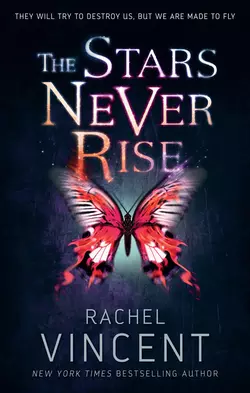

The Stars Never Rise

Rachel Vincent

There’s no turning back…In the town of New Temperance, souls are in short supply and Nina should be worrying about protecting hers. Yet she’s too busy trying to keep her sister Mellie safe.When Nina discovers that Mellie is keeping a secret that threatens their existence, she’ll do anything to protect her. Because in New Temperance, sins are prosecuted as crimes by the brutal church.To keep them both alive, Nina will need to trust Finn, a mysterious fugitive who has already saved her life once. Wanted by the church and hunted by dark forces, Nina knows she needs Finn and his group of rogue friends.But what do they need from her in return?‘Haunting, unsettling and eerily beautiful’ – Rachel Caine

Praise for the novels of New York Times bestselling author (#u5bc4caf5-9a93-5657-986c-d7475adf932a)

RACHEL

VINCENT

‘I liked the character and loved the action. I look

forward to reading the next book in the series.’

Charlaine Harris

‘Vincent is a welcome addition to the genre!’

Kelley Armstrong

‘Compelling and edgy, dark and evocative, Stray is a must read! I loved it from beginning to end.’ Gena Showalter

‘I had trouble putting this book down. Every time

I said I was going to read just one more chapter,

I’d find myself three chapters later.’

Bitten by Books on Stray

‘Vincent continues to impress with the freshness of her

approach and voice. Action and intrigue abound.’

RT Book Reviews

RACHEL VINCENT is the New York Times bestselling author of many books for adults and for teens, including the Shifters, Unbound, and Soul Screamer series. A resident of Oklahoma, she has two teenagers, two cats and a BA in English, each of which contributes in some way to every book she writes. When she’s not working, Rachel can be found curled up with a book or watching movies and playing video games with her husband.

Visit Rachel online at

rachelvincent.com (http://www.rachelvincent.com)

Follow Rachel Vincent on

www.miraink.co.uk (http://www.miraink.co.uk)

To my husband, who helped me brainstorm this project in various versions for two full years before I even told my agent about it. Thanks for all the plotting sessions, for the sketches you drew of my concepts and for your endless patience. You’re the best. No, really.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#u5bc4caf5-9a93-5657-986c-d7475adf932a)

Thanks to my amazing agent, Merrilee Heifetz, who makes things happen.

Thanks to my new editor, Wendy Loggia at Delacorte Press, who championed this book all the way into print.

Thanks, as always, to my critique partner, Rinda Elliott, who saw several versions of the beginning of this book, only a few passages of which made it into the final text. Your input is invaluable.

Many thanks to the awesome Rachel Clarke for a critical early read.

A big thank-you to Jennifer Lynn Barnes, for Panera writing days, company and advice. There is no scene that cannot be conquered with a little caffeine and a bowl of soup.

And finally, thanks to everyone at Random House who has worked on The Stars Never Rise. Your dedication and experience are greatly appreciated.

And finally, thanks to everyone who has worked on The Stars Never Rise. Your dedication and experience are greatly appreciated. Thanks so much to Angharad Kowal, my UK agent, and to Anna Baggaley and Mira Ink, for making The Stars Never Rise available in the UK.

Table of Contents

Cover (#u34d27926-1c83-5232-b873-d3348aec91d5)

Praise

About the Author (#uf1fe08ce-b722-5dcb-9402-6d322468a3bf)

Title Page (#ue88375f5-7f41-55e4-a3c0-7829c65579d5)

Dedication (#ue54e2fd4-dc4a-5098-90cc-bfe227d4631c)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

Endpage (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

ONE (#u5bc4caf5-9a93-5657-986c-d7475adf932a)

There’s never a good time of day to cross town with a bag full of stolen goods, but of all the possibilities, five a.m. was the hour best suited to that particular sin.

Five a.m. and I were well acquainted.

“Nina, hurry!” Marta whispered, glancing over my shoulder at the cold, dark backyard, but she probably couldn’t see much of the neat lawn beyond the rectangle of light shining through the open screen door. “Mrs. Turner’s already up.” She wiped flour from one hand with a rag, then flipped the lock and pushed the door open slowly so it wouldn’t squeal and give us away.

“Sorry. Mr. Howard locked his back gate, so I had to go the long way.” My teeth still chattering, I stepped into the Turners’ warm kitchen and handed Marta the garment bag I’d carried folded over my right arm. The plastic was freezing from my predawn trek. Marta would have to hang the uniforms near a heater vent, or Sarah Turner would figure out that her school clothes hadn’t spent the night in her warm house, and I’d be out of a job. Again.

I couldn’t afford to lose this one.

Marta set her rag on the butcher-block kitchen island, where she’d been cutting out homemade biscuits, then hooked the hangers—I’d bundled them just like the dry cleaner would have—over the door to a formal dining room half the size of my house. I’d been in there once. The Turners’ cloth napkins probably cost more than my whole wardrobe.

Mr. Turner owned the factory that made the Church cassocks—official robes—for most of the region. I found that ironic, considering the illicit work I was doing on his daughter’s clothes, but I refused to feel guilty. The Turners’ monthly tithe would feed my whole family for a year.

“They’re all here?” Marta unzipped the garment bag to inspect my work.

“Same as always. Five blouses, five pairs of slacks, all starched and pressed. That raspberry stain came out too.” I picked up the sleeve of the first blouse to show her the bright white cuff, and when she bent to study the material, I took a can of beef stew from the shelf at my back and slid it into the pocket of my oversized jacket.

“Good. Here’s next week’s batch.” Marta straightened and gestured to a bulging brown paper bag sitting on the tile countertop. “Sarah cut herself and bled on one of them….” She opened the bag and lifted the stained tail of a blouse at the top of the pile. “I told her blood won’t come out of white cotton, so she’s already replaced it, which means you’re welcome to keep this one. The stain’ll never show with it tucked in.”

“Thanks.” I mentally added the secondhand blouse to the small collection of school uniforms my sister and I actually owned.

Marta rolled down the top of the bag and shoved it at me, and when she turned to open a drawer beneath the counter, I slid another can of stew into my other pocket. My coat hung evenly now, and the weight of real food was reassuring.

“And here’s your cash.” She pressed a five and a ten from the drawer into my hand, then ushered me out the back door.

I grinned in spite of the cold as I jogged down the steps, then onto the Turners’ manicured back lawn, running my thumb over the sacred flames printed in the center of the worn, faded bills. That fifteen dollars put me within ten of paying this month’s electric bill, which wasn’t due for another week and might actually be paid on time, thanks to my arrangement with Marta.

Every week, Mrs. Turner gave her housekeeper twenty dollars to have Sarah’s school uniforms cleaned and pressed. Every Monday, Marta kept five of those dollars for herself and gave the rest to me, along with that week’s dirty clothes. Sarah had two full sets of school clothes. As long as she got five clean uniforms every Monday morning, Marta didn’t care what my sister and I did with them until then. So we laundered them on Monday afternoon, wore them throughout the week to supplement our own hand-me-down, piecemeal collection of school clothes, then laundered them again over the weekend in time to deliver them fresh and clean on Monday morning.

Marta got a little pocket money. Sarah got clean uniforms. My sister and I got cash we desperately needed, as well as the use of clothes nice enough to keep the sisters from investigating our home life.

So what if deception was a sin? You can’t get convicted if you don’t get caught.

Shivering again, I crept around square hedges, careful not to step on the layer of white rocks in the empty flower bed, then into the yard next door. The Turners’ house was only three-quarters of a mile from mine, but at 5:50 in the morning, with the temperature near freezing, that felt like the longest three-quarters of a mile in the world. Especially considering that from Sarah’s backyard, closer to the center of town, the town wall wasn’t even visible.

From my backyard, that hulking, razor-wire-topped steel wall was the primary landmark.

