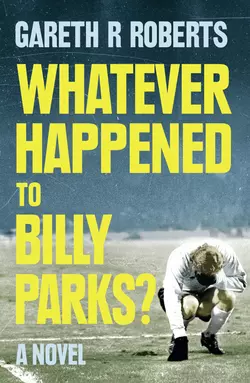

Whatever Happened to Billy Parks

Gareth Roberts

2014 JERWOOD FICTION UNCOVERED PRIZE WINNERLONGLISTED FOR THE 2014 GORDON BURN PRIZEOctober 17th 1973: the greatest disaster in the history of English football.All England had to do was beat Poland to qualify for the World Cup.They didn’t.They could only draw.Left on the bench that night was a now forgotten genius, West Ham’s Billy Parks: beautiful, gifted and totally flawed.Fast-forward forty years, Billy’s life is a testament to wasted talent. His liver is failing and he earns his money selling football memories on the after-dinner circuit to anyone who’ll listen and buy him a drink. His family has deserted him and his friends are tired of his lies and excuses.But what if he could be given a second chance? What if he could go back in time and win the game for England? What if he was able to undo the pain he’d caused his loved ones?The Council of Football Immortals can give him that chance, just as long as he can justify himself, and his life, to them.This is the story of Billy Parks: a man who bore his genius like a dead weight and who now craves that most precious of things – the chance to put things right.

Whatever Happened to Billy Parks?

GARETH R ROBERTS

For Eirlys Ann Roberts

‘Some people believe football is a matter of life and death. I’m very disappointed with that attitude. I can assure you it is much more important than that.’

Bill Shankly

Contents

Title Page (#u79da64a9-15d0-5fd4-be56-3da7a4cba7cd)

Dedication (#ude1087ad-6f0d-5308-ac91-af3e1ac8f26a)

Epigraph (#ub75a20c0-34ae-5cdf-b04f-67cd10e6edaf)

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Also by Gareth R Roberts

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher

Prologue (#udf1a4d3f-a94d-5ad4-bdfe-1a7d25e3c762)

17 October 1973

Wembley

The Unbearable Weight of Failure

They had to win. That was all.

If they won, everything would be alright. If they won, there would be happiness; the rest of the English autumn would be mellow and misty, then the winter would be brilliant white with snow, and Christmas would be merry, then the spring would prosper giving rise to a World Cup in the summer in West Germany.

They just had to win. That was all. Against Poland. That’s all.

We all remember it; even if you weren’t born, even if you hate football, even if you don’t remember it, you remember it because everything changed that night. That night, all they had to do was win. They didn’t win. They drew.

Mr Clough had said their goalie was a clown. And Mr Clough was always right. The BBC showed the game live so that we could all revel in the joyous tension that would precede the campaign to reclaim the World Cup, England’s World Cup.

Sir Alf picked three strikers: Channon, Chivers and Clarke. They would score, because the Polish goalie was a clown.

And Billy Parks was on the bench.

Billy Parks: the best of all of them; the most natural, the most beautiful, the most easily distracted, as he carried the immense weight of his talent on his slender shoulders.

The Polish Clown saved from Chivers.

The Polish Clown saved from Currie.

The Polish Clown saved from Clarke, then Channon, then Channon again.

Then. Then. Then. Norman Hunter didn’t tackle Lato, the Polish midfielder. Norman Hunter, who normally took bites out of human legs, who never let anyone past him, missed the tackle and Lato played it through to Domarski who sent it tamely past Shilton. They weren’t winning. They were losing.

Attack.

The Polish Clown saved from Chivers and Channon and Clarke and Hunter and Bell.

Then Clarke scored a penalty. But that wouldn’t be enough. They had to win.

And Billy Parks sat on the bench. In between Kevin Keegan and Bobby Moore. His knees drawn into him against the cold, his mind wandering to the two hundred and fifty quid he’d bet on an England win.

A win that would make everything alright. A win would bring colour to the grey beige of the seventies. A win would change everything.

But the Clown saved every shot that came his way.

So Sir Alf looked to his bench. Destiny called for someone. Sir Alf looked at his bench and thought about which valiant hero would bring forth triumph. Who would forge their name in the fires of destiny. Score a bloody goal.

Billy Parks sat, cold. He avoided Sir Alf’s gaze, his mind on the barmaid from the Golden Swan whom he would pick up later in his inferno-red TR6.

Eventually, because he knew he had to, he looked up. Five minutes to go. He looked towards Sir Alf and Sir Alf looked away from him and called upon Kevin Hector. Kevin Hector would deliver the goal. Kevin Hector would make everything alright. He had scored over 100 goals for Derby County. He was reliable. We would be alright – wouldn’t we?

England got a corner. Tony Currie swung it in. For once, the Clown was nowhere, he was beaten by the flight of the ball. The ball fell on to the head of Kevin Hector. This was his chance. This was his chance. This was his destiny. He headed it towards the goal. The Clown was beaten.

Kevin Keegan and Bobby Moore rose up from the bench. Billy Parks didn’t move.

The ball went towards the goal. Just a ball heading through time and space. It means nothing. It means absolutely everything. All England has to do is win. One goal would do it.

The ball left Kevin Hector’s head and went towards the goal-line. Everyone stood up, everyone waited for the goal, everyone waited for the triumph, for the tension to be broken, for everything to be alright. But it wasn’t a goal. The net didn’t bulge. A Polish defender kicked it off the line.

Keegan and Moore sat down again. Sir Alf sat down again. Parksy looked towards the crowd. The mass of grey faces. Kevin Hector’s destiny was fulfilled. The man who missed the chance.

If only things had been different.

Perhaps they could have been.

Perhaps they could be.

(Taken, in part, from the little known, but highly acclaimed, 1977 biography of Billy Parks, Parksy: The Lost Genius of Upton Park, by veteran Sunday Times football journalist, Philip Clarence.)

1 (#udf1a4d3f-a94d-5ad4-bdfe-1a7d25e3c762)

There are two bar stools on the small makeshift stage.

One for me, and one for my whisky tumbler. The crowd like that. A little visual joke, just to break the ice, just to make them relaxed. I’ve been doing that for years.

I’m sixty-odd now. I still tell people I’m fifty-eight, but with the bloody internet and Wiki-whatsit, every bastard knows that I was born in 1948, which makes me, well, sixty-odd.

Christ, sixty-odd? How did that happen? How did the years crumble away so bloody quickly? Sixty-odd, but still in good nick I reckon; like a well-preserved Dodo, rendered ageless in a glass cage by the blurred images of my youth that I know the crowd prefer to keep in their memories: Sunday afternoons with Brian Moore; Saturday nights with Jimmy Hill after Parkinson with a cup of tea; Peter Jones’s dulcet Welsh tones; Harold Wilson: Ford Capris; the Yorkshire bloody Ripper. It’s all up there in flock wallpaper purple with me somewhere in the midst of it making my way down the wing at Upton Park or the Lane.

Sixty-odd now. Still got all my hair though – well most of it – even if the happy blond is rudely interrupted by the odd bit of dirty grey. I’ll admit that, but, hey, I am sixty-odd.

I smile at the crowd. There are about twelve of them here. A few more are by the bar getting a round in before I start. I don’t blame them. This is a drinking afternoon. Drink’s part of it, of course it is.

They look at me and I know that they don’t care about the deep black ridges under my eyes, or this suspicious purple brown spot that has recently appeared on my cheek. I smile again, with my eyes twinkling just as they remember and my teeth glistening like a Hollywood starlet (courtesy of a bit of work I had done a couple of years ago using the last of my testimonial money). I am still capable of lighting up a room, still capable of sending a full-back the wrong way.

I am Billy Parks.

I lift the cheap whisky tumbler, neat, of course, and drink it. That’s for them. They expect it. It’s part of the legend.

The last of the drinkers take their seats and I notice the poster on the wall above the bar, handwritten in black marker pen proclaiming:

SPORTSMAN’S LUNCH AT THE ANCHOR,

This Tuesday, 14th March, 1pm

Former West Ham, Spurs and England Legend, BILLY ‘PARKSY’ PARKS.

Ticket £5 (includes free pint of Foster’s)

(Samantha and her Boa will be back next week)

Bless ’em.

They had cheered when I came on to the stage, ‘Parksy, Parksy, Parksy,’ they had chanted. Drink helps all of us.

I wave in a quiet understated way and they smile and sit back in expectation of an hour’s drinking and a good laugh. I wonder how many of them have actually seen me play? But that doesn’t matter; they all know the stories, and that is what they’re here for – the stories and the brief journey into a world they all feel they know and belong to.

I like to think that I don’t disappoint; hell, I’ve been telling the same stories for twenty-odd years.

‘Good afternoon, gentlemen. Good to see that so many of you have used your day release from Parkhurst to be with me today.’

They laugh. I knew they would.

