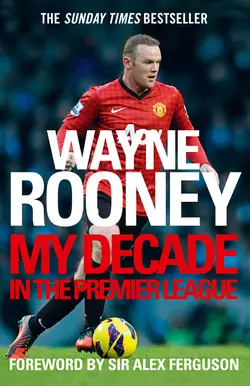

Wayne Rooney: My Decade in the Premier League

Wayne Rooney: My Decade in the Premier League

Wayne Rooney

‘My Decade in the Premier League’ is Wayne’s first hand account of his 10 years playing at the highest level in English football – and for the biggest club in the world. This is his inside story of life on the pitch for Manchester Utd; the League titles, FA Cups, League Cups and Champions League adventures. A must for any Utd fan.

Wayne Rooney is widely regarded as one of the leading football players of his generation. A talisman for Manchester United, since his transfer to them in 2004, Rooney is their star player and the first name on the team sheet.

In the 10 years since he made his debut as a 16 year old for Everton, he has acquired trophy after trophy, accolade after accolade and headline after headline.

‘My Decade in the Premier League’ is the inside account of life as a Premier League footballer from the man every one wants to hear from. This is his story, in his words. From gracing the ground at Goodison as an excitable 16 year old to lifting the Champions League trophy with Manchester United. From the emotional high of scoring the winner against Manchester City with that overhead bicycle kick to the crushing low of the thrashing City handed out at Old Trafford in the 2011-12 season.

This is a book for the fan who would kill to get just 30 seconds on the pitch at The Theatre of Dreams – to run on the famous turf and score in front of the Stretford End. ‘My Decade in the Premier League’ gives a real insight in to what goes in to being part of the biggest club in the world; the training pitch, the dressing room, the manager, the coaches and, most importantly, the buzz of crossing that white line and hearing the 76,000 strong crowd chant your name.

In intricate, emotional detail Wayne talks about every season he has spent in the Premier League and how it feels to be one the most celebrated footballers on the planet.

COVER (#uadca0b6f-42b7-5d9b-b9d9-ca4ebf96fad1)

TITLE PAGE (#ufa80a96a-d026-5b62-8b1f-e1ad6916495a)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

FOREWORD BY SIR ALEX FERGUSON

INTRODUCTION

1 DESIRE

2 HOME

3 CARRINGTON

4 PAYBACK

5 GRAFT

6 PRESSURE

7 CHANGE

8 CHAMPIONS

9 EUROPE

10 SACRIFICE

11 MOSCOW

12 DEBUT

13 MANCHESTER

14 RIVALS

15 FACT!

16 NIGHTMARE

17 PASSION

18 PAIN

19 CONTROVERSY

20 FAMILY

21 OFFICE

22 MARGINS

EPILOGUE

PLATE SECTION

ABOUT WAYNE ROONEY

ABOUT MATT ALLEN

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#u5df184fc-98ff-5601-afea-67b8522b24ad)

There are so many people who have helped and worked alongside me to make my Premier League dream become a reality. First and foremost my parents and family have played a massive role in getting me where I am today.

All the coaches and managers I have worked with since being a young lad, my agent Paul Stretford and the people who work alongside him, and all my team mates and friends in and out of the game: thanks for being there. But through working on this book and reflecting on the highs and lows of the last 10 years there are two people who merit specific mention.

To my wife Coleen, thanks for being there through the rough and the smooth; you will never know how much your love and support means to me. To my son Kai, you’re my first thought in the morning and you give me my last smile at the end of the day. I love you both so much, you’re my inspiration and my motivation every single day.

Thanks for everything.

Love,

Wayne (and Daddy) xxx

(#u5df184fc-98ff-5601-afea-67b8522b24ad)

There were plenty of eyebrows raised when I persuaded Manchester United’s board of directors to sanction a multimillion pound move to try to prise away Wayne Rooney from Everton.

The lad was still only eighteen, but he had already shown in the two years he’d been in Everton’s first team that he was a rare talent.

The Everton backroom staff had done a marvellous job nurturing the youngster through their academy to the day he made his debut for the first team when still some weeks short of his seventeenth birthday.

Long before he made his bow for the senior side everybody in the game was well aware that Everton had unearthed a little gem, and it didn’t take him long to announce his arrival on the big stage.

Everton were Wayne’s club as a schoolboy, so we can only imagine how he felt to pull on that famous royal blue shirt and run out to the roar of the Goodison Park crowd.

It wasn’t a surprise that he took to first team football with the minimum of fuss. Wayne Rooney was born to play football and it was plain to see from the outset that his future as a major figure in the game was assured.

We were under no illusions that it would take anything other than a very, very large cheque if we were to tempt Everton into agreeing to let Wayne make the short move up the M62.

I suppose everyone has their price and eventually we managed to negotiate a deal with Everton to secure the services of the finest young player of his generation.

There’s no question that it was a gigantic amount of money we paid for a player who hadn’t long been eligible to vote, but we knew what we were doing.

Every so often a player comes along who is a racing certainty to make the grade as a professional, and Wayne Rooney was one of those.

It wasn’t a gamble, it was an investment in the future, and there can be no doubt that the lad from Croxteth proceeded to pay off that outlay numerous times in the years that followed.

If anyone had any lingering doubts regarding our decision then they were almost instantly and conclusively dispelled when he scored a hat-trick on his debut in a Champions League group match against Turkish club Fenerbahçe at Old Trafford. Talk about starting the repayments early!

It wouldn’t have bothered me if he’d taken weeks to score his first goal for us, but I’ve got to say I was overjoyed that he hit the ground running in classic style.

The rivalry between Manchester and Liverpool has been well documented over the years, but here was one Scouser who had immediately become an adopted Mancunian.

That was just the first few lines in a marvellous story that has continued to unfold during his career with Manchester United. He has become one of the mainstays of the club and is generally recognised as one of the finest players of the Premier League and Champions League era.

Wayne has also along the way ironed out the self-discipline problems he had as a youngster. Once looked upon as petulant and always likely to get in hot water with the authorities, he is now a reformed individual who sets the standards for the rest of the team.

It takes strength of character to overcome those types of personal traits, but he dug deep and eradicated what was a counter-productive part of his make-up.

Then there was his little wobble in the autumn of 2010, when he announced that he wanted to up sticks and leave Old Trafford.

I was shocked, and not a little disappointed, but it didn’t take long to set him straight on that little matter and soon enough he was putting pen to paper on an extended contract.

I’m not about to say what was said between us during our discussions at that time, but I knew from the start that his heart was still with Manchester United and that all wasn’t lost as we set about showing him the error of his thinking. Wayne Rooney has it within his grasp to carve for himself a very special place in the history of Manchester United.

He has already started overtaking long-standing club records, and with age on his side there are no limits to what he can achieve before the time comes for him to call it a day.

I’d like to think I’ve made one or two good decisions during my time in football – and a few I’d rather forget! – but there is no question that the signing of Wayne Rooney from Everton is right up there with the best of them.

(#u5df184fc-98ff-5601-afea-67b8522b24ad)

Bang!

Everything goes dead mad, dead quick.

Then that feeling kicks in – an unbelievable feeling of satisfaction that I get from scoring a goal in the Premier League. Like the sensation I get whenever I’ve smashed a golf ball flush off the face of the club and watched it trickle onto the green.

It’s a high – a mad rush of power.

It’s a wave of emotion – but it takes me over like nothing else.

This feeling of putting one away for Manchester United is huge, selfish, nuts. I reckon if I could bottle the buzz, I’d be able to make the best energy drink ever.

A heartbeat later and I’m at normal speed again, I’m coming round.

Everything’s in focus: the sound, a roar loud enough to hurt my ears, like a plane taking off; the aching in my legs, the sweat running down my neck, the mud on my kit. There’s more and more noise; it’s so big, it’s right on top of me. Someone’s grabbing at my shirt, my heart’s banging out of my chest. The crowd are singing my name:

‘Rooney!’

‘Rooney!’

‘Rooooo-neeee!’

And there’s no better feeling in the world.

Then I look up and see the scoreboard.

12 FEBRUARY 2011

United 2 City 1

GOAL!

