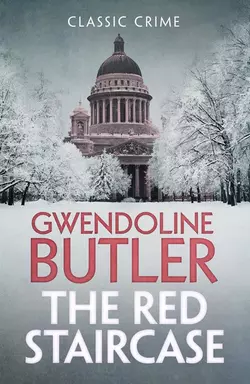

The Red Staircase

The Red Staircase

Gwendoline Butler

Set in St. Petersburg, Russia, this novel won the Romantic Novel of the Year Award (1981) by the Romantic Novelists' Association.St Petersburg, 1912. Rose Gowrie is a Scottish girl with a mysterious gift for healing who is hired into the aristocratic household of Dolly Denisov, supposedly as a companion for the youthful Ariadne Denisov. But Rose gets more than she bargains for when she is called upon to cure the aged Princess who lives at the top of the Red Staircase, and the frail young Tsarevitch…

GWENDOLINE BUTLER

The Red Staircase

Contents

Cover (#ua0a46960-c843-56aa-bf4d-212dfbcd96b6)

Title Page (#ua25f42af-2bd2-557c-86a0-10d69591b51d)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_d71c749e-24a7-5aea-a41a-adc860dd0672)

Chapter 2 (#ulink_89f56840-3c3e-5aa8-8527-a39c2dbbef84)

Chapter 3 (#ulink_d0936315-4b5e-5411-9423-024720b97197)

Chapter 4 (#ulink_9753dc06-9240-5d7d-b03a-4d9bb03417ed)

Chapter 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_19eb8ace-5b18-55bb-9fe9-8e815fa1e87b)

‘Rose?’

As I look back to that time, two statues seem to stand out in my life as marking the twin poles between which my life was to swing. One was the statue of the Prince Imperial which faced the barrack square at Woolwich, and the other was the bronze equestrian statue of Peter the Great in St Petersburg. The house I was to have lived in with my young husband looked over the trees to the Prince Imperial. I never lived near the bird-stained figure of the great Romanov, which is probably just as well, for they say the whole area around is haunted ground and I have too many ghosts in my life as it is – prominent among them the girl that I then was, the young, the innocent, the incredibly naïve Rose Gowrie.

‘Rose?’

It was my sister Grizel speaking on that afternoon which somehow marks the beginning for me. Perhaps for the first time I let some of the worries I most certainly felt in my heart appear obvious to Grizel.

I raised my head from my work. That afternoon I had plodded on as usual at my books. Not as usual, Grizel showed irritation.

‘Do stop and come out. I want to go for a walk. Why do you stick at it? You know it’s not going to lead anywhere. A pure waste of time. Besides,’ she went on, ‘I hate to see you breaking your heart over it. You know now that you are never going to be a doctor. The thing’s impossible.’

‘I got so close … Three years at Edinburgh.’ I found I could talk about it almost without pain that afternoon. I could feel that beneath Grizel’s crossness was a warmth reaching out to me. She hadn’t shown a lot of sympathy for my medical ambitions until then. ‘It was close, you know, Grizel. I jolly near did it.’

‘And then the perennial Gowrie lack of money, and you falling in love with Patrick, dished it.’

‘What an elegant way of putting it,’ I said, laying aside my books of anatomy and morbid pathology. ‘Dished it, indeed. Perhaps I abandoned my studies because I had to, because of circumstances beyond my control – or that was how the Dean of Medicine put it when we said goodbye – but I haven’t given up being interested in it. And the army needs educated wives, so Patrick says. If we go to India, and that could happen, then any medical knowledge I have would be very useful in ever so many ways. Clinics and so on for the wives of the private soldiers and the native women, you know.’

‘You might have babies yourself by then.’

‘Yes,’ I said shortly. I hadn’t thought much about this side of my life yet. It was a long way off, I told myself. But I have an idea that underneath, the thought – half alarming, half exciting – was rumbling away. Patrick and I had met at a ball in Edinburgh and fallen in love so quickly. ‘I suppose soldiers always settle things in a hurry,’ I said from out of the depths of my thoughts.

I’m not quite sure what Grizel took this to mean because she gave a giggle and put her arm around me. ‘I won’t enquire into the meaning of that sentence, Rose dear, even if you know yourself. Sometimes one expresses a truth without meaning to. Only I’m not sure if it’s true of Patrick. I think it was you who swept him off his feet all the same, dear Rose, I know it was for me and young Alec you gave up Edinburgh, and that you minded dreadfully. We’re such a tiresomely expensive brother and sister to have.’

I couldn’t let her get away with that, though. There was a bit of truth in it, but I wasn’t going to lay the burden of it on her young shoulders. ‘What nonsense. It wasn’t like that at all. You had to have your turn, it was only fair. If anything, it was Alec’s fault for needing that extra coaching, the lazy young beggar. I meant to go back when the money got easier, but then I fell in love with Patrick. And as far as you’re concerned, I’m sure no one could be more economical. You make nearly all your own clothes and some of mine as well. And now Alec’s godfather is going to pay for him at Eton, so you see neither of you is so expensive.’

‘I suppose the gods gave you Patrick as a reward,’ said Grizel.

‘You could put it like that.’ Patrick was fairly god-like himself, I thought, but I managed to restrain myself from saying so.

‘Well, I hope you’ll like army life, that’s all.’

‘Oh, of course I will. I’ve made up my mind to like it.’ Patrick Graham was an army officer, a gunner, serving with the Royal Artillery at Woolwich. Hardly the smartest of regiments, but one which suited Patrick, who was interested in machines and engines and not in riding horses. The Grahams – mother, grown-up son and young daughter – had moved to the village near Jordansjoy just before Patrick and I met and fell in love. Indeed, it was because his mother lived near the ancient, crumbling ancestral house of the Gowries that our hostess at the ball introduced us. I don’t think that Mrs Graham had reckoned on Jordansjoy giving her a daughter-in-law before her first Christmas in her new home.

There were three of us at home. I was the eldest left, then Grizel and then young Alec. Robin, my elder brother, our pride, had gone to India with his regiment five years before. He was the bravest and the best of us all. And then he died, killed in a small incident in the border war with Afghanistan, a little encounter that no one ever heard of again. He died of injuries that better and prompter doctoring might have cured. I think it was then that the impulse towards medicine was aroused in me. Or did it have a deeper root? Sometimes I have thought that its beginnings go even further back, beyond conscious memory altogether. There are things I don’t admit even to myself.

Jordansjoy has seen many tragedies in its hundreds of years of history, but Robin’s was one of the sharpest. The neighbours were tactful and left us alone, and we drew in on ourselves, perhaps more than we should have done, Grizel and I and Alec and old Tibby. Tibby must have a word all to herself, because there is no one like her and she has grown out of the soil of Scotland and her period in it. I said something like this to her once, and she said I made her sound like some great monument. She has been nurse, housekeeper and governess all rolled into one since our parents died. When Robin was killed she was our great support, unsentimental and forthright, quite devoid of selfpity, and not allowing us to repine either.

‘Forbye you’re young,’ she said stoutly. ‘With all your lives before you.’

It is then that I had taken myself off to Edinburgh to study medicine at the university there. It was in my heart to persevere, but the money would not run to it in the end. So I stopped. But as with all human actions, there were many reasons for my starting in medicine and many for my giving up. I can see that now.

‘I hope you’ll like the army,’ repeated Grizel, as if I hadn’t already said that I intended to. ‘Tibby says that it will trim the rough corners off you.’

‘Always supposing I want them trimmed.’

‘Oh, she never said it was a good thing. She likes those rough corners and so do I. When you are sharp and speak your mind, and when you stick out for your own way, I like you for it and so does she. She just said it would happen, that’s all.’

‘It sounds a painful process,’ I observed. ‘However, I shall be in the way to find out next week when I visit Patrick in Woolwich to see the house he’s chosen for us to live in. I’m staying with his cousin, and from the sound of her she’s enough to trim anyone’s edges.’

‘A regular dragon? Ach, you’ll get the better of her. Trust you for it, Rose. Here, give me your hand. Let me tell your fortune.’

‘You’ve done it once this week,’ I said, reluctantly offering up my right hand. ‘Surely it can’t have changed.’

Palmistry was Grizel’s new toy. In the crowded attics of Jordansjoy, among the dusty furniture and old travelling trunks (we had been searching for a reasonably smart set of bags for me, as a matter of fact), she had found an ancient book on fortune-telling; ‘The Book of Fate, formerly in the possession of Napoleon, Emperor of France,’ it was called. To the study of this book and the telling of our hands according to the rules laid down therein, Grizel was devoting most of her leisure, as well as a lot of time that should have been spent on other things. Or so Tibby said. Tibby called it necromancy and hinted that it was an abomination according to John Knox. I noticed that she listened with the rest of us, though.