I go into my spiel and ignore the two fat City-boy types who are standing at the bar, talking loudly, probably about money; I even ignore the bloody fruit machine by the exit that, for some reason known only to the evil misguided bleeder who designed it, lights up like tracer fire every ten minutes and plays the opening bars from Coronation Street at top volume. I’ve told Alan, I don’t know how many times, to turn the bloody thing off when I’m on stage.

I tell them football stories, because that is what they’ve come to hear. I tell them about the characters of my era – proper characters, true lions of another better time, long passed over into the realm of myths and legends with the telling and retelling of tales. I tell them of their drunken exploits, their sexual exploits, the fights, the put-downs, the fast cars, the funny stories that made them godlike and mortal at the same time. I tell them of the managers who were hard bastards, and lunatic chairmen. I tell them about magical footballers, old friends, whose very names conjure up colours and tastes and sounds and sensations and people long gone: Georgie Best, Rodney Marsh, Chopper Harris, Norman Hunter, Alan Hudson, Charlie George, Frankie Worthington – legends each and every one of them.

I tell them about a tot of rum before kick off and a sneaky fag at half-time, fish and chips on the bus on the way back from Newcastle and the time Terry Neill got so angry at Loftus Road that he put his foot through the changing room door and missed the second half as a couple of stewards and our kit man tried to pull his leg out. I tell them that they were good honest pros, though. Good. Honest. Pros. And the crowd fills itself with lager and scampi and smiles and feels, for a few minutes, closer to that time, closer to the legends, and that feeling that if there had been any justice it would have been them. I know that they all think that. I’ve always known it. It’s the way they look at you. You were one of the lucky ones, Parksy. Luck: it’s got nothing to do with luck, son.

I’ve emptied the glass on the other bar stool, so I turn towards the bar and wordlessly call for another. And another. Fair play, Alan treats me well at The Anchor.

Any questions?

The same questions I’ve been asked a thousand times. I don’t mind.

Who was the best player you ever played against?

I sip my drink as the question’s asked, then I answer as the alcohol surges down my throat and loosens the connection between my tongue and my mind and my memory. They expect it.

‘The best player – that’s easy,’ I tell them. ‘Georgie Best.’ Hushed respectful tones and thin lips when talking about Georgie; the best player ever to grace a football pitch, bar none. God rest his mad Irish soul.

Who was the hardest opponent?

‘Paul Reaney – Reaney the Meanie of Dirty Leeds. The others would try to kick you, but he was the only one who was fast enough to catch you –’ I pause ‘– then he’d kick you.’ They laugh. Oh, yes, Paul Reaney, dirty, hard, fast bastard. I smile at the thought of being kicked by a good honest pro. ‘Good bloke,’ I add quietly, because I mean that. And that’s what good honest pros did – a kick, then a handshake and a few beers in the players’ lounge bar after the match. None of the nonsense you get with footballers these days, with their fancy cars and their fancy agents and their one hundred and ten fucking grand a week.

Not that I blame them.

I’ve answered these questions thousands of times. I’ve emptied a thousand glasses. I’ve smiled on thousands of fans. This is easy money, money for my memories and a few minutes of adulation to remind me that I’m still alive.

I’m getting warmed up now. The crowd is a good one, suitably boisterously pissed and attentive to all my best stories. I’ve become good at this.

My eyes wander towards the back of the pub, and there, standing close to the blessed Coronation Street fruit machine, stands a man in a tan sheepskin coat and trilby. There’s something familiar about him, something about the thick furious grey eyebrows that explode across a forehead that’s creased and serious. I know I’ve seen those eyebrows before, but where?

I catch him watching me intently, his face a humourless shade of thunderbolt grey. For a second I meet his stare, just a second. Where the bloody hell have I seen him before?

I turn away just as the man’s voice cuts through the muggy atmosphere of the pub to ask a question.

‘What would you give to turn the clock back and put a few things right?’ he asks.

God, not that old chestnut. I try to stifle the furrowing of my brow. There’s something about the way in which he asks the question though; it lacks the smiling compassion that usually accompanies my inquisitors. There’s a cold, understated masculine aggression to it. Perhaps he is one of the nutters that I sometimes get. Sad, bitter, twisted old bastards – back in the day, they’d want to fight me; now, occasionally, they want to humiliate me.

I pour more of the cheap neat whisky into my mouth. I can deal with it – I’ve heard this type of question a thousand times before:

If you could change anything, what would it be?

Do you have any regrets?

Where did it all go wrong?

I know exactly how I will answer it. I know that my mouth will form itself into a quick smile before opening and allowing meaningless soft words to tumble out like little balls of cotton wool harmlessly falling on to a bouncy mattress. Puff.

I put on my most sincere voice and answer, as the man in the sheepskin coat stares: ‘Football has given me a very lovely life and great memories,’ I tell him. ‘I wouldn’t change a second of anything. I’ve been very lucky.’ I pause, then smile. ‘And so have hundreds of birds and everyone in north and east London that was lucky enough to see me play.’

I grin, some of the audience chuckle, but the man’s expression doesn’t change, which gives me a sharp pang of discomfort, as though I was being chastised by an old and respected uncle. Well, sod that. I glance towards the bar, where the barmaid, Leanne, a rather hefty girl who obviously likes a bit of artificial tanning, stands bored, cradling her chin in her hands. Thirty years ago we might have been up for a bit of fun later – but not now.

It’s time to finish.

I turn again to the audience and ignore the bloke in the sheepskin coat.

‘Right, gentlemen, thank you very much, you’ve been lovely.’

The crowd applaud. Not Anfield, not Stamford Bridge, not Wembley Stadium or the San Siro, not the deep, pure, momentary masculine love of an adulating crowd roaring after the ball has ripped into the net, but smiling faces and clapping hands and a muted sincere cheer.

‘Thank you very much, fellas,’ I repeat. ‘I’ll tell you what, if any of you want to ask any more questions, I’m happy to oblige over by the bar.’

I always do this. I know that a little coterie of drinkers will surround me, try to get closer to me, close enough to breathe my air and buy me drinks and talk to me as if I’m one of the lads, one of them: ‘So, what do you think about the Hammers, eh? It’s a fucking disgrace.’

I’m not one of the lads. But I will be for a drink. They expect it.

‘You havin’ a drink with us, Parksy?’

‘Thank you very much, mate – I’ll have the same again. Yes, the Hammers – fucking terrible, I’ve not been down there for a while.’

After about an hour the crowd leaves: happy, drunk sportsmen. I’m alone. Alan, the landlord, a large man who wears brown short-sleeved shirts and steel-rimmed glasses, comes over.

‘You alright to get home, Billy?’

‘Don’t worry about me.’

‘You sure?’

He looks carefully at me. ‘Did you know that your pupils have gone yellow? You should watch that.’

Yellow? What does he mean yellow? The daft bastard.

‘It must be something you’re putting in your scotch to water it down with,’ I say, and he grins at me with concerned eyes.

‘Here you go, son,’ he says, handing me a brown envelope. ‘Forty quid, I’ve taken out the twenty you owe for your tab, alright?’

I nod. I’m not going to quibble over a few quid.

I leave the safety of The Anchor, stepping out into the late afternoon. The pub door shuts behind me and the south London air stings my eyes. I hate that, I hate that moment when the pub door shuts and the moroseness hits you. The devastating lonely feeling of insignificance. My past means nothing under the massive spitting sky. Cars whip by creating movement and noise in the gloom. They ignore me. They don’t know who I am. But if they did, if they had seen me …

I stumble, then grab hold of the railings by the side of the road. Better take myself to The Marquis close to the park. Yes, there would be friendly faces there, friendly faces and the same conversations and the same drink: people to tell me how worthwhile my life has been, people to love me. Perhaps Maureen, the landlady, will be there and I might find solace in her comfortable body.

I start to walk; my knees hurt, the result of Paul bloody Reaney no doubt, him and the hundreds of others without an ounce of talent who’d been told to kick me as hard as they fucking-well could. I feel tired. I rub my eyes and start to cross the road.

‘You didn’t answer my question, Billy?’

I turn around abruptly, drunkenly, to see the man in the sheepskin coat and trilby walking towards me. My eyes narrow as I try to focus on the man’s face. Where the bloody hell do I know him from? There was something familiar about him.

‘I know you, don’t I?’

‘I should hope so,’ he says, and he smiles slowly and mechanically at me.

I stagger slightly and move my head back trying to get a better look at him, to picture him, put a name to the face, put an age to the face.

‘I’m sorry, mate,’ I say. ‘I can’t remember. You’ll have to remind me.’

‘Come on,’ says the man ignoring the request. ‘Let’s take a walk through the park.’

We walk through Southwark Park. Some kids kick a ball on a strip of concrete. We stop and watch them: it’s what old football men do.

‘You see that?’ asks the man in the sheepskin coat.

