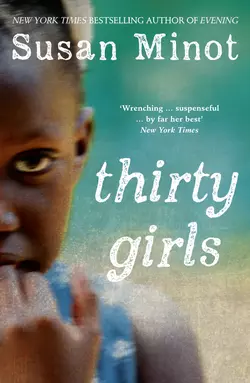

Thirty Girls

Susan Minot

Esther is a Ugandan teenager abducted by the Lord's Resistance Army and forced to witness and commit unspeakable atrocities on behalf of their leader, the despicable Joseph Kony. Her life becomes a constant struggle to survive, to escape, to find a way to live with what she has seen and done. Jane is an American journalist who has travelled to Africa, hoping to give a voice to children like Esther and to find her centre after a series of failed relationships. In unflinching prose, Minot interweaves their stories, giving us razor-sharp portraits of two extraordinary young women confronting displacement, heartbreak, and the struggle to wrest meaning from events that test them both in unimaginable ways.With mesmerising emotional intensity and stunning evocations of Africa's beauty and its horror, Minot gives us her most brilliant and ambitious novel yet.

Thirty Girls

Susan Minot

Copyright (#ulink_2202da55-5600-54d8-8f6d-51adf59bbd77)

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

www.4thestate.co.uk (http://www.4thestate.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate in 2014

First published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada

Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House Companies

A portion of this work originally appeared in different form

in Granta (winter 2012)

Copyright © 2014 by Susan Minot

Design by Kate Gaughran. Cover photographs © Claudia Dewald/Getty Images

Susan Minot asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780007550722

Ebook Edition © February 2014 ISBN: 9780007568901

Version: 2015-01-30

To beloved daughters Ava Cecily Hannah

and the brave daughters of Uganda

Contents

Cover (#u9c6f913b-e389-54f4-bf0b-a7b7a2f9cfb4)

Title Page (#u2ecb438b-427d-5176-8519-a093f6eca1f0)

Copyright (#ubd3f654d-38ae-5ccb-9544-72adb2f9e0f0)

Dedication (#u76edc0b2-6b76-5953-95bf-1aa23b1417a2)

I: THEY TOOK ALL OF US (#u14a98450-0564-5a93-865f-01a9d8da28fc)

1. Thirty Girls (#u2aa1c2d9-ed05-5c9a-b5b0-b21b84c9dad0)

II: LAUNCH (#u4a5bdf30-1763-5ca7-9858-2da4ff5a23e3)

2. Landing (#u071201bd-f96f-50cf-ad03-e25e2a58b36c)

3. Esther (#uaaa8086b-6444-52e0-88e6-90ea948890d8)

4. Taking Off (#u30ab501b-bd04-53a1-80b6-948091fdb029)

III: FIRST DAYS (#litres_trial_promo)

5. The You File (#litres_trial_promo)

6. Recreational Visits (#litres_trial_promo)

7. Independence Day (#litres_trial_promo)

IV: TO THE NORTH (#litres_trial_promo)

8. On Location (#litres_trial_promo)

9. In the Bush (#litres_trial_promo)

V: IT IS POSSIBLE (#litres_trial_promo)

10. At St. Mary’s (#litres_trial_promo)

11. Was God in Sudan? (#litres_trial_promo)

VI: REFUGE (#litres_trial_promo)

12. Hospitality in Lacor (#litres_trial_promo)

13. The You File (#litres_trial_promo)

14. What Comes Back to Me (#litres_trial_promo)

VII: GULU (#litres_trial_promo)

15. Love with Harry (#litres_trial_promo)

16. Stone Trees (#litres_trial_promo)

VIII: AIR POCKET (#litres_trial_promo)

17. The You File (#litres_trial_promo)

18. Dusty Ground (#litres_trial_promo)

IX: SPIRAL (#litres_trial_promo)

19. Where I Went (#litres_trial_promo)

20. Don’t Go (#litres_trial_promo)

X: FLIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

21. Perhaps It Is Better Not to Know Some Things (#litres_trial_promo)

22. Where I Didn’t Go (#litres_trial_promo)

23. The You File (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes and Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Susan Minot (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

I (#ulink_f8114201-63de-5c5e-8d99-2b0dadb8710d)

1 / Thirty Girls (#ulink_ad7eb859-a495-5688-8f74-2279752b9e6e)

THE NIGHT THEY TOOK the girls Sister Giulia went to bed with only the usual amount of worry and foreboding and rubbing of her knuckles. She said her extra prayer that all would stay peaceful, twisted down the rusted dial of her kerosene lamp and tucked in the loose bit of mosquito net under the mattress.

The bed was small and she took up very little of it, being a slight person barely five feet long. Indeed, seeing her asleep one might have mistaken her for one of her twelve-year-old students and not the forty-two-year-old headmistress of a boarding school that she was. Despite her position, Sister Giulia’s room was one of the smaller rooms upstairs in the main building at St. Mary’s where the sisters were housed. Sisters Alba and Fiamma shared the largest room down the hall and Sister Rosario—who simply took up more space with her file cabinets and seed catalogues—had commandeered the room with the shallow balcony overlooking the interior walled garden. But Sister Giulia didn’t mind. She was schooled in humility and it came naturally to her.

The banging appeared first in her dream.

When she opened her eyes she knew immediately it was real and as present in the dark room as her own heart beating. It entered the open window, a rhythmic banging like dull axes hitting at stone. They are at the dorms, she thought.

Then she heard a softer knocking, at her door. She was already sitting up, her bare feet feeling for the straw flip-flops on the floor. Yes? she whispered.

Sister, said a voice, and in the darkness she saw the crack at the door widen and in it the silhouetted head of the night watchman.

George, I am coming, she said, and felt for the cotton sweater on the chair beside her table. Sister, the voice said. They are here.

She stepped into the hall and met with the other nuns whispering in a shadowy cluster. At the end of the hallway one window reflected dim light from the two floodlights around the corner at the main entrance. The women moved toward it like moths. Sister Alba already had her wimple on—she was never uncovered—and Sister Giulia wondered in the lightning way of idle thoughts if Sister Alba slept in her habit and then thought of how preposterous it was to be having that thought at this moment.

Che possiamo fare? said Sister Rosario. What to do? Sister Rosario usually had an opinion of exactly what to do, but now, in a crisis, she was deferring to her superior.

We cannot fight them, Sister Giulia said, speaking in English for George.

No, no, the nuns mumbled, agreeing, even Sister Rosario.

They must be at the dormitory, someone said.

Yes, Sister Giulia said. I think this, too. Let us pray the door holds.

They listened to the banging. Now and then a voice shouted, a man’s voice.

Sister Chiara whispered, coming from the back, The door must hold.

It was bolted from the inside with a heavy crossbar. When the sisters put the girls to bed, they waited to hear the giant plank slide into place before saying good night.

Andiamo, Sister Giulia said. We must not stay here, they would find us. Let us hide in the garden and wait. What else can we do?

Everyone shuffled mouselike down the back stairs. On the ground floor they crossed the tiled hallway past the canning rooms and closed door of the storage room and into the laundry past the tables and wooden shelves. Sister Alba was breathing heavily. Sister Rosario jangled the keys, unlocking the laundry, and they stepped outside to the cement walkway bordering the sunken garden. A clothesline hung nearby with a line of pale dresses followed by a line of pale T-shirts. Dark paths divided the garden in crosses, and in between were humped tomato plants and the darker clumps of coffee leaves and white lilies bursting like trumpets. A three-quarter moon in the western sky cast a gray light over all the foliage so it looked covered in talc.

The nuns huddled against the far wall under banana trees. The wide leaves cast moonlit shadows.

The banging, it does not stop, whispered Sister Chiara. Her hand was clamped over her mouth.

They are trying very hard, Sister Alba said.

We should have moved them, Sister Rosario said. I knew it.

The headmistress replied in a calm tone. Sister, we cannot think of this now.

