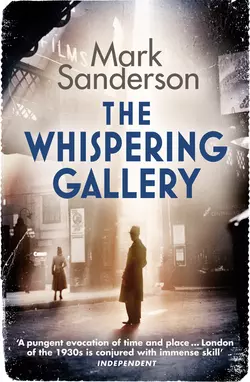

The Whispering Gallery

Mark Sanderson

Mark Sanderson does for the 30s what Jake Arnott did for 60s London – vividly revealing its hidden underworld in this follow up to Snow HillOn a sweltering day in July 1937, reporter John Steadman is in London’s St Paul’s Cathedral waiting for his girlfriend … But romance is pushed aside when he witnesses a man falling to his death from the Whispering Gallery, killing a priest in the process. Did he jump or was he pushed?Two days later Johnny receives the first of a series of grim packages at the offices of his newspaper, the Daily News. Each contains the body part of a woman and an enigmatic note, one of which says that he will be the murderer’s final victim.To catch a killer, Johnny must set himself up as bait – with police and a fascinated public looking on. But he still has to uncover the tragic truth behind the double-death in the cathedral…

The Whispering Gallery

MARK SANDERSON

Dedication (#ulink_88d3ce14-8744-524b-9f8b-0dde21f3a456)

To Miriam, without whom . . .

Epigraph (#ulink_26e21d33-6855-5e4e-bf6b-f35addbdaca8)

Let us be grateful to the mirror for revealing to us our appearance only.

Erewhon, Samuel Butler

Contents

Cover (#udf0c8d6c-2757-5e66-b402-fd1a5c5fdf24)

Title Page (#uaf5b3bd2-5c23-5086-8c91-1ad5b7748cd1)

Dedication

Epigraph

Foreword

Part One - Wardrobe Place

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Part Two - Dark House Lane

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Part Three - Sans Walk

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Bibliography

About the Author

By the same author

Copyright

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Foreword (#ulink_e8f6c0b1-a978-5505-97b7-c98f9fb4989c)

It made no difference whether or not she opened her eyes. She was smothered in complete darkness. It was impossible to distinguish night from day.

How long had she been here? And where was here? It had to be somewhere underground. Her voice-box had cracked from screaming for the help that refused to come. She longed for the relief that unconsciousness lent her.

The chain attached to the tight spiked collar round her neck – What had he called it? A throat-catcher? – clanked as she tried once again to pull it off the bare brick wall. She was so thirsty she had resorted to licking the damp stone. The tip of her parched tongue was already torn. The collar prevented her getting any closer to the precious moisture.

She had broken all her nails – her lovely, long nails that she manicured daily – scratching in the search for a way out.

Hunger gnawed her insides. She was empty now: the stench of her piss and shit filled her nostrils. She could not stop shivering. The only thing in her favour was that it was July: had it been winter she would have already frozen to death.

She blushed at her nakedness and immediately reproached herself. What did it matter when she was about to die? And she had no doubt that she would soon be dead. He had told her as much on his last visit as he shortened the chain. Tears sprang to her eyes once more. She tried to catch them with her tongue. They felt shockingly hot on her cold, filthy skin.

The silence was shattered by the clang of a metal door. She shrank back into a corner and began to shake uncontrollably. A candle-flame pin-pricked the darkness. He was coming again. So far he had not touched her but he had made it quite plain what he eventually intended to do.

She screwed her eyes shut, terrified at what she might see. He would blindfold her and, to begin with, say nothing at all as he watched her for what seemed like hours. She could feel his eyes creeping over her flesh, lingering between her legs. It was only then that the whispering would begin.

Part One Wardrobe Place (#ulink_76e3fd44-b0a7-54c9-8717-90cddfb07bc4)

Chapter One (#ulink_dacdd4df-1440-5580-8508-e12bd889658e)

Saturday, 3rd July 1937, 2.30 p.m.

He was going to take the plunge. It had been almost eight months now and he loved her more than any other girl in the world.

Even though the remorseless sun came slanting through the clear glass, it was cool in the vast interior of St Paul’s. Johnny, impatient as ever, strolled down the nave, dodged gawping tourists, and took a seat beneath the magnificent dome which, thanks to the exhibition in St Dunstan’s Chapel, he had already learned was actually three in one: the outer dome of fluted lead and stone that could be seen from all over London; a brick spire that held up the lantern at the very top of the cathedral; and, sixty feet below the outer one, an internal dome decorated with scenes from the life of St Paul in grisaille and gold. Biblical history had never been one of his strong suits – or interests – at school, but Johnny recognised the shipwreck on Malta, the conversion of the gaoler and the Ephesians burning books – just like the Nazis today. Nothing changed.

What little remained of his faith had been buried along with his mother after her early, excruciating, death from cancer. However, he was not in St Paul’s to pray but to propose marriage to Stella, the green-eyed, glossy-haired temptress he had met in The Cock, her father’s pub in Smithfield, back in December. They had been seeing more and more of each other since Christmas – and Johnny had been falling deeper and deeper in love. Although she still sometimes helped out behind the bar, Stella was now a fully qualified secretary who worked at C. Hoare & Co., a private bank in Fleet Street – which just happened to be a minute’s walk away from the Daily News where Johnny was a crime reporter.

Johnny checked that his mother’s engagement ring was still safely tucked in the inside pocket of his jacket – his father had died in the battle of Passchendaele when Johnny was three – and looked up to the Whispering Gallery where he intended to make his proposal. The acoustics were such that words whispered behind a hand travelled round the wall of the dome and into any ear pressed against the stone. There were only four people up there at present. One of them, a beanpole of a man, gaunt and unshaven, stood directly above the keystone of an arch decorated with a cherub behind a pair of crossed swords. He leaned over the ornate railings and watched those milling around a hundred feet below.

Johnny got to his feet. He was beginning to feel really nervous now. Stella wasn’t due for at least another ten minutes and she always made a point of being eight minutes late: “It makes you all the happier to see me.” She didn’t seem to understand that this was impossible.

“She can only say no,” said Matt, his oldest friend, in characteristically blunt fashion when Johnny had told him of his plans over several pints of Truman’s the night before. “But she’d be a fool if she did.”

Blunt, perhaps, but unswervingly loyal. Passing his sergeant’s exams had given Matt more than promotion in the ranks of the City of London Police; it had boosted his self-confidence – not that Johnny thought he needed any help in that department. Self-doubt was his own speciality.

He ambled through the quire – why the earlier spelling of choir was insisted upon was anybody’s guess – gazed at the dazzling blue and gold mosaics above him, passed the organ that would be bellowing out Old Hundredth the following morning, and turned right to face the windows where the unruly sun came streaming in. The funerary effigy of John Donne, the metaphysical poet who became Dean of St Paul’s in 1621, was now on his left. It was supernaturally realistic: every whisker of his beard, every crease of his shroud, stood out.

Johnny preferred prose to verse but he could still recall a few of the lines that Old Moggy had made them study, beating the rhythm with his wooden leg – supposedly made of mahogany, hence the teacher’s nickname. This, for example, from “The Anagram”:

Love built on beauty, soon as beauty, dies.

Stella would always be beautiful to him: even when she was sixty. Every time her almond eyes met his own his heart flipped. It seemed to liquefy and flood his body with euphoria. At such moments he felt he could do anything – and there was certainly nothing he wouldn’t do for her. The attraction wasn’t just physical – although he existed in a state of constant desire for her. He had never before made love to the same woman over such an extended period of time. His past was littered with a succession of brief but intense flings with actresses and dancers who had hoped he could help their careers by persuading colleagues to mention them in print. It still amazed him that sex with Stella got better and better, that the novelty did not wear off. She was his new-found land that he would never tire of exploring.

And yet he was equally happy simply doing nothing. It was enough just to be in her company. When they were together he felt complete. They made a handsome couple. They were the same height – five foot six; Johnny was accustomed to being looked down on – and shared other characteristics besides their startlingly green eyes: both were quick witted, with a fiery temper and a deep sense of fair play. However, Stella would not hesitate to knock him off his high horse when he was raging against social injustice.

It was not that she was in favour of inequality: she just couldn’t stand intellectual soppiness. Johnny had a tendency to get dewy-eyed about the plight of the underdog. Then again, he had seen a lot more than she had: more reality, more poverty and more death. Her protective father, a lumbering bear of a man who had no difficulty handling awkward customers, had done his best to shield her from the worst aspects of life in the capital. His possessiveness had ensured that they had yet to spend a whole night together. Johnny was not looking forward to asking him for permission to marry his daughter – if she said “yes”.