And I turn to face him. I’d seen nothing of worth in the boys’ kick-about and am starting to feel a bit weird, light headed, there is something about this man that confuses me, weakens me, makes me feel ill.

‘The grass, Billy,’ the man continues. ‘Those boys are playing on the concrete because the grass on the park is useless. It’s just mud.’

I look at the empty field, heavy and rutted with green and brown, then back to the boys.

‘Not many people know this, but the grass on that park is Bahia grass which comes from South America. Did you know that, Billy?’

I shake my head. I’ve no idea what he’s going on about. Suddenly I want another drink like I’ve never wanted one before.

‘Some clot decided that if the boys of south London were going to play like South Americans, then they should have South American grass.’

‘Oh,’ I say. But I don’t want to stand still talking about grass; the open space of the park is starting to hurt my eyes.

The man in the trilby gives a throaty laugh. ‘Of course, they didn’t realise that Bahia grass would struggle in our climes – it doesn’t grip the soil in the same way, you see. It’s rubbish.’

The man smiles and looks over towards me as I start to feel a warm sensation in my temples.

‘That’s where you know me from,’ he says, warming slightly. ‘Brisbane Road. Gerry Higgs. I was head groundsman and coach at the Orient when you went there as a boy.’

Gerry Higgs, of course, Gerry Higgs. I nod my head slowly then rub my temples. There is sweat rushing down the side of my face. Why am I sweating?

‘Gerry Higgs,’ I mumble. ‘Yes, I remember.’ I look at him, my eyes narrowing and clouding as I examine him more closely – Gerry Higgs. Bloody hell. But that doesn’t make sense. ‘Mr Higgs,’ I say, confused, ‘you were old then – you haven’t changed. Why haven’t you changed?’

‘Ah,’ he says, ‘there’s a reason for that, Billy.’

‘What’s that then?’ I try to muster a clever joke, despite the pounding in my head. ‘Porridge every morning? Cod liver oil before you go to bed?’

‘No son,’ he says. ‘I went into the Service a few years ago.’

Service. Service? What is that? What does he mean, Service? I rub my eyes again – my body becomes heavy. Why? What’s happening?

The man’s eyes train on me. I need a drink. I turn away from him.

‘How’s your daughter, Billy?’ I hear him say, as though he’s talking from another room. I note the slightly sinister tone to his voice. I want to answer but I can’t. I want to ask him why he’s mentioned my daughter, Rebecca. But I can’t. I can’t muster an answer. I hear more words, this time from even further away, ‘And your grandson – what’s his name? Liam isn’t it?’

I’m reeling now. What did Gerry Higgs know about my daughter and the boy?

‘I dunno.’ I’m stuttering, trying to shout. ‘How do you know about them?’

The man smiles. ‘I know everything, son. As I told you, I’m in the Service. And now I want to help you, Billy. I want to help you to put everything right. You do want that don’t you? We can do that in the Service.’

There was that word again: Service. What does he mean? My eyes blur and I feel something loosen in my mind. I don’t understand. Gerry Higgs. What does he mean – how can he help me? What is the Service? I look around for something to hold on to, and as I do an image forms in my mind of Becky and Liam – my daughter and my grandson. I’m not with them. I haven’t been with them for bloody ages, years. The image is one of longing and spiky, prickly, guilt. Why has Gerry Higgs mentioned them? Gerry Higgs, the groundsman at the Orient who coached the kids and drove the youth team bus on a Saturday. What did it have to do with him?

Was it really him?

I feel a little explosion in my mind then a cloying lightness that spreads throughout my body, starting with my eyes then rippling downwards, jumping from my torso to my knees that suddenly veer in spastic directions.

No balance, no control.

I fall. What’s happening? What the bloody hell is going on?

Is this it? Is this the end? Is this death?

For a few seconds everything is quiet. Nothing. Not a sound. There’s just me, Billy Parks, Parksy, bloody Billy Parks of West Ham United and England, legend, lying, alone, on the ground, crumpled and small and breathing with a violence that makes my body shudder.

I can hear anxious voices in the distance. ‘See that, that old geezer’s fallen over,’ they say and the boys who’d been playing football start to run towards me.

I’m not old, I think.

And my lips move, silently.

I’m Billy Parks.

2 (#udf1a4d3f-a94d-5ad4-bdfe-1a7d25e3c762)

I was six and I’d cried when I had to leave my cousins’ house. I’d gone on the bus with my mother all the way to Dagenham. All the way, just the two of us – her in a pretty cotton dress with red flowers on it, me in my Sunday bib and tucker. It had been the best day of my life. And when it was time to go I’d felt my head go down and sticky silent tears force their way into my eyes: proper painful tears brought on by the awful, heavy, horrible dread that I was going to have to go back home. I wiped them away furiously because you get nothing for crying, Billy.

My cousins’ house had a back garden. My Uncle Eric had ruffled my hair and Aunty Peggy, gorgeous Aunty Peggy, who always smelled of the promise of something exciting that I didn’t yet understand, had smiled this lovely smile at me and my cousins, twins, Bobby and Keith and their sister Alice, as we ran around, laughing out loud, big carefree childish pointless laughs, and shouted and pretended to be Cowboys and Indians. It was the best day of my life and it had made the whispered tick-tock silence of home seem unbearable. I hadn’t wanted to leave. I wouldn’t leave. I would stay – why couldn’t I stay? Even Mother had seemed happy here in her dress with red flowers on it, sitting in the kitchen drinking only tea, smiling at me as I played.

Smiling at me.

God she was beautiful that day.

We’d left, me with my head down and my mother’s hand in between my shoulder blades. I’d sulked all the way to my home where my father, Billy Senior, never ruffled my hair.

Oh my poor, poor father. The poor, poor bastard.

That day, as I played and my mother laughed, he had sat in his usual place in our house, in the open back doorway of our kitchen, looking out at the back yard and up into the east London sky at the clouds that passed on their heavenly journey, waiting for the day when his own celestial cloud would arrive and mercifully take him away. Every day. Every single silent, wasted, disappearing, bloody day.

Sometimes I would stand in the kitchen with a little ball in my hand and look at the back of his head. Other dads played games, I knew this, I’d heard this, so I would shuffle my feet against the lino and make a noise before Mother would arrive and tell me to be quiet and go and do something else on my own.

Home was sad silence. Home was doing things on my own. Home was listening to the footsteps of my sister Carol, who was ten years older than me, clip-clopping across the stone hallway on her way out of the house to wherever it was she went to seek solace. Home was the slow monotone sobs of our mother and my own breathing as I lay on my tummy and played with little toy cars and little wooden animals that I liked to line up in a quiet row.

I had known nothing else, but then I went to my cousins’ house in Dagenham and I discovered a wonderful truth: not all homes were like mine. I was six. I was six and I’d had my hair ruffled and smelled the feminine smell of my lovely smiling aunty. And now, like an addict, I wanted more of that, that wonderful life.

I feel guilty admitting that. I mean, my poor, poor bastard dad. It wasn’t his fault. He’d not always sat mute in the back kitchen. Once upon a time he and Mother had smiled and laughed too, once upon a bloody time he had held her and told her not to worry because he was only going there to ‘mend broken tanks, not to fight’. And she kissed him and pressed her breast against his chest and he had pulled his face away from hers so that he could see her and remember her, and as he looked at her he’d promised, ‘I’ll be fine, it’ll be just like being in Mile End’, and then he’d smiled his lovely smile with his twinkling blue eyes and joked, ‘Only hotter.’

That, I discovered, was 1941 as he left for Burma.

He was taken prisoner the next year and it was another five years until she saw him again. She saw him and she held him, but he never really returned to her. The poor bastard – the poor pair of bastards.

He had tried. Or so I’m told. He had gone back to the garage on Woodgate Road and a pint down The Albion and West Ham on a Saturday afternoon. He had bounced Carol on his knee and smiled because she adored him, and he’d got on with the task of blotting out the images of Burma and the camp at Thanbyuzayat and the corrugated iron shack with the waist-high ceiling that had been his jail and the rats and snakes and scorpions and the slow death brought on by malnutrition and the exhaustion of working day after day on that bloody railway, or the faster, better, death brought on by dysentery and malaria and typhoid.

He got on with the job of blotting out the images of his dead friends and of the camp guards with their sticks and their swords and the ‘Hellship’ home when the Americans accidentally torpedoed them, and the awful, overwhelming gut-wrenching feeling of guilt when he eventually reached home in 1946 and walked down what was left of our street, Scotland Street, in Stratford.

It was the guilt that did it.

At first he could block out the images. He could deal with the pain of loss. His body recovered, he put the weight back on, he was always an athletic man – but the guilt never left him. The guilt grew like a creeping winter shadow, placing everything into cold darkness. And once the guilt had gnawed at everything, stripped him bare, the images couldn’t be blotted out any more.

