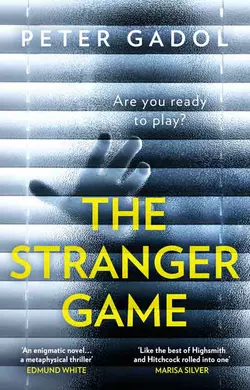

The Stranger Game

Peter Gadol

Are you ready to play?‘An enigmatic novel . . . a metaphysical thriller’ Edmund White‘Like the best of Highsmith and Hitchcock rolled into one’ Marisa SilverRebecca’s on-again, off-again boyfriend, Ezra, has gone missing, but when she notifies the police, they seem surprisingly unconcerned. They suspect he has been playing the ‘stranger game,’ a viral hit in which players start following others in real life, as they might otherwise do on social media.But as the game spreads, the rules begin to change, and disappearances are reported across the country.Curious about this popular new obsession, and hoping that she might track down Ezra, Rebecca tries the game for herself. She also meets Carey, who is willing to take the game further than she imagined possible.In playing the stranger game, what leads Rachel closer to finding Ezra will take her further and further from the life she once lived . . . A compulsive, inventive thriller for fans of The Girl Before, Little Deaths and The Book of Mirrors

A literary suspense novel in which an eerie social game goes viral and spins perilously—and criminally—out of control.

Rebecca’s on-again, off-again boyfriend, Ezra, has gone missing, but when she notifies the police, they seem surprisingly unconcerned. They suspect he has been playing the “stranger game,” a viral hit in which players start following others in real life, as they might otherwise do on social media. As the game spreads, however, the rules begin to change, play grows more intense and disappearances are reported across the country.

Curious about this popular new obsession, and hoping that she might be able to track down Ezra, Rebecca tries the game for herself. She also meets Carey, who is willing to take the game further than she imagined possible. As her relationship with Carey and involvement in the game deepen, she begins to uncover an unsettling subculture that has infiltrated the world around her. In playing the stranger game, what may lead her closer to finding Ezra may take her further and further from the life she once lived.

A thought-provoking, haunting novel, The Stranger Game unearths the connections, both imagined and real, that we build with the people around us in the physical and digital world, and where the boundaries blur between them.

PETER GADOL’s six novels include Silver Lake, Light at Dusk and The Long Rain. His work has appeared in journals such as Tin House, StoryQuarterly, Story, Bloom and the Los Angeles Review of Books. A former NEA Fellow, Gadol lives in Los Angeles, where he is chair of MFA Writing at Otis College of Art and Design.

PeterGadol.com (http://PeterGadol.com)

Also By Peter Gadol (#u37ffbc79-453e-5acc-8861-f754a868840e)

Coyote

The Mystery Roast

Closer to the Sun

The Long Rain

Light at Dusk

Silver Lake

The Stranger Game

Peter Gadol

Copyright (#u37ffbc79-453e-5acc-8861-f754a868840e)

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2018

Copyright © Peter Gadol 2018

Peter Gadol asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © October 2018 ISBN: 9781474092975

Advance Praise for The Stranger Game

“‘Following’ gets a whole new meaning in Peter Gadol’s stylish psychological thriller set in the future of the day after tomorrow. A moody, increasingly dangerous house of mirrors where the rules morph as his players become more obsessed with ‘the stranger game.’”

—Janet Fitch, author of White Oleander and The Revolution of Marina M.

“The Stranger Game is a gripping and nuanced novel that asks whom we trust and why. It is about being an insider and an outsider, about being watched and finally being truly seen.”

—Ramona Ausubel, author of Sons and Daughters of Ease and Plenty and No One Is Here Except All of Us

“The ingenious conceit of Peter Gadol’s novel—to literalize our obsession with online following—yields a psychological thriller that brilliantly exposes the state of the culture, one in which we have traded authentic emotional connection for a virtual one whose implications for the soul are troubling. Like the best of Highsmith and Hitchcock rolled into one, The Stranger Game is a compulsively absorbing and thought-provoking triumph.”

—Marisa Silver, author of Little Nothing and Mary Coin

“If you’ve ever spent time people watching, or if you yourself have ever felt watched or followed, you’ll see yourself in Peter Gadol’s The Stranger Game—and it will unnerve you. This is the perfect novel for a world in which real human connection is so elusive.”

—Will Allison, author of Long Drive Home

“Imagine a metaphysical thriller inspired by Patrick Modiano and illustrated by Giorgio de Chirico and you’ll have an idea of this enigmatic novel, The Stranger Game.”

—Edmund White

For Chris

Somehow never strangers

Contents

Cover (#u7e8a1042-fdd7-5284-bfad-27040a9b513c)

Back Cover Text (#u0d376587-b1f6-53fd-81f1-60e4f17d49f1)

About the Author (#u290688c3-68be-5229-a94b-b79276de0413)

Booklist (#ua3e1642c-83c1-5896-8188-ea214e5d5dad)

Title Page (#udcd705de-a409-526a-b86f-5fb8f23c1d2e)

Copyright (#ufdf6a2a8-1368-5f99-80d8-0af14ec770b3)

Praise (#ua9d02b38-9848-5382-93e8-7680e2a78d2b)

Dedication (#ud21151a2-0fde-5bcd-aa5e-b56401a42fe4)

1 (#u2e9104c5-81de-5977-b803-cd932ea280df)

1-1 (#u1bfa7297-7f58-50be-8ddf-d4d85f02b579)

1-2 (#u8e8dfb9b-ded7-5cca-81f2-33e5489d685b)

1-3 (#u76d78b63-dffe-5a6f-9222-dbdf88134d80)

1-4 (#u7524693e-c564-592d-9266-f3835175a60f)

1-5 (#ub7624112-62fd-56b0-88f1-19f4f3b3b030)

1-6 (#ue4bc5a7b-d1b6-5071-adc6-bb416340330d)

1-7 (#litres_trial_promo)

2 (#litres_trial_promo)

2-1 (#litres_trial_promo)

2-2 (#litres_trial_promo)

2-3 (#litres_trial_promo)

2-4 (#litres_trial_promo)

2-5 (#litres_trial_promo)

2-6 (#litres_trial_promo)

2-7 (#litres_trial_promo)

2-8 (#litres_trial_promo)

2-9 (#litres_trial_promo)

2-10 (#litres_trial_promo)

2-11 (#litres_trial_promo)

3 (#litres_trial_promo)

3-1 (#litres_trial_promo)

3-2 (#litres_trial_promo)

3-3 (#litres_trial_promo)

3-4 (#litres_trial_promo)

3-5 (#litres_trial_promo)

3-6 (#litres_trial_promo)

3-7 (#litres_trial_promo)

3-8 (#litres_trial_promo)

4 (#litres_trial_promo)

4-1 (#litres_trial_promo)

4-2 (#litres_trial_promo)

4-3 (#litres_trial_promo)

4-4 (#litres_trial_promo)

4-5 (#litres_trial_promo)

4-6 (#litres_trial_promo)

4-7 (#litres_trial_promo)

4-8 (#litres_trial_promo)

5 (#litres_trial_promo)

5-1 (#litres_trial_promo)

5-2 (#litres_trial_promo)

5-3 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1 (#u37ffbc79-453e-5acc-8861-f754a868840e)

THE FIRST TIME I FOLLOWED ANYONE WAS ON A SUNDAY AFTERNOON in late November, the sky still gray with ash some weeks after a wildfire to the north. I had gone out on a hike, hoping to clear my mind by scrambling up the narrow path of a dry canyon, which worked until I walked the down trail back to my car. As I was driving out of the park, I passed a picnic area where there was a party underway, a birthday celebration with a hacked-at piñata twirling off a low branch, smoke rising from blackened grills, balloons tethered to the benches. At the periphery, I noticed a little boy, himself a balloon in a red, round jacket and red, round pants. He didn’t seem to be the center of attention, so I didn’t think he was the birthday boy. He must have been about three. He was tossing an inflated ball, also red, back and forth to his parents, or not exactly to his parents. He launched the ball instead toward the road where I’d pulled over and parked. I hadn’t planned any of this, but then that was how the game was played, how it began, the first rule: choose your subjects at random.