‘You never know. We had a thunderstorm on Tuesday. Perhaps that was a portent of change. We hardly ever get thunderstorms here, so it must mean something.’ And she bent her head over my hand, busily tracing out the lines of head, heart and destiny.

‘I see a double tragedy, but great bravery,’ she announced with some triumph. ‘And a great love.’

‘Oh nonsense.’ I tried to pull my hand away, but she hung on.

‘And happiness,’ she said in tones of slight surprise, as well she might seeing what else she had predicted. Earlier she had foreseen disaster by fire for me. ‘And great possessions. Riches, in fact.’

‘I find that hard to believe.’

‘It is a bit of a staggerer,’ she said, dropping my hand. ‘Perhaps I got it wrong. It was rather hard to read. Your line wobbles a bit just there, owing to a blister you gave yourself with all that sewing on your travelling dress. But I seemed to see something extremely solid. Hard as a cannon-ball.’ She appeared to find satisfaction in this oracular judgement, for she closed my fingers over my palm as if this was the end of her forecasting for the day. ‘There, that’s enough. Aren’t you satisfied?’

Of course, she had no psychic gifts, it was all a game, but some games with some players can deliver hard balls.

In Woolwich the weather turned out to be hot and sultry; I was already tired by the long journey and now I felt, in addition, that my clothes were subtly wrong, too thick and clumsy. Thick silks and twills were out and soft chiffons were in, and no one had told me and I was aware of not looking my best. Perhaps Patrick thought so too, for he was bad-tempered and edgy. I bore this with fortitude, thinking that men are kittle cattle and need understanding. I behaved well, I think, and remained pleasant and good-humoured with him and made myself agreeable to my hostess, who was not a dragon at all but a woman of splintery charm and fly-away hair. And, of course, the owner of some of the prettiest and most fluttery chiffons I had ever seen. She told me they came from ‘Lucille’s’.

I minded the more because Patrick always looked right. He was not elegant or richly dressed, he couldn’t afford to be, but he was natural and happy in his clothes. I don’t suppose he ever wore scent in his life, but there was always an aura of freshness about him. Eyes, hair, skin, were shining. And yet, he was so easy with it. There never was a less stiff fellow than my darling Patrick with his soft, deep voice. At my bitterest times I tried to catalogue these physical attributes, and hate them, but I never could. The truth is I loved him by them and for them and through them.

Whether it was the heat or the fact that my clothes were wrong, I did not seem to be enjoying myself as I had expected. Woolwich was a restless place, with troops of soldiers always clattering through the streets. Patrick was preoccupied with his duties, not always free to be with me, although I felt he was doing his best. I was certainly seeing the workaday side of army life. And every so often the air was rent by the dull thud of artillery, as if we were under siege. I couldn’t always stop myself jumping, even though I knew they were only testing the guns.

The main purpose of my visit to Woolwich was to see the house that Patrick had rented for us, and the morning after our arrival he took me to inspect it – one of an elegant terrace built in the middle of the last century when Woolwich first began to expand because of the demands of the army. I looked out through what was going to be our drawing-room window at the statue erected in memory of the dead Prince Imperial, son to Napoleon III.

‘The furniture is ugly and shabby,’ I said. ‘A family called Dobson with six children had it last, did you say? It looks it.’

‘Is it dirty, then?’ said Patrick, looking around him with surprise.

I had concluded already that Mrs Dobson had not been much of a housekeeper, but with six children probably her mind was on other things. ‘So-so,’ I said. ‘It’ll clean.’ With an idle finger I traced my initials on the dusty windowpane. R. G. They may be there still for all I know.

‘We’ll get you a servant. You’ll need a cook, anyway. Can you cook, Rose? I wish I was a richer man, or would ever be. I’d give you all I could.’ He sounded strained.

‘But I’m quite content.’

‘Content? That’s not much of a word to get married on,’ said Patrick.

I swung round and stared at him. He was looking in my face as if there was some secret he knew and he wished to see if I knew it too. Instinctively I felt this, while I only stared dumbly back. There must have been something in my expression for him to read also, for he put his arm round my waist. He put his mouth on my lips and kissed me; I wanted to kiss him back, but just then I could not. I felt him stiffen. ‘Ah, Rose,’ he said sadly.

The twelve o’clock gun went off then at the Woolwich Arsenal and jerked us apart, and his cousin’s voice calling us from below saw to it that the separation was very nearly permanent. ‘I’m waiting, Patrick,’ she fluted up the stairs in that light, high, English voice of hers. ‘We mustn’t keep Miss Gordon waiting.’ Old Miss Gordon, General Gordon’s sister, lived next door and would be an important neighbour with plenty of influence in Army circles.

Silently Patrick and I went downstairs together. Mrs Lucas, his cousin, looked up at us curiously from under her floppy Leghorn straw hat, but she said nothing.

Patrick saw me off at King’s Cross station on my return journey to Scotland the next evening. ‘There’s some business must bring me to Edinburgh soon,’ he announced abruptly. ‘So I’ll be out to Jordansjoy to see you. I’ll give you advance warning if I can.’

‘Before the wedding?’ We were to be married within the month. Everything was supposed to be in train. I was surprised, but delighted, that Patrick had the time.

‘Before the wedding.’

‘I’ll see you then.’

I was going to say more but he kissed my cheek, gave me a wave and strode away, tall and erect, through the crowd. I watched him go. I remember that a phrase from a poem I had read somewhere flashed through my mind: ‘Too dear for my possessing’.

I went back to Scotland, conscious that some sweetness, some freshness in our relationship had spent itself and would never be replaced.

In those days the night journey from London to Scotland was noisy and tiring, but it had the one advantage that the train stopped at the station for Jordansjoy, where I was glad to see Grizel and Alec waiting for me in a governess cart pulled by the pony from the Manse.

I was always happy to see my home again. Jordansjoy was the shell of a once great house. The castle was in ruins, a romantic and beautiful wreck which had inspired Sir Walter Scott to a well known effusion. The grand mansion, erected by an early Gowrie in 1790 and decorated in the finest neoHellenistic taste of the period, had proved impossible to heat or live in, especially as the family fortunes fell away. For the last generation the Gowries had lived in eight or nine rooms in the stable wing, which was in fact a remarkably beautiful quadrangle of stone buildings, our ancestor having demanded a high standard of living for his horses. We, of course, kept none. Behind the shuttered windows of the mansion lay rooms full of mouldering hangings and worm-eaten furniture, anything of any value having been sold long since.

Tibby took a sharp look at me as I came in. Not much missed her eyes, and I have no doubt she read my mood. ‘Come away in and get your breakfast,’ she said. ‘And after you’ve eaten you can take a rest. Grizel, put a hot-water bottle in your sister’s bed.’

‘I’m not cold,’ I protested, although it was true that my native air did seem fresh and eager after sultry London.

‘Oh, it’s a cosy thing, a bottle,’ said Grizel, dancing away. ‘You can take it out when you get in.’

Tibby poured me tea and took a cup herself. ‘You’ll need to go down and see Mrs Graham when you’ve had your rest,’ she said. ‘She’s been sending up messages for you. Anxious to know the news of Patrick, I suppose.’

‘I’ll go down this afternoon,’ I said wearily. ‘Patrick sent her a letter and a book: a life of Lord Salisbury, I think. She reads a lot of memoirs, you know.’

‘Tired of life, poor thing,’ said Tibby briskly. ‘That’s what she must be, to spend her days reading of what’s done.’

I went to see Mrs Graham next day, and we talked about my visit to London and about Patrick, whom she adored. She was a gentle, delicate woman in increasingly frail health, but she was always good to me. Just as I was leaving, a boy arrived with a telegram for her.

She read it without comment, and then handed it to me. ‘From Patrick.’

I took it and read: ‘Arriving Thursday morning. Staying one night. Do not meet the train.’ I looked up and met Alethea Graham’s eyes.

‘He’ll come to you before he comes home. That’s what the telegram means,’ she said.

I nodded, full of a disquiet I could not explain.

Patrick and I had met at a ball at Holyrood House, to which I had been taken by old Lady Macalister, who had been my grandmother’s friend. She introduced me to Patrick and we had the supper dance together, and then the dance after, and by the end of the evening I, at least, was in love.

We had many meetings in the weeks that followed, while Patrick had leave. Little meetings, I called them in my own mind, because we were never alone, being either in his mother’s company or that of other young people. But we seemed to grow closer at each meeting, and although several people took it upon them to remind me what a bad gambler Colonel Graham had been and how there might be something in heredity, I was not daunted. No doubt Patrick’s friends were telling him the worst they knew of my family, and how the Gowries had always been chancy, impecunious folk. ‘Good looks and bare acres,’ was the phrase around here. But Patrick and I seemed to prosper, and when he asked me to marry him on the last day of his leave, I accepted at once. It was romantic, it was right. I never had a moment’s doubt.