They’d put up the outside fence two years ago, and last year they’d been given the soldiers. Government troops came, walking around campus with guns strapped across their chests, among the bougainvillea and girls in their blue uniforms. At night some were stationed at the end of the driveway passing through the empty field, some stood at the gate near the chapel. Then, a month ago, the army had a census-taking and the soldiers were moved twenty kilometers north. Sister Giulia had pestered the captain to send the soldiers back. There was never more than a day’s warning when the rumors of an attack would reach them, so the nuns took the girls to nearby homes for the night. They will be back, the captain said. Finally, last week, the soldiers returned. The girls slept, the sisters slept. Then came the holiday on Sunday. The captain said, They will be back at the end of the day. But they didn’t return. They stayed off in the villages, getting drunk on sorghum beer.

The Jeep had been out of fuel, so Sister Giulia took the bicycle to Atoile. From Atoile someone went all the way to Loro in Kamden to see if the soldiers were there. No sign of the army. She sent a message to Salim Salee, the captain of the north, who was in Gulu. Must we close the school? she asked. No, do not close the school, he answered by radio. When she arrived back at St. Mary’s it was eight o’clock and pitch black and still nothing was settled. Sister Alba had the uneaten dinner there waiting for the soldiers. Sister Rosario had overseen the holiday celebrations and gathered the girls at the dorm for an early lights-out.

The banging had now become muted. The garden where the nuns stayed hiding was still, but the banging and shouting reached them, traveling over the quadrangle lawn then the roof of their building and down into the enclosed garden. Across the leafy paths at the entrance doors they could see George’s shadow where he’d positioned himself, holding a club.

I don’t hear any of the girls, said Sister Fiamma.

No, I have not heard them, said Sister Giulia. They could make out each other’s faces, and Sister Giulia’s eyebrows were pointed toward one another, as they often were, in a triangle of concern.

What’s burning? Sister Guarda pointed over the roof to a braid of red sparks curling upward.

It’s coming from the chapel, I think.

They wouldn’t burn the chapel.

Sister, they murder children, these people.

They heard the tinkling of glass and the banging stopped. Instead of being a relief the sound of only shouting—of orders being given—and the occasional sputtering of fire was more ominous.

I still do not hear the girls, said Sister Chiara. She said it in a hopeful way.

They waited for something to change. It seemed they waited a long time.

The shouts had dropped to a low calling back and forth, and finally the nuns heard the voices moving closer. The voices were crossing the quadrangle toward the front gates. They were nearby. The nuns’ faces were turned toward George where he stood motionless against the whitewashed wall. Sister Giulia held the crucifix on her necklace, muttering prayers.

The noise of the rebels passed. The sound grew dim. Sister Giulia stood.

Wait, Sister Alba said. We must be sure they are gone.

I can wait no longer. Sister Giulia took small steps on the shaded pathway and reached George.

Are they gone?

It is appearing so, George said. You remain here while I see it.

No, George. She followed him onto the porch’s platform. They are my girls.

He looked at her to show he did not agree, but he would not argue with the sister. Behind her he saw the pale figures of the other nuns moving across the garden like a fog. You walk behind me, he said.

George unbolted the doors of the breezeway and opened them to the gravel driveway lit by the floodlights. They looked upon a devastation.

The ground was littered with trash—burned sticks and bits of rubber and broken glass. Scattered across the grass of the quadrangle in the shadows were blankets and clothes. George and Sister Giulia stepped down, emerging like figures from a spaceship onto a new planet. In front of the chapel, the Jeep was burning with a halo of smoke. Dark smoke was also bellowing up in long tubes out of the smashed windows of the chapel. But she and George turned toward the dormitory. They could see a black gap in the side where the barred window had been. The whole frame had been ripped out and used as a ladder. That’s how they’d gotten inside.

Bits of glass glittered on the grass. There were soda cans, plastic rope, torn plastic bags. The second dormitory farther down was still dark and still. Thank the Lord, that appeared untouched. Those were the younger ones.

The girls …, Sister Giulia said. She had her hands out in front of her as if testing the silence. She saw no movement anywhere.

We must look, George said.

They stood at the gaping hole where the yanked window frame was leaning. The concrete around the frame was hacked away in chunks. One light shone from the back of the dormitory, the other bulbs had been smashed.

From the bushes they heard a soft voice: Sister.

Sister Giulia turned and bent down. Two girls were crouched in the darkness, hugging their nightshirts.

You are here, Sister Giulia said, dizzy with gratitude. She embraced the girls, feeling their thin arms, their small backs. The smaller one—it was Penelope—stayed clutching her.

You are safe, Sister Giulia said.

No, Penelope said, pressing her head against her stomach. We are not.

The other girl, Olivia Oki, rocked back and forth, holding her arm in pain.

Sister Giulia gathered them both up and steered them out of the bushes into some light. Penelope kept a tight hold on her waist. Her face was streaked with grime and her eyes glassed over.

Sister, they took all of us, Penelope said.

They took all of you?

She nodded, crying.

Sister Giulia looked at George, and his face understood. All the girls were gone. The other sisters caught up to them.

Sister Chiara embraced Penelope, lifting her. There, there, she said. Sister Fiamma was inspecting Olivia Oki’s arm and now Olivia was crying too.

They tied us together and led us away, Penelope said. She was sobbing close to Sister Chiara’s face. They came to know afterward that Penelope had been raped as she tried to run across the grass and was caught near the swing. She was ten years old.

Sister Giulia’s lips were pursed into a tighter line than usual.

George, she said, make sure the fire is out. Sister Rosario, you find out how many girls are gone. I am going to change. There is no time to lose.

No more moving tentatively, no more discovering the damage and assessing what remained. She strode past Sister Alba, who was carrying a bucket of water toward the chapel.

Sister Giulia re-entered the nuns’ quarters and took the stairs to her room. No lights were on, but it was no longer pitch black. She removed her nightdress and put on her T-shirt, then the light-gray dress with a collar. She tied on her sneakers, thin-soled ones that had been sent from Italy.

She hurried back down the stairs and across the entryway, ignoring the sounds of calamity around her and the smell of fire and oil and smoke. She went directly to her office and removed the lace doily from the safe under the table, turned the dial right, then left, and opened the thick weighty door. She groped around for the shoebox and pulled out a rolled wad of bills. She took one of the narrow paper bags they used for coffee beans and put the cash in it then put the bag in the small backpack she removed from the hook on the door. About to leave, she noticed she’d forgotten her wimple and looked around the room, like a bird looking for an insect, alert and thoughtful. She went to her desk drawer, remembering the blue scarf there. She covered her hair with the scarf, tying it at her neck, hooking it over her ears. That would have to do.

When she came out again she met with Thomas Bosco, the math teacher. Bosco, as everyone called him, was a bachelor who lived at the school and spent Christmas with the sisters and was part of the family. He stayed in a small hut off the chapel on his own. He may not have been so young, but he was dependable and they would call upon him to help jump-start the Jeep, replace a lightbulb or deliver a goat.

Bosco, she said. It has happened.

Yes, he said. I have seen it.

Sister Rosario came bustling forward with an affronted air. They have looted the chapel, she said. As usual she was making it clear she took bad news harder than anyone else.

Bosco looked at Sister Giulia’s knapsack. You are ready?

Yes. She nodded as if this had all been discussed. Let us go get our girls.

Bosco nodded. If it must be, let us go die for our girls.

And off they set.

By the time they had left the gate, crossed the open field on the dirt driveway and were walking a path leading into the bush, the sky had started to brighten. The silhouette of the trees emerged black against the luminous screen. The birds had not yet started up, but they would any minute. Bosco led the way, reminding the sister to beware of mines. The ground was still dark and now and then they came across the glint of a crushed soda can or a candy wrapper suspended in the grass. A pale shape lay off to the side, stopping Sister Giulia’s heart for a moment. Bosco bent down and picked up a small white sweater.

We are going the right way, she said. She folded the sweater and put it in her backpack, and they continued on. They did not speak of what had happened or what would happen, thinking only of finding the girls.

