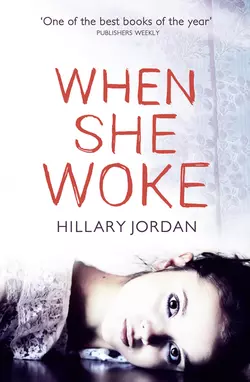

When She Woke

Hillary Jordan

Hannah Payne is a RED.Her crime: MURDER.And her victim, says the state of Texas, was her unborn child.Lying on a table in a bare room, covered by only a paper gown, Hannah awakens to a nightmare. Cameras broadcast her every move to millions at home, for whom observing new Chromes - criminals whose skin has been genetically altered to match the class of their crime - is a sinister form of entertainment.Hannah refuses to reveal the identity of her father. But cast back into a world that has marked her for life, how far will she go to protect the man she loves?An enthralling and chilling novel from the author of MUDBOUND, for fans of THE HANDMAID’S TALE and THE SCARLET LETTER.

WHEN

SHE

WOKE

Hillary Jordan

This book is for my father

“Truly, friend, and methinks it must gladden your heart, after your troubles and sojourn in the wilderness,” said the townsman, “to find yourself, at length, in a land where iniquity is searched out, and punished in the sight of rulers and people.”

—NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE, The Scarlet Letter

Table of Contents

Title Page (#ud21ae1ce-6235-5089-bfc1-87f150fc07b9)

Dedication (#ue79a6610-55ab-58c3-9067-3ce22f9c0de6)

Epigraph (#ue68dc386-4db0-5459-87bd-a2ae4cb12f35)

One: The Scaffold (#ub8d0d07a-8f82-509d-b98f-caef9dcd0a81)

When she woke, she was red. Not flushed, not (#uf56868d9-9be1-5611-9394-f38ff02a5de2)

She tried to go back to sleep, but the white light burned (#u2dfee8e5-484e-5f08-8271-27ba191977f1)

The shower became Hannah’s one pleasure and a crucial (#ucf46e140-8bdf-503b-b6d3-bf46247d2d10)

She made it to the ninth day before she asked. She hated (#u90df1d37-7481-5d5a-a0c0-a29816d780b2)

On the fourteenth day, Hannah was sitting against (#u116163e7-6f2a-5871-b435-dc8e2221db11)

How many days had She been here? Twenty-two? (#u8242bf42-8ccc-5b1d-9d1c-ac5993ee5a69)

When the lights came on, Hannah’s lids opened with (#uf17967fa-7cbd-52a3-9602-7f36636edc4b)

I am a red now. (#u2cd56576-8148-5ff4-a2f4-069ded2f23a7)

Two: Penitence (#ufbce1df2-e4c7-5715-9f20-64be1a190006)

Sunlight bouncing off concrete, glinting on razor wire (#u6687e837-615d-5af4-afbe-44947a1c36a4)

Mary magdalene herself greeted Hannah. Three (#udab14726-5036-51cd-b07f-6553c98547c7)

Exhaustion trumped the strangeness of her surroundings (#litres_trial_promo)

Hannah was restless and unable to concentrate during (#litres_trial_promo)

Hannah spent the Weekend brooding about her talk (#litres_trial_promo)

Three: The Magic Circle (#litres_trial_promo)

Hannah’s Ebullience Dwindled and eventually disappeared (#litres_trial_promo)

She walked aimlessly for close to an hour, heedless of (#litres_trial_promo)

Hannah slept until well past noon, waking to (#litres_trial_promo)

They asked her to tell them about herself, and Hannah (#litres_trial_promo)

Four: The Wilderness (#litres_trial_promo)

Hannah did little but sleep in the days that followed. (#litres_trial_promo)

A short eternity Later, the trunk opened to reveal a (#litres_trial_promo)

The briny tang of the sea was the first thing her senses (#litres_trial_promo)

Five: Transfiguration (#litres_trial_promo)

At first, when the blackness began to recede, she was (#litres_trial_promo)

She waited twenty agonizing minutes for (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Hillary Jordan (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

ONE (#ulink_9f72af19-416c-5fcd-b0f8-143edb7fba3a)

WHEN SHE WOKE, SHE WAS RED. Not flushed, not sunburned, but the solid, declarative red of a stop sign.

She saw her hands first. She held them in front of her eyes, squinting up at them. For a few seconds, shadowed by her eyelashes and backlit by the hard white light emanating from the ceiling, they appeared black. Then her eyes adjusted, and the illusion faded. She examined the backs, the palms. They floated above her, as starkly alien as starfish. She’d known what to expect—she’d seen Reds many times before, of course, on the street and on the vid—but still, she wasn’t prepared for the sight of her own changed flesh. For the twenty-six years she’d been alive, her hands had been a honey-toned pink, deepening to golden brown in the summertime. Now, they were the color of newly shed blood.

She felt panic rising, felt her throat constrict and her limbs begin to quiver. She shut her eyes and forced herself to lie still, slowing her breathing and focusing on the steady rise and fall of her belly. A short, sleeveless shift was all that covered her, but she wasn’t cold. The temperature in the room was precisely calibrated to keep her comfortable. Punishment was meted out in other ways: in increments of solitude, monotony and, harshest of all, self-reflection, both figurative and literal. She hadn’t yet seen the mirrors, but she could feel them shimmering at the edges of her awareness, waiting to show her what she’d become. She could sense the cameras behind the mirrors too, recording her every eyeblink and muscle twitch, and the watchers behind the cameras, the guards, doctors and technicians employed by the state and the millions watching at home, feet propped up on the coffee table, a beer or a soda in one hand, eyes fixed on the vidscreen. She told herself she would give them nothing: no proofs or exceptions for their case studies, no reactions to arouse their scorn or pity. She would sit up, open her eyes, see what was there to be seen and then wait calmly for them to release her. Thirty days was not such a long time.

She took a deep breath and sat up. Mirrors lined all four walls. They reflected back a white floor and ceiling, white sleeping platform and pallet, transparent shower unit, white sink and toilet. And in the midst of all that pristine white, a lurid red blotch that was herself, Hannah Payne. She saw a red face—hers. Red arms and legs—hers. Even the shift she wore was red, though of a less intense shade than her skin.

She wanted to curl into a ball and hide, wanted to scream and beat her fists against the glass until it shattered. But before she could act on any of these impulses, her stomach cramped and she felt a swell of nausea. She rushed to the toilet. She threw up until there was nothing left but bile and leaned weakly on the seat with her arm cushioning her sweaty face. After a few seconds the toilet flushed itself.

Time passed. A tone sounded three times, and a panel on the opposite wall opened, revealing a recess containing a tray of food. Hannah didn’t move from her position on the floor; she was too ill to eat. The panel closed, and the tone sounded again, twice this time. There was a brief delay, then the room went dark. It was the most welcome darkness she had ever known. She crawled to the platform and lay down on the pallet. Eventually, she slept.

She dreamed she was at Mustang Island with Becca and their parents. Becca was nine, Hannah seven. They were building a sand castle. Becca shaped the castle while Hannah dug the moat. Her fingers furrowed the sand, moving round and round the rising structure in the center. The deeper she dug, the wetter and denser the sand and the harder it was for her fingers to penetrate it. “That’s deep enough,” Becca said, but Hannah ignored her sister and kept digging. There was something down there, something she urgently needed to find. Her motions grew frantic. The sand was very wet now and very dark, and her fingers were raw. The moat started to fill with water from below, welling up over her hands to her wrists. She smelled something fetid and realized it wasn’t water but blood, dark and viscous with age. She tried to jerk her hands out of the moat, but they were caught on something—no, something was holding them, pulling them down. Her arms disappeared up to the elbows. She screamed for her parents, but the beach was empty apart from herself and Becca. Her face hit the sand castle, collapsing it. “Help me,” she begged her sister, but Becca didn’t move. She watched impassively as Hannah was pulled under. “Kiss the baby for me,” Becca said. “Tell it—” Hannah couldn’t hear the rest. Her ears were full of blood.

She started awake, heart tripping. The room was still dark, and her body was cold and wet. It’s just sweat, she told herself. Not blood, sweat. As it dried she began to shiver, and she felt the air around her grow warmer to compensate. She was about to nod off again when the tone sounded twice. The lights came on, blindingly bright. Her second day as a Red had begun.