The spot where we became engaged was the Orangery at Lady Macalister’s place near Jordansjoy, and the occasion her annual garden party when she ‘worked off, as we used to say, all the hospitality she owed. The air in the Orangery was sweet and warm, outside in the garden a band was playing a waltz from ‘The Balkan Princess.’ It is a mistake, I’m sure, to think that men don’t succumb to the romance of an occasion as easily as women. I am convinced now that Patrick was powerfully affected by the sweetness of our surroundings, following upon the happy sequence of our meetings, and by a sense of what was somehow appropriate and expected.

Perhaps I underrate myself. I remember saying to Patrick then: ‘But I can’t understand how you came even to notice me.’

‘Can’t you?’ A quizzical look.

‘No. Grizel is the beauty.’

‘Well, there I don’t agree with you. But you need not wonder, Rose. Amongst all those people you really stand out.’

‘I do?’

‘Yes, you’re different. Rose, different from most girls.’

‘I suppose it must be a result of my training in Edinburgh,’ I said thoughtfully. ‘My look, I mean.’

‘It was different to start with.’

‘Yes, in our set it was.’ Which was true.

‘Do you regret not finishing?’

I gave him a radiant smile. ‘Not now, my darling Patrick.’

It wasn’t true, though; I did mind, and perhaps Patrick sensed it.

‘Patrick’s arriving the day after tomorrow,’ I said to Tibby and Grizel, when I got back home. ‘His mother had a telegram while I was there. Arriving in the morning and not to meet the train.’

‘And nothing to you?’ said Grizel indignantly.

‘Oh, I knew anyway. He told me in London’.

‘You never said.’

‘I was going to.’ And I saw Tibby’s eyebrows go up. She knew, and I knew, that I usually came out fast with things I wanted to say.

I knew to the minute the time when the London train arrived at the junction, and knew too how long it would take Patrick to get to me if he took the station fly, and I made up my mind to be waiting for him in the garden so we need not meet in the house. I had an irrational fear of being in a confined space while we talked. I suppose Tibby saw what I was up to, but she helped me by agreeing that the more I weeded that path where the hollyhocks grew, the better.

The time of the train’s arrival came and went, but Patrick did not appear; I waited and waited. ‘This will be the best weeded path in Perthshire,’ I thought in desperation. I was on the point of giving up and retreating to the house when I heard him coming. He was whistling softly to himself as he did sometimes when distracted. I recognised the tune: a poem of Robert Burns’ set to music. ‘My love is like a red, red rose’. I doubt if he knew what he was whistling, and in any case he stopped when he came into view. His shoes and the edge of his trousers were covered with dust. We have very dusty lanes here about Jordansjoy when the weather is dry, and I knew by that dust that Patrick must have been walking and walking around them since the train got in.

‘Hello, Rose,’ he said. ‘You here?’

‘I’ve been waiting for you.’

‘Thought you might be. Sorry if I was a long while coming. I’ve been walking about. Thinking.’

I saw Patrick had someting in his hand: a small packet, neatly done in fresh brown paper. I thought it might be a little present for me. Patrick did sometimes give me presents – a good book or a leather notebook for my accounts, that sort of thing – and now was the time for presents if there ever was one, these weeks before our marriage. I couldn’t expect much after we were married. A brooch with a white river pearl from Perth, perhaps, if I had the good luck to bear him a son.

He did not look in a present-giving mood; he was wearing his dark town suit and carrying lavender gloves. The clothes about which Alec had once been heard to mutter: ‘The mute at the funeral.’ There had never been any love lost between Patrick and Alec since Patrick recommended that Alec, that freedom-lover, be sent away to Eton, for ‘only a top flight public school could whip him into shape’.

‘Let’s go into the house, Rose,’ Patrick now said.

‘Oh, no.’ My reply was spontaneous and instinctive. ‘I’d rather stay outside.’ No good news could come to me inside the house, I knew that, and so I wanted to stay in the garden where there was sunshine and warmth and the memory of happiness.

‘Could I have a glass of water then, Rose? I’m parched.’

Reluctantly I conceded. ‘Come into the parlour.’ And I led the way into its cool darkness. ‘Wait there and I’ll get you a drink.’

I went into the kitchen and drew him a glass of water which was fresh and sweet from our own spring at Jordansjoy. Tibby, who was standing at the table preparing a fruit pie – plum, it smelt like – raised her head and gave me a look.

‘A drink for Patrick,’ I explained.

‘Ah, so he’s come then?’

‘Just the while,’ I said in as non-committal a voice as I could manage.

‘Is water all he wants? We’ve a keg of beer in the pantry.’

‘Water he asked for and water it shall be,’ I announced, carrying the glass out in my hand.

‘Would you have liked beer, Patrick?’ I asked.

‘No, water,’ he said, taking the glass and draining it thirstily. ‘I hate country beer.’

‘We get ours from Edinburgh. McCluskie’s Best Brew.’

‘It’s not good, all the same. You never drink it yourself so you don’t know. I’ve never told you so before.’

‘You’re telling me now.’ I took the glass from him. ‘Of course, we’re not really talking about beer,’ I said coldly.

‘Are we not?’

‘No. Come, Patrick. Perhaps I am a year or two younger than you, but let us meet in this as equals. There’s something on your mind. What’s it all about? You must tell me.’

‘Man to man, eh, Rose?’ He smiled. Patrick never had orthodox good looks, but he smiled with his eyes as well as his mouth and I never knew a soul who could resist that smile, it had such luminous comprehension in it.

For a moment the joke gave me hope. Because he could tease me in this way, surely things could not be wholly bad? ‘Why not?’ I returned boldly.

‘But we aren’t man to man, but man to woman, and that’s the whole of it.’ Looking back, I see that Patrick, who was a brave man, never said a braver thing in his life, but then I hated him for it.

Our parlour at Jordansjoy has one long window which we keep filled with sweet geraniums. Patrick stood with his back to it, so that he was in silhouette and I could hardly see his face. He could see mine, though, and I suppose it looked foolishly young and innocent.

‘Come out into the garden,’ I said. ‘I can breathe there.’

But he interrupted me, saying – his voice a tone higher than usual, and abrupt: ‘Look here, Rose, the wedding will have to be put off. Postponed. I’ve to go to India. I’m transferring.’

I stared; perhaps I said something, I don’t remember; it can have been nothing coherent.

‘It can’t go ahead. You can put about what explanation you like. Blame it all on me. It is my fault. God knows it is.’

‘I don’t understand,’ I stammered.

‘I’m transferring to the part of the regiment that’s going off to India. It’s no place for a woman. It’s a bachelor’s job.’

‘I wouldn’t mind India. I’d like it. I would, I promise.’

‘No, it’s no good, it wouldn’t do, not for me nor for you. It would be a wretched business, Rosie. We should be so poor. God knows, it’s bad enough being poor when you’re married anyway, but in India it would be infinitely worse. I couldn’t bear it for you, Rose.’

‘But we love each other.’

‘Ah, Rose, do we? Really, truly, do we?’

‘I love you.’

‘Do you, Rose?’ He was serious and sad. Hesitantly, he said: ‘I wonder sometimes if you know what love is. Oh yes, in a way, Rose; but a deeper, married love?’

‘We love each other. Together, we shall …’ But he broke in. ‘That’s true in a way, Rose, but is it enough?’ He took my hand. ‘That joke you made about Mrs Dobson and her housekeeping – well, it was true although I didn’t admit it, she is a rotten housekeeper and her house was always untidy and her children run wild. But sometimes I saw a look pass between her and her husband, well, a look that I envied. A look such as you and I could never exchange.’

‘But they have been married for years.’

‘Is that all, Rose? Does it come only with years? No, it was not that sort of look. And if it is not there before marriage, I think it does not come afterwards.’

I was utterly at a loss. There were so many things I wanted to say, but I couldn’t find words for them. So I stood there, just looking at him.

‘I blame myself, not you.’ He sounded weary. ‘I’m older than you, more experienced. I have to protect you. Our marriage would be a mistake.’ He handed me the parcel. ‘Here are your letters, and the book you gave me.’

I threw them on the floor in a fury, and for the first time in the interview felt bitter.

‘Please, Rose,’ he said. ‘I have thought about it very carefully. It is in your interest and mine.’

