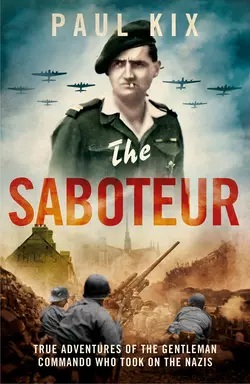

The Saboteur: True Adventures Of The Gentleman Commando Who Took On The Nazis

Paul Kix

In the tradition of ‘Agent Zigzag’ comes a breathtaking biography of WWII’s ‘Scarlet Pimpernel’ as fast-paced and emotionally intuitive as the best spy thrillers. This celebrates unsung hero Robert de La Rochefoucauld, an aristocrat turned anti-Nazi saboteur, and his exploits as a British Special Operations Executive-trained resistantA scion of one of the oldest families in France, Robert de La Rochefoucauld was raised in a magnificent chateau and educated in Europe’s finest schools. When the Nazis invaded and imprisoned his father, La Rochefoucauld escaped to England and was trained in the dark arts of anarchy and combat – cracking safes, planting bombs and killing with his bare hands – by a collection of SOE spies. With his newfoundskills, La Rochefoucauld returned to France and organized Resistance cells, blew up fortified compounds and munitions factories, interfered with Germany’s wartime missions and executed Nazi officers. Caught by the Germans, La Rochefoucauld withstood months of torture and escaped his own death sentence, not once but twice.More than just a fast-paced, real-life thriller, The Saboteur is also a deep dive into an endlessly fascinating historical moment, revealing the previously untold story of a network of commandos, motivated by a shared hatred of the Nazis, who battled evil and bravely worked to change the course of history.

Copyright (#ub73d4e94-6ac9-5940-b968-e053d0fbfebe)

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollins.co.uk (http://www.WilliamCollins.co.uk)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017

Copyright © Paul Kix 2017

Cover images planes and street © Alamy; Soldiers © Getty Images

Cover design by Leo Nickolls

Paul Kix asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780007553808

Ebook Edition © December 2017 ISBN: 9780007553815

Version: 2017-11-29

Dedication (#ub73d4e94-6ac9-5940-b968-e053d0fbfebe)

For Sonya, as always

Contents

Cover (#u2c7e12a9-c4fc-5cd3-bdd6-25ce46d19e95)

Title Page (#u8db5d45b-5b04-5af8-87dc-403878618c36)

Copyright

Dedication

Author’s Note

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Notes

About the Author

About the Publisher

AUTHOR’S NOTE (#ub73d4e94-6ac9-5940-b968-e053d0fbfebe)

This is a work of narrative nonfiction, meant to relay what it was like for Robert de La Rochefoucauld to fight the Nazis from occupied France as a special operative and résistant. I relied on a few primary sources to tell this story, most notably La Rochefoucauld’s memoir, La Liberté, C’est Mon Plaisir: 1940–1946, published in 2002, a decade before his death. La Rochefoucauld’s family, ever gracious, also gave me a copy of the audio recording in which Robert recounted his war and life for his children and grandchildren. This was great source material, as was a DVD I received, which was directed, edited, and produced by one of Robert’s nephews, and which tells the tale of his storied family, specifically his parents, his nine brothers and sisters, and the courage that Robert himself needed to fight his war. The DVD, like the audio recording, was made for the La Rochefoucauld family to share with successive generations, but Robert’s daughter Constance was kind enough to make me a copy.

I spoke with her and her three siblings at length about their father—in person, over Skype, on the telephone, and by email. I kept contacting them long after I said I would, and kept apologizing for it. But Astrid, Constance, Hortense, and Jean were always amenable and happy to share what they knew. I’m eternally grateful.

This narrative is the result of four years of work, with research and reporting conducted in five countries. I talked with dozens of people, read roughly fifty books, in English and French, and parsed thousands of pages of military and historical documents, in four languages. Despite all this, and no doubt because of the secret nature of La Rochefoucauld’s work, there are certain instances where Robert’s account of what happened is the best and sometimes only account of what happened. Thankfully, in those spots, Robert’s recollections are vivid and reflect the larger historical record of the region and time.

PAUL KIX, JANUARY 2017

PROLOGUE (#ub73d4e94-6ac9-5940-b968-e053d0fbfebe)

His family kept asking him why (#litres_trial_promo). Why would a hero of the war align himself with one of its alleged traitors? Why would Robert de La Rochefoucauld, a man who had been knighted in France’s Legion of Honor, risk sullying his name to defend someone like Maurice Papon, who had been charged, these many decades after World War II, with helping the Germans during the Occupation?

The question trailed La Rochefoucauld all the way to the witness stand, on a February afternoon in 1998 (#litres_trial_promo), four months into a criminal trial that would last six, and become the longest in French history (#litres_trial_promo).

When he entered the courtroom, La Rochefoucauld looked debonair (#litres_trial_promo). His silver hair had just begun to recede, and he still swept it straight back. At seventy-four, he carried the dignified air of middle age. He had brown eyes that took in the world with an ironic slant, the mark of his aristocratic forebears, and a Roman, ruling-class nose. His posture was tall and upright as he walked to the stand and gave his oath and, lowering himself to his seat at the center of international attention, he appeared remarkably relaxed—his complexion even had a bronze tint, despite the bleak French winter. He remained a handsome man, nearly as handsome as he’d been in those first postwar years, when he’d moved from one girl to the next (#litres_trial_promo), until he’d met Bernadette de Marcieu de Gontaut-Biron, his wife and mother of his four children.

On the stand, La Rochefoucauld wore a green tweed check jacket over a light blue shirt and a patterned brown tie. The outfit suited the country squire, who’d traveled to Bordeaux today from Pont Chevron, his thirty-room chateau (#litres_trial_promo) overlooking sixty-six acres in the Loiret department of north-central France. He radiated a charisma that burned all the brighter when set against the gray sobriety of the courthouse. La Rochefoucauld looked better than anyone in the room.

A reputation for bravery preceded him, and almost out of curiosity for why someone like La Rochefoucauld would defend someone like Papon, the court allowed him an opening statement. La Rochefoucauld nodded at the defendant (#litres_trial_promo), who sat in a dark suit behind bulletproof glass (#litres_trial_promo). The makings of wry exasperation curled La Rochefoucauld’s lips as he recalled events from fifty years earlier.

“First, I would like to say that in 1940, although I was very young, I was against the Germans, against Pétain and against Vichy. I was in favor of the continuation of the war in the South of France and in North Africa (#litres_trial_promo).” He was sixteen then (#litres_trial_promo), and came from a family that despised the Germans. His father, Olivier, a decorated World War I officer who’d re-enlisted in 1939 (#litres_trial_promo), was arrested by the Nazis five days after the Armistice (#litres_trial_promo) in part because he’d tried to fight beyond the agreed-to peace. His mother, Consuelo, who ran a local chapter of the Red Cross (#litres_trial_promo), was known to German officers as the Terrible Countess (#litres_trial_promo). On the stand, La Rochefoucauld skipped over almost all of what happened after 1940, the acts of bravery that had earned him four war medals and a knighthood (#litres_trial_promo). He instead focused his testimony on one episode in the summer of 1944 and experiences that greatly compromised the allegations against Papon.

Maurice Papon had been an administrator within the German-collaborating Vichy government. He rose to a position of authority in the Gironde department of southwestern France, whose jurisdiction included Bordeaux. The charge against Papon was that from his post as general secretary of the Gironde prefecture (#litres_trial_promo), overseeing Jewish affairs, he signed deportation papers for eight of the ten convoys of Jewish civilians that left for internment camps in France, and ultimately the concentration camps of Eastern Europe. In total, Vichy officials in the Gironde shipped out 1,690 Jews, 223 of them children (#litres_trial_promo). Papon had been indicted for crimes against humanity.

The reality of Papon’s service was far messier than the picture the prosecutors depicted. Despite Papon’s lofty title, he was a local administrator within Vichy and so removed from authority that he later claimed he didn’t know the final destination of the cattle cars (#litres_trial_promo) or the fate that awaited Jews there. Furthermore, Vichy’s national police chief, René Bousquet (#litres_trial_promo), was the person who had actually issued the deportations. Papon claimed that he had merely done as he was told, that he was a bureaucrat with the misfortune of literally signing off on orders. When the trial opened in the fall of 1997, the historian who first unearthed the papers that held Papon’s signatures, Michel Bergès, told the court he no longer believed the documents proved Papon’s guilt (#litres_trial_promo). Even two attorneys for the victims’ families felt “queasiness” about prosecuting the man (#litres_trial_promo).