The balloon boy picked up the ball and tried throwing it again, but he couldn’t seem to get it to either parent; it kept falling short. Why didn’t they stand closer? Why were they making it difficult for him, was this some kind of test? The boy began flapping his arms, exasperated, until mercifully his mother pulled him aside for a hot dog. The boy’s father accepted a beer from another man. Trying to persuade the boy to eat was apparently the wrong move because he shook his head from side to side, cranky right when the afternoon sun both cracked the clouds and began to fade.

The boy’s mother scooped him up in her arms, although it looked like he was getting heavy for her, and carried him to a bright green box of a car parked three spaces in front of mine. Did she notice me? No, why would she? There was nothing so peculiar about a forty-year-old woman sitting alone in a gray car idling in a city park. Although that afternoon I was full of longing, and who really knew what I was capable of doing.

The mother fit her boy into a car seat, strapped him in, and brushed his hair off his face. The boy’s father had followed them to the car but didn’t get in. The woman turned toward him to give him a quick, meaningful kiss, and I heard the man shout as he walked away that he’d call her later when he got home, which elicited an easy smile from the woman.

I revised my story. She was a single mother, right now only dating this man; she’d brought her son to a party the man had said the boy might enjoy. The woman and the man had been seeing each other for six months, and he was the first guy in a long while who she felt was good with her son, better than the boy’s actual father. I should have been rooting for them, for their happiness, but I wondered: If the woman and man wound up together permanently, would he be one of those guys who believed their marriage wouldn’t be complete until she gave him a child of his own? How would the woman’s son handle it? Would the challenge of a new sibling prepare him for all of the other uncertainties ahead, his body changing, the girls or the boys he’d want to take to his own picnics, the inevitable dramas of his own making? Would he continue wearing red jackets with red pants? Would he come into his body as an athlete, or would he excel at piano or math or debate, or all of the above—no, something else, but what?

These were the questions I was asking while trailing the green car out of the park and east along the boulevard, then south, skirting downtown. Traffic gave me cover, but it also meant I had to drive aggressively if I didn’t want to lose them. There was an unexpected pleasure in trying to remain unobserved while in pursuit.

Twenty minutes later, we ended up on the east side of the river heading into a part of the city I didn’t know well, and as traffic thinned, it had to be obvious I was behind them. Did the woman see me in her mirror? Did she call her boyfriend and chatter for the sake of it, keeping him on the line in case she needed to tell him a woman wearing dark glasses was following her home?

We were coasting through a newer development, the streets as flat as their map. When the woman turned into a driveway, I continued on and pulled over at the end of the block, five houses away. Now I watched them in my side-view mirror: the woman helped the boy out of the back seat, and she was trying to gather their things and order him into the house, but he was having none of it, sprinting across the yard toward its one leafless tree. Then the boy tripped. He fell first on his knees, then his palms. He wailed.

The woman jogged over and knelt down next to him, righting him, shaking her head, neither angry nor concerned. It wasn’t a bad fall. She reached her arms around him and once again she brushed his bangs across his forehead. The boy probably had learned that the longer he wept, the longer his mother would hold him, and so he kept crying. His mother rocked him—and was she smiling? How long would she be able to comfort him like this, her silly boy? I wondered what it was like to be needed in this way, and to know it was a fleeting dependence. The autumn sky turned amber with the last trace of light.

Suddenly from the open back door of the woman’s car, the red ball fell out. It rolled all the way down the driveway to the street. Neither the woman nor her son appeared to notice. The breeze carried the ball down the grade toward where I was parked. My first instinct was to hop out and retrieve it and bring it back to the boy, but then I would have revealed my position and possibly alarmed the woman if she put together how far I’d followed her. Also I would have broken the second rule of the game: no contact.

The red ball continued to roll down the middle of the street, pushed on by the evening wind. Would the boy ever find it? Would his mother notice it missing? Was it lost for good? I would never know. I would never see them again. The third rule of the game was never follow the same stranger twice, and so I drove away.

I PREFERRED TO BE IN MY SMALL TIDY HOUSE AT NIGHT RATHER than during the day because after dark I was less apt to notice whatever I might have been neglecting, the settlement cracks along the ceiling edge or the chipped bathroom tile. No matter the hour though, there was no avoiding the long wardrobe closet I could never fill on my own or the open corner of the main room once occupied by a plain birch writing desk. Then there was the garden all around the lot that existed in a state of permanent disgrace. My ex-boyfriend had been the one who tended to the knotty fall of chaparral down the back slope, although when Ezra moved out, he promised he would come by and take care of this plus the dozen succulents he’d potted during a period of unemployment; he did at first, but then stopped. I noted in my datebook to drench everything every five days. I’d probably overwatered the poor things until they gave up on me. I’d never wanted to own a house by myself, let alone tend its garden. That wasn’t the plan. I’d bought the house with marriage in mind. Here was the kitchen where we improvised spice blends, our mortar and pestle verdantly stained; here was the couch where we read aloud to each other the thrillers neither one of us read on our own; here was our bed, our weekend-morning island exile.

I was in a strange mood when I got back from following the woman and her son. I took a bottle of wine out back. High up on the hillside looking west, the city lights looked like an unstrung necklace, the basin covered with bright scattered beads. I kept picturing the way the little boy leaned into his mother, crying, comforted. I thought of myself as someone who would have the capacity to be a good parent to a happy-go-lucky kid, and there was a time when Ezra and I talked about getting pregnant or more likely adoption. Adoption wasn’t something I saw myself doing alone; friends did it solo, admirably and well, but that wasn’t for me.

I drank the wine fast and poured myself another glass. As I understood it, playing the stranger game was supposed to help you connect (or reconnect) in the most essential way with your fellow beings on the planet, help you renew your sense of empathy, yet I was only left lonelier that night. We were living in dark times, season after season of political uncertainty and social unrest; solitude only amplified my anxiety about the future. Ezra used to have a way of calming me down, and when I was with him (and when he was in one of his loftier moods), I believed progress was still possible, that together we (he and I, all of us) would prevail against the forces that would undo what we believed in. But Ezra was gone. He’d disappeared two months earlier. I missed him even more than I did after the final time we broke up.

A brief history: We had been friendly in college and shared meals but never dated. We took an art history survey together and then another course on modern movements, and I probably resented the way everything came to him so effortlessly, good grades, girls smarter than him. I didn’t take him seriously. Two summers after graduation we re-met at a rooftop party. I was in graduate school and Ezra was copyediting at a magazine. We stood off in a corner and made up stories about the guests we didn’t know. And we always did that, I have to say, long before it became part of any faddish game, which was hardly original, which was something people have always done while loitering in cafés and airport lounges or riding trains. Ezra and I were the same height, both short, which made whispering in each other’s ears easy. Right away I knew I’d always crave his breath against my neck. Unlike the men I’d been with before, he didn’t become some other animal when we made love later that night. He was playful, open, but also it was clear he had his secrets, fish sleeping beneath the surface of a frozen lake. Unlike the men I’d been with before, he wasn’t so easy to figure out, and I will admit that was what initially drew me to him.

We started taking road trips up the coast. We were curious about the same things, figurative painting, slow-cooked food, small towns far from other small towns. And yet we were also very different people. Ezra often wanted to be alone; I never did. His long black hair had a way of hiding half his glance; I usually pulled mine back into a ponytail. When he didn’t shave for a week, it seemed like he was hiding something. I’m grasping for some way to describe what I later understood better from a distance, and I’m dwelling too much on his appearance, although I was very attracted to him and wanted nothing more than to be close to him. His weeklong scruff was soft to touch.