I sat down; my fury ebbing away had left my legs curiously weak. I suppose he thought I was coming round, because he took a deep breath of relief. As soon as I saw this I felt even more savage. ‘And now I suppose you will go away and explain to yourself that it is my fault. Oh, though I don’t know how it can be. I suppose I’ve failed you somehow, Patrick. Or you choose to think so.’

He quailed before the fury and contempt in my eyes, but he stood his ground – I give him that. When he had made up his mind to do a thing, Patrick did it. ‘No, no, the fault is all mine. I’m not good enough for you.’ He looked at me. ‘Forgive me, Rosie?’

He had given me an antique rose-diamond ring, and I suppose he took it with him, for I never saw it again. I remember nothing of the circumstances of its handing over. Nor of him going; but go he did.

Tibby says she came in and saw me standing staring out of the window, and that I turned to her with tearless eyes and said: ‘He’s gone, Tibby. Gone for good.’ Then I went upstairs and went to my bed. I stayed there, watching the light change on the ceiling as the day reached its peak and then faded into night.

After a while, Grizel and Tibby came to look at me. ‘I’m sick,’ I said, in answer to their anxious questions. And it was, in a way, true; I did feel deadly tired, as if life had seeped out of me. I didn’t look at them, turning my head to stare bleakly at the wall. I could hear Tibby trying to make encouraging, cheerful noises, then I heard her saying something about the doctor, but it was Grizel, my sibling and nearest me in age, who got it right.

‘Leave her alone,’ she said. ‘Let her lie there.’ She drew Tibby out, protesting. ‘No,’ said Grizel firmly. ‘Let her be.’ She pulled my door to and closed it with a decided little bang. It was her message to me, a message of support, and interpreting it correctly I felt a comforting warmth creep into my heart.

I stayed there all night, letting darkness melt in through the window and over the walls, and then recede again into silver light. At no time did I sleep.

Grizel came quietly in when the morning was still early and placed a cup of tea on my bed-table. She did not speak, but adjusted the curtains so that the sun should not shine on my face, and went away. I wondered how much she knew of what had passed between me and Patrick. Almost everything, I supposed, by means of that curious feminine osmosis that sometimes existed between us. I drank the tea, which was very hot and over-sweet, so that I knew Tibby had stirred in the sugar lumps – it had always been her idea that a person in trouble needed something sweet. She might have been right, because the dead weight of fatigue which rested on me began to lift a little.

Presently Grizel came back; I didn’t speak but she lay down on the bed beside me and put her cheek against mine. For a while we lay in silence.

‘There’s a time for keeping quiet and saying nothing, and a time for showing love,’ she said. ‘I think the time has come now for showing love.’ She kissed my cheek.

‘Come on then, Rose.’ Grizel swung off the bed to her feet. ‘I’ll help you dress.’ She opened the big door of the closet where I kept my clothes and, not consulting me, she very deliberately selected a pale pink dress I had never yet worn. Without a word she handed it to me. ‘Wear this.’

‘But it …’I began.

She did not let me finish. ‘Yes. The very prettiest dress from your trousseau. Just the day to wear it.’

I took it and let the pretty soft silk slip through my hands. I remembered the day I had chosen the silk, and I remembered the day Grizel and I had made the dress together. ‘Yes, quite right,’ I said. ‘A pity to waste it.’

Downstairs I went with a flourish. ‘The worst thing about being jilted,’ I said to Grizel as we started down, ‘is that it’s – ’and out it came, the phrase long since picked up in my medical student days, assimilated and made ready to use – ‘such a bloody bore.’

Grizel looked at me, hesitated, and then giggled; and so, laughing, we went forward to meet the day.

Somehow or the other, my life had to be put together again. Twice my circumstances had changed radically. The first crisis, when I had to give up my medical studies in Edinburgh, had seemed to have a happy outcome when I met Patrick and planned our life together. Now this too had collapsed. ‘Third time lucky,’ I thought. It was hard not to be bitter, but it wouldn’t do. I must rebuild my fortunes somehow, and I knew it.

The only thing to do was take life as it came for a bit, and to build it around a succession of small events. Fortunately (from my point of view, although I suppose not from the victims’) it was a busy time in the village with an epidemic of measles with which I was able to help. ‘It’s an ill wind,’ I thought as I cycled down the hill in a rainstorm to a cottage where a child had measles with the complication of bronchitis. ‘At least all this is taking my mind off my own troubles. If the child only lives. A bit hard for the poor little wretch to have to die in order to make me feel better.’

But we saved the child, although we had a bad night of it. ‘He’s turned the corner,’ I said to his mother when I left.

‘I think he has, Miss Rose, praise the Lord,’ she answered.

But as I pushed my bicycle up the hill to breakfast, I knew I had turned a corner in my life too.

‘Have some porridge,’ said Tibby, from the stove where she was stirring a big black pot of it.

‘I’ll just wash my hands.’

When I got back Tibby had laid a place at the kitchen table for me and was pouring herself a cup of tea. ‘How’s the lad?’

‘Better. He’ll do now, I think.’ I began to eat my porridge with relish. ‘Where are the others?’

‘Not up yet. It’s still early. But I knew you’d be home betimes for your breakfast. Either the little lad would come through the night or he’d be gone. Either way the dawn would decide it.’

‘Yes, you’re quite right,’ I said thoughtfully. ‘It’s amazing how the turn of day takes people out or brings them back in. It’s like a tide. But I listened to the birds singing this morning and knew it would be all right. His mother knew, too. We both knew.’

‘It’s the same with life; there comes a turn.’

‘So people say.’ I accepted the truism cautiously.

‘It’ll be that way with you soon.’

‘Can’t be too soon, Tibby,’ I said with a sigh. ‘I’ve got to make my way in the world somehow. It won’t wait on me, you know.’

‘I do know,’ said Tibby.

‘So far I don’t seem to have done anything right. I have to ask myself: What’s the matter with me?’ I looked at her, wondering what she would say.

‘The answer to that’s easy: Nothing,’ she said stoutly.

‘I mean, I can’t retire from life before I’m three-and-twenty,’ I said, continuing with my own stream of thought.

‘Oh, you silly girl.’

‘I haven’t told you much of what was said between me and Patrick. Only the blunt, dead end of it. I’m not sure if I remember it all myself now. What we did and said in the heat of the moment.’ I paused. ‘No, but I am wrong, Patrick wasn’t hot, he was cold, with his mind made up. Wretched, yes, even unhappy, but he was determined to do what he did.’

‘It was an awful thing,’ said Tibby solemnly.

‘Yes, awful. I still don’t understand the rights of it. Or why. But I’m not sure if it hasn’t wrecked me, Tibby.’

‘No, child, no.’ And she got a grip on my hand and held it tight.

‘And you know, Tibby, I think it may be partly because of my interest in medicine. “This health business,” Patrick called it once. I think he didn’t like it. Do you think that, Tibby?’

‘People hereabouts are proud of you.’

‘Are they? I’m not so sure.’ It was true I had a local history of helping with the healing of both people and animals. ‘He may have heard about the child at Moriston Grange, and the dog. People do gossip and say the silliest things.’ Such as the fact that humans sometimes recovered unexpectedly well when I gave them help. ‘Patrick may not have liked it.’ If I had the gift of healing, it was a small gift but a dangerous one.

‘Oh, the wretch,’ said Tibby.

‘Now, that’s not up to your usual standard, Tibby. You should encourage me. Tell me that there is a great future somewhere for Rose Gowrie. But where? Where am I to go? For go somewhere I must and will, Tibby, I tell you that.’ I stood up. ‘A nice breakfast, Tibby. But where am I to go?’

She stood up too, and walked over to the sink with that slow heavy tread she took on sometimes. ‘I’ll have a think.’

‘Make it a lively think then, Tibby.’

We left the matter there for the time being, but from that moment we both knew I was only waiting for life to show me the opportunity.

We glossed over the breaking-off of my engagement when it came to Alec; I don’t think he fully understood what had happened. In any case, he was still young enough for the adult world to be inexplicable to him and its motives something he need not bother to try and comprehend. Since he’d never liked Patrick he was quite glad to see him go.

So that when he came home with the tale he’d heard, the impact was all the harder.

In all innocence he came in from play, sat himself down at the tea table and announced, with satisfaction: ‘Well, he’s away then.’

I was pouring the tea, Tibby was cutting bread. ‘Who?’ I asked, not really attending.

‘That Patrick.’ He took a slice of bread and butter and devoured it rapidly. ‘Him.’

‘Don’t talk with your mouth full, Master Alec.’ He was only Master Alec to Tibby when she was cross. ‘Mind your manners, please. And where has he gone?’