He hoped she wouldn’t make too much of a fuss about the 259 steps up to the gallery: a notice warned those wishing to ascend towards heaven that there were no stopping-off points on the way. It wasn’t as if he had chosen the Stone Gallery (378 steps) or even the Golden Gallery (530 steps).

On their second date they had climbed to the top of the Monument, the tallest isolated stone column in the world. Designed by Christopher Wren to commemor ate the Great Fire of London, which had started in Pudding Lane 202 feet away, it was consequently 202 feet high and contained 311 steps. When they had finally reached the iron cage at the top – built to prevent suicides – Johnny, checking no one was looking, had kissed her full, red lips and murmured, heart still pounding from the ascent: “You take my breath away.” Their laughter had hung between them in the frosty air.

He had felt on top of the world and wanted Stella to feel the same way. Together they had seen the City in a whole new light – a light enhanced and reflected by the flaming golden urn above them.

Johnny had made a point of going to places where neither of them had been before. The relationship was new territory for them both. Finally, in Postman’s Park, with its wall of plaques dedicated to local heroes, including Daniel Pemberton – foreman LSWR, surprised by a train when gauging the line, hurled his mate out of the track, saving his life at the cost of his own, Jan 17 1903 – Stella, fed up with all the talk of death, had said: “Next time, let’s go to the pictures like a normal couple.” The fact that she had referred to them as a “couple” had gone a long way towards mollifying him.

A love of the movies was another interest they shared. The death of Jean Harlow the month before had shocked them both. Hollywood’s first “sex goddess” was only twenty-six: four years younger than they were. Johnny had been mesmerised by her breasts the first time he had seen them burst out of the silver screen. He preferred her as a femme fatale in gangster flicks such as Beast of the City and Public Enemy rather than as a dizzy blonde in comedies like Hold Your Man and Wife versus Secretary. However, his reporter’s instincts were still intrigued by the echoes of Harlow’s personal life in Reckless.

The suicide of her on-screen husband Franchot Tone in the film recalled the death of Harlow’s second real-life husband Paul Bern, who was said to have shot himself in 1932. His apparent suicide note had a claim to being one of the worst ever:

Dearest dear. Unfortunately this is the only way to make good the frightful wrong I have done you and to wipe out my abject humiliation.

Paul.

You understand that last night was only a comedy.

What was more humiliating than being reduced to blowing out your brains? Yet the suicide rate had been climbing on both sides of the Atlantic throughout the decade. On the face of it Bern appeared to have had a lot to live for: he was both rich and respected. Even so the director had chosen to roll the end credits of his life story. Or had he? The men from MGM had been on the scene long before the cops or the coroner. What had the young Harlow seen in the much older, and reputedly impotent, man? She might have shot him herself in frustration. Johnny smelled a cover-up. One day he would write a book about it.

He had arranged to meet Stella in the middle of the sunburst on the floor beneath the centre of the dome. It was a visual representation of heaven on earth, a sign that Wren’s Masonic masterpiece was designed to unite the two. If Stella agreed to be his wife, the two of them would become one, and he would be in paradise. He stood 365 feet – one for each day of the year – beneath the golden cross that topped the dome. It didn’t seem a second since he and Stella had been laughing on top of the Monument – so much had happened since then. He glanced around yet again, hoping to spot her making her way towards him. No: as usual she was making him wait the full eight minutes.

Chapter Two (#ulink_fac65fd8-42f0-5ff0-8628-e5adc5b70976)

A woman screamed. A sickening crack echoed off the Portland stone. Tourists scattered across the black-and-white chequered marble. Johnny turned and, instinctively going against the flow of fleeing sightseers, moved closer to the centre of the action.

The jumper had fluked a soft landing but was surely dead. Black blood seeped from his head. Johnny knelt down and, using his fore and middle fingers, felt for a pulse behind the man’s ear. To his amazement, he detected a faint beat. He rolled him off the unfortunate clergyman he had landed on. It was too late: the corpulent priest resembled a beetle crushed by a callous schoolboy. He lay face down, his limbs and neck splayed at crazy angles. There was a hole in the sole of his left shoe.

Johnny, feeling nauseous, took a deep breath and exhaled slowly. If he had stood his ground for just a few seconds more it could have been him lying broken on the floor. Perhaps there was a god after all.

The suicide opened his eyes. The escaping blood had created a sticky halo round his head. His lips moved. Johnny bent down to hear what the beanpole was trying to say.

“I’m sorry. I . . .” His eyelids fluttered.

“What’s your name?” asked Johnny, already thinking of the piece he was going to write. He felt in vain for a pulse. The wretch was wearing a black suit of good quality. It was as if he had dressed up for the occasion. Johnny went through the man’s pockets. That was odd – they were completely empty. There was no wallet or loose change, no keys, not even a handkerchief.

“Can you believe it? He’s robbing the poor guy!” An American, flushed with indignation, pointed a pudgy finger at Johnny. The rubberneckers, reassured that it had not started raining men, had slowly gathered round to get a closer look. The circle tightened round him.

“Don’t be ridiculous. I’m trying to find out who he is. Why don’t you make yourself useful and go and find someone in authority?”

“There’s no need.” A middle-aged man in a dog collar gently cut through the crowd. Beady eyes took in the scene. They showed no sign of shock or grief. Countless funerals – in Britain and in France during the Great War – had inured him to death. “Please stand back.” He was plainly accustomed to being obeyed.

“Is he one of yours?” Johnny nodded at the flattened priest.

“And you are . . .?”

“John Steadman, Daily News.”

“Ah.” The gimlet eyes bore into him. “Mr Yapp was a member of our chapter. I presume he’s beyond our help?”

“Indeed. My deepest condolences.”

The clergyman searched for but could not detect a note of insincerity. “I’m Father Gillespie, Deacon of St Paul’s.”

“How d’you do.” They shook hands. Johnny reached into his pocket and flipped open the notebook with its miniature pencil held in a tiny leather loop. It went everywhere with him. “What were Mr Yapp’s Christian names?”

“Graham and Basil. He was proud to share his initials with Great Britain.”

“Thank you. I don’t suppose you know who the other man is? It seems he jumped from the Whispering Gallery.”

“He wouldn’t be the first to have done so.” The deacon sighed and lowered his voice. “And doubtless won’t be the last.” The eavesdroppers craned their necks. “Ladies and gentlemen, please stand back. This is a house of God, not a freak show.”

“The police will have to be informed.”

“The call is being made as we speak.”

Johnny was impressed. “That was quick.” It wouldn’t take long for the Snow Hill mob to get here. He handed Father Gillespie a business card. “May I telephone you later?”

“Of course. But what’s the hurry? You’re an eyewitness. The police will want to talk to you.”

“Actually, I’m not. I didn’t see the man jump. For all I know, he could have been pushed. However, by all means tell the cops I was here. They know where to find me.”

The ring of spectators that was growing by the minute reluctantly parted to let him through. Forgetting, once again, where they were, they broke into an excited chatter. A look of exasperation flitted across Gillespie’s face. Would he have to close the cathedral?

Johnny, using shorthand, scribbled down a few details while they were still fresh in his memory – the exact location of the bodies, the appearance of the two corpses, their time of death – before hurrying down the north aisle and out of the door by All Souls Chapel.

It was like standing in front of a blast furnace. He squinted in the sunshine, blinded for a moment, then hurried down the steps which in the dazzling light appeared to be nothing more than a series of black-and-white parallel lines. It was so hot even the pigeons had sought the shade.

Should he wait for Stella or run with the story? He only hesitated for a moment. She was not expecting him to propose so would not be particularly disappointed. Besides, it would serve her right for being late yet again. She would guess what had happened when she saw the bloody aftermath where they were supposed to have rendezvoused.

As he made his way down Ludgate Hill, overtaking red-faced shoppers, he slipped off his jacket and slung it over his arm. He took off his hat and loosened his tie. It made little difference. Sweat trickled down his spine, made his shirt stick to the small of his back. He licked his top lip. He was glad the office was only five minutes away. He could see it in the distance, shimmering in the haze.

The newsroom was a sauna even though all the third-floor windows were flung wide open. The roar of traffic competed with the constant trilling of telephones and the machine-gun tat-a-tat of typewriters. Fans whirred uselessly on every desk. Any unanchored piece of paper would be sent waltzing to the floor. The sweet smell of ink from the presses on the ground floor and dozens of lit cigarettes failed to mask the odour of unwashed armpits.