That first morning after the rooftop party, we lay in bed with the blankets thrown back because the radiator was too aggressive. We had nowhere to be. We had all the time in the world for each other. When I was growing up, my father with his aches and pains often told me to enjoy my good health while it lasted and not take it for granted, but maybe the thing we really take for granted in our youth is time: back then an hour lasted longer, each day was epic.

We dated for a couple years and talked about moving in together but never did. Then there was a problem with my lease, I was going to have to move, and I pushed the subject, but Ezra said us sharing an apartment would never work. Never? I asked. As in never ever? My degree was in architecture, and all the way across the country there was a position at a firm that specialized in transforming old factories and warehouses into magnet schools and cultural centers, exactly the kind of work I most wanted to do. When I told Ezra about the job, he said I should go for it if I really wanted to, but he wouldn’t follow me out. His declaration came without elaboration and astonished me. We had a bitter fight; he accused me of plotting a course for myself while assuming he’d just fall in, independent Ezra who was sensitive about not getting anywhere in a career of his own. I think I was hurt to the extent I was because his accusation rang true. I applied for the job and got it.

After I moved, Ezra and I stayed in touch; we talked every couple of weeks, and one day my phone trilled with a text. Ezra had come west. He was near my office; in fact, he was at the museum down the street. More specifically, he was in the room with Madame B in Her Library, which he knew was my favorite painting, a tall early-modern portrait of a woman confined in a black buttoned-up gown yet grinning at the viewer with conspiratorial bemusement. The library was apparently invisible; the woman was painted against a brown backdrop with no books in sight. I didn’t believe Ezra was there. He texted back that there was only one way to find out.

He didn’t let go when he hugged me. His narrow shoulders, his veiny arms. His soft beard.

“Oh, Rebecca,” he said. “The biggest mistake of my thirty years was not following you out here.”

“We’re only twenty-eight,” I said.

“Whatever. I’m here now.”

“What makes you think I’d want you back?” I asked. “How do you know I’m not seeing someone?”

“You’re not.”

“You don’t know that. I don’t tell you everything.”

“You’re not,” he said again. “You can’t be.”

His breath warming my neck.

We lived together for eight years, at some point moving in to the house on the hill, using money my grandmother left me for a down payment. Those first two or three years in that house were the happiest of my life, a paradise to which I would struggle to return. Our last two years together, we argued frequently. I’d left my original job to form a studio with three partners, and we became busy entering every competition we could. We often worked late and through the weekend. Meanwhile Ezra wasn’t busy at all; he was always home waiting for me.

I kept up a stupid prolonged flirtation with one of my partners, who was married, which I am pretty sure Ezra never knew about while it was happening. My partner and I never had an actual tryst, and things cooled off, but my infatuation distracted me. The last year with Ezra was terrible. He kept saying he didn’t have a place in my life; he was a visitor. I’d tell him he was my life, but that sounded thin. I don’t have a place in my own life, he’d say, I’m a visitor there, too. I’d say that I didn’t know how to respond to that (or what he meant), and he’d snap: Why do you think you have to say anything? Some version of this conversation kept recurring. Then he’d say, I never wanted this house, it’s too much. I never wanted this garden, he’d say, or this view, and I’d say, You know that’s not true. You’re the one who always looked at the listings first. We weren’t making love. First tenderness left, then joy. When I got to my studio in the morning, I’d stretch out on a couch for a half hour with my eyes closed until I felt a yoke loosen across my shoulders. We agreed to try living apart for a time, although we knew this was less a trial than a prelude to our dissolution.

Ezra moved in to a small apartment up by the park and wanted to be free to see other people. He’d always been very sexual. I didn’t want to know about any of it, but eventually he told me when he came round to take care of the plants, and I didn’t interrupt him. The years fell away quickly, and we saw each other often; we were never out of each other’s lives. In many ways we grew closer again, confiding in each other once more, or, that is to say, he told me about the women he saw, none very seriously; I tended to tell him about my clients and projects. Ezra didn’t earn much as the assistant manager of the local bookstore, so I helped him out occasionally when he let me. He traveled with me to both of my parents’ funerals nine months apart. We met for dinner regularly, a movie sometimes. I cooked for him, he cooked for me. But I didn’t take him to dinner parties or events as my plus-one; he didn’t spend time with my friends. When we met up, it was always only the two of us. I never felt as centered as I did when I was driving back to the house on the hill after being in his company.

Whenever Ezra was involved with someone, we saw each other less. During these periods, I missed him but wanted him to settle down with someone new in a meaningful way. Only then would I be able to pursue my own happiness, then it would be my time; I can see now this was my thinking. The longest I’d ever gone without hearing from him was two weeks.

Two months ago in September, I hadn’t heard from Ezra for three weeks. I was busier than usual working on the conversion of a landmark insurance headquarters into a charter school. Something had happened between us—I won’t go into it—and I was trying to achieve some distance. When Ezra didn’t answer a series of texts, I thought, Well, I hope I like her.

Another week went by, and he still wasn’t answering my texts or calls, and I became worried. I dropped by his apartment. When I was knocking on his door, the property manager stepped out and said she assumed Ezra had gone away because he had missed his rent. This was very unusual. Weirdly though his car was still in his garage—she’d checked that morning. Ezra had known some dark days, and I didn’t think his depression ever became so unbearable that he’d harm himself, but I panicked. I had my key out before the property manager grabbed hers.

The wool blanket I’d given him for his last birthday was neatly folded across his made bed. Pillars of art books doubled as night tables. Ezra’s clothes, shoes, and luggage were in his closet. He had always been neat. The dishes were put away, but there were some salad greens going bad in the refrigerator. There was a stack of bills and magazines on his writing desk along with a fat biography of a poet bisected by a bookmark and a mug marked by rings of evaporated coffee. And next to the mug and the book was a printout of an article: it was the essay that had launched the stranger game.

THE DAY AFTER I’D FOLLOWED THE WOMAN AND CHILD HOME from the park, I went into the office early to work on some renderings but had difficulty focusing. For a change of scenery, I walked to the museum at noon and slipped into an exhibition of recent acquisitions by younger artists. The very first patrons I noticed were two men standing in front of an expansive abstract painting of layered squares, off-whites floating over delicate blues floating over earthy browns. The work looked like a painting but was actually a collage of ephemera—boarding passes, sales receipts, postcards, circulars—all of which were sanded into one smooth plane and drenched in resin. It was unusually beautiful. I observed the two men. One was tall, scantily bearded, wearing steel glasses; the other was younger, tightly packed into his sweater and slacks. Both of them admired the work, too, as far as I could tell. I stepped closer and stood with my back to them, facing a kanji-shaped cardboard sculpture.

The taller and older man solicited the younger man’s reaction: What did he see? A landscape, the younger one said. Hills rising in the distance, like when one looked north in the city—do you see it? Hills spackled with low-lying homes. He speculated about how it was made, and the older one recalled something useful about decoupage, then chuckled. He said he didn’t know what he was talking about, he was talking out of his ass, which (I noticed when I looked over my shoulder) prompted the younger one to pat the taller man’s behind. They were new lovers, I decided, and it was the younger one’s idea to spend a day off at the museum because the older one had written in his dating profile that he felt equally at home in museums and sports arenas, and the younger one had said, Well, let’s see about that. Should we start with an exhibit or go to a basketball game?

They continued holding hands as they shifted left toward the next work. I slipped in front of the collage. The younger man had a way of tipping back his head in laughter no matter what the older man said. The older man—older by fifteen years?—gestured with his free hand, making ever-wider enthusiastic circles and then, suddenly, pointing at one corner of a photograph. The younger man was looking first at his new boyfriend, then the sleepy portrait of a teenager slouching back on a bike seat. These roles were fine for now, mentor and acolyte, but what would the younger man teach the older one to keep things even? Here, listen to this song, I love this band. Hey, let’s go camping in the desert next weekend, you did say you’d go camping.