‘I must talk with my mouth full if you ask questions,’ said Alec, continuing his eating. ‘I must answer, that is manners. He’s away to India.’ And his hand reached out for another slice. ‘You never told me that.’ He looked at me accusingly.

I was silent.

‘It was none of your business,’ said Tibby.

‘And he’s not off before time, his sister Jeannie says, for there were bills falling around him like snow. We were playing marbles.’

‘And has he left the bills behind him, then?’ said Grizel in an acid tone.

‘Every penny cleared, Jeannie says.’ Alec turned his attention to the scones and honey. ‘Praise be to God.’

‘Money from Heaven, then, I suppose,’ observed Grizel. ‘For I never knew the Grahams had a rich uncle.’

‘Ach, no, he was paid.’ Alec was all man of the world.

There was a moment of complete silence.

‘Paid?’ It was my voice I heard.

‘Yes, to go away,’ continued Alec through his tea.

‘Well, that’s an odd thing,’ observed Tibby in a temperate voice. ‘And how much did they pay him?’

‘Three thousand pounds, Jeannie says,’ went on Alec, quite oblivious of the effect he was having. ‘Or it might have been more, she’s not quite sure. She couldn’t hear very well.’

‘Why not? How was she hearing them?’

‘Through the crack in the door. You do not suppose they were telling her?’ asked Alec with fine scorn. He looked up, and for the first time he seemed to take in the audience he had. ‘What are you all staring at me like that for?’

‘You may be jumping to the wrong conclusion,’ said Tibby, giving me a straight look over Alec’s head. ‘It may not be at all what it seems.’

‘I’m sure of it. Don’t look at me like that, Tibby, I know I’m right; it was worth three thousand to Patrick to break his engagement to me. So now I know my price. Three thousand pounds, give or take a few more pounds that Jeannie could not precisely hear.’

‘But whoever was it that paid him? And why?’ asked Grizel wonderingly.

Events then followed with a naturalness that made acceptance of them inevitable.

I was wretched at Jordansjoy, an object of interest to all the neighbourhood as the girl who had been jilted. Very nearly on the steps of the altar, too. Former generations of Gowries had been the focus for gossip and hints of scandal, and now I had revived the fire with my shame. For it was shame of a sort. Even those who took my part assumed it was my fault that Patrick Graham had been ‘put off, although he had, of course, ‘behaved disgracefully’. I kept my head high, but it was a bad time.

When the letter came from St Petersburg, it seemed to contain an answer to prayer.

About eighty years or so earlier, a Gowrie had gone to St Petersburg as a merchant and banker, had prospered and settled there. His family stayed on, and the next generation, until by now they were as much Russian as Scottish, except in blood – because they always married among the large Anglo-Scottish community in the capital.

The most eminent among them was Erskine Gowrie, a grandson of the original settler. He was my godfather and had given me a handsome piece of Russian silver as a christening present. He had not attended the christening in person; but I had been told that he did come to Scotland on a visit while I was a child and had taken a great liking to me. I had a vague memory of being bounced on the knee of some gentleman with a beard, and of hearing him pronounce that I had my grandfather’s eyes. Erskine Gowrie had a large factory in the industrial suburbs of St Petersburg where I had been told he manufactured chemicals of some sort. We gathered that Erskine Gowrie had grown old, rich and cantankerous, and by means of this triple and difficult combination had succeeded in quarrelling with all his Russian relatives. Not all of them were rich, and one, Emma Gowrie, whom we called our cousin and who kept us in touch with the St Petersburg Gowries by letter, had been Erskine’s secretary for a time before working for a Countess Dolly Denisov. Through Emma, Countess Denisov had heard of me, and now wrote offering me work in St Petersburg with her and her daughter. Young Russian girls of the nobility are never allowed to go anywhere without a companion, it seemed. But there was more to it than that, because Dolly Denisov had heard from Miss Gowrie that I was interested in medicine, and she wanted me to help train the peasant women on her country estate to look after their own health better. Perhaps I should be able to create a small clinic or hospital at Shereshevo.

‘It’s very tempting to me,’ I said, pushing the letter across to Tibby. ‘Mind you, I don’t like the idea of being a companion.’

‘It’s a good offer,’ said Tibby, raising her eyes from the letter. ‘They don’t ask much from you as a companion except English conversation and friendliness, and they pay well.’

‘Of course, the girl may be a horror.’

‘She sounds nice; seventeen, speaks a bit of English already, likes animals. And what a pretty face!’

I picked up the photograph that had come with the letter. ‘Yes, charming little face, isn’t it? I don’t suppose she’s as innocent as she looks. Oh yes, I’ll go, Tibby. I think I’d go anywhere to get away. And I do like the prospect this offers of advancement. I might get to be a medical pioneer yet.’ I felt a kind of dreamy optimism.

‘You’d be rash to turn it down, I’ll say that.’ She pursed up her lips. ‘The letter says that if you take passage on the John Evelyn, leaving the Surrey Docks on May 2nd, you may have the support of a Major Lacey who is travelling out to see his sister. The Denisovs have Russian friends in London, too, that they name.’ She shook her head. ‘They have planned ahead. You are much wanted to go.’

She gave me the letter back; I remember holding it in my hand. By rights it ought to have burnt my fingers off.

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_7d42633b-d13f-5a79-8617-7978cc61653b)

The wind was blowing in my face, a cold wind blowing across the waters of the Baltic to where I stood on the deck of the John Evelyn. It seemed to go right through my clothes. Ahead I could see the docks and quays of St Petersburg. It was May, we were the first ship into the Gulf of Finland since the winter ice had melted. The wind was cold, and my future lay spread before me on the horizon, and suddenly the prospect frightened me. But it was already more than a prospect; it was upon me. Even now the trunks were being piled on deck ready for arrival, and I could see my own box, black leather with my name on it in white: The Honble Rose Gowrie.

Tentatively I looked up at the man standing beside me, Edward Lacey, late of His Majesty’s Scots Guards, and my travelling companion. I had begun by hating his bland sophistication and his cool English voice. I hated all men, anyway – and pour cause, as our dominie used to say. But he proved kind and considerate during the journey, and relations had improved, though I still found him rather opaque. Now he turned to me with that ever courteous smile. ‘Nearly there, Miss Gowrie.’

We had boarded the small cargo ship, the John Evelyn, going out on the evening tide. The captain had bowed as he passed us on the deck. I was a passenger of special quality on the John Evelyn because I had been seen off by no less a person than Prince Michael Melikov. To my surprise he had been waiting at the Surrey Docks when I arrived. I knew who he must be; Edward Lacey – whom I had met for the first time the evening before, at the London hotel where I was booked for a single night – had told me of the Prince’s presence in London, and that he was a long-standing friend of both the Countess Denisov and my cousin Emma Gowrie. He was wearing a deep violet velvet overcoat. I never saw a man wear coloured velvet before, but on him it looked sombre and rich and yet correct.

He had bent his head to me politely and introduced himself in his deep, sweet voice. ‘And so here I am to see you off, Miss Gowrie. I could never excuse myself to that good lady, your cousin, when we next met in St Petersburg, if I did not see you safely aboard.’

Behind his friendly brown eyes was nothing, he had no real feeling for me. I sensed it without knowing why.

‘I’m looking forward to meeting her,’ I said. ‘I never have, you know. I believe she came once to see us at Jordansjoy but it was years ago, when my parents were not long married and I was only a child. She was old then.’ And must be older now by my twenty years. It was 1912. ‘Our Russian cousin, we call her, but she is as Scots as I am in blood, although four generations of Gowries have lived in St Petersburg now.’ I was talking nervously, for there was something about Prince Michael’s empty eyes that alarmed me.

Edward Lacey arrived at that point, in a cab, and after he had greeted me, stood talking to Prince Michael on the dock. How different they looked: the Prince tall and elegant, but with the withdrawn, inward expression of a man used to books and libraries; and Edward Lacey almost as tall but broader of shoulder, with the look of the open air about him, active and energetic. The one as unmistakably Russian as the other was English.

They were both watching me. The notion struck me and would not be dismissed. I felt as if they were studying me. Politely, of course, but with intent. And not for my looks, either. I knew what that sort of look was like; I knew what it was to be admired. At the memory of some special glances I once treasured, my spirits plummetted. I gritted my teeth, and pushed emotion away. I would not be bitter.