Johnny checked his pigeonhole for any post, memos or telephone messages. There were several slips from the Hello Girls on the ground floor and two envelopes. Before he could open either of them, Gustav Patsel, the news editor, came waddling up to him.

“It is your day off, no? What are you doing here?”

Rumours that Patsel was going to jump ship – go to another newspaper, or goose-step back to his Fatherland – had so far proved annoyingly untrue. He made no secret of the fact that he disapproved of Johnny’s recent promotion from junior to fully fledged reporter, but hadn’t had the guts to say anything to the editor, Victor Stone. Like most bullies he had a yellow belly. Johnny’s previous position remained unfilled. The management, trying to slow the soaring overheads, had ordered a temporary freeze on recruitment.

“Pencil” – as Patsel was mockingly known – considered Johnny disrespectful. He could never tell when he was being serious or insubordinately facetious. However, Steadman was too good a journalist to sack. His exposé of corruption within the City of London Police the previous Christmas was still talked about. Patsel couldn’t afford to lose any more staff from the crime desk – Bill Fox had retired in March – and furthermore he didn’t want Johnny working for the competition.

“I’ve got a story and I guarantee you no one else has got it – yet. A man’s just committed suicide in St Paul’s.”

“So what? Cowards kill themselves every day.”

“Only someone who doesn’t understand depression and despair would say that,” said Johnny, bristling. He held up his hand to stop the inevitable torrent of spluttering denial. “There’s more: he took someone with him. When he jumped from the Whispering Gallery he landed on a priest.”

“Ha!” The single syllable expressed both laughter and relief. Patsel’s eyes glittered behind the round, wire-rimmed glasses. “So much for the power of the Saviour. Has he been identified?”

“I know who the priest was, but the jumper didn’t have anything on him except his clothes. No money, no note, no photograph.”

“How do you know this?”

“I was there. I went through his pockets.”

Patsel was impressed – but he wasn’t about to show it.

“What?” Johnny could tell his boss was itching to say something.

“It is not important. Okay. Give me three hundred words – and try to get a name for the suicide.”

Johnny nodded. He had an hour and a half to develop the lead into a proper story. The copy deadline for the final edition was 5 p.m. There was a sports extra on a Saturday so that most of the match results could be included. He flopped down into Bill’s old chair and tipped back as far as he could go, just as his mentor had. Fox had taught him a great deal – in and out of the office. Although Johnny had no intention of following in the footsteps of the venal but essentially good-hearted hack, he had taken his desk when he left. It was by a window – not that it offered much of a view beyond the rain-streaked sooty tiles and rusting drainpipes in the light well at the core of the building.

“Stood you up, did she?” Louis Dimeo, the paper’s sports reporter, had slipped into the vacant seat at the desk opposite, which used to be Johnny’s. A grin lit up his dark, Italian features. Johnny was handsome enough but Louis, who spent most of his spare time kicking a ball or kissing girls, was in a different league – as he never stopped reminding him.

“Who?”

“Seeing more than one woman, are we? Surely you haven’t taken a leaf out of my book? Stella, of course.” They sometimes had a drink together after work – always with other colleagues, never alone – but Louis was too concerned about his physique to sink more than a couple of pints.

“An exclusive fell into my lap. Well, almost.” His telephone started ringing. “Haven’t you got anything better to do?”

“It’s all under control. The stringers will soon be calling the copytakers.”

“Why aren’t you at a match?”

“I drew the short straw. Answer the bloody thing!” He sloped off back to his own desk.

“Steadman speaking.”

“You must know by now that leaving the scene of a crime is against the law.”

“So is suicide, but there’s not much you can do about it, is there?” He smiled. It was always good to hear from Matt.

“What did she say?”

“I haven’t asked her. She hadn’t turned up by the time I left. She was late, as usual.”

“Constable Watkiss tells me you spoke to Father Gillespie. As you’re no doubt aware, the man who jumped had no identification on him. We’ll be releasing an artist’s impression of him on Monday – if his wife hasn’t reported him missing by then.”

“How d’you know he was married? He wasn’t wearing a ring.”

“We don’t. I’m just hazarding a guess. His appearance doesn’t match that of anyone on our missing-persons list.”

“Is it okay for me to describe him in my piece? It might prompt someone to come forward.” Johnny held his breath.

“Yes – but I didn’t say that you could. Understood?”

“Of course. Thank you. Have you informed Yapp’s next of kin yet?”

“We’re trying to find out who that is. He was unmarried. Your piece might prove doubly useful.”

“I aim to please. Fancy a drink later?”

“Aren’t you going to see Stella?”

“Why can’t I see both of you?”

“I thought you had something to ask her.”

“I still want to do it in St Paul’s. I’m not going to let what happened stop me.” Some might have chosen to see the accident as an ill omen – but not him. He refused to believe in such nonsense.

“Very well. I’ll be on duty till eight p.m. If I’m not in the Rolling Barrel, I’ll be in the Viaduct.” Matt hung up before he could say anything else.

Instead of replacing the receiver, Johnny dialled the number of The Cock. He knew it off by heart.

“Hello, Mrs Bennion. It’s Johnny. Is Stella there?”

“I’ve told you before: call me Dolly. I thought she was seeing you today.”

“We were due to meet this afternoon but I had to come in to the office. I assumed she’d be back home by now. Perhaps she’s gone shopping.”

“Wouldn’t surprise me.” She lowered her voice. “Did you see Stella last night?”

“No. I haven’t seen her since Thursday. Why?”

“She told us that she was going to visit a friend in Brighton and since she didn’t have to go to work the next day she would spend the night there. Her father took some persuading. He thought you were behind it!”

“Alas, no.” Should he have said that? “So you haven’t heard from her since yesterday?”

“Not a dicky bird.”

“Well, don’t worry. I’m sure she’ll turn up any minute now.”

“I hope so.” She did not sound convinced. Johnny had said the wrong thing: telling people not to worry just served to raise their concern. It was like the dentist, drill in hand, telling you to relax: the very word made you tense up in anticipation of pain.

“I know so. Give my regards to Mr Bennion.”

“I will. He’s having his afternoon nap before the doors open again.” Johnny cursed himself silently. He had probably just woken up his prospective father-inlaw, who already suspected him of whisking off his daughter for a prolonged bout of seaside sex. Now that was inauspicious.

He replaced the receiver and stuck his face in front of the desk-fan. The back of it, which contained the tiny motor, was too hot to touch. The place would probably be cooler if all the fans were turned off.

He should have waited for Stella. What if she hadn’t gone to St Paul’s? Perhaps she had not meant to be late. Something – something bad – could have happened. He crushed the thought. Maybe the beach and the sea breezes had proved too much of a temptation and she had decided to spend the entire weekend away from the stifling City. He wouldn’t blame her if she had.

Stella had never mentioned a pal who lived in Brighton. He’d assumed he’d been introduced to all her friends by now: she’d certainly been introduced to all of his. He enjoyed showing her off, being told that he’d done well for himself, batting away such envious remarks as “Lost her white stick, has she?” Then again, if he had chosen well, so had she. Stella held his heart in her hands. She knew she could count on him.

He checked that the plain gold band was still safely buttoned up in his jacket. It should have been on her finger by now. He sighed in disappointment – but there was no use dwelling on what might have been. He got out his notebook. He had work to do.

It took him less than half an hour. Father Gillespie was unable to furnish him with any further information except the fact that Graham Yapp had been forty-eight. As he bashed out the report, Johnny recalled the other dead man’s expression as he had looked down from the gallery. Even from where he was sitting Johnny could tell it had been one of anticipation rather than fear, of anger rather than regret. And yet his last words had been I’m sorry: an apology for breaking the God-botherer’s neck? A believer was unlikely to have chosen such a place to kill himself.

He handed in his copy to the subs and returned just in time to catch the tea lady. His mother had always said a hot drink was more cooling than a cold one – but only because it encouraged perspiration. He sipped the stewed brew and stared into space. The story was a minor scoop but it had made him a hostage to fortune. If the jumper turned out to have been pushed he would look like an incompetent fool.

He read his messages – there was nothing that couldn’t wait till Monday morning – then turned his attention to the mail.