Even me, little Billy, born in December 1948 and loving him from the moment I first formed a memory, even I couldn’t stop the images that came to him each day: of his mate Eddie Hastings from Romford, who had been a postman – a postman, from Romford, he shouldn’t have been in bloody Burma building railways, he shouldn’t have died in my dad’s arms, incoherent with disease and weakness and thirst; and the big Colour Sergeant, Harry Green, who was executed, and how he had shouted out for his wife and his sons just before they decapitated him; and all the others, all the bloody others, who came to him every day and did their spectral dance around his poor suffering head.

I couldn’t take away those images. Not even when I held my little ball and looked up at him with the same twinkling blue eyes that he had once had.

‘Why are you sitting by the back door, Dad?’ I asked, and I curse myself now, because I know now that my presence, my question, my little bloody ball, would have just added to his guilt.

‘Will you play with me, Dad?’

‘I’m sorry, son, I’m tired. I’m so tired. Maybe tomorrow.’

My poor scared broken dad.

I would nod, disappointed. I wanted him to hold me and I know now, I’m sure now, that he wanted to hold me, but it wouldn’t happen. Ever. He would never play with me.

And as my father sat quietly and neatly waiting for the turmoil in his head to go away, the life was sapped from my mother.

During the war, she’d worked as a clerk for the east London General Omnibus Company keeping tidy ledgers to try to stop herself from worrying. She had worried though, of course she had, every day for five years. Worrying and fantasising and yearning for his twinkling blue eyes and his sandy hair and his lean athleticism and an end to the crushing weight of loneliness.

The man she yearned for never came home.

So she stayed lonely.

And the local women gathered around, because that was what they did round our way. And they helped her when she fell with me after one of the few times Billy Senior had come to her as a man, and they helped her when he stopped going to work, and they helped her when he woke every night crying. They told her that it was alright to have a couple of snifters of Mrs Ingle’s home-made gin from time to time.

But from time to time became every day, so they stopped gathering around.

I would be sent in the morning round to Mrs Ingle’s (always go round the back, Billy) with a coin in my trouser pocket and a note. And Mrs Ingle would ask me how me ma was and how me old man was and give me a flask and send me on my way. Your mother’s tonic, don’t drop it, don’t break it, get home straight away.

I broke it once. Only once. And that was on the day that I discovered football.

I always took the same route to Mrs Ingle’s: up our road, past the corner shop and the Nissen huts, through the lane that ran between Eric Road and Vernon Street and across the waste ground that had, until the Luftwaffe had bombed it into oblivion four years before I was born, been Singleton Street and Sharples Street. Now it was just a derelict piece of ground about the size of, well, the size of a football pitch.

On the day that I discovered football I crossed it on my way to Mrs Ingle’s just like I did most days. Then I went round the back of her house, just as I was told, knocked on the door and was met by Mr Ingle in his vest and braces chewing on a mouthful of thick brown bread. He looked at me witheringly and motioned for me to stay where I was. A little while later Mrs Ingle came to the back door – funny, recently our transactions had become more businesslike. She had stopped asking me about my parents; instead I would silently hand over the money and she would silently hand over the flask, we would exchange a knowing look and off I’d go.

This particular morning was no different. I took the flask and put it into the little brown paper bag, just as I was ordered, and started to walk back home. When I reached the waste ground at Singleton Street there was a football match going on. I knew a bit about football, not much, just bits and pieces I’d picked up from my cousins. What I did know though was that if the bigger boys were playing I would have to walk around the pitch or risk a cuff around the ear from some twelve-year-old psychopath.

Wisely, I started to walk around the makeshift pitch, skipping over the puddles that formed in the blast craters to make sure that I didn’t get my shoes wet. It was the last childish thing I would do because halfway around the pitch my life changed for ever.

‘Oi you, kid.’

I turned around to see an enormous nine-year-old shouting at me. Chris Cockle, his name was, a boy with thick arms and legs and a head of dark wavy hair. He wore his grey V-neck jumper taut across his chest like chainmail. I knew Chris Cockle, everyone knew Chris Cockle. He was a fearless slayer of any beast that crossed his path.

‘What?’ I said, trying to sound somehow more confident than I actually was – a trait that has got me out of countless good hidings over the years.

‘Come on,’ said Cockle, ‘we’re a man short. Put your bag down by the goal, you can play for my team. You can play right-back. You can be Alf Ramsey.’

‘He can’t be Alf Ramsey. He’s just a kid, he’s rubbish.’ The dissenting voice was that of Charlie Scott, who was ten and had a dozen brothers and sisters who would hang around outside their house like cats. Chris Cockle wasn’t having that.

‘If he’s going to play right-back, he’s got to be Alf Ramsey.’

I had no idea whatsoever what they were going on about. I had no idea what right-back meant, never mind the name of Tottenham and England’s Alf Ramsey. I assumed that Alf Ramsey was one of the other lads on his team. All I knew was that if Chris Cockle wanted me to play, then I had no choice – Mother would have to wait for her tonic. I put the bag down by the goalposts, which were made up of a mound of rocks on one side and a stick stuffed into a hole on the other, and strutted cautiously on to the pitch, which was marked by a series of jumpers and coats.

This was serious. This was football and football is more serious than anything else.

‘Come on,’ said another gigantic boy. ‘Go and stand over there, we’re playing the lads from Manor Park. Don’t go near the ball unless I tell you, and if the ball comes to you just kick it to me. Alright? I’m Billy Wright, you’re Alf Ramsey.’

Billy Wright! This was even more confusing, surely the lad who’d introduced himself as Billy Wright was, in fact, Ginger Henderson who lived behind the corner shop and whose dad had been killed in the war. I decided against saying anything.

The game kicked off with the lads from Manor Park attempting to play a long diagonal ball out towards where I had been told to stand. Ginger Henderson (or Billy Wright) went to head it, I moved out of the way, Ginger missed the ball completely and the Manor Park left-wing was left with only the goalie, Lanky Johnson, to beat: thankfully, he put the ball wide of the pile of rocks.

Ginger picked himself up, Lanky Johnson, or Bert Williams as he had taken to calling himself, gave him a bollocking, so Ginger gave me a similar bollocking and the game continued.

This was football.

There were goals and movement and swear words and arguments and kicks and shoves and I loved it all. Lads became spitting, snarling men imbued with a sense of purpose. I started to relax. I started to watch the ball and work out, instinctively, where it would go. I started to watch the movement of my teammates; I worked out that Chris Cockle was good because he was big and fast, but little Archie Stevenson who was sat in the middle of the park, just in front of the enormous water-filled bomb crater (If the ball goes in there, we restart with a drop ball, OK?), was by far the best player, as he could spray passes out to the right and left. On the right, was a little fat boy called Stanley Matthews who was quite good, but the tall gangly boy, called Tom Finney, on the left-hand side, was rubbish because the ball would just bounce off his legs.

Impulsively, like a salmon lured upstream by invisible forces, I wandered from my given position at right-back and made the diametric move to the left-wing. It just seemed the most natural thing for me to do, as though it was where I belonged; I wanted the ball, I wanted to play football, I wanted to kick it, I wanted to be part of this, to feel the rush of scoring a goal, a prospect that caused a pounding of excitement that I had never felt before. Now, playing football, I was alive.

And then it happened. I scored my first goal.

Stanley Matthews, who I would later come to know and adore as Johnny Smith (oh poor, lost Johnny, Johnny Smith), cut in from the right and tried to swing over a cross for Chris Cockle: Chris jumped marginally early and the ball glanced off his bouncy brown hair across the face of the goal towards me. It dropped perfectly. I controlled it – alright, not particularly elegantly with my knee (my beautiful close control would come later) – and then instinctively, without considering anything, without a conscious thought in my little mind, found that my body had naturally formed itself into a position to shoot at the goal.

‘Shoot!’

I shot. With all my tiny six-year-old frame behind it, I shot and the ball headed towards the piece of rusty iron railing that was the near post of the Manor Park goal. Then, with the assistance of the uneven pitch the ball bounced over the goalkeeper’s leg (if he had dived with his hands he would have prevented my first ever goal, but such are the vagaries of sport) and inside the near post.

Goal. Goal. My first goal. My first bloody goal.

I felt my body and mind surge with the glorious fresh air of life. My face beamed triumphantly for the first time. Chris Cockle came over and ruffled my hair. ‘Well done, son,’ he said. ‘What’s your name again?’

‘Billy Parks,’ I said and Chris Cockle smiled at me: ‘Well done, Parksy,’ he said, then turned to the opposition with a bellowing, captain’s roar: ‘That’s eight all. Next goal the winner.’

Next goal the winner. Next goal was a cause of problems and strife.

