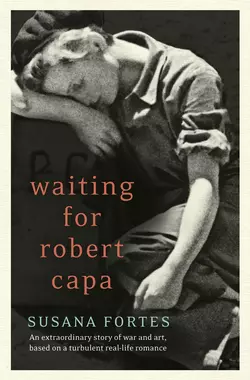

Waiting for Robert Capa

Susana Fortes

A gorgeously written, ENGLISH PATIENT-style novel about the real-life romance between the war photographers Robert Capa and Gerda Taro during the Spanish Civil War. Optioned to be the next film by Michael Mann (PUBLIC ENEMIES, THE INSIDER, MANHUNTER, COLLATERAL).Love, war and photography marked their lives. They were young, anti-Fascist, good-looking, and nonconformist. They had everything in life, and they put everything at risk. They created their own legend and remained faithful to it until the very end…A young German woman named Gerta Pohorylle and a young Hungarian man named Endre Friedmann meet in Paris in 1935. Both Communists, Jewish, exiled, and photographers, they decide to change their names in order to sell their work more easily, and so they become Gerda Taro and Robert Capa. With these new identities, they travel to Spain and begin to document the Spanish Civil War. Two years later, tragedy will befall them – but until then, theirs is a romance for the ages.Based on the true story of these legendary figures and set to be the next film by award-winning director Michael Mann, WAITING FOR ROBERT CAPA is a moving tribute to all journalists and photographers who lose their lives to show us the world's daily transformations.

Epigraphs (#u1eb7add9-d54b-5773-be81-dad2513d616a)

Perhaps if I wanted to be understood or to understand I would bamboozle myself into belief, but I am a reporter; God exists only for lead writers.

—The Quiet American, Graham Greene

A true war story is never moral. It does not instruct, nor encourage virtue, nor suggest models of proper human behavior, nor restrain men from doing the things men have always done. If a story seems moral, do not believe it.

—The Things They Carried, Tim O’Brien

A day with nice light, a cigarette, a war …

—Comanche Territory, Arturo Pérez-Reverte

To Gerda Taro, who spent one year at the Spanish front and who stayed on.

—Death in the Making, Robert Capa

Table of Contents

Cover (#ub9471069-14f0-5f78-ad44-4a1eb7a317e4)

Title Page (#u0f5c909c-da23-5be4-b542-90eacba2cf41)

Epigraphs (#u07303adc-b0e0-51a2-b6fe-cdfbda545de8)

Chapter One (#u1693f1e7-0859-5f7d-9a29-90c0a6a1f099)

Chapter Two (#uc19003d4-e1aa-5333-b2a5-f6415200e397)

Chapter Three (#uc6852e8b-93e8-56da-891a-f1d2c50f2ec3)

Chapter Four (#ufe05f82a-d199-596e-a756-cfd7791c7efd)

Chapter Five (#u06b52f9a-85f8-5dc7-b956-9dcd5186d8f4)

Chapter Six (#u2cd90548-2396-5845-8b6d-d2a9f4d63639)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-one (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-four (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Credits (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#u1eb7add9-d54b-5773-be81-dad2513d616a)

It’s always too late to turn back. Suddenly you wake up one day knowing that this will never end, that it will always be like this. Take the first train, make a quick decision. It’s here or there. It’s black or white. This one I can trust, this one I can’t. Last night I dreamt I was in Leipzig at a gathering with Georg and everyone at the lake house, around a table covered in white linen, a vase of tulips, John Reed’s book, and a pistol. I spent the whole night dreaming about that pistol and woke up with the taste of gunpowder in my throat.”

The young woman closed the notebook on her lap and looked up at the scenery passing at a rapid speed outside her window; blue countryside between the Rhine and the Vosges mountains, villages with wooden houses, a rose bush, the ruins of a castle destroyed during one of the many medieval wars that devastated Alsace. This is how History enters us, she thought, not knowing that this very territory would soon return to being a battlefield. Battle tanks, medium-range Blenheim bombers, fighter biplanes, the German air force’s Heinkel He 51s … The train passed in front of a cemetery and the other passengers in the compartment crossed themselves. It was difficult to fall asleep with all the wobbling. She kept hitting her temple against the window frame. She was tired. Closing her eyes, she could see her father bundled up in a thick cheviot coat, saying good-bye to her on the station platform at Leipzig. The muscles of his jawline shut tight, like a stevedore under a canopy of gray light. Grind teeth, clench fists inside pockets, and swear in a very low voice in Yiddish. That’s what men who don’t know how to cry do.

It’s a question of character or principles. Emotions only worsen matters when the time comes to leave in a hurry. Her father always maintained a curious debate with tears. They were prohibited from crying as children. If the boys mixed themselves up in a fistfight, and lost in the scuffle, they could not return home to complain. A busted-up lip or a black eye was proof enough of their defeat. And crying was prohibited. The women didn’t have to follow the same code of conduct, of course. But she loved her brothers and there was nothing in this world that would allow her to accept being treated differently. She was raised within those rules. So, there were no tears. Her father knew very well what he was saying.

He was old-fashioned, from Eastern Europe’s Galicia, still using rubber-soled peasant shoes. As a child, she remembered his footprints alongside the farm’s henhouse being as large as a buffalo’s. His voice during the Sabbath ceremony in the synagogue was just as deep as his footprints in the garden. About two hundred pounds of depth.

Hebrew is an ancient language that contains the solitude of ruins within, like a voice from the hillside calling out to you, or the song of the siren heard on a distant ship. The music of the Psalms still moves her. She notices a cramp in her back when she hears it in dreams, like now, as the train travels to the other side of the border, a type of tickling sensation just below her side. Perhaps that’s where the soul lives, she thought.

She never knew what the soul was. As a child, when they lived in Reutlingen, she believed that souls were the white diapers that her mother hung out to dry on the balcony. Oskar’s soul. Karl’s. Her own. But now she doesn’t believe in those things. The God of Abraham and the twelve tribes of Israel would break her neck if they could. She did not owe them anything. She preferred English poetry a million times over. One poem by Eliot can free you from evil, she thought; God didn’t even help me escape that Wächterstrasse prison.

It was true. She left by her own means, self-assured. Her captors must have thought that a blond girl, so young and so well-dressed, could not be a Communist. She thought it, too. Who would have known she would end up taking an interest in politics frequenting the tennis club in Waldau? A deep tan, white sweater, short pleated skirt … She liked the way exercise made her body feel, as well as dancing, wearing lipstick, donning a hat, using a cigarette holder, drinking champagne. Like Greta Garbo in The Saga of Gosta Berling.

Now the train had entered a tunnel, sounding a long whistle. It was completely dark. She breathed in a deep smell of railway emanating from the car.

She doesn’t know exactly when everything started to twist itself. It happened without her realizing it. It was because of the damn cinders. One day the streets started smelling like a railroad station. It reeked of smoke, of leather. Well-polished high boots, saddlery, brown shirts, belt buckles, military trappings … One Tuesday, as she was leaving the movie theater with her friend Ruth, she saw a group of young men in the Weissenhof district singing the Nazi hymn. The boys were just pups. They did not pay it further mind.

Later, it was prohibited to buy anything in Jewish stores. She remembered her mother being thrown out of a gentile store, bending over to pick up her scarf that had fallen in the doorway as a result of the shopkeeper’s push. That image was like a hematoma in her memory. A blue scarf speckled with snow. The burning of books and sheet music began around the same time. Afterward, the people began filling the arenas. Beautiful women, healthy men, honorable fathers with families. They weren’t fanatics, but normal people, aspirin vendors, housewives, students, even disciples of Heidegger. They all listened closely to the speeches, they weren’t being fooled. They knew what was happening. A choice had to be made and they chose. They chose it.

On March 18, at seven in the evening, she was detained by SA storm troopers at her parents’ home. It rained. They came looking for Oskar and Karl, but since they did not find them, they took her instead.

