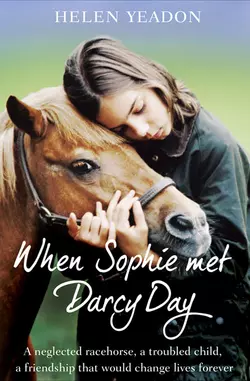

When Sophie Met Darcy Day

Helen Yeadon

A heartwarming collection of stories from a woman who brings together disadvantaged children and abandoned racehorses, with remarkable results.Thirteen-year-old Sophie hadn’t uttered a word to anyone for over two years when she got out of her parents car at a remote farm in Devon. Her parents were beside themselves with worry, and at the end of their tether, but try as they might, nothing seemed to make a difference. They’d heard about a place called Greatwood through friends - where owners Helen and Michael Yeadon looked after retired racehorses - and decided to take Sophie along for a visit.Helen asked Sophie to help her change the dressings on the infected cuts on the legs of Darcy Day, one of their more troubled horses, and it was instantly clear that these two had some kind of special connection. Darcy Day would normally back away from people, but this time she lowered her head and stepped forward, to let Sophie stroke her nose. It was the start of an incredible relationship that would transform both horse and child, and it gave Michael and Helen an idea.They registered as a charity, moved to bigger premises, and began inviting children with a wide range of learning disabilities to volunteer to help with the animals. The results were amazing - traumatised horses and anxious or disturbed children bonded with each other, and every week little miracles were happening before their eyes.Boys with diagnoses such as Asperger’s Syndrome or Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, or those who’d been excluded from school for unruly behaviour, flourished through the discipline of working on the farm. Girls made timid and anxious by abusive backgrounds or school bullies came out of the shells. In this book are twenty of the most incredible tales of children who were given back their futures by the unique and extraordinary institution of Greatwood.

HELEN YEADON

WITH GILL PAUL

When Sophie MetDarcy Day

To Michael

Contents

Cover (#uf0836af2-df36-5492-aa55-1cdec11c55a5)

Title Page (#uca7b8edf-7ae3-5dbd-b0b1-85954d47a62d)

Foreword

Chapter 1 - A New Life in Devon

Chapter 2 - Moving to Greatwood Farm

Chapter 3 - Flat Broke

Chapter 4 - Lucy and Freddy

Chapter 5 - Sophie and Darcy Day

Chapter 6 - Moving to Wiltshire

Chapter 7 - Edward Joins the Team

Chapter 8 - Bobby and Bob

Chapter 9 - Henry and Potentate

Chapter 10 - Mark and Toyboy

Chapter 11 - Zoe and Sunny

Chapter 12 - Different Ways of Communicating

Chapter 13 - The Baptism of Fire

Chapter 14 - A Fear of Men

Chapter 15 - Ben and Leguard Express

Chapter 16 - Mary and Tim

Chapter 17 - The Importance of Food

Chapter 18 - School Phobia

Chapter 19 - Dealing with Bullies

Chapter 20 - Paul and Just Jim

Chapter 21 - Further along the Autism Spectrum …

Chapter 22 - Different Kinds of Challenges

Chapter 23 - Greatwood Expands

Chapter 24 - Amy and Monty

Find out more about Greatwood

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Foreword

Sophie was a puzzle. At first glance she was a slightly dumpy girl in her early teens who wore baggy, unflattering clothes and wouldn’t make eye contact with anyone. Her posture was slumped, as if she were trying to make herself as small as possible to avoid being noticed. That was unremarkable in a girl of her age, but the most unusual thing about Sophie was that she hadn’t spoken for over two years. Not to anyone.

And no one could work out why. Her school work was suffering, she had no social life and her parents were at a loss to know what to do.

One day they brought her to Greatwood, the Devon farm where my husband Michael and I looked after retired racehorses.

‘I hear you let local children help out with the animals,’ her mother said. ‘I don’t suppose we could leave Sophie with you for a couple of hours to see how she gets on? She’s always liked horses.’

‘Of course,’ I said. There was so much to be done that we were always grateful for another pair of hands.

I was just on my way to change the dressings on a horse called Darcy Day, who’d arrived a few days earlier in a very poorly condition. She had painfully swollen, infected legs, diarrhoea, and she was drastically underweight, with her bones sticking out through a dull, matted coat. We spoke kindly to her, trying to get some kind of response, but her eyes were glazed, her head hanging. She was depressed and withdrawn. She’d lost interest in everything and everybody. We put her in a stable and she slunk to the back of it, not moving when I carefully arranged a rug over her, and not even attempting to sniff the fresh hay I placed nearby.

As we walked to the stable that morning, I explained to Sophie what was wrong with Darcy, and said that she needed very special care and attention while we tried to get her on the road to recovery. Her feed and medication needed constant monitoring and the bandages on her legs had to be changed regularly. Michael joined us in case I needed an extra pair of hands to hold her while I positioned the dressings. The three of us opened the stable door and walked in, and something quite remarkable happened. Darcy pricked up her ears, looked straight at Sophie, then turned and walked over towards her. As she got close, she lowered her head.

Michael and I looked at each other in astonishment. ‘That’s amazing,’ I exclaimed. ‘Look, Sophie – she’s come to say hello to you. She wants you to stroke her nose.’

Sophie stretched out a tentative hand to touch her.

‘It’s extraordinary,’ I remarked. ‘I bring her feed to her but she completely ignores me. You’re the first person she’s shown any interest in.’

A smile was twitching at the corners of Sophie’s mouth. She gently stroked Darcy’s nose.

‘She obviously likes you,’ Michael added, and Sophie gave a proper smile, just a quick one.

It was the beginning of a relationship that would change both Sophie’s and Darcy’s lives, although we weren’t to know it at the time.

We stood and watched for a moment, then we started laying out the bandages, soft wrap and ointments necessary to dress Darcy’s legs. With twenty horses, two goats, four dogs, umpteen chickens and a few unruly geese to look after, there was never any time to spare.

Chapter 1

A New Life in Devon

Most people plan their lives. They choose the area in which they live because it’s close to where they work, or to good schools for their kids, or because they’ll be near family and friends. They plan their careers, buy houses they can afford based on their salaries, and even book their annual holidays in advance. My husband Michael and I have never operated that way. More or less everything that has happened to us over the last twenty years has been the result of coincidence, or a reaction to circumstances. It has often felt as if we were being propelled in a certain direction and we just went with the flow. Perhaps the most significant feature of the Great-wood story is that it simply evolved.

For instance, we moved to Devon in 1993 largely because of an idyllic fishing trip. It was a hot day in June, the lazy river glinted in the sunlight and a wildflower meadow stretched into the distance. The only sound was the buzzing of insects and my father sucking on his pipe. I don’t fish myself but the beauty of the landscape was so intoxicating that I turned to Michael and said, ‘We should move down here.’

At the time we lived in the Cotswolds, where we ran a small hotel. While it was rewarding at first, we’d been getting fed up with the relentless drudgery, and an inheritance from Michael’s Aunt Gladys meant we could afford to change direction. Michael loved to write and had been working for a couple of years on a children’s story, which I had illustrated. If we sold our hotel in the Cotswolds and bought a place in Devon, we’d have enough money in the bank to keep us going for a couple of years until we decided what we wanted to do with our lives. And if we found a big enough place, Michael’s elderly and increasingly frail mother could live in an annex, where we could keep an eye on her.

My reverie was interrupted by a yell, followed by a loud braying sound. Dad had lifted his fishing line out of the water and flicked it backwards in a long, languid cast. Michael shouted too late to warn him that some heifers had sidled up behind us and a cow complained loudly as it was hooked solidly in the rump. The heifers charged off across the field, dragging Dad’s reel behind them, and we all chased after them like the cast of a Laurel and Hardy movie, with Michael and me trying to grab the recalcitrant cow and hold it still long enough for Dad to extricate his hook.

It was a warning of things to come, a message about the trouble animals can bring into your life. Maybe we should have listened. But we didn’t.