As I chased everything on the pitch, and some of the lads started to feel a bit tired, our team became vulnerable to a break-away attack. The Manor Park centre-half, Lennie Hansen, kicked long, Ginger didn’t deal with it and the Manor Park striker, a talented little lad called Spider, who was later destined to drown in an accident involving an old well, nipped in and steered the ball past Lanky Johnson. The ball clipped the piece of wood knocking it over on to the paper bag that contained Mother’s tonic.

All hell broke loose. As Spider reeled off in celebration, Chris Cockle, Ginger Henderson and Charlie Scott declared that it wasn’t a goal as it had hit the post. Lennie Hansen wasn’t having this and he and a couple of the other Manor Park lads squared up to them.

As Chris and Lennie, now reinforced by most of the other players, exchanged blows, I ran over to my brown paper bag and surveyed the damage: the flask had smashed and the tonic had seeped out emitting a pungent oily smell. I put my hands up to my head. This was bad.

I walked home. I knew that the broken flask was a tragedy. I knew I had to think of a good lie, a good story, but all I could think about was my goal. How the ball had left my foot and how the other boys had shouted ‘Shoot!’ and I had smashed it into the near post, and how everyone had smiled at me, and how Chris Cockle had ruffled my hair and asked my name and christened me Parksy. This was what life was about. This was an elevation above and beyond the mere existence of my usual days. This was living.

But the flask was still smashed. The goal couldn’t mend that.

Back at home Carol was waiting for me. Her face swollen with tears and rage.

‘Where have you been, you idiot? Mum’s been waiting for you all morning. You know you’re supposed to come straight back from Mrs Ingle’s. Where have you been?’

‘I’ve been playing football,’ was all that I could muster.

She screamed at me, ‘Football? Football? Who cares about bloody football?’ She paused, then seethed through gritted teeth, ‘Just give me the bottle.’

She held her hand out and my head dropped.

‘It got broken. It was an accident. I didn’t mean for it to happen,’ I was mumbling.

Carol started screaming at me again.

My mother appeared at the bottom of the stairs: her face was lined and taut and anxious. ‘Where’s the bottle from Mrs Ingle’s, Billy?’

‘He’s broken it, Mum,’ my sister squealed. ‘He’s been playing football.’

I saw my mother’s face break into a desperate ugly rage, and she advanced on me and rained down blows on my head and back in syncopated rhythm as she scolded me.

‘You silly, silly boy. I-only-asked-you-to-do-one-thing. You silly, silly boy.’

As the force of the blows diminished, I looked up, my own face now a mass of rushing tears, and I could see through the kitchen the back of Father’s head tilted upwards, looking, as ever, towards the heavens.

‘Dad,’ I shouted through sobs. ‘Dad, I scored a goal. You should have seen my goal. Stanley Matthews crossed it and I smashed it into the net.’

Father didn’t turn around.

A few weeks later they fished him out of the canal.

Details: Match 1, March 1955

Venue: The Waste Ground by Singleton Street

Chris Cockle’s XI 8 v. Lads from Manor Park 8

(Match abandoned after brawl erupts following Eddie ‘Spider’ Linton’s controversial disputed winner)

Line up: Lanky Johnson (Bert Williams), Billy Parks (Alf Ramsey), Tommy Weston (Bill Eckersley), Ginger Henderson (Billy Wright), Topper Winters (Jimmy Dickinson), An Other (some lad with glasses who was never seen again), Archie Stevenson (Alfredo Di Stefano), Peter Scott (Wilf Mannion), Johnny Smith (Stanley Matthews), Chris Cockle (Ferenc Puskas though changed to Nat Lofthouse shortly after half-time), Brownie Brown (Tom Finney)

Sadly, other than Lenny Hansen and Eddie ‘Spider’ Linton, the Manor Park line up has been lost in time.

Attendance:6 (including Charlie Scott’s little sisters and a policeman who arrived to break up the fight)

3 (#udf1a4d3f-a94d-5ad4-bdfe-1a7d25e3c762)

The first thing I see is the drip. I know it’s a drip and that must mean that I’m in a hospital. But I can’t for the life of me think why? The last thing I remember is looking at the grass on Southwark Park. What was it about the grass?

I look at the drip and see a little blurry bubble – which may be a droplet of my blood – make its way down the drip-line towards the needle that leads, via a vein in my hand, to me.

I’m uncomfortable: I’ve been sleeping at a weird angle with my neck turned sideways in a different direction to the rest of me.

I turn my neck – that’s better, that’s comfy. My eyes close again and I give a warm welcome to the wondrous feeling of sleep without giving any more thought to where I am or why, or the drip that’s happily filling me with some kind of liquid.

Funny how sleep can do that.

The next time I wake up there’s a doctor staring down at me; a smiling Asian fella, who’s close enough for me to taste the cheese-and-onion butty he’s had from the canteen. Behind him are two nurses; one of them is looking at a clipboard and nodding at something the doctor is saying, the other one is smiling at me like I’m some kind of half-wit.

‘Ah, hello, Mr Parks,’ says the doctor. ‘Nice to have you back in the land of the living. How are you feeling?’

‘I’m fine,’ I say, and instantly try to get up on my elbow. One of the nurses intervenes, plumping up my pillow and easing me slightly forward – she’s got nice breath; she must have had the salad.

‘I am Dr Aranthraman,’ says the doctor. ‘They tell me that you are a famous footballer?’

I am. I am Billy Parks.

He doesn’t wait for any response, instead he starts to say things to me in a doctor-type of way, talking quickly in heavily accented English. I can’t understand him. What’s he going on about? He tells me something about some tests. Then something about my liver and only 15% of it working or perhaps he said 50%, I’m not sure. But they were going to clean it or something by giving me some medication.

And how often do I drink?

‘Now and again,’ I say, then I try to smile at one of the nurses. ‘The crowd expects it,’ I add. But the nurse doesn’t appear to understand.

Dr Aranthraman gives me a lecture about not drinking. I’ve heard it before.

‘Your liver is in a bad way,’ he tells me, ‘just one more drink could kill you.’ Then he tells me that he’s placed me on the waiting list for a transplant, but I won’t have one if I continue to drink alcohol. As he speaks I start to feel very tired: perhaps it’s his halitosis?

‘Do you have any questions?’ he asks me.

‘Has anyone been in to see me?’ I ask. The doctor’s lips thin and I see a nurse shake her head.

When I wake up the third time, I am startled by the sight of Gerry Higgs sitting quietly in the corner seat of my room. What’s he doing here? I stare at him. He appears to be asleep, his hat on his knee and his head bowed. What the fuck is he doing in my room?

I remember now, his question, and the park, and what was it he told me he was part of? The Institute or something, no, not the Institute, what was it? The Service. Yes that’s right, the Service.

As I look at him, one of his manic eyes jerks open and stares at me, before the other one joins it. He smiles, like he’s played a really good joke.

‘Mr Higgs,’ I say. ‘I didn’t expect you to be here.’

‘All part of my work,’ he says, then quickly changes the subject before I can ask him what in the name of God he’s going on about. ‘So, what have the doctors said then?’ he asks.

I shrug. ‘Oh it’s nothing, something about me liver not being too good,’ I say and I mutter something about a transplant, which gets me thinking that surely I should have some say about whether I actually want a transplant: I mean they just can’t haul out bits of you. Can they?

‘You don’t want to worry too much about what these doctors say, Billy,’ says Gerry Higgs, ‘half the time they’re more interested in their statistics: it looks good if they perform so-many operations and procedures and transplants.’

He’s probably right.

‘You see, Billy,’ says Gerry Higgs, who’s now pulled his chair closer to my bed, ‘I need you fit and well.’

What? I find myself smirking at the incredulity of this. ‘Why’s that, Mr Higgs, does that Russian bloke want to sign me for Chelsea?’

I watch Gerry Higgs’s face crease up scornfully as I mention Roman Whatshisname from Chelsea. ‘Don’t talk to me about that gangster,’ he says. ‘No, Billy, I’m talking about proper footballing men, geniuses.’

Now, for the first time, it crosses my mind that Gerry Higgs might actually be a few players short of a full team.

‘Gerry,’ I say. ‘Mr Higgs, I’ve no idea what you’re talking about.’

He leans in towards me, his face close to mine. I can see the hairs that explode from his veined nostrils and the blood pumping to the pupils in his eyes.

‘The Council of Football Immortals, Billy,’ he whispers, giving each of the words the heavy weighty air of importance.

‘Who?’

‘The Council of Football Immortals,’ he repeats putting his face even closer to mine. ‘The greatest footballing minds that ever lived.’

His lips wobbled as he spoke and spit flew out indiscriminately. He is definitely mad, and if it is his intention to scare me, then he has succeeded, because I’m shitting myself. I consider pushing the red ‘help’ button by the side of the bed.

‘That’s why I asked you the question I did, Billy,’ he says, and he asks it again, though this time in a rather sinister rasping whisper. ‘What would you give to have the chance to turn the clock back and put a few things right?’