Robert de La Rochefoucauld (pronounced Roash-foo-coe) knew something that would further undercut the state’s case against Papon. As he told the court (#litres_trial_promo), in the summer of 1944, he joined a band of Resistance fighters who called their group Charly. “There was a Jewish community there,” La Rochefoucauld testified, “and when I saw how many of them there were, I asked them what was the reason for them being part of this [group]. The commander’s answer was very simple: … ‘They had been warned by the prefecture that there would be a rounding up.’” In other words, these Jewish men were grateful they had been tipped off and happy to fight in the Resistance.

In the 1960s, La Rochefoucauld met and grew friendly with Papon, who was by then Paris’ prefect of police. “I learned he was at the [Gironde] prefecture during the war,” Robert testified. “It was then that I told him the story of the Jews of [Charly]. He smiled and said, ‘We were very well organized at the prefecture.’” Despite La Rochefoucauld’s own heroics, he said on the stand it took “monstrous reserves of personal courage” to work for the Resistance within Vichy. “I consider Mr. Papon one of those brave men.”

His testimony lasted fifteen minutes, and following it one of the judges read written statements from four other résistants, whose sentiments echoed La Rochefoucauld’s: If Papon had signed the deportation documents, he had also helped Jews elude imprisonment. Roger-Samuel Bloch (#litres_trial_promo), a Jewish résistant from Bordeaux, wrote that from November 1943 to June 1944, Papon hid and lodged him several times, at considerable risk to his career and life.

The court recessed until the next morning. La Rochefoucauld walked outside and took in a Bordeaux that was so very different from 1944, where no swastika flags swayed in the breeze, where no people wondered who would betray them, where no one listened for the hard tap of Gestapo boots coming up behind. How to relay in fifteen minutes the anxiety and fear that once clung to a man as surely as the wisps of cigarette smoke in a crowded café? How to explain the complexity of life under Occupation to generations of free people who would never experience the war’s exhausting calculations and would therefore view it in simple terms of good and evil? La Rochefoucauld was beyond the gated entryway of the courthouse (#litres_trial_promo) when he saw Papon protesters move toward him. One of them got very close, and spit on him (#litres_trial_promo). La Rochefoucauld stared at the young man, furious, but kept walking.

What people younger than him could not understand—and this included his adult children and nieces and nephews—was that his motivation for testifying wasn’t really even about Papon, a man he hadn’t known during the war. La Rochefoucauld took the stand instead out of a fealty for the brotherhood, the tiny bands of résistants who had fought the mighty Nazi Occupation. They knew the personal deprivations, and they saw the extremes of barbarity. A silent understanding still passed between these rebels who had endured and prevailed as La Rochefoucauld had. A shared loyalty (#litres_trial_promo) still bound them. And no allegation, not even one as grave as crimes against humanity, could sever that tie.

La Rochefoucauld hadn’t said any of this, of course, because he seldom said anything about his service. Even when other veterans had alluded to his exploits at commemorative parties over the years, he’d stayed quiet. He was humble, but it also pained him to dredge it all up again. So his four children and nieces and nephews gathered the snippets they’d overheard of La Rochefoucauld’s famous war, and they’d discussed them throughout their childhood (#litres_trial_promo) and well into adulthood: Had he really met Hitler once, only to later slink across German lines dressed as a nun? Had he really escaped a firing squad or killed a man with his bare hands? Had he really trained with a secret force of British agents that changed the course of the war? For most of his adult life, La Rochefoucauld remained, even to family, a man unknown.

Now, La Rochefoucauld got in his Citroën (#litres_trial_promo) and began the five-hour drive back to Pont Chevron. Maybe one day he would tell the whole story of why he had defended someone like Papon, which was really a story of what he’d seen during the war and why he’d fought when so few had.

Maybe one day, he told himself (#litres_trial_promo). But not today.

CHAPTER 1 (#ub73d4e94-6ac9-5940-b968-e053d0fbfebe)

One cannot answer for his courage if he has never been in danger.

—François de La Rochefoucauld, Maxims

On May 16, 1940 (#litres_trial_promo), a strange sound came from the east. Robert de La Rochefoucauld was at home with his siblings when he heard it: a low buzz that grew louder by the moment until it was a persistent and menacing drone (#litres_trial_promo). He moved to one of the floor-to-ceiling windows of the family chateau, called Villeneuve, set on thirty-five acres just outside Soissons, an hour and a half northeast of Paris. On the horizon, Robert saw what he had long dreaded.

It was a fleet of aircraft, ominous and unending. The planes already shadowed Soissons’ town square, and the smaller ones now broke from the formation. These were the German Stukas (#litres_trial_promo), the two-seater single-engine planes with arched wings that looked to Robert as predatory as they in fact were. They dove out of the sky, the sirens underneath them whining a high-pitched wail. The sight and sound paralyzed the family, which gathered round the windows. Then the bombs dropped: indiscriminately and catastrophically, over Soissons and ever closer to the chateau (#litres_trial_promo). Huge plumes of dirt and sod and splintered wood shot up wherever the bombs touched down, followed by cavernous reports that were just as frightening; Robert could feel them thump against his chest. The world outside his window was suddenly loud and on fire. And amid the cacophony, he heard his mother scream: “We must go, we must go, we must go! (#litres_trial_promo)”

World War II had come to Soissons. Though it had been declared eight months earlier, the fight had truly begun five days ago, when the Germans feinted a movement of troops in Belgium, and then broke through the Allied lines south of there, in the Ardennes, a heavily forested collection of hills in France. The Allies had thought that terrain too treacherous (#litres_trial_promo) for a Nazi offensive—which is of course why the Germans had chosen it.

Three columns of German tanks stretching back for more than one hundred miles (#litres_trial_promo) had emerged from the forest. And for the past few days, the French and Belgian soldiers who defended the line, many of them reservists (#litres_trial_promo), had lived a nightmare if they’d lived at all: attacked from the sky by Stukas and from the ground by ghastly panzers too numerous to be counted. In response, Britain’s Royal Air Force had sent out seventy-one bombers (#litres_trial_promo), but they were overwhelmed, and thirty-nine of the aircraft had not returned, the greatest rate of loss (#litres_trial_promo) in any operation of comparable size in British aviation history. On the ground, the Germans soon raced through a hole thirty miles wide and fifteen miles deep (#litres_trial_promo). They did not head southwest to Paris, as the French military expected, but northwest to the English Channel, where they could cut off elite French and British soldiers stuck in Belgium and effectively take all of France.

Soissons stood in that northwestern trajectory. Robert and his six siblings rushed outside, where the scream of a Stuka dive was even more horrifying. Bombs fell on Soissons’ factories (#litres_trial_promo) and the children ran to the family sedan, their mother, Consuelo, ushering them into the car. Consuelo told her eldest, Henri (#litres_trial_promo), then seventeen, one year older than Robert, to go to the castle at Châteaneuf-sur-Cher, the home of Consuelo’s mother, the Duchess of Maillé (#litres_trial_promo), some 230 miles south. Consuelo would stay behind (#litres_trial_promo); as the local head of the Red Cross, she had to oversee its response in the Aisne department. She would catch up with them later, she shouted at Henri and Robert. Her stony look told her eldest sons that there was no point in arguing. She was not about to lose her children, who ranged in age from seventeen to four, to the same fiery blitzkrieg that had perhaps already consumed her husband, Olivier, who—at fifty—was serving as a liaison officer (#litres_trial_promo) for the RAF on the Franco-German border.

“Go!” she told Henri.

So the children set out, the bombs falling around them, largely unchecked by Allied planes. Though history would dub these days the Battle for France, France’s fleet was spread throughout its worldwide empire, with only 25 percent stationed in country (#litres_trial_promo) and only one-quarter of that in operational formations. This left Soissons with minimal protection. The ceaseless screaming whine of a Stuka and deep reverberating echo of its bombs drove the La Rochefoucaulds to the roads in something like a mindless panic.