Rooney, 77 minutes

Who I am and what I’ve done comes back to me in a rush, a hit, like a boxer coming round after a sniff of smelling salts. I’m Wayne Rooney. I’ve played Premier League football since 2002 and I’ve just scored the winning goal in a Manchester derby – probably the most important game of the season to fans from the red half of town. A goal that puts our noisy neighbours, the other lot, in their place. A goal that reminds them that United have more history and more success than they do right now. A goal that warns the rest of the country that we’re on our way to winning another Premier League title.

The best goal of my career.

As I stand with my arms spread wide, head back, I can feel the hate coming from the City fans in the stand behind me, it’s like static electricity. The abuse, the screaming and swearing, is bouncing off me. They’re sticking their fingers up at me, red-faced. They’ve all got a cob on, but I don’t give a toss. I know how much they hate me, how angry they are; I can understand where they’re coming from though, because I go through the same emotions whenever I lose at anything.

This time, they’re wound up and I’m not.

I know it doesn’t get any better than this.

I’ve bagged hundreds of goals during my time in the Premier League with United and Everton; goals in league games, cup games, cup finals, meaningless friendlies, practice games in training. But this one is extra special. As I jog back to the centre circle, still tingling, I go into rewind. It’s ridiculous, I know, but I’m worried I might never feel this way again. I want to remember what’s just happened, to relive the moment over and over because it feels so good.

We were under pressure, I know that, the game level at 1–1, really tight. In the seconds before the goal, I try to lay a return pass back to my strike partner, Dimitar Berbatov – a ringer for Andy Garcia in The Godfather Part III; dangerous like Andy Garcia in The Godfather Part III – but my touch is heavy. I overhit it. My heart jumps into my mouth.

City can break from here.

Luckily, Paul Scholes – ginger lad, low centre of gravity, the fella we call SatNav because his passes seem almost computer controlled, probably the best midfielder ever to play in the Premier League – scoops up the loose ball and plays it out to our winger, Nani, on the edge of the box. He takes a couple of touches, guiding the ball with his toes, gliding over the grass more like a dancer off Strictly Come Dancing than a footy player, and curls a pass over the top of the City defence towards me, his cross deflecting off a defender, taking some speed off it.

I see a space opening up in the penalty area. City’s two man-mountain centre-halves, Joleon Lescott and Vincent Kompany, move and get ready for the incoming pass. I run into a few yards of space, guessing where the ball will land. My senses are all over the place.

It’s hard to explain to someone who’s never played the game or felt the pressure of performing in front of a big crowd before, but playing football at Old Trafford is like running around in a bubble. It’s really intense, claustrophobic.

I can smell the grass, I can hear the crowd, but I can’t make out what’s being sung. Everything’s muffled, like when I’m underwater in the swimming baths: I can hear the shouting and splashing from everyone around me in the pool, but nothing’s clear, I can’t pick out any one voice. I can’t really hear what people are yelling.

It’s the same on the pitch. I can hear certain sounds when the game slows down for a moment or two, like when I’m taking a corner or free-kick and there’s a strange rumble of 20,000 spring-loaded seats thwacking back in a section of the ground behind me as I stand over the ball, everyone on their feet, craning their necks to watch. But it’s never long before the muffled noise comes over again. Then I’m back underwater. Back in the bubble.

The ball’s coming my way.

The deflection has changed the shape of Nani’s pass, sending it higher than I thought, which buys me an extra second to shift into position and re-adjust my balance, to think: I’m having a go at this. My legs are knackered, but I use all the strength I have to spring from the back of my heels, swinging my right leg over my left shoulder in mid-air to bang the cross with an overhead kick, an acrobatic volley. It’s an all or nothing hit that I know will make me look really stupid if I spoon it.

But I don’t.

I make good contact with the ball and it fires into the top corner; I feel it, but I don’t see it. As I twist in mid-air, trying to follow the flight of my shot, I can’t see where the ball has gone, but the sudden roar of noise tells me I’ve scored. I roll over and see Joe Hart, City’s goalkeeper, rooted to the spot, his arms spread wide in disbelief, the ball bobbling and spinning in the net behind him.

If playing football is like being underwater, then scoring a goal feels like coming up for air.

I can see and hear it all, clear as anything. Faces in the crowd, thousands and thousands of them shouting and smiling, climbing over one another. Grown men jumping up and down like little kids. Children screaming with proper passion, flags waving. Every image is razor sharp. I see the colour of the stewards’ bibs in the stands. I can see banners hanging from the Stretford End: ‘For Every Manc A Religion’; ‘One Love’. It’s like going from black and white to colour; standard to high-definition telly at a push of the remote.

Everyone is going mental in the crowd; they think the game is just about won.

From nearly giving the ball away to smashing a winning goal into the top corner: it’s scary how fine the margins are in top-flight footy. The difference between winning and losing is on a knife edge a lot of the time. That’s why it’s the best game in the world.

*****

We close out the game 2–1. Everyone gathers round me in the dressing room afterwards, they want to talk about the goal. But I’m wrecked, done in, I’ve got nothing left; it’s all out there on the pitch, along with that overhead kick. The room is buzzing; Rio Ferdinand is buzzing.

‘Wow,’ he says.

Patrice Evra, our full-back, calls it ‘beautiful’.

Then The Manager comes into the dressing room, his big black coat on; he looks made up, excited. The man who has shouted, screamed and yelled from the Old Trafford touchlines for over a quarter of a century; the man who has managed and inspired some of the greatest players in Premier League history. The man who signed me for the biggest club in the world. The most successful club boss in the modern game.

He walks round to all of us and shakes our hands like he does after every win. It’s been like this since the day I signed for United. Thankfully I’ve had a lot of handshakes.

He lets on to me. ‘That was magnificent, Wayne, that was great.’

I nod; I’m too tired to speak, but I wouldn’t say anything if I could.

Don’t get me wrong, there’s nothing better than The Manager saying well done – but I don’t need it. I know when I’ve played well and when I’ve played badly. I don’t think, If The Manager says I’ve played well, I’ve played well. I know in my heart whether I have or I haven’t.

Then he makes out that it’s the best goal he’s ever seen at Old Trafford. He should know, he’s been around the club long enough and seen plenty of great goalscorers come and go during his time.

The Manager is in charge of everything and he controls the players at Manchester United emotionally and physically. Before the game he reads out the teamsheet and I sometimes get that same weird, nervous feeling I used to get whenever the coach of the school team pinned the starting XI to the noticeboard. During a match, if we’re a goal down but playing well, he tells us to keep going. He knows an equaliser is coming. He talks us into winning. Then again, I’ve known us to be winning by two or three goals at half-time and he’s gone nuts when we’ve sat down in the dressing room.

We’re winning. What’s up with him?

Then I cotton on.

He doesn’t want us to be complacent.

Like most managers he appreciates good football, but he appreciates winners more. His desire to win is greater than in anyone I’ve ever known, and it rubs off on all of us.

The funny thing is, I think we’re quite similar. We both have a massive determination to succeed and that has a lot to do with our upbringing – as kids we were told that if we wanted to do well we’d have to fight for it and graft. That’s the way I was brought up; I think it was the way he was brought up, too. And when we win something, like a Premier League title or the Champions League trophy, we’re stubborn enough to hang onto that success. That’s why we work so hard, so we can be the best for as long as possible.

Everyone begins to push and shove around a small telly in the corner of the room. It’s been sitting there for years and the coaches always turn it on to replay the game whenever there’s been a controversial incident or maybe a penalty shout that hasn’t been given – and there’s been a few of those, as The Manager will probably tell anyone who wants to listen. This time, I want to see my goal. Everyone does.

One of the coaches grabs the controls and forwards the action to the 77th minute.

I see my heavy touch, Scholesy’s pass to Nani.

I see his cross.

Then I watch, like it’s a weird out of body experience, as I throw myself up in the air and thump the ball into the back of the net. It doesn’t seem real.

I reckon all footballers go to bed and dream about scoring great goals: dribbling the ball around six players and popping it over the goalkeeper, or smashing one in from 25 yards. Scoring from a bicycle kick is one I’ve always fantasised about.

I’ve just scored a dream goal in a Manchester derby.

‘Wow,’ says Rio, for the second time, shaking his head.

I know what he means. I sit in the dressing room, still sweating, trying to live in the moment for as long as I can because these moments are so rare. I can still hear the United fans singing outside, giving it to the City lot, and I wonder if I’ll ever score a goal as good as that again.