No words come to me, instead I move myself as far away from him as I can. Our eyes meet and we stare at each other. Then he breaks off and turns his face away from me.

‘That’s why I asked about your daughter, Billy. You see I know that you and her have,’ he paused now, searching for the right words, ‘got a few issues to settle.’

My daughter. He’s right. My little girl. As soon as he says it, the image of her and her boy, my grandson, Liam, forms in my mind. He’s right. But I don’t want him to be right. I want to tell him that he’s talking bollocks and that everything between us is tickety-fucking-boo, but before I can say a word in response, he’s waving his craggy finger at me: ‘Don’t worry about it, Billy, I understand, old son, it’s not just your fault. But we can help you to sort it all out.’

‘We?’

‘The Service.’

Oh, Christ, there it is again, that word ‘Service’. Just the mention of it makes me swoon and slip down my pillows. He watches me, and I wonder what he’s going to do next. To my surprise, he taps me gently on the hand.

‘I’ll tell you what,’ he says, still tapping, ‘I’ll leave you now to get some rest; the Council haven’t formally called you up yet, so we’ve got a few days, but I’ll be in touch when I know a bit more. Who knows, they might let you sit in on one of their sessions before you go before them.’

With that he stood up and was gone.

4 (#udf1a4d3f-a94d-5ad4-bdfe-1a7d25e3c762)

Billy Parks’s mum, smells of bubble-gum, Billy Parks’s mum, smells of bubble-gum.

The three bastards had been keeping their chant up all the way home. Bastards: Eddie Haydon, grinning and gurning like a melon; Pete Langton, shouting at the top of his newly developed, but still squeaky voice; and Larry McNeil, the biggest bastard of the lot, defying me to turn around and confront them so that they could give me a right good pasting.

I’d been in secondary school for a week: St Agnes School for ruffians, rogues and arseholes. Each day, for some reason, these three had decided to follow me home goading me with their chant. I knew that their words had nothing to do with bubble-gum; this was their assertion that my mother had cavorted with a Yank during the war: it was a suggestion that I was the illegitimate child of an American soldier. A suggestion made solely on the basis that I didn’t have a dad. The morons – I mean I wasn’t even a war baby, I was born in 1948, three years after the Yanks had either gone home or been blown to high heaven in Normandy. Historical detail, though, meant nothing to Larry McNeil and his cronies. I was small, with no dad and that made me an easy target.

‘Hey, Parksy,’ one of them shouted, ‘was your dad Frank Sinatra?’ They laughed as though this is the funniest thing any of them have ever heard. ‘Or was he John Wayne?’ said another joining in a thread of mindless abuse that could have gone on for some time had they actually known the names of any more Americans. ‘Perhaps he was a nigger,’ said one of them. I turned to confront them, my teeth clasped together and my fists tight like rocks by my side. Straight away their laughing stopped and they hardened their own stance. ‘Come on then, Billy,’ said McNeil. ‘Come on if you’re going to fight us.’

I was outnumbered. I was not a fighter. I wanted to protect the honour of my unhappy mother and poor bastard father who went to Burma to mend tanks for these little arseholes and who ended up in the canal – but I couldn’t. I turned away from them and they jeered and howled and made chicken noises and continued with their chant about my mother smelling like bloody bubble-gum.

I got home and closed the door behind me; the still silence of our house put its arm around me like an old mate, I was safe. I put my foot on the stairs with the intention of going up to my bedroom, but my mother’s voice stopped me: ‘Billy, is that you?’

‘Yes, Mum,’ I said. I didn’t want to talk to her. I didn’t want to see her. I knew that she’d be sitting in the front room, perched on the edge of the armchair. Fidgeting. Nervous. I knew that. What I didn’t know though is how she would be with me. I didn’t know if I was going to be the waste of space and accident that she wished had never happened, or her lovely son, her little sunshine, the light of her otherwise dark bloody life.

‘Billy,’ she said again. ‘Yes, Mum,’ I answered and wandered into the front room.

There was no trace of her drinking, not a clue, there never was then. She’d stopped going to Mrs Ingle’s years earlier. I didn’t link her mood swings with drink. It would be a debate I would avoid having all my life.

‘Come and sit down,’ she said, ‘have a chat with your old mum.’ She looked pathetic, holding one shaking hand in the other; did I nearly lose my temper for this? Did I nearly get my arse kicked in a fight to protect this? Nearly.

‘How’s school going?’ she asked.

And I shrugged. ‘Alright,’ I said unhelpfully and she looked at me as though she was trying to gauge if I was telling her the truth.

‘Good,’ she said and I looked down, knowing that she was staring at me, hoping that I’d say something that would make everything somehow better, even for a second, but I couldn’t. I bloody couldn’t.

After an age, she continued. ‘Listen,’ she said, ‘I tell you what, why don’t we go to the pictures on Friday, The Alamo is showing down the Roxy, my treat.’ She smiled doubtfully at me, and I hated her weakness but I hated myself even more, because deep down I knew it wasn’t her fault.

‘It’s got John Wayne in it,’ she continued, ‘you like him’, and I grimaced at the ironic mention of John Wayne. ‘Well?’ she said, and I nodded and her face broke out into a smile. ‘Good, that’s a date then.’

I knew that by Friday, she’d have forgotten.

‘Come and give your old mum a hug.’

I tentatively got up and slowly walked towards her, my body hardening against the thought of hugging her. And she knew it, and it just made everything bloody worse.

I went outside to the back yard and kicked my football against the target I had drawn on the gate. I kicked it alternately with my right then left foot, 200 times, it had to be 200 times and if I missed the target just once, I had to go back and start again. I kept missing because I was angry.

The next day Larry McNeil and his mates were waiting for me again. This time we were in the changing room before PE. It was my first PE lesson at St Agnes. Pete Langton spotted me: ‘Hey look fellas, here he is, the Yankee Doodle Dandy.’ McNeil joined him and scowled at me as the changing room went quiet. ‘Billy Parks’s mum had it off with a nigger,’ he declared and I had no choice, I rose up and went for him – immediately the whole year of boys closed around us chanting, ‘fight, fight, fight,’ as they did. I put my head down and swung a few hopeful punches in McNeil’s direction, but, as I said, I was no fighter.

Mercifully, the fight was broken up by the muscular grasp of the teacher, Taffy Watkins. He pulled us apart and stared at us. ‘Right,’ he bellowed, ‘what on earth is all this about, I’ve never seen such a woeful fight in all my life: like two squirrels squabbling in a hessian sack.’

It was the first time I’d heard a Welsh accent. ‘Well?’ he repeated, but neither of us responded. ‘Right,’ he said, ‘you two shall come to me after the lesson and I will cane your rotten backsides.’

Then he turned to the rest of the class. ‘Now,’ he said, ‘on to the pitch so that I can laugh at your desperate attempts to play Association Football. The only thing of any worth invented by the English.’

At the mention of football, I felt my insides warm.

Outside on the school pitch, we were put into two teams. To my delight, Larry McNeil and his two mates, Langton and Haydon, were put on the opposing side to me. I knew what was about to happen. The gods of football had meant for this.

I got the ball pretty much from the kick off and set off down the pitch. I knew what I was going to do without even thinking. I could see the space on the pitch, I could feel the desperate lunges by the opposing team as they tried to take the ball from me. I was in complete control, my body responded instinctively – one boy, two boys, three boys, they couldn’t get near the ball as I feinted and shimmied and burst past them. Eventually there was only one player left between me and the penalty area, Larry McNeil. His face contorted with pathetic rage as he rushed towards me; silly arse, never play the man, always play the ball. He tried to kick me and I prodded the ball with my left foot past him and skipped over his trailing leg. Then, as Little Jimmy Cleary, a lad with callipers, who’d been put in goal, stood rooted to the spot, I put the ball in the back of the net.

On the touchline Taffy Watkins watched with his hands on his hips and the flicker of a smile across his chops.

I repeated the exercise seven more times and each time I made a total cunt out of Larry McNeil: this was for my unhappy mother and my unhappy tragic father and for me, Billy Parks, growing a little bit happier with every goal.

At the end, I traipsed off with the rest of the boys. I knew that in the oh-so-important pecking order of eleven-year-old lads, I had risen like a meteor – I knew it, and so did Larry McNeil.

Taffy Watkins held us back. We sat outside the room off the gym reserved for PE teachers; Watkins’s own personal fiefdom where he would reward and nurture the few boys he felt possessed sporting talent, and brutalise the rest. Larry didn’t look at me. He was called into Watkins’s room first and I heard the thwack of the cane as he delivered six of his Welsh best on to Larry McNeil’s arse. McNeil ignored me as he emerged, red faced and gritting his teeth against the tears he knew he couldn’t show.

I braced myself.