After much searching, we found a house we both liked, near Dartmoor. What sold it to us was a stunning five-foot-wide solid oak door with iron studding, which led into a small porch with oak seating and a tiny room above with a diamond-paned window. The door and the porch were probably worth more than the rest of the house and the garden put together. The property was surrounded by fields on all sides, and there were several outbuildings we could renovate. That was the good news. The downside was the carnage left by previous attempts at modernisation: concrete floors, orange and green painted beams, and the obligatory 1970s avocado bathroom suite. Undeterred, we moved in, along with our four Jack Russells, and began to do it up to our own taste, sourcing original Devon slate for the floors and ripping out the ancient plumbing.

The barns were over-run by cats and kittens, some of them feral, all in pretty bad shape. Michael’s daughter Clare (one of his five grown-up children) had come to help, so she and I set about rounding up these cats in order to take them to the Cat Protection League, where they could be spayed, wormed and eventually re-homed. We caught fifteen of them altogether, and ended up covered in scratches and bites, but we knew they would have a much better future with the charity than they would have had in our barns, where they were interbreeding and relying on whatever food they could catch. And we were better off without them as well, we mused, as we applied antiseptic and bandages to our wounds.

However, Michael and I are animal lovers. I grew up on a farm in Wiltshire and Michael had previously owned racehorses, so animals have always been a part of our lives. Once we found ourselves in a country setting with barns and fields, it was only a matter of time before we started filling them. Nature abhors a vacuum, so they say.

Walking down a lane near the house one day, Michael and I heard a pathetic bleating sound and peered under a hedge to see a goat tethered to a trailer. She was white, with pricked ears, and her rope had become tangled round the wheels of the trailer so she couldn’t reach her water bucket. Our neighbour, George, appeared round the corner.

‘Is that your goat?’ I asked.

‘Bloody nuisance, she is,’ he exclaimed. ‘My daughter brought her home, but unless we keep her tied up she runs off and eats everything she can reach in the garden, and some of the plants are poisonous. She seems to have some sort of homing device because every time my wife plants something a bit special, she immediately finds and demolishes it.’

I knew nothing at all about goats but I felt this one deserved more of a life than she had at present, grazing on a bare patch of earth and weeds attached to a rope that was just a few feet long.

‘I’ll probably have to send her to market,’ George added.

Michael and I looked at each other. There was something about this funny little goat that captivated me. As I watched her try to unwind the tangled tether she gazed up at me with an anxious bleat, asking me to help. She seemed quite smart. ‘I think she’s great, but it’s a shame she can’t enjoy a bit of freedom.’

Michael glanced at me with a weary expression. He knew what was coming.

‘She should be able to run around instead of being tied up.’

George raised an eyebrow, clearly deciding that we were ‘up-country’ folk with romanticised rural notions who might just be stupid enough to take on this troublesome creature. By this time I’d made my way through the hedge and was stroking the goat’s head.

‘I s’pose I could let you have her, if you want,’ he mused. ‘Course she did cost us a bit o’ money. ’Spect you wouldn’t mind giving us a tenner to make up for the loss.’

Michael reached into his trouser pocket and pulled out a crumpled tenner, and George untethered the goat, whose name, it transpired, was Angie, and handed me the rope.

‘There you go,’ he said, and I think we caught the sound of a cackle as he disappeared off down the lane.

We looked at Angie and she looked up at us expectantly, then we took her down to her new home, where she lost no time in befriending the dogs. In fact, before long she was behaving just like a dog: coming when we called her name, joining us all for walks, and wandering into the house when she felt like it. She stole bread in the kitchen if we were foolish enough to leave it lying out, and she was even found upstairs in the bedroom a few times, nosing about amongst my clothes.

Next we decided we really should have a few hens – just enough to provide us with fresh eggs. We went to a livestock auction in Hatherleigh, the nearest village, but our lack of experience at auctions such as these told against us and we kept accidentally buying the scrawny, pecked hen in the cage next to the white silky one we’d had our eye on. Just the slightest twitch of the hand and I found myself the not-so-proud owner of yet another straggly specimen. Once the hammer had gone down, it was far too late to admit that I had bid for the wrong hen. Thereafter it was a little disconcerting to realise that the auctioneer always looked across at me when a particularly bedraggled specimen was held up to auction, waiting for my bid.

Flirty Gertie was definitely an accidental purchase. She was one of the ugliest hens you’ve ever seen, with dull grey feathers, a damaged eye and an extremely loud voice, especially if anything didn’t meet her approval. She didn’t lay eggs on a regular basis but she liked human contact and would always rush up to greet us, and she was happy to be lifted and cuddled. One of her special talents was stowing away in the back of the Land Rover when we were going out. Once, when Michael was in a bakery in Jacobstowe, he looked out the window to see Flirty Gertie holding up traffic as she pecked in the road outside, having hopped out of the back of the vehicle. Another time, she appeared in the churchyard as we were emerging from a service and it took most of the congregation chasing around in their Sunday-best clothes to recapture her. She was finally trapped in the church porch by the organist’s wife, who expertly hurled her best Sunday hat in such a way that it covered Gertie almost completely, and we could pick her up with relative ease.

So we had four dogs, umpteen scruffy hens, a goat and Michael’s mother all living with us. Michael’s children frequently came to visit, and we settled down to enjoy life in our new home. At no time had we ever discussed getting horses. We’d both grown up with horses and loved them but we knew what a huge commitment they required, in terms of both time and money. But then we met a woman called Pam in the local pub. She had bred horses all her life and had a yearling for which she was keen to find a home.

‘We’ll come and have a look,’ I said, ‘but only out of curiosity. We need a horse like we need a hole in the head.’

Poppy was a chestnut filly with huge brown eyes and a white blaze down her face. She had a wild, feisty expression and there was something about her that made me cautious. She was pretty but she was going to take some work. Was this really something I wanted to take on?

‘I think we should have her. How much do you want for her?’ Michael asked, and I turned to him, open-mouthed in disbelief. Whatever happened to discussion and consensus?

I realised my instincts about Poppy were correct as soon as we got her home, when she bolted out of the trailer. As I was attempting to lead her into the field we both ricocheted up the lane from one side to the other. She was clearly wilful and hadn’t had a lot of handling and, as I had originally suspected, it would probably take a while to teach her some manners. We had problems every time we moved her from barn to field and back again, but I’d had a lot of experience in dealing with youngsters and because she was quick and clever she soon began to understand the ground rules. However, she had a temper if things didn’t go her way, and we had many a battle of wills.

I have never liked to see animals on their own, and Poppy needed some company. On a hunch, I decided to put Angie the goat in the same field to see how they got on, and after a bit of mutual sniffing and nudging, they became instant best pals. Angie showed Poppy how to clamber up steep banks to eat blackberries from the bush. It was fascinating watching a horse delicately pluck a ripe fruit from its bed of thorns. Their mouths aren’t precise enough and she got a few scratches on her nose but that didn’t seem to deter her. The two quickly became inseparable and, ironically, the goat who used to give George so much trouble that he kept her tethered to a trailer was able to help teach our wilful horse some manners.

Despite my initial reservations about keeping horses, Poppy rekindled my childhood love of them. I’d ridden from the age of four, and had my first racehorse at the age of seven on Dad’s farm. We’d taken in a lot of racehorses that were retired from the racecourse and I knew how stunning these fabulous creatures were, and how exhilarating and rewarding they could be. Poppy was too young to be ridden for another couple of years, so when Michael and I were offered a retired racehorse called Jelly, we thought it might be a good idea. She’d be equine company for Poppy to help in her socialisation and, what’s more, I’d be able to ride her. At least that was the idea.