They came to an area of a few straw-roofed huts and asked a woman bent in the doorway, Have they passed this way? She pointed down the path. No one had telephones yet information traveled swiftly in the bush. Still, it was dangerous for anyone to report on the rebels’ location. When rebels discovered you as an informant, they would cut off your lips. A path led them to a marshy area with dry reeds sticking up like masts sunk in the still water. They waded in and immediately the water rose to their chests. Sister Giulia thought of the smaller girls and how they could have made it. Not all the children could swim.

Birds began to sing, their chirps sounding particularly sweet and clear on this terrible morning. They walked on the trampled path after wringing out their wet clothes. Sister Giulia had been in this country now for five years and still the countryside felt new and beautiful to her. Mostly it was a tangle of low brush, tight and gray in the dry season, flushing out green and leafy during the rains. An acacia tree made a scrollwork ceiling above them and on the ground small yellow flowers swam like fish among the shadows.

They met a farmer who let them know without saying anything that they were going in the right direction, and farther along they caught up with a woman carrying bound branches on her head, who stopped and indicated with serious eyes that, yes, this was the right way. People did not dare speak and it was understood.

The sun rose, yellow and bright behind them. Sister Giulia saw the figure of a person crouching in the grass at the far side of a clearing. Suddenly the figure was running toward them. It was a girl. As she came closer, they saw it was Irene. She was wearing her skirt as a shirt to cover her upper body. Sister Giulia embraced her and asked her if she was all right. Yes, Irene said, crying quietly. She was all right now.

We are going to bring back the girls, Sister Giulia told her. Irene nodded with disbelief. Sister Giulia gave her the white sweater and walked back with her a ways till they met again the woman carrying the branches and asked if Irene could go with her back to the village. The woman took her. It struck Sister Giulia how quickly one could adjust to a new way of things. You found a child, you sent her off with a stranger to safety. But then it was simply a new version of God watching over her.

Soon the sky was white. They walked for an hour, then another. By now their clothes were dry though her sneakers stayed wet. The sun was over their heads.

Far off they heard a shot and stopped, hopeful and frightened at the same time. They waited and heard nothing more. The sound had come from up ahead and they started off again with increased energy.

Sister Giulia apologized to Bosco for not having brought water. This is not important, he said.

At one point she spotted a white rectangle on the path in front of her and picked it up. It was one of the girls’ identity cards. Akello Esther, it said. She was in the 4th Class and had recently won the essay contest for a paper about her father and the effect of his accident on their family. She showed Bosco. He nodded. They had been this way.

When they heard shots again there were more of them and closer. Shouting voices floated through the bush from far off. They’d crossed a flat area and were now going up and down shallow hills. At the top of a higher hill they had a vista across a valley to a slope on the other side.

I see them, Bosco said. She stood near him and looked and could see only brown-and-green lumps with dark shadows slashed off them. She looked farther up the slope, bare of trees, and saw small bushes moving. Then she saw the girls, a line of them very close together, some with white shirts and all with dark heads. Alongside the line were gray and green figures, larger, guarding them on either side. It was too far to see the features on the faces.

For a moment she couldn’t believe her eyes. They had found them. She asked herself, What am I to do now? At the same time she set off, but now in front of Bosco. She had no plan. She prayed that God would guide her.

They took small steps down the steep path almost immediately losing sight of the opposite slope. They moved quickly, forgetting they were tired. It was past noon and they moved in and out of a dim shade. At the bottom of the hill they could look up and see the rebels with the girls. It appeared they had stopped. It was one thing to spot them far away and another to see them closer with faces and hats and guns. Then a rebel looked down and saw her approaching and called out. She thought it was in Acholi, but she couldn’t tell. She raised both hands up in the air and behind her Bosco did the same.

Other rebels were now looking over. She knew at least she would not be mistaken for an informant or an army soldier. Then she saw the girls catch sight of her. A large man walked down from higher up and stopped to watch her coming. He had yellow braid on his green shirt, a hat with a brim, and no gun. He shouted to his soldiers to allow her to approach and Sister Giulia made her way up the hill to where he waited with large arms folded. She saw the girls out of the corner of her eye, gathered now beneath a tree, and instinct told her not to look in their direction.

You are welcome, the man said. I am Captain Mariano Lagira. He did not address himself to Bosco or look at him. Sister Giulia lowered her gaze to hide her surprise at such a greeting.

She introduced herself and Thomas Bosco. I am the headmistress of St. Mary’s of Aboke, she said.

He nodded. She looked at him now and saw badly pockmarked skin and small eyes in a round face.

I have come for my girls, she said.

Captain Lagira smiled. Where were you last night?

I was not there, she said. Yes, it was a small lie. I had to take a sick nun to Lira. She slipped her backpack off and took out the brown bag. Here, I have money.

Mariano Lagira took the paper bag and looked inside. We don’t want money. He handed the bag to a rebel, who nevertheless carried it away. Follow me, he said. I will give you your girls. A rebel stepped forward and a fisted gun indicated that Bosco was to remain with him.

She felt a great lifting in her heart. Bosco hung back under the guard of a boy who looked no older than twelve. He wore a necklace of bullets and had hard eyes. She followed Lagira and passed close to some girls and began to greet them, but they remained looking down. She noticed that one rebel dressed in camouflage had a woman’s full bosom.

Captain Lagira pointed to a log with a plastic bag on it. Sit here.

She sat.

What have you there?

My rosary, she said. I am praying.

Lagira fished into the pocket of his pants and pulled out a string of brown beads. Look, he said. I pray too. They both knelt down and the rebels around them watched as the nun and the captain prayed together.

It was long past noon now and the air was still. When they finished praying, Sister Giulia dared to ask him, Will you give me my girls?

Captain Lagira looked at her. Perhaps he was thinking.

Please, she said. Let them go.

This is a decision for Kony, he said.

Kony was their leader. They called themselves the Lord’s Resistance Army, though it was never clear to her exactly what they were resisting. Museveni’s government, she supposed, though that was based in the south, and rebel activities remained limited to looting villages and kidnapping children in the north.

The captain stood. I must send a message then, he said. He had the rebels spread out batteries in the sun to be charged and they waited. She managed for a second here and there to sneak glances at the girls and saw most of their faces tipped down but a few watching her. Would you like some tea? the captain said. She could hardly answer and at that moment they heard the sound of helicopters far off.

Suddenly everyone was moving and shouting. Hide! Cover yourselves, they yelled. Sister Giulia saw people grabbing branches and the girls looked as if they were being thrashed as they were covered. She was pulled over to duck under bushes. Some of the girls had moved closer to her now. Leaves pressed on her. Then the loud helicopters were overhead, blowing dust off the ground and whipping the small leaves and loose dirt. Gunshots came firing down. One of the girls threw herself on Sister Giulia to protect her. It was Judith, the head girl.

The Ugandan army patrolled the area. Sister Giulia thought, They’re coming for the girls! But nearly immediately the helicopter swooped off and its blades hummed into the distance. They could not have known, it was just a routine strike. No one moved right away, waiting to be sure they were gone. After a pause heads lifted from the ground, their cheeks lightened by the dust. Sister Giulia saw Esther Akello with her arms over her friend Agnes Ochiti. The girl who had covered her, Judith, was wiping blood from her neck. A rebel handed Judith a bandage. She hesitated taking it. They were hitting them and then they were giving them bandages. There was no sense anywhere.

Orders were given now to move, quickly. The girls were tied to one another with a rope and walked in single file behind Sister Giulia. At least I am with my girls, she thought. She wondered if they would kill her. She wondered it distantly, not really believing it, but thinking it would happen whether she believed it or not. And if so, it was God’s will. They walked for a couple of hours. She worried that the girls were hungry and exhausted. She saw no sign they’d been given food.

At one point she was positioned to walk along beside Mariano. She had not dared ask him many of the questions she had. But since they had prayed together she felt she could ask him one. She said, Mariano Lagira, why do you take the children?

He looked down at her, with a bland face which said this was an irritating but acceptable question. To increase our family, he said, as if this were obvious. Kony wants a big family. Then he walked ahead, away from her.

After several hours they came to a wooded place with huts and round burnt areas with pots hanging from rods. It looked as if farther along there were other children, and other rebels. She saw where the girls were led and allowed to sit down.