The men were quiet when it was only the three of us in the elevator, me staring the whole time at my shoes, and I wondered if with this proximity I was breaking the no-contact rule, even though I said nothing, never met their glance, and preserved a safe distance following them out of the building and into the courtyard. I waited one stoplight cycle before crossing the street after them and assumed I’d lose them, but they were easy to find checking out the food trucks, settling on the one selling healthy salads. I didn’t actually want the sesame noodles I bought one truck over.

There wasn’t anywhere to sit, so the two men crossed back to the museum plaza and perched at the edge of a planter. For now they were protected in new romance, but maybe the older one had been single so long, he’d become set in his ways, and he was annoyed by a flaw he’d observed lately in the younger man, that he refused to acknowledge when he didn’t know enough about a topic (especially politics), because he probably thought expressing a strong opinion was better than offering no opinion. All of our lives were chaptered, which the older man knew well enough; maybe the younger man did, too. But if the older man was writing his fourth or fifth chapter, and the younger only his second, would they last together?

Memories now: Ezra and I making out in an apple orchard when we were twenty-four. Napping in the afternoon in a hotel abroad, a late plate of pasta, red wine, willfully getting lost in the canal city at night. Ezra the easily distracted sous chef unevenly dicing shallots, more interested in amusing me with an account of his day, the crazies who had come into the store, how he’d write them into the novel he’d never finish because there was always so much to add. Ezra coaxing James the Cat down from our one tall tree in front (James was first my cat, then our cat)—Ezra cradling James toward the end, knowing we’d have to put the poor guy down. Ezra the troubled sleeper, slipping back into bed after a four a.m. neighborhood walk, thinking I wouldn’t notice, but how could I not notice? I’d pull his right arm over me and hold it and say, You’re not going anywhere now—

My phone vibrated in my pocket, our studio assistant reminding me about the conference call with contractors that I was now late for. And then I noticed the older man staring over at me. I was playing the game all wrong. I had neglected my subjects. I hadn’t observed them closely enough to forge a connection. They remained elusive, and instead of trying to achieve greater empathy, I had waded into my own reverie.

As I headed toward the street, I looked back one more time: the two men were standing now, giggling about something, the younger one tipping back his head, the older one with his right hand pressed flat against the younger man’s stomach, then patting his abdomen. You, you’re impossible, come on, let’s get you something else to eat, and I could use a glass of chardonnay—what? It is not too early. Let’s get you a sandwich and both of us some wine and we can sit and watch everyone go by—now, how does that sound?

THE ESSAY I FOUND ON EZRA’S DESK HAD RUN EIGHTEEN MONTHS earlier in an online journal known for its literary travel writing, much of which was posted by guest contributors. It immediately went viral. Usually the articles were accounts of glacier hikes or reef dives; there were columns about what to see when you only had three days in a river city, that sort of thing. This particular essay—the author’s bio stated only “A. Craig is a pseudonym”—read unlike any other filed under the rubric Road Trips. It was titled “Perro Perdido.”

Late in the autumn of my life, I came to the realization that I did not like myself very much. I had been teaching literature at the same college for thirty years and not written a new lecture in half that time, my disengagement only surpassed by that of my students. For many years my research sustained me, but the midcentury realist authors whom I once cherished and to whom I was forever linked as a scholar had become odious tenants whom I seemed unable to evict. My romantic life was likewise jejune. My very last affair ended unceremoniously while driving home from a party. I was doing what I always did, which was to run through all of the new people whom we’d met, issuing an acerbic group critique. The too-tight skirts, the pop politics, the overall idiocy and decline of serious reading. I was especially good (I thought) at mimicking voices and was mocking someone’s recitation of her weekly cleansing routine when my girlfriend said, Stop it, please. Why do you always have to be so mean about everyone? But I’m only trying to amuse you, I said. Well, stop it, my girlfriend said, it’s getting old. But I pushed it and said, Oh, come on, you love it when I—No, she said. I don’t know why I ever encouraged you. Stop, please, she yelled again. I said stop! By which she meant stop the car. I’m suffocating, she said, I need air. She got out and walked off into the darkness. I never saw her again.

So I found no fulfillment in my work, experienced increasingly briefer runs at dating, and also diagnosed myself as the kind of snob I’d loathed as a younger man. Jogging in the park in the morning, I became inordinately irked by the women who nattered away on their cell phones while speed-walking, by the men who wore sunglasses even when it was cloudy; I found myself interrupting colleagues during meetings to correct their pronunciation of ex officio (It’s Latin—with a hard C, please); I looked down on the drivers of luxury sedans and mothers in parks with sloppy toddlers and overweight people eating ice cream.

The truth was I was achingly lonesome. I would come home to the house I’d once upon a time hoped to share with a lifelong lover and keep as few lights on as possible to avoid feeling overwhelmed by the rooms that needed repainting and the warped cabinets and the general lack of wall art. How lonely and alone I was, drinking, masturbating, drinking more until I fell asleep in front of cooking shows. At least in the morning I had my routine, somewhere I needed to be, a position of some respect. Then the worst possible thing happened: I came up for a sabbatical, and because I was entitled to it, I took it.

I winced when I read about Craig’s relationship to his house. It was easy enough to picture him padding around empty rooms, with too many hours he couldn’t fill, with no plan for his time away from his college. He wrote that he slept in later and later each day. He started going to neighborhoods in the city where he wouldn’t run into anyone he knew and where he could sit in cafés for hours and solve crosswords. He noticed he wasn’t the only one in any given coffee shop staring at a book without turning the pages. When he stopped off at the grocery store on the way home, he stood in silent confederacy with the other people purchasing single portions of lasagna from the deli. This, too, sounded familiar.

One evening, Craig continued, he realized that besides ordering his coffee from a barista, his only interaction of the day was helping a woman retrieve a box of chocolate chip cookies from a top shelf, and it occurred to him, given how chatty she was, that quite possibly it was also one of the few interactions she’d had, as well.

It made no sense. A city full of people: Why was there loneliness everywhere I looked?

The next day I walked down the hill from my house to a taco stand on the boulevard. My order was ready right at the same time as the one put in by a young woman, and I took a step back and pretended to inspect the contents of the bag I had been handed, although what I was doing was staring at her, unable to avert my gaze. She was wearing a plaid jacket, a striped skirt of an entirely different palette, and leggings printed with an animal pattern. What a mess. And, oh, her hair; her hair was a feathery fuchsia that reminded me of one of those trolls you hoped you didn’t get when you inserted a coin in a boardwalk vending machine—

Stop it, I told myself (hearing my ex-girlfriend in my mind). Why did I need to be so dismissive? The woman had style, or a style, and maybe (no, definitely) it didn’t appeal to me, yet she probably liked the way she looked or she wouldn’t be parading around in this outfit, drawing the gaze, I noticed as she walked away, of both a man walking a spaniel and the spaniel.

I followed her.

She had perfect posture, a dancer’s line. Her feet were turned out while she waited for a light to change. Where did she get the self-confidence to put herself together like this?

Even though she was holding the bag with her tacos in it, the woman turned into a vintage dress store. I stood on the sidewalk but watched her inside examining a long beaded frock (quite a different look than what she had on). I pretended to be looking at my phone when she exited the store and continued down the block. I followed her past a vegan café, past another boutique. She went into a store that sold barware and pricey liquor. This time I went in, too, and pretended to sort through an ice bucket full of novelty stirrers. The woman headed straight for the bourbon in the back. She asked a clerk for help—her voice was a round alto, and she had an accent: Could you by chance recommend a good earthy bourbon?

Then she finally glanced over at me ever so briefly, long enough for me to notice her eyes, pure sapphire, and I thought if you’re born with eyes that vivid, you will probably be attracted to bold color your whole life. I wanted to keep following her, but what if she saw that I was also carrying a bag from the taco stand? I did not want her to feel like I was stalking her even if that was exactly what I was doing.