SHE TRIED TO GO BACK TO sleep, but the white light burned through her closed lids, through her eyeballs and into her brain. Even with an arm flung over her eyes, she could still see it, like a harsh alien sun blazing inside her skull. This was by design, she knew. The lights inhibited sleep in all but a small percentage of inmates. Of these, something like ninety percent committed suicide within a month of their release. The message of the numbers was unambiguous: if you were depressed enough to sleep despite the lights, you were as good as dead. Hannah couldn’t sleep. She didn’t know whether to be relieved or disappointed.

She shifted onto her side. She couldn’t feel the microcomputers embedded in the pallet, but she knew they were there, monitoring her temperature, pulse rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, white blood cell count, serotonin levels. Private information—but there was no privacy in a Chrome ward.

She needed to use the toilet but held it for as long as possible, mindful of the cameras. While “acts of personal hygiene” were censored from public broadcast, she knew the guards and editors still saw them. Finally, when she could wait no longer, she got up and peed. The urine came out yellow. There was some comfort in that.

At the sink she found a cup and toothbrush. She opened her mouth to clean her teeth and was startled by the sight of her tongue. It was a livid reddish purple, the color of a raspberry popsicle. Only her eyes were unchanged, still a deep black, surrounded by white. The virus no longer mutated the pigment of the eyes as it had in the early days of melachroming. There’d been too many cases of blindness, and that, the courts had decided, constituted cruel and unusual punishment. Hannah had seen vids of those early Chromes, with their flat neon gazes and disturbingly blank faces. At least she still had her eyes to remind her of who she was: Hannah Elizabeth Payne. Daughter of John and Samantha. Sister of Rebecca. Killer of a child, unnamed. Hannah wondered whether that child would have inherited its father’s melancholy brown eyes and sensitive mouth, his high wide brow and translucent skin.

Her own skin felt clammy, and her body smelled sour. She went to the shower unit. A sign on the door read: WATER NONPOTABLE. DO NOT DRINK. Just beneath it was a hook for her shift. She started to take it off but then remembered the watchers and stepped inside still wearing it. She closed the door, and the water came on, blessedly hot. There was a dispenser of soap and she used it, scrubbing her skin hard with her hands. She waited until the walls of the shower steamed up and then lifted up her shift and quickly soaped and rinsed herself underneath. As always, the feel of hair under her arms surprised her, though she should have been used to it by now. She hadn’t been allowed a lazor since her arrest. At first, when the hair there and on her legs had begun to grow out, going from stubbly to silky, it had horrified her. Now, the thought of such feminine vanity made her laugh, an ugly sound, loud in the enclosed space of the stall. She was a Red. Her femininity was irrelevant.

She remembered the first time she’d seen a female Chrome, when she was in kindergarten. Then as now, they were comparatively rare, and the vast majority were Yellows serving short sentences for misdemeanors. The woman Hannah had seen was a Blue—an even more uncommon sight, though she was too young then to know it. Child molesters tended not to survive long once they were released. Some committed suicide, but most simply disappeared. Their bodies turned up in dumpsters and rivers, stabbed or shot or strangled. That day, Hannah and her father had been crossing the street, and the woman, swathed in a long, hooded coat and gloves despite the sticky autumn heat, had been crossing in the opposite direction. As she approached, Hannah’s father jerked Hannah toward him, and the sudden motion caused the woman to lift her lowered head. Her face was a startling cobalt blue, but it was her eyes that riveted Hannah. They were like shards of basalt, jagged with rage. Hannah shrank away from her, and the woman smiled, baring white teeth planted in ghastly purple gums.

Hannah hadn’t quite finished rinsing herself when the water brake activated. The dryjets came on, and warm air whooshed over her. When they cut off, she stepped out of the shower, feeling a little better for being clean.

The tone sounded three times and the food panel opened. Hannah ignored it. But it seemed she wouldn’t be allowed to skip another meal, because after a short delay a different tone sounded, this one a needle-sharp, intolerable shriek. She walked quickly to the opening in the wall and removed the tray. The sound stopped.

There were two nutribars, one a speckled brown, the other bright green, as well as a cup of water and a large beige pill. It looked like a vitamin, but she couldn’t be sure. She ate the bars, leaving the pill, and returned the tray to the opening. But as she turned away, the shrieking started again. She picked up the pill and swallowed it. The sound stopped and the panel slid shut.

Now what? Hannah thought. She looked despairingly around the featureless cell, wishing for something, anything to distract her from the sight of herself. In the infirmary, just before they’d injected her with the virus, the warden had offered her a Bible, but his pompous, self-righteous manner and disdainful tone had kept her from taking it. That, and her own pride, which had prompted her to say, “I don’t want anything from you.”

He smirked. “You won’t be so high and mighty after a week or two alone in that cell. You’ll change your mind, just like they all do.”

“You’re wrong,” she said, thinking, I’m not like the others.

“When you do,” the warden went on, as if Hannah hadn’t spoken, “just ask, and I’ll see to it you get one.”

“I told you, I won’t be asking.”

He eyed her speculatively. “I give you six days. Seven, tops. Don’t forget to say please.”

Now, Hannah kicked herself for not having accepted that Bible. Not because she would find any comfort in its pages—God had clearly abandoned her, and she couldn’t blame Him—but because it would have given her something to contemplate besides the red ruin she’d made of her life. She leaned back against the wall and slid down it until her buttocks touched the floor. She hugged her knees and rested her head on top of them, but then saw the pitiful, little-match-girl picture she made in the mirror and straightened up, crossing her legs and folding her hands in her lap. There was no way to tell when she was on. Although the feed from each cell was continuous and the broadcasts were live, they didn’t show every inmate all the time, but rather, shuffled among them at the discretion of the editors and producers. Hannah knew she was just one of thousands they had to choose from in the central time zone alone, but from the few times she’d watched the show she also knew that women, especially the attractive ones, tended to get more airtime than men, and Reds and other felons more than Yellows. And if you were one of the really entertaining ones—if you spoke in tongues or had conversations with imaginary people, if you screamed for mercy or had fits or scraped your skin raw trying to get the color off (which was allowed only to a point, and then the punishment tone would sound)—you could be bumped up to the national show. She vowed to present as calm and uninteresting a picture as possible, if only for her family’s sake. They could be watching her at this moment. He could be watching.

He hadn’t come to the trial, but he’d appeared via vidlink at her sentencing hearing. A holo of his famous face had floated in front of her, larger than life, urging her to cooperate with the prosecutors. “Hannah, as your former pastor, I implore you to comply with the law and speak the name of the man who performed the abortion and any others who played a part.”

Hannah couldn’t bring herself to look at him. Instead, she watched the attorneys and court officials, spectators and jurors as they listened to him, leaning forward in their seats to catch his every word. She watched her father, who sat hunched in his Sunday suit and hadn’t met her eyes since the bailiff had led her into the courtroom. Of course, her mother and sister weren’t with him.

“Don’t be swayed by mistaken loyalty or pity for your accomplices,” the reverend went on. “What can your silence do for them, except encourage them to commit further crimes against the unborn?” His voice, low and rich and roughened by emotion, rolled through the room, commanding the absolute attention of everyone present. “By the grace of God,” he said, on a rising note, “you’ve been granted an open shame, so that you may one day have an open triumph over the wickedness within you. Would you deny your fellow sinners the same bitter but cleansing cup you now drink from? Would you deny it to the father of this child, who lacked the courage to come forward? No, Hannah, better to name them now and take from them the intolerable burden of hiding their guilt for the rest of their lives!”

The judge, jury, and spectators turned to Hannah expectantly. It seemed impossible that she could resist the power of that impassioned appeal. It came, after all, from none other than the Reverend Aidan Dale, former pastor of the twenty-thousand-member Plano Church of the Ignited Word, founder of the Way, Truth & Life Worldwide Ministry and now, at the unheard-of age of thirty-seven, newly appointed secretary of faith under President Morales. How could Hannah not speak the names? How could anyone?

“No,” she said. “I won’t.”

The spectators let out a collective sigh. Reverend Dale placed his hand on his chest and lowered his head, as though in silent prayer.

“Miss Payne,” said the judge, “has your counsel made you aware that by refusing to testify as to the identities of the abortionist and the child’s father, you’re adding six years to your sentence?”

“Yes,” she replied.

“Will the prisoner please rise.”