Captain Lagira brought Sister Giulia to a hut and sat there on a stool. There was one guard with a gun who kept himself a few feet away from Lagira. This rebel wore a shirt with the sleeves cut off and a gold chain and never looked straight at Lagira, but always faced his direction. He stood behind now. During the walk they had talked about prayer and about God and she learned that Lagira’s God has some things not in common with her God, but Sister Giulia did not point this out. She thought it best to try to continue this strange friendship. Would Sister Giulia join him for tea and biscuits? Captain Lagira wanted to know.

She would not refuse. A young woman in a wrapped skirt came out from the hut, carrying a small stump for Sister Giulia to sit on. It was possible this was one of his wives, though he did not greet her. At the edge of the doorway she saw a hand and half of a face looking out. Tea, he said.

The woman went back into the hut and after some time returned with a tray and mugs and a box of English biscuits. They drank their tea. Sister Giulia was hungry but she did not eat a biscuit.

I ask you again, she said. Will you give me my girls. She didn’t phrase it as a question.

He smiled. Do not worry, I am Mariano Lagira. He put down his mug. Now you go wash. Another girl appeared, this one a little younger, about twenty, with bare feet and small pearl earrings. She silently led Sister Giulia behind the hut to a basin of water and a plastic shower bag hanging from a tree. She must have been another wife. Sister Giulia washed her hands and face. She washed her feet and cleaned the blisters she’d gotten from her wet sneakers.

She returned to Mariano. This rebel commander was now Mariano to her, as if a friend. He still sat on his stool, holding a stick and scratching in the dirt by his feet. She glanced toward the girls and saw that some of them had moved to a separate place to the side.

Mariano didn’t look up when he spoke.

There are one hundred and thirty-nine girls, he said and traced the number in the dirt.

That many, she thought, saying nothing. More than half the school.

I give you—he wrote the number by his boot as he said, one oh nine. And I—he scratched another number—keep thirty.

Sister Giulia looked toward the girls with alarm. There was a large group on the left and a smaller group on the right. While she was washing they had been divided. She knelt down in front of Mariano.

No, she said. They are my girls. Let them go and keep me instead.

Only Kony decides these things.

Then let me speak with Kony.

No one ever saw Kony. He was hidden over the border in Sudan. Maybe the government troops couldn’t reach him there. Maybe, as some thought, President Museveni did not try so hard to find him. The north was not such a priority for Museveni, and neither was the LRA. There were government troops, yes, but the LRA was not so important.

Let the girls go and take me to Kony.

You can ask him, he said and shrugged.

Did he mean it?

You can write him a note. Captain Lagira called, and a woman with a white shirt and ragged pink belt was sent to another hut, to return eventually with a pencil and piece of paper. Sister Giulia leaned the paper on her knee and wrote:

Dear Mr. Kony,

Please be so kind as to allow Captain Mariano Lagira to release the girls of Aboke.

Yours in God,

Sister Giulia de Angelis

As she wrote each letter she felt her heart sink down. Kony would never see this note.

You go write the names of the girls there, he said.

She looked at the smaller group of girls sitting in feathery shadows.

Please, Mariano, she said softly.

You do like this or you will have none of the girls, said Captain Mariano Lagira.

She left the captain and went over to the girls sitting on the hard ground in feathery shadows. She held the pencil and paper limply in her hand. The girls looked at her, each with meaning in her eyes.

She bent down to speak, Girls, be good … but she couldn’t finish her sentence.

The girls started to cry. They understood everything. An order was shouted and suddenly some rebels standing nearby were grabbing branches and hitting at the girls. One jumped on the back of Louise. She saw them slap Janet. Then the girls became quiet.

Sister Giulia didn’t know what to do. Then it seemed as if they were all talking to her at once, in low voices, whispering. No, not all. Some were just looking at her.

Please, they were saying, Sister. Take me. Jessica said, I have been hurt. Another: My two sisters died in a car accident and my mother is sick. Charlotte said, Sister, I have asthma.

Sister, I am in my period.

Sister Giulia looked back at the captain standing with his arms crossed. He was shaking his head. She said she was supposed to write their names but she was unable. Louise, the captain of the football team, took the pencil from her, and the paper, and started to write.

Akello Esther

Ochiti Agnes …

Judith … Helen … Janet, Lily, Jessica, Charlotte … Louise … Jackline …

Did I mistreat you, Sister?

No, sir.

Did I mistreat the girls?

No, sir.

So, next time I come to the school, do not run away. The captain laughed. Would the sister like more tea and biscuits? No, thank you. They bade each other goodbye. It was as if they might have been old friends.

You may go greet them before you leave, Mariano Lagira said.

Sister Giulia once again went over to the thirty girls, her thirty girls who would not be coming with her. She gave her rosary to Judith and said, Look after them. She handed Jessica her own sweater out of the backpack.

When we go you must not look at us, she said.

No, Sister, we won’t.

Then a terrible thing happened.

Catherine whispered, Sister. It’s Agnes. She has gone, just over there.

Sister Giulia saw Agnes standing back with the larger group of girls gathered to leave.

You must get her, Sister Giulia said. She couldn’t believe she was having to do this. If they see one is missing …

So Agnes was brought back. She was holding a pair of sneakers. She was told she might be endangering the others.

Okay, Agnes said. I will not try to run away again.

Sister Giulia had to make herself turn to leave.

Helen called after, Sister, you are coming back for us?

Sister Giulia left with the large group of girls. They walked away into the new freedom of the same low trees and scruffy grasses, which now had a new appearance, and left the thirty others behind. Bosco led the way and Sister Giulia walked in the middle. Some girls walked beside her and held her hand for a while. They bowed their heads when she passed near them. Arriving at a road they turned onto it. The rebels stayed off the roads. It grew dark and they kept walking. They came to a village that was familiar to some of them and stopped at two houses to spend the night. There were more than fifty girls to each house, so many lay outside, sleeping close in one another’s arms. Sister Giulia felt she was awake all night, but then somehow her eyes were opening and it was dawn.

At 5 a.m. they fetched water and continued footing it home. As the birds started up they saw they were closer to the school and found that word had been sent ahead and in little areas passed people who clapped as they went by. Sister Giulia felt some happiness in the welcome, but inside there was distress. They came finally to their own road and at last to the school drive.

Across the field Sister Giulia caught sight of the crowd of people near the gate. The parents were all there waiting. She saw the chapel blackened behind the purple bougainvillea, but the tower above still standing.

Many girls ran out to embrace their mothers who were hurrying to them. As she got close, Sister Giulia saw the parents’ faces watching, the parents still looking for their daughters. They searched the crowd. There was Jessica’s mother with her hand holding her throat. She saw Louise’s mother, Grace, ducking side to side, studying the faces of the girls. The closer they got to the gate, the more the girls were engulfed by their families and the more separated became the adults whose children were not there. These families held each other and kept their attention away from the parents whose girls had been left behind. They would not meet their gaze. In this way those parents learned their children had not made it back. When they came near Sister Giulia in all the commotion, she turned away from them. She was answering other questions. Some mothers were kneeling in front of her, some kissed her hand. She was thinking though only of the other parents and she would talk to them eventually but just now it seemed impossible to face them. Then she wondered if she’d be able to face anyone again, ever.

II (#ulink_2ac21308-4f1a-56e8-a1be-7a20a8e0a663)

Launch (#ulink_2ac21308-4f1a-56e8-a1be-7a20a8e0a663)

You have no idea where you are.

You sit among the girls. They’re in the shade, talking. It might be birdsong for all you understand or care. You think, I will never be close to anyone again.

2 / Landing (#ulink_e4bbc2c2-acc4-5496-9d1f-6e793c289ff1)

SHE STEPPED OUT of the plane and over the accordion hinge of the walkway to continue up the tunneled ramp. One always felt altered after a flight. There was the pleasant fatigue of no sleep and one’s nerves closer to the surface as if a layer of self had peeled off and gotten lost in transit. The change was only on the surface, but the surface was where one encountered the world. Her surface was ready for the new things that would happen in this new place, ready for anything different from what she’d known.

