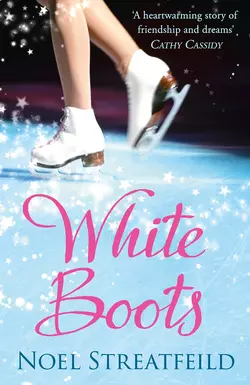

White Boots

White Boots

Noel Streatfeild

The author of children’s classic ‘Ballet Shoes’ delights with a best-loved story of ice skating rivalry…“If you pass your inter-silver, I’ll tell Aunt Claudia that I don’t want to work with you any more.”Harriet is told that she must take up ice-skating in order to improve her health. She isn’t much good at it, until she meets Lalla Moore, a young skating star. Now Harriet is getting better and better on the ice, and Lalla doesn’t like it. Does Harriet want to save their friendship more than she wants to skate?

Noel Streatfeild

Illustrated by Piers Sanford

Copyright (#ulink_cada6c6a-265c-56c8-aa22-7553b4c64625)

First published in Great Britain by Collins 1951

This edition published by HarperCollins Children’s Books 2008 HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd, 1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is www.harpercollinschildrensbooks.co.uk

Text copyright © Noel Streatfeild 1951

Postscript copyright © William Streatfeild 2001

Why You’ll Love This Book © Cathy Cassidy 2008

Illustrations by Piers Sanford

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Conditions of Sale

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior written consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007580453

Ebook Edition © October 2012 ISBN: 9780007380763

Version: 2018-05-16

CONTENTS

Cover (#ue46f1b94-e723-5565-8680-1a264b341d87)

Title Page (#u4dff1da8-dd68-50f4-adea-b65e488c408a)

Copyright (#uc53ac85c-5dcc-5fcb-bc14-014051a49ccb)

Why You’ll Love This Book by Cathy Cassidy (#u5a9d00ac-c5f7-5abb-adc9-2dbf5cfd2e2a)

1. The Johnsons (#u65f42095-fa62-5c35-9486-17cdabc9ee80)

2. Mr Pulton (#u75d53c45-b521-5664-a130-0b22c87e5927)

3. The Rink (#u5bb00439-677d-585d-89fa-0c33f0ba2433)

4. Lalla’s House (#u42c25881-a397-5227-9ed3-58ea63a443fb)

5. Aunt Claudia (#u4b424b9c-0217-5765-ae06-9769c47800b9)

6. Sunday Tea (#litres_trial_promo)

7. Inter-Silver (#litres_trial_promo)

8. Christmas (#litres_trial_promo)

9. Skating Gala (#litres_trial_promo)

10. Silver Test (#litres_trial_promo)

11. Plans (#litres_trial_promo)

12. Loops (#litres_trial_promo)

13. The Quarrel (#litres_trial_promo)

14. The Thermometer Rises (#litres_trial_promo)

15. The Future (#litres_trial_promo)

More Than A Story (#litres_trial_promo)

Postscript by William Streatfield (#litres_trial_promo)

Did you know? (#litres_trial_promo)

Skating Firsts (#litres_trial_promo)

Know your skating jumps (#litres_trial_promo)

Figure skating and beyond… (#litres_trial_promo)

British Skating Champions (#litres_trial_promo)

Get Your Skates On (#litres_trial_promo)

Who does what? (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Other Works (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Why You’ll Love This Book by Cathy Cassidy (#ulink_587e2af5-1f1a-5b77-9979-dcffb7abdb69)

When I was growing up, books were an escape, a passport to a whole new world. Nothing very exciting ever seemed to happen to me, but I could open the pages of a book and imagine myself as a ballerina or an ice-skater or a lonely orphan at a strict boarding school… and I loved that! Books seemed like a kind of real-life magic to me, back then.

Ballet Shoes was the first Noel Streatfield book I read and loved, so when I discovered White Boots, I devoured that too. The story is not just about Harriet learning to skate, but her friendship with rich, spoilt skating star Lalla Moore. It explores the themes of jealousy, loyalty and dependency within a friendship, things I now write about in my own books! Friendship is something that matters to all of us, whatever our age, but it takes hard work and determination to make a friendship strong, as Harriet and Lalla find out.

I loved the ice-skating background of White Boots – as a child I had never been on the ice at all, and that whole world of cute little skating dresses and white boots seemed impossibly cool and glam. I never did get the hang of ice-skating, even as an adult, but I still love to watch those who can and dream of what might have been!

Re-reading White Boots again now, I was fascinated to find it was written in 1951, just 11 years before I was born… yet as a child, the time and setting of the book seemed very distant. Again, it was another world to me – a post-war world of genteel poverty, with nannies and governesses and nurseries. I was fascinated. It couldn’t have been more different from my own life, and I think that 21st century readers will feel the same… some things have changed so much, yet some not at all!

Apart from the romance of the skating scenes, some of my favourite parts of the book were those with Harriet’s brothers – they were kind, practical, lively boys who welcomed Lalla into their lives. I especially liked Alec, and his shopkeeper friend Mr Pulton who tells him to follow his dreams. That’s a message that has always stayed with me – and one that crops up in just about every book I write.

White Boots is a little slice of the past, which still captures my imagination, and its themes of friendship, family and staying true to yourself are timeless…

Cathy Cassidy

Cathy Cassidy is a bestselling author of fun and feisty real-life stories for girls, including Dizzy, Indigo Blue, Lucky Star and Ginger Snaps. Cathy wrote and illustrated her first book at 8 years old for her little brother and has been writing and drawing ever since. She has worked as an editor on Jackie magazine, a teacher and as agony aunt on Shout magazine. She lives in Kirkcudbrightshire, Scotland with her husband, 2 young children, 3 cats, 2 rabbits and a mad hairy lurcher called Kelpie.

Chapter One THE JOHNSONS (#ulink_e69097b4-b52a-543f-962f-f72ef647940e)

EVEN WHEN THE last of the medicine bottles were cleared away and she was supposed to have “had” convalescence, Harriet did not get well. She was a thin child with big brown eyes and a lot of reddish hair that did not exactly curl, but had a wiriness that made it stand back from her face rather like Alice’s hair in “Alice in Wonderland”. Since her illness Harriet had looked all eyes, hair and legs and no face at all, so much so that her brothers Alec, Toby and Edward said she had turned into a daddy-long-legs. Mrs Johnson, whose name was Olivia, tried to scold the boys for teasing Harriet, but her scolding was not very convincing, because inside she could not help feeling that if a daddy-long-legs had a lot of hair and big eyes it would look very like Harriet.

Harriet’s father was called George Johnson. He had a shop. It was not a usual sort of shop, because what it sold was entirely dependent on what his brother William grew, shot or caught. There had been a time when the Johnson family were rich. They had owned a large house in the country, with plenty of land round it, and some fishing and shooting. The children’s great-grandfather had not been able to afford to live in the big house, so he had built himself a smaller house on the edge of his property and let the big house. When his eldest son, the children’s grandfather, came into the property he could not afford to live even in the new smaller house, so he brought up the children’s father, and their Uncle William, in the lodge by the gates. But when he was killed in a motor accident and the children’s Uncle William inherited the property he was so poor he could not afford to live even in the lodge, so he decided the cheapest plan would be to live in two rooms in the house on the edge of the property that his grandfather had built, and to let the lodge. When he had thought of this he said to his brother George, the children’s father, “I tell you what, young feller me lad”… he was the sort of man who spoke that way… “I’ll keep a nice chunk of garden and a bit of shootin’ and fishin’ and I’ll make the garden pay, and you can have the produce, trout from the river, and game from the woods, and keep a shop in London and sell it, and before you can say Bob’s me Uncle you’ll be a millionaire.”

It did not matter how often anyone said Bob’s your Uncle for George did not become a millionaire. Uncle William had not married, and lived very comfortably in his two rooms in the smaller house on the edge of his estate, but one reason why he lived so comfortably was that he ate the best of everything that he grew, caught or shot. The result of this was that George and Olivia and the children lived very leanly indeed on the proceeds of the shop. It was not only that William ate everything worth eating, which made life so hard for them, but people who buy things in shops expect to go to special shops for special things, and when they are buying fruit they do not expect to be asked if they could do with a nice rabbit or a trout, especially when the rabbit and the trout are not very nice, because the best ones have been eaten by an Uncle William. The children’s father was an optimist by nature, and he tried not to believe that he could be a failure, or that anything that he started would not succeed in the end; also he had a deep respect and trust for his brother William. “Don’t let’s get downhearted, Olivia,” he would say, “it’s all a matter of time and educating the public. The public can be educated to anything if only they’re given time.” Olivia very seldom argued with George, she was not an arguing sort of person and anyway she was very fond of him, but she did sometimes wonder if they would not all starve before the public could be taught to buy old, tired grouse, which had been too tough for Uncle William, when what they had come to buy was vegetables.