The dock side was very busy, many craft were taking advantage of the high tide to load. A string of lighters and barges was passing down river towards the estuary. Its tug gave a melancholy hoot as it went and another ship answered, part of the perpetual conversation of the river. It was evening, a fine night in early summer. Summer smells mingled with the smells of oil and dust in the Surrey Docks, and with the strong odour of horse. A dray horse, who had brought his load of packing-cases to the side of the John Evelyn to be hauled aboard, was pawing the cobbles. There was a young lad sitting on the dray, ostensibly minding the horse, watching the scene, and calling out jokes and ribaldry to the stevedores and dockers labouring around him. He had a tin whistle stuck in his waist and presently he started to play a tune. A gay little rag-tune; I shall never forget it. I think it was called ‘Irene’, a name which was to mean much to me. Strange, that name coming then; what an uncanny trick life has of striking a note that it means to repeat.

At last we went aboard the John Evelyn. The light was fading fast. I was unsurprised to find that over an hour had passed. I remember Prince Michael’s smile as he finally went away, which accentuated rather than took away the emptiness of his eyes. He smiled, not for me or with me, but because of me; I was quite sure of it.

After I had unpacked, I went on deck again to watch the Thamesside slipping past. The ship had sailed almost immediately on our coming aboard. My cabin was small, but I had it to myself. I had arranged my clothes, put out the silver-backed hairbrushes that had belonged to my mother, and around them placed the photographs of Grizel and young Alec, Tibby and my brother Robin. My pantheon, as naughty Alec called them. Four faces where there had once been five; one god had gone from my pantheon. Again, I tried to repress bitterness, but the taste of it remained in my mouth even as I stood on deck and watched the lights of London and her satellite suburbs, Greenwich and Woolwich, disappear into the dark. The water grew rougher as we felt the pull of the open sea.

I had made myself a hooded cloak of thick plaid, and lined the hood with fur from an old tippet handed down in my family for generations and at last consigned to me. ‘Bring warm clothes,’ my old Russian cousin had written. I pushed back the hood and let the soft fur fall across my shoulders in unaccustomed opulence; and I wondered what the future held in store for me. I suppose every girl wonders this, but I had special cause.

Then Edward Lacey came up behind me. I recognised him by the smell of Turkish tobacco and Harris tweed that I had already identified as peculiarly his own. He moved to my side, he took out his pipe.

‘Do you mind if I light up, Miss Gowrie?’

‘Oh, no, please do. I enjoy the smell.’ I had smoked a cigarette myself once, but I did not tell him; he seemed to find me puzzling enough already.

He struck a Swan Vesta, and the tobacco smouldered fragrantly. He took a puff or two, then the pipe went out. Pipes always do. But he did not re-light it. Instead he stood there looking into the murky river, glancing at me from time to time.

I kept silent. I was aware he was studying my face. I suppose I was studying his in return. We had met only briefly the day before, but now, embarked on our voyage, conscious that we should be much in each other’s company over a long period, it was as if we both knew we were about to move into a new kind of intimacy. As a type he was not new to me; I had seen plenty of his sort come up for shooting parties at the big house. Such men were sophisticated, worldly, and hard to know. Not the sort of person I really felt at home with.

‘So,’ he said, as if recapping what he had already established, ‘you are the strong-minded young lady who likes medicine and healing the sick? I must warn you that you have a sceptic in me.’

‘Why, Major Lacey – ’

‘I mean, as far as women’s education is concerned. I just don’t like to see it overdone. Seems all wrong to me.’

‘You seem to know a lot about me,’ I said shortly.

‘Well, I do in a way. A potted biography, Dolly Denisov gave me. She’s got a knack of putting things in a nutshell.’

‘Accurately, I hope.’ I spoke with a certain asperity.

‘Yes, she’s reliable, is Dolly. And then, of course, I know your cousin and old Erskine Gowrie, too. Not that he’s seen much these days. Not the man he was. No, Dolly told me all about you. The medicine and all that. I thought you’d be a tough, dried, hockey-stick of a girl.’

‘And I’m not?’ I enquiried, thinking that, after all, not everything about me had been relayed to this man through the channels of Emma Gowrie and Dolly Denisov. Not Patrick.

‘Not a bit,’ he said cheerfully. ‘But I ought to warn you – you’ve captivated Dolly’s imagination. And that can be dangerous.’ He was half laughing, but half serious. ‘All Dolly’s swans have to be swans, you see. Ask Mademoiselle Laure about that.’

‘And who is Mademoiselle Laure?’

‘Oh, a sort of French governess they keep there,’ he said vaguely. ‘On the retired list. Except I believe she teaches French to Ariadne still.’ There sounded an ambiguous side to Mademoiselle Laure, I thought.

‘Thank you for the warning. I need this post. The pay is good and I am poor, which is a state, Major Lacey, you probably know nothing of. You have certainly never been a poor, unmarried girl with her way to make.’

‘Touché,’ he conceded.

I needed desperately, too, to get away from my home, but no point in telling him that if Dolly Denisov had not. It was my own private wound, for me to bear and heal.

‘But Russia is a dangerous place to come to make your fortune,’ he said soberly.

‘I shall hardly do that, working in the Denisov home.’

‘No, if that’s all that happens. But one rarely does only one thing in Russia, as I know to my cost. It’s the way things happen there. There’s a sort of persuasiveness to the place.’ He shook his head. ‘Don’t bully yourself too much, Miss Gowrie. Sit easy to the world; it’s the best way to take your fences. Goodnight. I’m off below.’ And he strolled away, calm and friendly as before.

With a start, I realised he knew all there was to know about me, and was giving me what he thought of as good advice. Something in his cool assumption that he knew best got under my skin. With sudden tears of fury blinding me, I hammered the iron deckrails till my hands ached. ‘Beastly, arrogant man!’ I cried. ‘Stupid and obtuse like all of them! I hate him. I hate all men.’

I felt better after the explosion of tears, and from then on I started to enjoy the journey. After all, I had done so little travelling that to be on the move was in itself new and exciting. My spirits improved daily, and I even began to enjoy the company of Edward Lacey.

And now I was almost sad that the journey was ending …

I came back to the present, to the view of St Petersburg, and to Edward Lacey’s voice. ‘Peter the Great built St Petersburg because he wanted a door on the world,’ he was saying.

‘Hadn’t he got one, then?’

‘The western world. Moscow was in many ways an oriental capital. He wanted to change all that. He did, too. But I think Russia has been paying the price for it ever since. What a country.’

We had talked a good deal about Russia during the voyage, and he obviously knew it well. His sister, he had told me, was married to a Russian; she was expecting a child in the autumn. Now he said: ‘I shall hope to introduce you to my sister, Miss Gowrie, when she’s out and about again.’

‘Oh, thank you.’ Perhaps he didn’t disapprove of me as much as I had thought. ‘Yes, I should like that. I shall know so few people apart from my godfather and the Denisovs.’

‘That will soon change,’ he predicted briskly. ‘The Russians are an endlessly sociable people. The Denisovs will take you around. Dolly Denisov lives for the world.’

‘Ariadne is only seventeen,’ I said.

‘Never mind, you won’t be cloistered.’ He had his eyes screwed up, staring at the quay. ‘There’s the Denisov motorcar already waiting for you, I see.’

‘A motor-car?’

‘Yes.’ He sounded amused. ‘Did you expect a sledge? It is summer and there are very few motor-cars in St Petersburg, but of course Dolly Denisov has one.’

Suddenly, my new life seemed all too close. ‘I wonder if I shall be happy in Russia,’ I said urgently.

‘Yes. If you are the sort of girl who can accept it for what it is, a country entirely itself, and not be continually comparing it with what you know at home, then you will be happy. Or on the way to happiness.’

‘I think I can manage that.’

‘And learn the language. The real Russia is hidden, otherwise.’

‘I already know a little Russian,’ I said. ‘Our local schoolmaster taught me to read Chekhov, he had the language from his mother who was a governess in Russia.’

‘Then you will be well away. And keep your eyes open to the state of Russia. I expect you know something already?’ He was summing me up.

‘I have read the news,’ I said. ‘I know of the terrible poverty, of the oppressive rule, and of how they fear revolution.’

‘Yes. There are all shades of political thinking in Russia, from the most reactionary which favours extreme despotic rule by the Tsar, to the moderates who want to make the Tsar a parliamentary monarch on the British model, to the extreme anarchists who want to destroy all government – blow the lot up, is their motto. I should say Dolly Denisov is an old-fashioned liberal who wants the Tsar’s government to relax some rules but otherwise keep things more or less as they are. As for her brother, he sometimes looks as if he despaired of his country and did not give a damn. Yet I swear he does, because Russians always do care, and those who seem indifferent often care the most. For all I know he may be an out-and-out reactionary – there is that element in the Denisov family – or a downright anarchist.’

He was patently instructing me in the intricacies of Russian political life and I acknowledged this. ‘I will look and learn,’ I said.

‘Then you may survive. But mind: I only say may. It’s the goddamned country. One loves it or hates it.’