*****

I’ve played in the Premier League for 10 years now. I’m probably in the middle of my career, which feels weird. The time has flown by so quickly. It does my head in a little, but I still reckon my best years are ahead of me, that there’s plenty more to come. It only seems like five minutes ago that I was making my debut for Everton against Tottenham in August 2002. The Spurs fans were tucked away in one end of Goodison Park. When I ran onto the pitch they started singing at me:

‘Who are ya?’

Whenever I touched the ball:

‘Who are ya?’

They don’t sing that at me anymore. They just boo and chuck abuse and slag me off instead. Funny that.

In the 10 years since my debut, I’ve done a hell of a lot. From 2002 to 2004 I played for Everton, the team I supported as a boy; I became the youngest player to represent England in 2003, before Arsenal’s Theo Walcott had that record off me. In 2004 I signed for Man United for a fee in excess of £25 million and became the club’s highest-ever Premier League goalscorer. During the European Championships that same year, the England players nicknamed me ‘Wazza’; the title seems to have stuck.

I’ve won four Premier League titles, a Champions League, two League Cups, three FA Community Shields and a FIFA Club World Cup. I’ve scored over 200 goals for club and country, and been sent off five times. I’d be lying if I told you that I haven’t loved every minute of it. Well, OK, maybe not the red cards and the suspensions, but everything else has been sound.

The funny thing is, the excitement and adrenaline I felt on the night before my league debut for Everton in 2002 still gets to me. The day before a game, home or away, always feels like Christmas Eve. When I go to bed I’ll wake up two or three times in the night and roll over to look at the alarm clock.

Gutted. It’s only two in the morning.

The buzz and the anticipation are there until the minute we kick off.

I’ve paid the price, though. Physically I’ve taken a bit of a battering over the years; being lumped by Transformer-sized centre-backs or having my muscles smashed by falls, shoulder barges and last-ditch tackles, day in, day out, has left me a bit bruised.

When I get up in the morning after a game, I struggle to walk for the first half an hour. I ache a bit. It wasn’t like that when I was a lad. I remember sometimes when I finished training or playing with Everton and United, I’d want to play some more. There was a small-sided pitch in my garden and I used to play in there with my mates. When I trained with Everton, I used to go for a game down the local leisure centre afterwards, or we used to play in the street in Croxteth, the area of Liverpool where I grew up with my mum, dad and younger brothers Graeme and John. There was a nursery facing my house. When it closed for the day, they’d bring some shutters down which made for a handy goal. I loved playing there. After I’d made my England debut in 2003 I was photographed kicking a ball against that nursery in a France shirt.

Footy has had a massive impact on my body because my game is based on speed and power. Intensity. As a striker I need to work hard all the time; I need to be sharp, which means my fitness has to be right to play well. If it isn’t, it shows. It would probably be different if I were a full-back; I could hide a bit, make fewer runs into the opposition’s half and get away with it. As a centre-forward for Manchester United, there’s no place to hide. I’ve got to work as hard as I can, otherwise The Manager will haul me off the pitch or drop me for the next game. There’s no room for failure or second best at this club.

If there is a downside to my life then it’s the pressure of living in the public eye. I’d like just for one day to have no-one know me at all, to do normal stuff; to be able to go to the shops and not have everyone stare and take pictures. Even just to be able to go for a night out with my mates and not have anyone point at me would be nice. On a weekend, some of my pals go to the betting shop before the matches start and put down a little bet – I’d love to be able to do that. But look, this is the small stuff, I’m grateful for everything that football has given me.

There is one small paranoia: like any player I’m fearful of getting a career-ending injury. I could be in the best form of my life and then one day a bad tackle might finish my time in the sport. It’s over then. But I think that’s the risk I take as a player in every match. I know football is such a short career that one day, at any age, the game could be snatched from me unexpectedly. But I want to decide when I leave football, not a physio, or an opponent’s boot.

Don’t get me wrong, the fear of injury or failure has never got into my head when I’ve been playing. I’ve never frozen on the football pitch. I’ve always wanted to express myself, I’ve always wanted to try things. I’ve never gone into a game worrying.

I hope we don’t lose this one.

What’s going to happen if we get beat?

I’ve always been confident that we’re going to win the game, whoever I’ve played for. I’ve never been short of belief in a game of footy.

I’m so confident, I’m happy to play anywhere on the pitch. I’ve offered to play centre-back when United have been hit by injuries; I’ve even offered to play full-back. I reckon I could go there and do a good job, no problem. I remember Edwin van der Sar once busted his nose against Spurs and had to go off. We didn’t have a reserve goalie and I thought about going in nets because I played there in training a few times and I’d done alright. Against Portsmouth in the FA Cup in 2008, our keeper Tomasz Kuszczak was sent off and I wanted to go in then, but The Manager made me stay up top because Pompey were about to take a pen. I could see his point. Had I been in goal I wouldn’t have been able to work up front for the equaliser.

When I was a lad, I thought I’d be able to play football forever. These days, I know it’s not going to last, but the funny thing is I’m not too worried about the end of my career, the day I have to jack it all in. If I’m ever at a stage where I feel I’m not performing as well as I used to, then I’ll take an honest look at myself. I’ll work out whether I’m still able to make a difference in matches at the highest level. I’m not going to hang around to snatch the odd game here and there in the Premier League. I’ll play abroad somewhere, maybe America. I’d love to have a go at coaching if the opportunity comes up.

The thing is, I want to be remembered for playing well in football’s best teams, like United. I want to burn out brightly on the pitch at Old Trafford, not fade away on the subs’ bench.

*****

Hanging up my footy boots is a way off yet. There’s more stuff to be won. I want more league titles, more Champions Leagues – anything United are playing for, I want to win it. I’m into winning titles for the team because winning personal achievements, while being nice, isn’t the same as winning trophies with my teammates. And whatever I do, I do it to be the best that I can. I’m not good at being an also-ran, as anyone who has played with me will know.

For 10 years, it’s been all or nothing for me in the Premier League.

(#u5df184fc-98ff-5601-afea-67b8522b24ad)

Ten years in the Premier League. All the goals and trophies, injuries and bookings driven by one thought: I hate losing. I hate it with a passion. It’s the worst feeling ever and not even a goal or three in a match can make a defeat seem OK. Unless I’ve walked off the pitch a winner, the goals are pointless. If United lose, I’m not interested in how many I’ve scored.

I’m so bad that I even hate the thought of losing. Thinking about defeat annoys me, it does my head in, it’s not an option for me, but when it does happen, I lose it. I get angry, I see red, I shout at teammates, I throw things and I sulk. I hate the fact that I act this way, but I can’t help it. I was a bad loser as a lad playing games with my brothers and mates, and I’m a bad loser now, playing for United.

It doesn’t matter where I’m playing, or who I’m playing against either, I’m the same every time I put on my footy boots. In a practice match at Carrington before the last game of the 2009/10 season, I remember being hacked down in the area twice. I remember it because it annoys me so much. The ref, one of our fitness coaches, doesn’t give me a decision all game and my team loses by a couple of goals. When the final whistle blows and the rest of the lads walk back to the dressing room to get changed, laughing and joking together, I storm off in a mood, kicking training cones and slamming doors.

It’s the same when I’m competing off the pitch. I often play computer games with the England lads when I’m away on international duty. One time I lose a game of FIFA and throw a control pad across the room afterwards because I’m so annoyed with myself. Another night I lean forward and turn the machine off in the middle of a game because I know I’m going to lose. Everyone stares at me like I’m a head case.

‘Come on, Wazza, don’t be like that.’

That annoys me even more, so I boot everyone out of the room and sulk on my own.

It’s not just my teammates I lose it with. I have barneys with people as far away as Thailand and Japan when I play them at a football game online. They beat me; I argue with them on the headset that links the players through an internet connection. I’m a grown man. Maybe I should relax a bit more, but I find it hard to cool down when things aren’t going my way, and besides, everyone’s like that in my family. We’re dead competitive. Board games, tennis in the street, whatever it was that we played when I was a lad, we played to win. And none of us liked losing.