I cut through several backyards and a small alley on the way home, and to avoid Mr. Howard’s locked gate, I had to detour onto Third Street, where most of the store windows were still dark, the parking lots empty. The exception was the Grab-n-Go, which stayed open twenty-four hours a day. As I skirted the brightly lit parking lot and gas pumps, I glanced through the glass wall of the store at the huge wall-mounted television dutifully broadcasting the news, as required by the Church during all business hours. In the interest of public awareness, of course.

Willful ignorance was a sin.

The Grab-n-Go was playing the national news feed. The only other choice was the local news, which repeated on a much shorter, more annoying loop. Still, I kind of felt sorry for the night clerk, sentenced to listen to the same headlines repeated hour after hour, with few customers to break the monotony.

I couldn’t actually hear the newscaster, in her purple Church cassock with the broad, gold-embroidered cuffs, but I could tell what she was saying because in the absence of actual breaking news, newscasters all said the same things. Tithes are up. Reports of demonic possession are at an all-time low. Our citizens are safe inside their steel cages—I mean, walls. The battle still rages overseas and degenerates still roam the badlands, but the Church is vigilant, both at home and abroad, for your safety.

It had been more than a century since the Unified Church and its army of exorcists wiped the bulk of the great demon horde from the face of the earth—the face of America, anyway—yet the headlines never changed.

I stuck to the shadows, walking along the windowless side of the convenience store. Old posters tacked to the brick wall read “Put your talents to work for your country—consider serving the Church!” and “Report suspicions of possession—the Church needs your eyes and ears!” and “Tithe generously! Every dime makes a difference!”

That last one was especially funny. As if tithing were optional. My mom owed several thousand in overdue tithes, from back when she was still working, and if the Church came looking for it, we were screwed.

Behind the store, I rolled the top of the bag tighter to protect the clothes inside, then tossed my bundle over the six-foot chain-link fence stretched across the width of the alley, shielding the Grab-n-Go’s industrial trash bin from casual dumping by the adjoining neighborhood. My neighborhood.

The bag landed with the crunch of gravel and the crinkle of thick paper. I had the toe of one sneaker wedged into the chain-link, my fingers already curled around cold metal, when I heard a rustle from the deep shadows at the other end of the alley. I froze, listening. Something scraped concrete in the darkness.

I let go of the fence and took a step back, my heart thudding in my ears.

Dog. But it’d have to be a big one.

Bum. But there weren’t many of those anymore—the Church had been taking them off the street and conscripting them into service for more than a decade.

Psycho. There were still plenty of those, and my mom seemed to know them all. But not-quite six in the morning was early, even for most psychos.

Something shuffled closer on the other side of the fence, and I saw movement in the shadows. My fists clenched and unclenched. My pulse whooshed in my ears, and I regretted throwing Sarah’s clothes over the fence. I regretted not taking the even longer way home, through the park. I regretted having a mother who couldn’t shake off chemical oblivion in order to feed and clothe her children.

The thing shuffled forward again, and two pinpoints of light appeared in the darkness, bright and steady. Then they disappeared. Then reappeared.

Something was blinking. Watching me.

Shit! I glanced at the paper bag through the fence, clearly visible in the moonlight, just feet from deep shadows cast by the building. Deep shadows hiding … a dog.

It’s just a dog…. It had to be. People’s eyes don’t shine in the dark.

You know whose eyes do shine in the dark, Nina? Degenerates’.

My pulse spiked. There hadn’t been a confirmed possession in New Temperance in years, and the last time a degenerate made it over the town wall, I was in the first grade.

It’s a dog.

No stray dog was going to scare me away from a bag of uniforms that cost more than I could make in six months of washing and pressing them. That wouldn’t just be the end of my work for the Turners, it would be the end of Marta’s work for the Turners and the beginning of my conviction for the sin of stealing. Or falsehood. Or whatever they decided to call borrowing and laundering someone else’s clothes under false pretenses.

I stepped up to the chain-link, mentally berating myself for being such a coward. I was halfway up the fence when the shuffling started again, an uneven gait, as if the dog—or the shiny-eyed psycho?—was injured and dragging one foot. I could hear it breathing now, a rasping, whistling sound, not unlike my own ragged intake of air. I was breathing too fast.

My hands clenched the fence, and metal dug into my fingers. I froze, caught between fear and determination. Injured dogs don’t approach strangers unless they’re sick or hungry. It couldn’t get through the fence. But I needed those clothes!

One more shuffle-scrape on concrete and a shape appeared out of the shadows. My throat closed around a cry of terror.

Part human, part monster, the creature squatted, a tangle of knees and elbows, stringy muscles shifting beneath grayish skin. The limbs were too long and too thin, the angles too sharp. The eyes were too small, but they shone with colorless light that seemed to see deep inside me, as if it were looking for something I wasn’t even sure I had.

Degenerate.

It wasn’t possible. I’d seen them on the news, but never in person. Never this close. Never in New Temperance …

It was bald, with cheekbones so sharp they should have sliced through skin, and ears pointy on both the tops and the lobes. And—most disturbing of all—it was female. Sagging, grayish breasts swung beneath torn scraps of cloth that were once a dress. Or maybe a bathrobe.

The monster roared, and its mouth opened too wide, its jaws unhinging with a gristly pop I could hardly hear over the horrific screech that made my ears ring and my eyes swim in tears. It watched me, and I stared back, frozen in terror.

Run!

No, don’t run. Back away slowly…. Maybe degenerates were like dogs, and if I ran, it would chase me.

I pulled my right shoe from the fence and slowly, carefully lowered myself, without looking away from the monster. It shuffled closer in its eerily agile squat, and I fumbled for a blind foothold in the metal as I sucked in air and spat it out too quickly to really be considered breathing.

The degenerate was six feet from the fence when I reached the ground and began slowly backing away, the uniforms forgotten. My hands were open, my legs bent, ready to run.

The monster squatted lower, impossibly low, and tensed all over, watching me like a cat about to pounce. Then it sprang at me in one powerful, evil-frog leap.

I screamed and backpedaled. The monster crashed into the chain-link fence. The metal clanked and shook, but held. The demon crashed to the ground, her nose smashed and bleeding, yet she still eyed me with hunger like I’d never seen before. She was up in an instant, pacing on her side of the fence on filthy hands and feet, her knees sticking up at odd angles. She stared through the metal diamonds at me with bright, colorless eyes, and I backed up until I hit the trash bin.

A low, rattling keening began deep in her throat when I started edging around the large bin, my palms flat against the cold, flaking metal at my back. The degenerate blinked at me, then glanced at the top of the fence in a bizarre, jerky movement. I realized what she intended an instant before she squatted, then leapt straight into the air.

Metal squealed when her knobby fingers caught in the top of the chain-link and her bare, filthy toes scrambled for purchase lower on the fence. For a moment, she balanced there like a monstrous cat on a wall.

My heart racing, I backed away quickly, afraid to let her out of my sight. She leapt again. I heard a visceral snap when she landed on the concrete just yards from me, her deformed right foot bent at a horrible angle. She lurched for me, in spite of the broken bone, and I screeched, scrambling backward.

The demon lunged again, clawlike fingers grasping at my sleeve. I kicked her hand away, but she was there again, and again I retreated until I hit the trash bin and realized I’d gotten turned around in the dark, and in my own fear. I was trapped between the demon and the fence.

She lurched forward and grabbed my ankle. The earth slipped out from under me, and my head cracked against the industrial bin. My ears rang with the clang of metal, and I hit the ground hard enough to bruise my tailbone. My head swam. Fear burned like fire in my veins.

The degenerate loomed over me in her creepy half crouch, rank breath rolling over my face as she leaned closer, her mouth open, gaping, ready for a bite.

“Over here!” someone shouted, and the degenerate twisted toward the fence, snarling, drool dripping from her rotting teeth and down her chin. Over her bony shoulder, I saw a shadowy form beyond the chain-link. A boy—or a man?—in dark clothes, his pale face half hidden by a hood.

She snarled at him again, one clawed hand still tight around my ankle, and I saw my chance. I kicked her in the chest with my free foot, and she fell backward, claws shredding the hem of my jeans.

“You don’t want her. Come get me!” Metal clinked and rattled, and I realized the boy was climbing the fence. And he was fast.

I crawled away, trying to get to my feet, but she grabbed my ankle and gave it a brutal tug. I fell flat on my stomach, then rolled over as she pulled and I kicked. My foot slammed into her belly, and her shoulder, and her neck, but she kept pulling until she was all I could see and hear and smell.