I thought about her all afternoon. Had she come to this country alone? Did she have someone in her life with whom she could share tacos? Carnitas for you, pollo for me. What color was his hair? How did he dress? I decided she had done some modeling because she was tall and her look probably held marketable appeal. But the modeling career, it was a sideline, a way to earn money while she pursued her greater ambition—which was what? I could make up something: she wanted to front an all-girl band, she wanted to get a psychology degree and work with at-risk teens—but the truth was I didn’t have enough information to get a sense of who she was in the world. At first I’d wanted to write her off because she looked clownish, but now I yearned to connect to her, however tentatively, even at a distance.

Let’s mark this as the moment when I recognized that a transformation in my life was not only possible, but also, remarkably, within my reach.

The day after following the fuchsia-haired woman, Craig walked down the hill to the taco stand at approximately the same time, although he knew the chances were slim that he’d find her again. Instead someone else caught his attention, two people, an elderly couple across the street. The man was quite bundled up given the warm weather, a sweater pulled high around his neck, and he moved stiffly around a small cherry of a car to where the woman was standing. It seemed reasonable to assume they were married. The woman appeared both serene and distant. She was wearing a knit cap. She didn’t look the man in the eye when he opened the passenger-side door for her and eased her into the seat. Craig noted the tenderness with which the man, still moving very slowly, reached across the woman to buckle her safety belt. Then the man took half an eternity to walk around the car and slip in behind the wheel. Eventually he sped off, and not at a pace commensurate with his mobility; he drove fast, dangerously fast, as if with the potential speed of the car, the man were compensating for his diminished agility. This sporty coupe, impractically low to the ground, devilishly bright, was affirmatively alive with horsepower.

At home that night, I found myself thinking only about the fuchsia-haired woman and the sports car couple, and I experienced the pleasant erasure of time that I always imagined writers must enjoy when they submerged themselves in their characters. But eventually my own solitude returned. How faint and spectral I looked to myself reflected in the window. I didn’t want to become a ghost. I knew I needed to get out and wander. This was how I came up with my scheme, rules and all.

I imagine that given what A. Craig subsequently started doing, no matter the boundaries he set and no matter his intent in posting this so-called travelogue, he knew most readers would consider him little more than a sketchy voyeur; thus the pseudonym. His first real follow (his term) involved driving across the city and slipping into a table at a boardwalk café, the ocean loud on the other side of the wide white beach.

It was sunny out, and there were volleyball games in progress, skaters in slalom around tourists, sunbathers, and most important a crowd ample enough for me to become one more nobody. I ordered a sandwich and coffee and watched a group form around a gray-haired older woman wearing a red bikini and performing what might be described as an exotic dance; a muscular, significantly younger man with a boom box hoisted up on his shoulder moved in a circle around her. I focused on one woman in a purple dress standing at the edge of the group and taking in the spectacle. That I picked out this person at random and stuck with her was part of my plan.

When she began continuing her walk south down the boardwalk, I left cash on the table and followed her, moving quickly out of the touristy commercial stretch into a neighborhood of beach houses and walk streets. The crowd had thinned, and so I had a better view of her, but I also became more conspicuous, especially when she abruptly came to a halt and I had to stop, too, with nothing to duck behind.

The woman had spotted a cat basking in the sun. The cat was round, cared for, orange, on its back. And docile: it neither righted itself nor skittered off when the woman bent down to pet it. After a few good strokes, the woman pulled something from a tote bag, which caused the cat to flip around onto all fours and sit back on its haunches. The cat dug his snout into the woman’s open palm and devoured what must have been a treat. When the woman stood, she waited while the cat rubbed up against her legs.

I maintained an even distance as the woman turned into a block of bungalows. A few houses in, she saw a gray cat lying out on a broad porch, and she walked right up the front path to pet this one, too, a cat who also did not run away, who also eagerly accepted the woman’s caresses and eventual treat. Among these cats, she apparently enjoyed renown. Around the corner, yet another one appeared to be guarding a local election sign planted in the lawn; he received the same treatment. Two blocks east, the woman ministered her affections to a fat black Persian. Having slipped behind an easement eucalyptus, I was close enough to hear her friendly lilt, but not close enough to hear what exactly she said.

I hadn’t been in this part of town in a while and didn’t know it well, and the farther from the beach the woman strolled, the tighter the plot of streets became. When she turned a corner, I lost her. Maybe she went inside. I’d decided that my random follow needed to be conducted without the benefit of technology, but ultimately I did take out my phone to pull up a map. I’d had no contact with the woman, and I was pretty sure I had eluded detection (and therefore not caused alarm), so for the greater part I’d obeyed my own rules.

This had been interesting. Here was a cat lady who had a routine, a neighborhood; she belonged somewhere, but I didn’t know anything else about her, like if she herself had cats. Maybe she couldn’t because she lived her life with someone allergic to them, so she distributed her affections elsewhere. Or maybe she did live with cats and had extra love and treats to spare. I had no sense of how she’d spend her afternoon. Would her evening be as solitary as mine? Like me, did she have too much time to think? I accepted I’d never know. The final rule I’d made for myself was in many ways the most important, which was that if I tried to follow the same person twice, I might be perceived of as a threat.

I wanted to be extra sure I went unseen, so the next day I started following strangers by car. Maybe it wasn’t true, but I thought I’d be less noticeable driving and able to get away faster if I was discovered. I drove over the hill into the valley, to a development of white stucco houses with red tile roofs. I coasted around awhile, not spotting anyone, and then I saw a woman loading three children into a minivan. Where were they going at eleven in the morning on a school day?

I stayed with the minivan on a six-lane boulevard, even though the driver didn’t believe in using her turn signal. I worked out a scenario: the kids attended a parochial school, and today was a religious holiday, but the woman wasn’t pious and she’d promised to take them out for lunch somewhere fun, a diner where the waiters all sang if it was your birthday, a bowling alley, something like that. I could see the kids in the back of the minivan were a wild bunch, bouncing up and down, jabbing each other. Or maybe what was actually going on was dark: she was one of those evil mothers whose tale was told too late; she’d snapped and was going to drive the minivan off a bridge and kill them all in one sudden swerve—weren’t they now headed toward a bridge that spanned the freeway? Should I call 911?

No need. Where they ended up about ten miles later was on another sun-flattened street not unlike the one they’d started out on. A man roughly the same age as the woman stepped out onto his stoop. I parked across the street and unrolled my window. I could hear lively pop music emanating from the man’s house. The man stayed put while the woman slid open the door to the minivan. The children poured out and shuffled toward the house. The man went inside with the kids, and then the woman was back in the minivan, pulling away.

No wonder the kids were anxious: they should have been in school but were forced instead to perform this custodial dance. Would the father get them to their soccer practices and guitar lessons? The woman, meanwhile, doubled back the way we’d come. She pulled into a strip mall. I waited a moment, then followed her into a crafts store. One wall was devoted to yarn, which was where the woman stood and ran her fingertips across soft skeins. She was getting ideas, she told the salesperson. Was she knitting a gift for someone? Probably, the woman said, she usually gave away what she made. She had family somewhere cold. At night, especially when her ex-husband had the kids, it helped to keep her hands busy.

The woman actually didn’t speak any of this—these were my thoughts—but I wanted to imagine her life. I wanted to lose myself in it. And was I correct about her? Did it matter? Something was breaking in me, and after I left the store and went a short ways, I had to pull over because I became too teary to drive. Did I feel sorry for the woman? Not exactly, but I recognized a pattern: I projected loneliness onto everyone whom I encountered. The stories I was concocting, they were in the end all about me, weren’t they? And I desperately needed to move beyond the perimeter of my own being.

I drove around some more with no clue where I was, and I followed other people: gardeners trimming coral trees, an old woman walking an old dachshund, three young guys tossing a basketball back and forth. I would follow one person or group for a while, then veer off and follow another: a carom follow.