One of the things that was most difficult for Olivia, and indeed for the whole family, was that what would not sell had to be eaten. This made a great deal of trouble because Uncle William had a large appetite and seldom sent more than one of any kind of fish or game, and the result was that the family meals were made up of several different kinds of food, which meant a lot of cooking. “What is there for lunch today, Olivia?” George would ask, usually adding politely: “Sure to be delicious.” Olivia would answer, “There’s enough rabbit for two, there is a very small pike, there is grouse but I don’t really know about that, it seems to be very, very old, as if it had been dead a long time, and there’s sauerkraut. I’m afraid everybody must eat cabbage of some sort today, we’ve had over seven hundred from Uncle William this week and it’s only Wednesday.”

One of the worst things to Harriet about having been ill was that she was not allowed to go to school, and her mother would not let her help in the house.

“Do go out, darling, you look so terribly thin and spindly. Why don’t you go down to the river? I know it’s rather dull by yourself but you like watching boats go by.”

Harriet did like watching boats go by and was glad that her father had chosen to have his shop in outer London in a part through which ran the Thames, so she could see boats go by. But boat watching is a summer thing, and Harriet had been unlucky in that she was ill all the summer and was putting up with the getting-well stage in the autumn, and nobody, she thought, could want to go and look at a river in the autumn. In the summer their bit of the Thames was full of pleasure boats, and there were flowers growing on the banks, but now in October it was cold and sad and grey-looking, and only occasionally a string of barges or a small motor launch came by. But it was no good telling her mother about the river being dull; for one thing her mother knew it already and would only look sad when she was reminded of it, and for another her mother heard all the doctor said about fresh air and she did not; besides she was feeling so cotton-woolish and all-overish that she had not really got the energy to argue. So every day when it was not raining she went down by the river and walked drearily up and down the towpath, hugging her coat round her to keep out the wind, wishing and wishing that her legs would suddenly get strong and well again so that she could go back to school and be just ordinary Harriet Johnson like she had been before she was ill.

One particularly beastly day, when it looked every minute as if it was going to rain and never quite did, she was coming home from the river feeling and looking as blue as a lobelia, when a car stopped beside her.

“Hallo, Harriet. How are you getting on?”

Harriet had been so deep in gloom because she was cold and tired that she had not noticed the car, but as he spoke she saw Dr Phillipson, who ordered the fresh air, and quite suddenly everything she had been thinking about cotton-wool legs and fresh air and not going to school came over her in a wave and she did what she would never have done in the ordinary way, she told the doctor exactly what she thought of his treatment.

“How would you be if you were made to walk up and down a river in almost winter, all by yourself, getting colder and colder, and bored-er and bored-er, with absolutely nothing to do, and not allowed to stop indoors for one minute because you’d been ill and your doctor said you’d got to have fresh air? I feel simply terrible, and I shouldn’t think I’ll ever, ever get well again.”

The doctor was a nice, friendly sort of man and clever-looking. Usually he was too busy to do much talking, but this time he seemed in a talking mood. He opened the door of his car and told Harriet to hop into the seat beside him, he had got a visit or two to do and then he would take her home.

“I must say,” he agreed, “you do look a miserable little specimen; I hoped you’d pick up after that convalescent home the hospital sent you to.”

Harriet looked at him sadly, for she thought he was too nice to be so ignorant.

“I don’t see why I should have got better at that convalescent home.”

“It’s a famous place.”

“But it’s at the top of a cliff, and everything goes on at the bottom of the cliff, sea-bathing and the sands and everything nice like that. I could never go down because my legs were too cotton-woolish to bring me back.”

The doctor muttered something under his breath which sounded like “idiots”, then he said:

“Haven’t you any relations in the country that you could go and stay with for a bit?”

“No, we’ve only Uncle William; he’s only got two rooms and use of a bathroom and one of his two rooms is his kitchen. He shoots and catches and grows the things Daddy sells in the shop. Mummy says it’s a pity he wouldn’t have room for me because he eats all the best things, so all that food would do me good, but I don’t think it would because I’m not very hungry.”

The doctor thought about Harriet’s father’s shop and sighed. He could well believe Uncle William ate the best of everything for the shop looked as if he did. All he said was:

“You tell your father and mother I’ll be along to have a talk with them this evening.”

Since she had been ill Harriet was made to go to bed at the same time as Edward, which was half-past six. This was a terrible insult, because Edward was only just seven, whereas she was nearly ten, so when Dr Phillipson arrived, only Alec and Toby were up. The Johnsons lived over the shop. There was not a great deal of room for a family of six. There was a kitchen-dining room, there was a sitting room, one bedroom for the three boys, a slip of a room for Harriet and a bedroom for George and Olivia. When Dr Phillipson arrived Olivia was in the kitchen cooking the things George had not sold, Alec and Toby were doing their homework at one side of the table in the sitting room, while on the other side their father tried to work out the accounts. The days when their father did the accounts were bad days for Alec’s and Toby’s homework, because accounts were not their father’s strong point.

“Alec, if I charge ninepence each for four hundred cabbages, and twopence a pound for four dozen bundles of carrots, three and sixpence each for eight rabbits, and thirty shillings for miscellaneous fish, and we’ve only sold a quarter of the carrots, half the cabbages, one of the rabbits, and all the fish but three, but we’ve made a very nice profit on mushrooms, how much have I earned?”

Toby, who was eleven and had what his schoolmaster called a mathematical brain, was driven into a frenzy by these problems of his father’s. He was short-sighted, and had to wear spectacles, and a piece of his sandy-coloured hair was inclined to stand upright on the crown of his head. When his father asked questions about the finance of the shop, his eyes would glare from behind his spectacles, and the piece of hair on the crown of his head would stand bolt upright like a guardsman on parade. He would be in such a hurry to explain to his father that he could not present a mathematical problem in that form that his first words fell out on top of each other.

“But-Father-you-haven’t-told-Alec-the-price of the mushrooms on which the whole problem hangs, nor the individual prices of the fish.”

It was in the middle of one of these arguments that Olivia brought Dr Phillipson in. In spite of having to cook all the things Uncle William sent which would not sell, Olivia succeeded in looking at all times as if she was a hostess entertaining a very nice and amusing house party. In the kitchen she always wore an overall but underneath she had pretty clothes; they were usually very old because there was seldom money for new clothes, but she had a way of putting them on and of wearing them which seemed to say, “Yes, isn’t this pretty? How lucky I am to have nice clothes and time to wear them.” As she ushered Dr Phillipson into the sitting room it ceased to be full of George, Alec and Toby all arguing at the tops of their voices, and of Alec’s and Toby’s school books, and George’s dirty little bits of paper on which he kept his accounts, and she was showing a guest into a big, gracious drawing room.

“Dr Phillipson’s come to talk to us about Harriet.”

The Johnson children were properly brought up. Alec and Toby jumped to their feet murmuring, “Good evening, sir,” and Alec gave the doctor a chair facing George.

The doctor came straight to the point.

“Harriet is not getting on. Have you any relations in the country you could send her to?”

George, though he only had two, offered the doctor a cigarette.

“But of course, my dear fellow, my brother William has a splendid place, love to have her.”

The doctor was sure George would not have many cigarettes so he said he preferred to smoke his own. Olivia signalled to Alec and Toby not to argue.

“It’s quite true, Dr Phillipson, my brother-in-law William would love to have Harriet, but unfortunately he has only got two rooms, and he’s very much a bachelor. All my relations live in South Africa. We have nowhere to send Harriet or, of course, we would have sent her long ago.”

The doctor nodded, for he felt sure this was true. The Johnsons were the sort of people to do almost more than was possible for their children.

“It’s not doing her any good hanging about by the river at this time of year.”

Toby knew how Harriet felt.

“What she would like is to go back to school, wouldn’t she, Alec?”

Alec was very like his mother; he had some of her elegance and charm, but as well he had a very strongly developed strain of common sense. He could see that Harriet in her present daddy-long-legs stage was not really well enough for school.