Concrete scraped my bare back when my coat and shirt rode up beneath me. I threw my hands up and my palms slammed into the degenerate’s collarbones. I pushed, holding her off me with terror-fueled strength. The chain-link fence rattled and squealed on my right. The beast snarled over me, deformed jaws snapping inches from my nose as my arms began to give, my elbows bending beneath the strain of her inhuman strength.

“Hey!” the boy shouted, and a thud told me he’d landed on my side of the fence, just feet away. His arm blurred through the shadows, and the degenerate snarled as it was hauled off me.

I scrambled backward, and the seat of my jeans dragged on the ground until my spine hit the trash bin again. My hands shook. My back burned, the flesh scraped raw by the concrete.

A bright flash of light half blinded me, and when my vision returned a second later, I could see only shadows in dark relief against the even darker alley. One of those shadows stood over the other, malformed shape, his hand against her bony sternum, both glowing with the last of that strange light.

What the hell …?

An exorcist.

An exorcist in a hoodie. Where were his long black cassock, his cross, and his holy water? Where were his formal silence and grave demeanor?

As I watched, stunned, that light faded, and slowly, slowly, the rest of the alley came into focus.

The boy stood and wiped his hands on his pants, his hood still hiding half his face. The degenerate lay unmoving on the ground, no less gruesome in death than she’d been in life, and now that the violent flash had receded from my vision, I realized the alley was growing lighter. The sun was rising.

I pushed myself to my feet while the boy watched me with eyes I couldn’t see in the shadow of his hood. “I … I …,” I stammered, but nothing intelligent followed.

“Holy hellfire!”

We turned to see the Grab-n-Go night clerk standing at the end of the alley, backlit by the parking lot lights, staring at us both. In the distance, a siren wailed, and I realized three things at once.

One: The clerk had reported the disturbance, and the Church was on its way.

Two: He hadn’t realized this was more than a scuffle in an alley until he saw the dead degenerate.

Three: I was still in possession of borrowed/stolen clothes, and since I was the victim of the first degenerate attack in New Temperance in the last decade, the Church would want to talk to my mom.

I couldn’t let that happen.

“Is that …?” the night clerk stared at the degenerate, taking in her elongated limbs and deformed jaw. His gaze rose to my face and he squinted into the shadows. He couldn’t see me clearly but was obviously too scared to come any closer. His focus shifted to the boy standing over the degenerate, and his eyes narrowed even more. “Are you …?”

“Run.” The boy didn’t shout. He didn’t make any threatening gestures. He just gave an order in a firm voice lent authority by the fact that he was standing over the corpse of a degenerate.

The clerk blinked. Then he turned and fled.

“You okay?” The boy shoved his hands into the pockets of his black hoodie. And he was a boy. My age. Maybe a little older. I still couldn’t see his eyes, but I could see his cheek. It was smooth and unscarred. No Church brand. No sacred flames.

What kind of exorcist has smooth cheeks and wears a hoodie?

“That’s a degenerate,” I said, and it only vaguely occurred to me that I was stating the obvious. I was just attacked by a demon. I couldn’t quite wrap my head around it. How had it gotten into town?

“Yeah. Is there any way I can convince you to maybe … not tell anyone what I did?”

I frowned. Why wouldn’t he want credit for killing a degenerate? How could he be an exorcist—obviously trained by the Church—yet bear no brand and wear no cassock?

“Please. Just … don’t mention me in your statement, okay?” He glanced to the east, and shadows receded from his jaw, which was square and kind of stubbly. The sirens were getting louder. I could see the flash of their lights in the distance, and the sky seemed to get lighter with every second.

I had to go.

“Not a problem.” I grabbed the chain-link and started hauling myself up the fence. I could not afford a home visit from the Church. Fortunately, the night clerk—Billy, the manager’s nephew—hadn’t recognized me. “I’m not making a statement.”

“You’re not?”

I could hear the question in his voice, but I couldn’t see his face because I was already halfway up the fence. “Thanks for that.” I let go of the chain-link with one hand to gesture at the degenerate below. Then I climbed faster and threw one leg over the top.

“Wait!” he said as I lowered myself from link to link on the other side of the fence. “Who are you?”

“Who am I?” The rogue teenage exorcist wanted to know who I was? “Who are you?”

“I’m … just trying to help. Why was it following you?”

Following me? The goose bumps on my arms had nothing to do with the predawn cold.

“I guess my soul smelled yummy.” Or, more likely, I would have been a meal of convenience—few people were out and about so early in the morning.

Two feet from the ground, I let go of the fence and dropped onto the concrete. When I stood, I found him watching me, both hands curled around the chain-link between us.

The sirens were wailing now, and the sun was almost up. I needed to go. But first, I had to see …

I stuck my hand through the fence—it barely fit—and reached for his hood. He let go of the chain-link and stepped back, startled. Then he came closer again. I pushed the hood off his head, and my gaze caught on thick brown waves as my fingers brushed them.

Then I saw his eyes. Deep green, with a dark ring around the outside and paler flecks throughout. For just a second, I stared at them. I’d never seen eyes like that. They were beautiful.

Then the wail of the siren sliced through my thoughts with a new and intrusive volume as the wall of the alley was painted with strobes of red and blue. The Church had arrived.

“Gotta go.” I pulled my arm through the fence too fast, and metal scraped the length of my thumb.

“Wait! We need to talk.”

“Sorry. No time. Thanks again for … you know. The demon slaying.” I bent to grab the bag of clothes. Then I ran.

At the mouth of the alley, I looked back, but the boy was gone.

The Grab-n-Go parking lot was alive with flashing lights and crawling with cops in ankle-length navy Church cassocks and stiff-brimmed hats. Billy, the night clerk, stood in the middle of the chaos, gesturing emphatically toward the alley while three different officers tried to take his statement. A second later, two of the three pocketed their notebooks and headed into the alley, slicing through the last of the predawn shadows with bright beams from their flashlights.

One squatted next to the dead degenerate while the other aimed his flashlight down the alley. I ducked around the corner in time to avoid the beam, and for a moment I just stood there, clutching the paper bag to my chest, trying to wrap my mind around everything that had just happened.

A degenerate in New Temperance.

A rogue exorcist with beautiful green eyes.

A parking lot full of cops.

And they were all looking for me.

TWO (#u5bc4caf5-9a93-5657-986c-d7475adf932a)

Dawn had officially arrived by the time I crossed my crcked patio and stepped into the kitchen, though the sun had yet to rise over the east side of the town wall. My heart was still pounding. A siren wailed from several blocks away. When I closed my eyes, I saw the monster looming over me, snapping inhuman jaws inches from my nose. I shut the back door softly, then dropped the bulging paper bag next to a duffel full of our own dirty laundry.

The clerk couldn’t identify me. The rogue exorcist didn’t know my name. The Church would not come knocking.

I repeated it silently but still had trouble believing it.

The clock over the stove read 6:14. School started in an hour and a quarter.

On my way through the kitchen, I noticed my mom’s purse on the table. I wasn’t sure whether to be relieved or pissed off that she’d returned home while I was fighting a degenerate in the alley behind the Grab-n-Go. I glanced into the living room, empty except for the scarred coffee table, worn sofa, and two mismatched armchairs. For the first time in weeks, she hadn’t passed out on the couch.

In the short, narrow hallway, I pushed her door open slowly to keep it from creaking, then sighed with relief. She’d made it to the bed this time. Mostly. Her arm and her bare right leg hung off the mattress. Her left leg was bare too, of course, but somehow she’d gotten her pants off without removing that one shoe.

Her legs were getting thinner—too thin—and so was her hair. Her kneecaps stood out like bony mesas growing beneath her skin, and her eyebrows were practically nonexistent. She’d been drawing them on for most of the past year, until she’d given up makeup entirely a few weeks ago. She didn’t go out during the day, anyway; she “worked” all night now, then stumbled home at dawn.

There was a spot of blood on her pillow, and more of it crusted on her upper lip. Another nosebleed. She was killing herself. Slowly. Painfully, from the looks of it.

“One more year, Mom,” I whispered as I pulled her door shut softly. “I just need one more year from you.”

In the room I shared with Melanie, our radio alarm had already gone off, and as usual, my little sister hadn’t noticed. I swear, a demon horde could march right through our house and she’d sleep through the whole thing.