Hannah felt her attorney’s hand on her elbow, helping her to stand. Her legs wobbled and her mouth was dry with dread, but she kept her face expressionless.

“Hannah Elizabeth Payne,” began the judge.

“Before you sentence her,” interrupted Reverend Dale, “may I address the court once more?”

“Go ahead, Reverend.”

“I was this woman’s pastor. Her soul was in my charge.” She looked at him then, meeting his gaze. The pain in his eyes tore at her heart. “That she’s sitting before this court today isn’t just her fault, but mine as well, for failing to guide her toward righteousness. I’ve known Hannah Payne for two years. I’ve seen her devotion to her family, her kindness to those less fortunate, her true faith in God. Though her crime is grave, I believe that through His grace she can be redeemed, and I’ll do everything in my power to help her, if you’ll show her leniency.”

Among the jury, heads nodded and eyes misted. Even the judge’s stern countenance softened a bit. Hannah began to have hope. But then he shook his head sharply, as if he were dispelling an enchantment, and said, “I’m sorry, Reverend. The law is absolute in these cases.”

The judge turned back to her. “Hannah Elizabeth Payne, having been found guilty of the crime of murder in the second degree, I hereby sentence you to undergo melachroming by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, to spend thirty days in the Chrome ward of the Crawford State Prison and to remain a Red for a period of sixteen years.”

When he banged the gavel she swayed on her feet but didn’t fall. Nor did she look at Aidan Dale as the guards led her away.

THE SHOWER BECAME HANNAH’S one pleasure and a crucial intermission during the long, bleak hours between lunch and dinner. She’d learned that lesson on day two, when she’d showered first thing in the morning. The afternoon had crawled by while the silence beat against her eardrums and her thoughts careened between the past and the present. When, desperate for distraction, she tried to take a second shower, nothing came out of the nozzle. She cursed her keepers then, a savage “Damn you!” that would have shocked her younger, more innocent self, the Hannah of just two years ago whose life had revolved around the twin nuclei of her family and the church; who’d lived with her parents, worked as a seamstress for a local bridal salon, gone to services on Sunday mornings and Wednesday nights and Bible study classes twice a week, volunteered at the thrift shop and campaigned for Trinity Party candidates. That Hannah had been a good girl and a good Christian, obedient to her parents’ wishes—in almost everything.

Her one secret vice was her dresses: dresses with keyhole necklines and mother-of-pearl buttons, sheer overlays and pencil skirts, made from sumptuous velvets and jewel-toned silks and voiles shot through with gold thread. She designed them herself and sewed them late at night, hiding them under the virginal white mounds of silk, lace and tulle that filled her workroom over the garage. When she finished one, she would double-check to make sure her parents and Becca were asleep and then creep back up to the workroom, lock the door and try it on, doing slow, dreamy pirouettes in front of the mirror. Though she knew it was vain and sinful, she couldn’t help taking pleasure in the feel of the fabric and the way the colors warmed her skin. What a contrast to the dull clothing she had to wear outside that room, the demure dresses that her faith dictated, high-necked and calf-length, pastel or tastefully flowered. She wore these things dutifully, understanding their necessity in a world full of temptation, but she hated putting them on in the morning, and no amount of praying on the subject could make her feel differently.

Hannah was well aware of her own rebellious nature. Her parents had scolded her for it all her life while urging her to emulate her sister. Becca was a sunny, obedient child who swam through adolescence and into womanhood with an ease Hannah envied. Becca never struggled to follow God’s plan or had any doubts about what it was, never yearned for something indefinably more. Hannah tried to be like her sister, but the more she suppressed her true nature, the stronger it burst forth when her resolve weakened, as it inevitably did. During her teens she was always getting into trouble over one thing or another: trying on lip gloss, doing forbidden searches on her port, reading books her parents considered corrupting. Most often though, it was for voicing the questions that cropped up so insistently in her mind: “Why is it immodest for girls not to wear shirts but not for boys?” “Why does God let innocent people suffer?” “If Jesus turned water into wine, why is it wrong for people to drink it?” These questions exasperated her parents, especially her mother, who would make her sit in silence for hours and reflect on her presumption. Good girls, Hannah came to understand, did not ask why. They did not even wonder it in their most private thoughts.

The dresses had saved her, at least temporarily. She’d always had a gift for needlework, and the walls of the Payne house were covered with her samplers, progressing from the simple cross-stitch of her early efforts—JESUS LOVES ME, HONOR THY FATHER AND MOTHER, GIVE SATAN AN INCH AND HE’LL BE A RULER—to elaborately embroidered verses illustrated with lambs, doves and crosses. She’d sewn clothes for her and Becca’s dolls, embroidered flowers on her mother’s aprons and JWPs on her father’s handkerchiefs, using them as peace offerings when she fell from grace. But none of it had been enough to fill her or to silence the questions within her.

And then, when she was eighteen, she happened on the bolt of violet silk buried in the sale bin at the fabric store. From the moment she saw it she wanted to possess it. It shimmered with a deep, mysterious beauty that seemed to call out to her. She ran her fingers across it caressingly and, when her mother’s back was turned, leaned down and rubbed its softness against her cheek. Becca hissed, warning her that their mother was coming, and Hannah dropped the fabric, but the voluptuous feel of it lingered on her skin. That night, a violet shape began to form in her mind, indistinct at first, growing sharper the more she imagined it: an evening gown with long sleeves and a high neckline, but with a low, scooped back—a dress with a secret side. From there it was just a short journey to imagining herself wearing it, not on a Paris runway or at a ball in the arms of a handsome prince, but alone, in a plain room with gleaming wood floors and one standing mirror where she could admire it without guilt, seeking to please no one but herself.

She waited a full week before riding her bike back to the shop, telling herself that if the fabric was gone, it was God’s will, and she would obey. But not only was the bolt still there, it had been marked down another thirty percent. So be it, she thought, without a trace of irony. She was still eight years away from irony.

For six of them, the secret dresses had been enough. She’d made one or at most two a year, spending months on the designs before choosing the fabric and beginning the work. Creating them satisfied something within her that nothing else ever had, assuaging her restlessness and making it easier for her to fill her expected role. Her parents praised her for her newfound obedience and God for having shown her the way to it. Hannah, for her part, felt just as grateful to Him. God had shown her the way. With that bolt of violet silk, He’d given her a channel for her passions, one that harmed no one and would sustain her for years to come.

And so it had. Until she’d met Aidan Dale.

Now, sitting against the wall of her cell, waiting for the dinner tone to sound, Hannah thought back to their first meeting on that terrible Fourth of July two years ago. Her father managed a sporting goods store, and he’d had to work that day. He’d been coming home on the train when the suicide bomber blew up himself and seventeen other people. Her father had been at the far end of the car and was badly injured. He had a fractured skull, a perforated eardrum and multiple lacerations from the screws the terrorist had packed around the bomb, but the most worrisome injuries were to his eyes. The doctors said there was a fifty-fifty chance he wouldn’t regain his sight.

The day after his surgery, Hannah had returned from the hospital cafeteria with a tray of drinks and sandwiches to find Aidan Dale kneeling with her mother and Becca beside her father’s bed, beseeching God to heal his wounds. Hannah had heard him speak countless times before, but sitting in the sixtieth row listening to him on the loudspeakers was poor preparation for the effect of hearing him in person. His voice was so sonorous and compelling, imbued with such faith and passion that it seemed an instrument created for the sole purpose of reaching Him. It traveled through her like hot liquid, warming her and calming her fear. Surely God would not, could not ignore the pleas of that voice.

She set the food down and went to the bed. She’d never been this close to Reverend Dale before, and he looked younger than she’d expected. A curling lock of light brown hair fell onto his brow and nearly into his eye, and she found her fingers itching to smooth it back. Disconcerted—where had that come from?—she knelt across from him. When he looked up and saw her, his prayer faltered briefly, and then he closed his eyes and continued. Hannah bent her head, letting her hair fall forward to hide her confusion.

After he finished, he stood and came around to her side of the bed. For an anxious moment, all she could do was stare at his knees.

“You must be Hannah,” he said.

She got to her feet, made herself look at him. Nodded. The compassion in his eyes made her own blur with tears. She mumbled a “Thank you” and looked down at her father, swathed in bandages and riddled by needles and tubes. The shape his body made beneath the sheet seemed too small to be his. All that was visible of him were the top of his head and one forearm, and as she reached down to stroke the patch of exposed skin, it occurred to her that she could be touching a perfect stranger and never even know it. A tear rolled down her cheek and fell onto his arm, and then she felt Reverend Dale’s hand come down on her shoulder, a warm and reassuring weight. She had to fight the urge to lean into it, into him.