I sometimes think it’s a good thing – I don’t reckon I’d be the same as a footballer if I was happy to settle for second best. I need this desire to push me on when I’m playing, like Eric Cantona and Roy Keane did when they were at United. They had proper passion. I do too, it gives me an edge, it pushes me on to try harder. Those two couldn’t stand to lose. They didn’t exactly make many pals on the pitch either, but they won a lot of trophies. I’m the same. I doubt many players would say they’ve enjoyed competing with me in the past and I like to think that I’m a pain in the backside for everyone I play against. I’m probably a pain in the backside for people I play with as well, because when United lose or look like losing a game at half-time, I go mad in the dressing room.

I scream and shout.

I boot a ball across the room.

I throw my boots down.

I lose it with teammates.

I yell at people and they yell at me.

I’m not shouting and screaming and kicking footballs across the room because I don’t like someone. I’m doing it because I respect them and I want them to play better.

I can’t stand us being beaten.

I yell at players, they yell at me. I don’t take it personally when I’m getting a rollicking and I don’t expect people to take it personally when I dish it out to them. It’s all part of the game. Yeah, it feels like a curse sometimes, the anger and moodiness when I lose, but it’s an energy. It makes me the player that I am.

*****

My hatred of losing, of being second best, starts in Croxteth. My family are proud; Crocky is a proud place and nobody wants to let themselves down or their family down in the street where I live. My family haven’t got a lot, but we have enough to get through and my brothers and I aren’t allowed to take anything for granted as we’re growing up. We know that if we want something, we have to graft for it and I’m told that rewards shouldn’t come easily. I pick that up from my mum, my dad, my nan and my granddad. I learn that if I work hard, I’ll earn rewards. If I try at school, I’ll get the latest Everton shirt – the team my whole family supports – or a new footy if I need one. It’s where the will to work comes from.

This discipline, the desire to win and push myself, also happens away from school. I box at the Crocky Sports Centre with my Uncle Richie, a big bloke with a flat boxer’s nose. He hits pretty hard. I never actually scrap properly but I spar three times a week and the training gives me strength and an even harder competitive streak. Most of all it brings out my self belief.

I think we’re all confident in the family, but I don’t think it’s just the Rooneys. I reckon it’s a Liverpool thing. Everyone’s really outgoing in Crocky; everyone speaks their mind, which I like. As a kid, I learn to take that self-belief into the boxing gym. If ever I get into the ring with a lad twice my size I never think, Look at the size of him! I’m going to get battered. Doing that means I’m beat in my head already. Instead, I go into every fight thinking, I’m going to win, even against the bigger lads. One pal at the gym is called John Donnelly

(#ulink_ca5b01ad-aeb3-555a-ad9f-45cc6ec6f649), he’s older and heavier than me, but every time we spar together, Uncle Richie tells me to take it easy on him. He’s frightened John can’t handle me.

The desire to win and the self-belief on the footy pitch is there from the start too, even when I play for De La Salle, my school team. If ever a player knocks me off the ball in a tackle I work on my strength training in the gym the following week. I promise myself that it won’t happen again. No-one’s going to beat me in a scrap for the ball.

If I look like losing my hunger, Dad pushes me a bit. When I play football on a Sunday afternoon, he always comes to watch. He encourages me to get stuck in. He gets more wound up than me sometimes. He tells me to work harder, to try more. I play one match and it’s freezing, my hands are burning and my feet are like blocks of ice. I run over to the touchline.

‘Here, Dad, I’m going to have to come off. It’s too cold. I can’t feel my feet.’

His face turns a funny colour and he looks like he’s going to blow up with anger.

‘What? You’re cold?’

He can’t believe it.

‘Get out there and run more. Get on with it.’

I leg it around a bit harder to warm myself up. I’m only nine but I know that if Dad’s advice is anything to go by, I’ll have to toughen up even more if I want to be a proper footballer.

*****

All my heroes are battlers.

On the telly, I love watching boxers, especially Mike Tyson because his speed and aggression makes him so exciting. He always goes for the KO. When I watch Everton with Dad, my favourite player is Duncan Ferguson because he’s a fighter like Iron Mike, hard as nails, and I love the way he never gives up, especially if things aren’t going his way. He always gets stuck in. He also scores cracking goals. I could watch him play all day.

I love Everton, I’m mad for them. I write to the club and ask to become the mascot for a game when I’m 10 years old. A few weeks later a letter comes through the door telling me I’ve been chosen and I’m dead chuffed because I’m going to be walking out with the team for the Merseyside derby at Anfield. I step onto the pitch with our skipper, Dave Watson, and Liverpool’s John Barnes and I can’t believe the noise of the crowd. Later I go into the penalty area to take shots at our keeper, Neville Southall. I’m only supposed to be passing the ball back to him gently, but I get bored and chip one over his head and into the back of the net. I can see that he’s not happy, so when he rolls the ball back to me, I chip him again.

I just want to score goals.

A couple of years later, I get to be a ball boy at Goodison Park. Neville’s in goal again and as I run to get a shot that has gone out of play he starts shouting at me. ‘Effin’ hurry up, ball boy!’ he yells. It scares the crap out of me. Afterwards, I go on about it for ages to my mates at school.

That afternoon at Anfield, Gary Speed scores for us, which I’m dead chuffed about because he’s one of my favourite players. I can see that he works hard and he’s a model pro. Someone tells me that he grew up as an Evertonian as well, so when my mum buys me a pet rabbit a little while later, I decide to name him ‘Speedo’. Two days afterwards, the real Speedo signs for Newcastle and I’m moody for days.

*****

The training and the toughening up pays off.

I get spotted by club scouts when I’m nine years old and join Everton, which is like a dream come true. Then I play in the older teams at the club rather than my own age group because I’m technically better and physically stronger than the lads in my year. It’s mad; I don’t let on to the kids my age when I go to footy practice because I never play with them, I don’t really know them. When I’m 14 years old, I work with the Everton Under-19s. Me, a kid, playing against (nearly) grown blokes and competing, scoring goals, winning tackles. It feels great.

It gets better. At 15, I play in the Everton reserves. At 16, I’m in the first team. I know I can play at this level because I’m grafting hard and a place in the side is my reward, just like Mum and Dad taught me. Some of the coaches wonder whether I’ve got enough strength to mix it with the pros, but I know I have bags of it because boxing with Uncle Richie has given me the muscle.

When we play Manchester United’s reserves at our place, one of our coaches gives us instructions to be strong with Gary Neville, one of the stars of their first team. Everyone hates Gary Nev outside of Old Trafford because he’s United through and through. He’s always giving it on the pitch.

Not long into the game we both go up for a header. I accidentally catch him with my elbow and when I turn round to see if it’s had any effect on him, he doesn’t even flinch. The next time we go for a ball, he gets me back, clattering into me really hard.

It’s just another lesson in playing the game.

*****

I don’t change for 10 years. I take that same Crocky spirit onto the pitch throughout my career. Rolling up my sleeves, gritting my teeth and getting on with things helps me to a lot of goals at Manchester United. Like when I’m playing against Arsenal in January 2010. We’re one-up through an own goal from their keeper, Manuel Almunia. Arsenal are one of our rivals for the Premier League and beating them will go some way to helping us win the title. I know that if we score again we’ll probably take the game. Luckily, I manage to get us a second goal in the 37th minute, a strike that comes from not giving up.

I’m back defending, doing the dirty work, getting stuck in deep in the United half, which some strikers won’t do. I win the ball on the edge of our penalty area, lay it off to Nani and leg it, checking the position of the Arsenal defence as I push on towards them. I can see their full-back, Gael Clichy, on one side of me, but I’m focused on Nani. He’s bombing down the wing and I know a pass is coming my way if I can bust a gut to get into the right spot. He plays the ball into my path, I check my stride and thump a shot past Almunia first time which puts the result beyond Arsenal.

Three points in the bag.

When fans talk about the players with a desire to win games, they always mention the tacklers, the ball-winning midfielders, but desire to me is something different. It’s my goal against Arsenal; it’s sprinting for several seconds (again and again) to get onto a pass that might not come. Desire is playing out wide and making runs into the box and then tracking back to defend. Desire is risking injury to score. Desire is about trying your heart out and never giving up.

When the player stats came out for the Arsenal game – which they do for the Premier League every week – United’s fitness coach, Tony Strudwick, comes into the dressing room at training with all the facts and figures. He reads out the speed of my run during the build up to our second goal. Apparently, I covered 60 metres in a ridiculous time.