But the roads were almost at a standstill. The Germans bombed the train stations and many of the bridges (#litres_trial_promo) in Soissons and the surrounding towns. The occasional Stuka strafed the flow of humanity, and the younger children in the La Rochefoucaulds’ car screamed with each report (#litres_trial_promo), but the gunfire always landed behind them.

As they inched out of the Nazis’ northwestern trajectory that afternoon, more and more Frenchmen joined the procession. Already cars were breaking down around them. Some families led horses or donkeys that carried whatever possessions they could gather and load. It was a surreal scene for Robert and the other La Rochefoucauld children, pressing their faces against the windows, a movement unlike any modern France had witnessed. The French reconnaissance pilot Antoine de Saint-Exupéry saw the exodus from the sky, and as he would later write in his book, Flight to Arras, “German bombers bearing down upon the villages squeezed out a whole people and sent it flowing down the highways like a black syrup … I can see from my plane the long swarming highways, that interminable syrup (#litres_trial_promo) flowing endless to the horizon.”

Hours passed, the road stretched ahead, and though the occasional Stuka whined above, the La Rochefoucaulds were not harmed by them—these planes’ main concern was joining the formation heading to the Channel. News was sparse. Local officials had sometimes been the first to flee (#litres_trial_promo). The La Rochefoucauld children saw around them cars with mattresses tied to their roofs as protection from errant bombs. But Robert watched as those mattresses served a more natural purpose when the traffic forced people to camp on that first night, somewhere in the high plains of central France.

Makeshift shelters rose around them just off the road, and though no one heard the echo of bombs, Henri ordered his siblings to stay together as they climbed, stiff-legged, out of the car. Henri was serious and studious (#litres_trial_promo), the firstborn child who was also the favorite. Robert, with high cheekbones and a countenance that rounded itself into a slight pout (#litres_trial_promo), as if his lips were forever holding a cigarette, was the more handsome of the two, passing for something like Cary Grant’s French cousin. But he was also the wild one. He managed to attend a different boarding school nearly every year (#litres_trial_promo). The brothers understood that they were to watch over their younger siblings now as surrogate parents, but it was really Henri who was in charge. Robert, after all, had been the one immature enough to dangle from the parapet (#litres_trial_promo) of the family chateau, fifty feet above the ground, or to once say shit in front of Grandmother La Rochefoucauld (#litres_trial_promo), for the thrill it gave his siblings.

The children gathered together, Henri and Robert, Artus and Pierre Louis, fifteen and thirteen, and their sister Yolaine, twelve (#litres_trial_promo). The youngest ones, Carmen and Aimery, seven and four, naturally weren’t part of their older siblings’ clique. They were not invited to play soccer with their brothers and Yolaine, and only occasionally did they swim with them in the Aisne river, which flowed around the family estate. They were already their own unit, unaware of the idiosyncrasies and dynamics of the older crew: the way Artus favored the company of his younger brother Pierre Louis to Henri and Robert’s, or the way all the boys tended to gang up on Yolaine, the lone girl, until Robert defended her, sometimes with his fists, the bad brother with the good heart.

Years later Robert would not recall how they spent that first night—on blankets that Consuelo had quickly stored into the trunk or with grass as their bedding and the night stars to comfort them. But he would remember walking among the great anxious swarm of humanity, who settled in clusters on a field that, under the moonlight, seemed to stretch to the horizon. Robert was as scared as the travelers around him. But, in the jokes the refugees told or even in their silent resolve, he felt a sense of fraternity (#litres_trial_promo) spreading, tangible and real. He had often lived his life at a remove from this kind of experience: He was landed gentry, his lineage running through one thousand years of French history (#litres_trial_promo). When Robert and his family vacationed at exclusive resorts in Nice or Saint Tropez, they avoided mass transit, traveling aboard Grandmother La Rochefoucauld’s private rail car (#litres_trial_promo)—with four sleeper cabs, a lounge and dining room. But the night air and communion of his countrymen stirred something in Robert, something similar to what his father, Olivier, had experienced twenty years earlier in the trenches of the Great War. There, among soldiers of all classes, Olivier had dropped his vestigial ties to monarchy and become, he said, a committed Republican (#litres_trial_promo). Tonight, looking out at the campfires and the families who laid down wherever they could, with whatever they had, Robert felt the urge to honor La France, and to defend it, even if the military couldn’t (#litres_trial_promo).

The children were on the road for four days (#litres_trial_promo). As many as eight million people (#litres_trial_promo) fled their homes during the Battle for France, or one-fifth of the country’s population. The highways became so congested during this exodus that bicycles were the best mode (#litres_trial_promo) of travel, as if the streets of Bombay had moved to the French countryside. Abandoning their car and walking would have been quicker for the La Rochefoucaulds, but Henri would have none of it. Thousands of parents lost track (#litres_trial_promo) of their children during the movement south, and newspapers would fill their pages for months afterward with advertisements from families in search of the missing. The La Rochefoucaulds stayed in the car, always together, nudging ahead, taking hours just to cross the Loire River (#litres_trial_promo) on the outskirts of southern France, on one of the few bridges the Germans hadn’t bombed.

The skies were clear of Stukas now, yet the roads remained as crowded as ever. This was a full-on panic, Robert thought, and though he wasn’t the best of students he understood its cause. It wasn’t just the invasion people saw that forced them out of their homes. It was the invasion they’d replayed for twenty years, the invasion they’d remembered.

World War I had killed 1.7 million Frenchmen (#litres_trial_promo), or 18 percent of those who fought, a higher proportion than any other developed country. Many battles were waged in France, and the fighting was so horrific, its damage so ubiquitous, it was as if the war had never ended. The La Rochefoucaulds’ own estate, Villeneuve, had been a battle site, captured and recaptured seventeen times (#litres_trial_promo), the French defending the chateau, the Germans across the Aisne river, firing. The fighting left Villeneuve in rubble, and the neighboring town of Soissons didn’t fare much better: 80 percent of it was destroyed. Even after the La Rochefoucaulds rebuilt, the foundation of the estate showed the classic pockmarks of heavy shells. The soil of Villeneuve’s thirty-five acres smoldered for seven years (#litres_trial_promo) from all the mortar rounds. Steam rose from the earth, too hot to till. Well into the 1930s, Robert would watch as a plow stopped and a farmhand dug out a buried artillery round or hand grenade (#litres_trial_promo).

The 1,600-year-old cathedral in Soissons, where the La Rochefoucaulds occasionally went for Mass, carried the indentations (#litres_trial_promo) of bullet and artillery fire, clustering here and boring into the edifice there, from its stone foundation to its mighty Gothic peaks. Storefronts all around them wore similar marks, while veterans like Robert’s father hobbled home after service. For Olivier, an ankle wound incurred in 1915 (#litres_trial_promo) limited his ability to walk unassisted. His injury intruded into his pastimes: When he hunted game, he brought his wife, and Consuelo carried the gun (#litres_trial_promo) until Olivier spotted the prey, which allowed him to momentarily ditch his cane and hoist the rifle to his shoulder. Olivier was lucky. Other veterans were so disfigured, they didn’t appear in public (#litres_trial_promo).

“Throughout my childhood (#litres_trial_promo), I heard people talk mostly about the Great War: my parents, my grandparents, my uncles,” Robert later said. But even as it remained a constant topic, Olivier seldom discussed its basic facts: his four years at the front, as an officer whose job (#litres_trial_promo) was to watch artillery shells land on German positions and relay back whether the next round should be aimed higher or lower. Nor did Olivier discuss the more intimate details of the fighting, as other veterans did in memoirs: stepping on the “meat” of dead comrades (#litres_trial_promo) in an offensive or the madness the trenches induced. Instead Olivier walked the halls of Villeneuve, in some sort of private and almost unceasing conversation with the ghosts of his past. He was a distant father (#litres_trial_promo), telling his children that they “must not cry—ever,” (#litres_trial_promo) and finding solace in nature’s beauty. He had earned a law degree after the war, but spent Robert’s childhood as Villeneuve’s gentleman farmer. Olivier felt most at ease talking about the dahlias he planted (#litres_trial_promo). Consuelo, who’d lost two brothers to the trenches (#litres_trial_promo), was far more outspoken. She instructed her children that they were never to buy German-made goods and told her daughters they could not learn such an indelicate tongue (#litres_trial_promo). Even her job moored her to the past: As chair of the Aisne chapter of the Red Cross, Consuelo spent most of her time helping families whose lives had been upended by the war (#litres_trial_promo).