The two envelopes were the same size but there the similarity ended. The first one was cream-coloured and unsealed. The thick weave of the paper felt pleasurably expensive. It contained a postcard of Saint Anastasia. The martyr, golden-haloed, was draped in red robes. She held a book in one hand and a sprig of palm in the other. A look of ecstasy spread across her pale face. There was a single sentence, carefully inscribed in a swooping hand, on the back:

Beauty is not in the face; beauty is a light in the heart.

There was no signature. He was always getting letters from cranks. To begin with he had kept them in a file along with the threats of grievous bodily harm – or worse – from people who disagreed with what he had written or objected to having their criminal activities exposed in print. Nowadays he just threw them straight in what the public schoolboys, who were everywhere in the City, called the wagger-pagger-bagger. However, he liked the image of the serene saint so he simply put it to one side.

The second envelope, a cheap white one that could have been bought in any stationer’s, was sealed. Wary of paper cuts, he used a ruler to slit it open. An invitation requested his presence at the re-opening of the much-missed Cave of the Golden Calf in Dark House Lane, EC4 on Friday, 9th July from 10 p.m. onwards. A woman, one arm in the air, danced on the left side of the card. Johnny studied the Vorticist design: the way a straight black line and a few jagged triangles conjured up an image of swirling movement, of sheer abandon, was remarkable.

Much-missed? He had never heard of the place. Still, it was intriguing. What was the Cave? A new restaurant? Theatre? Nightclub? There was no telephone number or address to RSVP to, so he would have to turn up to find out. Perhaps Stella would like to go.

Chapter Three (#ulink_fa78157b-4187-53e1-89db-b2177d65bedd)

He hung around for as long as he could, willing the telephone to ring. It didn’t.

Patsel, throwing his considerable weight about as usual, provided a distraction. Bertram Blenkinsopp, a long-serving news correspondent, had written a piece about widespread fears that the groups of Hitler Youth currently on cycling tours of Britain were actually on reconnaissance missions. The smiling teenagers – who looked, at least in the photographs, very smart in their navy blue uniforms of shorts and loose, open-neck tunics – were said to be “spyclists” sent to note down the exact locations of such strategic sites as steelworks and gasworks. Why else would they have visited Sheffield and Glasgow?

However, Patsel, putting the interests of the Fatherland above those of his adopted country, spiked the article – “Where’s the proof?” – and accused Blenkinsopp of producing anti-Fascist propaganda. A stand-up row ensued. The whole newsroom kept their heads down and pretended not to be listening as the irate reporter lambasted his so-called superior:

“You’re not fit to be a journalist. You wouldn’t know a good story if it came up and kicked your fat arse.”

Such exchanges were not uncommon – Patsel had given up complaining to the high-ups; their inaction was widely interpreted as a suggestion that the German should quit before he was interned – but they had become more frequent as the heatwave lengthened and tempers shortened.

The oppressive temperatures only added to the sense of a gathering storm. The “war to end all wars” had been nothing of the sort. It was becoming increasingly obvious each week that diplomacy – or, as Blenkinsopp put it, lily-livered appeasement – had failed and that Britain would soon be at war again.

The argument stopped as suddenly as it had started. Blenkinsopp knew there was nothing he could do: the Hun’s word was final. He stormed off to the pub leaving Patsel pontificating to thin air. Johnny, catching Dimeo’s eye, had to bite the inside of his cheek to stop himself grinning. Blenkinsopp had the right idea: it was time for a beer.

Johnny joined the exodus of office-workers as they poured out into the less than fresh air. The north side of Fleet Street remained in the sun: its dusty flagstones radiated heat. A stench that had recently become all too familiar hung over its drains. Johnny, ignoring the horns of impatient drivers, crossed over into the shade. He still had a couple of hours to kill before he was due to meet Matt.

He lit a cigarette and strolled down to Ludgate Circus, jostled by those keen to get back to their families, gardens or allotments. It was not an evening to go to the pictures. Cinema managers were already complaining about the drop in audiences. On the other hand, the lidos were packed out. People were fighting – literally – to get in.

In Farringdon Street the booksellers were closing up for the day, a few bibliophiles browsing among the barrows until the very moment the potential bargains disappeared beneath ancient tarpaulins. He cut through Bear Alley and came out opposite the Old Bailey.

A crowd of men, beer in hand, sleeves rolled up, blocked the pavement in West Smithfield. It was illegal to drink out of doors but in such weather indulgent coppers would turn a blind eye – in return for a double Scotch. Squeals and shouts came from children playing barefoot in the recreation ground. A couple of them were trying to squirt the others by redirecting the jet of the drinking fountain. There was a palpable sense of relief that the working week was finally over.

The swing doors of The Cock were wedged open. Stella’s father was behind the bar. Johnny perched on a stool and waited for him to finish serving one of his regulars, a retired poulterer who didn’t know what else to do but drink himself to death.

“So she really isn’t with you then?”

Johnny noted the choice of words – isn’t not wasn’t – and shook his head. “Still no word?”

“Not a blooming thing. This isn’t like her.” Bennion ran his hand through greying hair that was becoming sparser by the day. “What’ll you have?”

“Pint of bitter, please.” Johnny put the money on the bar. He had always made a point of paying for his drinks. It had made little difference though: Stella’s father had never liked him. Johnny didn’t take it personally: no man would ever be good enough for his Stella.

“We brought her up to be better than this.” He put the glass down on the mat in front of Johnny then helped himself to a whisky. He ignored the pile of pennies.

“Has she ever forgotten to call before?” Johnny opened a pack of Woodbines and, out of politeness, offered one to Bennion. To his surprise, he took one.

“Thanks. It’ll make a change from roll-ups.”

Johnny did not understand the attraction of rolling your own: flattening out the paper, sprinkling the line of tobacco that always reminded him of a centipede, licking the edge of the paper and rolling it up – usually with nicotine-stained fingers. It was such a fiddly, time-consuming business. Why go to all that trouble when someone else had already done so? To save money, he supposed: in the long run, roll-ups were much cheaper. Dolly preferred ready-made cigarettes as well: Sweet Aftons. They were, according to the ads, good for the throat.

“She won’t have forgotten. There are only two reasons why she hasn’t rung: either she’s unable to or she doesn’t want to. Dolly’s been asking around but not heard anything encouraging. A lot of her friends don’t have a telephone.”

“Perhaps she’s just staying on the beach for as long as she can,” said Johnny. He never sunbathed: his pale skin soon burned.

“Are you still in touch with Sergeant Turner?” Bennion, who generally made a point of looking everyone in the eye, gazed over Johnny’s shoulder. So that was it: he wanted something. That explained his embarrassment.

“I’m seeing him later,” said Johnny, and drained his glass.

“Another?”

“Please.” The publican, having served a couple of customers, returned with a fresh pint. The pile of pennies remained untouched.

“Could you ask him to make a few enquiries?”

“I’m as anxious as you are to see Stella again,” said Johnny. “She’s only been gone for a day though. It’s too early to report her missing. Besides, she could turn up at any second.”

“And what if she doesn’t?”

“I’ll do everything I can to find her – and that includes enlisting the help of Matt and his men. If she’s not back by Monday morning I’ll raise the alarm myself.” The possibility that some ill had befallen her filled him with panic. He drowned it with beer.

He was half-cut after his third pint. The heat increased the power of the alcohol. There was still no sign of Stella. The pavement beneath his feet felt spongy. He sauntered down Hosier Lane, along King Street and into Snow Hill where John Bunyan’s earthly pilgrimage was said to have come to an end.

It was cooler now: the incoming tide had brought a freshening breeze which felt delightful against his hot skin. The cloudless sky was a brilliant blue dome that stretched serenely over the exhausted capital. A kestrel hovered overhead. Johnny stopped and enjoyed one of those rare, uncanny moments when, despite its millions of inhabitants, thousands of vehicles and ceaseless activity, there was complete silence in the city. Seconds later it was shattered by the sound of smashing glass and an ironic cheer.

The Rolling Barrel was only a few doors down from Snow Hill police station, so it was the first place that thirsty coppers made for when they came off duty. It was gloomy and smoky inside the pub. All the tables were taken so Johnny went to the bar. The clock behind the bar showed it was five past eight.

“What are you doing here, Steadman?” Philip Dwyer, one of Matt’s colleagues, glared at him. “Haven’t you done enough damage?”

The sergeant’s eyes were glazed and his speech was slurred. Surely he couldn’t have got in such a state in five minutes?

Dwyer leaned forward. A blast of beery breath hit Johnny in the face. “Be a good chap and fuck off.”