‘If you’d carried on running for another 40 metres at that pace, you’d have done the 100 metres in 9.4 seconds,’ he says, looking at the flipchart with a smile on his face.

Everyone starts cracking up. That stat makes me quicker than Usain Bolt.

*****

Sometimes I go too far. The same blanked-out feeling that happens whenever I score takes over when the red mist comes down.

During an away game against Fulham in March 2009, nothing seems to go right for United and I lose it, big time. We’ve been beaten by Liverpool the week before and The Manager wants us to bounce back at Craven Cottage. Instead, we go a goal down after a penalty is given against Scholesy, who gets sent off for deliberately handling the ball in our box. I come on during the second half in place of Berbatov and pick up a booking.

I’m getting fouled all the time. With a minute left, the ball comes to me and somebody hacks at my ankles again, but the ref gives the decision to the other lot. I’m furious. I pick up the ball, meaning to luzz it to Jonny Evans, but I misjudge it and the ball flies hard past the ref.

He thinks I’ve thrown it at him.

Oh no, here we go.

Out comes the second yellow card, then the red. Game over.

I can only think of one thing.

This is going to cost us the league.

Two defeats on the bounce; a suspension for the next match. I’m livid. The red mist comes on. As I walk off the pitch, the crowd start to jeer. Everything boils up inside me, my head’s banging. Sometimes in those situations, I get so angry that I never know what I’m going to do next. Thankfully, nobody gets in my way. The first thing that crosses my path is the corner flag. I lamp it. When I get to the dressing room, I punch the wall and nearly break my hand.

Paul Scholes is already sitting there, staring at me, just watching, as if it’s only natural for me to stick a right hook onto a concrete wall. He’s had time to shower and change. He’s looking smart in his official club suit.

‘You as well?’

I nod. My hand is killing me, I worry I might have busted it.

Nice one, Wayne.

Neither of us says a word. I sit there in my kit, fuming. Then a flash of fear comes into my head.

Oh god, The Manager’s going to kill me.

I hear the final roar from the crowd as the whistle goes. We’ve lost, 2–0. I hear the players’ studs clicking on the concrete path that leads to the dressing room. The door opens, but nobody talks as they sit down.

Silence.

Nobody looks at me. Giggsy, Jonny Evans, Rio, Edwin van der Sar, all of them stare at the floor. Then The Manager comes in and goes mad.

‘You were poor as a team!’ he screams. ‘We didn’t perform!’

He points at me, furious, red in the face, chewing gum.

‘And you need to calm down. Relax!’

The Manager’s right: I should relax, but he knows as well as me that the thought of losing is what drives me on in football, in everything, because he’s built the same way.

We both hate to be second best.

*****

Look, I’m not always happy about it.

After the Fulham game, I worry that people have an opinion on what sort of person I am because of what they see on the football pitch. They see me punching corner flags and shouting on the telly and must think that I’m like that in everyday life. They watch me going in hard in the tackle and probably assume that I’m some kind of thug. Sometimes, when people see me pushing my son Kai around the supermarket with Coleen, they stare at me with their jaws open, like I should be in my kit, shinpads and boots, arguing with the bloke collecting the trollies, or kicking down a stack of toilet rolls in a massive strop.

These are much cheaper down the road!

I’m not like that though.

When I first meet people I’m quiet and shy. I don’t open up that easily. I definitely don’t react badly in conversation and I don’t talk to friends and family in the same way as I talk to defenders and teammates. I don’t tell them to ‘eff off’ if things don’t go my way. I don’t turn the computer off if I’m watching my pals play. Losing it only happens when I’m competing. And only if I lose. It’s not something I’m proud of, but it’s something I’ve had to live with. I obviously have two very different mindsets: one that drives me on in the thick of a game and another I live my life by. The two never cross over.

(#ulink_e9abb2d3-b5cb-596e-9c71-f11b9499046b)John Donnelly, if you’re wondering, is now a professional boxer, a super flyweight. I spent a lot of time thinking about becoming a pro fighter too, but in the end I went for football.

(#u5df184fc-98ff-5601-afea-67b8522b24ad)

Matches are won and lost in the tunnel at Old Trafford, but the one thing I notice when I stand there for the first time as a United player is that it seems to go on for miles and miles. It’s long and dark. The ceilings are low and the players bump into one another as they walk to the pitch, almost shoulder to shoulder, because it’s so narrow and cramped. At the end, over the heads of players, officials and the TV cameramen, past the red canopy that stretches out onto the pitch, I can see the bright green blur of the grass, the floodlights and the crowd and some United fans hanging over the edge of the wall, shouting and waving flags.

It’s September 2004, United against Fenerbahçe. I’m about to make my first-team debut in the Champions League, a competition I’ve always dreamt of playing in.

The noise is mad, a buzz of 67,128 people, like a loud hum. When I first played here against United for Everton that buzz weighed me down a bit. It felt claustrophobic, it felt like a cup final. It did my head in. Now it pumps me up, but I can see why some players might feel trapped in here. Standing in the Old Trafford tunnel is like being in a box. If a footballer hasn’t been here before and they’re lined up next to the United players for the first time, it’s a terrifying moment. The weight of expectation is huge. A player has to be able to handle it if they’re going to be able to play well in front of the crowd here.

The Manager knows all about the importance of this place. The atmosphere is such a big deal that he even makes it his business to find out which players from the opposition have faced us here before and which ones haven’t. He tells us before a game; he knows who’s frightened and he wants us to know, too. Sometimes, as we get ready he lists names from the other lot, the lads playing here for the first time – they’re the ones who might not be on their game.

Later in the season I see it for myself. In some teams, the newly promoted ones usually, the players look scared as they start their walk to the pitch. Others look as if they’re starting their big day out for the season, or even their career. I can tell that they want to make the most of it, that they want to soak up the occasion. They clock their families in the stands and smile and wave like it’s their biggest ever achievement. As they make the slow walk from the tunnel in the corner of the ground to the halfway line they’re thinking one thing: Bloody hell, this is Old Trafford. Good news for us: the distraction can stop them from thieving a point. Bad news for them: they’re 1–0 down psychologically.

Now I’m about to make my first walk from the tunnel in a United shirt.

Today it’s all about my signing, my first game. I’ve been at the club nearly two months, but I haven’t played a minute of first team football after I busted a bone in my foot at Euro 2004, which has been annoying for everyone because I cost the club a lot of money. Still, the fans have been sound. I see them on the box and they’re saying how excited they are to see me here, but the one worry at the back of my mind is that it might take a while for them to accept me because I’m a Scouser. I might have to do something really special to win them over.

They’re on my side tonight, though. The crowd are singing my name before I even get onto the pitch.

‘Rooney!’

‘Rooney!’

‘Roooooooo-neeeeee!’

The shivers run down my spine as I walk into the glare of the floodlights for the first time in a red shirt. I’m bricking it.

It makes me laugh whenever I watch the tape of that game now: I come out of the tunnel with a chewy in my mouth and my eyes don’t seem to move as I walk across the grass. I don’t even blink. I stare straight ahead, trying to focus. The camera catches me puffing my chest out, getting myself ready, staring at the sky above the massive stand in front of me. I don’t look at anything in particular, just a space above that huge wall of people which seems to stretch up forever, full of red and black and white and some yellow and green.

I want to soak up the noise.

I don’t want to turn round.

I don’t want to see how massive everything looks.

Bloody hell, this is Old Trafford.

*****

Everything had been so quiet and calm before.

I sat in the dressing room ahead of the game and watched as everybody prepared themselves. I saw some of the biggest names in the league getting ready: winger Ryan Giggs stretching his skinny frame, Gary Neville bouncing on the spot; Dutch striker Ruud van Nistelrooy and Rio Ferdinand playing two touch with a ball, their passes pinging off the concrete floor. It was totally different to the atmosphere at Everton.

At Goodison it was rowdy and loud, people shouted, yelled, issued instructions. It dawned on me that some teams have to win games through team spirit; they have to fight harder for one another. Pumping up the dressing room builds a strong attitude. It helps to psyche out the opposition. Before the Fenerbahçe game I noticed that everyone in a United shirt prepared in their own way – calmly, quietly. No one screamed or shouted. They knew that if we played well we’d win the game no problem. There was no need to scream and shout.

I felt like I’d come to the right place.