The La Rochefoucaulds were not unique: No one in France could look beyond his disfigured memories. The French military was itself so scarred that it did nothing in the face of Hitler’s mounting power. In 1936, the führer’s army reoccupied the Rhineland (the areas around the Rhine River in Belgium), in violation of World War I treaties, without a fight, even though France had one hundred divisions (#litres_trial_promo), and the Third Reich’s crippled army could send only three battalions to the Rhine. As Gen. Alfred Jodl, head of the German armed forces operational staff, later testified: “Considering the situation we were in, the French covering army could have blown us to pieces.” But despite overwhelming numerical strength, the French did nothing, and Germany retook the Rhine. Hitler never feared France again.

German military might grew, and as a new war seemed imminent, the French kept forestalling its reality, traumatized by what they’d already endured. In 1938, the French Parliament voted 537 to 75 (#litres_trial_promo) for the Munich Agreement, which gave Hitler portions of Czechoslovakia. Meanwhile, the World War I veteran and novelist Jean Giono wrote that war was pointless, and if it broke out again soldiers should desert. “There is no glory in being French,” (#litres_trial_promo) Giono wrote. “There is only one glory: To be alive.” Léon Emery, a primary school teacher, wrote a newspaper column that may as well have been a refrain for people in the late 1930s: “Rather servitude than war.” (#litres_trial_promo)

This frightened pacifism reigned even after the new war began. In the fall of 1939, after Britain and France declared war on Germany, William Shirer, an American journalist, took a train along a hundred-mile stretch of the Franco-German border: “The train crew told me not a shot had been fired on this front … The troops … went about their business [building fortifications] in full sight and range of each other … The Germans were hauling up guns and supplies on the railroad line, but the French did not disturb them. Queer kind of war (#litres_trial_promo).”

So at last, in May 1940, when the German planes screamed overhead, many Frenchmen saw not just a new style of warfare but the nightmares of the last twenty years superimposed on the wings of those Stukas. That’s why it took four days for the La Rochefoucauld children to reach their grandmother’s house: Memory heightened the terror of Hitler’s blitzkrieg. “We were lucky (#litres_trial_promo) we weren’t on the road longer,” Robert’s younger sister Yolaine later said.

Grandmother Maillé’s estate sat high above Châteauneuf-sur-Cher, a three-winged castle (#litres_trial_promo) whose sprawling acreage served as the town’s eponymous centerpiece. It was a stunning, almost absurdly grand home, spread across six floors and sixty rooms, featuring some thirty bedrooms, three salons, and an art gallery. The La Rochefoucauld children, accustomed to the liveried lifestyle, never tired of coming here (#litres_trial_promo). But on this spring day, the bliss of the reunion gave way rather quickly to a hollowed-out exhaustion (#litres_trial_promo). The anxious travel had depleted the children—and the grandmother who’d awaited them. Making matters worse, the radio kept reporting German gains, alarming everyone anew.

That very night (#litres_trial_promo), the Second Panzer Division reached Abbeville, at the mouth of the Somme river and the English Channel. The Allies’ best soldiers, still in Belgium, were trapped. A note of panic rose in the broadcasters’ voices. The Nazis now had a stronghold within the country—never in the four years of the Great War had the Germans gained such a position. And now they had done it in just ten days.

Consuelo rejoined the family a few nights later (#litres_trial_promo). She told her children how she had barely escaped death. Her car, provided by the Red Cross, was bombed by the Germans. She was not in it at the time, she said, but it quickened her departure. She got another car from a local politician and stuffed family heirlooms into it, certain that the German bombardment would continue and the Villeneuve estate would be destroyed again. Her Red Cross office was already in shambles. “This is it. No more windows, almost no more doors (#litres_trial_promo),” Consuelo had written in her diary on May 18, from her desk at the local headquarters. “Two bombings during the day. The rail station is barely functional. We have to close [this diary] … until times get better.”

But after reuniting with her children, times did not get better. The radio blared constantly in the chateau, and the reports were grim. On June 3, three hundred German aircraft bombed the Citroën and Renault factories on the southwestern border of Paris, killing 254, 195 of them civilians (#litres_trial_promo). Parisians left the city in such droves that cows wandered some of its richest streets, mooing (#litres_trial_promo). Trains on the packed railway platforms departed without destination (#litres_trial_promo); they just left. The government evacuated on June 10 to the south of France, where everyone else had already headed, and the city was declared open—the French military would not defend it. The Nazis marched in at noon on June 14.

Robert and his family bunched round the radio in their grandmother’s salon that day (#litres_trial_promo), their faces ashen. The reporters said that roughly two million people had fled and the city was silent (#litres_trial_promo). Then came the news flashes: the Nazis cutting through the west end and down the Champs-Elysées; a quiet procession of tanks, armored cars, and motorized infantry; only a few Frenchmen watching them from the boulevards or storefronts that had not been boarded up; and suddenly, high above the Eiffel Tower, a swastika flag whipping in the breeze.

And still, no one had heard from Olivier, who had been stationed somewhere on the Franco-German border. Consuelo, a brash and strong woman who rolled her own cigarettes from corn husks (#litres_trial_promo), appeared anxious now before her children (#litres_trial_promo), a frailty they rarely saw, as she openly fretted about her country and husband. The news turned still worse. Marshal Philippe Pétain, who had assumed control of France’s government, took to the radio June 17. “It is with a heavy heart (#litres_trial_promo) that I tell you today that we must try to cease hostilities,” he said.

Robert drew back when he heard the words (#litres_trial_promo). Was Pétain, a nearly mythical figure, the hero of the Great War’s Battle of Verdun, asking for an armistice? Was the man who’d once beaten the Germans now surrendering to them?

The war itself never reached Grandmother Maillé’s chateau, roughly 170 miles south of Paris, but in the days ahead the family heard fewer grim reports from the front, which was unsettling in its own way. It meant soldiers were following Pétain’s orders. June 22 formalized the surrender: The governments of both countries agreed to sign an armistice. On that day, the La Rochefoucaulds gathered round the radio once again, unsure how their lives would change.

Hitler wanted this armistice signed on the same spot as the last (#litres_trial_promo)—in a railway car in the forest of Compiègne. It seemed the Great War had not ended for him either. At 3:15 on an otherwise beautiful summer afternoon, Hitler arrived in his Mercedes, accompanied by his top generals, and walked to an opening in the forest. There, he stepped on a great granite block, about three feet above the ground with engraving in French that read: HERE ON THE ELEVENTH OF NOVEMBER 1918 SUCCUMBED THE CRIMINAL PRIDE OF THE GERMAN EMPIRE—VANQUISHED BY THE FREE PEOPLES WHICH IT TRIED TO ENSLAVE.

William Shirer stood some fifty yards from the führer. “I look for the expression in Hitler (#litres_trial_promo)’s face,” Shirer later wrote. “It is afire with scorn, anger, hate, revenge, triumph. He steps off the monument and contrives to make even this gesture a masterpiece of contempt … He swiftly snaps his hands on his hips, arches his shoulders, plants his feet wide part. It is a magnificent gesture … of burning contempt for this place now and all that it has stood for in the twenty-two years since it witnessed the humbling of the German Empire.”

Then the French delegation arrived, the officers led by Gen. Charles Huntziger, commander of the Second Army at Sedan. The onlookers could see that signing the armistice on this site humiliated the Frenchmen (#litres_trial_promo).

Hitler left as soon as Gen. Wilhelm Keitel, his senior military advisor, read the preamble. The terms of the armistice were numerous and harsh (#litres_trial_promo). They called for the French navy to be demobilized and disarmed and the ships returned to port, to ensure that renegade French boats did not align themselves with the British fleet; the army and nascent air force were to be disposed of; guns and weapons of any kind would be surrendered to the Germans; the Nazis would oversee the country but the French would be allowed to govern it in the southern zone, the unoccupied and so-called Free Zone, in which France’s fledgling provisional government resided; Paris and all of northern France would fall under the occupied, or Unfree Zone, where travel would be limited and life, due to rations and other restrictions, would be much harder.

Breaking the country in two and allowing the French to govern half of it would later be viewed as one of Hitler’s brilliant political moves (#litres_trial_promo). To give the French sovereignty in the south would keep political and military leaders from fleeing the country and establishing a central government in the French colonies of Africa, countries that Hitler had not yet defeated and where the French could continue to fight German forces.