As a journalist, Johnny was accustomed to being unpopular. However, his unmasking of corruption at Snow Hill in December had hit a nerve both within the force and without. The ensuing scandal had made Johnny’s name – but at considerable cost to himself and Matt. His investigations had also led to the deaths of four other men. They would always lie heavily on his conscience. Rumours about what had happened to him and Matt continued to circulate – out of Matt’s earshot. No one wanted to get on the wrong side of the big, blond boxer.

Johnny was in no mood to be pushed around by a drunken desk sergeant, especially when he could see that Matt wasn’t in the boozer. There was no point in buying a drink just to annoy Dwyer: in the state he was in he might throw a punch, Johnny would throw one back and then end up being arrested. Johnny strolled out and soon he found Matt propping up the bar in the Viaduct Tavern, round the corner in Giltspur Street.

“Dwyer just told me to fuck off.”

“Glad to see you did as you were told for once.”

“It’s good to see you too.”

Johnny meant it. He immediately felt at ease in Matt’s company. He always did. It was as if a chemical reaction took place, their personalities somehow combining to produce a sense of well-being. No one else had this effect on Johnny. Matt was a winner of the lottery of life: he was tall, very good-looking and popular. He literally saw the world in a different way to other, shorter, people. As much as Stella made Johnny happy and alleviated his habitual loneliness, she didn’t make him feel safe, secure and stronger in himself the way Matt did. It was, he supposed, his role to make her feel that way. At the moment, though, Stella was making him nervous and fearful. Nervous about what she would say when he eventually popped the question and fearful about her disappearance. He needed some Dutch courage.

“Same again?”

“I’ll have one for the road, thanks. I promised Lizzie that I’d be home by ten – and given the mood she’s in these days there’ll be hell to pay if I’m not.”

Once upon a time Johnny would have experienced a stab of jealousy at such a remark. He had fallen for Lizzie as soon as he set eyes on her and had been heartbroken when she had – quite understandably, in his opinion – chosen Matt as her husband instead of him. Lizzie had worked hard to convince Johnny that his love for her was just an adolescent crush. Now they were, in the time-honoured phrase, “just good friends”.Nevertheless, a part of Johnny remained unconvinced. He was happy for Matt – he and Lizzie had an enviable marriage – yet in his eyes she would always be “the one that got away”.

“How is Lizzie?” They moved over to a table that had just been vacated by a pair of postmen. Johnny set down the glasses on its ring-stained veneer.

“She’s finding the heat unbearable – although it’s not quite as suffocating in Bexley.”

Johnny had been afraid that he would see less of his friend when he moved from Islington to one of the new housing developments that were sprawling out across the virgin countryside round the capital. However, because police officers were not permitted to live more than thirty minutes from their station, the move had produced the opposite effect. Matt had to sleep in the officers” dormitory at Snow Hill more often than in the past.

Lizzie, who had cajoled Matt into the move, now complained that he was hardly ever at home. She had been forced to give up her job in Gamage’s, the “People’s Popular Emporium”, when she became noticeably pregnant. Apparently customers did not wish to be served by mothers-to-be – even in the maternity department. Six months on, she was stuck in the new three-bedroom house, miles away from all her friends and with only the baby inside her for company.

“When’s the big day?” said Johnny.

“A couple more weeks – but we’ve been warned that first babies are often overdue.”

“Who can blame them?” Johnny took another swig of his bitter. “What a time to enter the world.”

“At least I won’t have to enlist: being a copper is a restricted occupation. Pity, really. I fancy killing a few Nazis. What will you do if and when the balloon goes up?”

“I haven’t given it much thought. My flat feet will keep me out of the army. Perhaps I’ll get a job with the Ministry of Information, or I could be a stretcher-bearer.”

“Let’s hope it won’t come to that. Chamberlain might yet save the day.”

“Sure – and I’m going win the Nobel Prize for Literature.”

“You’ll have to write a novel first.”

“As a matter of fact I’ve started.”

“Pull the other one. You’ve been talking about writing a book for years.”

“It’s true. I’ve only written the first few chapters, but I’m enjoying the process so far. It makes a change from having to report the facts. It’s so liberating to be able to make things up. It’s like taking off a straitjacket.”

“Have you got a title?”

“Friends and Lovers. But I’ll probably change it.”

“What’s it about?”

“You and me, amongst other things. Most first novels are autobiographical.”

Matt put down his pint. His blue eyes stared into Johnny’s. “I trust you’ll be discreet.”

“Of course. You’ve got nothing to worry about, Matt – even if it ever does get published.”

“I hope so. Does Stella know you’re writing about her?”

“She knows I’m writing a novel. Actually, she’s the reason I haven’t been making much progress.”

Matt laughed. “Real-life lovers are more fun than made-up ones.”

“In most cases, certainly. However, it seems Stella’s gone missing. Her parents haven’t seen her since yesterday morning and I still don’t know whether or not she turned up at St Paul’s this afternoon.”

“Perhaps she’s punishing you for putting the job first.”

“The thought had crossed my mind. But it doesn’t explain why she’s taking out her frustration on her parents. She told them she was staying in Brighton last night. If she’d decided to stay another day, she should have let them know.”

“She probably guessed you were going to propose. That’d be enough to make any woman run a mile.”

“Thanks for the vote of confidence.” Johnny lit a cigarette but didn’t offer Matt one. He was trying to give them up. Lizzie didn’t like him smoking in their new home. “Any news about the nameless suicide?”

“Nothing. A post-mortem will be held on Monday.”

“Perhaps the Daily News will come to your aid.”

“I saw your piece. It was good of you to play down the horror of the situation. Imagine learning of your husband’s death in a newspaper.”

“I did – hence my reticence. However, the bloody halo round the dead man’s head was too good an image not to use. Some will no doubt find it sacrilegious and/ or inappropriate. There’s never any shortage of readers willing to go out of their way to be offended.”

Matt checked his watch. Should he tell Johnny now? No, there was no point worrying him unnecessarily. The postcard might prove to be nothing more than an empty threat. Johnny had enough on his plate as it was. He got to his feet. They still ached at the end of the day, even though he no longer had to pound the pavements the way he had before his promotion.

“I must be off. Why don’t you come down to Bexley on Wednesday? I’ve got the day off and could do with some help in the garden. I say ‘garden’ – at the moment it’s just a square of dry, brown earth. Lizzie would love to see you.”

“It will be a pleasure – kind of. As long as there’s plenty of beer.”

He watched Matt make his way out of the pub, the crowd parting like the Red Sea. No one, sober or not, wanted to pick a fight with the handsome giant. Johnny felt very fortunate to have such a friend.

Stella lay in the darkness, alone and afraid in the strange surroundings. She had a raging thirst. The pain came in waves, ebbing and flowing as she tried to find a more comfortable position. She had been an utter fool to trust the man. To make matters worse he was the only person who knew where she was. She was still scared by his blithe assurance that her ordeal would soon be over.

The bleeding had stopped – eventually. She had to get out of here. But how could she, when each move made her cry out in agony? She was paying for her impulsiveness now.

A sudden draught told her that somewhere a door had been opened and closed. Stealthy footsteps came down the stairs.

“Ah, still not in dreamland?” His whisper was menacing rather than soothing. “Here, this will help.” He took her arm. The needle sank into her flesh. Moments later she was unconscious.

Chapter Four (#ulink_d92c663e-0cb5-5cd1-84bd-5e7211fc21e4)

Sunday, 4th July, 4 p.m.

He left the bedroom window open, lay naked under one sheet, but still found it difficult to sleep. The heat seeped down from the cooling roof-slates. Stella haunted his dreams, one moment laughing at his foolish fears, the next lying dead in a back alley. She had no right to treat him like this. The ring was back in his mother’s jewellery box.

It was the first Sunday they had not been together in months. Johnny had spent the morning reading the papers: Amelia Earhart was still missing somewhere over the Pacific. The sports pages were dominated by the Wimbledon singles finals. The American Donald Budge had beaten the kraut Gottfried von Cramm – which was something – and Dorothy Round had saved Britain’s pride by defeating a Pole called Jadwiga Jedrzejowska. However, Johnny wasn’t particularly interested: tennis was a game for posh people.

He was too restless to sit indoors and work on his novel so, after a stale potted-meat sandwich, he walked up to Islington Green, which was so crowded there wasn’t a blade of grass to be seen. Even the steps of the war memorial were crowded with families. Dress codes had been abandoned. It may have been the Sabbath, but rolled-up shirt-sleeves and knotted handkerchiefs were everywhere. The sellers of wafers, cornets and Snofrutes were making a fortune.