Broken locks, open armoires, emptied-out drawers, papers everywhere … During the search they found the last letter Georg had sent from Italy. According to them, it spewed Bolshevik garbage. What did they expect from a Russian? Georg was never able to talk about love without resorting to the class struggle. At least he had been able to flee and was out of danger. She told them the truth, that she had met him at the university. He studied medicine in Leipzig. They were sort of boyfriend and girlfriend, but they gave each other their own space. He never accompanied her to parties her friends invited her to and she never asked about his gatherings until dawn. “I was never interested in politics,” she told them. And she must have appeared convincing. One can suppose her attire helped. She wore the maroon skirt her aunt Terra had given her for graduation, high-heeled shoes, and a low-cut blouse, as if the SA had come to get her just as she was going out dancing. Her mother always said that dressing properly could save one’s life. She was right. Nobody placed a hand on her.

As they drove through the corridors toward her cell, she heard the shouting coming from interrogations taking place in the west wing. When it was her turn, she played her part well. An innocent young woman, and frightened. In reality, she was. But not enough to stop her from thinking. Sometimes, staying alive solely depends on keeping your head in place and your senses alert. They threatened to keep her in prison until Karl and Oskar turned themselves in, but she was able to persuade them that she really couldn’t supply them with any information. Choked voice, eyes wide-open, tender smile.

At night she stayed on her cot, silent, smoking, staring at the ceiling, her ego a bit bruised, wanting to end the whole charade once and for all. She thought about her brothers, praying that they’d been able to go underground, cross to Switzerland or Italy, like Georg. She also planned her escape for when she was able to get out of there. Germany was no longer her country. She wasn’t thinking of a temporary escape, but of starting a new life. All the languages she learned would have to come of some use. She had to find a way out. She’d do it. That she was sure of. This is why she had a star. The train came back out into the light again as the wagon clattered through the mountains. They had entered another landscape. A river, a farm surrounded by apple trees, hamlets with chimneys blowing smoke. Children playing on top of an embankment lifted their arms toward the edge of dusk, moving their hands from left to right as the train abandoned the last curve.

The first shooting star she saw was in Reutlingen, when she was five years old. They were walking back from their neighbor Jakob’s bakery with a poppy-seed cake and condensed milk for dinner. Karl was ahead, kicking rocks; she and Oskar always lagged behind, and so Karl, with his big-brother finger, pointed to the sky.

“Look, Little Trout.” He always called her that. “Make a wish.” Up there darkness was the color of prunes. Three little children, interlinking arms over shoulders, looking up at the sky, while they fell, two by two, three by three, like a handful of salt, those stars. Even now, when she remembers it, she can smell the wool from the sweater sleeves on her shoulders.

“Comets are a gift of good luck,” said Oskar.

“Like a birthday present?” she asked.

“Better. Because it’s forever.”

There are things that siblings just know, the kinds of details spies use to confirm identities. Memories that slither beneath the tall grass of childhood.

Karl was always the smartest of the three. He taught her how to behave if she were ever arrested and to use the secret codes of communication that the Young Communists used, like pounding out the letters to the alphabet through the walls. This, at least, helped earn her the respect of her fellow prisoners. In order to survive in prison, one must reinforce the mechanisms of mutual aid as much as possible. The more you know, the more you are worth. Oskar, on the other hand, explained to her how to build one’s inner strength for resistance. How to hide weakness, act with the utmost assurance, self-confidence. So that your emotions don’t betray you. One can smell fear, he’d tell her. You have to see it coming.

She looked around with suspicion. There was a passenger in her compartment, smoking cigarette after cigarette. He was dressed in black. In order to let some air into the compartment, he opened the window and propped his arms up on the pane. A very light rain spritzed her hair and refreshed her skin. I can smell him, she thought. He’s here, at my side. You have to think faster than they do, evaporate into the air, disappear, slip out, disappear however you can, become someone else, he told her. That’s how she learned how to create characters, just like she did when she was an adolescent playing with her friend Ruth in the attic, imitating silent-film actresses, posing provocatively, holding imaginary long-stemmed cigarettes between her fingers. Asta Nielsen and Greta Garbo. Surviving is escaping toward what’s next.

After two weeks, they let her go. April 4. There was a red dahlia and an open book on the windowsill. Her family’s efforts by way of the Polish consul proved effective. But she always believed that if she was let out of there, it was because of her star.

It is not a metaphor to feel the constellations’ influence on the world, and neither is questioning a mineral’s incredible precision for always pointing toward the magnetic pole. The stars have guided cartographers and sailors for millennia, sending messages for millions of light-years. If sound waves travel through the ether, then somewhere in the galaxy there must also be the Psalms, litanies, and prayers of men floating within the stars.

Yahweh, Elohim, Siod, Brausen, whoever you are, lord of the plagues and of the oceans, ruler of chaos and of annihilated masses, master of chance and destruction, save me. Entering beneath the iron arc of the Gare de l’Est station, the train made its way to the platform. On the other side of the window, a world of passengers on their daily commute. The young woman opened her notebook and began writing.

“When you don’t have a world to go home to, one has to trust their luck. Sangfroid and a capacity to improvise. These are my weapons. I’ve been using them since I was a little girl. That’s why I’m still alive. My name is Gerta Pohorylle. I was born in Stuttgart, but I’m a Jewish citizen with a Polish passport. I’ve just arrived to Paris, I’m twenty-four years old, and I’m alive.”

Chapter Two (#u1eb7add9-d54b-5773-be81-dad2513d616a)

The doorbell rang and she stood frozen before the kitchen oven, holding her breath, with the teapot still in hand. She wasn’t expecting anyone. In the dormer window, a gray cloud squashed the rooftops along the Rue Lobineau. The glass was broken and a strip of adhesive tape, which Ruth had carefully placed, still lay over it. They had shared that apartment since she first arrived in Paris.

Gerta bit her lip until it bled a little. She thought the fear had passed, but no. That was one thing she learned. That fear, the real kind, once it has installed itself into the body, never goes away. It remains there, crouched in the form of apprehension, though there is no longer any motive, and one finds themselves safe in a city of rooftops with dormers, free of jail cells where someone can be beaten to death. It was as if there was always a step missing on the staircase. I know this sensation, she said to herself, the rhythm of her breathing returning to normal, as if the adrenaline rush had tempered her will. The fear was now splattered across the tiles of their kitchen floor where she’d spilled her tea. She recognized it in the way you recognize an old traveling companion. Always knowing their whereabouts. You there. Me here. Each in their own place. Maybe it should be like this, she thought. When the loud ring of the doorbell sounded a second time, she placed the teapot on the table in slow motion, and prepared herself to open the door.

A thin young man with a hint of fuzz over his lip tilted toward her in a kind of bow before handing her a letter. It was in a long envelope, without any official postmarks but the Refugee Help Center’s blue-and-red stamp. Her name and address were written in all caps. As she opened the flap, she noticed the blood in her temples pulsing, slowly, like the accused must feel awaiting the verdict. Guilty. Innocent. She couldn’t quite understand what the letter said. And had to read it several times until the rigidness in her muscles subsided and the expression on her face began to change like the sun when it appears from behind a cloud. It wasn’t that she smiled, but that she was now smiling on the inside. It took over all the factions of her face, not only her lips but her eyes as well: her way of looking up at the ceiling as if the wings of an angel were fluttering above. There are things that only siblings know how to say. And once they say them, the entire universe shifts, everything is put back into its place. The passage of an adventure novel read out loud by children on porch steps before dinner can contain a secret code whose meaning no one else can interpret. That’s why when Gerta read, “Beneath his eyes, bathed in moonlight, lay a fortified enclosure, from which rose two cathedrals, three palaces, and an arsenal,” she could feel the heat from the oil lamp’s flame heading up the sleeves of her blouse. It illuminated the cover illustration of a man with his hands tied, walking behind a black horse being ridden by a Tartar over snow-covered lands. That’s when she knew with all certainty that the river was the Moscow River, the walled territory was the Kremlin, and that the city was Moscow. Just as it was described in the first chapter of Michael Strogoff. And she was at ease, because she understood that Oskar and Karl were safe.