When Jelly arrived, she was a reminder that things seldom go according to plan when it comes to animals. She hated being groomed, hated having her rug changed, and would shuffle and back me into a corner of the stable whenever I attempted to touch her. She was incorrigibly bloody-minded. Not only was she awkward and grumpy, but she was also a chronic crib-biter. ‘Cribbing’ is when a horse places its upper teeth on a post, arches its neck and swallows air. It is believed that this releases endorphins in the brain that help relieve stress, but horses that crib-bite fill their stomachs with air, are less likely to put on weight and have a tendency to colic. It’s highly addictive and once a horse starts doing it, you’re unlikely to be able to stop it. What’s more, it wrecks your fencing.

Whenever I took Jelly out for a hack, more often than not she would catch me unawares and dump me unceremoniously in a ditch or on top of a hedge, for no other reason except wilfulness. I would then have to wander wearily after her to try to catch her. More often than not I failed, and I’d return home to find her waiting outside her field, keen to be reunited with her pals.

‘It’s rotten luck that we’ve acquired such a bad-tempered, ungrateful mare,’ I commented to Michael. ‘She hates me and everything I try to do for her.’

‘Oh, she’s all right,’ he said. He seemed to have a soft spot for her and I couldn’t understand why.

‘Well, you muck her out and groom her every day then,’ I retorted. Michael and I don’t often argue but there are times when there is a palpable tension in the air and this was definitely one of them.

There wasn’t a specific moment when Jelly and I turned the corner, but gradually, over the next few months, she began to make me chuckle instead of frown. Every morning when I took in her breakfast, she pulled her ears back, rolled her eyes and made a horrendous face at me, but I learned to take it in my stride. ‘Same to you with knobs on,’ I’d retort. If she lifted a leg to kick me, I made a loud tutting noise and she’d stop and give me a resigned look as if to say, ‘Oh, all right, get on with whatever you have to do. Just do it as quickly as you can.’ We weren’t going to be best friends but she had decided she might as well tolerate me.

The next addition to our growing menagerie was an Angora goat called Monty, who became fast friends with Angie, and then Michael was offered a beautiful liver chestnut racehorse called Chic, who had recently been retired. She was gentle and kind – in fact, everything that Jelly was not. So there we were with four dogs, lots of scrawny chickens, two goats and three horses. It felt right to me. Despite all the work, I liked having animals around.

We were still having endless discussions about what to do with the next part of our lives. Should we convert more of the outbuildings and take in paying guests, as we had done in the Cotswolds hotel? The animals would be a unique selling point for the right kind of visitor seeking not exactly a peaceful retreat but an entertaining break amongst animals that were all strong individual characters.

The problem with this idea was that we hadn’t yet finished the renovations on the house and they were swallowing money at an alarming rate. The front door was virtually the only thing that worked properly. Making the rest of the house habitable was proving to be much more expensive than we had anticipated. Even though we were doing a lot of the work ourselves, hitherto unforeseen problems kept cropping up and resolving them made a huge hole in the budget.

Besides, did I really want to be a hotelkeeper again?

‘Helen, you’re happier around horses than you are around people,’ Michael commented, and I had to admit he was right. Maybe that was the direction to take.

Michael and I followed racing avidly, and we decided that breeding a small number of foals from selected mares, then training them before selling them to the right home, would be an interesting and rewarding project. We were off to a good start. The highest classes of racehorse are Groups 1, 2 and 3, and the ones we had already were bred from Group 2 winners.

Michael mentioned that he’d recently had a conversation with a local farmer who was trying to sell three ex-racehorses which were in foal to a stallion that was quite popular at the time. ‘Why don’t we just pop along for a quick look?’ he suggested. ‘Just for research purposes.’

Of course, any dog lover knows that you never go along to have a ‘quick look’ at a litter of puppies and come home empty-handed. The same goes for horse lovers and stud farms. And so it was that we came home with three in-foal mares, each with foals at foot. That made a grand total of six horses and three foals, with more on the way. We were running out of space and had to rent another field to accommodate them.

Meanwhile, our cash flow was beginning to look a bit ropey with all these mouths to feed. ‘Why not take on some kayed lambs?’ my father suggested. He was a down-to-earth, Yorkshire-born man who didn’t suffer fools, and he knew all there was to know about farming, so we followed his advice.

Kayed lambs are orphaned ones that can be purchased relatively cheaply, which can then be reared and sold at a profit. They’d have the added benefit of keeping the pasture in good condition. So we bought twelve lambs, rigged up a bottle-feeding system in one of the barns, and once again recruited Michael’s daughter Clare to help.

By now our lives were completely full with feeding and caring for the ever-expanding range of livestock, and scraping old paint from woodwork in our spare time. I scarcely ever had time to go out for a ride, or to walk along the pretty lanes and admire the wildflowers growing in the hedgerows. One sunny day I stood back and remembered why we had come to Devon in the first place: to enjoy its beauty, to relax and decide where we were going next, to take a bit of time out. Whatever had happened to that idea?

All the same, when I opened the door at five in the morning and walked across the yard to boil up a huge vat of barley for the feed, I often found myself humming under my breath. This was a whole lot more satisfying than making fried eggs and two rashers for human guests. It may have been unplanned, but I was blissfully happy with our unpredictable, unruly menagerie.

Chapter 2

Moving to Greatwood Farm

As luck would have it, we had just finished the renovations on the wing of the house that we had converted for Michael’s mother to live in when, sadly, she passed away. Michael and I were left with a rambling property that was far too big for the two of us but didn’t have enough land for all the animals we had acquired. The foals were growing up and needed to be weaned, and the mares would soon be due for foaling. That meant we needed more stables and it became obvious there was never going to be enough room for us all where we were. What’s more, there was a lane between the house and the outbuildings, and passing cars had to screech to a halt if Angie poked her nose through the hedge, or Poppy dragged me out for a walk. And we were overlooked on all sides by neigh-bours, so it wasn’t quite private enough for our taste.

It was a stunning house once we’d done all the renovations, and it was a shame to leave behind all the fruits of our hard labour, but it wasn’t quite right for our needs any more. We took a deep breath, sold up and moved to a new home on a nearby country estate. There we had sufficient outbuildings to stable all the horses, but the hens had to share a little brick outhouse with my deep freeze. Michael’s son Tod was bemused when I sent him to fetch a pack of frozen peas one day and he had to flick off hen droppings before bringing them into the kitchen.

‘I come to you for my fix of antibodies before the return to London life,’ he laughed, but I noticed when I served dinner later that he stared long and hard at his plate before picking up a fork.

Our breeding programme got off to a good start, and I was involved in every aspect of the foals’ upbringing. Often I was the one to check their position when the mare went into labour; one foreleg should emerge first, then the other, then the muzzle. I’d have to make sure the newborn foal could stretch up and reach its mother’s teats to get antibody-containing colostrum within the first few hours. And I’d be there for the first steps outdoors and all the major milestones of its first year of life. I hated letting them go when Newmarket sales came around. They were my babies. It was hard to hand over the responsibility to someone else, but that had been the plan. We hoped that out of our very small breeding operation we might achieve a winner or two. If they did well, that would be great, but if they didn’t we would stop. Whatever happened, we felt we had a responsibility for any life we brought into the world.

Neither Michael nor I are the kind of people who are driven to make a fortune, and it’s just as well. Belief in what we are doing has always been of primary importance, and we tend to make decisions instinctively rather than being guided by commercial logic. We both have strengths that complement the other, and together we usually seem to make the right decisions. But the day Michael went to Ascot sales on his own, with the idea of picking up another one or two well-bred mares, I should have had an inkling that the best-laid plans can go awry. He ended up coming home not with some mares but with a discarded gelding, an ex-hurdler that had never been particularly successful on the racecourse and would have been heading for the abattoir had Michael not stepped in.

‘It’s one thing raising your hand by mistake at a hen sale,’ I said caustically, ‘but to raise it deliberately at a horse sale is something else again.’

‘You would have done the same,’ he told me. ‘Just look at him.’

He was right. I would have.