*****

I make a good early pass. Well, I take the kick-off so I can’t really mess that one up. My first proper touch comes a few moments later and I play that one well, too. I’m running on pure adrenaline.

I want to impress everyone. I want to show them what I can do.

Then, in the 17th minute I score my first-ever United goal.

Ruud plays me through. I’m one-on-one with the goalie and everything slows down – the weirdest feeling in football. It seems to take an hour before I get to the penalty area, as if I’m running in really thick mud. My brain goes into overdrive like it always does in this situation, as if it’s a computer working out all the sums needed to score a goal.

Is the keeper off his line?

Is a defender closing in on me?

Should I take it round the goalie?

Should I shoot early?

Will I look a divvy if I try to ’meg him and I hit the ball wide?

A one-on-one like this is probably the hardest thing to pull off in a game because there’s too much time to process all the info, too much time to think. Too much time to overcomplicate what should be an easy job.

I’m just going to put my foot through it, see what happens.

I hit the ball with all my strength and it rockets into the back of the net. Old Trafford goes nuts. Right now I doubt anyone cares whether I’m a Scouser or not, I’m off the mark. Mentally I loosen up, I feel like I can express myself a little bit, try a few things. Not long afterwards, Ryan Giggs plays a ball across to me. I drop a shoulder, do my defender and fire the ball into the bottom corner. Now the crowd are singing my name again; now I’m daring to dream.

What would it be like to score a hat-trick at Old Trafford?

I find out in the second half. There’s a free-kick on the edge of the Fenerbahçe area and Giggsy, with all his amazing ability and experience, puts the ball down to take it, but I want it. I’ve got bucketloads of confidence and I fancy my chances, just like I did whenever I got into the ring with a bigger lad in Uncle Richie’s boxing gym. I just know I’m going to score – it’s mad, I can almost sense it’s going to happen.

‘Giggsy, I’m putting this one away.’

He hands the ball over and I curl a shot into the top left-hand corner, easy as you like. Goal number three, a hat-trick on my Old Trafford debut.

We win 6–2 and in the dressing room afterwards everyone seems to be in a state of shock. I don’t think anybody can believe what I’ve just done out there. I can’t get my brain around it either. Rio sits there shaking his head, looking at me like I’ve just landed from outer space. The older lads, like Gary Nev and Giggsy, are thinking the same thing, I can tell, but they’re keeping it in. They’ve probably seen amazing stuff like this loads of times before with players like Eric Cantona and David Beckham, so they stay silent. They probably don’t want to build me up just yet. To them, my hat-trick is part of another day at the office, just like it is to The Manager, who shakes my hand and tells me I’ve made a good start to my United career.

Nobody’s getting carried away.

There isn’t a massive party to enjoy afterwards, no one gets bevvied up or hits the town. Some players I know would be out with their teammates having scored a hat-trick on their debut. Instead, everyone goes home. But not me, I haven’t even got a gaff to go to. Coleen and I are living out of a hotel while we look for a new house, so to celebrate the start of my Old Trafford career we order room service and watch the match highlights on the box, but it all seems so weird.

I feel numb.

I always knew that I was going to experience a massive change in my life by signing for United, but I didn’t expect it to be this big. The strangest thing is, I don’t feel like I’m on the verge of anything special. I don’t feel like a special player. I’ve never felt that way, even as a kid playing for Everton. Tonight as we sit eating our room service tea I feel confident, confident that I have the ability to help United win games and trophies, but I can see that everyone else in the dressing room has the ability to do that, too.

At Old Trafford I’m nothing special; I’m not a standout player. But I reckon I can help United to be a standout team.

*****

Despite my brilliant start, it doesn’t take long for me to get up Roy Keane’s nose.

On the pitch, Roy’s a leader; I can see that from training with him. He yells a lot, he inspires through example, but he rarely dishes out instructions – he’s just really demanding, always telling us to graft harder.

He can be just as demanding off the pitch.

On the night before my first away game against Birmingham City (a 0–0 draw), the squad sits down for tea in the team hotel, a fancy place with a private dining room just for us, complete with plasma screen telly. Roy’s watching the rugby, but the minute he gets up to go to the loo, I swipe the controls and flip the channel so the lads can watch The X Factor on the other side. Then I stuff the remote in my trackie pocket.

When Roy comes back and notices Simon Cowell’s face on the telly, he’s not happy. He starts shouting.

‘Who’s turned it over? Where’s the remote?’

I don’t say a word. Nobody does. Everyone starts looking around the room, trying to avoid his glare.

‘Well, if no one’s watching this, I’ll turn it off.’

Roy walks up to the telly and yanks the plug out of the wall. The lads sit there in silence. There isn’t a sound, apart from the scrape of cutlery on plates. It’s moody.

After dinner we all crash out early, but at around midnight, I get a knock on the door. It’s the club security guard.

‘Alright Wayne,’ he says. ‘Roy’s sent me. He wants to know where the remote controls are.’

I realise it’s Roy’s way of letting on to me that he knows exactly what’s happened. It’s a message.

You’re for it now.

I hand them over and wonder what’s going to happen. But the next day he says nothing about it.

*****

When I first sign for United, I think back to the times I’d watched them winning trophies and league titles on the telly. It happened a lot. I’d see their ex-players being interviewed on Sky Sports News or Football Focus and whenever their names came up on the screen it would always read: ‘Steve Bruce: Premier League Winner’, or ‘Teddy Sheringham: Treble Winner.’

I want that to be me.

Later, when I train at Carrington for the first time, Gary Neville gives me some advice. He says, ‘The thing with this team is, no matter how much you’ve achieved, no matter how many medals you’ve won, you’re never allowed to think that you’ve made it.’

I’m a bit nervous about meeting Gary Neville again. I’d whacked him during that reserve game after all – I worry that he’ll remember it. It doesn’t help that just before my arrival one of the papers runs a story about Gary hating Scousers. Apparently he’s told a reporter, ‘I can’t stand Liverpool, I can’t stand Liverpool people, I can’t stand anything about them.’ I’m a bit worried that me and him won’t get on.

I ask him whether he’s really said it, whether he really hates Scousers. He tells me it’s rubbish – he’d been chatting about the Liverpool side of the ’80s. He’d grown up watching them win trophy after trophy. He hated their team; he wasn’t having a pop at the people in the city, just the club. That’s good enough for me. As an Evertonian I can see his point.

I like Gary straightaway, he’s a funny lad. We warm up together in training by playing keep ball in one of the boxes marked out on the training ground turf. I spoon the ball and give a pass away. From behind me I hear him winding me up. ‘Flippin’ heck, how much did we pay for Wazza?’

At lunch after the practice game, he doesn’t stop talking, he goes on and on and on, but in a nice way. Sometimes when he’s off on one – about music, his guitar playing, football – it’s as if he doesn’t have the time to stop for breath, especially if he’s talking about United. He’s the most passionate player I’ve ever met. He’s hard too, on the pitch and off it. He gets stuck into tackles; in the dressing room I notice that The Manager has a go at Gaz probably more than any of the other players in the team because he can handle it. He isn’t soft like some footballers can be.

When he’s out there playing, he’s the spirit of The Manager. He carries that same ambition to win, that same desire. There’s one game where I sit on the bench with him and he even acts like The Manager. He watches the way our match unfolds and he studies the tactics of the opposition. Then with 20 minutes to go he sends a youth team player out to warm up on the touchlines for a laugh without The Manager knowing. Talk about cheek.

Gary and players like Paul Scholes and Ryan Giggs bring a lot of experience to the dressing room. In my first few months at the club there are times when teams who can’t live with us on paper defend for their lives and nearly get away with it, even at Old Trafford. They hassle us and battle for every tackle; they park the team bus in front of their goal every time we win back possession. I get frustrated. I lose my patience and start hitting risky long balls and taking pot shots in a desperate attempt to win the game, but Gary calms me down.

‘Keep trying, Wazza, keep playing. A chance will come.’

Nine times out of ten, he’s right.

I’m not the only one to hear the advice. There’s a young lad called Ronaldo who signed a season earlier from Sporting Lisbon for a cool £12.2 million, and everyone starts talking about how he’s going to be the future of the club alongside me. There’s nothing on him though: he’s a bag of tricks, but he’s skinny. He’s got braces on his teeth, slicked hair and he’s spotty. Ronaldo looks like a boy. It’s hard to believe we’re around the same age.