“That’s what she wants, but she’s not fit for it, is she?”

“No, she needs to exercise those legs of hers. Do they do gymnasium or dancing at her school?”

“Not really,” said Olivia. “Just a little ballroom dancing once a week and physical exercises between classes, you know the sort of thing.”

The doctor turned to George.

“Would your finances run to sending her to a dancing school or a gymnasium? It would have to be a good one where they knew what they were doing.”

George cleared his throat. He hated that kind of question, partly because he was a very proud father who wanted to give his children every advantage, and who, except when he was asked direct questions by doctors, tried to pretend he did give them most advantages.

“I don’t think I could manage it just now. My father left me a bit, and Olivia will come into quite a lot some day, but just now we’re mainly dependent on the shop, and November’s a bit of an off-season. You see, my brother William…” His voice tailed away.

The doctor, who knew about the shop, felt sorry and filled in the pause by saying “Quite.” Then suddenly he had an idea.

“I’ll tell you what. How about skating? The manager of the rink is a patient of mine. I’ll have a word with him about Harriet. I’m sure he’d let her in for nothing. There’d be the business of the boots and skates, but I believe you can hire those.”

Alec nodded.

“You can. I think skating’s a good idea. If you can get your friend to give her a pass we’ll manage the boots and skates.”

The doctor got up.

“Good. Well, I’ve got to go and see the manager of the rink tomorrow; I’ll have a word with him; if he says yes I’ll arrange to pick Harriet up and drop her off and introduce her to him. It’s no distance, she could have a lot of fun there, plenty of kids, I imagine, go, it’s a big, airy place and she can tumble about on the ice and in no time we’ll see an improvement in those leg muscles.”

George showed the doctor to the door. While he was out of the room Olivia said in a whisper:

“Alec, whatever made you say it would be all right about the skates and boots? What do you suppose they cost?”

Toby answered.

“We know what it cost because we went that time Uncle William packed that goose by mistake. They’re two shillings a session.”

Olivia never lost her air of calm, but she did turn surprised eyes on Alec. He was usually the sensible, reliable one of the family, not at all the sort of person to say they could manage two shillings a day when he knew perfectly well they would be hard put to it to find threepence a day. Alec gave her a reassuring smile.

“It’s all right. I’ll find it, there’s a lot of delivering and stuff will want doing round Christmas and in the meantime I saw a notice in old Pulton’s window. He wants a boy for a paper round.”

Olivia flushed. It seemed to her a miserable thing that Harriet’s skates and boots had to be earned by her brother instead of by her father and mother.

“I wonder if I could get something to do? I see advertisements for people wanted, but they always seem to be wanted at the same time as I’m wanted here.”

Alec laughed.

“Don’t be silly, Mother, you know as well as I do you couldn’t do any more than you do.”

Toby had been scowling into space; now he leant across to Alec.

“How much do you suppose boots and skates cost? If a profit can be made on hiring out a pair of boots and skates at two shillings a session, how much would it cost to buy a second-hand pair outright?”

Alec was doodling on his blotting paper.

“With what?”

At that moment George came back.

“Nice fellow Phillipson, he says this skating will be just the thing for Harriet. It’s this skates’ and boots’ money that’s worrying me. Do you suppose we could do any good if we opened a needlework section, Olivia?”

He was greeted by horrified sounds from Olivia, Alec and Toby. Olivia got up and put her arms round his neck.

“I adore you, George, but you are an unpractical old idiot. You haven’t yet educated the public to come to you for trout, and be prepared at the same time to buy a bag of half-rotten apples, so how do you think you’re going to lure them on to supposing they would also like six dusters and an overall?”

Alec looked up from his doodling.

“What sort of needlework did you mean, Dad?”

George looked worried.

“Certainly not dusters and overalls. I seem to remember my grandmother doing some very charming things, fire-screens I believe they were.”

Olivia laughed.

“I’m not much of a needlewoman, and I can promise you even if I were to start today it would be two years before you would have even one fire-screen, so I think you can count the needlework department out.”

Alec put a bundle of newspapers under the arm of the figure he was doodling.

“It’s all right, Dad, I’m going to tide us over to start with by a newspaper round. Old Pulton wants somebody.”

Toby had been doing some figures on paper.

“If a newspaper boy is paid two shillings an hour, reckoning one hour in the morning and one hour in the evening daily for six days, with one hour on Sunday at double time, how long would it take him to earn second-hand boots and skates at a cost of five pounds?”

Alec said:

“If a boy and a half worked an hour and a half for a skate and a half…”

Olivia saw Toby felt fun was being made of a serious subject.

“I’m afraid,Toby, you’re going to grow up to be a financier, one of those people who goes in for big business with a capital ‘B’.”

Alec finished his drawing.

“It wouldn’t be a bad thing, we could do with some money in our family. If you were thinking, Toby, I might get Mr Pulton to advance five pounds for my services, it wouldn’t work because I might get ill or something and you’re too young to be allowed to do it.”

“That’s right, darling,” Olivia agreed. “It wouldn’t be practical anyway to buy boots because Harriet’s growing, and probably the moment Alec had bought her the boots they’d be too small. Feet grow terribly fast at her age, especially when you’ve been ill. I wonder if she’s awake?”

George got up.

“I’ll go and see. If she is I’ll bring her down. It’ll cheer her up to know what’s planned for her.”

Harriet was awake, and so was Edward. Edward was the good-looking one; his hair was not sandy like the rest of his family, but bright copper, his eyes were enormous with greenish lights in them. Strangers stopped to speak to Edward in the road just because they liked looking at him, and Edward took shameless pleasure in his popularity.

“It’s disgusting,” Alec often told him. “You’re a loathsome show-off.”

Edward was always quite unmoved, and merely tried to explain.

“I didn’t ask to be good-looking, but I like the things being good-looking gives me. I was the prince in the play at school.” Toby, when he heard that, had made noises as if he were being sick. “All right, make noises if you like, but I did like being the prince. There was special tea afterwards, for the actors, with ices.”

“But you can’t like people cooing and gurgling at you,” Toby always protested.

Edward seemed to consider the point.

“I don’t know. There’s you and Alec off to school and nobody knows you’ve been, and nobody cares. There’s me walks up the same street and everybody knows. I think it’s duller to be you.”

“It’s no good,” Alec would say to Toby, “wasting our breath on the little horror.”

“Just a born cad,” Toby would agree.

But Edward was neither a horror nor a cad, he was just of a very friendly disposition, a person who liked talking and being talked to. Already, although he had only been seven for one month, he had a good idea of the sort of people he liked talking to and the sort of people he did not. He was explaining this to Harriet when George came up to fetch her.

“It’s those silly sort of ladies with little dogs I don’t like, and people like bus conductors I do like.”

George went into Edward’s room.

“You’re supposed to be asleep, my son. Turn over and I’ll tuck you in. I’m taking Harriet downstairs.”

Edward sat up.

“What for? She’s supposed to be in bed and asleep too.”

George pushed Edward down.

“We’ve got something to tell her.” He could feel Edward rising up under his hand to protest that he would like to be told too. “Not tonight, old man, I dare say Harriet’ll tell you tomorrow.”

It was a cold night, so George not only made Harriet put on her dressing-gown but he rolled her up in an eiderdown and carried her down to the sitting room. Harriet was surprised to find herself downstairs. She looked round at her family with pleasure.

“Almost it’s worth being sent to bed with Edward to be got up again and brought downstairs. What did Dr Phillipson say?”

Olivia thought how terribly thin Harriet’s face looked, sticking out of a bulgy eiderdown. It made her speak very gently.

“He wants you to take up skating, darling.”

Nothing could have surprised Harriet more. She had been prepared to hear that she was to go for rides on the top of a bus, or do exercises every morning, but skating was something she had never thought about. George stroked her hair.

“Dr Phillipson is arranging for you to get in free.”

Alec said:

“So the only expense will be the hiring of your skates and boots, and that’s fixed.”

Toby looked hopefully at Harriet for some sign that she was working out the cost of skates and boots, but Harriet never worked out the cost of anything. She just accepted there were things you could afford and things you could not.

“When do I start?”

Olivia was thankful Harriet seemed pleased.

“Tomorrow, darling, probably, but you aren’t going alone, the doctor’s going to take you.”