“I know you’re frightened for him, Hannah,” he said, and she thought how lovely her name sounded, shaped by his mouth: a poem of two syllables. “But he’s not alone. His Father is within him, and Jesus is by his side.”

As you are by mine. She was keenly aware of the mere inches that separated them. She could smell his scent, cedar and apples and a faint, sharp trace of raw onion, and feel the heat emanating from his body against her back. She closed her eyes, seized by an unknown sensation, a swoop of want and need and belonging. Was this what people meant, when they spoke of desire?

Her father moaned in his sleep, wrenching her back to reality. How could she be thinking such thoughts while he lay wounded and suffering before her? How could she be thinking them at all?

For Aidan Dale was a married man. He and his wife, Alyssa, had wed in their early twenties, and by all accounts and appearances their union was a happy one. His unfailing tenderness toward her and the rapt, adoring expression she wore when he preached were the cause of much sighing among the female members of the congregation—including Becca, who’d vowed at eighteen never to marry unless she were as deeply in love as the Dales. And yet, they were childless. No one knew why, but it was a subject of constant speculation and prayer at Ignited Word. All agreed there could be no two people better suited to parenthood, or more worthy of its joys, than Aidan and Alyssa Dale. That God had chosen to deny them this greatest of blessings was a mystery and a vivid illustration of His inexplicable will. If the Dales were saddened by it—and how could they not be? and why had they never adopted?—they bore it well, channeling their energies into the church. Still, it didn’t go unnoticed that children, particularly those in need, were the special focus of Reverend Dale’s ministry. He’d founded shelters and schools in every major city in Texas and funded countless others across the country. He was a regular visitor to the refugee camps in Africa, Indonesia and South America and had worked with the governments of many war-ravaged countries to enable adoption of orphans by American families.

The WTL Ministry brought in millions, but the Dales didn’t live in a gated mansion or have an army of servants and bodyguards. Most of what came into the ministry went out again to those in need. Aidan Dale was known and admired the world over as a true man of God, and Hannah had always felt proud to be a member of his congregation. But what she was feeling at this moment—what his nearness and the simple touch of his hand were kindling in her—went far beyond pride and admiration. Sinfully far. Forgive me, Lord, she prayed.

Reverend Dale’s hand lifted, leaving a cool, empty space on her shoulder, and he went back to stand before her mother. “Is there anything you need, Samantha? Any help at home?”

“No, thank you, Reverend. Between family and friends from church, we have more helping hands and casseroles than we know what to do with.”

Gently, he said, “And you’re all right for money?”

Hannah saw her mother’s face color a little. “Yes, Reverend. We’ll be fine.”

“Please, call me Aidan.” When she hesitated, he said, “I insist.” Finally she gave a reluctant nod. Reverend Dale smiled, satisfied that he’d prevailed, and Hannah smiled too, knowing that her mother would sooner take up pot smoking or become a lingerie model than address a pastor, and especially this pastor, by his first name.

Aidan. Hannah tasted it in her mind and thought, But I could.

He gave them his private contact information and made them promise to call at any hour if they needed anything at all. When he extended his hand to Hannah’s mother, she took it in both of hers, then bent and lay her forehead against it for a few seconds. “God bless you for coming, Reverend. It will mean the world to John to know you were here.”

“Well, I—I’m just glad I was in town,” he said, reclaiming his hand awkwardly. “I was supposed to be in Mexico this week, but my trip got postponed at the last minute.”

“The Lord must love our father a great deal, to have kept you here,” Becca said. Like their mother’s—and, Hannah supposed, her own—her face was soft with reverence.

Aidan ducked his head like a teenaged boy being praised for how much he’d grown, and Hannah realized, with some astonishment, that he was not only genuinely embarrassed by their adulation but that he also felt himself to be unworthy of it. The swooping sensation came again, stronger this time. How many men in his position would be so humble?

“Yes,” Hannah agreed. “He must.”

Aidan’s port chimed, and he glanced at it with evident relief. “I’d better get back,” he said. “Alyssa and I will pray for John, and for all of you.”

Alyssa and I. The words clanged in Hannah’s head, reminding her that Aidan Dale was another woman’s husband, a woman who had a name, Alyssa, and who worried about him the way Hannah’s own mother worried about her father. By wanting him, Hannah wronged Aidan’s wife as surely as if she lay with him. Shaken and ashamed, she shook his hand, thanked him and said goodbye. That night when she got home, she prayed for a long time, asking God’s forgiveness for breaking His commandment and imploring Him to lead her away from temptation.

Instead, He sent Aidan Dale back to the hospital the following day, and the one after that and nearly every day for the next week. Hannah’s mother and sister were in raptures over his continued attention to their family. Such an important man, with such a large flock to tend to, and yet here he was, praying with them daily! Hannah’s own feelings were a tangle of elation and despair. She knew that God was testing her and that she was failing the test, but how could she not, when it was so cruelly rigged? Aidan (whom she was careful to call Reverend Dale, despite his protestations) brought them light and hope. He made Becca smile and took some of the fear from their mother’s eyes. And once their father was off the painkillers and clearheaded enough to remember what had happened to him, Aidan spoke quietly with him, once for almost two hours, lending him the strength to beat back the terror, rage and helplessness Hannah saw in his face when he thought she wasn’t looking.

The morning the bandages were to come off, Aidan arrived early and waited with them for the surgeon. He said a prayer, but Hannah was too anxious to follow it. She stood by the bed and stroked her father’s hand, knowing how desperately afraid he must feel at this moment. He’d always prided himself on being the kind of man who could be counted on, a man to whom others looked for advice and support. Dependence would wither his spirit, and the thought of that, of her father being diminished or broken, was almost as unbearable as the thought of losing him.

The surgeon arrived at last, and they all clustered around the bed while he cut off the bandages. The three women stood on one side, the doctor on the other, Aidan at the foot. Hannah’s father opened his eyes. They seemed unfocused at first, and then they settled on her mother.

“You look beautiful,” he said finally, “but you’ve gotten awfully skinny.” They all erupted then, laughing through the tears as they kissed and hugged him.

“Thank God,” Aidan said. The huskiness in his voice made Hannah glance up at him. His expression was grave, and he was looking not at her father but at her.

Then his eyes dropped, and he smiled and said, “Congratulations, John,” leaving Hannah to wonder whether she’d imagined the thing she’d seen in them, the swoop of want and need and belonging.

SHE MADE IT TO THE NINTH day before she asked. She hated to do it, but it was either that or become one of the screamers.

“I’d like a Bible,” she said, addressing the wall with the food compartment. Then she waited. Lunch came: two nutribars, one pill. No Bible. “Hey,” she said to the wall, not quite shouting. “Is anybody listening? I want a Bible. The warden said I could have one if I asked.” Reluctantly, she added, “Please.”

It arrived with dinner. It was the original King James Version, not the New International Version that Hannah had grown up with. The leather cover was cracked, the pages dog-eared. The New Testament was more worn than the Old, except for Psalms, the pages of which were so tattered and smudged she could barely make out some of the passages. But the verse she sought was all too legible. “But I am a worm, and no man,” she whispered. “A reproach of men, and despised of the people. All they that see me laugh me to scorn.”

Her mother despised her now, she’d made that plain the one time she visited Hannah in jail, shortly before the trial began. By then Hannah had been incarcerated for three months. Her father had come every Saturday, and Becca whenever she could get away, but Hannah hadn’t laid eyes on her mother since the day of her arrest. So when she walked into the visiting room and saw the familiar figure sitting on the other side of the grimy barrier, she started to cry, wrenching sobs of anguish and relief.

“Stop your sniveling,” her mother said. “Stop it this instant or I’m walking right back out that door, do you hear?”

The words fell on Hannah like stones. She pushed back her tears and drew herself up, returning her mother’s wintry gaze—the eyes, the face so like her own—without flinching. It struck her that if an artist were to sketch their two silhouettes just then, they’d be mirror images of each other.