There was a soggy tobacco smell at the gate and loose rugs with long rolls no one had bothered to smooth out. She stood in a line of crumpled people holding their carry-ons and inching forward to wooden tables where clerks slowly stamped passports after a sliding look from the picture to the face.

She was finally away. She couldn’t remember the last time she’d felt the expansion, the air humid, the door opening, dawn light reflected off a hammered linoleum floor as she descended an old-fashioned staircase to the black carousel empty of baggage. There was a long row of bureaux de change with one short counter after another empty and behind them a large plate-glass window with palm trees being eaten by a white sky. Lackadaisical drivers were leaning on the hoods of their cars, half glancing around for a fare. Dark-haired men strolled in short sleeve shirts, women in thin dresses moved slowly. Everything mercifully said, This is not home.

The first time she saw him he flew.

They were in Lana’s driveway, unloading alabaster lamps she’d had copied on Biashara Street when a white Toyota truck pulled up and a young man with shoulder length hair opened the door. He leapt over the roof of the truck and landed in a bowl of dust.

Lana gave him a big greeting, embracing him as an old friend, as she embraced everyone. She stepped back to study him, hands on his shoulders. He had on a dirty white hat with a zebra band around the crown. Nice, she said, flicking the brim. Jane, come meet Harry.

Jane set down her crate. Harry, Jane, said Lana. Jane, Harry.

Cheers, Harry said in a flat tone. His chin drew in and he regarded Jane with a strange stoniness, as if she were an intruder who ought to explain herself. The impulse to explain herself was an urge Jane Wood struggled to ignore, so getting a look like that unnerved her. At least that was how she explained the unnerved feeling.

My friend from America, Lana said. She looked back and forth between them. Her bright gaze took in things quickly and let them go, just as fast.

Harry leaned forward and kissed Jane’s cheek, surprising her. Karibu, he said.

The phone rang inside the cottage and Lana dove to get it, swerving past the crates crowding the foyer.

We’re going for sundowners, she called over her shoulder. You must come.

With Lana, there was always a must.

A short time later Jane found herself crammed in the back seat of a dented station wagon driven by a paint-spattered neighbor of Lana’s named Yuri. They were headed to the top of the Ngong Hills.

The suburb of Karen flickered by. Its dirt driveways and high concrete walls topped with curling barbed wire hid the airy houses Jane had seen with their long shaded verandas and scratchy lawns. Abruptly the station wagon came to a sort of empty highway, drove on it for a while, then tilted off up a steep rutted road, laboring at a tipped angle. At the top they righted themselves over a lip and arrived at a wide sloping field of tall grass which dropped sharply to a vast smoky savannah banked in the distance with low gray hills.

Striped cloths were spread on the ground and Jane noticed the sunset behind too was striped with grimy clouds. Lana unpacked a hamper and poured vodka and orange juice from a thermos and they drank from dented silver flutes while watching the sky and leaning on each other. A warm wind blew up from the valley.

Jane knew none of them save Lana and even she was a recent acquaintance, met a year before in London on a film set Lana was decorating. If Jane was ever in Kenya, she must come visit. When the possibility actually arose, Jane found Lana and discovered how many guests and strangers took Lana up on her invitation. She was a tall striking girl with a cushioned mouth and flashing eyes. She was also a splendid recliner, as she was demonstrating now, surveying the scene before her like an Oriental odalisque, radiating enjoyment. Her pillow at the moment was a large American man named Don who appeared to be relishing his position of support despite an awkward pose requiring that he brace an arm against a nearby rock. His unwrinkled khaki pants and new white running shoes extended off the blanket into the dry grass. Lana was telling him about a project she had set up where students looked after orphaned wild animals. She must take him there tomorrow, she said, patting his red and white striped shirt, as if knowing money were packed in his chest. Yuri had brought along a dimpled girl in army boots. Jane thought she heard her say she was pre-med, which was surprising. Yuri and Harry were talking about flying. They paraglided here, at a spot farther down the escarpment where the updraft was better. The French fellow wearing a bandana was a photographer named Pierre. Pierre was also staying at Lana’s, on the couch in the living room. His low-lidded eyes regarded everything with amusement. He was snapping pictures of the army-boot girl who seemed not self-conscious in the least.

The sky dimmed and the air chilled and they packed up. They took the bumpy road back to Nairobi as it darkened. Harry sat slumped in the back seat beside Jane. She learned his last name was O’Day. He asked her what she was doing here.

What indeed, she thought. Writing a story. Getting away. She could say all that.

Seeing the world, she said.

She’s taking us to Uganda, Lana shouted back over Édith Piaf’s voice warbling out of the dashboard. Her long bare legs were draped over Don’s lap and extended out the window. After drinks everyone was feeling jolly.

Jane told Harry she was there to write a story on the children kidnapped by the LRA in northern Uganda. Lana had matter-of-factly said she’d go with her and that morning Pierre asked if he might come, too. He was in between assignments—there was no famine or war to cover at the moment—and he wanted to try shooting some video, not what he usually did. He mostly shot stills.

It’s not really my subject, she said. At all.

What’s your subject?

Desire.

It sounded totally pretentious, but what the hell.

And death.

Death should fit, he said mildly.

Death always fits. She smiled.

They both faced forward. In the front seat Lana was whispering in Don’s ear. Jane saw her tongue come out and lick it.

Things are hectic in Uganda, Harry said.

Have you been?

Not yet.

We haven’t exactly figured out how we’re getting there.

I am working on it, Lana said. I might have a possible driver.

Good, Jane said and a for a moment felt a pang of homesickness, which was odd since she did not want to be home in the least. She wanted to be as far away from back there as possible. Clutching at straws, she said.

You’ll figure it out, Harry said. You look like the kind of person who does.

She turned her squished neck to him to see if he meant it. Jane was sufficiently bewildered by what kind of person she was, so it was always arresting when someone, particularly a stranger, summed her up. His face, very close, had a sort of Aztec look to it, with flat cheeks and straight forehead and pointed chin. Jane couldn’t tell how old he was. There was no worry on his face. He was young. His expression was, if not earnest, still not cynical.

What do you do with yourself? she said.

Little of this, little of that.

She laughed. What at the moment?

I’m thinking about going to Sudan to look after some cows.

Really?

He shrugged. Maybe. Did anyone ever tell you you have a very old voice?

Voice?

The sound of it, he said. It’s nice.

Watch out! Lana screamed. The car jerked and swerved. Gasps of alarm rose from the passengers.

Not to worry, Yuri said in a calm voice, straightening the wheel which he steered with one hand. I saw the little bugger. He was trying to get hit.

Lana Eberhardt rented a cottage off the Langata Road. It was green with a rumpled roof where furry hyraxes nested and screeched through the night. In the three days that Jane had been in Nairobi, she had learned the cottage served as a crucial landing place in the constellation of the drifting populace.

Plans were made for dinner. Pierre got into a Jeep for the liquor run. He was tall and slow-moving, as if his attractiveness to women did not require he ever rush. This manner, combined with a French accent, made everything he said sound both frivolous and direct. Don drove off taking Lana in a shiny white rental car to some people called the Aspreys to see if they’d caught fish over the weekend. Their phone was out. Some time later they returned with a large cooler stocked with fish. The Aspreys themselves followed eventually, a short swarthy man and a woman in a shiny green wrapped affair with a plain face who carried herself with such flair and confidence she looked positively radiant. They had with them a beautiful freckled woman named Babette who someone said worked in an orphanage in the Kibera slum. She was dressed blandly in shorts and T-shirt and was all the more beautiful because of it. Other guests trickled in: a man named Joss Hall biting on a cigar and his wife Marina in a long Mexican skirt. There was a silent unshaven journalist whose name Jane didn’t catch. Harry O’Day had gone and not returned. Someone said he was sorting out job prospects. Pierre arrived with the liquor and a curly-headed blond woman with a fur vest and bare arms. He spent the evening leaning close to her with merry eyes. At eleven everyone finally sat down to dinner and more people appeared and wedged chairs in. A couple could be heard out in the garden shouting at each other, and Joss Hall came striding out of the shadows, with his head low, as if avoiding blows. Jane found herself glancing toward the doorway to see if that person Harry might reappear, but he did not walk in.