The news filled her insides with energy, a kind of vital exhilaration that she needed to express immediately. She wanted to tell Ruth, Willi, and everyone else. She looked at herself in the moon that covered the door of the wardrobe. Hands deep in pockets, hair blond and short around the face, arched eyebrows. She was studying herself in a thoughtful and careful manner, as if she had just come face-to-face with a stranger. A woman barely five feet tall, with a tiny and muscular body similar to a jockey’s. Not overly pretty, not overly smart, just another of the 25,000 refugees that arrived in Paris that year. The cuffs of her rolled-up shirtsleeves over her arms, the gray pants, bony chin. She moved closer to the mirror and saw something in her eyes, a kind of involuntary obstinacy that she didn’t know how to interpret, nor did she want to. She limited herself to taking out a lipstick from the nightstand drawer, opening her mouth, and quickly outlining her smile in a fiery red bordering on shameless.

Sometimes you can find yourself hundreds of miles from home, in an attic in the Latin Quarter, with water stains on the ceiling and pipes that sound like the foghorn of a ship, not knowing what will become of your life. Without residency papers, and with little money except for when your friends in Stuttgart can find a way of shipping some over to you. You discover the oldest reasons for uprooting, feel the same desolation in your soul as all those who have been obliged to travel the longest thousand miles of their lives and look at themselves afterward in the mirror and discover that, despite it all, a desire to be happy is written on their faces. An enthusiastic resolution, irreducible, void of cracks. Perhaps, she thought, this smile will be my only safe-conduct. In those days, the reddest lips in all of Paris.

In a hurry, she grabbed her trench coat from the coat rack and went out into the morning of the streets.

For months now, the city of the Seine was a hotbed of thoughts and opinions, a place conducive to the bravest and brightest ideas. Montparnasse cafés, open at all hours, became the center of the world for the newly arrived. Addresses were exchanged, job opportunities sought, the latest news from Germany discussed, and every now and again one could get hold of a Berlin newspaper to read. In order to get a summary of the day’s news, it was customary to go from table to table along all the stops on the route. Gerta and Ruth would often make a date to meet at Le Dôme Café’s outside patio, and it was precisely where Gerta was headed. Walking in her peculiar way, hands in the pockets of her trench coat, shoulders hunched from the cold chill as she crossed the Seine. She enjoyed that ashen light, the generous schedules, the lead gutters on the roofs, the open windows, and the world’s ideas.

But Paris was not only that. Many considered the flood of refugees a burden. “The Parisians will embrace you and then leave you shivering in the street,” Ruth liked to say, and she was right. As it was done before in Berlin, Budapest, and Vienna, the fate of European Jews was now being written on the city’s walls. While passing in front of the Austerlitz station, where she was supposed to pick up a package, Gerta saw a group of young men from the Croix-de-Feu putting up anti-Semitic posters in the station, and before she knew it, night had fallen. Again, a bitter smell of gunpowder rose to her throat. It was unexpected and different from the fear that she had experienced at home when the doorbell rang. It was more like an uncontrollable eruption. A reckless sensation that caused her to scream, coarse and loud, with a voice that did not resemble her own in the least.

“Fascistes! Fils de pute!”

The rebuke was heard loud and clear, in perfect French. That’s exactly what she said. There were five of them. All were wearing leather jackets and high boots, like cocks with their spurs. But where the hell was her self-assurance and sangfroid? She had her regrets when it was already too late. An older man exiting the door from the post office looked her up and down with disapproval. The French, always so restrained.

The tallest one of the group became defiant and began walking toward her, taking big strides. She could have found safe haven in a store, café, or in the very post office, but she didn’t. It did not occur to her. She simply changed direction, cutting the corner onto a narrow street with balconies looming above. She walked, trying not to accelerate the pace, instinctively protecting herself by holding her handbag tightly over her abdomen. Aware of the footsteps behind her. Cautious. Without turning around to look. When she had barely made it around the entire block, she was able to perfectly hear, word for word, what the individual on her trail had directed at her. A voice as cutting as a handsaw. And that’s when she started running. As fast as she could. Without caring about where she was going, as if her running had nothing to do with the threat she’d just heard but with another reason. Something inside, blocking her, as if she were being held captive in a labyrinth. And she was. Her mouth was dry, and she felt a pang of shame and humiliation heading up her esophagus, like the time when she was a child at school and her classmates poked fun at her customs. She went back to being that little girl in a white blouse and plaid skirt, forbidden to touch coins during the Sabbath. Someone who, deep down in her soul and with all her might, hated being Jewish, because it made her vulnerable. Being Jewish was a blue scarf speckled with snow in a doorway of a spice shop, her mother crouched over and keeping her head low. Now she was dodging the passersby she was brusquely meeting head-on, making them do a double-take: a young woman in such a rush could only be trying to escape herself. She took a quick left onto a passageway with gray mansard roofs and a smell of cauliflower soup that turned her stomach. And there she had no choice but to stop. At a corner, she grabbed onto a lead gutter and vomited all the tea from breakfast.

It was after twelve when she finally arrived at Le Dôme Café. Her skin moist with sweat, her hair wet and pushed back.

“What on earth happened to you?” asked Ruth.

With shoulders hunched, Gerta sank her hands into her pockets and made herself comfortable in one of the wicker chairs without responding. Or if she had, it was done in an elusive manner.

“I want to go to Chez Capoulade tonight” was all she offered. “If you want to join me, fine. If not, I’ll go alone.”

Her friend’s expression grew serious. Her eyes appeared to be busy forming opinions, jumping to their own conclusions. She knew Gerta all too well.

“Are you sure?”

“Yes.”

That could mean a number of things, thought Ruth. And one of them meant going back to the beginning. Winding up in the same place they thought they had escaped. But she kept quiet. She understood Gerta. How could she not? If she herself wanted to curl up and die each time she was at the Center for Refugees’ section 4, where she worked, and was obliged to turn the newly arrived away, to other neighborhoods, where it was known that they’d also be rejected because there was no longer a way to offer shelter and food to everyone? The largest flood of refugees had arrived at the worst moment, just as unemployment was at its highest. The majority of the French believed they’d take the bread right out of their mouths; that’s why there were more anti-Semitic protests in the streets. It was a bandwagon that had started in Germany and that was dangerously spreading everywhere.

Most of the refugees had to pass around the same 1,000-franc bill to present to the French customs authorities to prove their income and be granted entrance permission. But Gerta and Ruth were never as defenseless. Both were young and attractive, they had friends, spoke languages, and they knew what to do in order to get by.

“What you need is a real easygoing guy,” said Ruth, lighting a cigarette and making it clear she wanted to change the subject. “Maybe that way you’ll be less likely to complicate your life. Face it, Gerta, you don’t know how to be alone. You come up with the most absurd ideas.”

“I’m not alone. I have Georg.”

“Georg is too far away.”

Ruth directed her gaze at Gerta again, and this time with a look of disapproval. She always wound up playing the nurse, not because she was a few years older but because that’s how things had always been between them. It worried Ruth that Gerta would get into trouble again, and she tried her best to help Gerta avoid it, unaware that sometimes destiny switches the cards on you so that while you’re busy escaping the dog, you find yourself facing the wolf. The unexpected always arrives without any signs announcing it, in a casual manner, the same way it could simply choose to never arrive. Like a first date or a letter. They all eventually arrive. Even death arrives, but with this, you have to know how to wait.

“Today, I met a semi-crazy Hungarian,” Ruth added with a complicit wink. “He wants to photograph me. He said he needs a blonde for an advertisement series he’s working on. Imagine, some Swiss life insurance company…” she said, and then her face lit up with a smile that was part mocking, part mild vanity.

The reality was, anyone could have imagined her in one of those ads. Her face was the picture of health, rosy and framed by a blond bob parted to the left, with a patch of waves over her forehead that gave her the air of a film actress. Next to her, Gerta was undeniably a strange beauty with her gamin haircut, her severe cheekbones and slightly malicious eyes with flecks of green and yellow.

Now the two were laughing out loud, slouching in their wicker chairs. That’s what Gerta liked most about her friend: the ability to always find the funny side to things, take her out of the darkest corners of her mind.

“How much is he going to pay you?” she asked in all pragmatism, never forgetting that however appealing the idea was to them, they were still trying to survive. And it wasn’t the first time that modeling had paid a few days’ rent or at least a meal out, for them.