‘Right,’ said Watkins and I followed his beckoning finger into the tiny room. It smelled of liniment, dubbin, old leather, dry mud and scared boys. He looked at me: ‘The other lad started it did he?’ I said nothing. ‘I thought so,’ said Watkins, ‘now I’m going to give you one chance – you’re to train with the under-fifteens this Thursday, and if your performance out there was a fluke and you’re rubbish, you shall have ten of what McNeil had – you hear me?’

‘Yes, Sir.’

‘Good.’

‘Right, off you go.’

‘Thank you, Sir.’

He nodded as I got up to leave.

‘Oh, and what is your name again?’

‘I am Billy Parks, Sir.’

Details: Match 2, September 1960

Venue: St Agnes Third XI football pitch (knocked down and redeveloped into a Sainsbury’s in 1991)

Class 1e 10 v. Class 1f 1

Parks (8) Eccles (2)

Gillway

Line Ups (formations a bit fluid)

Class 1e: Charlie Hugheson, Tommy Rigby, Alan Hattersley, Brian Collins, Peter Hirst, Johnny Smith, Paul ‘Donkey’ Edwards, Ed ‘Clarkey’ Clarke, Billy Hindles, George Gillway, Billy Parks

Class 1f: Little Jimmy ‘Four Legs’ Cleary, Unknown boy, described as having a cleft palate, Larry McNeil, Sam Smith, Paul Carrington, Pete Langton, Eddie Haydon, Maurice ‘Spud’ Eccles, Keith Ringer, Richard ‘Paddy’ Murphy, Dave ‘Shorty’ Hopkinson

Attendance: 1 (Taffy Watkins)

5 (#udf1a4d3f-a94d-5ad4-bdfe-1a7d25e3c762)

I know it’s there. I know it is sitting on the table in my kitchen, at least half-full. It has been growing in my mind over the last few days as I have waited for my release from hospital and is now the size of one of those giant bottles that you see on advertising hoardings: a giant bottle of vodka.

‘No more drinking now,’ Dr Aranthraman says, ‘remember, just one more drink could kill you,’ and he smiles, because he’s a nice fella, and I smile, because I am the twinkling, dazzling Billy Parks. And then Maureen, who has come to pick me up and take me home, bless her, smiles, but she does so with thin lips, because she knows the weakness in me.

‘You look after him now,’ says Dr Aranthraman, ‘he is a famous footballer.’

‘Oh I’ll do my best,’ she says, looking at me like I am a naughty boy. I smile up at them both, but in my mind, I am being chased by a six-foot bottle of fucking Smirnoff vodka. I know that it is there, on my kitchen table. It is there and it has grown and now fills all the space in my brain with its wondrous evil presence.

We get into Maureen’s car. As ever she is immaculately turned out; all teeth and hairdo and posh knickers, that’s Maureen. I catch a glimpse of stockinged thigh as she changes gear. I know that underneath her clothes there will be a complicated and exotic system of underwear that is designed to deflect attention from the signs of wear and tear on her fifty-five-year-old body. It works too. Usually. But not today. After two weeks in hospital, even I, Billy Parks, can’t think about getting me leg over. All I can think about is the vodka bottle on the kitchen table.

‘So,’ she says, ‘how are you feeling?’

‘I feel fantastic,’ I say, ‘like I’ve got a new zest for life.’ The words float easily from my mouth, they’re not weighed down by truth.

‘That’s great. I kept a couple of clippings from the newspapers for you.’

She’s good like that, Maureen, she’s been doing it for the entire time we’ve known each other; she’s already told me that there was a paragraph in the Sunday People, saying ‘Former West Ham favourite, Billy Parks collapsed while out watching a park game’, which is a load of cobblers, I was on my way to the pub; while the Mirror ran a story about ‘Billy’s Booze Battle’. I don’t mind. They’ve got their job to do. They’ve got to sell their newspapers. And, for me, I can’t lie: it’s nice to be talked about.

We drive down round the Elephant and Castle and I look out of the window at the light of the day. After ten days in the hospital, the world seems huge, a bloody frightening, fast moving chaos; the cars are giant metal beasts, careering around corners and across junctions, carrying life and normal, ordinary people. And as I watch them the vodka bottle grows bigger and more powerful.

I try to take my mind off it. I’ve got to. Dr Aranthraman told me: booze, no new liver, bad end; no booze, new liver, life. It sounds easy.

I try to chase the vodka bottle away by changing the subject.

‘Funny thing happened,’ I say, ‘in hospital, a very funny thing; this old geezer, Gerry Higgs his name is, he used to be like a coach and groundsman at the Orient when I was a kid.’

She pouts and her eyes narrow a bit as she’s taking in what I’m telling her. ‘He was there when I fell over in Southwark Park and he comes to visit me.’ I stop, because it still doesn’t make any sense to me. ‘He must be well into his eighties, because he was old back in the day.’ I pause and the image of Gerry Higgs back in 1965 shouting and bawling at the apprentices drifts into my mind. ‘Well anyway, he tells me that I’ve been selected to appear before some kind of committee of footballing legends.’

‘Footballing legends?’ she says. ‘What’s that?’

I shrug, then sigh, ‘I dunno.’ Because I don’t know, I have no clue what Gerry Higgs meant. ‘Perhaps it’s some programme on ESPN or Sky Sports or summat, anyway, it was nice of him to visit me.’

Maureen turns to me now. ‘Visit you?’ she says. ‘Those nurses told me that the only person to visit was me.’

‘No,’ I say. ‘Gerry Higgs was definitely there.’

She drives on. She’s not interested in the Council of Football Immortals. Instead she tells me that in the back of the car she’s got something for me: a jigsaw. A jigsaw. I’m confused. A jigsaw? Me, Billy bloody Parks. I once scored a hat-trick inside twenty minutes at Maine Road, pulled Mickey Doyle all over the place I did – God love him.

What do I want a jigsaw for?

‘It’s a competition I’m running at the pub,’ she tells me. ‘There’s a prize for the person who can complete the jigsaw in the quickest time. You text me when you’re about to start and then text me when you’ve finished, and I put the times up in the bar. Little Brian Staplehurst, you know that bloke who works at Lloyds Bank, he’s already posted a time of seventeen hours. And anyway – it’ll keep your mind off drinking and going to the pub – you heard what the doctor said.’

The vodka bottle grows a little bit more and casts me in its magnificent, vicious shadow.

‘Seventeen hours,’ I say. ‘Is he blind or something?’

‘No.’

She laughs.

She has a nice laugh does Maureen, that’s what I first liked about her; she has a light laugh, flirty, but not quite accessible, yes, that is Maureen. It’s why we’re not an item, never have been, not properly – she’s a landlady with a nice laugh and great underwear who has been let down by better blokes than me and knows how to enjoy a bottle of wine and listen to all the bullshit and be seductive without allowing you to get too close. I’ve known her for years. I like her. If we’d met when we were younger, before the bad blokes, before everything, then, who knows?

We park up. And make our way up the stone piss-smelling staircase to my second floor flat.

It’s not there.

It’s not bloody there. The vodka bottle is missing from the kitchen table. It’s not bloody there. It’s not there and its absence has blasted a hole through my very being. How can it not be there? I don’t want to drink it, of course not, one more drink might kill me, but I want it to be there, more than anything. I want the chance to drink it.

I turn to Maureen. ‘The vodka bottle,’ I say, ‘the bottle that was on the table – where is it? Where the fuck is it, it was sitting on the table, half finished?’

She looks at me, her face crumbling with incredulity at what I am saying, and I know that’s the right reaction, but I just want the fucking massive bottle of vodka, the fucking beautiful massive bottle of vodka which has been chasing me and has caught me and dragged me closer to its open mouth.

‘Billy,’ she says. ‘Billy, are you mad? You can’t drink vodka, I chucked it down the sink when I came to get your clothes for you.’

‘You silly cow. You silly fucking bitch.’ The words just shoot out of my mouth. I’m not thinking; I’m like a cobra, a thirsty horrible black cobra crawling on my belly; I just want it to be there. Is it too much to ask? What has it got to do with her, what does she care if I have a quick vodka now I’ve been released from hospital? I mean, she’s just a friend; we haven’t fucked each other for months.

‘You silly, stupid bitch,’ I say, and I’ve gritted my teeth and I’m so, so wrong. And I’ve clenched my fists and for a second I am so angry that I want to punch her, but instead I slam my hand against the empty kitchen table.

Maureen puts her hand up, she’s dealt with much worse than me. ‘Billy,’ she says, ice cold, colder than the North Pole, colder than the surface of Neptune, she sighs, and shakes her head. ‘Just fuck off and kill yourself.’ And with that she’s gone, out the door.

I’m left alone. For about an hour I frantically go through the bins and the cupboards and drawers, looking for a drink. I throw things on the floor and rip out stuff from the back of my wardrobe. I search through boxes crammed with my life history, yellow newspaper clippings, old programmes, photos of me, young and beautiful with my arms around the shoulders of missing friends. I ignore them, I discard them in my search for drink. But there isn’t any. I know there isn’t any. I know that there is no drink in my home. But looking for it has at least made me feel alive.