First they were leaving Tuesday, then Wednesday was better, then Friday. Pierre was waiting for some film that hadn’t arrived at the dukka in Karen on Friday. Lana had found them a driver, a German named Raymond, but he couldn’t leave till Sunday. No one was in a hurry; everyone had a loose time frame. They could wait.

Jane was napping on the Balinese bed in the back garden and woke to Harry’s face. He was wearing the white hat with the zebra band around it.

You want to come flying?

What?

Go on a mission. It’s only eight, nine hours’ drive.

Jane felt away from normal life, sleeping in a borrowed dress, living in a guest room. It was easy to say yes. You just went places here. You went with a stranger. Were you interested in him? Was he interested in you? You didn’t ask, even if you wondered. Jane always had so many questions rocking about in her head, it was nice to be in a place where people weren’t asking those questions. People here just did things. You just went.

She hardly knew where she was. Some nights she ended up sleeping at other people’s houses, missing a ride after the dinner party. The night before, she’d lost her key and Harry had taken her to his friend Andy’s adobe cottage, where they slept on the floor in front of a fireplace. Another paragliding guy with a beard was on the couch. Jane had not slept much, feeling Harry’s proximity.

What do I need to bring?

Nothing, he said.

But she went to the guest room and put some clothes in a bag. She peeled bills from a wad of cash and hid the rest with her passport behind some books. Her journal fell open and pictures fanned out on the floor. Harry picked them up and handed them back to her, sitting patiently while she wrote Lana a note saying she’d be back tomorrow or the next day. She took a white Ethiopian wrap Lana had lent her and got into Harry’s truck with him.

They drove through the Nairobi traffic with the Ngongs’ slate-gray peaks zigzagging above and headed west, up hills feathered with crevasses and past scribbled bushes and thin trees, and lit out on a spine-slamming potholed road.

They passed through the crossroad din of Narok, rattling with muffler-less cars. Yellow storefronts sat in a line beside blue storefronts. There were many groceries: Deep Grocery, Angel Food, Ice Me. People walked among goats or sat on piled tires; dust rose up. Then the colorful blur passed and suddenly the open windows framed a parched beige landscape smelling of smoke and dry grass. After long stretches of uninterrupted brush and flat dirt they’d find a scattering of huts with people on the side of the road, usually children, turning with slow, aimed faces to watch the vehicle pass.

Harry didn’t talk much, but after eight hours in a car she did learn some things.

The main thing for Harry was flying. Work was what you did to pick up a few shillings between missions. He’d had a few jobs, relief work in the north, construction work at a safari camp in Malawi. At home he could usually count on being hired by a German chap who put up electric fences for private houses in Langata. He spent a while too with a bloke trying to save wild dogs in the Tsavo desert. That had been a cool job, he said, nodding.

But mainly he flew. When he first started paragliding he would drive everywhere in the truck till he realized a motorcycle was better for the out-of-the-way places. And out-of-the-way places were the point. The whole continent of Africa was open to him, he’d only scratched the surface. A recent trip to Namibia over the baked desert clay was awesome. Sometimes he went with a mate, usually Andy, but he’d also go alone. His parachute folded up into a rucksack which he strapped to his bike.

She asked him questions; he answered them.

He’d go for days or weeks. Alone, he ate raw couscous, too lazy to cook. By the end of a trip he’d be living on vitamin pills and returned with burnt skin, weighing pounds lighter. His motorcycle got stuck in muddy swamps. Once, deep sand in the desert sputtered out the motor. There was the time he broke his collarbone landing on rocks which made the two-day drive home not so fun. Another time he dislocated his shoulder, but Andy was there and snapped it back.

Many places that he flew he could look in every direction and see no sign of people. Now and then a little cluster of huts was there blending into the brown earth or a thin wire of smoke rose out of the trees. But wildlife was everywhere. Elephants looked like tiny gray chips. Herds of gazelles were a swarm of flies on pale ground when you saw them from above. He looked down on the back of eagles with their stiff wings unflapping as he followed them down the thermal from behind.

Then Harry had a question. Who’s the man in the blue shirt? he said.

Jane looked at the unchanging landscape, thinking he meant someone on the road. Where?

In your book that fell out.

Oh. That’s my ex-husband.

You were married?

I was.

What happened?

Got divorced? she said brightly. Then, Got divorced. She felt him waiting for more. It was hard for Jane to stay silent if she felt someone wanted more. Two years ago, she said.

Harry rubbed his teeth with his tongue. You still love him? She looked at him, surprised. You keep his picture.

He’s dead.

He looked at her to see if this was true. Really?

Yup.

Whoa, he said under his breath. What happened?

OD.

That’s hectic.

Happens when you’re an addict, she said.

Yes, he said.

No, she agreed. It was bad.

They drove in silence.

How long were you married for?

Three years, but we were together for eight. He was in a clean period when we got we married. She laughed. As if that mattered.

Harry watched the road, tilting his head to show he was listening.

We weren’t together when he died, she said. But it was still … She didn’t finish.

What was his name? Harry said.

Jake.

Harry appeared thoughtful.

That was, Jane thought, all she was going to say about Jake. At least at the moment. Maybe she’d say more later. Some other time, when she knew him better. She might say more, if she thought he cared. But why would he want to know, really, was her first thought. And did she really want to tell him all that? Jake slipping back only a week after the little wedding, the wrenching final break, how she didn’t go to the funeral because the new girlfriend didn’t want her there. She’d had a hard enough time explaining it to herself without having to describe it to someone else. How do you describe hearing your husband say, I think I made a terrible mistake? And what more can you add about yourself if after hearing this you find that no vow of loyalty could have bound you more fiercely to him than this expression of rejection?

What about you? she said to Harry. You have a girlfriend?

His shoulders rose in a slow shrug. Sometimes, he said. Sort of. His face was placid.

Does she have a name?

He turned and smiled at Jane. Nope.

Open aluminum gates marked the entrance to the Massai Mara and a soft red road led them down a steep hill to the game reserve. They drove onto a flat green plain striped with thin shadows. In the distance a wall-like cliff rose on the western side.

They drove along the eastern edge among leafy trees. There she is, Harry said. To the south an escarpment curled like a giant wave about to break, dwindling off to the west and ending in a hazy bluff.

Harry pointed to some thornbushes which on closer examination turned out to be zebra sitting with ears up in a striped shade. Jane stared fascinated, feeling she was in a storybook, though she was to learn that zebra were not particularly impressive to Africans. Elephant, on the other hand, were by all standards worth driving off track for, as Harry did when he spotted a small herd low in a riverbank. The truck wove its tires through lumpy grasses and stopped, motor off and ticking, giving them a clear view of enormous wrinkled creatures, legs darkened by mud, swaying and bumping against one another. One lifted a trunk like a whip in slow motion and sprayed water. When a large female started flapping her ears, staring directly at the truck and making a throaty trumpet sound, Harry knew to start the engine and back up.

They passed the entrance to a safari camp and its wooden sign hanging on rope with the yellow recessed words Kichwa Tembo. Elephant Head. There were a number of commercial camps in the Mara, but Harry was taking her to a private house, owned by an anthropologist who’d married her Maasai translator and so had claims on the land. At the southern corner of the plain the red road tilted up, turning pale and chunky with white rocks. They lurched up a short vertical hill then hugged the side in diagonal slashes of switchbacks. Harry gripped the steering wheel as if he were wrestling something wild. They passed Maasai encampments he told her were called bomas, circular walls of tangled branches containing small huts and cattle which had to be protected from wildlife. On a day’s notice the boma would be dismantled and reassembled somewhere else where there was fresh grass.

Are we close? she said. But she wasn’t impatient. She felt happy and free. The land was majestic and riding beside him she had the feeling she was where she ought to be. It was not a feeling Jane had often.