He strolled beneath the wilting plane trees on Upper Street and, just as he knew he would, found himself going down St John Street to Smithfield.

The Cock was closed. His knocking went unanswered. If Stella had returned there would surely have been someone home. He had been looking forward to a surreptitious beer but had to make do with the drinking fountain across the way.

Johnny hated being at a loose end. Work, as Thomas Carlyle observed, was a great cure for boredom and misery. The “great black dome” of St Paul’s, seen bulging behind Newgate Prison in Great Expectations, beckoned.

Charles Dickens was, as far as Johnny was concerned, the greatest writer that had ever lived. He had read his complete works twice, fascinated by how much and how little his native city had changed. Only three of his characters had ventured into the cathedral: Master Humphrey; David Copperfield, when giving Peggotty a guided tour of the capital; and John Browdie who sets his watch by its clock in Nicholas Nickleby. However, the image that struck Johnny most deeply was that of Jo, the young street-sweeper in Bleak House, who stares in wonder at the cross on its summit as he gobbles his hard-earned food on Blackfriars Bridge.

He was glad to find there was no service currently in progress. Not a speck of blood besmirched the polished marble where the two men – one by desire, one by ill-luck – had gone to meet their maker. The Whispering Gallery was closed – so even if Stella had been with him he could not have proposed to her.

“We meet again.” Father Gillespie regarded him over a pair of half-moon glasses. “I saw your item in the News. The bit about the halo was most amusing.” Was he being sarcastic? The deacon sat down beside him. “Any developments?”

“I haven’t been back to the office since it appeared. I’ll find out tomorrow morning.” Johnny didn’t want everyone knowing he had nothing better to do on a Sunday.

“I prayed for them both,” said the priest. “Especially the man who jumped – he won’t be buried in hallowed ground. Mr Yapp, on the other hand, will be. The one consolation is that he probably didn’t know what – or rather who – hit him.”

“And they say God looks after his own.”

Gillespie frowned. “Such cynicism in one so young. What are you doing here, if you’re a non-believer?”

“Just revisiting the scene of the crime. I take it you deem suicide to be a criminal act?”

“Indeed. God has plans for us all. He believes in you even if you don’t believe in Him.”

“I’m glad someone does. I was going to ask my girlfriend to marry me yesterday, but she’s gone missing.”

“Ah. Many girls run after an ill-starred suitor pops the question.”

“Are you married?”

“No – but . . .” He held up a forefinger to silence him. “That doesn’t mean I don’t know what I’m talking about.” He looked around for a moment, as if making up his mind about something. “Here you are –” He produced a key and a piece of paper from beneath his surplice. “These were found in the collection box last night. I telephoned the police, but they didn’t seem that interested.”

The key was a brass Chubb, the teeth of which, when turned upward, resembled the turrets of a castle. It was probably a door-key. The piece of paper was more interesting. It was old and creased, as if it had been carried in a wallet for years. There were four words written on it in a childish scrawl: I love you daddy.

Johnny was unexpectedly moved. Had he ever said those words to his father?

“This is not the sort of thing you’d throw away casually.”

“I agree.” The deacon nodded. “Which is why I kept it. You’d be amazed at what we find in the collection box: sweet wrappers, cigarette ends, prayers and curses . . .”

“How often is it emptied?”

“Every evening when the cathedral closes. We can’t be too careful nowadays. It’s been broken into twice recently. We live in desperate times.”

“Did they get away with much?”

“A couple of pounds. Donations have dwindled and yet the list of vital repairs gets longer each year. Secular needs, alas, have supplanted spiritual ones.”

“Whose responsibility is it to empty the box?”

“The sacristan’s. He brings the money to me and, having counted it, I lock it in a cash-box kept in my office.”

“So these items must have been put in the box yesterday. Why?”

“I was hoping you would find that out, since the police clearly consider the matter unworthy of their attention. Of course there may be no connection between the two items. However, I suspect they could have some bearing on what happened yesterday.”

Johnny was not convinced.

“If you’re about to kill yourself, surely you’d keep something of such sentimental value on your person. I love you daddy . . . The first thing to ascertain is whether or not the jumper was a father.”

“Well,” said Father Gillespie. “That should be easy, once you know his identity. I expect the key may prove more of a problem. I’ve heard of the key to the mystery, but not the mystery of the key!” He laughed at his own joke, then quickly composed himself. “I must prepare for evensong.”

“Thank you,” said Johnny. “I’ll keep you informed.”

“I’d appreciate it. I hope the lucky young lady says yes. God bless.”

He hated sunlight. He was a creature of the night, a lover of winter, a denizen of darkness where he could breathe and behave more freely. He was as old as the century, very rich – his dead father had been a banker and his late mother a cheese-parer – and, if viewed from the right, an extremely handsome man. However, those who caught the left side of his face would either stare, quickly avert their gaze or scream.

His townhouse in St John’s Square, Clerkenwell, was a shrine to modernism and, in particular, Art Deco. Chrome and glass sparkled throughout the spacious, sparely furnished rooms. Mirrors, however, were conspicuously absent.

An only child, he had long looked forward to disposing of his father’s art collection which consisted mainly of works by Lawrence Alma-Tadema. The pictures were too tawdry, too decadent; the women were too languorous, draped in too many clothes. He preferred nudes by Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele, and would spend many daylight hours studying the intricacies of the female form and its precious, perfect skin. At night he prowled the streets of the capital, relishing the liberty that the shadows granted him.

He had no need to work – and the thought of having to mix with colleagues terrified him – so he spent his lonely days reading and planning long trips abroad: Paris, Rome, Venice and, his favourite destination, Berlin. His money isolated him from the common herd and silenced the exclamations of flunkeys. His extensive range of hats and scarves, plus the use of cosmetics, enabled him to pass unnoticed for at least some of the time. Heat, though, made his make-up trickle on to his upturned collars.

Top-class prostitutes were regular visitors at his London home – until, while being taken only from behind, they made the mistake of glancing back at their generous, eccentric client. Goose-feather pillows could stifle screams of horror as well as ecstasy.

He lay naked on the vast bed, waiting for the heat of the afternoon to subside. His pale, muscular body was surprisingly unmarked. He stroked his flat stomach slowly and admired the curves of his long, straight legs. Legs that had carried him out of trouble on countless occasions. He exercised every day with a pair of Indian clubs, swinging them until his body gleamed with sweat. His hand moved to his groin.

No, not again. He had to save himself for tonight. She wouldn’t last much longer. He smiled in anticipation. The Dom Pérignon was already on ice. The thought of her tears, as he drank the champagne from a silver tankard, was exquisite.

Ignoring his erection, he got up to run a bath.

Chapter Five (#ulink_5f5f9004-15d3-5237-aa1e-57ca9801f979)

Monday, 5th July, 7.45 a.m.

The start of a new working week usually filled Johnny with optimism and excitement. Who knew what it held in store? This particular Monday, though, he was filled with foreboding. He had slept only fitfully, tormented by dreams of entrapment and deceit. His claustrophobia had worsened since December.

Stella was still missing. Acting out of character was a sure sign that something was wrong. Her worried parents had not heard from her. The silence was torturing him. He would call the bank on the stroke of eight o’clock.

The sound of someone whistling made him look up. Reg, one of the boys from the post-room, was heading through the maze of desks towards him.

“Mornin’, squire.” Reg plonked a large parcel down in front of him. “Ain’t you going to open it?”

“Give me a chance!” Johnny stubbed out his cigarette. The long, narrow box was wrapped in brown paper and secured with string. There was something familiar about the handwriting on the label. Reg produced a pocket knife from his trousers and handed it to him. It was unpleasantly warm. “Haven’t you got anything better to do?”

“You’re the one who goes on about the virtues of an enquiring mind.”

“I don’t ‘go on’ about anything. If Patsel catches you lurking, you’ll get a clip round the ear.”

“I can move a lot quicker than that Nazi.”

Johnny cut through the string, tore off the paper and blushed. The cellophane in the lid of the box showed it was full of red roses.

Reg whistled in mock-admiration. “Who’s a lucky boy then?” He didn’t even try to hide his giggling.

“Shut your face,” hissed Johnny. No one gave a man flowers. Whoever had sent them was trying to humiliate him. The stems were freshly cut, the buds half-open. Johnny counted twelve – the lover’s cliché. Their glowing colour reminded him of Stella’s lips.

