacher who stuck refrigerator magnets to the outside of her car.

Robin and I were friends, although she was too good-looking for that. She needed company. I thought I might earn something, through my loyalty, that someday I would collect. At first I didn’t know what to make of her, but after a while I noticed how much I looked forward to her coming home at night. After dinner, the two of us would sometimes walk down the street for ice cream. She had hazel eyes, thin, wavy brown hair, and olive skin. The hair resting thinly on a delicate skull held an introspective, self-doubting, reasonable, forceful, somewhat dignified mind. She wanted to get out of kids’ programming and work in hard news, wanted to see the world. Digger had friends who could help. In the fall of that year, two Sudanese guys had blown a hole in the USS Cole as it refueled in Yemen. The new trend in terrorism, Robin said, was asymmetrical, like a bottle of botulism in a New York City reservoir. She wanted intensity and danger. She was so pretty that guys would stare at us as we walked down the block. Sometimes I worried that one of them would try to kill me.

Eileen and I split, and I thought for sure it would change things. I remember standing in the bathroom when no one else was home, examining Robin’s tongue scraper, and found myself pondering the wall that separated our bedrooms, wondering if I could tunnel through it to find her there asleep. There were moments where I’d given up, moments where I got obsessed, moments where I was repelled, moments where I’d grown too emotionally attached. I felt feverish and sick whenever Digger spent the night, trying not to listen while brushing my teeth, long sick sleepless nights until he left for some war zone in East Timor, until he moved back to Prague for good. In the mornings Robin and I had those nattering exchanges old couples have, bickering in front of our housemates or alone, about the missing butter or how long to boil an egg. If her insomnia plagued her, she’d shoot me a look—and I can remember now, the rush of blood in my face. I felt somewhat powerless, and assumed it would pass.

She’d ask my opinion on her clothing before work in the morning, she’d notice my haircut or suggest I stop chewing ice before I cracked a tooth. I wanted her to love me. There was this basis forming beneath us. Sometimes we walked together to the nearby community center for our morning laps. I’d spy on her from underwater, her thin arms balletic and almost lazy in their strokes, a weird, improper technique, her legs kicking furiously, frothing the water around her.

Julie took a job in Atlanta. Nedd moved out. The housemate thing collapsed. Rishi and I found a place in Fells Point. Robin moved into an apartment alone, two rooms with a refrigerator under the counter and the smallest kitchen sink you ever saw. It was fall. One night I brought her flowers and beer and got a home-cooked meal. She was my friend, she took pity on me, I was a pitiful tortured person who could make her laugh. A wall of books greeted me when I walked into the apartment, film theory, life on the Serengeti, prehistoric pottery of the Colorado Plateau, whatever she was interested in.

She didn’t want me, maybe didn’t trust me, saw something missing, wanted less, a lighter commitment, or was holding out for someone who could take care of things down the line. I couldn’t cope with her withholding, couldn’t talk to her about us. I played the part of the ironic, submissive romantic, and she played the partially compliant friend of the opposite sex, sexually complicated, rigid, obsessive, a tease. I was protective and patient but losing hope. She was emotionally damaged by the death of her brother and her parents’ divorce.

On a weekday morning in December, some lady blew through an intersection and T-boned Robin’s Jetta. Thus began the period of her concussion. It lasted through the spring with a sort of merciless momentum. The nausea alone almost killed her. She wore sunglasses at work, had trouble looking at a screen, couldn’t tolerate light or music or ambient noise. Went to neurologists, did brain-rehabilitation exercises, memorized colored playing cards. I came and went, brought groceries, made phone calls to her auto-body place and health insurance. I still recall the soft shush of a beanbag she tossed from one hand to the other, crossing the midline.

Indoors at night she wore shades under a floppy wide-brimmed hat, looking like a Russian double agent, one I called Farvela Du Harvelfarv. By cooking for her in the stuffy apartment, I earned the right to sit quietly while she talked to her mother, rubbing a certain spot on her temple while she cried, wondering whether she’d ever recover. She became softer, less guarded, quietly resting beside me, resigned to a constant migraine-type vertigo. But because it wouldn’t end, it seemed to get worse. She couldn’t exercise. Went to bed at eight. Was sad and strange to herself.

Overcome by a wave of anguish, she slept with me. In that way, we began sleeping together. I think it was, even for her, a consolation. And yet, I couldn’t help feeling, as I learned to take on her bottomless fears of permanent damage, that the inordinate conditions under which she lived had forced her to surrender. I remember pulling her onto my lap, kissing her head in different places. She was so vulnerable and open. I wished we could always live that way.

NINE (#ulink_edae17ea-de88-5f3b-a2ef-330a15f3a302)

What I knew about Robin at twenty-six has since been overwritten by our twelve years together, by the fuzzing of boundaries that separate us, by events we faced beyond our abilities, by the sound of a four-note wooden xylophone our son liked to beat the shit out of at five A.M., and by the immutable cycles of birth and sleep. It’s not an excuse, for anything really, but there were nights Beanie woke up screaming every fifteen minutes. I could count on one hand the times in his life he slept more than two hours straight. It became a secret among us, like domestic beatings, what went on in our house after dark.

Sometimes I blamed our daughter, who fell between the mattress and the wall, or had bears in her dreams, or the rain upset her and drove her out of bed. Sometimes I blamed my wife, who never did figure out how to sleep, who needed protection from the chaos, and wore earplugs and a satin eye mask, and had a bag of prescription drugs she kept hidden in her underwear drawer, and in an emergency had to be shaken awake, and couldn’t go back to bed or take naps during the day, and in sleep debt quickly spiraled into anxiety and short-term mania.