Just up here, Harry said, and Jane didn’t care if they ever got there or ever stopped.

The white road ran along a naturally terraced area of the escarpment. Down to the right was a tunnel of greenery inside which flowed the Mara River. There was no road at all when Harry turned right down a slope of flattened grass strewn with hulking boulders at the end of which sat a stone house with a tin roof.

They got out. The air was loud with the sound of water rushing by in the river. They went to a door surrounded by a wrought-iron cage with a large padlock on it. No one appeared to be home. Jane sat for a moment in a chair left outside at a green painted table. The river surged by below, the color of café au lait, battering low branches that bounced against the white waves. Above the river a woolly ridge dark as a rain forest rose up against a yellowish sky. It was late afternoon. On the table a wineglass held a coin of red liquid and a dish had the last bits of a tart crust. Harry was digging around in the back of the truck, hauling out the backpack.

They walked straight up, first in the shade then passing the line into the sun. Jane followed Harry’s large backpack. They came to a narrow footpath. Halfway up they passed a thin woman, chest wrapped in a plaid red and blue shuka, walking down. Her head was shaved and her long earlobes hung with loops and beads. She was barefoot, probably around eighty, walking without hesitation. Jambo, they said and she nodded, passing by.

It didn’t take long to reach the top, and it felt as if they’d gone higher when they did. Soft wind blew and looking over the valley Jane had the sensation she’d never been able to see so far. Perhaps it was true.

Harry dumped out the sack and harness. He took off his shirt and put it back in the sack. As he unrolled the parachute it swelled out like foam. He shook it, then stepped into the harness attached to the thin ropes. His helmet was round and white, making his head look too big for his body. He stood a short distance from the edge with feet planted apart. Past the tall grass at the edge, the plain stretched miles below, brownish green but bleached of color. Behind Harry on the ground the chute flowed out like a wedding train. He pulled at it to free it from twigs and thorns, shaking at a dozen thin lines which all branched out into shorter lines attached to the chute. The likelihood of a tangle seemed immense. A harness of black straps fit over his shoulders and chest and wrapped around his thighs, arranged so that airborne he’d be seated. He stood for a while, staring out, listening. He looked at the clouds, gazing overhead, waiting for a gust. A white mist blew over them, dimming the sun and dampening Jane’s face, a low cloud whitening everything. The wind puffed the sheet behind him. His arm kept reaching back to fluff the light fabric, while he stayed face-forward. Wind filled the sail, lifting it, seeming to push him forward. He took a few quick steps. Jane was aware of the absence of the motor roar that usually accompanies a liftoff as Harry stepped off the edge onto air.

The fabric snapped behind him like a boat sail filling with a gust and he shot backward up over her head. He hovered there for a moment then swung back out over the escarpment drop. Jane heard a satisfied sort of whoop. She watched him, holding her hair away from her eyes, as his feet dangled past her and she learned that the person remaining on the ground could also receive a lifting sensation at takeoff. That is, she did. The flying was totally silent. In the air, Harry had said, you didn’t hear the sound of wind because you were moving at its speed. You were the wind.

The thermals wound in the invisible shape of corkscrews. She watched his figure soar out over the giant bowl of the world, soon catching the spiral in a wide slow circle as if up a spiral staircase. His sail was long and narrow, puckered like a giant earthworm. Very quickly his figure was quite far away.

To the west clouds were stacked with sculptural definition beside the lowering sun. The clouds, the clouds, she thought. Piled and beautiful, they were both indifferent and inviting. They had that paradox of nature you saw also in the sea, a thing appearing eternal even as it changed every second. Harry was now a miniature action figure under a sideways parenthesis. For a while longer she watched him sail, feeling weightless herself, floating by proxy. She didn’t need to fly to feel she was floating. She had a knack for channeling other people’s experiences. You left yourself behind and there was relief.

Harry was a white dot.

The vastness of the savannah below reminded her how tiny a speck she was too and yet at the same time offered her the illusion that she could reach across and touch the bluff miles away. Warm wind blew in small gusts against her and the dot seemed to pull her toward it into the sky. In dreams when she was flying she could never make out exactly how it was working. She swooped through doorways, looped over trees, but felt that at any moment the miracle might stop and down she’d plummet. She’d think in the dream, I better concentrate on staying up, but that wasn’t necessary. You just stayed up. You didn’t know what was keeping you up. It wasn’t in your control. It just happened. Like life. She thought how in her dreams she too flew in loops the way Harry was now, riding the thermals, following the shape of DNA.

A white sun perched on the western ridge. When it dropped behind, the light would go. Harry had told her to walk down before dark. Night-time was the kingdom of the animals. You didn’t want to be out there then with them. She entered into the shadow sloped across the hill, taking steps sideways, sliding a little, going down and yet still having the buoyant feeling of drifting over a vast plain. What had taken them thirty minutes to climb took her ten minutes to descend.

On the way down she kept the corrugated roof of the house in sight with the white truck beside it, the lightest thing in the gathering dusk. Darker vehicles were also parked there now. She reached the bottom and walked quickly on a dark road. When she saw a bright little fire going in front of the house it showed how dark it was. Closer she saw piled branches crackling inside a circle of stones. In front of the fire was the round table where two men and a woman were sitting with bottles and a crossed pair of army boots. She was greeted by the people with no surprise at seeing a strange woman emerge out of the dark. A fellow with a thin ponytail stood up and offered her his chair of twisted saplings. Karibu, he said. It was Andy. She sat.

Tusker? Jane was handed a bottle and introduced. The fire was warm on her legs.

The girl named Julia worked at a nearby tourist camp. The one with the boots on the table was Cyril from England.

They asked her where she was from and she asked them and soon they were talking about the baby leopard that had fallen through a torn patch in the roof last week. It landed on Annabel’s mother in her bed. Inside the stone house Jane could see more people crossing back and forth making dinner.

It was looking for food, said the girl, her white teeth glowing in the dusk. She wore a safari shirt and a short skirt. But it did freak her mum out a bit.

A bit, Jane said.

What did she do with it? said the fellow with the boots.

Shooed it out the window, said the girl, blowing cigarette smoke toward the fire. Poor thing didn’t want to be there either.

Maybe I better go get Harry, Andy said.

He’s not back? Jane said. Beyond the fire was blackness and the rushing of the river.

Well, Joss went to meet the plane, he said vaguely. I’ll go see. He gently moved off to be engulfed by blackness after which they heard the sputtering of a motor.

Inside Jane met their hostess. Annabel wore a ripped green evening gown and had red hair arranged in a loose triangle on her head. A long table was being set among rocks and feathers and bones. Jane was given the job of picking wax from Moroccan candlesticks and pouring salt into oyster shells, fossils from the river.

Hours later the table was crowded with plates of grilled meat and glistening bottles and candle flames. There were stories of men falling out of the sky, of cars breaking down crossing streams, of mothers running off with young lovers. A steady rain drummed on the roof above them. Jane sat beside a man in a polo shirt who was pointing out the absurdity of monogamy. Look at the animals, he said. Need I say more?

Annabel stood, pouring wine into everyone’s glasses, her smile showing wine-stained teeth.

You have someone back home? he asked her.

Kind of, she lied. She thought of the painter she’d liked lately though nothing had gone on between them.

Don’t let a man put you in a cage, he said. Ever.

Julia mentioned that it was her birthday as if she’d just remembered it, and everyone shouted and gave her toasts. Some time later Annabel handed her a present wrapped in a banana leaf and tied with a brown Hermès ribbon.

Much later Jane found herself outside in a pitch dark pouring with rain beside strangers pushing a car stuck in the muddy hillside. She gripped the door handle, her bare feet sunk in mud. The car would rev in a great burst, roll forward an inch then rock back down, inert. Try it again! they yelled. Another rev, another group shove, and it wasn’t budging an inch. People shouted, insulting each other, laughing. The rain was loud, slapping on the slick grass, but still Jane could hear the low constant roar of the river. The jaunty thump of music played from a tape inside where lanterns shone from yellow windows, casting dim smudges. Otherwise everything was black.