Ruth shook her head, as if she truly felt bad dashing her friend’s hopes like that.

“He’s one of us,” she said. “A Jew from Budapest. He doesn’t have a franc.”

“Too bad!” Gerta said, deliberately smacking her lips in a theatrical manner. “Is he at least handsome then?” she mused.

She had gone back to being the happy and frivolous girl from the tennis club in Waldau. But it was only a distant reflex. Or maybe not. Perhaps there were two women trapped inside her. The Jewish adolescent who wanted to be Greta Garbo, who adored etiquette, expensive dresses, and the classic poems she knew by heart. And the activist, tough, who dreamed of changing the world. Greta or Gerta. That very night, the latter was going to gain territory.

Chez Capoulade was located in a windowless basement on 63 Boulevard Saint-Michel. For months, leftist militants from all over Europe had started gathering there. Many of them were German and a few were from the Leipzig group, like Willi Chardack. The place was dimly lit, no brighter than a cave, and at the last minute everyone would show up: the impatient ones, the hard-core ones, the severe ones, those in favor of direct action, the ones that could be trusted. Impassioned looks, irritated gestures, lowering their voices to say that André Breton had joined the Communist Party, or to quote an editorial in Pravda, smoking cigarette after cigarette, like young privateers, quoting Marx, others Trotsky, in a strange dialect of concepts and retractions, theories and controversies. Gerta didn’t participate in the ideological discussion. She kept herself at a distance, focused within herself. Not able to grasp it all. She was there because she was Jewish and anti-Fascist, and perhaps because of a sense of pride that didn’t fit well within that language of axioms, quotes, anathemas, and dialectical and historical materialism. Her head was busy with other words, ones she heard that very morning near the Austerlitz station. Words that she was able to erase from her head for a while but that would return, with the grating sound of a handsaw, when she least expected.

“Je te connais, je sais qui tu es.”

Chapter Three (#u1eb7add9-d54b-5773-be81-dad2513d616a)

Deep in thought, she walked behind them without a single misstep. Ruth had insisted she join them, leaving her with no other choice. The filtered light beneath the trees in the Luxembourg Garden made it feel as though they were passing through a huge crystal dome; it was one of literature’s most frequented walks. Out of nowhere, Ruth ran beneath a horse-chestnut. Wearing a maroon-colored coat, she rested her back up against its trunk and smiled. Click. She had a talent for posing. From an angle, her face resembled one you would see in classic art. The sky cropped above her head like the jaw of an antelope. Click. With her coat collar lifted, she took three steps forward and then back, making a funny face to the camera, her head tilted to one side. Click. Without batting an eye, she passed right by the statues of the great masters: Flaubert, Baudelaire, Verlaine … bowing her head slightly when she came upon the bust of Chopin. Click. The sunlight scattered itself, like in a painting, over the tallest branches. Along the central path, her footsteps crunched over the gravel. The French were always so concerned with rationalizing spaces, putting up iron gates on the countryside. She ran her fingers over the surface of the pond and playfully splashed the photographer. Click.

Gerta observed and remained silent, as if this had nothing to do with her. Ultimately, she had gone only because her friend didn’t fully trust the Hungarian. Although there was something about the spectacle that fascinated her. She had never been interested in photography, but to predict the invisible selection process of the mind when framing a shot seemed to her an exercise in absolute precision. Just like hunting.

The camera was light and compact, a high-speed 35-mm Leica with a focal-plane shutter.

“I just rescued her from a pawnshop.”

The Hungarian excused himself, smiling, a cigarette hanging from the corner of his mouth. His name, André Friedmann. Black eyes, very black, like a cocker spaniel’s, a small, moon-shaped scar over his left brow, a turtleneck, a film actor’s good looks, upper lip slightly curled in an expression of disdain.

“She’s my girlfriend,” he joked, caressing the camera. “I can’t live without her.”

He had come with a Polish friend of his, David Seymour, who was also a photographer and Jewish. They called him Chim. He was thin and wore the glasses of an intellectual. It appeared as if they’d been friends a long time; both the kind who come off as uncouth, who place their glass on the table and never turn away anything that comes their way. Theirs was a friendship like Gerta and Ruth’s, to some degree, although different. It’s always different with men.

As they strolled around the Latin Quarter, they all took turns telling their stories, where they came from, how they ended up there, their refugee adventures … There was also the decorative part: Paris, September, the tall trees, the time that passes quickly when you are young or far away, or, better yet, when you’re next to the Rue du Cherche-Midi, the sound of an accordion rising like a red fish over the pavement … By then Gerta had enough time to study the situation up close. Walking alongside André as if this was the natural order of things. They kept each other’s pace, without tripping or getting in the way, though keeping their distance. Gerta took her time smoking and talking, without looking at him directly, focused solely on her analysis. She found him to be a bit conceited, handsome, ambitious, and like anyone, overly predictable at times. Seductive, without a doubt; also a tad vulgar, rough around the edges, and lacking in manners. That’s when, while crossing Canal Saint-Martin, his hand reached under her blouse to touch her waist in an invasive manner. It didn’t last more than a tenth of a second, but it was enough. Pure phosphorus. Gerta was immediately put on guard. But who the hell did this Hungarian think he was? She was brusque in her approach, looking as if she were about to say something unpleasant, her pupils radiant with green embers of rage. André just smiled a little, in a way that was simultaneously sincere and helpless. Almost shy. Like a child who has been wrongly accused. There was something in his eyes, a look of uncertainty, and it imbued him with charm. His desire to please became so evident that Gerta felt a vulnerability inside of her, like when she had been scolded as a child for something she hadn’t done and sat on the porch steps fighting back the tears. Careful, she thought. Careful. Careful.

At least the photo session was informative. André and Chim discussed photography like members of a secret sect. A new esoteric sect of Judaism, whose course of action could extend from a meeting with Trotsky in Copenhagen to a European tour with the North American comedians Laurel and Hardy, whom André had recently photographed. To Gerta, it seemed an interesting way to earn a living.

“Not really,” he said, disillusioning her. “There’s a lot of competition. Half of the refugees in Paris are photographers or aspiring to be.”

He spoke about inks for printing, movies in 35 mm, diaphragm apertures, manual dryers and tumble dryers, as if they were the keys to a whole new universe. Gerta listened, taking it all in. She was happy learning something new.

The day extended itself through plazas and into cafés. It was the perfect moment, when the words have yet to mean so much and everything transpires with levity; like André’s mannerism of cupping his fingers to protect the flame for his cigarette. Hands that were tanned and confident. Gerta’s way of walking, looking at the ground and veering a little to the left as if she was giving him the opportunity to occupy that space, smiling. Ruth was also smiling, though her smile was different, tinged with fatalism and resignation due to her friend’s leading role, as if she were thinking, Go with Little Miss Innocent. But she wasn’t serious. Just a little game of female rivalry. She walked behind them, offering the Pole some of her conversation because that was the part she’d been given to play that evening and she gave it her best. Today for you. Tomorrow for me. Chim just let her talk, somewhere between fascination and condescension. Watching her from a distance, the way certain men will look at women they consider out of reach. Each of them in their own way felt the effects of the moon that had peeked out into a corner of the sky that night. Bright, luminous, like a life full of possibilities still waiting to be revealed. Of mathematical probabilities and uncertain beginnings. Somewhere out there, in some roundabout of the night, colorful Chinese lanterns, music from a phonograph … The four of them dined in a restaurant André had recommended that had small tables with red-and-white checkered tablecloths. They ordered the most economical menu option, which consisted of rye bread, cheeses, and white wine. Chim pointed to a busy table in the back of the place, where the conversation revolved around a tall man wearing a wool hat with some kind of miner’s light attached to it.

“It’s Man Ray,” he said. “He’s always surrounded by writers. The man beside him with the tie and hatchet face is named James Joyce. A strange character. Irish. But he’s worth listening to when he’s very drunk.”

Afterward, Chim pushed his glasses up the bridge of his nose with his index finger and fell into silence again. He didn’t speak much, but when he did, whether induced by alcohol or not, he spoke about personal things, in a low voice, as if directed at his shirt collar. Gerta felt an immediate sympathy for him. He was shy and cultured, like an erudite Talmudist.