“… and I, for one, am looking forward to a little sun!” the DJ said as I dropped my oversized coat on the floor. It thumped against the carpet, which is when I remembered the pilfered cans of stew I’d meant to leave in the kitchen. “In other news, Church officials in New Temperance are expected to announce their choice for headmaster of the New Temperance Day School today, a job vacated just last month when Brother Phillip Reynolds accepted a position in Solace….”

I listened for a couple of minutes, waiting to see if they’d announce a degenerate attack in New Temperance and the mysterious boy and girl spotted in the alley. When that didn’t happen, I poked the alarm button, relieved that I hadn’t yet made the news, and the DJ’s voice faded into blessed silence.

That alarm radio was the only thing on my scratched, scuffed nightstand. It was the last thing I saw before I fell asleep and the first thing I saw every morning. The clock divided my days into strict segments devoted to sleep, school, homework, housework, and real work. I had little time for anything else.

My sister’s nightstand was covered in books. Not textbooks or the Church-approved histories and biographies available in the school library. Mellie had old, thick hardcover volumes, some with nothing but black-and-white print stories, others with brightly colored strip illustrations of people with ridiculous powers, speaking in dialogue bubbles over the characters’ heads. She borrowed them from Adam Yung’s dad, who had a secret collection of prewar stuff in his basement.

The Church hadn’t officially outlawed secular fiction, but they had a way of making things like that unavailable to the general public. Right after the war against the Unclean, they’d recycled entire public library collections to reuse the materials. And after they’d brought down all cellular transmission towers—to keep demons from communicating with one another en masse—people had no use for their portable phones and communication devices, so there were recycling drives for those too.

Collections like Mr. Yung’s were rare. When we were kids, I’d read his stories with Melanie, curled up in our bed, dreaming of eras and technologies that were long past by the time we were born.

Then I grew up and realized that was all those stories ever were. Dreams. I lived in the real world, where Mellie was only a part-time citizen.

“Time to get up, Mel.” Standing, I gave my sister’s shoulder a shove. She groaned, and I grabbed the towel hanging over the footboard of the bed, then trudged into the hall.

My shower was cold—the pilot light on the hot water heater had gone out again—and we were out of soap, so I had to use shampoo all over. The suds burned the fresh scrapes on my lower back, a vivid reminder of my near death in the alley, and when I got back to the bedroom, shivering in my towel, my sister was still sound asleep in the full-size bed we shared.

“Melanie. Get up.” I nudged the mattress with my foot, and she rolled onto her stomach.

“Go away, Nina.” She buried her face in the pillow without even opening her eyes.

“Up!” I tossed the blanket off her, holding my towel in place with one hand, and my sister finally sat up to glare at me.

“I’m not going. I’m sick.” She swiped at yesterday’s mascara and eyeliner, already smeared across both her pale cheek and her pillow.

I felt her forehead with the back of one hand while new goose bumps popped up on my arms, still damp from the shower. “You’re not hot. Get up. Or would you really rather be here with Mom all day?”

Melanie mumbled something profane under her breath, but then she stumbled into the hall. Even half-asleep, she remembered to tiptoe over the creaky floorboard in front of Mom’s room on her way to the bathroom.

When we let our mother sleep, we were rewarded with benign neglect. The alternative was much less pleasant.

I was buttoning my school uniform shirt when Melanie came back from the bathroom, pulling a brush through her long, pale hair still dripping from the shower. She looked her age, with her face scrubbed and shiny. Fifteen and fresh. Innocent. Without the eyeliner she’d taken from the Grab-n-Go and the lipstick our mother had forgotten she even owned, Mellie looked just like all the other schoolgirls in our white blouses and navy pants—shining beacons of purity in world that had nearly been devoured by darkness a century ago.

We were living proof that the Church knew best. That the faithful only prosper under the proper spiritual guidance. And about a dozen other similar lines of bullshit the sisters made us memorize in kindergarten.

“Today’s the day,” I said when she handed me the brush. I pulled it through my own thicker, darker hair. “I’m really going to do it.” I’d almost forgotten what today was, thanks to the demon in the alley, but cold showers have a way of bringing reality into crisp focus.

“Do what? Admit that you’re a hopeless stick-in-the-mud who never lets herself have any fun?” She tugged the last pair of school pants from a hanger in the closet and shoved her foot through the right leg. Thank goodness we wore the same size, because we never could have afforded two sets of uniforms on our own, and if the Church found out our mother wasn’t working, they’d take us away.

Melanie wouldn’t make it in the children’s home. The sisters were too watchful, and she had become mischievous and careless under what the Church would characterize as neglect on our mother’s part.

I’d characterize it like that too. But I’d say it with a smile.

“I think you’re having enough fun for both of us, Mel.” Sometimes it didn’t feel possible that we were only a year and a half apart. It’s not that Melanie didn’t pull her own weight; it’s that she had to be reminded to help out. Constantly. If I didn’t beg her to take the towels to the laundry on Saturdays, we’d have to air dry all week long.

“So, what’s so great about today?”

I didn’t get eaten in the alley behind the Grab-n-Go. But there were only so many secrets my sister could keep at one time, and our mother took up most of those spots all on her own.

I took a deep breath. Then I spat the words out. “I’m going to pledge.”

Melanie froze, her pants still half buttoned. “To the Church?”

“Of course to the Church.” I tucked in my blouse, then pulled hers off its hanger. “We talked about this, Mellie.”

“I thought you were joking.” She grabbed a bra from the top drawer and took the shirt I held out by the neatly starched collar.

“I don’t have time for jokes. Why else would I spend all my free time working in the nursery?”

“For the money.” As she buttoned her blouse I brushed sections from the front of her hair to be braided in the back. She hated the half braid, but it made her look modest and conventional, and sometimes that demure disguise was the only thing standing between my mischievous sister and the back of the teacher’s hand. “The same reason I watch Mrs. Mercer’s brats after school and tutor Adam Yung on Saturdays.”

I glanced at her in the mirror with eyebrows raised. “You get credit for the babysitting.” The Mercer kids really were brats, and she wouldn’t have gone near them without a cash reward. “But we both know why you tutor Adam, and it’s not for the money.” He didn’t even pay her in cash—Adam usually came bearing a couple of pounds of ground beef or, in warmer weather, a paper bag of fruits and vegetables from his mom’s garden. Which we’d learned to ration throughout the week.

He’d never said anything, but I always got the impression that his mother sent payment in the form of perishables to make sure our mother couldn’t spend Mellie’s wages on her “medicine.” And to make sure we ate.

“Stop changing the subject.” She scratched her scalp with one finger, loosening a strand I’d pulled too tight. “You want to pledge to the Church just so you can teach?”

I didn’t want to pledge to the Church for any reason. But … “That’s the way it’s done, Mellie.” All schools were run by the Church, and all teachers were either ordained Church pledges or fully consecrated senior members. Same for doctors, police, soldiers, reporters, and any other profession committed to serving the community.

Adam’s dad said they used to be called civil servants—back when there was civil government.

Melanie took the end of her braid from me. “Don’t you think the world has enough teachers?”

“No, as a matter of fact—”

“You know what the world really needs?” She turned to watch me through eyes wide with excitement as she wound the rubber band around the end of her hair. “More exorcists. I mean, if you’re determined to damn yourself to a life of servitude, communal living, and celibacy, wouldn’t you rather be slaying demons than wiping noses on kids that aren’t even yours? You’re gonna need some way to work off all that sexual frustration.”

“Don’t swear, Mel,” I scolded, but the warning sounded hollow and hypocritical, even to my own ears. We both knew better than to curse in public, but there was no one at home to hear or report us. “Profanity is a sin.”

Melanie rolled her eyes. “Everything worth doing is a sin.”

“I know.” And honestly, it was kind of hard for me to worry about the state of my immortal soul when my mortal body’s need for food and shelter was so much more urgent.

I plucked the two slim silver rings from the top of our dresser and tossed her one. Melanie groaned again, then slid her purity ring onto the third finger of her right hand while I did the same. “Nina Kane” was scratched into mine because I’d “misplaced” it four times during the first semester of my freshman year and Sister Hope had engraved my name on the inside to ensure that it would be easily returned to me.