Even at fifty and even in a plain beige dress, Samantha Payne was a striking woman. She was tall and full-figured, with a dignified carriage that had led some to call her proud. Her large eyes were black, accented by bold slashes of brow, and her dark hair was no less luxuriant for being threaded with white. Hannah had inherited every bit of this bounty and then some. Over the years, she’d endured many a lecture from her mother on the folly of earthly vanity. She and Becca had sat through them together, but it had been apparent to them both that Hannah was the primary object of these admonishments.

“I’m not here to comfort you,” Hannah’s mother said now. “I have no more sympathy for you than you had for that innocent baby.”

Hannah could hardly breathe against the weight of her mother’s words. “Then why did you come?”

“I want to know his name. The name of the man who dishonored you and then sent you off to abort your child.”

Hannah shook her head involuntarily, remembering the feel of Aidan’s lips on her skin, kissing the inside of her elbow, the tender instep of her foot; of his hands lifting her hair off her neck, raising her arms, pushing her legs open so his mouth could claim every hidden part of her. It hadn’t felt like dishonor. It had felt like worship.

“He didn’t send me,” she said. “It was my decision.”

“But he gave you the money.”

“No. I paid for it myself.”

Her mother frowned. “Where would you get that kind of money?”

“I’ve been saving it for a while. I … I thought I might use it to start my own dress shop someday.”

“Dress shop! A store for Jezebels and harlots is more like it. Oh yes, I found all the sinful things you made. I cut them to pieces, every last one of them.”

Another brutal, unexpected hail of stones. They hit Hannah hard, rocking her back in her chair. All her creations, destroyed. Though she’d known she could never wear them openly, the mere fact of their existence, of their prodigal beauty, had buoyed her during the long, dreary days of her imprisonment. Now, she would leave nothing that mattered of herself behind.

“Did you make them for him?” her mother demanded.

“No. For myself.”

“Why do you protect him? He doesn’t love you, that much is plain. If he did, he would have married you.”

Her mother must have seen something in her face, an unconscious flicker of pain. “He’s already married, isn’t he.”

It wasn’t a question, and Hannah made no answer to it.

Her mother held up a forefinger. “You shall not commit adultery.” A second finger. “You shall not covet your neighbor’s husband.” A third. “You shall not murder.” The little finger. “Honor your father and mother, so that you may—”

Her anger woke Hannah’s own. “Careful, Mama,” she said, “you’ll run out of fingers.” The remark shocked them both. Hannah had never spoken so derisively to her parents, or to anyone for that matter, and for a few seconds she felt better for having done so, stronger and less afraid. But then her mother’s shoulders buckled and the flesh of her face seemed to wither, shrinking inward against the bones, and Hannah understood that her sarcasm had broken something in her mother, some fragile hope she’d clung to that the daughter she once knew and loved was not wholly lost to her.

“Sweet Jesus,” her mother said, wrapping her arms around herself and rocking back and forth in her chair with her eyes closed. “Sweet Lord, help me now.”

“I’m sorry, Mama,” Hannah cried. She felt like she was breaking herself, into fragments so small they could never be found, much less pieced together again. “I’m so sorry.”

Her mother looked up, her eyes bewildered. “Why did you do this thing, Hannah? Your father and I would have stood by you and the baby. Did you not know that?”

“I knew,” Hannah said. Her mother would have stormed, and her father would have brooded. They would have rebuked and sermonized and interrogated and wept and prayed, but in the end, they would have accepted the child. Would have loved it.

“Then I don’t understand. Help me to understand, Hannah.”

“Because—” Because I would have been compelled to name Aidan as the father or go to prison for contempt until I did. Because they would have notified the state paternity board, subpoenaed him, had him tested, ordered Ignited Word to garnish his wages for child support. Destroyed his life and his ministry. Because I loved him, more even than our child. And still do.

Hannah would have done anything at that moment to erase the grief from her mother’s face, but she knew that to tell the truth, to speak the syllables of his name, would only hurt her more, by stripping her of her faith in a man she revered. And if she blamed him and decided to reveal their secret … No. Hannah had aborted their child to protect him. She would not betray him now.

She shook her head, once. “I can’t tell you. I’m sorry.” Stones of her own, falling hard and heavy into the space between them. The wall rose in seconds. She watched it happen, watched her mother’s face close against her. “Please, Mama—”

Samantha Payne stood. “I don’t know you.” She turned and walked to the door. Stopped. Looked back at Hannah. “I have one daughter, and her name is Rebecca.”

ON THE FOURTEENTH DAY, Hannah was sitting against the wall thumbing listlessly through the New Testament when she felt wetness between her legs. She looked down and saw a bright smear of blood on the white floor. Its arrival unleashed a spate of emotions: Relief, because although the abortionist had assured her that her cycles would resume eventually, she hadn’t been able to shake the idea that God would take away her fertility as punishment. Then, swiftly on the heels of that, bitterness. What difference did it make if she was fertile? No decent man would want to marry her now, and even if she found one who did, she couldn’t have a child with him; the implant they gave all Chromes would prevent it. Then, despair. By the time she finished her sentence and the implant was removed, she’d be forty-two, assuming she survived that long. Her youth would be gone, her eggs old, her chances of attracting a man to give her children diminished. And finally, embarrassment, as she remembered the presence of the cameras. She felt herself blushing and just as quickly realized that no one could tell—a small blessing.

She stood up, ignoring the blood on the floor, and went to wash herself off. When she came out of the shower, the panel was open. Inside were a box of tampons, a packet of sterile wipes and a clean tunic. Looking at them, she felt a shame so profound she wanted to die rather than endure another moment of it. When she’d been lying on the table with her legs spread and a stranger’s hand moving inside her womb, she’d thought that there could be nothing worse, nothing. Now, confronted with these everyday items that represented the absolute and irretrievable loss of her dignity, she knew she’d been wrong.

SHE ALMOST HADN’T gone through with it. She’d taken the pregnancy test at just over six weeks, after her second missed period, and then agonized for another month before screwing up the courage to act. She’d asked a girl she worked with, a salesperson at the bridal salon with whom she was friendly, though not friends. Gabrielle was a self-described wild child with a wicked sense of humor and a sailor’s vocabulary that emerged whenever their boss and customers were out of earshot. She had an endless string of boyfriends, often overlapping, and was cheerfully matter-of-fact about her own promiscuity. Her manner had shocked and intimidated Hannah at first, but over time she’d come to appreciate Gabrielle’s confidence and self-possession, how utterly comfortable she was in her own skin. Of everyone Hannah knew, Gabrielle was the only person she felt she could approach with this.

The next time she went to the shop for a fitting, Hannah asked Gabrielle if she would meet her for a coffee after work. They’d never socialized before, and the other girl appraised her with unconcealed surprise and curiosity.

“Sure,” Gabrielle said finally, “but let’s make it a drink.”

They’d met at a bar a few blocks away. Gabrielle ordered a beer, Hannah a ginger ale. Her hand shook as she picked up her glass, and she set it back down again. What if Gabrielle decided to turn her in to the police? What if she told their employer? Hannah couldn’t risk it. She was trying to think of a pretext for her invitation when Gabrielle said, “You in trouble?”

“Not me,” Hannah said. “A friend of mine.”

“What kind of trouble?”

Hannah didn’t answer. She couldn’t speak the words.

Gabrielle looked at the ginger ale, then back at Hannah. “This friend of yours knocked up?”

Hannah nodded, her heart in her mouth.

“And?” Gabrielle said. Watchful, waiting.

“She, she doesn’t want to have it.”

“Why are you telling me?”

“I thought you might … know somebody who could help her.”

“And I thought that kind of thing was against your religion.”

“My friend can’t have this baby, Gabrielle. She can’t.” Hannah’s voice broke on the word.

Gabrielle considered her for a long moment. “I might know somebody,” she said. “If she’s sure. She has to be really sure.”

“She is.” And Hannah was, at that moment, completely, agonizingly sure. She couldn’t bring this baby into this situation, this world she and Aidan lived in. She started to cry.

Gabrielle reached across the table and squeezed Hannah’s hand. “It’s gonna be okay.”

There were several somebodies, actually, each a small exercise in terror for Hannah, but eventually she spoke to a woman who gave her an address, careful instructions on what to do when she got there and the name of the man who would do it, Raphael. It was obviously a pseudonym, and Hannah was jarred by its dissonance. Why would an abortionist name himself after the archangel of healing? When she asked whether Raphael was a real doctor, the woman hung up.