We disembarked together, and moved along the quay towards the Denisov car. My great adventure was upon me. With a beating heart I prepared to meet the Denisovs. The Denisovs and Russia.

No one had told me about the May nights, how white they were, and how intense, and how they would affect me. I kept thinking of Patrick; I had come to Russia to forget him, and he was all I could think about. These long, sleepless nights were one of the phenomena of my first weeks in St Petersburg. There were others. One was the cold. Heaven knows, Scotland is often cold enough in May, but I was not prepared for the cold wind of Russia that made me huddle in my clothes. But they told me it would be warm enough soon, and then I should see. Everyone in the Denisov household seemed to take a delight in offering me the contradictions of St Petersburg, as if it had all been specially constructed to amuse me. It was my first introduction to one aspect of the Russian character: its capacity to charm. At the beginning, and indeed for a long time after, Dolly Denisov seemed to me charm personified. Partly it was her voice, delicate, light and sweet.

‘You speak such excellent English yourself, Madame,’ I told her, not long after I arrived, ‘that I wonder you need me to speak to your daughter.’

‘Ah, but poor Ariadne, she needs your company. She must be gay, happy. I love her to be happy. Besides, I cannot be with her all the time.’ A slight pout here, as of one sacrificed already too much to maternal duty.

But it was plain from the start that Dolly Denisov had other amusements besides motherhood; her appearance, for one thing. Never had I seen such dresses and such a profusion of jewels. Perhaps she saw my smile. ‘Ah, it’s no joke, Miss Gowrie, being a wife at eighteen and a widow with a daughter at twenty.’

‘And such a daughter,’ said Ariadne, giving her mother a loving pat. ‘Seventeen years and more you have had of it, Mamma.’

‘But luckily the English nation has been specially created to provide us poor Russians with the governesses we need,’ laughed Madame Denisov, ‘and thus to lighten my burden.’

English or Scottish, it was all one to her.

A joke, of course, but partly meant. You got a new slant on the Anglo-Saxon people and the great British Empire in Russia; we were not, as I had supposed, a nation of shop keepers and diplomats and colonisers, but a race of trustworthy governesses.

The Denisov motor-car had duly met us off the John Evelyn, and, close to, gave me an immediate appreciation of the Denisovs’ mettle; it was of surpassing elegance, the bodywork of maroon with a sort of basket-work corset enclosing it, the metalwork like well polished silver and the upholstery of lavender-blue watered silk. Did I forget to say that it was perfumed? As the introductions were concluded and I stepped inside, a sweet waft of rose and iris floated towards me, nicely mixed with the smell of Russian cigarette smoke. I discovered afterwards that Dolly Denisov smoked incessantly, a long, diamond-studded cigarette-holder always between her fingers. Not that Madame Denisov was there herself at the quay, of course. She was out at one of her numerous engagements, and indeed I did not see my employer for the first twenty-four hours after my arrival. But Ariadne, my dear pupil, had come to meet me. A plain girl, I thought at first, but when I took in her friendly brown eyes and her gentle smile, I saw she had her own beauty.

She turned from Edward Lacey and held out her hands in welcome. ‘I am so glad to see you, Miss Gowrie. I have been excitedly looking forward to today.’

I mumbled some pleasantry in reply. There was the sort of small, unhappy silence that seems inevitably to characterize such occasions, and then Edward Lacey was shaking my hand. ‘Goodbye for the time being, Miss Gowrie.’

I watched his tall, erect figure disappear amid the dock-side crowd. I have not found him easy to know, but with his going went my last link with home. Here I was, ensconced in a beautiful motor-car, with my charge. I seemed to have absolutely nothing to say. All I could think was: ‘Already Ariadne speaks excellent English. I shall have little to do on that score.’

At once she seemed to sense my thought, demonstrating that quick intelligence I was to know so well. ‘I speak English all the time with Mamma. Naturally.’

‘Naturally?’

‘Here one speaks either French or English, and Mamma says she likes French clothes and English conversation.’ It was a fair introduction to Dolly Denisov and, in its calm, good-humoured presentation of the facts, of Ariadne also.

While I was talking to her, I was trying to take in all that I could see of St Petersburg as we drove. It was a city of bridges and canals; water was everywhere. I could believe the stories of how the city had risen out of the marshes at the command of Peter the Great. It was early afternoon, and the sun sought out and flashed on gilded domes and spires.

‘That is the dome of St Isaac’s Cathedral,’ said my companion helpfully, observing my intent look. She pointed. ‘And that is the spire of the Fortress Cathedral.’

The streets were wide but crowded with people. Many of the men seemed to be in uniform – uniforms in a tremendous range of styles and colours. I supposed that later I would learn to recognise what each meant, and to appreciate the significance of this green uniform, and that red livery, this astrakhan cap and that peaked one, but at first glimpse the variety was simply picturesque and exciting. Our motor-car wove its way in and out of a great welter of traffic, private conveyances, carts, and oddly-shaped open carriages whose iron wheels rattled across the cobbles. At one junction an electric tram clattered across our track, motor and tram so narrowly missing a collision that I caught my breath. But Ariadne remained calm, as if such near misses were an everyday occurrence. At intervals, a majestic figure wearing a shaggy hat of white sheepskin and a long dark jacket would stride through the traffic, oblivious of all danger, forcing all to give way before him: a Turcoman, living reminder of Oriental Russia.

Now we had turned along a waterfront, passing a great honey-coloured building and then a dark green, verdant stretch of gardens. There was what looked like a row of government buildings of severe grey stone, succeeded by a row of shops and some private houses. Then a few more minutes of driving and we had arrived at the Molka Quay. The motor-car stopped outside a house of beautiful, pale grey stone with a curving flight of steps leading to an elegant front door.

As we drove up, the door opened. I suppose someone had been watching. But this was always the way it was in Russia; it never seemed necessary to ring a bell or ask for a service, every want was unobtrusively satisfied before the need for it was even formulated, the servants were so many and so skilful.

I was taken up to my room by a trio of servants and a laughing Ariadne. With a flourish, the girl showed me round what was to be my domain. Domain it was; I had two lofty rooms with an ante-chamber, and my own servant. I almost said ‘serf’, but of course the serfs had been freed in 1861 by Alexander, the Tsar Liberator. Nevertheless, the servant who bowed low before me was old enough to have been born into servility, and I felt you could see it in his face, where the smile was painted on and guarded by watchful eyes.

‘Ivan will stand at your door, and anything you wish, he will do. You have only to say.’

‘I shall have to brush up my Russian.’

‘Ivan understands a little English, that is why he was chosen. On our estate a few peasants are always taught some English. Also French and German. It is so convenient.’ Ariadne held out her hand and said sweetly: ‘Come down when you are ready. We have English tea at five o’clock.’

Somewhat to my surprise, and in spite of his Russian name, Ivan was a negro.

When Ariadne had gone, leaving only Ivan standing by the outer door, I explored my rooms, which were furnished with a mixture of Russian luxury and western comfort. Carpets, tapestries and furniture were expensive and exotic. Great bowls of flowers stood everywhere. The bed in the bedroom was newly imported from Waring and Gillow of London, by the look of it. I unpacked a few things, stood my photographs of the family at Jordansjoy by my bed where I could see them when I went to sleep, and proceeded to tidy myself to go down to the Denisovs’ ‘Five o’clock’. I washed my hands. I found that the rose-scented soap in the china dish was English.

It may very well be that young Russian noblewomen never go anywhere without a companion, but otherwise it seemed to me that Ariadne Denisov had a good deal of freedom. For that first evening she entertained me on her own, presiding over dinner and then playing the piano to me afterwards. It was pleasant and undemanding, but anticipation and a battery of new experiences had exhausted me, and before long Ariadne realized the condition I was in, and the two of us went up to bed.

On our way upstairs I saw a small, dark-gowned figure moving along the corridor a short distance ahead of us. Not a servant, obviously, from the sharp dignity with which she observed: ‘Good night, Ariadne,’ disappearing round the corner without waiting for an answer.

‘Mademoiselle Laure, the French governess,’ explained Ariadne. ‘The French governess,’ I noticed, not ‘my French governess’. Thus Ariadne dismissed Mademoiselle as a piece of furniture of the house, necessary, no doubt, to its proper equipment, but of no importance. Her attitude contrasted strangely with the welcome given to me.

Sitting up in bed, plaiting my hair, I thought about the scene again. No doubt I had imagined the flash of malevolence from Mademoiselle Laure’s eyes. Yet she had spoken in English when French would have been more natural to her. No, emotion was there, and I would do well to heed it. I recalled Edward Lacey’s suggestion that Mademoiselle Laure had experienced a certain captiousness in Madame Denisov’s attitude to her protegées. Was she, perhaps, envious of me?