Ours weren’t real silver, and they certainly weren’t inlaid, like Sarah Turner’s purity ring. Ours were stainless steel, plucked from the impulse-buy display at the Grab-n-Go one afternoon when I was fourteen, while Melanie distracted the clerk by dropping a half-gallon of milk in aisle one.

Fortunately, the sisters didn’t care where the rings came from or what they’d cost, so long as we wore them faithfully beginning in the ninth grade as a symbol of our vow to preserve our innocence and virtue until the day we either gave ourselves to a worthy husband or committed to celibate service within the Church.

I knew girls who took that promise very seriously.

I also knew girls who lied through their teeth.

I didn’t know a single boy who’d ever worn a purity ring. Evidently, their virginity was worth even less than the stolen band of steel around my finger.

I grabbed my satchel on my way out of the room, and our conversation automatically paused as we passed our mother’s door. In the kitchen, I pulled the last half of the last loaf of bread from an otherwise empty cabinet, and Melanie frowned with one hand on the pantry door, staring at the calendar I’d tacked up to keep track of my erratic work schedule—I worked whenever the nursery needed me. “What’s today?”

“Thursday.”

“Thursday the fourth?” Her frown deepened, and I had to push her aside to grab a half-empty jar of peanut butter from the nearly bare pantry. “It can’t be the fourth already.”

“It is, unless four no longer follows three. Why?” I glanced at the calendar and saw the problem. “History test?”

“What?” Melanie sank into a rickety chair at the scratched table. “Oh. Yeah.”

“You didn’t study?” I set a napkin and the jar of peanut butter in front of her, then added a butter knife and one of the two slices of toast as they popped up from the toaster.

She shrugged. “It’s just a fill-in-the-blank on the four stages of the Holy Reformation.” But the way she spread peanut butter on her bread, her gaze only half focused, said she was worried.

“And those stages would be …?”

Melanie sighed. “The widespread decline of common morals, the subsequent onslaught of demonic forces, the glorious triumph of the Church over the worldwide spiritual threat, and the eventual unification of the people under a single divine ministry.” She was quoting the textbook almost verbatim.

“Good. Come on.” I took the knife from her and made my own breakfast, then tossed Melanie a modest navy sweater and herded her out the back door, where the town perimeter wall was easily visible between the small houses that backed up to ours. The wall was solid steel plating fifteen feet tall, topped with large loops of razor wire. In the middle of the night, I heard the metal groan with every strong gust of wind. I saw the glint of sun on razor wire in my dreams.

But clouds had rolled in since my predawn activities, and the sky was now gray with them.

“December eighth, 2034,” I said around a mouthful of peanut butter and bread as we rounded the house and stepped over the broken cinder block hiding the emergency cash I kept wrapped in a plastic bag. If Mom knew we had money, she’d spend it on something less important than heat and power, two resources I greatly valued.

“Um … the first televised possession, caught on film at a holiday parade, before the Church abolished public television to support and protect the moral growth of the people.” Melanie shoved one arm into her sweater sleeve, then transferred her toast to the other hand and pulled the other half of her cardigan on over her satchel strap. “So, how dangerous could secular programming have been, anyway? It’s just a bunch of videos, like the discs in Mr. Yung’s basement, right? Stories being acted out, like we used to do when we were kids?”

“I guess.” But according to the Church, those videos tempted people to sin.

Mr. Yung had an old TV and a disc player that still worked. I’d seen one of his videos once, but the disc was badly damaged, so I only caught glimpses of couples swaying in sync with one another, dressed in snug clothes. At the time, I’d been scandalized by the sight of boys and girls in open physical contact with one another—those would be secret shames in our postwar world. But the adults in the video didn’t seem to care, and no one was driven to wanton displays of flesh or desire, that I could see.

There was no sound on the video, though, so I couldn’t hear what kind of music they’d had or what they were saying.

Maybe the sin and temptation were more obvious in the parts I couldn’t hear.

We turned left on the cracked sidewalk in front of our house, and I eyed the dark clouds in the sky, struggling to bring my thoughts back on task. “September twenty-ninth, 2036.”

Melanie held her toast by one corner. She still hadn’t taken a bite. “The first verified exorcism. Established worldwide credibility for the Unified Church, whose exorcist—the great Katherine Abbot—performed the procedure in front of a televised audience of millions.”

“Good. June—”

“Did you know that wasn’t even her real name? “Melanie said suddenly.

“What wasn’t whose name?” We turned left again and followed the railroad tracks between the backyards of the houses a block over from ours. The train hadn’t run since long before I was born, but little grass grew between the rails, which made it an easy shortcut on the days we were running late. Which was most days, thanks to my sister.

“Katherine Abbot. Her name wasn’t really Katherine. The Church renamed her because they thought her real name didn’t sound serious enough, or holy enough, or something like that.”

“So what was her real name?”

Melanie shrugged, and her uneaten toast flopped in her hand. “I don’t know.”

“Then how do you know it wasn’t Katherine?”

“Adam told me.”

“Adam, who needs your help to add double digit numbers?” I said as we cut through the easement between two yards and back onto the street.

“He’s bad at math, not history. His dad says the Church does it all the time—changes facts. Mr. Yung says history is written by the victor, and if the elderly don’t pass down their memories, eventually there won’t be anyone else left alive who knows how the war was really fought.”

I stopped cold on the sidewalk and grabbed her arm, holding so tight she flinched, but I couldn’t let go. Not until she understood. “Melanie, that’s heresy,” I hissed, glancing around at the houses on both sides of the road. Fortunately, the street was deserted. “If Adam Yung and his father want to risk their immortal souls”—or more accurately, their mortal lives—”by questioning the Church, that’s their business. But you stay out of it.”

Skepticism and profanity were largely harmless in private, and goodness knows I couldn’t claim innocence on either part. But the more often they were indulged, the more likely they were to be overheard. And reported. And punished.

“You’re going to have to tutor him in public. At the laundry, or the park, or something.” Anywhere public exposure would keep him from filling my impressionable sister’s head with dangerous thoughts she couldn’t resist sharing with the rest of the world.

I wanted to tell her to stop tutoring him, but frankly, we needed the food.

“Why aren’t you eating?” I glanced pointedly at her untouched breakfast.

“I told you. I don’t feel good.” She scowled and pulled her arm from my grip. “Next date.”

“Um … June 2041.” I pushed her toast closer to her mouth, and she finally took a bite.

“The Holy Proclamation, establishing the Unified Church as the sole political and spiritual authority,” she said, with her mouth still full.

“Okay, let’s backtrack.” I made a gesture linking her breakfast and her face, and Melanie reluctantly took another bite. “May twelfth, 2031.”

“The Day of Great Sorrow.” Her face paled, and she chewed in solemn silence for several seconds before elaborating. “The day the number of stillbirths officially surpassed the number of live births. A day of mourning the world over. The Day of Great Sorrow led to the realization that the well of souls had run dry, which led to the discovery of demons among us. Which then led to the Great Purification, undertaken by the Unified Church, and the dissolution of all secular government in the Western Hemisphere. Right?”

“That’s a bit simplistic as a summary….” The discovery of demons was a particularly grisly time in human history, and the various factions of our former government didn’t disband voluntarily or peacefully. “But probably good enough for a tenth-grade history test. Eat your toast.”

We could see the school compound by then, behind its tall iron gate. She couldn’t take food inside, and we had only minutes until the bell.

“Here. Take half.” Mellie ripped her bread in two and gave me the bigger piece. “I can’t eat it all.”

I shoved the bread into my mouth and chewed as fast as I could—we couldn’t afford to waste perfectly good food—and I’d just swallowed the last of it when the bell started ringing.

“Come on!” I pulled her with me as I raced down the sidewalk, and we slid through the gate a second before it rolled shut behind us.

“Cutting it close again, Nina,” Sister Anabelle said as she locked the gate, her skirt swishing around her ankles beneath the hem of her cassock.

“My fault!” Melanie called over one shoulder, racing toward her first class in the secondary building, her hair flying behind her. “Gotta go!”

“What do you have this morning?” Anabelle fell into step with me as she tucked her key ring into a pocket hidden by a fold in her long, fitted Church cassock—light blue for teachers. Anabelle’s robes were very simple and plain because she was still a pledge, but once she was consecrated, they would be embroidered in elaborate navy swoops and flames, signaling her status and authority to the entire world.