Harriet tried to absorb this strange turn in her affairs. She knew absolutely nothing about skating; then suddenly a poster for an ice show swam into her mind. The poster had shown a girl in a ballet skirt skating on one foot, the other foot held high above her head, her arms outstretched. Thinking of this picture Harriet was as startled as if she had been told that tomorrow she would start to be a lion tamer. Could it be possible that she, sitting on her father’s knee rolled in an eiderdown, would tomorrow find herself standing on one leg with the foot of the other over her head? These thoughts brought her suddenly to more practical matters.

“What do I wear to skate, Mummy?”

Olivia mentally ran a distracted eye over Harriet’s wardrobe. She had grown so long in the leg since her illness. There was her school uniform, but that wanted letting down. There were her few frocks made at home. There was the winter party frock cut down from an old dinner dress which had been part of her trousseau. Dimly Olivia connected skating and dancing.

“I don’t know, darling, do you think the brown velvet?”

Harriet thought once more of the poster.

“It hasn’t got pants that match, and they would show.”

“She must match,” said Toby. “She’ll fall over a lot when she’s learning.”

Olivia got up.

“I must go and get our supper. I think tomorrow, darling, you must just wear your usual skirt and jersey; if you find that’s wrong we’ll manage something else by the next day.”

George stood up and shifted Harriet into a carrying position.

“Come up to bed, Miss Cecilia Colledge.”

Harriet’s skating ceased to be a serious subject and became funny. Olivia, halfway to the kitchen, turned to laugh.

“My blessed Harriet, what is Daddy calling you? It’s only for exercise, darling.”

Alec drew a picture of Harriet on his blotting paper: she was flat on her back with her legs in the air. Under it he wrote, “Miss Harriet Johnson, Skating Star.”

Toby gave Harriet’s pigtails a pull.

“Queen of the Ice, that’s what they’ll call you.”

George had a big rumbling laugh.

“Queen of the Ice! I like that. Queen of the Ice!”

Harriet wriggled.

“Don’t laugh, Daddy, it tickles.”

But when she got back to bed Harriet found that either the laughing or the thought of skating next day had done her good. Her legs were still cotton-woolish but not quite as cotton-woolish as they had been before her father had fetched her downstairs. Queen of the Ice! She giggled. The giggle turned into a gurgle. Harriet was asleep.

Chapter Two MR PULTON (#ulink_7e184e94-1add-5c98-abed-b82a4b24c70d)

ALEC CALLED ON Mr Pulton after supper. Mr Pulton had been born over the newspaper shop and so had his father before him, and likely enough rows of grandfathers before that. Nobody could imagine a time when Pulton’s newsagents had not been a landmark in the High Street. By luck, or because Pulton’s did not hold with meddling, the shop looked as if it had been there a long time. It was a little, low shop with a bow-fronted window, and there were the remains of some old bottle glass in one pane. Nobody knew Mr Pulton’s Christian name, he had always been just Mr Pulton to speak to, and C. Pulton when he signed his name. There was a lot of guessing as to what the C. stood for; local rumour had decided it was Carabas, like the marquess who was looked after by Puss in Boots. There were old men who were at school with Mr Pulton, who ought to have known his name, but they only remembered he had been called Pip Pulton. This was so unlikely a name for Mr C. Pulton that nobody believed the old men, and said they were getting on and had forgotten. It was true they were getting on, for anyone who had been at school with Mr Pulton was rising eighty.

Alec went to Mr Pulton’s back door for the shop was closed. He knocked loudly for Mr Pulton was a little deaf. After a moment there was a shuffling, grunting, wheezing sound, and Mr Pulton opened the door. He was a very thin, very pale man. His hair was white, and so was his face, which looked as if it had been a face for so long that the colour had been washed out of it, and it had been battered around until it creased and was full of wrinkles. His hands were pale too, long and thin and spidery; he wore clothes that nobody had ever seen anyone else wear; a little round brown velvet cap with a tassel hanging down on one side and a brown velvet coat and slippers embroidered with gold and silver thread. His paleness and thinness sticking out of the brown skull cap and brown velvet coat made him look like a delicate white moth, caught in a rough brown hand. There was, however, nothing delicate or mothlike about Mr Pulton’s mind; that was as quick and as tough as a lizard. This showed in his extraordinarily blue, interested, shrewd eyes. His voice was misleading for it matched his body and not his mind. It was a tired voice, which sounded as if it had been used such a lot that it was wearing away. Mr Pulton looked at Alec and his eyes showed he was remembering who he was, and anything that he knew about him.

“What can I do for you, young man?” Alec explained that he had come about the paper round. There was a long pause, not a pause of tiredness but a pause in which Alec could feel Mr Pulton was considering his paper round, and whether he was the sort of boy who could be trusted to deliver papers without bringing dishonour to Pulton’s Newsagents. Evidently his thoughts about Alec were nice, for suddenly he said a very surprising thing. “Come inside.”

Alec had never been inside Mr Pulton’s house before, and neither, as far as he knew, had anybody else. He had often wanted to go inside, because leaning across the counter waiting for his father’s paper he had sometimes seen glimpses of a back room, which seemed to be full of interesting things. Now he was inside the room and he found it even more interesting than he had thought it might be. It was a brownish kind of room, so evidently Mr Pulton was fond of brown. There were brownish curtains, and brownish chair covers, and brownish walls. There was a gay fire burning, but in spite of it the room was dark because Mr Pulton had not yet got around to electric light, and could not be bothered with lamps, so he lit his home with candles, which gave a queer, dim, flickering light. In spite of the dimness Alec could see the room was full of pictures, and the pictures were all of horses, which was amazing, for nobody had ever thought of Mr Pulton as being interested in horses. There were dozens of portraits of horses: race-horses, hunters, shire horses, almost every sort of horse. As well on the top of a bookcase, on brackets and on tables there were bronze models of horses. It seemed such a very horse sort of room that Alec thought it would not be rude to mention it.

“I say, what a lot of horses, sir.”

Mr Pulton picked up a candle. He walked slowly round his walls, his voice took on a proud, affectionate tone, though it still kept its frail, reed-like quality.

“Old Jenny, foaled a Grand National winner, she did. There he is, his portrait was painted the day after, so my father heard, you can see he was proud; look at him, knows he’s won the greatest test of horse and rider ever thought of. That’s Vinegar, beautiful grey, went to a circus, wonderfully matched greys they were. Now there’s a fine creature, you wouldn’t know what he was – Suffolk Punch. It takes all sorts to make up a horse’s world, just as it takes all sorts to make our world; Suffolk Punches are country folk, simple in their ways, not asking much nor wanting changes. Now there’s a smart fellow: Haute École they call that, see his feet? That’s fine work, that is, takes a clever horse for High School.” He paused by a bronze cast of a horse which was standing on a small table. He ran his hand over the back of the cast as if it were alive. “You were a grand horse, weren’t you, old fellow? My grandfather’s he was; used to hunt him, he did. My father used to say you were almost human, didn’t he? Whisky his name was; clever, couldn’t put a foot wrong. And how he loved it. Why, there’s mornings now, especially at this time of year, when there’s a nip of frost in the air, and the smell of dropped leaves, I can fancy old Whisky here raising his head, and I can see a look in his eye as if he were saying ‘What’s keeping us? Wonderful morning for a hunt, let’s be off.’”

Alec was so interested in the horses and the little bits of their history that Mr Pulton let drop, that he forgot the paper round, and it was quite a surprise to him when Mr Pulton, holding up his candle so that he could see Alec’s face clearly, said:

“Why do you want my paper round? Not the type.”

“Why not? I’m honest, sober and industrious.”

Mr Pulton chuckled.

“Maybe, but you haven’t answered my question. Why do you want my paper round?”

Alec, though privately he thought Mr Pulton was a bit inquisitive, decided he had better explain.

“Well, sir, it’s to hire boots and skates for my sister Harriet, who’s been ill and…”

Mr Pulton held up a finger to stop Alec.

“Sit down, boy, sit down. At my age you feel your legs, can’t keep standing all the time. Besides, I’ve got my toddy waiting in the fireplace. You like toddy?… No, course you wouldn’t. If you go through that door into my kitchen, and open the cupboard, you’ll see in the left-hand corner a bottle marked ‘Ginger wine’. Nothing like ginger wine for keeping out the cold.”