The appointment was at seven in the evening in North Dallas. Hannah took the train to Royal Lane, then a bus to the apartment complex, and arrived early. She stood frozen in the parking lot, staring in dread at the door to number 122. The news vids were full of horror stories about women who’d been raped and robbed by charlatans posing as doctors; women who’d bled to death or died of infection, who’d been anesthetized and had their organs stolen. For the first time, Hannah wondered how much of that was true and how much was fiction disseminated by the state as a deterrent.

The windows of number 122 were dark, but the apartment next to it was lit from within. Hannah couldn’t see the occupants, but she could hear them through the open window, a man, a woman and several children. They were having supper. She heard the clink of their glasses, the scrape of their silverware against their plates. The children started to quarrel, their voices rising, and the woman scolded them tiredly. The bickering continued unabated until the man boomed, “That’s enough!” There was a brief silence, and then the conversation resumed. The ordinariness of this domestic scene was what made Hannah cross the lot in the end. This she knew she could never have, not with Aidan.

She entered the apartment without knocking and shut the door behind her, leaving it unlocked as she’d been instructed. “Hello?” she whispered. There was no answer. It was pitch black inside and stiflingly hot, but she’d been warned not to open a window or turn on the lights.

“Is anyone there?” No response. Maybe he wasn’t coming, she thought, half hopeful and half despairing. She waited in the airless dark for long, anxious minutes, feeling the sweat gradually soak her blouse. She was turning to leave when the door opened and a large man slipped inside, closing it behind him too quickly for Hannah to get a look at his face. The loud crack of the deadbolt sent a surge of alarm through her. She made a wild movement toward the door and felt a hand grip her arm.

“Don’t be frightened,” he said softly. “I’m Raphael. I’m not going to hurt you.”

It was an old man’s voice, weary and kind, and the sound of it reassured her. He let go of her arm, and she heard him move across the room toward the window. A sliver of light from outside appeared as he opened the curtain and peered out at the parking lot. He stood at the window for quite a while, watching. Finally he shut the curtain and said, “Come this way.”

A beam of light appeared, and she followed it through the living room, down a short hallway and into a bedroom. She hesitated on the threshold.

“Come in,” Raphael said. “It’s all right.” Hannah entered the room and heard him close the door behind her. “Lights on,” he said.

Raphael, she saw then, didn’t look like a Raphael. He was overweight and unimposing, with stooped shoulders and an air of absentminded dishevelment. She guessed him to be in his mid-sixties. His wide, fleshy face was red-cheeked and curiously flat, and his eyes were round and hooded. Tufts of frizzled gray hair poked out from either side of an otherwise bald head. He reminded Hannah of pictures she’d seen of owls.

He held out his hand, and she shook it automatically. Just as if, she thought, they were meeting after church. Wonderful sermon, wasn’t it, Hannah? Oh yes, Raphael, very inspiring.

The room was empty except for two folding chairs, a large table and an ancient-looking box fan, which sputtered to life when Raphael turned it on. Heavy black fabric covered the one window. Hannah stood uncertainly while he opened a duffel bag on the floor, removed a bed sheet from it and spread it on the table. It was patterned incongruously with colorful cartoon dinosaurs. They jogged her back to her ninth birthday, when her parents had taken her to the Creation Museum in Waco. There’d been an exhibit depicting dinosaurs in the Garden of Eden and another showing how Noah had fit them onto the ark along with the giraffes, penguins, cows and so forth. Hannah had asked why the Tyrannosaurus rexes hadn’t eaten the other animals, or Adam and Eve, or Noah and his family.

“Well,” said her mother, “before Adam and Eve were cast out of Paradise, there was no death, and humans and animals were all vegetarians.”

“But Noah lived after the fall,” Hannah pointed out.

Her mother looked at her father. “He was a smart guy,” her father said. “He only took baby dinosaurs on the ark.”

“Duh,” Becca said, giving Hannah’s arm a hard pinch. “Everybody knows that.”

Becca was Hannah’s barometer for her parents’ displeasure; the pinch meant she was on dangerous ground. Still, it didn’t add up, and she hated it when things didn’t add up. “But how come—”

“Stop asking so many questions,” her mother snapped.

Raphael interrupted Hannah’s reverie. “Sorry about the sheets. I get them from the clearance bin, and this was all they had. They’re clean, though. I washed them myself.”

He opened a medicine bag, fished out a pair of rubber gloves and put them on, then began removing medical instruments from the bag and placing them on the table. Hannah looked away from their ominous silver glint, feeling suddenly woozy.

He gestured at one of the chairs. “Why don’t you sit down.”

She’d expected to have to get undressed right away, but when he’d finished his preparations, he drew up the other chair and started asking her questions: How old was she? Had she ever had children? Other abortions? When was her last period? When had her morning sickness started? Had she ever had any serious medical problems? Any sexually transmitted infections? Mortified, Hannah looked down at her hands and mumbled the answers.

“Have you done anything else to try to terminate this pregnancy?” Raphael asked.

She nodded. “I got some pills two weeks ago and, you know, inserted them. But they didn’t work.” She’d paid five hundred dollars for them and followed the instructions she was given carefully, but nothing had happened.

“They must have been counterfeits. About half the stuff out there is. No telling what you’re getting.” Raphael paused. Said, “Look at me, child.”

Hannah met his gaze, expecting judgment and finding, to her surprise, compassion instead. “Are you sure you want to terminate this pregnancy?”

There was that phrase again: not murder your unborn baby or destroy an innocent life, but terminate this pregnancy. How straightforward that made it sound, how unremarkable. Raphael was studying her face. This close to him, she could see the network of tiny broken blood vessels radiating across his cheeks.

“Yes,” she said. “I’m sure.”

“Would you like me to explain the procedure?”

Part of her wanted to say no, but she’d decided before she came that she would not hide from herself the truth of what she was doing here today. She owed it that much, the small scrap of life that would never be her child. She hadn’t dared research the procedure on the net; the Texas Internet Authority closely monitored searches of certain words and topics, and abortion was at the top of the list. “Yes, please.”

Raphael pulled a small flask from his pocket, unscrewed the lid and took a drink—to steady his hands, he said—and then described what he was about to do. His matter-of-fact tone and the clinical terms he used, “speculum” and “dilators” and “pregnancy tissue,” made it sound tidy and impersonal. Finally he asked Hannah if she had any questions. She had already asked and answered the most important ones in her own mind: whether this was murder (yes), whether she would go to hell for it (yes), whether she had any other choice (no). All but one, and it had tormented her ever since she’d decided to do this. She asked it now, her nails digging into the underside of the chair.

“Will it feel any pain?”

Raphael shook his head. “Based on what you’ve told me, you’re only about twelve weeks pregnant. It’s never been proven when fetal pain reception starts, but I can tell you for a fact that it’s impossible before the twentieth week.” Her shoulders slumped in relief, and Raphael added, “It’ll be painful for you, though. The cramping can be severe.”

“I don’t care about that.” Hannah wanted it to hurt. It seemed unconscionable to her, to take a life and not feel pain.

Raphael stood and had another swig from his flask. “Go ahead and undress now,” he said. “Just from the waist down. Then lie on the table with your head at this end. You can use the extra sheet there to cover yourself.”

He went into the adjoining bathroom, closing the door to give her privacy—this man who was about to peer between her spread legs. Hannah was grateful nonetheless for his discretion. She folded her skirt neatly, laid it on the chair and then tucked her panties beneath it, another gesture of decorum she knew to be ludicrous under the circumstances but couldn’t help making. Being naked from the waist down made her feel dirtier somehow than if she were completely nude. Hurriedly, she got on the table and covered herself. Forced herself to say, “I’m ready.”

THE PUNISHMENT TONE sounded, jerking her back into her cell, back into her bleeding body. It all comes down to blood, she thought, as she took the tampons and the wipes from the compartment and used them. Blood that comes out of you and blood that doesn’t. Mechanically, she cleaned the floor, flushed the stained wipes, washed her hands and changed her tunic, making no attempt to shield her nakedness. And when it doesn’t, when you wait and pray and wait some more and still it doesn’t come … She lay down on her side on the sleeping pallet, wrapped her arms around her knees and wept.

HOW MANY DAYS HAD SHE been here? Twenty-two? Twenty-three? She didn’t know, and her ignorance made her anxious. There were gaps of time she couldn’t account for, moments when she seemed to wake from a sleep she suspected had never occurred. She came out of these spells sweaty and hoarse, with a mouth full of cotton. Had she been talking to herself out loud? Raving? Revealing something she shouldn’t have?