Wonder how he’s going to turn out?

*****

As I get settled at the club, the size of United amazes me. I watch the news at home and no matter where the cameras are, the Middle East, somewhere in Africa, wherever, there’s always a little kid wearing an old United shirt. At first it freaks me out, but then fame always has done.

The first time I’d heard that fans were going into the Everton club shop for my shirt, it felt weird. It used to confuse me when people wanted my autograph in the street. I was 14 when it happened for the first time, playing a youth team game for Everton. When the final whistle went, a bloke came up to me and asked for my signature.

‘I’m going to keep this because when you grow up it’s going to be worth a lot of money,’ he says.

Seeing myself on the box was even weirder.

I played in both legs of the FA Youth Cup final in 2002 against Aston Villa and picked up the Man of the Match award afterwards, even though we lost. Sky interviewed me for the show after one game and I watched it back when I got home because my mum had videoed it. I hated it when I saw the clip: it didn’t look like me, it didn’t sound like me. It was weird.

At United I realise straightaway that the attention is much more intense and the players are treated like rock stars. It’s scary because the team has fans everywhere and people recognise me wherever I go. In the street, blokes, mums and kids come up to me for autographs, and most of the time I’m comfortable with it, but there are moments when it gets too much. I’m only 18 years old; it’s difficult to deal with the attention sometimes.

Every time I go shopping I see a picture of myself in the papers the next day; one night I go out for a meal and people point and stare when I’m sitting with my family. It’s like I’m a waxwork from Madame Tussauds rather than a person. A party of people starts telling the family on the next table that ‘it’s that Wayne Rooney over there’. Then they start pointing and taking pictures with their phones on the sly. In the shops I’m happy to sign stuff, pose for photos and talk to people, but it’s a bit much when I’m eating my tea.

I decide I’m not going to bang on about fame to my mates or moan about it to the lads at the club though, because that’s what so many other footballers do. Signing for United means I have to deal with this situation. It’s part of my job, but I realise I’m growing up fast. I’m learning how to live my life under a mad spotlight.

One afternoon, shortly after the Fenerbahçe game, I go to the garage to fill the car up. As I put the petrol in, a bloke pulls up next to me and winds his window down.

‘Here, Wayne, you fill up your own car yourself, do you?’

Like anyone else is going to do it.

(#u5df184fc-98ff-5601-afea-67b8522b24ad)

The Manager’s office is right in the thick of things at Carrington, United’s training ground, upstairs from the changing rooms, next to the canteen. If someone was to wander into the club at lunch on a Monday without checking the footy results first, they’d know exactly how United have got on just by taking a look at The Manager’s body language. As he buzzes around the dining tables at lunch, having a crack with people, chatting, joking (or not chatting, not joking), it’s written all over his face.

If we’ve won, like against Fenerbahçe, he laughs with everyone; he talks about the last game and gets excited about the next. If we’ve been playing really well, he tells unfunny jokes and shouts out silly trivia questions while we eat our lunch or get changed.

‘Lads, name the current players from the Premier League with a World Cup winners’ medal?’ he says.

He keeps us guessing for ages. I don’t think he actually knows the answers half the time. If he does, he never gives them to us when we pester him afterwards.

When he’s in a really good mood, the stories start. He goes on about his playing career and the goals he scored as a striker for Dunfermline and Rangers. He tells the tale about the time he once played with a broken back. Apparently everyone in the squad’s heard it – how bad the pain was, how he got the injury. The Manager tells the ‘Broke Back’ tale so many times that it’s not long before I know it from beginning to end. But it doesn’t stop him from telling it again, especially when he feels there’s a point to be made about injuries. The funny thing is, even though he talks about his playing days a lot, I’ve never seen any video evidence of his goals, so I don’t know how good or not good he was. I doubt he was as great as he makes out.

In my first few months at the club, I realise that when the atmosphere around Carrington is good – when we’re winning – I can go into The Manager’s office whenever I want, just for a chat. To be honest, I like going in there. It’s a big room, bigger than some dressing rooms I’ve been in. A huge window overlooks the training pitches so he can see just about everything that’s going on.

‘Wayne, the door is always open if you need to speak to me,’ he says.

When I go in there for the first time, shortly after my debut, we talk about the game, our upcoming opponents, how I should play to exploit their weaknesses. We talk about the title race and the league’s best players: Chelsea are strong he reckons, Arsenal and Liverpool, too. He tells me how he sees our team shaping up, how me and Ronaldo are going to do. We talk about horses, he tells me about his wine collection – apparently he has a big cellar at home. He doesn’t mention retirement, even though he’s at an age when most people would be happy to put their feet up, but that’s the measure of the man, I suppose.

I feel I can have a laugh with him as we’re playing well. I even make out that I already know the team for our next match, days before he’s announced it.

‘Who’s playing up front with me, boss? Am I playing up top on my own?’

He laughs. ‘Oh, so you think you’re playing, do you? Who else is in the team then?’

I rattle off a few names.

‘Yeah, well, you’re not too far off.’

As the season progresses, I discover that the only time I don’t like going in there is when I’ve been called up to see him. That usually means he’s unhappy with something I’m doing, or not doing, and it always happens when training has finished for the day. There’s a telephone in the players’ changing room. When it starts to ring, the lads know what’s coming next: a summons from The Manager. Someone’s going to get it.

‘Can you send Wayne to my office, please?’

When it’s me, the lads make funny noises, like I’m going to be in loads of trouble. Some of them make a sharp intake of breath, or whistle, just to wind me up.

Like the time in January 2005 when we’re preparing to play Liverpool. He makes the phone call. When I go into his office and sit on the big settee, he tells me I’m not playing well enough. He tells me I haven’t been thinking properly on the pitch.

‘You’ve got to start concentrating more, Wayne,’ he says. ‘I want you to keep things simple. You’re going out wide too much and I want you to stay up in the penalty area.’

I argue. I think it’s an unfair assumption of my game, but I accept his advice and get on with it. At Anfield I stay in the box as much as I can, I don’t drift wide. Then I answer him in the best way possible: I score the winning goal. Maybe that was his plan all along. Maybe he wanted to wind me up.

After a defeat, The Manager’s mood can be quite dark; he doesn’t talk to the players or joke around for a couple of weeks. He speaks to us as a group in team talks, but that’s as far as it goes. If anyone passes him at the training ground, he doesn’t say a word to them. I learn pretty quickly that it’s best to stay out of his way after a bad result. In my first few months at the club, when I see him eating in the canteen after a defeat, I steer clear. I get my food, keep my head down and walk to my table as quickly as I can.

*****

There’s one thought I can’t shake: the first time I was introduced to The Manager properly was when I signed for United at Old Trafford in the summer of 2004. I’d spoken to him once or twice when Everton played United – a quick hello in the tunnel, but that was it. The day I joined the club, I met him at Carrington and I was dead excited.

He drove me to Old Trafford and told me how I was going to fit into the team and how he wanted me to play. He told me about my new teammates: winger Ryan Giggs, England internationals Rio Ferdinand, Paul Scholes and Gary Neville; my new strike partner, Ruud van Nistelrooy – a goal machine.

I talked about the times I’d played at Old Trafford for Everton, how I’d been blown away by the atmosphere there. I’d even said to my dad afterwards, ‘I want to play for them one day.’

It was surreal. I’d been watching him on the telly for years with players like Eric Cantona and David Beckham, but I never imagined that it would happen to me. Later, when word got around back home about my day, a mate sent a text over.

‘BLOODY HELL!!!’ he said. ‘CAN’T BELIEVE U’VE GOT FERGIE CHAUFFEURING U AROUND.’

The Manager seemed like a really good bloke, but the next day I experienced his legendary influence first hand. It was a nice afternoon, so I drove over to Crocky to see the family. On the way, I spotted Mum and Dad in the car park of the local pub and I pulled over to say hello. We decided to go in for a drink, a diet pop for me. I was only there for 10 or 15 minutes before I went home, but a day later, The Manager called me into his office. My first summons.

‘Wayne, what were you doing in that pub in Croxteth yesterday?’ he said.

I couldn’t believe it. I’d not been in there long, but long enough for someone to make a phone call and grass me up. To this day I still don’t know who did it. I left the meeting knowing one thing, though: The Manager has eyes and ears everywhere.