Alec went into the kitchen; it was a very neat, tidy kitchen, evidently whoever looked after Mr Pulton did it nicely. He found the cupboard easily, and he brought the bottle of ginger wine and a glass back to the sitting room. Mr Pulton nodded in a pleased way, and pointed to the chair opposite his own.

“Sit down, boy… sit down… help yourself. Now tell me about your sister Harriet.”

Mr Pulton was an easy man to talk to; he sat sipping his toddy, now and again nodding his head, and all the time his interested blue eyes were fixed on Alec. When Alec had told him everything, including how difficult it was to make the shop pay because of Uncle William eating so much, and how Dr Phillipson thought he could get Harriet into the rink for nothing, he put down his glass of toddy, folded his hands, and put on the business face he wore in his paper shop.

“How much does it cost to hire boots and skates?”

“Two shillings a session.”

Mr Pulton gave an approving grunt, and shook himself a little as if he was pleased about something.

“Morning and evening rounds. Good. The last boy I had would only do mornings, no good in that, never get into my ways. I pay ten shillings a week for the morning round, and four shillings for the evening round; there’s not so much work in the evenings, mostly they buy their papers from a newsboy on the street, nasty, dirty habit. Never buy papers from newsboys. You can have the job.”

Alec was reckoning the money in his head. Harriet would only go to one session of skating a day, that meant for six days, for there would be no skating on Sunday, which would cost twelve shillings. That would give him two shillings over for himself. Two shillings a week! Because of Uncle William’s mixed and irregular supplies to the shop, it was scarcely ever that he had any pocket money, and the thought of having two whole shillings a week made his eyes shine far brighter than Mr Pulton’s candles.

“Thank you, sir. When can I start?”

“Tomorrow. You said your sister was starting skating tomorrow. You’ll be here at seven and you’ll meet my present paper boy, he’ll show you round. You look pleased. Think you’ll like delivering papers?”

Alec felt warm inside from ginger wine, and outside from the fire, and being warm inside and out gives a talkative feeling.

“It’s the two shillings. You see, Harriet will only need twelve shillings for her skates, and you said fourteen.”

Mr Pulton had picked up his hot toddy again.

“That’s right. What are you going to do with the other two shillings?”

In the ordinary way Alec would not have discussed his secret plan, the only person who knew it was Toby; but telling things to Mr Pulton was like telling things to a person in a dream; besides, nobody had ever heard Mr Pulton discuss somebody else’s affairs, indeed it was most unlikely that he was interested in anybody’s affairs.

“I’ve no brains. Toby has those, but Dad and Mother think I’ll go on at school until I’m eighteen, but I won’t, it’s a waste of time for me, at least that’s what I think. I’d meant to leave school when I was sixteen, and go into something in Dad’s line of business. You see, it’s absolutely idiotic our depending on Uncle William. Dad doesn’t see that, but of course he wouldn’t for he’s his brother, but you can’t really make a place pay when for days on end you get nothing but rhubarb and perhaps a couple of rabbits, and one boiling hen, and then suddenly thousands of old potatoes. You see, Uncle William just rushes out and sends off things he doesn’t like the look of, or has got too many of. Now what I want to do is to get a proper set-up. I’d like a pony and cart to go to market and buy the sorts of things customers want to eat. What we sell now, and everybody knows it, isn’t what customers want but what Uncle William doesn’t want. I think knowing that puts people off from buying from Dad.”

Mr Pulton leant back in his chair.

“It’d take a lot of two shillings to buy a pony and trap.”

“I know, but I might be able to do something as a start. You see, if I put all the two shillings together, by next spring I’d have a little capital and I could at least try stocking Dad with early potatoes or something of that sort. We never sell new potatoes, Uncle William likes those, so we only get the old ones. If the potatoes went well I might be able to buy peas, beans, strawberries and raspberries in the summer.”

“You never have those either?”

“Of course not, Uncle William hogs the lot.”

“You’d like to own a provision store some day?”

“Glory no! I’d hate it. What I want is to be at the growing end; I’d give anything to have the sort of set-up Uncle William’s got. There’s a decent-sized walled fruit and vegetable garden, where you could do pretty well if you went in for cloches, and there’s a nice bit of river and there’s some rough shooting.”

“How does your Uncle William send his produce to your father?”

Alec looked as exasperated as he felt.

“That’s another idiotic thing, we never know how it’s coming. Sometimes he has a friend with a car, and we get a telephone message, and Dad has to hare up to somebody’s flat to fetch it; mostly it comes by train, but sometimes Uncle William gets a bargee to bring it down; that’s simply awful because the stuff arrives bad, and Uncle William can’t understand that it arrived bad.”

Mr Pulton had finished his toddy, and he got up.

“I am going to bed. Don’t forget now, seven o’clock in the morning. Not a minute late. I can’t abide boys who come late.” He was turning to go when evidently a thought struck him. He nodded in a pleased sort of way. “Stick to your dreams, don’t let anyone put you off what you want to do. All these…” he swept his hand round the horses, “were my grandfather’s and my great grandfather’s, just that hunter belonged to my father. When I was your age I dreamed of horses, but there was this newsagency, there’s always been a Pulton in this shop. Where are my dreams now? Goodnight, boy.”

Chapter Three THE RINK (#ulink_f5442371-db25-5b95-877d-4124239a0df1)

OLIVIA WENT TO the rink with Harriet, for the more Harriet thought about the girl on the poster, standing on one skate with the other foot high over her head, the more sure she was that she would be shy to go alone to a place where people could do things like that. Dr Phillipson was very kind, but he was a busy, rushing, tearing sort of man, who would be almost certain merely to introduce her to the manager by just saying, “This is Harriet,” and then dash off again. This was exactly what happened. Dr Phillipson called for Harriet and her mother just after lunch, took them to the rink, hurried them inside into a small office in which was a tired, busy-looking man, said, “This is Harriet, and her mother. Mrs Johnson, Harriet, this is Mr Matthews, the manager of the rink. I’ve got a patient to see,” and he was gone.

Olivia took no time to make friends with Mr Matthews. She heard all about something called his duodenal ulcer, which was why he knew Dr Phillipson, and all about how Dr Phillipson had taken out his wife’s appendix, and of how Dr Phillipson had looked after his twin boys, who were grown up now and married, and only when there were no more illnesses left in the Matthews’ family to talk about did Olivia mention skating.

“Dr Phillipson tells me you’re going to be very kind and let Harriet come here to skate. He wants her to have exercise for her leg muscles.”

Mr Matthews looked at Harriet’s legs in a worried sort of way.

“Thin, aren’t they? Ever skated before?” Harriet explained she had not. “Soon pick it up, I’ll show you where you go for your skates and boots. Cost two shillings a session they will.” He turned to Olivia. “I’ll have a word with my man who hires them out, ask him to find a pair that fit her; he’ll keep them for her, it’ll make all the difference.”

The way to the skate-hiring place was through the rink. Harriet had never seen a rink before. She gazed with her eyes open very wide at what seemed to her to be an enormous room with ice instead of floor. In the middle of the ice, people, many of whom did not look any older than she was, were doing what seemed to her terribly difficult things with their legs. On the outside of the rink, however, there were a comforting lot of people who seemed to know as little about skating as she did, for they were holding on to the barrier round the side of the rink as if it was their only hope of keeping alive, while their legs did the most curious things in a way which evidently surprised their owners. In spite of holding on to the barrier quite a lot of these skaters fell down and seemed to find it terribly difficult to get up again. Harriet slipped her hand into her mother’s and pulled her down so that she could speak to her quietly without Mr Matthews hearing.

“It doesn’t seem to matter not being able to skate here, does it, Mummy?”

Olivia knew just how Harriet was feeling.

“Of course not, pet. Perhaps some day you’ll be as grand a skater as those children in the middle.”

Mr Matthews overheard what Olivia said.

“I don’t know so much about that, takes time and money to become a fine skater. See that little girl there.”

Harriet followed the direction in which Mr Matthews was pointing. She saw a girl of about her own age. She was a very grand-looking little girl wearing a white jersey, a short white pleated skirt, white tights, white boots, and a sort of small white bonnet fitted tightly to her head. She was a dark child with lots of loose curly hair and big dark eyes.

“The little girl in white?”

“That’s right, little Lalla Moore, promising child, been brought here for a lesson almost every day since she was three.”

Olivia looked pityingly at Lalla.

“Poor little creature! I can’t imagine she wanted to come here when she was three.”