“Who sent them?”

“That’s what I’m about to find out, I hope.” Johnny opened the cream envelope. Saint Basilissa – another unheard of martyr – beamed out from the postcard. The image was identical to that of St Anastasia except that the robes were blue. The back, unsigned, simply stated:

By plucking her petals, you do not gather the beauty of the flower.

Another bleeding quotation. Reg, who was now perched on the corner of his desk, sniffed. Johnny, taking the hint, did the same. The heady scent of the roses overlay something less alluring yet equally sweet. He looked at the boy, who had stopped grinning.

“Bit heavy for just a dozen roses.” Johnny picked up the box. He was right. There was a brain behind the bravado.

Wary of thorns, Johnny cautiously parted the thick, green foliage. Reg, unable to restrain himself, peered over his shoulder. They both recoiled when they saw what it was.

“Is it real?” Reg, curiosity conquering his instinctive revulsion, leaned forward to take a closer look. Johnny could smell the brilliantine on the lad’s hair.

“I think so – but there’s nothing to be afraid of. It can hardly grab you round the neck.”

They stared at the human arm that had been severed at the elbow. Even if the broken nails had not been painted red, the slenderness of the fingers and the lack of hair on the forearm suggested it had once belonged to a woman. Its smooth, soft skin was now blotchy, the flesh pulpy like that of an overripe peach.

“Need a hand?” Louis Dimeo stared at the limb. “Bit whiffy, isn’t it?”

“What d’you expect in this heat?” Johnny pushed the vile object away from him.

The sports reporter shrugged. He didn’t seem at all revolted. “Of course, it doesn’t necessarily mean that she’s dead. The arm could have been amputated. As far as I can see, there’s not a speck of blood.”

“She? I hope you’re not implying this is Stella’s arm.” The sickening thought had crossed his mind. He refused to dwell on the possibility of such an atrocity – but the arm had belonged to someone, someone who he hoped had been dead already.

“Certainly not. She . . .”

“Go on.”

Dimeo, aware that he had better tread carefully, swallowed. “I didn’t mean anything, Johnny, honest. I was just wondering why it was sent to you.”

“It’s a good question.” Johnny, trying not to shudder, replaced the lid on the box and waved away his colleagues, who were threatening to gather like flies on shit. Clearly, news of the parcel was spreading rapidly. The hacks returned to their desks muttering in disappointment.

“It’s more than likely just an armless prank,” said Dimeo. Johnny sighed in exasperation. The newsroom thrived on gallows humour, but for some reason this seemed personal.

“Don’t you have anything better to do?”

With a final wink for Reg’s benefit, Dimeo strolled away. “I don’t suppose you saw who delivered this?”

Reg shook his head. “It was left outside the back entrance. Charlie found it when he arrived at seven.”

The delivery manager was a punctilious timekeeper and expected his minions to follow suit. They worked twelve-hour shifts that began at 7.30 a.m., with only a thirty-minute break for lunch.

“Okay. Tell Charlie the police will probably want to speak to him. Go on, sling your hook.”

The telephone rang.

“The jumper’s name is Frederick William Callingham. Doctor Callingham, actually. He was a General Practioner.”

“Matt! I was just about to call you.”

“Well, I’ve saved you the trouble. His wife Cynthia contacted us last night. A neighbour saw your piece and, knowing her husband was missing, took it round to show her yesterday. She’s going to officially identify the body this morning.”

The week had hardly started yet already Matt sounded exhausted. He was certainly not in the mood for chitchat.

“Where’s the body now?”

“At the mortuary in Moor Lane.”

“Can I interview Mrs Callingham?”

“I would, of course, normally say that it is not the role of the City of London Police to aid and abet gentlemen of the press, but in this case the lady in question has expressed a wish to talk to the man who was with ‘her Fred’ when he died.”

“Excellent. What time should I turn up?”

“She should be available from ten fifteen. Don’t forget what she’ll have just been through.”

“As if.” It wasn’t like Matt to tell him how to do his job. Johnny prided himself on his sensitive treatment of interviewees – assuming they deserved it.

“Was there anything else?” Matt put his hand over the mouthpiece and spoke to someone. Johnny, waiting for his friend to finish, couldn’t hear what was said.

“Don’t you want to know why I was about to call you?”

“Stop pussyfooting around, Johnny. Just spit it out!”

“There’s a woman’s arm on my desk. It was delivered in a box with a dozen red roses this morning.”

“Why the devil didn’t you tell me right away?”

“I could hardly get a word in.”

“Pull the other one. You were waiting till I’d spilled all the beans.” Matt placed his hand over the receiver again while he spoke to whoever it was. This time Johnny heard him tell them to bloody well wait a minute. “I take it you’re not spinning me a yarn.”

“When have I ever lied to you?” There had been a few occasions.

“Very well. I’ll send someone to collect it and take your statement.”

“I won’t be here, though: I’ll be at Moor Lane.”

“A possible murder is more important than a grieving widow’s sob-story. Stay put until you’ve spoken to the detective.” Without waiting for a response, Matt hung up.

Johnny was fed up with being told what to do: he didn’t work for Matt. Then again, the last time he had ignored Matt’s orders he had nearly got both of them killed. He was about to make the same mistake.

It was five past eight. He gave the switchboard the number for Hoare & Co. The answering telephonist, having ascertained his name, asked him to wait.

“Mr Steadman?”

“Yes.”

“This is Margaret Budibent. May I enquire the nature of your business with Miss Bennion?”

Johnny could picture her: a stout woman in her mid-fifties. He could see the half-moon glasses perched on the end of her powdered nose. Her affected way of speaking did not quite disguise her working-class vowels.

“No, you may not.”

“Oh.” She wasn’t accustomed to being challenged. “She’s not here. She’s sick. Well, that’s what the man said.”

“What man?”

“The man who called. He wouldn’t give a name.”

“What exactly did he say?”

Miss Budibent had another try at asserting her authority. “What business is it of yours?”

“I’m her fiancé” – well, he would be if all went according to plan – “and neither I nor her parents, with whom she lives, have seen her since Friday morning. For all we know, Stella could have been abducted.”

“That is indeed somewhat alarming.” Margaret Budibent could not have sounded less concerned if she tried. “Miss Bennion was not in the office on Friday – she took the day off at the last minute. And most inconvenient it was too. But she said she would be back at work today. Then this stranger called, just five minutes ago.”

“What did he say?”

“Simply that he was calling on behalf of Stella, who was ‘indisposed’ – that’s the word he used. Before I could ask him anything else, he hung up. Some people are so ill mannered.”

“What did he sound like? Did he have an accent?”

“I can’t say as I noticed. Let me think.” Johnny could hear her wheezing as she silently replayed the conversation in her head. “He had a local accent.”

“Cockney?”

“No, better than that. I mean he sounded as if he was from the Home Counties. Then again, there was something stilted about his speech. That’s it: he sounded as if he were reading a script rather than just talking.”

Johnny gave her his extension number at the Daily News, then, having extracted a promise that she would call if she heard anything more, thanked her and hung up. Why hadn’t Stella called the bank herself? Had the stranger called The Cock as well?

“Mrs Bennion? It’s Johnny.”

“Hello, dear. You must be so relieved.”

“About what?”

“Ain’t no one called you?”

“No, not in connection with Stella.”

“That ain’t right. What’s she playing at?”

“I wish I knew. Where is she?”

“Still in Brighton. She’s decided to stay on for an extra day. According to her friend, she’s having a whale of a time.”

“Friend?”

“The person who called.” Dolly sounded as if she’d realised she had said too much.

“Was it a man or a woman?”

Dolly hesitated. Johnny let the silence build.

“A man. At least I think it was a man . . .”

“Did he give a name?”

“No. I was so pleased to get some news, I didn’t ask. This heat’s making me even dafter than usual. We’ll most likely get all the details when she comes home tomorrow.”

“Tomorrow? So you don’t want me to speak to the police?”

“There’s no need. Ah, the brewery’s arrived. I’ll say one thing for this summer – it ain’t half giving folk a thirst. Bye, Johnny. I’ll get Stella to call you as soon as she gets back.”

He sat at his desk, nonplussed, staring into space. His initial relief and gratitude that Stella was all right gradually gave way to disquiet and irritation. Why hadn’t this mystery man called him? Stella must know he’d be going out of his mind. Why hadn’t she called her parents and the bank herself? And why weren’t her parents more concerned about the stranger who was apparently keeping their daughter company? No doubt they would interrogate her when she eventually returned home. In the meantime, though, it was unlike Stella to be so thoughtless. Something wasn’t right. What was she hiding?