Back home I took a warm shower. It must have been nine or ten at night, and I’d not eaten. I was so exhausted that I sat down in the stall with the water beating down on my shoulders. How was it possible I’d lost sight of what bound humans to one another? The same epic sorrows, the same epic joys. I had to wonder how alone I was in drifting so easily from such basic commune, and maybe this was more common than I realized. If nothing else at this point, I understood how terribly un-unique I was.

I couldn’t figure out where Craig was headed. He seemed at once to be making discoveries and to be riding a downward slope into deeper despondency. When he left his house in the mornings, he brought snack bars and sandwiches, a change of shirt, a sweater. He followed one person or group of people and then the next, and when he lost the light and wanted to head home, sometimes he had to drive an hour, an hour and a half through traffic from a neighboring county. He wanted to see how far he could push this, how far from home he was willing to go, how lost he was willing to get. This went on for a month, and then one morning he prepared for a longer road trip.

Since I wasn’t sure where I was heading, into what climate, I packed a bag with both cargo shorts and a cardigan. I drove across the river into the eastern part of the city and tracked a food truck. I caromed off into a park in pursuit of some of the food truck customers and watched them picnic. From the park, I picked up a pack of motorcyclists heading east, and this took me some distance into drier terrain.

The road threaded through mustard-colored towns, past silos, past windmills. I stopped at a diner somewhere and watched four women chat over lunch. I followed one of them to a storefront dance studio. There was a locksmith finishing up a task there—I followed him out on another a call. And so on. Trees disappeared, there was only rough scrub, then little of that.

In the desert, one hundred and fifty miles from home, I ran out of daylight and stopped at a motel. I fell asleep in my clothes. The next morning, I followed motel guests after they checked out, a man and a woman about my age. They were portly in the same way, both wearing jeans, cowboy shirts, boots, and I decided they were a couple who over time had grown to look alike the way couples do; it was also possible they were siblings.

I stayed with them on the highway and exited when they did an hour later, each new desert town more baked than the last. I worried they had noticed me, and I dropped back, letting their car push forward until it was no bigger than a hawk hugging the horizon.

Without warning the car pulled off the road, sending up a cloud of dust, and wound down a dirt drive toward a ranch house. They parked next to two pickups, one of them up on blocks. Tempted though I was, I couldn’t very well drive down the dirt road, too, and I couldn’t stay parked up on the street. I wanted to know what the couple/siblings were up to—there had been something notably joyless about them when they’d left the motel without banter, grim-faced, probably not on holiday—and to figure them out, I’d have to take my chances and come back later under the cover of night to see if they were still here.

I drove around. I noticed a sign for an inn a few miles east but napped instead in my car. It started to get dark. I went back to the ranch house. The couple’s car was where they’d left it. I continued a quarter mile on, parked on the shoulder, and walked back. There were lights on in the house. The property wasn’t fenced, but I made sure not to get too close. I wasn’t at all prepared for the desert wind, which numbed my ears. When it was truly night, I could see better into the house, and I crouched down there a long, long while, and this was what I observed:

Three people, the man and woman I’d followed (siblings after all, I decided), both moving about a kitchen, plus a white-haired man seated at the table, the man small in his chair. Their father, from the look of it. The woman was setting the table, and she tied a bib around her father’s neck. The son was at the stove, spooning the contents of various pots into serving bowls. Steam rose from a bowl of spaghetti. Then the siblings sat on either side of the older man, and they held hands in grace. I heard a crescendo of laughter, and the son served food to the father, the daughter promptly cutting it up. The father couldn’t feed himself; his children took turns spooning him dinner. He slumped a bit in his chair, but the siblings were merry anyway, putting on a show, telling stories.

That was it, that was all I saw, adult siblings being tender with their frail father. Where was their mother? Had she died some time ago or did she live (had she lived) another life elsewhere? The father stayed out here far from town, from other houses, so who tended to him when his adult children were not around? Was this visit routine or was it a special occasion? I waited for a birthday cake, but there was no cake, only alps of ice cream. What was the history of this family? Had there been a period of estrangement? Had a mother’s final illness yielded a rapprochement? Had the siblings moved out of the desert the moment they could, or was it the father who’d fled the city? Maybe it was the siblings themselves who had been at odds, but their father‘s failing health had necessitated them setting aside their differences...

My lower back ached from hovering in one place for too long; the wind left me with a ringing in my ears; my hands were shaking. I drove slowly, following the signs to the nearby inn, and before I stepped inside I noticed a flyer taped up to a utility pole, and on the flyer an image of a small dog with pointy tufted ears. Across the top of the page, someone had written Perro perdido.

When I stepped inside the inn, I was delirious with hunger and melancholy, and to the woman who set down her book to greet me, I asked, Are there generally a lot of lost dogs in this town?

The woman thought about it. Not particularly, she said. Now and then, I suppose.

Are they ever found, the dogs that do go missing?

The woman shrugged. Some, she said. That’s the hope.

That is the hope, I said.

When I asked if there was a room available, the woman of course wanted to know for how long, but I didn’t have an answer. Then for some reason she asked if I was looking for work, because she was only filling in and they needed a new night manager. Was I qualified?

I wrote this essay over a series of slow nights at the front desk. I have turned my sabbatical into an extended leave, and although I suspect one day I might return to my city life, I am in no hurry. I no longer follow strangers, but I do interact with new guests at the inn every day, and when someone wants to find the old turquoise mine or a desert trail head, even if it’s the morning and the end of my shift, I usher the guests where they want to go. Along the way, I try to find out as much about them as I can, what brought them here, what they are escaping and/or to what they eventually will return. Where they are headed next.

Once upon a time I was an avid traveler and left the country twice a year. I used to keep a checklist of places I needed to see, the monuments, the landscapes. Now I am less interested in places than people. I can’t get enough of people.

I very much doubt that most of you reading my account have or will become as closed off as I did, as cold at night, as folded inward, but for those of you who do worry that you, too, might slide into similar despair, I suggest you study the nearest stranger from a safe distance and watch him or her a long while.

Forget about yourself. Don’t make an approach. This is your only chance. Look. Keep looking.

How can you draw a line connecting you and this stranger? How can you make that line indelible?

THE FIRST QUESTIONS THE INVESTIGATING DETECTIVE ASKED ME about the last time I’d seen Ezra were the obvious ones: Had he appeared restless or preoccupied? Was he evasive about anything? Did he seem manic? Or hopeless?

“Did Mr. Voight say anything cryptic?” Detective Martinez asked.

Not that I could recall. The last time I’d been with him was on a Sunday. I was dropping off a cast-iron skillet—

“A skillet?” the detective asked. “Why a skillet?”

There was one in my kitchen that was especially good for searing. I was eating out or ordering in all the time, whereas Ezra had been on a cooking jag. When I showed up he was already making mushroom risotto. I was instructed to pour myself a glass of wine, have a seat, and keep him company while he stirred in wine and broth.

“He seemed settled,” the detective said. “In a good place.”

“I don’t know. Maybe that’s what I wanted to see,” I said.

The risotto was loamy and rich, and we shared a bottle of the same wine he’d cooked with. Ezra was excited about an art book he’d purchased. Even with his employee discount, he spent too much on books, but I didn’t say anything. It was a monograph of an artist we’d both long admired, plates of prints made over the years when this artist wasn’t producing the monumental sculpture she was better known for. In pencil, she would cover a page with notations, numbers, a schematic drawing that looked like a blueprint or a plan for an imaginary city, and then within the grids and boxes, across her notations, she would lay in geometric blocks in powdery pigment, one bold color per print, usually cadmium orange. She made the same kind of work again and again for years, and as we were sitting next to each other on Ezra’s couch, the book open on his lap, what he remarked on, what he found extraordinary, was the way an artist might latch on to an idiom early in a career, and his or her whole output for decades would become variations on an initial theme. But the work never got dull—the opposite. It only grew subtler, more sublime. There was the sculptor with his steel plates, the composer with his arpeggios, the author with her driving declarative refrains. How did they know at such an early age that they were on to something? Where did that self-confidence come from? It’s so alien to me and you, Ezra said.