Mr Matthews obviously thought that coming to his rink at the age of three brought credit on the rink, for his voice sounded proud.

“Pushed here in a pram, she was, by her nanny.”

“I wonder,” said Olivia, “what could have made her parents think she wanted to skate when she was three.”

Mr Matthews started walking again towards the skate-hiring place.

“It’s not her parents, they were both killed skating, been brought up by an aunt. Her father was Cyril Moore.”

Mr Matthews said “Cyril Moore” in so important a voice that it was obvious he thought Olivia ought to know who he was talking about. Olivia had never heard of anybody called Cyril Moore but she said in a surprised, pleased tone:

“Cyril Moore! Fancy!”

At the skate-hiring place Mr Matthews introduced Olivia and Harriet to the man in charge.

“This is Sam. Sam, I want you to look after this little girl; her name is Harriet Johnson, she’s a friend of Dr Phillipson’s, and, as you can see from the look of her, she has been ill. Find boots that fit her and keep them for her, she’ll be coming every day.”

Sam was a cheerful, red-faced man. As soon as Mr Matthews had gone he pulled forward a chair.

“Sit down, duckie, and let’s have a dekko at those feet.” He ran a hand up and down Harriet’s calves and made disapproving, clicking sounds. “My, my! Putty, not muscles, these are.”

Harriet did not want Sam to think she had been born with flabby legs.

“They weren’t always like this, it’s because they’ve been in bed so long with nothing to do. It seems to have made them feel cotton-woolish, but Dr Phillipson thinks if I skate they’ll get all right again. I feel rather despondent about them myself, they’ve been cotton-woolish a long time.”

Sam took one of Harriet’s hands, closed it into a fist and banged it against his right leg.

“What about that? That’s my spare, that is, the Japs had the other in Burma. Do you think it worries me? Not a bit of it. You’d be surprised what I can do with me old spare. I reckon I get around more with one whole leg and one spare than most do with two whole legs. Don’t you lose ’eart in yours; time we’ve had you on the rink a week or two you’ll have forgotten they ever felt like cotton-wool, proper little skater’s legs they’ll be.”

“Like Lalla Moore’s?”

Sam looked surprised.

“Know her?”

“No, but Mr Matthews showed her to us, he said she’d been skating since she was three. He said she used to come in a perambulator.”

Sam turned as if to go into the shop, then he stopped.

“So she did too, had proper little boots made for her and all. I often wonder what her Dad would say if he could come back and see what they were doing to his kid. Cyril Moore he was, one of the best figure skaters, and one of the nicest men I ever set eyes on. Well, mustn’t stop gossiping here, you want to get on the ice.”

“Mummy, isn’t he nice?” Harriet whispered. “I should think he’s a knowing man about legs, wouldn’t you? He ought to know about them, having had to get used to having one instead of two.”

The boots, with skates attached, that Sam found were new. He explained that new boots were stiffer and therefore would be a better support to Harriet’s thin ankles. Sam seemed so proud of having found her a pair of boots that were new and a fairly good fit that Harriet tried to pretend she thought they were lovely boots. Actually she thought they were awful. Lalla Moore’s beautiful white boots had made Harriet hope she was going to wear white boots too, but the ones Sam put on her were a nasty shade of brown, with a band of green paint round the edge of the soles. Sam was not deceived by her trying to look pleased.

“’ired boots is all right, but nobody can’t say they’re oil paintings. If you want them stylish white ones you’ll have to buy your own. We buy for hard wear, you’d be surprised the time we make our boots last. Besides, nobody can’t make off with these.”

Olivia looked puzzled.

“Does anyone want to?”

“You’d be surprised, but they don’t get away with it. If Harriet here was to walk out with these someone would spot the green paint and be after her quicker than you could say winkle.”

Olivia laughed.

“I can’t see Harriet walking out in these. I’m going to have a job to get her to the rink.”

Sam finished lacing Harriet’s boots. He gave the right boot an affectionate pat.

“Too right you will. I wasn’t speaking personal, I was just explaining why the boots look the way they do.” He got up. “Good luck, duckie, enjoy yourself.”

If Olivia had not been there to hold her up Harriet would never have reached the rink. Her feet rolled over first to the right, and then to the left. First she clung to Olivia, and then lurched over and clung to a wall. When she came to some stairs that led to the rink it seemed to her as if she must be killed trying to get down them. The skates had behaved badly on the flat floor, but walking downstairs they behaved as if they had gone mad. She reached the bottom by gripping the stair rail with both hands while Olivia held her round her waist, lifting her so that her skates hardly touched the stairs. Olivia was breathless but triumphant when they got to the edge of the rink.

“Off you go now. I’ll sit here and get my breath back.”

Harriet gazed in horror at the ice. The creepers and crawlers who were beginners like herself clung so desperately to the barrier that she could not see much room to get in between them. Another thing was that even if she could find a space it was almost certain that one of the creepers and crawlers in front or behind her would choose that moment to fall over and knock her down at the same time. As a final terror, between the grand skaters in the middle of the rink and the creepers and crawlers round the edge, there were the roughest people. They seemed to go round and round like express trains, their chins stuck forward, their hands behind their backs, with apparently no other object than to see how fast they could go, and they did not seem to mind who they knocked over as they went. Gripping both sides of an opening in the barrier Harriet put one foot towards the ice and hurriedly took it back. This happened five times. Olivia was sympathetic but firm.

“I’m sorry, darling, I’d be scared stiff myself, but it’s no good wasting all the afternoon holding on to the barrier and never getting on to the ice. Be brave and take the plunge.”

Harriet looked as desperate as she felt.

“Would you think I’d feel braver if I shut my eyes?”

“No, darling, I think that would be fatal, someone would be bound to knock you down.”

It was at that moment that Olivia felt a tap on her shoulder. She turned round. Behind her sat an elderly lady looking rather like a cottage loaf. She wore a grey coat and skirt which bulged over her chest to make the top half of the loaf, and over her tail and front to make the bottom half. On her head she wore a neat black straw hat; she was knitting what looked as if it would be a jersey, in white wool.

“If you’ll wait a moment, ma’am, I’ll signal to my little girl, she’ll take her on to the ice for you.”

“Isn’t that kind! Which is your little girl?”

The lady stood up. Standing up she was even more like a cottage loaf than she had been when she was sitting down. She waved her knitting.

“She’s not really mine, I’m her nurse.”

From the centre of the ring the waving was answered. Harriet nudged her mother.

“Lalla Moore.”

Lalla cared nothing for people who went round pretending they were express trains, or for creepers and crawlers; she came flying across the rink as if she were running across an empty field.

“What is it, Nana?”

“This little girl, dear.” Nana turned to Harriet. “You won’t have been on the ice before, will you, dear?”

Harriet was gazing at Lalla.

“No, and I don’t really want to now. The doctor says I’ve got to, it’s to stop my legs being cotton-wool.”

Nana looked at Harriet’s legs wearing an I-thought-as-much expression.

“Take her carefully, Lalla, don’t let her fall.”

Lalla took hold of Harriet’s hands. She moved backwards. Suddenly Harriet found she was on the ice.

“You’ll have to try and straighten your legs a little, because then I can tow you.”

Harriet’s knees and ankles hadn’t been very good at standing straight on an ordinary floor since she had been ill, but in skates and boots it was terribly difficult. But Lalla had been skating for so long she could not see anything difficult about standing up on skates, and, because she did not find anything difficult about it, Harriet began to believe it could not be as difficult as it looked. Presently, Lalla, skating backwards, had towed her into the centre of the rink.

“There, now I’ll show you how to start. Put your feet apart.” With great difficulty Harriet got her feet into the sort of position that Lalla wanted. “Now lift them up. First your right foot. Put it down on the ice. Now your left foot. Now put it down.”

Nana, having asked Olivia’s permission to do so, had moved into the seat next to her. First of all they discussed Harriet’s illness and her leg muscles. Then Olivia said:

“Mr Matthews pointed out your child to us. I hear she’s been skating since she was a baby; you used to push her here in a perambulator, didn’t you?”

Nana laid her knitting in her lap. She could hear from Olivia’s tone she thought it odd teaching a baby to skate.

“So I did too, and I didn’t like it. I never have held with fancy upbringing for my children, and I never will.”

“But her father was a great skater, wasn’t he?”

“He was Cyril Moore. But maybe your father was a great preacher, ma’am, but that isn’t to say you want to spend all your life preaching.”