Jane could hardly see her hands. The shirt of the person beside her showed because it was light-colored. They kept heaving and shoving against the car. Suddenly it jerked forward, pulling out from everyone. Jane stumbled, managing somehow not to fall. A headless figure with a white shirt slid by as if on skis and grabbed her upper arm. Harry pulled her along so she skated at his side for a moment on the slick ground before they both toppled over into spattering mud. His arms were cupped around her, and they rolled in this clasp down the slope, somersaulting. The face was close and dark with darker spots where the eyes were and when its mouth came near she kissed it, kissing water and rain and bits of grit on his lips, thinking, I’m kissing Harry. She felt his chest warm through his soaked shirt. In her mind were images of the dinner and the faces around the candlelit table, of driving that day on the red snaking road, then of Harry lifting up into the orange air over her. They’d had a lot of wine and her thinking was far off and hazy but one thought did come—this is the way you found a person, crashing into him in the dark, without decision, without knowing where you were going—and even in that abandon she still managed to locate little worn areas of worry pulsing, but with no words to them. Worry didn’t stand a chance against this sliding and this person she was holding. The slope of the hill evened out and they stopped rolling and kept kissing and she had a laugh in the back of her throat with the thought, I’m kissing Harry. She kept thinking it as worry faded. She saw his hands on the steering wheel, his profile and his placid masklike face.

Wet hair plastered her forehead and his cheeks and their bodies pressed against the length of each other on the wet ground. She felt triply alive, as if delivered from an austere place where it was now apparent she’d been for a long time. How had she stayed there so long? Now she had his warm arms and her back was chilled. The rain kept streaming over them and behind in the deeper darkness the sound of the river was rushing and thundering. Harry was a close new thing which she knew very little about and yet at this moment found it seemed to offer her everything.

3 / Esther (#ulink_54fbf6fa-aa93-5faa-8f1a-873198af2c40)

I SIT AMONG the girls in the shade of a tree not so far above my head. It is peaceful with their voices in the air, talking quietly. It might be birdsong for all I understand or care.

I think, I will never be close to anyone again.

We are just now supposed to be drawing pictures of things we would like to forget. You can see why this is strange. We must think, in order to draw them, about those terrible things we would rather remove from our minds. We are told that drawing such things will help us remove them.

Instead I am drawing the tree past the work shed toward the field. It has a curved trunk and resembles a woman twisting to look over her shoulder.

Today I woke with a pressure on my eyes, pulling my forehead. I thought, Perhaps I am getting a cold. Maybe I am.

My mind is uneasy. Since being away, I am used to my thoughts being disrupted. They have cracks in them. I remember in a soft way, as in the distance, how it was to be whole. Nothing. It was like nothing. You just had wholeness, you did not feel it. I would not have known it was there if I had not become as I am now. It has offered me a perspective. It is interesting how one can understand a way that one was only after one is another way.

Beside me the girls’ heads are bent close to the paper. They use ballpoint pens and pencils which are better if you want to erase. Red pencils are often used for the blood and the bullets. At night the bullets were red.

Holly is beside me. She leans on a cardboard cracker box. She has drawn a house with a thatched roof and doorway, her house. Soon she will add men with pangas, a chair on fire, and her lute broken on the ground. She was practicing music when she was taken. Holly’s from the country near Ongoko, not from the town like me. I am from Lira town, which is not far, just a day’s walk.

Past the picnic bench near the shop the boys are together there drawing. I see that one, Simon, with them. His back is to me with his bad leg straight out. When he was shot the bullet was near the bone so his knee is not so good. He swings his foot around when he walks instead of stepping straight. The scar looks like a crack in a window with jagged lines coming out from a shiny pink center against his dark skin. The scars on us are not straight.

Simon is good at drawing so his drawings are tacked up in bicycle repair. One of a car on fire with flames smaller than the smoke, one of a boy with his arm cut off and drips of blood making a puddle. He’s skillful at details, doing three shades of camouflage with one lead pencil. His AK-47s shoot clouds and the soldiers have bouffant hairdos and sideburns as in cartoons. Everyone draws them that way, even though they do not so much look like that. They look like anyone.

A high chain fence follows two sides of the property here and there’s a wooden fence with pieces fallen out of it along the driveway. The playing field has no fence, but one side goes beside a marsh. We are not fenced in. Here is not a prison and still we are not permitted to leave.

I am not so good at drawing. I would rather look at a thing made in nature. I do not finish drawing that tree.

Our camp is called Kiryandongo Rehabilitation Center and we are, during the dry season, a dusty circle cleared in the middle of tangled bush a little ways off the Gulu Road. There are some huts and the office of two sheds connected where Charles our head counselor has an office. The kitchen has a small roof and all sides open to the fire pit and brick oven and there you see Francis cooking. Chickens peck around. We had chickens and when I was small I liked to hold them as pets. They were nervous, but if you keep patient they will calm down and stay in your lap even if their eyes are startled.

We have a parking area for cars. One belongs to Charles and the truck fetches food and supplies. The van is to transport children, but it is broken at this time and has not been used since I have been here.

In the work shed is a shop for making instruments and building chairs and repairing bicycles. Behind in the trees is a large white tent that came from Norway where the boys sleep. The ventilation is not so good and, having sixty boys inside, the air is unmoving and hot. The girls sleep in dormitories with bunk beds so close you can reach over and touch the girl next to you.

Holly is in the upper bunk beside me. She has decorated her area. From the ceiling strings dangle empty boxes of Close-Up toothpaste or fortified protein, an eye-drop bottle, a box of Band-Aids. I have no decoration. Underneath Holly is May, who is very pregnant, due in a month. Her parents do not accept the child coming and have not visited May.

At Kiryandongo we are all united by a thing that also divides us from others. We look at each other and know what we have been through. We also look away for the same reason.

Since my return I meet new challenges of the mind. I have decided to forget everything that happened to me there and so look forward to the remainder of my life. I am not so old, nearly sixteen. My life could still be long.

Before, my life was nothing to speak of. You would not have heard of it. Now, they tell us it is important to tell our story. They have us draw to tell it, but I am not so good at drawing.

We studied the Greeks in school and they had people called rhapsodes who memorized long stories and recited them the way you would a song. The long poems were epics. At banquets or by pools people would sit eating grapes and drinking from goblets and listen to the rhapsodes sing. It was not a song with music, but the rhapsodes still sang. They sang of heroes and of journeys.

When they ask us to speak, I cannot find the words. What I have inside is for me to look at alone. Who else can know it? Not anyone. I cannot say it out loud. How can one tell a story so full of shame?

I listen to the others talk and understand how they struggle. We knew the same things. I stay apart to make peace with it inside myself, if I am able. With the rebels I learned that inside is where it most matters in any case.

I am one of the abducted children. Did I tell you my name? I am Esther Akello.

I have been back about two weeks. The days are strange, I am not used to the peace. I am not used to waking without someone hitting my feet. The first week I slept a great deal and woke with swollen eyes, which in the mirror had dark hoops under them. There is a heaviness in me where gladness does not reach. I know there should be gladness that I have returned. I am free, but gladness does not come to me.

The boys finish their drawings then get up and kick around a ball on the dusty field. Boys forever like to play with balls. This is better than hitting each other. Simon is running with his bad leg. Charles claps his hands, getting them to go faster.

Here at Kiryandongo they always want you to join in. They say, Come on, Esther, I know you can run. Come on. Get up off your seat.

I prefer to sit. When the ants come I brush them away. If they keep coming back to me I pinch them between my fingers. Maybe I will get up when I am ready. Maybe I will not. I hate everyone.

As I said, my town is Lira. At night Lira is quiet and in the day it is not so loud either. We have a pink brick bank and a yellow brick post office and many churches, some with steeples, though most with simply a roof. Goats walk about. The main street is paved from the turnaround at one end and tilts upward past groceries and other shops selling batteries and Walkmans and clothes and stationery to the other end of town where the road becomes dirt and paths squiggle into the countryside. During the dry season the dirt is red and dusty, in the wet season it grows darker and stains our feet like rust.