She tried to stave off the spells with reading and pacing, but increasingly she felt too listless for either. Her reflection in the mirror had grown gaunt. She had no appetite, and she’d developed the ability to tune out the punishment tone to the point where it was just a distant, annoying whine, like a mosquito flying past her ear. She’d stopped taking her daily showers and her body smelled of stale sweat, but even this was a matter of indifference to her. Her usual fastidiousness had vanished along with her energy.

When she was lucid, the thing she feared most was that she’d said something to betray Raphael. The police had picked her up in the parking lot after a call from a suspicious neighbor, but Raphael had been long gone by that point, and as far as she knew they’d never caught him. She’d given them a false description, waiting until the third time they interrogated her before pretending to break and describing a slender, blond man in his thirties with an Earth First symbol tattooed on his right wrist. What Hannah didn’t know was that the neighbors had seen a heavyset older man leave the apartment. Once the police caught her lying, they were merciless. They questioned her repeatedly, sometimes harshly, other times with an unctuous concern for her welfare that a first grader could have seen through. She stuck to her story, against her lawyer’s advice and despite her father’s entreaties. She would not betray Raphael, with his earnest handshake and sad eyes.

She could have, though. He’d certainly told her enough about himself for the police to identify him. When he’d finished and was cleaning up, and Hannah was still woozy from the painkillers, she’d asked him why he did it. What she meant but didn’t say was, How can you bear to do it? By that point, Raphael had had more sips from the flask and was in a talkative mood. He told her he’d been an OB/GYN in Salt Lake City when the superclap pandemic broke out (the crude slang term discomfited her; in her world, it was always referred to as “the Great Scourge”), and Utah became the nexus of the conservative backlash (“the Rectification”) that led to the overturning of Roe v. Wade. The decision had been cause for celebration in the Payne household, but Raphael spoke of it with anger, and of the Sanctity of Life laws Utah had passed soon afterward, with outrage. Even more abhorrent to him than the lack of exceptions for rape, incest or the mother’s health was the abrogation of doctor-patient privilege. Legally, he was bound to notify the police if he found evidence that a patient had had a recent abortion; morally, he felt bound not to. Morality won. When he got caught falsifying the results of pelvic examinations, the state took away his medical license, and he left Salt Lake City for Dallas.

Hannah had been eleven when Texas passed its own version of the SOL laws. Not many doctors had openly protested, but the ones who had were vociferous. She could still remember their impassioned testimony before the legislature and their angry response when the laws, which were almost identical to Utah’s, inevitably won passage. Most of the objectors had left Texas in protest, and their like-minded colleagues in the other forty states that eventually passed similar statutes had followed suit. “Good riddance to them. California and New York can have them,” her mother had said, and Hannah had felt much the same. How could anyone sworn to preserve life condone the taking of it or seek to protect those who’d taken it, especially when the future of the human race was at stake? That was the third year of the scourge, and though no one close to Hannah had caught it, they were all infected by the fear and desperation that gripped the world as increasing numbers of women became sterile and birthrates plummeted. The prejudicial nature of the disease—men were carriers, but they had few if any symptoms or complications—hindered efforts to detect and contain it. In the fourth year of the pandemic, Hannah, along with every other American between the ages of twelve and sixty-five, went in for the first of many mandatory biannual screenings, and by the time the cure was found in the seventh year, there’d been talk of quarantining and compulsory harvesting of the eggs of healthy young women, measures that Congress almost certainly would have passed had the superbiotics come any later. As distressing as the prospect had been, Hannah was well aware that if she lived in a country like China or India, she would have already been forcibly inseminated. Humanity’s survival demanded sacrifices of everyone, moral as well as physical. Not even her parents had objected when the president suspended melachroming for misdemeanor offenses and pardoned all Yellows under the age of forty, ordering that their chroming be reversed and their birth control implants removed. And when he’d authorized the death penalty for kidnapping a child, Hannah’s parents had supported the decision, though it went against their faith. Child-snatching had become so endemic that wealthy and even middle-class families with young children traveled with bodyguards. Hannah and Becca were too old to be targets, but their mother still glared at any woman whose eyes rested on them too hungrily or for too long. “Remember this, girls,” she’d say when they encountered one of the childless women who loitered like forlorn ghosts around playgrounds and parks, in toy stores and museums. “This is what comes of sex outside of marriage.”

And this, Hannah thought now, studying her red reflection in the mirror. She’d been so certain of everything in those days: that she’d never have premarital sex, never be one of those sad women, never, ever have an abortion. She, Hannah, was incapable of such terrible wrongdoing.

It still surprised her that Raphael hadn’t seen it as such. In his mind, it was the SOL laws that were wrong, and those who espoused them who were guilty of a crime. His deepest contempt was reserved for other doctors: not just those who’d supported and enforced the laws, but also those who’d remained mute out of fear. When Hannah asked him why he’d stayed in Texas instead of going to one of the pro-Roe states, he shook his head and took a swig from the flask. “I suppose I should have, but I was young and hotheaded, saw myself as a revolutionary. I let them talk me into staying here.”

“Who?”

Raphael froze momentarily and then turned away from her, visibly agitated. “Her, I mean, my wife—that’s what I meant to say. She’s from here. She wanted to be near her sister, they’re very close.” He fumbled to close his bag, and Hannah didn’t need to see the bare fourth finger of his left hand to know he was lying.

She felt a dull cramping sensation in her abdomen and clutched it involuntarily.

“You can expect quite a bit of cramping and bleeding for the next several days,” Raphael said. “Take Tylenol for the pain, not ibuprofen or aspirin. And stay off your feet as much as you can.”

He went to the door and paused with his hand on the knob. “The money. Did you bring it?”

“Oh. Yes. Sorry.” Hannah looked in her purse, took out the cash card she’d bought that morning and handed it to him. He thrust it into his pocket without even checking the amount.

“Lights off,” he said. The room went black. Hannah heard him open the door and exhale loudly, with what sounded like relief. “Wait ten minutes, then you can leave.”

“Raphael?”

“What?” he said, impatient now.

“Is that how you think of yourself? As a healer?”

He didn’t answer right away, and Hannah wondered if she’d offended him. “Yes, most of the time,” he said finally. She heard his footsteps crossing the apartment, the bolt being turned, the front door closing behind him.

“Thank you,” she said, into the empty dark.

THE CELL WENT suddenly dark, disorienting her. Had the tones sounded? She hadn’t heard them. She groped her way to the platform and lay down on her back, lost in memory. Raphael had been so gentle with her, so compassionate. So different from the police doctor who’d examined her the night of her arrest. A woman only a little older than Hannah, with cold hands and colder eyes, who’d probed her body with brutal efficiency while she lay splayed open with her ankles cuffed to the stirrups. When she winced, the woman said, “Move again, and I’ll call the guard to hold you down.” Hannah went rigid. The guard was young and male, and he’d muttered something to her as the policeman led her past him into the examination room. She’d heard the word cunt; the rest was mercifully unintelligible. She clenched her teeth and lay unmoving for the rest of the exam, though the pain was fierce.

Pain. Something sharp jabbed her in the arm, and she cried out and opened her eyes. Two glowing white shapes hovered above her. Angels, she thought dreamily. Raphael and one other, maybe Michael. They spun around her, slowly at first and then faster, blurring together. Their immense white wings buffeted her up into heaven.

WHEN THE LIGHTS CAME ON, Hannah’s lids opened with reluctance. She felt thick-headed, like her skull was stuffed with wadding. She pushed herself to a sitting position and noticed a slight soreness in her left wrist. There was a puncture mark on the underside, surrounded by a small purple circle. She studied herself in the mirror, seeing other subtle changes. Her face was a little fuller, the cheekbones less pronounced. She’d put on weight, maybe a couple of pounds, and although she was still groggy, her lethargy was gone. She dug through her memories, unearthed the two white figures she’d seen. They must have sedated her and fed her intravenously.

Something about the cell felt different too, but she couldn’t put her finger on what. Everything looked exactly the same. And then she heard it: a high-pitched, droning buzz coming from behind her. She turned and spied a fly crawling up one of the mirrored walls. For the first time in twenty-some-odd days, she wasn’t alone. She waved her arm and the fly buzzed off, zipping around the room. When it settled she waved her arm at it again, for the sheer pleasure of seeing it move.