On the phonograph, Josephine Baker sang “J’ai deux amours,” which made Gerta think of avenues, narrow and black, like eels. Murmurs of conversation undulated all around, clouds of cigarette smoke, the perfect ambiance for sharing intimate feelings.

André carried the weight of the conversation. He’d let his words fall like someone who was out to narrow the gap. He spoke with vehemence, sure of himself, pausing every now and then to take a drag of his cigarette before starting up again. They’d been in Paris for more than a year, he said, trying to make their way, surviving on advertising assignments and sporadic work. Chim worked for Regard, the Communist Party’s magazine, and lived on the specific assignments he was given by different agencies. It was important to have friends. And André had them. He knew people in the Agence Centrale and at the Anglo-Continental—the Hungarian diaspora, like Hug Block, who was a real handful, but he could rely on the Hungarians. He told jokes, smiled, said whatever popped into his head. Sometimes he’d look to see what was going on in the back of the place. Then turn back and fix his eyes on Gerta again. It was as if, with all of this, he was trying to say, these are my credentials. Keeping her chin down and eyes looking up, she listened with reflective thoughts of her own as he spoke. The expression on her face wasn’t offering any easy promises, either. There was something punishing in it, with a fixed penetration, as if she were comparing or trying to distinguish what she had heard from what she was now hearing, perhaps venturing into judgments that weren’t the kindest. To André, they were surprisingly light eyes, the color of olive oil, streaked with green and violet, like those flowers in the Budapest gardens of his childhood. He continued talking with confidence. Sometimes someone from l’Association des Écrivains et Artistes Révolutionnaires would send him a wire. Refugee solidarity. One of those gatherings hosted by the association was precisely how he met Henri Cartier-Bresson, a tall and aristocratic Norman, slightly surrealist, with whom he began developing photographs in his apartment’s bidet.

“If they label you as a surrealist photographer, it’s over,” said André. His French was terrible, but he made an effort. “Nobody will offer you work. You become a real hothouse flower. But if you say you’re a press photographer, the world is yours.”

He didn’t need to be asked direct questions to tell you his life. He was extroverted, a chatterbox, effusive. To Gerta he appeared too young. She estimated he was twenty-four or twenty-five years old. In reality, he had just turned twenty and still displayed a certain naïveté that boys can have when they pretend to be heroes. He exaggerated and embellished his own exploits. But he had charisma; when he spoke, all there was room for was to listen. Like when he told the story about the rebellion against Daladier’s government. February 6, a rainy day. The Fascists had announced a colossal demonstration in front of the Palais Bourbon, and, in response, the Left organized several counterprotests of their own. It resulted in a pitched battle.

“I was able to get to Cours-la-Reine in Hug’s car and afterward continued on foot to the Place de la Concorde, trying to cross the bridge to the Assemblée Nationale.” André had begun to speak German, in which he was much more fluent. He was leaning on the edge of the table, his arms crossed. “There were more than two hundred policemen on horseback, six vans and police cordons in columns of five. It was impossible to cross. The people began surrounding a bus filled with passengers and that’s where it all began: the fire, the stone-throwing, the broken glass, a head-to-head between Fascists from the Action Française and the Jeunesses Patriotes, against us. It only worsened throughout the night. None of the streetlamps worked. The only visible light came from torches and the bonfires people began creating.” He brought his cigarette to his lips and looked straight at Gerta. He spoke with passion but with something else as well: vanity, habit, male pride. It’s something that gets into men’s heads and makes them behave like boys, right out of a scene from a western.

“It was raining and there was smoke everywhere. We knew that the Bonapartists had been able to get close to the Palais Bourbon, so we regrouped in an attempt to try and block them. But the police opened fire from the bridge. Several snipers had taken post up in the horse-chestnuts of Cours-la-Reine. It was a bloodbath: seventeen dead and more than a thousand wounded,” he said, blowing out a fast stream of cigarette smoke. “And the worst part of it all,” he added, “was not being able to take one damn photograph. There wasn’t enough light.”

Gerta continued looking at him closely, elbow at the edge of the table, chin resting in hand. Werner Thalheim had been detained that day and they ended up sending him back to Berlin, like many other comrades. The Socialists and the Communists kept brawling it out in their war of allegiances. André’s friend Willi Chardack wound up with a broken collarbone and his head cut open. All the Left Bank cafés were converted into makeshift infirmaries … but this presumptuous Hungarian considered the fact that he couldn’t take his goddamn photograph the biggest tragedy of all. Right.

Chim watched her with eyes that appeared smaller due to the thickness of his lenses, and she knew that in that very moment he was watching her think, and that perhaps he didn’t agree with her, as if behind his pupils there lived the conviction that no one has the right to judge another. What did she really know about André? Had she ever been inside his head? Had they gone to school together? Did she ever sit beside him on the back steps of his house, petting the cat until sunrise, in order not to hear his family fight because his father had thrown away an entire month’s salary in a card game? No, Gerta evidently did not know anything about his life or about Pest’s working-class neighborhoods. How was she to know? When André was seventeen years old, two corpulent individuals in derby hats went and fetched him from his home after a series of disturbances by the Lánc Bridge. At police headquarters, the commissioner, Peter Heim, broke the boy’s four ribs, never pausing to interrupt his whistling of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony throughout. His first swing went straight for the jaw, and André gave it to him with his cynical smile. The commissioner retaliated with a kick to the balls. This time, the boy didn’t smile but gave him the dirtiest look he could muster. The beating continued until he lost consciousness. He remained in a coma for several days. After two weeks, he was let go. His mother, Júlia, bought him two shirts, a jacket, a pair of mountain boots with double soles, and two pairs of baggy pants, his refugee uniform. And put him on a train when he was just seventeen. He never had a home again. What did she know about all that had happened? Chim’s eyes appeared to be asking this, as he scrutinized her reactions from behind his rounded glasses.

It was hard to imagine two teenagers less likely to wind up being friends than Chim and André. But despite the fact, they orbited one another like two celestial bodies floating through the air. They’re so different, thought Gerta. Chim spoke perfect French. He seemed serious. Like a philosopher or a chess player. From the few comments he had made, Gerta was able to deduce that he was a staunch atheist, though he still carried his Jewish karma inside like a strand of sadness, as did she. André, in contrast, did not seem interested in complicating his life with such things. It appeared he complicated his in a different way, just as men always have. It all started because of a tall man with a mustache, who began speaking to Ruth in a tone that wasn’t rude but suave. It had a certain gallantry to it, but with a good dose of alcohol. Nothing that a woman couldn’t handle on her own, without making a scene but with a simple answer that would put the Frenchy in his place. But before Ruth had time to respond, André was already getting up and throwing his chair behind him with such force that everyone in the place stopped to look. His hands slightly separated from his body, his muscles tensed.

“Easy,” said Chim, getting up and removing his glasses just in case they had to break open someone’s face.

Luckily, it wasn’t necessary. The guy, somewhat elusive and resigned, simply put up his left hand as a form of apology. An educated Frenchman, after all. Or not looking for trouble that night.

It became apparent to Gerta, however, that this was not the first time something like this had happened to them. Just from having watched him, she was certain that on more than one occasion the situation had been resolved differently. There are men who are born with an innate need to fight. It’s not likely something that they choose, but an instinct that causes them to jump at the first sign. The Hungarian was one of them, righteous, accustomed to displaying the classic weaponry of a knight errant with women. And with a dangerous inclination to engage in duels just before the last drink of the night.

Despite this, when it came to both his life and work, he was, or tried to appear, versatile and frivolous when he was lucid. He had a peculiar sense of humor. Finding it relatively easy to laugh at himself and his blunders, like when he spent in one afternoon the entire advance that the Agence Centrale had given him and had to pawn a Plaubel camera to pay the hotel. Or when he destroyed a Leica trying to use it beneath the clear waters of the Mediterranean while on assignment in Saint-Tropez for the Steinitz Brothers. The agency went bankrupt a few months later, and André joked that it was because they had hired him with his long list of disasters. His carefree way of making fun of his own stupidities made him easygoing and likable on a first impression. Typical Hungarian humor. His lazy smile expressed all that was needed, and he could even be cynical without trying too hard. Above all, the way he would shrug his shoulders, as if it made no difference whether he was photographing a war hero from the Bolshevik revolution or shooting a spread about chic vacation spots in the Riviera. Curiously, Gerta did not completely dislike such a duality. In some ways, she also enjoyed expensive perfumes and moonlit nights with champagne.