But that afternoon on the radio, the La Rochefoucaulds heard only about the severing of a country their forebears had helped build. Worse still, all of Paris and the Villeneuve estate to the north of it fell within the Germans’ occupied zone. The family would be prisoners in their own home. Listening to the terms broadcast over the airwaves, the otherwise proud Consuelo made no attempt to hide her sobbing. “It was the first time I saw my mother cry (#litres_trial_promo) over the fate of our poor France,” Robert later wrote. This led his sisters and some of his brothers to cry. Robert, however, burned with shame. “I was against it, absolutely against it (#litres_trial_promo),” he wrote, the resolve he’d felt under the stars amid other refugees building within him. In his idealistic and proud sixteen-year-old mind, to surrender was traitorous, and for a French marshal like Pétain to do it, a hero who had defeated the Germans at Verdun twenty-four years ago? “Monstrous (#litres_trial_promo),” La Rochefoucauld wrote.

In the days after the armistice, Robert gravitated to another voice on the radio. The man was Charles de Gaulle, the most junior general in France, who had left the country for London on June 17, the day Pétain suggested a cease-fire. However difficult the decision—de Gaulle had fought under Pétain in World War I and even ghostwritten one of his books (#litres_trial_promo)—he had left quickly, departing with only a pair of trousers, four clean shirts, and a family photo in his personal luggage (#litres_trial_promo). Once situated in London, de Gaulle began to appeal to his countrymen on the BBC French radio service. These soon became notorious broadcasts, for their criticisms of French political and military leadership and for de Gaulle’s insistence that the war go on despite the armistice. “I, General de Gaulle … call upon (#litres_trial_promo) the French officers or soldiers who may find themselves on British soil, with or without their weapons, to join me,” de Gaulle said in his first broadcast. “Whatever happens, the flame of French Resistance must not and shall not die.”

De Gaulle called his resistance movement the Free French. It would be based in London but operate throughout France. Robert de La Rochefoucauld listened to de Gaulle (#litres_trial_promo) day after day, and though he had been an aimless student, he began to see how he might define his young life.

He could go to London, and join the Free French.

CHAPTER 2 (#ub73d4e94-6ac9-5940-b968-e053d0fbfebe)

The family drove back to a Soissons they did not recognize. German bombs had leveled some storefronts and German soldiers had pillaged (#litres_trial_promo) others. Out the car window Robert saw half-collapsed homes and the detritus of shattered livelihoods littering the sidewalks and spilling onto the streets. The damage was not total—some houses and shops still stood—but this capriciousness made the wreckage all the more harrowing.

Approaching the Rochefoucaulds’ home, the car turned onto the familiar secluded avenue just outside Soissons; Robert saw the lines of chestnut trees and the small brick-covered path that cut through them. The car slowed and made the left, bouncing along. Groves of oak and basswood crowded the view and the car kept jostling as the path curved to the right, then the left, and back again. At last they saw the clearing (#litres_trial_promo).

The chateau of Villeneuve still rose from the earth, with its neoclassical design, brick façade, and white-stone trim, a stately home that the La Rochefoucauld family had purchased from the daughter of one of Napoléon’s generals (#litres_trial_promo) in 1861. Beams of sunlight still winked from the windows of the northern wing, a welcoming light that bathed the interior, and all the chateau’s forty-seven rooms (#litres_trial_promo), with an incandescent glow. But at the circular driveway at the side of the home, something strange came into view.

German military vehicles (#litres_trial_promo).

A cadre of German soldiers seemed to have made the La Rochefoucauld house their own, judging from the armored cars and trucks (#litres_trial_promo) parked at odd angles. But this wasn’t even the worst news: On closer inspection, the family saw that the chateau’s roof was missing.

My God, Robert thought, trying to absorb it all.

The children clustered together in the driveway, gawking. Then, unsure what else to do, the family made its way to the front door.

When they opened it, Consuelo and her children saw the same stone staircase (#litres_trial_promo) rising from the entryway to the front hall. But passing above them were German officers, who barely acknowledged their arrival. The Nazis had indeed requisitioned Villeneuve, just as they would other homes and municipal buildings, hoping that the houses and schools and offices might serve as command posts for the French Occupation, or as forward bases for Germany’s upcoming battle with Britain. From the Germans’ apathetic looks, the family saw that the chateau was no longer theirs. “There was absolutely nothing (#litres_trial_promo) we could do against it,” Robert later said.

Consuelo told her children (#litres_trial_promo) not to acknowledge the officers, to show them that they were impermanent and therefore unremarkable: Robert would not sketch in any journal who these Germans were, what they looked like, or which one led them. But he and his siblings did record the broad outlines of the arrangement. The Nazis begrudgingly made room for the family. They soon redistributed themselves (#litres_trial_promo) across one half of the house, so the La Rochefoucaulds could have the other. On the first floor, the officers chose the great room, whose floor-to-ceiling windows looked out on the magnificent manicured gardens, and the dining room, which seated twenty (#litres_trial_promo). The family took the salon—where they had once entertained visiting dignitaries and had debated Hitler’s rise to power—and the living room, cozy with chairs, rows of books, and, above the fireplace, the family crest, which depicted a beautiful woman (#litres_trial_promo) with a witch’s tail—which in earlier times instructed La Rochefoucauld to live fully and enjoy all of life’s delights. The second and third floors—the bedrooms and playrooms for the children, and utility rooms for the staff of twelve (#litres_trial_promo)—were divided similarly: Nazis on one side, the family on the other. Robert still had his own room, a grand chamber with fifteen-foot ceilings, a private bathroom, and fireplace. But he couldn’t stand (#litres_trial_promo) the heavy clacking echo of German boots going up and down the second and third floors’ stone staircase. The noise seemed to almost taunt him.

The family and Germans did not eat together. The La Rochefoucaulds set up a new dining room (#litres_trial_promo) in the salon. They shared the grand spiral staircase because they had to, but the family and its staff never spoke to the Germans, and the Germans only spoke (#litres_trial_promo) to Consuelo, once they learned she was the matriarch and local head of the Red Cross.

Consuelo’s relationship with these occupying officers was, to put it mildly, difficult. In little time they settled on a nickname for her: the Terrible Countess (#litres_trial_promo).

It is easy to understand why. First, Consuelo had built this house. When she and Olivier were married after the Great War, a plump girl who was more confident than pretty, she looked at the ruins of what remained of the La Rochefoucauld estate and told her husband she would prefer it if the rebuilt chateau no longer faced east-west, as it had for centuries, but north-south (#litres_trial_promo). That way the windows could take in more sunlight. Olivier obeyed his young wife’s wishes and brick by brick a neoclassical marvel emerged, one that indeed glowed with natural light. Now, twenty years later, the Germans were sullying the chateau, German soldiers who played to type, too, always loud, always shouting Ja!, parking up to seven bulky tanks (#litres_trial_promo) in her yard and then endlessly cleaning them, meeting in her house, meeting in a tent they set up outside her house, their decorum gauche regardless of where they went, the sort of people who literally found it appropriate to write on her walls (#litres_trial_promo).

Then there was the damage to the roof. And though Consuelo learned that a British bomb (#litres_trial_promo), and not a German one, had missed the bridge it aimed for a half mile distant during the fight for France and instead flattened the fourth floor of the chateau, she resented that the Nazis hadn’t offered to close the gaping hole above them, especially as the summer became late fall and the temperature turned cold. The Villeneuve staff (#litres_trial_promo) had to put a tarp over the roof’s remnants, but that did little good. When it rained, water still flowed down (#litres_trial_promo) the stairwell. Winter nights chilled everyone, brutal hours that required multiple layers of clothing. The bomb had set off a fire that momentarily spread on the second floor, which destroyed the central heating system. Now, before the children went to bed, they had to warm a brick over a wood-fired oven (#litres_trial_promo) and then rub the brick over their sheets, which heated their beds just enough so they might fall asleep.