Charlie was a sad-looking horse, so thin that his backbone was sticking out and we could count all his ribs, and he had the sour smell that we were to learn is characteristic of malnourished animals. What made me angriest when I looked closely was that someone had clipped him to try to smarten him up for the sale, and it must have been horribly uncomfortable for that poor horse to feel clippers running all over his sticking-out bones. It was shameful. We put some spare duvets under his rug to keep him warm, gave him a course of wormers, had him checked out by the vet and fed him carefully. Within three months of receiving this kind of care, he was a completely different horse. He was bay with white socks, good bones and a solid, dependable character. We found he was well trained and once he was healthy enough to be taken out hacking, he turned out to be a lovely horse to ride.

The transformation from the sorry creature Michael had brought home with him to this healthy, intelligent, good-natured animal was dramatic and it made us both furious to think that this young horse – only five years old – would have had no chance of a future. The meat man had actually been bidding against Michael in the auction. Within nine months we had found Charlie a new home where he settled in happily.

The last thing you should do as a breeder is take on ‘charity cases’ that drain your precious resources without contributing to the balance sheet. We kept selling our yearlings, but at the same time we could never walk away from a horse in need. We just didn’t have it in us.

One day we went to buy a new trailer at a farm that was miles from anywhere. In a field nearby, we could see three horses standing around looking dejected. One in particular looked up at us hopefully and within seconds Michael had leapt the fence to go and have a closer look.

‘Uh-oh, this is not good,’ I thought to myself. And I was right. The upshot was that the trailer wasn’t empty when we drove home later that day.

Red was a five-year-old stallion from a leading blood-line and although he wasn’t in terrible condition, he was unsettled because he had been put in a field with some mares and his instinct was to keep trying to mount them. This gave us a problem, of course, because where would we keep him that he wouldn’t be bothered by all our mares? Fortunately I found a knowledgeable horse-woman, Sandra, who lived near us and was happy to let him stay in one of her stables. After a veterinary check-up and a few weeks of intensive care, we found he was a happy and quite beautiful horse, with a deep red sheen to his coat. He didn’t like being turned out into a field for any length of time or he would panic, but he was perfect for our mares, behaved like a true gent around them, and did his job when required.

The next horse we ‘rescued’ was one that I found while I was out riding Chic. As we rode through a semi-deserted, dilapidated farmyard, Chic became uncharacteristically jumpy and unsettled, as if she knew something I didn’t. An instinct made me decide to have a peek inside a closed cob barn, and a dreadful sight met my eyes: a skinny chestnut mare was lying on a filthy bed, with some mouldy old hay in the corner beside a bucket of stale, greasy water. She had dark filthy patches on her sides from lying in her own droppings and she appeared listless, with her eyes closed, even when I spoke to her.

I had a lump in my throat as I stroked her and whispered words of comfort. It was hard to leave her there, but she obviously belonged to someone and I knew I couldn’t just steal her. Choked with emotion, I went home and told Michael about her, and within the day we’d tracked down the owner and agreed a deal for the horse, which was named Betty. I went back to the barn, slipped a bridle over her head and led her outside into the sunshine. She blinked hard, unaccustomed to the light, but let me lead her on the four-mile walk home, stopping every now and then to munch on some grass by the roadside. We put her in a stable next to Chic with a deep straw bed, and I could tell she was content by the way she settled down and closed her eyes. She knew she was safe.

It was gratifying how quickly horses transformed when they got decent care, turning from depressed, unhealthy animals into lively, happy characters in a short space of time. The more horses we rescued, though, the greater the financial burden on Michael and me. To try to make ends meet, I took a job as a chef at a nearby college, making lunch and tea for the students, and my days became completely dominated with producing food for animals and humans. I got up at five to do the animals first, then made my way to the college by seven. I’d cook until lunchtime then slip home for a few hours to do the housework and chores on the farm. At four I’d feed the horses once more, then return to the college at five to make tea for the students. Then when I got home at seven in the evening, I would tuck up the horses for the night and fall into my own bed not long after. It wasn’t ideal by any means.

Despite this extra income, we couldn’t afford to heat the whole house over the winter so we started living in our bedroom, where there was a sweet little Victorian fireplace in which we could burn coal and logs. We moved the television up there and were quite comfortable, except for the huge shock to the system when we had to use the loo or go to the kitchen to make a cup of tea. As soon as I left the bedroom, the Arctic air chilled me to the bone, and it took ages to get warm again afterwards.

It wasn’t long before we felt that we were perhaps outstaying our welcome on that country estate. Despite our best efforts, the horses had been nibbling at the bark of a few of the trees on the parkland, which wasn’t, understandably, appreciated by the owners. We also worried about the horses being out in the fields when there was farm machinery trundling past and umpteen different people going about their business. We noticed an advertisement in the local paper for the lease of a farm near where we had rescued Betty and when we enquired we found that it was just about affordable, because of the general dilapidation of the property. In the spring of 1995, we packed up lock, stock and barrel and moved to our new home, which went by the name of Greatwood.

Greatwood Farm was set in a steep wooded valley leading down to the River Torridge, and the farmhouse was built back into the hillside. The house was damp and unloved, with peeling wallpaper and an indescribably awful bathroom, but the farmyard was stunning, with plenty of barns, outbuildings and meadows. The tall grassy banks separating the fields were covered in primroses when we arrived, and wildflowers poked out between the cobblestones in the paths. Opposite the farmhouse, a granite track led down to some watermeadows along the riverside and in summer, when the water levels were low enough, there was a ford where we could ride across to the other side. Nothing had been touched for what seemed like hundreds of years, and to us it was idyllic.

The only drawback to Greatwood was that it was on an estate where they ran a commercial pheasant shoot, but the estate owners assured us that they would always give us plenty of advance warning when a shoot was taking place so we could take the horses indoors. We didn’t want to risk them panicking and injuring themselves at the sound of gunshots.

Meanwhile our collection of horses kept growing. We were joined by Fasci, a pony with a dark coat and patchy mane, who we had seen grazing on her own in a field nearby, where she was looked after by an elderly gentleman called Peter. I never like seeing horses on their own, because they are herd animals, so I got into conversation with Peter and after a while I tentatively suggested that maybe Fasci would enjoy the company of coming to board with our lot. He agreed that she could join us, and what’s more, Peter came onboard as well, spending that summer helping us to convert the outbuildings into stables and feed sheds to house our growing menagerie in the coming winter.

We now had enough room for Red, the stallion, to come back and stay with us, and I became determined to find a pal for him to stable with. Horses aren’t usually happy without companionship. It would have to be a small gelding, I decided, with sufficient character to withstand any amorous advances from the lively Red. As luck would have it, I heard about a miniature Shetland pony called Toffee that needed a home. Would Red let a pony share his stable? It wasn’t a conventional pairing and it was with a certain amount of apprehension that we introduced them.

We were pretty confident that Red wouldn’t attack Toffee outright, but nevertheless we stood nervously by with head collars, ready to jump to the rescue if needed. For ten seconds there was silence, then Red let out a roar and tried to scoop Toffee up under his front legs. We were just about to dive in and separate them when Toffee turned, kicked out at Red with both hind legs, then began to explore the surroundings. Instantly Red’s body language changed, and he approached Toffee again with a little more respect and wariness. Toffee ignored his advances, and was clearly quite unfazed by the whole encounter, despite the fact that he was only 28 inches tall, while Red is a thundering Thoroughbred stallion of 16.2 hands (equivalent to 64.8 inches, so more than double Toffee’s height).

We continued to watch for several hours in case the mood turned nasty. Red was fascinated by Toffee now but kept a safe distance from those flying hind feet. As night drew in we decided we should separate them so we could get some sleep without worrying. We put a head collar on Toffee and started to lead him out of the door, and suddenly all hell let loose. Red threw himself around the stable, roaring and screaming, distraught at being separated from his new companion. There was nothing for it. We had to bring Toffee back and I spent a long, uncomfortable night on top of a raised platform at one end of the barn, from where I kept watch on the two of them as they snoozed down below.