I considered where I had landed myself. The business of preparing for bed had revealed that the luxury I had first noticed went hand in hand with a curious primitiveness. There were beautiful carpets and fine pictures everywhere, jasper and lapis lazuli had been used to decorate the walls of the salon; but there was absolutely no sign of piped water. No water-closet seemed to exist, and I had an antique-looking commode in my room. Private and convenient, no doubt, but even Jordansjoy did better. And there was dust under the bed.

But all the same, I liked it here. Magnificence suited me, never mind the dirt. The Denisovs were obviously extremely wealthy. I had been told that only the very rich had their own house, or osobniak, and that even the well-to-do chose to live in flats. But the whole of this great house seemed given over to the Denisovs. And so far I had met only one of them. Besides Madame Denisov there was the ‘Uncle Peter’ Ariadne had spoken of, her father’s younger brother. She had pointed out his photograph to me, showing me the face of a neat-boned, dark-haired young man with a look of Ariadne herself, the features which seemed plain on the girl possessing elegance on him.

I snuggled down into bed at last, tired but curiously confident – sure I could outlast any caprices of Dolly’s favour for as long as it suited me.

The next day, somewhat later than I might have expected, I met Dolly Denisov.

She was sitting curled up on one end of a great sofa, a bright silk bandeau round her head, a pink spot of rouge on each cheek and something dark about her eyes, puffing away at a cigarette and chattering at a great rate to Ariadne in her high-pitched, lilting voice. She leapt to her feet when she saw me and came forward holding out a delicate, jewelled hand.

I don’t remember her opening words, I was too absorbed in her physical impact; I was swimming in a strange sea, excited and exhilarated. Then we were sitting down, side by side on the sofa, talking as if she was really interested in me.

‘And did you sleep? Visitors sometimes find our summer nights trying.’

‘I did find it difficult to sleep.’

‘And you dreamed? We always say that there’s nothing like a St Petersburg summer’s night dream.’

‘Yes, I dreamed.’ I had dreamt of Patrick. She knew all about Patrick, of course. I realized by now that everything of my sad little history had been explained to all parties concerned by Emma Gowrie.

‘Everyone dreams here in the summer. When they can sleep at all. I can never sleep. All the time I am exhausted.’ She didn’t look it, though. Energy crackled from her. ‘But then we go to our estate in the country and there I rest; but you will be at work.’ And she smiled. ‘Foreigners are always interested in our country estates because in them is the heart of Russia. We know what we owe to our peasants, Miss Gowrie, you must never doubt that. Between the landed proprietor and his peasants is a bond that only God can break. Outside Russia, people do not understand this. But I am a liberal-thinking woman. I want the Tsar to rule through a Parliament – the Duma, we call it – as your King does.’

Our conversation was broken into by a procession of servants carrying salvers laden with food and wine, which they proceeded to lay out upon a series of small tables before bowing and retiring. I watched, frankly enjoying the scene; it was as good as being at the play. And no sooner had they departed than a stream of guests began arriving, almost all the men in a uniform of one sort or another, the ladies for the most part as richly decked out as Dolly Denisov, with one or two poorer-looking figures dressed in dingy dark clothes – including one elderly lady who speedily helped herself to a plate of assorted delicacies and retired to a corner to eat them as if she had not seen food as good as this for sometime, and would not soon do so again. Last to arrive was a trio of musicians who came quietly in, settled themselves in a corner and struck up. No one took the slightest notice, although by all accounts the Russians rated themselves very highly as music lovers.

Ariadne skipped around, sometimes bringing guests up to me to be introduced, sometimes leading me to them. Madame Soltikov, Count Gouriev, Professor Klin, Prince Tatischev, the Princess Valmiyera – she was named with especial respect, and was the little old lady eating her plateful of delicacies.

Halfway through the evening a tall, dark-haired young man walked quietly across the room to where I was sitting and introduced himself. ‘I am Peter Alexandrov, Dolly’s brother.’ He was fastidiously and beautifully dressed and I caught the faint scent of verbena as he bowed over my hand. No one could have been more unlike Patrick, but he was the first man who had caught my attention at all since my disaster. ‘I should think he knows how to interest women all right,’ I thought to myself as I talked to him.

Our conversation was light and easy, nothing important was said, but I felt I had made a friend. When he rose to go I saw him catch Dolly’s eye and a look passed between them. A question in hers, and an assent in his. I could not mistake it. He had wanted to meet me, I was sure of it.

Someone had been watching us. I turned quickly. A small dark-clad figure crossed the room diagonally, walking towards the door. I recognised Mademoiselle Laure. So she had been here all the time.

An irrational vexation possessed me. We were two of a kind in this household, Mademoiselle and I, and yet she seemed to avoid me, whereas I had already made tentative explorations to see if I could find her room.

‘There goes Mademoiselle Laure.’ I pointed her out to Ariadne. ‘I didn’t know she was here.’

‘Oh, she came to listen to the music, I suppose,’ said Ariadne. ‘She is very fond of music.’

If she had been listening, then she was the only one. The musicians had played sadly, as if they never expected an audience. Now they had packed up their instruments and were filing out, one after the other like the Three Blind Mice.

‘I suppose she has a room somewhere near mine?’ I asked.

‘Mademoiselle Laure? Oh, I think she is in a room on the next floor,’ said Ariadne vaguely, as if she did not know and did not care. It was all very unlike the treatment of me.

The next day Dolly Denisov clapped her hands and announced that Ariadne would be taking me on a tour of the city. Was I rested? Was I comfortable? Good. To be introduced to St Petersburg was a necessary preliminary to my duties.

‘Duties,’ I thought. There seemed to be no duties, only pleasures.

We duly set off in their large motor-car, with Ariadne pointing out the sights. We had passed this way yesterday. ‘There is the Rouminantiev Garden ― so beautiful. One day we must walk there. Oh, all those buildings are part of the university, but that one over there covered with mosaics is the Academy of Arts. Mamma says it is unsightly, but I rather like it. Oh, and that’s the Stock Exchange – looks as if it was hewn out of solid rock, doesn’t it?’ She spoke through the speaking tube to the footman, who then spoke to the chauffeur. ‘Go on to the Peter and Paul Fortress, then the Cathedral, and then down to the Nevsky Prospect.’ She turned to me. ‘That way we’ll go past the Vladimir Palace and the Winter Palace. You’ll like the Nevsky Prospect, the shops are gorgeous.’ And she giggled. She and her mother had the same sort of delightful, rumbling little laugh.

Ariadne had her orders, I decided, and the tour which looked so artless had been carefully thought out. The city was laid out before me in its great beauty, with everywhere trees and water, and buildings either of rich red brick or stone apricot-coloured in the sunlight. The sombre bulk of the Fortress of St Peter and St Paul, Kazan Cathedral, the Winter Palace itself, I saw them all. And at the centre was the Nevsky Prospect. ‘It is the longest and widest street in the world,’ said Ariadne proudly. ‘Five miles from the Alexander Gardens to the Moscow Gate.’

I was struck by the width of the street, too, the pavements looked as if a dozen people could have marched up them side by side. Very soon Ariadne stopped the car.

‘Now we will walk,’ she said, and took my hand tightly in hers and led me along. ‘This is the glittering world, Miss Rose. Perhaps I shall have to renounce it one day, who knows what may happen? But while it is here, let us enjoy it. Look, here is Alexandre’s.’ She drew in a deep breath. ‘Oh, I adore Alexandre’s.’

Together we stared at the window full of expensive and elegant objects – jade boxes, scarves of Persian silk, chains of gold and ivory, a delicate parasol of white lace with a diamond-studded handle. Never had I seen anything like it. By comparison Jenner’s in Prince’s Street did not exist.

‘Do you have anything like this?’

I shook my head. ‘In London, perhaps. Not in Edinburgh.’

Past Alexandre’s was Druce’s, the ‘English Shop’, where were sold English soap and toothpaste and lavender water – which was much used by the men. After that we went into Wolff’s, the great bookshop, where Ariadne lavishly bought me several books about Russia and a copy of the London Times.

‘Across the road,’ she said in a low voice, ‘is Fabergé’s shop. Even I hardly dare look in there, it is so expensive. Old Madame Narishkin spent the whole of her husband’s salary there in one day, just buying two presents for his birthday. Or that’s the story, anyway.’ She gave that giggle, so like her mother’s. ‘The old goose is silly enough for it.’

A golden-voiced clock somewhere chimed the hour, and it reminded Ariadne of something. ‘Let’s go to Yeliseyeff’s,’ she said. ‘I have to order some ryabchik for Mamma – tomorrow she gives a dinner party.’