Finally, there was Olivier. The family found out that he had been arrested by German forces (#litres_trial_promo) near Saint-Dié-des-Vosges, a commune in Lorraine in northeastern France, on June 27, five days after the armistice. He was now imprisoned in the sinister-sounding Oflag XVII-A (#litres_trial_promo), a POW camp for French officers in eastern Austria known as “little Siberia (#litres_trial_promo).” He was allowed to write two letters home every month (#litres_trial_promo), which had been censored by guards. What little Consuelo gleaned of her husband’s true experience at the camp infuriated her further.

Given all this, it wasn’t really a surprise to see Consuelo act out against the Germans. On one occasion, a Nazi officer, who was a member of the German cavalry and an aristocrat, wanted to pay his respects to Madame La Rochefoucauld, whose name traveled far in noble circles. When he arrived at Villeneuve, he walked up the steps, took off his gloves, and approached Consuelo, who waited at the entry, all stocky frame and suspicious gaze. He gripped her hand in his and kissed it, but before he could tell her it was a pleasure to stay in this grand home, she slapped him across the face (#litres_trial_promo). The Terrible Countess would not be wooed by any German. For a moment, no one knew how to respond. Then the officers, only half joking, told Consuelo a welcome like that put her at risk of deportation.

Robert was his mother’s son. The fact that the Nazi officers were a few rooms away only increased his talk about how much he hated them, those Boche (#litres_trial_promo). He was brash enough, would say these epithets just loud enough, that even Consuelo had to shush him. But Robert seemed not to care. His olive complexion reddened with indignant righteousness when he listened to Charles de Gaulle’s speeches, and even after the German high command in Paris banned the French from turning on the BBC, Robert did it in secret. He never wanted to miss the general’s daily message (#litres_trial_promo). Oftentimes, to evangelize, he would travel across Soissons to the estate of his cousin, Guy de Pennart (#litres_trial_promo), who was his age and shared, roughly, his temperament. Guy and Robert talked about how they were going to join the British and fight on. “I was convinced (#litres_trial_promo) that we had to continue the war at all costs,” Robert later said.

He was seventeen by the fall of 1940 and had graduated from high school (#litres_trial_promo). He wanted to join de Gaulle but wasn’t sure how. One didn’t “enlist” in the Resistance. Even a well-connected young man like Robert didn’t know the underground routes that could get him to London. So he enrolled at an agricultural college in Paris (#litres_trial_promo), ostensibly to become a gentleman farmer like his father, but, more likely, he went to meet people who might help him reach de Gaulle.

These individuals, though, were not easy to find. There was little reason to be a résistant in 1940. The Germans had disbanded (#litres_trial_promo) the army and all weapons, all the way down to hunting knives, had been handed in or taken by Nazi authorities. The “resistance” amounted to little more than underground newspapers that were often snuffed out (#litres_trial_promo), their editors imprisoned or sentenced to death by German judges presiding in France.

So Robert and a small number of new friends, all of them more boys than men, turned to one another with refrains about how much they despised the Germans (#litres_trial_promo), and despised Vichy, a spa town (#litres_trial_promo) in the south of France where Pétain and his collaborating government resided. The boys talked about how France had lost her honor. “I didn’t have much good sense,” Robert said, “but honor—that’s all (#litres_trial_promo) my friends and I could talk about.”

Its vestiges were all around him. Villeneuve was not just a home but also a monument to the family’s history, replete with portraits and busts (#litres_trial_promo) of significant men. The La Rochefoucauld line dated back to 900 AD (#litres_trial_promo) and the family had shaped France for nearly as long. Robert had learned from his parents about François Alexandre Frédéric de La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, a duke in Louis XVI’s court. He awoke the king during the storming of the Bastille in 1789. King Louis asked La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt if it was a revolt. “No, sire,” he answered. “It is a revolution (#litres_trial_promo).” And indeed it was. Then there was François VI, Duc de La Rochefoucauld, a seventeenth-century duke who published a book of aphoristic maxims, whose style and substance influenced writers as diverse as Bernard Mandeville, Nietzsche, and Voltaire (#litres_trial_promo). Another La Rochefoucauld, a friend of Benjamin Franklin’s, helped found the Society of the Friends of the Blacks (#litres_trial_promo), which abolished slavery some seventy years before it could be done in the United States. Two La Rochefoucauld brothers, both priests, were martyred during the Reign of Terror (#litres_trial_promo) and later beatified by Rome. One La Rochefoucauld was directeur des Beaux Arts (#litres_trial_promo)during the Bourbon Restoration. Others appeared in the pages (#litres_trial_promo) of Proust. Many were lionized within the military—fighting in the Crusades, the Hundred Years’ War, against the Prussians. The city of Paris named a street after the La Rochefoucaulds.

For Robert, the family’s legacy had followed him everywhere throughout his childhood, inescapable: He was baptized (#litres_trial_promo) beneath a stained-glass mural of the brother priests’ martyrdom; taught in school about the aphorisms in François VI’s Maxims; raised by a father who’d received the Legion of Honor (#litres_trial_promo), France’s highest military commendation. Greatness was expected of him, and the expectation shadowed his days. Now, with the Germans living in the chateau, it was as if the portraits that hung on the walls darkened when Robert passed them, judging him and asking what he would do to rid the country of its occupiers and write his own chapter in the family history. To reclaim the France that his family had helped mold—that’s what mattered. “I firmly believed that … honor commanded us to continue the fight (#litres_trial_promo),” he said.

But Robert felt something beyond familial pressure. In his travels around Paris or on frequent stops home—he split his weeks between the city and Villeneuve—he grew genuinely angry at his defeated countrymen. He felt cheated (#litres_trial_promo). His life, his limitless young life, was suddenly defined by terms he did not set and did not approve of.

What galled him (#litres_trial_promo) was that few people seemed to think as he did. He found that a lot of people in Paris and in Soissons were relieved the war was over, even if it meant the country was no longer theirs. The prewar pacifism had gelled into a postwar defeatism. Fractured France was experiencing an “intellectual and moral anesthesia (#litres_trial_promo),” in the words of one prefect. It was bizarre. Robert had the sense that the ubiquitous German soldiers who hopped onto the Métro or sipped coffee in a café were already part of a passé scenery (#litres_trial_promo) for the natives.

Other people got the same sense. In a surprisingly short amount of time, the hatred of the Germans and the grudges held against them “assumed a rather abstract air” (#litres_trial_promo) for the vast majority of French, philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre wrote, because “the occupation was a daily affair.” The Germans were everywhere, after all, asking for directions or eating dinner. And even if Parisians hated them as much as Robert de La Rochefoucauld did, calling them dirty names beneath their breath, Sartre argued that “a kind of shameful, indefinable solidarity [soon] established itself between the Parisians and these troopers who were, in the end, so similar to the French soldiers …

“The concept of enemy,” Sartre continued, “is only entirely firm and clear when the enemy is separated from us by a wall of fire (#litres_trial_promo).”

Even at Villeneuve, Robert witnessed the ease with which the perception of the Germans could be colored in warmer hues. Robert’s younger sister, Yolaine, returned from boarding school for a holiday, and sat in the salon one afternoon listening to a German officer play the piano (#litres_trial_promo) in the next room. He was an excellent pianist. Yolaine dared not smile as she sat there, for fear of what her mother or older brother might say if they walked past, but her serene young face showed how much she enjoyed the German’s performance. “He was playing very, very well (#litres_trial_promo),” she admitted years later.

It was no easy task to hate your neighbor all the time. That was the simple truth of 1940. And the Germans made their embrace all the more inviting because they’d been ordered to treat the French with dignity. Hitler didn’t want another Poland (#litres_trial_promo), a country he had torched whose people he had either killed or more or less enslaved. Such tactics took a lot of bureaucratic upkeep, and Germany still had Britain to defeat. So every Nazi in France was commanded to show a stiff disciplined courteousness (#litres_trial_promo) to the natives. Robert saw this at Villeneuve, where the German officers treated the Terrible Countess with a respect she did not reciprocate. (In fact, that they never deported his mother can be read to a certain extent as an exercise in decorous patience.) One saw this treatment extended to other families as they resettled after the exodus: PUT YOUR TRUST (#litres_trial_promo) IN THE GERMAN SOLDIER, signs read. The Nazis gave French communities (#litres_trial_promo) beef to eat, even if it was sometimes meat that the Germans had looted during the summer. Parisians like Robert saw Nazis offering their seats to elderly madames on the Métro, and on the street watched as these officers tipped their caps to the French police (#litres_trial_promo). In August, one German army report on public opinion in thirteen French departments noted the “exemplary, amiable and helpful (#litres_trial_promo) behavior of the German soldiers …”

Some French, like Robert, remained wary: That same report said German kindness had “aroused little sympathy” (#litres_trial_promo) among certain natives; and young women in Chartres, who had heard terrible stories from the First World War, had taken to smearing their vaginas with Dijon mustard, “to sting the Germans (#litres_trial_promo) when they rape,” one Frenchwoman noted in her diary. But on the whole, the German Occupation went over relatively seamlessly for Christian France. By October 1940, it seemed not at all strange for Marshal Pétain, the eighty-four-year-old president of France’s provisional government and hero of the Great War, to meet with Hitler in Montoire, about eighty miles southwest of Paris. There, the two agreed to formalize their alliance, shaking hands before a waiting press corps while Pétain later announced in a radio broadcast: “It is in the spirit of honor, and to maintain the unity of France … that I enter today upon the path of collaboration (#litres_trial_promo).”