“Um … I have kindergartners today.” All seniors began the day with an hour of service. I’d been selected as an elementary school aide because I already had experience with kids, from working in the children’s home on weekends.

“Have you given any more thought to making an early commitment to the Church? I think you’d make a wonderful teacher.”

I glanced at the brand on the back of her right hand—four wavy lines twisting around one another to form a stylized column of fire, burned into her flesh the day she’d pledged. A permanent mark to seal a permanent choice.

Anabelle’s brand was a simplified version of the seal of the Unified Church, displayed on flags, official documents, currency, and the sides of all public vehicles. Each individual flame represented one of the sacred obligations, and together they formed the symbolic blaze with which the Church claimed to have rid the world of evil.

Except for the degenerates roaming unchecked in the badlands and the demons still resisting purification in several volatile regions in Asia.

But no one was worried about any of that. Not openly, anyway. The Church had it all under control—they told us so every day—and the only time willful ignorance didn’t qualify as a sin was when the Church didn’t want us to know something.

Which was why Melanie couldn’t understand my determination to pledge. But Mellie and I were living different lives, with different obligations and responsibilities. She had three more years to read illicit books and pretend to care about math while she tutored Adam Yung while wearing stolen mascara.

I had a deadbeat mother to hide from the Church, utility bills to pay, and a decorum-challenged little sister to shield from the watchful eyes of the school teachers. The Church represented my best shot at holding all that together until Melanie was old enough and mature enough to fend for herself.

The catch? Church service was forever. Mellie would grow up and have a life of her own, but I would not. I would belong to the Church until the day I died, and even when that day came, they would decide what would become of my immortal soul.

I’d been mentally fighting the choice for months, scrambling to find some other way to make things work, but my miracle had failed to materialize, and wasting the rest of my senior year wasn’t going to change that.

I couldn’t officially join until I turned eighteen, which was still a year and four days away, but early commitments were encouraged, and the earlier I pledged, the more likely I was to get my first-choice assignment.

Teaching. In New Temperance. Near Melanie. That was the whole point of pledging, for me.

“I was thinking of doing it during the afternoon service.” I took a deep breath and swallowed a familiar wave of nausea. “Today.”

“Oh, Nina, I’m so happy for you!” Anabelle threw her arms around me as if nothing had changed since I was a needy twelve-year-old, desperate for friendship and advice, and she was a senior, already pledged to the Church and assigned to mentor the girls in my seventh-grade class. Anabelle knew about my mother’s problem—she’d known even way back then—but she hadn’t told anyone. She trusted me to take care of Melanie and to ask for help when I needed it.

Sometimes talking to her still felt like talking to an older classmate, but the powder-blue cassock and the brand on the back of her hand were stern reminders of her new reality.

She was Sister Anabelle now. The Church owned her, body and soul.

Soon it would own me too.

“I have to admit, I’m happy for me too,” Anabelle said, and her smile was reassuring. If she loved her job so much, pledging to the Church couldn’t be that bad, right? “I was hoping you’d decide to pledge before the consecration. I didn’t want to miss your big day!”

“Oh, I completely forgot!” Anabelle had been selected for consecration into the leadership levels of the Church just five years after she’d joined, much sooner than the average. Unfortunately, after the annual ceremony—just a few days away—she would be transferred to another town, to learn under new guidance and to experience more of the world than New Temperance had to offer.

I could hardly imagine school without Anabelle. Even with our age difference and her Church brand standing between us, she was the closest thing I had to a friend.

We were three doors from the kindergarten wing when the rain started, an instant, violent deluge bursting from the clouds as if they’d been ripped open at some invisible seam. Even under the walkway awning, we were assaulted by icy rain daggers with every gust of wind. Anabelle and I sprinted for the door, but the knob was torn from my hand before I could turn it.

The door flew open and Sister Camilla marched past us into the rain, dragging five-year-old Matthew Mercer by one arm. If he was crying, I couldn’t tell—he was drenched in less than a second.

“Blasphemy is an offense against the Church, an insult to your classmates, and a sin against your own filthy tongue!” Sister Camilla shouted above a roll of thunder.

Yes, Matthew Mercer was a brat, and yes, he had trouble controlling his mouth, but he was just a kid, and everything he said he’d probably heard from his parents.

I stepped out from under the awning and gasped as the freezing rain soaked through my blouse in an instant. Anabelle pulled me back before I could say something that would probably have landed me in trouble alongside the kindergartner.

“Blasphemy is a sin,” Sister Anabelle reminded me in a whisper.

Of course blasphemy was a sin. A lesser infraction than fornication or heresy, but a grievous offense a strict matron like Sister Camilla would never let slide. Even in a five-year-old.

Especially in a five-year-old who’d already demonstrated a precocious gift for profanity.

Anabelle and I could only watch, shivering, as Sister Camilla dragged Matthew onto the stone dais in the center of the courtyard, then forced him to kneel. She was still scolding him while she flipped a curved piece of metal over each of his legs, just above his calves, then snapped the locks into place, confining the five-year-old to his knees in the freezing rain.

The posture of penitence. Voluntarily assumed, it demonstrated humility and submission to authority. And contrition. Used as a punishment, it was a perversion of the very things it stood for, just like anything accomplished by force.

In third grade, I’d once knelt in the posture of penitence in the middle of the school hall for four hours for turning in an incomplete spelling paper.

I’d never failed to finish an assignment again.

Sister Camilla marched toward us in the downpour, wordlessly ordering us inside with one hand waved at the building. At the door, I looked back to see Matthew Mercer bent over his knees, his forehead touching the stone floor of the dais, his school uniform soaked. He’d folded his arms over the back of his head in a futile attempt to protect himself from the rain.

“Pray for forgiveness,” Sister Camilla called to him over her shoulder. “And hope the Almighty has more mercy in his heart than I have in mine.”

Well, I thought as the door closed behind us, he certainly couldn’t have any less.

THREE (#u5bc4caf5-9a93-5657-986c-d7475adf932a)

“Okay.” I crossed my legs and angled them to one side, trying to get comfortable in a chair built for five-year-olds. On the other side of the room, one of my fellow seniors had her own group of six kids assembled at the reading center while Sister Camilla taught math to six more at a table covered with little plastic counting cubes. I was in charge of the faith unit. “Who can name one of the four obligations of the people to their Church?”

Five chubby little hands shot into the air; five eager faces stared at me, hoping to be called upon. At some point between the ages of five and fifteen, that eagerness would be replaced with indifference, but in kindergarten, they still cared. They still wanted to please and to be rewarded for their effort.

“Elena.”

All five hands sank and four frowns emerged, while Elena beamed at me from her chair in the semicircle. “Devotion!” Her brown eyes sparkled with triumph. “That means we love the Church and we’ll love it forever!”

“Good!” But on the inside, some vulnerable part of me shriveled a little more at her enthusiasm for a child’s happy lie, which would surely mature into an adult’s bitter burden. “Who else?” The other four hands shot up again. “Dillon?”

He picked at the cuff of his white school shirt. “Obedience.”

“And what does that mean?”

“It means you have to do what the Church says, even if you don’t want to. Just like at home, when your mom says you have to eat your peas, even though they’re yuck.”

I smiled at him, and my knee banged the underside of the short table when I tried to uncross my legs. “That’s exactly right.” But the Church’s “peas” were usually much more difficult to swallow. “And the third obligation?” The last three hands went up. “Jessica?”

“Penti … Penna … Pen …”

“Penitence,” I finished for her. “Good. And what does that mean?”

“It means that when you do something wrong, you have to feel bad about it. Real bad. And you gotta try to fix it.”

“That’s right. And—”

“Like with Matthew.” Elena’s smile faded and her little forehead furrowed. “He didn’t feel bad about what he said, so Sister Camilla made him feel bad.”

I glanced at Matthew Mercer’s empty chair, at the end of our semicircle. The rain was coming down so hard that I couldn’t see him through the window. I could only see gray misery and the steady pelting of rain against the glass.

“Okay, there’s one more.” I dragged my attention back to the kids in front of me, in their white shirts and navy pants, smaller versions of my own uniform. “The people owe the Church devotion, obedience, penitence, and what? Robby? Can you tell us?”