The next day, when we turned them out in the field together, Red hurtled round chasing after Toffee but he was met with the same calm indignation as before and he retired sheepishly. They were getting used to each other, though, and it wasn’t long before they were firm friends. In fact, Red often started panicking if Toffee wasn’t in sight for some reason. Within a week they were inseparable.

It was the first instance of my ‘matchmaking’ at Great-wood but by no means the last. Stabling the right horses together made our jobs so much easier that it became one of the most important, and fascinating, of the challenges we faced. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t, and it wasn’t always the obvious matches that worked best.

Betty initially found the move to Greatwood disturbing, because she obviously remembered the bad experiences she’d had in that part of Devon. As we unloaded her from the trailer, she became wide-eyed, started snorting and shook from head to hoof. Thankfully, she had had time to get used to the other horses, and was especially close to Chic, a particularly calm mare, so she took the lead from her.

We’d sold the lambs but we still had our hands full tending the horses, goats, chickens and dogs, so we were more than happy when the local Sunday school started sending children to help us out at weekends. I’ve never been a kiddie-oriented person. I expect them to behave like mini-adults and treat them that way. Despite having five of them, Michael is the same. But the children who came to help at Greatwood were a terrific bunch, who were very helpful to us in mucking out, collecting eggs, sweeping the yard, grooming horses, and all sorts of other tasks. They never misbehaved because there was a certain healthy fear of the huge racehorses clopping around. They paid attention to instructions and were very careful whenever they were in the vicinity of the animals.

I was fascinated by the way the animals responded to children. Even the stroppiest of our horses, such as Jelly and Red, would greet them by lowering their noses so that the child could reach up to give them a stroke. They were careful not to stomp around when a child was in their stable, and stood still when they were being groomed. If only they’d done the same for me, life would have been a lot easier.

Several times Michael and I stood back and marvelled about how calm and gentle they were with children around.

‘Shame they’re only here at the weekends,’ I said, without any idea how prescient the remark would be.

Chapter 3

Flat Broke

During those first years in Greatwood we had about twenty horses to keep, along with goats, dogs and chickens, and our money was dwindling fast. I took a part-time job as a dinner lady at the local school, where I was shocked to find they never cooked any fresh produce – it was all ready-made meals straight from the freezer. Years before Jamie Oliver came on the scene, I battled the system and managed to get some local suppliers to deliver seasonal fruit and veg for the children, although it didn’t do me any favours with my supervisors.

My paltry earnings weren’t enough to keep us afloat, though, and gradually Michael and I began to sell off any possessions that could raise money. We got to know an antique dealer in Taunton who bought some pieces from us, including a gold bracelet my grandma had given me just before she died, and Michael’s father’s watch – both of which were very hard to part with. Even the dealer had tears in his eyes as we handed them over.

We had some inherited family silver and Michael decided to travel up to London in the hope of getting a better price for it there. He set off on the train, clutching a large holdall full of silver salvers, bowls and goblets, and made his way to a smart shop in Bond Street that we’d read about in the newspapers. He straightened his tie and brushed down his collar before walking in and placing the holdall on a counter.

‘Are you interested in buying some silver?’ he asked, unwrapping a couple of the items on top.

‘Plate,’ the man said, after a quick glance.

‘Pardon?’

‘They’re silver plate. Not solid silver.’ He picked them up and turned them over. ‘Not inscribed either. They’d have been worth more if they were.’

He made an offer for the lot that was only a fraction of what we’d thought they were worth, but with the rent overdue, and having come all that way, Michael felt he had no choice but to accept.

We didn’t tell our families about the trouble we were having but they must have realised, because every time they visited us another antique chair would be missing from the sitting room or there would be a rectangular space on the wall where a picture used to hang. My father dealt with the problem in a typical brusque farmer’s style: he gave us forty of his ewes and bought us a couple of Sussex rams to go with them.

‘Thanks, Dad,’ I said doubtfully.

He meant well, but it was then that our nightmare with sheep began. The soft, wet ground at Greatwood meant they kept getting sores and infections in their feet and needed to be rounded up daily for treatment. Some silly blighter would get its head stuck in a fence the minute you turned your back, while another would roll over and be unable to get up again. The rams were even worse. As soon as we set foot in their field they would charge at us full pelt and we had to hurl ourselves out of the way at the last minute to avoid being sent flying. Despite being a farmer’s daughter, I’d had no idea how high-maintenance sheep were. They really did seem to have a death wish, getting themselves into life-threatening situations on a daily basis.

The next money-making scheme was suggested by a chap called Stan in the local pub, who persuaded us to buy thirty goslings from the market, raise them, and sell them just before Christmas. We put them in a field to graze, not realising that they would have to be brought indoors and fattened to get them to the size customers expect of their Christmas roast. When I eventually tried to feed them up, too late in the day, they turned up their beaks and refused to eat anything at all. I had to cancel our Christmas orders and eventually passed most of them on to the Goose Rescue Centre, apart from five that we kept.

Amongst those five was Horrible Horace, a deformed goose my brother had dumped on us. Horace may have been crooked and bent, but his disability didn’t stop him flying at any children who came nearby. He thought he was a dog and would rush up to greet visitors, honk whenever the dogs barked and accompany us on walks. All our attempts to pass Horace on to other people failed, so we were stuck with yet another difficult, eccentric, bloody-minded animal to care for.

As if our financial troubles weren’t enough, word began to spread that we were prepared to step in and help with sick, temperamental or abandoned ex-racehorses. It seemed there were lots of people out there desperately trying to find a home for horses that were too old, past their prime or that hadn’t ever fulfilled their potential. Thoroughbreds need experienced handlers because many of them are unused to being ridden by anyone but a professional jockey and, what’s more, they are expensive to keep. Many of them need to be reschooled if they are ever to have a second career, but this took time, money and expertise.

Michael and I couldn’t possibly accommodate every single horse that was offered to us, but we spent hours on the telephone giving advice and trying to find potential owners for each animal, because the alternative was too awful to contemplate. For such beautiful, intelligent animals to be discarded simply because they couldn’t run fast enough was not morally acceptable.

As a farmer’s daughter I know there are hard realities to be faced in livestock breeding. My blunt Yorkshire father once said, ‘The very word “livestock” implies “deadstock” and if you can’t handle it, you’d better do something else with your life.’ But my heart always melted when a seriously ill or badly treated horse was brought to us. I could never turn them away.

In the first year at Greatwood, there was a mare called Kay whose owner hadn’t been able to afford proper medical care for her. Kay was in a lot of pain when she came to us and kept trying to kick up at her stomach. The owner said she’d tried to train her out of kicking herself but to no avail. But why was she doing it? What was the problem? I called the vet, who detected a sizeable growth in her stomach, and told me that sadly it was inoperable. There was nothing he could do. It was a horrible night, with rain lashing down and gale-force winds ripping around the barn. We had no alternative but to have Kay put down, with the other horses standing round watching. There was a collective whinny as she fell to the floor and a few came over to sniff her but most carried on eating their hay. They didn’t know her, so weren’t directly affected. As we left the barn, I felt unutterably sad for that poor horse, who’d obviously been suffering for some time. Vets’ bills are expensive. That’s why we had to be sure that when we rehomed horses, we only did so with people who could afford to keep them properly. We couldn’t risk any horses that passed through our hands ending up like Kay, or Betty, or Charlie.

Our own financial situation went from bad to worse. Each new bill was greeted with much head-scratching and the scribbling of frantic sums on the backs of envelopes, and every month rent day loomed like a sick headache. How had we got ourselves into such a pickle? The inheritance from Michael’s aunt and the money from the sale of our house had long gone, and we had very few, tiny sources of income. Then one day, I got a phone call that gave us a glimmer of hope.

‘My name’s Vivien McIrvine,’ the voice said. ‘I’m Vice President of the International League for the Protection of Horses. I’ve been hearing a lot about you and everything you are trying to do for racehorses and I wanted to tell you that I’m full of admiration for the work you’re doing.’

‘Thank you. That’s good to hear. But I’m afraid it’s just a drop in the ocean.’