Though Pétain refused to join the side of the Germans in their slog of a fight against the British, he did agree to the Nazis’ administrative and civil aims. The country, in short, would begin to turn Fascist. “The Armistice … is not peace (#litres_trial_promo), and France is held by many obligations with respect to the winner,” Pétain said. To strengthen itself, France must “extinguish” all divergent opinions.

Pétain’s collaboration speech outraged Robert even as it silenced him. He thought it was “the war’s biggest catastrophe (#litres_trial_promo),” but his mother quieted him. With that threat about divergent opinions, “There could be consequences (#litres_trial_promo),” she said. She had lost her husband and wasn’t about to lose a son to a German prison. So Robert traveled back to Paris for school, careful but resolved to live a life in opposition to what he saw around him.

CHAPTER 3 (#ub73d4e94-6ac9-5940-b968-e053d0fbfebe)

He was still a boy, only seventeen, not even of military age, but he understood better than most the darkening afternoon that foretold France’s particularly long night. Robert saw a country that was falling apart.

He saw it first in the newspapers. Many new dailies and weeklies emerged with a collaborationist viewpoint (#litres_trial_promo), sometimes even more extreme than what Pétain promoted. Some Paris editors considered Hitler a man who would unite all of Europe; others likened the Nazis to French Revolutionaries, using war to impose a new ideology on the continent. There were political differences among the collaborators; some were socialists, and others pacifists who saw fascism as a way to keep the peace. One paper began publishing nothing but denunciations of Communists, Freemasons, and Jews. Another editor, Robert Brasillach, of the Fascist Je Suis Partout (I Am Everywhere), praised “Germany’s spirit of eternal youth” while calling the French Republic “a syphilitic strumpet, smelling of cheap perfume and vaginal discharge.” But even august publications with long histories changed with the times: The Nouvelle Revue Française, or NRF (a literary magazine much like The New Yorker), received a new editor in December 1940, Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, an acclaimed novelist and World War I veteran who had become a Fascist. Otto Abetz, the German ambassador, could not believe his good fortune. “There are three great powers in France: Communism, the big banks and the NRF,” he said. The magazine veered hard right.

At the same time, Robert also noticed the Germans begin to bombard the radio and newsreels with propaganda. Hitler was portrayed as the strong man, a more beneficent Napoléon even, with the people he ruled laughing over their improved lives. Robert found it disgusting, in no small part because he had witnessed this warped reality before, in Austria in 1938 at boarding school. He had even met Hitler there.

It was in the Bavarian Alps (#litres_trial_promo), hiking with a priest and some boys from the Marist boarding school he attended outside Salzburg. The priests had introduced their pupils to the German youth organizations Hitler favored and, at the time, Robert loved them, because they promoted hiking at the expense of algebra. He didn’t know much about the German chancellor then, aside from the fact that everyone talked about him, but he knew it was a big deal for the priest to take the boys to Berghof, Hitler’s Alpine retreat, perched high above the market town of Berchtesgaden. When they reached it they saw a gently sloping hill on which sat a massive compound: a main residence as large as a French chateau and, to the right, a smaller guest house. The estate was the first home Hitler called his own and where he spent “the finest hours of my life,” he once said. “It was there that all my great projects were conceived and ripened.”

The students stood lightly panting before it when a convoy of black cars wended down the long driveway and turned out onto the road. The path cut right in front of the boys, and one sedan stopped in front of them. Out stepped Adolf Hitler. The priest, stunned, began explaining that he and his group had just come to look—but Hitler was in a playful mood, not suspicious in the least, and began questioning the boys, many of whom were Austrian, about their backgrounds. When Hitler got to Robert, the priest said that this boy was French. Robert tried to make an impression, and began speaking to Hitler in the German he’d acquired living in Austria. But the phrases emerged with an unmistakable accent, and when Robert finished, Hitler just patted him on the cheek. “Franzose (#litres_trial_promo),” he responded. (“Frenchman.”) And then he moved on.

In a moment, the führer was back in the car and out of view. The encounter was as brief as it was shocking: The boys had seen, had even been touched by, the most famous man in Europe, the shaper of history himself. They looked at each other, and Robert couldn’t help but feel giddy (#litres_trial_promo).

The bliss wouldn’t last, however. Austria was quickly losing whatever independence it had, and when Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg said in a radio address in February that he could make no more concessions to the Nazis, a frenzied, yelling mob of twenty thousand Fascists invaded the city of Graz (#litres_trial_promo), ripped out the loudspeakers that had broadcast Schuschnigg’s address, then pulled down the Austrian flag and replaced it with a swastika banner. A month later Hitler invaded, and within days the Anschluss was complete.

Robert saw a demonstration in Salzburg a few days later, where everyone shouted, “Heil Hitler! Long live Hitler (#litres_trial_promo)!” He felt the threat of violence begin to cloud the interactions of everyday life. The Nazis occupied the buildings next to the Marist school and one day Robert looked in a window and suddenly a man stormed from the building, insulting and threatening him, simply for peering inside (#litres_trial_promo). Robert began to second-guess a führer who would champion these bullies. By the end of the school year, he was happy to leave Austria for good.

Now, at the beginning of the Occupation, he saw a similar malice embedded within the French newsreels: Everyone smiling too hard and striving to look the same. With each passing day, the Frenchmen he encountered seemed to follow in the Austrians’ footsteps, embracing a fascism they were either too scared or ignorant of to oppose. One exhibition defaming Freemasonry (#litres_trial_promo) attracted 900,000 Parisians, nearly half the city’s population. Another, called “European France,” with Hitler as the pan-national leader, drew 635,000 (#litres_trial_promo). Meanwhile, the German Institute’s language courses flourished to the point (#litres_trial_promo) that they had to turn away applicants. For 90 percent of France, La Rochefoucauld later mused, Pétain and Hitler’s alliance represented the second coming of Joan of Arc (#litres_trial_promo). The historical record would show that collaborators, those who subscribed to newspapers committed to the cause and joined special interest groups, were never actually a majority (#litres_trial_promo), but Robert could be forgiven for thinking this because all around him people declared themselves friends of Hitler. The founder of the cosmetics firm L’Oréal (#litres_trial_promo) turned out to be a collaborator. So was the director of Paris’ Opéra-Comique, the curator of the Rodin Museum, even the rector of the Catholic University of Paris. By the end of 1940, in fact, the country’s assembly of cardinals and archbishops demanded in a letter that laity give a “complete and sincere loyalty … to the established order.” One Catholic priest finished Sunday Mass with a loud “Heil Hitler (#litres_trial_promo).”

It was all so disorienting. Robert felt like he no longer recognized La France. He was eighteen and impetuous and London and de Gaulle called to him—but couldn’t he do something here, now? He wanted to show the Germans that they could control his country, his faith, his house, but they could not control him.

One day he met in secret (#litres_trial_promo) with his cousin, Guy, and they launched a plan to steal a train loaded with ammunition that stopped in Soissons. Maybe they would blow it up, maybe they would just abscond with it. The point was: The Germans would know they didn’t rule everything. Guy and Robert talked about how wonderful it would be, and ultimately Robert approached a man of their fathers’ generation, whom Robert blindly suspected of being in the fledgling Resistance, and asked for help.