Alive.

Then tired.

I sit down on my own. I sit down on my bed in my one-bedroom Housing Association flat, panting, and put my head in my hands. Me, Billy Parks, crying like a right twat. I could go out to get more drink. Replace the vodka. I could. I want to. But I can’t do it. Instead I lie on my bed and try to think about something meaningful. I try to picture my daughter and her son. I want to make plans to see them, take the boy somewhere, perhaps I could take him down West Ham, get in the Directors box, see the players, but I can’t make those plans, I can’t form the images in my head, images of happy me and happy daughter and happy boy. It’s too difficult. I can’t even work out how I’ll find her.

I get up and pace around. The dark clouds of self-loathing gather. Then I notice the jigsaw that Maureen’s left on the table, thousands of fucking pieces depicting a detail from the start of the London Marathon – thousands of heads and bodies in running vests with little numbers on them. I sigh. Seventeen hours she said. I sigh again but before I know it I’ve taken the pieces out and I’m turning them over the right way.

I have an idea.

I text Maureen telling her that I’m sorry and that I’m a complete twat, and that I’m starting the jigsaw. Then I telephone Tony Singh, a bookie I know from the pub. ‘Tony,’ I say, ‘Billy Parks here. I’m fine mate, never felt better. Listen, you heard about this jigsaw competition Maureen’s running at the pub? That bloke who works at Lloyds has posted seventeen hours. Yeah. Yeah. What odds you going to give me?’

Fucking four to one: the tight-fisted bastard.

Still – I have two hundred and fifty quid on Billy Parks.

6 (#udf1a4d3f-a94d-5ad4-bdfe-1a7d25e3c762)

Two days later I find Gerry Higgs waiting by the lift at the bottom of my building. He’s got a rather odd, pleased expression across his face. I’m wary, but, I have to admit, intrigued by the old duffer.

‘Hello, Billy,’ he says.

‘Mr Higgs,’ I say, ‘what brings you to these salubrious parts?’

His face breaks out into his most sinister smile. ‘You, of course, Billy,’ he says.

Of course.

‘It’s good news,’ he adds, ‘the Council of Football Immortals have said that you can watch one of their plenary sessions.’

‘Oh,’ I say, ‘that is good news.’ Though in reality I haven’t got the faintest idea what he’s talking about; what the fuck is a plenary session?

‘Actually, I was just off to the bookie’s,’ I tell him and he smiles at me again.

‘Plenty of time for that, old son,’ he says. ‘Come on.’

I follow him like a kitten, and we get into a cab on the High Street.

‘Where are we going?’ I ask him.

‘Lancaster Gate, of course,’ he says.

Of course.

I tell the cab driver. He doesn’t recognise me.

Lancaster Gate, once home of the Football Association. We get out of the cab and I follow Gerry Higgs around to the back of a massive Georgian town house; one of those ones that doesn’t look that big from the outside, but inside is like a fucking Tardis with ballrooms and banqueting suites and all that. We go through a black back door that leads to a well-lit corridor. On the wall are pictures of the greats: Steve Bloomer, the original football superstar, standing upright and handsome with his hair parted like the Dead Sea. Then Dixie Dean, rising to power in a header. Dixie, what a man, bless him, I met him once at a charity do at Goodison Park just before he died. He’d had his legs amputated, the poor bastard; I mean, how cruel is that, taking away the legs and feet of the man who once scored sixty goals in a single season? Then there’s Duncan Edwards, who died in Munich, running on to the pitch all muscle and power knowing that no fucker was going to get the better of him, and Frank Swift, back arched and diving to tip a volley over the crossbar, come to think of it he died in Munich as well, and others, all captured in their prime, beautiful men, athletes, captured before those most horrible devious rotters of all, time and fate, got each and every one of them. Bang, bang, bang, bang.

There are no pictures of me.

At the end of the corridor, Gerry Higgs turns and puts his finger to his lips. ‘Come on,’ he whispers, and he opens a door that leads to a small room with a window in it; through the window I can see another room in which sit a collection of men around three tables that are arranged in a U-shape: I look closer.

Fuck me.

I feel my whole body move towards the men, my eyes wide, bursting out of my skull. I turn to Gerry Higgs, mouth open in wide-eyed-child-like-cor-blimey astonishment.

‘Who are they?’ I ask. But I know.

‘You know who they are,’ says Gerry, grinning like a man who’s just given someone the best Christmas present they’ll ever have and knows it.

‘It can’t be,’ I say and Gerry Higgs just nods at me, the grin remaining on his slobbering lips.

I turn to look at the three tables again. At the top table sits Sir Alf Ramsey. Then at the table to his right is Sir Matt Busby and next to him Bill Shankly, and across from them, scowling at each other are Don Revie and Brian Clough.

‘That’s the Council of Football Immortals, Billy,’ says Gerry Higgs. ‘I told you, didn’t I – the greatest geniuses known to the game of football.’

‘But, Gerry,’ I say, ‘they’re all dead. I mean, I even went to Sir Alf’s funeral.’

Gerry Higgs looks at me like I’m a silly little boy. ‘Billy,’ he says, ‘Billy, Billy, Billy, these men aren’t dead. Men like this never die, they live on and on, way beyond the lifespan of mere mortals. That’s why they’re legends, old son. Proper legends. Not the five-minute wonders you get today.’

I stutter: ‘Gerry, I don’t understand.’ And Gerry Higgs looks at me: ‘Don’t worry,’ he says, ‘for now, just listen. You see, Billy, if you play your cards right, they’re going to make you immortal too.’

I try to listen. But I can’t hear them. I can see that Brian Clough is talking, he is animated and Brylcreemed in a green sports jacket; I see Sir Alf, just as I remember him, quiet and controlled, neat and tidy in his England blazer; I see Shanks in his red shirt and matching tie and Don Revie, looking glum with his thick shredded-wheat sideburns; and Sir Matt, blimey Sir Matt Busby, nonplussed and immaculate. I see them all, and I wonder what on earth is going on. Why are they here? Why am I here?

Gerry Higgs reads my mind. ‘Just listen, Billy,’ he whispers quietly but firmly. So I do. And now, suddenly I can hear them as well as see them. Cloughie is in full swing.

‘No, Don,’ he says in that piercing nasal voice, ‘the game of football is not simply about winning, it’s about winning properly, it’s about playing the game how it was supposed to be played. And kicking and cheating is not how the game is supposed to be played.’

Don Revie blusters a response: ‘Brian, I’m not rising to that, and the reason I’m not rising to that is two league titles, the FA Cup, a Cup Winners’ Cup, two Inter-Cities Fairs Cups and the League bloody Cup, that’s why.’

The other three groan. ‘Mr Revie,’ says Sir Alf, ‘Mr Clough. Please, this isn’t getting us any further. You both know the issue that we are here to discuss today.’

‘Well, we know exactly where you stand, Alf,’ says Brian Clough, curtly.

‘Thank you, Brian,’ says Sir Alf with a school teacher’s sarcasm before adding, ‘Sir Matt, I believe we haven’t heard from you on the question before us – what takes precedence: winning or entertaining, style or results.’

Sir Matt thinks for a second, his lips turning over. ‘Well,’ he says in his quiet, Glaswegian drawl, ‘no one ever remembers the losers do they? But if you can manage both to entertain and win, then you’re not far off.’

Shanks joins in, in his more abrasive Glaswegian drawl: ‘The question isn’t about winning or entertaining, I mean we’re not clowns or circus horses; it’s about making the working man who pays his money on a Saturday afternoon happy and proud, so that when he goes back to the factory or the shop floor on the Monday, he feels valuable, vindicated.’

‘Aye,’ says Sir Matt, ‘but in that pursuit we can’t allow football to lose its charm can we?’

I turn to Gerry Higgs. ‘What are they talking about?’ I say. But what I really want to know is what it all has to do with me.

‘They’re asking themselves the fundamental question, Billy,’ says Gerry Higgs. ‘Why are we here? Who should we aspire to be? The poor bastard who lives his life according to the rules, makes sure he gets by, pays his taxes, works nine to five and remembers everyone’s birthdays, or should we aim to be a little bit different to that, live according to our aspirations in one great big nihilistic fantasy? Because after all, we’re not here for very long are we?’

‘Well,’ I say nervously, ‘I suppose we all want to be a bit different, don’t we?’

‘Yes, Billy, old son.’ And he looks at me, and I know that he’s wondering how much of this I understand.

He looks back at the Council of Football Immortals.

‘It sounds so easy when you hear Mr Clough talk, doesn’t it?’ he continues, ‘but sometimes if you’re a bit different, a bit cavalier, you end up hurting the people who love you most. Isn’t that right?’