“He got the easy one …,” Jessica whispered, and I frowned at her.

“Worship,” Robby said. “That means you gotta love the Church.”

“Good.” At their age, faith was more about memorization than anything. Fortunately, five-year-olds have great memories. “Now let’s move on to something more fun. Who can tell me what we learned yesterday about soul donors?”

Hands shot into the air, and for the next few minutes, the kids explained to me that since the Great Purification a century ago, donors were necessary because babies without souls die within an hour of their birth.

“Who can tell me why there aren’t enough souls to go around anymore?”

Robby spoke quietly. The tone of our unit had changed, and he looked scared. “Demons ate them.”

I nodded solemnly.

Actually, demons consumed the souls of those they possessed. But that distinction was hard to explain to small children.

Degenerates were easy to identify. Fresh demonic possessions were much, much more difficult to recognize, because when a demon possesses a human, it has access to its victim’s memories. Most demons are very good at impersonating their victims. They do it for years, until the soul of the victim has been completely devoured.

Once that happens, if the demon can’t find a new host, it becomes stuck in the soulless body, which begins to mutate and degrade, both physically and mentally. Eventually, those soulless, end-stage possessions become degenerates—mindless mutated monsters with inhuman strength and speed, and demonic appetites. They stalk the shadows in search of new souls, but because they’ve lost most mental function, instead of simply possessing a new host, they tear the poor victim to pieces, literally devouring human flesh in search of that vital soul.

But those details aren’t taught to five-year-olds. In kindergarten we keep it simple.

“Today we’re going to talk about the shortage of souls and the generational obligation of the people.” That was a mouthful for a five-year-old, but even kindergartners had been hearing those phrases for most of their lives. “Do you all know who your donors were?”

Robby’s hand shot up, but he answered before I could call on him. “My grandpa was my donor. I’m his namesake, so I get to put flowers on his grave every year on my birthday. But my mom cries, even though I got to live.”

“I’m sure they’re happy tears.”

I was lying. People don’t cry in graveyards because they’re happy. But sometimes you have to lie to little kids. Sometimes you have to lie to not-so-little kids too.

I turned to Jessica, who was twirling a thin strand of dark hair around her finger. “What about you, Jessie? Do you know who your donor was?”

She shook her head. “My donor was from the public registry.” She said the words slowly. Carefully. Reverently.

I blinked at her in surprise. “Well then, you’re extra lucky, aren’t you?” I tried not to think about how nervous her mother must have been toward the end of her pregnancy.

Family donations are the norm, and most donors are memorialized in the new child’s name, or by the celebration of the donation along with the child’s birthday every year.

It’s considered an honor for the elderly to give up their lives and their souls at the moment of a child’s birth so the next generation can live. It’s also considered an obligation. In fact, in most cases, the Church won’t grant a parenting license until the prospective parents have a family donor lined up. The public registry is for emergencies. For cases when the donor dies before it’s safe to induce the baby’s birth, and for rare accidental pregnancies, when there is no family member willing to donate a soul for a child he or she will never see.

People who haven’t already promised their souls to a family member’s child are added to the public registry at the age of fifty and instructed to get their affairs in order. It’s a short list. Most people want their souls to stay in the family, and those who want to grow old sometimes promise a donation to the child of a niece or nephew who’s still several years away from marriage, and even farther from parenthood.

Selfish? Yes. But until the Church comes up with a law to stop it, donor procrastination is also perfectly legal.

When a baby nears birth without a promised soul, it’s assigned a donor from the top of the public registry. Rarely—tragically—a town’s public registry will sit empty for a few days, and inevitably during that time, babies are stillborn for lack of a soul.

“Do you do anything special for your donor on your birthday?” I asked Jessica.

“We give thanks and set a place for her at my birthday party. No one sits in that chair, even though she’s not really there. Mommy says it’s symbiotic.”

I hid a smile. “I think you mean ‘symbolic.’ “

“Yeah.” Jessica turned to her classmates with an air of authority. “ ‘Symbolic’ means no one can sit in that chair, even though it’s empty.”

Across the room from our learning center, the classroom door opened and I glanced up from my group of kindergartners to find Sister Anabelle standing in the doorway.

“Sister Camilla, could I please borrow Nina for the rest of the hour?”

Sister Camilla nodded, and Anabelle gestured for me to hurry, so I passed out parable-themed coloring sheets and crayons for my group, then scurried into the hall.

Anabelle closed the door behind me. “They’re about to start the sophomore class physicals. I thought you might want to spend your service hour there today, since Melanie’s …” She frowned at my blank look. “Mellie didn’t tell you?”

“No.” But with that new bit of information, the pieces fell into place in my head. No wonder my sister was nervous that morning. The problem wasn’t her history test, it was her physical exam.

My sophomore physical was the single worst day of my life. Even compared to a degenerate attack in a dark alley.

“Come on.” Anabelle grabbed my arm and tugged me down the hall. “They’re about to start the assembly.”

We got there just as the last of the tenth-grade girls filed into their seats in the auditorium, wide-eyed and obviously scared. The boys would be addressed separately, and I wondered if they would be half as nervous as the girls were. There was no whispering or nudging in line. No one played with anyone else’s hair. No one scribbled on incomplete homework papers or rushed to finish the assigned reading. They just stared at the stage, where a nurse in her pristine white slacks and matching cassock—the bloodred embroidery meant she was consecrated—stood next to the acting headmaster, Sister Cathy.

The girls looked terrified.

I knew exactly how they felt.

Anabelle and I stood against the back wall with several other teachers and volunteers, all staring out over the mostly empty auditorium. The sophomore girls took up less than three full rows.

When Sister Cathy stepped up to the podium, my stomach began to churn.

“Good morning, girls,” she said, and we all flinched when the microphone squealed. Sister Cathy repositioned it, then started over. “Good morning, girls. As you all know, today is your annual physical. As you may also know by now, the tenth-grade physical is a little different from the exams you’ve gotten in previous years. Today, in addition to assessing your general health and development, we will also be conducting your first reproductive assessment.”

My hands felt cold. And damp.

Sister Cathy made it sound perfectly reasonable. Civilized. Routine. As if there were no emotion involved. But the truth was actually brutal for the girls sitting in those chairs, hands clenched in terror. By the end of the day, every girl in Melanie’s class would be declared either fit or unfit to procreate.

Those declared fit would be given a second assessment before marriage, and a third when they applied for a parenting license.

Those declared unfit would be scheduled for sterilization. Immediately.

My stomach twisted again, as if my breakfast wanted to come back up. I closed my eyes and took several deep breaths, and when I looked at the stage again, I realized I’d missed the introduction. I had no idea what the nurse’s name was, or when she’d stepped up to the podium.

“The important thing to remember today, girls, is that the reproductive assessment isn’t personal.” She said it with an air of authority. As if that made it true. “It’s not an assessment of you as a person, or of your ability to love and raise a child. Or even your ability to carry a child. It’s a simple issue of numbers.”

Numbers.

The Church was all about the numbers. I guess they had to be, since our population had been decimated by the horde a century ago. We couldn’t recover most of the souls devoured by the Unclean, and since no one knows how or even if new souls can be created …

“There aren’t enough souls to go around anymore.” The nurse finished my thought out loud, and I realized it didn’t matter what her name was, or what the name of the nurse who’d spoken to my class was, because ultimately, they were both Sister Nurse. This was the same speech countless Sister Nurses all over the country were saying to thousands of fifteen-year-old girls in every town that had survived the onslaught. The same thing Sister Nurses had been saying for more than eighty years, ever since the Church imposed restrictions on reproduction.

“The Unified Church has a responsibility to make sure that the available souls go to the babies with the best chance of survival. That way, virtually all our children live.”

That was a nice way to put it. The truth was that, rather than choose which infants lived or died—because that would be cruel—the Church chose which infants could be conceived.

“The decision is completely fair,” Sister Nurse continued. “It’s based on math and science.”

I wanted to laugh. But I kinda wanted to scream too.

At fifteen years old, I was disqualified for procreation based on a history of allergies, my flat feet, and mild myopia—conditions it wouldn’t be fair to pass along to the next generation. Especially when there were other girls my age with fewer health issues, who could theoretically produce healthier children.

I wasn’t alone. Nearly a third of the girls in my class were declared unfit. We were sterilized that afternoon, in matching white hospital gowns.