Olivia laughed.

“My father has a citrus estate in South Africa, and I’ve certainly never wanted to spend all my life growing oranges and lemons.”

“Nor would her father have wanted skating as a baby for Lalla. Bless him, he was a lovely gentleman and so was her mother a lovely lady.”

“What happened to them?”

“Well, he was the kind of gentleman that must always be doing something dangerous. He only had to see a board up saying ‘Don’t skate, danger’ and he was on the ice in a minute. That’s how he went, and poor Mrs Moore with him. Seems he was on a pond; they say there was a warning out the ice wouldn’t bear, but anyway they both popped through it, and were never seen alive again.”

“Oh, dear, what a sad story, and who is bringing little Lalla up?”

Nana’s voice took on a reserved tone.

“Her Aunt Claudia, her father’s only sister.”

“And she was the one who decided to make a skater of her?”

“It’s a memorial, so she says. Lalla wasn’t two years old the winter her parents popped through that thin ice. I’ll never forget it, Aunt Claudia moved into the house, and the very first thing she did was to have a glass case made for the skates and boots her father was drowned in. She put it up over my blessed lamb’s cot.‘With all respect ma’am,’ I said,‘I don’t think it’s wholesome, we don’t want her growing up to brood on what’s happened.’ And do you know what she said? ‘He’s to live again in Lalla, Nana, he was a wonderful skater, but Lalla is to be the greatest skater in the world.’”

Olivia, enthralled with the story, had forgotten about Harriet. She turned now to look at the two children.

“I don’t know whether she’s going to be the greatest skater in the world, but she certainly seems to be a wonderful teacher. Look at my Harriet.”

Nana was silent a moment watching the two children.

“We’ll call them back in a minute. Harriet shouldn’t be at it too long, not the first time. They say Lalla’s coming on wonderfully, she’s got her bronze medal, you know, and she isn’t quite ten.”

Olivia had no idea what a bronze medal was for but she could hear from Nana’s tone it was something important.

“Isn’t that splendid!”

“It’s a funny life for a child, and not what I expect in my nurseries. She has to do so much time on the ice every day, so she can’t go to school or anything like that; governesses and tutors she has as well, of course, as being coached here every day by Mr Lindblom.”

“It must cost a terrible lot of money.”

“Well, what with what her parents left her, and her Aunt Claudia marrying a rich man, there’s enough.”

“She has got a step-uncle, has she?”

Nana was knitting again; she smiled at the wool in a pleased way.

“Yes, indeed. Her Uncle David. Mr David King he is, and as nice a gentleman as you could wish to find, I couldn’t ask for better.”

Olivia was glad to hear that Lalla had a nice step-uncle because somehow, from the tone of Nana’s voice, she was not certain she would like her Aunt Claudia. However, it was not fair to make up her mind about somebody she had never met, and anyway probably Lalla enjoyed the skating.

“I expect the skating’s fun for her, even if she has to miss school and have governesses and tutors because of it.”

“She enjoys it well enough, bless her, I’m not saying she doesn’t, but it’s not what I would choose in a manner of speaking.” Nana got up. “I’m going to signal the children to come off the ice, for, if you don’t mind my mentioning it, your little Harriet has done more than enough for the time being; she better sit down beside me and have a glucose sweet the same as I give my Lalla.”

The moment she sat down Harriet found her legs were much more cotton-woolish than they had been before. They felt so tired she did not know where to put them, and kept wriggling about. Nana noticed this.

“You’ll get used to it, dearie, everybody’s legs get tired at first.”

Olivia looked anxiously at Harriet.

“Perhaps that had better be all for today, darling.”

Harriet was shocked at the suggestion.

“Mummy! Two whole shillings’ worth of hired boots and skates used up in quarter of an hour! We couldn’t, we simply couldn’t.”

“It can’t be helped if you’re tired, darling. It’s better to waste part of the two shillings than to wear the poor legs out altogether.” Olivia turned to Nana. “I’m sure you agree with me.”

Nana had a cosy way of speaking, as if while she was about nothing could ever go very wrong.

“That’s right, ma’am. More haste less speed, so I’ve always said in my nurseries.” She smiled at Harriet. “You sit down and have another glucose sweet and presently Lalla will take you on the ice for another five minutes. That’ll be enough for the first day.”

Lalla looked pleadingly at Nana.

“Could I, oh, could I stay and talk to Harriet, Nana?”

Nana looked up from her knitting.

“It’ll mean making the time up afterwards. You know Mr Lindblom said you was to work at your eight-foot one.”

Lalla laughed.

“One foot eight, Nana.” She turned to Harriet. “Nana never gets the name of the figures right.”

Nana was quite unmoved by this criticism.

“Nor any reason why I should, never having taken up ice skating nor having had the wish.”

“Harriet would never have taken up ice skating, nor had the wish either,” said Olivia, “if it hadn’t been for her legs. I believe two of my sons came here once, but that’s as near as the Johnsons have ever got to skating.”

Lalla was staring at Olivia with round eyes.

“Two of your sons! Has Harriet got brothers?” Harriet explained about Alec, Toby and Edward. Lalla sighed with envy. “Lucky, lucky you. Three brothers! Imagine, Nana! I’d rather have three brothers than anything else in the world.”

Nana turned her knitting round and started another row.

“No good wishing. If you were to have three brothers, you’d have to do without a lot of things you take for granted now.”

“I wouldn’t mind. I wouldn’t mind anything. You know, Harriet, it’s simply awful being only one, there’s nobody to play with.”

Olivia felt sorry for Lalla.

“Perhaps, Nana, you would bring her to the house sometime to play with Harriet and the boys; it isn’t a big house, and there are a lot of us in it, but we’d love to have her and you, too, of course.”

“Bigness isn’t everything,” said Nana. “Some day, if the time could be made, it would be a great treat.”

Harriet looked with respect at Lalla. Even when she had gone to school she had always had time to do things. She could not imagine a life when you had to make time to go out to tea. Lalla saw Harriet’s expression.

“It’s awful how little time I get. I do lessons in the morning, then there is a special class for dancing or fencing, then, directly after lunch, we come here and, with my lesson and the things I have to practise, I’m always here two hours and sometimes three. By the time I get home and have had tea it’s almost bedtime.”

Olivia thought this a very sad description of someone’s day who was not yet ten.

“There must be time for a game or something before bedtime, isn’t there? Don’t you play games with your aunt?”

Lalla looked surprised at the question.

“Oh no, she doesn’t play my sort of games. She goes out and plays bridge and things like that. When I see her we talk about skating, nothing else.”

“She’s very interested in how Lalla’s getting on,” Nana explained, “but Lalla and I have a nice time before she goes to bed, don’t we, dear? Sometimes we listen to the wireless, and sometimes, when Uncle David and Aunt Claudia are out, we go downstairs and look at that television.”

Olivia tried to think of something to say, but she couldn’t. It seemed to her a miserable description of Lalla’s evenings. Nana was a darling, but how much more fun it would be for Lalla if she could have somebody of her own age to play with. She was saved answering by Lalla.

“Are your legs better enough now to come on the rink, Harriet?”

Harriet stretched out first one leg and then the other to see how cotton-woolish they were. They were still a bit feeble, but she was not going to disgrace herself in front of Lalla by saying so. She tottered up on to her skates. Lalla held out her hands. “I’ll take you to the middle of the rink but this time you’ll have to lift up your feet by yourself, I’m not going to hold you. Don’t mind if you fall down, it doesn’t hurt much.”

Olivia watched Harriet’s unsteady progress to the middle of the rink.

“How lucky for her that she met Lalla. It would have taken her weeks to have got a few inches round the edge by herself. She’s terrified, poor child, but she won’t dare show it in front of Lalla.”

Nana went on knitting busily; her voice showed that she was not quite sure she ought to say what she was saying.

“When I get the chance I’ll have a word with Mrs King about Harriet, or maybe with Mr King, he’s the one for seeing things reasonably. It would be a wonderful thing for Lalla if you would allow Harriet to come back to tea sometimes after the skating. It would be such a treat for her to have someone to play with.”

“Harriet would love it, but I am afraid it is out of the question for some time yet. I’m afraid coming here and walking home will be about all she can manage. The extra walk to and from your house would be too much for her at present.”