We chatted for a while about the horses we had at that time, the ones looking for new homes and the ones we’d managed to rehome already, then she got to the purpose of her call.

‘The work you are doing with racehorse welfare is invaluable and rare. You must carry on and, as I see it, the only way that you can do that is if you put it on a firm footing and become a registered charity.’

Michael and I had already been considering this option but the call from an icon of horse welfare pushed us into thinking about it more seriously. It was a great compliment to hear of her admiration for our work and for a few days afterwards we mulled it all over. We knew there was a chance our application wouldn’t be successful anyway, but if it were, we’d become accountable to the charity commissioners and would have to be much more professional about the way we managed what had been, until then, an instinctive kind of operation. But we really had no choice. We had already become heavily involved in not-for-profit work on behalf of ex-racehorses by funding it all ourselves, but we couldn’t go on like that because our funds were rapidly evaporating and we would have become insolvent. That would have brought an end to our work and most certainly an end to the lives of the horses in our care.

Decision made, we started the lengthy process of applying to be a charity, which initially involved filling out an extraordinary number of forms. We were warned that the granting of charitable status could take a while – always assuming our application was approved – but it felt like a step in the right direction.

We had decided some months before this to stop breeding horses. We had only bred a dozen or so before we realised there were too many being bred that didn’t ever reach the race course, either because they weren’t fast enough or for some other reason. There was no organisation in place to care for these unwanted horses and, at that time, no one was encouraging ordinary horse owners to take on a Thoroughbred. By breeding horses, we were contributing to the problem and as soon as we became aware of this, we stopped.

In the meantime, we had four mares that were all due to foal around the same time, and umpteen ewes that were due to lamb, which meant a couple of months at least when Michael and I would have to survive on very little sleep. Fortunately we have entirely different sleep patterns. I rise early and go to bed early, while he’s the opposite, so we agreed that he would sit up with them until 2am then I’d take over from 2 until morning.

Sometimes foaling was reasonably straightforward, but when it came to Chic we were in for a marathon. She was in labour for hours, the foal wasn’t in the correct position and we had to call the vet to come and turn it. Out it came, tiny and weak, but Chic was still in labour and we realised she had a twin in there, which was eventually born dead, about the size of a cat. The first foal was very weak and didn’t have a sucking reflex so we had to tube-feed him. He was shivering with cold, so I got one of my jumpers and threaded his tiny front legs through the sleeves, then I wrapped tinfoil round his back legs to try to retain the heat. He was a poor little creature. Chic licked him gently, every ounce the loving mother.

For three days we nursed that foal day and night, and on the third day we were heartened when he managed to get to his feet and stagger a few steps on what were impossibly long legs for such a tiny chap. Chic stayed very close, watching what we were doing and letting us milk her, but she didn’t try to intervene. She knew we were doing our best. Then on the fourth day, the foal’s breathing became laboured. I sat down beside him, put his head on my lap and whispered to him gently as he passed away in my arms. There was a huge lump in my throat. He’d struggled valiantly but was just too weak to live.

I felt so sorry for Chic. She’d been good and patient, and we’d all tried our hardest, but it wasn’t to be. She kept nudging the foal’s body, trying to get it to move, so we left her with it for a few hours so she could understand he had gone.

It would have been a crying shame if no good had come out of the experience so we asked around and found out about a local foal that had lost its mother, and we took Chic over to see if she would adopt it. We used that classic country trick of skinning Chic’s dead foal and placing the skin over the live one so that Chic would believe it was her own. Chic took to the new foal with alacrity, proving to be a most diligent mother, but Michael and I were pretty sure she wasn’t fooled. She knew her foal was dead and that this was a new one, but she made the decision to adopt it anyway.

No sooner was this drama over than the sheep started lambing and we had to sit up all night long to make sure the lambs emerged safely and weren’t then attacked by rats. It brought back many memories for me of watching my father presiding over lambing at the farm where I grew up. Once when I was just three years old, I watched him pulling out a lamb that wasn’t moving and he smacked it hard several times until it began to bleat. It obviously made an impression on me because at dinner that night, I told my mum: ‘That was a naughty lamb that crawled into its mummy’s bottom and Daddy did smack it hard.’

As soon as the lambs were big enough, we sold them, along with the rest of the flock (bar two), and, unlike the horses, I was glad to see the back of them. Sheep are a law unto themselves, with very few brain cells to rub together. Give me horses every time!

All the time we were firming up and clarifying the plans for our charity. There were already organisations out there dealing with poorly treated welfare horses. We wanted to focus on horses that were retired from racing while fit in body and mind, horses that we could retrain and pass on to good homes. The charity would retain ownership of each horse so we could check up on them and bring them back if the new owners were no longer able to keep them. We chose some trustees – Father Jeremy, the vicar at St Michael’s church just four miles away from Greatwood, and Alison Cocks, the woman whose orphan foal had been adopted by Chic. She had a profound knowledge of racing and horses, and we sang from the same hymn sheet when it came to horse welfare.

Next, we had a visit from two charity commissioners – men in suits who delicately picked their way over our cobblestones trying not to get anything nasty on their highly polished leather shoes. They interviewed Michael and me at length, being particularly concerned to establish that we were in it for the long haul. We knew this was serious. The charity would have to be run properly, with full annual accounts, and we would be guardians to all of the horses that passed through our care. When the commissioners finally left, they gave us no clue either way as to whether our application would be successful.

It was several months later, in August 1998, that we finally received a letter saying that we were now a registered charity, and giving us our charity number. It was just over three years since our move to Greatwood and it seemed somehow fitting that we should name the charity after this farm, where our work with ex-racehorses really started, and where we had already achieved some notable successes.

Vivien came to help us design all the forms we would need, such as the gifting forms that would have to be filled in by anyone who sent us a horse. This was designed to avoid a scam whereby someone could bring us a horse in very poor condition, let us pay all the vet’s bills and nurse it back to health, then return to claim it back again. With our contracts, we took on a duty of care for life, and even after we rehomed a horse we had the right to check up on it at any time to inspect its living conditions and general health. If a home check didn’t come up to scratch, we’d take the horse back again. It was our responsibility.

We wanted a Greatwood logo and were delighted when a funding trust gave us a grant that allowed us to employ a marketing company to design one for us. They came up with all sorts of ideas before a chance photograph taken by a local reporter provided the inspiration. A girl called Jodie had come to us for work experience and the photo caught her in silhouette as she looked up at a Thoroughbred. The image seemed perfect and worked well for the farm sign, letterheads and business cards. Little did we suspect at the time how relevant the juxta-position of a horse and a young person would turn out to be.

Soon horses started arriving thick and fast. Sometimes the RSPCA or another official charity asked us to step in, but on other occasions individuals just arrived on our doorstep with a horse in their trailer. Once we were brought nine horses in one delivery, all of them collected from an owner who hadn’t been taking proper care of them. We had to divide up our barns with partitions to keep the mares separate from the geldings, and our workload increased all the time.

It was a life I loved, but some family members found it difficult to comprehend. My father had only recently retired from a career as a very successful farmer and he thought we were mad. ‘You’ll never get rich like that,’ was his attitude. ‘So why give yourself all that work?’

On one visit he watched me nuzzling the horses as I walked through the stable and looked thoughtful.

‘Did I ever tell you that your grandfather used to train horses for the army during the First World War?’

I vaguely remembered hearing about this, and asked for more details.

‘He was awarded a medal for bravery. Once a cart carrying munitions was hit and your grandfather wriggled out to unharness the horses pulling it, despite the fact that he was under fire.’ Dad nodded. ‘I suppose your love of horses might have come from him. That might explain it.’