A large pot-belly blocked his view.

“What’s this about a rotten bit of woman?” Patsel mopped his brow. There were already two dark circles under the arms of his starched shirt.

“Help yourself.” Johnny nodded at the box that was still on his desk. His boss didn’t need a second invitation. He lifted the lid with all the glee of a child opening a present on Christmas Day. What he found seemed to fill him with both disgust and delight.

“Have you any inkling of who this once belonged to?”

“I’m not a clairvoyant. What d’you want me to do? Read her palm?”

“Ha ha! You are joking, yes?”

“Sort of. Why would I – how could I – know who this woman was?”

“I’m sure you know lots of painted ladies.” Patsel’s lips curled as he surveyed the bloated fingers. Johnny’s colourful sexual history had long since earned him the nickname “Stage Door”.

“Nail polish isn’t a sign of moral degeneracy – at least, it isn’t in this country.”

“Why send flowers to you?” Patsel picked up the card and read out the quotation. “Rabindrath Tagore.”

“How on earth d’you know that?” Johnny was seriously impressed. He would never have guessed that Patsel read Indian poetry.

“It is on a tea-towel in my wife’s kitchen.”

“I see.” Johnny was relieved that the German’s philistine reputation remained intact. He had no wish to start respecting him. “I’m as mystified by this as you are. However, I believe the same person also sent me this.” He retrieved the postcard of Saint Anastasia from the drawer in front of him.

“Beauty is not in the face,” recited Patsel in a singsong voice. “Beauty is a light in the heart.” He gave a snort that befitted his porcine features. “Pure schmaltz. Still, let us hope you receive soon another gift.”

“Well, I don’t,” said Johnny. “Why on earth would you want someone else to be mutilated?”

“This is a godsend, no? A great story has been handed you on a plate – or rather in a box. You need to track down the rest of the body and identify it.”

“The police are on their way. They want a statement from me. Meanwhile, my item on the jumper at St Paul’s has produced a widow. I’m going to see her later this morning.”

“Sehr gut. Well done, Mr Steadman. Keep me informed.” The German’s eyes continued their inspection of the newsroom. “Mr Dimeo! Feet off the desk, please!”

Johnny wrapped up the box, stowed it under his desk, then – glad to put some distance between himself and the unwanted gift – went over to where all the newspapers of the day were displayed on giant book-rests. He always kept an eye on what his rivals were up to: Simkins, for example, in the Chronicle, was exposing, with characteristic relish, a Tory MP’s penchant for nudist holidays. The article would no doubt induce another fit of apoplexy in his long-suffering father, the Honourable Member for Orpington (Conservative). Good.

As he flicked through the pages, ink smearing his fingers, his mind returned to the gruesome delivery. There was one person who did have easy access to body parts: Percy Hughes. The unprepossessing young man, one of Johnny’s secret informants, was an assistant in the mortuary of St Bartholomew’s Hospital. Johnny still suffered an occasional nightmare in which he was trapped in one of the morgue’s refrigerators while Hughes played with the corpse of his mother.

It was half past eight already – and there was still no sign of the police. If he left the office now he could call on Hughes before he went to Moor Lane police station. It was tempting. The arm would stay put, but Mrs Callingham wouldn’t. He didn’t want to miss her – somebody else might get to her first.

Instinct told him there was more to the story than a freak accident. Besides, from the crime desk’s point of view two dead men took precedence over a single unidentified body part. Matt would be more than displeased, but what did he expect him to do? Sit here twiddling his thumbs? He had waited half an hour – well, almost. Johnny grabbed his jacket.

The lift door opened to reveal a towering police constable and an equally tall man in a dark suit. Johnny had not set eyes on either of them before.

“The newsroom is to your right gentleman,” said the lift-boy. Johnny, avoiding their gaze, stood aside to let the two men pass. He didn’t breathe out until the concer-tina door was closed again. The boy just stared at him.

“What are you waiting for? Get me out of here.”

“Been naughty, have we? Don’t you like bluebottles or red roses?”

“Mind your own business.”

“You do know they’re here to see you?”

“Indeed. I’ll catch up with them later. Don’t worry, I’ll see that you don’t get into trouble.”

The youth, who would be quite good-looking once his acne had cleared up, sniffed.

“Ta very much – but don’t go out on a limb for me.”

Chapter Six (#ulink_96adc0ac-eccc-535f-8a8e-fd8ab43164e8)

Johnny, pushing his luck, stuck his head round the door of the switchboard room. It was stifling. A dozen young women, plugging and unplugging cables, intoned “Daily News, good morning”, “One moment, please” and “Connecting you now.”

“I’ll be out of the office for a couple of hours, girls.” He was answered by a chorus of wolf-whistles and cat-calls.

“Hello, Johnny!” Lois, a suicide blonde old enough to be his mother, winked at him. “When are you taking me out for that drink you’re always promising me?”

“The next time I get jilted.”

“And what, may I ask, d’you think you’re doing?”

Johnny jumped. He could feel hot breath on the back of his neck. He turned round. The basilisk eyes of Doreen Roos locked on to his. “Mr Steadman, I might have known it was you. You know very well that reporters are not allowed in here.”

“As you can see, I haven’t actually crossed the threshold.”

The supervisor tut-tutted in irritation. “Why can’t you phone down, like everyone else?”

“I was in a hurry.”

“Well, don’t let me stop you.” She stood aside to let him pass.

“Bye, Johnny!”

“Bye, girls. I’ll bring back some lollies.”

“Oh no, you won’t,” said Mrs Roos. Food was strictly forbidden in the exchange.

Johnny slung his jacket over his shoulder and, with a nod of sympathy to the doorman sweating in his long coat and peaked cap, went out into the swirling heat and noise of Fleet Street. No one wanted to walk in such oppressive weather. It took him five minutes to find a cab. The breeze coming through the open windows as it trundled up Ludgate Hill – St Paul’s straight ahead – provided scant relief.

He got out of the taxi across the road from The Cock and entered the courtyard of the hospital by St Bartholomew-the-Less. A father fondly watched his child playing in the fountain at the centre. Such scenes moved Johnny. Would a father’s love have made him turn out differently?

It was cool in the basement. A tunnel connected the main block to the mortuary at the back. Before it was built, the dead would have been wheeled across the courtyard with only a sheet to protect them from prying eyes.

As he approached the double-doors of the morgue the pungent smell of disinfectant grew stronger. Johnny peeped through one of the round windows and saw the back of the duty pathologist, bending over the naked body of an old man. Hughes, his assistant, looked up and blanched. He said something to his superior, pulled a curtain round the dissecting table, and, with a scowl, came out to join Johnny.

“What’s the matter? You look like you’ve seen a ghost.”

“I was hoping I’d seen the last of you.” Hughes tossed his lank, greasy hair away from his face and wiped his bloody hands on his apron. “What you want?”

“Don’t be like that. Haven’t you missed me just a teensy-weensy bit?”

“No.”

“I bet you missed my money, though.” Johnny nodded towards the pathologist. “Does he know about your little sideline?”

Hughes ignored the question.

“I haven’t got all day.”

“Be like that then. I just came by to thank you for your little gift.” Johnny studied the lugubrious thug carefully.

“Dunno what yer talkin” about.”

“So you’re not short of a woman’s arm? Nothing’s gone missing recently?”

“Dunno what you mean.”

“Someone sent me the forearm of a woman this morning.”

Hughes curled his lip – in amusement rather than distaste. “Well, it weren’t me.”

“Sure about that?”

“Sure as eggs is eggs.”

“OK. I believe you.”

“Why would anyone do such a thing? It’s sick.”

Johnny suspected the attendant was no stranger to midnight perversions. “Indeed. That’s what I’m trying to find out.”

“Hughes – get back here this minute!” The pathologist rapped on the door and glared through the porthole. Whatever he held in the palm of his hand dripped on to the black-and-white tiled floor.

“I assume I can count on your discretion,” said Johnny. “I don’t want anyone else stealing my thunder.”

“Your secret’s safe with me. And if I hear anything about missing body parts, I’ll give you a bell.”

“Thank you. I’ll be more than generous.”

The butcher’s boy slipped through the doors and disappeared behind the green curtain that hid the outspread, opened corpse.