She couldn’t say then what it was that didn’t convince her about the Hungarian that eyed her so probingly, one hand holding his elbow, with a cigarette between two fingers. Without a doubt, there was something.

André Friedmann seemed to always land on his feet, like a cat. Only he could sink so deep and still maintain his boss’s confidence; or travel on a German train with a passport and no visa, casually show the inspector an ornate bill from a restaurant instead of proper documentation, and actually get away with it. One of the two: either he was very clever or he had a gift for tipping the balance in his favor. As she studied them closer, neither of the two was especially reassuring, in Gerta’s eyes.

“You know what being lucky is?” he asked, looking her straight in the face. “It’s being at a bar in Berlin just as a Nazi SS officer begins to smash a Jewish cobbler’s face, and not being the cobbler but the photographer who was able to take out his camera in time. Luck is something stuck to the bottoms of your shoes. You either have it or you don’t.”

Gerta thought about her star. I have it, she thought. But she kept it to herself.

André brushed the hair off his forehead and looked toward the back of the place again, at nothing in particular, momentarily in a daze. Sometimes he stared off into the distance, as if he were somewhere else. We all miss something, a house, the street that we played on as kids, an old pair of skis, the boots we wore to school, the book we learned to read with, the voice yelling at us from the kitchen to finish our milk, the sewing room at the back of the house, the clatter of the pedals. Homelands don’t exist. It’s an invention. What does exist is that place where we were once happy. Gerta realized that André liked to return there sometimes. He’d be talking to everyone, boasting about something, smiling, smoking, when suddenly, out of nowhere, he’d get that look in his eye, and he was far away. Very far.

“Watch, you’ll wind up sleeping with him,” Ruth predicted when they finally arrived at their doorstep at dawn.

“Not for all the money in the world,” she said.

Chapter Four (#u1eb7add9-d54b-5773-be81-dad2513d616a)

Any life, as brief as it may appear, contains plenty of misconceptions, situations that are difficult to explain, arrows that get lost in the clouds like phantom planes, and if it’s out of sight, it’s out of mind. It isn’t easy piecing together all that information. Even if it’s only for your own ears to hear. That’s what the psychoanalysts were doing with their dream studies. Quicksand, winding staircases, melting pocket watches, and things like that. But Gerta’s dreams were difficult to grasp or to try and frame. They were hers. What had her childhood been like up until then? A betrayal of those around her or else dreaming of another life?

She had found a modest paying job as a part-time secretary in the office of the émigré doctor René Spitz, a disciple of Freud. The majority of the pages in the early editions of his journals were filled with articles on dream interpretation. It was a world that wasn’t completely foreign to Gerta. When work was slow, she would avidly read all the case studies, as if wanting to uncover a secret about her own life.

Everyone tries to manage their dreams in their own way. Sometimes, when she returned home, she would sit on her bed with an old box of quince candy that she used to store her treasures in: a pair of Egyptian amber earrings, photographs, a silver medallion with the silhouette of a ship, a pen drawing of the port in Ephesus that Georg had given her their last summer together. She suddenly felt the need to grasp at those memories like straws, as if they could protect her from something. From someone. She returned to the world of Georg as one shields oneself with armor. Constantly repeating his name. She forced herself to write to him as much as she could. Made plans to go see him in Italy. Something had stirred itself up inside, irritated her, left her disconcerted, and she sought refuge in an old lover. This was her limbo, trapped somewhere between reality and fiction. Why? Ruth studied her behavior while keeping her thoughts to herself. Recognizing the same defense mechanisms she’d seen her use as a girl.

One morning, when Gerta was nine and a student at the Queen Charlotte School, her teacher punished her by not allowing her to go and play outside. She pretended that she didn’t care, as if she had always disliked having to go outdoors anyway. When Frau Hellen announced that her punishment was over, she stood her ground. For an entire year she remained indoors, reading alone at her desk, not wanting to grant the teacher the satisfaction of believing she had wounded Gerta. It wasn’t that she was proud, just different. She never dealt well with being Jewish. Inventing stories about where she came from, like Moses saved from the water, or that she was the daughter of Norwegian whalers or pirates or, based on the novel she was reading, that her brothers formed part of King Arthur’s Round Table, or that she had a star…

But there were other sorts of dreams, of course there were. There was the lake, the table covered in linen, a vase with tulips, John Reed’s book, and a pistol. That was a whole other story.

Once, as she was leaving the doctor’s office, she sensed someone walking behind her, but when she turned around to look, there was no one there, just a bunch of trees and streets. She kept walking from the Porte d’Orleans, through that area of vacant lands, and past Boulevard Jourdan, with a feeling of uneasiness at her back, as if she could hear a light squeaking of rubber soles. Every now and again a gust of wind would come, rustling up the papers and leaves, almost taking her and her scant 110 pounds with it as well. Bundled up in her coat and gray beret, she walked, eyeing the windows of the closed storefronts, seeing no one’s reflection but her own. October and its shadows of longing.

She was thin, mostly due to fatigue. She slept poorly, burdened by a flood of blurry memories. It seemed centuries had passed since she abandoned Leipzig, yet she still hadn’t found her place in this city.

“I know that one day I arrived in Paris,” she would tell René Spitz in his office one afternoon when she decided to change her medical coat for the couch. “I know that for a while I lived at other people’s expense, doing what others did, thinking what others thought.” It was true. The reoccurring feeling that bothered her most was living a life that wasn’t hers. But which was hers? She’d look at herself apprehensively in the bathroom mirror, staring at each of her features, as if at any given moment she could undergo a transformation with the fear that she’d no longer recognize herself. Until one day the change happened. She grabbed onto the sink with both hands, stuck her head beneath the faucet for a few minutes, and then shook her head to the sides like a dog in the rain. Afterward, she returned to studying herself in the mirror. Then, with the utmost care, she covered her hair, strand by strand, with red henna clay, using her fingers to comb it all back. She liked the color of dried blood.

“You look like a raccoon,” Ruth said when she came home and found Gerta underneath a pile of blankets. Her red hair made her face appear harder and thinner.

Inside her house, she never hesitated to display who she really was. But outside, at the café gatherings, she became someone else. Dividing yourself in two, that was the first rule of survival: knowing how to differentiate exterior life from interior suffering. It was something she learned to do from an early age, in the same manner she learned how to express herself well in German at school and go home afterward and speak in Yiddish. By the end of the day, all curled up in her pajamas with a book, Gerta was nothing more than a pilgrim before the walls of a foreign city. On the outside, no less, she continued being the smiling princess with green eyes and flared pants, who had managed to dazzle the entire Left Bank.

Paris was one big party. With a simple bike wheel, wine rack, and a urinal, the Dadaists were capable of converting any night into an improvised spectacle. There was smoking, an ever-increasing amount of drinking, vodka, absinthe, champagne … Every day a manifesto was signed. In favor of popular art, by the Araucanian Indians, from the cabinet of Dr. Caligari, of Japanese trees … That’s how they passed the time. The texts written one day were compared to ones written on others. The Paris carousel and Gerta giving it a whirl, turning on herself. She signed manifestos, assisted political meetings, read Man’s Fate by Malraux, bought a ticket for a trip to Italy she never took, drank far too much some nights, and, above all, saw him again. Him. André. She even dreamed of him. Though it was more of a nightmare. He pressed down on her chest, completely aroused, making it impossible for her to breathe. She woke up screaming, with a frightened look in her eyes, staring straight at the pillow. Not wanting to move or rest her head on the same part of the bed. Perhaps that dream happened later on, who knows … It’s also not that important. The fact was, she saw him again.