I liked that thought, but in fact I think it was all the horses I grew up around that gave me love and respect for these intelligent, sensitive creatures that all have unique personalities. I learned to ride when I was four, on a pony called Tam O’Shanter, but the horse I was most in love with as a child was called Shadow. She was an exracehorse, very feisty and wilful, but such a gorgeous animal that I fell madly in love with her with all the passion of youth. I poured my heart out to her on our long rides round the estate where my family lived. There was a big ornamental lake there and Shadow loved the water, so in summer I used to let her trot in and I’d slide down off her back and hold onto her tail as she pulled me along, deeper and deeper across to the other side. She was my best friend from the age of about seven to ten. I was closer to her than to anyone else, and I have wonderful memories of our adventures together.

Michael’s elder daughter Kate has two boys, Will and Alex, and they used to come and stay with us during their school summer holidays. It was lovely to see them bonding with our horses and I always encouraged it because I wanted them to experience some of the magic I’d had as a child. If there were any foals, we let the boys name them, and they opted for several non-traditional horse names, such as Miriam, Marcus, Wilbur and Doris. No matter. I loved seeing them having fun and learning to love horses as I did.

The family complained about conditions in winter, though. It was a particularly wet part of Devon and it always seemed to be raining, meaning the yard became a sea of mud. Inside the house it was bitterly cold and hurricane drafts swept through the ill-fitting windows. Fireplaces smoked, the walls were damp, and the only way to survive was to wear umpteen woollen sweaters one on top of the other.

One year, the family came for Christmas with us and got a taste of our lifestyle that they didn’t much appreciate after a bay mare called Nellie fell ill on Christmas Eve. I knew at a glance that it was colic so we called the vet, who came out to treat her and told us to keep an eye on her overnight. Colic is a nasty thing, sometimes caused by an impaction in the gut. It can either be cured more or less instantly, or it can develop into something much more sinister. It’s important to make sure the horse doesn’t roll over, resulting in the further complication of a twisted gut. All night I walked poor Nellie up and down the lane in front of the house to try to distract her from the pain and stop her rolling but her whinnying kept everyone awake. Towards dawn, her condition deteriorated and I had to call the vet out again. We rigged up a drip to treat her in one of the stables but, despite our best efforts, she became toxic and had to be put to sleep. I was completely distraught, as well as shattered from lack of sleep.

When the children woke on Christmas morning, we had to break the news to them. I went into their room and was surprised to see clingfilm all over the windows.

‘What’s that doing there?’ I asked.

Kate explained that the bitter north-easterly wind had made temperatures drop to sub-zero and it was like trying to sleep in a draughty igloo. They didn’t want to disturb us and clingfilm was the only thing they could think of to provide a modicum of insulation.

I told them about Nellie and comforted the boys as best I could, then it was time to rush outdoors again for the morning routine of feeding and mucking out. Animals don’t know that it’s Christmas, after all. Late morning, I was sweeping the yard, trying to keep busy to stop myself brooding about Nellie, when Kate popped her head out the door.

‘Erm, Helen …?’ she asked. ‘Any idea when you’re coming in? The kids are all waiting for you so they can open their presents.’

I’d become so one-track-minded, I’d forgotten about Santa Claus and turkey and mince pies. It was a reality check. Horses are wonderful, but so are my family and it was time to find a balance between the two again.

Chapter 4

Lucy and Freddy

At around the time Greatwood became a charity in 1998, the British Racing Industry was coming to accept that it had a responsibility to put a fund in place for retired or neglected racehorses. Only around 300 of the 4,000 to 5,000 racehorses retired annually need charitable intervention, but looking after 300 Thoroughbreds a year is an expensive and labour-intensive job by anyone’s standards.

More and more stories were appearing in the press and the momentum for change was building. Carrie Humble, founder of the Thoroughbred Rehabilitation Centre in Lancashire, together with Vivien McIrvine, Vice President of the International League for the Protection of Horses, and Graham Oldfield and Sue Collins, founders of Moorcroft Racing Welfare Centre, formed part of a well-established racing group and were all influential in the decision that racing should try to help those ex-racehorses that had fallen upon hard times.

In January 1999 the British Horseracing Board Retired Racing Welfare Group was set up, chaired by Brigadier Andrew Parker Bowles, and the first meeting was held at Portman Square in London. It was quite an effort for Michael and me to get there. We lived at least an hour’s drive away from Exeter station, and from there it was the best part of three hours’ train journey to London, which meant we had to head off straight after the morning feed, long before the sun was up, but it was important that we attended come what may.

The debate was lively, to say the least. One old gent told me that in his opinion the best thing to do with ex-racehorses was shoot them. Eventually, though, a consensus was reached. Everyone at the meeting – including leading representatives from all areas of horseracing – agreed that set-ups such as ours were a vital safety net for the racing profession. In recognition of this, it was agreed that the Industry would put in place a fund to provide annual grants to accredited establishments, and Greatwood was to be one of them.

So far so good, but the details were not discussed and we didn’t know when the funding would start or how it would be administered. It was gratifying that our collective voices had at least been heard, but we were still flat out to the boards caring for the horses that were currently in our care and keeping an eye on those that we had rehomed. So in short, yes, we were pleased that our work was at last recognised but, more to the point, when would this support be forthcoming?

Our local paper started a campaign and it was picked up by some of the national media, thus helping to raise our profile, but we continued to live on a knife edge. Each horse cost £100 a week to keep and we had more than twenty in our care at any one time, which meant £2000 a week or £104,000 a year. We were so short of money that we were always just a hair’s breadth away from our overdraft limit and robbing Peter to pay Paul on a weekly basis. We stretched our credit cards to the maximum, but they wouldn’t quite cover the ongoing expenses.

During that time of great anxiety, we really valued our friendship with Father Jeremy and his wife Clarissa. She often brought groups of children to the farm to visit, and she would supply sumptuous picnics that we could all enjoy: cakes with flamboyant coloured icing topped with seasonal decorations, sausages, sandwiches, buns and home-made biscuits. There was always far too much and the leftovers would feed Michael and me for a couple of days afterwards. I suspect she planned it that way.

The horses never seemed to mind little people rushing around whooping and shrieking. Even the most nervous mares that were startled by cars would lower their heads to allow the children to stroke their noses, turning a blind eye to the general mayhem. For their part the children begged to be allowed to ride a horse and, after some consideration, we nominated Chic as the calmest, steadiest one.

Chic was still looking after Jack, her adoptive foal, but she was happy to let the children sit on her back and was careful not to move a muscle when they clustered around her feet. Whenever I climbed on her, she tended to fidget but with the kids she stood stock still. She looked after them just as well as she looked after Jack, always keeping an eye out for him no matter what else was going on.

One day I photographed Chic with several children on her back and sent a copy of the picture to Vivien Mc-Irvine, along with another photo of a group of kids who had climbed a haystack and were jumping off with unfurled umbrellas in an attempt to imitate Mary Poppins. I’d wanted her to see how well it was all going, but the very next day the phone rang.

‘Helen, what on earth do you think you are doing? Do you have any idea of the litigation that would follow if one of those kids falls and injures himself? If there’s an accident, you’d all be for the high jump!’

It shows how naïve I was back then that the possibility hadn’t even occurred to me. I thought it was great that everyone was having such a lovely time and never considered any repercussions. After that I made sure the children always wore hard hats before riding the horses, but I still let them mess around and let off steam. It had to be exciting on the farm or they wouldn’t have wanted to come.

The children came in groups of twelve to fifteen at a time, and it wasn’t all fun and games for them, because I set them to work mucking out, helping with the feeding or sweeping the yard. They didn’t seem to mind because the same few came back time after time, dropped off and picked up by their parents. One Saturday, we got a phone call from a man we knew through the church.

‘I’ve heard you have children coming to the farm to help, and I wondered if we could bring my daughter Lucy?’ he asked.

‘Of course,’ I said straight away, then added quickly, ‘What age is she?’ I didn’t want to end up babysitting for someone I’d have to take to the loo all the time.

‘Fourteen.’

‘That’s fine, then.’

He hesitated. ‘It’s just that … Lucy’s been having a bit of trouble at school. I don’t know exactly what’s going on but she doesn’t seem to have any friends and she’s unhappy. We have to drag her out the door in the morning. I thought maybe she could make some new friends at Greatwood, and be of use to you at the same time.’