“There wouldn’t be any walking. We’d send her home in the car. Mrs King drives her own nearly always, and Mr King his own, so the chauffeur’s got nothing to do except drive Lalla about in the little car.”

Olivia laughed.

“How very grand! I’m afraid I’ll never be able to ask you to our house. Three cars and a chauffeur! I’m certain Mrs King would have a fit if she saw how we lived.”

“Lot of foolishness. Harriet’s a nice little girl, and just the friend for Lalla. You leave it to me. Mrs King has her days, and I’ll pick a good one before I speak of Harriet to her or Mr King.”

Walking home Olivia asked Harriet how she had enjoyed skating. She noticed with happiness that Harriet was looking less like a daddy-long-legs than she had since her illness started.

“It was gorgeous, Mummy, but of course it was made gorgeous by Lalla. I do like her. I hope her Aunt Claudia will let me go to tea. Lalla’s afraid she won’t, and she’s certain she won’t let her come to tea with us.”

“You never know. Nana says she has her days, and she’s going to try telling her about you on one of her good days.”

Harriet said nothing for a moment. She was thinking about Lalla, Nana, and Aunt Claudia, and mixed up with thinking of them was thinking about telling her father, Alec, Toby and Edward about them. Suddenly she stood still.

“Mummy, mustn’t it be simply awful to be Lalla? Imagine going home every day with no one to talk to, except Nana, who knows what’s happened because she was there all the time. Wouldn’t you think to be only one like Lalla was the most awful thing that could happen to anybody?”

Olivia thought of the three cars and the chauffeur, and Lalla’s lovely clothes, and of the funny food they had to eat at home, and the shop that never paid. Then she thought of George and the boys, and the fun of hearing about Alec’s first day on the paper round, and how everybody would want to know about Harriet’s afternoon at the rink. Perhaps it was nicer to laugh till you were almost sick over the queer shop-leavings you had to eat, than to have the grandest dinner in the world served in lonely state to two people in a nursery. She squeezed Harriet’s hand.

“Awful. Poor Lalla, we must make a vow, Harriet. Aunt Claudia or no Aunt Claudia let’s make friends with Lalla.”

Chapter Four LALLA’S HOUSE (#ulink_9c6f69bd-3152-57d9-aa23-fa01bd0eb964)

LALLA’S HOUSE WAS the exact opposite of Harriet’s house. It was not far away, but in a much grander neighbourhood. It was a charming, low, white house lying back in a big garden, with sloping lawns leading down to the river. Where the lawn and the river joined there was a little landing stage, to which, in the summer, Lalla’s Uncle David kept his motor launch tied. Lalla’s rooms were at the top of the house. A big, low room looking over the river, which had been her nursery, was now her schoolroom, and another big room next to it, which had been her night nursery, was now her bedroom. As well there was a room for Nana and a bathroom. Her bedroom was the sort of bedroom that most girls of her age would like to have. The carpet was blue and the bedspread and curtains white with wreaths of pink roses tied with blue ribbons on them, and there was a frill of the same material round her dressing-table. The only ugly thing in the room was the glass case over her bed in which the skates and boots in which her father was drowned were kept. The nicest skating boots in the world are not ornamental, and these, although they had been polished, looked as though someone had been drowned in them, for the black leather had got a brownish-green look. Underneath the case was a plaque which Aunt Claudia had put up. It had the name of Lalla’s father on it, the date on which he was born, and the date on which he was drowned, and underneath that he was the world’s champion figure skater. Above the case Aunt Claudia had put some words from the Bible: “Go, and do thou likewise.” This made people smile for it sounded rather as if Aunt Claudia meant Lalla to be drowned. Lalla did not care whether anybody smiled at the glass case or not, for she thought it idiotic keeping old skates and boots in the glass case, and knew from what Nana had told her that her father and mother would have thought it idiotic; in fact she was sure everybody thought it idiotic except Aunt Claudia.

The schoolroom, which Lalla sometimes forgot to call the schoolroom and called the nursery, was another very pretty room. It had a blue carpet and blue walls, lemon-yellow curtains and lemon-yellow seats to the chairs, and cushions to the window seats. It still had proper nursery things like Lalla’s rocking-horse and dolls’ house, and a toy cupboard simply bulging with toys, but as well it had low bookcases, full of books, pretty china ornaments, good pictures and a wireless set. The only things which did not go with the room were on a shelf which ran all down one wall; this was full of the silver trophies that her father had won. It is a very nice thing to win silver trophies, but a great many of them all together do not look pretty; the only time Lalla liked the trophies was at Christmas, because then she filled them with holly, and they looked gay. Although every trophy and medal had her father’s name on it, where he had won it, what for, and the date on which it had been won, Aunt Claudia was afraid Lalla might forget to read the inscriptions, which was sensible of her because Lalla certainly would not have read them, so underneath the whole length of the shelf was a quotation from Sir Walter Scott altered by Aunt Claudia to fit a girl by changing “his” and “him” into “her”. “Her square-turn’d joints and strength of limb, Show’d her no carpet knight so trim, But in close fight a champion grim.” When Aunt Claudia came to the nursery she would sometimes read the lines out loud in a very grand acting way. She hoped hearing them said like that would inspire Lalla to further effort, but all it did was to make Lalla decide that she would never read any book by Sir Walter Scott. Sometimes Lalla and Nana had a little joke about the verse; Lalla would jump out of her bed or her bath and fling herself on Nana saying “Her square-turn’d joints and strength of limb” and then she would butt Nana with her head and say “That butt never came from a carpet knight, did it?”

On the day that Lalla met Harriet she and Nana had an exceptionally gay tea. Nana had let Lalla do what she loved doing, which was kneeling by the fire making her own toast, instead of having it sent up hot and buttered from the kitchen, which meant the top slice had hardly any butter on it because it had run through to the bottom one. They talked about Harriet and the rink, Lalla in an excited way and Nana rather cautiously. Lalla laughed at Nana and said she was being “mimsy-pimsy” and asked if it was because she didn’t like the Johnsons. Nana shook her head.

“I liked them very much, dear; Mrs Johnson’s a real lady, as anyone can see, and little Harriet, for all she’s so shabby, has been brought up as a little lady should. But I don’t want you to go fixing your heart on having her here. You know what it is, your Aunt Claudia has got strict ideas of who you should know, and I don’t think, if she was to see Harriet, she would think she was your sort, not having the money to live as you do.” Nana could see this was going to make Lalla angry, so she added:“Now don’t answer back, dear, you know I’m speaking sense. I don’t think it matters about what money a person has, no more than you do, but your aunt’s your guardian, and she sets great store by money, and you know you’ve been brought up never to want for anything, so you must be a good girl and not mind too much if you’re not allowed to have Harriet here.”

“But I want to go to Harriet’s house. I want to be in a family.”

“I dare say, but maybe want will have to be your master. The one that pays the piper calls the tune, and the piping in this house is done by your Aunt Claudia, and you know it.”

Nana had only just finished saying this when the door opened and Aunt Claudia walked in. Nana was swallowing a sip of tea, and she was so upset at Aunt Claudia having so narrowly missed hearing what she had said that she choked. Lalla thought this funny and began to giggle. Aunt Claudia did not like either choking or giggling, and her voice sounded as though she did not. She was a very nice-looking aunt in a hard sort of way. She had fair hair that looked as if it had been gummed into place, because there was never one hair out of order; her face was always beautifully made up, so that cold winds, hot weather, even colds in the head, never made any difference to it. She wore beautiful, expensive clothes and lovely jewels. Although she felt annoyed to find Nana choking and Lalla giggling, she did not let it show on her face, because she knew that made wrinkles. The only place where it showed was in her blue eyes, which had a sparkish look.

“Good evening, Nurse. Can’t you control that noise, Lalla, I don’t think you should find it funny when Nurse is choking.” She waited till Nana’s last choke died away, and Lalla had stifled her giggles. “I don’t seem to have seen you all the week, and I’ve got a few minutes before I go out, so I thought I’d hear how your skating is progressing. Have you mastered the one foot eight?”

Lalla was not being very quick at the one foot eight because she was not trying hard enough.

“It’s not right yet, at least not right enough for Mr Lindblom, but I’m working at it, aren’t I, Nana?”

Nana was glad that after Harriet had gone she had sent Lalla back to work at that figure. It would have been difficult for her to sound convincing if what she could remember was Lalla holding up Harriet while Harriet lifted first one foot and then the other off the ice.