Of course, there’s always chance. As well as destiny. There are parties, mutual friends who are photographers, electricians, or awful poets. Besides, everyone knows how small the world is, and that in one of its corners you can fit a terrace-balcony, from which you can see the Seine, hear the voice of Josephine Baker, like a long, dark street, and on which, just as she was heading back inside, the Hungarian grabbed her by the arm to ask her:

“Is it you?”

“Well,” she responded in a dubious fashion, “not always.”

The two share a laugh as if they’ve known each other for ages.

“I didn’t recognize you,” said André. Looking both shocked and amused, with a slight wink of the left eye, as if at any moment he would lunge like a hunter over its captive. “This bright red looks good on you.”

“Perhaps,” she said, readjusting her elbows on the balcony railing. She was going to say something about the Seine, about how beautiful the river looked with the moon looming over it, when she heard him say:

“It’s not surprising that on nights like these people leap from bridges.”

“What?”

“Oh nothing, it’s just some verse,” he said.

“No, really, I didn’t hear you because of the music.”

“That sometimes I want to kill myself, Red. Get it?” He said it loud and clear this time. Taking her chin in his hand and looking her straight in the eyes, never erasing that slightly sarcastic smile from his face.

“Yes, this time I heard you, and you don’t have to yell,” she said, taking the glass from his hand without his noticing. She hadn’t realized until then that he was completely drunk.

A short time after, they were alone, walking along the riverbank, she letting him do the talking, half of her paying attention, the other half pitying him, as if he had come down with a fever or some harmless sickness that would soon pass.

What he had, which might very well pass or not, could be called deception, wounded pride, a desire to be fussed over, exhaustion … He had just returned from an assignment for Vu magazine in Saarland.

“Sarre…” he said its name in French as if he were dreaming.

But Gerta understood what he was trying to say. In other words, the League of Nations, carbon, bonjour, guten Tag … and all of that. André had told her that he had been in Saarbrücken during the last week of September, where there were posters and banners with swastikas everywhere. They walked along the river’s edge, staggering slightly, him more than her, gazing at the moon, her coat collar up, shielding her from the night fog. He had gone with a journalist friend named Gorta, who—he went on to say—with his hair long and straight like a Sioux, was more like a Dostoevsky character than a John Reed. Carbonfilled clouds in the shape of whirlwinds had snuck into all parts of the city. There are steady winds and variable winds. Ones that change direction with a force that can knock down both jockey and horse. Winds that suddenly reorient themselves, turning the hands of time counterclockwise. Winds that can blow for years. Winds of the past that live in the present.

André’s speech wasn’t very well put together. He jumped from one thing to another, without transitions, using awkward wording. But nonetheless, Gerta, for some reason, at least that night, could see through his words as if they were images: at the forefront, an image of a cyclist reading the lists the Nazis had posted on the streetlamps, workers drinking beer below an equilateral cross or passed out in the shade beside the trash containers, the filthy gray of the sky, Saarbrücken’s main street filled with banners hanging from its balconies, crowds of people leaving factories, cafés, greeting one another with a “Heil Hitler,” their arm raised, their smile casual, innocent, as if saying “Merry Christmas.”

There were still a few months left until the plebiscite’s outcome would decide if the territory would join with France or become a part of Germany. But, judging from the photos, there wasn’t a doubt. The entire carbon basin had been won over by Fascism. SARRE—WARNING—HIGH ALERT was how the report’s headline read. The images and text credited to a special correspondent by the name of Gorta. André’s name did not appear anywhere in the report. As if the photographs were not his.

“I don’t exist,” he said with hands in his coat pockets, shoulders slumped, though she spotted the vertical lines at the corners of his mouth hardening. “I’m nobody.” Now he smiled bitterly. “Just a ghost with a camera. A ghost photographing other ghosts.”

Perhaps it was right then and there that she decided to adopt that man abandoned at the edge of the Seine, with those cocker spaniel eyes. Soon after, they found themselves sitting on a wooden bench. Listening to the trees, the river. Gerta with her knees to her chest, hugging her legs. For certain women, there’s great danger in having someone place a fairy godmother’s wand in their hands. I’ll save you, she thought. I can do it. It may cost me and you might not deserve it, but I’m going to save you. There isn’t a more powerful sensation than this. Not love, piety, or desire. Though Gerta still hadn’t learned this, she was too young. That’s why, somewhere along the way, she rubbed his head with a gesture that was a cross between messing up his hair and taking his temperature.

“Don’t worry,” she said in a good fairy’s voice, poking her chin over her sweater. “The only thing you need is a manager.”

She smiled. Her teeth were small and bright, with a tiny gap separating the two front ones. It wasn’t the smile of a full-fledged woman but of a young girl—better yet, a fearless boy. An adventurous smile, the kind you put on in front of your opponent during a game. Tilting her head slightly to one side, inquisitive, teasing, as the idea ran through her head like a mouse in the floorboards above.

“I’m going to be your manager.”

Chapter Five (#u1eb7add9-d54b-5773-be81-dad2513d616a)

It was all a game at first. That shirt I like, that one I don’t. While he went into a changing room at La Samaritaine department store, she would wait for him at the entrance of the dressing area outside. Lounging with blasé entitlement on some sort of a red velvet sofa with her legs crossed, swinging one foot back and forth, until she saw him step out transformed into a fashion figure. Then, with arched eyebrows, she’d mockingly look him up and down, make him take the bullfighter’s lap of honor, scrunching her nose a bit before giving him her approval. In reality, he looked like a film star: clean-shaven, a white collared shirt and tie, polished shoes, an all-American hairdo. His eyes, on the other hand, were still that of a Gypsy. This could not be fixed.

She enjoyed the distance that he maintained around himself, a space that was necessary in order for each to occupy their place. He was never bothered by her reprimands or when she told him what to do. He began calling her “the boss.” This pact filled them both with a curious energy, as if there were a signal floating between them in the air, meeting at Le Dôme Café without having planned it, or when he passed below her window whistling without a care in the world, or, by coincidence, they both happened to be trying out a new restaurant on the very same night. Although by then, they both knew that their casual meetings were not the least bit casual.

Operation Image Makeover had its immediate results. Gerta was right. Her mother’s teachings had proven themselves once more. Being elegant will not only improve your living, it can also help you earn one. Part two of the Sarre report became André’s rite of passage. An air of success begets success.

Ruth rushed up the stairs with the breakfast baguette in one hand and the new edition of Vu magazine in the other. SARRE, PART TWO, stated the headline. ITS RESIDENTS’ OPINIONS AND WHO THEY WILL VOTE FOR. Gerta, still in pajamas, desperately waited for her in the stairwell, wearing thick socks, her eyes swollen from having just woken up. And though it was still very early, she could hardly contain herself. Pushing aside the teapot and cups, she cleared a space on the kitchen table in order to spread open the magazine as if it were a map of the world. A flashy headline, its words moving across the page in a diagonal, and the photos she had originally seen stuck to the bathroom tiles as contact sheets were now enlarged and well emphasized on the page. She inhaled the smell of fresh ink from the page, as she had with her Magic Markers when she was young. In black lettering, the photo credit read: ANDRÉ FRIEDMANN. Gerta smiled over her gray pajama top and instinctively raised her fist to the air as a sign of victory. Exactly like Joe Jacobs did when he raised Max Schmeling’s winning glove before the flashing cameras. When it comes down to it, not all boxing matches are fought inside the ring.

She liked to think of it as just a temporary alliance, nothing more. A mutual aid society for Jewish refugees. Today for you. Tomorrow for me. Besides, thought Gerta, it was not as if she had nothing to gain from it. She also received something in return. It was comforting to think like this, as if not getting too involved made her feel better. They got into the habit of waking up early to walk through the neighborhood and catch the first cart deliveries of fruit and fish to the markets. Together they’d wander through the streets with all the spices, behind the church of Saint-Séverin. The ringing of the bells passing through them both as they strolled in the fresh morning air, already charged with the smell of carbon and hemp. Foreigners in a dream city. The sky changing from indigo to gold with a soft gleam of light in the east. They were a strangelooking pair: a dark-haired guy dressed in a sweater and a blazer, and a redhead in tennis shoes and a Leica hanging from her shoulder like the bow of Diana the Huntress. She didn’t always carry an extra roll of film with her, because she didn’t want to waste a single franc, but she learned fast. Each kept to their own part of the sidewalk, without brushing up against the other, maintaining their distance. A day with beautiful light, a cigarette … That’s all it was. In just a few weeks, she learned how to use the Leica and develop film in the bathroom using a piece of red cellophane to cover the lamp. André taught her how to get close to the object in question.