My curiosity was aroused. ‘Of course she can come. I look forward to meeting her.’

An hour later, a car pulled into the yard and our friend got out along with a lanky girl with a shock of ginger hair. Her legs were so skinny her kneecaps looked like hubcaps, and when she smiled I saw her teeth were too big for her mouth. She was at an awkward age.

‘Hi, Lucy,’ I said, shaking her hand. ‘There are some other kids mucking out in that barn over there. If you’d like to join them, someone will find you a shovel.’ I didn’t believe in hanging around exchanging pleasantries while there was work to be done. ‘Don’t worry – I’ll keep an eye on her,’ I promised her dad before he drove off.

I left the children in the barn on their own for a bit, then curiosity got the better of me and I sneaked up to listen in to the conversation I could hear in snatches.

‘I know all about horses,’ I heard Lucy saying. ‘I’ve been riding since I was about two years old.’

‘No one can ride at two,’ another kid intervened.

‘Well, I did,’ Lucy said. ‘I’ve ridden lots of racehorses. There’s not a horse I can’t ride. My dad’s going to buy me a horse of my own soon. Maybe he’ll get one of the ones here.’

Her dad hadn’t mentioned any such thing to me and I knew they didn’t have the space or the money to keep a horse, but maybe there was some kind of misunderstanding.

Later that morning, Chic was in the yard and I decided to offer Lucy a chance to ride her. ‘Lucy, I overheard you saying you like riding. Would you like to have a go on Chic?’

She blushed and mumbled something to the ground and I assumed she felt shy with me, and perhaps embarrassed that I had overheard her boasting.

‘She’s out in the yard here. Come along.’

At 15.3, Chic is quite a big horse for a smallish girl. I wouldn’t have let Lucy ride off on her but planned to lead her round the yard on Chic’s back. But as soon as I legged her up, I realised she didn’t have a clue what to do because she nearly fell straight off the other side. I looked up at her face and saw that she was ashen. She was utterly terrified. I don’t think she’d ever been on a horse before and suddenly there she was, more than five feet off the ground, having told everyone she was an experienced rider. The other children were all standing around watching so I knew I had to find a way to get her off without making her lose face.

‘Goodness, silly me,’ I exclaimed. ‘I haven’t got any stirrups short enough for you. I’m sorry but you won’t be able to ride today after all. Do you want to come down?’

I caught her as she slid off Chic’s back and skulked back into the barn again.

Later I told Michael about it. ‘I bet that’s why she hasn’t got friends at school if she’s always boasting and making up stories. Why do you think she feels the need to do that?’

‘They’re a good, loving family. I suppose she just feels insecure for some reason. Are you happy to have her come back and help again?’

‘Of course, yes. The more the merrier. It might be good for her.’

I kept half an eye out for Lucy from then on and I realised she wasn’t stupid – in fact she seemed rather bright – but she was so eager to be liked that she overdid it. If she went up to cuddle a dog, she clung on so hard that it wriggled away yelping. When she approached a hen to catch it, she was too keen and scared it off. She tried her hardest to make friends with the other children, but she did everything the wrong way. If she wasn’t boasting that her dad was loaded, or that she could read a book faster than anyone else, or that she was top of the class, then she was laughing raucously at her own, unfunny jokes. The other children soon began to give her a wide berth, and I didn’t blame them, but the more they tried to avoid her, the harder Lucy tried to make them like her.

I had a groom at the time called Sandy who helped us to train the horses. She was about twenty and Lucy was desperate to get on with her. She was cloying in her affections but still she used completely the wrong tactics. Instead of listening to Sandy’s conversation, Lucy felt she had to impress her with her knowledge of pop music, or computers, or things that were all far too old for her. Whatever Sandy said, she had to go one better. If Sandy had a new CD, Lucy boasted that she had seen the band live in concert. If Sandy mentioned a TV programme she liked, Lucy claimed to have it on video. Sandy was kind to her, but I could tell Lucy annoyed her with her constant wheedling. I knew that inside she was a frightened little girl, but I had no idea how to teach that girl better social skills. Where do you start?

Despite her lack of friends at Greatwood, Lucy was obviously happy with us. One Saturday, her father got out of the car and came over to have a word.

‘Lucy’s mother and I are so grateful for everything you’re doing for her,’ he said. ‘The school holidays are just starting and we wondered if she could spend more time here. Only if she’s useful, of course.’

In fact, she was a good worker, picking things up the first time she was told, and thinking for herself if need be. ‘I’d be delighted,’ I said.

‘I think she might be interested in working with horses when she leaves school, and we want to encourage her in her ambitions.’

‘She should stay here for a couple of weeks and get a taste of the early starts before she makes up her mind about working with horses,’ I quipped, and before I knew it, it had been agreed that Lucy would move in with us for two weeks over the summer. She’d got under my skin and I wanted to help her out if I could.

For two weeks Lucy slept in our spare room, ate her meals with us, and I didn’t for one moment regret the decision. She used to get up with me at 5am to boil the huge vats of barley on our Aga for horse feed. She’d help feed the other animals as well, then wash out the feed buckets, muck out the barns, and keep everything neat and tidy around the yard. She became adept at slipping a head collar on the horses and talking quietly to them when they needed to stand still, for example if the farrier was there to trim their hooves. All in all, she was a great asset to me – but still the other children didn’t warm to her.

While Lucy was there, we had a visit one day from a racehorse owner driving a Mercedes, who’d come to check us out and decide if we were the best home for one of his retired horses. I think the stables were a lot more dilapidated than he was used to, but when he saw the condition of our animals, he agreed that his horse, Freddy, could come to us. He duly arrived the next day in a smart trailer. Freddy was a smallish bay with a white blaze down his nose and he was in peak condition, having only come out of training a few weeks before. He danced about as he was unloaded, putting flight to the hens and some geese.

Freddy had had an ignominious end to his ten-year racing career, going from being the winner of Group 1 races at the age of two to trailing at the back of the field more recently. It would take a degree of expertise to retrain him for another career, but I thought we had a good chance of managing it. I stood him in a stable for a day or so to get used to us, then Lucy was with me when I led him up to the field at the end of the lane where we kept our other geldings. Freddy was as naughty as a two-year-old colt, rearing up on his hind legs as I led him, and I thought, ‘Uh-oh, we’re going to have our work cut out.’ He was obviously a highly strung creature.

As soon as I released him into the field, he galloped straight up to the other horses and tried to push his way into the middle of the herd. He obviously didn’t know that there was a pecking order in a herd and new members have to approach slowly and show respect. One horse nosed him roughly out of the way, then another did the same.

‘What are they doing?’ Lucy cried, and I realised she had tears in her eyes. ‘They’re going to hurt him.’

‘No, they won’t,’ I said, watching carefully just in case I was wrong. Freddy approached the group again, but they wouldn’t let him near, rejecting his advances until eventually, head down, he wandered off to graze on his own in a corner.

‘Why won’t they be friends with him?’ Lucy asked, her voice cracking.

Suddenly I realised this was touching a raw nerve for her and I chose my words carefully. ‘Freddy’s been used to being on his own a lot, or with his trainer and jockey, and he’s forgotten how to get on with other horses. He has to earn his place in the herd and wait for them to invite him in instead of charging full pelt into the middle and demanding attention. But don’t worry. It will work itself out eventually.’

‘He must be really upset about it.’

‘Yes, he probably is. But it will be all right in the end.’ At least I hoped it would.

We had to supplement Freddy’s diet while he adjusted to grazing, having previously been fed on concentrates. It became Lucy’s job to go up to the field twice a day and feed him from a bucket, trying to keep it hidden from the rest of the herd so they didn’t think he was getting special treatment, which would have made things much harder. As Lucy fed him, she would stroke his nose and whisper to him, and it was obvious that this lonely girl felt a great affinity for the lonely horse.