“To me and you?” the detective asked. “I can understand him speaking for himself, but why did he include you?”

Detective Martinez had an uncanny way of not blinking until her question was answered. She had zeroed in on my discomfort right away.

“When Ezra and I were younger,” I told her, “he wanted to be a novelist, and I was going to be an artist. Off and on, he was still working on something, but I stopped painting after college—”

“You gave up on it.”

“I was never very good at it. I’d have a picture of something in my mind, but then anything I made fell far short of that image. But painting led me to art history, which led to architectural history, and when I imagined becoming an architect, I became so much happier.”

“But Ezra thought you’d left something behind,” Detective Martinez said. “Maybe he thought that you thought he should likewise give up his writing, too—”

“No. I always encouraged him.”

“Earn a real living—”

“You’re putting words in my mouth,” I said.

Ezra used to say that there were two kinds of people: those who looked completely different when they had wet hair, and those who looked exactly the same when their hair was wet or dry. For some reason he never explained, he didn’t trust the people whose hair looked the same wet or dry. The detective likely fell in that category.

“It’s my job to come up with a line and follow that line,” she said. “I don’t always get it right. Then I try to find a better line. It’s an imperfect method, I admit.”

I accepted her apology, if that was what it was, with a nod.

“So you stayed for dinner and were looking at this art book, and he suggested that you and he were alike in your inability to realize your dreams, even if that wasn’t an accurate representation of the situation for you.”

I could have pointed out that for every artist who found his voice early on, there was the genius who created great work later in life. Plus Ezra and I were not that old—maybe no longer young, but only forty. He had time. But I didn’t say these things that night.

“And that was that,” Detective Martinez said. “Nothing else happened?”

I didn’t answer.

“Ms. Crane?”

“We talked some more, but yes, that was that,” I said.

Detective Martinez was staring at me again without blinking. She knew I was lying. I glanced around her office, void of personal effects. No photos, no mementos.

“I keep thinking about a documentary we saw,” I said. “It was about a man who disappeared and was found a month later at a hospital not too far from home, but without any ID. He had amnesia. No one would ever figure out what triggered it. The only thing he had with him was a book with a phone number scribbled on the inside cover, which belonged to an ex-girlfriend. She was traveling and unreachable. When she finally came home, she was able to identify the man. The man had retained the ability to do physical things, like ride a bike or surf or make love—even speak French. But he remembered no people or places or experiences. The first time he saw snow after his amnesia, he was both awestruck like a child might be, and analytic like an adult, trying to figure out what it consisted of.”

“Amnesia is pretty rare.”

“Oh, I wasn’t suggesting—”

“Mr. Voight liked this film?”

“He saw it several times when it came out.”

The detective wrote this down, although I didn’t know how it would be useful. Then she set down her pen and laced her fingers.

She said, “Mr. Voight has been gone only one month, but—”

“Only one month?”

“But you need to consider the possibility that he doesn’t want to be found.”

“You’re saying you don’t think we’ll find him?” I asked.

“No,” she said. “I’m saying it’s possible he doesn’t want you to find him.”

This was a sharp arrow; it went in deep. I already knew that, yes. How could I not have thought about that? She didn’t need to say it aloud, not yet anyway.

“I’ll start in on the databases right away,” Detective Martinez said, softer. “Let’s see if we can learn anything.”

Protocols were followed: I provided photos, descriptions of physical attributes (including the location of the moles along Ezra’s chin that his scruff usually masked), and lists of friends and relatives (although like me, he wasn’t close to his family). I filled out an exhaustive questionnaire about what he might be wearing and carrying in the leather shoulder bag that we could say was missing, and per Detective Martinez’s request, I arranged to have his dental records sent over. I dropped off a pair of shoes, too. That part was disconcerting, walking into the precinct with my right index and middle fingers hooked into the heels of Ezra’s worn chukkas, like I was cleaning up after him and returning his things to our closet.

Meanwhile the detective was funneling information into the web of databases operated by various agencies and hospital systems—and morgues. I tried not to think about the morgues. I could access his bank account because he hadn’t changed his password since college, but I could see he wasn’t withdrawing cash. (I’d started paying his rent because I didn’t want to move his belongings to my house; that seemed to suggest he’d never be found or never come back.) According to the bookstore, he had cashed his last paycheck, so he had some money. (At the bookstore, they thought he’d quit without giving notice, which was out of character, but plausible.) We tracked his credit cards, but he wasn’t using them. He wasn’t using his cell phone either. He didn’t appear on any closed-circuit cameras in local shopping malls or major intersections. He’d never much tapped into social media. I was supposed to tell my friends and colleagues about what was going on to cast a wider net, and I did; they weren’t surprised Ezra would pull a stunt like this—a stunt, as if his disappearance were a performance. The detective wanted me to post flyers. Perro perdido, please wander home. I didn’t end up posting anything, and besides, the police had already canvassed nearby shop owners and neighbors about whether they’d seen him.

After a month (which meant Ezra had been missing for two), I showed up at the police station unannounced and demanded to see Detective Martinez. She met me at the front desk because she had someone in her office and guided me to a free bench.

“I haven’t heard anything from you in weeks,” I said.

“Rebecca—”

“You haven’t taken me seriously this whole time. You’ve implied more than once that there’s something peculiar about my history with Ezra.”

“I don’t think I ever said anything like that.”

“I don’t think you’ve been harnessing the full force of the department to find him.”

People waiting to be called to pay citations and report petty thefts all stared at me. For some reason, this was the moment I noticed that Detective Martinez’s earlobes were both multiply pierced, although she wore no jewelry.

She leaned toward me and whispered, “I think we both know you haven’t been completely straight with me.”

Now I was the one who didn’t blink.

“For whatever reason, you decided not to tell me what you found when you first went into Ezra’s apartment with the property manager,” she said.

I blinked.

“I’m guessing the property manager noticed me taking the printout,” I said.

“Look,” Detective Martinez said, “this stranger game is the bane of my existence. Do you know how many missing persons reports have been filed in the last year alone?”

“Stranger game?” I asked.

“The article. You read it?”

“Yes, but what about it?”

“The fad that came out of it,” Detective Martinez said. “You mean to say you don’t know about that?”

I shook my head no.

“That’s refreshing,” the detective said. “I wish more people didn’t know about it. But then why did you take the article with you?”

I’d sensed it was important. I wanted to know what Ezra was reading when he vanished. He’d always had a way of being deeply affected by whatever he encountered, be it a book, a song, a dog, a tree—he was both more available than I was to be influenced and more readily buffeted.

“It’s been passed around five million times, ten million times,” the detective said. “I don’t think we really know how many times.”

She described the craze the essay had launched, and I was confused.

“But the article is about overcoming your alienation,” I said.

“I think most people only read about the other people playing the game, not the original article itself.”

“It’s a terrible misinterpretation then. There is no mention of any kind of game.”

“The writer talks about empathy, but the game isn’t about that at all. It’s about seeing how long you can follow a stranger without getting caught. There are the three rules because it wouldn’t be a game without rules. But it’s not a game at all. From where I sit, it’s called stalking.”

Some gossip I’d heard about a friend of a friend now made sense. This person was an ambitious associate at a big law firm, the consummate networker, and meanwhile always planning weekend getaways with her fiancé. But some months ago, she had become deeply engaged in an activity that my friend labeled addictive. I assumed it was drugs. Then my friend’s friend started showing up late to meetings and went missing for hours, and apparently she lied to her fiancé about her whereabouts—the fiancé assumed she was hiding an affair. It didn’t let up. Eventually the fiancé left her and the woman was asked to take a leave from her law firm to sort things out; she’d moved in with her mother, but by all accounts, she still went missing for days at a time. When I asked my friend what kind of drugs her friend had gotten into, or if it was alcohol, my friend made it clear there weren’t substances involved; her friend had been playing the game, and I assumed game was code for gambling or sex.