“You have to be there,” he’d say, “glued to your prey, lying in wait, in order to be able to shoot at the exact moment, not a second before, not a second after.” Click.

As a result of the lessons, she became more cautious and aggressive. Though when it came time to finding the perfect composition for an image, she lacked determination. She would just stand there on some corner near Notre Dame, focusing in on an old man with a thick beard and astrakhan hat, seeing a fragment of his thin cheek in relation to the Gothic portal of the Last Judgment, and lower her camera. She could capture it all with her eyes, except when it came to the temporal. The gray cobblestoned streets and silvery skies were not of interest to her anymore. It was something else. Perhaps she started to realize that what she was holding in her hands was a weapon. The reason why those long walks began to increasingly become a place to escape oneself, her special way of peeking out into the world—still easily surprised, maybe a tad too contradictory. The way you look at things is also how you think about and confront life. More than anything, she wanted to learn and to change. It was the perfect opportunity to do so, the moment when everything was about to happen, in which life’s course could still alter itself. Many months later, just before daybreak in another country, beneath the rattling of machine guns in minusfive-degree weather, she would remember that initial moment when happiness was going out to hunt and not killing the bird.

“Photography helps my mind wander,” she wrote in her diary. “It’s like when I lie down on the roof at night and look at the stars.” It was one of her favorite things to do during their vacations in Galicia. She’d climb out of her bedroom window and up to the rooftop, position herself face-up, and carve a hole in the night sky with her eyes. Taking in the summer breeze, not thinking about anything, in the middle of complete darkness. “In Paris, there are no stars, but there are the cafés’ red lanterns. They look like new constellations created by the universe. Yesterday, while sitting at an outside table at Le Dôme, I sat in on a passionate debate about the visual power of the image between Chim, André, and that skinny Norm who joins us occasionally. He’s an interesting character, that Henri, well-educated, from a good family, but at times you sense that guilt that people from the upper class have, their conscience conflicted because of their family’s origins, and who then try to excuse themselves by being the most Leftist person at the table. André always teases him, saying that Cartier-Bresson never answers the telephone before reading the editorial in L’Humanité. But it isn’t true. Other than being quick-witted and déclassé, Henri likes to consider himself free. They argue whether a photograph should be a useful documentation or the product of an artistic quest. It seems to me that the three of them think alike, but with different wording. But I don’t fully understand.

“When I walk around the neighborhood with André, I’ll look up at a balcony and suddenly, there’s the photo: a woman hanging out her clothes to dry. It’s something that has life, the antithesis of smiling and posing. Enough with having to know where one should be looking. I’m learning. I like the Leica; it’s small and doesn’t weigh a thing. You can take up to thirty-six shots in a row without having to carry around a light stand with you everywhere. In the bathroom, we’ve set up a darkroom. I help André, writing the photo captions, typing in three languages, and every now and again I’m able to get an ad assignment for Alliance Photo. It’s not much, but it allows me to practice and get to know the inside world of journalism. The scene is not encouraging. It’s not easy to break through; you have to elbow your way in. At least André has good contacts. Ruth and I got a new job typing up handwritten screenplays for Max Ophüls. I’m also still working at René’s office on Thursday afternoons. With all of this we have enough to pay the rent, though it barely lasts us until the end of the month. But at least I don’t owe anyone money. Oh, and we have a new roommate, a parrot from Guiana, a present from André, with an orange-colored beak and a black tongue—poor thing arrived a bit beaten up. Ruth has resigned herself to teaching it French, but it still hasn’t said a single word, prefers to whistle the “Turkish March.” It can’t fly, either, although he feels at liberty to move around the house bow-legged like an old pirate. They wrote his name for us, but we decided to call him Captain Flint. What else?

“Chim gave me a photo that his friend Stein took of me and André at the Café de Flore. I hardly recognize myself. I’m wearing my beret to the side and I’m smiling, looking down as if someone were telling me a secret. André is wearing a sporty jacket and a tie and appears to have just said something funny. Things have started going better for him, and he can afford fancier clothes, although he doesn’t manage to put them together so well, you might say. He’ll look right at me, trying to detect my reaction, smiling, or barely. We look as if we were lovers. That Stein will go far with his photography. He’s good at waiting for the moment. He knows exactly when to press the shutter. Only we aren’t lovers or anything close to the sort. I have a past. There’s Georg. He writes me every week from San Gimignano. We’re born with a mapped-out route. This one, not that one. Who you dream with. Who you love. It’s one or the other. You choose without choosing. That’s how it is. Each of us travels on their own path. Besides, how do you love someone without truly knowing who they are? How do you travel that distance when there’s all that you don’t know about the other?

“Sometimes I am tempted to tell André what happened in Leipzig. He also doesn’t speak much about what he’s left behind, though he’s capable of talking for hours on end about anything else. I know that his mother’s name is Júlia and that he has a little brother whom he adores tremendously, Cornell. There have only been a few occasions in which he opens a window onto his life for me to look through. He’s extremely guarded. I, too, grow silent sometimes when I look back in time and see my father standing in the gymnasium’s doorway in Stuttgart, waiting for me to tie my shoelaces, growing a bit impatient, glancing at his watch. Then I can hear Oskar and Karl in the stands, cheering me on: ‘Go, Little Trout…’ It’s been ages since someone has called me that. It’s been ages since we went down to the river to throw stones. Cleaned the mud off our shoes with blades of grass. On nights like these, I wonder if it’s as painful for them to be remembered as it is for me to remember them. They have had to escape several times from the Führer and his decrees. Now they’re in Petrograd, with our grandparents, near the Romanian border. It’s a small Serbian village that’s never had an anti-Semitic tradition, and because of this, I worry less. I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to feel proud of being Jewish; I’d like to be more like André, who isn’t affected by this in the least. To him, it’s like being Canadian or Finnish. Never could I comprehend the Hebrew tradition of identifying with your ancestors: ‘When we were expelled from Egypt…’ Listen, I was never expelled from Egypt. For better or for worse, I can’t carry that load with me. I don’t believe in that kind of we. Organized groups are just a bunch of excuses. Only the action of an individual holds a moral meaning, at least in this life. Frankly, the other kind doesn’t convince me. It’s true that the beautiful parts we were taught as children exist. The story of Sarah, for example, or the angel who held on to Abraham’s arm, the music, the Psalms…

“I remember that on Yom Kippur, the day where it’s written that each man should forgive his neighbor, they dressed us in our best clothes. There was a photo on top of the bureau, of Karl and Oskar wearing baggy pants and new shirts. I was wearing a short dress with cherries all over it. Skinny legs. My hair was in a bun on top of my head, like a little gray cloud. Images are never forgotten. Photography’s mystery.”

Knock-knock … someone tapped lightly on the door. It had been a while since she last heard the pounding of the typewriter keys in the room next to hers. It must have been around one in the morning. When Ruth peeked in, she saw Gerta sitting with a notebook on her knees, all wrapped up in a blanket, with her third cigarette of insomnia hanging from the edge of her mouth.

“You’re still awake?”

“I was about to go to sleep.” Gerta apologized like a little girl caught doing something wrong.

“You shouldn’t keep a diary,” said Ruth, pointing to the redcovered notebook that Gerta had placed on top of her nightstand. “You never know into whose hands it may fall.” She was right: this went completely against the basic norms of keeping a low profile.

“Right…”

“Then why do you do it?”

“Don’t know,” Gerta said, shrugging. Then she put out her cigarette in a small, chipped plate. “I’m afraid of forgetting who I am.”

It was true. We all have a secret fear. A terror that’s intimate, that’s ours, differentiating us from the rest. A unique fear, precise.