Sister Nurse spoke for another five minutes, explaining what the reproductive assessment would entail and reiterating that the girls should not be scared. Then she asked them to stand and form a single-file line.

Nothing good ever happens in a single-file line.

“Nina?” Anabelle put one hand on my shoulder as we followed my sister’s class into the bright hallway. “Are you okay?” I nodded, and she got a good look at my face while the line filed slowly toward the gym, which had been set up with several exam stations separated from one another by thin curtains. Anabelle tugged me into an alcove near the restrooms and lowered her voice to a whisper. “Oh, sweetie, I’m sorry. I completely forgot.” Her frown deepened. “Is that why you want to pledge? Because of your disqualification?”

“No. I’m fine. Really.” Melanie filed past us, near the middle of the line, and my gaze followed her. She looked pale.

She looked terrified.

“You know this isn’t your only choice, right?” Anabelle said. “The Church wants pledges who want to be in service. And you have other options. I know you don’t want retail or factory work, but what about technical school? Cooking? Gardening?”

“I nearly burned the toast this morning, and I killed the bean sprout we planted in second grade.” I dragged my focus from the back of Mellie’s head and made myself look at Sister Anabelle. “And anyway, those aren’t careers. They’re jobs. Dead-end jobs, if you hate what you’re doing.” Like the dead-end existence that was killing my mother slowly, from the inside out.

“Okay, what about college? How are your scores?” Anabelle was irrepressible. “You could wait for the recruitment fair …?”

My scores were fine. But not good enough to get me recruited by a company willing to pay for my education in exchange for my employment. My spare time was spent working, not studying, and without a recruitment scholarship, I didn’t have the money for college. I didn’t even have the money for dinner. The Church would provide for any higher education required for Church service, of course. But only once I’d pledged. Which brought us back to the starting point of this logic merry-go-round.

“You could still marry …,” Anabelle suggested softly, as the last of the sophomores filed past, their shoes whispering on bright white linoleum tile. “It won’t matter what you do for a living if you’re in love, right?”

I gaped at her, momentarily unable to hide my contempt.

Yeah, in a few years I could marry. If I could find a husband who either didn’t want children or had also been sterilized. But what kind of life would that be? Disqualified for parenthood because of my flat feet and occasional runny nose. Disqualified for everything but retail and factory work because I couldn’t afford an education.

Could love make that kind of misery bearable? The only thing I knew about love was that Mellie read about it in her taboo books—along with a host of other improbable fantasies.

Joining the Church to become a teacher was the only way I could think of to stay near my sister yet have a life and a career of my own. Well, a career, anyway.

“I want to pledge, Anabelle,” I insisted, speaking over the voice inside me that argued otherwise.

She studied me for a second, and she must have bought my sincerity, because then she smiled and squeezed my arm. “Great! It’s good work, Nina. And I know you love the kids.”

“Yeah, I—”

“Miss Kane, please step back into line,” Sister Cathy said, and the rest of my sentence died on my tongue at the mention of my last name. I thought she was talking to me, until I looked up to see my sister standing alone in the middle of the hall instead of against the wall in line with the other girls.

Melanie stared at the floor, her arms stiff at her sides, and though I couldn’t see her face, I recognized her posture. She was trapped between an idea and its execution, like when she was little and she realized she could sneak an extra cookie from the package but knew she shouldn’t. Any second, she would either step back into line or … she wouldn’t. She hadn’t yet decided.

“Melanie Kane, get back in line. Now.” Sister Cathy’s voice was sharper this time, and suddenly everyone was watching. Mellie looked at her. Then she looked at the line of her classmates. Then she looked at the door leading into the courtyard, where rain still poured in thick gray sheets.

My heart hammered in my chest, and I felt like I was on that precipice of disobedience with her.

Get back in line, Mellie.

Running wouldn’t get her out of the physical, and it would get her into serious trouble. The kind of trouble that would require a conference with our mother. Which would quickly land us in Church custody.

Melanie’s right hand twitched, and I knew what she’d decided a fraction of a second before she lurched for the double glass doors and threw her full weight at them. The doors flew open, and she disappeared into the rain.

There was a collective gasp from the sophomore class and a startled yelp from Sister Cathy as a gust of wind and rain pelted her navy-embroidered pale blue cassock in the two seconds it took the doors to fall shut in my sister’s wake. Then there was silence, except for a clap of thunder and the steady, loud patter of rain on the roof.

“Find her!” Sister Cathy shouted, soaked and obviously furious, and two of the sophomore class teachers sprinted for the exit, their cornflower cassocks flapping behind them.

I started to follow, blood racing through my veins, spurring me into action, but Sister Anabelle grabbed my arm and hauled me into the restroom alcove again.

“She’s just scared,” I said.

“I know,” Anabelle whispered. “It would be better if you find her and get her to come back voluntarily. Ready to atone. Disobeying a Church official is a sin, Nina.”

“I know.” Melanie was drawn to trouble like a cat to raw meat—she thrived on it—and I’d always known that eventually she’d make a mistake I couldn’t fix. I’d just hoped “eventually” would come a little later in life. And that it wouldn’t involve my sister disobeying a Church official in front of dozens of witnesses, then fleeing the scene.

What the hell was she thinking?

“Is there somewhere she goes when she’s upset?” Anabelle asked.

“Not lately.” But when we were little … I glanced over my shoulder at the sophomores still filing into the gym four at a time. “I’ll find her. Can you cover for me?”

“Of course. Go on.”

I made myself walk away from the gym, then into the courtyard through a different door, when I really wanted to run. The rain had slowed a little, but the day looked gray, viewed through the steady drizzle, and my hair was drenched again by the time I got to the dais. The only sounds were the constant loud patter of raindrops, the occasional roll of thunder, and the quick tap of my school shoes on the sidewalk.

Matthew Mercer looked up from the dais when he heard me coming, and one glance at his rain-soaked misery urged me to move faster.

If they’d force a five-year-old to kneel all day in the rain for blasphemy, what would they do to a disobedient fifteen-year-old fugitive? I couldn’t remember anyone else defying the Church so openly, except for … Clare Parker.

My stomach clenched around my breakfast at the memory.

One day, the year I was nine, Clare had refused to kneel for worship. They gave her three chances. When she still refused, Brother Phillip said refusing to recognize the Church’s authority was the first sign of possession. He called in an exorcist, and two hours later, Clare was sentenced. The exorcist said that since her possession was recent, her soul could be returned to the well of souls—if it were purified by fire.

They forced her to her knees on the dais, closed the steel cuffs above her calves, then burned her alive in front of the entire school.

She was seventeen years old.

What if they thought Melanie was possessed?

Terror pumped fire through my veins and pushed my feet faster. At the rear entrance to the administration building, I turned to make sure no one was watching, then slipped inside. My shoes squeaked on the tile and left wet footprints, but there was nothing I could do about that.

Careful not to slip, I snuck through the back hall, then ducked into the laundry room. When Mellie was little, she loved to hide in the bundles of freshly laundered sheets before they were folded and distributed in the children’s home attached to our school. The laundry was the only place I could think of to look for Mellie on campus, and at first I didn’t see her.

I’d almost decided to climb over the fence and go look for her at home, when the pile of clean white sheets in a huge wheeled cart moved.

“Melanie? It’s me. Come on out.”

But she didn’t move or make a sound, so I had to pull the sheets off her one by one and pile them on a table until I found my sister curled up in a ball at the bottom of the cart. Her hair was soaked, her braid destroyed. Her face was red and swollen from crying, and the terror in her eyes made her look about ten years old.

“Mellie, you have to go back. It’ll be okay if you apologize and take your punishment.”

Fasting? A week of silence? Public lashing? Any of those would be better than suspicion of possession.

“It’s not going to be okay.” Melanie sat up, sniffling, and wiped her nose with the back of one hand.

“Not if you don’t get up, it won’t. Hurry, before they decide you’re possessed.” Any reasonable person could see that she was just scared and upset. But the Church saw what it wanted to see, and it wouldn’t want to see a fifteen-year-old it simply couldn’t control.

Melanie shook her head slowly, and two fat tears rolled down her cheeks as she stared up at me. “I’m not possessed, Nina,” she said, her voice raw and hoarse. “I’m pregnant.”