The man stared hard (#litres_trial_promo) at Robert. He told him that he and his cousin could not carry out their mission. Even if they stole this train, what would they do with it? And how would it defeat the Germans? And did they realize that their act risked more lives than their own? German reprisals for “terrorism” sometimes demanded dozens of executions.

Already, an amateur rebellion had cost the community lives. A Resistance group in Soissons (#litres_trial_promo) called La Vérité Française had affiliated itself with one in Paris that formed in the Musée de l’Homme. It was a brave but naive group, unaware of the double agents within its ranks as it published underground newspapers and organized escape routes for French prisoners of war. The German secret police raided the Musée and Vérité groups. One museum résistant was deported, three sentenced to prison and seven to death (#litres_trial_promo). In Soissons, two members of Vérité Française were beheaded, six shot, and six more died in concentration camps (#litres_trial_promo). The Nazi agents who organized the Soissons raid (#litres_trial_promo) worked in an elegant gray-stone building—across the street from the cathedral where the La Rochefoucaulds occasionally attended Mass.

So their plan was foolish (#litres_trial_promo), the man said, and Robert and his cousin were lucky to be stopped before the brutal secret police or, for that matter, the army officers billeting in Robert’s house could get to them.

The scolding shamed La Rochefoucauld, and stilled his intent. But the situation in France continued to worsen. The French government was responsible for the upkeep of the German army in France, which cost a stunning 400 million francs a day (#litres_trial_promo), after the Nazis rigged the math and overvalued the German mark by 60 percent. Soon, it was enough money to actually buy (#litres_trial_promo) France from the French, one German economist noted. Oil grew scarce (#litres_trial_promo). Robert began biking everywhere (#litres_trial_promo). The German-backed government in Vichy imposed rations (#litres_trial_promo), and Robert soon saw long lines of people at seemingly every bakery and grocery store (#litres_trial_promo) he passed. The Germans set a shifting curfew (#litres_trial_promo) for Paris, as early as 9 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo) or as late as midnight, depending on the Nazis’ whims. This would have annoyed any college-aged man, but the German capriciousness carried a sinister edge, too: After dark, Parisians heard the echo of the patrolling secret police’s boots (#litres_trial_promo) and might wake the next day to find a neighbor or acquaintance missing and everyone too frightened to ask questions. In 1941, the terror spilled out into the open. Small cliques of Communist résistants in Nantes and Bordeaux assassinated two high-ranking Nazi officers (#litres_trial_promo), and, in response, Hitler ordered the execution of ninety-eight people, some of them teenagers, who had at most nominal ties to Communism. One by one they were sent to the firing squad, some of them singing the French national anthem. As news of the executions spread—ninety-eight people dead—a police report noted: “The German authorities have sown consternation everywhere (#litres_trial_promo).”

The urge to fight rose again in Robert and his college friends. Pétain seemed to be speaking directly to young men like Robert when he warned in a broadcast: “Frenchmen … I appeal to you in a broken voice: Do not allow any more harm to be done (#litres_trial_promo) to France.” But that proved difficult as 1941 became 1942, and the Occupation entered its third year. Travel to certain areas was allowed only by permit, thirteen thousand Jews (#litres_trial_promo) were rounded up in Paris and sent to Auschwitz, and the United States entered the war. The Germans, to feed their fighting machine, gave the French even less to eat, forcing mothers to wait all morning for butter and urban families to beg their rural cousins for overripened vegetables (#litres_trial_promo). Robert now heard of sabotages of German equipment and materiel carried out by people very much like himself. He no doubt heard of the people who feared the growing Resistance as well, who wanted to keep the peace whatever the cost, who called résistants “bandits” or even “terrorists (#litres_trial_promo),” adopting the language of the occupier. In 1942, denunciations were common. Radio Paris had a show, Répétez-le (#litres_trial_promo) (Repeat It), in which listeners named their neighbors, business associates, or sometimes family members as enemies of the state. The Sicherheitsdienst (SD), the feared agency colloquially known as the Gestapo, read at least three million denunciatory letters (#litres_trial_promo) during the war, many of them signed by Frenchmen.

This self-policing—which can be read as an attempt to curry favor with the Germans or to divert attention from oneself or simply to spite a disliked neighbor—oppressed the populace more than the SD could have. As the historian Henry Charles Lea said of the culture of denunciation: “No more ingenious device (#litres_trial_promo) has been invented to subjugate a whole population, to paralyze its intellect and to reduce it to blind obedience.” Even children understood the terror behind the collective censorship. As Robert de La Rochefoucauld’s younger sister, Yolaine, who was thirteen years old in 1942, put it: “I remember silence, silence, silence (#litres_trial_promo).”

Robert, though, couldn’t live like that. “Every time I met with friends (#litres_trial_promo),” Robert would later say, “we always endlessly talked about how to kick the Germans out, how to resolve the situation, how to fight.” By the summer of that year, Robert was about to turn nineteen. The German officers had moved on, as quickly as they’d come, leaving the chateau without explanation for another destination (#litres_trial_promo). This only emboldened La Rochefoucauld, who still listened to Charles de Gaulle and cheered when he said things like, “It is completely normal and completely justified that Germans should be killed (#litres_trial_promo) by French men and French women. If the Germans did not wish to be killed by our hands, they should have stayed home and not waged war on us.”

One day a Soissons postman (#litres_trial_promo) knocked on the door of the chateau and asked to see Robert’s mother, Consuelo. The conversation they had greatly upset her. When he left, she immediately sought out Robert.

She told him that she’d just met with a mail carrier who set aside letters addressed to the secret police. This postman took the letters home with him and steamed open the envelopes to see who in the correspondence was being denounced. If the carrier didn’t know the accused, he burned the letter. But if he did, well, and here Consuelo produced a piece of paper with writing scrawled across it. If the postman did know the accused, Consuelo said, he warned the family. She passed the letter to her son. It had been sent anonymously, but in it the writer denounced Robert as being a supporter of de Gaulle’s, against collaboration, and above all a terrorist.

Anger and fear shot through him. Who might have done this? Why? But to fixate on that obscured the larger point: Robert was no longer safe in Soissons. If someone out there had been angry enough to see him arrested, might not a second person also feel this way? Might not another letter appear and, in the hands of a less courageous postal worker, be sent right along to the Nazis? Robert and his mother discussed it at length, but both knew instinctively.

He had to leave.

CHAPTER 4 (#ub73d4e94-6ac9-5940-b968-e053d0fbfebe)

He went first to Paris (#litres_trial_promo), in search of someone who could at long last get him to de Gaulle and his Free French forces. After asking around, Robert met with a man who worked in the Resistance, and Robert told him about his hope to head to London, join de Gaulle, and fight the Nazis. Could the Parisian help?

The man paused for a moment. “Come back in fifteen days (#litres_trial_promo),” he said, “and I’ll tell you what I can do.”

Two weeks later, Robert and the résistant met again. The Germans patrolled the coast between France and England, so a Frenchman’s best bet to reach the UK was to head south, to Spain (#litres_trial_promo), which had stayed out of the war and was a neutral country. If La Rochefoucauld could get there and then to the British embassy in, say, Madrid, he might find a way to London.

Robert was grateful, even joyous, but he had a question. Before he could cross into another country, he’d have to cross France’s demarcation line, separating the occupied from unoccupied zones. How was he to do that under his own name? The Parisian said he could help arrange a travel permit and false papers for La Rochefoucauld. But this in turn only raised more questions (#litres_trial_promo). If lots of Frenchmen got to London by way of Spain—if that passage was a résistant’s best bet—wouldn’t the Germans know that, too?

Probably, the man said. Everything in war is a risk. But the Parisian had a friend in Vichy with a government posting who secretly worked for the Resistance (#litres_trial_promo). If the Parisian placed a call, the Vichy friend could help guide Robert to a lesser-known southern route. Robert asked the man to phone his friend.

The Parisian and Robert also discussed false IDs. Maybe Robert needed two aliases (#litres_trial_promo). With two names it would be even harder to trace him as he traveled south. Of course, if the Germans found out about either, Robert would almost certainly be imprisoned. La Rochefoucauld seemed to accept this risk because French military files show him settling on two names: Robert Jean Renaud and René Lallier. The first was a take on his given name: Robert Jean-Marie. The second he just thought up, “a nom de guerre I’d found who knows where (#litres_trial_promo),” he later wrote. Both had the mnemonic advantage of carrying some of his real name’s initials.