Hannah paced the cell, feeling restless. How long had she been unconscious? And how much longer before they released her? She hadn’t allowed herself to think beyond these thirty days. The future was a yawning blank, unimaginable. All she knew was that the mirrored wall would soon slide open, and she’d walk out of this cell and follow the waiting guard to a processing area where she’d be given her clothes and allowed to change. They’d take her picture and issue her a new National Identification Card sporting her new red likeness, transfer the princely sum of three hundred dollars to her bank account and go over the terms of her sentence, most of which she already knew: no leaving the state of Texas; no going anywhere without her NIC on her person; no purchasing of firearms; renewal shots every four months at a federal Chrome center. Then they’d escort her to the gate she came in by and open it to the outside world.

The prospect of crossing that threshold filled her with both longing and trepidation. She’d be free—but to go where and do what? She couldn’t go home, that much was certain; her mother would never allow it. Would her father be there to pick her up? Where would she live? How would she survive the next week? The next sixteen years?

A plan, she thought, forcing down her growing panic, I need a plan. The most urgent question was where she’d live. It was notoriously difficult for Chromes to find housing outside the ghettos where they clustered. Dallas had three Chromevilles that Hannah knew of, one in West Dallas, one in South Dallas and a third, known as Chromewood, in what used to be the Lakewood area. The first two had already been ghettos when they were chromatized, but Lakewood had once been a respectable middle-class neighborhood. Like its counterparts in Houston, Chicago, New York and other cities, its transformation had begun with just a handful of Chromes who’d happened to own houses or apartments in the same immediate area. When their law-abiding neighbors tried to force them out, they banded together and resisted, holding out long enough that the neighbors decided to leave instead, first in ones and twos and then in droves as property values went into a free fall. Hannah’s aunt Jo and uncle Doug had been among those who’d held out too long, and they’d ended up selling to a Chrome for a third of what the house had been worth. Uncle Doug had died of a heart attack soon afterward. Aunt Jo always said the Chromes had killed him.

Hannah quailed at the thought of living in such a place, surrounded by drug dealers, thieves and rapists. But where else could she go? Becca’s house was out too. Her husband, Cole, had forbidden her to see or speak to Hannah ever again (though Becca had violated this prohibition several times already, when she’d visited Hannah in jail).

As always, the thought of her brother-in-law made Hannah’s mood darken. Cole Crenshaw was a swaggering bull of a man with an aw-shucks grin that turned flat and mean when he didn’t get his way. He was a mortgage broker, originally from El Paso, partial to Western wear. Becca had met him at church two years ago, a few months before their father was injured. Their parents had approved of him—Becca wouldn’t have continued seeing him if they hadn’t—but Hannah had had misgivings from early on.

They surfaced the first time he came to supper. Hannah had met Cole on several occasions but had never spoken with him at length and was eager to get to know him better. Though he and Becca had only been dating about six weeks, she was already more infatuated than Hannah had ever seen her.

He was charming enough at first and full of compliments: for Becca’s dress, Hannah’s needlework, their mother’s spinach dip, their father’s good fortune in having three such lovely ladies to look after him. They were having hors d’oeuvres in the den. The vid was on in the background, and when breaking news footage of a shooting at a local community college came on, they turned up the volume to watch. The gunman, who’d been a student there, had shot his professor and eight of his classmates one at a time, posing questions to them about the Book of Mormon and executing the ones who answered incorrectly with a single shot to the head. When he’d finished quizzing every member of the class, he’d walked out of the building with his hands up and surrendered to the police. The expression on his face as they shoved him into the back of a squad car was eerily peaceful.

“Those poor people,” Hannah’s mother said. “What a way to die.”

Cole shook his head in disgust. “Nine innocent people murdered, and that animal gets to live.”

“Well,” Hannah’s father said, “he won’t have much of a life in a federal prison.”

“However much he has is too much, as far as I’m concerned,” said Cole. “I’ll never understand why we got rid of the death penalty.”

Becca’s eyes widened, reflecting Hannah’s own dismay, and their parents exchanged a troubled glance. The Paynes were against capital punishment, as was Reverend Dale, but the issue was a divisive one within both the church and the Trinity Party. Soon after he’d been made senior pastor at Ignited Word, Reverend Dale had come out in support of the Trinitarian congressional caucus that cast the deciding votes to abolish the death penalty over the vehement objections of their fellow evangelicals. Hundreds of people had quit the church over it, and Hannah’s best friend’s parents had forbidden their daughter to associate with her anymore. The controversy had died down eventually, but Hannah’s friend had never spoken to her again, and eight years later, the subject was still a sensitive one for many people.

The silence in the den grew awkward. Cole’s eyes skimmed over their faces before settling on Becca’s. “So, you agree with Reverend Dale,” he said.

“ ‘Vengeance is mine, saith the Lord,’ ” said Hannah’s father.

“We believe that only God can give life, and only He has the right to take it.”

“Innocent life, yes, but murder’s different,” Cole said. “It says so right in the Bible. ‘Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed.’ ” He hadn’t taken his eyes off Becca. Hannah could feel the force of his will pressing against her sister.

Becca hesitated, looking uncertainly from Cole to their father. “Genesis does say that,” she said. “And so does Leviticus.”

“Leviticus also says people should be stoned to death for cursing,” Hannah said. “Do you believe that too?”

“Hannah!” her mother rebuked. “Do I have to remind you that Cole is a guest in our house?”

“I was speaking to Becca.”

“That’s no way to talk to your sister either,” Hannah’s father said, in his most disappointed tone. Cole’s eyes and mouth were hard, but Becca’s expression was more stricken than angry.

Hannah sighed. “You’re right. I’m sorry, Becca, Cole.”

Becca nodded acceptance and turned to Cole. The naked hopefulness with which she looked at him told Hannah this was no mere infatuation. Her sister couldn’t bear conflict among those she loved.

“No, it’s my fault,” Cole said, addressing Hannah’s parents. His face turned rueful, but his eyes, she noted, were a few beats behind. “I never should have brought the subject up in the first place. My mama always said, ‘When in doubt, stick to the weather,’ and Lord knows my daddy tried his best to beat it into me, but my tongue still gets the better of my manners sometimes. I apologize.”

Becca beamed and shot Hannah a look: See? Isn’t he wonderful?

Hannah made her lips curve in answer. She did see, and she could only hope that she was wrong. Or if she was right, that Becca would see it too.

But Becca’s feelings for Cole only grew stronger, and Hannah’s qualms deeper, especially after their father was injured. He was in the hospital for ten days and incapacitated for another month after that, and his absence left a void into which Cole stepped eagerly. He became the unofficial Man of the House, always there to fix the leaky sink, oil the rusty hinges, dispense advice and opinions. Becca was delighted and their mother grateful, but Cole’s ever-presence in the house put Hannah’s back up.

More than anything, she disliked his high-handedness with Becca. Their parents had a traditional marriage, following the Epistles: a woman looked to her husband as the church looked to God. John Payne was the unquestioned authority of the family and their spiritual shepherd. Even so, he consulted their mother’s opinion in all things, and while he didn’t always follow her counsel, he had a deep respect for her and for the role she played as helpmeet and mother.

Cole’s attitude toward Becca was different, with troubling overtones of condescension. Becca had never been strong-willed, but the longer she was with him, the fewer opinions she had that weren’t provided by him. “Cole says” became her constant refrain. She stopped wearing green, because “Cole says it makes my skin look sallow,” and reading fiction, because “Cole says it pollutes the mind with nonsense.” She gave up her part-time job as a teaching aide because “Cole says a woman’s place is with her family.”

Hannah kept her growing aversion to herself, hoping that Becca’s ardor would cool once their father was well again, or failing that, that he would discern Cole’s true character and dissuade her sister from marrying him. In the meantime, Hannah did her best to be cordial to him and was careful not to challenge him openly or express her doubts to Becca. Confrontation was not the way to defeat him; better to bide her time and let him defeat himself.

But she’d overestimated both her skill as an actress and her forbearance, as she discovered on Becca’s birthday. Their father had been home for two weeks, but he still wasn’t strong, so they kept the party to the immediate family—and Cole, of course. Hannah made Becca a dress out of soft lavender wool, and their parents bought her a small pair of opal earrings to match the cross they’d given her the year before.