Within weeks I know plenty more stuff. He has an amazing knowledge of the game. When we play teams, he knows everything about the opposition, and I mean everything. If a player has a weakness on his right foot, he knows about it. If one full-back is soft in the air, he’ll have identified him as a potential area of attack. He also knows the strengths of every single player in the other team’s squad. Before games we’re briefed on who does what and where. He also warns us of the players we should be extra wary of.

His eye for detail is greater than anyone else’s I’ve ever worked with, but that’s one of the reasons why I signed for him. That and the fact that he’s won everything in the game:

The Premier League.

The FA Cup.

The League Cup.

The Community Shield.

The Champions League.

The UEFA Cup Winners’ Cup.

The UEFA Super Cup.

The World Club Championship.

The Intercontinental Cup.

You can’t argue with a trophy cabinet like that.

*****

I start my first league game for United against Boro’ in October and we begin the game badly. By now I’ve learned that The Manager expects one thing from us when we play: to win.

After half an hour, we’re a goal down and unable to get a foothold in the game. I’m not playing well and he’s shouting at me from the dugout. I pretend not to hear him. I don’t turn around, I don’t want to make eye contact. I know he’s shouting, but I can’t really make out what he’s saying because the crowd’s so loud. I definitely don’t want to get up close enough to hear him because I know it’ll be scary.

He looks terrifying on the touchline.

We eventually draw 1–1 against Boro’ but The Manager isn’t happy. It’s a game we should have won and in my first few months at United I learn quickly that we have to attack until the end of a game, no matter what the score is. That’s The Manager’s football philosophy. He tells us that he wants the players to get behind the ball when we’re defending and move with speed when we’re attacking. He wants us to draw the opposition in, to lull them into a false sense of security. ‘That’s when they’ll start stringing passes together, growing in confidence,’ he tells us. ‘But it’s a trap.’

That’s when we’re supposed to win the ball back and punish the other lot with some quick passes through midfield. ‘The opposition won’t stand a chance,’ he says.

The ball needs to be fired out wide and hit into the box to me and Ruud. My role in all of this is to make good runs in behind the defence. When the ball comes to me in deeper areas I’m supposed to hold it up and bring other players into the game, like Ronaldo. When the ball gets played out wide I have to head for the box and get on the end of crosses.

If we play well, Carrington is a happy place. After Fenerbahçe, The Manager allows us to enjoy our training. We watch videos of all the things we’ve done well in a game and he tells us to continue playing the way we are. He wants us to keep up our winning momentum. If we can do that, the canteen is a happier spot for everyone.

(#u5df184fc-98ff-5601-afea-67b8522b24ad)

Arsenal, 24 October 2004.

Needle match.

It’s a needle match because Arsenal have been title rivals with United for over a decade. The two teams have had some pretty tasty games with one another in the past and there have been rucks, 20-man scraps and red cards.

The worst game took place the previous season when it kicked off between both sets of players. As I watched the game on the telly after playing for Everton, a row started between Ruud and some of the Arsenal lads – the type of fight fans always love watching. It began when striker Diego Forlan won a penalty; the Arsenal lot began complaining that he’d dived for it and when Ruud then spooned his spot-kick, a mob of their players crowded around him and got in his face, winding him up. They were angry because they thought he had got their skipper, Patrick Viera, sent off earlier in the game, but the reaction was horrible. Martin Keown was the worst; he screamed at Ruud and jumped up and down like a right head case. His eyes nearly popped out. He looked like a zombie from a horror film.

Now it’s my turn to be in the thick of one of the biggest battles in the Premier League.

In the build up there’s loads of talk about the atmosphere of the match around town; the papers are going on about the previous season’s clash and I can’t turn on the telly without seeing that scuffle between Ruud and Keown. It’s obviously bothering Ruud because he’s been quiet for days. There’s an atmosphere about him. He’s withdrawn and he doesn’t talk to the other lads in the dressing room at Carrington as much.

In the short time I’ve known Ruud he’s always looked focused, but this week there’s something else going on inside his head, something driving him on. No one asks him about the game or his mood, but I can tell that he wants to prove a point. I reckon that his penalty miss against Arsenal must have weighed on him for months.

When it comes to the match, both teams are up for it – the Arsenal players even hug one another before the game, like they’re getting ready to go into a battle – and once the footy gets underway the atmosphere at Old Trafford is horrible, moody, because the two sides are at one another’s throats. It’s my 19th birthday, but nobody’s dishing out any prezzies on the pitch.

The game is evenly matched, though. We’re at home and looking to kick-start our season again after those disappointing draws against Birmingham and Boro’; Arsenal are on a 49-game unbeaten streak and they’re a great team – Dennis Bergkamp, Ashley Cole, Thierry Henry and Patrick Vieira are all playing and they’re on top of their game, but the thing is they know it. All week they’ve been banging on about how great it will be to make it to 50 games undefeated at Old Trafford.

Big mistake. They’ve fired us up.

Fifty games unbeaten? No way. Not at our place.

Already I know that this is the way a footballer has to think if they’re to do well at United.

Nobody gets to believe that we’re a pushover.

The tackles fly in thick and fast from the start, every loose ball matters. After a tight first half, we go in at the break goalless, then in the second, Ruud gets a chance to make up for last year’s penalty miss when on 73 minutes I burst into the area. Sol Campbell makes a fair tackle and nicks the ball but his momentum brings me down. He decks me. I hear a whistle and I know straightaway that the ref is pointing to the spot because the crowd are going nuts and Ashley Cole and Sol are complaining, shouting that I’ve dived, that I’ve not been tripped. The funny thing is, they’re both right and wrong: I haven’t been fouled, but I haven’t dived either. Instead, there’s been a coming together and it’s given the ref a decision to make. Thankfully for us he gives the penalty.

Everyone starts looking to Ruud, who’s already got the ball in his hands. I know I’m not going to get a look-in when it comes to taking this pen because he wants it badly and everyone’s willing him on to score, like it’s payback time. It feels like the whole of Old Trafford is wishing the ball into the net, but as I watch, Ruud doesn’t seem to be setting himself up right. I’ve seen him practising pens in training every day and he always goes the same way. He hits his shot hard and the keeper usually has no chance. When he steps up to the spot this time, he changes his usual direction and strikes the ball poorly. Straightaway I know that if Arsenal’s goalie, Jens Lehmann, guesses right he’s going to save the shot because there’s not enough pace on it.

I think he’s fluffed it.

Ruud’s ’mare is going to get even worse. Everything seems to stop still. But then Lehmann reads it wrong. He throws himself in the opposite direction and as Ruud’s shot hits the back of the net the whole place erupts and he’s off, running to the fans. He’s not looking to his teammates or the bench or The Manager, but I can see there’s joy and relief all over his face. It’s probably the most genuine emotion I’ve ever seen in a footballer after scoring – it’s like Ruud has had the weight of the world lifted off his shoulders.

I chase after him as he runs to the corner flag and drops to his knees, head back. He’s screaming, his fists are clenched. I think of Stuart Pearce when he scored for England against Spain in Euro 96 during a penalty shootout in the quarter-finals. He went mental, the memory of one blobbed penalty against West Germany in the 1990 World Cup semis wiped off with a single kick of the ball.

Now it’s the same for Ruud.

It’s pure emotion.

I want to celebrate too, but I can see by the way he’s looking up at the sky, soaking up the huge Old Trafford roar, that he needs this moment to himself. Fair play to him, he deserves it.

The Arsenal lot look absolutely gutted, and now we’re a goal to the good I know we’ll stop them from getting that 50th undefeated result. The thought of it pushes the team on for the last 15 minutes and we defend strongly while pressing for a second on the break. Then in the 90th minute I put the final nail into Arsenal’s coffin.

Our midfielder, Alan Smith – Yorkshire lad, bleached blond hair – gets the ball out wide; I make a run into the box when his pass comes over. As I leg it for the ball an Arsenal defender starts kicking at my heels. It’s Lauren, he’s trying to trip me, but I’m not going down. I want my first league goal for United so badly that I manage to keep my balance. It leaves me with a tap-in to score.

Ta, very much. 2–0.

My first Premier League strike for United.

‘Happy birthday to me.’

*****