“So people lose themselves in this,” I said. “But do they usually disappear?”

“Eventually they come home, they turn up,” Detective Martinez said. “It’s a waste of our resources chasing grown adults who run off one day because they feel like it, but we don’t choose who we look for and who we don’t. We look for everybody.”

I very much could see the appeal to Ezra. He craved the open road, and he took so much pleasure in meeting strangers. He quizzed taxi drivers and airplane row mates and buskers in the park for their life stories.

“I separated from my husband last year after twenty years,” Detective Martinez said. “We met on the force. I still work with him. We get along fine, all things considered. We have joint custody of the dogs. So I understand how things might be between you and Ezra. The concern, the care—it doesn’t simply stop. You could’ve told me about finding the article.”

I was still very much in love with Ezra, and the detective was probably still very much in love with her soon-to-be ex-husband, and the whole world was full of people very much in love with lost lovers. We sat there a moment longer before the detective stood up to return to whomever was in her office, and I pulled her arm so she sat back down.

I wanted to ask: Have you ever watched someone close to you slip away? You see it happening, but there’s nothing you can do about it—has that happened to you?

Instead I said, “He was always a little adrift. It was charming for a while, and then it was exhausting.” I said, “I didn’t take care of him.”

I started sobbing in my hands, and the detective’s whole posture changed. She slumped back in the bench a bit. When I looked up, I noticed everyone in the room doing his or her best to look away.

“I live around the corner from here. I made chicken soup last night. Come home with me now, I’ll give you some homemade soup, you’ll feel better. Let me get rid of the people in my office, then we’ll get you some soup.”

“This sounds unorthodox,” I said.

“Nobody follows the rules all the time,” the detective said.

Her house was a clapboard cottage painted mint green, the trim also green but darker. Green was clearly Detective Martinez’s favorite color because her sunlit cozy kitchen with its shelves of cookbooks and pots hanging over the range was yet another soft green. I did feel calmer sipping warm soup on a warm day. There was a collection of frogs on a windowsill, some crystal, some plastic. Two large dogs were lolling in the sun in the backyard. I knew that Detective Martinez didn’t want to tell me that after two months she was pretty sure Ezra wouldn’t turn up. She wasn’t exactly my new friend, but she knew I needed a new friend.

“Can I ask you something?” Detective Martinez said. “And I ask this because I’m trying to help. You admitted to finding the article, great. Is there anything else maybe that you haven’t told me?”

“Nothing,” I said a little too quickly.

The detective didn’t blink.

“Now you know everything,” I said.

“Okay. Right.”

“No, honestly, you do.”

“All right then, I’ll believe you. Let me put it this way. Rebecca, let’s say hypothetically that Ezra has moved on—”

“I haven’t been to the studio today,” I said. “I really should go.”

“Let’s just say he’s moved on. You two haven’t been together awhile now. Let’s just say he disappeared because he wanted a new life, and this was the only way he knew how to find it. So. What about you? What are you going to do now for yourself?”

I wasn’t going to give the detective what she wanted. I thanked her for her soup and sympathy, told her to let me know if she learned anything new, and I left.

A MEMORY NOW, A WINTER NIGHT—EZRA AND I TUCKED INTO opposite corners of the couch. I might have been half reading a novel, half staring out at the city, considering getting into bed, but Ezra would be up another hour or longer; he was wide-awake, elsewhere, studying the maps of a country thousands of miles away. He’d brought home a travel guide from the bookstore, one from the series he liked that came packed with extra history and excerpts by literary heroes juxtaposed with the usual photos of spires and spice markets. We hadn’t necessarily agreed this was where we’d go the following summer, but in his mind we were on our way, and the planning fell to him. Ezra took such pleasure in constructing the perfect day. We’d follow the path he’d mark out for us, from the chapel with restored frescoes to the house where a poet wrote his odes and died young, across stone bridges, through a cluttered cemetery, coiling up narrow streets until we reached the ledge of a park overlooking the jeweled city, the city a puzzle we’d solved together. Then Ezra would withdraw a bottle of wine from his backpack, a wedge of cheese, bread, fruit—a sleight of hand because I never noticed him packing a picnic (or I chose not to keep track of what he was doing because I wanted to be surprised). These were days of lidless pleasure. My only dread would be the return flight, the arrival home, Ezra’s lassitude when we had to fall back into our regular routines. In later years when he seemed down to me, I’d ask him where we were going next to cheer him up, and this worked for a time—he’d come home with a new travel guide, he’d unfold new maps. It worked, and then it didn’t work so much; nothing did.

Another memory, even earlier, from around the time Ezra moved out west to be with me. On Sunday afternoons, postnap, predinner, he would announce we were going on a drive. A drive where? I’d ask. Oh, nowhere in particular, he’d say. The idea was we’d venture out, allow ourselves to get lost, then figure out how to get back without consulting a map. I myself didn’t know the neighborhoods well because I’d been working long hours and hadn’t had time to explore. Let’s see what we can discover, Ezra said, and usually he would steer us up into the foothills, and we’d follow the haunches and hollows of that terrain until we wound down to the beach. Sometimes we got out and walked on the windy bluff at dusk. Sometimes we sat in the car parked on the side of the coast road and made out like teenagers. Dusk was Ezra’s favorite time of day, and mine, too; it was impossible not to believe in your eventual prosperity when the sun melted into the pacific distance and the night was still unwritten.

Eventually there were more and more Sundays when I needed to catch up on work and begged out of the drive, and Ezra didn’t pout about it; he went alone. When he came home, however, he would pull me from my desk to the couch to cuddle with him. Be with me now, he’d say, and he was cute about it, and of course I gave in. I should have gone on the drives though. Even then I could see this, and I don’t know why I didn’t.

I thought the stranger game might be akin to getting lost in a landscape you didn’t know and then finding your way back from its littoral edge, that this was the appeal to Ezra, except he hadn’t come back from this drive, had he? Be with me now. I wanted to understand what he was experiencing. I was convinced he’d become a player, and I admit it made no sense, but I thought the only way to find him was to figure out where the game might lead.

Days after following the two men at the museum, I was looking for new clothes to wear for client presentations, and I ended up randomly tracking a woman my age into the men’s section of a department store. She was checking out sweaters—for whom? A friend, a boyfriend, her husband? Her ex-husband? I watched her set aside several sweaters, all of them gray. Then she stood in front of a full-length mirror and tried on each one. Were they for her? Or was it indeed a holiday gift, but a major consideration was how it would fit her when she borrowed it on cool mornings after she’d spent the night? She’d look ridiculous apparently: she put on a cardigan that looked more like a robe on her. The charcoal turtleneck she ended up purchasing became a minidress, but she didn’t care. She’d be closer to him when she wore it.

Early the following morning instead of driving to the gym, I followed a guy delivering newspapers. He had terrible aim. He slung half the papers at garage doors and light posts and had to hop out of his car to redirect the papers to stoops and gates. This was his third job, he was trying to pick up extra cash to support the little girl in the back seat, belted in next to the steep pile of newsprint. He wanted her to be able to take piano lessons. The more papers he delivered, the lower the pile next to his daughter, and the better her view of a neighborhood miles away from the one where they lived.

Later that afternoon, I followed another father into a diner, a father and his son; the kid wore glasses too big for his face and read a paperback while walking. He attacked a shared sundae with less zeal than his father; he wanted to be reading, he wanted to be in his bedroom with the door shut. The longer I watched them from across the diner, the more vivid everything became: the red of the booth glowed in a ruby wash; the boy’s lenses were as clear as new window glass; in the man’s face, the first striations of age appeared right as I stared at him, like cracks emerging in burning firewood. Every edge became sharper, and maybe it was the time of year, the earlier sunsets, the angled light. Or I was in the habit of observing others with greater care. I’m trying to define a state of hyperalertness. It was a tonic. I wanted to prolong it.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/peter-gadol/the-stranger-game/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Peter Gadol

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв